Abstract

Background and study aim

Gallbladder drainage in patients with cholecystitis who are unsuitable for surgery may be performed by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided placement of specifically designed fully covered metal stents. We describe the first case series of patients treated with a silicone-covered nitinol stent with bilateral anchor flanges.

Patients and methods

Data from consecutive patients with acute cholecystitis who were deemed unsuitable candidates for surgery were collected. The stent placement procedure was performed in two tertiary endoscopy centers by four experienced endoscopists. Technical and clinical success rates, as well as adverse events and clinical outcome at follow-up, were assessed.

Results

EUS-guided drainage for cholecystitis was performed in 16 patients (mean age 84 years; nine males). Technical and clinical success rates were 100 % (16/16) and 94 % (15/16), respectively; an early failure due to stone impaction occurred in the remaining case and required placement of a new stent. Symptom relief occurred in 11/15 cases (73 %) within 1 day, and within 2 days in the remaining 4 patients. Bleeding occurred in two patients (13 %): in one patient intraprocedural bleeding was successfully stopped during endoscopy; and delayed bleeding occurred in one patient requiring arterial embolization for catastrophic bleeding (patient died 10 days later). No cases of cholecystitis recurrence or biliary obstruction were observed during a median follow-up of 112 days (range 49 – 180 days).

Conclusions

Our data showed that EUS-guided gallbladder drainage with a specially designed stent is feasible and successful in patients with acute cholecystitis who are unfit for surgery.

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy represents the gold standard treatment for acute cholecystitis in patients without contraindications for early surgery 1 . In very elderly patients, and in those with severe comorbidities or who are unfit for surgery, a conservative approach is generally adopted 2 3 . In detail, percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration or drainage, transpapillary endoscopic gallbladder stenting and, more recently, endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) have been proposed 4 5 6 7 . Unfortunately, the endoscopic transpapillary approach is not always successful, and it is frequently challenging owing to the tortuous anatomy of the cystic duct or the presence of impacted stones 8 9 . On the other hand, the percutaneous procedure is hampered by a high rate of both adverse events (up to 12 %) and cholecystitis recurrence, as well as by long-stay hospitalization and catheter-related issues, including psychological aspects 10 11 . By avoiding an external drainage catheter placement, coupled with a very high success rate, the EUS-GBD method has recently become an attractive alternative for managing acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients who are unfit for surgery 12 .

Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) are novel devices generally used for pancreatic cyst or infectious walled-off pancreatic necrosis drainage 13 . More recently, these devices have also been employed for gallbladder drainage, fixing the gallbladder wall directly to the intestinal lumen, in order to prevent bile leaks and stent migration 14 . However, data on LAMSs for gallbladder drainage are still limited, and the AXIOS stent (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts) has usually been used for this purpose 15 . Alternatively, a short, fully silicone-covered, nitinol stent that was specifically designed with bilateral anchor flanges (NAGI-stent; Taewoong Medical Co., Gyeonggi-do, South Korea), may be used for transluminal drainage 16 . Indeed, such a stent is already employed for pancreatic cyst drainage 17 18 19 , and it has also been successfully used for gallbladder drainage 20 . We report the first case series on placement of the NAGI stent for nonsurgical EUS-GBD in patients with acute cholecystitis who are unfit for surgery.

Patients and methods

Patients

From April 2014 to July 2016, all consecutive patients with acute cholecystitis who were unfit for urgent cholecystectomy after surgical and anesthesiological evaluation were considered for this study. Acute cholecystitis was diagnosed when a patient met the Tokyo guideline criteria for cholecystitis, including a constellation of classic symptoms (right upper quadrant pain, fever, leukocytosis), together with radiological findings (abdominal ultrasound or computed tomography scan) of a thickened gallbladder wall 21 . All of these patients were offered an alternative nonsurgical approach, including percutaneous, transpapillary, or EUS-GBD. Data from those patients accepting the EUS-GBD procedure were systematically collected. Patients gave their informed consent before the endoscopic procedure.

