Abstract

Introduction

Few data are available on the risk of SAEs in corticosteroid users in IgAN populations. We describe the prevalence and risk factors of corticosteroid-related SAEs in a Chinese cohort.

Methods

A total of 1034 IgAN patients were followed up in our renal center from 2003 to 2014. Prevalence of corticosteroid use and corticosteroid-related SAEs were noted. Logistic regression was used to search for risk factors of SAEs in corticosteroid users.

Results

Of the 369 patients with steroids therapy, 46 patients (12.5%) with 58 events suffered SAEs, whereas only 18 patients (2.7%) without corticosteroids suffered SAEs (OR: 5.45; 95% CI: 3.07–9.68; P < 0.001). SAEs included diabetes mellitus (n = 19, 5.1%), severe or fatal infection (n = 18, 4.9%), osteonecrosis of the femoral head or bone fracture (n = 6, 1.6%), cardiocerebral vascular disease (n = 4, 1.1%), cataract (n = 3, 0.8%), and gastrointestinal hemorrhage (n = 1, 0.3%). Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that advanced age (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07; P < 0.001) and hypertension (OR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01–1.06; P = 0.009) were risk factors for corticosteroid-related SAEs. Impaired kidney function (estimated GFR: OR: O.98; 95% CI: 0.96–0.99; P = 0.036) was a risk factor for severe infection. Accumulated dosages of corticosteroids were not identified as a risk factor of SAEs (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.91–1.30; P = 0.365).

Discussion

Corticosteroid use is associated with a high risk of SAEs in IgAN patients, especially those who are older, have hypertension, or impaired renal function. Current guidelines on corticosteroid regimens in IgAN should be reviewed with regard to safety.

Keywords: adverse events, corticosteroid, diabetes mellitus, IgA nephropathy

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is a glomerulonephritis mediated by immune complexes.1, 2, 3 IgAN is characterized by a highly variable course ranging from a totally benign incidental condition to rapidly progressive renal failure. However, most affected individuals develop chronic, slowly progressive renal injury, and many patients develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD).4

Each year, about 1% to 2% of all patients with IgAN develop ESRD from the time of diagnosis.5 About 15% to 20% of patients with apparent-onset IgAN develop ESRD within 10 years, and 30% to 40% within 20 years.6, 7, 8 Lowering of blood pressure as well as inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system remains the cornerstone of IgAN management. However, a substantial number of patients progress to ESRD even with this regimen (especially those with persistent proteinuria).

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines for the treatment of glomerulonephritis suggest that IgAN patients with a persistent proteinuria >1 g/d despite 3 to 6 months of optimized supportive care receive a 6-month course of corticosteroids.9 Several small clinical trials have suggested the potential renoprotective capabilities of corticosteroids in IgAN.10, 11, 12 One meta-analysis of 9 clinical trials suggested that 6-month corticosteroid therapy could reduce the prevalence of renal failure by 68%.13 However, these trials comprised a small number of patients, and adverse outcomes (AEs) were poorly reported (especially serious adverse events [SAEs] with clinical relevance). The recently completed Therapeutic Evaluation of Steroids in IgA Nephropathy Global (TESTING) study (262 participants) found that this renoprotective benefit came at a high cost with regard to SAEs (clinicaltrials.gov no. 01560052).14 Thus, the safety of corticosteroids in IgAN patients needs further evaluation. We evaluated the safety of corticosteroids and their risk factors in Chinese IgAN patients.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We reviewed the medical records of a large database of IgAN patients based at Peking University First Hospital. This cohort was established in 2003 and recruited patients mainly from northern China. A total of 1750 patients were registered from 2003 to 2014, and 1052 participants had follow-up data for ≥1 year or ≥3 times. The follow-up interval is generally scheduled at once a month thereafter for 3 months and then once every 3 to 6 months depending on patients’ status or treating physician. Among them, 387 patients were screened for corticosteroid use, and 18 patients were excluded because corticosteroids had been used for less than 3 months. Thus, 1034 patients formed the study cohort. Among them, 369 patients (35.7%) received a single corticosteroid (n = 150) or corticosteroids plus other immunosuppressive agents (n = 219) for ≥3 months (Supplementary Figure S1).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (approval number 2016[1142]; Beijing, China). All participants provided written informed consent for the IgAN cohort study.

