Abstract

Connect to Protect (C2P), a 10-year community mobilization effort, pursued the dual aims of creating communities competent to address youth’s HIV-related risks and removing structural barriers to youth health. We used Community Coalition Action Theory (CCAT) to examine the perceived contributions and accomplishments of 14 C2P coalitions. We interviewed 318 key informants, including youth and community leaders, to identify the features of coalitions’ context and operation that facilitated and undermined their ability to achieve structural change and build communities’ capability to manage their local adolescent HIV epidemic effectively. We coded the interviews using an a priori coding scheme informed by CCAT and scholarship on AIDS-competent communities. We found community mobilization efforts like C2P can contribute to addressing the structural factors that promote HIV-risk among youth and to community development. We describe how coalition leadership, collaborative synergy, capacity building, and local community context influences coalitions’ ability to successfully implement HIV-related structural change, demonstrating empirical support for many of CCAT’s propositions. We discuss implications for how community-mobilization efforts might succeed in laying the foundation for an AIDS-competent community.

Key words: HIV/AIDS, youth and adolescents, coalitions, AIDS competence, structural change, community capacity

Introduction

Despite decades of progress in addressing the HIV epidemic, we possess too few stories of HIV prevention’s success in curbing the epidemic’s spread among youth. Evidence-supported interventions targeting youth are available, but their implementation is not sufficiently widespread to benefit the majority of young people. Moreover, evidence-supported interventions for youth are most often individual-level interventions that address only select aspects of individual HIV risk (Baggaley, Armstrong, & Dodd, Ngoksin, & Krug, 2015). These interventions leave the social environment in which youth initially develop patterns of risky behavior unchanged. Adequately reducing HIV risk among youth requires comprehensive approaches that incorporate individually-focused interventions designed to equip youth with HIV prevention knowledge and skills and structurally-focused interventions designed to change the features of the social settings in which youth’s risk incubates (Baggaley et al., 2015).

According to Parkhurst (2014), structural factors supporting HIV risk can be conceptualized in two ways. Structural factors may be understood as features of the social environment that drive risk. Poverty, for example, is a well-documented driver of myriad health problems and is a structural factor widely implicated in HIV disease (Pellowski, Kalichman, Matthews, & Adler, 2013). Structural factors may also be framed in mediational terms. Mediational conceptualizations emphasize the social and environmental mechanisms that operate at various ecological levels through which structural factors shape behaviors linked to acquisition of disease and facilitate or impede individuals’ capability to engage in self-protective behaviors. For example, poverty may lead to food insecurity which may in turn lead to engaging in sex work or exchanging sex for food, increasing opportunities for HIV infection.

Parkhurst is among many scholars who have challenged the HIV field to invest in structural approaches to HIV prevention (Blankenship, Bray, & Merson, 2000; Gupta, Parkhurst, Ogden, Aggleton, & Mahal, 2008; Piot, Bartos, Larson, Zewdie, & Mane, 2008). He suggests that combining conceptualizations of structural factors as drivers and mediators best provides for the development of structural interventions that are directed far enough “upstream” to have enduring effects on multiple risk mechanisms and that also contribute to the development of AIDS-resilient or AIDS-competent settings. AIDS-competent communities are characterized as places in which: the appropriate knowledge and skills exist to problem-solve and plan; there is ongoing communication and dialogue among relevant actors and partnerships bridge across sectors; there is local ownership of HIV as an urgent problem; the community is confident of its strengths; and, a sense of solidarity to address HIV exists (Campbell, Nair & Maimane, 2007; Reed & Miller, 2013).

Structural interventions that accomplish the aim of creating communities competent to address youth’s HIV-related risks are sorely needed (Prado, Lightfoot & Brown, 2013). HIV diagnoses among people 13 to 24 years old increased 38% over the 10-year period from 2002 to 2011 (Johnson et al., 2014). This trend contrasted markedly with a 33% decrease in the proportion of the overall population diagnosed with HIV over the same period. As of 2015, nearly 40% of new HIV infections in the U.S. occurred among persons under the age of 29. The impact of the HIV epidemic on youth has been especially devastating for young gay and bisexual males, transgendered youth, and youth of color (Baggaley et al., 2015; Bekker, Johnson, Wallace, & Hosek, 2015; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Youth are less likely to know their HIV status and, among those who are HIV infected, less successful in linking to HIV medical care in timely fashion and achieving viral suppression compared with adults (Hall et al., 2013).

In addition to the structural factors that drive HIV-related risk generally, youth at risk of HIV exposure face additional structural barriers to securing their health, including policy and legal impediments and developmentally-specific obstacles (Baggaley et al., 2015). Policy and legal barriers may include legislation preventing young people from consenting to HIV-related services and supports (e.g., HIV testing and counseling, STD treatment) without the consent of a parent or guardian or that restrict their access to condoms and health information (e.g., restrictions on comprehensive sexual health education or failed implementation of it). Although adolescent-specific services exist in many communities, they are not universally available. HIV-related programs and services may have been initially designed to serve adults or may be housed in settings that primarily serve adults, features which may discourage youth from accessing them (Flicker et al., 2005). The social stigma and discrimination associated with HIV also affect youth’s HIV risk (Prado et al., 2013). Stigma and discrimination decrease the likelihood of accessing HIV-related services (Barker et al., 2012; Kinsler, Wong, Sayles, Davis, & Cunningham, 2007; Kurth, Lally, Choko, Inwani, & Fortenberry, 2015) and may lessen attention to HIV prevention, testing, and care messages. Youth who are still developing their gender and sexual identities may be acutely sensitive to and fearful of stigma’s and discrimination’s effects (Prado et al., 2013).

In response to calls for structural interventions targeting youth vulnerability to HIV infection, investigators have begun to field structural intervention studies, primarily in developing countries (Harrison, Newell, Imrie, & Hoddinott, 2010; Larkin, et al., 2007; Shannon, et al., 2008; Soskolne & Shtaarkshall, 2002). Community mobilization efforts in which coalitions are convened to address structural concerns have emerged as a popular strategy, mirroring their widespread use in other disease areas (Anderson et al., 2015) and reflecting their longstanding role in the HIV epidemic as the means to force community systems and institutions to better respond to the needs of people who are vulnerable to or living with the disease. Community mobilizations involve the structured collaboration of diverse individuals and organizations to advance selected health outcomes within their community (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2002). In order to achieve their goals, coalitions may employ a variety of approaches including social planning, capacity building, community organizing, and policy advocacy (Roussos & Fawcett, 2000).

