Abstract

Background:

Intermittent hypoxia (IH) is a key element of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) that can lead to disorders in the liver. In this study, IH was established in a rat model to examine its effects on the expression of hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) and CYP regulators, including nuclear receptors.

Methods:

Hematoxylin and eosin staining was conducted to analyze the general pathology of the liver of rats exposed to IH. The messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of inflammatory cytokines, CYPs, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and nuclear factors in the liver were measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Results:

We found inflammatory infiltrates in the liver of rats exposed to IH. The mRNA expression level of interleukin-1beta was increased in the liver of the IH-exposed rats (0.005 ± 0.001 vs. 0.038 ± 0.008, P = 0.042), whereas the mRNA expression level of Cyp1a2 was downregulated (0.022 ± 0.002 vs. 0.0050 ± 0.0002, P = 0.029). The hepatic level of transcription factor NF-κB was also reduced in the IH group relative to that in the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant and was parallel to the expression of the pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. However, the decreased expression of the glucocorticoid receptor upon IH treatment was statistically significant (0.056 ± 0.012 vs. 0.032 ± 0.005, P = 0.035).

Conclusions:

These results indicate a decrease in expression of hepatic CYPs and their regulator GR in rats exposed to IH. Therefore, this should be noted for patients on medication, especially those on drugs metabolized via the hepatic system, and close attention should be paid to the liver function of patients with OSA-associated IH.

Keywords: Cytochrome P450, Glucocorticoid Receptor, Inflammation, Intermittent Hypoxia, Nuclear Factor-κB

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disorder characterized by the repeated collapse of the upper airway in sleep, which leads to intermittent hypoxia (IH). Epidemiologic studies have proved this common condition to have a prevalence rate of 5–15%.[1] OSA-associated IH induces repetitive cycles of hypoxia and reoxygenation, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and systemic oxidative stress, which are associated with all manifestations of the metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia.[2] Recent evidence in humans and animals have indicated that IH also leads to liver injury.[3,4]

As one of the largest metabolic organs in the body, the liver is the center of nutrient synthesis, toxin resolution, and drug metabolism. The hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) plays a vital role in the bioactivation or inactivation of a wide range of xenobiotics.[5] Families 1–3 constitute almost half of the total CYPs in mammals and generally catalyze a diverse spectrum of reactions, including the metabolism of endogenous compounds, such as cholesterol, and exogenous compounds, such as drugs.[6] IH has been strongly suggested as an independent risk factor for the severity of liver fibrosis and fibroinflammation,[7] which can cause nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.[8] Oxidative stress and inflammation might be key factors contributing to the development of liver injury under hypoxemic conditions. The inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is activated in patients suffering from OSA, where its activity is correlated with the severity of the sleep condition.[9] Moreover, a hypoxic environment can lead to the expression of more proinflammatory factors, such as interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). However, the effects of these inflammatory and proinflammatory factors on IH-related liver injury have not been well examined. Besides the pathologic changes, IH may also have an effect on hepatic CYP activity, further influencing the metabolism of many drugs. A significant correlation has been found between hepatic CYP2E1 activity and nocturnal hypoxia.[10] We had previously reported that rats exposed to IH and cigarette smoke exhibited an increase of hepatic inflammatory cytokines, a reduction of CYPs, and a decrease of the nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and glucocorticoid receptor (GR).[11] Therefore, we hypothesized that IH-associated inflammation will independently lead to liver injury, which may further be exacerbated by another hepatic insult. To test this hypothesis, we exposed male Wistar rats to IH and examined the effects on inflammatory cytokine and CYP expression in the liver, and we also explored the possible mechanism behind these effects.

METHODS

Ethical approval

Rats were used under the strict protocol approved by the Animal Care Committee of Haihe Clinical College of Tianjin Medical University (Permit Number: 2010-0002).

