Abstract

Numerous health consequences of tobacco smoke exposure have been characterized, and smoking’s effects on traditional measures of male fertility are well described. However, a growing body of data indicates that pre-conception paternal smoking also confers increased risk for a number of morbidities on offspring. The mechanism for this increased risk has not been elucidated, but it is likely mediated, at least in part, through epigenetic modifications transmitted through sperm. In this study, we investigated the impact of cigarette smoke exposure on sperm DNA methylation patterns in 78 men who smoke and 78 never-smokers using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 beadchip. We investigated two models of DNA methylation alterations: (1) consistently altered methylation at specific CpGs or within specific genomic regions and (2) stochastic DNA methylation alterations manifest as increased variability in genome-wide methylation patterns in men who smoke. We identified 141 significantly differentially methylated CpGs associated with smoking. In addition, we identified a trend toward increased variance in methylation patterns genome-wide in sperm DNA from men who smoke compared with never-smokers. These findings of widespread DNA methylation alterations are consistent with the broad range of offspring heath disparities associated with pre-conception paternal smoke exposure and warrant further investigation to identify the specific mechanism by which sperm DNA methylation perturbation confers risk to offspring health and whether these changes can be transmitted to offspring and transgenerationally.

Keywords: sperm DNA methylation, smoking, genome-wide, epigenetics, transgenerational inheritance

INTRODUCTION

In a recent study it was estimated that more than one third of the world’s population is regularly exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) (Oberg et al., 2011). Further, in 2004 and estimated 603,000 premature deaths and a loss of 10.9 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) occurred due to involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke (Oberg et al., 2011), and an estimated six million annual deaths are attributable to tobacco smoke exposure. Tobacco smoke contains more than 4000 chemicals including a myriad of known carcinogens. The health consequences of smoke exposure are significant and include numerous diseases and dysfunctions of the respiratory tract, increased risk of multiple types of cancer and increased incidence of cardiovascular disease (DiFranza et al., 2004; Moritsugu, 2007). Clearly tobacco smoke exposure is a global problem, the implications of which are becoming increasingly apparent.

The negative impacts of tobacco smoke on semen parameters are well established. Smoking is associated with an accumulation of cadmium and lead in seminal plasma, reduced sperm count and motility, and fewer morphologically normal sperm (Kiziler et al., 2007; Kulikauskas et al., 1985). In addition, increased sperm chromatin structural abnormalities and sperm DNA damage, and reduced reproductive potential have been reported in tobacco smoke-exposed mice (Polyzos et al., 2009) and humans (Fuentes et al., 2010). Adult male mice exposed to sidestream tobacco smoke display significant increases in sperm DNA mutations at expanded simple tandem repeats (ESTRs) (Marchetti et al., 2011) and aberrations in sperm chromatin structure (Polyzos et al., 2009). In contrast, these male mice exhibit no measurable increase in somatic cell chromosome damage, indicating that germ cells may be more prone to genetic and/or epigenetic insults resulting from smoke exposure than somatic cells. Destabilization of ESTRs in the adult male germline is well documented to be associated with transgenerational effects in the mouse genome (R. Barber et al., 2002; R. C. Barber et al., 2006; Dubrova, 2003; Dubrova et al., 2008; Glen et al., 2012). Thus, these data suggest that smoke exposure might induce lasting genetic and epigenetic changes that could impact subsequent unexposed generations.

The International Association for Research on Cancer (IARC) has recently declared that paternal smoking prior to pregnancy is associated with a significantly elevated risk of leukemia in the offspring (Ji et al., 1997; Secretan et al., 2009) (Chang et al., 2006; K. M. Lee et al., 2009; Pang et al., 2003; Vine, 1996) suggesting smoke-induced genetic or epigenetic changes occur in sperm that are transmitted to offspring. Additionally, children of men who smoke are at increased risk for childhood cancers, asthma (Svanes et al., 2016) and birth defects including cleft palate, urethral stenosis, hydrocephalus (Savitz et al., 1991), congenital heart disease, cardiovascular anomalies (Cresci et al., 2011) anorectal malformations (Zwink et al., 2011), spina bifida (Zhang et al., 1992), and reduced kidney volume (Kooijman et al., 2015).

Smoking has clearly been shown to modify DNA methylation patterns and gene expression in somatic tissues in individuals exposed to first- or second-hand tobacco smoke (Bosse et al., 2012a; Kohli et al., 2012; Word et al., 2012) as well as in newborns of smoking mothers (Breton et al., 2009; Joubert et al., 2012; Perera et al., 2011). A growing body of evidence suggests that exposure could have negative health consequences not only for the exposed individual, but also for the descendants of those who are exposed. A complete understanding of the transgenerational effects of tobacco smoke exposure is of critical relevance to public health.

Given the huge proportion of the population that is exposed to tobacco smoke, either directly or indirectly, complete characterization of the health consequences of this exposure, not only on the exposed individuals, but also potentially on unexposed offspring and progeny is critical in informing health policy moving forward. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the effect of pre-conception tobacco smoke exposure on sperm DNA methylation as a potential mechanism for transmission of health risks to offspring.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Semen samples were collected from patients being evaluated for couple infertility as well as from men from the general population recruited for research studies through community outreach. All participants gave informed consent for participation in this University of Utah Institutional Review Board-approved study. Semen samples were collected based on WHO criteria after a recommended 2–7 days of sexual abstinence. Individuals with a sperm concentration of less than 2 × 106/ml were excluded from the study due to insufficient sperm DNA to perform the assay. To be included in the non-smoking group, and individual was required to have never smoked cigarettes. Minimum cigarette consumption for the smoking group was one pack year (defined as the number of cigarettes per day × # of years smoking/20). There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria for the current study. Smoking status was assessed based on a questionnaire filled out by patients at the time of informed consent. Specifically, individuals were asked if they smoked cigarettes, and if so, how many daily and how long they had smoked. The smoking group and control group each consisted of 21 men from the general population and 57 men who presented to the Andrology Laboratory for evaluation for couple infertility. Semen analyses were performed according to WHO IV criteria. Following the diagnostic test, the remaining sample was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with test yolk buffer (TYB; Irvine Scientific, Irvine, CA) and frozen in 1 ml cryovials in liquid nitrogen vapors. Frozen vials were submerged and stored in liquid nitrogen until thawing for methylation analysis.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for semen parameters and patient age. Normally distributed variables (age, semen volume, % progressive motility, % normal head morphology, % normal tail morphology, and % viable) were compared between groups using Student’s t-test, while non-parametric variables (sperm concentration, total sperm count, total progressively motile sperm count, somatic cell concentration, and comet score) were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Alkaline Comet assay

Sperm DNA damage was assessed using an alkaline single-cell gel electrophoresis (Comet) assay as modified previously (Donnelly et al., 1999; Hughes et al., 1997). Spermatozoa were considered damaged or normal based on the presence or absence of a visible Comet tail, respectively. A total of 50 to 100 Comets were scored per sample.

Methylation analysis

DNA Isolation

All frozen samples were thawed and processed simultaneously to avoid batch effects. Once thawed, sperm were subjected to a stringent somatic cell lysis protocol to ensure the absence of potential contamination resulting from the presence of leukocytes or other somatic cells. Briefly, samples were run through a 40um cell strainer to remove any large debris or cell clumps. The strained sample was washed in 14 ml of PBS followed by two washes in 14 ml of distilled water. The samples were then centrifuged, and the resulting pellet was resuspended and incubated for a minimum of 60 minutes a 4° C in 14 ml of a somatic cell lysis buffer (0.1% SDS, 0.5% Triton X-100 in DEPC H2O). Following this lysis step, a visual check was performed under 400× magnification to confirm the absence of somatic cells, then sperm DNA was isolated using a sperm specific modification commonly used in our lab to a column-based extraction protocol using the DNeasy DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA)(Jenkins et al., 2013; Jenkins et al., 2014a). In addition to the visual check, a post hoc analysis of methylation data at the DLK1 locus, a region that is unmethylated in sperm and fully methylated in leukocytes, was evaluated to further confirm a pure sperm population as detailed previously (Jenkins et al., 2016).

