Abstract

Objectives. To assess how integration of HIV surveillance and field services might influence surveillance data and linkage to care metrics.

Methods. We used HIV surveillance and field services data from King County, Washington, to assess potential impact of misclassification of prior diagnoses on numbers of new diagnoses. The relationship between partner services and linkage to care was evaluated with multivariable log-binomial regression models.

Results. Of the 2842 people who entered the King County HIV Surveillance System in 2010 to 2015, 52% were newly diagnosed, 41% had a confirmed prior diagnosis in another state, and 7% had an unconfirmed prior diagnosis. Twelve percent of those classified as newly diagnosed for purposes of national HIV surveillance self-reported a prior HIV diagnosis that was unconfirmed. Partner services recipients were more likely than nonrecipients to link to care within 30 days (adjusted risk ratio [RR] = 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03, 1.18) and 90 days (adjusted RR = 1.07; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.14) of diagnosis.

Conclusions. Integration of HIV surveillance, partner services, and care linkage efforts may improve the accuracy of HIV surveillance data and facilitate timely linkage to care.

The purpose of HIV surveillance in the United States is changing. The HIV surveillance system was initially designed to monitor the growth of the HIV epidemic and define the populations most affected by HIV/AIDS. Scientific evidence demonstrating that effective treatment prevents HIV transmission,1 that early treatment initiation improves clinical outcomes,2 and that a large number of people living with HIV are not engaged with care3 has led to fundamental changes in HIV prevention, with a new emphasis on case finding and treatment.

This emphasis has resulted in an increasing reliance on surveillance data to direct public health interventions, a strategy the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has called “data to care.”4 In this new paradigm, health department surveillance programs track the individuals who currently live within their jurisdictions and their current health status, rather than simply collecting information on case numbers and demographic characteristics, and then use those data to promote engagement with HIV care and viral suppression.

Surveillance data are collected and managed by local and state health departments, and these departments submit data without identifiers to the CDC. The CDC then uses nonname identifiers to attempt to de-duplicate cases. However, without a centralized repository of truly identifiable case surveillance data, cross-jurisdictional migration can result in duplicate case reporting.5 To varying extents, health department HIV programs investigate each case that newly enters their local surveillance system with the goals of (1) determining whether a newly reported case is a new diagnosis and characterizing the epidemiological features of that case, (2) ensuring that newly diagnosed individuals successfully link to medical care, and (3) providing partner services, interventions designed to deliver HIV testing, other prevention services (including preexposure prophylaxis referrals6), and treatment (if needed) to the sexual and needle-sharing partners of people newly diagnosed with HIV.

In many areas, these 3 goals are not well integrated. In some instances, each goal is addressed independently through separate surveillance activities, partner services, and links to care teams. Starting in 2001, the Public Health—Seattle & King County (PHSKC) HIV/STD (Sexually Transmitted Disease) Program began integrating surveillance and field services with the objective of more efficiently achieving each of the 3 goals.7 We have previously described the outcomes of partner services efforts in identifying new cases of HIV infection in King County.8,9 Here we describe our approach to managing newly reported cases and evaluate how integrating HIV surveillance with field services affects surveillance data quality and linkage to care and partner services indicators.

METHODS

HIV/AIDS reporting requirements in Washington State have evolved over time. Prior to 1999, only AIDS and symptomatic HIV cases were reportable by name. From 1999 to 2006, new HIV diagnoses were reportable, but PHSKC used a confidential code instead of names to identify cases. Since 2006, Washington State law has required that health care providers report by name all newly diagnosed HIV and AIDS patients and that laboratories report by name tests confirming HIV infections, HIV viral loads (detectable and undetectable), and CD4+T-lymphocyte test results of any value.10

The majority of cases are found initially through receipt of HIV-indicative laboratory test results. Most laboratories and health care facilities in Washington submit laboratory data electronically to the Washington State Department of Health. All data are matched bimonthly against the Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS), a Web-based platform that enables HIV surveillance data to be securely entered, stored, managed, and reported to the CDC. Laboratory data that match a previously existing case are retained in the Laboratory Tracking Database with a corresponding identifier and subsequently uploaded into eHARS and linked to existing records corresponding to the case. Laboratory results that do not match a known case are returned to local health jurisdictions (e.g., PHSKC) based on the geographic location of the ordering provider/facility for follow-up investigations.

