Abstract

There is currently no effective medical therapy for men with infertility due to oligoasthenozoospermia (OA). As men with abnormal sperm production have lower concentrations of 13-cis-retinoic acid in their testes, we hypothesized that men with infertility from OA might have improved sperm counts when treated with isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid).We conducted a single-site, single-arm, pilot study to determine the effect of therapy with isotretinoin on sperm indices in 19 infertile men with OA. Subjects were men between 21 and 60 years of age with infertility for longer than 12 months associated with sperm concentrations below 15 million sperm/ml. All men received isotretinoin 20 mg by mouth twice daily for 20 weeks. Subjects had semen analyses, physical examinations and lab tests every four weeks during treatment. Nineteen men enrolled in the study. Median (25th, 75th) sperm concentration increased from 2.5 (0.1, 5.9) million/ml at baseline to 3.8 (2.1, 13.0) million/ml at the end of treatment (p=0.006). No significant changes in sperm motility were observed. There was a trend towards improved sperm morphology (p=0.056). Six pregnancies (three spontaneous and three from ICSI) and five births occurred during the study. Four of the births, including all three of the spontaneous pregnancies, were observed in men with improvements in sperm counts with isotretinoin therapy. Treatment was well tolerated. Isotretinoin therapy improves sperm production in some men with OA. Additional studies of isotretinoin in men with infertility from OA are warranted.

Keywords: Male Infertility, 13-cis-retinoic acid, spermatogenesis, spermatogonial differentiation, semen analysis

Introduction

Infertility affects 10–15% of couples attempting to conceive, with roughly one million couples seeking medical assistance for infertility yearly in the US (Chandra et al. 2013). Infertility attributable to the male partner accounts for 40% of infertility, and the most common forms of male infertility involve impairments in sperm production (Jequier & Holmes, 1993). Unfortunately, 75% of men with infertility from oligozooasthenospermia (OA) do not have a medically or surgically treatable cause (Punab et al. 2017). In such men, in vitro fertilization coupled with intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) can treat infertility (Schlegel, 2009); however, these procedures are expensive and unsuccessful in some cases. Therefore, new approaches to the treatment of infertility in men with OA are needed.

For almost a century, it has been known that vitamin A deficiency causes male infertility due to impaired sperm production (Wolbach & Howe, 1925). Vitamin A is converted to its active form, retinoic acid, in the testes via the activity of retinol and retinal dehydrogenases (Napoli, 1996). In vitamin A/retinoic acid deficient rodents, the conversion of undifferentiated to differentiating spermatogonia is arrested, and re-supplementation with vitamin A or retinoic acid restores spermatogenesis and fertility (Van Pelt & de Rooij, 1990 & 1991). The effects of vitamin A on spermatogenesis are dependent on retinoic acid receptors (Doyle et al. 2007, Anderson et al. 2008, Chung et al. 2009), and genetic deletion of these receptors in mice results in sterility secondary to impaired sperm production (Lohnes et al., 1993; Lufkin et al., 1993; Kastner et al., 1996; Ghyselinck et al., 2006). Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of retinoic acid biosynthesis (Amory et al. 2011, Paik et al. 2014), or blockade of retinoic acid receptors (Schulze et al. 2001, Chung et al, 2011) suppresses sperm production in animals.

To understand the relationship between intratesticular retinoic acid and sperm production in man, we measured tissue concentrations of all-trans and 13-cis-retinoic acid in testicular tissue from 24 men undergoing scrotal surgery, and found that concentrations of 13-cis-retinoic acid were significantly reduced in the men with abnormal sperm production (Nya-Ngatchou et al. 2013). This finding suggested that some men with infertility might have reduced concentrations of retinoic acid in their testes, possibly due to deficient biosynthesis. Indeed, follow-up work demonstrated that men presenting with infertility had significantly reduced levels of ALDH1A2, an enzyme that produces retinoic acid, in their testes compared to fertile men (Amory et al. 2014). If some men with infertility have reduced concentrations of intratesticular retinoic acid, treatment with retinoic acid might improve their sperm output and their fertility.

The medical literature supports the notion that the administration of 13-cis-retinoic acid is beneficial for sperm production. Four cohort studies, enrolling a total of 126 normal men being treated with isotretinoin for acne have examined the effects of 13-cis-retinoic acid/isotretinoin on sperm production (Vogt & Ewers 1985, Torok et al. 1987, Hoting et al. 1992, Cinar et al. 2016). Unexpectedly, men in the three of the studies exhibited significant improvements in their sperm counts during treatment. Unfortunately, these observations were not widely recognized, and isotretinoin was never tested as a possible treatment for male infertility.

Oral 13-cis-retinoic acid in the form of isotretinoin is currently approved for the treatment of acne and other dermatological conditions, and its dosing and side effect profile are well known (Kerr et al, 1982, Brazzell et al. 1983, Biesalski 1989, Mundi et al. 2008). To determine the effect of isotretinoin on sperm production in men with infertility, we conducted a single-arm pilot study in nineteen men with infertility from oligoasthenozoospermia (OA). We hypothesized that treatment with isotretinoin for twenty weeks would improve sperm production in these men.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Study Design

As isotretinoin had not previously been studied for the treatment of male infertility, we opted for a simple, single-arm pilot study design with the subject’s baseline semen analyses serving as their own controls. The subjects were infertile men between 21–60 years of age with a sperm concentration of less than 15 million/ml on two baseline samples and more than twelve months of infertility. Men were recruited from Seattle area infertility clinics using informational flyers and were reimbursed for expenses related to study participation. Exclusion criteria included: genetic causes of infertility (e.g. Klinefelter’s or Y-chromosome microdeletions), hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, the use of anabolic steroids or illicit drugs within the last 12 months, consumption of more than 4 alcoholic beverages daily, use of illicit drugs, therapy with isotretinoin or all-trans-retinoic acid in the last 12 months, severe mental health problems requiring medications, a score of greater than 15 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) questionnaire, abnormal serum chemistry values according to our laboratory normal values indicative of liver or kidney dysfunction, current therapy with tetracycline, phenytoin, rifampin, phenobarbital, highly-active anti-retroviral therapy or other inducers of CYP enzymes, infection with HIV, a history of inflammatory bowel disease, or fasting serum triglycerides of greater than 500 mg/dl. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington and conducted under IND#120703 from the US FDA and registered on clinicaltrials.gov as trial #NCT02061384: “A Pilot Trial of 13-cis-retinoic acid (Isotretinoin) for the Treatment of Men With Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia” prior to any study procedures.