Bisulfite Conversion, Array Processing, and Quality Control

Extracted sperm DNA was bisulfite converted with EZ-96 DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research, Irvine CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations specifically for use with array platforms. Converted DNA was then delivered to the University of Utah Genomics Core Facility hybridized to Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip microarrays (Illumina) and analyzed according to Illumina protocols. Array data for all samples were evaluated for standard data quality indicators, and two samples (both general population samples, one smoker and one non-smoker) were excluded from the study due to failure to meet established standards.

Methylation Data Processing

The Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline (ChAMP) was used to process array data and generate β-values (fraction methylation values between 0 and 1). This process additionally includes the filtering of poorly performing probes from downstream analysis (probes with a QC p<0.05 were excluded) and SWAN normalization. Normalized β-values were then logit transformed to generate m-values for all further downstream analyses.

Global Methylation Analysis

Global methylation analysis was conducted by averaging β-values across all probes on the array for smoking and control groups. β-values were also averaged across both groups considering CpG island context and gene association.

Differential Methylation Analysis

The Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline (ChAMP) was used to identify differentially methylated CpGs between smokers and controls. ChAMP is a bioconductor package specifically designed for the analysis of Illumina HumanMethylation arrays that includes functionality for quality control, data normalization, and statistical tests for differential methylation (Morris et al., 2014). Benjamini Hochberg corrected p-values of <0.05 were considered significant. We additionally performed regional differential methylation analysis to identify contiguous differentially methylated CpGs, which are more likely to be biologically relevant. We performed regional analyses in two ways. First, differentially methylated regions were assessed in ChAMP via bump hunter. Second, we utilized the USeq platform to perform a 1000 base pair sliding window analysis commonly used in our lab (Jenkins et al., 2014b). A Benjamini Hochberg corrected Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test FDR of ≤ 0.0001 (≥ transformed FDR of 40) and an absolute log2 ratio ≥ 0.2 were used for our threshold of significance. Any significant findings were subjected to GO Term and Pathway analysis utilizing Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT) (McLean et al., 2010).

Methylation Variability Analysis

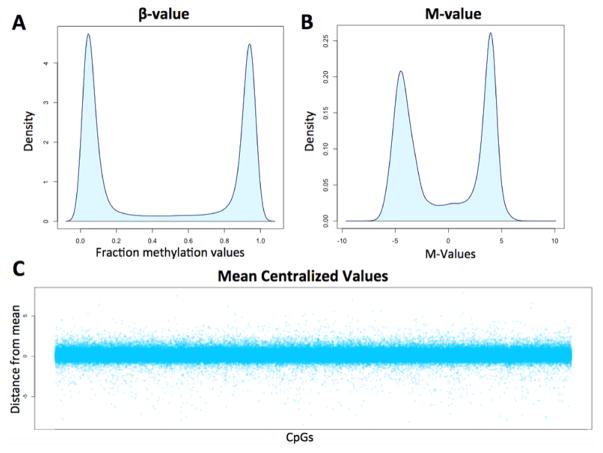

Analysis of variability was performed using the R software package. The overarching goal of this approach was to identify intra-group (smokers and non-smokers) variability for every CpG assessed on the array and to compare these findings between smokers and non-smokers. First, raw, Swan-normalized, β-values were subjected to logit transformation to generate m-values (Fig. 1A) to ensure the absence of heteroscedasticity in our analysis (the utility of logit transformation can be visualized in Fig. 1B). M-values for all samples analyzed in our study undergo “CpG-wise” mean centralization in R resulting in center-scaled (CS) values descriptive of the distance from average for each CpG in every individual. Figure 1C demonstrates the nature of CS values for a representative individual following mean centralization. CS values were then utilized to describe differences in variation between smokers and controls with increased distance from the mean equating to increased variability. With these data we compared average variability across all probes and also assessed regions of the genome that appear to be more variable in smokers compared to controls.

Figure 1. Data transformation steps used for the variability analysis.

A) Density plot displaying the distribution of beta values from a representative individual. B) The values from the same individual following logit transformation of beta values to generate m-values. C) Center scaled (CS) values from a single individual for all ~485k CpGs tiled on the array. CS values represent both the direction and distance from average for each CpG.

RESULTS

Semen parameters and DNA Damage

We observed a modest, but significant, decrease in several semen parameters including semen volume, total sperm count, and total progressively motile sperm count in men who smoke compared with never smokers. In addition, we observed a marginally significant increase in sperm DNA damage (p = 0.05) in men who smoke (Table 1). Box and whisker plots were generated to display the distribution of the various parameters for smokers and nonsmokers (Supplemental Fig 1). While semen parameters were similar in men from the general population and infertility patients, the effects of smoking on semen parameters and DNA damage were generally more significant in men from the general population than in patients. Interestingly, the level of DNA damage did not seem to be influenced by increased smoking duration or amount.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of semen parameters and other metrics in smokers and non-smokers.

| Mean ± SEM in smokers (n = 78) | Mean ± SEM in non-smokers (n = 78) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years smoking | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | NA |

| # Cigarettes/day | 13.3 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | NA |

| Pack years | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 0.0 | NA |

| Age (years) | 32.4 ± 0.9 | 31.2 ± 0.6 | 0.29 |

| Semen volume (ml) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 0.0003 |

| Sperm concentration (M/ml) | 81.0 ± 9.4 | 76.7 ± 6.2 | 0.82 |

| Total sperm (M) | 245.6 ± 30.8 | 316.0 ± 26.4 | 0.03 |

| % Progressively motile | 48.4 ± 2.6 | 51.8 ± 2.3 | 0.33 |

| Total motile count (M) | 136.5 ± 19.6 | 177.8 ± 17.3 | 0.04 |

| % Normal heads | 29.2 ± 1.5 | 25.6 ± 1.3 | 0.07 |

| % Normal tails | 71.4 ± 1.5 | 72.8 ± 1.2 | 0.48 |

| % Viable | 56.7 ± 2.1 | 57.9 ± 1.7 | 0.67 |

| Concentration amorphous cells (M/ml) | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.13 |

| Comet positive cells (%) | 54.0 ± 3.4 | 44.1 ± 2.4 | 0.05 |

Sperm DNA methylation

Three primary analyses were performed to assess the effect of smoking on sperm DNA methylation: 1) Global methylation differences, 2) locus- or region-specific methylation differences, and 3) differences in methylation variance genome-wide.

We first calculated average beta values across all CpGs in samples from smokers compared to non-smokers, and additionally evaluated average values across different genomic features. We did not identify any differences in methylation globally or at specific genomic features (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of average beta values across all control versus smoker samples based on genomic context.

No differences in average methylation were observed in smokers versus non-smokers across the whole genome or at CpG islands, gene bodies, or non-CpG loci interrogated by the array.

