Abstract

Clostridium thermocellum is a promising candidate for ethanol production from cellulosic biomass, but requires metabolic engineering to improve ethanol yield. A key gene in the ethanol production pathway is the bifunctional aldehyde and alcohol dehydrogenase, adhE. To explore the effects of overexpressing wild-type, mutant, and exogenous adhEs, we developed a new expression plasmid, pDGO144, that exhibited improved transformation efficiency and better gene expression than its predecessor, pDGO-66. This new expression plasmid will allow for many other metabolic engineering and basic research efforts in C. thermocellum. As proof of concept, we used this plasmid to express 12 different adhE genes (both wild type and mutant) from several organisms. Ethanol production varied between clones immediately after transformation, but tended to converge to a single value after several rounds of serial transfer. The previously described mutant C. thermocellum D494G adhE gave the best ethanol production, which is consistent with previously published results.

Keywords: Clostridium Thermocellum, Plasmid, adhE, Structural stability, Gene expression

Highlights

-

•

Developing of robust and reliable C. thermocellum expression plasmid.

-

•

Analysis on causes of plasmid instability and poor transformation efficiency.

-

•

Comparison of ethanol production from different adhEs.

1. Introduction

Clostridium thermocellum is a good candidate for producing biofuels from cellulosic biomass via consolidated bioprocessing (Olson et al., 2012). This microorganism is among the most effective described at solubilizing lignocellulose (Lynd et al., 2002), and ferments glucose and glucan oligomers to organic acids, hydrogen, and ethanol. In recent years, there have been attempts (Argyros et al., 2011, Biswas et al., 2015, Biswas et al., 2014, Deng et al., 2013, Papanek et al., 2015) at engineering C. thermocellum to produce ethanol as the sole product at high yield; these attempts thus far have fallen short of the high yields achieved by conventional ethanol producers such as yeast and Zymomonas.

Of the existing and reported genetic engineering efforts in C. thermocellum, most have taken the approach of gene deletions (Argyros et al., 2011, Biswas et al., 2015, Olson et al., 2010, Papanek et al., 2015, Rydzak et al., 2015, Tripathi et al., 2010, van der Veen et al., 2013). There have been a few reports of gene expression, or over expression, in C. thermocellum (Deng et al., 2013, Lo et al., 2015, Olson et al., 2013, Zheng et al., 2015), but methodologies are in general less well developed than for gene deletion. One example related to metabolic engineering is the expression of the Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum pyruvate kinase in C. thermocellum (Deng et al., 2013). Another example is the complementing of adhE activity in C. thermocellum adhE deletion strain (Lo et al., 2015, Zheng et al., 2015). In these cases, gene expression was achieved via targeted recombination of the gene of interest onto the chromosome, a process that takes several weeks under ideal conditions (Olson and Lynd, 2012a).

Plasmid-based gene expression, on the other hand, can be performed in a single step, and therefore lends itself to higher throughput metabolic engineering applications and thus is especially relevant during screening processes. Related prior work includes an attempt to complement the cipA deletion in C. thermocellum, and resulted in partial (~33% of wild type) restoration of Avicel solubilization (Olson et al., 2013). Efforts to identify native C. thermocellum promoters for use in expressing genes encountered issues with obtaining consistent and reliable results with reporter enzyme activities (Olson et al., 2015).

Here, we report improvements to a C. thermocellum expression plasmid, and use this improved plasmid to screen a variety of different adhEs for improved ethanol production in the C. thermocellum adhE deletion strain, LL1111.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plasmid and strain construction

Table 1 lists the strains and plasmids used or generated in this study; Table S1 lists the primers used in this study. Plasmids were constructed via the isothermal assembly method (Gibson, 2011), using a commercial kit sold by New England Biolabs (Gibson Assembly® Master Mix, product catalog number E2611). DNA purification was performed using commercially available kits from Qiagen (Qiagen catalog number 27,106) or Zymo Research (Zymo Research catalog numbers D4002 and D4006). Transformation of C. thermocellum was performed using previously described methods (Olson and Lynd, 2012a); all plasmid DNA intended for transforming into C. thermocellum was propagated and purified from Escherichia coli BL21 derivative strains (New England Biolabs catalog number C2566) to ensure proper methylation of plasmid DNA (Guss et al., 2012).

Table 1.

List of strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains | Organism | Description | Accession number | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli T7 express | Escherichia coli | fhuA2 lacZ: :T7 gene1 [lon] ompT gal sulA11 R(mcr-73: :miniTn10–TetS)2 [dcm] R(zgb-210: :Tn10–TetS) endA1 Δ(mcrC-mrr)114: :IS10 | New England Biolabs | |

| LL1004 | C. thermocellum | DSM 1313 | CP002416 | DSMZ |

| LL1111 | C. thermocellum | DSM1313 ∆hpt ∆adhE ldh(R175L) | SRX744221 | Lo et al. (2015) |

| LL1153 | C. thermocellum | Strain LL1111 with two forms of plasmid pSH007; the full length version, and a truncated version where adhE is deleted | This study | |

| LL1154 | C. thermocellum | Serial transfer of strain LL1153; plasmid pSH007 spontaneously integrated into the gapdh promoter region via homologous recombination | This study | |

| LL1160 | C. thermocellum | LL1111 adhE+ldh(R175L) | SRA273168 | Lo et al., 2015, Zheng et al., 2015 |

| LL1161 | C. thermocellum | LL1111 adhE+D494G ldh(R175L) | SRA273169 | Zheng et al. (2015) |

| adhE* | C. thermocellum | Ethanol tolerant strain of C. thermocellum | Brown et al. (2011) | |

| LL1231 | C. thermocellum | DSM 1313 Δhpt Δldh Δpta-ack ΔhydG Δpfl adhE(D494G P525L) | This study | |

| LL1025 | Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum | Strain JW/YS-485L | CP003184 | Shaw et al. (2008a) |

| LL1040 | T. saccharolyticum | Ethanologen T. saccharolyticum strain ALK2; genotype ∆ldh: :erm ∆(pta-ack): :kan | SRA233066 | Shaw et al. (2008b) |

| LL1049 | T. saccharolyticum | Ethanologen T. saccharolyticum strain; genotype ∆(pta-ack) ∆ldh Δor795: :metE-ure Δeps. This strain is also know n as strain M1442 | SRA233073 | Shaw et al. (2012) |

| LL1115 | Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus | Strain JW200 | ATCC | |

| LL1053 | Thermoanaerobacterium thermosaccharolyticum | DSM 571 | DSMZ | |

| LL451 | Clostridium straminisolvens | DSM 16,021 | DSMZ | |

| LL447 | Clostridium clariflavum | DSM 19,732 | DSMZ | |

| LL1232 | Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius | ATCC 43,742 | ATCC | |

