Abstract

Objective/Purpose:

To describe the demographic and baseline ocular characteristics, prevalence of blindness and visual impairment among patients undergoing extracapsular cataract extraction for age related cataract at the study hospital over a one year period.

Materials/Patients:

All consecutive patients aged 40 years and above identified with age related cataract in one or both eyes who voluntarily agree to participate were included.

Methods:

The study adhered to the tenets of the Helsinki declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible patients. All patients underwent basic eye examination by the ophthalmologist. Visual impairment was determined for each eye according to the standard WHO categorizations. Information obtained also included age, sex and history of previous cataract surgery. Data were recorded in manual tally sheets and on modified computer Cataract Surgery Record forms. Analyses were done using SPSS (version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results:

The participation rate was 91.2%. There were 495 eyes of 487 consecutive patients. This include 212 males and 275 females (M:F, 1:1.3). The age range was 40 to 99 years with a mean age of 62.76 ± 10.49 years (61.35 ± 9.75 years in men and 63.85±10.9 years in females). Most of the patients (n = 451; 92.6%, 95% CI: 89.9-94.6%) were aged 50 years and above. Sixty patients (12.3%, 95% CI: 9.6-15.5%) had cataract in both eyes, 427 (87.7%, 95% CI: 84.5-90.3%) were in one eye. Among these, preoperatively 16 (3.3%, 95% CI: 2.0-5.3%) had aphakia, 21 (4.3%, 95% CI: 2.8-6.5%) had uniocular pseudophakia. About 63.2% (95% CI: 58.9-67.4%) of patients had normal vision in the better eye (presenting VA ≥6/18). Overall 9.5% (95% CI: 7.3-12.7%) were bilaterally blind. About 96.8% of eyes (95% CI: 94.5-98.0%) undergoing cataract surgery were blind (presenting VA< 3/60).

Conclusion:

The study highlights preponderance of females and high incidence of blinding cataract. Education and early disease awareness may play an important role in these patients and could improve cataract surgical services in our hospital.

Keywords: Age-related cataract, blindness, surgery, pseudophakia, Cataracte liée à l’âge, cécité, chirurgie, pseudophakie

Résumé

Objectif/But:

Pour décrire les caractéristiques oculaires démographiques et de base, la prévalence de la cécité et l’insuffisance visuelle chez les patients subissant une extraction de la cataracte extracapsulaire pour la cataracte liée à l’âge à l’hôpital d’étude sur une période d’un an.

Matériaux/Les patients:

Tous les patients consécutifs âgés de 40 ans et plus identifiés avec une cataracte liée à l’âge chez un ou les deux yeux qui ont volontairement accepté de participer ont été inclus.

Méthodes:

L’étude a respecté les principes de la déclaration d’Helsinki. Un consentement éclairé écrit a été obtenu auprès de tous les patients admissibles. Tous les patients ont subi un examen oculaire de base par l’ophtalmologiste. Une déficience visuelle a été déterminée pour chaque œil selon les catégorisations standard de l’OMS. L’information obtenue comprenait également l’âge, le sexe et l’histoire de la chirurgie de la cataracte précédente. Les données ont été enregistrées dans des fiches de pointage manuelles et sur des formulaires d’enregistrement de chirurgie de cataracte modifiés. Les analyses ont été effectuées à l’aide de SPSS (version 16, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Etats-Unis).

Résultats:

Le taux de participation était de 91,2%. Il y avait 495 yeux de 487 patients consécutifs. Cela comprend 212 hommes et 275 femmes (M:F, 1:1,3). La tranche d’âge était de 40 à 99 ans avec un âge moyen de 62,76 ± 10,49 ans (61,35 ± 9,75 ans chez les hommes et 63,85 ± 10,9 ans chez les femmes). La plupart des patients (n = 451; 92,6%, IC 95%: 89,9-94,6%) étaient âgés de 50 ans et plus. Soixante patients (12,3%, IC 95%: 9,6-15,5%) avaient une cataracte dans les deux yeux, 427 (87,7%, IC 95%: 84,5 à 90,3%) étaient dans un œil. Parmi ceux-ci, préopératoire 16 (3,3%, IC 95%: 2,0-5,3%) avaient une aphakie, 21 (4,3%, IC 95%: 2,8 à 6,5%) présentaient une pseudophakie unioculaire. Environ 63,2% (95% IC: 58,9-67,4%) des patients avaient une vision normale dans le meilleur œil (présentant VA ≥6 / 18). Dans l’ensemble, 9,5% (IC 95%: 7,3-12,7%) étaient bilatéralement aveugles. Environ 96,8% des yeux (95% CI: 94,5-98,0%) subissant une chirurgie de la cataracte étaient aveugles (présentant VA <3/60).

