Abstract

The present study was carried out to evaluate the renoprotective antioxidant effect of Spirulina platensis on gentamicin-induced acute tubular necrosis in rats. Albino-Wistar rats, (9male and 9 female), weighing approximately 250 g, were used for this study. Rats were randomly assigned to three equal groups. Control group received 0,9 % sodium chloride intraperitoneally for 7 days at the same volume as gentamicin group. Gentamicin group was treated intraperitoneally with gentamicin, 80mg/kg daily for 7 days. Gentamicin+spirulina group received Spirulina platensis 1000 mg/kg orally 2 days before and 7 days concurrently with gentamicin (80mg/kg i.p.). Nephrotoxicity was assessed by measuring plasma nitrite concentration, stabile metabolic product of nitric oxide with oxygen. Plasma nitrite concentration was determined by colorimetric method using Griess reaction. For histological analysis kidney specimens were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain. Plasma nitrite concentration and the level of kidney damage were significantly higher in gentamicin group in comparison both to the control and gentamicin+spirulina group. Spirulina platensis significantly lowered the plasma nitrite level and attenuated histomorphological changes related to renal injury caused by gentamicin. Thus, the results from present study suggest that Spirulina platensis has renoprotective potential in gentamicin-induced acute tubular necrosis possibly due to its antioxidant properties.

Keywords: Spirulina platensis, nitric oxide, gentamicin, acute tubular necrosis, antioxidant

INTRODUCTION

The aminoglycoside antibiotic (gentamicin) is very effective in treating gram-negative infections (1). Unfortunately, acute renal failure is major complication in 10-20% of patients receiving the drug (2). It has been demonstrated that gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity is characterized by direct tubular necrosis, which is localized mainly in proximal tubules (3). The exact mechanisms of gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity still remain unclear. Recent evidence showed that reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a pivotal role in gentamicinmediated nephrotoxicity. Walker et al. (2) have demonstrated that oxidative stress induced by gentamicin, is the central pathway responsible for renal injury. Some studies have reported that antioxidant administration ameliorates gentamicin-induced nephropathy (3).

Spirulina platensis is a type of fresh-water blue-green algae which grows naturally in warm climate countries and has been considered as supplement in human and animal food (4). The numerous toxicological studies have established its safety for human consumption (5). They have been found to be rich source of minerals, essential fatty and amino acids, vitamins - especially vitamin B12 and antioxidant pigments such as carotenoids (6). In addition, several studies showed that Spirulina species exhibit various biological activites such as anti-inflammatory (7), antitumor (8), hepatoprotective (9), radio protective (10), antimicrobial (11), strengthenining immune system (12, 13), metalloprotective (14) and antioxidant effects (15). The present study was designed to investigate the renoprotective potential of Spirulina platensis on gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and renal injury in rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments were carried out in adult Wistar rats (9 male and 9 female) weighing 250-300g, which were fed standard diet and water. The experimental protocols were approved by local Ethical Committee. Rats were randomly assigned to the three equal groups: control, gentamicin+spirulina and gentamicin group. Gentamicin was purchased, as 80mg/2ml injection. Spirulina platensis was obtained commercially such as a dark blue-green dry powder.) Control group (n=6) received for a seven days 0,9% NaCl intraperitoneally (i.p.) in equivalent volume as gentamicin treated rats. Gentamicin group (n=6) was injected with gentamicin at a dose of 80 mg/kg/day i.p. for 7 days. Gentamicin+spirulina group (n=6) received Spirulina platensis, dissolved in distilled water,1000mg/ kg p.o. two days before and seven days concomitantly with gentamicin at a dose of 80 mg/kg/day i.p. At the end of the study the animals were sacrificed under deep ether anaesthesia. A midline abdominal incision was performed and blood was collected from the abdominal aorta for the measurement of plasma nitric oxide level. Both kidneys were isolated and stored in 10% formalin for the histological studies.