| LL1258 | Thermoanaerobacter mathranii | DSM11426 | DSMZ | |

| Plasmids | ||||

| pDGO-66 | Expression vector | Olson et al. (2015) | ||

| pSH007 | pDGO-66 with DSM1313 clo1313_1798 cloned in at PvuII site | This study | ||

| pDGO125 | Improved expression vector, lacking annotated SSO | This study | ||

| pDGO143 | pDGO125 with insulator sequence between MCS and cat gene promoter | This study | ||

| pDGO126 | Improved expression vector, contains annotated SSO | This study | ||

| pDGO144 | pDGO126 with insulator sequence between MCS and cat gene promoter | This study | ||

| adhE expression plasmids | All plasmids used clo1313_2638 promoter to drive expression of the adhE; both promoter and gene were cloned into the HindIII site at the MCS in pDGO144 | |||

| pLL1119 | C. thermocellum wild type adhE (clo1313_1798) | This study | ||

| pLL1120 | C. thermocellum adhE D494G | This study | ||

| pLL1121 | C. thermocellum adhE P704L H734R, also known as AdhE* | Brown et al. (2011) | ||

| pLL1122 | C. thermocellum adhE D494G P525L | This study | ||

| pLL1123 | T. saccharolyticum wild type adhE (Tsac_0416) | This study | ||

| pLL1124 | T. saccharolyticum adhE V52A K451N; 13 aa repeat, also known as ALK2 | Shaw et al. (2008b) | ||

| pLL1125 | T. saccharolyticum adhE G544D | This study | ||

| pLL1126 | T. mathranii wild type adhE (Tmath_2110) | This study | ||

| pLL1127 | G. thermoglucosidasius wild type adhE (Geoth_RS19255) | This study | ||

| pLL1128 | T. thermosaccharolyticum wild type adhE | This study | ||

| pLL1129 | C. clariflavum wild type adhE (Clocl_0117) | This study | ||

| pLL1130 | T. ethanolicus wild type adhE (Genbank DQ836061.1) | This study | ||

| pLL1131 | C. straminisolvens wild type adhE (JCM21531_3461 to JCM21531_3464) | This study |

2.2. Re-designing the expression plasmid

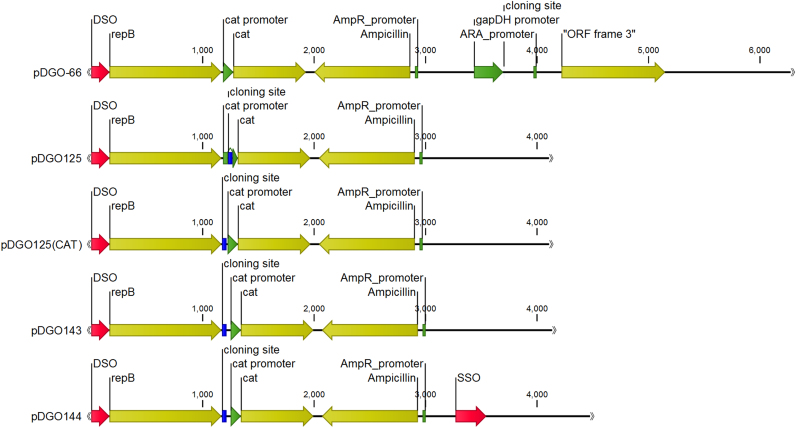

Fig. 1 and S1 shows the features of the various expression plasmids and the intermediates. We first removed the PvuII cloning site on our older expression plasmid, pDGO-66, in favor of a multiple cloning site (MCS), and inserted this MCS to the intergenic region between replication initiator gene repB and the thiamphenicol resistance gene, cat (Olson and Lynd, 2012b), thus placing the gene of interest between two genes that are essential for plasmid selection. We also eliminated the gapDH promoter from the plasmid to allow us the flexibility to use different promoters. The resulting plasmid was named pDGO125. A single-strand origin of replication (SSO) (Boe et al., 1989) was also added upstream of the double-strand origin of replication (DSO) in pDGO125, as there was no canonical SSO in plasmid pDGO-66; the resulting plasmid was named pDGO126. We later identified a promoter region upstream of the cat gene that we had disrupted with the MCS in plasmids pDGO125 and pDGO126; we thus moved the MCS to be upstream of the cat promoter region in both plasmids to generate pDGO125cat and pDGO126cat. Lastly, a 27 bp “insulator” sequence was introduced into plasmids pDGO125cat and pDGO126cat between the MCS and the cat promoter region, resulting in plasmids pDGO143 and pDGO144, respectively. All adhE expression plasmids used the Clo1313_2638 promoter (Olson et al., 2015) to drive expression of the adhE gene. Both the promoter and gene were cloned into the HindIII site at the MCS in plasmid pDGO144.

Fig. 1.

Functional organization of key plasmids. From top to bottom: pDGO-66 starting vector; pDGO125 relocating the cloning site from after repB-cat to between the two genes (resulting in cat promoter becoming disrupted); pDGO125(CAT) moving the cloning site from within the cat promoter to upstream; pDGO143 inserting an insulator sequence between the cloning site and the cat promoter; pDGO144 including a broad-host range SSO into the plasmid. The associated impacts on transformation efficiencies for the plasmids shown here are noted in Table 2.

2.3. Determining the segregational and structural stability of plasmids

Plasmids were transformed into C. thermocellum strain LL1004 (wild type), colonies were picked, and the presence of the plasmid was verified by PCR with primers XSH0210 and XSH0211. To determine plasmid structural stability after transformation into C. thermocellum, plasmid DNA was isolated from transformants and analyzed by PCR and restriction digestion. To determine segregational stability, cultures of C. thermocellum strain LL1004 bearing the respective plasmids were grown with or without thiamphenicol selection, and the fraction of plasmid-containing colonies was determined by dilution plating, with and without thiamphenicol selection. Plasmid DNA from C. thermocellum was prepared using the Qiagen DNA miniprep kit, with the added step of incubating the harvested and re-suspended cells with Epicentre Ready-Lyse™ lysozyme solution (Epicentre catalog number R1804m) at 37 °C for 30 min in buffer P1, before proceeding with the rest of the miniprep protocol, following the instructions of the manufacturer.