Treatment Protocol

We usually considered steroid therapy in patients with persistent proteinuria >1 g/d after supportive therapy for >3 months, which was consistent with current KDIGO guidelines. Patients with a relative amount of crescents on a kidney biopsy or nephrotic syndrome (with serum albumin <30 g/l) might consider adding corticosteroids directly, which was determined by the treating physician. Other immunosuppressive agents were considered if patients presented with crescentic IgAN (cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil), persistent nephrotic syndrome (tacrolimus, cyclosporine A, or leflunomide), or progressive decline in renal function (cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil) after corticosteroid therapy. Initially, patients used prednisone or prednisolone (0.8–1 mg/kg/d; maximum, 60 mg/d) for 2 months, which was tapered to 5 mg every 2 weeks and stopped within 6 to 8 months. Another regimen of steroid pulse therapy was bolus injections (i.v.) of methylprednisolone (500 mg) for 3 days each at 1, 3, and 5 months, followed by prednisone (30 mg, p.o.) on alternate days for 6 months.12 The option of these 2 corticosteroid regimens depended on the physician and the patients’ intention. All medications used during the study period were recorded. Baseline characteristics including age, sex, blood pressure, hemoglobin, albumin, triglyceride, total cholesterol, proteinuria, serum creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate ([eGFR] according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology group [CKD-EPI] equation for Chinese15) were recorded.

Definition of SAEs

This was a retrospective study, and to minimize the selection bias, only patients with AEs necessitating hospitalization or treatment changes were considered as SAEs in the study. SAEs of interest were as follows: (i) all-cause mortality; (ii) severe infection necessitating hospitalization or fatal infection; (iii) osteonecrosis of the femoral head or bone fracture; (iv) gastrointestinal hemorrhage or gastrointestinal perforation; (v) new-onset diabetes mellitus (DM); (vi) new-onset cataract; (vii) major cardiocerebral vascular disease (including fatal/nonfatal myocardial infarction, fatal/nonfatal stroke, and heart failure). All adverse effects were recorded according to the clinical diagnoses. The relationship between these SAEs was adjudicated by 2 investigators (QC, JL) to ascertain whether the AE was related to the study drug.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean and SD or median with 25th and 75th centiles (as appropriate) for data distribution. Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies with percentages. Significance of differences between groups was dependent on distribution of data (normal or nonnormal) and so was determined from the independent sample t test or Mann-Whitney test as appropriate (for comparison of continuous scores between 2 groups) and the chi-squared test with continuity correction (for comparison of proportions between 2 groups). We analyzed relevant covariates that might associate with SAEs with multivariable logistic regression and reported odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values of Wald χ2 test. Covariates included in the analysis were age, sex, mean arterial pressure, proteinuria, eGFR, and corticosteroid or corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant therapy. To evaluate cumulative corticosteroid dosages on the risk of SAEs, we used the propensity-score matching patients with and without SAEs using the following 6 potential confounders: age, sex, mean arterial pressure, proteinuria, eGFR, and corticosteroids plus immunosuppressant. A multivariable logistic regression was used to determine the probability of SAEs using these key covariates, which was used for matching. Participants were matched using a greedy method with a 1:1 pair. The caliper size was set at 0.025 × SD of the logit of the propensity scores. The balance between 2 groups was checked by paired comparison tests of the baseline covariates. SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and STATA 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) were used for statistical analyses. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 1034 entered the study: 369 patients received corticosteroids or corticosteroids plus immunosuppressive agents. The mean blood pressure was 123 ± 16 mm Hg, proteinuria was 1.57 (0.82–3.03) g/24 h, and eGFR was 81 ± 31 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at the baseline. Patients taking corticosteroids had higher blood pressure (125 ± 16 vs. 122 ± 16 mm Hg, P = 0.006), had a greater level of proteinuria (3.0 [1.7–5.2] versus 1.1 [0.6–1.9] g/24 h, P < 0.001), and a lower eGFR (73 ± 33 vs. 86 ± 29 ml/min per 1.73 m2, P < 0.001). Among the corticosteroid group, 46 patients (12.5%) with 58 events had SAEs, whereas 18 (2.7%) in those not taking corticosteroids had a recorded SAE (Table 1). Overall, corticosteroid therapy or corticosteroid plus other immunosuppressant therapy were associated with a 5.45-fold risk of AEs (OR: 5.45; 95% CI: 3.07–9.68; P < 0.001; corticosteroids alone: OR: 4.13; 95% CI: 1.97–8.67; P < 0.001; corticosteroids plus immunosuppressant: OR: 6.34; 95% CI: 3.43–11.72; P < 0.001) (Table 2). Another 2 independent risk factors to affect SAEs in IgAN patients were age (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.03–1.07; P < 0.001) and blood pressure (OR: 1.03; 95% CI: 1.01–1.05; P = 0.010).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and follow-up information of the corticosteroid user group and corticosteroid nonuser group

