Abstract

BACKGROUND

The increased prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents is associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular diseases. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) efficiently explains the ability of perceived behavioral control and possibly attitude to enhance the motivations of the obese people to lose weight. Our aim was to investigate the effect of TPB-based education on weight loss in obese and overweight adolescents.

METHODS

In an interventional study, simple random sampling was used to select 86 overweight and obese adolescents aged 13-18 years in the pediatric clinic at the Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute. Anthropometric measures and TPB constructs were collected using a researcher-made questionnaire. The questionnaires were filled out before and six weeks after the intervention. Participants received 5 sessions of training based on the constructs of the TPB.

RESULTS

A significant increase was observed in the mean score for knowledge and TPB constructs (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intention, and behavior) six weeks after the educational intervention (P < 0.001). Moreover, significant decrease in body mass index (P < 0.001), weight (P = 0.001), and waist circumference (P < 0.001) of adolescents were found after the educational intervention.

CONCLUSION

The TPB-based interventions seem to be effective in losing weight in obese and overweight adolescents. This theory serves as a helpful theoretical framework for health-related behaviors and can be an appropriate pattern to plan for educational interventions.

Keywords: Adolescents, Education, Obesity, Behavior

Introduction

Currently, the prevalence of overweight and obesity are increasing worldwide. Over 1.12 billion people worldwide are projected to be overweight and obese up to 2030.1 Overweight and obesity prevalence is increasing not only among adults but also especially in children and adolescents. These two conditions are known as the most common eating disorders among children and adolescents in the USA.2

Overweight and obesity prevalence has markedly increased in the recent decades in Iran due to changes in lifestyle and inappropriate eating behaviors. On average, 5.0%-13.5% of children and 3.2%-11.9% of adolescents under 18 years in Iran have been reported to be overweight and obese.3 Increase in prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents is associated with early maturation, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, and some types of cancer.4 Besides that, overweight and obesity are associated with certain cognitive and social problems that can affect children's and adolescents' psychosocial health including discrimination, low self-esteem, depression, dissatisfaction with body image, exposure to negative labels, and social exclusion in addition to adverse effects on physical health.5

In addition to inappropriate eating habits, physical inactivity or decline in physical activity are considered as predisposing factors for overweight and obesity in children and adolescents.6

Epidemiological and clinical studies have confirmed the role of low-calorie diet, intensified physical activity, and cognitive strategies to change behaviors.7 These strategies include self-monitoring, problem-solving, planning, stress management, and gaining other children's social supports in managing adolescents obesity and associated cardio-metabolic risks. Findings, however, are not always consistent.8

Human behaviors are physical actions and observable emotions. Health education is required to recognize behavior and, if necessary, replace it with new behavior to develop effective programs.9 This determines the role of models and theories in behavioral sciences in health education.10

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is one of the known patterns of behavior change. According to the TPB, intention is the most important determinant of behavior. Intention itself is influenced by three independent constructs, i.e. attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (PBC).11 Attitude represents a positive or negative evaluation of behavior, subjective norms refer to perceived social pressure to do or not to do a particular behavior and PBC is the perceived ease or difficulty of a particular behavior that directly or indirectly affects the behavior. This theory states that people decide to exhibit a behavior when they evaluate it to be positive and believe that there are influencing and important people who think that they should perform that behavior, and perceive that they have control over doing that behavior.12

To develop a behavior based on theoretical principles, it is necessary to identify the most effective constructs on development of that behavior, and their direct and indirect effects so that more effective educational interventions can be developed and planned.13

Although the TPB has been frequently used in studies to predict exercise and healthy eating habits, a few number of such studies have considered weight-reduction behavior. In addition, most studies that have focused on populations other than obese women would supplement the applicability of the TPB to weight reduction.14 The TPB has been demonstrated to be a helpful theoretical framework for many health-related behaviors. The determinants offer strong correlations to predict desirable behaviors.14 Because the obesity that remains since childhood and adolescents can increase the risk of developing metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases in youth and adulthood, it is essential to promote effective educational programs for weight loss in adolescents. Thus, our aim was to investigate the effect of TPB-based education on weight loss in obese and overweight adolescents.