2.4. Media and growth conditions

All chemicals were of molecular grade, and were obtained from either Sigma Aldrich or Fisher Scientific, unless otherwise specified. C. thermocellum strains were grown in anaerobic chambers (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lakes, MI, USA) at 55 °C, with the hydrogen concentrations in the chamber maintained at greater than 1.5%. Two media formulations were used, with both containing 5 g/L cellobiose (Sigma C7252) as the primary carbon source: complex medium CTFÜD (Olson and Lynd, 2012a) with initial pH of 7.0 (pH measured at room temperature) was used for growing competent C. thermocellum cells for transformation, as well as for recovery post-electroporation and initial plasmid tests. Defined medium MTC (Ozkan et al., 2001, Zhang and Lynd, 2003) with initial pH of 7.4 at room temperature was used to determine ethanol production from the various adhEs. Where needed, thiamphenicol dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 6 µg/ml. When switching strains from CTFÜD medium to MTC medium, the strains were transferred 3 times at a 1:100 dilution each time to remove any yeast extract carried over from the CTFÜD medium.

2.5. Biochemical assays

Cultures for the ethanol and cellobiose assays were inoculated with 2% inoculum, and then grown anaerobically at 55 °C for 72 h. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (5 min at >20,000 g), and the supernatant was used in the assays. The concentration of ethanol in the cultures was determined via ADH enzyme assay in the acetaldehyde and NADH-producing direction (Bisswanger, 2011). The reaction had the following component concentrations: 67 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM glycine, 1 mM semicarbazide, 8.3 mM NAD+, and 0.1 U/ml alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme (Sigma A3263); 20 µL of sample was used in a 200 µL reaction volume. The reactions were followed on a microplate reader by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 340 nm (i.e. NADH accumulation) and comparing the results against known standards.

Cellobiose assays were adapted from glucose determination assays (Bisswanger, 2011) in that a beta-glucosidase (Novozymes 188, formerly sold by Sigma as product C6105) was included in the reaction mixture. The reaction was followed on a microplate reader by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 340 nm (i.e. NADPH accumulation). Reaction rates were determined from a linear region of the absorbance curve; standard curves were generated using solutions with known cellobiose concentrations.

2.6. Measuring adhE expression

adhE expression was measured via reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Strains were cultured in 5 ml MTC-5 defined medium, and harvested in log-phase (OD600 0.6–0.8); 0.6 ml aliquots of the cell cultures were immediately treated with RNA protect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen catalog number 76,506) and stored at −80 °C until time for RNA purification. RNA purification, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR were performed as previously described (Zhou et al., 2015); the primers used for qPCR are described in Table S1. adhE expression in each strain was normalized against recA expression (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) to allow for comparison of adhE expression across the strains.

2.7. Sequencing

Routine Sanger sequencing was performed by Genewiz Inc.; whole genome resequencing of strains was performed by the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute. Sequence data was analyzed with the CLC Genomics Workbench version 7 (Qiagen Inc.). Sequencing data is available for strains LL1153 and LL1154 from the Sequence Read Archive; the accession numbers are SRA278181 and SRA278180.

2.8. Proteomic analyses

The abundance of AdhE protein expressed in each strain was measured by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in technical duplicate. For each measurement, 45 ml of culture grown in MTC defined medium was used. Cells were harvested in mid-log phase (OD600=0.5–0.8). The fermentation products from an aliquot of the same culture were measured by high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (Holwerda et al., 2014). Cells were pelleted, washed, and processed for LC-MS/MS-based proteomic analysis as previously described (Giannone et al., 2011). Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis buffer, boiled for 5 min and pulse-sonicated. Two milligrams of the resulting whole-cell protein extract was precipitated by trichloroacetic acid, pelleted, washed and air-dried. The pelleted protein was then resuspended in urea–dithiothreitol, cysteines blocked by iodoacetamide and proteins digested to peptides via two 20 μg additions of sequencing-grade trypsin (Sigma Aldrich). Proteolyzed samples were then salted, acidified and filtered through a 10 kDa MWCO membrane (Vivaspin 2; GE Healthcare).

Peptides from each sample were quantified by BCA assay (Pierce) and 5 µg analyzed via nanospray LC-MS/MS using a LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) operating in data-dependent acquisition (one full scan at 15k resolution followed by 10 MS/MS scans in the LTQ, all one µscan). Each 5 µg peptide sample was separated by HPLC over a 120 min organic gradient. Resultant peptide fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) were searched against the C. thermocellum DSM 1313 proteome database concatenated with various AdhE proteins (Table S1), common contaminants, and reversed sequences to control false-discovery rates using Myrimatch v.2.1 (Tabb et al., 2008). Peptide spectrum matches were filtered by IDPicker v.3 (Ma et al., 2009) and assigned matched-ion intensities (MIT) based on observed peptide fragment peaks (Giannone et al., 2015). PSM MITs were summed on a per-peptide basis and only those uniquely and specifically matching a particular protein were moved onto subsequent analysis with InfernoRDN (Taverner et al., 2012). Peptide intensity distributions were log2-transformed, normalized by LOESS, and standardized by median centering across samples as suggested by InfernoRDN.

Before determining protein abundance, low quality peptides were removed based on the following criteria: Peptides not present in both technical replicates were removed. Peptides not present in all members of a strain group were removed. The C. thermocellum strain group included LL1004 and LL1111 with plasmids pLL1119, pLL1120, pLL1121 and pLL1122. Since LL1111 with plasmid pLL1119 does not have a full-length AdhE protein (being the AdhE deletion negative control), peptides that were only absent from that strain were not eliminated. Furthermore, there are a number of peptides that are unique to a specific mutation. For example, the peptides TFFDVSPDPSLASAK and TFFDVSLDPSLASAK differ by a single amino acid residue resulting from the P525L mutation in the AdhE protein from plasmid pLL1122. Peptides AYENGASDPVAR and AYENGASDLVAR differ by a single amino acid residue resulting from the P704L mutation in the AdhE protein from plasmid pLL1121. Similar examples are found in the T. saccharolyticum AdhE mutants. Since the appropriate variant of each peptide was found in its respective strain, so these peptides, and ones displaying similar patterns were not removed. The T. saccharolyticum group included strain LL1111 with plasmids pLL1123, pLL1124 and pLL1125. Other plasmids were not grouped.

