Introduction

Most adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) die from their disease despite achieving initial complete remission (CR), including those treated with aggressive multi-agent chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Numerous phase I, II and III clinical trials of both novel and conventional agents have failed to improve overall survival for older patients and the five-year survival for younger patients is still only about 40%. Thus, it is obvious in the clinic that certain leukemic cells must be fundamentally resistant to our currently available armamentarium of chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation. Laboratory data suggest that AML originates from a rare population of cells, termed leukemic stem cells (LSCs) or leukemia-initiating cells, which are capable of self-renewal, proliferation and differentiation into malignant blasts. At least some of these cells persist after treatment and are probably responsible for disease relapse. Clinical data show that for patients in morphologic CR, the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD), as detected by sensitive flow cytometric assays, predicts for disease relapse in AML. Furthermore, a high stem cell frequency at diagnosis predicts for increased MRD and poor prognosis.1 The biology of LSCs has been extensively investigated and several unique properties have been identified and will be discussed below. Still, the similarities and differences between LSCs, the leukemia-initiating cells responsible for the original disease presentation and the residual leukemia cells detected after treatment in MRD assays are not fully understood. The objective of this review is to describe ongoing bench and translational research in LSCs and MRD in AML and to propose how these data should be used to change the direction of developmental therapeutics and clinical trials.

Models of Leukemogenesis

AML is a cell autonomous, or intrinsic disorder in which the genetic events leading to malignant transformation of a hematopoietic cell are found within that cell and are both necessary and sufficient for the generation of leukemia.2 Insertion of disease-specific alleles into normal bone marrow cells or myeloid progenitors results in transformation to AML, with recapitulation of the disease phenotype in murine models.2,3 Abundant data suggest functional heterogeneity among leukemic cells, with a largely quiescent stem cell population of LSCs capable of endless self-renewal, a progenitor population with more limited potential and a population of leukemic blasts without this potential. This is analogous to the hierarchical structure of normal hematopoiesis. There is substantial evidence that leukemias arise from a malignant counterpart to normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or progenitor cells that has been transformed due to genetic and/or epigenetic aberrations.4 LSCs have been identified in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), AML and ALL. Fialkow et al. showed 30 years ago that a common stem cell gave rise to the malignant granulocytes and erythrocytes in CML.5 In 1994, Lapidot et al. reported that a small subpopulation of cells was able to recapitulate leukemic disease when xenotransplated into an immunodeficient mouse.6 Subsequently, Bonnet and Dick studied multiple subtypes of AML and identified a rare subpopulation of immature CD34+/CD38− cells that was able to serially regenerate leukemia in a mouse xenograft model.7 Normal HSCs share this immunophenotype, suggesting that these cells were the targets of malignant transformation7, but other work has shown that malignant transformation of a committed progenitor after transduction with leukemia-associated oncogenes may also give rise to leukemia.3,8

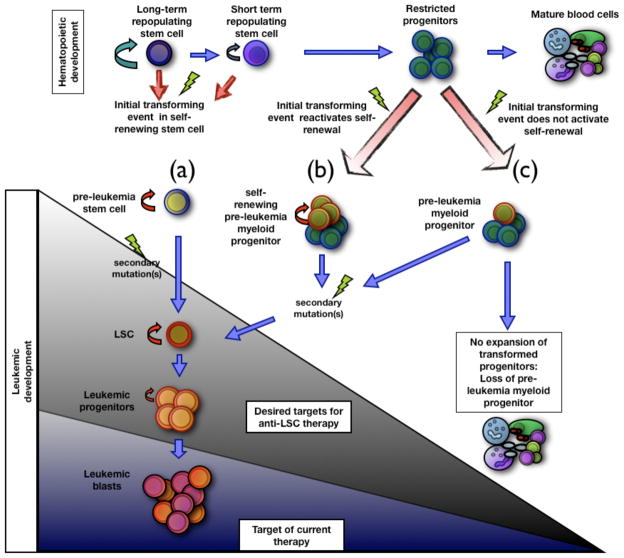

Additional data support a multi-step transformation process, with an initial event in a stem cell creating a pre-leukemic LSC, followed by subsequent mutations at either the stem or progenitor level giving rise to overt disease.9–11 For example, in phenotypically primitive cells (CD34+CD38-CD90+) isolated from patients with t(8;21) AML in remission, it was shown that even though AML-ETO transcripts were detected, the cells formed normal multi-lineage colonies with no disease phenotype. In contrast, more mature cells (CD34+CD38+) gave rise to leukemic blast cells.10 Numerous mutations have been described in AML, including characteristic chromosomal translocations (e.g. (9;22), (8;21), etc.), which result in chimeric fusion proteins that affect proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. The genes which encode transcription factors regulating normal hematopoietic survival, self-renewal and differentiation are located at chromosomal loci where translocations occur and alterations in the activation and suppression of these factors are critical in the development of leukemia12. Still, it is not known whether these mutations occur in stem cells or more differentiated progenitors. LSCs also demonstrate cellular heterogeneity, with different clones having long-term (LT) and short-term (ST) repopulating capabilities in murine models.13 LSCs give rise to daughter blast cells, which are the hallmark of the disease and responsible for its clinical manifestations. Though LSCs are capable of self-renewal, they are mostly quiescent in the G0 phase of the cell cycle and, thus, resistant to many conventional chemotherapy drugs. Fundamentally, AML is a heterogeneous disease comprised of both stem, progenitor and blast populations which are biologically distinct and must be targeted separately. A schematic representation of stem cell leukemogenesis is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Models for leukemia development and therapeutic targets.

