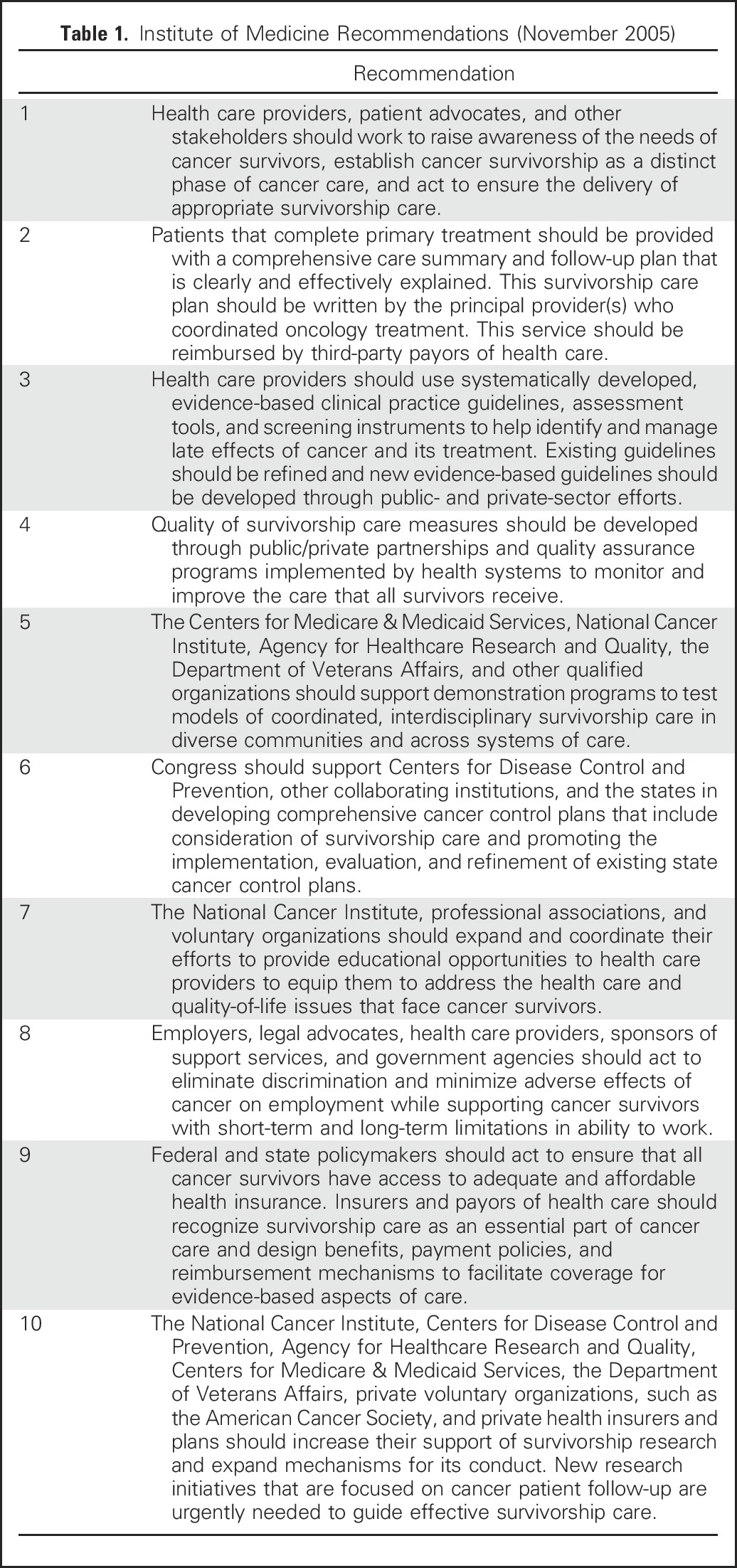

In 2016, a number of important milestones for cancer survivorship were ushered in. It was the 30-year anniversary of the creation of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS), an advocacy organization whose founding members generated the language for cancer survivorship that continues to this day. The NCCS took a compelling position that the term survivor can apply to individuals anywhere along the trajectory after cancer diagnosis through death and included their family members. NCCS leadership also saw a need to address the late and long-term effects of cancer treatment and, importantly, to make patients and families aware of such effects from the outset of care and along the seasons of survival.1 In 2016, we marked the 20th anniversary of the establishment of the Office of Cancer Survivorship (OCS) at the National Cancer Institute (NCI). OCS was charged with directing and supporting cancer survivorship research as well as promoting the education of clinicians, survivors, and caregivers about the unique challenges of life after cancer and ways to manage these. The year 2016 also marked the 10th anniversary of the publication and dissemination of the landmark report, “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition” by the Institute of Medicine (IOM).2 The report outlined 10 recommendations that were aimed at enhancing the care of the growing survivor population that was transitioning into life post-treatment (Table 1). Is it a coincidence that these milestones are each separated by a decade, or is it that each decade’s progress has paved the way for the decade to come? In this perspective, we reflect on the progress made since the IOM report’s 10 recommendations and offer insights into how 2016 may become the birth year of the next important landmark for cancer survivorship.

Table 1.

Institute of Medicine Recommendations (November 2005)

