Abstract

Purpose of review

We will briefly review the classification of shock and the hallmark features of each sub-type. Available modalities for monitoring shock patients will be discussed, along with evidence supporting the use, common pitfalls and practical considerations of each method.

Recent findings

As older, invasive monitoring methods such as the pulmonary artery catheter have fallen out of favor, newer technologies for cardiac output estimation, echocardiography, and non-invasive tests such as passive leg raising have gained popularity. Newer forms of minimally invasive or noninvasive monitoring (such as pulse-contour analysis or chest bioreactance) show promise but will need further investigation before they are considered validated for practical use. There remains no “ideal” test or standard of care for cardiopulmonary monitoring of shock patients.

Summary

Shock and its underlying etiologies are potentially reversible causes of morbidity and mortality if appropriately diagnosed and managed. Older methods of invasive monitoring have significant limitations but can still be critical for managing shock in certain patients and settings. Newer methods are easier to employ, but further validation is needed. Multiple modalities along with careful clinical assessment are often useful in distinguishing shock sub-types. Best practice standards for monitoring should be based on institutional expertise.

Keywords: hemodynamic monitoring, shock, pulmonary artery catheter, non-invasive cardiac monitoring

I. Introduction

Shock is an important cause of intensive care unit admissions and mortality even with significant advances in medical care. The goal of this review is to provide an updated framework for monitoring these patients. We will briefly summarize the current classification of shock, including distributive, cardiogenic, hypovolemic and obstructive shock, and review various modalities to diagnosis and monitor shock states. Practical considerations and common pitfalls of cardiopulmonary monitoring in the intensive care unit will be discussed.

II. Shock definition and epidemiology

Shock is a state of cellular hypoxia due to an imbalance of oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption. This is most often due a reduction in relative tissue perfusion with circulatory failure. Cardiac output (CO) and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) proportionally determine blood pressure. In turn, CO is a product of heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV). Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) is proportional to vessel length and blood viscosity, while it is inversely proportional to vessel diameter. Shock can arise if any of these variables are changed such that CO or SVR is decreased. Shock can also occur if tissue is unable to utilize oxygen appropriately or if oxygen carrying capacity is not adequate, as can occur with mitochondrial dysfunction or poisoning with carbon monoxide, respectively. Clinically, shock can manifest as a decompensated patient with evidence of end organ failure (e.g., altered mental status, hypotension, or anuria) or more occultly without frank organ dysfunction (e.g., lactic acidosis, mild decreases in blood pressure), referred to as cryptic or compensated shock.

Shock is most commonly classified into four different underlying subtypes with different pathophysiologies: distributive, cardiogenic, hypovolemic and obstructive. Distinguishing features of these four shock states are described in Table 1. Mixed shock, with characteristics of more than one of these subtypes, can also occur. The relative frequency of each type of shock at a given institution depends on the population served (e.g., Level I trauma centers will see a higher level of hemorrhagic shock (1)). A large (n = 1679), multicenter randomized clinical trial (RCT) (the SOAP II trial) found distributive shock was most common (64%), followed by hypovolemic (16%), cardiogenic (15%), and obstructive (2%) shock among all comers with circulatory failure (2).

Table 1.

Distinguishing features of different etiologies of shock

| Exam findings | CO | PAWP | SVR | SvO2 | Potential lab findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive | Warm limbs, dry mucus membranes, flat neck veins, febrile | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | >65% | Elevated lactate, positive cultures, leukocytosis |

| Cardiogenic | Cool limbs, leg edema, lung crackles bilaterally, jugular venous distension | Decreased | Increased | Increased | <65% | Elevated lactate, elevated troponins, high brain natriuretic protein |

| Hypovolemic | Cool limbs, dry mucus membranes, flat neck veins | Decreased | Decreased | Increased | <65% | Elevated lactate |

| Obstructive | Cool limbs, lack of breath sounds, distant heart sounds, jugular venous distension | Decreased | Decreased (increased in tamponade) | Increased | <65% | Elevated lactate |

CO=cardiac output; PAWP=pulmonary artery wedge pressure; SVR=systemic vascular resistance; SvO2 = mixed venous oxygen saturation

The mortality for each type of shock varies widely. Septic shock is associated with an in-hospital mortality of 30–54% (3, 4), although death rates as low as 19% have been reported in recently completed RCTs (5). In-hospital mortality from cardiogenic shock can range from 50–80% (6, 7). Outcomes for distributive shock also vary significantly with etiology, with mortality rates as high as 80–90% from traumatic hemorrhage and as low as 19% from shock due to gastrointestinal bleeding (8, 9). Hypovolemic shock patients tend to do well, with mortality rates under 10% (10). Obstructive shock includes disparate underlying conditions (i.e., cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolism), occurs less frequently and is less well studied, making outcome estimates difficult (11, 12).