| Baseline characteristic | Corticosteroid users (n = 369, 35.7%) |

Corticosteroid nonusers (n = 665, 64.3%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n [%])/female (n) | 203 (55.0)/166 | 317 (47.7)/348 | 0.024 |

| Age (yr) | 34 ± 13 | 35 ± 11 | 0.082 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 125 ± 16 | 122 ± 16 | 0.006 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 ± 12 | 78 ± 12 | 0.019 |

| Serum creatinine (mmol/l) | 106 (80–146) | 87 (70–114) | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h) | 3.0 (1.7–5.2) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 73 ± 33 | 86 ± 29 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (μmol/l) | 387 ± 102 | 361 ± 101 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 133 ± 20 | 134 ± 18 | 0.289 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 34 ± 8 | 39 ± 5 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 0.005 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.9 ± 2.1 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up (mo) | 49 (25–84) | 49 (28–85) | 0.615 |

| ESRD and death | 55 (14.9) | 51 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| SAEs | 46 (12.5) | 18 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| CKD stage | |||

| 1 | 116 (26.5) | 321 (73.5) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 108 (34.4) | 206 (65.6) | |

| 3 | 116 (48.3) | 124 (51.7) | |

| 4/5 | 29 (67.4) | 14 (32.6) |

Unless otherwise indicated values are n (%), means ± SDs, or median (25th–75th centiles). Bold values are statistically significant.

BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; SAEs, severe adverse effects.

Table 2.

Factors found to affect severe adverse events in patients with IgAN on multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Multivariable analysis |

||

|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 1.52 (0.88–2.62) | 0.131 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.010 |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h) | 1.02 (0.93–1.12) | 0.650 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.905 |

| Corticosteroid therapy | ||

| Noncorticosteroid therapy | Reference | - |

| Corticosteroid alone | 4.13 (1.97–8.67) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant | 6.34 (3.43–11.72) | <0.001 |

Bold values are statistically significant.

CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; OR, odds ratio.

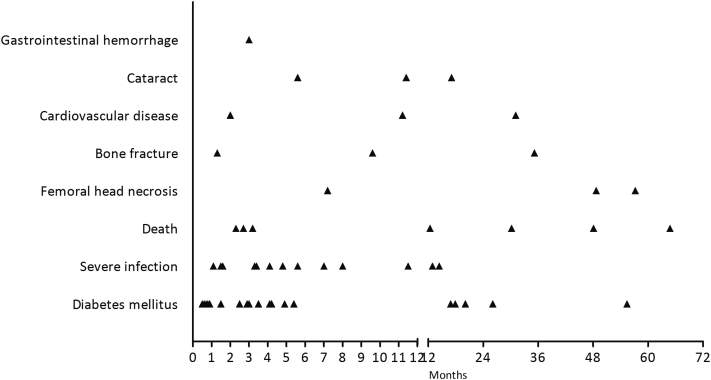

SAEs were associated with 7 deaths (1.9%; 4 died of infection, 2 died of cardiovascular disease, 1 died of lymphoma), DM (n = 19, 5.1%), severe infection necessitating hospitalization or fatal infection (n = 18, 4.9%), osteonecrosis of the femoral head or bone fracture (n = 6, 1.6%), cardiocerebral vascular disease (n = 4, 1.1%), cataract (n = 3, 0.8%), and gastrointestinal hemorrhage (n = 1, 0.3%) (Table 3). For DM, the median time (in months) was 3.5 (range 0.5–55.4), for severe infection was 3.8 (1.1–14.4), and for bone fracture or osteonecrosis was 22.4 (1.3–57.2) (Figure 1, Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of SAEs associated with corticosteroids in the corticosteroid user group and corticosteroid nonuser group, and median time from initial use of corticosteroids to SAE occurrence

