Abstract

Nanocarriers are versatile vehicles for drug delivery, and emerging as platforms to formulate and deliver multiple classes of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in a single system. Here we describe the fabrication of hydrogel-core and lipid-shell nanoparticles (nanolipogels) for the controlled loading and topical, vaginal delivery of maraviroc (MVC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), two ARV drugs with different mechanisms of action that are used in the treatment of HIV. The nanolipogel platform was used to successfully formulate MVC and TDF, which produced ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels that were characterized for their physical properties and antiviral activity against HIV-1 BaL in cell culture. We also show that administration of these drug carriers topically to the vaginal mucosa in a murine model leads to antiviral activity against HIV-1 BaL in cervicovaginal lavages. Our results suggest that nanolipogel carriers are promising for the encapsulation and delivery of hydrophilic small molecule ARV drugs, and may expand the nanocarrier systems being investigated for HIV prevention or treatment.

Keywords: nanoparticles, liposomes, chemoprophylaxis, maraviroc, TDF

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Nanoparticles have been widely investigated as carrier systems to deliver small molecule drugs and biologics to improve cell or tissue targeting, reduce side effects, control release, and promote intracellular uptake of agents that have sites of action within cells [1,2]. Hydrophobic small molecule encapsulation within nanocarriers has been employed with notable success in numerous clinical applications, most commonly for cancer therapy [2]. Recently, similar nanocarriers that encapsulate and deliver antiretroviral (ARV) drugs have been investigated for application in HIV prevention and therapy [3–7]. Strategies used for topical prevention of sexually transmitted infections have demonstrated that local delivery of ARV drugs to the vaginal mucosa may sustain higher drug concentrations in the genital tract and reduce systemic exposure [8]. Local delivery may also limit off-target effects that result from systemic delivery. However, there are few vaginal dosage forms that have been tested for co-delivery of water-soluble small molecule ARV drugs. Previous groups have shown that formulating drugs within nanoparticles is one strategy being explored for drug delivery to the vaginal mucosa, as a strategy to prolong drug retention in the reproductive organs and reduce systemic delivery of ARV drugs [9]. To date, only a few nanocarriers have been investigated as microbicides, and these have been limited to the delivery of single ARV drugs in most cases. Expanding the number of nanocarriers that are amenable to vaginal mucosal delivery may expand the number of single and combination agents that can be used for topical HIV prevention.

Generally, the most widely investigated nanoparticle systems that have been evaluated for ARV drug delivery include liposomes and polymer nanoparticles. A key advantage to liposomes is the ability to formulate hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs within the lipid shell and aqueous core [10]. Liposomes have been used to formulate hydrophilic and hydrophobic ARV agents such as indinavir and zidovudine within the aqueous core or lipid bilayer at ~3–30% drug encapsulation efficiency [4,11,12]. As an alternative to liposomes, polymeric nanocarriers have also been investigated for formulating ARV drugs. Formulation of hydrophobic ARV drugs such as efavirenz, saquinavir, and dapivirine in polymer-based nanocarriers have shown promising results with high encapsulation efficiencies nearing 100% [5,9]. In contrast, studies evaluating hydrophilic ARV drug delivery (zidovudine and tenofovir) in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly(isobutylcyanoacrylate), and chitosan nanoparticles showed that these systems exhibited encapsulation efficiencies 5 – 10% [13–15]. These studies highlight the capacity of different nanomaterials to formulate a range of physicochemically diverse ARV drugs, and motivate the need for further characterization of nanoparticle systems for ARV drug formulation and delivery.

Nanolipogels are an emerging platform being investigated as an alternative to the more widely used liposomes or polymer nanoparticles. These dual structure nanoparticles have a distinct lipid bilayer encompassing a polymer core and have been synthesized by UV-induced gelation of a hydrogel network within liposomes using various processes [16,17]. In general, the approaches promote gelation within a liposome reactor to generate nanogel particulates, which were subsequently isolated [16–18]. Lipid-shell, polymer-core nanoparticles have been utilized previously for the encapsulation of several types of agents, including small molecule cancer drugs, and small and large proteins in various biomedical applications [19–24]. Nanolipogels have been used to incorporate physicochemically diverse agents within the lipid bilayer and the aqueous core, including a small hydrophobic TGF-β inhibitor and IL-2 protein, for a tumor immunotherapy application [19]. In addition, active loading can be used to drive drugs that are weak bases into the acidic hydrogel core of nanolipogels, where they become entrapped and are less likely to partition across a neutrally charged lipid membrane [24]. This has been shown to result high encapsulation efficiency and provide controlled release of the encapsulated drug. These reasons make nanolipogels an interesting platform to investigate for physical and biological formulation attributes that facilitate ARV drug delivery as topical microbicides for HIV chemoprophylaxis.

Here, we investigate the use of nanolipogels for formulation and mucosal delivery of the hydrophilic ARV drugs maraviroc (MVC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) using nanolipogels. MVC and TDF are two HIV antivirals with distinct mechanisms of action against HIV viral replication. MVC is a small molecule CCR5 antagonist, which specifically inhibits CCR5-dependent viral entry of HIV-1 [25]. In contrast, TDF is a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor and a prodrug of tenofovir. Once internalized, TDF is converted to tenofovir diphosphate, which is the active form of the drug capable of inhibiting reverse transcription [26]. MVC and tenofovir are hydrophilic drugs that have been tested in a range of clinical trials as topical microbicides [8,27–30]. Though tenofovir has been primarily used in clinical trials of microbicides, the prodrug TDF has been investigated in non-human primate models and has shown to protect against infection when released from an intravaginal ring [31]. Specific advantages of TDF include higher cell and tissue permeability and increased potency of up to 100-fold over tenofovir [32]. Additionally, TDF has been shown to protect against vaginal herpes infection, making it an interesting agent for dual protection against two sexually transmitted pathogens [32,33]. Both drugs have been formulated into semi-solid dosage forms for vaginal drug delivery (e.g., rings and gels) for the purposes of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. However, recent research has shown that encapsulation of ARV drugs, such as dapivirine in nanocarriers, improves local retention of drug in the reproductive organs resulting in decreased systemic biodistribution of drug [9]. To this end, we evaluated the utility of nanolipogels for encapsulation and delivery of MVC and TDF.