NO measurement

The plasma level of nitric oxide was determined by measuring plasma nitrite concentrations, a stabile metabolic product of NO with oxygen. Conversion of nitrate (NO3) into nitrite (NOp was done with elementary zinc. Nitrite concentration in plasma was determined by Griess reaction (16). Absorbance was measured at 546 nm. The results were expressed as μmol/dm3.

Renal histology

The kidneys were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution and then embedded in paraffin wax. The sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and hematoxylin-eosin (H-E), and examined by light microscopy. Histological sections of the kidneys from all rats were qualitatively and quantitatively assessed. A semiquantitative evaluation of renal tissue was accomplished by scoring the degree of damage severity according to previously published criteria (17). The changes were limited to the tubulointerstitial areas and were graded as follows: 0=normal; 1=areas of focal granulovacuolar epithelial cell degeneration and granular debris in the tubular lumen with or without evidence of desquamation in small foci (less than 1% of total tubule population involved by desquamation); 2=obvious tubular epithelial necrosis and desquamation but involving less than half of cortical tubules; 3= necrosis and desquamation in more than half of the proximal tubules, but intact tubules easily identified; 4=complete or almost complete proximal tubular necrosis. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 12.0. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. The difference in values of tested parameters was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis test. Afterwards, MannWhitney test was used to test the significance of mean values differences between the two groups. Association between plasma level of NO and histological injury score was tested with Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. P<0,05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

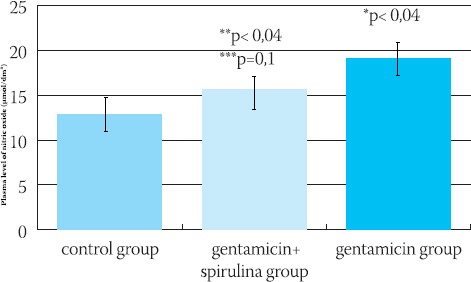

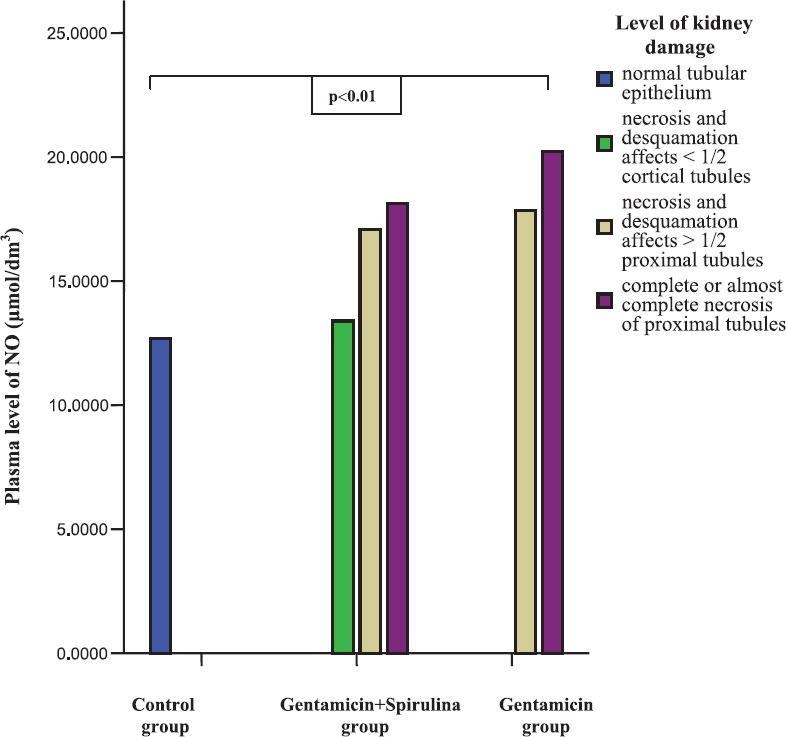

Plasma NO level was statistically significantly different between the groups (p<0,01). Using two-independent samples test, the significant difference (p< 0,004) was found between the control group (X=12,70±1,51 μσιοΕ dm3) and gentamicin group (X=19,03±0,69 μmol/ dm3), as well as between gentamicin+spirulina group (X=15,58±1,17 μσ^Μσ!3) and gentamicin group (p<0,04). No significant difference was found between control and gentamicin+spirulina group (p=0,1) (Figure 1.)