Materials

Six-week-old male Wistar rats weighing 180 ± 20 g were purchased from the Laboratory Animals Center of the Institute of Radiation Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College (Tianjin, China). The gas oxygen concentration monitor was purchased from Hamilton Medical AG (Bonaduz, Switzerland). The flow and velocity meter was purchased from Instrument and Meter Plant (Yuyao, China). The blood-gas analyzer (model AVL 995) was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Air and/or nitrogen gas circulation was achieved by housing the animals in modified glass boxes, and a low-oxygen tank was reformed by using a large sealed box. The G-Storm Gradient polymerase chain reaction (PCR) thermal cycler was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA), and the LightCycler Real-Time PCR system was purchased from Roche. The RNA concentration meter was purchased from APG BIO Ltd., (Shanghai, China). TRIZOL Reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The TIANScript RT kit was purchased from TIANGEN Biotech Ltd., (Beijing, China). SYBR Green PCR core reagents were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories. Established programs were used to control the cycle index and cycle time of IH and intermittent normoxia (IN).

Groups and modeling

Thirty male Wistar rats were separated into two groups of 15 animals each according to oxygen exposure conditions. Both groups were bred normally for 8 weeks. On the 9th week, for 8 h during sleep time (9:00–17:00) every day, the rats in the control group were exposed to cycles of air (IN condition), whereas the rats in the IH group were exposed to cycles of nitrogen followed by air. Each cycle lasted for 120 s (30 cycles per hour), where that of IH involved 30 s of nitrogen followed by 90 s of air. The IH treatment was continued for 6 weeks.

Liver tissue sampling

At the end of the IH treatment, all rats were anesthetized and sacrificed. The abdominal cavity was opened, and the liver tissues were excised, rinsed in ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4), and then either stored at −80°C for gene expression analysis or fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for histologic analysis.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Lung and liver samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. After trimming, the tissues were embedded in paraffin using a tissue processor, and 3–4-μm-thick sections were cut. The sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) solution for visualization by microscopy.

Preparation of RNA from tissue samples

RNA was extracted from the liver tissues using TRIZOL Reagent. The extract yield and quality were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm with the MaestroNano Micro-Volume Spectrophotometer (Maestrogen, Inc., Las Vegas, NV, USA). The 260:280 absorbance ratio was between 1.8 and 2.0. The RNA was subsequently reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Messenger RNA (mRNA; 3 μg) was reverse transcribed with oligo (dT) primers for 1 h at 50°C, using the TIANScript RT kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNAs served as templates for the quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, which was performed using SYBR Green PCR core reagents. Specific gene primers were designed using Primer-Quest SM software available at http://www.idtdna.com/Scitools/Applications/PrimerQuest/ (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA, USA) and then produced commercially (BGI Tech, Shenzhen, China) [Table 1]. DNA amplifications were performed on a CFX96 Real-Time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at the following reaction conditions: an initial heating cycle of 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 25 s, primer annealing at 60°C for 25 s, and extension at 72°C for 20 s. Melt curves clarified the identity of amplicons, and the housekeeping gene Gapdh served as an internal control. The relative mRNA expression level of the target genes was calculated by the comparative Ct (threshold cycle) method, normalized to Gapdh mRNA in the same sample. Specific ΔCt was calculated as follows: ΔCt = (CtGAPDH) − (Cttarget); relative expression was defined as 2−ΔCt.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for gene amplification

| Gene | Probe | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-TCCCTGAACTCAACTGTGAAATA-3’ 5’-GGCTTGGAAGCAATCCTTAATC-3’ |

| IL-6 | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-GAAGTTAGAGTCACAGAAGGAGTG-3’ 5’-GTTTGCCGAGTAGACCTCATAG-3’ |

| TNF-α | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-ACCTTATCTACTCCCAGGTTCT-3’ 5’-GGCTGACTTTCTCCTGGTATG-3’ |

| PXR | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-GAAGATCATGGCTGTCCTCAC-3’ 5’-CGTCCGTGCTGCTGAATAA-3’ |

| CAR | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-GAGACCATGACCAGTGAAGAAG-3’ 5’-AGTCAGGGCATGGAAATGATAG-3’ |

| GR | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-CAGCAGTGAAATGGGCAAAG-3’ 5’-GGGCAAATGCCATGAGAAAC-3’ |

| Cyp1a2 | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-GACAAGACCCTGAGTGAGAAG-3’ 5’-GAGGATGGCTAAGAAGAGGAAG-3’ |

| Cyp2c9 | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-CCCAAGGGCACAACCATATTA-3’ 5’-CTTTCTGGATGAAGGTGGCA-3’ |