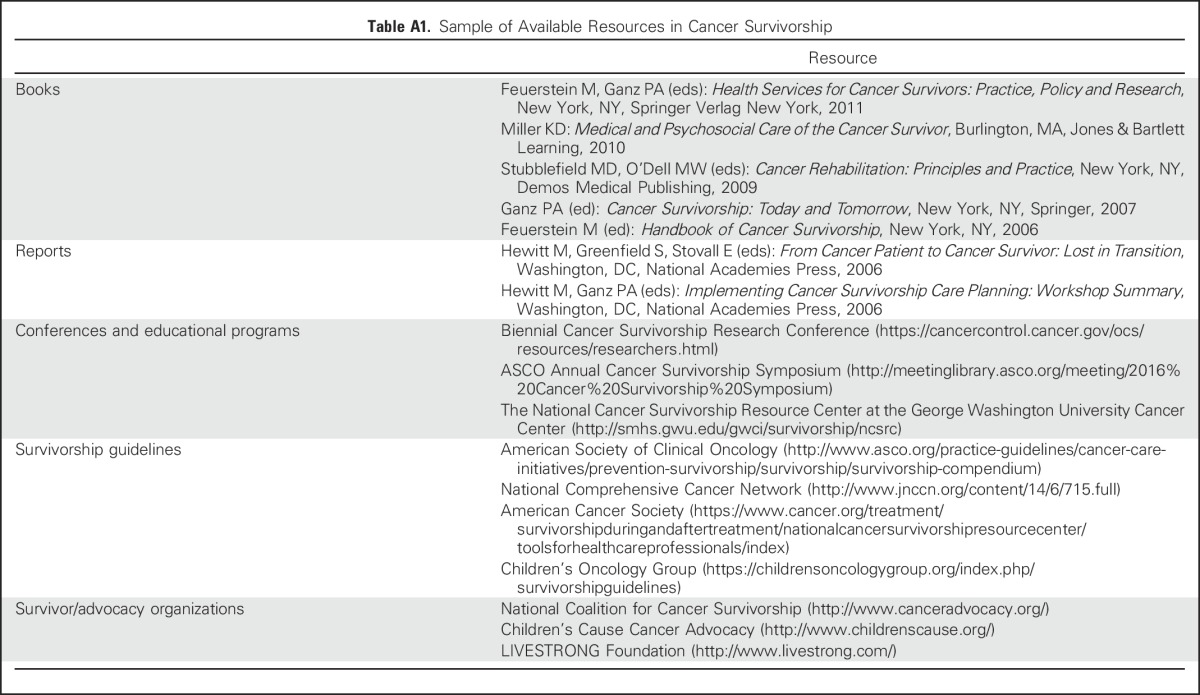

Recommendation 1 focused on broadening the recognition of cancer survivorship as a distinct phase along the cancer care continuum. That survivorship has come into its own during the past decade is reflected in the frequency with which celebrity survivors share their personal stories and the growth in the number of survivorship-focused walks, runs, and other functions, as well as the frequent newspaper columns and blogs that feature survivors and survivorship topics. For professionals, we have seen the emergence of textbooks, dedicated journals, and supplements, as well as local and national educational programs (Appendix Table A1, online only). As the number of survivors who have been diagnosed and who are living with cancer continues to grow—from the current 15.5 million to 20.3 million in 2026, with the majority older than 70 years and more ethnoculturally diverse3-5—we expect that attention to their unique challenges and needs will become even more prominent topics of lay and professional dialogues.

IOM Recommendation 2, which calls for the development and dissemination of survivorship care plans (SCPs) to better inform patients of what to expect in the post-treatment period, created a groundswell of attention. At the behest of the advocacy community, IOM held a workshop in the spring of 2006 in response to the original report that asked experts to identify the next steps in moving care planning forward.6 Since then, many have reported on the practical challenges of generating and delivering SCPs,7-10 evaluated the impact of such plans on patient outcomes,11,12 and suggested solutions to optimize their use.13-16 Although the evidence base for SCP efficacy remains sparse and, in some cases, controversial, policy mandates for SCP use have been advanced.17 As the Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation standard for this recommendation is implemented, we envision that survivors’ understanding of their cancer treatment, potential late effects, and recommended follow-up care will improve. In the meantime, the field has begun to realize that the real challenge in cancer survivorship is not just the development of the survivorship care plan tool, but the optimization of the survivorship care planning process in such a way as to result in more tailored and coordinated care and, ultimately, decreased rates of preventable morbidity and mortality after cancer.11

Although there is clearly more work to be done, it is remarkable to note the progress in the development of consensus- and evidence-based guidelines for survivorship care (Recommendation 3). During the past decade, many professional organizations, including ASCO,18-24 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,25,26 and the American Cancer Society,19,27-29 among others, have generated guidelines that have focused on the physical and psychosocial care of survivors, expanding the scope beyond what used to be limited to surveillance for recurrences. The Children’s Oncology Group has continued to update its recommendations30 and has embarked on harmonizing international guidelines for the follow-up of survivors of childhood cancer.31 As personalized medicine evolves, late effects may be a thing of the past, especially if we can define the personal host factors that render some individuals at greater risk of the most troublesome late effects, and guidelines will instead focus on individuals’ risks and benefits from specific treatments.