Conclusion:

l’étude souligne la prépondérance des femelles et une forte incidence de la cataracte aveuglante. L’éducation et la sensibilisation aux maladies précoces peuvent jouer un rôle important chez ces patients et pourraient améliorer l’absorption chirurgicale de la cataracte dans notre hôpital.

INTRODUCTION

Cataract continues to be a major cause of blindness worldwide (48%), affecting almost 18 million people.[1] The prevalence of cataract blindness is increasing in many developing countries largely due to lack of a dedicated cataract surgery programs, inadequate human resources and poor management, a lack of basic infrastructure, poor disease awareness, and poverty. It is estimated that about 3.5 million people are blind from cataract in Sub-Saharan Africa.[2] This burden, largely due to age-related cataract, is likely to increase with increasing life expectancy.[3] There were several risk factors being attributed to age-related cataract, which include older age, female gender, smoking, and diabetes. Other risk factors include ultraviolet light, dehydration, and antioxidant deficiencies.[4] The estimated prevalence of blindness, aphakia, and pseudophakia has been reported in several other studies among adult populations with age-related cataract in the United States.[5] Data from the Nigerian National and Visual Impairment Survey determined that female gender and residence in the northern part of the country is a risk factor for blindness.[6] Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital is a tertiary health institution in Kano, Northern Nigeria providing eye care services. To the author's knowledge, there was no previous published data that prospectively evaluate the baseline ocular characteristics of patients with age-related cataract at the study hospital.

Objectives of the study

This study was carried out with the following objectives:

To determine the demographic characteristics of patients with age-related cataract at the study hospital over a 1 year period

To determine the most common preoperative visual acuity (VA) category, proportion of blind or visually impaired patients at the time of surgery during the 1 year period of the study.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a 1 year prospective, observational study. The study was conducted in Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital in Kano, Nigeria, from October 1, 2009 to October 1, 2010. Ethical approval (NHREC/21/08/2008a/AKTH/EC/181) was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the hospital and adhered to the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration. Written and informed consent was sought and obtained by the ophthalmologist from all eligible patients, with the possibility to opt out at any time, after explanation of the nature of the study either in the local dialect, i.e., Hausa, English or by an interpreter in cases of another language as the case may be.

Study team

The study team was made up of staff of the Department of Ophthalmology, Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital comprising one ophthalmologist as the principal investigator, two records officers, 3 ophthalmic nurses, 3 residents, and one optometrist. The ophthalmologist familiarized himself with all the operational definitions and guidelines. The team had 1 day training by the ophthalmologist on the study procedures and operational equipment. A pilot study was conducted before the data collection process to demonstrate and assess the role of each team member on the adherence to operational procedures and uniformity in the data collection. Kappa interobserver assessment, although not conducted, there was agreement in >90% of the results and observations. The investigator, to ensure compliance, conducted periodic assessments.

Study sample

All consecutive patients with age-related cataract planned for extracapsular cataract surgery at the study hospital between October 1, 2009 and October 1, 2010 and who voluntarily consented were included in the study.

Inclusion criteria

All consecutive patients aged 40 years and above with uncomplicated age-related cataract in one or both eyes, who voluntarily agree to participate

Patients scheduled for extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) with posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) implantation.

Exclusion criteria

Patients younger than 40 years or with coexisting ocular disease such as retinitis pigmentosa, corneal opacity, and glaucoma recognized before surgery

Patients with identified causes of cataract (metabolic, traumatic, congenital, uveitic, etc.) rather than simple age-related cataract

Patients planned for a combined procedure involving glaucoma or corneal surgery

Deaf or confused patients or those with whom the investigator has difficulty assessing VA

Patients identified with untreated or uncontrolled systemic illness that could affect the eye or follow-up, such as hypertension or diabetes mellitus

Patients who do not consent to participate in the study.