The PHSKC field services unit is divided into teams assigned to specific infections and populations. The HIV partner services team is responsible for promoting HIV testing among the sexual and needle-sharing partners of newly diagnosed individuals and ensuring that individuals with newly diagnosed HIV are linked to HIV medical care. The field services team consists of 2 disease intervention specialists (1.4 full-time equivalent) and a surveillance coordinator. The disease intervention specialist with primary responsibility for the team’s work is funded through HIV surveillance and partner services grants and shares an office with the HIV surveillance coordinator in the PHSKC STD Clinic.

When a potentially new HIV case is identified, the team assesses whether the case was previously recorded in the Washington State eHARS. If the case does not already exist in eHARS, staff members review the individual’s medical records to collect contact and demographic information and clinical and epidemiological data. PHSKC has an agreement with the majority of the large health care organizations in King County that provides staff members with remote access to electronic medical records. If, in the course of a chart review or other investigation activities (including partner services interviews), staff members find evidence suggesting that an individual moved to Washington after being diagnosed in another state, they contact the surveillance team in the other state to determine the individual’s earliest HIV diagnosis date and residence at diagnosis, resolve missing or conflicting case data, and discuss the individual’s probable current residence.

The field services team attempts to provide partner services to all newly diagnosed HIV individuals and ensure linkage to care for all unsuppressed individuals with newly reported infections. The King County disease intervention specialists have not undergone any formal training in linkage to care, nor do they use a defined behavioral intervention to promote linkage to care. Investigations of people with newly reported HIV infections are not closed until care linkage is confirmed or until the disease intervention specialists, disease intervention specialist supervisor, and program medical officer determine that additional efforts to promote linkage would be futile; the disease intervention specialists maintain a list of inactive cases in which individuals never linked to care and periodically assess care engagement, incarceration, and out-of-jurisdiction migration.

We define confirmed linkages on the basis of laboratory tests ordered by medical providers and reported to the surveillance team, medical record reviews, or direct communications with health care facilities verifying that an HIV care visit occurred. Newly diagnosed individuals (without evidence of an existing HIV care provider) are invited to participate in the PHSKC One-on-One program, which allows individuals to be seen by a public health medical provider for a clinical assessment, initial laboratory evaluation, and counseling, usually within several days of diagnosis.11 Ensuring that all individuals link to care is a central goal of the One-on-One program.

The HIV program’s medical officer, surveillance epidemiologists, field services supervisor, and disease intervention specialists who provide HIV partner services meet monthly to discuss the status of all newly reported cases, facilitating exchange of information between field services, surveillance, and medical staff and allowing the team to develop strategies to assist people with HIV infection thought to be at high risk for treatment failure or HIV transmission and partners who are at high risk for HIV acquisition.

Data Sources

Several data sources were used in our analyses: eHARS, reported laboratory records, STD Clinic records, electronic medical records, and partner services databases. We used the following eHARS elements in our analysis: the year the individual entered the King County surveillance system, date and facility of the individual’s HIV diagnosis, date of birth, sex at birth, and risk transmission category. Date of specimen collection on reported laboratory records was assumed to be a marker for an HIV care visit and was used to evaluate linkage to care. One-on-One visit records were used to identify individuals who participated in the program.

PHSKC has used a series of locally developed databases to capture partner services interview data and to record investigative notes. In 2014, we started assigning a disposition to each newly reported person indicating whether the person was newly diagnosed or had confirmed or unconfirmed evidence of being diagnosed within or outside the United States. Prior to 2014, this information was captured less systematically in other fields.

Analysis

Our analysis included adults who entered the King County surveillance system between 2010 and 2015. For the purposes of national HIV surveillance, individuals with evidence of a prior diagnosis not confirmed by another jurisdiction’s HIV surveillance program are classified as newly diagnosed. In our analysis, we differentiated individuals with unconfirmed evidence of a prior diagnosis (obtained through self-report or medical record review) from individuals who appeared to truly have been newly diagnosed.

