Abstract

Feedback signals from daughter cells to stem cells are well studied and known to provide important feedback cues. Emerging evidence shows that stem cells also send feedforward signals to their progeny. Complex circuits involving both negative and positive feedback and feedforward signals likely contribute to robust tissue maintenance and regeneration.

Introduction

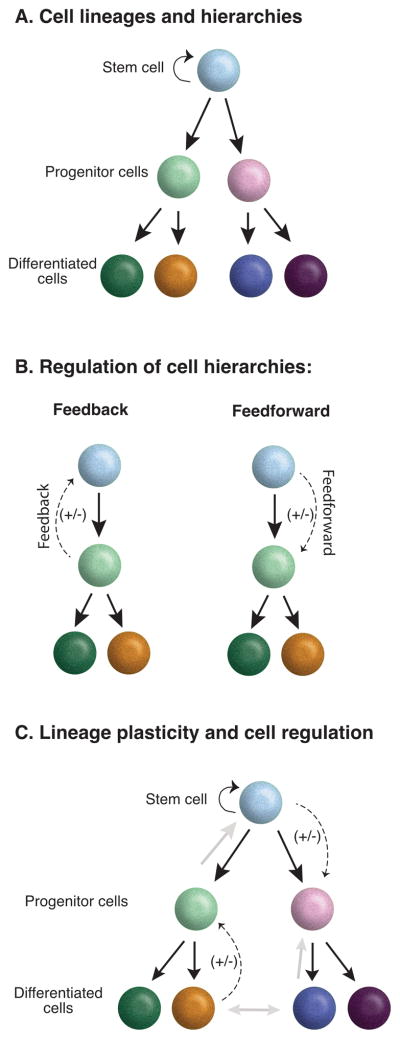

Tissues are often comprised of cells within a lineage hierarchy (Figure 1A). In these tissues, mechanisms must exist to ensure that progenitor and differentiated cells are present in specific proportions. In the context of injury and regeneration, myriad studies have documented the presence of feedback signals from daughter cells that signal stem cells to cease replication following the re-establishment of sufficient daughter cell numbers (Figure 1B). These signals can be arbitrarily defined as positive or negative with respect to a particular cellular phenomenon (i.e. a circuit that is a positive feedback signal for replication can also be described as a negative feedback signal for quiescence). Recent evidence suggests that the interaction of stem cells and their daughters is more complex. In particular, stem cells seem to send feedforward signals to their own progeny to regulate their behavior (Figure 1B). We suggest that the maintenance of normal tissues and tissue regeneration are likely to require both feedback and feedforward signals. In the future, it is likely that complex wiring diagrams will be needed to explain the regulatory circuitry of tissues in the same manner as those used to depict gene or neural networks. These diagrams must take into account lineage relationships, but in contrast to the case of neurons in circuits or genes in transcriptional networks, cells are plastic and interconvertible. Thus, even the nodes (in this case cells) of new circuit diagrams will need to account for this scenario and be depicted as interconvertible (Figure 1C). Thus, an attempt to formulate a set of rules governing the “logic” used by tissues to restore their integrity after damage, will require a working level understanding of lineage, intercellular signals, and plasticity, in combination with an understanding of how all of these phenomenon are inter-related and balanced.

Figure 1.

Modes of cell regulation within lineage hierarchies. Schematic representation of cellular hierarchies in tissues (A). Cells are arranged in cellular hierarchies in many diverse tissues wherein stem cells generate increasingly differentiated functional progeny (B). Schematic representation of possible modes of cell regulation within a lineage hierarchy including classic feedback regulation and possible feedforward regulation originating from signals sent by the stem cell itself. Both feedback and feedforward signals could be positive or negative with reference to a particular cellular process (C). Schematics that incorporate lineage, plasticity, and signaling. Solid black arrows depict the lineage, grey arrows depict lineage plasticity, and dotted arrows depict signals.