For reference, the same analysis was performed for GapDH and Pfk, two proteins that play a key role in glycolysis and are often used as reference genes in quantitative PCR experiments (Supplemental Fig. S2A and S2B).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Plasmid stability problems with pDGO-66

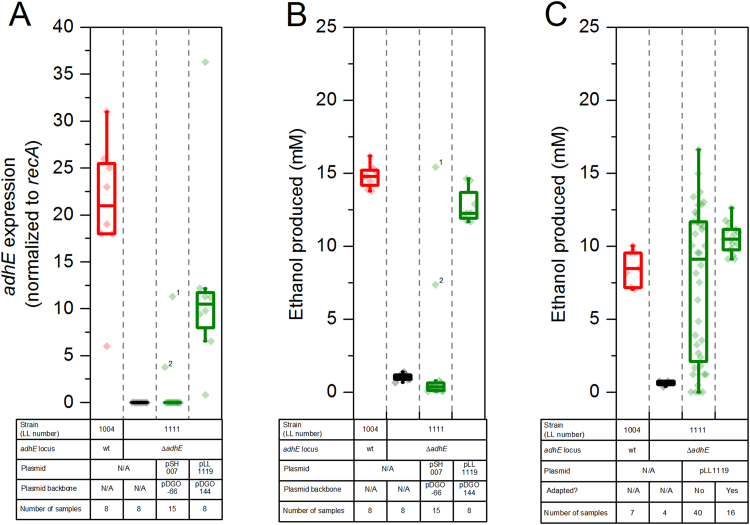

In our first attempts to express adhE using plasmid pDGO-66, most colonies showed non-existent or low levels of ethanol production, although, initially, one colony gave high ethanol production (Fig. 2). One low-ethanol producing colony was named LL1153. Re-sequencing analysis of strain LL1153 revealed the presence of two forms of the plasmid pSH007: the full length version, and a version where the adhE gene had been deleted (Fig. S3). The full-length version represented only about 10% of all of the plasmid population, and may explain the low ethanol production of this strain, despite the maintenance of the plasmid antibiotic resistance phenotype.

Fig. 2.

A.adhE expression (normalized to recA expression) in wild type C. thermocellum, adhE deletion strain LL1111, and LL1111 complemented with pSH007 (older expression plasmid) or pLL1119 (newer expression plasmid) B-C. Ethanol production from wild type C. thermocellum (strain LL1004), C. thermocellum adhE deletion strain LL1111, and various methods of complementation. (B) shows the improvement in ethanol production obtained by switching from the pDGO-66 backbone to the pDGO144 backbone. This data was collected on MTC-5 defined medium with 6 µg/ml thiamphenicol. (C) shows the effect of serial transfer on ethanol production in rich medium (CTFÜD with 6 µg/ml thiamphenicol). Plasmid pLL1119 expresses the C. thermocellum adhE under control of the Clo1313_2638 promoter on the pDGO144 plasmid backbone. The box plot shows the 25–75th percentile range. Whiskers on the box plot represent 1.5× the interquartile range. Superscripts on data points in (A) and (B) represent data points for specific strains, 1LL1153 and 2LL1154, respectively.

Serial transfer of strain LL1153 resulted in an increase in ethanol production. We named this adapted strain LL1154 (this strain is shown in Fig. 2(B) as the data point exhibiting high ethanol production from the pDGO-66 based plasmid). Re-sequencing analysis of this strain revealed that the plasmid – and the adhE gene – had integrated into the genome at the gapDH locus, possibly by homologous recombination with the plasmid-based gapDH promoter region (see pDGO-66 plasmid map in Fig. S1). While we have long suspected that our plasmids were spontaneously integrating on the chromosome, here we provide direct evidence to support our hypothesis (Fig. S4). A recent report describing isobutanol production in C. thermocellum also documented the spontaneous integration of plasmid DNA onto the chromosome (Lin et al., 2015).

3.2. Improving plasmid structural stability

Based on our experience with plasmid pDGO-66, we determined that the low ethanol production was due to problems with structural stability, particularly loss of the adhE gene (Fig. S3). Plasmids that replicate via the rolling-circle method require both a double-strand origin of replication (DSO) and a single-strand origin of replication (SSO) (Khan, 2005). In plasmid pDGO-66, the DSO is upstream of the repB gene, but no SSO is known to exist in this plasmid. In some cases, plasmids without an SSO are still able to replicate, although the efficiency of replication is reduced, and the single-stranded DNA that accumulates can stimulate the formation of deletions (Bron et al., 1991) We inserted the broad-host-range SSO from plasmid pUB110 (Boe et al., 1989), which has an identical repB gene to that of plasmid pDGO-66. All of our initial plasmids were created both with and without the SSO. We looked at its effect on transformation efficiency, structural stability (Fig. S5) and segregational stability, and ultimately did not find any effect of its presence. One possibility is that this SSO is not recognized by C. thermocellum; another possibility is that the plasmid already contains a cryptic SSO.

Next, we moved the relative position of the gene expression cassette upstream of the antibiotic resistance marker. The purpose of this was to prevent the kind of truncation event observed with plasmid pSH007, since the plasmid would need both the replicon and the antibiotic resistance marker to function. Putting the multi-cloning site (MCS) upstream of the cat gene reduced transformation efficiency to 0 (plasmids pDGO125 and pDGO126). We suspected there might have been a problem with the particular MCS that we used, so we used a different MCS from plasmid pMU102 (MCS102), which is known to have high transformation efficiency (plasmids pDGO125(102MCS) and pDGO126(102MCS)). This did not improve transformation efficiency, so we tried using only the 6 bp recognition sequence of the PvuII restriction enzyme or eliminating the MCS entirely (plasmids pDGO125(PvuII), pDGO126(PvuII), pDGO125(no MCS) and pDGO126(no MCS)). In both cases, transformation efficiency improved. This led us to consider the possibility that we were disrupting a promoter of the cat gene. To address this problem, we moved the MCS 54 bp further upstream (101 bp upstream of the cat gene start codon). Finally, we added a 27 bp sequence of random DNA to “insulate” the cat promoter from the effect of the MCS. This final set of plasmids, pDGO143 and pDGO144, had transformation efficiencies as high as the pMU102 positive control (Table 2); Fig. 1 highlights the most important steps in the development of pDGO-66 to pDGO143/144.

Table 2.