Procedures

Prior to participation, subjects signed an Institutional Review Board approved informed consent document. At each study visit, an examination and vital signs were performed. In addition, a blood sample was obtained for the blood counts, serum chemistries and fasting lipids, testosterone, LH, FSH and retinoic acid after an overnight fast. In addition, subjects completed the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire at each visit. For assessment of spermatogenesis, subjects provided two baseline semen samples after 48 hours of abstinence and at least one week apart to confirm the diagnosis of idiopathic oligoasthenozoospermia (OA). They also provided a third semen sample prior to starting therapy and every four weeks during the twenty week treatment phase, as well as 4,12 and 24 weeks after completing therapy. During the treatment phase, subjects were prescribed isotretinoin at a dose of 20 mg twice daily for 20 weeks (the dose prescribed for acne treatment). Subjects were not blinded to the results of their semen analyses. Subjects eleven through nineteen also received calcitriol at a dose of 0.25 micrograms twice daily to see if this would improve sperm motility or have an additive effect on sperm production. Medication compliance was monitored by self-reported subject logs and pill counts of returned medication. In addition, subjects were assessed for side effects at each clinic visit. Serum samples for measurements of retinoic acid were collected before the morning dose. Blood was collected into vacutainers wrapped in aluminum foil to prevent light exposure that could degrade retinoic acid, and allowed to clot for 30 minutes at room temperature before centrifugation at 1000–2000g for 15 minutes. Following centrifugation, the serum samples were decanted and frozen in light-protected vials at –80°C until analysis. Semen samples and seminal plasma samples were similarly light protected.

Measurements

Semen samples were allowed to liquefy for 30–60 minutes at 37°C and then analyzed for sperm concentration, count and motility within sixty minutes of liquefaction using the WHO protocol (WHO, 2010). Sperm morphology was assessed using the “strict” WHO criteria. Specifically, semen was allowed to liquefy for 20–30 minutes at 37oC; volume, pH, viscosity and liquefaction were measured, and samples were then analyzed for sperm concentration, count and motility within 10–20 minutes of liquefaction using the 5th edition WHO protocol (WHO, 2010). Sperm morphology was assessed using “strict morphology” WHO criteria. Sperm motility was assessed by phase-contrast wet mount, accounting for overall % motility, % progressive motility and % rapid linear motility of at least 100 and typically 200 sperm. When needed due to low sperm concentration, semen was diluted no more than 1:1 in Hepes, gently centrifuged at 250 x g for 7 minutes, and supernatant was removed to leave 50–100 microliters which was thoroughly mixed prior to motility analysis and concentration assessment. For sperm concentration, 10 or 20 microliters of semen or concentrated sperm was measured by positive displacement pipette and diluted with a known volume of distilled water to inhibit motility. Sperm concentration was measured in Improved Neubauer Phase hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific Co., Horsham, PA) after correcting for centrifugal concentration and dilution. Blood counts and serum chemistry and hormone tests were performed by the clinical laboratory at the University of Washington.

Retinoid concentrations were measured as described previously (Arnold et al. 2012). Specifically, serum 13-cis, all-trans and 4-oxo-13-cis-retinoic acid concentrations were measured using an AB Sciex (Framingham, MA) qTrap 5500 mass spectrometer equipped with an Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA) 1290 Infinity ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography system as described previously. Deuterated (d) compounds were used as internal standards. To prepare samples for analysis, 80 μL of 250 nM 13-cis-retinoic acid-d5, 500 nM 4-oxo-all-trans-retinoic acid-d3, and 100 nM all-trans-retinoic acid-d5 were added as internal standards in acetonitrile to 80 μL of the samples. Samples were then centrifuged twice at 3,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected for quantification. Retinoic acid concentrations in seminal plasma were measured using an AB Sciex (Framingham, MA) qTrap 6500 mass spectrometer coupled to a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) LC-20AD liquid chromatography system using the approach described above. Retinoic acid species were separated with an Ascentis® Express RP-Amide 15 cm x 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm column (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with a mobile phase flow of 500 μL/min and solvents A: 60:40 water:methanol and B: 60:40 acetonitrile:methanol with 0.1% formic acid in A and B. The gradient was 0→2 min 40% B, 2 → 10 min increase to 55% B, 10→17 min further increase to 90% B, then 95% B hold for 3 min before return to initial conditions and column equilibration for 4 min. For detection, positive mode atmospheric pressure chemical ionization was used and m/z transitions of: 301→205 for 13-cis-retinoic acid and all-trans-retinoic acid, 315→159 for 4-oxo-13-cis-retinoic acid, 306→116 for 13-cis-retinoic acid-d5 and all-trans-retinoic acid-d5, and 300→226 for 4-oxo-all-trans-retinoic acid-d3 were monitored for quantification. All data was analyzed using Analyst software (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA). The intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation were between 2–8%, and the lower limit of quantitation was 2 nM for 13-cis-retinoic acid and all-trans-retinoic acid and 8nM for 4-oxo-13-cis-retinoic acid.

Statistical Analysis

Due to the variability of single measurements of sperm counts, for analysis of the change in total motile sperm count (the primary endpoint), the three pre-treatment semen samples were averaged for the “baseline” value and the three semen samples from treatment week 16, treatment week 20 and follow-up week 4 were averaged for the “end-of treatment” value. For the three men who discontinued isotretinoin therapy early, data from the last three available sperm samples were carried forward and used in the analysis. Secondary endpoints included sperm concentration, sperm motility, and sperm morphology, as well as changes in laboratory measures, serum and semen retinoic acid concentrations, mood effects and other side effects. Inclusion of nineteen men was predicted to confer an 80% power to detect a 33% increase in sperm concentration between baseline and the end of treatment, allowing for a drop-out rate of 10% at an alpha of 0.05.