Materials and Methods

This interventional study was conducted at the Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute, Isfahan, Iran, from July to September 2016. The probability of making type I error and the power of the hypothesis test was considered 0.05 and 0.9%, respectively. The standard deviation difference was 6 according to Muzaffar et al. study15 and total sample size was estimated to be 86. After obtaining ethical clearance (ethical code number IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1394.74), total of 100 adolescents and their parents were invited to a meeting in Cardiovascular Research Centre through convenience sampling based on their records in the Pediatric Clinic. After receiving explanations about the study, they provided written informed consent to participate. The inclusion criteria were being 13-18 years old, volunteering to participate in the study and having body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 according to age and gender.

The exclusion criteria were suffering from diseases such as hypothyroidism and Cushing's syndrome, having the history of taking drugs, BMI ≥ 25 for athletes, and refusing to participate in the study.

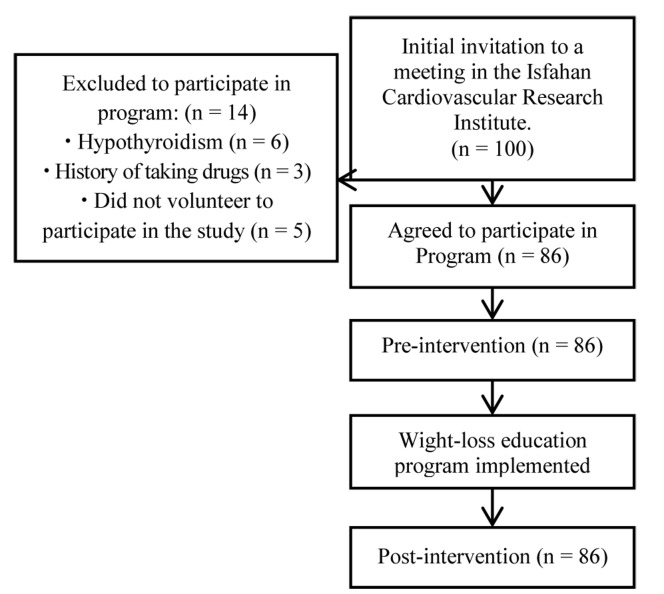

After selecting 86 adolescents, the pretest questionnaires were distributed. All of the cases consented to cooperate with the study. Figure 1 presents the flowchart of study participants.

Figure 1.

The study flowchart

After the data were collected, the TPB-based intervention for the adolescents and their parents included five 60-min educational sessions of speech, group discussion, role playing, questions and answers and pamphlets, booklet, photographs, movie screening, and PowerPoint displays. the man topics covered in the training sessions are as follows:

Increasing knowledge of adolescent’s about obesity and its signs, risk factors, symptoms, complication

Development of positive attitudes and correction of false beliefs

Talking about the role of nutrition in preventing overweight and obesity, and the importance of exercise in weight loss

Strengthening social supports through holding the sessions with the presence of at least one of the parents and explaining the role of family members, friends, and teachers in weight loss

Strengthening self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is influenced by four main information sources including experience, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and physiological and affective states that can be integrated either alone or in combination into a rehabilitation program.16,17 In the session where vicarious experience was discussed to improve self-efficacy, a number of successful adolescents in weight loss were invited who participated in previous Pediatric Clinic programs. Furthermore, for strengthening self-efficacy in other sessions, three sources of self-efficacy including experience, verbal persuasion and physiological and affective states were used. We asked adolescents at the end of each session to watch the photographs and a short movie in the classroom. The adolescents were also recommended to enlist their goals in losing weight after watching the photographs and short movie. The photographs were about patients that suffered from overweight and obesity and the short movie showed that people could overcome any difficulty. Verbal persuasion was conducted in two ways: verbal encouragement by the researcher during education intervention, and telephone follow-ups throughout the study. This part of the intervention continued on a weekly basis for 6 weeks after education intervention. Topics from the previous sessions were reviewed and the subjects were offered educational booklet. Summative evaluation was conducted six weeks after completing the educational intervention using the same self-report questionnaires administered in the pretest.