Transformation efficiencies of the plasmids that were developed in this study. Ratios were determined from three independent transformations of these plasmids into C. thermocellum strain LL1004 (wild type), normalized to pMU102 positive control's transformation efficiency. For transformation efficiency measurements, n=3.

| Plasmid name |

Normalized transformation efficiency (CFU/µg DNA) |

Annotated SSO included? | repB-catorientation | Distance between an upstream feature andcatgene ATG | Description | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Standard deviation | ||||||

| pMU102 | 1.00 | 0.00 | N | repB-cat-MCS2 | 106 | Positive control plasmid | Olson and Lynd, 2012a, Olson and Lynd, 2012b |

| pDGO-66 | 0.20 | 0.13 | N | repB-cat-PvuII | 106 | C. thermocellum expression plasmid based on pDGO-37 with addition of gapDH promoter and Clo1313_1881 terminator | Olson et al. (2015) |

| pDGO125 | 0.00 | 0.00 | N | repB-MCS1-cat | 47 | MCS original location | This study |

| pDGO125(102MCS) | 0.00 | 0.00 | N | repB-MCS2-cat | 47 | pMU102 MCS, original location | This study |

| pDGO125(PvuII) | 0.00 | 0.00 | N | repB-PvuII-cat | 47 | PvuII site, original location | This study |

| pDGO125(no MCS) | 4.35 | 5.40 | N | repB-cat | 106 | no MCS | This study |

| pDGO125(CAT) | 1.07 | 1.32 | N | repB-MCS2-cat | 101 | MCS moved upstream of cat promoter | This study |

| pDGO143 | 1.51 | 1.33 | N | repB-MCS2-insulator-cat | 128a | MCS moved and insulator added | This study |

| pDGO126 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Y | repB-MCS1-cat | 47 | SSO, MCS original location | This study |

| pDGO126(102MCS) | 0.00 | 0.00 | Y | repB-MCS2-cat | 47 | SSO, pMU102 MCS, original location | This study |

| pDGO126(PvuII) | 0.00 | 0.00 | Y | repB-PvuII-cat | 47 | SSO, PvuII site, original location | This study |

| pDGO126(no MCS) | 1.62 | 0.66 | Y | repB-cat | 106 | SSO, no MCS | This study |

| pDGO126(CAT) | 1.67 | 1.63 | Y | repB-MCS2-cat | 101 | SSO, MCS moved upstream of cat promoter | This study |

| pDGO144 | 1.83 | 0.90 | Y | repB-MCS2-insulator-cat | 128a | SSO, MCS moved and insulator added | This study |

The insulator sequence is not counted as a feature; in pDGO143 and pDGO144, the feature used for determining this number is the MCS.

3.3. AdhE expression with the new plasmid

We tested the new plasmid by using it to express adhE in the LL1111 adhE deletion strain (Lo et al., 2015), This strain was chosen because it shows low levels of ethanol production, and also had low levels of adhE expression (Fig. 2(A)). The adhE gene is a good test case, because the AdhE protein is one of the highest-expressed proteins in C. thermocellum (Rydzak et al., 2012), and presumably similar levels of adhE expression are required for matching wild type levels of ethanol production.

Initial attempts to express adhE in the pDGO-66 backbone were largely unsuccessful. Out of 15 colonies screened, only 1 showed ethanol production greater than zero (this strain was later renamed LL1153, and subsequently adapted to generate strain LL1154, see plasmid stability discussion). By contrast, adhE expression in the pDGO144 plasmid backbone showed ethanol production at almost wild type levels for 8 out of 8 colonies tested (note that this was after serial transfer) (Fig. 2(B)).

To confirm that the improvement in ethanol production was due to improved expression of adhE, we compared normalized adhE expression in strains of LL1111 complemented either with pDGO-66 or pDGO144, expressing C. thermocellum adhE (pSH007 and pLL1119, respectively). We found that overall, the improved expression plasmid, pDGO144, more reliably resulted in high levels of adhE expression (i.e. comparable to expression levels in wild type C. thermocellum), whereas with pDGO-66, we saw in most cases that adhE expression was non-existent (i.e., equivalent to the negative control, parent adhE deletion strain, LL1111, Fig. 2(A)).

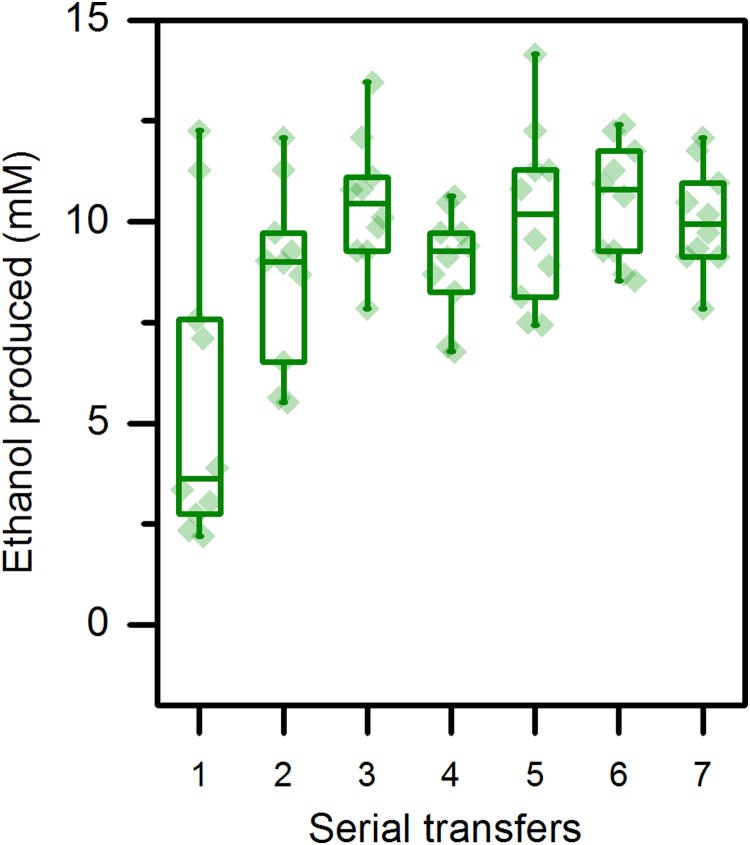

The effect of serial transfer is shown in Fig. 2(C). Although colonies showed a range of ethanol production levels upon initial transformation, several rounds of serial transfer caused ethanol production to converge on a single value (Fig. 3) that was similar to that of wild type. Regardless of the initial amount of ethanol production, after about 3 rounds of serial transfer, ethanol production had stabilized (Fig. 3). Differences in ethanol production were not due to differences in cellobiose consumption; in all cases where we measured cellobiose consumption, we found it was >95% complete.

Fig. 3.

Ethanol production of strain LL1111 (adhE deletion) with plasmid pLL1119 (wild type Cth adhE) over several serial transfers. 10 colonies were subjected to daily serial transfers in CTFÜD medium with added thiamphenicol; each transfer was cultured for a total of 72 h before ethanol production was measured.