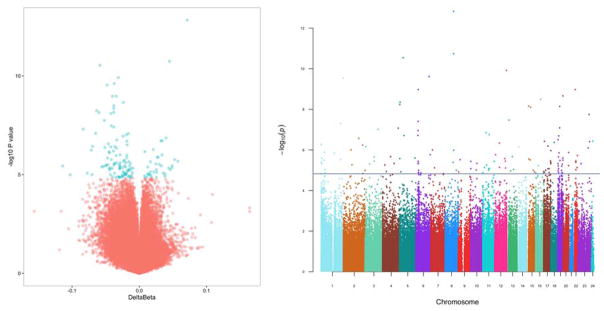

We next evaluated methylation alterations at specific loci or in specific regions. Site-specific DNA methylation analysis revealed 141 significantly differentially methylated loci associated with smoking following Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons (Table 2, Fig 3). Interestingly, of the 141 significantly altered CpGs, 104 (74%) were hypomethylated, and only 37 (26%) were hypermethylated in samples from men who smoke (p < 0.0001). We previously reported a similar trend in preference toward loss of methylation at significantly altered CpGs in sperm DNA associated with male age (Jenkins et al., 2014b). While the directionality of DNA methylation changes were similar in both studies, we did not identify any DMRs that were shared by both studies. In addition, we found that differentially methylated CpGs were significantly under-represented at CpG islands and significantly over-represented at shore regions (p < 0.0001; Fig 4a), potentially indicating that CpG islands are somewhat protected from environmentally-induced methylation changes. We also found that regions previously reported to escape protamine replacement during spermatogenesis and enriched for H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 (Hammoud et al., 2009) were significantly over-represented in the dataset of differentially methylated CpGs (Fig 4b), indicating that histone-bound regions of the sperm genome may be more prone to environmentally-induced methylation changes. The CpGs located within these histone-bound regions are indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

| Nearest Gene | Probe ID | Chromosome | Map info | Strand | Gene | Feature | CGI | H3K4me3 or H3K27me3- bound region |

Residual methylation |

Non-smoker DNA methylation (%) |

Smoker DNA methylation (%) |

Delta DNA methylation (%) |

Raw p- value |

Benjamini- Hochberg adjusted p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAM92A1 | cg08953048 | 8 | 94658042 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 58.3% | 65.5% | 7.1% | 1.5E-13 | 6.7E-08 | ||

| FAM92A1 | cg01040499 | 8 | 94657423 | F | IGR | opensea | 11.1% | 15.5% | 4.5% | 1.8E-11 | 4.0E-06 | |||

| OSMR | cg15599832 | 5 | 38845129 | R | OSMR | TSS1500 | shore | x | x | 20.6% | 14.7% | −5.9% | 2.9E-11 | 4.3E-06 |

| RP11-474D1.3 | cg26959380 | 12 | 130498820 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 42.9% | 39.8% | −3.1% | 1.2E-10 | 1.4E-05 | ||

| ULBP2 | cg06471296 | 6 | 150259601 | F | IGR | island | x | 11.7% | 8.0% | −3.7% | 2.4E-10 | 2.2E-05 | ||

| RP11-278H7.1 | ch.1.242086458R | 1 | 244019835 | F | IGR | opensea | 55.0% | 50.2% | −4.8% | 2.9E-10 | 2.2E-05 | |||

| PRSS16 | cg01759136 | 6 | 27242945 | F | IGR | opensea | 68.5% | 64.6% | −4.0% | 1.1E-09 | 5.9E-05 | |||

| BCR | cg10480239 | 22 | 23522307 | R | BCR | TSS1500 | shore | x | 37.2% | 33.8% | −3.4% | 1.1E-09 | 5.9E-05 | |

| ZNF784 | cg22169206 | 19 | 56136215 | F | ZNF784 | TSS1500 | shore | 44.6% | 42.2% | −2.4% | 2.2E-09 | 1.1E-04 | ||

| MT1F | cg02527372 | 16 | 56692077 | F | MT1F | Body | shore | x | 18.2% | 14.4% | −3.8% | 3.2E-09 | 1.4E-04 | |

| LINC01020 | cg20662737 | 5 | 4941328 | R | IGR | opensea | x | 60.7% | 56.9% | −3.8% | 4.4E-09 | 1.8E-04 | ||

| NDUFS6 | cg07875360 | 5 | 1801344 | F | NDUFS6 | TSS200 | island | 58.5% | 52.2% | −6.4% | 5.8E-09 | 2.1E-04 | ||

| ZNF253 | cg09414724 | 19 | 19976638 | F | ZNF253 | TSS200 | opensea | x | 30.9% | 24.9% | −6.0% | 7.2E-09 | 2.3E-04 | |

| NDN | cg18406232 | 15 | 23927915 | F | IGR | shelf | 55.9% | 52.1% | −3.8% | 7.0E-09 | 2.3E-04 | |||

| SHF | cg17911021 | 15 | 45493416 | F | SHF | TSS200 | shelf | x | 53.8% | 49.6% | −4.2% | 7.9E-09 | 2.4E-04 | |

| ZNF280C | cg17758324 | X | 129403027 | R | ZNF280C | TSS200 | island | 66.5% | 61.3% | −5.2% | 1.8E-08 | 5.0E-04 | ||

| RNF17 | cg24609094 | 13 | 25319768 | F | IGR | island | x | 40.6% | 36.4% | −4.2% | 3.4E-08 | 8.9E-04 | ||

| GUSBP2 | cg22243996 | 6 | 26757644 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 14.0% | 10.2% | −3.8% | 3.9E-08 | 9.7E-04 | ||

| FAM19A5 | cg04377908 | 1 | 220250989 | R | BPNT1 | Body | opensea | 75.0% | 66.7% | −8.3% | 4.9E-08 | 1.2E-03 | ||

| KIAA1712 | cg20535044 | 4 | 175204418 | R | KIAA1712 | TSS1500 | shore | x | 7.2% | 5.5% | −1.6% | 8.4E-08 | 1.8E-03 | |

| ZNF253 | cg26933068 | 19 | 19976613 | R | ZNF253 | TSS200 | opensea | x | 29.2% | 22.7% | −6.5% | 8.2E-08 | 1.8E-03 | |

| ZIC1 | cg01458605 | 3 | 147128679 | F | ZIC1 | 1stExon | island | 8.1% | 6.2% | −1.9% | 9.6E-08 | 1.9E-03 | ||

| GUSBP2 | cg16387141 | 6 | 26757842 | R | IGR | opensea | x | 19.8% | 17.4% | −2.4% | 1.1E-07 | 2.2E-03 | ||

| MIR3973 | cg09817641 | 11 | 35845023 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 41.4% | 45.3% | 4.0% | 1.4E-07 | 2.6E-03 | ||

| KRTAP5-11 | cg10924669 | 11 | 71320766 | R | IGR | shore | 46.8% | 43.5% | −3.4% | 1.8E-07 | 3.1E-03 | |||

| PARP8 | cg07757885 | 5 | 50219072 | R | IGR | opensea | x | 35.6% | 38.8% | 3.2% | 2.0E-07 | 3.2E-03 | ||

| DCDC2 | cg16427109 | 6 | 24358683 | F | DCDC2 | TSS1500 | shore | 9.0% | 12.4% | 3.4% | 1.9E-07 | 3.2E-03 | ||

| ICAM3 | cg06855803 | 19 | 10450364 | F | ICAM3 | TSS200 | opensea | 86.4% | 84.5% | −1.9% | 2.0E-07 | 3.2E-03 | ||

| SLC25A12 | ch.2.3493243F | 2 | 172737063 | F | SLC25A12 | Body | opensea | 30.7% | 26.1% | −4.6% | 2.7E-07 | 4.2E-03 | ||

| TMPRSS9 | cg25966599 | 19 | 2422172 | R | TMPRSS9 | Body | shore | 85.0% | 83.2% | −1.8% | 3.1E-07 | 4.6E-03 | ||

| FAM127C | cg12592455 | X | 134166801 | R | FAM127A | 1stExon | island | 13.9% | 9.7% | −4.2% | 3.9E-07 | 5.2E-03 | ||

| TMSB4Y | cg17560699 | Y | 15593045 | F | UTY | TSS1500 | shore | 56.2% | 49.2% | −7.0% | 3.7E-07 | 5.2E-03 | ||

| GUCY2D | cg25581932 | 17 | 7892150 | R | IGR | shore | 18.2% | 14.6% | −3.6% | 3.8E-07 | 5.2E-03 | |||

| MIR5583-2 | cg15612221 | 18 | 37379468 | R | IGR | opensea | x | 31.2% | 26.0% | −5.1% | 4.3E-07 | 5.6E-03 | ||

| KRT86 | cg16911220 | 12 | 52695728 | R | KRT86 | 1stExon | island | 16.7% | 13.3% | −3.4% | 4.5E-07 | 5.8E-03 | ||

| ISG15 | cg23691733 | 1 | 944093 | R | IGR | opensea | 86.2% | 88.3% | 2.1% | 5.4E-07 | 6.7E-03 | |||

