Abstract

Despite often minute concentrations in vivo, D-amino acid containing peptides (DAACPs) are crucial to many life processes. Standard proteomics protocols fail to detect them as D/L substitutions do not affect the peptide parent and fragment masses. The differences in fragment yields are often limited, obstructing the investigations of important but low abundance epimers in isomeric mixtures. Separation of D/L-peptides using ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) was impeded by small collision cross section differences (commonly ~1%). Here, broad baseline separation of DAACPs with up to ~30 residues employing trapped IMS with resolving power up to ~340, followed by time-of-flight mass spectrometry is demonstrated. The D/L-pairs co-eluting in one charge state were resolved in another, and epimers merged as protonated species were resolved upon metalation, effectively turning the charge state and cationization mode into extra separation dimensions. Linear quantification down to 0.25% proved the utility of high resolution IMS-MS for real samples with large inter-isomeric dynamic range. Very close relative mobilities found for DAACP pairs using traveling-wave IMS (TWIMS) with different ion sources and faster IMS separations showed the transferability of results across IMS platforms. Fragmentation of epimers can enhance their identification and further improve detection and quantification limits, and we demonstrate the advantages of online mobility separated collision-induced dissociation (CID) followed by high resolution mass spectrometry (TIMS-CID-MS) for epimer analysis.

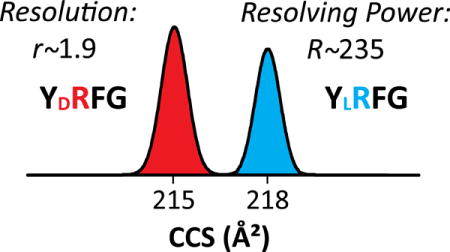

Graphical abstract

Nearly all biomolecules have one or more chiral centers (typically on the C atoms), with geometries often crucial to the life function. In enantiomeric pairs, all symmetry centers are inverted to form the mirror images. In particular, all α-amino acids (aa) except glycine have four different groups attached to the α-carbon, which allows left-handed (L) and right-handed (D) forms. From these, one can assemble peptides of any length comprising just L- or D- aa (enantiomers) and both forms (diastereomers or epimers). A species can have only one enantiomer, but numerous diastereomers with single or multiple D/L-substitutions in different positions.

No natural D-aa containing peptides (DAACPs) or proteins were known (except in bacterial walls) until the discovery of dermorphin in frog skin in 1981.1 Some 40 DAACPs are now found in eukaryotes such as arthropod,2–5 molluscan,6–9 and vertebrate.10–13 These peptides range from four to >50 residues, and are epimers of all-L peptides with D-aa often located in the 2nd position from the N-terminus.1,12–17

Such species have different conformations, resulting in distinct interactions with both chiral and non-chiral partners. Hence, DAACPs bind to receptors with different selectivity and affinity than the L-analogs, dramatically altering the biological function.18,19 For example, NdWFa enhances the heartbeat of sea slugs at 10−10 M whereas the L-analog NWFa is inactive even at 10−6 M.19 Many DAACPs were discovered by comparing the biological activities of natural and synthetic L-analog peptides. The unnatural stereochemistry of D-residues commonly renders DAACPs resistant to proteolytic degradation, making them a promising scaffold for next-generation drug design.20–22 Fundamentally, understanding the prevalence, substitution patterns, synthesis pathways, properties, and biomedical roles of DAACPs may help grasping the origin of extraordinary preference for L-aa across biology that is likely central to the genesis of life on Earth.

The number, abundance, and biomedical importance of DAACPs may be profoundly underestimated because of the paucity of analytical techniques for their detection and characterization. Unlike most post-translational modifications (PTMs), D/L-substitutions cause no mass shift for peptides or their fragments. Therefore, the standard mass spectrometry (MS) approach to PTM analysis (finding the precursors with mass shifts and tracking those for dissociation products to locate the PTM site) is moot for DAACP detection.

While DAACPs and L-analogs yield the same fragments in collision-induced dissociation (CID),23–25 electron capture/transfer dissociation (EC/TD),26,27 and radical-directed dissociation (RDD),28 the ratios of the peak intensities (ri,j = ai/aj for species i and j) generally differ. Hence, one can distinguish DAACPs and quantify them in binary epimer mixtures using standards. The quantification accuracy and fractional limits of detection (fLOD) and quantification (fLOQ) depend on the chiral recognition factor RCH (relative difference between ri,j involved). In ergodic CID, ions are first heated to transition states that typically reduce or obliterate the structural distinctions between isomers. Direct mechanisms like EC/TD and RDD fragment ions “instantly” from initial geometries and thus are more sensitive to subtle structural differences. Indeed, typical RCH increase from 1 – 18 (mean of 5) in CID to 5 – 30 (mean of 21) in RDD, reducing fLOD from ~ 5 – 10% to ~ 1 – 2%.28 Still, RCH and thus fLOD and fLOQ vary across D/L-peptide pairs widely and unpredictably, and fLOQ much under 1% is needed to truly explore the DAACP complement in global proteomes. Exceptional specific activity of DAACPs necessitates isomer quantification with dynamic range of >104 (fLOQ < 0.01%) impossible by existing MS/MS techniques. The MS/MS methods also cannot disentangle mixtures of more than two epimers or pinpoint the D-aa position(s).

This situation mandates epimer separations prior to or after the MS step. A complete separation would mean RCH capped only by the MS dynamic range, now typically ~105. The DAACPs elute differently in non-chiral and chiral liquid chromatography (LC)11,29 and capillary electrophoresis (CE),11,30 and were revealed by discrepancy of retention times (tR) between natural and synthetic peptides. However, those separations are slow, not always successful, and do not tell the number or location of D-aa (except by matching tR with exhaustive standard sets).