We observed that nanolipogels exhibited high levels of ARV drug encapsulation and this study demonstrates the biological utility of these vehicles for use in HIV chemoprophylaxis. Specifically, we highlight the potential of ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels to inhibit cell-free and cell-cell HIV-1 infection of TZM-bL cells. Finally, we demonstrate the in vivo application of MVC- and TDF-nanolipogels as a topical vaginal microbicide. The implications of our results support nanolipogels as a system for delivery of hydrophilic ARV drugs for HIV-1 prevention and treatment and worthy of further investigation in future studies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Egg phosphaditylcholine (EPC) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Acrylamide (AAm), N,N′-methylenebis(acrylamide) (MBA), 2,2-diethoxyacetophenone (DEAP), and cholesterol were obtained through Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). MVC was synthesized, purified, and generously donated by the Suydam Lab at Seattle University. TDF was obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (http://www.aidsreagent.org/). Water used in buffer solution was purified using a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). TZM-bL cells, PM-1 cells, CEMx174 cells, and HIV-1 BaL isolate were also obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. Medroxyprogesterone acetate was purchased through the University of Washington pharmacy (Greenstone LLC, Peapack, NJ, USA). Media used in cell culture assays was complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (cDMEM) (Invitrogen), made by supplementing DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone), 5% of 100X Penicillin/Streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 5% of 200 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen).

2.2. Synthesis and preparation of nanolipogels

Nanolipogels were synthesized by modifying previously established methods for photopolymerization of a hydrogel core within a lipid vesicle reactor [16,17]. EPC and cholesterol were dissolved in chloroform at 20 mg/ml and 10 mg/ml. EPC and cholesterol at a mass ratio of 3:1 were transferred to a round-bottom flask, which was attached to a rotary evaporator (Buchi, Flawil, Switzerland) rotating at 120 rpm over a 35°C water bath until all solvent was removed. AAm, MBA, and DEAP were dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCL buffer and used to rehydrate the lipid film to 5 mg lipids/film, forming multilamellar vesicles (MLVs). ARV drugs were dissolved in DI water and were incorporated into the rehydration buffer at 9.1% or 4.77% (w/w) of the total material mass. MVC and TDF were loaded separately. MLVs were extruded with a hand-held needle extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) involving 21 passes with syringes through a 200 nm polycarbonate membrane. This produced unilamellar vesicles (ULVs) ~170–220 nm in diameter, dependent on the presence or absence of drugs. Ascorbic acid was added to a final concentration of 150 mg/ml, at a 200 fold excess of the photoinitiator, to prevent external polymerization during subsequent UV exposure [34]. Particles were vortexed well and exposed to UV light 1-inch below a Blak-Ray ® B-100AP/R High Intensity UV lamp (100 Watts, 365 nm, UVP, Upland, CA) for 15 min on ice. The resulting nanolipogels were purified from unencapsulated materials using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Briefly, columns were equilibrated with 25 mL Milli-Q water, and nanolipogel samples were added to the packed bed in a total volume of 2.5 mL. Nanolipogels were eluted from the column with 3.5 mL of Milli-Q water.

2.3. Nanolipogel size distribution, bilayer dissolution, and mass recovery

Hydrodynamic size and polydispersity (PDI) of nanolipogels was determined by dilution in 10 mM NaCl and quantification by dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a Malvern Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). Dissolution of lipid bilayers and characterization of the nanogel core was performed by incubation of nanolipogels in 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. The efficiency of nanolipogel mass recovery was quantified by freezing and overnight lyophilization of an aliquot of the PD-10 purified samples, and measuring the lyophilized mass using an analytical balance.

2.4. Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy of nanolipogels

Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) samples were prepared by the vitrification-plunging method. Briefly, a 10-μl drop of the sample was applied on a Lacey Carbon grid (TED Pella, Inc., Redding, CA). The drop was blotted and immediately plunged into liquid ethane. Cryo-TEM samples were stored in liquid nitrogen until imaging. Samples were transferred to the microscope using the Gatan 626 cryo-holder (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) and cryo-transfer station. During microscope imaging, the samples were kept at a temperature below −178°C. Cryo-TEM samples were imaged by the Tecnai G2 F20 transmission electron microscope (FEI Co., Hillsboro, OR) at 200kV with a field emission gun, in a low-dose mode to minimize electron-beam radiation damage. A 4K CCD camera (4k Eagle Camera, FEI) was used to record the images.

2.5. Quantification of drug encapsulation and release kinetics

Drug quantification of MVC and TDF was performed using a Prominence LC20AD UV-HPLC (Shimadzu) on a C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and chromatograms were analyzed using the LCSolutions software. Samples for HPLC were prepared by incubation of ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels with 25% isopropyl alcohol (IPA) (v/v) to rupture the lipid bilayer. Methods for MVC detection were adapted as described [35], and consisted of a 15-min isocratic flow method at 1.0 ml min−1 in 26%/74% acetonitrile (ACN)/50 mM KH2PO4 adjusted to pH 3.2 with formic acid. The injection volume was 20-μl and the oven temperature was maintained at 44°C. MVC was detected at 193 nm at a retention time of 8–9 min. MVC was quantified using standards made in Milli-Q water. TDF was detected using a 15-min isocratic flow method at 1.0 ml min−1 in 28%/72% H2O with 0.045% trifluoracetic acid/ACN with 0.036% TFA. The injection volume was 10-μl and the oven temperature was maintained at 30°C. TDF was detected at 259 nm at a retention time ~12-min. Drug loading was calculated using drug concentrations, as measured by HPLC and particle material recovery, as measured using the analytical balance. Drug and encapsulation efficiency were calculated using the following equations were used to calculate drug loading and encapsulation efficiency:

Drug release from nanolipogels was determined by placing suspensions in membrane-capped dialysis tubes with a 1-kDA molecular weight cutoff (GE USA). The tube was inverted into 5 ml of DI water (MVC) or 10 mM NaCl, pH 4 (TDF) in a 50 ml Falcon tube, which was placed on an orbital shaker rotating at 120 rpm at 37°C. At various timepoints over 24 hours, release buffer was collected and analyzed for drug content by HPLC.

2.6. Cell viability

TZM-bL cells were cultured in 96 well plates in the absence or presence of various concentrations of blank and drug-loaded nanolipogels ranging from 0.0625 – 2 mg/ml. After three days in culture, cell viability was assessed using a CellTiter-Blue® Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Cells were incubated for 4h with 20μl/well of CellTiter-Blue®Reagent and fluorescence was recorded at 560/590nm using a TECAN plate reader (Männedorf, Switzerland).

2.7. Evaluation of ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels against cell-free HIV-1 infection

The antiviral activity of MVC, TDF, and ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels were assessed based on a reduction in luciferase reporter gene expression after infection of TZM-bL cells with HIV-1 BaL. Briefly, TZM-bL cells were seeded at a concentration of 1×104 per well in 96-well microplates. The next day, TZM-bL cells were incubated with various concentrations of free ARV drugs or ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels, alone and in combination, at 37°C for 1h prior to virus exposure. Cell-free HIV-1 BaL (200 TCID50) was added to the cultures and incubated for an additional 48-hours. Untreated cells were used as control representing 100% infection. The Promega™ Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) was used to determine luciferase expression. Antiviral activity was expressed as an IC50 value, which is the sample concentration giving 50% of relative luminescence units (RLUs) compared to the virus control after subtraction of background RLUs. Quantification of IC50 values was performed using GraphPad Prism.