Quality in cancer survivorship (Recommendation 4) is still in need of measurement. ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative is leading the way, but “we have just begun.”32 The 2015 introduction by the American College of Surgeons’ CoC of criteria for survivorship care has added teeth to the demand for quality indicators. Specifically, CoC requires that centers document the development and delivery of an SCP to those who complete treatment, with a copy sent to the primary care provider, as a quality standard.17 Such measures may become routine as payors expand implementation of various payment models. They will also permit us to more systematically assess progress made in delivering this standard of care. Whereas technical quality measures in cancer survivorship are in their infancy, the NCI has focused on assessment of the delivery of patient-centered survivorship care by conducting surveillance studies that assess cancer survivors’ experiences of post-treatment survivorship care.10,33-40 Collaboration between the NCI and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has resulted in the development of the CAHPS Cancer Care Survey.41 CAHPS is considered the gold standard for measuring patients’ care experience.42

Whereas most cancer-related research continues to focus on basic science and clinical treatment, there has been more emphasis on dissemination and implementation research (Recommendation 5), with projects being funded by the NCI, the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the American Cancer Society (ACS), and, most recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services with the implementation of the Oncology Care Model.43 Best practices have to be disseminated and implemented in real-world settings.44-46

With support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), many state cancer control plans have been responsive to Recommendation 6, which called for the development of cancer plans that include survivorship care planning; however, progress has been variable and not yet clearly measurable. Resources are now available to help states evaluate their plans with proposed outcomes and to connect with others via the George Washington University GW Cancer Institute State Cancer Plans Priority Alignment Tool and the Cancer Control Planet.47,48 It will be important to continue to understand initiatives at the state level, specifically, how they may have improved the medical care and outcomes of survivors, and to develop mechanisms to review and share progress among states to facilitate cross-state learning.