| Cyp2c19 | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-CCCAAGGGCACAACCATATTA-3’ 5’-TTTGACCCTCGTCACTTTCTG-3’ |

| Cyp2d4 | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-CCTTTCAGCCCTAACACTCTAC-3’ 5’-ATGAAGCGTGGGTCATTGT-3’ |

| Cyp3a2 | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-GGAAACCCGTCTGGATTCTAAG-3’ 5’-GAAGTGTCTCATAAAGCCCTGT-3’ |

| Gapdh | Forward primer Reverse primer |

5’-ACTCCCATTCTTCCACCTTTG-3’ 5’-AATATGGCTACAGCAACAGGG-3’ |

TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL: Interleukin; PXR: Pregnane X receptor; CAR: Constitutive androstane receptor; GR: Glucocorticoid receptor; CYP: Cytochrome P450.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the statistical significance of differences among the groups, and Student's t-test was implemented to verify the statistical significance between two arbitrary groups. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of intermittent hypoxia on the expression of inflammatory cytokines in the liver

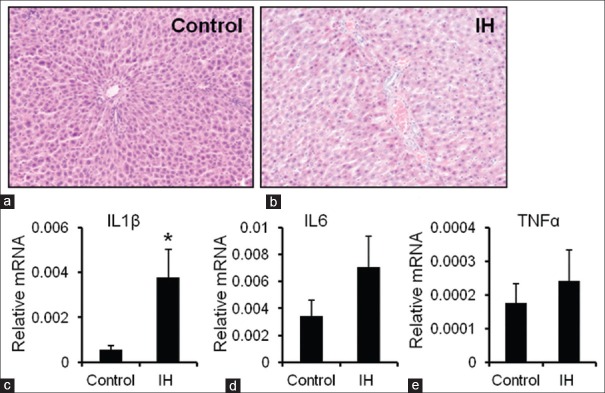

In the IH group, the blood-gas assay results revealed that the minimum oxygen saturation (SaO2) level was 0.863 ± 0.017, and the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) was 50.00 ± 2.64 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa; data not shown). The SaO2 and PaO2 periodically returned from below-normal to normal levels (data not shown). These findings indicated that the IH model was successfully established in the rat. The hepatic lesions and biochemical data from the two rat groups were analyzed. After IH exposure for 14 weeks, H and E-stained tissue sections of the liver were obtained and analyzed, and the mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines were measured as liver injury markers. In the IH group, there were inflammatory cell infiltrates in the portal area, and steatosis of hepatocytes, and the lightly stained cytoplasm of liver cells implied a loose cytoplasm [Figure 1a and 1b]. The hepatic mRNA expression level of IL-1β in the IH group was significantly higher than that in the control group (0.005 ± 0.001 vs. 0.038 ± 0.008, P = 0.042) [Figure 1c]. However, TNF-α and IL-6 in the IH group were similar to those in the control group [Figure 1d and 1e]. The above-mentioned findings indicated that hepatic lesions and early-phase inflammation had occurred in the IH group.

Figure 1.

Effect of IH on the expression of inflammatory cytokines in the liver (H and E, original magnification, ×100). (a and b) H and E staining of liver tissues harvested from the control and IH groups. (c-e) The mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were determined in the control and IH groups by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, using Gapdh as the housekeeping gene. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group. IH: Intermittent hypoxia; mRNA: messenger RNA; IL-1β: Interleukin-1beta; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