Baseline and end of treatment sperm parameters were compared using Wilcoxon sign-rank tests due to non-normality. For analysis of laboratory assessments, retinoic acid concentrations and questionnaire data, a paired t-test was used. For endpoints with repeated measures, an adjusted p-value of 0.01 was used to correct for multiple comparisons. In exploratory analyses, univariate and multivariate linear and logistic regression were performed to determine if significant relationships between any patient characteristic, including age, weight, baseline sperm or hormonal parameters or season and changes in sperm parameters or the likelihood of response were present. All analyses were performed using STATA Version 10.0 (College Park, TX, USA). For unadjusted comparisons, an alpha of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Subjects

Twenty-seven subjects were screened and nineteen were enrolled. Six men were ineligible due to sperm criteria, and two subjects elected not to participate for personal reasons. Nineteen men enrolled and started treatment. The mean (±SD) age was 35 ± 4.6 years of age, and the mean body-mass index was 28 ± 4.9 kg/m2. Eighteen of these men were White, and one was Asian. Sixteen men completed all study procedures and three men discontinued treatment early, all after twelve weeks of treatment. Two of these men discontinued due to a pregnancy in their partner, one man discontinued due to a perceived lack of efficacy.

Semen Parameters

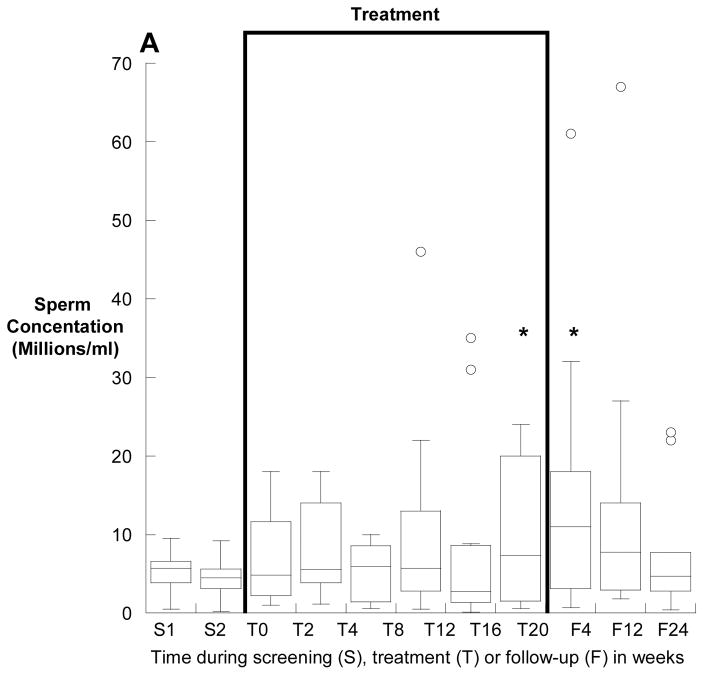

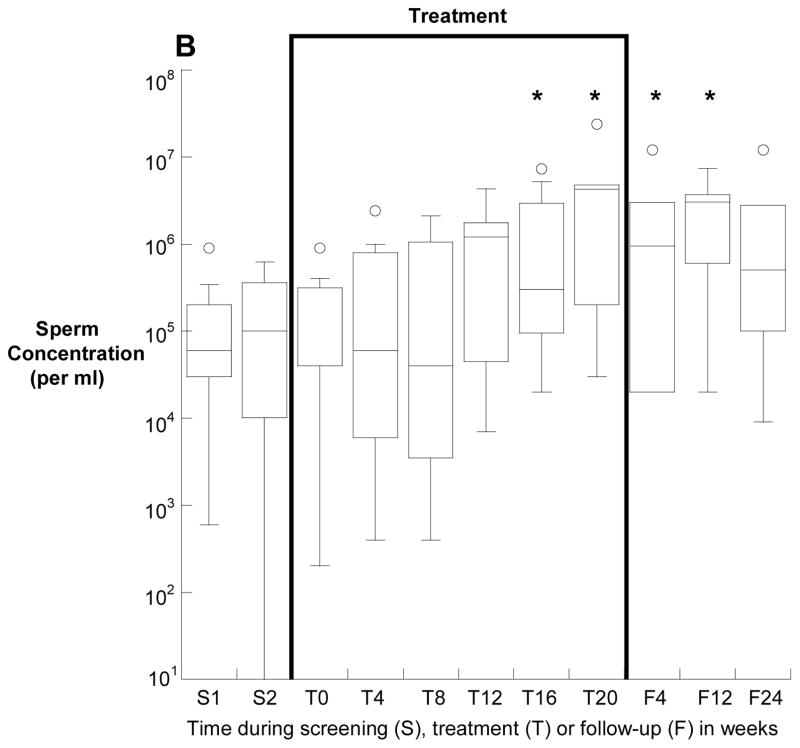

Overall, the median (25th, 75th) sperm concentration increased from 2.5 (0.1, 5.9) million/ml at baseline to 3.8 (2.1, 13.0) million/ml at the end of treatment (p=0.006). Four subjects had a sperm concentration of greater than 15 million/ml at some point between week 16 of treatment and week four of follow-up, compared with no subject at baseline (p<0.001). Sperm concentrations before, during and after treatment for the 12 subjects who had a baseline total sperm count of greater than one million are depicted in Figure 1A and for those with a baseline count of less than one million in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Sperm concentation (medians, interquartile ranges) before, during and after treatment with isotretinoin for twenty weeks. Panel A depicts the twelve men with a baseline total motile sperm count of greater than one million, and panel B depicts the seven men with fewer than 1 million total, motile sperm at baseline. Note the log scale of the y-Axis of panel B. *p<0.05 compared with baseline.

Median sperm motility did not significantly differ between baseline and treatment at any timepoint (Supplementary Figure 1). Due to low sperm counts in some subjects, sperm morphology was only available on ten subjects at baseline and thirteen subjects at week 20. Among these men, there was a trend towards improved sperm morphology with 0.5 (0, 3) percent strict normal sperm at baseline compared with 1 (0, 5) percent at the end of treatment (p=0.056) (Supplementary Figure 2).