Our analysis involved multiple components. First, we evaluated relative proportions and temporal trends in the number of new diagnoses and imported cases entering the King County surveillance system between 2010 and 2015. Second, we compared the characteristics of cases reported as new diagnoses for the purposes of national HIV surveillance, cases newly diagnosed without any evidence of a prior diagnosis, and cases with unconfirmed evidence of a prior diagnosis; differences between the 2 latter groups were assessed via the χ2 test. All subsequent analyses were restricted to newly diagnosed cases without any evidence of a prior diagnosis.

Third, we evaluated the percentage of newly diagnosed individuals who participated in partner services and One-on-One programs. Finally, we determined the percentages (overall and by receipt of partner services) of newly diagnosed King County individuals who appeared to link to HIV care within 30, 60, 90, and 365 days of their diagnosis. We used multivariable log-binomial regression models to generate adjusted relative risk ratios (RRs) characterizing the relationship between receiving partner services and linking to care within 30, 60, 90, and 365 days of diagnosis after adjustment for year of diagnosis, type of diagnosing facility, age at diagnosis, sex at birth, race/ethnicity, nativity status, and risk transmission category. We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) in conducting all of our analyses.

RESULTS

Between 2010 and 2015, 2842 people newly entered the King County HIV Surveillance System. Of those individuals, 1670 (59%) were classified as being newly diagnosed with HIV for the purposes of national HIV surveillance; 196 of these 1670 individuals (12%) self-reported a prior HIV diagnosis or had information in their medical record indicating that they had previously been diagnosed with HIV. Of individuals classified as newly diagnosed for the purposes of national HIV surveillance, 87% were male, 55% were non-Hispanic White, 59% were between 20 and 40 years of age at the time of their diagnosis, 73% were known to be men who have sex with men, and 28% were known to have been born outside the United States (Table 1). People who were reported (for the purposes of national HIV surveillance) to be newly diagnosed but had evidence of a prior diagnosis were more likely to be female, non-Hispanic Black or Asian, foreign-born, and heterosexual than those who had no evidence of a prior diagnosis; they were also more likely to have had their “diagnosis” reported by an HIV care organization.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of People Entering the HIV Surveillance System: King County, WA, 2010–2015

| Characteristic | Reported New Diagnosis (n = 1670), No. (Column %) | No Evidence of Prior Diagnosis (n = 1474), No. (Column %) | Evidence of Prior Diagnosis (n = 196), No. (Row %) | P |

| Sex at birth | < .001 | |||

| Male | 1449 (87) | 1313 (89) | 136 (9) | |

| Female | 221 (13) | 161 (11) | 60 (27) | |

| Age at HIV diagnosis, y | .04 | |||

| 13–19 | 32 (2) | 28 (2) | 4 (13) | |

| 20–29 | 473 (28) | 439 (29) | 34 (7) | |

| 30–39 | 523 (31) | 456 (31) | 67 (13) | |

| 40–49 | 381 (23) | 327 (22) | 54 (14) | |

| 50–59 | 200 (12) | 175 (12) | 25 (13) | |

| ≥ 60 | 61 (4) | 49 (3) | 12 (20) | |

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 915 (55) | 861 (58) | 53 (6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 329 (20) | 240 (16) | 89 (27) | |

| Hispanic | 237 (14) | 222 (15) | 17 (7) | |

| Asian | 121 (7) | 85 (6) | 35 (29) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 12 (1) | 12 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Pacific Islander | 13 (1) | 12 (1) | 1 (8) | |