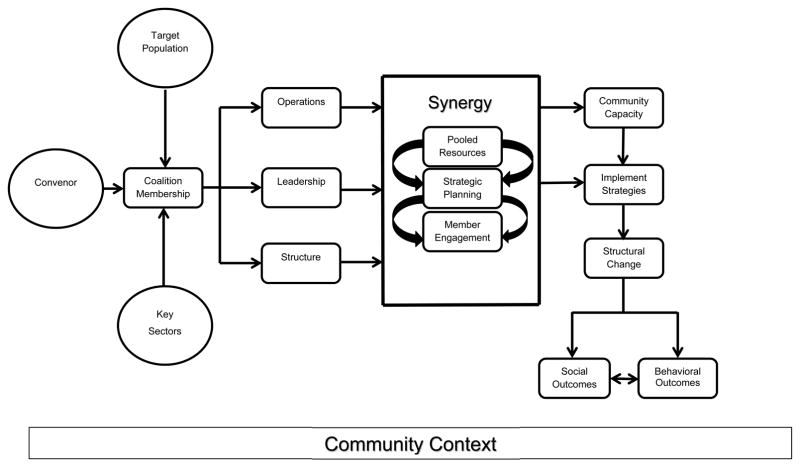

Community Coalition Action Theory (CCAT; Butterfoss & Kegler, 2002; Kegler & Swan, 2011) summarizes the process and elements of coalition formation, operation, and intermediate and long-term impact (see Figure 1). Coalitions typically form when a lead agency or actor convenes representatives of critical sectors and target populations around a community problem (e.g., local disparities in HIV prevalence). The nature of the coalition’s membership, its organizational structure, and its quality of leadership lay the base for the coalition to function effectively. Once convened and functioning, Butterfoss and Kegler (2002) propose that the primary mechanism through which coalitions are maintained is through the collaborative synergy created by bringing together diverse individuals in pursuit of common goals. Collaborative synergy is indicated by resource sharing among coalition members, intensive member engagement, and quality strategic planning. When synergy forms, it allows coalitions to engage in actions that have high likelihood of creating structural changes within their community and in building their community’s capability to address future concerns.

Figure 1.

Community Coalition Action Theory, Adapted from Butterfoss & Kegler, 2002

Although the strategy of mobilizing communities to pursue structural change is intuitively appealing, outcome evaluations of these efforts have often yielded mixed and disappointing results (Anderson et al., 2015). The most disappointing set of studies are those in which structural changes were pursued and distal individual behaviors were measured as the outcome. It is exceedingly costly and difficult to trace the direct contribution of a mobilization effort to individual health behavior for myriad reasons (Bonnell et al., 2006; Cheadle et al., 2013; Prado et al, 2013; Sallis & Green, 2012). Key among these reasons include the temporal distance between the manipulation of a structural factor and the appearance of its individual behavioral consequences, the complexity of the causal chains linking a single behavior to a structural cause, and the high likelihood that most risk behaviors are multiply determined.

Rather than take the view that structural efforts ought to be abandoned if they are not easily studied, some researchers have called for research on mobilizations to examine the proximal outcomes that can be more readily traced to a mobilization effort and to meticulous documentation of what mobilization efforts entail and are perceived to accomplish (Allen, Watt, & Hess, 2008; Francisco & Butterfoss, 2007; Miller, Reed, & Francisco, 2013). Researchers who advocate this stance argue that evaluations are most fruitful when they identify the contributions of these efforts to community and structural change outcomes rather than when they attempt to attribute changes in individual health outcomes to community mobilization attempts. The rationale for approaches documenting contributions over attributions additionally rests on the observation that a successful coalition engaged in a community mobilization effort will influence changes in numerous institutions’ policies, practices, and priorities. However, the coalitions themselves will not implement policy and practice changes or act on these newfound priorities. Others will. Understanding how the coalitions’ actions have affected the actions of these intermediary structures might provide the greatest insight on a coalition’s success. The emphasis on contribution over attribution may also be especially important for disease areas such as HIV. AIDS stigma, political homophobia, and indifference to the epidemic remain significant obstacles to addressing the epidemic. In such contexts, the ability of a coalition to establish collaborative synergy, build AIDS-related community competence, and influence structural-level changes are extremely tall orders, yet worthy pursuits.

In this study, we build on our prior work examining the early progress of a set of coalitions charged with pursuing community and structural changes to prevent HIV infection, facilitate access to HIV testing, and improve linkage to HIV medical care for at-risk adolescents (Miller, Reed, Francisco, & Ellen, 2012; Reed & Miller, 2013; Reed, Miller, & Francisco, 2014). In the current study, we examine the perceived contributions and accomplishments of these coalitions at the end of their lifespans to identify the features of their context and operation that facilitated and undermined their ability to achieve structural change and build capability to effectively manage their local adolescent HIV epidemic.

Methods

The Connect-to-Protect (C2P) Partnership for Youth Prevention Intervention was a demonstration project of the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) and funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Development, National Institute on Mental Health, and National Institute on Drug Abuse. C2P began in 2005–2006 with 14 coalitions. In 2011, four additional coalitions were mobilized, four ceased operation, and one changed leadership (see Table 1). In this study, we focus on the 14 coalitions that were operating during 2015–2016 when the C2P demonstration study came to its close.

Table 1.

C2P Coalitions, 2005–2016

| Location | Convening Institution | Mobilization Years | Youth Target Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baltimore MD | University of Maryland | 2006–2011 | Gay and bisexual males |

| Johns Hopkins University | 2011–2016 | Gay and bisexual males | |

| Boston MA | Fenway Health | 2011–2016 | Gay and bisexual males |

| Bronx NY | Montefiore Medical Center | 2006–2016 | Women |

| Chicago IL | John H. Stroger Jr. Cook County Hospital | 2006–2016 | Women |

| Denver CO | University of Colorado Children’s Hospital of Denver | 2011–2016 | Gay and bisexual males |

| Detroit MI | Wayne State University Medical Center | 2011–2016 | Gay and bisexual males |

| Ft. Lauderdale FL | Children’s Diagnostic and Treatment Center | 2006–2011 | Women |

| Houston TX | Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital | 2011–2016 | Women |

| Los Angeles CA | Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles | 2006–2016 | Gay and bisexual males |

| Memphis TN | St. Jude’s Research Hospital | 2008–2016 | Women |

| Miami FL | University of Miami School of Medicine | 2007–2016 | Women |

| Manhattan NY | Mount Sinai Medical Center | 2006–2011 | Gay and bisexual males |

| New Orleans LA | Tulane University Health Sciences Center | 2006–2016 | Women |

| Philadelphia PA | Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia | 2006–2016 | Gay and bisexual males |

| San Francisco CA | University of California at San Francisco | 2006–2011 | Gay and bisexual males |

| San Juan PR | University of Puerto Rico | 2006–2011 | Substance users |

| Tampa FL | University of South Florida | 2006–2016 | Women |

| Washington DC | Children’s National Medical Center | 2006–2016 | Gay and bisexual males |

Coalitions were convened in most cases by an Adolescent Medicine clinical unit, typically one associated with a major teaching hospital (Straub et al., 2007; Ziff et al., 2006). Each coalition focused its efforts on one population of high-risk youth between the ages of 13 and 24 and on a specific geographic area in their city in which STI and HIV rates among their chosen target population were especially high. During their initial years, the coalitions focused almost exclusively on structural and community changes related to HIV prevention, access to HIV testing, and community capacity development. In 2009, the coalitions expanded their efforts to include a focus on linking newly diagnosed HIV-infected youth to medical care, in partnership with another ATN demonstration initiative on linkage to and sustained engagement in care (Fortenberry, Koenig, Kapogiannis, Jeffries, Ellen, & Wilson, 2017; Philbin, Tanner, DuVal, Ellen, Kapogiannis, & Fortenberry, 2012). Coalitions received annual financial support for one fulltime master’s level coalition coordinator (roughly $65,000 per year plus fringe benefits, depending on the local labor market), and approximately $17,000 each year to support local travel, coalition activities, and basic operations.