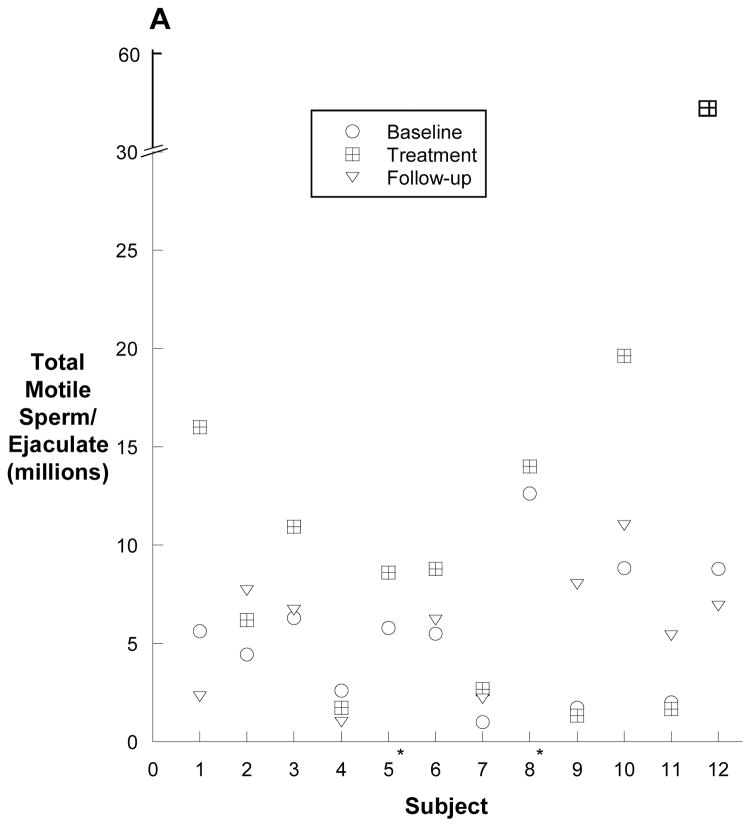

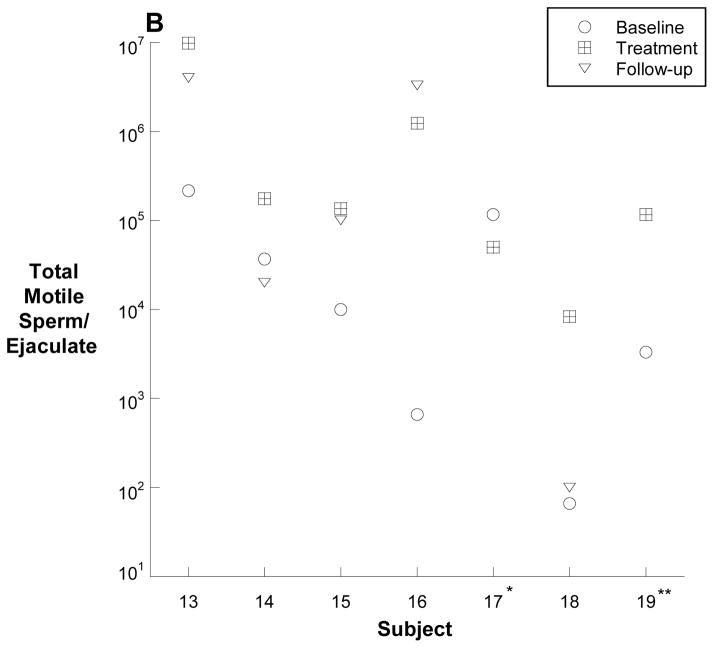

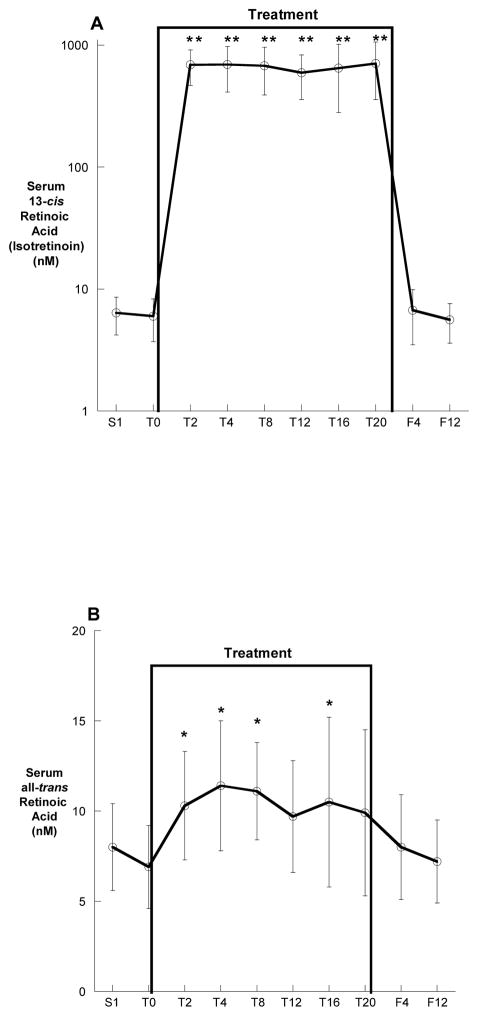

The numbers of total motile sperm before, during and after treatment for all 19 men are depicted individually in Figure 2A and 2B. Overall, the median (25th, 75th) total, motile sperm count per ejaculate increased from a baseline of 2 (0.04, 5.8) million sperm to 2.7 (0.18, 10.9) million sperm after 20 weeks of treatment (p=0.004).

Figure 2.

Total motile sperm counts for each subject. The baseline and treatment values are an average of three semen samples prior to or during treament. The follow-up values are an average of the two semen samples obtained 12 and 24 weeks following treatment. Panel A depicts the twelve men with a baseline total motile sperm count of greater than one million, and panel B depicts the seven men with fewer than 1 million total, motile sperm at baseline (B). Panel C shows the percent change in total motile sperm between baseline and the end of treatment. Note the log scale of the y-axis of panel B. * no follow-up sample; ** follow-up sample with total, motile sperm count of zero.