Anthropometric parameters including weight, height, and waist circumference were measured twice using standard tools, before and six weeks after the educational intervention. Height and weight were measured with minimal clothing and without shoes. Height was recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm. Weight was also measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a balance (Seca) scale. The waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the iliac crest at the completion of exhalation. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height in squared meter. Based on the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) definition, BMI was classified into three categories of normal (BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m).18

We designed questionnaire according to a study guideline,19 and scientific resources and then elicited the expert comments including the professors of health education, nutrition and exercise physiologist to develop the items.

The questionnaire was developed based on the TPB (Table 1).

Table 1.

Some illustrative items of the Questionnaire

| TPB constructs | Questions | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Which of the following diseases is created with overweight and obesity? | True /False |

| Attitudes | Weight loss decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease, for me. Prevention of cardiovascular disease … | Absolutely agree to Absolutely disagree It is very important to It is not very important |

| Subjective norms | My parents regularly encourage me for weight loss. What is the opinion of parent’s importance for my weight loss? | Absolutely agree to Absolutely disagree Much frequently to Never |

| PBC | The use of low-caloric diet for weight loss is difficult for me. | Absolutely agree to Absolutely disagree |

| Intention | I intend to get regular physical activity in free time for weight loss. | Absolutely agree to Absolutely disagree |

| Behavior | Do you have fruits and vegetables 2 or 3 time each day? | Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Frequently, Always |

TPB: The theory of planned behavior

PBC: Perceived behavioral control

The questionnaire consisted of seven sections: demographic items, questions for knowledge measurement (10 items, α = 0.88, true/false scale), and items on five TPB constructs i.e. attitude (20 items, α = 0.68, 5-point Likert scale), subjective norms (12 items, α = 0.79, 5-point Likert scale), PBC (10 items, α = 0.78, 5-point Likert scale), intention (7 items, α = 0.74, 5-point Likert scale), behavior [10 items, α = 0.67, 5-point Likert scale).

To determine the content validity, 10 specialists and professionals outside the team were consulted in the field of health education and health promotion (n = 8) and nutrition (n = 2). To investigate the reliability, a list of the items was completed by 35 adolescents aged 13-18 years with similar characteristics to target population in two successive 14-day periods. The total reliability of the instrument was 0.75 based on the Cronbach's alpha. Because the alpha values for the questionnaire used in this study were over 0.7, the instrument was considered reliable.20

Data were analyzed by SPSS software (version 20.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data were expressed as mean standard deviation and qualitative as frequencies and percentages. The impact of the intervention on anthropometric indexes and constructs of TPB including knowledge, attitude, subjective norms, PBC, intention and behavior was assessed by paired t-test procedures. To investigate the normal distribution of the data, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used. P < 0.050 was considered significant.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 15.37 ± 1.54 years. At baseline, the mean BMI of the adolescents was 29.89 ± 4.38 kg/m2, mean weight 82.46 ± 16.22 kg, and mean waist circumference 97.39 ± 10.87 cm. Table 2 shows the demographic data.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age years | |

