Abstract

Purpose:

The aim is to study the clinicodemographic profile and treatment outcome of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN).

Methods:

This was a retrospective observational study of 57 eyes (56 cases) with clinically diagnosed OSSN, presenting in our center over the past year.

Results:

The median age of presentation was 55 years with male:female ratio being 4.5:1. Systemic predisposing conditions were xeroderma pigmentosa (1) postkidney transplant immunosuppression (1), and human immunodeficiency virus infection (1). Patients with predisposing conditions had a younger median age of onset (33 years). The majority of tumors were nodular (61.4%), gelatinous (61.4%), and had limbal involvement (96%). On ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM), mean tumor height was 2.93 ± 1.02 mm, and intraocular extension was evident in seven eyes. OSSN with intraocular extension had a mean tumor height of 4.3 ± 1.32 mm. Nodal metastasis was seen in one case at presentation. As per American Joint Committee for Cancer Classification seventh edition staging-two cases were T1, one was T2, 46 were T3 and eight were T4. Treatment advised included conservative therapy for 39; wide local excision (4 mm margin clearance) with cryotherapy for seven; enucleation in four; and exenteration in four eyes. Overall, complete regression was achieved in 88% of cases during a mean follow-up of 13.5 ± 4.6 months. Recurrence was seen in three cases, which were treated with exenteration, radical neck dissection, and palliative chemo-radiotherapy, respectively.

Conclusion:

Although associated with old age, earlier onset of OSSN is seen in patients with systemic predisposing conditions. Thicker tumors in the setting of a previous surgery or immunocompromised status should be considered high-risk features for intraocular extension and should be evaluated on UBM.

Keywords: Demography, ocular surface squamous neoplasia

The term ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) refers to a spectrum of epithelial squamous malignancies, ranging from dysplasia to invasive squamous cell carcinoma.[1] OSSN has a reported worldwide incidence of 0.02–3.5 cases per 100,000 people.[2] The incidence increases with decreasing latitude, being higher in countries located close to the equator.[3] The average age of presentation is usually the sixth and seventh decades of life. However, in immunocompromised individuals, OSSN may occur at a younger age.[4,5]

Risk factors for developing OSSN include exposure to ultraviolet radiation, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, human papillomavirus infection,[6] heavy cigarette smoking,[7,8] male gender and age.[9] Several studies have reported a dramatic increase in the incidence of OSSN following the outbreak of HIV.[10,11]

The standard modality for treatment of OSSN has been wide surgical excision with “no-touch” technique[12] and adjunctive cryotherapy. However, due to high recurrence rates ranging from 5% to 66% after surgical excision,[13] nonsurgical management with topical chemotherapeutic agents (5-fluorouracil) and mitomycin C (MMC) or interferon-a 2b (IFNα2b) has become the preferred choice for management of OSSN.[14]

In the wake of changing trends in the incidence and management options for OSSN, there is little knowledge of the clinic-demographic profile and treatment outcome of these patients in the Indian scenario. Herein, we report the current clinicodemographic profile and treatment outcome of patients presenting with OSSN at a tertiary eye care center.

Methods

This was a retrospective study. The medical records of all patients presenting to our center and clinically diagnosed with OSSN between March 2015 and March 2016 were reviewed. Institutional ethical committee approval was obtained for the study.

Demographic and clinical history details of the patients were noted, which included– age at presentation, gender, laterality, occupation, socioeconomic status (using modified Kuppuswamy scale[15]), duration of symptoms, risk factors (history of ocular trauma or surgery, sunlight exposure, any predisposing conditions, genetically predisposed state), and previous treatment history. A history of prolonged sun exposure was determined by self-reported history and/or inferred from the occupation of the patient. Previous treatment history included details of the type of interventions (surgery/topical therapy) and number of recurrences. Details of histopathology reports were analyzed. Previous pterygium surgery was included in the treatment history for OSSN, in the absence of a histopathological validation of pterygium.

