Abstract

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a distinctive ulcerative skin disorder of unknown etiology, associated with an underlying systemic disease in up to 70% of cases. The condition is characterized by the appearance of one or more necrotic ulcers with a ragged undermined violaceous border and surrounding erythema. Lesions are often initiated by minor trauma. The condition can affect any anatomical site, however the head and neck are rarely involved. Although the oral cavity is subject to recurrent minor trauma through everyday activities such as mastication and oral hygiene, as well as during dental treatment, oral lesions appear to be extremely rare. In an effort to provide a detailed explanation of the oral manifestations of PG, a systematic search was conducted using medical databases. A total of 20 cases of PG with oral involvement were reported in the English and French literature. The objectives of this article are to present the pertinent diagnostic criteria and to discuss the differential diagnosis and therapeutic modalities.

Keywords: Pyoderma gangrenosum, Persistent oral ulcer, Oral, Oropharyngeal

Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis that can involve the skin and mucosae. Sites of predilection are the lower extremities and the trunk, but any cutaneous site may be affected [1–3]. The skin over the tibia is a classic site for PG lesions. Skin lesions consist of extensive, rapidly progressing, painful necrolytic ulcers that can exceed 10 cm in diameter, with undermined edges and violaceous borders. Pustules or tender erythematous nodules can precede these ulcers. Lesions have a rapid onset and generally develop over a period of 4–8 weeks [4, 5]. Cribriform scarring is a typical presentation of healed skin lesions [2, 6]. Bullous and vegetative forms have been reported, but are less common than the ulcerative and pustular forms [7]. The diagnosis is established between 30 and 50 years of age. Women are more commonly affected than men. In as many as 70% of patients, an underlying systemic condition can be associated with the occurrence of PG [2].

Etiology and pathogenesis are unclear. A multifactorial origin including neutrophilic dysfunction, overexpression of mediators of inflammation and genetic mutations predisposing patients to PG has been suggested in a recent review [8, 9]. Pathergy, a skin reaction in which minor mechanical trauma such as a scratch, incision or needle stick leads to the development of a papule, pustule or ulceration, has been seen in about 30% of patients with cutaneous PG [10]. Minor trauma and surgery (colostomy, hysterectomy, caesarian section, breast surgery, etc.) are suggested as initiating factors in lesion development [1–4, 8, 11]. Consequently, aggressive surgical wound debridement or skin grafting is contra-indicated in these patients.

Although the oral mucosa is repeatedly traumatized through everyday activities such as mastication and oral hygiene, and can be iatrogenically injured during dental treatment procedures, oral manifestations of PG have been reported rarely and mainly as isolated cases in the scientific literature. This paucity of identified cases suggests that many cases may have been undiagnosed or misdiagnosed (Fig. 1). For a dental practitioner treating a patient known to have PG, the risk of triggering oral lesions of PG secondary to mucosal injury is unknown. Furthermore, if oral PG lesions were to develop, they would need to be accurately differentiated from other oral ulcerative conditions, such as major aphthae, traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE), neutropenic ulcers, manifestations of infectious diseases or oral squamous cell carcinoma, amongst others, in order to be properly managed. In an effort to provide a detailed explanation of the oral manifestations of PG, a systematic search was conducted using medical databases. This article presents the pertinent diagnostic criteria, discusses the differential diagnosis and therapeutic modalities for PG involving the oral cavity.

Fig. 1.

This 67-year-old white male presented a thin leukoplakic lesion on the posterior dorsal tongue. His medical history included hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia, for which he took rovustatin, metformin and olmesartan. He reported a 20 pack-year smoking history, having quit smoking 2-months prior, and consumed 6 beers/week for the last 40 years. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as hyperkeratosis with focal mild epithelial dysplasia and no evidence of candidiasis. At the 1-week post-op examination, he presented normal healing of the biopsy site. One month later, he presented to the emergency dental clinic complaining of tongue discomfort. A large necrotic ulcer at the site of the biopsy was noted (picture). There was no purulence or submandibular lymphadenopathy. A second biopsy of the border of the ulcer was signed out as a non-specific ulcer. The patient was prescribed Chlorhexidine 0.12% rinses BID and clindamycin 500 mg TID × 14 days. The lesion healed gradually over the next 2 months. Shortly after, he was diagnosed with primary lung cancer (the patient did not know which type)