| SAEs | Corticosteroid users, n (%) | Time, median (range) (mo) | Corticosteroid nonusers, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 (5.1) | 3.5 (0.5–55.4) | 3 (16.7) |

| Severe infection | 18 (4.9) | 3.8 (1.1–14.4) | 10 (55.5) |

| Death | 7 (1.9) | 12.4 (2.3–64.8) | 0 |

| Osteonecrosis of femoral head or bone fracture | 6 (1.6) | 22.4 (1.3–57.2) | 2 (11.1) |

| Cardiocerebral vascular disease | 4 (1.1) | 7.2 (2.0–31.1) | 2 (11.1) |

| Cataract | 3 (0.8) | 11.4 (5.6–17.1) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 (0.3) | 3 | 1 (5.6) |

| Total | 58 | 4.9 (0.5–64.8) | 18 |

SAEs, severe adverse effects.

Figure 1.

Occurrence time of severe adverse effects (SAEs). Scatter diagram of time when SAEs occurred.

Corticosteroid users with SAEs were much older (42 ± 13 vs. 33 ± 13 years, P < 0.001), had higher blood pressure (132 ± 16 vs. 124 ± 16 mm Hg, P = 0.001), and had lower eGFR (60 ± 30 vs. 75 ± 33 ml/min per 1.73 m2, P = 0.003) than those without SAEs (Table 4). Proportions of SAEs in stages 1, 2, 3 and 4/5 of chronic renal disease were 6.9%, 12.0%, 15.5%, and 24.1% (P for trend = 0.006), respectively. There were more SAEs in the corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant group than in the corticosteroid-only group (71.7% vs. 28.3%). Individual immunosuppressive agent on the risk of SAE was shown in Supplementary Table S1. Multivariable logistic regression analyses revealed that advanced age (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07; P < 0.001) and hypertension (OR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01–1.06; P = 0.009) were risk factors for corticosteroid-related SAEs (Table 5).

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics and follow-up information of the corticosteroid users with SAEs group and non-SAEs group

| Baseline characteristic | SAEs group (n = 46, 12.5%) | Non-SAEs group (n = 323, 87.5%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n [%])/female (n) | 24 (52.2)/22 | 180 (54.9)/148 | 0.730 |

| Age (yr) | 42 ± 13 | 33 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| Initial dosage of corticosteroid (mg/d) | 46 ± 9 | 46 ± 10 | 0.784 |

| Corticosteroid pulse | 8 (17.4) | 40 (12.4) | 0.345 |

| Reuse of corticosteroid | 9 (19.6) | 35 (10.8) | 0.087 |

| Corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant | 33 (71.7) | 186 (57.6) | 0.067 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 27 (58.7) | 143 (44.3) | |

| Tacrolimus | 4 (8.7) | 10 (3.1) | |

| Leflunomide | 4 (8.7) | 20 (6.2) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 5 (10.9) | 15 (4.6) | |

| Cyclosporine A | 7 (15.2) | 24 (7.4) | |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 132 ± 16 | 124 ± 16 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 83 ± 9 | 79 ± 12 | 0.067 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 99 ± 10 | 94 ± 12 | 0.010 |

| Serum creatinine (mmol/l) | 123 (81–178) | 103 (79–142) | 0.084 |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h) | 3.2 (1.9–6.7) | 3.0 (1.7–5.2) | 0.291 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 60 ± 30 | 75 ± 33 | 0.003 |

| Uric acid (μmol/l) | 401 ± 113 | 385 ± 100 | 0.334 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 130 ± 22 | 133 ± 20 | 0.232 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 33 ± 8 | 35 ± 8 | 0.267 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 0.444 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 6.1 ± 2.6 | 5.9 ± 2.0 | 0.702 |

| Follow-up (mo) | 35 (12–74) | 49 (27–86) | 0.016 |

| ESRD | 14 (30.4) | 41 (12.7) | 0.010 |

| CKD stage | |||

| 1 | 8 (6.9) | 108 (93.1) | 0.006 |

| 2 | 13 (12.0) | 95 (88.0) | |

| 3 | 18 (15.5) | 98 (84.5) | |

| 4/5 | 7 (24.1) | 22 (75.9) |

Unless otherwise indicated values are n (%), means ± SDs, or median (25th–75th centiles). Bold values are statistically significant.

BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; SAEs, severe adverse effects.

Table 5.

Factors found to affect SAEs associated with corticosteroids on multivariable logistic regression analyses

| SAEs versus non-SAEs |

Infection versus noninfection |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.98–1.05) | 0.441 |

| Sex (female) | 1.48 (0.76–2.85) | 0.244 | 1.28 (0.47–3.44) | 0.631 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | 0.009 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.253 |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h) | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.438 | 1.05 (0.92–1.20) | 0.494 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.309 | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.036 |

| Corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant | 1.66 (0.82–3.36) | 0.158 | 2.77 (0.77–9.99) | 0.119 |

Bold values are statistically significant.

CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; OR, odds ratio.

We also investigated the risk factors for severe infection. Among 18 severe-infection events, 4 patients died. Of those 18 patients, 14 (78%) received corticosteroids plus immunosuppressive agents, whereas 4 (22%) received corticosteroid-only therapy (Table 6). Among the corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant group, 14 patients (of 219, 6.4%) had a severe infection, compared with 4 patients (of 150, 2.7%) in the corticosteroid-only group, but it did not reach significance (OR: 2.77; 95% CI: 0.77–9.99; P = 0.119). Multivariable logistic regression analyses demonstrated that impaired renal function (eGFR: OR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.96–0.99; P = 0.036) was strongly associated with the risk of severe infection (Table 5).

Table 6.

Baseline characteristics and follow-up information of infection and infective death group and noninfection group of corticosteroid users

| Baseline characteristic | Infection and infective death (n = 18, 4.9%) |

Noninfection (n = 351, 95.1%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n [%])/female (n) | 8 (44.4)/10 | 158 (45.0)/193 | 0.962 |

| Age (yr) | 38 ± 15 | 34 ± 13 | 0.145 |

| Initial dosage of corticosteroid (mg/d) | 46 ± 11 | 48 ± 7 | 0.557 |

| Corticosteroid pulse | 1 (5.6) | 47 (13.4) | 0.545 |

| Reuse of corticosteroid | 3 (16.7) | 41 (11.7) | 0.461 |

| Corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant | 14 (77.8) | 205 (58.4) | 0.103 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 11 (61.1) | 159 (45.3) | |

| Tacrolimus | 3 (16.7) | 11 (3.1) | |

| Leflunomide | 0 (0) | 24 (6.8) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 4 (22.2) | 16 (4.6) | |

| Cyclosporine A | 2 (11.1) | 29 (8.3) | |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 133 ± 18 | 124 ± 16 | 0.021 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 84 ± 9 | 80 ± 12 | 0.124 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 100 ± 11 | 95 ± 12 | 0.045 |

| Serum creatinine (mmol/l) | 130 (100–192) | 104 (79–143) | 0.030 |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h) | 4.7 (2.2–6.8) | 3.0 (1.7–5.2) | 0.120 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 54 ± 27 | 74 ± 33 | 0.010 |

| Uric acid (μmol/l) | 409 ± 111 | 386 ± 101 | 0.343 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 130 ± 22 | 133 ± 20 | 0.549 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 33 ± 7 | 34 ± 8 | 0.576 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 0.510 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 6.0 ± 2.8 | 5.9 ± 2.1 | 0.927 |

| Follow-up (mo) | 28 (8–63) | 49 (25–84) | 0.019 |

| ESRD | 8 (44.4) | 47 (13.4) | 0.001 |

| CKD stage | |||

| 1 | 2 (1.7) | 114 (98.3) | 0.021 |

| 2 | 5 (4.6) | 103 (95.4) | |

| 3 | 8 (6.9) | 108 (93.1) | |

| 4/5 | 3 (10.3) | 26 (89.7) |

Unless otherwise indicated values are n (%), means ± SDs, or median (25th–75th centiles). Bold values are statistically significant.

BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; SAEs, severe adverse effects.