IIa. Distributive Shock

Distributive shock is defined by severe vasodilatation of the peripheral vasculature and includes septic, anaphylactic, drug or toxin-induced, and neurogenic etiologies. Sepsis is the most common form and is attributable to dysregulation of the host response to infection and defined most recently as the use of vasopressors in the setting of a rising lactate despite fluid resuscitation (3). A noninfectious but overtly robust systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) can mimic septic physiology, as typified by burns or pancreatitis, among other causes. Anaphylaxis is mediated by a severe allergic reaction due to the release of immunoglobulin E and is usually accompanied by bronchospasm. Neurogenic shock is seen in severe brain or spinal cord injury. These causes lead to increased CO (via increased HR or SV) in response to tissue hypoperfusion from extreme vasodilation and increased permeability (low SVR) (Table 1).

IIb. Cardiogenic Shock

This form of shock is defined by a primary intracardiac cause such as arrhythmia, ischemia, valvular dysfunction, or cardiomyopathy leading to decreased CO. Cool extremities due to peripheral vasoconstriction and increased SVR in an attempt to maintain perfusion pressures characterize cardiogenic shock, as well as other findings such as elevated neck veins, rales from pulmonary edema, and leg edema from venous pooling. If the shock is more subacute or cryptic, then the extremities may be warm.

IIc. Hypovolemic Shock

Reduced CO also occurs in hypovolemic shock, however this is due to reduced intravascular volume and low preload. Major causes include significant hemorrhage or volume depletion due to fluid losses from the kidneys (diuresis or salt wasting), the gastrointestinal system (vomiting or diarrhea), or the skin (severe burns or heat stroke). Both hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic shock should lead to compensatory tachycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction in order to improve CO and perfusion pressure.

IId. Obstructive Shock

This is a heterogeneous group of processes all with low CO due to an obstruction to forward flow. Pulmonary vascular causes that lead to right ventricle (RV) failure and in turn low CO include pulmonary embolism (thrombus, air, foreign body, tumor or amniotic fluid) or acute or subacute worsening of chronic pulmonary hypertension. Similarly, inadequate filling of the LV from acute tamponade, constrictive pericarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy, or tension pneumothorax can lead to precipitous falls in CO. Obstructive shock can mirror cardiogenic shock on clinical exam due to peripheral vasoconstriction, increased jugular venous pressure, and tachycardia but is notable for the absence of pulmonary rales.

With such a diverse number of etiologies of shock, causes may present similarly or occur simultaneously. Diagnosing the underlying pathophysiology is of paramount importance to prevent significant end organ failure and death. Once treatment has begun, monitoring for the improvement of shock as well as for the unmasking of other contributors is critical, as the treatments can vary greatly and run in opposition to each other.

III. Monitoring

IIIa. Blood pressure monitoring

Blood pressure is perhaps the oldest form of perfusion monitoring outside of the physical exam. It is monitored either statically by sphygmomanometers at the extremities or continuously via arterial catheters. Organ systems each autoregulate their own blood flow and as such there can be no absolute measurement of blood pressure that ensures or precludes adequate individual organ perfusion, hence the need for other modalities that are used in tandem. Generally, a mean arterial pressure (MAP) less than 65 mm Hg is considered pathological, and studies have shown that MAPs above this threshold were not associated with evidence of hypoperfusion or mortality (13). Lower targets and controlled hypotension (maintaining systolic blood pressure > 70 mm Hg) may be preferable in trauma patients with hemorrhagic shock, although this approach remains controversial (14). A recent multicenter RCT comparing a MAP target of either 80–85 mm Hg versus 65–70 mm Hg showed no differences in survival at 90 days in patients with septic shock, though the higher target led to significantly less use of renal replacement therapy in patients with chronic systemic hypertension but also a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation (15).

IIIb. Venous oxygen saturation monitoring

Mixed venous oxygen saturation (MvO2 or SvO2) is the percentage saturation of hemoglobin in the pulmonary artery measured from the distal tip of a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC). A decreased SvO22 is a sensitive marker of decreased CO. The SvO2 drops in cardiogenic shock because the transit time of the blood in the peripheral vasculature is prolonged (CO is measured in liters per minute through a relatively fixed composite distance for that volume of blood to travel). Conversely, in distributive shock, the SvO2 is usually greater than 70%, due to a failure of the peripheral tissues to extract oxygen and microcirculatory shunt; very high values (>90%) have been associated with worse outcomes (16). Ventriculoarterial uncoupling with concurrent cardiac dysfunction can also occur in septic shock and lead to low SvO2 in some cases (17).