Basic ocular examination

All patients had basic eye examination by the ophthalmologist to exclude any existing ocular comorbidity that could affect the final visual outcome. Ocular comorbidity was defined as coexisting ocular disease identified preoperatively that was thought likely to limit the final VA outcome to 6/18 or worse. The instruments used included pen torch, direct ophthalmoscope (Keeler, UK), and slit lamp biomicroscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The initial eye examinations were carried out with a pen torch and direct ophthalmoscope. The eyes were examined one at a time for discharge; eyelids for trichiasis or ectropion; cornea for opacity, irregularity, or scarring; and pupils for direct pupillary reaction or posterior synechiae.

The lenses were examined for visually significant opacities. The ophthalmologist made the final diagnosis of cataract. Aphakia (intracapsular cataract extraction; ECCE) or pseudophakia (ECCE-IOL) was noted for all cataract-operated eyes.

Visual acuity

VA was tested at 6 m with the Snellen chart and illiterate E charts based on the patients’ literacy level. Presenting VA was measured monocularly (unaided or with available correction if usually worn). Each patient had a single opportunity to respond to the optotype shown. When the patient missed more than half the characters on any one line, the end point was considered the last line; the patient was able to read without a mistake. For example, a VA of 6/24 was defined as identifying <3 out of 4 presented size 18 optotypes at 6 m. The procedure was repeated for the fellow eye. A test with a pinhole was carried out when VA was <6/6 in either eye. When the patient could not read the largest (size 6/60) optotypes at 6 m with a pinhole, a handheld Snellen or a modified Snellen illiterate E chart was brought toward the patient by decreasing the distance 1 m at a time until it was seen. A presenting VA of 3/60 was defined as identifying presented size 6/60 optotype at a distance of 3 m. When the patient was unable to resolve the largest (size 6/60) optotype at a distance of 1 m, the evaluator will ask the patient to count fingers at a distance of 1 m. When the patient could not distinguish fingers in either eye, then the ability to see hand motion or light perception was tested.

Visual impairment was determined for each eye using the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases 10 categorizations and recorded.

Data collection

Data collected from the evaluation process were recorded on a Manual Tally Sheet, Standardized ICEH Cataract Surgery Record forms, and on a computerized Microsoft Excel 2010 worksheet specifically designed for this purpose.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done using Monitoring Cataract Surgery Outcome software (Version 2.4, Nov 2009), Statistical Package for Social Services (SPSS 16, SPSS Inc.; Chicago, USA) software, and Microsoft Excel 2010 in collaboration with a statistician. Mean and Standard deviation were computed for age. A 2-sample t-test compared population means between the two sexes. The difference in the proportion of visual impairment between age groups and gender-specific proportions of visual impairment were estimated using the Chi-square test at 5% level of significance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participation rate and characteristics of nonparticipants

Five hundred and twenty-six (91.2%) patients were examined out of 577 eligible participants. Fifty-one (8.8%) of these did not consent to participate of which 13 (2.2%) were men and 38 (6.6%) were females. Of the remaining 526 participants, 39 (6.8%) did not meet the study criteria and were excluded from the final analysis. This includes 14 (2.4%) males and 25 (4.3%) females: age range 45–90, mean age was 68.64 ± 11.48. Twenty-two (3.8%) of these 39 patients were excluded due to coexisting ocular comorbidity, another 5 (0.8%) for a combined procedure, 7 (1.2%) had cataract from other causes, and incomplete records for 5 (0.8%) patients. Data of 495 eyes of 487 (84.4%) patients were available for analysis.

Sex distribution

There were 212 males and 275 females (M: F = 1:1.3). The patients mean age was 62.76 ± 10.49 years (61.35 ± 9.75 in men and 63.85 ± 10.9 in females). The difference in mean age between the sexes using 2-sample t-test was statistically significant (P < 0.0077). There was a higher frequency for women in almost all age groups except in 50–59 age groups. This gender distribution was statistically significant (P < 0.0073).

Age distribution

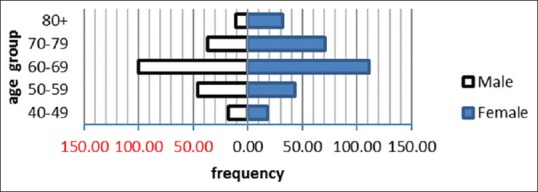

About 92.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 89.9%–94.6%) of patients were 50 years and above. A significant number representing 43.3% (95% CI: 38.3%–47.0%) of the patients was in the age group 60–69 years. The age-sex pyramid [Figure 1] shows the patients distribution by age group and gender.

Figure 1.