To evaluate the cumulative corticosteroid dosage or duration on the risk of SAEs, a total of 44 pairs (1 SAE patient vs. 1 non-SAE patient) were successfully matched based on propensity scores. Baseline covariates before and after matching were shown in Supplementary Table S2. After matching, we accumulated the dosage of corticosteroids in each pair by the time from initial use of corticosteroids to SAE occurrence. As shown in Supplementary Table S3, there was no difference between the 2 groups on the dosage of corticosteroids (P = 0.274). In the comparison between patients with and without severe infection, there was also no difference (P = 0.407). Univariate logistic regression did not find the accumulated dosages of corticosteroids to be a risk factor of SAEs in this cohort (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.91–1.30; P = 0.365). We also compared the proportion of SAEs between the low-dose steroids group (less than 40 mg/day, 5 of 38) and high-dose group (more than 40 mg/day, 41 of 331), and did not find a significant difference (P = 0.800).

Discussion

KDIGO guidelines for glomerulonephritis recommend a full-dosage corticosteroid regimen for patients with persistent proteinuria. However, safety data for corticosteroid use in IgAN are scarce. In this study we evaluated the safety of corticosteroids in 1034 patients. We found full-dosage steroids use was associated with high toxicity in this population. The absolute risk of severe adverse events was 12.5% mainly coming from DM (5.1%) and severe infection (4.9%). Relative risk of corticosteroid therapy for AEs was more than 5-fold than that for supportive therapy. This risk increased in patients who were older and had hypertension, whereas impaired kidney function was the strongest risk factor for severe infection. So corticosteroid use in this patient group should be prudent.

KDIGO guidelines suggest corticosteroid therapy in IgAN patients with persistent proteinuria, but this recommendation is based mainly on several clinical trials.10, 11, 12 Previously, we evaluated the safety of corticosteroids in 245 patients with IgAN from 9 clinical trials.13 SAEs occurred in 6.9% of patients (DM in 4 patients, hypertension in 12, and gastrointestinal bleeding in 1). None of the clinical trials reported the incidence of infection even though this was a common AE. The large European Validation Study of the Oxford Classification of IgAN (VALIGA) study, a multicenter cohort study with European patients, supported benefits of steroids especially those with impaired kidney function, but it did not evaluate the safety of steroids.16 Two recently completed large multicenter trials, the Supportive Versus Immunosuppressive Therapy of Progressive IgA nephropathy (STOP-IgAN) trial and the TESTING study, reported a high risk of severe infection. In the STOP-IgAN trial,17 8 patients (of 82, 9.8%) had severe infection and 9 patients (of 82, 12.2%) had DM or impaired glucose tolerance in the corticosteroid group or corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant group. In a placebo-controlled trial to evaluate SAEs, the prevalence of infection, bone fractures, or DM in the methylprednisolone group increased by 4.95-fold.18, 19 These safety data are in accordance with the findings from the present study. These results suggest future guidelines should balance the risk and benefits of a corticosteroid regimen in IgAN.

In this study, we did not found the cumulative steroid exposure was a risk factor of SAEs. The reason was that most patients used a similar full-dosage corticosteroid regimen that was consistent with current KDIGO guidelines in our center, and few patients (10%) used low-dose steroids. The ongoing international randomized control trial TESTING study (clinicaltrials.gov no. 01560052) evaluates the efficacy and safety of lower versus full-dosage steroids regimens in patients with IgAN. This trial will definitely answer the question of safety of different steroids exposure in IgAN. In the present study, 4 patients died from severe infection, 2 from cardiovascular disease, and 1 case from lymphoma, but none of the patients having supportive therapy died. Most cases of DM occurred within the first 6 months (during exposure to a high dosage regimen of corticosteroids). Often, severe infection occurred after 3 (median: 3.8) months, when the corticosteroid dosage had started to decrease, whereas bone fractures or osteonecrosis usually occurred after 6 months. In this study, we found older age and hypertension were risk factors for SAEs. Older age and hypertension were also associated with diabetes or cardiovascular diseases, which accounted for the main events of SAEs, in the general population.20 Late occurrence of infection was also noted in patients with impaired renal function in another study, possibly due to a decrease in the number of lymphocytes in IgAN patients.21 These findings will help clinicians monitoring patients with IgAN receiving corticosteroids.

The present study had two main limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, and most AEs were obtained from medical records. Hence, we cannot be sure that some AEs were not missed. Second, this was a single-center study with a selection bias. A large multicenter and prospective study is necessary to confirm our data.