Coalitions included representatives of private and public health-focused organizations, organizations from other youth-focused sectors (e.g., education, juvenile justice), and prominent community institutions (e.g., businesses, churches, mayor’s offices) (Chutuape, Willard, Walker, Boyer, & Ellen, 2010; Straub et al., 2007). Coalition partners included community-based organizations specializing in youth of color, GBLTQ youth, and HIV. In many cases, youth from the target population were also members of the coalitions. Coalitions approached mobilization and planning using a structured process adapted from Fawcett et al.’s (2000) VMOSA approach. The approach was modified to incorporate root-cause analysis (Willard, Chutuape, Stines, & Ellen, 2012) to guide the development of a logic model linking structural and community drivers of risk and structural risk mechanisms to individual youth behaviors. Coalitions used their logic models to develop structural change objectives corresponding to the drivers and mechanisms they identified. Each objective was further delineated into action steps with target completion dates and a list of other actors needed to move the objective forward. Structural changes targeted numerous sectors in the community, including healthcare, education, criminal justice, religious, and social services(Chutuape et al., 2015).

All coalitions’ operations were centrally monitored by a technical support staff based at Johns Hopkins University. Support staff at the national coordinating center (NCC) provided the coalitions with ongoing technical assistance and training. C2P staff running the coalitions and the staff at the NCC documented coalitions’ activities, member composition, member feedback, and the status of each structural change objective on an ongoing basis and in a standardized manner. During the final 2 years of the project (2014–2016), 318 key informant interviews with youth and community leaders were conducted by an external evaluation team based at Michigan State University. Institutional review boards at all participating C2P sites and at all protocol team member’s institutions reviewed and approved study procedures.

Design and Data Collection

To identify key informants who possessed specialized knowledge of either the effects of structural changes on the systems and sectors where these effects occurred or of the cascading effects of these changes on youth, coalition staff used outcome mapping techniques (Earl, Carden, & Smutlyo, 2001). We viewed outcome mapping as an appropriate tool because of its emphasis on capturing changes in the behavior, relationships, activities, or actions of the people, groups, and organizations with whom an entity such as a coalition works. In outcome mapping, these “boundary partners” are the people through which change occurs. It is their practices and the policies they must follow in carrying out their work that coalitions are seeking to influence via structural changes. Staff nominated 293 people in 2015 and an additional 168 people in 2016 as prospective informants, for a total of 461 potential interviewees.

The evaluation team contacted each prospective key informant by email to invite their participation. Prospective informants were also contacted by telephone. We made seven attempts to contact each informant before considering them unreachable. If an informant agreed to participate in an interview, he or she was sent an information sheet about the interview in advance, outlining the interview’s purpose, voluntariness, and procedures for protecting privacy. Informed consent was obtained at the time of the telephone interview. Interviews were audio-recorded with the permission of the respondent and later transcribed verbatim. Interviews averaged 53.5 minutes in length (range = 14–180 minutes). Following the interview, informants were offered a $25 gift card. In all, 318 (69%) of nominated people were interviewed, including 50 youth. The number of key informants interviewed in any one site ranged from a low of 13 to a high of 31. At least one youth was interviewed in each site (range = 1 to 12). Interviewed youth were an average of 22.08 years old (range = 16 – 24 years of age). Additional characteristics of key informants are displayed in Table 2. As shown, a majority were current or former coalition members.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Key Informants (N=318)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Employment Sector | |

| Community-based or non-government organization | 111 (35%) |

| Healthcare/medicine | 55 (17%) |

| Government | 54 (17%) |

| Education | 46 (14%) |

| Business | 7 (2%) |

| Other | 45 (14%) |

| Relationship to Local C2P Coalition | |

| Member | 235 (74%) |

| Former Member | 16 (5%) |

| Never Member | 63 (20%) |

| Unspecified | 4 (1%) |

| M (Range) | |

| Time in Current Position | 6.6 years (2 months-31 years) |

The semi-structured interview protocol asked informants to describe the state of HIV prevention, HIV testing, and linkage-to-care for local youth, how these had changed over time, and about opportunities for youth to participate in these HIV-related areas. Informants were prompted to elaborate a list of specific changes enacted in the prior 2 years and to indicate whether each of these had been beneficial to youth. Interviewers were trained to probe informants for evidence to support their assessments of effectiveness. The interview concluded with a series of questions about the local C2P coalition.

Analyses

Prior to conducting analyses, all transcripts were cleaned and formatted for importation into NVivo 11 (QSR International, 2016). We coded the list of achieved structural change objectives for each coalition. For the purposes of these analyses, we applied two codes. Following the work of McNall (2017), the first identified the nature of the structural change reflected by the objective (e.g., public policy; scope, range, quality of community services and resources; cross-sector connections and communication; infrastructure development; mindsets about HIV; and youth access to power). The second identified its intended purpose (e.g., HIV prevention, HIV testing, linkage to HIV care, HIV community capacity building). To ensure consistency of code application, two analysts coded each objective independently. Disagreements in code assignments were resolved through discussion. If necessary, the first author made a final coding decision.

We coded the text of each interview using a codebook that was informed by CCAT constructs and their operationalization (e.g., Butterfoss & Kegler, 2002). We supplemented these codes by drawing on the literature on collaborative capacity (Foster-Fishman, Berkowitz, Lounsbury, Jacobson, & Allen, 2001) and AIDS-competent communities (Campbell & Cornish, 2010; Reed & Miller, 2013). Following the approach outlined by MacQueen and colleagues (MacQueen, McLellan, Kay & Milstein, 1998), we developed a preliminary codebook using these concepts and code definitions.

Coders worked in two-person teams applying one subset of codes to the text and composing memos on emerging themes and patterns. One team focused on codes pertaining to capacity development, one team focused on codes pertaining to achieved changes in the community, and one team focused on the elements of coalition functioning. Each team also took note of contextual factors that informants mentioned as facilitating or impeding the coalitions’ efforts. The coding teams came together to discuss and refine the master codebook and share emergent themes and patterns on a weekly basis. During this process, we refined code definitions until we were satisfied with their precision and that they could be reliably applied to the data. We used NVIVO’s code comparison query to assess code agreement rates for each coding pair until all kappa coefficients were .85 or higher.

Once we fully coded the interviews, we created reports of the coded text for each coalition. Using these reports, one analyst drafted a coalition-level memo summarizing the themes and patterns pertinent to it. Other members of the coding team read the data report for each coalition independently and critiqued the memo draft, looking specifically for omissions or misstatements about the strength of the evidence for any conclusions that were drawn in the memo. Memos were revised accordingly. In addition, coders rated each coalition on each theme, using a standard rating guide. Coders rated a coalition as “exemplary” when a majority of its informants addressed a theme or accomplishment in detail and expressed strong favorable consensus in their comments. Coders rated a coalition as “intermediate” when only a minority of informants mentioned a theme or accomplishment and when either divergent opinions or uncertainty about details were expressed. Coders rated a coalition as “low” when a theme or accomplishment was seldom mentioned and, if it was, informants felt unable to judge its worth, expressed mixed or strongly unfavorable views, or perceived the theme as an emerging rather than well-developed and exemplary characteristic. Using these ratings of the themes at each coalition, we created a master matrix in which coalitions were ordered by their classification as exemplary, intermediate, or low in structural change accomplishments (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2013). Ratings by all other coded themes were entered as the matrix rows. This matrix allowed us to visualize systematic differences in the relationships between ratings on the coded themes across the spectrum of ratings of accomplishment.