FIGURE 1.

Plasma level of nitric oxide (μπιοΙΛΙιη3) in control, gentamicin+spirulina and gentamicin group, mean ± SEM. *p< 0,004 gentamicin versus control, **p< 0,04 gentamicin+spirulina versus gentamicin, ***p=0,l gentamicin+spirulina versus control.

Renal histology

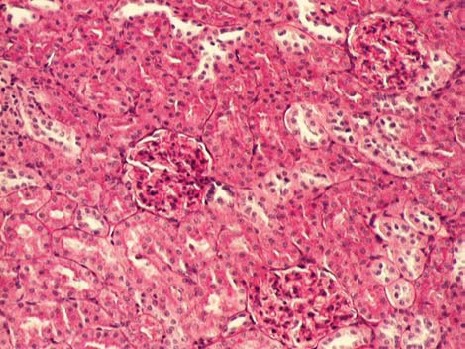

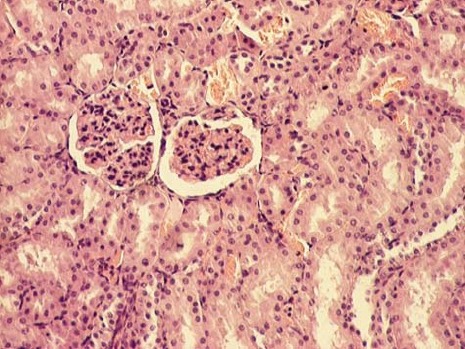

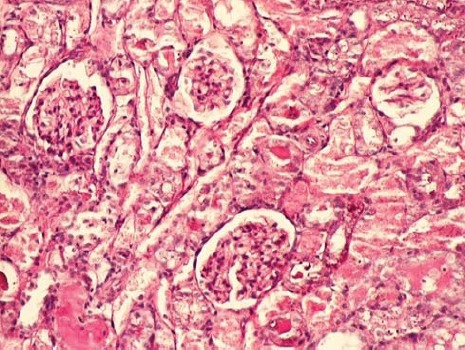

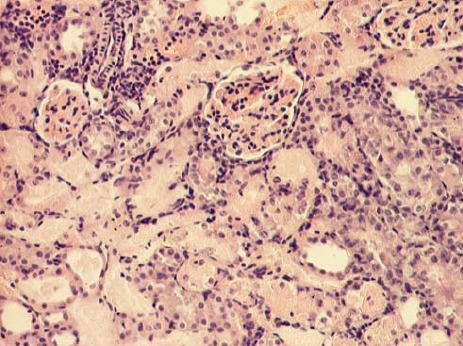

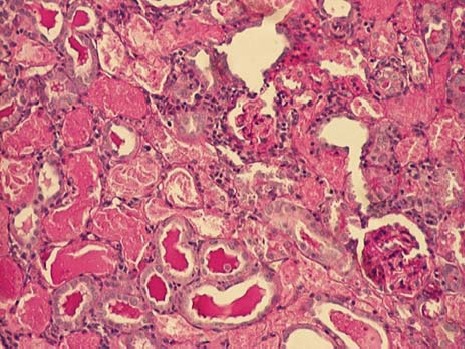

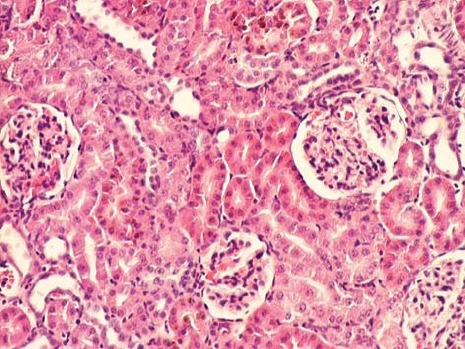

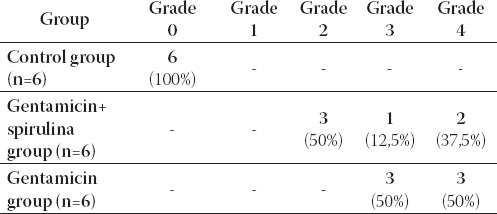

The kidney of control rats showed normal structure of renal parenchyma. Kidney specimens from this group showed the normal structure of proximal tubules with abundant brush border membranes. Glomeruli and distal tubules also showed normal structure (Figure 2A and 2B). By contrast, the kidney of rats treated with gentamicin alone showed severe and extensive histological changes. Cortical tubules revealed degeneration and necrosis of epithelial cells. In the proximal tubular lumen a significant quantity of desquamated epithelial cells debris was present. In some distal tubules amorphous PAS positive cylinders were noticed. Gentamicin also produced interstitial edema, tubular brush border loss and necrosis of epithelium (Figure 3A and 3B). Concomitant treatment of animals with Spirulina platensis and gentamicin significantly reduced these changes. In superficial kidney cortex of gentamicin+spirulina group, qualitative changes were observed especially in proximal tubules. These changes were characterized by narrow areas of degeneration, necrosis and desquamation of epithelial cells. These segments were circled with sections of distal tubules whose epithelium was relatively preserved. Epithelial cells of proximal tubules that belong to juxtamedullary nephrons showed significantly lesser degree of damage compared to those in superficial part of cortex. Damaged tubules were partly without epithelium, and partly epithelial cells preserved contact with basal membrane. Nuclei of these cells were to a certain extent dislocated and were present more apical, and they showed different degree of damage. Tubular lumen of damaged areas was narrowed, and moderately filled with