2.8. Evaluation of ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels against cell-cell HIV-1 transmission

For cell-cell transmission assays, TZM-bL cells were seeded at a concentration of 1×104 per well in 96-well microplates. The next day, TZM-bL cells were incubated with various concentrations of free ARV drugs or ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels, alone and in combination, at 37°C for 1h to exposure to chronically infected PM-1 cells. Chronically infected PM-1 cells were generated by culturing cells for three days in the presence of HIV-1 BaL. PM-1 cells were washed twice with PBS to remove cell-free HIV-1 BaL before they were added to the TZM-bL cell culture at 5×103 cells/well. After a 1-hour incubation, PM-1 cells were removed by washing wells twice with PBS. TZM-bL cells were then incubated in the presence of the same ARV drug treatment for an additional 48-hours. Cells were lysed and the luciferase activity of the cell lysate was measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega, Fitchburg, WI). Antiviral activity was expressed as an IC50 value as described above.

2.9. In vivo administration and determination of antiviral activity in cervicovaginal lavages (CVLs)

Female C57BL/6J mice (8–12 weeks) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Four days prior to topical administration of drug-loaded nanolipogels, mice were subcutaneously injected with 100-μl of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera®) formulated at 20 mg/ml in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS). Progesterone treatment of female mice to induce diestrus reduces variability resulting from biological and physiological differences at various stages of the estrus cycle. Mice were anesthetized in an induction chamber and taped around the abdomen with Fisherbrand tape (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) to prevent self-grooming after vaginal administration. Vaginal tracts were flushed out three times with 80-μl of endotoxin-free water and two Calginate swabs were used to remove the mucus. MVC-nanolipogels in combination with TDF-nanolipogels were premixed and delivered at 5 μg/drug in a total volume of 25-μl. Unformulated MVC and TDF were delivered in combination at the same drug concentrations. 25 μl of sterile PBS was administered to mice as a control group. Post-administration, mice were inverted for 10-min in the induction chamber to enhance vaginal retention of administered materials. Mice were caged individually to prevent grooming between animals. 24-hours after vaginal administration, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. CVLs were collected postmortem with 4–50 μl lavages in PBS or cDMEM. HPLC was performed on PBS lavages to detect MVC and TDF using methods described in Section 2.5. cDMEM lavages were combined and used in TZM-bL antiviral assays against cell-free HIV-1 BaL, as described previously. All animal studies and protocols were approved and monitored by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.10 Statistics

All statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism 6. Data for dynamic light scattering were plotted as geometric mean and SEM. Release data points, dose-response curves, and in vivo CVL dose-response curves were plotted as geometric mean with error bars showing standard deviation. Antiviral activity data was transformed to a log scale and normalized using 0% HIV-1 inhibition (virus only positive control) and 100% HIV-1 inhibition (cells only negative control). Normalized data was analyzed to calculate IC50 values by performing nonlinear regression and using the log(inhibitor) vs. response – Variable slope (four parameter) equation.

3. Results

3.1. Synthetic strategy and physical characterization of nanolipogels

We report here significant improvements to existing methods for fabricating nanolipogels with controlled size and low polydispersity. We demonstrate that our optimized approach reproducibly fabricates nanolipogels loaded with MVC or TDF. Hydrogel constituents and ARV drugs were combined within liposome, followed by UV exposure to induce crosslinking and formation of a hydrogel core (Figure 1). The resulting particles were purified to remove unencapsulated materials and yield ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels. Although previous approaches to fabricate nanolipogels report on bath sonication to produce homogenous particle populations [16], we found that these methods resulted in particles with a high polydispersity (PDI > 0.6, data not shown). Instead, we used needle extrusion to produce uniform particles with a hydrodynamic diameter ~170 nm and a narrow PDI <0.1 (Table 1). Incorporation of either MVC or TDF resulted in drug-loaded nanolipogels of slightly larger size and PDI than blank (drug-free) particles. We found that dilution, as reported by others [16], and ultracentrifugation to purify the nanolipogels from residual polymerizable excipients and unencapsulated ARV drug were ineffective. In contrast, we added ascorbic acid prior to UV exposure to effectively quench external polymerization, and then used a desalting column as a final purification step to isolate nanolipogels from any remaining unencapsulated small molecule excipients.

Figure 1. Synthetic strategy.

Nanlipogels (NLGs) are formed by resuspension of a lipid film with polymer constituents, photoinitiator, and drug. The resulting multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) are needle extruded to form unilamellar vesicles (ULVs), Ascorbic acid is added to prevent external polymerization, and ULVs are placed 1-inch under a UV-light source for 15 min to form nanolipogels (NLGs). NLGs are purified through a PD-10 column to remove unencapsulated materials.

Table 1. MVC- and TDF-nanolipogel particle characterization.

Size and polydispersity of drug-loaded NLGs were measured by dynamic light scattering. All values are represented as mean ± s.d. from three independently synthesized nanolipogel batches.

| Unpolymerized ULVs | Polymerized NLGs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Samples | Blank | MVC | TDF | Blank | MVC | TDF |

| ULVs | ULVs | ULVs | NLGs | NLGs | NLGs | |

| Size (d, nm) | 171.8 | 196.1 ± 5.5 | 218.5 ± 23.9 | 141.3 | 163.5 ± 6.3 | 164.7 ± 5.8 |

| PDI | 0.093 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.094 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.1 ± 0.02 |

| % Particle mass recovery* | - | - | 7.8 ± 6.4 | 15.4 ± 1.9 | ||

| % Encap. efficiency** | - | - | 40.3 ± 12.7 | 17.0 ± 5.9 | ||

| % Theoretical drug loading | - | - | 9.10 | 4.77 | ||

| % Drug loading ** | - | - | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | ||

Measured by lyophilization of nanolipogel samples and massing with an analytical balance

Measured by reverse phase UV-HPLC after rupturing the lipid bilayer by incubating particles with 25% IPA. All values represented as mean ± SD from three independently synthesized batches.

DLS was used to evaluate the presence of the hydrogel core and the size distribution of particles at different stages of the nanolipogel synthesis. Lipid bilayers can be stripped using detergents such as Triton X-100 to expose the hydrogel core [16,17], which is a common technique to isolate the nanogel core from the lipid-shell. After incubation of MVC- or TDF-nanolipogels with 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, we observed a mixed micelle population (~10 nm) and a separate nanogel peak (~200 nm) by DLS (Figure 2). These results support the existence of a hydrogel-core interior surrounded by a lipid vesicle. The hydrodynamic diameter of unpolymerized MVC ULVs and TDF ULVs were 196 nm and 218 nm (Table 1). Following polymerization and purification with a desalting column, the resulting MVC-nanolipogels and TDF-nanolipogels were ~160–170 nm with a low PDI ~0.1.

Figure 2. Hydrogel core characterization by detergent removal of lipid bilayer.