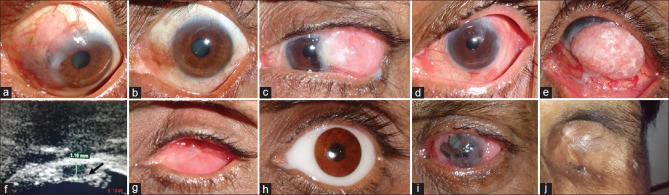

Clinical characteristics of the tumor were noted, which included location, extent, tissues involved (conjunctiva, cornea, eyelid, caruncle, sclera, intraocular, orbit), tumor multiplicity which was defined as the presence of two tumors separated by a distance of at least 5 mm, presence of feeder vessels, growth pattern (nodular/sessile), clinical type (pappilliform, gelatinous, fungating, ulcerative), presence of leukoplakia/pigmentation, tumor height as measured on ultrasound biomicroscopic (UBM) examination, clock hours of limbal involvement, maximal basal diameter, and nodal or systemic metastasis. Based on the number of clock hours of limbal involvement or maximum basal diameter, the tumor was classified as small (≤5 mm basal diameter or ≤3 clock hours of limbal involvement), large (6–15 mm in basal diameter or >3–6 clock hours of limbal involvement), or diffuse (more than 15 mm in basal diameter/forniceal/eyelid involvement or >6 clock hours of limbal involvement) [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs showing the clinical classification scheme of ocular surface squamous neoplasia based on the number of clock hours of limbal involvement or maximum basal diameter as (a) small, (b) large, and (c) diffuse

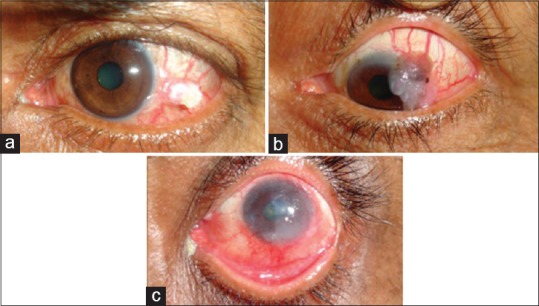

Intraocular involvement was noted based on the presence of cells in the anterior chamber, gonioscopy, dilated fundus examination, UBM [Fig. 2], and ocular ultrasonography in cases with media opacity. Imaging scans of the orbit were reviewed in cases with forniceal involvement to rule out any orbital extension. All the tumors were graded according to American Joint Committee for Cancer Classification (AJCC)-tumor, node, metastasis of conjunctival carcinoma (7th edition of AJCC[16]). Impression cytology reports were reviewed for all cases, and HIV status was noted. Treatment advised, treatment outcome, and follow up was noted for patients. At our center, we routinely perform impression cytology in all cases of ocular surface masses. The conservative management of OSSN is based on clinical impression alone. However, more aggressive surgical treatment like enucleation and exenteration is done only after obtaining a biopsy, which may not be needed if the impression cytology is positive.

Figure 2.

(a) Measurement of the height of the lesion using ultrasound biomicroscopy. (b) Intraocular extension in a case of ocular surface squamous neoplasia evident in the form of ciliary body thickening

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed following compilation of data using SPSS (version 11, New York, Purchased by Department of Biostatistics, AIIMS). Descriptive statistics were used for demographic characteristics and the data being presented as percentages, mean, and standard deviation.

Results

Clinical and demographic details

A total of 57 eyes of 56 patients were included in the study. The median age of presentation was 55 years (range: 10–80 years). The median age of onset of symptoms was 53 years. Twenty-seven percent patients (15/56) were younger than 50 years at presentation. There was a marked male preponderance with male:female ratio of 4.5:1. Eighty-nine percent (n = 50) of patients belonged to the upper lower and lower class on assessment of socioeconomic status using Modified Kuppuswamy scale.

Seventy percent of patients (39/56) were involved in the indoor occupation, and 30% (17/56) had an outdoor occupation. Of 56 patients, 34% (19/56) had prolonged history of sun exposure, 34% (19/56) had a history of smoking, 13% (7/56) had the previous history of ocular trauma or surgery unrelated to OSSN.