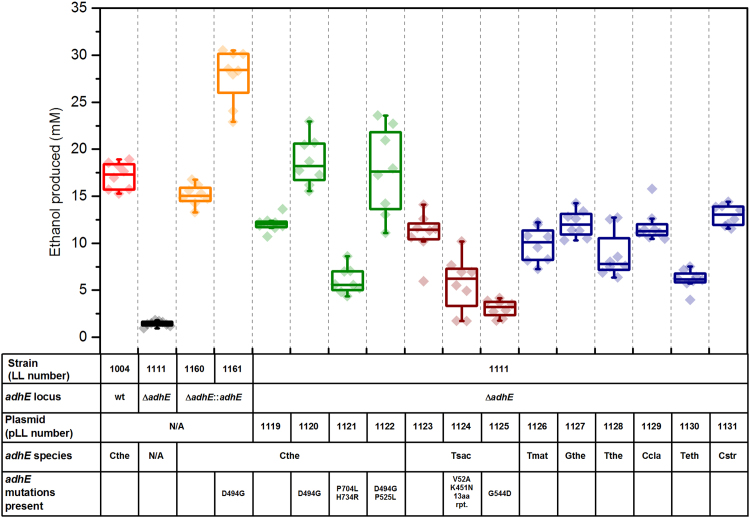

3.4. Expressing different adhEs in strain LL1111

With an improved expression plasmid, we tested whether ethanol production could be improved by using different adhEs; we chose 12 different adhEs (Table 1) and cloned them into plasmid pDGO144 under the control of the strong Clo1313_2638 promoter (Olson et al., 2015), and transformed these plasmids into the adhE deletion strain LL1111. We observed that the C. thermocellum D494G adhE gave the best ethanol production, consistent with previous reports (Zheng et al., 2015), which we attribute to an increase in NADPH-linked ADH activity. Another mutation, P525L, when combined with the D494G mutation, had the effect of increasing ethanol production in some colonies, but the overall effect was more varied (Fig. 4); this new adhE mutation (D494G P525L) came from the strain LL1231 (∆hpt ∆hydG ∆ldh ∆pfl ∆(pta-ack)), which was a strain evolved for high ethanol production by 2000 generations of serial transfer in 50 g/L cellobiose MTC-5 medium (unpublished data). With plasmid pLL1121 (adhE P740L H734R), despite being from an ethanol tolerant C. thermocellum strain (Brown et al., 2011), we nonetheless observed poorer performance compared to the other C. thermocellum adhEs, consistent with reported values; we suspect this is due to the decreased NADH-linked ADH activity of the mutant AdhE P740L H734R protein (Zheng et al., 2015).

Fig. 4.

Ethanol production as a result of expressing an adhE gene in the C. thermocellum adhE deletion strain LL1111. Strains LL1160 and LL1161 show complementation of the adhE deletion with either wild type adhE or the D494G mutant adhE, and have been described previously (Lo et al., 2015, Zheng et al., 2015). For each condition, 8 colonies were assayed. Data for each colony is represented as a single point and was measured in biological triplicate experiments (error bars not shown on individual data points for clarity). For each experiment, ethanol was measured in duplicate assays. The box plot shows the 25–75th percentile range. Whiskers on the box plot represent 1.5× the interquartile range. adhE species are as follow: C the – C. thermocellum, Tsac – T. saccharolyticum, Tmat – T. mathranii, Gthe – G. thermoglucosidasius, The – T. thermosaccharolyticum, Ccla – C. clariflavum, Teth – T. ethanolicus, Cstr – C. straminisolvens.

The mutant T. saccharolyticum adhEs used in this study were both taken from strains that had been engineered for high ethanol yield (Shaw et al., 2012, Shaw et al., 2008b), it may therefore be surprising that we observed that these adhEs did not result in high ethanol production in strain LL1111. A recent report (Zheng et al., 2015) that characterized these two adhEs noted that not only had both adhEs undergone a change in cofactor preference, but also the overall NAD(P)H-linked ADH activity had decreased relative to wild type. One potential explanation for low ethanol production from the T. saccharolyticum adhE genes is that their NADPH-linked cofactor specificity is not compatible with the NADPH supply in C. thermocellum. Another possibility is that the reduced specific ADH activity results in decreased ethanol production (note that in T. saccharolyticum, this may be partly ameliorated by ethanol production from other ADH enzymes).

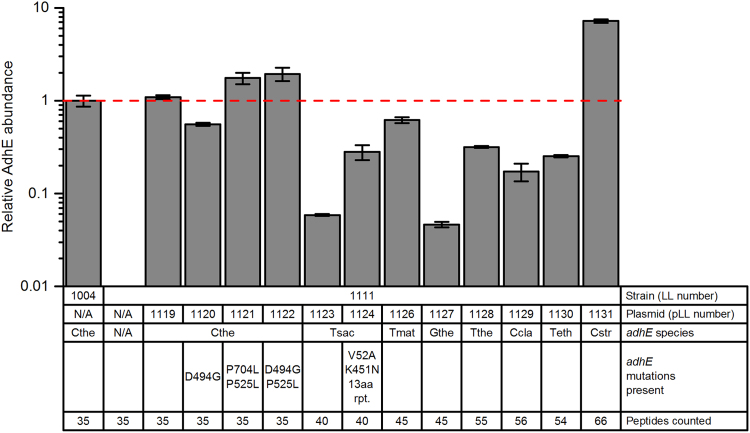

It is also possible that differences in AdhE protein levels in the various strains resulted in the differences in ethanol production. Abundance of each AdhE protein was measured by tandem mass spectrometry (Fig. 5, Table S2). In general, AdhE proteins originating from strains of C. thermocellum were expressed at high levels (equivalent to AdhE expression in wild-type C. thermocellum). Exogenous AdhE proteins were expressed at moderate levels (5–50% of wild-type C. thermocellum AdhE levels). Note that this still a very high level. Even the proteins expressed at the lowest level relative to C. thermocellum AdhE (i.e. AdhE from T. saccharolyticum from plasmid pLL1123 and from G. thermoglucosidasius from plasmid pLL1127) were still expressed in the top 30th percentile of protein expression in their respective strains (Table S2). Although there is clearly room for improvement in expression levels of several AdhEs, these results demonstrate the utility of our expression plasmid.

Fig. 5.

Relative abundances of AdhE peptides in representative samples of each strain normalized against wild type strain LL1004 levels. Values based on technical duplicate reads of one biological sample per strain; error bars depict standard deviation. Strain LL1111 (adhE deletion) with plasmid pLL1125 (Tsac adhE G544D) is not represented in this data set.

To determine if increases in ethanol production were related to changes in other fermentation products, we analyzed cultures of each strain by HPLC to measure liquid fermentation products. Ethanol, acetate, lactate and formate accounted for the majority of fermentation products. Even in the strains with the highest levels of ethanol production (LL1111 with plasmid pLL1120 (adhE D494G) and pLL1122 (adhE D494G P525L)), substantial lactate and acetate production remained (Table 3). It has been shown that lactate and acetate production in C. thermocellum can be eliminated by gene deletion (Argyros et al., 2011), and this may be an interesting direction for future work.

Table 3.