Feedback regulation

In many adult animal tissues, stem/progenitor cells are known to generate differentiated progeny at some regular pace during steady state conditions, and then accelerate the production of progeny cells after injury. By definition, an essential feature of this relationship of cells is lineage: namely that a stem cell or progenitor cell is located at the apex of a hierarchy, whereas the most mature daughter cells are located at the bottom of the hierarchy (Figure 1A). The paradigmatic form of homeostatic regulation, negative feedback regulation, occurs when differentiated cells inhibit the replication and differentiation of their parent stem or progenitor cells using a feedback signal (Figure 1B). The classic example of negative feedback in vertebrate stem cell systems was first described in hematopoiesis. Here, a deficiency of white blood cells, platelets, or red blood cells is sensed and progenitor cells are activated to proliferate and restore the proper cell numbers of a given lineage or lineages. Many examples of feedback loops have also been identified in solid tissues. In the hair follicles and in the olfactory epithelium, the immediate progeny of epithelial stem cells send feedback signals to their parent stem cells to restrain their division. In the hair follicles, fully committed cytokeratin 6-expressing daughter cells negatively regulate bulge stem cell replication through feedback signals mediated by paracrine morphogens such as Fgf18 and BMP6. When differentiated cells are lost through injury, the restraining signal is lost and stem cells proliferate until newly differentiated cells are formed (Hsu et al., 2011). As the differentiated cells reach their normal numbers, the feedback signal builds and stem cells are once again restrained.

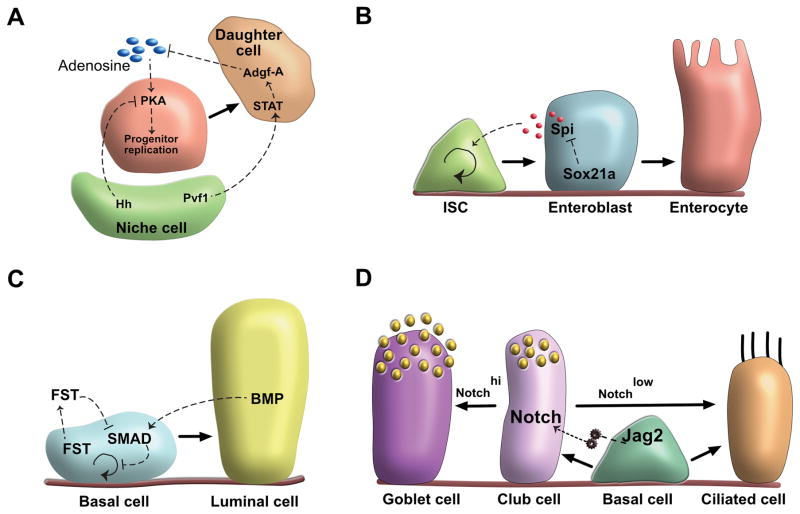

In the Drosophila hematopoietic organ, extracellular adenosine promotes hematopoietic progenitor cell replication and tissue turnover by signaling through the Adenosine receptor (AdR) and activating the PKA pathway within blood progenitor cells. Remarkably, daughter cells secrete Adenosine deaminase growth factor -A (Adgf-A) which acts to enzymatically decrease extracellular adenosine levels. Thus, in a variant of a classic negative feedback mechanism mediated by a growth factor, daughter cells inhibit progenitor cell replication by secreting an enzyme. Niche cells, on the other hand, inhibit progenitor cell replication both directly through a paracrine hedgehog signal that acts to inhibit PKA activity in progenitor cells, as well as indirectly through a Pvf1/Stat/Adgf-A pathway that involves daughter cells as a conduit for a second niche-derived quiescence promoting signal (Figure 2A) (Mondal et al., 2011). Thus, daughter cells not only directly negatively regulate progenitor cell replication, but they also transmit one of the two niche-derived signals that serve to further inhibit progenitor cell replication. Such complex circuits involving multiple levels of feedback regulation are likely “designed” to prevent unwanted and potentially pathologic progenitor cell-mediated turnover or cancer. How such circuits enhance robustness or permit greater control remains to be seen. In addition to resisting unwanted stimuli that encourage progenitor cell replication, perhaps the multiple pathways approach also allows other putative signals multiple entry points to impinge on tissue homeostasis. In the case of more complex cellular hierarchies, one can easily imagine that the circuits will be as complex as those governing gene regulation or neuronal processing. Furthermore, if we account for systemic stimuli and migratory or transient cell populations, the diagrams are likely to become more complex than those of neural networks, even before we take into account cell plasticity.

Figure 2.