cytoplasmic and nuclear debris. Basal membrane of tubules in the areas of complete degeneration and necrosis showed partly disintegration and because of that borders between tubules were not present. In the areas with lesser intensity of changes, basal membrane had preserved integrity. Epithelial cells of the loop of Henle, distal tubules and collecting duct had relatively preserved structure, but their lumen was to a certain degree militated and filled with amorphous PAS positive cylinders. In certain glomeruli accumulation of amorphous mesangian matrix was observed. Interstitium in the areas of damaged tubules revealed signs of edema and focal infiltration of mononuclear cells (Figure 4A and 4B). In the control group all specimens of kidney tissue had normal structure (grade 0). In the gentamicin group three samples of kidney tissue were graded as 3 and three were graded as 4. In the gentamicin+spirulina group two kidney samples were graded as 4, one was graded as 3 and three were graded as 2 (Table 1.). Numbers indicate the specimens having the same respective grading criteria in each group.

FIGURE 2A.

Renal cortex of control rats (PAS, 100x).

FIGURE 2B.

Renal cortex of control rats (HE, 100

FIGURE 3A.

Renal cortex of gentamicin treated rats (PAS, 100x).x)

FIGURE 3B.

Renal cortex of gentamicin treated rats (HE, 100x).

FIGURE 4A.

Renal cortex of gentamicin+spirulina treated rats (PAS, 100x).

FIGURE 4B.

Renal cortex of gentamicin+spirulina treated rats (HE, 100x).

TABLE 1.

Kidney histopathological injury score

Histopathological injury score:

0=normal

1=tubular epithelium necrosis and desquamation affects <1% of all tubules

2=tubular epithelium necrosis and desquamation affects <1/2 cortical tubules

3=tubular epithelium necrosis and desquamation affects >1/2 cortical tubules

4=complete or almost complete necrosis of proximal tubules

Using Spearman rank correlation analysis a positive, statistically significant, correlation was found between histopathological injury score and plasma NO level (r= 0,82; p<0,001) in all groups (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Mean plasma level of NO (|imol/dm3) and kidney histopathological injury score within control and experimental groups