Search Strategy

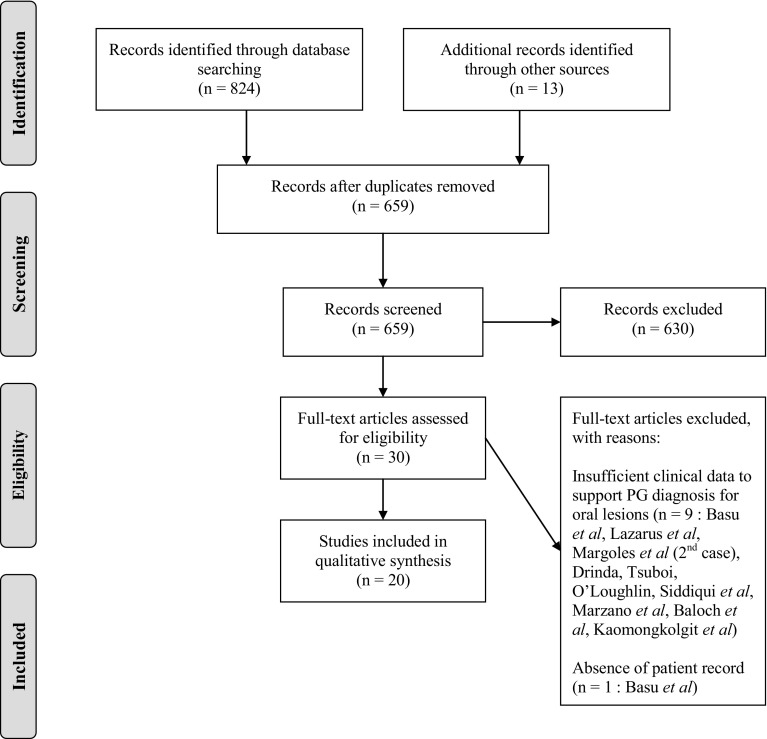

A thorough search using the PubMed and Embase databases was executed between September 1st 2015 and February 5th 2016. The combination of MeSh terms “Oral” and “Pyoderma Gangrenosum” was entered in the search fields. The reference list of each article was searched for any prior unidentified cases. Considering the rare occurrence of oral lesions in patients diagnosed with PG, it was impossible to assess articles based on methods of randomization, patient selection, or blinding. No limitations on language or date of publication were imposed. None of the articles included in this review revealed any source of bias or conflict of interest. The quality of articles was assessed based on the rigor of the diagnostic methods, histopathological analysis of biopsied specimens, detailed therapeutic management, and patient follow-up. Only lesions clinically resembling PG and properly diagnosed by methods of exclusion were included in the qualitative analysis. Considering the non-specificity of the histopathologic appearance of these lesions, the absence of biopsies of oral ulcers was not considered as a criterion of exclusion in this review. However, it was considered an element reinforcing the diagnosis of PG by excluding certain similar pathologies [2]. Based upon these requirements, 10 cases were excluded from this review [6, 12–15]. The following Prisma Flow Chart exhibits the selection methodology (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Prisma flow-chart

Results

A review of the English and French-language literature revealed 20 acceptable cases of intraoral PG. The important features of these cases, as reported in individual case reports, are summarized in Table 1. The clinical and epidemiological data is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Published cases of oral involvement in patients with PG

| Sex/age (years) | Associated systemic disorders | Oral lesions and other PG manifestations | Oral biopsy | Successful treatment modalities and follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margoles et al. [14] | ||||

| M/28 | UC Anemia |

Deep irregular ulceration (4 × 4.5 cm) on the L side of the palate and maxillary alveolar ridge. Base of the lesion friable and granular. Lesion is firm but noninvasive Other PG manifestations None |

Non-specific inflammation No bacterial infection |

Prednisone PO 10 mg TID Lesion healed within 6 mo |

| Philpott et al. [34] | ||||

| M/83 | RA Diabetes mellitus |

1-week sudden onset of painful subcutaneous nodules on the tongue, with rapid development of necrosis Other PG Manifestations Similar lesions affecting the R arm, L foot and scrotum. R forearm ulcer measured up to 12 cm with complete loss of subcutaneous tissue. Similar lesions 3 mo prior that healed with local treatment (gold leaf) |

None | Sodium cephalothin 1 g QID × 10 days. Followed by prednisone PO 60 mg die No new lesions appeared with prednisone therapy. Ulcer of R forearm subsequently grafted with good results. Free of lesions for 10 mo while on maintenance dose of corticosteroids |

| Yusuf and Ead [27] | ||||

| M/61 | Arthritis Diverticular disease |

Exuberant granulomatous lesion on the R side of the tongue, 3 cm in diameter and painful. Increased in size, along with hand ulcer, when initially treated with antibiotics Other PG manifestations 3 cm ulcer with blue undermined borders on dorsum of R hand. Similar episode 7 yrs prior on abdominal wall, accompanied by gingival and tongue ulcers |

None | Prednisolone PO 100 mg die + adrenocorticotropic hormone IM 80 mg Tongue and hand lesions improved after 1 week. Tongue lesion clearing completely in 4 wks |

| Snyder [53] | ||||

| F/29 | None | Pustular eruption of oral mucosa evolving into ulcers Other PG manifestations Other PG lesions involving cheek, periauricular area, antihelix of ear (large undermined ulcer), chin, R lower leg (2 × 2 cm ulceration with undermined edges). Fever |

None | Methylprednisolone IV 50 mg BID + Dapsone PO 100 mg die + Intralesional injection of Triamcinolone 20 mg/mL/week Complete healing of ulcers after 6 wks of prednisolone and dapsone therapy. Free of disease for 4 yrs without treatment |

| Kennedy et al. [26] | ||||

| F/54 | Alcoholic liver disease IBD Degenerative joint disease Peptic ulcer disease, Hypertension Only medication: hydrochlorothiazide |

2 × 1 cm ulcer on the L lateral mid tongue present for 6 wks. Irregular borders, raised, pale, infiltrated edges. Center of the ulcer: light tan color. Tender to palpation Other PG manifestations Shallow, crusted 5 mm ulcers of the nose, ear tragus and lobe, unrelated to trauma, present for 6 wks without evidence of healing. Voice hoarseness caused by small vocal cord ulcers. 6 cm erythematous shallow ulcer of R wrist. R dorsal foot showed 8 cm shallow violaceous ulcer with raised borders. All ulcers were tender to palpation |

Mucosal ulceration and necrosis with severe inflammatory infiltrate comprised of neutrophils with a few lymphocytes extending to the skeletal muscle. Absence of granulomas and vasculitis | Cefazolin IV × 5 days + methylprednisolone pulse therapy 1 g/day × 5 days Maintenance therapy: prednisone PO 30 mg every other day Healing after 5 days of cefazolin and methylprednisolone therapy Patient lost to follow-up |

| Yco et al. [10] | ||||

| M/62 | PV Erythema migrans |

Vascular-appearing tumor on the mid hard palate, tender and firm. Present for 5 days, measured 1 × 1 cm initially Lesion spread after biopsy to involve entire hard palate and lingual alveolar ridge Other PG manifestations PG of the leg 2 yrs previously. Eventually developed PG of the left postauricular crease and lateral neck |

Necrosis, vasculitis and inflammation consistent with but not pathognomonic for PG | Symptomatic therapy: kaolin, pectin, lidocaine and Benadryl mouthwash 2 wks after biopsy, the lesion steadily healed and the palatal mucosa eventually returned to normal |

| Buckley et al. [19] | ||||

| M/35 | None | Recurrent, severe painful pharyngeal ulceration extending to the soft palate and tongue Other PG Manifestations Recurrent oral ulcerations were followed by typical PG ulcers on the shins and hands |