Results

Structural Change Accomplishments

Across the 14 cities, coalitions established 959 structural change objectives, of which 560 (58.4%) were achieved (see Table 3). Prevention objectives were the most common among those achieved (n=205; 36.6%), followed by objectives to build local capacity (n=160; 28.6%), link HIV-infected youth to medical care (n=111; 19.8%), and improve access to HIV testing (n = 84; 15.0%). Across these areas of purpose, the largest number of achieved objectives sought to improve the quality, accessibility, scope, and nature of programs and services (n=222; 39.6%). The remaining achieved objectives concerned establishing functional relationships, connections, and communication across multiple sectors and agencies (n=139; 24.8%), facilitating implementation of city, county, or statewide policies or enacting new policies (n=75; 13.4%), developing human resource and service infrastructures (n=78; 13.9%), changing attitudes and beliefs about youth and HIV (n=28; 5.0%), and creating mechanisms for youth to share in the design of programs and policies and participate in decision making (n=18; 3.2%). Coalitions varied widely in the number of structural change objectives they achieved (14–84). Unsurprisingly, coalitions founded in 2011 achieved far fewer objectives than coalitions operating since C2P’s founding.

Table 3.

Structural Change Objectives Accomplished by C2P in 14 US cities (N=560)

| HIV Domain | Number of Objectives Accomplished | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention | 205 | The State of Illinois will repeal the abstinence only act and implement comprehensive health education instruction. (Chicago) Children’s Hospital Immunodeficiency Program will increase access to biomedical HIV prevention services to young men having sex with men by opening a PREP clinic. (Denver) |

| Testing | 84 | Six CBOs will start a new program to provide venue based mobile HIV counseling and testing in venues frequented by youth and young adults. (NYC) The city will implement Hip Hop and R&B, an annual city-wide incentivized HIV testing and STI screening for 1,000+ youth through a collaboration of the Department of Health, the Community Planning Group, local radio stations, and AIDS service organizations. (Philadelphia) |

| Linkage to Care | 111 | The Department of Health will establish a protocol for CBOs and health centers around linking HIV positive youth to care. (Washington DC) The County Probation Department will develop an internal guideline regarding post-incarceration placement of HIV positive youth within the system. (Los Angeles) |

| Capacity Building | 160 | The Phillips Brooks House Association’s Harvard Square Youth Housing initiative will ensure that their shelter has a policy concerning inclusivity of transgender and gender non-conforming youth and that all staff are trained in this policy. (Boston) The School Health Advisory Committee will establish a Sexual Health Advisory Board with the sole responsibility of providing technical assistance and support to nurses, teachers, and health aids in their teaching of the Sexual Health Curriculum. (Tampa) |

Informants remarked favorably on their coalition’s perceived accomplishments, although they often named the fewest prevention accomplishments and characterized those they could recall as especially difficult to secure. The prevention accomplishments mentioned by informants were often concerned with comprehensive sexual education policy and efforts to improve the quality and quantity of information youth might access through schools. The hard-won nature of securing these policy changes may have made these especially salient to the informants compared with other prevention accomplishments. Informants associated with coalitions in which progress had been made toward implementing comprehensive education in schools cited their coalition’s leadership as critical to moving local policies forward. Informants attributed C2P’s success in schools to the coalitions’ credibility, thoughtful planning, persistence, ability to bring diverse sectors together in the spirit of collaboration, and depth of engagement of members in the work of arguing for and reshaping policy. In the quote that follows, an informant from Boston describes how C2P contributed to new policies for comprehensive health education in the local schools, staffing every policy development work group on the local district council:

A lot of the members of C2P actually sat on our work group at the district level on our District Wellness Council. That was really awesome because everyone’s perspective, I guess, was included in writing the policy and as the policy was being written.

Another characterized C2P’s involvement as “a fantastic resource when we were writing policy to make sure that we were meeting the needs of youth and had the right people at the table.”

Informants spoke excitedly of accomplishments in the areas of testing and linkage to care and frequently identified C2P’s contributions to changes in these domains. Structural changes related to testing often sought to expand testing availability in non-traditional venues (e.g., schools, juvenile justice facilities, ERs) and through outreach (e.g., mobile testing). Structural changes to link youth to care primarily involved efforts to streamline the linkage-to-care process, raise awareness of linkage-to-care resources, decrease barriers to medical service (e.g., issues related to confidentiality, insurance), and increase the resources for youth newly diagnosed with HIV (e.g., provide transportation). Informants often claimed C2P was uniquely able to bridge the medical, public health, and social service sectors to bring about these changes and “credited C2P almost entirely” with creating the ability to better serve HIV-positive youth in their city:

Chicago is huge! And we have a million coalitions. But C2P was a viable one that really had key members….the Chicago Department of Public Health, the AIDS Foundation, behavioral health providers, everybody who was important to public health was at the C2P table.

In some cities, C2P was regarded as the primary entity actively and successfully working to ensure youth were well-served by social policy and facilitating collaborative efforts to address HIV among youth, noting “They’re [C2P] the only group that has made changes in the community to help reduce the number of HIV infections” and as the sole actors “collectively figuring out solutions” for youth. In these cities, C2P filled a unique void through its ability to bring diverse people together to address the needs of local youth at-risk of or living with HIV. In others, C2P added value to existing efforts, extending their reach to younger populations at highest risk.

Changes in Community Capacity

According to CCAT, as a result of participating in coalitions, community members and organizations should develop capacity that can be applied to other health and social issues and to changes that occur over time in the particular problem space in which the coalition works. In addition to accomplishing a wide range of objectives that key informants believed benefited their community, informants identified multiple perceived improvements to community capacity.

Knowledge

Informants from all coalitions credited C2P with improving community knowledge. Informants described learning about processes to facilitate structural change, opportunities for professional development, heightened awareness of coincident community issues, and new understandings of health (in)equity. Informants believed C2P’s information sharing and structural change endeavors enhanced community awareness of various local services and led to the development of novel ways to provide services to diverse youth populations.

Partnerships

Informants from nearly all coalitions described C2P as a “unifying force” that fostered new or improved partnerships in the community. Partnership development was especially important, given the historical competitiveness that existed among many HIV-service organizations: “one of the things that has changed in the last couple of years is having a coalition where people see the value of collaboration and can drop some of the concerns around competition.” New partnerships, particularly those that spanned multiple sectors, were often a prerequisite to accomplishing structural changes. In addition to benefiting C2P, coalition members said these new or strengthened partnerships benefited their home institutions. Informants were optimistic that these collaborations and relationships might remain, even in the pending absence of C2P: “through the coalition, a lot of partnerships have been developed and a lot of relationships have been built that will still be around [when C2P’s funding ends].”

Sense of Community

Informants cited an improved sense of community occurred within a majority of coalitions. Informants described a newfound sense of belonging. At a few coalitions, informants described C2P as approximating a family: “[C2P] was just part of us. It was like your brother or your sister, and they’re part of your family.” The diverse array of actors C2P brought together was unusual, as they crossed the boundaries of traditional silos. Meeting numerous people who were passionate about working with youth, preventing HIV, and making their communities a better place, helped informants feel “like [they’re] not alone in doing this work.” Informants who had been coalition members also noted a unique sense of safety associated with C2P:

…walking into any sort of group of professionals or community members you never really know what their opinion is on LGBT issues or HIV prevention or Planned Parenthood. So to have this almost safe space to talk about these issues and realize you’re not alone, I think is really important.

Informants who were former C2P members evinced a shared emotional connection; they described trusting and respecting other members, feeling increasingly committed to the coalition and community, having hope for the future of their community, and enjoying their involvement in C2P.

Amidst this emerging sense of community, informants lamented the impending defunding of C2P, noting it was the sole entity in the community pursuing structural changes and doing so effectively: “the whole fact that C2P is closing is tragic for what we do.” Some informants reported concern that, without C2P, their community might revert backward. Members would be cut off from opportunities for participating in high-leverage collective action. They feared C2P closing down might lead to the neglect of youth concerns. As one informant explained: “it takes a brave system in a brave situation like C2P to get this done. I don’t know how we are going to do this anymore.” Across the coalitions, informants from only five coalitions made mention of efforts to sustain their coalition through securing alternative funds.