| Multiracial | 43 (3) | 42 (1) | 1 (2) | |

| Nativity | < .001 | |||

| US-born | 1098 (66) | 1048 (70) | 58 (5) | |

| Foreign-born | 465 (28) | 335 (23) | 131 (28) | |

| Unknown | 107 (6) | 91 (7) | 7 (7) | |

| Risk transmission category | < .001 | |||

| MSM | 1105 (66) | 1029 (70) | 77 (7) | |

| IDU | 57 (3) | 52 (4) | 5 (9) | |

| MSM/IDU | 118 (7) | 113 (8) | 5 (4) | |

| Heterosexual | 109 (7) | 82 (6) | 27 (25) | |

| Unknown | 281 (17) | 198 (13) | 82 (29) | |

| Diagnosing facility | < .001 | |||

| Outpatient | 678 (41) | 614 (41) | 63 (9) | |

| PHSKC STD Clinic | 351 (21) | 337 (23) | 17 (5) | |

| HIV/MSM specialty clinica | 309 (19) | 220 (15) | 88 (29) | |

| Inpatient | 140 (8) | 129 (9) | 11 (8) | |

| HIV community-based organization | 102 (6) | 102 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Emergency department/urgent care | 56 (3) | 49 (3) | 6 (11) | |

| Other | 34 (2) | 24 (2) | 9 (32) |

Note. IDU = injection drug users; MSM = men who have sex with men; PHSKC = Public Health—Seattle & King County; STD = sexually transmitted disease.

Refers to clinics that provide HIV care, including the Harborview Madison Clinic, as well as private practices known to explicitly serve the LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) community.

Nearly half (48%) of the individuals entering the King County HIV Surveillance System between 2010 and 2015 had been previously diagnosed outside of Washington. Of these “imported cases,” 86% had been diagnosed in another jurisdiction within the United States, 7% had been diagnosed outside the country, and 7% had an unknown location of diagnosis (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Over this 6-year period, records corresponding to HIV diagnoses made in all 50 states (and Puerto Rico) entered the King County HIV Surveillance System.

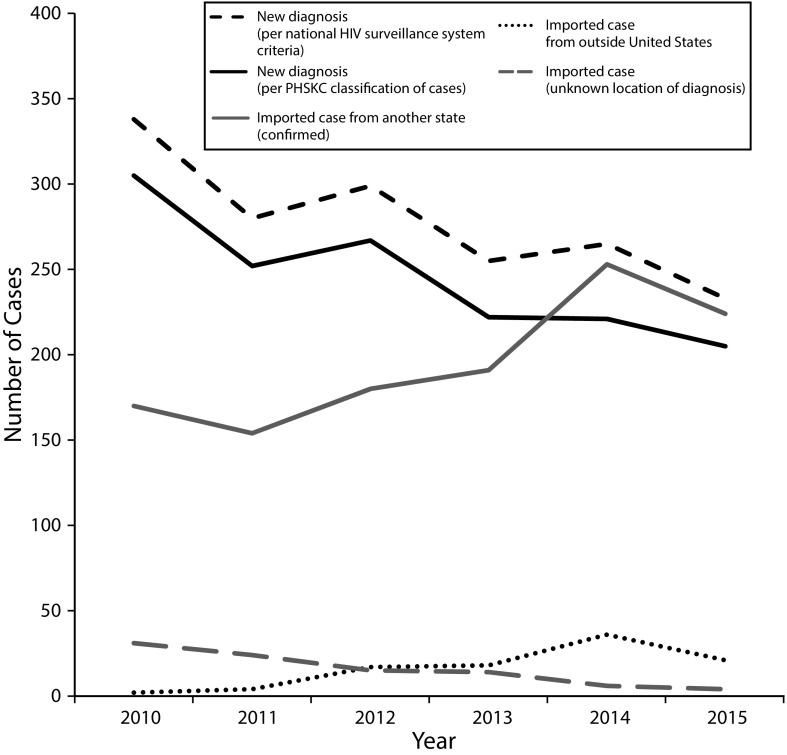

Figure 1 presents trends in the number of new diagnoses and imported cases in King County, separating new diagnoses into those reported as new for the purposes of national surveillance (regardless of local evidence of a previous diagnosis) and those that were new according to all available data sources (including unconfirmed self-reports). The number of new diagnoses declined from 2010 to 2015, concurrent with an increase in the number of imported cases. Coinciding with a programmatic shift toward more systematic documentation of information regarding prior diagnoses, the number of cases with an unknown location of a prior diagnosis declined and the number of cases with evidence of being diagnosed outside the United States increased.

FIGURE 1—

Number of People Newly Entering the King County, WA, HIV Surveillance System in 2010–2015, by Jurisdiction at Diagnosis

Note. The top line (black dashed line) represents the number of “new” diagnoses that were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All subsequent lines represent Public Health—Seattle & King County (PHSKC) classifications of cases according to locally available data. Information about prior diagnoses was more systematically collected after 2013.