EUS-guided gallbladder drainage

The EUS-GBD procedure was performed in two Italian tertiary endoscopy centers by four experienced endoscopists with a large experience in the management of complex biliary problems (> 500 EUS/endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP] procedures performed yearly). A linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT180 [Olympus, Tokyo, Japan] or EG-3870 UTK [Pentax, Tokyo, Japan]) was used to identify the gallbladder through the gastric antrum or the duodenal bulb. When feasible, the transduodenal approach was favored. After assessment of local vascular structures with color-flow Doppler, one of the following two approaches was chosen. The gallbladder was punctured with a 19-gauge needle (ECHO-19; Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, USA), and bile aspiration was performed confirming the correct position. Then, a 0.035-inch guidewire (Hydra Jagwire; Boston Scientific) was advanced through the needle and coiled within the gallbladder. Dilation of the access was achieved with a 10 Fr cystotome (CST-10; Cook Medical). Alternatively, the gallbladder was punctured directly with a 10 Fr cystotome, also achieving access dilation, and a 0.035-inch guidewire was advanced and coiled into the gallbladder. At the end of the procedure, a fully covered metallic stent, with bilateral anchor flanges (NAGI stent; Taewoog Medical Co.) was placed under fluoroscopic guidance. The NAGI stents used were 20 or 30 cm in length and 12 – 16 Fr in diameter, with flared ends of 20 mm 16 .

Outcomes

Technical and clinical success, as well as adverse events and outcome at follow-up, were evaluated. In detail, the technical success was defined as correct stent deployment across the duodenum or the stomach into the gallbladder, as demonstrated by appropriate bile and contrast flow through the stent. Clinical success was defined as resolution of acute cholecystitis symptoms, with regression of biochemistry and radiological alterations. Early and late procedure-related adverse events, and 30-day mortality were recorded. Ward nurses recorded patients’ pain level every day during hospitalization.

Results

A total of 16 patients (mean age 84.8 years, range 49−97 years; nine males) underwent EUS-GBD for gallbladder decompression. Indications for the procedure included calculous cholecystitis (12 cases), acalculous cholecystitis (one case), and biliary obstruction of post-transpillary ERCP biliary stenting (2 pancreatic cancer and 1 cholangiocarcinoma). Transduodenal access was performed in 13 patients (81 %), and a transgastric approach was preferred in the remaining 3 patients. The gallbladder was punctured with a 19-gauge needle in 10 patients, and directly with a 10 Fr cystotome in the remaining 6 cases.

Technical and clinical success

As shown in Table 1 , EUS-GBD was technically successful in all cases at first attempt ( Fig. 1 , Fig. 2 ). However, clinical success was achieved in only 15 patients (94 %). In the remaining patient, the clinical failure was due to multiple stones (1.5 cm in diameter) that impacted the NAGI stent lumen early after its successful positioning in the gallbladder. Thus, a double-pigtail plastic stent (10 Fr, 10 cm; Cook Endoscopy) was placed during the same session in order to guarantee the gallbladder drainage. However, the patient experienced cholecystitis recurrence 7 days after the procedure, and was successfully re-treated by placement of a new NAGI stent from the gastric antrum.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics and procedure outcomes.

| Sex | Age, years | ASA score | Cause of cholecystitis | Stent feature length, diameter | Technical success | Clinical success | Procedure-related complications |

| M | 81 | III | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| M | 88 | III | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 14 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| F | 86 | IV | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| F | 83 | II | Pancreatic mass | 2 cm; 14 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| F | 88 | II | Acalculous | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| M | 79 | II | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| M | 91 | II | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 14 Fr | Yes | No | Stent occlusion |

| M | 87 | III | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| F | 90 | IV | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | Delayed bleeding |

| F | 94 | II | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| F | 97 | IV | Biliary stones | 2 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Not | No |

| F | 93 | II | Biliary stones | 3 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| M | 77 | III | Biliary stones | 3 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| M | 85 | II | Pancreatic mass | 3 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | Acute bleeding |

| M | 49 | III | Cholangiocarcinoma | 3 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