Condensed-phase separations are now increasingly complemented or replaced by ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) in gases that gained broad acceptance in proteomics thanks to speed and unique selectivity. All IMS approaches belong to two groups: linear (based on the absolute ion-molecule collision cross section or CCS, Ω, at moderate electric field, E) and non-linear (based on the evolution of Ω at high E). A fundamental challenge of linear IMS is the degree of orthogonality to MS, which particularly constrains the isomer resolution. Nonetheless, peptide isomers, including sequence inversions31 and PTM localization variants,32 were resolved by linear IMS using drift tubes with static uniform electric field.

Another linear IMS method is traveling-wave IMS (TWIMS) with dynamic field, implemented in Synapt quadrupole/IMS/time-of-flight MS instruments (Waters, Milford, MA). Even in the latest model (G2), a modest resolving power (R ~ 30 – 50 on the Ω scale) has permitted only partial (if any) separation of D/L isomers for all pairs reported.33,34 While its capability for MS/MS prior to the IMS stage enables localizing D-aa by IMS of epimeric fragments, the power of that novel strategy was also limited by IMS resolution.33 Ionization of peptides at high concentration routinely produces oligomers. Their morphologies also differ between DAACPs and L-analogs, potentially more than those for monomers.34 While some epimers were easier to distinguish as multimers, the general utility of that path remains unclear. One can sometimes enhance IMS resolution using shift reagents35 that preferentially complex specific chemical groups, but the similarity of D- and L-aa makes that approach unlikely to succeed here. However, metal cationization could improve or worsen separation of epimers by modifying their geometries in unequal ways.34

A direct path is raising the resolving power of linear IMS. In the new technique of trapped IMS (TIMS), a constant electric field component holds ions stationary against a moving buffer gas (making the effective drift length almost infinite) while a quadrupolar rf field radially confines them to avoid losses to electrodes.36,37 The TIMS devices provide R up to ~400 in a compact form38 and are readily integrated with various MS platforms, including time-of-flight (ToF) and Fourier Transform MS.39–42 The TIMS-MS systems have proven useful for rapid separation and structural elucidation of biomolecules,42–52 for example screening43 and targeted40 analysis of complex mixtures, tracking the isomerization kinetics,44–46 and characterizing the conformational spaces of peptides,53 DNA,47 proteins,54 and macromolecular complexes in native and denatured states.55

Here, we demonstrate the capability of linear IMS using TIMS to broadly resolve and identify D/L-peptide epimers, which commonly differ in mobility by just ~1%. The results are compared to separations of same species using the Synapt G2 platform under two different regimes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Reagents

Our study involves 10 epimer pairs with 4 – 29 residues (Table 1). The standards were selected to represent the relevant mass range while featuring single D-aa at different residues and locations, and include several cases prominent in biology. One pair (LHRH) comprises two DAACPs with one D-aa in different positions, namely pEHWDSYDWLRPG and pEHWSDYDWLRPG. The Achatin-I pair was synthesized by UW Biotechnology Center. Other standards were Dermorphin 1–4, Deltorphin I, Somatostatin-14, and GRF from American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA), and WKYMVM, LHRH, γ-MSH, and Neurotensins from Bachem (Torrance, CA). The peptides were dissolved in 50:50 H2O:MeOH (nESI with Synapt or TIMS) and 50:49:1 H2O/MeOH/MeCOOH (ESI/Synapt) to 2 μM (nESI/Synapt), 1 μM (nESI/TIMS), and 0.1 μM (ESI/Synapt). The peptide bradykinin 1–7 (756 Da, from Sigma Aldrich) was added as internal calibrant in lower concentration. Parts of those solutions were combined into isomolar binary mixtures. For GRF, we prepared mixtures with 5 μM of D-epimer and 0.012 – 5 μM of L-epimer. The instrument was initially calibrated using the Tuning Mix39 from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA).

Table 1.

Presently studied DAACPs. The D/L-residues are highlighted in red.

| Peptide | Sequence | MW, Da |

|---|---|---|

| Achatin-I | G AD | 408.41 |

| Dermorphin 1–4 | Y FG | 541.60 |

| Deltorphin I | Y FDVVG | 769.84 |

| WKYMVM | WKYMV | 857.09 |

| LHRH | pEHW WLRPG | 1311.45 |

| γ-MSH | YVMGHFR DRFG | 1570.77 |

| Somatostatin-14 | AGCKNFF KTFTSC | 1637.88 |

| Tyr11-Neurotensin | pELYENKPRRP IL | 1672.92 |

| Trp11-Neurotensin | pELYENKPRRP IL | 1695.96 |

| GRF | Y DAIFTNSYRKVLGQLSARKLLQDIMSR | 3357.88 |

TIMS-MS Experiments

We employed a custom nESI-TIMS unit coupled to an Impact Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA).36,37 The TIMS unit is run by custom software in LabView (National Instruments) synchronized with the MS platform controls.37 Sample aliquots (10 μL) were loaded in a pulled-tip capillary biased at 700–1200 V to the MS inlet. In TIMS, multiple isomers are trapped simultaneously at unequal longitudinal field (E) in different positions along the straight tunnel and sequentially eluted by ramping E down.36 Ion mobility separation depends on the gas flow velocity (vg), elution voltage (Velution) and base voltage (Vout).36,56 The mobility, K, is defined by

| (1) |

Each isomer emerges at a characteristic voltage (Velution − Vout). The instrument constant A was determined using known reduced mobilities of Tuning Mix components (K0 of 1.013, 0.835, and 0.740 cm2/(V.s) for respective m/z 622, 922, and 1222). The scan rate (Sr=ΔVramp/tramp), where tramp is the ramp duration, was optimized depending on the resolution needed for specific targets. The buffer gas was N2 at ambient temperature (T) with vg set by the pressure difference at funnel entrance (2.6 mbar) and exit (1.1 mbar, Figure S1). A rf voltage of 200 Vpp at 880 kHz was applied to all electrodes. The measured mobilities were converted into CCS (Å2) using the Mason-Schamp equation:

| (2) |

where q is the ion charge, kB is the Boltzmann constant, N is the gas number density, m is the ion mass, and M is the gas molecule mass.56