All subsequent analyses excluded individuals with confirmed or unconfirmed evidence of a prior HIV diagnosis. A total of 387 newly diagnosed individuals (26%) participated in the One-on-One program at the STD Clinic, 56% of whom were seen in the program within 1 week of the date their blood was obtained for HIV testing. Disease intervention specialists attempted to contact nearly all (98%) newly diagnosed individuals for partner services, 84% were successfully contacted, and 80% were interviewed. The inability of the disease intervention specialists to locate individuals and individuals refusing partner services were the most common reasons for nonreceipt of services.

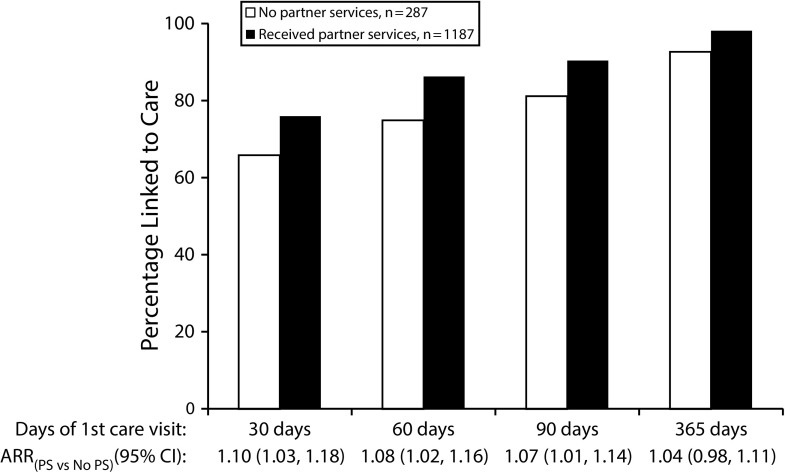

The percentages of newly diagnosed individuals linked to care within 30 days and 90 days of their diagnosis increased significantly between 2010 and 2015 (30 days: 62% to 82%, test-for-trend P < .001; 90 days: 85% to 93%, test-for-trend P = .003). Unadjusted analyses showed that the percentages of individuals linked to care within 30 and 90 days of diagnosis were higher among those who had received partner services than among those who had not (30 days: 76% vs 66%, P < .001; 90 days: 90% vs 81%, P < .001; Figure 2). Similarly, after control for demographic characteristics and other factors, linkage to care within 30 and 90 days of diagnosis was significantly greater among individuals receiving versus not receiving partner services (30 days: adjusted RR = 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03, 1.18; P = .004; 90 days: adjusted RR = 1.07; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.14; P = .014; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Time From Diagnosis to Linkage to HIV Care, by Partner Services Status, Among 1474 People Newly Diagnosed with HIV: King County, WA, 2010–2015

Note. ARR = adjusted risk ratio; CI = confidence interval; PS = partner services. Relative risk ratios were adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, year of diagnosis, facility of diagnosis, HIV transmission category, and nativity status.

None of the demographic characteristics were significantly associated with linkage to care within 30 days of diagnosis. However, year of diagnosis and being diagnosed at the STD Clinic, an HIV community-based organization, or an HIV care clinic were positively associated with individuals being linked to care within 30 days.

DISCUSSION

Over the past decade, PHSKC has increasingly integrated HIV surveillance investigations with HIV partner services and efforts to promote linkage to HIV medical care. Our findings suggest that this process, along with improvements in national data and surveillance processes, has allowed our health department to better estimate the true number of new HIV diagnoses in our jurisdiction. It has also allowed us to achieve nearly universal linkage to HIV care through a process that relies primarily on disease intervention specialists to coordinate, monitor, and ensure individuals’ entry into medical care.

Our findings suggest that integrating surveillance and field services improves HIV surveillance but also highlight the challenges facing local and national surveillance efforts. We observed an increase in the number of in-migrants with previously diagnosed HIV infection and a concurrent decline in new HIV diagnoses.