The figure represents three possible scenarios of leukemia stem cell transformation. (a) A self-renewing hematopoietic stem cell transforms by an oncogenic event to give rise to a pre-leukemia stem cell that, over time, can give rise to a fully transformed leukemia stem cell (LSC). (b) A restricted progenitor can be transformed by a mutation that confers self-renewal. The pre-leukemia stem cell progenitor is maintained and, with further mutations, gives rise to a LSC. (c) A first mutation in a restricted progenitor does not promote self-renewal. In the absence of secondary mutations, the pre-malignant cell is lost and does not give rise to a LSC. Two possible therapeutic outcomes are also depicted by the shaded triangles, showing the cells targeted by two therapeutic regimens: (1) leukemic blasts (blue shaded region); and (2) leukemic blasts, stem, progenitors cells, and potentially pre-leukemic cell types (entire triangle). LSC: Leukemic stem cell.

LSC biology and unique therapeutic targets

The LSC compartment consists of 0.1–1% of AML blasts with frequencies in the range of 1:100,000 to 1:10 million.7 Larger LSC populations at diagnosis are a poor prognostic indicator14, but even a “large” population is actually only a tiny subgroup of cells. Yet, this tiny compartment indefinitely perpetuates the disease and, given their resistance to even the harshest of therapies, it is not surprising that LSCs have unique biological properties with intricate mechanisms to promote their own growth and survival. Aberrant surface phenotype, dysregulated cell autonomous programs for survival, apoptosis and differentiation, and interactions with the surrounding bone marrow microenvironment are all potentially specific LSC characteristics that can be preferentially exploited as therapeutic targets and are described below.

Aberrant surface phenotype

The surface immunophenotype of LSCs and normal HSCs have similarities and differences which are important for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The immunophenotype CD34+/CD38− defines primitive, multipotential HSCs that can repopulate all hematopoietic lineages, while CD34+/CD38+ cells constitute a committed myeloid progenitor population. HSCs are lineage negative (lin-), CD34+/CD38-/CD13-/CD33+/CD90+/CD123-lo/CD117+/CD71+.15 Not all LSCs are CD34+/CD38-, e.g. in the case of CD34− AML.1 Unlike HSCs, LSCs do not usually express CD90 (Thy-1), CD117 (c-Kit), and HLA-DR, but are positive for CD123 (the IL-3 receptor α-subunit), CD96 (member of the immunoglobulin superfamily), CD44 (an adhesion molecule) and CLL-1 (C-type lectin-like molecule-1), a putative signaling receptor found on monocytes and granulocytes, but not normal HSCs.16–20

The differences between LSC and HSC surface antigen expression are, unfortunately, not absolute and there are substantial areas of overlap. Nonetheless, surface antigens are an attractive and “druggable” therapeutic target and naked and conjugated monoclonal antibodies with favorable toxicity profiles already exist with significant activity in several hematologic malignancies, including AML. CD33 is a marker of early myeloid differentiation present on the majority of AML blasts, normal hematopoietic progenitors and HScs; its presence on LSCs and HSCs is a matter of debate.21–23 Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO), a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody linked to calicheamicin, an antitumor antibiotic resulted in a remission rate of approximately 30% in patients with relapsed AML and the drug has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients > 60 years in first relapse.24,25 As described above, GO is not specific for LSCs and causes significant myelosuppression.

The human interleukin receptor 3 (IL-3) is a heterodimer composed of α and β subunits. The IL-3 receptor α-subunit (CD123) is highly expressed on LSCs and AML blasts. A novel recombinant diphtheria toxin (DT388) liked to IL-3 has shown selective targeting of AML progenitors in animals models and modest clinical activity in patients.26,27 DT388IL-3 targets a functional IL-3 receptor and is most effective when both the α and β subunits are present.28 A novel immunotoxin that can induce cell death in AML cells that only express the IL-3 α-subunit is under development, as are monoclonal anti-CD123 antibodies.29

The LSC niche

Normal HSCs reside in a highly complex hematopoietic niche, functionally and anatomically defined into endosteal and vascular compartments, in which there are critical, bi-directional signals responsible for HSC survival, self-renewal and differentiation.2 The microenvironment is regulated by a multi-functional network of hematopoietic growth factors (e.g. SCF, LIF, IL-3, IL-6, Flt3-ligand, TPO), signaling pathways (e.g. Wnt, Notch), cell cycle regulators (e.g. p18 and p21 inhibitors, p53) and transcription factors (e.g. SCF/TEL-1, RUNX1, HOXB4).12,30 Aberrant microenvironment signaling has been shown to produce disease pathology, including myelofibrosis and myeloproliferative disorders.2

Recent data suggest that LSCs are also niche-dependent and xenograft transplantation assays support the role of niche signaling in LSC engraftment, chemotherapy resistance and cell cycle regulation.2,31 In vivo dynamic imaging models show that LSCs interact extensively with normal HSCs and other bone marrow cells to create a tumor microenvironment which favors their survival.30 Leukemic cells release self-stimulatory soluble factors (autocrine regulation), as well as harness others from the adjacent endothelium and niches (paracrine regulation) to facilitate their own growth and proliferation.32,33 Furthermore, they usurp normal hematopoietic progenitor niches, suppress normal hematopoiesis and recruit normal CD34+ cells into the malignant niche.30