TWIMS-MS Experiments

We employed two Synapt G2 systems, one with a nESI source and one with high flow ESI source to probe the stability of peptide conformations and thus their separations with respect to the source conditions.57,58 Samples were infused at 0.03 μL/min (nESI) and 20 μL/min (ESI). The nESI source was operated in the positive ion mode with capillary at 2.0 KV and sampling cone at 30 V. The gas flows were 0.5 L/min N2 to the source (not heated), 0.18 L/min He to the gate, and 0.09 L/min N2 to the drift cell (yielding the pressure of 2.6 Torr). The ESI system used similar conditions with slightly lower pressure (2.2 Torr). The traveling wave had the height of 40 V and velocity of 600 m/s (nESI) and 650 m/s (ESI), leading to slightly different arrival times (tA) in the two platforms.

Data Processing

The IMS spectra from Synapt were aligned by linear scaling (within 1%) using the internal calibrant (redundant with TIMS given the epimer separation). The IMS peaks were fitted with Gaussian distributions using OriginPro 8.5. For TIMS, the resolving power R and resolution r are defined as R = Ω/w and r = 1.18*(Ω2-Ω1)/(w1+w2), where w is the full peak width at half maximum (FWHM). Same metrics for Synapt were computed with Ω replaced by tA. As those depend on Ω non-linearly (close to quadratically),59 the true R on Ω scale differs from the apparent value (and often is approximately double that). However, the key feature resolution remains the same.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As is normal with ESI, we observed singly protonated species for peptides with up to seven residues (Figures S2 and S3) and multiply protonated species for longer sequences (Figures S4 and S5). We acquired the IMS spectra for individual L- and D-stereoisomers and confirmed the result using mixtures. The measured Ω (from TIMS), tA (from Synapt), and R and r metrics for both are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

Synapt and TIMS Separation for Protonated Peptides

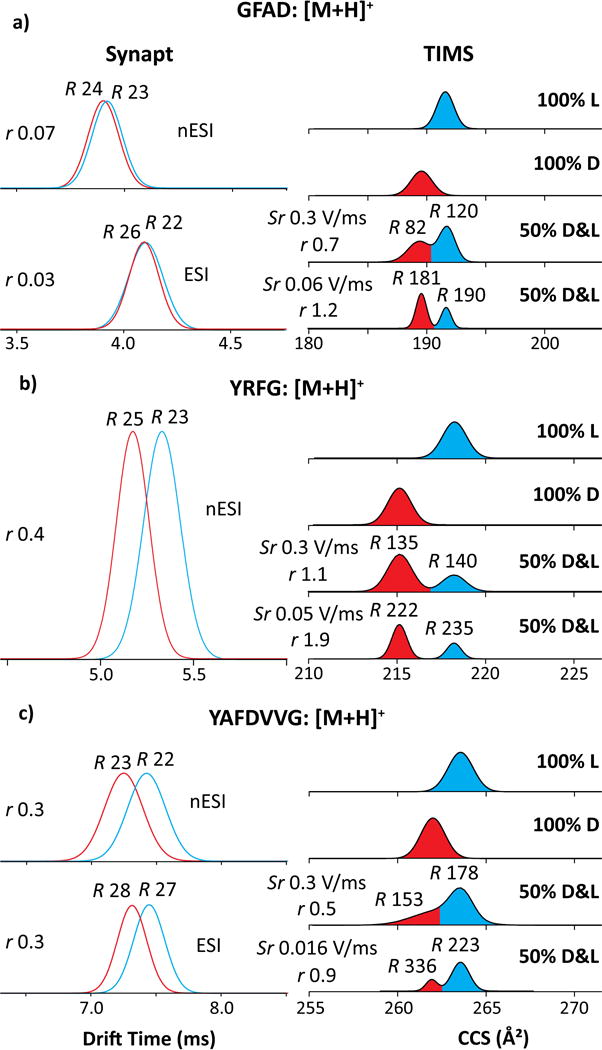

The smallest peptides GFAD, YRFG, and YAFDVVG exhibit [M+H]+ ions that yield a single peak in IMS spectra (Figures 1 and S1). With Synapt, the expected apparent R of ~25 allows very little (if any) epimer resolution: the features coincide for GFAD (r < 0.1) and just slightly differ for YRFG (r = 0.4) and YAFDVVG (r = 0.3).33 The two TWIMS instruments with dissimilar sources yield identical outcomes, showing excellent interlab reproducibility and pointing to thermalized peptide conformations in the IMS cell. The separation power of TIMS is drastically higher at any reasonable Sr (Table S3). With fast scan rates [Sr = 0.3 V/ms], we achieved R of ~ 120 - 180 (on average, ~140) for well-resolved features. This delivers nearly baseline resolution for YRFG (r = 1.1) and partial separation for GFAD (r = 0.7) and YAFDVVG (r = 0.5). Slow scan rates [Sr = 0.016 – 0.06 V/ms] led to higher R ~ 180 - 340 (on average, ~230), providing (nearly) baseline resolution (r ~ 1 – 2) for all three pairs (Figure 1 and Table S1). Hence the resolution advantage of TIMS over Synapt is 5 - 10 fold, depending on the Sr utilized.

Figure 1.

IMS spectra using Synapt (left) and TIMS (right) for small protonated peptides (a) GFAD, (b) YRFG and (c) YAFDVVG. The epimers are colored in blue (L) and red (D). The TIMS spectra for mixtures employed different scan rates Sr as marked. The R and r values are given.