Youth Leadership

Approximately half of the coalitions were described as having created new opportunities for youth leadership and for youths’ voices to be heard. At these coalitions, C2P prioritized youth participation and developed multiple ways to engage youth members. Informants from these cities noted there were multiple external opportunities for youth involvement in HIV prevention and testing; however, key informants observed there were few local opportunities for youth to work on issues of linkage-to-care. Half of the coalitions struggled with a lack of youth engagement. Informants from these cities voiced dissatisfaction with the lack of youth involvement in their coalitions. Community opportunities for youth to participate in action and programming on HIV in these cities were described as more “tokenistic” than meaningful and as limited to a few organizations.

Cultural Competence

Cultural competence significantly improved at a handful of coalitions, particularly those focused on addressing the needs of young men who have sex with men. C2P frequently offered trainings for providers to increase their competence to work with youth. Informants noted increased ability and willingness among providers to work with disenfranchised youth populations. Many informants suggested C2P’s efforts led to improvements in culturally competent care in their cities. For example, the Washington coalition spearheaded the prioritization of lesbian, gay bisexual and transgender (LGBT) culturally competent services throughout the city. Many of the coalitions’ attempts to enhance cultural competence were directed at settings such as schools, homeless shelters, and foster care systems. Despite these successes, informants from multiple coalitions cited a need for more youth-specific services, particularly for linkage-to-care, and competency training addressing the intersection of various facets of identity (e.g., gender, sexuality, race, class).

Facilitators and Impediments to Achieving Structural Change Objectives

Although key informants reported that the work completed by C2P was generally praiseworthy, not every coalition was perceived as a major contributor to local structural change efforts or as having accomplished work of a significant nature. Informants were unable to point to changes resulting from some coalition’s work outside of the domain of linkage to care; in a few cases, they could not even attribute perceived improvements in linkage to care to the structural change work of the coalition. Ten of the coalitions stood out as exemplary or intermediate in their success at creating structural change. To better understand how these coalitions differed from those whose success we rated low, we compared the coalitions on twelve themes. Four themes consistently distinguished the higher-achieving exemplary and intermediate coalitions from those that informants viewed as having yet made limited contribution to local structural and community change.

Coalition Leadership

At most of the exemplary and intermediate coalitions, the paid staff members who led them were characterized by informants as able, dedicated leaders who worked tirelessly to keep the coalition moving forward. Informants from these communities praised their coalition’s leaders for engaging members, maintaining momentum, securing the coalition’s visibility, and facilitating strategic planning, often attributing success to their leadership:

One [factor that facilitates C2P] is the leader of the coalition. It’s important who it is and if it’s the right personality to do that type of work. That is the gatekeeper or the coach to get people involved and stay involved. And then they do what they say they’re going to do. That’s how they promote public support and then selling it to the community.

At only one intermediate coalition was its leadership described unfavorably. It operated in a context characterized by a disagreeable political climate and significant institutional distrust. The low-rated coalitions shared a similarly unhospitable context with this coalition. At the low-rated coalitions, C2P leaders struggled to engage community members and obtain buy-in. Informants from these coalitions noted turn-over in coalition leadership derailed momentum and led to missed opportunities.

In addition to strong paid leadership, higher-achieving coalitions successfully engaged savvy community leaders as coalition members. These community leaders were well connected and understood how their community operated. Their involvement helped establish the coalition’s clout and allowed it to wield significant influence in critical sectors:

The meetings are of these high-powered people from all walks of life in our community. We had a good C2P coalition of active members who were committed, like an assistant superintendent from the Miami Dade County Public Schools and the director of the HIV services of the Miami Dade County unit of the Florida Department of Health. And we had a representative from the Office of the Mayor, a special assistant. And these were people who were very active…That was exciting.

Whereas informants at higher-achieving coalitions praised the multi-sectoral composition of their coalition and its inclusion of influential members, informants at low-rated coalitions lamented that they did not have “high enough people at the table” and that “the decision makers aren’t there.” The informants said these coalitions experienced substantial difficulty in bridging to sectors outside of HIV clinical care and HIV support services and failed to create meaningful and enduring links to community leaders and policy makers. These coalitions’ capacity for multi-sectoral collaboration had not fully developed.

Collaborative Synergy

Informants from the higher-achieving coalitions spoke at length about the collaborative spirit engendered by C2P. Informants who had been involved with C2P in some fashion and informants who only knew of C2P through its activities remarked on the obvious synergy that had developed among C2P members. Informants who had been members of higher-achieving coalitions especially valued C2P’s collaborative spirit:

I’ve heard other people say this about the sense of unity. Like we’re here to improve things for young folks instead of, I’m here as my agency or I’m here to do this. I think everyone in the room, when we’ve been working together, has felt like we’re all working toward the same goal.

Coalition members from these cities were said to share a sense of mission. This unifying sense of purpose and collectivist approach was particularly valued at coalitions targeting young men who have sex with men, cities in which organizations were said to have a long history of competing with one another for funding:

Connect to Protect is an important player because I think their table was the first table in a really long time where true coalition and collaboration was the value….That together we can do things and we are not going to let turf get in the way of good service and meeting the needs of the community.

Informants from cities with higher-achieving coalitions also viewed their coalition’s multi-sectoral, structural change approach as generating new and improved ways of responding to youth’s health issues:

I am increasingly frustrated with the way these things get parceled out as though they are entirely distinct from one another. And, so I think being a part of C2P has kind of affirmed for me the power of people from different fields coming together to get work done and now I would really like to see that continue in terms of when we have overlapping concerns that we should also have coordinated strategies.

In contrast, informants from the low-rated coalitions indicated that their coalitions suffered from chronic internal discord over their mission, perceived the focus had been appropriated by a single actor (e.g., the Health Department) rather than collectively determined, or felt stymied by the coalition’s single-minded emphasis on one issue (e.g., linkage to care, school-based reform) to the exclusion of other local concerns. Dissent about these coalitions’ priorities caused members to disengage and impeded their strategic planning. Informants from these communities decried the lack of a “holistic” and collaborative approach suitable to addressing local needs. Informants complained of fractious disagreement on direction, high rates of member turnover, and a plodding pace toward progress.

Informants from cities with higher-achieving coalitions suggested a bidirectional relationship exists between collaborative synergy and coalitions’ accomplishments. Successful community change efforts invigorated members’ motivation and continuously informed their ongoing strategic planning process. Many of these coalitions successfully “packaged” their newer community change efforts to build upon their previous successes. Accomplishments inspired existing members and attracted new members to the coalition, enhancing member engagement:

I’ve really seen a passionate group that has really strong feelings about this issue, wants to make change, wants to move the community forward and will do a lot of work to make that happen. It’s very encouraging to know that those people exist and that they’re out there and that they can make lots of things happen in a very short period of time.

Institutional Trust

In several C2P communities, the fact that it was a public or university hospital convening C2P was perceived to lend the coalitions a unique blend of neutrality and power uncommon to other coalitions operating in these cities. Many informants mentioned that the medical care facility’s lack of participation in the ongoing “funding war” that plagues AIDS-related social service and community-based organizations helped members perceive C2P as a “safe space” where they could feel comfortable sharing ideas and resources. In these cases, being operated by a well-resourced clinical care facility was viewed as advantageous.