Comparison of fermentation products. Cultures were grown on MTC medium with 14.12±0.98 mM initial cellobiose concentration for 72 h; no residual cellobiose was detected in any of the cultures i.e., cellobiose was fully consumed in all cases. Standard deviations calculated from sample size of 3. ND: fermentation product was not detected or below threshold of detection.

| Strain | Plasmid |

Fermentation products (mM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Acetate | Lactate | Formate | Pyruvate | Malate | Succinate | ||

| LL1004 | N/A | 16.67±4.39 | 13.84±0.57 | 0.48±0.01 | 11.52±0.65 | 0.43±0.02 | 0.74±0.02 | 0.01±0.00 |

| LL1111 | N/A | 0.52±0.00 | 9.95±0.11 | 30.17±0.31 | 1.10±0.02 | 0.32±0.00 | 0.49±0.13 | 0.10±0.00 |

| LL1111 | pLL1119 | 11.64±1.17 | 8.98±1.00 | 13.78±2.26 | 5.11±1.59 | 0.38±0.03 | 0.47±0.14 | 0.05±0.04 |

| LL1111 | pLL1120 | 17.07±5.36 | 10.43±3.89 | 7.86±1.38 | 9.16±4.01 | 0.56±0.12 | 0.43±0.07 | 0.07±0.00 |

| LL1111 | pLL1121 | 5.61±0.91 | 10.87±2.96 | 18.22±3.26 | 5.96±2.17 | 0.63±0.36 | 0.46±0.11 | 0.07±0.01 |

| LL1111 | pLL1122 | 21.18±5.89 | 5.59±1.06 | 12.02±2.28 | 2.86±0.77 | 0.40±0.02 | 0.39±0.07 | 0.06±0.01 |

| LL1111 | pLL1123 | 9.26±3.83 | 12.36±4.81 | 15.56±2.10 | 6.38±3.28 | 0.39±0.06 | 0.58±0.02 | 0.07±0.00 |

| LL1111 | pLL1124 | 7.22±1.89 | 7.89±1.35 | 22.30±2.15 | 2.13±0.68 | 0.40±0.01 | 0.36±0.07 | 0.07±0.00 |

| LL1111 | pLL1125 | 4.77±0.86 | 7.91±1.22 | 22.79±1.01 | 2.24±0.55 | 0.46±0.05 | 0.66±0.09 | 0.07±0.01 |

| LL1111 | pLL1126 | 9.66±2.88 | 8.09±1.48 | 18.94±0.23 | 2.62±0.62 | 0.44±0.08 | 0.36±0.08 | 0.02±0.04 |

| LL1111 | pLL1127 | 12.00±1.40 | 6.89±0.97 | 17.50±0.99 | 2.71±0.79 | 0.48±0.07 | 0.33±0.01 | 0.07±0.00 |

| LL1111 | pLL1128 | 9.47±1.61 | 10.48±1.69 | 16.00±3.48 | 4.59±2.11 | 0.42±0.04 | 0.57±0.12 | 0.06±0.00 |

| LL1111 | pLL1129 | 11.57±1.39 | 8.21±1.48 | 16.28±2.43 | 3.83±1.29 | 0.42±0.02 | 0.56±0.23 | 0.06±0.00 |

| LL1111 | pLL1130 | 7.26±0.80 | 8.25±0.63 | 21.28±1.09 | 2.42±0.34 | 0.44±0.02 | 0.52±0.13 | 0.04±0.04 |

| LL1111 | pLL1131 | 13.45±3.73 | 6.31±0.46 | 18.85±3.78 | 2.33±0.10 | 0.36±0.01 | 0.28±0.00 | 0.07±0.00 |

4. Conclusion

We successfully expressed a variety of adhE genes to evaluate their abilities to improve ethanol production in an adhE deletion strain of C. thermocellum. Although we did not find any adhEs that were substantially better than previous reports (Lo et al., 2015, Zheng et al., 2015), our ability to do this with a replicating plasmid will allow for faster progress in future metabolic engineering work.