Ulcer surrounded by dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate and a vascular bed | Prednisolone 60–80 mg die controlled the disease for 4 years. Then, complete remission with thalidomide 100 mg die for 2 years – withdrawn due to the development of peripheral neuropathy. Maintenance therapy: prednisolone 15 mg + Sulphamethoxypyridazine 750 mg die Complete clearance of cutaneous lesions with maintenance therapy. Pharyngeal ulcerations continue to recur |

| Bertram-Callens et al. [25] | ||||

| M/62 | PV | Multiple ulcerations with central necrosis and hemorrhage on the dorsal surface of the tongue (5 cm), the lips, gingiva and the palate (<1 cm). The lesion on the tongue had a hyperplastic and exophytic aspect Other PG manifestations PG affecting the R leg, dorsum of the foot, and eyes (conjunctivitis, anterior uveitis, corneal ulcer and abscess) |

None Yeast culture of the lingual ulcer showed Candida pseudotropicalis (carrier state) |

Methylprednisolone 80 mg: 2 IM injections Complete healing of cutaneous, buccal and ocular ulcers within 1 week |

| Goulden et al. [16] | ||||

| M/26 | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria | 1st episode: tender swelling, erosions and crusts on lower lip 2nd episode: Necrotic ulcer of entire lower lip Other PG manifestations None |

Ulcerated epithelium with central fibrinoid necrosis of the corium, chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate including a few neutrophils. An infective etiology was excluded | Prednisolone PO 80 mg die Rapid healing of the lesion. The dose was gradually reduced |

| Setterfield et al. [5] | ||||

| M/54 | IgA paraproteinaemia | Well-defined necrotic oropharyngeal ulceration (5 × 4 cm) and ulcers on the R commissure, lateral borders of the tongue and R buccal mucosa Other PG manifestations Concurrent ulceration of the L lower limb. PG ulceration of the R lower limb 4 yrs previously |

Several oral biopsies were performed. Each demonstrated a superficial neutrophilic infiltrate, mixed chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the corium. No evidence of vasculitis | Pulsed IV therapy administered monthly (6 courses) with Methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days + Cyclophosphamide 500 mg for 1 day Complete healing of the oral ulceration |

| Hernandez-Martin et al. [17] | ||||

| F/84 | Refractory anemia with ringed sidero-blasts, MGUS IgA k type with kappa chain pro-teinuria, Osteo-arthritis, HBP |

Extensive ulceration of 3-mo duration involving the R soft and hard palate and the R tonsil Other PG manifestations None |

Dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the corium. Dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the deeper portion of the mucosa. No evidence of vasculitis. PAS and Gram stains negative | Corticosteroids PO 1.5 mg/kg die Resolution of the oral ulcer after a few weeks of treatment |

| Park et al. [18] | ||||

| M/8 | None | Painful enlarging ulcer (1 × 1 cm) on L lateral tongue covered by yellowish debris. Present for 1 mo Other PG manifestations None |

Ulceration with necrosis extending to the skeletal muscle with a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of neutrophils and eosinophils. No evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture negative for fungus but positive for S. viridans and F. oryzihabitans | Cyclosporine A 5 mg/kg/day + intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection Healing within 6 mo with scarring of tongue. No recurrences 1 year after cessation of cyclosporine A |

| Isomura et al. [30] | ||||

| F/28 | Anemia IgA paraproteinaemia |

Deep ulcers with erythematous borders and central necrosis on the R buccal commissure and tongue. Multiple pharyngeal ulcers Other PG manifestations History of pustules and painful ulcers of perianal area since the age of 22 2 mo previously, she presented with extensive PG ulcerations involving axillary, perianal and popliteal areas Conjunctivitis. Nasal septal perforation |

Neutrophilic infiltrate in the epithelium and submucosa with presence of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Absence of vasculitis, angiocentric cellular infiltrate or granulomas. Lymphocytes were CD45RO+, CD3+, CD20−, CD56−. EBER negative. C-ANCA negative | Prednisolone PO 20 mg die Maintenance therapy: Prednisolone PO 7.5 mg die Partial regression of oral ulcers with prednisolone 20 mg die Pharyngeal and perianal ulcers persist with maintenance therapy |

| Paramkusam et al. [24] | ||||

| F/42 | None | Solitary elliptical 4 × 2 cm ulcer (preceded by a papule) with undermined erythematous borders on the anterior hard palate. Necrotic bone present at the bottom of the ulcer. Pus discharge. Tenderness upon palpation. Bone loss surrounding teeth in the area. Second lesion on left retromolar area 2 weeks after start of treatment Other PG manifestations Multiple recurrent PG ulcers of the lower and upper extremities and the abdomen for the past 3 yrs. Healing with cribriform scarring |

Central necrosis with neutrophilic infiltration, surrounded by dense collections of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Proliferating capillaries. Presence of fragments of bones with debris | Prednisolone PO 30 mg die + dapsone + metronidazole ointment TID + chlorhexidine 0.12% mouth wash TID + debridement of the lesion Both the palatal and retromolar lesions healed within 6 wks |

| Poiraud et al. [20] | ||||

| M/56 | Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, with eventual acute transformation | Multiple ~1 cm necrotic ulcers with violaceous borders and flat violaceous papules on the tip of the tongue and the lower labial mucosa Other PG manifestations Abdominal SC injections of enoxaparin was followed by the appearance of a periumbilical crater-like necrotic ulcer surrounded by erythema. Surgical debridement of the abdominal ulceration was followed by lesional enlargement. Arthritis of the ankle, mesenteric panniculitis and interstitial pulmonary infiltrate |