However, in half of the coalitions, the bulk of which were at the low achieving end of the spectrum, informants reported institutional distrust of the convening institution. In these instances, the convening institution was viewed skeptically for its lack of requisite experience working with the coalitions’ target population and its limited history of community engagement. Leaders at higher-achieving coalitions faced with institutional distrust owned up to their institution’s historical shortcomings and demonstrated that they took these concerns seriously. These coalitions made concerted efforts to improve their internal cultural competence. For example, one higher-achieving coalition at which members voiced concerns that the convening institution lacked experience working with racial minority youth and had contributed to the “systemic oppression” of local LGBT people of color, responded by deploying a racial justice framework to guide their strategic planning. Higher achieving coalitions at which institutional distrust was evident also engaged diverse youth members in meaningful ways, assuaging concerns that the convening organization was not genuinely interested in “grassroots” change: I think people recognize that it [youth involvement] works. I think organizations are feeling that ethically it’s more appropriate to have the populations they want to serve be a part of making those decisions.

A second target of distrust was revealed in the interviews from low-rated coalitions. In these cases, the coalition had engaged a local institution or organization as a coalition partner that was viewed by many in the coalition’s membership with contempt and suspicion. These institutions and organizations were described by informants as disconnected from the community and as having seized the C2P agenda for their own gain. Informants from these communities worried about “hidden agendas” and implied that synergy had been hindered by the “personal drama” created by allowing these institutions to become members. These experiences stymied progress and decreased members’ engagement:

This other group comes by. And now they said, “well, we can do just as well or better.” And we are like saying, “Well, that wasn’t the intention. We thought you were coming in to share resources. Now you want to take over. Now we don’t want to sit with you. We don’t want to merge. We don’t want to participate.” Many like myself just simply turned in letters of resignation and said “thank you very much, but no.”

The least successful coalition among all was itself distrusted. It did little to counter that distrust and magnified it by inviting in to the coalition institutions about which the community held ambivalent views.

Supportive Political Climate

Among the most striking differences between coalitions on the exemplary end of the achievement spectrum and those on the lower end was whether the coalition operated in an environment in which the city and state political climate was perceived as supportive and agreeable. Many of the informants from higher-achieving coalitions noted that they operated in cities or states where there was significant political support for addressing HIV, LGBT rights, and health inequity. The leadership in these cities eagerly embraced the guidance laid out in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and welcomed policies such as the Affordable Care Act, enabling the work of many AIDS-focused actors in the community, including those involved in C2P. Informants from the few higher-achieving coalitions that operated in fraught and conservative political environments indicated that their coalitions purposefully avoided change efforts aimed at sectors of the community they thought unlikely to change, such as schools and faith-based organizations. These higher-achieving coalitions also strategically targeted their structural change efforts to address social issues that were receiving significant political attention and local funding (e.g., youth homelessness, juvenile justice concerns, sexual assault, domestic violence), finding common cause by linking HIV to these concerns.

In coalitions described as having fewer and less worthwhile achievements, key informants described the local political climate as so contentious, conservative, or unresponsive, particularly around issues related to sex education and reproductive health, that it obstructed the coalitions’ efforts. Informants from coalitions operating in the South and those focused on female youth described significant barriers to enacting change in multiple sectors of the community. Inordinate time and effort went to raising community awareness of HIV as a disparity affecting minority women and to countering perceptions of HIV as a “gay disease.” Community intolerance of open discussion of sex and sexuality and widespread public denial that HIV affects women left these communities with limited readiness for pursuit of structural change. Further, informants from these communities indicated that local HIV funding and priorities increasingly emphasized targeting young men who have sex with men. As new HIV-related priorities started to trend (e.g., linkage to care, PrEP) female-focused efforts in these communities often lost traction. These coalitions also often remained inflexibly committed to change efforts they repeatedly found to be politically infeasible. They seldom shifted strategic priorities, despite increasing evidence of unsurmountable political obstacles. Whereas the more successful coalitions used local political concerns as an opportunity to strategically realign their priorities, at these lower achieving coalitions, the coalition failed to translate current political issues (e.g., police brutality, race-based violence, gang violence) into feasible structural change opportunities. Rather, informants from these communities reported being overwhelmed by the depth and scope of these systemic issues. They exhibited a sense of hopelessness that their community problems were too big to meaningfully address through collective action.

Discussion

We sought to add to a growing body of research on structural change initiatives that rely on community mobilization strategies in the domain of HIV. Community mobilizations are often used in developing country contexts to promote structural changes to reduce youth’s HIV risk, but are seldom investigated in the domestic U.S. context. Better understanding of the viability of community mobilization and structural change efforts within the domestic HIV arena represents an important pursuit, given international consensus that the epidemic cannot be addressed without attacking the social realities that support its spread (Blankenship et al., 2000; Gupta et al., 2008; Piot et al., 2008). Moreover, because the social and structural realities promoting HIV risk among youth differ from those of adults and from one context to the next, unique barriers may be encountered in pursuing structural change approaches targeting youth health (Rotheram-Borus, 2000).

The public health significance of structural change interventions lies in their promise to affect large numbers of people in a sustained manner (Campbell & Cornish, 2010). The findings from the current study suggest that community mobilization efforts like C2P can contribute to addressing the structural and community factors that promote HIV-risk among youth and that impede access to HIV testing and timely HIV medical care. The C2P coalitions we studied accomplished important structural and community changes, most of which had the potential to affect large numbers of youth at risk and those already living with HIV. Through collective action, the changes coalitions contributed to achieving ranged from major shifts in state-, county-, and district-level policies to changes in institutional policies, practices, and relationships. In the case of most coalitions, these changes were said to lead to discernable improvements in the quality, diversity, and ease of access to a wide range of interventions, services, and resources for local youth. Even though we found near universal agreement at how much more must be done to secure youth’s health, the successes of C2P coalitions were broadly viewed as significant, positive steps forward. Informants’ testament regarding C2P’s impact provides social validation (Francisco & Butterfoss, 2007) of C2P’s local benefits.

A key to these hard-won gains came through the contribution C2P coalitions made to local capability to manage HIV-risk and infection among youth more effectively, a primary reason for employing a mobilization strategy. Although we noted weaknesses in capacity development at the lower achieving coalitions where capacity was still emerging, most of the coalitions succeeded in laying a substantial part of the foundation for an AIDS-competent community capable of acting as the steward of its youth’s health and welfare into the future. We observed, for instance, that C2P cultivated the knowledge and skills among its members to problem-solve, plan collective actions, and use evidence to inform decisions. These reported changes to members’ knowledge and skills were outcomes of the direct effort of the coalitions to build member and community capacity. They also occurred through the process of engaging in collective action to secure structural change. The gains in knowledge and skills coalition members described applied to the work of the coalition and to their work outside of the coalition, a collateral benefit of coalition participation informants valued highly.

In the most successful of the C2P implementations, the coalitions fostered a deep sense of ownership over the fate of the youth epidemic among its members. In these coalitions, a sense of solidarity and community evolved. In the most exemplary of the coalitions, each of the facets of sense of community were present: reinforcement of needs, membership, emotional connection, and influence (McMillan, 1996; McMillan & Chavis, 1986). The blossoming sense of community developed in tandem with a reduced emphasis on competition, increased collaboration and partnerships, and engagement in collective problem solving. The fact that the coalitions were fully funded and supported by an entity that was not an ordinary competitor for funds among its members enabled this sense of community to flourish in many of the C2P communities. Partners could come together in common cause without needing to fight one another over resources. That this well-developed sense of community was strongly evident in the most successful C2P coalitions suggests its importance to the development of AIDS competent communities.