Schematics representing different tissues using varied forms of cellular communication within a lineage hierarchy (solid arrows indicate cell lineages; dotted arrows represent signaling between different cells). A, In the fly hematopoietic organ, high levels of extracellular adenosine cause hematopoietic progenitor cell replication by enhancing PKA activity in the progenitor cells. Conversely, PKA activity is directly inhibited in progenitor cells by a niche cell-derived paracrine hedgehog signal that causes progenitors to remain quiescent. Remarkably, niche cells also send Pvf1 ligands to daughter cells and activate the STAT signaling pathway in these daughters which in turn positively regulates their expression of Adenosine deaminase growth factor-A. Daughter cells then secrete this enzyme which acts to decrease extracellular adenosine levels, again resulting in progenitor cell quiescence. Thus, differentiated cells negatively regulate progenitor cell replication directly, and also act as a conduit for a niche-derived signal that further inhibits progenitor cell replication. B, In the Drosophila midgut, control of mitogen expression by the Sox21a transcription factor in enteroblasts regulates the proliferation of intestinal stem cells (ISCs) through a negative feedback mechanism. Interestingly, the negative feedback signal, Spi1, is de-repressed during regeneration to allow increased ISC replication. C, In the airway epithelium, SMAD activity in basal cells is inhibited by basal cell-derived follistatin (FST), thereby promoting basal cell replication in an autocrine fashion. However, follistatin is downregulated following injury, which in turn activates SMAD signaling to initiate stem cell differentiation. Daughter cells, in contrast, send a positive feedback BMP signal that activates SMAD signaling in stem cells to inhibit basal cell replication when daughters accumulate. D, The airway epithelium employs feedforward signaling in which a tonic feedforward Notch ligand signal, originating in airway epithelial basal stem cells, activates steady state notch signaling in the daughter luminal cells to tonically maintain secretory daughter cells identity and stability.

How else are negative feedback loops deployed in regenerative systems? Interestingly, an “overshoot” phenomenon involving the production of excess differentiated cells has been proposed. Presumably this hyperplasia results from a delay in the production of sufficient inhibitory signals from differentiated cells to halt progenitor cell replication. This phenomenon of “overshoot” is classic for any feedback regulatory system, in which a regulated variable has to be sensed before a control system can be engaged. This results in an inevitable time delay. As a metaphor, a thermostat must sense a decrement in temperature before a heating mechanism can be engaged. By analogy, rapid regeneration results in an excess of cells and the “size setpoint” of a given tissue is exceeded before a compensatory mechanism to restore normal cell numbers is engaged. As a result of the hyperplasia, the regenerating tissue then needs to undergo “pruning” to restore a steady state distribution of cells.

Somewhat less intuitively, differentiated cells are known to send positive feedback signals to encourage progenitor cell replication. Paneth cells, which themselves derive from intestinal stem cells, in the mammalian gut send positive feedback signals to adjacent intestinal stem cells to promote their replication (Sato et al., 2011). Perhaps, this amplifying mechanism ensures continual steady state intestinal stem cell replication, thus setting the rate of overall intestinal epithelial turnover. Similarly, in the fly midgut the enteroblasts, the immediate daughters of intestinal stem cells, cause their parent cells to replicate using a secreted mitogen that acts as a positive feedback regulator of replication. At homeostasis, the positive feedback loop causing stem cell replication is suppressed by the action of Sox21a, an enteroblast transcriptional regulator that represses the expression of Spi, which serves as a mitogen for intestinal stem cells. So, at steady state, enteroblasts suppress stem cell replication by inhibiting a positive feedback signal. However, following injury, Sox21a is transiently down regulated. This results in the derepression of spi, which then activates replication in intestinal stem cells (Figure 2B) (Chen et al., 2016). In Sox21a mutants, expression of spi ligands is increased in enteroblasts. This results in elevated intestinal stem cell replication followed by accumulation of Sox21a mutant enteroblasts resulting in cancer-like outgrowths. We speculate that it is likely that many tonic signals operate amongst cells to actively suppress tissue turnover. Perhaps this tonic expenditure of energy allows the system to be poised for rapid regeneration. In some tissues, multiple feedback signals from the same cell exist to regulate stem cell behaviors.

Autocrine regulation of stem cells

More recently, another signaling circuit based on an autocrine-signaling loop has been shown to mediate epidermal stem cell self-renewal (Lim et al., 2013). In this example, stem cells produce an autocrine Wnt signal to cause their own replication. Remarkably, they regulate the action of the Wnt signal by concomitantly producing a Wnt antagonist DKK1 that diffuses farther than the corresponding Wnt signal, resulting in short range Wnt signaling activation and simultaneous long range inhibition. In contrast, stem cells of the airway normally produce an antagonist of BMP/SMAD signaling, follistatin that promotes a baseline level of stem cell replication using this autocrine circuit. Therefore, follistatin serves as a tonic autocrine positive regulator of stem cell replication. However, in the course of injury, the expression of follistatin is transiently upregulated, and this result in the transient downregulation of SMAD signaling in the epithelium which in turn causes the stem cells to replicate and generate more epithelial cells. Subsequently, newly generated daughter cells send a positive feedback BMP signal to stem cells that activates SMAD signaling to inhibit basal cell replication when daughters accumulate. Such dynamically regulated autocrine signals thus serve to not only set steady state rates of turnover, but can be modulated for rapid action following injury. This harkens once again to the theme that a tonic level of intercellular signaling allows stem cells to be poised for rapid regeneration (Figure 2C) (Tadokoro et al., 2016). Of note, in these cases, “autocrine” is defined loosely as a signal from a population of cells that affects the behavior of the same population of cells that send the signal. Strictly speaking, an autocrine signal acting on the same cell that produced the signal has not been conclusively demonstrated.