Full resolution of epimers permits accurate measurement of their relative (ΔΩr) and absolute (ΔΩ) mobility differences: 1.1% (2.1 Å2) for GFAD, 1.4% (3.0 Å2) for YRFG, and 0.6% (1.5 Å2) for YAFDVVG (Table S1). So TIMS can baseline-resolve the epimers with ~1.5% difference using fast scan rates and half that with slow scan rates. The D-epimer has lower Ω in all cases. This qualitatively matches the results with Synapt, but ΔΩr was significantly greater for GFAD than YAFDVVG with TIMS and conversely with Synapt. That must reflect a distinction between time-averaged peptide geometries in two separations, presumably due to the (i) unequal heating of ions by different rf fields in TIMS and Synapt cells,59,60 and/or (ii) conformational evolution of peptides during much longer separation in TIMS (~50 - 300 ms) vs. Synapt (~5 - 10 ms) - such transitions on the ~10 - 300 ms timescale have been noted in ion trap/IMS systems.61,62

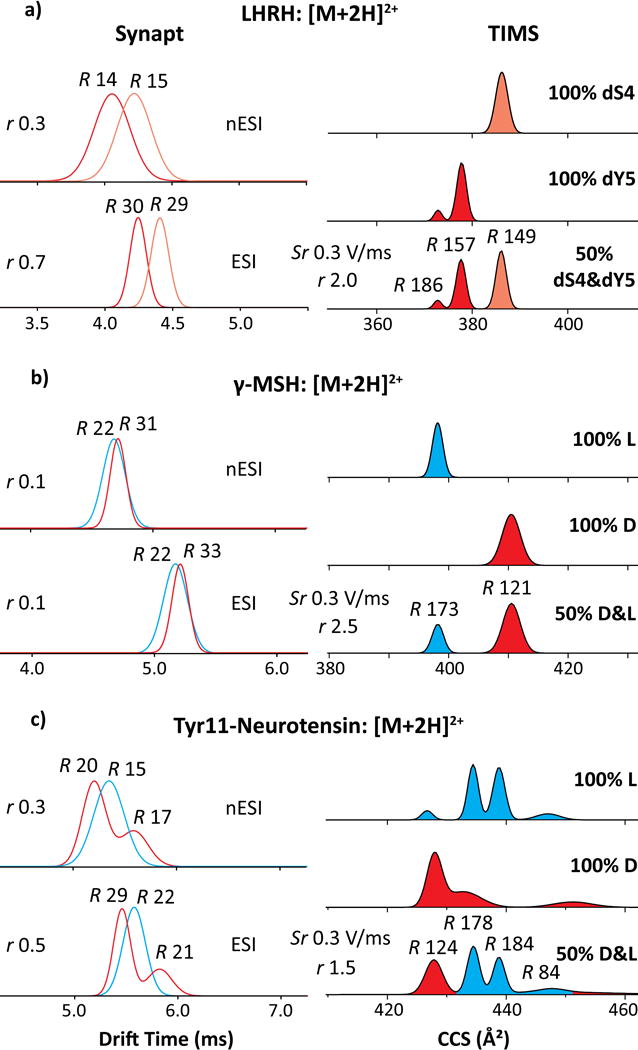

The outcomes for larger doubly protonated peptides LHRH, γ-MSH, somatostatin-14, and both neurotensins, are broadly similar (Figures 2 and S4). The resolving power of all IMS methods goes up for higher charge states in view of slower diffusion at equal mobility.59,63 Indeed, the R values slightly increase for the [M+2H]2+ ions (on average, to ~30 in Synapt and ~160 in TIMS with fast scan rates) while the relative advantage of TIMS remains at 5 - 6 times. The IMS spectra from two Synapt platforms stay consistent and show material differences between all epimers, but none suffices for baseline resolution. At best, r = 0.7 for LHRH allows clean filtering of each isomer near its peak apex. The separation for other pairs (incl. the important γ-melanocyte stimulating hormone-MSH)33 is much worse. With TIMS, baseline resolution (r = 1.5 – 2.5) is attained in all cases except somatostatin-14 already with the fast scan rate. While higher R helped, that is mostly due to greater ΔΩ compared to [M+H]+ ions [2.2% (8.5 Å2) for LHRH, 3.0% (12.3 Å2) for γ-MSH, 1.5% (6.5 Å2) for Tyr11-neurotensin, and 2.3% (10.3 Å2) for Trp11-neurotensin]: the lowest 1.5% exceeds the highest for [M+H]+ ions (Figure 1) where Sr = 0.3 V/(ms) provided baseline separation. The doubling of mean ΔΩr from 1.0% for [M+H]+ ions to 2.2% for [M+2H]2+ ions here probably reflects a greater diversity of folds accessible for larger peptides, which statistically expands the spread between epimer geometries. However, that diversity also tends to raise the number of populated conformers, which begin obstructing epimer resolution by taking up the separation space (Figures 2c and S4 d, e). This issue is well-known in non-linear IMS.64 For somatostatin-14, reducing Sr to 0.02 V/(ms) increased R to ~230 and resolution to near-baseline (r = 1.3) with ΔΩr = 0.7% (ΔΩ = 0.9 Å2, Figure S4c). This small shift may ensue from the conformational constraint by the disulfide link, although ΔΩr is yet smaller for WKYMVM without one (below). With γ-MSH, the Ω value is much greater for D than L epimer (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

IMS spectra using Synapt (left) and TIMS (right) for larger [M+2H]2+ peptides (a) LHRH, (b) γ-MSH, (c) Tyr11-neurotensin, for TIMS obtained using fast scan rates. The epimers are colored in blue (L) and red (D). The R and r values are given.