IOM recognized that there are gaps in the information and education of health care providers and survivors themselves (Recommendation 7). There is no doubt that there has been notable growth in educational programs that are focused on survivorship by hospitals, cancer centers, and professional organizations. Many major cancer centers now provide annual survivorship conferences for staff and the public. Recognizing the important role of communication and coordination between primary care providers and oncology care providers attending to cancer survivors’ health, ASCO, the American Academy of Family Practitioners, and the American College of Physicians launched in 2016 the first annual survivorship symposium that aimed to enhance education for and promote collaboration between oncology and primary care providers.49 Other efforts in the area of education include development by the ACS of multiple cancer-specific survivorship guidelines19,27-29 and a smartphone application for use by primary care providers,50 creation and dissemination of a primary care e-learning platform by the George Washington Cancer Center with support from the ACS51 and CDC, the NCI/ACS/LIVESTRONG/CDC Biennial Cancer Survivorship Research Conference,52 which draws hundreds of attendees, as well as the launch of the ASCO Cancer Survivorship Committee in 2011, which resulted in the compilation of resources53 and the ASCO Survivorship Curriculum.54

Recommendation 8 emphasized the need to eliminate discrimination and minimize untoward effects of cancer on employment. Studies continue to show the potentially adverse effects of cancer on employment55-59 and the need to emphasize the potential limitations that the experience of cancer can have on subsequent work productivity and financial burden. Broadly referred to as financial toxicity,60,61 the economic impact of cancer is a growing topic of research. With younger generations that are likely to move frequently between jobs and to take more entrepreneurial roles where flexibility when illness strikes may be more limited—combined with older adults staying longer in the workforce to ensure sufficient retirement funds—much more work will be needed to better understand and mitigate the harmful impact of cancer on employment.

Clearly, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has helped advance Recommendation 9 much further than had been anticipated. The ability of those with pre-existing health conditions to obtain health insurance coverage, ability to purchase coverage outside the work place, which allows young adults to remain on their parents’ insurance until age 26, as well as removal of the limitation on lifetime expenditures, and other important elements of the ACA have been critically important for survivors of cancer. Although more progress is needed to achieve equitable access to affordable, quality, and evidence-based health care, the ACA has enhanced access to primary care needed for cancer prevention, screening, and early detection; expanded coverage to more Americans, including younger adults; and eliminated some of the biggest barriers to coverage. As the future of the ACA is being debated, it is critical that any revisions take into account the health care–related needs of survivors of cancer.

Furthermore, there has been a sharp increase in research support for survivorship science by governmental agencies, the Department of Veterans Affairs, private charity organizations, and insurers (Recommendation 10).62-64 The addition of new funding entities, such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, has enriched resources for investigator support. Although the OCS documented a steady increase in survivorship grants between 2006 and 2012, the number has leveled off as a result of the flattening of the NCI budget. Competition for survivorship science with funding for research that is aimed at identifying cures remains a challenge.