Feedforward regulation

Although stem cell niche and feedback signaling mechanisms have been well scrutinized, little is known about how or if stem or progenitor cells can produce signals that affect their own progeny. Indeed, this less intuitive form of regulation, that we refer to as “feedforward regulation” is often employed by engineers to design rapidly responsive systems. Practically, this method of control is employed because feedforward signals are anticipatory, and are activated before an abnormality of a given control system is generated. Stated otherwise, since a feedback signal relies on the “sensing” of some perturbation, it is inherently slower than feedforward control (and thereby contributing to the “overshoot” phenomenon described above). Do such feedforward signals exist in biological systems? Indeed, early work from McKay postulated that such feedforward signals could be employed in neural circuit function. In developmental systems, the first reference to such a forward mode of communication came from studies in the fly gut where intestinal stem cells send signals to their progeny in order to maintain their fate (Ohlstein and Spradling, 2007). Analogously, mammalian airway stem cells send a tonic feedforward signal to their own progeny to regulate the actual maintenance of those differentiated progeny. Thus, the stem cells themselves serve as functional “progenitor cell niches” in the same way that conventional niche cells support the maintenance of stem cells (Pardo-Saganta et al., 2015).

Although there are few formal examples supporting the existence of these forward signals to date, we would like to suggest that “feedforward regulation” by stem cells is likely to exist in many contexts across many tissues. Despite the prior use of this term in engineering contexts, physiologic systems, transcriptional networks and even distinct developmental contexts, here we use “feedforward regulation” to denote a more complex form of regulation that involves a minimum of 3 nodes (in this case, cells). We re-purpose the terminology in the context of lineage hierarchies in order to contrast feedforward cell regulation from the better known examples of feedback regulation (Figure 1B and Figure 2D). To expand on this point, we note that Notch signals in fly intestinal stem cells occur at varying levels that, in turn, determine daughter cell fate. Thus, it stands to reason that the dynamic regulation of these forward Notch signals could be employed to alter the distribution of daughter cell types. We speculate that in mammalian epithelial and other stem cell systems, that transient fluctuations or directed alterations in feedforward signals could alter the behavior of progeny cells. Indeed, we further propose that stem cells may orchestrate tissue wide changes using feedforward signaling, rather than merely acting as sources of new cells. This fundamentally reframes our concept of what it means to be a stem cell. Such an active role may occur in some tissue contexts, while in others it may not.

Complex Regulatory Circuits within Tissues

Many diverse juxtaposed cells within tissues are likely to be communicating with one another; resulting in many forms of simultaneous intercellular control that together contribute to tissue homeostasis. Furthermore, these signals could be positive or negative (arbitrarily defined with respect to a particular cellular process) and control any of a myriad panoply of cell behaviors ranging from proliferation to differentiation to death to functional activation. Indeed, it is very likely that for any one given cell behavior, multiple negative and/or positive signals are required to perpetuate or terminate the behavior. In a tissue as a whole, feedback, feedforward, and autocrine signals are all likely occurring amongst an ensemble of cells, and these circuits probably contribute to the robustness of homeostatic control mechanisms, just as they do in transcriptional circuits underlying gene regulation.

While investigating the control mechanisms that govern tissue behavior, many surprises are likely to occur. For example, recent studies in the airway epithelium have demonstrated that differentiated mature ciliated cells do not send negative feedback signals to stem cells to regulate their replication. These findings suggest that not all differentiated progeny, and their anticipated feedback signals, control stem cell replication in accord with the classic paradigm of feedback regulation (Pardo-Saganta et al., 2015). Indeed, recent mathematical modeling, based on the data collected from the mammalian airway, has suggested that lineage control mechanisms provide an evolutionary “economic” advantage in that their “design” reflects an optimal strategy for ensuring homeostatic lineage stability and minimizing the variation of cell population size (Pardo-Saganta et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016; Tata et al., 2013). This implies that control networks are “constructed” not only to set population sizes, and thus their relative numbers, but that they are optimized to minimize variance. Interestingly, engineers do not use anticipatory feedforward control mechanisms in any system, without the concomitant deployment of a feedback signal. This prevents runaway conditions, in which an anticipatory feedforward signal results in an overly exuberant response that is not counterbalanced by a feedback signal that is responsive to the aforementioned “overshoot” problem.