For 26 patients, the right eye was involved in the injury, and the left eye in 29 patients. Bilateral involvement was seen in one case. Previous treatment history was present in 46% (26/56). Among them, five cases had a history of use of topical MMC, eight cases had a history of pterygium excision (no histopathology reports available), and 13 cases had a history of previous excision biopsy for OSSN. Of 13 cases with a history of excision biopsy, histopathology reports were available only for eight (62%) patients and revealed well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in three cases, moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in two cases and poorly differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma in three cases. Associated ocular pathologies seen in the affected eye were cataract (n = 10), senile ptosis (n = 3), lagophthalmos (n = 1), and symblepharon due to a previous surgery (n = 1). Pterygium was noted in the fellow eye in eight cases. Systemic risk factors were found in three patients and included xeroderma pigmentosa (n = 1), HIV (n = 1), and renal transplantation (n = 1). OSSN was the presenting feature in the HIV patient. The median age of presentation in these three patients was 33 years (range: 10–51 years). Systemic associations were pulmonary tuberculosis (n = 1), hepatitis B (n = 1), and Berger's disease (n = 1). The patient with pulmonary tuberculosis had a bilateral involvement, with intraocular and orbital extension in the left eye. The patient with Berger's disease was contemporaneously diagnosed with OSSN and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

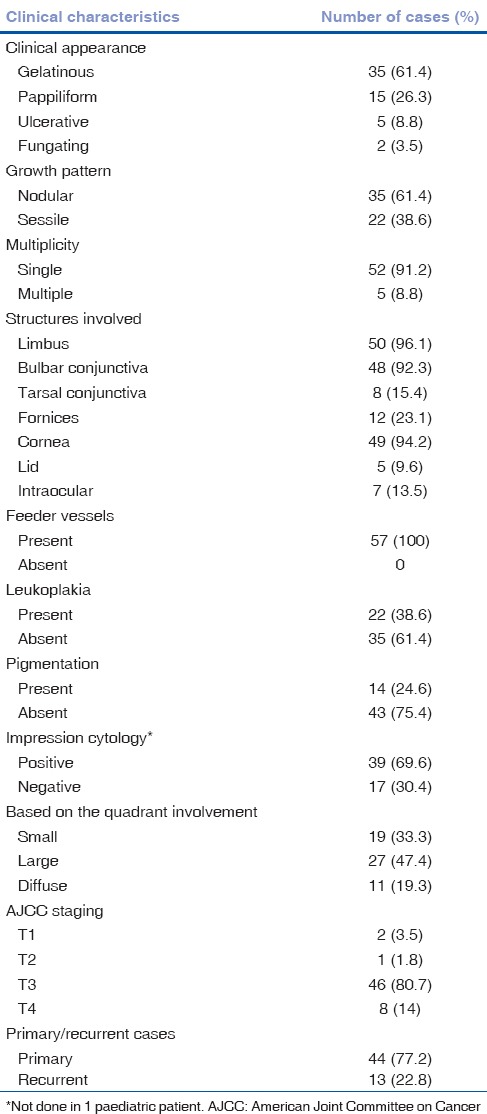

Clinical characteristics and tumor staging

Mean duration of symptoms was 1.03 ± 2.3 years. The presenting symptom was an ocular surface mass in 78% of cases and redness in 22% of cases. The tumor characteristics of 57 eyes is described in Table 1. Majority of tumors had a gelatinous appearance (61.4%) and a nodular growth pattern (61.4%). Leukoplakia was seen in 38.6% of cases and pigmentation in 24.6% of cases. The most common site of involvement was limbus (96.1%). Among 57 eyes, 3.5% of eyes (2/57) had AJCC grade T1, 1.8% of eyes (1/57) had T2, 80.7% (46/57) had T3, and 14% (8/57) of eyes had T4 grade OSSN.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 57 eyes of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (n=57)

Intraocular involvement was found in seven patients (AJCC T3 Grade-4 cases and T4 Grade-3 cases). Among these cases, the intraocular invasion was clinically evident as corneal melting and anterior segment invasion in one case. In the remaining six cases, it was evident on UBM. A history of previous surgery was present in 43% of cases with intraocular invasion (3/7) and 1 case was HIV-positive. One case with T4 tumor had a regional (preauricular) lymph node involvement at the presentation that was confirmed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. None of the cases had distant metastasis at presentation.