As we acknowledge the end of 2016, we marvel at the progress that has been made over the past decade and the two preceding decades of cancer survivorship advocacy. During this time, the number of individuals who have survived cancer has grown, and more are living longer and getting older.3 There are still those who survive their cancers but are lost in transition, who do not get the care they need, who find the health care system confusing and uncoordinated, and who continue to suffer with and die of the late and long-term effects of curative cancer treatments. We must educate survivors, primary care providers, oncology providers, and other specialists about the needs of this population. Whereas the widely promoted SCP is a tool, it is not an end in itself. We must strive to coordinate care, using a risk-stratified approach that not only focuses on cancer-related effects, but also on comorbid medical conditions and socioeconomic disparities. Research should address questions that remain, promote development of measurable outcomes, and evaluate models of care that pertain to real-world decisional dilemmas that are faced by survivors of cancer, their caregivers, and clinicians. Health care policy initiatives must fully take on inequities in access and the financial burden of cancer care, and promote strategies to return to work, school, and life. We made progress, but more effort is needed to ensure all survivors receive quality, comprehensive, and coordinated care. What will the next decade achieve? As the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academy of Medicine revisits cancer survivorship care in July 2017, we hope this reflection will help set an agenda.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This manuscript was written by a team that brings in perspectives of researchers, clinicians, and survivors. As we reflect on the progress made in the field of cancer survivorship, we are particularly grateful to those survivors who are no longer with us. We have learned and continue to learn by having cancer survivors and their families share their stories, participate in studies, and advocate on behalf of this important cause. We dedicate this piece to Ellen Stovall (1946 to 2016), a member of the 2006 Institute of Medicine panel, who, as a 44-year survivor of three bouts of cancer, was a pioneer and champion for cancer survivors worldwide. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, or the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Appendix

Table A1.

Sample of Available Resources in Cancer Survivorship

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Administrative support: Larissa Nekhlyudov

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Going Beyond Being Lost in Transition: A Decade of Progress in Cancer Survivorship

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Larissa Nekhlyudov

Honoraria: Pri-Med, UpToDate

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pri-Med

Patricia A. Ganz

Leadership: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I)

Stock or Other Ownership Xenon Pharma (I), Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Silarus Therapeutics (I), Merganser Biotech (I), Teva Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott Laboratories

Honoraria: Vifor Pharma (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Keryx (I), Merganser Biotech (I), Silarus Therapeutics (I), InformedDNA, Vifor Pharma (I)

Research Funding: Keryx (I)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Related to iron metabolism and the anemia of chronic disease (I), Up-to-Date royalties for section editor on survivorship

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Keryx (I)

Neeraj K. Arora

No relationship to disclose

Julia H. Rowland

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Mullan F. Seasons of survival: Reflections of a physician with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:270–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507253130421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1029–1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship . Institute of Medicine National Cancer Policy: Implementing Cancer Survivorship Care Planning—Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaseg K, Kile M, Salner AS. Survivorship & palliative care: A comprehensive approach to a survivorship care plan. 2012 NCCCP Monograph. http://www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/accc/ncccp_monograph/index.php?startid=49

- 8.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, et al. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:101–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Risendal B, et al. Survivorship care planning after the institute of medicine recommendations: How are we faring? J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:358–370. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanch-Hartigan D, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, et al. Provision and discussion of survivorship care plans among cancer survivors: Results of a nationally representative survey of oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1578–1585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parry C, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, et al. Can’t see the forest for the care plan: A call to revisit the context of care planning. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2651–2653. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan ME, Gormally JF, Butow P, et al. Survivorship care plans in cancer: A systematic review of care plan outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1899–1908. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer DK, Birken SA, Check DK, et al. Summing it up: An integrative review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006-2013) Cancer. 2015;121:978–996. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:345–351. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Journey Forward Home. http://www.journeyforward.org

- 16.OncoLink OncoLife survivorship care plan. http://www.oncolink.org/oncolife/

- 17.American College of Surgeons . Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient Centered Care (ed 2016) https://www.facs.org/∼/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/2016%20coc%20standards%20manual_interactive%20pdf.ashx [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3325–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:611–635. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Penson DF. Prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines: American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline endorsement. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e445–e449. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1941–1967. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1840–1850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen BL, Rowland JH, Somerfield MR. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:133–134. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2500–2510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denlinger CS, Carlson RW, Are M, et al. Survivorship: Introduction and definition. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:34–45. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, et al. Survivorship: Screening for cancer and treatment effects, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1526–1531. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:428–455. doi: 10.3322/caac.21286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:203–239. doi: 10.3322/caac.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Children’s Oncology Group Survivorship guidelines. https://childrensoncologygroup.org/index.php/survivorshipguidelines