Targeting the LSC niche could deliver a major, hopefully lethal blow to a variety of LSC survival mechanisms and may allow bypassing of cell instrinsic mechanisms of resistance, such as multidrug resistance efflux pumps and a large assortment of mutant alleles.2,15 The challenge of this approach is obviously that it must not disrupt the delicate relationships between the niche and normal hemtopoietic cells. Novel agents able to inactivate Wnt, Notch, HOX and other potential niche regulatory pathways are under development.12 Interactions between CXCR4 (CXC chemokine receptor-4) and SDF-1 (stromal cell-derived factor-1, CXCL12) are critical for the homing and retention of HSCs and progenitors to the hematopoietic niche and can lead to upregulation of the adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and VLA-4.2 Homing to the microenvironment also appears to be important for LSC survival and the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis promotes leukemic cell homing, as well as in vivo growth.34 LSCs may be able to hijack normal homing pathways and cause up-regulation of VLA-4. Of note, patients with undetectable VLA-4 levels on leukemic blasts responded well to chemotherapy35 and CXCR4 expression on AML blasts is a poor prognostic indicator.36 The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib inhibited migration of AML blasts to stromal-cell derived SDF-1, the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3465 prevented the chemoprotective effects of stromal cell-leukemia interaction and neutralizing antibodies against CXCR4 or SDF-1 diminished AML cell survival and engraftment in NOD-SCID mice.2,34,37,38

CD44 is an adhesion molecule and the receptor for osteopontin, an extracellular matrix component of the endosteal niche. Targeting of CD44 with an activating monoclonal antibody (H90) eradicated LSC in an in vivo NOD-SCID model by preventing their trafficking to supportive microenvironments in both the bone marrow and spleen. Activation of CD44 also promoted differentiation.20 Overexpression of CD44-6v, a variant particularly overexpressed on leukemic CD34+CD38− cells, is a poor prognostic indicator. 39

Self-renewal

Targeting self-renewal, the process by which stem cells divide and generate progeny with the same developmental potential as the original cell, is another strategy to eradicate LSCs, but unlocking the secrets of both normal HSC and LSC self-renewal has been elusive. Many signaling pathways, including HOX (homeobox), Notch, Hedgehog and Wnt/β-Catenin, have been implicated in HSC self-renewal. These developmental regulators bind to cell-surface receptors, which activate signaling pathways and lead to the translocation of transcription factors from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. The transcription factors (GATA2, p53, ZFX, others), in turn, interact with other cell-specific transcription factors to regulate self-renewal.40 All these pathways may also be dysregulated in leukemia.

HOX genes are dysregulated in AML and have been linked to LSC self-renewal and AML pathogenesis, but downstream target genes of HOX are unclear.41,42 The caudal-type homeobox transcription factor (CDX)2 is a known regulator of HOX that is aberrantly expressed in AML and absent in normal HSCs and progenitors.43 Over-expression of CDX2 was shown to be an important promoter of LSC self-renewal in vitro and CDX2 silencing by RNA interference inhibited growth and colony formation of AML cell lines.43

The WNT/β-Catenin pathway has important roles in HSC and LSC renewal and is constitutively activated in AML.44 Higher levels of WNT signaling may be related to increased Flt-3 signaling in patients with mutations or amplifications of Flt-345; internal tandem duplications of Flt-3 have been associated with an adverse prognosis in AML. High-throughput screening has identified several potential small molecules that could interfere with β-catenin binding.46 Zhao et al. recently showed that loss of Smoothened (Smo), an essential component of the Hedgehog pathway, impaired hematopoietic stem cell renewal and decreased induction of CML by the BCR-ABL1 oncoprotein, suggesting that Hedgehog pathway activity is essential for maintenance of normal and malignant stem cells.47 The gene Bmi-1 has also been shown to mediate self-renewal in both normal and leukemia stem cells and is a potential therapeutic target.48,49

Survival and apoptosis

Several signaling pathways appear to play important roles in controlling LSC survival and may be selectively targeted. NF-κB, a transcription factor complex that is constitutively active in most hematologic malignancies and directly linked to increased growth and survival, has increased activity in LSCs, but not in HSCs.50 Under normal conditions, NF-κB is kept out of the nucleus by interaction with its own inhibitor, IκBα. Upon stimulation, a series of events results in the phosphorylation, ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of IκBα, after which NF-κB translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of a variety of genes.51 Primary CD34+ AML cells and LSCs show constitutive NF-κB activity, but unstimulated CD34+ progenitor cells do not, suggesting that NF-κB inhibition may be an important therapeutic target. In other tumors, loss of NF-κB is associated with increased apoptosis and sensitivity to chemotherapy. However, the commonly used AML chemotherapeutics (cytarabine, anthracyclines, etc.) actually upregulate, rather than inhibit NF-κB, providing a survival advantage to the malignant cells.52,53

Proteasome inhibitors, which inhibit IκB degradation, have been shown to induce apoptosis in AML cells while sparing normal progenitors.50 These drugs have limited single-agent activity in patients with AML, but may be synergistic with anthracyclines by increasing proapoptotic p53 while decreasing NF-κB.54 Combination of the proteasome inhibitor carbobenzoxyl-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-leucinal (MG-132) with the anthracycline idarubicin induced rapid and extensive apoptosis of LSCs, sparing normal HSCs, via inhibition of NF-κB and activation of p53-regulated genes.55 Clinical trials combining anthracyclines and proteasome inhibitors in AML induction have been initiated.

The sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide (PTL), derived from a medicinal plant called feverfew, targets AML LSCs via inhibition of NF-κB, induction of oxidative stress and activation of p53.56 In vitro, PTL preferentially targets LSCs, while sparing normal HSCs. The clinical utility of PTL has been limited by poor pharmacologic properties, but an orally bioavailable analog, dimethylaminoparthenolide (DMAPT, LC-1) has been identified. DMAPT has activity against LSCs and inhibits NF-κB in vivo; it is currently being tested in a phase I clinical trial in AML.57

A second important signaling pathway for LSC survival involves PI3 kinase and its components, including PTEN (phosphatase and TENsin homolog deleted on chromosome 10), Akt, and mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin). The pathway affects several downstream proteins and may activate NF-κB under some circumstances.58 PTEN is a negative regulator of the pathway and is mutated or inactivated in certain leukemias, resulting in increased activation of Akt and mTOR and expansion of LSCs in murine models.59,60 Constitutive PI3 kinase activity has been reported in primary AML samples and is strongly associated with proliferation, survival, anti-apoptotic responses and drug resistance.61,62 Several studies have reported decreased LSC after treatment with PI3 kinase inhibitors, e.g. Wortmannin, and mTOR inhibitors, e.g. rapamycin.63–65 Interestingly, upregulation of PI3 kinase was also shown to be favorable in some cases of de novo AML, possibly by forcing LSCs into S-phase and making them more susceptible to cytotoxic chemotherapy.66

TDZD-8 (4-Benzyl-2-methyl-1,2,4-thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione) was originally developed as an inhibitor of GSK-3β. Recently, it has been shown to be selectively cytotoxic to primary LSCs from AML and other leukemias within 2 hours after drug exposure and without apparent toxicity to normal HSCs. The mechanism of action is not completely understood, but may involve induction of oxidative stress and inhibition of NF-κB, as well as inhibition of several kinases involved in growth and survival functions, such as PKC family members, Akt, FLT3 and Aurora B.67

Anti-apoptotic proteins are commonly upregulated in cancers and inhibitory molecules for Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl have been developed as a strategy for selectively targeting malignant cells. High expression of both pro- and antiapoptotic genes in AML at diagnosis has been associated with a poor clinical outcome, which the authors propose is associated with the concept of oncogenic addiction, in which upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins leads to increased binding of activator proapoptotic proteins, which eventually leads to increased activation of the whole apoptosis pathway.68 ABT-737, an inhibitor that mimics BH3-domain molecules, selectively kills primary leukemia cells and LSCs.69,70

Expert Commentary

Finding LSCs in the clinic

A search of PubMed (www.pubmed.gov) on May 1, 2009 for “leukemia stem cells” yielded 16,931 references since 1958 and there have been many excellent reviews on the subject, a few with well over 100 references each.12,15,71–73 Clinicians, not to mention patients, reading these manuscripts must certainly have the impression that curing AML is imminent but, unfortunately, there is still tremendous disparity between scientific progress and clinical outcomes. AML, like most cancers, is substantially easier to cure in mice than in humans and almost all work with LSCs has been dependent on murine models to functionally characterize the cells. We need to find LSCs, or an accepted surrogate for them, in real-time, in the clinic.

As reviewed above, leukemic blasts and LSCs are phenotypically and biologically distinct cell populations that, ideally, must be targeted separately, but simultaneously during AML treatment. Furthermore, both populations coexist, in varying proportions, with normal HSCs which should be spared during treatment. To make matters even more complicated, the “normal” hematopoietic progenitors co-exist with leukemic cells and may share and/or acquire phenotypic and biological characteristics resembling those of their malignant counterparts, making them more difficult to distinguish and selectively target. Finally, though it is increasingly obvious from immunophenotypic and molecular studies of minimal residual disease (MRD) that most patients with AML have measurable disease burden even while in morphologic remission, there are no direct data proving whether the leukemic cells left-over after treatment are the same as those that initiated or propagated the disease. Therefore, until there are novel strategies to completely eradicate AML at the time of diagnosis, it is also critical to molecularly and biologically characterize the residual leukemic cells and “normal” HSCs left after treatment and not assume that their properties, including susceptibility (or lack thereof) to various treatments, is the same as at diagnosis.

Isolation of putative LSCs has become increasingly feasible, especially with multiparameter flow cytometry to identify aberrant LSC surface antigens, but is still far from a standard clinical tool. Its sensitivity may be augmented by other assays typically used to identify and isolate stem cell populations, such as aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity74,75 and studies of a so-called side population (SP) of cells, defined by high extrusion of the DNA-binding drug Hoechst 33342, which contains the leukemia-initiating cells.76 With the identification of characteristic surface markers in LSCs, it has been possible to isolate cells to perform more elegant assays focused on this subpopulation, including gene expression assays77,78 and gel shift assays to determine the binding activity of transcription factors50. Going forward, given advancements in RNAi technology, more studies involving genetic perturbation of primary cells to assess specific gene functions, as well as the proteomic, microRNA and epigenetic consequences of these perturbations can be examined in populations enriched for LSCs.