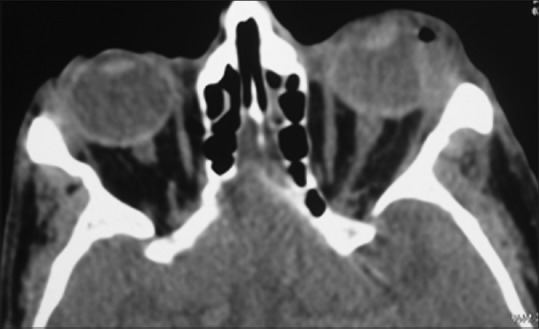

Investigations and imaging

Impression cytology and UBM examination were available for all except one paediatric patient. Impression cytology showed dysplasia in 70% (n = 39/56) cases. Mean tumor height on UBM was 2.93 ± 1.02 mm [Fig. 2a]. Intraocular involvement was evident as ciliary body/choroid thickening in three cases [Fig. 2b], anterior segment invasion with ciliary body thickening in two cases, and anterior segment invasion in one case. In the three cases where anterior segment invasion was detected on UBM, there were no clinical signs of anterior segment cells on slit lamp examination. However, gonioscopy could not be done due to large tumor overhanging the cornea in two cases and presence of corneal opacity in the third case. Orbital extension, confined to anterior orbit, was noted in eight cases on imaging [Fig. 3].

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (axial view) showing the anterior orbital involvement in ocular surface squamous neoplasia