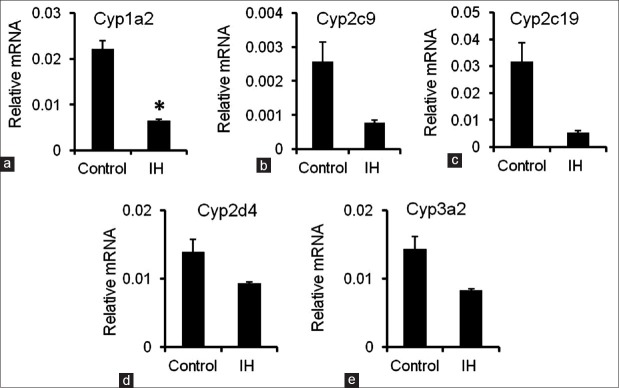

Messenger RNA expression levels of cytochrome P450 in the liver

The mRNA expression levels of various CYP molecular species in the liver were also assessed in the rats of the two groups. The mRNA expression level of Cyp1a2 was significantly higher in the IH-exposed rats than in the control rats (0.022 ± 0.002 vs. 0.0050 ± 0.0002, P = 0.029) [Figure 2a]. Moreover, a trend of decreasing hepatic Cyp2c9, Cyp2c19, Cyp2d4, and Cyp3a2 levels was observed in the IH group [Figure 2b–2e]. These findings were consistent with the finding in previous studies that inflammation may induce the downregulation of CYPs.[12,13]

Figure 2.

mRNA expression levels of CYPs in the liver. (a-e) The mRNA expression levels of Cyp1a2, Cyp2c9, Cyp2c19, Cyp2d4, and Cyp3a2 were measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Gapdh was used as the housekeeping gene. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group. IH: Intermittent hypoxia; mRNA: messenger RNA; CYPs: Cytochrome P450.

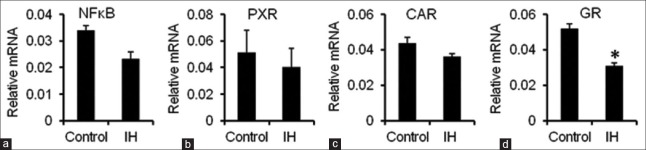

Messenger RNA expression level of nuclear factor-κB in the liver

Contrary to the enhanced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB was reduced in the liver of IH-exposed rats, but the difference relative to the control was not statistically significant [Figure 3a].

Figure 3.

mRNA expression levels of NF-κB, PXR, CAR, and GR in the liver. (a-d) The mRNA expression levels of NF-κB, PXR, CAR, and GR were measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Gapdh was used as the housekeeping gene. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group. IH: Intermittent hypoxia; mRNA: Messenger RNA; PXR: Pregnane X receptor; CAR: Constitutive androstane receptor; GR: Glucocorticoid receptor.

Messenger RNA expression levels of pregnane X receptor, constitutive androstane receptor, and glucocorticoid receptor in the liver

Cyp3a expression has been shown to be regulated by nuclear receptors, including PXR and CAR,[14,15,16] where with a decrease in nuclear translocation of these receptors, the expression of Cyp3a also declined. In addition, the synthesis and nuclear translocation of these receptors correlated negatively with NF-κB nuclear translocation.[17,18] In our experiment, we found that the hepatic mRNA expression levels of PXR and CAR remained unchanged in the IH group compared with that in the control group [Figure 3b and 3c]. However, GR expression was obviously diminished in the IH group (0.056 ± 0.012 vs. 0.032 ± 0.005, P = 0.035) [Figure 3d]. These results demonstrated that the reduced hepatic expression of CYPs observed in the IH-exposed rats may be attributed to the lowered synthesis and nuclear translocation of GR.

DISCUSSION

OSA is a common sleep disorder in which complete or partial airway obstruction occurs and is caused by pharyngeal collapse during sleep. The condition results in loud snoring or choking, frequent awakenings, disrupted sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness. The repeated pauses in breathing can lead to IH and increased ROS.[19] In 1997, Henrion et al.[20] first reported two cases of hepatitis combined with the hypoxia of OSA and associated the OSA syndrome with liver damage. In 2005, Tanné et al.[3] reported that the hepatic damage ratio was higher in patients with OSA, which was confirmed by liver biopsy, and included increased transaminase, steatohepatitis, liver cell necrosis, and liver fibrosis. Savransky et al.[4] researched chronic IH-associated liver disorders using animal experiments, revealing that the chronic IH of OSA could lead to liver damage. In our study, we adopted an animal model of IH and showed meaningful liver damage in the rats, which is consistent with the above studies.