The major downside of SvO2 is that it can only be obtained by placement of a PAC, the limitations of which are discussed below. Central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) can be measured from a venous blood gas drawn from any central venous catheter (preferably in the upper extremities), so it is often used as a practical substitute. Multiple studies have questioned the reliability of ScvO2 to predict SvO2 (even allowing for + 10% error) (18–21). ScvO2 is generally regarded as not necessarily equivalent to SvO2 but potentially useful for trending changes with therapy. The degree and direction of changes in ScvO2 do correlate with SvO2 and a fiberoptic device for continuous ScvO2 monitoring was developed for this purpose (22). While monitoring central venous oxygen saturations may be useful for diagnosing causes of shock and for trending values in individual patient(s), as a treatment target normalizing SvO2 does not improve morbidity or mortality in critically ill patients (5, 23). Peripheral venous blood gases have no utility in differentiating shock subtypes.

IIIc. Measures of central venous pressure

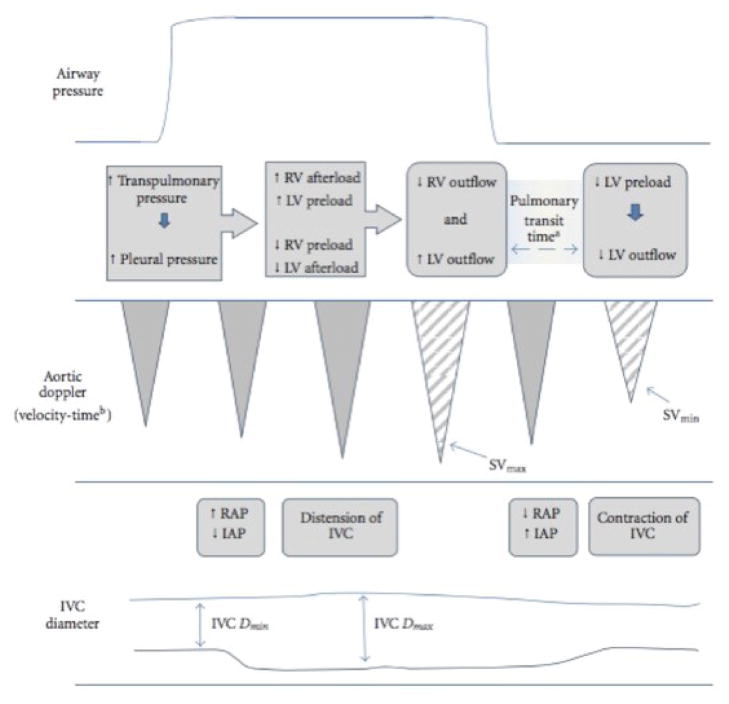

Central venous pressure (CVP) has a normal range of 5–7 mm Hg in an adult spontaneously breathing patient while supine. The CVP is elevated in obstructive or cardiogenic shock, while it is decreased in septic or hypovolemic shock. CVP can be indirectly measured by the clinical assessment of jugular venous pressure or on ultrasound evaluation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) (see Echocardiography). It can be measured directly via a simple manometer attached to a central venous catheter. The transducer should be aligned with the patient’s mid chest at the mid-axillary line, at the level of the left atrium. A common pitfall in CVP measurement is not accounting for the effect of positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) with positive pressure ventilation (Figure 1) (24). PEEP may have direct effects on cardiac preload, afterload, and ventricular compliance. PEEP can falsely elevate CVP measurements depending on pulmonary compliance and intrathoracic cavity pressure swings by creating resistance to flow.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of how positive pressure ventilation may affect cardiac loading conditions and measures of cardiac output. Reproduced with permission from Mandeville JC and Colebourn CL (24). RV=right ventricle; LV=left ventricle; SV=stroke volume; RAP=right atrial pressure; IAP=intra-abdominal pressure; IVC=inferior vena cava

Direct measurement of CVP has the benefit of providing “hard” numbers to compare as the patient’s condition changes, but requires a central line. CVP has traditionally been used to guide fluid management, but it is not clear that CVP is a precise or accurate measure in the critically ill or that measuring CVP improves outcomes. A systematic review confirmed that there is no relationship between CVP and circulating blood volume, nor does the CVP predict fluid responsiveness (25). Because of the lack of data supporting its use combined with the challenges related to assuring the accuracy of CVP in critically ill patients many physicians argue the CVP should no longer be used to guide management.

IIId. Cardiac echocardiography and ultrasonography

Cardiac echocardiography is often useful in the evaluation of patients in shock, providing information about diagnosis (e.g., assessing for valvular disease, changes in wall motion from acute coronary syndrome, acute cor pulmonale in pulmonary embolism, and pericardial effusion with tamponade) and capturing serial changes in contractile function. Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach and a recent guideline on the appropriate use of point-of-care ultrasound and echocardiography in critically ill patients has been issued (26–29). Echocardiography may be limited by poor image acquisition due to body habitus as well as operator and interpreter experience.