| LINC00607 | cg09166091 | 2 | 216484055 | R | IGR | opensea | 19.8% | 12.6% | −7.1% | 5.8E-07 | 7.0E-03 | |||

| PDK2 | cg20133730 | 17 | 48172203 | R | PDK2 | TSS1500 | shore | 65.7% | 61.8% | −3.8% | 6.4E-07 | 7.5E-03 | ||

| LMCD1 | cg08935301 | 3 | 8543732 | R | LMCD1 | Body | shore | 4.4% | 5.2% | 0.8% | 6.9E-07 | 7.8E-03 | ||

| ANG | cg16154578 | 14 | 21161297 | F | ANG | 5′UTR | opensea | x | 27.8% | 23.3% | −4.5% | 7.0E-07 | 7.8E-03 | |

| NKAP | cg09092713 | X | 119133965 | R | IGR | island | 16.2% | 11.7% | −4.5% | 8.0E-07 | 8.6E-03 | |||

| JAK2 | cg03071195 | 7 | 16459464 | F | ISPD | Body | shore | x | 69.2% | 72.6% | 3.4% | 1.0E-06 | 1.0E-02 | |

| PLEKHG5 | cg04818845 | 2 | 86331859 | F | POLR1A | Body | shore | x | 29.9% | 27.0% | −2.8% | 9.9E-07 | 1.0E-02 | |

| NEURL4 | cg02831821 | 8 | 96040122 | R | C8orf38 | Body | shelf | 89.5% | 87.6% | −1.8% | 1.0E-06 | 1.1E-02 | ||

| SECTM1 | cg26214645 | 17 | 80292081 | R | SECTM1 | TSS200 | island | 34.0% | 30.5% | −3.4% | 1.1E-06 | 1.1E-02 | ||

| THRAP3 | cg10212685 | 1 | 36748231 | R | THRAP3 | Body | opensea | 46.8% | 49.7% | 2.8% | 1.3E-06 | 1.3E-02 | ||

| MIR124-3 | cg01747792 | 20 | 61806628 | R | IGR | island | 10.2% | 12.9% | 2.6% | 1.3E-06 | 1.3E-02 | |||

| BEST2 | cg23867562 | 19 | 12861921 | F | BEST2 | TSS1500 | shelf | 79.6% | 77.7% | −1.9% | 1.4E-06 | 1.3E-02 | ||

| MIR5087 | cg11659025 | 1 | 147767989 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 27.8% | 23.0% | −4.7% | 1.4E-06 | 1.3E-02 | ||

| LOC360030 | cg01786216 | 12 | 7917888 | R | LOC360030 | 1stExon | opensea | 25.3% | 21.2% | −4.2% | 1.7E-06 | 1.5E-02 | ||

| PARK2 | cg22291694 | 6 | 162294486 | F | PARK2 | Body | opensea | x | 26.2% | 31.4% | 5.2% | 1.7E-06 | 1.5E-02 | |

| TSC22D1-AS1 | cg04671914 | 22 | 48977382 | F | FAM19A5 | Body | island | 83.0% | 80.8% | −2.2% | 1.9E-06 | 1.6E-02 | ||

| HERC6 | cg14212360 | 4 | 89302999 | F | HERC6 | Body | shelf | 86.9% | 84.6% | −2.3% | 2.1E-06 | 1.8E-02 | ||

| PCDH20 | cg26480584 | 13 | 62002615 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 41.3% | 47.1% | 5.7% | 2.1E-06 | 1.8E-02 | ||

| ISPD | cg03037561 | 19 | 6711092 | F | C3 | Body | shore | 84.6% | 83.1% | −1.6% | 2.2E-06 | 1.8E-02 | ||

| CEP97 | cg23962380 | 3 | 101443264 | R | CEP97 | TSS1500 | shore | x | 5.8% | 7.5% | 1.6% | 2.2E-06 | 1.8E-02 | |

| SIRT4 | cg05178654 | 1 | 6580167 | R | PLEKHG5 | TSS200 | opensea | 78.8% | 75.5% | −3.3% | 2.5E-06 | 1.9E-02 | ||

| ATP6V0E1 | cg07419740 | 5 | 172410441 | F | ATP6V0E1 | TSS1500 | shore | x | 9.5% | 7.5% | −2.0% | 2.5E-06 | 1.9E-02 | |

| SHISA7 | cg13752254 | 19 | 55940813 | F | SHISA7 | 3′UTR | shelf | 79.3% | 76.4% | −2.8% | 2.5E-06 | 1.9E-02 | ||

| KCNIP3 | cg03891849 | 12 | 112847769 | F | RPL6 | TSS1500 | shore | 50.1% | 46.5% | −3.6% | 2.7E-06 | 2.0E-02 | ||

| SLC6A19 | cg05972316 | 5 | 1204924 | R | SLC6A19 | Body | shelf | 87.6% | 86.3% | −1.3% | 2.7E-06 | 2.0E-02 | ||

| SNORD109B | cg23225193 | 15 | 25285663 | F | SNORD109B | TSS1500 | opensea | 80.8% | 77.0% | −3.7% | 2.8E-06 | 2.0E-02 | ||

| EPRS | cg21573359 | 1 | 220132728 | R | IGR | opensea | x | 11.0% | 13.5% | 2.5% | 2.9E-06 | 2.1E-02 | ||

| RPL6 | cg03788567 | 9 | 21696666 | F | IGR | island | x | 52.6% | 55.5% | 3.0% | 3.0E-06 | 2.1E-02 | ||

| RHOV | cg09166898 | 15 | 41167165 | R | RHOV | TSS1500 | shore | x | 51.2% | 46.5% | −4.6% | 3.1E-06 | 2.1E-02 | |

| ZNF784 | cg11306428 | 19 | 56136210 | F | ZNF784 | TSS1500 | shore | 35.9% | 32.9% | −3.0% | 3.2E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| SNHG3-RCC1 | cg23682641 | 1 | 28857538 | R | SNHG3-RCC1 | Body | shore | 25.5% | 21.8% | −3.8% | 3.3E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| ZNF675 | cg24101933 | 19 | 23870686 | F | ZNF675 | TSS1500 | opensea | 66.0% | 61.1% | −5.0% | 3.3E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| MRGPRX4 | cg04272710 | 12 | 118499294 | R | WSB2 | TSS1500 | island | x | 23.5% | 28.4% | 4.9% | 3.6E-06 | 2.2E-02 | |

| CANT1 | cg08088171 | 17 | 77003113 | R | CANT1 | 5′UTR | shelf | 87.3% | 85.8% | −1.4% | 3.5E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| CHEK1 | cg15190354 | 11 | 125494874 | F | CHEK1 | TSS1500 | shore | 14.8% | 11.9% | −2.9% | 3.7E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| GUSBP2 | cg16675381 | 6 | 26757706 | R | IGR | opensea | x | 13.9% | 11.7% | −2.2% | 3.6E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| INPP5J | cg18053607 | 22 | 31518963 | R | INPP5J | 5′UTR | opensea | 47.2% | 42.3% | −4.9% | 3.5E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| DIP2C | cg18072147 | 10 | 712592 | F | DIP2C | Body | shore | x | x | 35.6% | 24.2% | −11.4% | 3.7E-06 | 2.2E-02 |

| CEP97 | cg23048036 | 3 | 101442954 | R | CEP97 | TSS1500 | shore | 9.0% | 12.2% | 3.3% | 3.6E-06 | 2.2E-02 | ||

| PISD | cg27454842 | 22 | 32027588 | R | PISD | TSS1500 | shore | x | 57.1% | 51.8% | −5.3% | 3.8E-06 | 2.2E-02 | |

| RP11-465B22.5 | cg16989340 | 1 | 1084147 | F | IGR | opensea | 75.6% | 73.6% | −2.0% | 4.1E-06 | 2.3E-02 | |||

| INPP5J | cg26373518 | 22 | 31518942 | R | INPP5J | TSS200 | opensea | 45.1% | 39.6% | −5.6% | 4.1E-06 | 2.3E-02 | ||