The γ-MSH, somatostatin-14, and neurotensins also exhibit [M+3H]3+ ions. Since the [M+2H]2+ ions of these epimers were baseline-separated in TIMS, no other conditions were explored (Figure S4). Under fast scan rates (Sr = 0.3 V/(ms) and R ~ 150), the Ω for D-epimer of γ-MSH is below that for L-epimer by 0.2% (0.9 Å2), meaning no resolution (r = 0.2). This order inversion compared to [M+2H]2+ ions matches that found with Synapt (Figure S6), but there ΔΩr of >2% provides r = 0.5 despite R of only ~30. For somatostatin-14, the main epimer peaks coincide, although L-epimer may be filtered out at its minor peak with Ω lower by 1.7% (7.9 Å2). For neurotensins, both epimers exhibit four - eight features occupying wide Ω ranges, and the shapes and widths of some indicate further merged conformers. This peak widening and multiplicity preclude good resolution. Here, lower Ω values broadly belong to the L-isomers. The spectra from Synapt overall agree with these findings (Figure S6).

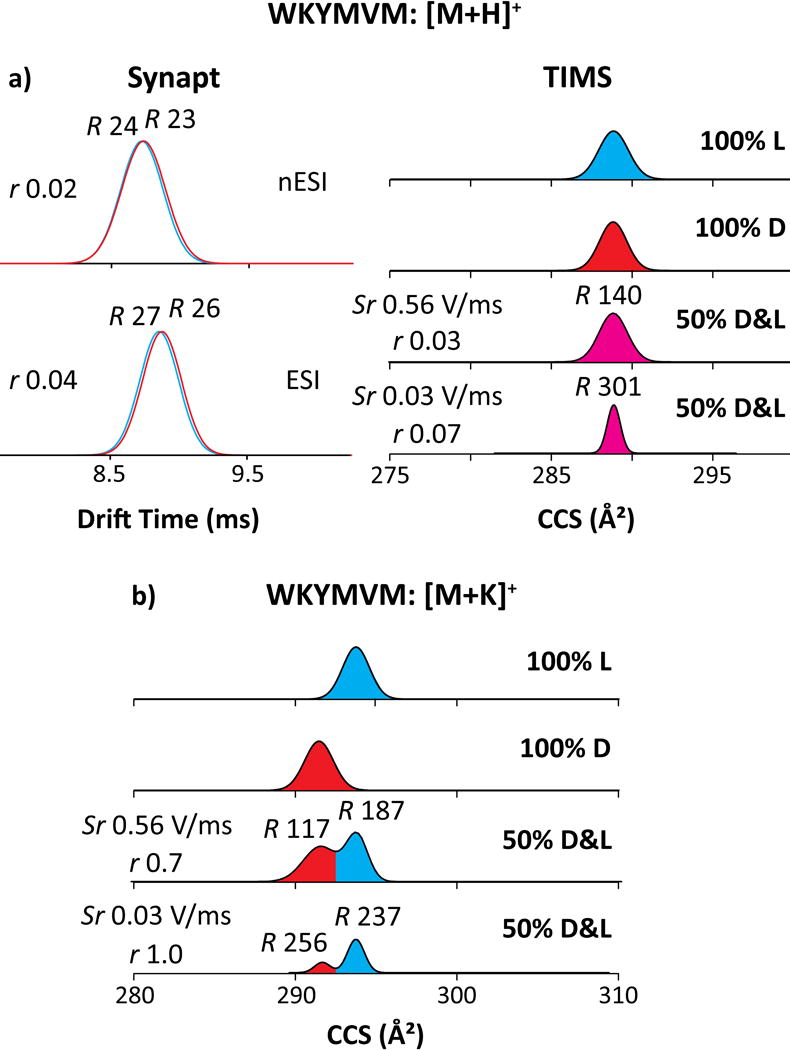

Enhancing Separations Using Metalation

With WKYMVM, the epimers for [M+H]+ and [M+2H]2+ ions coincide in both Synapt and TIMS, with r < 0.1 in TIMS even at R = 300 reached at slow scan rates (Figure 3a). In this sole case, we could not disentangle the protonated epimers. A possible solution is changing the cationization mode. For one, metalated biomolecules tend to differ in conformation from protonated analogs as the metal ion is multiply charged, binds at another site, and/or coordinates differently because of specific chemistry.65 If these deviations are unequal for two epimers, metalation can enhance their resolution.66,67 We have measured single K+ adducts generated by spiking the sample with K2CO3 at 70 μM (Figure 3b). While the peak widths barely change, potassiation increases Ω by 0.9% (2.6 Å2) for the D-epimer but 1.6% (4.8 Å2) for the L-epimer, enabling their complete resolution (r = 1.0) at slow scan rates (Table S1).

Figure 3.

IMS spectra using Synapt (left) and TIMS (right) for WKYMVM cationized by (a) protonated and (b) potassiated species. The epimers are colored in blue (L), red (D) and magenta (merged epimers). The TIMS spectra for mixtures employed different scan rates as marked. The R and r values are given.