Age-sex distribution of 487 patients

Visual acuity

Of the 487 persons evaluated before surgery, 9.7% (95% CI: 7.3%–12.6%, n = 47) were blind and 27.1% (95% CI: 23.3%–31.2%, n = 132) were visually impaired. Before surgery, 96.8% (95% CI: 94.8%–98.0%, n = 479 eyes) of 495 eyes were blind and 3.2% (95% CI: 2.0%–5.2%, n = 16 eyes) were severely visually impaired. This is as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Presenting visual acuity (better eye and operated eye)

| WHO* category of visual impairment | Better eye (persons), n (%) | Operated eye*, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0-6/6-6/18 | 308 (63.2) | 0 |

| 1 - <6/18-6/60 | 106 (21.8) | 0 |

| 2 - <6/60-3/60 | 26 (5.3) | 16 (3.2) |

| 3 - <3/60-1/60 | 30 (6.2) | 90 (18.2) |

| 4 - <1/60-PL | 17 (3.5) | 389 (78.6) |

| 5 - NPL | 0 | 0 |

| 9 - undetermined | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 487 (100.0) | 495 (100.0) |

*Visual acuity preoperatively. WHO=World Health Organization, NPL=No perception of light

Previous cataract surgery

Cataract was uniocular in 87.7% (95% CI: 84.5%–90.3%, n = 427) of persons, and among these, 7.6% (95% CI: 5.5%–10.3%, n = 37) had aphakia or pseudophakia in one eye. The proportion of pseudophakia was 4.3% (95%CI: 2.8%–6.5%) for both sexes while the proportion of aphakia was 3.3% (95% CI: 2.0%–5.3%) for both sexes as shown in Table 2. Females were not found to get significantly more previous cataract surgery than men (P < 0.6656).

Table 2.

Proportion of patients with previous cataract surgery

| Demographic parameters | Aphakia | Pseudophakia |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 16 | 21 |

| Proportion, % (95% CI) | 3.3 (2.0-5.3) | 4.3 (2.8-6.5) |

| Sex | ||

| Male (frequency) | 5 | 8 |

| Proportion, % (95% CI) | 1.0 (0.37-2.4) | 1.6 (0.78-3.3) |

| Female (frequency) | 11 | 13 |

| Proportion, % (95% CI) | 2.2 (1.2-4.0) | 2.5 (1.3-4.5) |

CI=Confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Sex distribution

This study found a slight preponderance of females over males. This may be due to the reason that women have longer life expectancy than men and prevalence of blindness is associated with increasing age and being female in this part of the country.[6] By contrast, studies conducted in other parts of Nigeria in Ago Iwoye, Kaduna, Orlu, and Port Harcourt showed slight male predominance.[7,8,9,10] A hospital-based study conducted in Auckland, New Zealand, and Lahan district of Nepal, respectively, also reported female predominance in uptake of cataract surgery.[11,12] This higher number of females in our study may be due to increasing awareness about cataract surgical services in our facility from community health talks, free eye camps conducted at various times or from increased financial support from the friends of Hospital or other philanthropists. However, further studies may be required to verify the effect of these on attendance for cataract surgery in our facility.

Age distribution

In this study, the mean age for presentation was similar to that reported in Ago Iwoye and Orlu in Nigeria. The average age at which patients had surgery was 70 years and above in developed economies such as New Zealand, the UK, and the United States and was slightly higher than in developing countries.[13,14] This was probably due to increased life expectancy in these countries. The difference may also be attributed to the high exposure to ultraviolet rays from the sunny and hot climate of this region leading to the development of cataract at a much earlier age.[15]

Visual acuity

The proportion of blind patients in the study before surgery was less than reported from earlier studies in Kaduna and Kano with 24.3% and 32%, respectively.[16] Studies conducted in similar settings across Africa and in Asia also showed a high prevalence of bilateral blindness among patients undergoing cataract surgery: Kenya (23.6%), Sierra Leone (51%), and Nepal (98%).[17,18] Preoperatively, cataract was responsible for considerable visual handicap in most of the eyes. Studies from other African countries such as South Africa (94%), Kenya (86.3%), and Sierra Leone (91.7%) showed similar high prevalence of blindness due to cataract preoperatively.[19]

Previous cataract surgery

Our study found that women had more previous cataract surgery including couching than men. A higher proportion of couching, aphakia, or pseudophakia among women had been reported in earlier studies. Ignorance, fear of surgery, affordability, and distance from the facility were some of the barriers to having modern cataract surgery.[20,21,22,23,24] However, gender-specific differences in the cataract surgical uptake had been attributed to gender-specific roles played by each which may be compounded by marital status, educational level, culture, or socioeconomic status.[25,26]