| FAM91A1 | ch.8.2465681F | 8 | 89645708 | F | IGR | opensea | 5.1% | 6.3% | 1.2% | 4.1E-06 | 2.3E-02 | |||

| HGS | cg22519420 | 17 | 79668370 | F | HGS | Body | shore | 79.7% | 76.8% | −2.9% | 4.2E-06 | 2.3E-02 | ||

| C3 | cg03015114 | 1 | 6638504 | R | TAS1R1 | Body | shore | 62.7% | 58.6% | −4.0% | 4.8E-06 | 2.4E-02 | ||

| CTNNA3 | cg05626013 | 10 | 68685252 | R | CTNNA3 | Body | opensea | x | 46.8% | 51.6% | 4.8% | 4.7E-06 | 2.4E-02 | |

| HIST1H2AI | cg08039385 | 6 | 27776329 | F | HIST1H2AI | 1stExon | shore | x | 22.7% | 20.2% | −2.5% | 4.5E-06 | 2.4E-02 | |

| SLC25A31 | cg11060673 | 4 | 128651206 | F | SLC25A31 | TSS1500 | shore | x | 52.2% | 56.6% | 4.4% | 4.7E-06 | 2.4E-02 | |

| AZI1 | cg13535852 | 17 | 79173823 | R | AZI1 | Body | shelf | 89.8% | 88.8% | −1.0% | 4.8E-06 | 2.4E-02 | ||

| C19orf35 | cg17437218 | 19 | 2278847 | F | C19orf35 | Body | island | 87.1% | 85.9% | −1.2% | 4.8E-06 | 2.4E-02 | ||

| C3orf45 | cg18343556 | 3 | 50316384 | R | C3orf45 | TSS200 | shore | x | 80.5% | 77.6% | −2.9% | 4.9E-06 | 2.4E-02 | |

| HIST1H2AJ | cg20478264 | 6 | 27782176 | R | HIST1H2AJ | 1stExon | shore | 31.3% | 27.0% | −4.3% | 4.8E-06 | 2.4E-02 | ||

| MID1IP1 | cg26129027 | X | 38662279 | F | MID1IP1 | 5′UTR | shore | 40.4% | 35.9% | −4.5% | 4.8E-06 | 2.4E-02 | ||

| CGB2 | cg11177404 | 19 | 49535079 | R | CGB2 | TSS200 | opensea | 38.9% | 36.0% | −2.9% | 5.1E-06 | 2.5E-02 | ||

| WSB2 | cg04106489 | 2 | 95963068 | F | KCNIP3 | TSS200 | opensea | 85.7% | 84.2% | −1.5% | 5.4E-06 | 2.6E-02 | ||

| DHX15 | cg12857541 | 4 | 24583375 | R | DHX15 | Body | shelf | 55.3% | 59.9% | 4.6% | 5.6E-06 | 2.7E-02 | ||

| API5 | cg22764193 | 11 | 43333145 | F | API5 | TSS1500 | shore | 9.8% | 12.3% | 2.5% | 5.6E-06 | 2.7E-02 | ||

| MVP | cg13906968 | 16 | 29831676 | R | MVP | TSS200 | shelf | 73.4% | 69.0% | −4.4% | 5.9E-06 | 2.8E-02 | ||

| RPS21 | cg26145511 | 20 | 60953415 | R | IGR | island | 88.0% | 86.6% | −1.4% | 5.9E-06 | 2.8E-02 | |||

| TBXA2R | cg05343404 | 19 | 3608327 | F | TBXA2R | TSS1500 | shore | x | 87.1% | 85.4% | −1.7% | 6.2E-06 | 2.9E-02 | |

| TMEM145 | cg13542542 | 19 | 42821106 | R | TMEM145 | Body | shelf | 78.3% | 76.5% | −1.8% | 6.3E-06 | 2.9E-02 | ||

| BPNT1 | cg04282258 | 11 | 18211034 | F | IGR | island | x | 36.2% | 37.9% | 1.6% | 7.3E-06 | 3.3E-02 | ||

| KRT81 | cg12231340 | 12 | 52685221 | F | KRT81 | 1stExon | island | 13.7% | 11.3% | −2.4% | 7.2E-06 | 3.3E-02 | ||

| FAM118A | cg12262698 | 22 | 45704988 | R | FAM118A | TSS1500 | shore | 8.5% | 10.6% | 2.1% | 7.4E-06 | 3.3E-02 | ||

| C7orf36 | cg27377749 | 7 | 39605536 | R | C7orf36 | TSS1500 | shore | 8.5% | 11.1% | 2.6% | 7.6E-06 | 3.4E-02 | ||

| FLJ45079 | cg05264101 | 12 | 120729684 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 6.3% | 5.3% | −1.0% | 7.8E-06 | 3.4E-02 | ||

| TLK2 | cg07466783 | 17 | 60691727 | F | TLK2 | 3′UTR | opensea | 46.8% | 50.3% | 3.5% | 8.4E-06 | 3.5E-02 | ||

| CDC42EP2 | cg12562828 | 11 | 65076843 | R | IGR | opensea | 85.1% | 83.1% | −2.1% | 8.4E-06 | 3.5E-02 | |||

| DIP2C | cg12760625 | 10 | 712442 | R | DIP2C | Body | shore | 26.2% | 18.4% | −7.7% | 8.4E-06 | 3.5E-02 | ||

| GNGT2 | cg23572751 | 17 | 47270556 | R | IGR | shore | x | 24.7% | 21.0% | −3.7% | 8.4E-06 | 3.5E-02 | ||

| SERPINH1 | cg26104986 | 11 | 75275303 | F | SERPINH1 | 5′UTR | shore | 83.3% | 81.0% | −2.3% | 8.2E-06 | 3.5E-02 | ||

| TAS1R1 | cg02954884 | 19 | 7910696 | F | EVI5L | 5′UTR | shore | 85.9% | 84.1% | −1.8% | 8.5E-06 | 3.5E-02 | ||

| C13orf45 | cg10645091 | 13 | 76445055 | R | IGR | opensea | x | 6.4% | 7.6% | 1.2% | 9.2E-06 | 3.7E-02 | ||

| CAP1 | cg15568225 | 1 | 40537438 | F | CAP1 | 3′UTR | opensea | 58.1% | 62.0% | 3.8% | 9.1E-06 | 3.7E-02 | ||

| MTAP | cg03724238 | 22 | 32598681 | F | RFPL2 | 1stExon | opensea | 26.8% | 28.3% | 1.5% | 9.4E-06 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| PML | cg01947066 | 15 | 74289586 | R | PML | Body | shore | 70.4% | 63.4% | −7.0% | 1.0E-05 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| SLC16A9 | cg13525697 | 10 | 61320994 | R | IGR | opensea | 89.0% | 86.9% | −2.1% | 9.7E-06 | 3.8E-02 | |||

| SLC44A4 | cg18949702 | 6 | 31832486 | F | SLC44A4 | Body | shore | 85.2% | 83.0% | −2.1% | 1.0E-05 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| SLC29A2 | cg19347288 | 11 | 66135554 | R | SLC29A2 | Body | shelf | 84.9% | 82.9% | −2.0% | 1.0E-05 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| MTRNR2L1 | cg25219874 | 17 | 22193751 | F | IGR | shore | x | 20.5% | 16.2% | −4.3% | 1.0E-05 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| FAM91A1 | ch.8.2465681F | 8 | 124800139 | F | FAM91A1 | Body | opensea | 6.4% | 7.8% | 1.4% | 9.9E-06 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| ITPKC | cg21869046 | 19 | 41225005 | R | ITPKC | Body | shore | 28.2% | 17.9% | −10.3% | 1.0E-05 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| PDCD1 | cg00795812 | 2 | 242802009 | F | PDCD1 | TSS1500 | shelf | 86.2% | 83.7% | −2.5% | 1.0E-05 | 3.8E-02 | ||

| APC2 | cg23291200 | 19 | 1473179 | R | APC2 | 3′UTR | island | 83.1% | 82.0% | −1.1% | 1.1E-05 | 4.0E-02 | ||