| M | 89 | III | Biliary stones | 3 cm; 16 Fr | Yes | Yes | No |

M, male; F, female; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

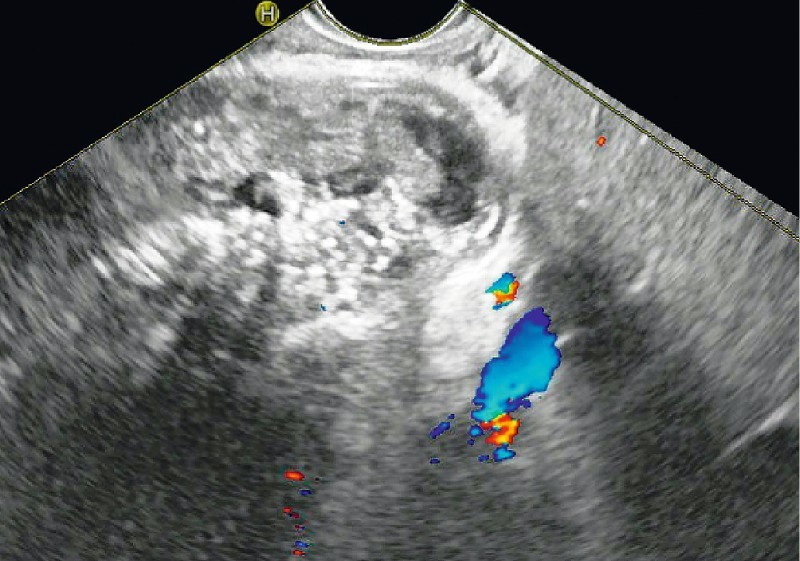

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic ultrasound image of gallbladder with marked wall thickness, and with the Doppler signal clearly detecting the site of vascular structures.

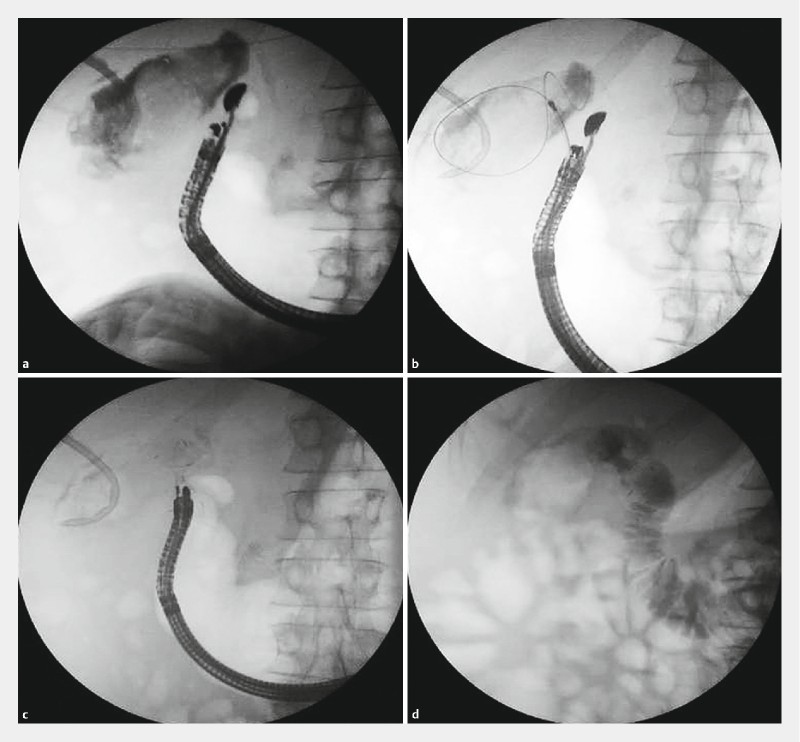

Fig. 2.

Stent placement for acute cholecystitis. a Gallbladder lumen opacification with contrast medium after direct 10 Fr cystotome puncture and insertion of metallic guidewire. b The catheter of the stent was pushed into the gallbladder over the guidewire. c The stent was deployed across the gallbladder and duodenal bulb wall. d Radiological control showing the stent correctly positioned.