IH caused by anoxia and reoxygenation can activate different inflammatory responses, inducing the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules, which lead to endothelial injury and dysfunction.[21] It is considered that the inflammatory responses are associated with OSA-related extrapulmonary complications.[22] Hence, determination of the important proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) of the liver can reflect the state of inflammation damage to a certain extent. In the IH group of our study, the hepatic mRNA level of IL-1β was higher than that in the control group. IL-1β may be the key factor promoting the inflammation. In contrast, another study did not find statistically significant differences in the serum levels of IL-1β between OSA patients and a control group,[23] and considered that IL-1β had no close relationship with OSA and its complications. Therefore, more animal and human studies are needed to determine the exact relationship between this proinflammatory cytokine and OSA.

In animal studies, it has been found that IH-induced liver damage affects the rate of drug metabolism, such as that of theophylline, which is widely used for treating respiratory system diseases.[24] In humans, the CYP1, CYP2, and CYP3 families are involved in hepatic drug metabolism. Among these family members, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C8, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 are expressed abundantly in the liver.[25] In fact, CYP levels influence the liver capability of drug metabolism to a large extent. Moreover, it was reported that CYP expression is regulated by the hypoxic state, as it was found that the expression of CYP2J2 was downregulated in HepG2 cells after 48 h of hypoxic exposure.[26] In animal experiments, CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 protein expression was decreased in the liver after 24 h of hypoxic exposure, whereas expression of the CYP3A6 protein was increased.[18] Although the effects of hypoxemia on the expression of CYPs depend on the cell type, IH obviously causes a general decrease in the expression levels in the liver,[24] which is consistent with our findings.

In this study, Cyp1a2 mRNA expression decreased in the IH group. This implies that the IH caused by OSA can damage liver metabolism. Such decline of hepatic metabolic capability would translate into a reduction of drug clearance and removal in the serum. When the liver is unable to metabolize the drug, the chemical will accumulate and create excessive toxic effects in the organ, thereby increasing the liver damage. As the center of the body's metabolic activity, liver function damage translates into decreased metabolic function. Therefore, close attention must be paid to the liver function of patients on medication, especially those on drugs that are metabolized hepatically.

Although there is no clear explanation as to the exact mechanism of how IH influences CYP expression, it has been reported that inflammatory factors may have an influence on the transcription of CYPs.[18] As shown in our study, the increased expression of IL-1β may inhibit the transcription of CYPs and cause a decrease in their expression.

PXR and CAR regulate the drug-metabolizing enzymes, including the phase I metabolic enzymes CYP3A4, CYP7A1, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C18, and CYP2C19. PXR and CAR pathways can regulate the expression of CYP2C9,[27] and metabolic enzymes such as CYP2C18 and CYP2C19 mainly play increased roles. Our experiments showed that the mRNA expression level of GR was reduced in the IH group, which further explains the corresponding decreased expression of Cyp1a2, and possible Cyp2c9, Cyp2c19, and Cyp3a2 in the rat model.

In conclusion, the present study examined the effects of IH on the liver. We found that IH alters the expression of inflammatory cytokines and CYPs in the liver, which may contribute to the alteration of hepatic drug metabolism in patients with OSA. Therefore, it is important to pay close attention to the liver function of patients with OSA, especially if they are being medicated with drugs that are metabolized hepatically.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31471121, No. 81773394, and No. 81728001), the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (No. 17JCYBJC24700), and Key Projects of Health and Family Planning Commission of Tianjin (No. 16KG163 and No. 16KG164).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Qiang Shi