In the twelve men who began with an average total motile count between 1 and 10 million, the median baseline total motile sperm count increased from 5.6 (2.3, 7.5) million sperm to 8.7 (2.2, 15) million sperm (p<0.001). Subject #12 increased from an average baseline total motile sperm count of 8.8 million sperm to an average total motile sperm count of 56 million sperm by the end of treatment.

In the seven men who began the study with a total motile count of less than one million, the total motile sperm count increased from 0.01 (0.0006, 0.12) million sperm to 0.13 (0.05, 1.2) million sperm (p=0.04) at the end of treatment. One of these men, subject #13, increased from a baseline of 0.2 million sperm to a peak of 26 million sperm after 16 weeks of treatment.

The percent change in total motile sperm count with treatment is depicted in Figure 2C. Overall, the median (25th, 75th) percent change in all 19 men was a 122 (10, 1266) percent increase.

Pregnancies

Six pregnancies and five births occurred in the female partners of men enrolled in the study. Three of the six pregnancies were spontaneous, and three were the product of ICSI. Four of the six pregnancies, including all three spontaneous pregnancies, were observed in men with improvements in sperm concentrations with isotretinoin therapy. Two of the three men (subjects #5 & #8) who fathered spontaneous pregnancies discontinued isotretinoin use when pregnancy was identified after 12 weeks of treatment. The third subject with a spontaneous pregnancy (subject #12) fathered twins after approximately 16 weeks of therapy. There was one miscarriage in the partner of subject who had become pregnant via ICSI. All six offspring from the five pregnancies appeared normal at birth without identifiable birth defects and continue to do well.

Serum and Semen 13-cis-Retinoic Acid

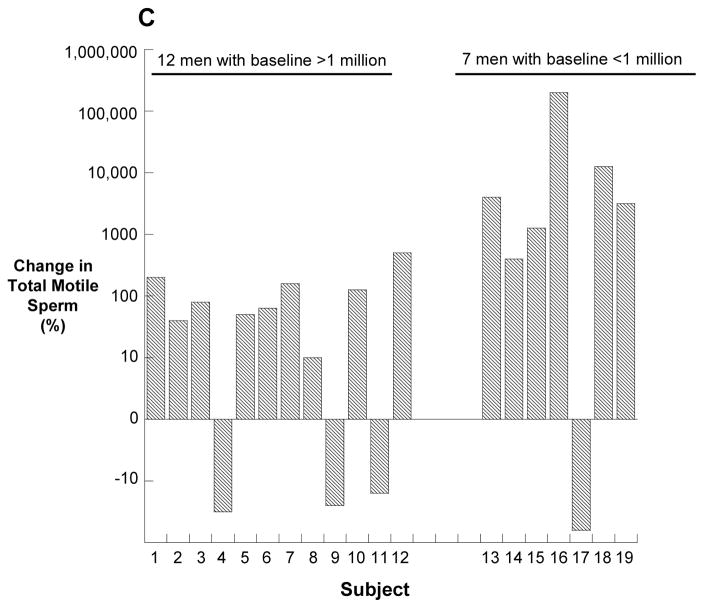

The average serum 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin) and all-trans-retinoic acid concentrations before, during and following treatment are shown in Figure 3A and 3B. The mean (± SD) serum 13-cis-retinoic acid concentrations during treatment was 693 ± 201 nM, which was more than one hundred times higher than the baseline measurement of 6.7 ± 2.3 nM (p<0.0001). In contrast, the average all-trans-retinoic acid concentration of 10.2 ± 2.1 nM was only 30–40% higher than the mean baseline values of 6.7 ± 2.3 nM (p<0.001). Subjects also had marked increases in the 13-cis-retinoic acid metabolite serum 13-oxo-cis-retinoic acid during treatment which increased from 28 ± 7.5 nM at baseline to an average of 5418 ± 1710 nM during treatment (p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Serum 13-cis-retinoic acid (A) and all-trans-retinoic acid (B) concentrations before, during and after treatment. All values are means ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with baseline.

Seminal plasma 13-cis-retinoic acid concentrations were undetectable at baseline and after treatment. During treatment, the average seminal 13-cis retinoic acid concentration was 9.6 ± 2.4 nM. The highest measureable value in any subject at any timepoint was 22 nM. Seminal all-trans-retinoic acid concentrations were undetectable in any subject at baseline and after treatment. During treatment, only seven of 122 semen samples had a detectable concentration of all-trans-retinoic acid. These concentrations ranged from a 2.4 to 3.1 nM.

Adverse Events

There were 59 adverse effects reported by fifteen different subjects during treatment (see supplementary Table 1). A significant increase in mean fasting serum triglycerides and a significant decrease in mean serum HDL were noted during treatment (Table 1). There were no symptoms or clinical events attributable to these changes in serum lipids. Lastly, no subject complained of worsening mood during treatment, and there were no instances of depression during treatment.

Table 1.

Vital signs, laboratory assessments and mood assessments before during and after treatment with Isotretinoin 20 mg twice daily for twenty weeks (n=19). All data are expressed as means ± SD.

| Treatment | Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 4 | Week 12 | Week 20 | Week 12 | Week 24 | |

| Vital Signs | ||||||

| Weight (kg) | 93 ± 16 | 92 ± 16 | 92 ± 15 | 91 ± 17 | 92 ±16 | 93 ± 18 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128 ± 33 | 129 ± 14 | 130 ± 11 | 125 ± 14 | 124 ± 10 | 129 ± 17 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80 ± 11 | 81 ±10 | 81 ± 9 | 77 ± 10 | 76 ± 8 | 81 ± 10 |

| Pulse (beats/min) | 72 ± 12 | 75 ± 13 | 74 ± 11 | 73 ± 9 | 72 ± 9 | 73 ± 6 |

| Blood Counts | ||||||

| White Blood Cells (1000s/μl) | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 6.1 ± 1.4 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43 ± 2.7 | 43 ± 2.9 | 43 ± 2.9 | 43 ± 2.7 | 42 ± 2.6 | 43 ± 3 |

| Platelets (1000s/μl) | 219 ± 51 | 232 ± 61 | 224 ± 46 | 219 ± 41 | 215 ± 51 | 224 ± 57 |