| POLR1A | cg04771206 | 13 | 45153489 | F | IGR | shore | 9.1% | 10.8% | 1.7% | 1.1E-05 | 4.0E-02 | |||

| DCAF4L1 | cg16000989 | 4 | 41983716 | F | DCAF4L1 | 5′UTR | shore | x | 4.1% | 4.9% | 0.8% | 1.2E-05 | 4.2E-02 | |

| ABR | cg17018021 | 17 | 1029394 | F | ABR | Body | shore | x | 83.8% | 82.2% | −1.5% | 1.2E-05 | 4.3E-02 | |

| TRIO | cg00940867 | 5 | 14055789 | F | IGR | opensea | x | 86.0% | 83.4% | −2.6% | 1.2E-05 | 4.3E-02 | ||

| RFPL2 | cg03477302 | 9 | 5109889 | R | JAK2 | Body | shore | 45.7% | 49.5% | 3.8% | 1.2E-05 | 4.3E-02 | ||

| BLM | cg22690576 | 15 | 91260127 | R | BLM | TSS1500 | shore | 12.8% | 10.4% | −2.3% | 1.2E-05 | 4.4E-02 | ||

| EVI5L | cg02836017 | 17 | 7231188 | R | NEURL4 | Body | shore | 85.6% | 84.0% | −1.6% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | ||

| GABBR1 | cg17053201 | 6 | 29593246 | R | GABBR1 | Body | shelf | 84.3% | 81.1% | −3.2% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | ||

| DUSP8 | cg02248763 | 11 | 1580098 | F | DUSP8 | Body | shore | 92.9% | 94.0% | 1.1% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | ||

| SNAR-F | cg07516355 | 19 | 51073535 | F | IGR | shelf | 82.6% | 79.6% | −3.0% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | |||

| PTGIR | cg07780534 | 19 | 47116777 | R | IGR | opensea | 37.3% | 34.4% | −3.0% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | |||

| FCER2 | cg11445324 | 19 | 7751013 | F | IGR | shelf | 89.4% | 88.2% | −1.2% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | |||

| MARCH10 | cg17050097 | 17 | 60783168 | F | MARCH10 | Body | shore | x | 74.0% | 70.0% | −4.0% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | |

| PRDX1 | cg18288967 | 1 | 45987694 | F | PRDX1 | TSS200 | island | x | 18.1% | 19.9% | 1.8% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | |

| PSORS1C1 | cg21084702 | 6 | 31107663 | R | PSORS1C1 | Body | opensea | 79.0% | 76.4% | −2.6% | 1.3E-05 | 4.4E-02 | ||

| PRIM2 | ch.6.57776846F | 6 | 57668889 | F | IGR | opensea | 6.9% | 9.4% | 2.5% | 1.4E-05 | 4.4E-02 | |||

| MIR5093 | cg00453202 | 16 | 85482380 | F | IGR | opensea | 72.4% | 69.5% | −3.0% | 1.4E-05 | 4.5E-02 | |||

| OR1F1 | cg27116061 | 16 | 3239638 | R | IGR | shore | x | 17.8% | 14.2% | −3.5% | 1.4E-05 | 4.5E-02 | ||

| TNS1 | cg09859492 | 2 | 218723349 | R | TNS1 | Body | opensea | 86.9% | 85.6% | −1.3% | 1.5E-05 | 4.7E-02 | ||

| MMP16 | ch.8.1820050F | 7 | 141059306 | F | IGR | opensea | 4.3% | 5.2% | 0.8% | 1.5E-05 | 4.7E-02 | |||

| C8orf38 | cg02693150 | 1 | 963599 | F | AGRN | Body | shore | 91.8% | 90.9% | −1.0% | 1.5E-05 | 4.7E-02 |

Figure 3. Volcano and Manhattan plots illustrating the region, magnitude and statistical significance of methylation changes in smokers compared with controls.

The volcano plot (left) clearly shown the bias toward reduced methylation in smokers compared with controls. Blue points meet the threshold for statistical significance after Benjamini-Hochberg correction. The Manhattan plot (right) shows general dispersion of significantly differentially methylated sites across the genome. The horizontal line at –log10(p) ~4.8 indicates the Benjamini-Hochberg threshold for significance.

Figure 4. The association of significantly differentially methylated CpGs with GpG island context (A) and sites associated with histone retention and histone tail modification in sperm (B).

These associations were compared to what would be expected based on the frequency of associations for the background data set (all probes tiled on the 450k array). We found that CpGs differentially methylated in smokers were significantly reduced at CpG Islands (p<0.0001) compared to background and significantly enriched at CpG Shores (p<0.0001) based on expected values. Further, we identified significant enrichment in regions with histone retention in sperm in general (p=0.0042) and at sites with H3K4 (p=0.018). *** indicates p<0.001, ** indicates p<0.01, * indicates p<0.05.

While the locations of differentially methylated CpGs were strongly associated with specific genomic features and chromatin architecture, they were not associated with a specific gene class based on GO term analysis.

Several studies have found that while the great majority of the genome undergoes demethylation during early embryonic development and again during primordial germ cell migration to the gonadal ridge, a small proportion of the genome retains methylation through one or both waves of demethylation. Those regions include LINE1, SINE, intracisternal A particles (IAPs), Alu, ERVK, and alpha satellite regions (Guo et al., 2015; Seisenberger et al., 2012) as well as several hundred genes (Gkountela et al., 2015). Repeat elements are not represented on the array; however we evaluated the overlap of those genes that escape demethylation (Gkountela et al., 2015) with the differentially methylated CpGs we identified in the current study. Of the 141 differentially methylated CpGs (132 unique genes) identified in this study, eight (6.1%) were among those that display persistent methylation through early development, which represent approximately 2.7% of genes in the genome. This difference is marginally significant based on Chi-square analysis with Yates correction (p = 0.05). These regions are indicated in the “Residual Methylation” column of Table 2.

In addition to single CpG analysis, we performed regional analysis in two distinct ways to determine whether there were specific regions of the sperm genome that were differentially methylated in men who smoke. This work was performed using the differentially methylated region finder in ChAMP, and a window analysis using the methylation array scanner application in USeq, as has been previously performed in our lab (Jenkins et al., 2014a). We did not identify any significantly differentially methylated regional changes associated with smoking using either approach.

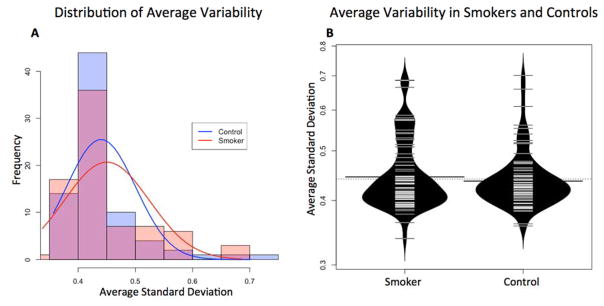

We were also interested in determining whether smoking was associated with stochastic sperm DNA methylation changes that would be apparent by evaluating the average variance from the mean for each CpGs between smokers and controls. We found a shift toward increased variation in DNA methylation in smokers compared with controls that was driven by a subset of samples though this change failed to reach significance (Fig 5). The data indicate that smoking may disrupt sperm DNA methylation fidelity to some degree, resulting in less tightly controlled sperm DNA methylation patterns, though this effect appears to vary between patients.

Figure 5. The distribution of each individual’s average standard deviation from the mean centralized normal value at each CpG as a measure of general variability.

A) Histogram with overlaid density plot of all individuals in the smokers and control groups to illustrate the generally wider distribution in the smoking group. B) Bean plot of the same distribution to illustrate the increased density of smoking samples with average standard deviations greater than 0.5. Average SD in the smoking group was slightly higher than the average in the control group due to the generally wider distribution of variability values, but this difference was not found to be significant.