Standard 2-dimensional ultrasound can provide real time assessment of dynamic changes in the IVC which correlate with direct measurement of CVP and are used clinically to predict stroke volume responsiveness to fluid boluses based on the diameter and collapsibility of the cava for a patient in shock (24, 30). The use of IVC diameter to predict stroke volume responsiveness has only been validated in patients who are paralyzed and mechanically ventilated (24). While this monitoring modality may prove useful in a broader range of shock patients, caution should be used when interpreting results in the setting of chronic severe lung disease and settings in which large intrathoracic and intraabdominal pressure swings occur, for example. The superior vena cava may be similarly assessed by subtracting the diameter at inspiration (minimal width) from the diameter at expiration (maximal width) then dividing by the diameter at expiration (31). This number is expressed as a collapsibility index, with values greater than 36% correlating to an increased cardiac index following volume expansion (32). Unfortunately, SVC diameter requires transesophageal echocardiogram, limiting its’ use, but since the SVC is entirely intrathoracic it is not confounded by pressures in other spaces. The common femoral vein diameter has been compared to CVP for noninvasive prediction of fluid status as well, but appears less reliable and requires further study (33). Ultrasound methods are limited by operator experience. Body habitus and abdominal processes can also compromise image quality.

IIIe. Pulmonary Artery Catheter

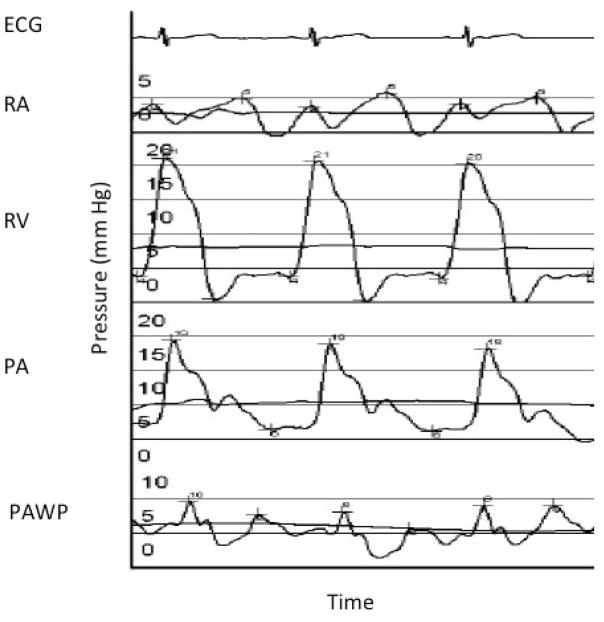

Also known as the Swan-Ganz catheter, the PAC has had perhaps the most storied journey as a hemodynamic monitoring modality in critical care. This invasive method involves placement of a central venous catheter into the internal jugular vein. As the flow-directed catheter is advanced, waveforms are tracked that reveal the location of the catheter tip as well as the pressures associated with that particular part of the heart or pulmonary vasculature (Figure 2). These pressures can then be used to help differentiate between different forms of shock, but require correct interpretation.

Figure 2.

Pressure tracings and anticipated waveforms during right heart catheterization. X-axis is time; Y-axis is pressure in mm Hg. ECG = electrocardiogram; RA = right atrium, RV = right ventricle; PA = pulmonary artery; PAWP = pulmonary artery wedge pressure.

A complete set of hemodynamic data includes the direct measurement of CVP (discussed above), right atrial pressure, right ventricular pressures, pulmonary artery pressures, pulmonary artery occlusion or wedge pressure (PAWP), and cardiac output by the thermodilution or Fick method (requiring actual measurement of oxygen consumption and the arteriovenous oxygen concentration difference). Additional parameters such as the indirect Fick cardiac output (based on assumed values of metabolism/oxygen consumption, arterial saturation, and body surface area that are unlikely to be valid in the critically ill), systemic vascular and pulmonary vascular resistance are calculated. A detailed discussion of PAC measurements and waveform interpretation is beyond the scope of this review; an excellent one is provided by Nishimura and Carbello (34).

As an estimate of left heart filling pressures, the PAWP can help to differentiate between cardiogenic shock and distributive or hypovolemic shock, as it will be elevated in the former and decreased in the latter (Table 2). It is notable that the wedge pressure can only be done intermittently and should be measured at end-expiration in zone 3 (mean pulmonary arterial pressure > mean pulmonary capillary pressure > alveolar pressure) conditions. The measurement of PAWP assumes no obstruction to flow between the left atrium and the left ventricle and normal ventricular compliance (i.e., it is not a measurement of volume), and can be affected by intrathoracic pressure changes, valvular disease, high levels of PEEP, and pulmonary compliance. As with measuring CVP, common mistakes made in PAC measurements and interpretation include not zeroing the transducer, failure to measure pressures correctly at end-expiration and to account for the effects of positive pressure (the nadir of the waveform in mechanically ventilated patients, the crest of the waveform in spontaneously breathing patients), all of which can lead to erroneous conclusions (Figure 1).