As LSCs represent only a tiny fraction of the blast population, they are especially difficult to identify after treatment. Patients with abnormal cytogenetics are followed post-treatment for persistent karyotypic or FISH abnormalities and those with characterstic fusion-genes can be followed using quantitative PCR; these are all of prognostic importance. Gene mutations, such as FLT-3/ITD, NPM1 and CEBPA are also targets for MRD analysis using PCR.79 The flow cytometric techniques for identifying MRD after treatment are readily available, but neither quantitative nor qualitative immunophenotypic measurements of MRD are standard yet as part of post-treatment follow-up for AML. Aberrant patterns of antigen expression on leukemic blasts, including aberrant cross-lineage marker expression, asynchronous expression and increased or decreased marker expression, can be used to define a leukemia-associated phenotype (LAP) for AML patients at diagnosis, which can then be used to track the malignant population in follow-up examinations.80 Importantly, Van Rhenen et al. have demonstrated that LAPs are also present on the CD34+/CD38− stem cell compartment, thus allowing putative LSCs to be detected by flow cytometry in patients in complete remission.80

Five-year view

Novel clinical trial designs may be as important as novel therapies in AML

The current model of AML treatment generally involves multi-agent chemotherapy to induce remission, followed by some sort of post-remission treatment, either chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation, based on the patient’s age, performance status, cytogenetics and the presence or absence of increasingly understood molecular abnormalities, such as FLT-3 and NPM1. An attempt is often made to offer older patients, who represent the majority of patients with AML, “lower intensity” treatment, in an effort to reduce the unacceptably high up-front mortality associated with conventional induction for those with very advanced age and/or poor performance status. While selected patients have been shown to achieve remission with less toxicity using single drugs, such as low-dose cytarabine, hypomethylating agents and new purine analogs, so far, none has shown consistent, convincing superiority over the anthracycline/cytarabine backbone used for the past 30 years. Repeated cycles of consolidation chemotherapy confer a survival advantage to younger patients with AML, but not necessarily for those over 60 years.81

Improved understanding of AML pathobiology has led to the use of several agents with different mechanisms of action, such as flt-3 (fms-like tyrosine kinase) inhibitors and farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs). Flt-3 is a receptor tyrosine kinase normally expressed on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, where it plays roles in survival, proliferation and differentiation.82 Activating mutations of FLT3 occur in approximately one-third of AML patients and consist of two major types: internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations of 3–400bp that map to the juxtamembrane region (23% of AML patients) and point mutations that most frequently involve aspartic acid 835 of the kinase domain (8–12% of AML patients). The presence of ITD mutations has been associated with a poor prognosis in many studies. Several FLT3 inhibitors have shown modest single-agent activity and favorable toxicity profiles in clinical trials and studies in combination with chemotherapy in newly diagnosed and relapsed patients are ongoing.

Activating mutations of RAS are found in 10–30% of AML blasts and confer proliferative and survival advantages. Ras signaling requires the post-translational addition of a farnesyl lipid moiety to the cysteine residue of the C-terminal CAAX motif via FT in a process called prenylation. FTIs prevent activation of RAS by preventing membrane attachment and further signal transduction.83 Clinical trials of FTIs are ongoing, again with limited single-agent efficacy.

A dizzying number of mutations, molecular abnormalities, transcription factors, signaling pathways, survival mechanisms and other properties have been identified as important in the growth and propagation of AML, suggesting a complex pathogenesis unlikely to be successfully targeted by a single agent. Yet, over and over again, novel agents identified on the basis of sophisticated laboratory studies of AML pathophysiology fail to do much in the clinic. Clinical trials in leukemia, as in most of oncology, generally offer novel agents to patients with relapsed and refractory disease, obviously the most difficult group to treat and the least likely to respond to any treatment. Also, as the novel agents become increasingly “targeted” and narrow in their proposed mechanisms of action, a feature always hoped to be favorable from a toxicity perspective, they seem to be less able to handle the clinical features of full-blown AML and are often designated as more useful in “smoldering” or “low-burden” disease. Thus, many novel agents in acute leukemia die early in development and may never be tested in the correct target population because, even though phase I trials are not technically designed to assess efficacy, it is often difficult to generate the enthusiasm and financial resources for further development of agents which show insignificant clinical responses in early testing. Although it is true that up-front remission rates in leukemia are not ideal, >70% of younger patients and >50% of selected older patients with AML are expected to attain first remission. These patients, who are almost all at high risk of relapse, should be targeted for clinical trials of novel agents, but there are very few clinical trials designed for patients in remission. Interestingly, while so-called maintenance chemotherapy, which generally refers to low-dose cytotoxic chemotherapy administered for months or years to patients in remission, has been widely accepted as effective in ALL, it is not generally used in AML because clinical trials have shown only modest improvements in relapse-free survival and no improvement in overall survival.84 Unfortunately, most of these trials did not have correlative laboratory work. Almost all studies of molecular diagnostics or MRD in AML end with a statement advocating frequent assessments so that “risk-adapted” therapy can be offered. The problem is that currently allogeneic stem cell transplant is really the only therapeutic intervention that can alter outcome for patients deemed “high risk”, but this procedure is not feasible for the majority of patients with AML due to lack of donor availability or medical comorbidities. It is absolutely ethical to offer novel therapies, including phase I trials, to patients in high-risk first remission or beyond in an effort to forestall almost inevitable relapse and recent reviews of LSCs can serve as a template where to begin.