Presence of hydrogel-core, lipid-shell particles was characterized by dynamic light scattering. Nanolipogels (NLGs) were incubated with 1% TX-100 for 10 min at room temperature to facilitate removal of the lipid bilayer, creating a mixed micelle (MM) population and a nanogel population. All values are represented as mean ± SEM from three independently synthesized nanolipogel batches.

We investigated lyophilization as a storage condition for our ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels. However, we found that resuspension of lyophilized nanolipogels produced significantly aggregated particles of 400–600 nm diameter with a high PDI of 0.4 (MVC-nanolipogels) and 0.3 (TDF-nanolipogels) (data not shown). Lyophilization of the nanolipogels in the presence of a 3% (w/v) sucrose better preserved the original size and PDI of nanolipogels after resuspension. Use of sucrose as a cryprotectant helped preserve particle size for both MVC-nanolipogels (d = 306 nm, PDI = 0.4) and TDF nanolipogels (d = 207 nm, PDI = 0.2) (Supplementary Table 1).

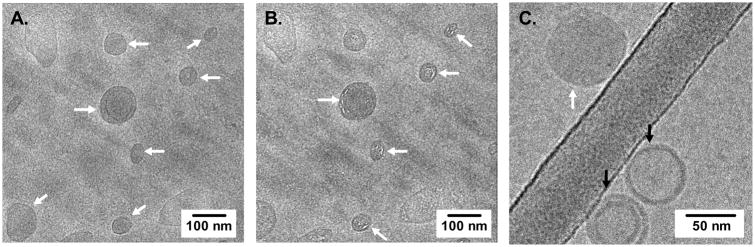

3.2. Cryo-TEM imaging of nanolipogels

Cryo-TEM was used to directly visualize the morphology and core-shell architecture of our nanolipogel carriers. Nanolipogels were identified by cryo-TEM as filled vesicles, with a dense and polymerized core, surrounded by a bilayer structure, indicative of a lipid-shell (Figure 3A, white arrows). In contrast, liposomes were visualized as vesicles with empty or hollow cores (Figure 3C, black arrows). The presence of a vesicle core filled with a polymer network was further probed by continued electron beam exposure, which causes radiation damage to polymers that can be visualized on electron micrographs [36]. We observed white striations in our electron micrographs of nanolipogels that was consistent with radiolysis of organic polymers (Figure 3B). These images support that our synthetic strategy results in the formation of nanolipogels with a dense polymer core and lipid bilayer shell architecture.

Figure 3. Cryoelectron microscopy micrographs of nanolipogels.

Nanolipogels are indicated by white arrows (A), radiation damage from continued electron beam exposure to polymer cores are indicated in white arrows (B), and co-existence of nanolipogels (white arrows) with empty liposomes (black arrows) was observed (C).

3.3. Material recovery and ARV drug encapsulation and release

MVC and TDF were incorporated into nanolipogels at 9.1% and 4.77% (w/w), respectively (Table 1). We used HPLC to quantify the actual drug loading of MVC and TDF from the nanolipogels recovered after synthesis. HPLC of UV exposed but unformulated MVC and TDF showed no change in chromatograms compared to non-UV exposed drugs (Supplementary Figure 1), indicating that the UV polymerization does not alter the drug. Drug quantification of MVC-nanolipogels and TDF-nanolipogels as not confounded by any vehicle excipient or IPA solvent peaks (Supplementary Figure 2). The total mass recovery of MVC-nanolipogels and TDF-nanolipogels was 7.8% and 15.4%. HPLC drug quantification indicated that the drug loading of MVC in nanolipogels was 3.7% (w/w), which corresponds to an encapsulation efficiency of 40.3%. TDF drug loading in nanolipogels was measured to be 0.8% (w/w) for an encapsulation efficiency of 17.0%. These results show that both MVC and TDF were successfully incorporated into nanolipogel vehicles, although TDF showed much lower loading.

MVC and TDF drug release from nanolipogels was measured over 72-hours at 37°C. We found that MVC and TDF release curves were pseudo-linear within between 6–8 hours for both drugs, followed by plateau region that persisted out to 72-hours (Figure 4). We did not observe burst release of drugs from particles, indicating that they were not surface associated but rather completely formulated either within the hydrogel core or lipid bilayer of the nanolipogels. Notably, burst release may be difficult to observe in our in vitro release system, which includes a dialysis membrane that the drug must partition across. We observed a higher overall cumulative percentage release for MVC compared to TDF. We further tested the impact of cholesterol content on drug release from nanolipogels, and found that incorporation of higher levels of cholesterol in the lipid membrane slows release of drugs, particularly maraviroc, from nanolipogels (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 4. Maraviroc and TDF drug release from nanolipogels.

Maraviroc and TDF release from nanolipogels was measured using 1,000 MWCO dialysis tubes inverted into a 50-mL conical containing a sink volume of 5 mL DI water (MVC) and 10 mM NaCl, pH 4 (TDF). Released drug was quantified by reverse phase UV-HPLC. All values are represented as mean ± SD from three independently synthesized nanolipogel batches.

3.4. Cell viability and in vitro anti-HIV activity

To understand the potential biological applications for MVC- and TDF-nanolipogels as microbicides, we measured their toxicity and anti-HIV activity in cell culture. Cell viability was tested in TZM-bL cells and CEMx174 cells. Our results showed that free ARV-drugs were not cytotoxic to either cell type and that drug-free (blank) nanolipogels exhibited little to no cytotoxicity in both cell types at low concentrations (Figure 5). Blank nanolipogels did exhibit toxicity at the highest concentration (2 mg/mL nanolipogels) in TZM-bL epithelial cells. Once loaded with MVC or TDF, we observed a further reduction in cell viability at high particle and drug concentrations. This decrease in cell viability was especially noticeable for MVC nanolipogels in the CEMx174 lymphocytes.

Figure 5. Cell viability of TZM-bL and CEMX174 cells.

TZM-bL (epithelial cell line) and CEMx174 (T cell line) were exposed to blank and drug-loaded nanolipogels, as well as free drugs, and cytotoxicity was assessed using CellTiter-Blue® Cell Viability Assay (Promega). Fluorescence was recorded at 560/590 nm. The corresponding MVC and TDF concentrations used in the assay are indicated on the graph. The range of antiviral activity is indicated in the gray shaded box (A). Blank nanolipogel and drug-loaded NLG values are represented as mean± SD from duplicates. Free drug values are represented as mean± SD from triplicate wells.