| 13 | 17 (19.8) |

| 14 | 7 (8.1) |

| 15 | 18 (20.9) |

| 16 | 20 (23.3) |

| 17 | 19 (21.1) |

| 18 | 5 (5.8) |

| Sex/gender | |

| Girl | 51 (59.3) |

| Boy | 35 (40.7) |

| Educational level | |

| Grade 6-9 high school | 25 (29.1) |

| Grade 9-12 high school | 61 (70.9) |

| Maternal education | |

| Illiterate | 0 |

| Primary | 7 (8.1) |

| Secondary | 13 (15.1) |

| High school | 46 (53.5) |

| College | 20 (24.1) |

| Father education | |

| Illiterate | 0 |

| Primary | 10 (11.6) |

| Secondary | 25 (29.6) |

| High school | 30 (34.8) |

| College | 21 (24.0) |

| Mother’s occupation | |

| Employed | 13 (15.1) |

| Housewife | 73 (84.9) |

| Father’s occupation | |

| Self-employed | 54 (62.8) |

| Worker | 6 (7.0) |

| Employed | 13 (15.1) |

| Retired | 13 (15.1) |

| Number of family members | |

| Three | 12 (14.0) |

| Four | 52 (60.5) |

| Five | 22 (23.3) |

| Monthly Family Income | |

| Less than RLs6,000,000 ($194) | 0 |

| RLs6,000,000- RLs10,000,000 ($194 to $323) | 42 (48.8) |

| RLs10,000,000- RLs20,000,000 ($323 to $645) | 31 (36.0) |

| More than RLs20,000,000 ($645) | 13 (15.1) |

In adolescents, six weeks after the educational intervention, the mean scores for knowledge and the TPB constructs increased significantly (P < 0.001, Table 3). Besides that, after the educational intervention, the mean value of weight (P = 0.001), BMI and waist circumference (P < 0.001) of the adolescents decreased significantly (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison between the mean scores of adolescents’ knowledge and the theory of planned behavior components

| Variable | Before the intervention (n = 86) |

6 weeks after the intervention (n = 86) |

Mean difference (n = 86) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Knowledge | 21.43 ± 7.09 | 34.50 ± 2.12 | 13.06 ± 7.17 | < 0.001 |

| Attitude | 84.18 ± 5.96 | 90.47 ± 4.34 | 6.29 ± 6.71 | < 0.001 |

| Subjective norms | 47.48 ± 5.55 | 51.27 ± 4.87 | 3.79 ± 5.74 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived behavioral control | 31.44 ± 7.35 | 42.16 ± 4.45 | 10.72 ± 6.99 | < 0.001 |

| Intention | 28.66 ± 3.89 | 30.75 ± 3.83 | 2.93 ± 5.08 | < 0.001 |

| Behavior | 20.88 ± 6.73 | 29.54 ± 4.98 | 8.66 ± 6.73 | < 0.001 |

Comparison between before and 6 weeks after the intervention, paired t-test

SD: Standard deviation

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviation of anthropometric indices in the adolescents’ at the baseline and 6 weeks after the intervention

| Variable | Before the intervention (n = 86) |

6 weeks after the intervention (n = 86) |

Mean difference (n = 86) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.89 ± 4.38 | 29.42 ± 4.23 | -0.46 ± 0.78 | < 0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.46 ± 16.22 | 81.73 ± 15.84 | -0.73 ± 1.96 | 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 97.39 ± 10.87 | 95.43 ± 10.52 | -1.96 ± 2.92 | < 0.001 |

Comparison before and 6 weeks after the intervention, paired t-test

SD: Standard deviation

Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the effect of a TPB-based educational intervention on weight loss in overweight and obese adolescents in the Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute. Although the TPB has been heavily applied in studies that predict exercise and healthy eating habits, few of these studies have addressed the weight reduction behavior. Furthermore, few of the studies investigated change in body weight as a real behavioral outcome.14

This study revealed the knowledge, attitude, social norms and PBC might affect intentions of overweight and obese adolescents to control their weight through educational intervention. We observed an increase in the adolescents' mean score for knowledge six weeks after the completion of the intervention.

This is consistent with the results of Hazavehei et al.,21 Moradi et al.,22 and Alizadeh et al.23 The increase in knowledge and other constructs may represent the participants’ access to information as well as their participation in the course held by the researcher about obesity and health issues for the adolescents and their parents.

There was a significant difference between attitudes of adolescents 6 weeks after educational intervention. More clearly, after the intervention, most adolescents believed they were at risk of obesity. Schifter and Ajzen reported a poor correlation between attitude and final body-weight changes,24 whereas Palmeira et al. found that attitude was associated with body-weight reduction.25 The high variance among individuals could explain these inconsistent findings. Development of a desirable attitude to promote the practicing of target behavior is one of the strategies that have been much frequently emphasized in the education about obesity prevention and control.26 Therefore, educational interventions are expected to create an environment in which people can logically evaluate the consequences of practicing the current behavior and the positive outcomes of accomplishing the recommended behavior.