DISCUSSION

For a more overall insight in pathophysiological mechanisms in the development of toxic tubular damage induced with gentamicin, as well as in new therapeutic approach, numerous studies were conducted in experimental model of acute tubular necrosis (ATN) (18, 19). Recent evidences have indicated that reactive oxigen species (ROS) are potential mediators involved in gentamicin-induced renal injury. ROS can alter the basic cellular constituents and their organelles. Such oxidant-induced alterations can profoundly affect cellular vitality. ROS impair enzymatic and structural protein molecules through such mechanisms as oxidation of sulfhydryl groups, carbonyl formation and deamination. They also may destabilize cytoskeletal proteins and integrins, which facilitate the attachment of cells to the neighboring extracellular matrix. Thus, oxidants have a capacity to attack and disable multiple critical cellular targets and thereby provoke cell death (20). Gentamicin has been shown to enhance generation of superoxide anions, peroxinitrite anions, and hydrogen peroxide from renal cortical mitochondria (21, 22).

An enhanced generation of nitric oxide as occurs by activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) can prove deleterious to the kidney through several mechanisms. Large amount of NO can lead to depletion of cellular ATP which can inactivate enzymes, such as the Krebs cycle enzyme and enzyme involved in mitochondrial electron transport (23). In our study, gentamicin administration produced marked increase in plasma nitrite level. Use of Spirulina platensis just before and concomitantly with gentamicin had significantly reduced plasma NO production. This effect may be due to inhibition of iNOS. In the same time Spirulina attenuated gentamicin-induced nitrosative stress and renal injury. Our results are in the accordance with the results of Kuhad et al. (24) who tested the renoprotective effects of Spirulina fusiformis on cisplatin-induced renal injury due to oxidative stress in rats. The plasma nitrite level had been used to assess the level of renal damage. Cisplatin caused marked renal oxidative and nitrosative stress, and significantly deranged renal function. Chronic Spirulina fusiformis treatment significantly reduced plasma nitrite level. In the other study same authors tested the protective effects of different doses of Spirulina (1500, 1000, 500mg/ kg, p.o.) in gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and renal dysfunction in rats (25). They found the highest plasma NO level in rats treated only with gentamicin. The level of plasma NO in rats treated with gentamicin and Spirulina was the lowest in animals that received the highest dose of Spirulina (1500mg/kg), and the highest level of plasma NO in animals that received the lowest dose of Spirulina (500mg/kg). Results of their study also suggest that increased production of NO is a consequence of increased activity of iNOS in the conditions of kidney damage caused by gentamicin. The results of our study showed marked nephrotoxicity of gentamicin in rats with characteristic morphological changes in kidneys such as tubular necrosis and degenerations, interstitial edema and infiltration of mononuclear cells. Spirulina platensis significantly attenuated these structural changes. Our results are in the accordance with those of Kuhad et al. (24, 25) who in both studies histologically confirmed protective effects of Spirulina platensis, whether it was cisplastin or gentamicin-induced ATN.

CONCLUSION

Our results clearly indicate renoprotective role of Spirulina platensis in acute tubular necrosis caused by gentamicin probably due to her antioxidative effects. This study also indicates the possible role of nitric oxide in renal damage caused by oxidative stress.