A large prospective cohort study found that the use of a PAC to guide shock management was associated with a significant increase in mortality (odds ratio [OR] 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] of 1.03–1.49), an increase in ICU length of stay, and increased costs (35). A second large RCT in high-risk surgical patients undergoing urgent or major surgery cared for postoperatively in the ICU demonstrated no benefit to PAC-guided therapy versus standard care, with a higher rate of complications among those who were randomized to PAC (36). While these and other studies have failed to demonstrate a benefit of the PAC in populations of critically ill patients (23, 37–39), invasive hemodynamic monitoring is the gold standard against which other less invasive methods are compared. The PAC remains useful in certain patients in which intravascular volume status and cardiac filling pressures are uncertain, in the setting of mixed shock, and in select patients with preexisting pulmonary vascular or cardiac conditions. Complications include infection of the line, arrhythmias due to irritation of myocardium, and pulmonary artery rupture. The rate of complications has decreased over time with an adverse event rate of around 4% generally and 1% in experienced centers (40, 41).

IIIf. Passive leg raising

In light of the lack of evidence supporting the routine use of invasive hemodynamic monitoring in shock patients, there has been increasing interest in the use of less invasive methods including point-of-care ultrasound (discussed above) and wholly non-invasive methods such as passive leg raising (PLR). PLR is done to determine which patients will have an increase in CO with a fluid challenge. The method involves raising the legs of a supine patient to 45 degrees to increase systemic pressure which will in turn increase venous return, and, in a heart that is still preload dependent, lead to an increase in CO detected by changes in pulse pressure or caval collapse (42, 43). This method may be helpful because it is a “dry run” fluid bolus that may save the patient an unnecessary fluid volume. This method has been investigated in multiple studies and systematic reviews, and it has been found to reliably increase CO (measured by various correlates or directly by thermodiluation) by 10–30% in fluid responsive patients with a pooled sensitivity between 86–88% (42, 44–47). A recent meta-analysis demonstrated similar diagnostic power between mechanically ventilated and spontaneously breathing patients (46). However, there are limitations which include the inability to use this method in patients with leg amputations, some urologic or gynecologic surgeries, and head trauma patients or patients with intracranial hypertension (42, 46). Its use is not yet widespread in the United States, but it may be of increasing value as further studies clarify and validate the role of PLR in shock management.

IIIg. Minimally or noninvasive cardiac output monitoring devices

Devices for minimally or noninvasive cardiac output monitoring using arterial pressure tracings and pulse-contour analysis (e.g., FloTrac, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) or chest bioreactance (i.e., Non-invasive cardiac output monitoring [NICOM], Cheetah Medical, Inc, Wilmington, DE) have been developed. Pulse waveform analysis relies on estimates of stroke volume and detected changes in aortic compliance or impedence and may or may not be directly calibrated. NICOM is based upon the principle of bioreactance measured from electrodes placed on the chest, whereby a change in conductivity of a low magnitude current correlates to a change in intrathoracic blood flow (48, 49). Early studies have shown promising correlation between these less invasive technologies and CO measured by thermodilution in critically ill patients, however further validation is required before widespread use in shock states can be recommended (49–51).

IV. Conclusion

In summary, shock continues to be an important part of potentially reversible morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. The ability to correctly diagnose the type of shock, as well as monitor the efficacy of treatment, is of paramount importance for improving outcomes. Although the pathophysiology for these patients is often complex, the correct use of these modalities (often in combination) can help clarify and potentially simplify the underlying etiologies of shock. Current literature suggests there is no one best monitoring modality for shock patients as all may be subject to measurement error and results may be directly affected by patient pathophysiology and interactions with mechanical ventilation. The limitations of each method should be kept in mind as well as the overall clinical picture when determining the reliability of an individual parameter. Local expertise and comfort with specific measures may dictate preference, given the lack of data demonstrating superiority of one method over another. Future advances in shock management are likely to affect the usefulness of the modalities discussed here. Therefore, it is important to stay up to date on emerging technologies while maintaining a grasp on older forms of monitoring in an ever-evolving field.

Key points.

While the degree and direction of changes in central venous oxygen saturation correlates with changes in mixed venous oxygen saturation, single values in isolation are unlikely to accurately reflect cardiac output and treatment aimed at normalizing central venous oxygen saturation does not improve outcomes.

Central venous pressure has historically been used to predict fluid responsiveness, however current literature does not support its use for this purpose as there appears to be no correlation with circulating blood volume or fluid responsiveness.

Bedside echocardiography should be integrated into care for patients in shock, both for diagnostic purposes and for evaluating potential fluid responsiveness, but can be limited by patient factors and provider skill level.