Our cell cytoxicity results were used to set the concentration range to perform the antiviral studies that measure HIV-1 BaL infection of TZM-bL cells. We chose ARV-loaded nanolipogels concentrations that exhibited high TZM-bL cell viability such that the measured antiviral activity would be minimally confounded by cytotoxic effects. MVC- and TDF-nanolipogels potently inhibited HIV-1 BaL infection of TZM-bL cells in a dose-dependent manner. In cell-free infection models, MVC nanolipogels displayed an IC50 value of 9.6 nM, which is comparable to the IC50 value of unformulated MVC (10.8 nM). TDF nanolipogels displayed an IC50 value of 7.5 nM, similar to that of unformulated TDF (5.4 nM) (Figure 6A–B). Our results demonstrate that transmission of virus from chronically infected PM-1 cells to TZM-bL cells was much more efficient than cell-free virus infection. As such, both drugs showed a higher IC50 value as compared to the IC50 value in cell-free HIV-1 BaL infection (Figure 6G). As a result of the increased efficiency of infection by cell-cell HIV-1 transmission, MVC nanolipogels displayed an approximately seven-fold increase in the IC50 value (76.9 nM) as compared to TDF-nanolipogels (10.7 nM) (Figure 6D–E). Finally, treatment of TZM-bL cells with MVC nanolipogels and TDF nanolipogels at a molar combination of 1:1 showed minimal dose reduction compared to single ARV drug-loaded nanolipogel treatment groups, and were not significantly different from free drug at a molar combination of 1:1 (Figure 6C, F). Notably, combination treatment in the cell-cell transmission assay reduced the IC50 value by nearly half as compared to treatment with MVC nanolipogels alone. We hypothesize that this reduction is due to the presence of TDF nanolipogels, which exhibit more potent activity than MVC nanolipogels.

Figure 6. Antiviral activity of MVC NLGs, TDF NLGs, and combination treatment against cell-free and cell-associated HIV-1 BaL in TZM-bL cells.

Antiviral activity of drug-loaded single nanolipogel and combinations was assessed based on a reduction in luciferase reporter gene expression after infection of TZM-bL cells with cell free HIV-1 BaL (A–C) and cell associated HIV-1 BaL (D–F). Antiviral activity was expressed as an IC50 value, which was the sample concentration giving 50% of relative luminescence units (RLUs) compared with those of virus control after subtraction of background RLUs. All values represented as mean ± SEM from duplicates. IC50 values of all NLG treatment groups in cell-free and cell-associated antiviral assays are summarized (G). Asterisk (*) indicates that the confidence interval was unable to be calculated.

3.5. In vivo retention of antiviral activity in CVL fluids

To understand the in vivo application of these materials as topical, mucosal microbicides, we evaluated retained antiviral activity in CVLs after intravaginal delivery of ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels in an established female mouse model. Standard progestin-induced diestrous was employed to reduce mouse-to-mouse variability and eliminate cycle-dependent biological variability. MVC and TDF nanolipogels were administered together intravaginally and CVLs were collected 24-hours post-administration. We were unable to measure MVC or TDF in the CVLs analyzed by HPLC. However, we found that combination administration of both drugs resulted in retained antiviral activity in CVLs against HIV-1 BaL (Figure 7). At a dilution of 128-fold, CVLs still provided >60% viral inhibition in vitro, which indicated local retention of drug. Using the previously determined in vitro IC50 values for MVC and TDF in these assays (Figure 6), we were able to quantify the amount of drug retained in CVLs at 24-hours. Retained drug was extrapolated by correlating in vitro IC50 values with the fold-dilution of CVLs that resulted in 50% HIV inhibition. These calculations are based on the assumption that the observed fold loss in IC50 corresponds to the same fold loss in drug concentration between the dose administered and the dose recovered after 24-hours. Using this extrapolation, we determined that ~1.1% of the total drug dose was retained at 24-hours post-vaginal administration. These results are promising and suggest that nanolipogels have potential for use in topical, vaginal delivery of drugs against HIV infection.

Figure 7. Antiviral activity in cervicovaginal lavage fluids (CVLs).

MVC-NLGs and TDF-NLGs were intravaginally administered at 5 μg/drug in a C57BL/6J murine model. 24h-post administration, mice were euthanized and cervicovaginal lavage was collected with 200 μl cDMEM. The antiviral activity in CVL samples was determined using a titer reduction assay with TZM-bl cells. Serial dilutions of CVLs were made and tested for antiviral activity against cell-free HIV infection. Inhibition of infection was determined by luciferase quantification of cell lysates.

4. Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate the successful synthesis and biophysical characterization of ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels for HIV-1 chemoprophylaxis. Our synthetic technique for fabricating nanolipogels was adapted to achieve uniform particle size and removal of unencapsulated material. Previous methods to synthesize nanolipogels using bath sonication typically resulted in a polydisperse particle population ranging in size from 30–300 nm in diameter [16]. Size polydispersity can lead to variability in drug loading and prohibit accurate prediction of drug release, intracellular uptake, and carrier dosing for in vivo applications. To reduce the polydispersity of nanolipogels resulting from bath sonication, we employed needle extrusion through a uniform pore size membrane to produce a homogenous population of particles ~170–220 nm in hydrodynamic diameter and a low PDI < 0.1, which did not change significantly post-polymerization and purification (Table 1). Previous approaches have diluted unpolymerized nanolipogel suspensions in order to prevent external polymerization [16,37]. However, dilution may create concentration gradients across the lipid bilayer, causing hydrogel components to diffuse out of particles [34]. Additionally, dilution of particles does not remove unencapsulated drug, which may confound release studies and dosing for anti-HIV-1 assays. Our results showed that the addition of ascorbic acid post-particle formation, prior to UV exposure, worked well to prevent external polymerization, and was easily removed along with unencapsulated drug using a simple desalting column. Overall, our nanolipogel fabrication strategy to synthesize ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels was highly reproducible and resulted in particles with controlled size and low polydispersity.

In agreement with the work of others, we found that nanolipogels incubated with detergent allowed for removal of the lipid bilayer and revealed a nanogel core near the size of the original nanolipogel population (Figure 2) [16]. Electron microscopy further validated the formation of hydrogel-core and lipid-shell nanolipogels with spherical morphology. However, it is notable that we did observe formation of some liposomes. To our knowledge, previous research on nanolipogel synthesis and drug encapsulation has not described or measured the percentage of liposomes that may coexist with nanolipogels following the different synthesis schemes. The formation of these liposomes may be mitigated by longer polymerization times than are published in the literature, tuning the monomer-crosslinker-photoinitiator ratio, or choosing a different lipid composition that is more restrictive to drug diffusion out of the vesicle core prior to polymerization. Further investigation into these parameters and their impact on efficient polymerization of the hydrogel-core may improve the efficiency of nanolipogel synthesis.