Sheets of neutrophils within the epithelium and corium. No evidence of vasculitis or neoplasia | Methylprednisolone IV 1500 mg (bolus) followed by Prednisone 1 mg/kg die Oral ulcers healed within 3 wks. Abdominal ulcer healed after 4 mo |

| Chariatte et al. [23] | ||||

| M/82 | UC | Ulcerated tumefaction on the R buccal mucosa (4 × 1 cm) with necrosis in the anterior portion Other PG manifestations A few days later, inflammatory papules, which eventually formed central ulcers, formed on the arms, axillae, thorax and back Recurrence of skin lesions 4 yrs later |

Deep ulcer with its base extending to the muscular layer, covered by a thick layer of reticulated fibrin. Mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes). At the margins, the mucosa is hyperplastic in there is presence of pus. No evidence of vasculitis. Histiocytes and plasma cells in the lateral deeper portions | Prednisone 50 mg die with topical protopic 0.1% application (with sterile gauze) Favorable evolution of cutaneous lesions. Recurrences of PG in the following years when corticosteroids were ceased |

| Verma et al. [22] | ||||

| F/65 | RA Osteoarthritis History of nephrolithiasis |

Deep ulcers of the tongue and buccal mucosa. Tongue ulcer measures 3 cm in diameter, with irregular borders, rolled erythematous margins and a granular erythematous ulcer bed Other PG manifestations 6-week history of widespread necrotizing cutaneous ulceration painful deep ulceration involving both breasts, abdomen, perianal skin and feet |

None Cutaneous biopsies lead to a diagnosis of PG with oral involvement |

Pulsed IV methylprednisolone 1 g + broad spectrum antibiotics + prednisolone 60 mg die resulted in a dramatic reduction in pain in 48 h. MMF 2 g die was then introduced Mucosal and cutaneous ulcers healed within 5 wks of MMF treatment |

| Curi et al. [21] | ||||

| M/58 | UC | Extensive (3 × 2 cm) ulceration, covered by a yellow pseudomembrane with a peripheral erythematous halo, on the L tonsillar pillar and soft palate. Superficial ulcer on the R side of the tongue Other PG manifestations Multiple ulcerations of the trunk, limbs, face and eyelid, diagnosed clinically and histopathologically as PG |

None | Oral lesions managed with Chlorhexidine 0.12% mouth-wash and topical corticosteroids Prednisolone PO 40 mg die + mesalazine 800 mg die, oxacillin 2 g die Rapid and complete resolution of the mucocutaneous lesions after a week of treatment |

| Al Attas et al. [29] | ||||

| M/21 | IBD Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism |

Recurrent, painful, ulcerative skin and mouth lesions. Fluid-filled bullae that ruptured forming ulcers which gradually increased in size on the lip vermilion, tongue and labial mucosa Lip swelling and crusting Other PG manifestations PG lesions involving the lower and upper limbs |

Extensive neutrophilic infiltration, hemorrhage and mononuclear cells. Neutrophils around and within the vascular walls. Leukocytoclasia but no evidence of vasculitis. No tissue immunofluorescence was done | IV Vancomycin 1 g die + prednisolone 40 mg die + local wound care for one week Cyclosporine 150 mg die + Dapsone 100 mg Progression of disease halted after 1 week of treatment. Rapid and good response with addition of cyclosporine and dapsone |

| Zampelli et al. [28] | ||||

| F/36 | UC | Shallow round ulcers with a central fibrinous membrane, bordered by an erythematous halo on the R lateral tongue and the L buccal mucosa Other PG manifestations Skin ulcerations compatible with PG involving the axillary and submammary areas, the mons pubis, trunk, face, outer ear and extremities |

None | Prednisolone 1 mg/kg die + antibiotics + mesalazine for 10 days, without improvement of lesions. Infliximab infusions were started at 5 mg/kg on weeks 0, 2 and 6 Lesions showed fast healing after initiation of infliximab |

F female, M male, NI not indicated, L left, R right, wks weeks, mo months, yrs years, IM intramuscular, PO per os, IV intravenous, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, RA rheumatoid arthritis, UC ulcerative colitis, PV polycythemia vera, HBP high blood pressure, MGUS monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, MMF mycophenolate mofetil

Table 2.

Epidemiological data

| Number of cases reported (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (n = 20) | |

| Female | 7 (35.0%) |

| Male | 13 (65.0%) |

| Age (n = 20) | |

| <20 years | 1 (5.0%) |

| 20–40 years | 7 (35.0%) |

| 40–60 years | 5 (25.0%) |

| 60–80 years | 4 (20.0%) |

| >80 years | 3 (15.0%) |

| Associated underlying disease (n = 20) | |

| No underlying condition | 4 (20.0%) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 6 (30.0%) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 4 (20.0%) |

| IgA paraproteinemia | 2 (10.0%) |

| Polycythemia rubra vera | 2 (10.0%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (10.0%) |

| Leukemia | 1 (5.0%) |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria | 1 (5.0%) |