A full-dosage corticosteroid regimen or a corticosteroid plus immunosuppressive agents regimen is associated with a high risk of AEs in IgAN patients, especially those who are older, have hypertension, or have impaired renal function. Current guidelines on corticosteroid regimens in IgAN should be reviewed with regard to safety.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (grants 81270795, 81621092, 81670649), the Natural Science Foundation for Excellent Young Scientists (grant 81322009), and Capital of Clinical Characteristics and the Applied Research Fund (grant Z161100000516005).

Footnotes

Figure S1. Identification method for eligible patients.

Table S1. Options and the total dosages on each type of nonsteroid immunosuppressant.

Table S2. Covariate balances before and after propensity-score matching.

Table S3. Total dosages of corticosteroids between SAE and non-SAE groups after propensity-score matching.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.kireports.org.

Supplementary Material

Identification method for eligible patients.

Options and the total dosages on each type of nonsteroid immunosuppressant.

Covariate balances before and after propensity-score matching.

Total dosages of corticosteroids between SAE and non-SAE groups after propensity-score matching.

References

- 1.D'Amico G. The commonest glomerulonephritis in the world: IgA nephropathy. Q J Med. 1987;64:709–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Julian B.A., Waldo F.B., Rifai A., Mestecky J. IgA nephropathy, the most common glomerulonephritis worldwide: a neglected disease in the United States? Am J Med. 1988;84:129–132. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donadio J.V., Grande J.P. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:738–748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radford M.J., Donadio J.J., Bergstralh E.J. Predicting renal outcome in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:199–207. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V82199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Amico G. Influence of clinical and histological features on actuarial renal survival in adult patients with idiopathic IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: survey of the recent literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv J., Zhang H., Zhou Y. Natural history of immunoglobulin A nephropathy and predictive factors of prognosis: a long-term follow up of 204 cases in China. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008;13:242–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moriyama T., Tanaka K., Iwasaki C. Prognosis in IgA nephropathy: 30-year analysis of 1,012 patients at a single center in Japan. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Amico G., Colasanti G., Barbiano di Belgioioso G. Long-term follow-up of IgA mesangial nephropathy: clinico-histological study in 374 patients. Semin Nephrol. 1987;7:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radhakrishnan J., Cattran D.C. The KDIGO practice guideline on glomerulonephritis: reading between the (guide)lines—application to the individual patient. Kidney Int. 2012;82:840–856. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lv J., Zhang H., Chen Y. Combination therapy of prednisone and ACE inhibitor versus ACE-inhibitor therapy alone in patients with IgA nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:26–32. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pozzi C., Andrulli S., Del Vecchoi L. Corticosteroid effectiveness in IgA nephropathy: long-term results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:157–163. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000103869.08096.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pozzi C., Bolasco P.G., Fogazzi G.B. Corticosteroids in IgA nephropathy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:883–887. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03563-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lv J., Xu D., Perkovic V. Corticosteroid therapy in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1108–1116. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011111112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lv J, Zhang H, Perkovic V. Therapeutic evaluation of steroids in IgA nephropathy global study [abstract 3394]. 53rd ERA-EDTA Congress. May 22, 2016; Vienna, Austria.

- 15.Xie P., Huang J.M., Lin H.Y. CDK-EPI equation may be the most proper formula based on creatinine in determining glomerular filtration rate in Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45:1057–1064. doi: 10.1007/s11255-012-0325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tesar V., Troyanov S., Bellur S. Corticosteroids in IgA nephropathy: a retrospective analysis from the VALIGA study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2248–2258. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rauen T., Eitner F., Fitzner C. Intensive supportive care plus immunosuppression in IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2225–2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarcina C., Tinelli C., Ferrario F. Changes in proteinuria and side effects of corticosteroids alone or in combination with azathioprine at different stages of IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:973–981. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02300215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pozzi C., Andrulli S., Pani A. IgA nephropathy with severe chronic renal failure: a randomized controlled trial of corticosteroids and azathioprine. J Nephrol. 2013;26:86–93. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang S.H., Dou K.F., Song W.J. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2425–2426. author reply 2426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lv J., Zhang H., Cui Z. Delayed severe pneumonia in mycophenolate mofetil-treated patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2868–2872. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Identification method for eligible patients.

Options and the total dosages on each type of nonsteroid immunosuppressant.

Covariate balances before and after propensity-score matching.

Total dosages of corticosteroids between SAE and non-SAE groups after propensity-score matching.