REFERENCES

- 1.Turcani P, Skrickova J, Pavlik T, Janousova E, Orban M. The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2015;159:422–8. doi: 10.5507/bp.2014.002. doi: 10.5507/bp.2014.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanchina ML, Welicky LM, Donat W, Lee D, Corrao W, Malhotra A. Impact of CPAP use and age on mortality in patients with combined COPD and obstructive sleep apnea: The overlap syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:767–72. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2916. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanné F, Gagnadoux F, Chazouillères O, Fleury B, Wendum D, Lasnier E, et al. Chronic liver injury during obstructive sleep apnea. Hepatology. 2005;41:1290–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.20725. doi: 10.1002/hep.20725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savransky V, Nanayakkara A, Vivero A, Li J, Bevans S, Smith PL, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia predisposes to liver injury. Hepatology. 2007;45:1007–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.21593. doi: 10.1002/hep.21593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forrester LM, Henderson CJ, Glancey MJ, Back DJ, Park BK, Ball SE, et al. Relative expression of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes in human liver and association with the metabolism of drugs and xenobiotics. Biochem J. 1992;281(Pt 2):359–68. doi: 10.1042/bj2810359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bièche I, Narjoz C, Asselah T, Vacher S, Marcellin P, Lidereau R, et al. Reverse transcriptase-PCR quantification of mRNA levels from cytochrome (CYP) 1, CYP2 and CYP3 families in 22 different human tissues. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:731–42. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32810f2e58. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32810f2e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Minville C, Tordjman J, Lévy P, Bouillot JL, Basdevant A, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia is a major trigger for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in morbid obese. J Hepatol. 2012;56:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.04.022. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minville C, Hilleret MN, Tamisier R, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Clement K, Trocme C, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nocturnal hypoxia, and endothelial function in patients with sleep apnea. Chest. 2014;145:525–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0938. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Htoo AK, Greenberg H, Tongia S, Chen G, Henderson T, Wilson D, et al. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB in obstructive sleep apnea: A pathway leading to systemic inflammation. Sleep Breath. 2006;10:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0046-6. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalasani N, Gorski JC, Asghar MS, Asghar A, Foresman B, Hall SD, et al. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 activity in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;37:544–50. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50095. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu H, Shao H, Wu Q, Sun X, Li L, Li K, et al. Altered gene expression of hepatic cytochrome P450 in a rat model of intermittent hypoxia with emphysema. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:881–6. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6642. doi: 10.3892/mmr. 2017.6642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slaviero KA, Clarke SJ, Rivory LP. Inflammatory response: An unrecognised source of variability in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cancer chemotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:224–32. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aitken AE, Richardson TA, Morgan ET. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:123–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141059. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pondugula SR, Dong H, Chen T. Phosphorylation and protein-protein interactions in PXR-mediated CYP3A repression. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:861–73. doi: 10.1517/17425250903012360. doi: 10.1517/17425250903012360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chai X, Zeng S, Xie W. Nuclear receptors PXR and CAR: Implications for drug metabolism regulation, pharmacogenomics and beyond. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:253–66. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.754010. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.754010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah P, Guo T, Moore DD, Ghose R. Role of constitutive androstane receptor in Toll-like receptor-mediated regulation of gene expression of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014;42:172–81. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.053850. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.053850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Assenat E, Gerbal-Chaloin S, Larrey D, Saric J, Fabre JM, Maurel P, et al. Interleukin 1beta inhibits CAR-induced expression of hepatic genes involved in drug and bilirubin clearance. Hepatology. 2004;40:951–60. doi: 10.1002/hep.20387. doi: 10.1002/hep.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streit M, Göggelmann C, Dehnert C, Burhenne J, Riedel KD, Menold E, et al. Cytochrome P450 enzyme-mediated drug metabolism at exposure to acute hypoxia (corresponding to an altitude of 4,500 m) Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0886-1. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0886-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henrion J, Colin L, Schapira M, Heller FR. Hypoxic hepatitis caused by severe hypoxemia from obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24:245–9. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199706000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahammam A. Obstructive sleep apnea: From simple upper airway obstruction to systemic inflammation. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.75770. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.75770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lurie A. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and procoagulant and thrombotic activity in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Adv Cardiol. 2011;46:43–66. doi: 10.1159/000325105. doi: 10.1159/000325105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tziakas DN, Chalikias GK, Antonoglou CO, Veletza S, Tentes IK, Kortsaris AX, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and circulating interleukin-10 levels in patients with stable and unstable coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2471–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.032. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen XY, Zeng YM, Zhang YX, Wang WY, Wu RH. Effect of chronic intermittent hypoxia on theophylline metabolism in mouse liver. Chin Med J. 2013;126:118–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138:103–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marden NY, Fiala-Beer E, Xiang SH, Murray M. Role of activator protein-1 in the down-regulation of the human CYP2J2 gene in hypoxia. Biochem J. 2003;373(Pt 3):669–80. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021903. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Ferguson SS, Negishi M, Goldstein JA. Induction of human CYP2C9 by rifampicin, hyperforin, and phenobarbital is mediated by the pregnane X receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:495–501. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.058818. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.058818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]