Acknowledgements

The BioEnergy Science Center is a U.S. Department of Energy Bioenergy Research Center supported by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research (Grant no. DE-AC05–00OR22725) in the DOE Office of Science. The manuscript has been authored by Dartmouth College under sub-contract no. 4000115284 and contract no. DE-AC05–00OR22725 with the U.S. Department of Energy. Resequencing was performed by the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, and is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract number DE-AC02–05CH11231.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meteno.2016.04.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- Argyros D.A., Tripathi S.A., Barrett T.F., Rogers S.R., Feinberg L.F., Olson D.G., Foden J.M., Miller B.B., Lynd L.R., Hogsett D.A., Caiazza N.C. High ethanol titers from cellulose by using metabolically engineered thermophilic, anaerobic microbes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:8288–8294. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00646-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisswanger H. Practical Enzymology. Wiley-Blackwell; Weinheim, Germany: 2011. Enzyme assays; pp. 101–103. ⟨ http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0958-1669(91)90057-C⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas R., Prabhu S., Lynd L.R., Guss A.M. Increase in ethanol yield via elimination of lactate production in an ethanol-tolerant mutant of Clostridium thermocellum. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas R., Zheng T., Olson D.G., Lynd L.R., Guss A.M., Wilson C.M., Zheng T., Giannone R.J., Dawn M., Olson D.G., Lynd L.R., Guss A.M. Elimination of hydrogenase active site assembly blocks H2 production and increases ethanol yield in Clostridium thermocellum. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2015:8. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boe L., Gros M.-F., Te Riele H., Ehrlich S.D., Gruss A. Replication Origins Of Single-stranded-DNA plasmid pUB110. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:3366–3372. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3366-3372.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bron S., Holsappel S., Venema G., Peeters B.P.H. Plasmid deletion formation between short direct repeats in Bacillus subtilis is stimulated by single-stranded rolling-circle replication intermediates. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1991;226:88–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00273591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.D., Guss A.M., Karpinets T.V., Parks J.M., Smolin N., Yang S., Land M.L., Klingeman D.M., Bhandiwad A., Rodriguez M., Raman B., Shao X., Mielenz J.R., Smith J.C., Keller M., Lynd L.R. Mutant alcohol dehydrogenase leads to improved ethanol tolerance in Clostridium thermocellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:13752–13757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102444108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Olson D.G., Zhou J., Herring C.D., Shaw A.J., Lynd L.R. Redirecting carbon flux through exogenous pyruvate kinase to achieve high ethanol yields in Clostridium thermocellum. Metab. Eng. 2013;15:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannone R.J., Huber H., Karpinets T., Heimerl T., Küper U., Rachel R., Keller M., Hettich R.L., Podar M. Proteomic characterization of cellular and molecular processes that enable the Nanoarchaeum equitans-ignicoccus hospitalis relationship. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannone R.J., Wurch L.L., Podar M., Hettich R.L. Rescuing those left behind: recovering and characterizing underdigested membrane and hydrophobic proteins to enhance proteome measurement depth. Anal. Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D.G. Enzymatic assembly of overlapping DNA fragments. Methods Enzymol. 2011;498:349–361. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385120-8.00015-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guss A.M., Olson D.G., Caiazza N.C., Lynd L.R. Dcm methylation is detrimental to plasmid transformation in Clostridium thermocellum. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2012;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holwerda E.K., Thorne P.G., Olson D.G., Amador-Noguez D., Engle N.L., Tschaplinski T.J., van Dijken J.P., Lynd L.R. The exometabolome of Clostridium thermocellum reveals overflow metabolism at high cellulose loading. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2014;7:155. doi: 10.1186/s13068-014-0155-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S.A. Plasmid rolling-circle replication: highlights of two decades of research. Plasmid. 2005;53:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P.P., Mi L., Morioka A.H., Yoshino K.M., Konishi S., Xu S.C., Papanek B.A., Riley L.A., Guss A.M., Liao J.C. Consolidated bioprocessing of cellulose to isobutanol using Clostridium thermocellum. Metab. Eng. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo J., Zheng T., Hon S., Olson D.G., Lynd L.R. The bifunctional alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase gene, adhE, is necessary for ethanol production in Clostridium thermocellum and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:1386–1393. doi: 10.1128/JB.02450-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynd L.R., Weimer P.J., Zyl W.H., Van, Pretorius I.S. Microbial cellulose utilization : fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:506–577. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.506-577.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z.Q., Dasari S., Chambers M.C., Litton M.D., Sobecki S.M., Zimmerman L.J., Halvey P.J., Schilling B., Drake P.M., Gibson B.W., Tabb D.L. IDPicker 2.0: improved protein assembly with high discrimination peptide identification filtering. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:3872–3881. doi: 10.1021/pr900360j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D.G., Giannone R.J., Hettich R.L., Lynd L.R. Role of the CipA scaffoldin protein in cellulose solubilization, as determined by targeted gene deletion and complementation in Clostridium thermocellum. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:733–739. doi: 10.1128/JB.02014-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D.G., Lynd L.R. 1st ed. Elsevier Inc; 2012. Transformation of Clostridium thermocellum by Electroporation, Methods in Enzymology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D.G., Lynd L.R. Computational design and characterization of a temperature-sensitive plasmid replicon for gram positive thermophiles. J. Biol. Eng. 2012:6. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D.G., Maloney M., Lanahan A.A., Hon S., Hauser L.J., Lynd L.R. Identifying promoters for gene expression in Clostridium thermocellum. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2015;2:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.meteno.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D.G., McBride J.E., Shaw A.J., Lynd L.R. Recent progress in consolidated bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012;23:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson D.G., Tripathi S.A., Giannone R.J., Lo J., Caiazza N.C., Hogsett D.A., Hettich R.L., Guss A.M., Dubrovsky G., Lynd L.R. Deletion of the Cel48S cellulase from Clostridium thermocellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17727–17732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003584107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan M., Desai S.G., Zhang Y., Stevenson D.M., Beane J., White E.A., Guerinot M.L., Lynd L.R. Characterization of 13 newly isolated strains of anaerobic, cellulolytic, thermophilic bacteria. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;27:275–280. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanek B., Biswas R., Rydzak T., Guss A.M. Elimination of metabolic pathways to all traditional fermentation products increases ethanol yields in Clostridium thermocellum. Metab. Eng. 2015:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydzak T., Lynd L.R., Guss A.M. Elimination of formate production in Clostridium thermocellum. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1644-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydzak T., McQueen P.D., Krokhin O.V., Spicer V., Ezzati P., Dwivedi R.C., Shamshurin D., Levin D.B., Wilkins J.A., Sparling R. Proteomic analysis of Clostridium thermocellum core metabolism: relative protein expression profiles and growth phase-dependent changes in protein expression. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A.J., Covalla S.F., Miller B.B., Firliet B.T., Hogsett D.A., Herring C.D. Urease expression in a Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum ethanologen allows high titer ethanol production. Metab. Eng. 2012;14:528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A.J., Jenney F.E., Adams M.W.W., Lynd L.R. End-product pathways in the xylose fermenting bacterium Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2008;42:453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A.J., Podkaminer K.K., Desai S.G., Bardsley J.S., Rogers S.R., Thorne P.G., Hogsett D.A., Lynd L.R. Metabolic engineering of a thermophilic bacterium to produce ethanol at high yield. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:13769–13774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801266105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabb D.L., Fernando C.G., Chambers M.C. MyriMatch: highly accurate tandem mass spectral peptide identificaiton by multivariate hypergeometric analysis. J. Proteome Res. 2008;6:654–661. doi: 10.1021/pr0604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverner T., Karpievitch Y.V., Polpitiya A.D., Brown J.N., Dabney A.R., Anderson G.A., Smith R.D. DanteR: an extensible R-based tool for quantitative analysis of -omics data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2404–2406. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi S.A., Olson D.G., Argyros D.A., Miller B.B., Barrett T.F., Murphy D.M., McCool J.D., Warner A.K., Rajgarhia V.B., Lynd L.R., Hogsett D.A., Caiazza N.C. Development of pyrF-based genetic system for targeted gene deletion in Clostridium thermocellum and creation of a pta mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:6591–6599. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01484-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen D., Lo J., Brown S.D., Johnson C.M., Tschaplinski T.J., Martin M., Engle N.L., van den Berg R.A., Argyros A.D., Caiazza N.C., Guss A.M., Lynd L.R. Characterization of Clostridium thermocellum strains with disrupted fermentation end-product pathways. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;40:725–734. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Lynd L.R. Quantification of cell and cellulase mass concentrations during anaerobic cellulose fermentation: Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based method with application to Clostridium thermocellum batch cultures. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:219–227. doi: 10.1021/ac020271n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng T., Olson D.G., Tian L., Bomble Y.J., Himmel M.E., Lo J., Hon S., Shaw A.J., van Dijken J.P., Lynd L.R. Cofactor specificity of the bifunctional alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase (AdhE) in wild-type and mutants of Clostridium thermocellum and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:2610–2619. doi: 10.1128/JB.00232-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Olson D.G., Lanahan A.A., Tian L., Murphy S.J.-L., Lo J., Lynd L.R. Physiological roles of pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase and pyruvate formate-lyase in Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2015;8:138. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0304-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material