| Diverticular disease | 1 (5.0%) |

| Oral pathergy (trauma or surgery) (n = 20) | |

| Yes | 1 (5.0%) |

| No | 19 (95.0%) |

| Sites affected (n = 34) | |

| Tongue | 13 (38.2%) |

| Buccal mucosa | 6 (17.6%) |

| Soft palate | 4 (11.8%) |

| Hard palate | 3 (8.8%) |

| Oropharynx | 2 (5.9%) |

| Lip | 2 (5.9%) |

| Commissure | 2 (5.9%) |

| Retromolar area | 1 (2.9%) |

| Gingiva | 1 (2.9%) |

Discussion

Oral Manifestations of PG

Epidemiological data was available for all patients with intraoral PG. The average age was 48.7 years (±21.86 years). Men were affected more frequently than women, with 65% (13/20) of reported intraoral PG cases affecting males. Oral lesions were reported in the absence of concomitant cutaneous involvement in 20.0% (4/20) of cases [14, 16–18]. The most frequent sites were the tongue, buccal mucosa and soft palate, together representing 67.6% (23/34) of all reported oral lesions. Other lesions involved the hard palate, oropharynx, lip, commissure, gingiva, and retromolar area [5, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20]. Generally, mucosal lesions in the oral cavity were smaller than skin lesions, measuring between 1 and 5 cm in greatest diameter [5, 14, 18, 21–27]. As with skin lesions, the onset is rapid and ulcers develop over the course of 4–8 weeks [12, 14]. Initially, red colored nodules or papulo-pustules can develop. As they rupture, irregularly shaped, painful ulcerations are created. Ulcers present irregular, rolled-out margins and a necrotic, grey or tan colored base. The base of the lesion can be granular and friable leading to frequent bleeding [14]. The edges can be elevated and PG ulcers are often bordered by an erythematous or violaceous halo underlining the inflammatory nature of these lesions [21, 28]. Certain ulcers are covered by an overlying yellow pseudomembrane, and may express purulent discharge [21, 24, 29]. Lesions on the lips can exhibit crusting [16, 29]. Supplementary images of oral PG ulcers showing the variety of morphologic features can be visualized in the case reports [5, 10, 20–23, 29]. Oral and skin lesions in PG are non-indurated. They can be tender to palpation. Pain, dysphagia, sore throat and difficulty in movement are frequently reported complaints with oral PG. In more extensive cases, bone loss and destruction of the periodontal support of adjacent teeth have been reported [14, 24].

Histopathology

Biopsies of oral PG show non-specific histopathological features. Diagnosis is therefore based on the clinical features and exclusion of other causes of oral ulceration. In a case series involving 16 patients with cutaneous PG, 83% of cases were diagnosed based on the clinical features and the exclusion of infectious and neoplastic causes [4]. Reports of extensive ulceration bordered by an overlying fibrinopurulent membrane with heavy neutrophilic infiltration of the lamina propria are consistently seen in biopsied cases [5, 12, 16, 18, 23, 24, 26, 29–32]. Neutrophils can have an altered appearance [20]. A mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells is also reported. Infiltration of lymphocytes can extend into the underlying skeletal muscle [26]. Granulation tissue can be identified when chronic inflammation is present. Vasculitis was observed in one biopsied specimen [10]. However, it is suggested that the presence of vasculitis is secondary to heavy inflammation and is not a direct consequence of PG [8]. Perivascular hyalinization, fibrin deposition, hemorrhage and leukocytoclasia can be present in some lesions [12].

Almost half of microbiological cultures obtained from cutaneous and mucosal ulcers associated with PG are negative for infectious agents [3, 17]. However, secondary infections are common; therefore, a positive culture cannot exclude PG. Immunofluorescence analysis is inconclusive, and does not constitute a useful diagnostic test due to the absence of a humoral autoimmune process in this disease.

Underlying Systemic Diseases Associated with PG

80% (16/20) of patients with oral PG have an underlying systemic disease. Most of these cases (6/16) were associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In fact, PG is an extra-intestinal manifestation in up to 1% of patients with IBD [1]. Other underlying systemic conditions include rheumatoid arthritis, monoclonal gammopathy, myeloproliferative conditions, and other hematological disorders [1, 9, 33–35].

Some cases of cutaneous PG, sometimes accompanied by oral lesions, have been observed in patients with chronic hepatitis [36], acute or chronic leukemia [2, 8, 9, 33, 35], polycythemia rubra vera [10, 25] and refractory anemia [17]. PG was the initial manifestation of leukemia in some cases [35]. Furthermore, in 10–20% of cases, an association with paraproteinaemia was identified [3, 5, 30].

Recently, PG has been included in two distinct auto-inflammatory syndromes, PAPA and PASH [37]. PAPA syndrome results from mutations in the proline-serine-threonine-phosphatase interactive protein 1 (PSTPIP1) and CD2-binding protein 1 (CD2BP1) genes, which cause a triad of pyogenic arthritis, PG and acne [35, 38]. The PASH triad is composed of PG, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis. Recent studies have revealed a heterozygous missense mutation for c.1213 C > T in the PSTPIP1 gene and an increased number of repetitions of the CCTG microsatellite motif in the in the promoter region of this gene in patients with PASH syndrome [37, 39]. Marzano et al. also reported a p.E277D missense mutation of the PSTPIP1 gene in a patient with PA-PASH syndrome (associated pyogenic arthritis) [40]. To date, oral PG lesions have not been reported in the context of theses syndromes.

Although there is no specific diagnostic test for PG, some non-specific markers of inflammation have been found to be elevated in affected patients. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) [5, 17, 27, 29] and C-reactive protein [20–22, 30] have been observed in cases of oral PG. Blood work can be useful to exclude infectious causes and sexually transmitted diseases (ex.: syphilis, herpes, etc.) and to investigate for hematological disorders such as leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts [17]. Autoimmune pathologies can be investigated using serological studies and other pertinent diagnostic tests.

Differential Diagnosis

Oral PG can resemble many different entities such as mucosal tuberculosis, oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, oral squamous cell carcinoma, necrotizing sialometaplasia, oral involvement by T cell lymphoma, traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE), tertiary syphilis, neutropenic ulcers, recurrent major aphthous ulcers, and deep fungal infections (histoplasmosis, mucormycosis, cryptococcosis, blastomycosis). The characteristic features of these conditions are detailed in Table 3 [41–45]. The diagnosis of PG is primarily based on recognition of the characteristic morphology and evolution of the lesion, the presence of an underlying systemic disease (if any) and, the exclusion of other disease processes using proper diagnostic tools. Although histopathological features of oral PG are non-specific, they can be useful for excluding other pathological conditions with a similar clinical appearance.