Subjective norms refer to an individual’s perception about a particular behavior which is influenced by the judgment of others, including parents, sibling, friends, and teachers.27 The mean score for subjective norms showed so increase after the intervention. This is in agreement with the results of McConnon et al.,28 and Kothe et al.29 However, Schifter and Ajzen,24 and Ahmadi Tabatabaei et al.,30 studies indicated no significant difference in the mean difference of subjective norms scores before and after the training. In the present research, the high score of subjective norms in the participant before the intervention implied that parents, relatives, doctors, health workers, friends and teachers had a high expectation of the population under study for weight reduction, with parents having the greatest share. Other measures taken in this study were holding training sessions attended by the parents, especially mothers, and preparing the pamphlets and booklets to strengthen the subjective norms of people influencing the participants, including the fathers and other family members.

The mean score on PBC in the present study showed that before the intervention, adolescents had low ability to control overweight and obesity. After the intervention, the mean score on PBC increased significantly. This is consistent with the results of Caron et al.,31 Karimy et al.32 and Pakpour Hajiagha et al.12 In contrast, in the study by Ahmadi Tabatabaei et al., no significant difference was observed in the mean difference of scores of perceived behavioral control before and after the intervention.30 The PBC of TPB addresses volitional control. However, there are controversies with the distinction between self-efficacy and PBC.14 Self-efficacy is considered as an important predictor of behavior. People with high levels of self-efficacy remove obstacles ahead through improving self-management skills and perseverance, stand in the face of difficulties, and have more control over issues.13,16

Self-efficacy and perceived barriers are common variables in several theoretical frameworks concerned with health behaviors.14 Therefore, certain opportunities to promote self-efficacy should be taken into account in designing the educational programs.

The mediator of behavior is intention, which is the perceived likelihood that an action is performed to achieve a targeted behavior; more clearly, no behavior occurs without intention.11 High levels of intention can have optimal effects in increasing the behavior.8 In the current study, the mean score on behavioral intention increased significantly. As a general rule, the more optimal attitude, subjective norms, and PBC are, the stronger an individual’s intentions for adopting a behavior will be.12 The results of the studies performed by Luszczynska et al.,8 Giles et al.,33 and Kothe et al.29 are in agreement with the findings of the present study.

We found a significant difference between the mean score of weight loss behavior before and after the intervention. This shows the positive effects of the education on adolescent’s behavior. Gardner et al.,34 and Chung and Fong14 demonstrated that behaviors for losing weight increased among women with obesity after the interventions. This is in agreement with the results of our study.

TPB-based educational programs, throughout six-week follow-up, were effective in reducing BMI, weight, and waist circumference in adolescents with overweight and obesity in our study, which is in agreement with the results of the studies by Pasdar et al.,35 Duangchan et al.,36 and Kazemi and Mazloom.37

The authors believe that although the mean BMI and weight of the adolescents decreased in the present study, it should be mentioned that BMI and weight changed slightly due to the adolescents' negligible height growth within the short duration of the educational intervention to the post-test. Because BMI normally increases with aging, maintaining BMI and even, in most cases, slight changes in this variable can be considered an achievement.38

It has been shown that theories that include self-efficacy such as transtheoretical model17 and social cognitive theory25 are the most predictive models for behavior change.

These findings also raise the question of whether the TPB can be used in designing and developing intervention methods for weight reduction programs. This study showed that the TPB can be effectively used in weight reduction programs targeting obese adolescents.

Strengths and limitations: There were a number of strengths to this study. First, this study has an explicit theoretical basis: the TPB was used in the current study as a theoretical framework to design, implement, and evaluate an intervention. Second, this study has been the first to utilize the TPB to develop and evaluate an intervention specifically designed for weight loss in adolescents with overweight and obesity in the Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute.