The growing number of in-migrants with prior diagnoses (“imported cases”) likely reflects a true increase in in-migration of people living with diagnosed HIV infection (PLWDH) into King County, an area with a growing population.12,13 However, it may also be a consequence of increased ascertainment of in-migration resulting from greater efforts by local surveillance and partner services staff to identify and confirm prior HIV diagnoses, along with improvements in national HIV surveillance data. As the number of PLWDH increases, newly diagnosed HIV individuals will represent a small and decreasing percentage of the PLWDH population.14 If the rate of annual interstate migration in the PLWDH population remains relatively constant, the ratio of imported cases to newly diagnosed cases would likely increase in many jurisdictions.

Migration has the potential to distort surveillance data, and ongoing changes in surveillance data quality complicate the interpretation of observed trends. Prevalent cases that move across state lines are at risk for being erroneously reported as new diagnoses. The CDC attempts to de-duplicate HIV cases through a process called the “Routine Interstate Duplicate Review” or “RIDR,” but this process probably misses an unknown proportion of duplicate case reports.5,15 We observed a decline in newly diagnosed cases alongside an increase in imported cases, which raises the possibility that ascertainment of in-migration has improved over time and that some unknown proportion of the observed decline in new diagnoses may be an artifact of changing surveillance processes and data quality. Recognition of this possibility should prompt caution when interpreting trends in new diagnoses. Additional efforts are needed to understand how changes in the surveillance system affect epidemiologic monitoring.

Migration of individuals from outside the United States poses a separate but related problem. For surveillance purposes, individuals with an HIV diagnosis predating their entry into the United States are generally classified as being newly diagnosed. As we have reported previously,16 classification of such cases as new has led to an almost 12% overestimate of new diagnoses and inflated estimates of the proportions of new diagnoses occurring among non-Hispanic Blacks and Asians, women, and heterosexuals.16 Although imported cases of HIV need to be included in surveillance data to provide an accurate estimate of prevalent cases, efforts to evaluate local transmission patterns would ideally exclude such cases as they are not avertable through local prevention activities.

From a practical perspective, we have identified a number of strategies that can improve a surveillance program’s ability to distinguish imported cases from new diagnoses. These strategies include establishing dedicated staffing, negotiating electronic access to medical record systems, establishing routine calls with jurisdictions that have large PLWDH populations to determine individuals’ place of diagnosis and residence, and integrating surveillance into HIV partner services. Ensuring that the relevant health departments are notified about cases found to be duplicates through RIDR will also help improve the quality of local surveillance data.

Our findings highlight the feasibility and potential value of integrating linkage to care into HIV partner services and public health clinical services. In many areas of the United States, people newly diagnosed with HIV must interact with multiple individuals from different agencies before seeing an HIV medical provider, a trying process that contributes to delays in linkage to care. PHSKC strives to streamline this process. The disease intervention specialists discuss both partner services and linkage to care topics when they meet with newly diagnosed individuals, and the One-on-One program enables such individuals to receive immediate clinical evaluations. These activities occur at the PHSKC STD Clinic, illustrating how clinics of this kind can facilitate an integrated approach to managing newly diagnosed HIV patients. Time to linkage to care improved after PHSKC integrated surveillance into partner services and began providing those services to all individuals with newly diagnosed HIV.

The association we observed between linkage to care and receipt of partner services is consistent with a prior report from New York City17 and suggests that partner services can improve linkage to care. That association, which was based on an analysis of observational program data, could reflect confounding rather than a true intervention effect. At present, the only linkage to care intervention that CDC regards as “evidenced based” is the Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study, a multisession18 behavioral intervention.19 Although our findings related to partner services do not rise to that level, we believe that partner services should be regarded as an “evidenced-informed” intervention. This intervention has helped King County achieve nearly universal linkage to care, and it is consistent with ongoing efforts in other areas to rapidly initiate antiretroviral therapy among people with newly diagnosed HIV.20