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of oral PG 41

| Differential diagnosis | Clinical appearance | Histopathologic features | Additional diagnostic workup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mucosal tuberculosis | Chronic ulceration and/or granular swelling of the mucosa Palpable cervical lymph nodes |

Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation Langhans giant cells Mycobacterial organisms revealed by Acid-fast stain |

Chest X-ray PPD test |

| Oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease | Linear vestibular ulcers Cobblestone appearance of the mucosa/mucosal tags Macrocheilitis, angular cheilitis |

Non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation | Fecal calprotectin Colonoscopy Endoscopy |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Strawberry gingivitis Oral ulcerations—later stage |

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, granulomatous inflammation | Elevated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) titers are highly specific |

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | Irregular endo- or exophytic indurated, red, white and/or ulcerated mass Often painless in early stages Sites of predilection: latero-ventral tongue, floor of mouth and soft palate Loco-regional lymphadenopathy |

Invasive malignant squamous cells arising from overlying dysplastic oral epithelium | Chest X-ray Imaging to rule out loco-regional lymphatic metastases PET-scan |

| Necrotizing sialometaplasia | Rapid onset of swelling and pain of the lateral posterior hard palate, followed by the appearance of a crater-like ulceration Regression of the lesion without treatment |

Necrosis of mucous acinar cells with preservation of the lobular architecture of the involved salivary glands Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia | |

| T cell lymphoma | Intraoral involvement is rare and most often preceded by cutaneous lesions Erythematous indurated plaques/nodules that are ulcerated. Tongue, palate and gingiva are most frequently affected |

Atypical lymphocytic cells Pautrier micro-abscesses Extensive, dense infiltrate comprised of atypical lymphocytes Lymphocytic population is CD4+ |

T cell receptor gene rearrangement studies |

| Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia | Deep, chronic ulceration with elevated borders | Polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate with abundant eosinophils in the superficial mucosa and muscle layer Atypical large mononuclear cells (some cases) |

|

| Tertiary syphilis | Syphilitic gumma: Nodular, indurated or ulcerated lesion capable of causing extensive tissue destruction. Palate or tongue are most frequently affected | Peripheral pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulomatous inflammation and multinucleated giant cells | Serologic screening tests: VDRL and RPR |

| Neutropenic ulcers | Ulcerations usually involving the gingival mucosa with or without an erythematous border | Non-specific ulceration Reduced number or absence of neutrophils | Complete blood count |

| Recurrent major aphthous ulcers | Ulcerations on the nonkeratinized mucosa covered by a fibrino-purulent membrane and surrounded by an erythematous halo measuring more than 1 cm in diameter. Very painful Heals with scarring within 3–6 weeks |

Mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate Central zone of ulceration |

Investigate nutritional deficiencies, IBD, hematological disorders, etc |

| Deep fungal infections (histoplasmosi, mucormycosis, cryptococcosis, blastomycosis) | Chronic ulcerations with variable presentations | Granulomatous inflammation Identification of fungal organisms with special stains |

Tissue culture Investigate immune suppression |

Other neutrophilic dermatoses such as Behçet’s disease and Sweet’s Syndrome (SS or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) should also be investigated. SS has a distinct clinical presentation that allows differentiating it from PG. Patients are febrile and present erythematous well-defined and asymmetrical plaques or papules on the skin [46]. Histopathology shows absence of vasculitis, a diffuse perivascular and nodular neutrophilic infiltrate, and various degrees of edema [46, 47]. Mucosal involvement is rare. The diagnosis of Behçet’s disease is based on the identification of one major (2 points) and two minor (1 point each) criteria as suggested by the International Criteria for Behçet’s disease for a total score of 4 and over [48]. Major criteria include recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations, while minor criteria include recurrent aphthous-like genital ulcers, uveitis, retinal vasculitis, and cutaneous lesions such as erythema nodosum, pseudofolliculitis, papulopustular lesions or a positive pathergy test.

The controversial term Malignant Pyoderma (MP) should be avoided in cases of aggressive oral PG. Revised cases of MP have been identified as granulomatosis with polyangiitis [7, 49].

Treatment of Oral Lesions

Treatment of the underlying systemic condition, if any, represents an integral part in the management of oral and skin lesions of PG. Systemic corticosteroids are most commonly used and constitute the first line of immunosuppressive therapy. Oral prednisone, prednisolone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day) and IV methylprednisolone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day) are all effective in treating both oral and cutaneous PG [25, 50, 51]. For the treatment of oral PG, lower dosages of corticosteroids have been effective in treating lesions and preventing relapses [14, 19, 24, 30, 52]. Intralesional triamcinolone injections can complement oral steroids or immunomodulatory drugs [18, 53]. Immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine A (5 mg/kg/day), tacrolimus, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide have also been administered in combination with systemic corticosteroids to induce a prolonged remission period or to reduce treatment duration [5, 29, 54]. Cyclosporine A has been used as the only systemic therapy in some cases [18, 55]. In a recent randomized, observer-blind, parallel group, controlled trial involving 112 patients with cutaneous PG, similar remission rates were reported between groups treated with cyclosporine (4 mg/kg/day) and prednisolone (0.75 mg/kg/day) suggesting that the treatment decision should be based on patient profile and possible adverse effects [55]. Monoclonal antibodies such as Infliximab (anti-TNF-α) and Adalimumab have been suggested as secondary lines of treatment for refractory multifocal disseminated lesions or in cases of multiple organ involvement [13, 28, 56]. In patients diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease, Infliximab is often the therapeutic drug of choice [28, 57, 58]. Some reports of treatment with thalidomide and colchicine demonstrate variable responses [5, 17, 19, 59].

In addition to systemic corticosteroids, local ulcer care is suggested to enhance patient comfort and prevent secondary microbial or fungal infections. Chlorhexidine 0.12% mouth rinse can be used to achieve this in oral PG [21, 24, 31]. Topical clobetasol propionate (Dermovate 0.05%) or Tacrolimus (Protopic 0.1 or 0.03%) can be used as adjuvants to systemic therapy to relieve symptoms [9, 23]. Surgical debridement without concomitant medically induced immunosuppression or pre-operative corticosteroids should be avoided as surgery has been demonstrated to exacerbate cutaneous PG [3, 36, 51, 56, 60]. Similarly, in oral PG, Yco et al. reported that a PG ulcer spread to the adjacent alveolar ridge after a biopsy was undertaken [10]. Recurrence of PG is always possible as 10% (2/20) of cases with oral involvement have shown relapses over a period of time without appropriate maintenance therapy [22, 30]. Low dosage corticosteroids with or without Dapsone can be used as such [14, 29, 34, 61].