| Lipids | ||||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 187 ± 33 | 200 ± 40 | 200 ± 30 | 197 ± 34 | 177 ± 19 | 184 ± 27 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 53 ± 7.7 | 51 ± 8.4 | 48 ± 8* | 48 ± 7.3* | 51 ± 6.4 | 51 ± 8 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 115 ± 30 | 124 ± 34 | 124 ± 23 | 122 ± 30 | 103 ± 20 | 107 ± 28 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 95 ±40 | 130 ±66* | 136 ±87* | 139 ± 52* | 108 ± 52 | 127 ± 61 |

| Hormones | ||||||

| Testosterone (ng/dl) | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 3.9 ± 1.8 |

| LH (IU/L) | 5.6 ± 2.6 | 6.2 ± 2.9 | 5.8 ± 2.2 | 5.4 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ±2.5 |

| FSH (IU/L) | 11 ± 8.1 | 10.5 ± 8 | 9.8 ± 7.0 | 9.0 ± 7.1 | 10.2 ± 7 | 9.2 ± 9.4 |

| Inhibin B (pg/ml) | 49 ± 20 | ND | ND | 54 ± 18 | ND | 45 ± 19 |

| Mood Questionnaire | ||||||

| PDQ-9 Score | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

ND=Not done

p<0.05 compared with baseline.

Factors Associated with Isotretinoin Response

Using univariate and multivariate linear and logistic regression, no demographic, hormonal, sperm, temporal or pharmacokinetic parameter could be identified that was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of responding to isotretinoin therapy, either in terms of improvements in sperm production or the chance of pregnancy.

Effect of Calcitriol

The administration of calcitriol to subjects eleven through nineteen had no apparent effect on any sperm parameter or laboratory measure compared to the men who did not receive calcitriol.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we present data from the first study to test the hypothesis that men with infertility from OA will exhibit increased sperm counts from treatment with 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin). Vitamin A was first studied as a treatment for male infertility from reduced sperm counts in the 1950s, but no benefit was found (Horne & Maddock 1952, Kapadia & Phadke 1959). However, it wasn’t until the 1980s that it was appreciated that the active metabolite of vitamin A, retinoic acid, was the molecule required for sperm production. Indeed, vitamin A therapy could not improve spermatogenesis in men whose intratesticular retinoic acid concentrations were low due to impaired biosynthesis of retinoic acid. As a result, we have focused our work treating men with infertility on retinoic acid, rather than vitamin A.

There are two notable features of the data from this study. Firstly, our results are similar to those seen in normal men receiving isotretinoin therapy for the treatment of acne. Both fertile and infertile men experienced increased sperm counts, but no changes in sperm motility (Vogt & Ewers 1985, Torok et al. 1987, Hoting et al. 1992, Cinar et al. 2016). Secondly, significant increases in sperm production in men receiving isotretinoin are not apparent until after twelve weeks of treatment. This observation is consistent with the role of retinoic acid in spermatogonial differentiation and the 9–12 week maturation period for sperm in humans (Heller & Claremont 1963, Misell et al. 2006). As a result, longer periods of isotretinoin treatment may be of benefit to men with infertility. Lastly, the elevations in sperm concentrations appear to persist for several weeks after drug discontinuation, presumably as the germ cells stimulated to differentiate by retinoic acid complete maturation within the seminiferous tubules.

Mechanism of Isotretinoin Action

During spermatogenesis, pulses of retinoic acid have been shown to move along the seminiferous tubules coincident with the spermatogenic wave (Hogarth et al. 2015). In mice, during stages VII to IX, the endogenous retinoic acid pulse plays a role in several crucial processes, including: spermiation, tight junction remodeling, and the transition of undifferentiated spermatogonia into differentiating spermatogonia, possibly via expression of Sall4a, Stra8 and/or Rec8 (Koubova et al. 2014, Gely-Pernot et al. 2015).

Given what is known about endogenous retinoic acid’s role in spermatogenesis, how does exogenously administered retinoic acid stimulate spermatogenesis in infertile men? Based on our earlier findings, we hypothesize that the biosynthesis of retinoic acid from vitamin A may be impaired in the men with infertility who responded to treatment with isotretinoin, possibly due to lower expression of ALDH1A. In contrast to most tissues, almost none of the retinoic acid in the testes comes from the circulation (Kurlandsky et al. 1995), suggesting that intratesticular retinoic acid is all produced in situ. Previously, our group demonstrated that the biosynthesis of retinoic acid in the human testes correlates strongly with the concentrations of the ALDH1A enzymes (Arnold et al. 2015), which are reduced in the testes of men with infertility (Amory et al. 2014). It has been postulated that the testes is protected from circulating retinoic acid by CYP26, the enzyme that metabolizes retinoic acid to inactive metabolites, in the peritubular myoid and Sertoli cells (Wu et al. 2008), and that this serves, in part, to prevent the premature initiation of spermatogenesis prior to puberty (Bowles et al. 2006).

Our study, using pharmacological doses of retinoic acid, resulted in roughly 100-fold increases in circulating 13-cis-retinoic acid concentrations, which likely overwhelmed the ability of the peritubular myoid and Sertoli cells to prevent exposure of the tubules to circulating retinoic acid. In some men, this may have addressed their increased their intratesticular retinoic acid concentration and stimulated sperm production. Importantly, isotretinoin is not as good a substrate for CYP26, the enzyme that metabolizes retinoic acid, as all-trans-retinoic acid (Topletz et al. 2011), possibly making it a better drug for this indication. In any case, the exact mechanism and pharmaceutical means by which retinoic acid supports spermatogenesis will be the subject of future study.

Safety of Isotretinoin Therapy

Subjects in our study had the expected side effects from isotretinoin, but generally tolerated the treatment well. Isotretinoin is teratogenic, and should never be administered to women at risk of pregnancy without the use of adequate contraception. Importantly, despite many years of use, there is no evidence to suggest teratogenic effect in the children of women who conceived while their husbands were taking isotretinoin. As a result, men using isotretinoin or other retinoids are not required to use condoms for intercourse. This is likely due to the observation that retinoid exposure via semen to female partners of men taking retinoids appears to be so low that it doesn’t alter endogenous retinoid concentrations (Schmitt-Hoffaman et al. 2011).