Limitations

There are limitations to the surveillance data included in our analyses and perhaps to the generalizability of our experience. Many of our analyses relied on reported date of HIV diagnosis, a field in eHARS that may align imperfectly with actual diagnosis date. Similarly, date of first reported CD4 or viral load result may imperfectly align with date of care initiation.21 For example, incomplete laboratory reporting and care visits without laboratory orders may cause the time from diagnosis to linkage to care to be overestimated, or, conversely, laboratory tests ordered through the One-on-One program may underestimate time to linkage to care. We cannot conclude definitively that partner services improved time to linkage to care, as our analysis of observational data may not have controlled for all sources of confounding. For example, there might be unobserved factors that would influence both the likelihood of receiving partner services and time to linkage to care. Also, some of the aspects of our approach in King County may be less feasible in areas with more limited resources or larger epidemics. Finally, 19% of the PLWDH population in King County is not suppressed despite high levels of care linkage, highlighting the need to address each step on the HIV care continuum.

Conclusions

We found that integrating surveillance and field staff into a team responsible for investigating new cases of HIV, providing partner services, and ensuring care linkage was feasible. This approach allowed staff members to collect new data elements (prior HIV diagnosis, nativity, timing of immigration) that improve our program’s understanding of the local epidemic and resulted in nearly universal linkage to HIV care. Our system of integration depends on an interdisciplinary team that uses diverse public health resources and operates within the STD Clinic to efficiently respond to new HIV cases.

The CDC is now encouraging state and local public health HIV/STD programs to better integrate their surveillance and prevention activities. Our experience supports such a direction, and some of the aspects of this experience may be helpful to other jurisdictions as they modify the interaction of surveillance and field services teams.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank and acknowledge the King County disease intervention specialists for their thorough case investigations, detailed recordkeeping, and commitment to HIV care and prevention.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The analyses described in this article were undertaken as a public health surveillance activity and therefore did not require institutional review board review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ et al. Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(47):1113–1117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden TR, Foti KE, Mermin J. Applying public health principles to the HIV epidemic—how are we doing? N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2281–2287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1513641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia Q, Braunstein SL, Wiewel EW, Eavey JJ, Shepard CW, Torian LV. Persons living with HIV in the United States: fewer than we thought. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(5):552–557. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W et al. Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(1):67–74. doi: 10.1086/430704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golden MR, Hopkins SG, Morris M, Holmes KK, Handsfield HH. Support among persons infected with HIV for routine health department contact for HIV partner notification. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32(2):196–202. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golden MR, Stekler J, Kent JB, Hughes JP, Wood RW. An evaluation of HIV partner counseling and referral services using new disposition codes. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(2):95–101. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818d3ddb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Kerani RP et al. Integrating HIV testing as an outcome of STD partner services for men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(5):208–214. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Public Health—Seattle & King County. Summary of Washington State HIV/AIDS reporting requirements and regulations. Available at: http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/communicable/hiv/epi/legal.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 11.Public Health—Seattle & King County. One on One: health services for people newly diagnosed with HIV. Available at: http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/communicable/hiv/resources/OneOnOne.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 12.King County. King County experiences strong population growth according to 2010 census results. Available at: http://www.kingcounty.gov/elected/executive/constantine/News/release/2011/February/24Census.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 13.State of Washington. 2015 population trends. Available at: http://www.ofm.wa.gov/pop/april1/poptrends.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHHSTP AtlasPlus. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 15.Ocampo JM, Smart JC, Allston A et al. Improving HIV surveillance data for public health action in Washington, DC: a novel multiorganizational data-sharing method. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(1):e3. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buskin S, Bennett A, Thibault C, Hood J, Kerani R, Golden R. Increases in the Proportion of HIV Among Foreign-Born Individuals in King County, Dates of HIV Diagnoses and the Impact on HIV Prevention. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: International AIDS Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bocour A, Renaud TC, Udeagu CC, Shepard CW. HIV partner services are associated with timely linkage to HIV medical care. AIDS. 2013;27(18):2961–2963. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005;19(4):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Complete listing of LRC best practices. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/lrc/completelist.html. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 20.Pilcher CD, Ospina-Norvell C, Dasgupta A et al. The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV viral load and treatment outcomes in a US public health setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):44–51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller SC, Yehia BR, Eberhart MG, Brady KA. Accuracy of definitions for linkage to care in persons living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(5):622–630. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182968e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]