- 31.International Guideline Harmonization Group International Guideline Harmonization Group for late effects of childhood cancer. http://www.ighg.org/international-guideline-harmonization-group/

- 32.Mayer DK, Shapiro CL, Jacobson P, et al. Assuring quality cancer survivorship care: We’ve only just begun. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015;2015:e583–e591. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weaver KE, Aziz NM, Arora NK, et al. Follow-up care experiences and perceived quality of care among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancers. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e231–e239. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, et al. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor’s perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1280–1289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Alfano CM, et al. Role of oncologists and primary care physicians in providing follow-up care to non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors within 5 years of diagnosis: A population-based study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1509–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2113-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klabunde CN, Han PK, Earle CC, et al. Physician roles in the cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors. Fam Med. 2013;45:463–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forsythe LP, Parry C, Alfano CM, et al. Use of survivorship care plans in the United States: Associations with survivorship care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1579–1587. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Leach CR, et al. Who provides psychosocial follow-up care for post-treatment cancer survivors? A survey of medical oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2897–2905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forsythe LP, Kent EE, Weaver KE, et al. Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1961–1969. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, Smith JL, et al. Receipt of cancer treatment summaries and follow-up instructions among adult cancer survivors: Results from a national survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:32–43. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0242-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Cancer Institute SEER-CAHPS linked data resource. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seer-cahps/

- 42.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality CAHPS surveys and guidance. doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/index.html [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, et al. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Using an episode-based payment model to improve oncology care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:114–116. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selove R, Birken SA, Skolarus TA, et al. Using implementation science to examine the impact of cancer survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3834–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alfano CM, Smith T, de Moor JS, et al. An action plan for translating cancer survivorship research into care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju287. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, et al. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:804–812. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.GW Cancer Institute State cancer plans priority alignment resource guide & tool. https://smhs.gwu.edu/cancercontroltap/sites/cancercontroltap/files/PriorityAlignmentToolCombined-FINAL_20150302.pdf

- 48.National Cancer Institute Cancer Control P.L.A.N.E.T. https://cancercontrolplanet.cancer.gov/index.html

- 49.American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer survivorship symposium: Advancing care and research—A primary care and oncology collaboration. http://survivorsym.org/

- 50.American Cancer Society American Cancer Society (ACS) survivorship care guidelines app FAQs. http://www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorshipduringandaftertreatment/nationalcancersurvivorshipresourcecenter/survivorship-guidlines-app-faq

- 51.George Washington School of Medicine & Health Sciences Cancer survivorship e-learning series for primary care providers. https://smhs.gwu.edu/gwci/survivorship/ncsrc/elearning

- 52.American Cancer Society 8th Biennial Cancer Survivorship Research: Innovation in a rapidly changing landscape. http://old.cancer.org/subsites/survivorship2016/

- 53.American Society of Clinical Oncology Survivorship compendium. https://www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship/survivorship-compendium

- 54.Shapiro CL, Jacobsen PB, Henderson T, et al. ReCAP: ASCO core curriculum for cancer survivorship education J Oncol Pract 12145, e108-e1172016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farley Short P, Vasey JJ, Moran JR. Long-term effects of cancer survivorship on the employment of older workers. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Medical costs and productivity losses of cancer survivors--United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:505–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guy GP, Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1024–1031. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R, et al. Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: Results from a multisite study. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:1104–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP.Financial toxicity, part I: A new name for a growing problem Oncology (Williston Park) 2780-81, 1492013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP.Financial toxicity, part II: How can we help with the burden of treatment-related costs? Oncology (Williston Park) 27253-254, 2562013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harrop JP, Dean JA, Paskett ED. Cancer survivorship research: A review of the literature and summary of current NCI-designated cancer center projects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2042–2047. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jacobsen PB, Rowland JH, Paskett ED, et al. Identification of key gaps in cancer survivorship research: Findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology survey. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:190–193. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rowland JH, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, et al. Cancer survivorship research in Europe and the United States: Where have we been, where are we going, and what can we learn from each other? Cancer. 2013;119(suppl 11):2094–2108. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]