Treatment and follow-up

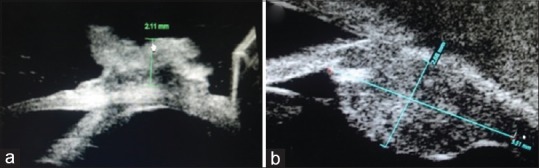

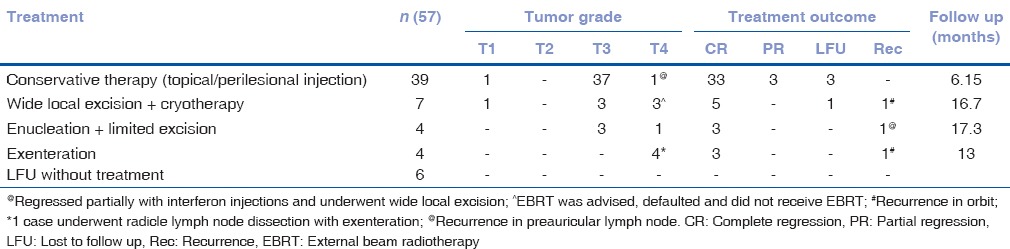

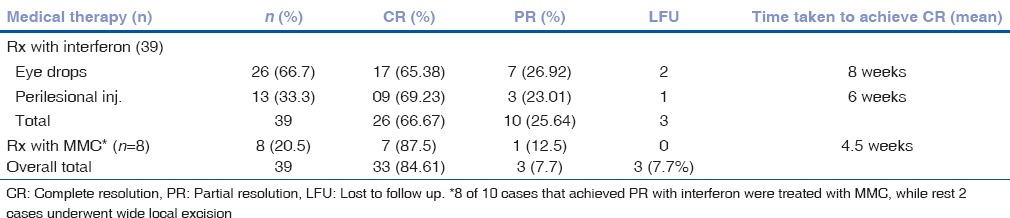

Out of 56 patients, six (six eyes) were lost to follow up after the initial evaluation. Treatment advised in the remaining cases included medical management (with topical MMC 0.04% QID or topical IFNα2b 1 MIU/ml QID or perilesional IFNα2b) in 39 eyes; wide surgical excision (4 mm margin clearance) with cryotherapy in seven cases (AJCC T1 - 1 eye, T3 - 2 eyes, AJCC T4 - 3 eyes); enucleation with limited excision with amniotic membrane transplantation with cryotherapy of conjunctival edges and adjunctive treatment (topical) in four cases (AJCC T3 - 3 eyes, AJCC T4 - 1 eye); exenteration in three cases (all AJCC T4); and exenteration with radicle lymph node dissection in one case (AJCC T4) [Fig. 4]. Adjuvant external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) was advised in five cases with T4 disease and with positive surgical margin on histopathology (wide local excision: Three cases, enucleation with excision: One case, exenteration: One case). The remaining cases had negative surgical margins for tumor cells on histopathology. Mean duration of follow-up was 13.3 ± 4.6 months. Treatment outcome and details of patients are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 88% (44/50) were free of disease at last follow-up. Medical therapy achieved complete regression in 84.61% (33/39) cases, all of which were disease-free at a mean follow up of 16.15 months (Range 7.5-28 months). Details of medical management are shown in Table 3. Thirty-nine eyes were treated with IFNα2b therapy. Of these, 66.67% (26/39) achieved complete resolution, and 25.64% (10/39) achieved partial resolution. Eight out of ten eyes, in which the tumor showed a partial response to IFNα2b, were subsequently treated with MMC 0.04% (one week on and one week off) for a maximum of four cycles. Of these, 87.5% (7/8) achieved complete resolution. In three eyes, where the tumor achieved partial resolution with medical management, wide local excision was performed.

Figure 4.

(a) Clinical picture showing diffuse gelatinous ocular surface squamous neoplasia left eye; (b) complete resolution posttreatment with topical interferon; (c) large nodular ocular surface squamous neoplasia left eye, (d) posttreatment photo after immunoreduction and wide local excision, (e) large papillary ocular surface squamous neoplasia right eye with (f) intraocular invasion into the ciliary body area (arrows) on ultrasound biomicroscopy; (g) healthy anophthalmic socket postenucletion and wide local excision; (h) same eye with artificial eye in place; (i) diffuse ocular surface squamous neoplasia with corneal melt right eye with orbital involvement; (j) postexenteration healthy socket lined by skin

Table 2.

Treatment outcome of ocular surface squamous neoplasia

Table 3.

Details of medical management

Overall, 6% (3/50) of patients developed recurrence, two in orbit with intracranial extension in one eye and one in draining lymph node. They were treated with exenteration, radicle neck dissection, and palliative chemo-radiotherapy, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Treatment outcome could not be compared between different tumor grades due to a skewed distribution of cases on AJCC classification. No statistically significant difference was noted in the clinical grades of tumor (small, large, and diffuse) using ANOVA with various parameters such as age (P = 0.21), duration of complaints (P = 0.16), clinical appearance (P = 0.17), growth pattern (P = 0.22), presence of leukoplakia (P = 0.56), presence of pigmentation (P = 0.43), location of tumor (P = 0.61), and duration of treatment (P = 0.36). In the conservative treatment group, the treatment outcome with medical management did not correlate with any tumor characteristic, including tumor dimension.

Discussion

OSSN is a common lesion in tropical countries. In a recent study from the developing world, extensive OSSN was reported to be the most common conjunctival lesion requiring exenteration.[17] The pathogenesis of OSSN is multifactorial. Risk factors for OSSN in our study were similar to those reported in the literature, including ultraviolet radiation, cigarette smoking, old age, male gender, ocular trauma/surgery, and immunosuppression.[6,7,8,9] In the current study, a majority of cases presented during the fifth to sixth decade with a marked male preponderance (82%). Similar findings have been reported in other studies.[18,19,20,21] However, studies from Africa report a younger age of onset and female predominance that has been linked with high HIV prevalence.[9,10,22] Younger age of presentation in HIV-positive individuals has also been reported from other developing countries.[23,24,25] In the current study, the mean age of presentation in immunocompromised patients was significantly lower (34 years). Furthermore, recent studies from the subcontinent have quoted a high incidence (38%) of HIV in young onset OSSN (<40). However, the findings of our study do not support the same.[26]

The majority of tumors in our study were nodular (61.4%) or gelatinous (61.4%) and had limbal involvement (96%). Chauhan et al.[20] and Dandala et al.[23] also reported nodular form as the most common morphological growth pattern.

In our cohort, according to AJCC classification, the majority of tumors (80.7%) belonged to T3 stage. There was only one eye with T2 stage OSSN. As the limbus is the most common site of origin for OSSN, larger lesions are likely to involve adjacent cornea. Hence, only a small percentage of tumors classify as T2 (larger than 5 mm and not involving cornea/other adjacent structures). The percentage of OSSN presenting in stage T2 reported in other studies varies from 0% to 7%.[27,28] Hence, we agree with other authors that the current staging system needs to be modified.