Adverse events

Regarding the procedure-related adverse events, mild bleeding from the gastric wall occurred in one patient, and was successfully treated during the same endoscopy session. A 90-year old female with comorbidities experienced massive bleeding from a collateral cystic artery, with severe anemia 15 days following stent placement. After an unsuccessful endoscopic attempt at hemostasis, radiological embolization was successfully performed. However, the patient died 10 days later from an acute cerebral ischemic attack.

Clinical outcome and follow-up

Among the 15 patients with clinical success, symptoms relief occurred in 11 patients (73 %) within the first day after the procedure, and in the second day in the remaining 4 patients. At follow-up, six additional patients died as a result of myocardial infarction at 2 and 6 months in two cases, acute renal failure after 6 months in one case, pancreatic cancer after 7 months in two cases, and cholangiocarcinoma after 5 months in the remaining case. When excluding the patient described above, no cholecystitis recurrence or biliary obstruction were observed at a median follow-up of 112 days (range 49−180 days). No patient underwent cholecystectomy.

Discussion

The management of patients with acute cholecystitis who are unfit for surgery – such as those who are critically ill or very elderly with advanced American Society of Anesthesiologists score, or those with an inoperable malignancy – is challenging 22 23 . Nonsurgical approaches include either radiological or endoscopic procedures. Although a similar efficacy between the two approaches has been observed 24 , the advantage of EUS-GBD over percutaneous cholecystostomy is fewer adverse events in patients who are unfit for cholecystectomy 25 26 . Among the endoscopic approaches, the EUS-GBD procedure was first introduced in 2007 27 , and LAMS placement has been the more frequently used procedure in the past years. In detail, the AXIOS stent has been employed, with the advantage of gaining gallbladder drainage without radiological guidance 14 15 . However, the AXIOS stent is quite costly (3000 euros in Italy). Alternatively, the NAGI stent may be used for transluminal drainage, including pancreatic cyst and cholecystitis [16−20], and the cost of this device is distinctly lower (1000 euros in Italy) than LAMS (AXIOS or SPAXUS). Although NAGI stent placement requires the use of additional endoscopic devices (19-gauge needle, metallic guidewire, cystotome), the overall cost is lower than 2000 euros, and it further decreases when the gallbladder is directly punctured with the cystotome. Moreover, according to manufacturer labeling, removal of the NAGI stent may be safely performed.

To our knowledge, this is the first large case series of EUS-GBD using NAGI stent placement in patients with calculous or acalculous cholecystitis who are unfit for surgery. Correct stent deployment was technically successful in all patients, with two stents being required in one patient via the duodenal and gastric approaches, respectively. Clinical success was not achieved in one patient (6 %) because of early stone impaction. For the remaining cases, the regression of cholecystitis symptoms occurred within 24 hours in two-thirds of cases, and within 2 days in the remaining cases. Our data showed technical and clinical success rates of 100 % and 94 %, respectively. Of note, these results are comparable to the previous estimates of 91.5 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 82.5−96.8) and 90.1 % (95 %CI 80.7−95.9) for technical and clinical success rates, respectively, when the AXIOS stent was used 14 . Although the NAGI stent exerts a lower lumen-apposing force compared with LAMSs 28 , no stent migration occurred in our series. Overall, bleeding occurred in two patients (13 %) – one intraprocedural bleed that was successfully stopped during endoscopy and one delayed bleeding that required arterial embolization. In our case series, the procedure-related mortality was 6 % (one patient). Our data are similar to those reported in a previous pooled-data analysis of EUS-GBD procedures, where a 9.9 % incidence of procedural adverse events was estimated 14 .

This study has some limitations, including the retrospective design, the small number of patients included, and the relatively short follow-up that was due, at least in part, to the overall short survival period, as expected for critically ill patients with a mean age of 85 years.