Targets for anti-LSC therapies

| Target | Method | Clinical trial for AML | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-based therapies | |||

| CD123 | DT388IL-3 | phase I/II | 19,85 |

| CD123 | CSL360 (anti-CD123 mAb) | Phase I | 19,86 |

| CD33 | Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) | phase I/II; phase III | 24,25 |

| CD44 | huARH460-16-2 | N/A | 20 |

| CLL-1 | under development | N/A | 17 |

| CD96 | N/A | N/A | 18 |

| Molecular targets | |||

| Flt3 | MLN-518/tandutinib; PKC412/midostaruin; CEP-701/lestaurtinib; Su-11248 (sutent) | phase I; phase I/II | 87 |

| PI3K pathway | Rapamycin; Everolimus | phase I | 61,88 |

| NF-kB | Proteasome inhibition: Bortezomib | phase I | 50,55 |

| Other | DMAPT (parthenolide analog) | phase I | 56,57 |

| Microenvironment, self-renewal and differentiation | |||

| CXCR4 | AMD3100 | Phase I; Phase II | 34,36 |

| Notch | inhibitors in clinical trials for other solid tumors | N/A | 89 |

| Hedgehog | inhibitors in clinical trials for other solid tumors | N/A | 47,90 |

| Wnt | inhibitors in clinical trials for other solid tumors | N/A | 91 |

Box 1. Phenotypic markers of leukemic and normal hematopoietic stem cells.