Our results demonstrate that nanolipogels may be used to formulate anti-HIV small molecule anti-HIV drugs that are highly water soluble and difficult to formulate in more common nanocarrier platforms. Both MVC and TDF were encapsulated at relatively high efficiencies for hydrophilic small molecules at 40% and 17%. The higher encapsulation of MVC may have to do with the ionizable group on the drug, which becomes protonated at low pH. The polymer core of nanolipogels has previously been determined to be pH 3 [24]. At a pKa of 7.3 [25], the ionizable amine group of MVC may be protonated, and is less likely to diffuse out of the acidic hydrogel core and traverse the lipid bilayer. This would reduce leakage of small molecules and thereby entrap a greater amount of drug. The hydrogel network may also create a barrier for drug diffusion by decreasing water penetration into the core. While drug loading of MVC and TDF in nanolipogels was sufficient for our biological studies, further optimization may be done to enhance drug loading. Overall, the challenge of loading hydrophilic materials into polymer nanoparticles has been evident in the literature [13–15]. Zidovudine loading in poly (iso-butylcyanoacrylate) nanocapsules and PLGA microcapsules has been shown to be less than 5% and tenofovir drug loading in chitosan nanoparticles was demonstrated to be ~6%. The low drug loading and low encapsulation efficiencies in these studies motivated us to explore a new nanoparticle platform for ARV-drug delivery. Since nanolipogels have been used to load anticancer agents at high encapsulation efficiencies of nearly 90%, we sought to validate this system for encapsulation of antiviral drugs. For example, groups have used strategies such as active loading of pH-sensitive drugs into the nanolipogel core to achieve encapsulation efficiencies of nearly 90% and incorporating 53 μg of an anti-cancer drug per mg of vehicle [24]. However, while active loading may be used for certain classes of drugs with ionizable side groups such as MVC, it may not be useful for small molecules that are not pH-sensitive. Moreover, while we observed medium levels of encapsulation efficiency, drug loading of both drugs was low. Future work must focus on improving ARV-drug loading in our nanolipogel platforms using strategies such as optimization of the lipid bilayer composition, varying the density of the hydrogel core, evaluating active-loading of pH-sensitive ARV-drugs (MVC), or increasing the initial drug to material ratio.

Our results further highlight the advantage of nanolipogels as vehicles to provide release of MVC and TDF on the scale of 6–8 hours. Previous papers that have evaluated the kinetics of hydrophilic drug release from both lipid nanoparticles, report burst release profiles in which most of the drug is released within the first hour [13,38]. Other papers evaluating drug release kinetics from polymeric particles show biphasic release – including an initial burst release phase, which may be due to surface-associated drug [39]. Recent research evaluated the advantages of nanolipogel platforms in direct comparison to liposomes for the loading and release of small molecule anti-cancer drugs [24]. Wang et al. demonstrated that release is more sustained from nanolipogels, and that this was likely due to a combination of the acidic core in conjunction with slower diffusion out of a crosslinked core. Our results support the hypothesis by Wang et al., that the acidic, hydrogel network slows diffusion and partitioning of both drugs out of the core and across the lipid bilayer. We further demonstrate that the inclusion of cholesterol may be used as one strategy to dampen release of certain drugs from the nanolipogel core.

Cellular cytotoxicity of nanolipogel vehicles is minimal in both cell types that were tested, indicating their utility as a safe material for use in ARV drug delivery (Figure 5). Interestingly, we found that while both TZM-bL cells and CEMx174 cells were robust and displayed high viability in response to exposure to blank nanolipogels (no drug) and free ARV-drugs, MVC drug-loaded nanolipogels did induce cellular cytotoxicity at high concentrations greater than 10 μM. At high concentrations of MVC (~50 μM), CEMx174 cells were especially sensitive to cell death. Since both blank nanolipogels and free MVC did not show cellular toxicity at the same particle and drug concentrations, our data suggests that there may be an interaction that triggers cellular toxicity at high concentrations when MVC is formulated within nanolipogels. Importantly, at the range of drug concentrations tested in our antiviral studies in TZM-bL cells, viral inhibition was not confounded by toxicity. Within this concentration range, ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels exhibit high cell viability that is not statically different from free ARV-drugs, as determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by a post-Bonferroni test. As such, antiviral activity and IC50 quantification in subsequent biological assays was due to drug-dependent inhibition, and not general cellular cytotoxicity.

The antiviral activity of MVC- and TDF-loaded nanolipogels demonstrate that both drugs retain their antiviral bioactivity and are successful at inhibition of HIV-1 infection. Both MVC and TDF retained IC50 values that were near that of unformulated free drugs, both in the case of cell-free HIV-1 infection and PM-1 cell-cell HIV-1 transmission. We found that cell-cell HIV-1 transmission was more efficient than cell-free HIV-1 infection of TZM-bL cells. This was evident by the increase in IC50 values for both MVC and TDF, indicating that in both cases, more drug was required to achieve the same level of viral inhibition. This was especially the case with MVC, where there was a near seven-fold loss of activity versus a two to three-fold loss of activity in TDF treatment groups. These differences may be attributed to the difference in mechanisms of action for both drugs. MVC is an entry inhibitor of HIV-1 and may experience an on- off-rate of binding CCR5 in cell culture, and thus would not be capable of constantly inhibiting viral entry. On the other hand TDF is a reverse transcriptase inhibitor with an intracellular site of action. Once internalized, TDF remains intracellular until it is metabolized to the active drug tenofovir, which has a long half-life of ~95-hours [26]. As such, the latter drug is present at more constant levels at its site of action. The differences between these drugs is more noticeable in cell-cell transmission, as this assay captures the effect of heightened and increasing production of HIV-1 virus over time by chronically infected PM-1 cells. Further, while it is impossible to state that no infection in the cell-cell transmission assay is due to cell-free virus, it is likely that the most probable route of infection during the one-hour incubation of TZM-bL cells with infected PM-1 cells is primarily through cell-associated transmission [40]. Cell-associated transmission of HIV-1 likely occurs through the formation of a cell-cell virological synapse that enables interactions between gp120 on budding virus from infected cells and a range of target cell receptors [41,42]. As such a CCR5 inhibitor such as MVC may display reduced inhibitory activity, since infection can rapidly propagate via a range of cell-surface receptor targets. Overall, our results demonstrate key biological characteristics of the ARV drug-loaded nanolipogel systems. First, the nanolipogel synthetic procedure does not alter the bioactivity of either drug post-formulation. Further, combination treatment of TZM-bL cells resulted in potent antiviral activity against cell-free and cell-cell transmission of virus.