In conclusion, data from this series showed that EUS-GBD with the NAGI stent is feasible and successful in patients with cholecystitis who are unfit for surgery. When considering its lower cost, NAGI stent placement would appear to be an attractive option in selected patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Coccolini F, Catena F, Pisano M et al. Open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Systematic review and meta-analyis. Int J Surg. 2015;18:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron T H, Grimm I S. Nonsurgical management of cholecystitis: a tailored approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1037–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatzidakis A A, Prassopoulos P, Petinarakis I et al. Acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy vs conservative treatment. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1778–1784. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang W S, Lim J U, Joo K R et al. Outcome of conservative percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis and risk factors leading to surgery. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2359–2364. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3961-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mutignani M, Iacopini F, Perri V et al. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis: technical and clinical results. Endoscopy. 2009;41:539–546. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khasbab M A, Levy M J, Itoi T et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:993. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peñas-Herrero I, de la Serna-Higuera C, Perez-Miranda M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage for the management of acute cholecystitis (with video) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:35–43. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itoi T, Coelho-Prabhu N, Baron T H. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage for management of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pannala R, Petersen B T, Gostout C J et al. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage: 10-year single center experience. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2008;54:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakkaloglu H, Yanar H, Guloglu R et al. Ultrasound guided percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk patients for surgical intervention. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7179–7182. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i44.7179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spira R M, Nissan A, Zamir O et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in critically ill patients with acute calculus cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 2002;183:62–66. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00849-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi J-H, Lee S S, Choi J H et al. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:656–661. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itoi T, Binmoeller K F, Shah J et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderloni A, Buda A, Vieceli F et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural stenting for gallbladder drainage in high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5200–5208. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4894-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patil R, Papafragkakis C, Anand S et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided placement of the lumen-apposing self-expandable metallic stent for gallbladder drainage: a promising technique. Ann Gastroenterol. 2016;29:162–167. doi: 10.20524/aog.2016.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weilert F, Binmoeller K F et al. Specially designed stents for translumenal drainage. Gastrointest Interv. 2015;4:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoi T, Nagashwar Reddy D, Yashuda I. New fully-covered self-expandable metal stent for endoscopic ultrasonography-guided intervention in infectious walled-of pancreatic necrosis (with video) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:403–406. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tellez-Avila F I, Villabos-Garita A, Ramirez-Luna M A. Use of a self-expandable metal stent with an anti-migration system for endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of a pseudocyct. World J Gastrointest Endosco. 2013;5:297–299. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i6.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keane M G, Sze S F, Cieplik N et al. Endoscopic versus percutaneous drainage of symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections: a 14-year experience from a tertiary hepatobiliary centre. Surg Endosc. 2016:30; 3730–3740. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4668-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rai P, Singh A, Rao R et al. First report of endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholecystogastrostomy with a Nagi covered metal stent for palliation of jaundice in extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2014;46:e334–e335. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takada T, Strasberg S M, Solomkin J S et al. Tokyo Guidelines Revision Committee. TG13: Updated Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0566-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widemar J, Singhal S, Gaidhane M et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided endoluminal drainage of the gallbladder. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:525–531. doi: 10.1111/den.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi J H, Lee S S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided endoluminal drainage for acute cholecystitis. Dig Endosc. 2014;27:1–7. doi: 10.1111/den.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irani S, Ngamruengphong S, Teoh A et al. Similar efficacies of endoscopic ultrasound gallbladder drainage with a lumen-apposing metal stent versus percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teoh A YB, Serna C, Penas I et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage reduces adverse events compared with percutaneous cholecystostomy in patients who are unfit for cholecystectomy. Endoscopy. 2017;49:130–138. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-119036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyberg A, Saumoy M, Sequeiros E V et al. EUS-guided versus percutaneous gallbladder drainage: isn’t it time to convert? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016 doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwan V, Eisendrath P, Antaki F et al. EUS-guided cholecystenterostomy: a new technique (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:582–586. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teoh A Y, Ng E K, Chan S M et al. Ex vivo comparison of the lumen-apposing properties of EUS-specific stents (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]