Evaluating the Dynamic Range and Coupling to MS/MS

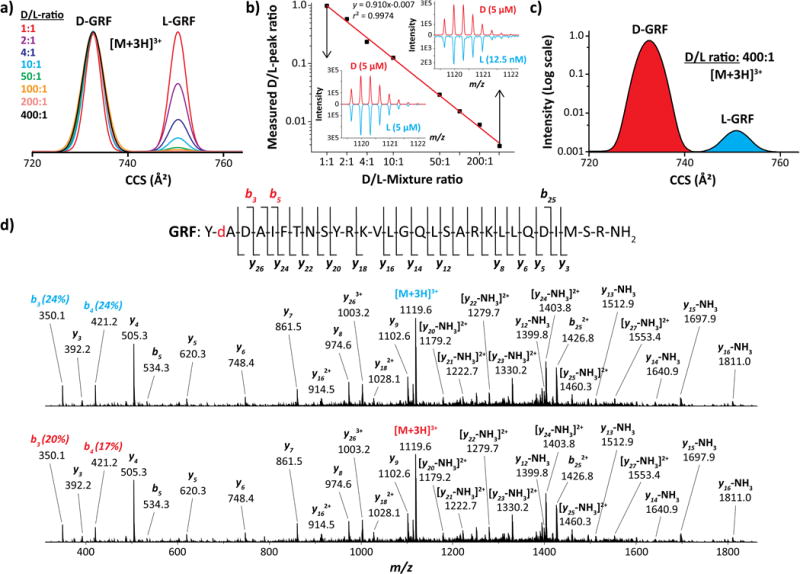

The largest peptide examined here (GRF) exhibits multiply protonated species ranging from [M+3H]3+ to [M+5H]5+ (Figure S5). In TIMS, the D/L-epimers are resolved baseline for the [M+3H]3+ ions [ΔΩr = 2.2% (16.2 Å2) and r = 2.4 with D-isomer at lower Ω], but coincide for [M+4H]4+ and [M+5H]5+ ions (r < 0.1).

Components can be more difficult to resolve in non-isomolar mixtures of large dynamic range as the sides of (ideally Gaussian) distributions for intense peaks can subsume adjacent weaker features, particularly when most of real samples comprise unequal epimer fractions. To gauge the capability of TIMS in this scenario, we have addressed mixtures with the D/L-ratio up to 400. Even at the maximum, the L-epimer was clearly resolved by IMS with s/n = 10 in the MS spectrum (Figure 4 a–c). Good linear quantification (r2 = 0.9974) extends down to fLOQ = 0.25% with substantially lower fLOD. These metrics are much superior to the best benchmarks from MS/MS (fLOD ~ 1 - 10%).

Figure 4.

Separation and CID (70 V) for the [M+3H]3+ ions of the D/L-epimers of GRF using TIMS: (a) IMS spectra for mixtures with various D/L-ratios obtained using Sr = 0.036 V/(ms), (b) Calibration curve with MS spectra for highest and lowest ratios, (c) IMS spectrum for the 400 ratio in logarithmic scale, (d) CID spectra at L- and D-peaks with masses and assignments for significant products (also mapped onto the peptide sequence)

The IMS-resolved epimers could be assigned based on tabulated Ω and/or fingerprint MS/MS spectra. The latter can also reduce fLOQ and fLOD by quantifying the isomer ratio at minor peaks partly covered by the wings of major peaks. In principle, an RDD analysis28 with fLOD = 2% after IMS separation with present fLOD < 0.25% would yield total fLOD < 50 ppm (assuming sufficient signal averaging). Our current platforms allow no EC/TD or RDD, but can perform CID that provides some epimer discrimination.

The CID spectra for D- and L-isomers are very close (Figure 4d). Both show the classic bn and yn fragments, with yn dominant since basic residues in GRF cluster toward the C-terminus. The only reproducible distinction between two spectra is a bit lower yield of b3 and b4 (the smallest observed fragments comprising the D/L-Ala2) for the D-epimer (Figure 4d). This may follow from slightly higher energy required to sever the backbone in that region for the D-epimer, in line with its lower Ω suggesting a tighter fold.68 While the MS/MS spectral difference happens to be marginal here, this example illustrates the advantages of online mobility-separated collision-induced dissociation (CID) followed by high-resolution mass spectrometry (TIMS-CID-MS) for epimer separation, sequencing, and relative quantification.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated rapid separation of D/L-peptide epimers using TIMS with resolving power of ~100 - 340 (typically ~ 200) on an nESI/time-of-flight MS platform. Nine out of ten tested sequences with 4 - 29 residues (including one with alternate D-residues) were completely resolved as protonated species based on mobility shifts of 0.6 - 3% with the mean of 1.7%. For larger peptides with multiple charge states, epimers merged in one state were resolved in another. This shows substantially orthogonal separations across states (previously noted for PTM localization variants in differential IMS).32,64 This behavior reflects strong dependence of peptide geometries on the protonation scheme.

For peptides exhibiting multiple charge states, the lowest ([M+2H]2+ or [M+3H]3+) always produced better epimer separation. For seven out of eight pairs involving D/L-substitution, the D-epimer had lower cross section by 0.6 - 2.3% (1.4% on average), affirming the concept that DAACPs are folded tighter than L-analogs.68 The exception is γ-MSH where CCS is much larger for the D-epimer, and with the greatest inter-epimer shift found here (3%); this suggests an unusual folding worthy of further exploration. The shifts for higher charge states ([M+3H]3+, [M+4H]4+or [M+5H]5+) are much smaller at 0.0 - 0.6% (0.2% on average) - generally too small to resolve with the present platform. This may reflect a diminished distinction between epimer geometries upon peptide unfolding driven by Coulomb repulsion (e.g., as has been shown for bradykinin).69 In previous studies (of singly and doubly protonated peptides), the Ω values for D-epimers were same as those for L-epimers or larger by up to 1.6%.31,70,71 By the intrinsic size parameter model for modified peptides, the epimers should have equal cross sections on average.72 Hence, at this point the epimer assignments require standards.

One pair co-eluting for protonated peptides was separated as K+ adducts, likely because of epimer-specific conformational changes. Different metal ions rearrange flexible biomolecules in distinct ways,65,66 which suggests trying diverse cations to maximize resolution.

Same protonated epimer pairs were analyzed employing the widely available Synapt G2 (ESI/traveling-wave IMS/ToF) systems. The results with nano-flow and high-flow sources were near identical. At the resolving power of ~20 – 30, the epimer spectra often differed significantly but not enough for full separation. The peak order near-perfectly correlated with that in TIMS, despite dissimilar ion sources and ~100× shorter separation. This observation suggests that we are probably sampling the same minima on the energy landscape rather than kinetic intermediates. Then the separations found here should easily transfer to other linear IMS platforms (e.g., the commercial drift tube IMS/ToF).73 Given the limited number of natural DAACPs, optimizing and cataloging their separations from L-epimers for broad use seems worthwhile.