In our study, we found isotretinoin concentrations in the semen during treatment were all below 25 nM. At this concentration, and assuming complete absorption across the vaginal mucosa, an ejaculate volume of 5 cc would expose a pregnant female partner to approximately 35 nanograms of 13-cis-retinoic acid. This exposure is several orders of magnitude below the chronic 0.5–1.0 mg/kg dose range associated with teratogenicity in humans (Lammer et al. 1985, Rosa 1987). As a result, exposure of a pregnant female partner to isotretinoin via her sexual partner’s semen appears to be negligible.

Variability of Response

A weakness of the study is that we were unable to identify a correlate or biomarker of responsiveness to isotretinoin therapy. One hypothesis would be that men with low baseline concentration or 13-cis-retinoic acid would be more likely to respond to therapy; however, we did not obtain testicular biopsies at baseline in this study. A biomarker that could predict response would be of significant clinical utility in selecting the most appropriate men with infertility for treatment with isotretinoin. Another weakness of the study was our small sample size of nineteen men. As a result, our study was likely underpowered to observe significant changes in endpoints such as morphology. Future studies of isotretinoin in infertile men will need to be larger to determine if morphology is improved with therapy.

Implications for the Treatment of Male Infertility

Because of its widespread use for acne for over 35 years, isotretinoin is widely available. However, before isotretinoin can be incorporated into male infertility treatment algorithms, additional study of its efficacy and safety will be required, and its use outside of controlled, clinical trials is premature. Notably, we choose a dose in the low range of clinical use (approximately 0.5 mg/kg daily) as doses of up to 2 mg/kg daily are sometimes used for the treatment of acne (Del Rosso, 2012), and may be of use for men with infertility. In addition, it is possible longer periods of treatment may result in improved outcomes. Lastly, because sperm parameters are a poor proxy for fertility, live birth rate should be the primary outcome in future studies of isotretinoin therapy for couples with infertility associated with OA. If larger, randomized, placebo-controlled trials demonstrate safety and efficacy, isotretinoin therapy might allow couples in whom the male partner has infertility from OA to conceive spontaneously or use techniques such as intrauterine insemination rather than ICSI. Alternatively, isotretinoin therapy might allow men who don’t currently qualify for ICSI the opportunity to try these procedures to achieve fertility.

Summary

Our pilot study suggests that a significant subset of men with oligoasthenozoospermia respond to isotretinoin therapy with increased sperm output. Additional study of isotretinoin for the treatment of men with infertility from reduced sperm production is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development supported this work through grant K24HD082231 to JK Amory. Ms. Stevison is supported, in part, by the National Institute of Health Pharmacological Sciences Training Program, through grant T32 GM007750. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