Finally, we are interested in evaluating the application ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels as a topical, vaginal microbicide. We were unable to detect MVC or TDF in CVLs 24-hours post-administration by HPLC. However, we expect that this was due to the fact that any drug remaining in CVLs was below the level of detection using our HPLC methods. As reported by das Neves et al., who vaginally delivered dapivirine loaded polymer nanoparticles in a mouse model, only ~1% of administered drug was detected in CVLs 24-hours post-administration [9]. This low level of drug recovery in CVLs may be detectable with further optimization of HPLC methods for the detection of MVC and TDF in future works. However, we were surprised to find that CVLs from ARV drug-loaded nanolipogel treated mice did show antiviral activity against cell-free HIV-1 BaL infection in TZM-bL cells that was above background (Figure 7). Even at a dilution of 128-fold, CVLs still provided >60% viral inhibition, comparable to the activity of both ARV drugs delivered together in mice. This indicates that the delivered ARV drugs were still present at protective concentrations, 24-hours post-vaginal administration in mice. Previous studies have shown that EPC liposomes have low diffusivity in rat intestinal mucus [43]. We hypothesize that the observed antiviral activity is likely due to entrapment of a small fraction of the administered dose in freshly produced mucus in the mouse genital tract. While these in vivo studies have laid the ground work for the use of nanolipogels for topical microbicide applications, future studies must be focused on improving dosing and local retention through the use of a semi-solid or solid dosage platform and on evaluating the time-dependent antiviral activity in CVLs, with direct comparisons between free and formulated ARV drugs. Furthermore, improvements on vehicle design such as PEGylation to improve mucus penetration, may be incorporated into the nanolipogel system to improve their application for vaginal drug delivery [44,45].

5. Conclusions

Nanolipogels show promise for further in vitro and in vivo studies involving delivery of this important class of pharmaceutical compounds. Furthermore, investigation of lipid formulation and vehicle design may result in improving drug loading and encapsulation efficiencies. We have found that the nanolipogel systems are robust carrier for loading and modulated release of two classes of antiretroviral drugs. Our ARV drug-loaded nanolipogels show potent antiviral activity in vitro, and retain antiviral activity in CVLs after topical, vaginal delivery. These systems have the potential to expand the dosage forms available for water-soluble ARV drugs as topical microbicides. Applications to delivery of other small molecule hydrophilic drugs could benefit from these materials, which bridge efficient delivery and therapeutic efficacy. Future work will examine the ability to co-deliver hydrophobic and hydrophilic ARV drugs simultaneously in nanolipogels. We expect that nanolipogels will serve as a promising platform for combination ARV drug delivery for prevention and treatment of HIV.

Supplementary Material

RP-HPLC was used to obtain drug peak chromatograms taken before and after UV polymerization of a 0.1 mg/ml solution of maraviroc (absorbance 193 nm) and TDF (absorbance 197 nm). Drug solutions were UV polymerized for 15 min to replicate UV-exposure during NLG synthesis. Full chromatograms are displayed with a y-axis offset to visualize UV polymerized drugs (a). Quantification of area under the curve (AUC) of the drug peak revealed a >94% recovery after UV polymerization.

RP-HPLC was used to obtain drug peak chromatograms of a 0.05 mg/ml solution of drug, drugs formulated in nanolipogels and spiked with IPA, and blank nanolipogels spiked with IPA. Intensity, plotted in absorbance units (MVC, 193 nm; TDF, 197 nm), is shown as a function of retention time.

Maraviroc and TDF was formulated in nanolipogels at 10% (w/w) lipid mass with lipid/cholesterol ratios of 90/10, 75/25, and 50/50. Drug release from nanolipogels was measured using 1,000 MWCO dialysis tubes inverted into a 50-mL conical containing a sink volume of 5 mL DI water (MVC) and 10 mM NaCl, pH 4 (TDF). Released drug was quantified by reverse phase UV-HPLC.

Statement of Significance.