CONCLUSION

Cataract blindness will continue to be a major challenge with increasing aging population worldwide. Baseline characteristics of note were preponderance of females and a high proportion of blinding cataract.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva, Switzerland: [Last cited 2017 July 20]. WHO. Prevention of Blindness and Visual Impairment. 2017: World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.who.int/blindness/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster A. Who will operate on Africa's 3 million curably blind people? Lancet. 1991;337:1267–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92929-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yorston D, Foster A. Audit of extracapsular cataract extraction and posterior chamber lens implantation as a routine treatment for age related cataract in East Africa. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:897–901. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.8.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah SP, Dineen B, Johnson GJ, Khan MA, Jadoon Z, Bourne R, et al. Lens opacities in adults in Pakistan: Prevalence and risk factors. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:381–9. doi: 10.1080/09286580701375179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West SK, Valmadrid CT. Epidemiology of risk factors for age-related cataract. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:323–34. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyari F, Abdull MM, Foster A, Murthy GV, Gilbert CE, Entekume G, et al. Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: The national blindness and visual impairment survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2033–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekibele CO, Ubah JN, Fasina O. A comparative evaluation of outcome of cataract surgery at Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State. Niger J Surg Res. 2004;6:25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alhassan MB, Kyari F, Achi IB, Ozemela CP, Abiose A. Audit of outcome of an extracapsular cataract extraction and posterior chamber intraocular lens training course. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:848–51. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obiudu HC, Obi BI, Anyalebechi OC. Monitoring cataract surgical outcome in a public hospital in Orlu, South Eastern Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2009;50:77–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singabele EJ, Sokolo JE, Adio AO. Cataract blindness in a Nigerian tertiary hospital: A one year review. J Med Med Sci. 2010;1:314–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riley AF, Malik TY, Grupcheva CN, McGhee CN, Fisk M, Craig JP. The Auckland Cataract Study: Co-mobidity, surgical techniques, and clinical outcomes in a public hospital service. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:185–90. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hennig A, Kumar J, Yorston D, Foster A. Sutureless cataract surgery with nucleus extraction: Outcome of a prospective study in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:266–70. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai P, Reidy A, Minassian DC. Profile of patients presenting for cataract surgery in the UK: national data collection. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:893–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.8.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vankatesh R, Muralikrishnan R, Balent LC, Prakash SK, Prajna NV. Outcome of high volume cataract surgeries in a developing country. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1079–83. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.063479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekibele CO, Ashaye AO, Ajayi BG. Risk factors for visually disabling age-related cataract in Ibadan. Ann Afr Med. 2003;2:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdu L. Results of cataract outreach services in a state of Nigeria. Prev Med Bull. 2010;9:225–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yorston D, Gichuhi S, Wood M, Foster A. Does prospective monitoring improve cataract surgery outcomes in Africa? Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:543–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook NJ. Evaluation of high volume extracapsular cataract extraction with posterior chamber lens implantation in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:698–701. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.8.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsch NH. Extracapsular cataract extraction with and without intra-ocular lenses in black patients. S Afr Med J. 1992;81:357–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabiu MM. Cataract blindness and barriers to uptake of cataract surgery in a rural community of Northern Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:776–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habiyakire C, Kabona G, Courtright P, Lewallen S. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness and cataract surgical services in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:90–4. doi: 10.3109/09286580903453514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert CE, Murthy GV, Sivasubramaniam S, Kyari F, Imam A, Rabiu MM, et al. Couching in Nigeria: Prevalence, risk factors and visual acuity outcomes. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:269–75. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.508349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odugbo OP, Mpyet CD, Chiroma MR, Aboje AO. Cataract blindness, surgical coverage, outcome, and barriers to uptake of cataract services in Plateau State, Nigeria. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:282–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.97925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odugbo OP, Mpyet CD. Risk factors for couching practices in Plateau State, Nigeria: Results from a population based survey. Niger J Ophthalmol. 2012;1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtright P, Kanjaloti S, Lewallen S. Barriers to acceptance of cataract surgery among patients presenting to district hospitals in rural Malawi. Trop Geogr Med. 1995;47:15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhaliwal U, Gupta SK. Barriers to the uptake of cataract surgery in patients presenting to a hospital. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:133–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.30708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]