CCAT suggests that the development of collaborative synergy is a prerequisite for accomplishing community change (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2009). Our data fully support this proposition. Yet, we also observed that there is a reciprocal relationship among the indicators of collaborative synergy – resource sharing, member engagement, and strategic planning – and community capacity and community change accomplishment. Coalition accomplishments and capacity enhance member engagement and influence the strategic planning process. This was evident in our data in at least two ways. First, our most successful coalitions often turned the mirror onto themselves, recognizing their own potential to recreate the structural conditions that may negatively impact on youth’s health within their own coalitions. These coalitions owned and actively addressed their own prior institutional failures to engage youth in leadership roles and provide developmentally and culturally competent services and events for high-risk youth. They chose to do what they prescribed others ought to do and developed new capacities in the process. Second, coalitions that mimicked their own community change efforts tended to enjoy additional success, which reinforced their collaborative energy and provided a sense of reward and accomplishment to members. These findings may suggest the heart of a coalition’s ability to affect community change resides in the reinforcing effects of vibrant collaborative synergy, active learning, and well-honed ability to build on successful actions.

CCAT posits that coalitions require strong leadership to precipitate member synergy (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2009). Our data support this proposition, but also suggest that leadership’s ability to serve as a coalition’s glue and driving source of momentum can be strained by an environment rife with institutional distrust. In the most fraught settings, participants lacked the basic ability to be good coalition members. Effective leaders were reported to actively cultivate their own and others’ collaborative capability. They made concerted and sincere efforts to address the basis for distrust of their institution. By contrast, less effective leaders failed to attune to perceived power differences among members. They failed to address deep-seated mistrust among member factions, undermining the base for cooperative collective action.

A key lesson our informants offered concerns the undermining effects of an adverse social and political context for AIDS-competent communities and community mobilization efforts in pursuit of structural change to reduce youth HIV risk. Adversarial social and political environments stand to benefit the most from structural and community change interventions. Yet, consistent with prior research on coalitions and political contexts (Kegler, Rigler, & Honeycutt, 2010; Miller, Reed, Francisco, & Ellen, 2012), we observed that contentious political environments repeatedly derailed coalition progress. Making incremental progress in adverse contexts occurred only for those coalitions that were strategic about refashioning their priorities rather than attempting to sail against local headwinds. An advantage of structurally focused coalitions is their emphasis on addressing root causes of risk with the potential to bridge health and social issues with shared structural determinants. The coalitions in our study that were perceived as successful despite their noxious context exhibited flexibility in pursuing their missions. When met with political obstruction, these coalitions did not hesitate to identify issues of high political priority, to examine the potential for collaborative action on those priorities, and to align their efforts accordingly. Although commitment to enacting HIV-specific high-level policy changes that would have far reaching impact on multiple youth is commendable, these coalitions opted for momentum and engagement through incremental steps and willingness to change course.

Limitations

Several methodological limitations warrant consideration when interpreting these findings. First, although there was significant variability in the personal characteristics of informants we interviewed from each C2P coalition (e.g., youth versus adults, current or former coalition member versus non-member, occupation), our lists of key informants were developed by each coalition’s leadership. Coalition leaders may have disproportionately recommended informants who possessed positively biased views of the coalition and a small number of informants who were likely to offer critical views on coalition accomplishments or functioning. Following the work of Allen et al., (2008), we sought to guard against this possibility by asking for detailed descriptions of changes and actions, with a focus on observed changes in the 2 years prior to each interview. We asked for evidence in support of every claim of positive impact. We limited our analysis to changes that corresponded with accomplished objectives from the coalition’s and NCC’s records, as these could be most clearly attributed to the coalition’s work. Nonetheless, the sample of informants may have provided us with an unduly favorable view of the coalitions’ accomplishments, painting a picture of them as more successful and impactful than warranted.

Second, although we sought to interview a minimum of 15 informants from each of the 14 coalitions, including youth, we were unable to interview as many youth informants as would have been ideal. Youth represented approximately 15% of informants. Unsurprisingly, we interviewed fewer youth from coalition cities that adults said did a poor job of youth engagement than we did from coalition cities in which youth engagement was cited as a strength. We were therefore not able to obtain social validation of the coalitions’ benefits or critiques of their efforts from the perspective of diverse and large numbers of youth. Third, we were unable to gain the perspective of informants from the communities in which C2P ceased to function early in the mobilization effort. Better understanding of the factors that led to the demise of these coalitions might have provided useful insights on the factors that support and undermine coalition success.

Fourth, other social changes coincided with C2P’s efforts, including the introduction of the Affordable Care Act and the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, along with other ATN-supported projects. Medicaid expansion, changes in insurance access for young adults, and ongoing improvements to Ryan White-supported services are examples of simultaneous activity that undoubtedly helped youth in these communities and improved youth outcomes. Whatever praise informants may offer regarding C2P’s contributions and no matter how many of the coalitions’ objectives were achieved, it is unlikely C2P was solely responsible for local changes benefiting high-risk youth. Finally, the unanticipated loss of funds under sequestration caused the ATN to cancel annual youth behavioral data collection and HIV testing as a cost-saving measure. We therefore cannot ascertain whether completion of coalitions’ objectives ultimately led to reduced HIV incidence, uptake of HIV testing, or improved linkage to care for newly diagnosed youth. However, companion ATN studies operating simultaneously capitalized on the C2P infrastructure. These studies suggest it is probable C2P made a positive contribution to local HIV testing of high-risk youth and to timely linkage-to-care (see, for example, Fortenberry et al., 2017 and Miller et al., 2017).