OSSN with intraocular involvement are clubbed in AJCC T3 grade along with those having extension into other adjacent structures such as cornea, sclera, plica, caruncle, lacrimal puncta, tarsal conjunctiva, and eyelid margin. We believe that there should be a separate categorization of tumors with intraocular involvement, as they require more aggressive surgical treatment (enucleation) compared to other T3 stage tumors. Twelve percent (7/57) of T3 tumors in this study had intraocular extension. On examination, 86% (6/7) of cases did not have any clinical features suggestive of intraocular involvement and were eventually picked up on UBM. However, their mean tumor height was greater (4.3 mm); there was a previous history of surgery in three cases, and one patient was HIV-positive. Therefore, thicker tumors in the setting of a previous surgery/biopsy or immunocompromised status should be considered as a high-risk feature for an intraocular extension. UBM should be done in all such cases to pick up the silent intraocular extension.

At our center, we have devised our own clinical classification scheme (small, large and diffuse) based on the clock hours of limbal involvement and maximal basal diameter, which is used to decide treatment for tumors without intraocular or orbital extension (T1, T2, and T3). We adhere to the following protocol for treatment: Surgical excision or topical/peri-lesional interferon therapy for small tumors, perilesional/topical interferon treatment for large tumors and topical interferon treatment for diffuse tumors. Interferons are used as the first-line conservative therapy. MMC is given if there is partial or no regression with interferon. This classification shows a more even distribution of OSSN cases as compared to AJCC classification where the distribution is skewed toward T3 stage [Table 1]. However, the treatment outcome of OSSN with medical management does not show any correlation with the size as reported by various studies in the literature.[27] Hence, a classification based on tumor size will not predict treatment outcome but can provide a guide for an appropriate treatment option for OSSN.

Sixty-seven percent (67%) of tumors in our study were large/diffuse. Seventy-five percent (six out of eight) of tumors with orbital extension were large and 67% (4 out of 6) of tumors with intraocular extension were diffuse. The mean duration of symptoms was longer in tumors with orbital and/or intraocular extension (1.89 ± 1.2 years). Mean tumor height of OSSN on UBM with orbital and intraocular involvement was 5.9 mm and 4.3 mm respectively, that was more than the overall mean height (2.93 mm). Hence, in our study majority of advanced tumors were larger and thicker than the mean cohort, as was also seen by Kao et al. in a retrospective study of 612 OSSN cases and have a longer duration of pathology.[21]

Metastasis is rare in OSSN with a reported incidence of 0%–16% in cases of squamous cell carcinoma.[29] Metastasis was seen in 6% (3/60) cases in the current study, all of which were in T4 tumors. Among these, metastasis to draining lymph node was seen in one case (2%) at presentation and in another (2%) on follow-up, and orbital recurrence with metastasis to the central nervous system was seen in one case.

In the present study, over all (44/50) 88% patients were disease free at a mean follow up of 13.3 months. Three cases (6%) showed recurrence at a mean follow up of around 5.67 months in our study. All three cases had T4 disease and positive surgical margins for tumor cells on histopathology. Two of these cases defaulted and did not receive EBRT, and the third patient who received EBRT had a recurrence in the draining lymph node. The recurrence rate of 10% to 36% during a follow-up of one to 2.5 years have been reported in OSSN.[18,20,30,31] The strength of our study is that the treatment outcome for all stages of the tumor has been analyzed. The limitation of our study is a short follow up.