An inherent complexity in performing these types of studies in humans is the inability to perfectly isolate a single lifestyle factor. In the current study, efforts were made to isolate a single variable, cigarette smoking. Smoking and non-smoking groups did not differ by age or BMI; however alcohol consumption was common in smokers selected for the study, while none of the non-smokers in the study reported alcohol consumption. In order to rule out the contribution of alcohol consumption, we performed the same differential methylation analysis described previously to evaluate methylation profiles based on alcohol consumption. We compared methylation profiles in men who smoked and consumed less than one serving of alcohol per week (n = 29) against those who smoked and consumed one or more servings per week (n = 43). Additionally, we performed the same analysis using three servings of alcohol per week as a cutoff (n = 40 consumed < 3 servings/week and n = 30 consumed ≥ 3 servings per week). In both cases, no significantly differentially methylated CpGs were identified, indicating that alcohol consumption is not influencing the results.

DISCUSSION

Our finding of a modest decline in several semen parameters is in agreement with previous studies. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis that included 20 studies with 5865 participants found that cigarette smoking was associated with significantly reduced sperm count, motility and morphology (Sharma et al., 2016). Analysis of basic semen parameters of the individuals included in the current study indicated a modest but significant reduction in semen volume (in disagreement with the meta-analysis), total sperm count, and total number of progressively motile sperm.

Previous studies have reported that cigarette smoking is associated with increased sperm DNA damage (Dai et al., 2015). As DNA damage has been proposed as a mechanism for DNA methylation changes (Russo et al., 2016), we assessed DNA damage in the samples analyzed in the current study. We used the alkaline comet assay to measure sperm DNA damage and, as reported previously, we found marginally increased DNA damage in sperm from men who smoke compared with controls (p = 0.05). While sperm DNA damage has not been precisely mapped in the context of chromatin structure, the histone-bound regions of the sperm genome are thought to be more susceptible to DNA damage than protamine-bound DNA. The current data offer evidence for an association between DNA damage in sperm and methylation changes; however, additional studies are required to characterize the nature of the association and to establish causation.

Pre-conception paternal smoking has been associated with increased incidence of numerous disorders in offspring including several types of cancer and birth defects. While cigarette smoke contains a variety of mutagenic agents, it has also been reported to impact DNA methylation patterns in peripheral blood, buccal cells and lung tissue (Ambatipudi et al., 2016; Bosse et al., 2012b; Breitling et al., 2011; Joehanes et al., 2016; K. W. Lee et al., 2013; Teschendorff et al., 2015). We hypothesized that smoking would impact DNA methylation profiles in sperm, and altered sperm DNA methylation could explain some of the increased risk to offspring health associated with paternal smoking. The primary objective of the current study was to evaluate sperm DNA methylation patterns in men who smoke compared with nonsmokers using the Illumina HumanMethylation 450k array. We identified a number of interesting and potentially important methylation alterations associated with smoking.

Global methylation levels were not different in men who did and did not smoke. However, we did find evidence for reduced sperm DNA methylation fidelity, or increased variance in methylation patterns in a subset of smokers. Interestingly, this increased variance did not seem to be related with smoking quantity or duration, suggesting that other factors might work in concert with smoke exposure to alter methylation patterns in sperm.

The most striking finding or the current study was the relatively large number of significantly differentially methylated CpGs in men who smoke as well as the genomic context of differentially methylated CpGs. We identified 141 significantly differentially methylated CpGs in sperm from smokers compared with non-smokers. In spite of the relatively large number of altered methylation sites identified, similar studies investigating the effect of cigarette smoking on DNA methylation in peripheral blood, buccal cells and lung tissue report many more differentially methylated loci (Ambatipudi et al., 2016; Bosse et al., 2012b; Breitling et al., 2011; Teschendorff et al., 2015), indicating that sperm may be less susceptible to environmentally-induced methylation alterations compared with other tissues. This is not surprising considering the importance of genetic and epigenetic integrity of male gametes for offspring health.

While the differentially methylated CpGs were not associated with a specific biological pathway or GO term, we did observe significant bias in the genomic context of altered CpGs. Differentially methylated CpGs were found at CpG islands, shores, shelves, and open seas; however, there was significant depletion of differentially methylated CpGs at islands and significant enrichment at shores. The mechanism for this bias in unclear, but it does indicate that genomic context is a driver for susceptibility to differential methylation as a result of tobacco smoke exposure. Additionally, we found that differential methylation occurred more frequently at regions previously reported to display H3K4 and H3K27 methylation in mature sperm, again suggesting that histone-bound regions may be more susceptible to methylation perturbations compared with protamine-bound regions. The apparent protection of methylation patterns conferred by protamination may explain, at least in part, the reduced effects of smoking on DNA methylation perturbations in sperm compared with other tissues. While protamination may confer a protective effect on DNA methylation perturbations in sperm, it is important to note that altered sperm DNA methylation at histone-bound loci may be more impactful on gene expression, given the importance of these regions in early embryonic development.

CONCLUSIONS

While the current study offers compelling evidence that smoking can impact sperm DNA methylation patterns in a consistent manner, replication studies in larger cohorts as well as functional studies are required to understand the potential for sperm DNA methylation alterations to be transmitted to offspring or to otherwise affect offspring phenotype. In order for sperm DNA methylation patterns to impact offspring phenotype, alterations must escape the epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during early embryogenesis, when most, but not all DNA methylation marks are erased and subsequently re-established in a tissue-specific manner. Alternatively, even if altered DNA methylation is not directly passed on to offspring, the alterations might impact early embryonic gene expression or modify reprogramming or early development in other ways. These are important areas for future research.

Altered sperm DNA methylation resulting from paternal exposures or lifestyle factors is a plausible mechanism for phenotype modification in offspring, however, additional studies in humans and animal models are needed to characterize the types of exposures that can impact sperm epigenetics. Additional studies similar to the one described here targeting other exposures will offer insight into the nature of those genomic regions that are particularly susceptible to methylation change. Finally, controlled, multigenerational animal studies are required to assess the transmission of altered sperm DNA methylation patterns to offspring and the potential for those alterations to be perpetuated across generations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, USA (R01HD082062).