Conclusion

PG is an uncommon dermatological condition with very rare oral involvement. Few reports of oral lesions have been documented since the first description of PG by Brunsfing et al. in 1930 [62]. Considering the possible morbidity associated with this disease, recognition and early diagnosis is of great importance. Exclusion of entities with a similar clinical appearance is essential. Clinicians must consider PG as a possible diagnosis for persistent and recurrent oral ulcers of unknown etiology, especially in patients with persistent skin ulcers, an underlying systemic disease known to be associated with PG, and/or when a lesion worsens following biopsy or antibiotic therapy. To guide the clinician in the diagnosis of oral PG lesions, we propose a set of diagnostic criteria based on the important clinico-pathological features gathered from the reported cases (Table 4).

Table 4.

Proposed diagnostic criteria for oral PG lesions–point score system: a scoring of ≥3 points indicates disease

| Necessary criteria: 1 point |

| Large (>1 cm) chronic or recurrent oral ulcers with a granular appearance or undermined, rolled-out reddish-purple irregular margins |

| Major criteria: 2 points each |

| Presence or history of skin lesions diagnosed as PG OR diagnosis of PAPA or PASH syndromes |

| Oral ulceration appears or progresses following minor surgical or traumatic event (pathergy effect) OR progresses following antibiotic therapy |

| Minor criteria: 1 point each |

| Presence of a reddish-purple papule preceding the appearance of an oral ulcer |

| Oral biopsy shows non-specific chronic inflammation (infectious etiologies, vasculitidies, granulomatous inflammatory conditions and neoplastic processes ruled out) |

| Presence of an underlying systemic disorder known to be associated with PG |

| Absence of self-regression or rapid healing following biopsy |

Standardized treatment protocols for mucosal lesions are still lacking and there is no scientific evidence to support the safety of local periodontal or surgical procedures in a patient affected with PG. Surgical dental interventions must be considered as possible triggers of oral lesions in patients diagnosed with cutaneous PG. Therefore, dentists must act with precaution when considering surgery on a patient previously diagnosed with cutaneous PG as research evaluating the risks of inducing oral lesions and the therapeutic modalities to treat such iatrogenically induced lesions are non-existent. Early diagnosis, proper management and consistent follow-up are essential due to the morbidity associated with these lesions and the significant risk of relapse reported in up to 30% of affected patients [14, 24].