There were also a number of limitations to the present study. The outcomes were evaluated only 6 weeks after the educational intervention. Thus, future studies with longer follow-up periods are recommended for better evaluation. In addition, the final evaluation in this study was based on the adolescents’ self-reports, which could be a source of bias. Hence, future studies can use a combination of self-reports, direct observation of the behavior, and parents report.

Conclusion

The TPB-based interventions were effective in losing weight in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Additionally, all the TPB constructs played a key role in weight loss in adolescents. The TPB efficiently explains the ability of PBC and possibly the attitude to increase the intention of obese adolescents to obtain superior weight loss results.

Implications: This theory can serve as a helpful theoretical framework for health-related behaviors and also it can be an appropriate pattern to plan for educational interventions. Health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors are learned during childhood and adolescence. Receiving education based on models whose efficiency has already been confirmed, such as TPB, in the early years of life and repeating it in adolescents contribute greatly to the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases as well as reduction in risk factors for health. Due to the appropriate educational field and cost-effective educational intervention at school, the generalization of such training programs in other areas seems critical.

Acknowledgments

This article was derived from part of a thesis of the Master of Science degree at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran and is an interscholastic research project between this university (research project code 4467) and the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (research project code 294201). Hereby, the authors gratefully thank the honorable staff of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, the Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute, and the adolescents and their parents for sincere cooperation with this study, as well as the Research and Technology Deputy of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences for funding this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rezapour B, Mostafavi F, Khalkhali H. "Theory based health education: Application of health belief model for Iranian obese and overweight students about physical activity" in Urmia, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:115. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.191879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jafari-Adli S, Jouyandeh Z, Qorbani M, Soroush A, Larijani B, Hasani-Ranjbar S. Prevalence of obesity and overweight in adults and children in Iran; A systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s40200-014-0121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniels SR. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):47–67. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhoades DR, Kridli SA, Penprase B. Understanding overweight adolescents' beliefs using the theory of planned behaviour. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(6):562–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirschler V, Buzzano K, Erviti A, Ismael N, Silva S, Dalamon R. Overweight and lifestyle behaviors of low socioeconomic elementary school children in Buenos Aires. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong AP, Chan RS, Nelson EA, Chan JC. Role of low-glycemic index diet in management of childhood obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12(7):492–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luszczynska A, Sobczyk A, Abraham C. Planning to lose weight: Randomized controlled trial of an implementation intention prompt to enhance weight reduction among overweight and obese women. Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):507–12. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.di Elena Algarotti AC, Tosolin G. Behavior-Based Safety: Coniugare produttività e sicurezza comportamentale. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2010;32(Suppl 1):94–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vafaeenajar A, Masihabadi M, Moshki M, Ebrahimipour H, Tehrani H, Esmaily H. Determining the theory of planned behavior's predictive power on adolescents' dependence on computer games. Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2014;2(4):303–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26(9):1113–27. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pakpour Hajiagha A, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Mohammadi Zeidi B. The impact of health education based on theory of planned behavior on the prevention of aids among adolescents. Iran J Nurs. 2012;25(78):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo JL, Wang TF, Liao JY, Huang CM. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior in predicting breastfeeding: Meta-analysis and structural equation modeling. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung LM, Fong SS. Predicting actual weight loss: A review of the determinants according to the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol Open. 2015;2(1):2055102914567972. doi: 10.1177/2055102914567972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muzaffar H, Chapman-Novakofski K, Castelli DM, Scherer JA. The HOT (Healthy Outcome for Teens) project. Using a web-based medium to influence attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control and intention for obesity and type 2 diabetes prevention. Appetite. 2014;72:82–9. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajati F, Sadeghi M, Feizi A, Sharifirad G, Hasandokht T, Mostafavi F. Self-efficacy strategies to improve exercise in patients with heart failure: A systematic review. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014;10(6):319–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajati F, Mostafavi F, Sharifirad G, Sadeghi M, Tavakol K, Feizi A, et al. A theory-based exercise intervention in patients with heart failure: A protocol for randomized, controlled trial. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(8):659–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(4):284–94. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pi-Sunyer FX, Becker DM, Bouchard C, Carleton RA, Colditz GA, Dietz WH, et al. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: Executive summary. J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(4):899–917. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henson RK. Understanding internal consistency reliability estimates: A conceptual primer on coefficient alpha. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2001;34(3):177–89. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazavehei SM, Taghdisi MH, Saidi M. Application of the health belief model for osteoporosis prevention among middle school girl students, Garmsar, Iran. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2007;20(1):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moradi F, Shariat F, Mirzaeian K. Identifying the effects of training of obesity prevention and weight management and the knowledge of clients to neighborhood health house in the city of Tehran. Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2013;1(1):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alizadeh SH, Keshavarz M, Jafari A, Ramezani H, Sayadi A. Effects of nutritional education on knowledge and behaviors of Primary Students in Torbat-e- Heydariyeh. Journal of Health Chimes. 2013;1(1):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schifter DE, Ajzen I. Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;49(3):843–51. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.49.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmeira AL, Teixeira PJ, Branco TL, Martins SS, Minderico CS, Barata JT, et al. Predicting short-term weight loss using four leading health behavior change theories. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zizzi SJ, Lima Fogaca J, Sheehy T, Welsh M, Abildso C. Changes in Weight Loss, Health Behaviors, and Intentions among 400 Participants Who Dropped out from an Insurance-Sponsored, Community-Based Weight Management Program. J Obes. 2016;2016:7562890. doi: 10.1155/2016/7562890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton K, Daniels L, White KM, Murray N, Walsh A. Predicting mothers' decisions to introduce complementary feeding at 6 months. An investigation using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2011;56(3):674–81. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McConnon A, Raats M, Astrup A, Bajzova M, Handjieva-Darlenska T, Lindroos AK, et al. Application of the theory of planned behaviour to weight control in an overweight cohort. Results from a pan-European dietary intervention trial (DiOGenes). Appetite. 2012;58(1):313–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kothe EJ, Mullan BA, Butow P. Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption. Testing an intervention based on the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2012;58(3):997–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmadi Tabatabaei SV, Taghdisi MH, Nakheei N, Balali F. effect of educational intervention based on the theory of planned behaviour on the physical activities of Kerman health center s staff (2008). J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2017;12(2):62–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caron F, Godin G, Otis J, Lambert LD. Evaluation of a theoretically based AIDS/STD peer education program on postponing sexual intercourse and on condom use among adolescents attending high school. Health Educ Res. 2004;19(2):185–97. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karimy T, Saffari M, Sanaeinasab H, Khalagi K, Hassan Abadi M. Impact of educational intervention based on theory of planned behavior on lifestyle change of patients with myocardial infarction. Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2016;3(4):370–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giles M, McClenahan C, Armour C, Millar S, Rae G, Mallett J, et al. Evaluation of a theory of planned behaviour-based breastfeeding intervention in Northern Irish schools using a randomized cluster design. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19(1):16–35. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardner RE, Hausenblas HA. Exercise and diet determinants of overweight women participating in an exercise and diet program: A prospective examination of the theory of planned behavior. Women Health. 2005;42(4):37–62. doi: 10.1300/j013v42n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasdar Y, Moridi S, Najafi F, Niazi P, Heidary M. The effect of nutritional intervention and physical activities on weight reduction. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2011;15(6):427–34. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duangchan P, Yoelao D, Macaskill A, Intarakamhang U, Suprasonsin C. Interventions for healthy eating and physical activity among obese elementary schoolchildren: Observing changes of the combined effects of behavioral models. Int J Behav Med. 2010;5(1):46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazemi F, Mazloom Z. Comparison of the effects of two diets (low-glycemic index and low-fat) on weight loss, body mass index, glucose and insulin levels in the obese women. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2009;16(1):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemet D, Barkan S, Epstein Y, Friedland O, Kowen G, Eliakim A. Short-and long-term beneficial effects of a combined dietary-behavioral-physical activity intervention for the treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):e443–e449. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]