| Leukemia stem cell | Hematopoietic stem cell |

|---|---|

| CD34+ | CD34+ |

| CD38−* | CD38− |

| HLA-DR− | HLA-DR |

| CD90+ | CD90− |

| CD117− | CD117+ |

| CD123+ | CD123− |

| CLL-1+* | CLL-1− |

| CD96+ | CD96− |

| CD47++ | CD47+ |

Not all cases

References

- 1.Moshaver B, van Rhenen A, Kelder A, et al. Identification of a small subpopulation of candidate leukemia-initiating cells in the side population of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells. 2008;26:3059–3067. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane SW, Scadden DT, Gilliland DG. The leukemic stem cell niche - current concepts and therapeutic opportunities. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-202606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huntly BJ, Shigematsu H, Deguchi K, et al. MOZ-TIF2, but not BCR-ABL, confers properties of leukemic stem cells to committed murine hematopoietic progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:587–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner JK, Wang JC, Takenaka K, et al. Direct evidence for cooperating genetic events in the leukemic transformation of normal human hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2005;19:1794–1805. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fialkow PJ, Jacobson RJ, Papayannopoulou T. Chronic myelocytic leukemia: clonal origin in a stem cell common to the granulocyte, erythrocyte, platelet and monocyte/macrophage. Am J Med. 1977;63:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krivtsov AV, Twomey D, Feng Z, et al. Transformation from committed progenitor to leukaemia stem cell initiated by MLL-AF9. Nature. 2006;442:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature04980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan Y, Zhou L, Miyamoto T, et al. AML1-ETO expression is directly involved in the development of acute myeloid leukemia in the presence of additional mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10398–10403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171321298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyamoto T, Weissman IL, Akashi K. AML1/ETO-expressing nonleukemic stem cells in acute myelogenous leukemia with 8;21 chromosomal translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7521–7526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong D, Gupta R, Ancliff P, et al. Initiating and cancer-propagating cells in TEL-AML1-associated childhood leukemia. Science. 2008;319:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1150648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsiftsoglou AS, Bonovolias ID, Tsiftsoglou SA. Multilevel targeting of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, differentiation and apoptosis for leukemia therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hope KJ, Jin L, Dick JE. Acute myeloid leukemia originates from a hierarchy of leukemic stem cell classes that differ in self-renewal capacity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:738–743. doi: 10.1038/ni1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rhenen A, Feller N, Kelder A, et al. High stem cell frequency in acute myeloid leukemia at diagnosis predicts high minimal residual disease and poor survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6520–6527. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan WI, Huntly BJ. Leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:326–335. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blair A, Hogge DE, Ailles LE, Lansdorp PM, Sutherland HJ. Lack of expression of Thy-1 (CD90) on acute myeloid leukemia cells with long-term proliferative ability in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 1997;89:3104–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Rhenen A, van Dongen GA, Kelder A, et al. The novel AML stem cell associated antigen CLL-1 aids in discrimination between normal and leukemic stem cells. Blood. 2007;110:2659–2666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-083048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosen N, Park CY, Tatsumi N, et al. CD96 is a leukemic stem cell-specific marker in human acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11008–11013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704271104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan CT, Upchurch D, Szilvassy SJ, et al. The interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain is a unique marker for human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Leukemia. 2000;14:1777–1784. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin L, Hope KJ, Zhai Q, Smadja-Joffe F, Dick JE. Targeting of CD44 eradicates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1167–1174. doi: 10.1038/nm1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taussig DC, Pearce DJ, Simpson C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:4086–4092. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauswirth AW, Florian S, Printz D, et al. Expression of the target receptor CD33 in CD34+/CD38-/CD123+ AML stem cells. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearce DJ, Taussig DC, Bonnet D. Implications of the expression of myeloid markers on normal and leukemic stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:271–273. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.3.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson RA, Boogaerts M, Estey E, et al. Antibody-targeted chemotherapy of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse using Mylotarg (gemtuzumab ozogamicin) Leukemia. 2002;16:1627–1636. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sievers EL, Larson RA, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Efficacy and safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3244–3254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankel A, Liu JS, Rizzieri D, Hogge D. Phase I clinical study of diphtheria toxin-interleukin 3 fusion protein in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:543–553. doi: 10.1080/10428190701799035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feuring-Buske M, Frankel AE, Alexander RL, Gerhard B, Hogge DE. A diphtheria toxin-interleukin 3 fusion protein is cytotoxic to primitive acute myeloid leukemia progenitors but spares normal progenitors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1730–1736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yalcintepe L, Frankel AE, Hogge DE. Expression of interleukin-3 receptor subunits on defined subpopulations of acute myeloid leukemia blasts predicts the cytotoxicity of diphtheria toxin interleukin-3 fusion protein against malignant progenitors that engraft in immunodeficient mice. Blood. 2006;108:3530–3537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-013813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du X, Ho M, Pastan I. New immunotoxins targeting CD123, a stem cell antigen on acute myeloid leukemia cells. J Immunother. 2007;30:607–613. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318053ed8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colmone A, Amorim M, Pontier AL, Wang S, Jablonski E, Sipkins DA. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science. 2008;322:1861–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.1164390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishikawa F, Yoshida S, Saito Y, et al. Chemotherapy-resistant human AML stem cells home to and engraft within the bone-marrow endosteal region. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1315–1321. doi: 10.1038/nbt1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellamy WT, Richter L, Sirjani D, et al. Vascular endothelial cell growth factor is an autocrine promoter of abnormal localized immature myeloid precursors and leukemia progenitor formation in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2001;97:1427–1434. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dias S, Hattori K, Zhu Z, et al. Autocrine stimulation of VEGFR-2 activates human leukemic cell growth and migration. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:511–521. doi: 10.1172/JCI8978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tavor S, Petit I, Porozov S, et al. CXCR4 regulates migration and development of human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells in transplanted NOD/SCID mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2817–2824. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsunaga T, Takemoto N, Sato T, et al. Interaction between leukemic-cell VLA-4 and stromal fibronectin is a decisive factor for minimal residual disease of acute myelogenous leukemia. Nat Med. 2003;9:1158–1165. doi: 10.1038/nm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spoo AC, Lubbert M, Wierda WG, Burger JA. CXCR4 is a prognostic marker in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:786–791. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liesveld JL, Rosell KE, Lu C, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia--microenvironment interactions: role of endothelial cells and proteasome inhibition. Hematology. 2005;10:483–494. doi: 10.1080/10245330500233452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng Z, Shi YX, Samudio IJ, et al. Targeting the leukemia microenvironment by CXCR4 inhibition overcomes resistance to kinase inhibitors and chemotherapy in AML. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Legras S, Gunthert U, Stauder R, et al. A strong expression of CD44-6v correlates with shorter survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1998;91:3401–3413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zon LI. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of haematopoietic stem-cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:306–313. doi: 10.1038/nature07038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owens BM, Hawley RG. HOX and non-HOX homeobox genes in leukemic hematopoiesis. Stem Cells. 2002;20:364–379. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-5-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frohling S, Scholl C, Bansal D, Huntly BJ. HOX gene regulation in acute myeloid leukemia: CDX marks the spot? Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2241–2245. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.18.4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scholl C, Bansal D, Dohner K, et al. The homeobox gene CDX2 is aberrantly expressed in most cases of acute myeloid leukemia and promotes leukemogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1037–1048. doi: 10.1172/JCI30182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon M, Grandage VL, Linch DC, Khwaja A. Constitutive activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway in acute myeloid leukaemia. Oncogene. 