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Caroline Bissonnette declares that she has no conflict of interest. Adel Kauzman declares that he has no conflict of interest. Gisele N. Mainville declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Powell FC, Schroeter AL, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. Q J Med. 1985;55(217):173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(11):790–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(6):1000–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiran RP, O’Brien-Ermlich B, Achkar JP, Fazio VW, Delaney CP. Management of peristomal Pyoderma gangrenosum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(7):1397–1403. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0944-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Setterfield JF, Shirlaw PJ, Challacombe SJ, Black MM. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with severe oropharyngeal involvement and IgA paraproteinaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(2):393–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazarus GS, Goldsmith LA, Rocklin RE, Pinals RS, de Buisseret JP, David JR. Pyoderma gangrenosum, altered delayed hypersensitivity and polyarthritis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105(1):46–51. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620040018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(3):395–409. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhat RM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: An update. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3(1):7–13. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.93482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yco MS, Warnock GR, Cruickshank JC, Burnett JR. Pyoderma gangrenosum involving the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(7):765–768. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Ghazal P, Dissemond J. Multilocular Pyoderma gangrenosum after uterus resection. Chirurg. 2012;83(3):254–257. doi: 10.1007/s00104-011-2259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu MK, Asquith P. Oral manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol. 1980;9(2):307–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drinda S, Oelzner P, Codina Canet C, Kaatz M, Wolf G, Hein G. Fatal outcome of Pyoderma gangrenosum with multiple organ involvement and partially responding to Infliximab. Cent Eur J Med. 2006;1(3):306–312. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margoles JS, Wenger J. Stomal ulceration associated with Pyoderma gangrenosum and chronic ulcerative colitis. Report of two cases. Gastroenterology. 1961;41:594–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuboi H. Case of Pyoderma gangrenosum showing oral and genital ulcers, misdiagnosed as Behcet’s disease at first medical examination. J Dermatol. 2008;35(5):289–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goulden V, Bond L, Highet AS. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):271–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Martin A, Arias-Palomo D, Hermida G, Gutierrez-Ortega MC, Ramirez-Herrera M, Rodriguez-Vegas M, et al. Oral Pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(3):663–664. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park HJ, Han BG, Kim YC, Cinn YW. Recalcitrant oral Pyoderma gangrenosum in a child responsive to cyclosporine. J Dermatol. 2003;30(8):612–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley C, Bayoumi AH, Sarkany I. Pyoderma gangrenosum with severe pharyngeal ulceration. J R Soc Med. 1990;83(9):590–591. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poiraud C, Gagey-Caron V, Barbarot S, Durant C, Ayari S, Stalder JF. Cutaneous, mucosal and systemic Pyoderma gangrenosum. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137(3):212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curi MM, Cardoso CL, Koga DH, Zardetto C, Araújo SR. Pyoderma gangrenosum affecting the mouth. Open J Stomatol. 2013;3(2):4. doi: 10.4236/ojst.2013.32026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verma S, Field S, Murphy G. Photoletter to the editor: oral ulceration in Pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5(2):34–35. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2011.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chariatte N, Lysitsa S, Lombardi T, Samson J. Pyoderma gangrenosum (2ème partie): manifestations buccales et présentation d’un cas. Med Buccale Chir Buccale. 2011;17(3):225–235. doi: 10.1051/mbcb/2011116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paramkusam G, Meduri V, Gangeshetty N. Pyoderma gangrenosum with oral involvement: case report and review of the literature. Int J Oral Sci. 2010;2(2):111–116. doi: 10.4248/IJOS10032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertram-Callens A, Machet L, Vaillant L, Camenen I, Lorette G. Buccal and ocular localizations of Pyoderma gangrenosum in Vaquez’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;118(9):611–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy KS, Prendergast ML, Sooy CD. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the oral cavity, nose, and larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97(5):487–490. doi: 10.1177/019459988709700510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yusuf H, Ead RD. Pyoderma gangrenosum with involvement of the tongue. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23(4):247–250. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(85)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zampeli VA, Lippert U, Nikolakis G, Makrantonaki E, Tzellos TG, Krause U, et al. Disseminated refractory pyoderma gangraenosum during an ulcerative colitis flare. Treatment with infliximab. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9(3):62–66. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2015.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Attas KM, Ahsan MK, Buraik M, Gamal AM, Hannani HY. Fatal pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: case report. J Saudi Soc Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2013;17(2):4. doi: 10.1016/j.jssdds.2013.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isomura I, Miyawaki S, Morita A. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with nasal septal perforation, oropharyngeal ulcers and IgA paraproteinemia. J Dermatol. 2005;32(3):193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaomongkolgit R, Subbalekha K, Sawangarun W, Thongprasom K. Pyoderma gangrenosum-like oral ulcerations in an elderly patient. Gerodontology. 2015;32(4):309–313. doi: 10.1111/ger.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddiqui S, Fiorillo M, Tismenetsky M, Spinnell M. Isolated oral Pyoderma gangrenosum following proctocolectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:S517–S518. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Callen JP, Taylor WB. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a literature review. Cutis. 1978;21(1):61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philpott JA, Jr, Goltz RW, Park RK. Pyoderma gangrenosum, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes mellitus. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94(6):732–738. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1966.01600300056012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeFilippis EM, Feldman SR, Huang WW. The genetics of Pyoderma gangrenosum and implications for treatment: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(6):1487–1497. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolkachjov SN, Fahy AS, Wetter DA, Brough KR, Bridges AG, Davis MD, et al. Postoperative Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): the Mayo Clinic experience of 20 years from 1994 through 2014. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, Ruzicka T. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH): a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong JB, Su YN, Chiu HC. Pyogenic arthritis, Pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne syndrome (PAPA syndrome): report of a sporadic case without an identifiable mutation in the CD2BP1 gene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(3):533–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calderon-Castrat X, Bancalari-Diaz D, Roman-Curto C, Romo-Melgar A, Amoros-Cerdan D, L AA-M, et al. PSTPIP1 gene mutation in a Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/bjd.14383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marzano AV, Trevisan V, Gattorno M, Ceccherini I, De Simone C, Crosti C. Pyogenic arthritis, Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (PAPASH): a new autoinflammatory syndrome associated with a novel mutation of the PSTPIP1 gene. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(6):762–764. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 4. St. Louis: W. B. Saunders; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirshberg A, Amariglio N, Akrish S, Yahalom R, Rosenbaum H, Okon E, et al. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia: a reactive lesion of the oral mucosa. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(4):522–529. doi: 10.1309/AFHA406GBT0N2Y64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sirois DA, Miller AS, Harwick RD, Vonderheid EC. Oral manifestations of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. A report of eight cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75(6):700–705. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener’s granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(10):739–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang WC, Chen JY, Chen YK, Lin LM. Tuberculosis of the head and neck: a review of 20 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(3):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/bjd.13955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Ammar M, Boudaya S, Khabir A, Boudawara T, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ijd.13232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The International Criteria for Behcet. ’. s Disease (ICBD) A collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(3):338–347. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibson LE, Daoud MS, Muller SA, Perry HO. Malignant pyodermas revisited. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(8):734–736. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63593-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reichrath J, Bens G, Bonowitz A, Tilgen W. Treatment recommendations for Pyoderma gangrenosum: an evidence-based review of the literature based on more than 350 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2):273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zuo KJ, Fung E, Tredget EE, Lin AN. A systematic review of post-surgical Pyoderma gangrenosum: identification of risk factors and proposed management strategy. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68(3):295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marzano AV, Alberti-Violetti S, Crippa R, Angiero F, Tadini G, Crosti C. Pyoderma gangrenosum with severe cutaneous and oral involvement. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(2):257–258. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snyder RA. Pyoderma gangrenosum involving the head and neck. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(3):295–302. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1986.01660150073019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baloch BK, Baloch SK, Kumar S, Mansoor F, Jawad A. Orogenital ulcers of Pyoderma gangrenosum resembling sexually transmitted disease. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2014;24(Suppl 3):S207–S208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ormerod AD, Thomas KS, Craig FE, Mitchell E, Greenlaw N, Norrie J, et al. Comparison of the two most commonly used treatments for Pyoderma gangrenosum: results of the STOP GAP randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2015;350:h2958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, Lakatos PL, Navarini A, Rogler G. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(8):1982–1992. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MG, Shetty A, Bowden JJ, Williams JD, Griffiths CE, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of Pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55(4):505–509. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agarwal A, Andrews JM. Systematic review: IBD-associated Pyoderma gangrenosum in the biologic era, the response to therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(6):563–572. doi: 10.1111/apt.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ambooken B, Khader A, Muhammed K, Rajan U, Snigdha O. Malignant Pyoderma gangrenosum eroding the parotid gland successfully treated with dexamethasone pulse therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(12):1536–1538. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ye MJ, Ye JM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of clinical features and outcomes of 23 cases requiring inpatient management. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:461467. doi: 10.1155/2014/461467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller J, Yentzer BA, Clark A, Jorizzo JL, Feldman SR. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review and update on new therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(4):646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (echthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1930;22(4):655–680. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1930.01440160053009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]