The authors would like to thank Ms. Iris Nielsen for coordinating the study, Ms. Erin Pagel for performing the sperm analysis, and Ms. Dorothy McGuinness for performing hormone assays. In addition, the authors would like to thank Dr. Michael Griswold and Dr. William Bremner for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Amory JK, Muller CH, Shimshoni JA, Isoherranen N, Paik J, Moreb JS, Amory DW, Evanoff R, Goldstein AS, Griswold MD. Suppression of spermatogenesis by bisdichloroacetyldiamines is mediated by inhibition of testicular retinoic acid biosynthesis. J Androl. 2001;32:111–119. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.010751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amory JK, Arnold S, Walsh T, Lardone MC, Piottante A, Ebensperger MD, Isoherranen N, Muller CH, Walsh T, Castro A. Levels of the retinoic acid synthesizing enzyme ALDH1A2 are lower in testicular tissue from men with infertility. Fert Steril. 2014;101:960–966. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson EL, Baltus AE, Roepers-Gajadein HL, Hassold TJ, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AMM, Page DC. Stra8 and its inducer, retinoic acid, regulate meiotic initiation in both spermatogenesis and oogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2008;105:14976–14980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807297105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold SL, Amory JK, Walsh TJ, Isoherranen N. A sensitive and specific method for measurement of multiple retinoids in human serum with UHPLC-MS/MS. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:587–598. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D019745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold SL, Kent T, Hogarth CA, Schlatt S, Prasad B, Haenisch M, Muller CH, Griswold MD, Amory JK, Isoherranen N. Importance of ALDH1A enzymes in determining human testicular retinoic acid concentrations. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:342–357. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M054718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biesalski HK. Comparative assessment of the toxicology of vitamin A and retinoids in man. Toxicology. 1989;57:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(89)90161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowles J, Knight D, Smith C, Wilhelm D, Richman J, Mamiya S, Yashiro K, Chawengsaksophak K, Wilson MJ, Rossant J, Hamada K, Koopman P. Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science. 2006;312:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1125691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brazzell RK, Vane FM, Ehmann CW, Colburn WA. Pharmacokinetics of isotretinoin during repetitive dosing to patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;24:695–702. doi: 10.1007/BF00542225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen ED. Infertility and Impaired Fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports. 2013;67:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung SS, Wang X, Wolgemuth DJ. Expression of retinoic acid receptor alpha in the germline is essential for proper cellular association and spermiogenesis during spermatogenesis. Development. 2009;136:2091–2100. doi: 10.1242/dev.020040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung SS, Wang X, Roberts SS, Griffey SM, Reczek PR, Wolgemuth DJ. Oral administration of a retinoic acid receptor antagonist reversibly inhibits spermatogenesis in mice. Endocrinology. 2011;52:2492–2502. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Çinar L, Kartal D, Ergin C, Aksay H, Karadag MA, Aydin T, Cinar E, Borlu M. The effect of systemic isotretinoin on male fertility. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2016;35:296–299. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2015.1119839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Rosso JQ. Face to face with oral isotretinoin: a closer look at the spectrum of therapeutic outcomes and why some patients need repeated courses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle TJ, Braun KW, McLean DJ, Wright RW, Griswold MD, Kim KH. Potential functions of retinoic acid receptor alpha in Sertoli cells and germ cells during spermatogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1120:114–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1411.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gely-Pernot A, Raverdeau M, Teletin M, Vernet N, Feret B, Klopfenstein M, Dennefeld C, Davidson I, Benoit G, Mark M, Ghyselinck NB. Retinoic acid receptors control spermatogonia cell-fate and induce expression of the SALL4A transcription factor. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e100501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghyselinck NB, Vernet N, Dennefeld C, Giese N, Nau H, Chambon P, Vivelle S, Mark M. Retinoids and spermatogenesis: lessons from mutant mice lacking the plasma retinol binding protein. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1608–1622. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heller CG, Clermont Y. Spermatogenesis in man: an estimate of its duration. Science. 1963;140:184–186. doi: 10.1126/science.140.3563.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogarth CA, Arnold S, Kent T, Mitchell D, Isoherranen N, Griswold MD. Processive pulses of retinoic acid propel asynchronous and continuous murine sperm production. Biol Reprod. 2015;92:37. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.126326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horne HW, Maddock CL. Vitamin A therapy in oligospermia. Fert Steril. 1952;3:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)30905-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoting VE, Schutte B, Schirren C. Isotretinoin and acne conglobata: andrological evaluations. Fortschur Med. 1992;23:427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jequier AM, Holmes SC. Primary testicular disease presenting as azoospermia or oligozoospermia in an infertility clinic. Br J Urol. 1993;71:731–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapadia RM, Phadke AM. The role of Vitamin A in male infertility. Indian J Med Sci. 1959;13:436–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kastner P, Mark M, Leid M, Gansmuller A, Chin W, Grondona JM, Decimo D, Krezel W, Dierich A, Chambon P. Abnormal spermatogenesis in RAR beta mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1996;10:80–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerr IG, Lippman ME, Jenkins J, Myers CE. Pharmacology of 13-cis-retinoic acid in humans. Cancer Res. 1982;42:2069–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koubova J, Hu YC, Bhattacharyya T, Soh YQ, Gill ME, Goodheart ML, Hogarth CA, Griswold MD, Page DC. Retinoic acid activates two pathways required for meiosis in mice. PloS Genet. 2014;10:e1004541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurlandsky SB, Gamble MV, Ramakrishnan R, Blaner WS. Plasma delivery of retinoic acid to tissues in the rat. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17850–17857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM, Agnish PJ, Benke PJ, Braun JT, Curry CJ, Fernhoff PM, Grix AJ, Lott IT, Richard JM, Sun SC. Retinoic acid embryopathy. New Eng J Med. 1985;313:837–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohnes D, Kastner P, Dierich A, Mark M, LeMeur M, Chambon P. Function of retinoic acid receptor gamma in the mouse. Cell. 1993;73:643–658. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90246-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lufkin T, Lohnes D, Mark M, Dierich A, Gorry P, Gaub MP, LeMeur M, Chambon P. High postnatal lethality and testis degeneration in retinoic acid receptor alpha mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7225–7229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misell LM, Holochwost D, Boban D, Santi N, Shefi S, Hellerstein M, Turek PJ. A stable isotope-mass spectrometric method for measuring human spermatogenesis kinetics in vivo. J Urol. 2006;175:242–246. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muindi JR, Roth MD, Wise RA, Connett JE, O’Connor GT, Ramsdell JW, Schluger NW, Romkes M, Branch RA, Sciurba FC FORTE Study Investigators. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of all-trans and 13-cis-retinoic acid in pulmonary emphysema patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:96–107. doi: 10.1177/0091270007309701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Napoli JL. Retinoic acid biosynthesis and metabolism. FASEB J. 1996;10:993–1001. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nya-Ngatchou JJ, Arnold SLM, Walsh TJ, Muller CH, Page ST, Isoherranen N, Amory JK. Intratesticular 13-cis-retinoic acid is reduced in men with abnormal semen analyses. Andrology. 2013;1:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2012.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paik J, Haenisch M, Muller CH, Goldstein AS, Arnold S, Isoherranen N, Brabb T, Treuting PM, Amory JK. Inhibition of retinoic acid biosynthesis by WIN 18,446 markedly suppresses spermatogenesis and alters retinoid metabolism in mice. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:15104–15117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.540211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Punab M, Poolamets O, Paju P, Vihljajev V, Pomm K, Ladva R, Korrovits P, Laan M. Causes of male infertility: a 9-year prospective mono-centre study on 1737 patients with reduced total sperm counts. Hum Repro. 2017;32:18–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosa F. Isotretinoin dose and teratogenicity. Lancet. 1987;2:1154. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91588-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlegel PN. Non-obstructive azoospermia: a revolutionary surgical approach and results. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:165–170. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitt-Hoffman AH, Roos B, Sauer J, Brown T, Weidekamm E, Meyer I, Schleimer M, Maares J. Low levels of alitretinoin in seminal fluids after repeated oral doses in healthy men. Clin Exper Derm. 2011;36(supl 2):12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulze GE, Clay RJ, Mezza LE, Bregman CL, Buroker RA, Frantz JD. BMS-189453, a novel retinoid receptor antagonist, is a potent testicular toxin. Toxicol Sci. 2001;59:297–308. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/59.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Topletz AR, Thatcher JE, Zelter A, Lutz JD, Tay SC, Nelson W, Isoherranen N. Comparison of the function and expression of the two retinoic acid hydroxylases CYP26A1 and CYP26B1. Biochem Pharm. 2011;83:149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torok L, Kadar L, Kasa M. Spermatological investigations in patients treated with etretinate and isotretinoin. Andrologia. 1987;19:629–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1987.tb01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Pelt AMM, de Rooij DG. Synchronization of the seminiferous epithelium after Vitamin A replacement in Vitamin A deficient mice. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:363–367. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Pelt AMM, de Rooij DG. Retinoic acid is able to reinitiate spermatogenesis in Vitamin A deficient rats and high replicate doses support the full development of spermatogenic cells. Endocrinology. 1991;128:697–704. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-2-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogt HJ, Ewers R. 13-cis-retinoic acid and spermatogenesis. Der Hautarzt. 1985;36:281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO. Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. 5. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolbach SB, Howe PR. Tissue changes following deprivation of fat soluble A Vitamin. J Exp Med. 1925;42:753–777. doi: 10.1084/jem.42.6.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu JW, Wang RY, Guo QS, Xu C. Expression of the retinoic acid metabolizing enzymes RALDH2 and CYP26 during mouse postnatal testis development. Asian J Androl. 2008;10:569–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.