Finally, recent studies point to the importance of the spatiotemporally coordinated control of stem cells (Rompolas et al., 2016). The feedback and feedforward regulation of parent and daughter cells will undoubtedly be affected by tissue topology. In the setting of a diffusible growth factor, the relative distances of daughter and parent cells would be predicted to regulate the degree of any given effect. In many tissues, daughter cells progressively move further and further away from their stem cell parents with time, as is the case with stratified epithelia. This spatial flux of cells in turn delimits the degree and timescale of intercellular communication. In the extreme case, a cell contact-mediated pathway would operate only when daughter and stem cells are directly adjacent. If parent and progeny cells are in contact only briefly, as in high turnover tissue like the epidermis or intestine, any regulation would occur very briefly. However, in a quiescent tissue, such as the uninjured airway epithelium, stem cells could tonically signal to their adjacent progeny cells for extended periods of time to affect aggregate tissue behavior. Thus, both time and space will affect regulatory control circuitry. Future studies will also need to address how a particular degree of injury (for example, loss of increasing numbers of differentiated cells) quantitatively and qualitatively alters the degree of feedback or feedforward signaling, as well as the thresholding of the reception of those signals.

Different control circuitries are known to be associated with different response characteristics, and much can likely be gained by borrowing from lessons learned in fields where control theory has been more intensively scrutinized, as in gene transcription. However, in stem cell hierarchies, we are also confronted by the added complexity that cell lineages are plastic, and that the “nodes” of these cellular networks are interconvertible. Thus, the models and theories of control networks in cellular systems are likely to be even more complex than those that regulate gene and neural networks. Thus, new conventions for the diagrammatic representation of cellular control networks, in analogy to those drawn for neural and transcriptional circuits, will need to take into account not only signals, but the interconvertibility of the cells that produce those signals (Figure 1C).

Acknowledgments

J.R. is a HHMI Faculty Scholar, a New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Investigator, a Maroni Research Scholar at MGH, and a member of the Ludwig Cancer Institute at Harvard Medical School. We thank all the members of the Rajagopal Laboratory for constructive comments. This research was supported by grants from the NIH (R01HL116756, R01HL118185 to J.R.; K99HL127181 to P.R.T.;). We apologize to the myriad authors whose work we could not include in this brief conceptual review.

References

- Hsu YC, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Dynamics between stem cells, niche, and progeny in the hair follicle. Cell. 2011;144:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim X, Tan SH, Koh WLC, Chau RMW, Yan KS, Kuo CJ, van Amerongen R, Klein AM, Nusse R. Interfollicular epidermal stem cells self-renew via autocrine Wnt signaling. Science. 2013;342:1226–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1239730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal BC, Mukherjee T, Mandal L, Evans CJ, Sinenko SA, Martinez-Agosto JA, Banerjee U. Interaction between differentiating cell- and niche-derived signals in hematopoietic progenitor maintenance. Cell. 2011;147:1589–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein B, Spradling A. Multipotent Drosophila intestinal stem cells specify daughter cell fates by differential notch signaling. Science. 2007;315:988–992. doi: 10.1126/science.1136606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Saganta A, Tata PR, Law BM, Saez B, Chow RDW, Prabhu M, Gridley T, Rajagopal J. Parent stem cells can serve as niches for their daughter cells. Nature. 2015;523:597–601. doi: 10.1038/nature14553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompolas P, Mesa KR, Kawaguchi K, Park S, Gonzalez D, Brown S, Boucher J, Klein AM, Greco V. Spatiotemporal coordination of stem cell commitment during epidermal homeostasis. Science. 2016;352:1471–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Vries RG, van den Born M, Barker N, Shroyer NF, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Plikus MV, Komarova NL. Near Equilibrium Calculus of Stem Cells in Application to the Airway Epithelium Lineage. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro T, Gao X, Hong CC, Hotten D, Hogan BLM. BMP signaling and cellular dynamics during regeneration of airway epithelium from basal progenitors. Dev Camb Engl. 2016;143:764–773. doi: 10.1242/dev.126656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tata PR, Mou H, Pardo-Saganta A, Zhao R, Prabhu M, Law BM, Vinarsky V, Cho JL, Breton S, Sahay A, Medoff BD, Rajagopal J. Dedifferentiation of committed epithelial cells into stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2013;503:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]