Conclusion

To conclude, we present the clinicodemographic profile and treatment outcome of patients of all stages of OSSN from a developing country at a time when management of OSSN is undergoing a shift toward conservative management.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lee GA, Hirst LW. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:429–50. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J, Foster CS. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1997;37:73–85. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199703740-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gichuhi S, Sagoo MS, Weiss HA, Burton MJ. Epidemiology of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:1424–43. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porges Y, Groisman GM. Prevalence of HIV with conjunctival squamous cell neoplasia in an African provincial hospital. Cornea. 2003;22:1–4. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balint GA. Situation analysis of HIV/AIDS epidemic in sub-saharan Africa. East Afr Med J. 1998;75:684–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gichuhi S, Ohnuma S, Sagoo MS, Burton MJ. Pathophysiology of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Exp Eye Res. 2014;129:172–82. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Napora C, Cohen EJ, Genvert GI, Presson AC, Arentsen JJ, Eagle RC, et al. Factors associated with conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia: A case control study. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee GA, Hirst LW. Retrospective study of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1997;25:269–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1997.tb01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gichuhi S, Macharia E, Kabiru J, Zindamoyen AM, Rono H, Ollando E, et al. Clinical presentation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:1305–13. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ateenyi-Agaba C. Conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda. Lancet. 1995;345:695–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90870-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guech-Ongey M, Engels EA, Goedert JJ, Biggar RJ, Mbulaiteye SM. Elevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva among adults with AIDS in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2590–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shields JA, Shields CL, De Potter P. Surgical management of conjunctival tumors. The 1994 Lynn B. McMahan Lecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:808–15. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150810025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabin G, Levin S, Snibson G, Loughnan M, Taylor H. Late recurrences and the necessity for long-term follow-up in corneal and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:485–92. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nanji AA, Moon CS, Galor A, Sein J, Oellers P, Karp CL, et al. Surgical versus medical treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: A comparison of recurrences and complications. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:994–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra D, Singh HP. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale – A revision. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:273–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02725598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CA, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC ophthalmic oncology task force: Carcinoma of the conjunctiva. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 531–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali MJ, Pujari A, Dave TV, Kaliki S, Naik MN. Clinicopathological profile of orbital exenteration: 14 years of experience from a tertiary eye care center in South India. Int Ophthalmol. 2016;36:253–8. doi: 10.1007/s10792-015-0111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim BH, Kim MK, Wee WR, Oh JY. Clinical and pathological characteristics of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in an Asian population. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:2569–73. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shields CL, Demirci H, Karatza E, Shields JA. Clinical survey of 1643 melanocytic and nonmelanocytic conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1747–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chauhan S, Sen S, Sharma A, Tandon R, Kashyap S, Pushker N, et al. American joint committee on cancer staging and clinicopathological high-risk predictors of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: A study from a tertiary eye center in India. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1488–94. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0353-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao AA, Galor A, Karp CL, Abdelaziz A, Feuer WJ, Dubovy SR, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of ocular surface squamous neoplasms at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute: 2001 to 2010. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1773–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer MS, Batumba NH, Chirambo T, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Kayange P, Kalua K, et al. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia as the first apparent manifestation of HIV infection in malawi. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:422–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dandala PP, Malladi P, Kavitha Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia (OSSN): A retrospective study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:NC10–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/16207.6791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamal S, Kaliki S, Mishra DK, Batra J, Naik MN. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 200 patients: A case-control study of immunosuppression resulting from human immunodeficiency virus versus immunocompetency. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1688–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pradeep TG, Gangasagara SB, Subbaramaiah GB, Suresh MB, Gangashettappa N, Durgappa R, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection in patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in a tertiary center in Karnataka, South India. Cornea. 2012;31:1282–4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182479aed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaliki S, Kamal S, Fatima S. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia as the initial presenting sign of human immunodeficiency virus infection in 60 Asian Indian patients. Int Ophthalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Kim HJ, Al-Dahmash S, Shah SU, Lally SE, et al. Interferon for ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 81 cases: Outcomes based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Cornea. 2013;32:248–56. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182523f61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah SU, Kaliki S, Kim HJ, Lally SE, Shields JA, Shields CL, et al. Topical interferon alfa-2b for management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 23 cases: Outcomes based on American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:159–64. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKelvie PA, Daniell M, McNab A, Loughnan M, Santamaria JD. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: A series of 26 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:168–73. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramberg I, Heegaard S, Prause JU, Sjö NC, Toft PB. Squamous cell dysplasia and carcinoma of the conjunctiva. A nationwide, retrospective, epidemiological study of Danish patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:663–6. doi: 10.1111/aos.12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maudgil A, Patel T, Rundle P, Rennie IG, Mudhar HS. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: Analysis of 78 cases from a UK ocular oncology centre. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:1520–4. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]