The pulmonary artery catheter has historically provided the gold standard against which newer monitoring modalities are compared, but its use in shock does not improve outcomes and may increase complications, so it is not recommended for routine use.

Passive leg raising provides a reliable and noninvasive way to assess for volume responsiveness when done correctly.

Emerging minimally or noninvasive cardiac output monitoring devices show empirical promise but require further validation before they can be routinely recommended.

Acknowledgments

C.E.V. receives funding from an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103652), the American Heart Association (11FTF7400032), and the Deans Award (14675) from the Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Financial support or sponsorship

The authors did not receive financial sponsorship related to this article.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

C.E.V. has served as a consultant for Bayer Pharmaceuticals and United Therapeutics. Her institution has received grant funding from Actelion.

References

- 1.Jones AE, Craddock PA, Tayal VS, Kline JA. Diagnostic accuracy of left ventricular function for identifying sepsis among emergency department patients with nontraumatic symptomatic undifferentiated hypotension. Shock. 2005;24:513–517. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000186931.02852.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, Madl C, Chochrad D, Aldecoa C, Brasseur A, Defrance P, Gottignies P, Vincent JL SOAP II Investigators. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:779–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **3.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. This article updates the definitions and clinical criteria of sepsis and septic shock with consensus statements. This article is important in that it supports use of a bedside clinical score, the quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment (qSOFA), in order to quickly identify those with infection and high mortality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ProCESS Investigators. Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT, Barnato AE, Weissfeld LA, Pike F, Terndrup T, Wang HE, Hou PC, LoVecchio F, Filbin MR, Shapiro NI, Angus DC. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1683–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochman JS, Boland J, Sleeper LA, Porway M, Brinker J, Col J, Jacobs A, Slater J, Miller D, Wasserman H. Current spectrum of cardiogenic shock and effect of early revascularization on mortality. Results of an International Registry. SHOCK Registry Investigators. Circulation. 1995;91:873–881. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ARISE Investigators, ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. Peake SL, Delaney A, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Cameron PA, Cooper DJ, Higgins AM, Holdgate A, Howe BD, Webb SA, Williams P. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1496–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, Marshall J, Martin C, Pagliarello G, Tweeddale M, Schweitzer I, Yetisir E. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutierrez G, Reines HD, Wulf-Gutierrez ME. Clinical review: hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care. 2004;8:373–381. doi: 10.1186/cc2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younes RN, Yin KC, Amino CJ, Itinoshe M, Rocha e Silva M, Birolini D. Use of pentastarch solution in the treatment of patients with hemorrhagic hypovolemia: randomized phase II study in the emergency room. World J Surg. 1998;22:2–5. doi: 10.1007/s002689900340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *11.Becattini C, Agnelli G, Lankeit M, Masotti L, Pruszczyk P, Casazza F, Vanni S, Nitti C, Kamphuisen P, Vedovati MC, De Natale MG, Konstantinides S. Acute pulmonary embolism: mortality prediction by the 2014 European Society of Cardiology risk stratification model. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:780–786. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00024-2016. This article assessed the 2014 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) risk stratification model for patients with acute pulmonary embolism (which includes Pulmonary Embolism Severity index (PESI score), right ventricular dysfunction and troponins) to determine if mortality is correctly predicted. It was shown that the 2014 ESC model appropriately groups patients with high mortality into the high risk group while providing acceptable negative predictive value for low risk patients (which in turn reduced testing, including troponins and echocardiography) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueras J, Barrabes JA, Lidon RM, Sambola A, Baneras J, Palomares JR, Marti G, Dorado DG. Predictors of moderate-to-severe pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and electromechanical dissociation in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1291–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeDoux D, Astiz ME, Carpati CM, Rackow EC. Effects of perfusion pressure on tissue perfusion in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2729–2732. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreiber MA, Meier EN, Tisherman SA, Kerby JD, Newgard CD, Brasel K, Egan D, Witham W, Williams C, Daya M, Beeson J, McCully BH, Wheeler S, Kannas D, May S, McKnight B, Hoyt DB ROC Investigators. A controlled resuscitation strategy is feasible and safe in hypotensive trauma patients: results of a prospective randomized pilot trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:687–95. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000600. discussion 695–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asfar P, Meziani F, Hamel JF, Grelon F, Megarbane B, Anguel N, Mira JP, Dequin PF, Gergaud S, Weiss N, Legay F, Le Tulzo Y, Conrad M, Robert R, Gonzalez F, Guitton C, Tamion F, Tonnelier JM, Guezennec P, Van Der Linden T, Vieillard-Baron A, Mariotte E, Pradel G, Lesieur O, Ricard JD, Herve F, du Cheyron D, Guerin C, Mercat A, Teboul JL, Radermacher P SEPSISPAM Investigators. High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1583–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope JV, Jones AE, Gaieski DF, Arnold RC, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI Emergency Medicine Shock Research Network (EMShockNet) Investigators. Multicenter study of central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO(2)) as a predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:40–46. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarracino F, Ferro B, Morelli A, Bertini P, Baldassarri R, Pinsky MR. Ventriculoarterial decoupling in human septic shock. Crit Care. 2014;18:R80. doi: 10.1186/cc13842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dueck MH, Klimek M, Appenrodt S, Weigand C, Boerner U. Trends but not individual values of central venous oxygen saturation agree with mixed venous oxygen saturation during varying hemodynamic conditions. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:249–257. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chawla LS, Zia H, Gutierrez G, Katz NM, Seneff MG, Shah M. Lack of equivalence between central and mixed venous oxygen saturation. Chest. 2004;126:1891–1896. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards JD, Mayall RM. Importance of the sampling site for measurement of mixed venous oxygen saturation in shock. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1356–1360. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199808000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin C, Auffray JP, Badetti C, Perrin G, Papazian L, Gouin F. Monitoring of central venous oxygen saturation versus mixed venous oxygen saturation in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18:101–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01705041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinhart K, Kuhn HJ, Hartog C, Bredle DL. Continuous central venous and pulmonary artery oxygen saturation monitoring in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1572–1578. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2337-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gattinoni L, Brazzi L, Pelosi P, Latini R, Tognoni G, Pesenti A, Fumagalli R. A trial of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. SvO2 Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1025–1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandeville JC, Colebourn CL. Can transthoracic echocardiography be used to predict fluid responsiveness in the critically ill patient? A systematic review. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:513480. doi: 10.1155/2012/513480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marik PE, Baram M, Vahid B. Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? A systematic review of the literature and the tale of seven mares. Chest. 2008;134:172–178. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jardin F, Fourme T, Page B, Loubieres Y, Vieillard-Baron A, Beauchet A, Bourdarias JP. Persistent preload defect in severe sepsis despite fluid loading: A longitudinal echocardiographic study in patients with septic shock. Chest. 1999;116:1354–1359. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieillard-Baron A, Prin S, Chergui K, Dubourg O, Jardin F. Echo-Doppler demonstration of acute cor pulmonale at the bedside in the medical intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1310–1319. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200202-146CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *28.Gray R, Baldwin F, Bruemmer-Smith S. Diagnostic echocardiography in an unstable intensive care patient. Echo Res Pract. 2015;2:K11–6. doi: 10.1530/ERP-14-0040. This case report highlights the diagnostic usefulness of echocardiography in an unstable patient in the intensive care unit. It highlights the benefits of adding echocardiography to other testing, including computed tomography and electrocardiograms, in order to improve diagnostic accuracy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Levitov A, Frankel HL, Blaivas M, Kirkpatrick AW, Su E, Evans D, Summerfield DT, Slonim A, Breitkreutz R, Price S, McLaughlin M, Marik PE, Elbarbary M. Guidelines for the Appropriate Use of Bedside General and Cardiac Ultrasonography in the Evaluation of Critically Ill Patients-Part II: Cardiac Ultrasonography. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1206–1227. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001847. This article established evidenced based guidelines for use of ultrasonography (including echocardiography) at the bedside in the intensive care unit. This article is important in the process of beginning integration of ultrasonography in usual practice in the intensive care unit. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charron C, Caille V, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Echocardiographic measurement of fluid responsiveness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:249–254. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000224870.24324.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vieillard-Baron A, Augarde R, Prin S, Page B, Beauchet A, Jardin F. Influence of superior vena caval zone condition on cyclic changes in right ventricular outflow during respiratory support. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1083–1088. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vieillard-Baron A, Chergui K, Rabiller A, Peyrouset O, Page B, Beauchet A, Jardin F. Superior vena caval collapsibility as a gauge of volume status in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1734–1739. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Malik A, Akhtar A, Saadat S, Mansoor S. Predicting Central Venous Pressure by Measuring Femoral Venous Diameter Using Ultrasonography. Cureus. 2016;8:e893. doi: 10.7759/cureus.893. This article identified a positive correlation of femoral venous diameter to the central venous pressure, suggesting a possible alternate method using ultrasonography to predict fluid responsiveness. This article can form the basis for further studies that can look at clinical outcomes when using femoral venous diameter to predict fluid responsiveness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishimura RA, Carabello BA. Hemodynamics in the cardiac catheterization laboratory of the 21st century. Circulation. 