List of Abbreviations

NaCl - sodium chloride

H-E - hematoxylin-eosin

PAS - periodic acid-Schiff

ROS - reactive oxygen species

i.p. - intraperitoneally

p.o. - per orally

ATN - acute tubular necrosis

iNOS - inducible nitric oxide synthase

REFERENCES

- 1.Ho JL, Barza M. Role of aminoglycoside antibiotics in the treatment of intra-abdominal infection. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 1987;31(4):485–491. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker PD, Barri Y, Shah SV. Oxidant mechanisms in gentamicin nephrotoxicity. Ren. Fail. 1999;21(3-4):433–442. doi: 10.3109/08860229909085109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedraza-Chaverrí J, González-Orozco AE, Maldonado PD, et al. Diallyl disulfide ameliorates gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and nephropathy in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;473(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz Flores LE, Madrigal-Bujaidar E, Salazar M, Chamorro G. Anticlastogenic effect of Spirulina maxima extract on the micronuclei induced by maleic hydrazide in Tradescantia. Life. Sci. 2003;72(12):1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirahashi T, Matsumoto M, Hazeki K, Saeki Y, Ui M, Seya T. Activation of the human innate immune system by Spirulina: augmentation of interferon production and NK cytotoxicity by oral administration of hot water extract of Spirulina platensis Int. Immunopharmacol. 2002;2(4):423–434. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belay A. The potential application of Spirulina (Arthrospora) as a nutritional and therapeutic supplement in health management. JANA. 2002;5:27–48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddya CM, Bhatb VB, Kiranmaia G, Reddya MN, et al. Selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 by C-Phycocyanin, a Biliprotein from Spirulina platensis Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;277:599–603. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittal A, Suresh KP, Banerjee S, Rao AR, Kumar A. Modulatory potential of Spirulina fusiformis on carcinogen metabolizing enzymes in swiss albino mice. Phytother. Res. 1999;13:111–114. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199903)13:2<111::AID-PTR386>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma MK, Sharma A, Kumar A, Kumar M. Spirulina fusiformis provides protection against mercuric chloride induced oxidative stress in Swiss albino mice. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 2007;45(12):2412–2419. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S. Ph.D. Thesis. Jaipur, India: University of Rajasthan; 2000. Chemical modification of radiation response in Swiss albino mice. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma MK, Patni R, Kumar M, Kumar A. Modification of mercury-induced biochemical alterations in blood of Swiss albino mice by Spirulina fusiformis Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2005;20(2):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qureshi MA, Kidd MT, Ali RA. Spirulina platensis extract enhances chicken macrophage functions after in vitro exposure J. Nutritional. Immunol. 1995;3(4):35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qureshi MA, Garlich JD, Kidd MT. Dietary Spirulina platensis enhances humoral and cell-mediated immune functions in chickens. Immunophar. Immunotox. 1996;18(3):465–476. doi: 10.3109/08923979609052748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shastri D. Ph.D. Thesis. Jaipur, India: University of Rajasthan; 1999. Modulation of heavy metal induced toxicity in the testes of Swiss albino mice by certain plant extracts. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upasani CD, Balaraman R. Protective effect of Spirulina on lead induced deleterious changes in the lipid peroxidation and endogenous antioxidants in rats. Phytother. Res. 2003;17:330–334. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogovski J, et al. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite and [15N] nitrate in biological fluids. Anal. Biochem. 1982;126:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houghton DC, Plamp CE, DeFehr JM, et al. Gentamicin and tobramycin nephrotoxicity: a morphologic and functional comparison in the rat. Am. J. Pathol. 1978;93:137–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopple JD, Ding H, Letoha A, et al. L-carnitine ameliorates gentamicin-induced renal injury in rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002;17:2122–2131. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.12.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avdagić N, Nakaš-Ićindić E, Rašić S, Hadžović-Džuvo A, Zaćiragić A, Valjevac A. The effects of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-N6-(1-iminoethyl) lysine in gentamicn-induced acute tubular necrosis in rats. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2007;7(4):322–327. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2007.3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Free radicals and antioxidant protection: mechanisms and significance in toxicology and disease. Hum. Toxicol. 1988;7:7–13. doi: 10.1177/096032718800700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker PD, Shash SV. Gentamicin enhanced production of hydrogen peroxide by renal cortical mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253:C495–499. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.4.C495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Dugo L, et al. A role for superoxide in gentamicin-mediated nephropathy in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;450:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katusic ZS. Superoxide anion and endothelial regulation of arterial tone. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;20(3):443–448. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhad A, Tirkey N, Pilkhwal S, Chopra K. Renoprotective effect of Spirulina fusiformis on cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and renal dysfunction in rats. Ren. Fail. 2006;28(3):247–254. doi: 10.1080/08860220600580399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhad A, Tirkey N, Pilkhwal S, Chopra K. Effects of Spirulina, a blue green algae, on gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and renal dysfunction in rats. Fund. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006;20:121–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]