Real tissues comprise epimers in (often grossly) unequal amounts, and characterizing the minor component(s) is more difficult than in 1:1 mixtures. We have shown TIMS to resolve epimers with linear quantification down to <0.25%, which is much better than any reported MS/MS method. Fragmentation patterns of resolved epimers can identify them and further lower the limits of detection and quantification, and here we illustrate collision-induced dissociation of mobility-resolved epimers. Since radical-driven MS/MS processes (e.g., ETD not currently enabled on the TIMS-TOF) provide much better epimer discrimination than collision-induced dissociation, we anticipate TIMS - ETD/ECD - MS platforms to advance the global DAACP analyses in biological systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work at FIU was supported by NIH (R00GM106414), NSF CAREER (CHE-1654274), and a Bruker Daltonics fellowship. The work at UW was funded by NIH (R01DK071801 and R56DK071801), and NSF (CHE-1710140 and CHE-1413596). The WSU authors are supported by NIH COBRE (P30 GM 110761) and NSF CAREER (CHE-1552640). Purchase of the Synapt instrument at KU was funded by NIH COBRE (P20 RR17708) and HRSA (C76HF16266).

Footnotes

Scheme of the TIMS cell, additional MS and IMS spectra of the investigated DAACPs, and tables of the measured separation parameters, resolution metrics and ramp slopes for all D/L-epimers ions. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Montecucchi PC, de Castiglione R, Piani S, Gozzini L, Erspamer V. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1981;17:275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1981.tb01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soyez D, Van Herp F, Rossier J, Le Caer JP, Tensen CP, Lafont R. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18295–18298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heck SD, Kelbaugh PR, Kelly ME, Thadeio PF, Saccomano NA, Stroh JG, Volkmann RA. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:10426–10436. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shikata Y, Watanabe T, Teramoto T, Inoue A, Kawakami Y, Nishizawa Y, Katayama K, Kuwada M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16719–16723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasuda A, Yasuda Y, Fujita T, Naya Y. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1994;95:387–398. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1994.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buczek O, Yoshikami D, Bulaj G, Jimenez EC, Olivera BM. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4247–4253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jimenéz EC, Olivera BM, Gray WR, Cruz LJ. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28002–28005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda-Kamatani Y, Kobayashi M, Yasuda A, Fujita T, Minakata H, Nomoto K, Nakamura M, Sakiyama F. Peptides. 1997;18:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(96)00343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobsen RB, Jimenez EC, De la Cruz RGC, Gray WR, Cruz LJ, Olivera BM. J Pept Res. 1999;54:93–99. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torres AM, Tsampazi C, Geraghty DP, Bansal PS, Alewood PF, Kuchel PW. Biochem J. 2005;391:215–220. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai L, Sheeley S, Sweedler JV. Bioanal Rev. 2009;1:7–24. doi: 10.1007/s12566-009-0001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreil G, Barra D, Simmaco M, Erspamer V, Erspamer GF, Negri L, Severini C, Corsi R, Melchiorri P. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;162:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mor A, Delfour A, Sagan S, Amiche M, Pradelles P, Rossier J, Nicolas P. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamatani Y, Minakata H, Kenny PT, Iwashita T, Watanabe K, Funase K, Sun XP, Yongsiri A, Kim KH, Novales-Li P. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;160:1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohta N, Kubota I, Takao T, Shimonishi Y, Yasuda-Kamatani Y, Minakata H, Nomoto K, Muneoka Y, Kobayashi M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178:486–493. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90133-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujisawa Y, Ikeda T, Nomoto K, Yasuda-Kamatani Y, Minakata H, Kenny PT, Kubota I, Muneoka Y. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1992;102:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(92)90049-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres AM, Menz I, Alewood PF, Bansal P, Lahnstein J, Gallagher CH, Kuchel PW. FEBS Lett. 2002;524:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broccardo M, Erspamer V, Falconieri Erspamer G, Improta G, Linari G, Melchiorri P, Montecucchi PC. Br J Pharmacol. 1981;73:625–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb16797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morishita F, Nakanishi Y, Kaku S, Furukawa Y, Ohta S, Hirata T, Ohtani M, Fujisawa Y, Muneoka Y, Matsushima O. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:354–358. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sela M, Zisman E. FASEB J. 1997;11:449–456. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.6.9194525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tugyi R, Uray K, Ivan D, Fellinger E, Perkins A, Hudecz F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:413–418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407677102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamamoto K, Kida Y, Zhang Y, Shimizu T, Kuwano K. Microbiol Immunol. 2002;46:741–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tao WA, Zhang D, Nikolaev EN, Cooks RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10598–10609. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai L, Romanova EV, Sweedler JV. Anal Chem. 2011;83:2794–2800. doi: 10.1021/ac200142m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serafin SV, Maranan R, Zhang K, Morton TH. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5480–5487. doi: 10.1021/ac050490j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams CM, Kjeldsen F, Zubarev RA, Budnik BA, Haselmann KF. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams CM, Zubarev RA. Anal Chem. 2005;77:4571–4580. doi: 10.1021/ac0503963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Y, Quebbemann NR, Julian RR. Anal Chem. 2012;84:6814–6820. doi: 10.1021/ac3013434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soyez D, Toullec JY, Montagne N, Ollivaux CJ. Chromatogr B. 2011;879:3102–3107. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y, Duan JP, Jiang XY, Chen HQ, Chen GN. J Sep Sci. 2005;28:2534–2539. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu C, Siems WF, Klasmeier J, Hill HH. Anal Chem. 2000;72:391–395. doi: 10.1021/ac990601c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ibrahim YM, Shvartsburg AA, Smith RD, Belov ME. Anal Chem. 2011;83:5617–5623. doi: 10.1021/ac200719n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia C, Lietz CB, Yu Q, Li L. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2972–2981. doi: 10.1021/ac4033824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang X, Jia C, Chen Z, Li L. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2017;28:110–118. doi: 10.1007/s13361-016-1523-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang H, Shi L, Zhuang X, Su R, Wan D, Song F, Li J, Liu S. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28079–28087. doi: 10.1038/srep28079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez-Lima FA, Kaplan DA, Suetering J, Park MA. Int J Ion Mobil Spectrom. 2011;14:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s12127-011-0067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez-Lima FA, Kaplan DA, Park MA. Rev Sci Instr. 2011;82:126106–126108. doi: 10.1063/1.3665933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams KJ, Montero D, Aga D, Fernandez-Lima F. Int J Ion Mobil Spectrom. 2016;19:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s12127-016-0198-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez DR, Debord JD, Ridgeway ME, Kaplan DA, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Analyst. 2014;139:1913–1921. doi: 10.1039/c3an02174b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benigni P, Thompson CJ, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Anal Chem. 2015;87:4321–4325. doi: 10.1021/ac504866v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benigni P, Fernandez-Lima F. Anal Chem. 2016;88:7404–7412. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benigni P, Sandoval K, Thompson CJ, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Gardinali P, Fernandez-Lima F. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:5978–5988. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b00508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castellanos A, Benigni P, Hernandez DR, DeBord JD, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima FA. Anal Meth. 2014;6:9328–9332. doi: 10.1039/C4AY01655F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schenk ER, Mendez V, Landrum JT, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2019–2024. doi: 10.1021/ac403153m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molano-Arevalo JC, Hernandez DR, Gonzalez WG, Miksovska J, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Anal Chem. 2014;86:10223–10230. doi: 10.1021/ac5023666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKenzie-Coe A, DeBord JD, Ridgeway M, Park M, Eiceman G, Fernandez-Lima F. Analyst. 2015;140:5692–5699. doi: 10.1039/c5an00527b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garabedian A, Butcher D, Lippens JL, Miksovska J, Chapagain PP, Fabris D, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016;18:26691–26702. doi: 10.1039/c6cp04418b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ridgeway ME, Silveira JA, Meier JE, Park MA. Analyst. 2015;140:6964–6972. doi: 10.1039/c5an00841g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meier F, Beck S, Grassl N, Lubeck M, Park MA, Raether O, Mann M. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:5378–5387. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silveira JA, Ridgeway ME, Park MA. Anal Chem. 2014;86:5624–5627. doi: 10.1021/ac501261h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pu Y, Ridgeway ME, Glaskin RS, Park MA, Costello CE, Lin C. Anal Chem. 2016;88:3440–3443. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu FC, Kirk SR, Bleiholder C. Analyst. 2016;141:3722–3730. doi: 10.1039/c5an02399h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schenk ER, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Leng F, Fernandez-Lima F. Anal Chem. 2014;86:1210–1214. doi: 10.1021/ac403386q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schenk ER, Almeida R, Miksovska J, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26:555–563. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-1067-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benigni P, Marin R, Molano-Arevalo JC, Garabedian A, Wolff JJ, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Int J Ion Mobil Spectrom. 2016;19:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s12127-016-0201-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDaniel EW, Mason EA. Mobility and diffusion of ions in gases. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; New York: New York: 1973. p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giles K, Williams JP, Campuzano I. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2011;25:1559–1566. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pringle SD, Giles K, Wildgoose JL, Williams JP, Slade SE, Thalassinos K, Bateman RH, Bowers MT, Scrivens JH. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2007;261:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shvartsburg AA, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9689–9699. doi: 10.1021/ac8016295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fernandez-Lima FA, Wei H, Gao YQ, Russell DH. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:8221–8234. doi: 10.1021/jp811150q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Badman ER, Hoaglund-Hyzer CS, Clemmer DE. Anal Chem. 2001;73:6000–6007. doi: 10.1021/ac010744a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myung S, Badman ER, Lee YJ, Clemmer DE. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:9976–9982. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watts P, Wilders A. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Proc. 1992;112:179–190. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shliaha PV, Baird MA, Nielsen MM, Gorshkov V, Bowman AP, Kaszycki JL, Jensen ON, Shvartsburg AA. Anal Chem. 2017;89:5461–5466. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dilger JM, Valentine SJ, Glover MS, Ewing MA, Clemmer DE. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2012;330:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flick TG, Campuzano ID, Bartberger MD. Anal Chem. 2015;87:3300–3307. doi: 10.1021/ac5043285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Domalain V, Tognetti V, Hubert-Roux M, Lange CM, Joubert L, Baudoux J, Rouden J, Afonso C. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2013;24:1437–1445. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodriguez-Granillo A, Annavarapu S, Zhang L, Koder RL, Nanda V. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18750–18759. doi: 10.1021/ja205609c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rodriquez CF, Orlova G, Guo Y, Li X, Siu CK, Hopkinson AC, Siu KW. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:7528–7537. doi: 10.1021/jp046015r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kemper PR, Dupuis NF, Bowers MT. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2009;287:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zheng X, Deng L, Baker ES, Ibrahim YM, Petyuk VA, Smith RD. Chem Commun. 2017;53:7913–7916. doi: 10.1039/c7cc03321d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaszycki JL, Shvartsburg AA. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2017;28:294–302. doi: 10.1007/s13361-016-1553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.May JC, Goodwin CR, Lareau NM, Leaptrot KL, Morris CB, Kurulugama RT, Mordehai A, Klein C, Barry W, Darland E, Overney G, Imatani K, Stafford GC, Fjeldsted JC, McLean JA. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2107–2116. doi: 10.1021/ac4038448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.