Topical, mucosal treatment of HIV is a leading strategy in the efforts to curb the spread of viral infection. A significant research thrust in the field has been to characterize different dosage forms for formulation of physicochemically diverse antiretroviral drugs. Nanocarriers have been used to formulate and deliver small molecule and protein drugs for a range of applications, including ARV drugs for HIV treatment. The broad significance of our work includes evaluation of lipid-shell, hydrogel-core nanoparticles for formulation and topical, vaginal delivery of two water-soluble antiretroviral drugs. We have characterized these nanocarriers for their physical properties and their biological activity against HIV-1 infection in vitro, and demonstrated the ability to deliver drug-loaded nanocarriers in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by funding from the NIH (AI094412, DP2HD075703) to K.A.W. and by the UW STD & AIDS Research Training Program (NIHT32AI07140) to R.R.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Singh R, Lillard JW. Nanoparticle-based targeted drug delivery. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2009;86:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slingerland M, Guchelaar H-J, Gelderblom H. Liposomal drug formulations in cancer therapy: 15 years along the road. Drug Discovery Today. 2012;17:160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ojewole E, Mackraj I, Naidoo P, Govender T. Exploring the use of novel drug delivery systems for antiretroviral drugs. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2008;70:697–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagné J-F, Désormeaux A, Perron S, Tremblay MJ, Bergeron MG. Targeted delivery of indinavir to HIV-1 primary reservoirs with immunoliposomes. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes. 2002;1558:198–210. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaowanachan T, Krogstad E, Ball C, Woodrow KA. Drug synergy of tenofovir and nanoparticle-based antiretrovirals for HIV prophylaxis. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mainardes RM, Gremião MPD, Brunetti IL, Da Fonseca LM, Khalil NM. Zidovudine-loaded PLA and PLA–PEG blend nanoparticles: Influence of polymer type on phagocytic uptake by polymorphonuclear cells. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009;98:257–67. doi: 10.1002/jps.21406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang T, Sturgis TF, Youan B-BC. pH-responsive nanoparticles releasing tenofovir intended for the prevention of HIV transmission. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2011;79:526–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karim QA, Karim SSA, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neves das J, Araújo F, Andrade F, Amiji M, Bahia MF, Sarmento B. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of dapivirine-loaded nanoparticles after vaginal delivery in mice. Pharmaceutical Research. 2014;31:1834–45. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Immordino ML, Dosio F, Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2006;1:297. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips NC, Skamene E, Tsoukas C. Liposomal encapsulation of 3“-azido-3-”deoxythymidine (AZT) results in decreased bone marrow toxicity and enhanced activity against murine AIDS-induced immunosuppression. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1991;4:959–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X, Khan MA, Burgess DJ. A quality by design (QbD) case study on liposomes containing hydrophilic API: I. Formulation, processing design and risk assessment. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2011;419:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillaireau H, Le Doan T, Besnard M, Chacun H, Janin J, Couvreur P. Encapsulation of antiviral nucleotide analogues azidothymidine-triphosphate and cidofovir in poly (iso-butylcyanoacrylate) nanocapsules. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2006;324:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandal TK, Lopez-Anaya A, Onyebueke E, Shekleton M. Preparation of biodegradable microcapsules containing zidovudine (AZT) using solvent evaporation technique. Journal of Microencapsulation. 1996;13:257–67. doi: 10.3109/02652049609026014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng J, Sturgis TF, Youan B-BC. Engineering tenofovir loaded chitosan nanoparticles to maximize microbicide mucoadhesion. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;44:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazakov S, Kaholek M, Teraoka I, Levon K. UV-induced gelation on nanometer scale using liposome reactor. Macromolecules. 2002;35:1911–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton JN, Palmer AF. Photopolymerization of bovine hemoglobin entrapped nanoscale hydrogel particles within liposomal reactors for use as an artificial blood substitute. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:414–24. doi: 10.1021/bm049432i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton JN, Palmer AF. Engineering temperature-sensitive hydrogel nanoparticles entrapping hemoglobin as a novel type of oxygen carrier. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2204–12. doi: 10.1021/bm050144b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park J, Wrzesinski SH, Stern E, Look M, Criscione J, Ragheb R, et al. Combination delivery of TGF-β inhibitor and IL-2 by nanoscale liposomal polymeric gels enhances tumour immunotherapy. Nature Materials. 2012;11:895–905. doi: 10.1038/nmat3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiser PF, Wilson G, Needham D. A synthetic mimic of the secretory granule for drug delivery. Nature. 1998;394:459–62. doi: 10.1038/28822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy EA, Majeti BK, Mukthavaram R, Acevedo LM, Barnes LA, Cheresh DA. Targeted nanogels: a versatile platform for drug delivery to tumors. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2011;10:972–82. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umamaheshwari RB, Jain NK. Receptor-mediated targeting of lipobeads bearing acetohydroxamic acid for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;99:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin T, Pennefather P, Lee PI. Lipobeads: a hydrogen anchored lipid vesicle system. FEBS Letters. 1996;397:70–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Tu S, Pinchuk AN, Xiong MP. Active drug encapsulation and release kinetics from hydrogel-in-liposome nanoparticles. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2013;406:247–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.05.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacArthur RD, Novak RM. Maraviroc: the first of a new class of antiretroviral agents. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;47:236–41. doi: 10.1086/589289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaney WE, Ray AS, Yang H, Qi X, Xiong S, Zhu Y, et al. Intracellular metabolism and in vitro activity of tenofovir against hepatitis B virus. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2006;50:2471–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00138-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen BA, Panther L, Marzinke MA, Hendrix CW, Hoesley CJ, van der Straten A, et al. Phase 1 Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of Dapivirine and Maraviroc Vaginal Rings: a Double-Blind Randomized Trial. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sepúlveda-Crespo D, Sánchez-Rodríguez J, Serramía MJ, Gómez R, La Mata De FJ, Jiménez JL, et al. Triple combination of carbosilane dendrimers, tenofovir and maraviroc as potential microbicide to prevent HIV-1 sexual transmission. Nanomedicine. 2015;10:899–914. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malcolm RK, Forbes CJ, Geer L, Veazey RS, Goldman L, Klasse PJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of a vaginally administered maraviroc gel in rhesus macaques. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2013;68:678–83. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:509–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith JM, Rastogi R, Teller RS, Srinivasan P, Mesquita PM, Nagaraja U, et al. Intravaginal ring eluting tenofovir disoproxil fumarate completely protects macaques from multiple vaginal simian-HIV challenges. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:16145–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311355110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mesquita PM, Rastogi R, Segarra TJ, Teller RS, Torres NM, Huber AM, et al. Intravaginal ring delivery of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of HIV and herpes simplex virus infection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67:1730–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nixon B, Jandl T, Teller RS, Taneva E, Wang Y, Nagaraja U, et al. Vaginally delivered tenofovir disoproxil fumarate provides greater protection than tenofovir against genital herpes in a murine model of efficacy and safety. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014;58:1153–60. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01818-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schillemans JP, Flesch FM, Hennink WE, van Nostrum CF. Synthesis of bilayer-coated nanogels by selective cross-linking of monomers inside liposomes. Macromolecules. 2006;39:5885–90. [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Avolio A, Simiele M, Baietto L, Siccardi M, Sciandra M, Patanella S, et al. A validated high-performance liquid chromatography-ultraviolet method for quantification of the CCR5 inhibitor maraviroc in plasma of HIV-infected patients. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 2010;32:86–92. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181cacbd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talmon Y. The Study of Latex IPNs by Cryo-TEM Using Radiation-Damage Effects. Technomic Publishing Company, Advances in Interpenetrating Polymer Networks. 1990;2:141–56. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Thienen TG, Lucas B, Flesch FM, Van Nostrum CF, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. On the synthesis and characterization of biodegradable dextran nanogels with tunable degradation properties. Macromolecules. 2005;38:8503–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dembri A, Montisci M-J, Gantier JC, Chacun H, Ponchel G. Targeting of 3′-azido 3′-deoxythymidine (AZT)-loaded poly (isohexylcyanoacrylate) nanospheres to the gastrointestinal mucosa and associated lymphoid tissues. Pharmaceutical Research. 2001;18:467–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1011050209986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christoper GP, Raghavan CV, Siddharth K, Kumar MSS, Prasad RH. Formulation and optimization of coated PLGA–Zidovudine nanoparticles using factorial design and in vitro in vivo evaluations to determine brain targeting efficiency. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2014;22:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buffa V, Stieh D, Mamhood N, Hu Q, Fletcher P, Shattock RJ. Cyanovirin-N potently inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in cellular and cervical explant models. Journal of General Virology. 2009;90:234–43. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.004358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sattentau Q. Avoiding the void: cell-to-cell spread of human viruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:815–26. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:2855–64. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2855-2864.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Chen D, Le C, Zhu C, Gan Y, Hovgaard L, et al. Novel mucus-penetrating liposomes as a potential oral drug delivery system: preparation, in vitro characterization, and enhanced cellular uptake. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2011;6:3151. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S25741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ensign LM, Tang BC, Wang Y-Y, Terence AT, Hoen T, Cone R, et al. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for vaginal drug delivery protect against herpes simplex virus. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:138ra79–9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cu Y, Saltzman WM. Controlled surface modification with poly (ethylene) glycol enhances diffusion of PLGA nanoparticles in human cervical mucus. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2008;6:173–81. doi: 10.1021/mp8001254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

RP-HPLC was used to obtain drug peak chromatograms taken before and after UV polymerization of a 0.1 mg/ml solution of maraviroc (absorbance 193 nm) and TDF (absorbance 197 nm). Drug solutions were UV polymerized for 15 min to replicate UV-exposure during NLG synthesis. Full chromatograms are displayed with a y-axis offset to visualize UV polymerized drugs (a). Quantification of area under the curve (AUC) of the drug peak revealed a >94% recovery after UV polymerization.

RP-HPLC was used to obtain drug peak chromatograms of a 0.05 mg/ml solution of drug, drugs formulated in nanolipogels and spiked with IPA, and blank nanolipogels spiked with IPA. Intensity, plotted in absorbance units (MVC, 193 nm; TDF, 197 nm), is shown as a function of retention time.

Maraviroc and TDF was formulated in nanolipogels at 10% (w/w) lipid mass with lipid/cholesterol ratios of 90/10, 75/25, and 50/50. Drug release from nanolipogels was measured using 1,000 MWCO dialysis tubes inverted into a 50-mL conical containing a sink volume of 5 mL DI water (MVC) and 10 mM NaCl, pH 4 (TDF). Released drug was quantified by reverse phase UV-HPLC.