2012;125:2138–2150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connors AF, Jr, Speroff T, Dawson NV, Thomas C, Harrell FE, Jr, Wagner D, Desbiens N, Goldman L, Wu AW, Califf RM, Fulkerson WJ, Jr, Vidaillet H, Broste S, Bellamy P, Lynn J, Knaus WA. The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators. JAMA. 1996;276:889–897. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.11.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandham JD, Hull RD, Brant RF, Knox L, Pineo GF, Doig CJ, Laporta DP, Viner S, Passerini L, Devitt H, Kirby A, Jacka M Canadian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group. A randomized, controlled trial of the use of pulmonary-artery catheters in high-risk surgical patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:5–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajaram SS, Desai NK, Kalra A, Gajera M, Cavanaugh SK, Brampton W, Young D, Harvey S, Rowan K. Pulmonary artery catheters for adult patients in intensive care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2):CD003408. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003408.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper AB, Doig GS, Sibbald WJ. Pulmonary artery catheters in the critically ill. An overview using the methodology of evidence-based medicine. Crit Care Clin. 1996;12:777–794. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Schoenfeld D, Wiedemann HP, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF, Jr, Hite RD, Harabin AL. Pulmonary-artery versus central venous catheter to guide treatment of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2213–2224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyd KD, Thomas SJ, Gold J, Boyd AD. A prospective study of complications of pulmonary artery catheterizations in 500 consecutive patients. Chest. 1983;84:245–249. doi: 10.1378/chest.84.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoeper MM, Lee SH, Voswinckel R, Palazzini M, Jais X, Marinelli A, Barst RJ, Ghofrani HA, Jing ZC, Opitz C, Seyfarth HJ, Halank M, McLaughlin V, Oudiz RJ, Ewert R, Wilkens H, Kluge S, Bremer HC, Baroke E, Rubin LJ. Complications of right heart catheterization procedures in patients with pulmonary hypertension in experienced centers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2546–2552. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boulain T, Achard JM, Teboul JL, Richard C, Perrotin D, Ginies G. Changes in BP induced by passive leg raising predict response to fluid loading in critically ill patients. Chest. 2002;121:1245–1252. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caille V, Jabot J, Belliard G, Charron C, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Hemodynamic effects of passive leg raising: an echocardiographic study in patients with shock. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1239–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1067-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monnet X, Marik P, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising for predicting fluid responsiveness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1935–1947. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *45.Monnet X, Rienzo M, Osman D, Anguel N, Richard C, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising predicts fluid responsiveness in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1402–1407. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215453.11735.06. This article used a meta-analysis to compare 21 studies that evaluated passive leg raises (PLR) for usefulness of predicting fluid responsiveness, as measured by increased cardiac ouput or increased pulse pressure. It confirmed that PLR reliably predicts a response in cardiac output to a fluid challenge, however the pulse pressure has poor sensitivity for fluid responsiveness. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *46.Cherpanath TG, Hirsch A, Geerts BF, Lagrand WK, Leeflang MM, Schultz MJ, Groeneveld AB. Predicting Fluid Responsiveness by Passive Leg Raising: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 23 Clinical Trials. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:981–991. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001556. This article used a meta-analysis to compare 23 studies that evaluated passive leg raises (PLR) for effectiveness in predicting fluid responsiveness. This study showed PLR is useful regardless of mode of ventilation, fluid used, or measurement technique, though pulse pressure was less sensitive than variables that assess change in flow, such as cardiac output. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **47.Vignon P, Repesse X, Begot E, Leger J, Jacob C, Bouferrache K, Slama M, Prat G, Vieillard-Baron A. Comparison of Echocardiographic Indices Used to Predict Fluid Responsiveness in Ventilated Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0844OC. This article compared different echocardiographic measures to determine which would best predict fluid responsiveness. It showed that the blood velocity in the left ventricular outflow tract had the best sensitivity for fluid responsivness, however the change in the superior vena cava diameter had the best specificity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bendjelid K, Marx G, Kiefer N, Simon TP, Geisen M, Hoeft A, Siegenthaler N, Hofer CK. Performance of a new pulse contour method for continuous cardiac output monitoring: validation in critically ill patients. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:573–579. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Squara P, Denjean D, Estagnasie P, Brusset A, Dib JC, Dubois C. Noninvasive cardiac output monitoring (NICOM): a clinical validation. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1191–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vincent JL, Rhodes A, Perel A, Martin GS, Della Rocca G, Vallet B, Pinsky MR, Hofer CK, Teboul JL, de Boode WP, Scolletta S, Vieillard-Baron A, De Backer D, Walley KR, Maggiorini M, Singer M. Clinical review: Update on hemodynamic monitoring--a consensus of 16. Crit Care. 2011;15:229. doi: 10.1186/cc10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Compton FD, Zukunft B, Hoffmann C, Zidek W, Schaefer JH. Performance of a minimally invasive uncalibrated cardiac output monitoring system (Flotrac/Vigileo) in haemodynamically unstable patients. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:451–456. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]