These caveats aside, we find that coalition mobilization can contribute to AIDS-competent communities by improving member and community knowledge and cultural competence, increasing opportunities for youth leadership, supporting the creation of new and improved partnerships, and building a sense of community around HIV concerns. Our theoretically informed analysis of coalitions’ community mobilization efforts identified four key elements of success for accomplishing youth-focused HIV-related structural and community change through community mobilization. First, AIDS-focused community mobilizations to address youth’s HIV related needs require skilled leaders who devote their fulltime effort to fulfilling the coalition’s mission and maintaining its momentum, bringing and keeping knowledgeable community actors from multiple sectors at the table. Second, coalitions benefit from leadership that can confront the myriad challenges associated with political opposition to HIV-related structural changes wisely and nimbly and when necessary, reframe the coalitions’ work as consonant with issues around which there is greater political will. Third, in the case of institutions that are not traditionally regarded as leaders in grassroots community mobilizations, a not unlikely scenario within the context of public health and provision of medical care, coalition efforts stand a better chance of flourishing when leaders can directly confront their personal limitations as trusted community leaders and those of their institutions. Finally, consistent with CCAT’s leading proposition, we find collaborative synergy an essential ingredient for successful coalition activity, allowing coalition actors to persevere and find community in the face of the difficult and long process of creating structural and community change.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) from the National Institutes of Health [U01 HD 040533 and U01 HD 040474] through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (B. Kapogiannis), with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (S. Kahana) and Mental Health (P. Brouwers, S. Allison). We acknowledge the contribution of the investigators and staff at the following Adolescent Medicine Trials Units (AMTUs) that participated in this research: Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles (Marvin Belzer, MD, Miguel Martinez, MSW/MPH, Julia Dudek, MPH, Milton Smith, BA); John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County and the CORE Center (Lisa Henry-Reid, MD, Jaime Martinez, MD, Ciuinal Lewis, MS, Atara Young, MS, Jolietta Holliman, Antoinette McFadden, BA); Children’s Hospital National Medical Center (Lawrence D’Angelo, MD, William Barnes, PhD, Stephanie Stines, MPH, Jennifer Sinkfield, MPH) Montefiore Medical Center (Donna Futterman, MD, Bianca Lopez, MPH, Elizabeth Spurrell, MPH, LCSW, Rebecca Shore, MPH); Tulane University Health Sciences Center (Sue Ellen Abdalian, MD, Nadrine Hayden, BS; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Patricia Flynn, MD, Aditya Guar, MD, Andrea Stubbs, MPH); University of Miami School of Medicine (Lawrence Friedman, MD, Kenia Sanchez, MSW); Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Steven Douglas, MD, Bret Rudy, MD, Marne Castillo, PhD, Alison Lin, MPH); University of South Florida (Patricia Emmanuel, MD, Diane Straub, MD, Amanda Schall, MA, Rachel Stewart-Campbell, BA; Cristian Chandler, MPH, Chris Walker, MSW); Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital (Mary Paul, MD, Kimberly Lopez, DrPH; Wayne State University (Elizabeth Secord, MD, Angulique Outlaw, MD, Emily Brown, MPP); Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine (Allison Agwu, MD, Renata Sanders, MD, Marines Terreforte, MPA); The Fenway Institute (Kenneth Mayer, MD, Liz Salomon, EdM, Benjamin Perkins, MA, M.Div.); and University of Colorado (Daniel Reirdan, MD, Jamie Sims, MSW, Moises Munoz, BA). We appreciate the scientific review provided by members of the Community Prevention Leadership Group of the ATN. We are also grateful to the ATN Coordinating Center at the University of Alabama (Craig Wilson, MD; Cynthia Partlow, MEd, and Jeanne Merchant, MPH) who provided scientific and administrative oversight; the ATN Data and Operations Center at Westat, (James Korelitz, PhD, Barbara Driver, RN, Rick Mitchell MS, and Marie Alexander, BS) who provided operations and analytic support to the ATN; and the National Coordinating Center at Johns Hopkins University, Department of Pediatrics (Jessica Roy, MSW, Rachel Stewart-Campbell, MA, MPH) who provided national-level oversight, technical assistance, and staff training. The comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The investigators are grateful to the members of the local youth Community Advisory Boards for their insight and counsel and are indebted to the youth and adult community informants who participated in this study.

References

- Allen NE, Watt KA, Hess JZ. A qualitative study of the activities and outcomes of domestic violence coordinating councils. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(1–2):63–73. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LM, Adeney KL, Shinn C, Safranek S, Buckner-Brown J, Krause LK. Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(6):CD009905. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009905.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DH, Swenson RR, Brown LK, Stanton BF, Vanable PA, Carey MP, … Romer D. Blocking the benefit of group-based HIV-prevention efforts during adolescence: The problem of HIV-related stigma. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(3):571–577. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley R, Armstrong A, Dodd Z, Ngoksin E, Krug A. Young key populations and HIV: a special emphasis and consideration in the new WHO Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(Suppl 1):19438. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.2.19438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker LG, Johnson L, Wallace M, Hosek S. Building our youth for the future. Journal of International AIDS Society. 2015;18(Suppl 1):20027. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.2.20027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KS, Bray SJ, Merson MH. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14:S11–S21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C, Hargreaves J, Strange V, Pronyk P, Porter J. Should structural interventions be evaluated using RCTs? The case of HIV prevention. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(5):1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss FD, Kegler MC. Toward a comprehensive understanding of community coalitions: Moving from practice to theory. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby R, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: Strategies for improving public health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 157–193. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss FD, Kegler MC. The community coalition action theory. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby R, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: Strategies for improving public health. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 237–276. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Cornish F. Towards a “fourth generation” of approaches to HIV/AIDS management: Creating contexts for effective community mobilization. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1569–1579. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Nair Y, Maimane S. Building contexts that support effective community responses to HIV/AIDS: A South African case study. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:347–363. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. 2015:27. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

- Cheadle A, Schwartz PM, Rauzon S, Bourcier E, Senter S, Spring R, Beery WL. Using the concept of “population dose” in planning and evaluating community-level obesity prevention initiatives. American Journal of Evaluation. 2013;34(1):71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape KS, Willard N, Sanchez K, Straub DM, Ochoa TN, Howell K, … Ellen JM. Mobilizing communities around HIV prevention for youth: How three coalitions applied key strategies to bring about structural changes. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2010;22(1):15–27. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape KS, Willard N, Walker BC, Boyer CB, Ellen J the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. A tailored approach to launch community coalitions focused on achieving structural changes: Lessons learned form a HIV prevention mobilization study. Journal of Public Health Management Practice. 2015;21:546–555. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl S, Carden F, Smutylo T. Outcome mapping: Building learning and reflection into development programs. Ottawa, ON: International Development Research Centre; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett SB, Francisco VT, Hyra D, Paine-Andrews A, Schultz JA, Russos S, Fisher JL, Evensen P. Building healthy communities. In: Tarlov AR, St. Peter RF, editors. The Society and Population Health Reader: A State and Community Perspective. Itasca, IL: F. E. Peacock Publishers; 2000. pp. 314–334. [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S, Skinner H, Read S, Veinot T, McClelland A, Saulnier P, … Goldberg E. Falling through the cracks of the big cities: who is meeting the needs of HIV-positive youth? Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96:308–312. doi: 10.1007/BF03405172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, Koenig LM, Kapogiannis BG, Jeffries CL, Ellen JM, Wilson CM. Implementation of an integrated approach to the National HIV/AIDS strategy for improving human immunodeficiency care for youths. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171:687–693. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman PG, Berkowitz SL, Lounsbury DW, Jacobson S, Allen NA. Building collaborative capacity in community coalitions: A review and integrative framework. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:241–261. doi: 10.1023/A:1010378613583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco VT, Butterfoss FD. Social validation of goals, procedures, and effects in public health. Health Promotion Practice. 2007;8:128–133. doi: 10.1177/1524839906298495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, Holtgrave DR, Furlow-Parmley C, Tang T, … Skarbinski J. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173:1337–44. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Newell ML, Imrie J, Hoddinott G. HIV prevention for South African youth: which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC public health. 2010;10(1):102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AS, Hall HI, Hu X, Lansky A, Holtgrave DR, Mermin J. Trends in diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States, 2002–2011. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312:432–434. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, Rigler J, Honeycutt S. How does community context influence coalitions in the formation stage? A multiple case study based on the Community Coalition Action Theory. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, Swan DW. An initial attempt at operationalizing and testing the community coalition action theory. Health Education & Behavior. 2011;38(3):261–270. doi: 10.1177/1090198110372875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsler JJ, Wong MD, Sayles JN, Davis C, Cunningham WE. The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2007;21:584–592. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth AE, Lally MA, Choko AT, Inwani IW, Fortenberry DJ. HIV testing and linkage to services for youth. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(suppl 1):9433. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.2.19433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin J, Flicker S, Koleszar-Green R, Mintz S, Dagnino M, Mitchell C. HIV risk, systemic inequities, and Aboriginal youth: Widening the circle for HIV prevention programming. Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique. 2007;98:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF03403708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW. Sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24(4):315–325. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW, Chavis DM. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14(1):6–23. [Google Scholar]

- McNall MA. Evaluating systems change: Casting a wider net using ripple effects mapping. Unpublished document 2017 [Google Scholar]