2005;24:2410–2420. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brandts CH, Sargin B, Rode M, et al. Constitutive activation of Akt by Flt3 internal tandem duplications is necessary for increased survival, proliferation, and myeloid transformation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9643–9650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barker N, Clevers H. Mining the Wnt pathway for cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:997–1014. doi: 10.1038/nrd2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao C, Chen A, Jamieson CH, et al. Hedgehog signalling is essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature07737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park IK, Qian D, Kiel M, et al. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:302–305. doi: 10.1038/nature01587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guzman ML, Neering SJ, Upchurch D, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB is constitutively activated in primitive human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 2001;98:2301–2307. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naugler WE, Karin M. NF-kappaB and cancer-identifying targets and mechanisms. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayo MW, Baldwin AS. The transcription factor NF-kappaB: control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1470:M55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(00)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jordan CT, Guzman ML. Mechanisms controlling pathogenesis and survival of leukemic stem cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:7178–7187. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guzman ML, Jordan CT. Considerations for targeting malignant stem cells in leukemia. Cancer Control. 2004;11:97–104. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guzman ML, Swiderski CF, Howard DS, et al. Preferential induction of apoptosis for primary human leukemic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16220–16225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252462599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guzman ML, Rossi RM, Karnischky L, et al. The sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide induces apoptosis of human acute myelogenous leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;105:4163–4169. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guzman ML, Rossi RM, Neelakantan S, et al. An orally bioavailable parthenolide analog selectively eradicates acute myelogenous leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;110:4427–4435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Birkenkamp KU, Geugien M, Schepers H, Westra J, Lemmink HH, Vellenga E. Constitutive NF-kappaB DNA-binding activity in AML is frequently mediated by a Ras/PI3-K/PKB-dependent pathway. Leukemia. 2004;18:103–112. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yilmaz OH, Valdez R, Theisen BK, et al. Pten dependence distinguishes haematopoietic stem cells from leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;441:475–482. doi: 10.1038/nature04703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J, Grindley JC, Yin T, et al. PTEN maintains haematopoietic stem cells and acts in lineage choice and leukaemia prevention. Nature. 2006;441:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature04747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Q, Simpson SE, Scialla TJ, Bagg A, Carroll M. Survival of acute myeloid leukemia cells requires PI3 kinase activation. Blood. 2003;102:972–980. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao S, Konopleva M, Cabreira-Hansen M, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dephosphorylates BAD and promotes apoptosis in myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 2004;18:267–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krause DS, Van Etten RA. Right on target: eradicating leukemic stem cells. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martelli AM, Nyakern M, Tabellini G, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and its therapeutical implications for human acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:911–928. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martelli AM, Tazzari PL, Evangelisti C, et al. Targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin module for acute myelogenous leukemia therapy: from bench to bedside. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2009–2023. doi: 10.2174/092986707781368423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tamburini J, Elie C, Bardet V, et al. Constitutive phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt activation represents a favorable prognostic factor in de novo acute myelogenous leukemia patients. Blood. 2007;110:1025–1028. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guzman ML, Li X, Corbett CA, et al. Rapid and selective death of leukemia stem and progenitor cells induced by the compound 4-benzyl, 2-methyl, 1,2,4-thiadiazolidine, 3,5 dione (TDZD-8) Blood. 2007;110:4436–4444. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hess CJ, Berkhof J, Denkers F, et al. Activated intrinsic apoptosis pathway is a key related prognostic parameter in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1209–1215. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cory S, Adams JM. Killing cancer cells by flipping the Bcl-2/Bax switch. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Konopleva M, Contractor R, Tsao T, et al. Mechanisms of apoptosis sensitivity and resistance to the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jordan CT. Can we finally target the leukemic stem cells? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2008;21:615–620. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jordan CT. The leukemic stem cell. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2007;20:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Misaghian N, Ligresti G, Steelman LS, et al. Targeting the leukemic stem cell: the Holy Grail of leukemia therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23:25–42. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheung AM, Wan TS, Leung JC, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity in leukemic blasts defines a subgroup of acute myeloid leukemia with adverse prognosis and superior NOD/SCID engrafting potential. Leukemia. 2007;21:1423–1430. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hess DA, Meyerrose TE, Wirthlin L, et al. Functional characterization of highly purified human hematopoietic repopulating cells isolated according to aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Blood. 2004;104:1648–1655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goodell MA, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, et al. Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Nat Med. 1997;3:1337–1345. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guzman ML, Upchurch D, Grimes B, et al. Expression of tumor-suppressor genes interferon regulatory factor 1 and death-associated protein kinase in primitive acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 2001;97:2177–2179. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Majeti R, Becker MW, Tian Q, et al. Dysregulated gene expression networks in human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3396–3401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900089106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kern W, Haferlach C, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. Monitoring of minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2008;112:4–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Rhenen A, Moshaver B, Kelder A, et al. Aberrant marker expression patterns on the CD34+CD38− stem cell compartment in acute myeloid leukemia allows to distinguish the malignant from the normal stem cell compartment both at diagnosis and in remission. Leukemia. 2007;21:1700–1707. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roboz GJ. Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in older patients. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:285–295. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Small D. Targeting FLT3 for the treatment of leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2008;45:S17–21. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lancet JE, Karp JE. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors in hematologic malignancies: new horizons in therapy. Blood. 2003;102:3880–3889. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Buchner T, Krug U, Berdel WE, et al. Maintenance for acute myeloid leukemia revisited. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2007;8:296–304. doi: 10.1007/s11864-007-0041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Black JH, McCubrey JA, Willingham MC, Ramage J, Hogge DE, Frankel AE. Diphtheria toxin-interleukin-3 fusion protein (DT(388)IL3) prolongs disease-free survival of leukemic immunocompromised mice. Leukemia. 2003;17:155–159. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fitter S, Dewar AL, Kostakis P, et al. Long-term imatinib therapy promotes bone formation in CML patients. Blood. 2008;111:2538–2547. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Levis M, Murphy KM, Pham R, et al. Internal tandem duplications of the FLT3 gene are present in leukemia stem cells. Blood. 2005;106:673–680. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xu Q, Thompson JE, Carroll M. mTOR regulates cell survival after etoposide treatment in primary AML cells. Blood. 2005;106:4261–4268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lauth M, Toftgard R. The Hedgehog pathway as a drug target in cancer therapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;8:457–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kobune M, Takimoto R, Murase K, et al. Drug resistance is dramatically restored by hedgehog inhibitors in CD34(+) leukemic cells. Cancer Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abrahamsson AE, Geron I, Gotlib J, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta missplicing contributes to leukemia stem cell generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3925–3929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900189106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]