References

- Ambatipudi S, Cuenin C, Hernandez-Vargas H, Ghantous A, Le Calvez-Kelm F, Kaaks R, et al. Tobacco smoking-associated genome-wide DNA methylation changes in the epic study. Epigenomics. 2016;8(5):599–618. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber R, Plumb MA, Boulton E, Roux I, Dubrova YE. Elevated mutation rates in the germ line of first- and second-generation offspring of irradiated male mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(10):6877–6882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102015399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber RC, Dubrova YE. The offspring of irradiated parents, are they stable? Mutation research. 2006;598(1–2):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse Y, Postma DS, Sin DD, Lamontagne M, Couture C, Gaudreault N, et al. Molecular signature of smoking in human lung tissues. Cancer research. 2012a;72(15):3753–3763. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse Y, Postma DS, Sin DD, Lamontagne M, Couture C, Gaudreault N, et al. Molecular signature of smoking in human lung tissues. Cancer Res. 2012b;72(15):3753–3763. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling LP, Yang R, Korn B, Burwinkel B, Brenner H. Tobacco-smoking-related differential DNA methylation: 27k discovery and replication. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(4):450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton CV, Byun HM, Wenten M, Pan F, Yang A, Gilliland FD. Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure affects global and gene-specific DNA methylation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180(5):462–467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0135OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JS, Selvin S, Metayer C, Crouse V, Golembesky A, Buffler PA. Parental smoking and the risk of childhood leukemia. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1091–1100. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresci M, Foffa I, Ait-Ali L, Pulignani S, Gianicolo EA, Botto N, Picano E, Andreassi MG. Maternal and paternal environmental risk factors, metabolizing gstm1 and gstt1 polymorphisms, and congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(11):1625–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai JB, Wang ZX, Qiao ZD. The hazardous effects of tobacco smoking on male fertility. Asian J Androl. 2015;17(6):954–960. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.150847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, Weitzman M. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children’s health. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4 Suppl):1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly ET, McClure N, Lewis SE. The effect of ascorbate and alpha-tocopherol supplementation in vitro on DNA integrity and hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA damage in human spermatozoa. Mutagenesis. 1999;14(5):505–512. doi: 10.1093/mutage/14.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrova YE. Radiation-induced transgenerational instability. Oncogene. 2003;22(45):7087–7093. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrova YE, Hickenbotham P, Glen CD, Monger K, Wong HP, Barber RC. Paternal exposure to ethylnitrosourea results in transgenerational genomic instability in mice. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2008;49(4):308–311. doi: 10.1002/em.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes A, Munoz A, Barnhart K, Arguello B, Diaz M, Pommer R. Recent cigarette smoking and assisted reproductive technologies outcome. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkountela S, Zhang KX, Shafiq TA, Liao WW, Hargan-Calvopina J, Chen PY, Clark AT. DNA demethylation dynamics in the human prenatal germline. Cell. 2015;161(6):1425–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glen CD, Dubrova YE. Exposure to anticancer drugs can result in transgenerational genomic instability in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(8):2984–2988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119396109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Yan L, Guo H, Li L, Hu B, Zhao Y, et al. The transcriptome and DNA methylome landscapes of human primordial germ cells. Cell. 2015;161(6):1437–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud SS, Nix DA, Zhang H, Purwar J, Carrell DT, Cairns BR. Distinctive chromatin in human sperm packages genes for embryo development. Nature. 2009;460(7254):473–478. doi: 10.1038/nature08162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CM, Lewis SE, McKelvey-Martin VJ, Thompson W. Reproducibility of human sperm DNA measurements using the alkaline single cell gel electrophoresis assay. Mutat Res. 1997;374(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TG, Aston KI, Cairns BR, Carrell DT. Paternal aging and associated intraindividual alterations of global sperm 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine levels. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(4):945–951. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TG, Aston KI, Hotaling JM, Shamsi MB, Simon L, Carrell DT. Teratozoospermia and asthenozoospermia are associated with specific epigenetic signatures. Andrology. 2016;4(5):843–849. doi: 10.1111/andr.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TG, Aston KI, Pflueger C, Cairns BR, Carrell DT. Age-associated sperm DNA methylation alterations: Possible implications in offspring disease susceptibility. PLoS genetics. 2014a;10(7):e1004458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TG, Aston KI, Pflueger C, Cairns BR, Carrell DT. Age-associated sperm DNA methylation alterations: Possible implications in offspring disease susceptibility. PLoS genetics. 2014b;10(7):e1004458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji BT, Shu XO, Linet MS, Zheng W, Wacholder S, Gao YT, Ying DM, Jin F. Paternal cigarette smoking and the risk of childhood cancer among offspring of nonsmoking mothers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(3):238–244. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joehanes R, Just AC, Marioni RE, Pilling LC, Reynolds LM, Mandaviya PR, et al. Epigenetic signatures of cigarette smoking. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9(5):436–447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert BR, Haberg SE, Nilsen RM, Wang X, Vollset SE, Murphy SK, Huang Z, Hoyo C, Midttun O, Cupul-Uicab LA, Ueland PM, Wu MC, Nystad W, Bell DA, Peddada SD, London SJ. 450k epigenome-wide scan identifies differential DNA methylation in newborns related to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Environmental health perspectives. 2012;120(10):1425–1431. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiziler AR, Aydemir B, Onaran I, Alici B, Ozkara H, Gulyasar T, Akyolcu MC. High levels of cadmium and lead in seminal fluid and blood of smoking men are associated with high oxidative stress and damage in infertile subjects. Biological trace element research. 2007;120(1–3):82–91. doi: 10.1007/s12011-007-8020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli A, Garcia MA, Miller RL, Maher C, Humblet O, Hammond SK, Nadeau K. Secondhand smoke in combination with ambient air pollution exposure is associated with increasedx cpg methylation and decreased expression of ifn-gamma in t effector cells and foxp3 in t regulatory cells in children. Clinical epigenetics. 2012;4(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman MN, Bakker H, Franco OH, Hofman A, Taal HR, Jaddoe VW. Fetal smoke exposure and kidney outcomes in school-aged children. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(3):412–420. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikauskas V, Blaustein D, Ablin RJ. Cigarette smoking and its possible effects on sperm. Fertil Steril. 1985;44(4):526–528. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KM, Ward MH, Han S, Ahn HS, Kang HJ, Choi HS, Shin HY, Koo HH, Seo JJ, Choi JE, Ahn YO, Kang D. Paternal smoking, genetic polymorphisms in cyp1a1 and childhood leukemia risk. Leuk Res. 2009;33(2):250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KW, Pausova Z. Cigarette smoking and DNA methylation. Front Genet. 2013;4:132. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti F, Rowan-Carroll A, Williams A, Polyzos A, Berndt-Weis ML, Yauk CL. Sidestream tobacco smoke is a male germ cell mutagen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(31):12811–12814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106896108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CY, Bristor D, Hiller M, Clarke SL, Schaar BT, Lowe CB, Wenger AM, Bejerano G. Great improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(5):495–501. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritsugu KP. The 2006 report of the surgeon general: The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. American journal of preventive medicine. 2007;32(6):542–543. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris TJ, Butcher LM, Feber A, Teschendorff AE, Chakravarthy AR, Wojdacz TK, Beck S. Champ: 450k chip analysis methylation pipeline. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(3):428–430. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Pruss-Ustun A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: A retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):139–146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang D, McNally R, Birch JM. Parental smoking and childhood cancer: Results from the united kingdom childhood cancer study. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(3):373–381. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera F, Herbstman J. Prenatal environmental exposures, epigenetics, and disease. Reproductive toxicology. 2011;31(3):363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyzos A, Schmid TE, Pina-Guzman B, Quintanilla-Vega B, Marchetti F. Differential sensitivity of male germ cells to mainstream and sidestream tobacco smoke in the mouse. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2009;237(3):298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo G, Landi R, Pezone A, Morano A, Zuchegna C, Romano A, Muller MT, Gottesman ME, Porcellini A, Avvedimento EV. DNA damage and repair modify DNA methylation and chromatin domain of the targeted locus: Mechanism of allele methylation polymorphism. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33222. doi: 10.1038/srep33222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz DA, Schwingl PJ, Keels MA. Influence of paternal age, smoking, and alcohol consumption on congenital anomalies. Teratology. 1991;44(4):429–440. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420440409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V. A review of human carcinogens--part e: Tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. The lancet oncology. 2009;10(11):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seisenberger S, Andrews S, Krueger F, Arand J, Walter J, Santos F, Popp C, Thienpont B, Dean W, Reik W. The dynamics of genome-wide DNA methylation reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Mol Cell. 2012;48(6):849–862. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Harlev A, Agarwal A, Esteves SC. Cigarette smoking and semen quality: A new meta-analysis examining the effect of the 2010 world health organization laboratory methods for the examination of human semen. Eur Urol. 2016;70(4):635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanes C, Koplin J, Skulstad SM, Johannessen A, Bertelsen RJ, Benediktsdottir B, et al. Father’s environment before conception and asthma risk in his children: A multi-generation analysis of the respiratory health in northern europe study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teschendorff AE, Yang Z, Wong A, Pipinikas CP, Jiao Y, Jones A, Anjum S, Hardy R, Salvesen HB, Thirlwell C, Janes SM, Kuh D, Widschwendter M. Correlation of smoking-associated DNA methylation changes in buccal cells with DNA methylation changes in epithelial cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):476–485. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vine MF. Smoking and male reproduction: A review. Int J Androl. 1996;19(6):323–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1996.tb00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word B, Lyn-Cook LE, Jr, Mwamba B, Wang H, Lyn-Cook B, Hammons G. Cigarette smoke condensate induces differential expression and promoter methylation profiles of critical genes involved in lung cancer in nl-20 lung cells in vitro: Short-term and chronic exposure. International journal of toxicology. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1091581812465902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Savitz DA, Schwingl PJ, Cai WW. A case-control study of paternal smoking and birth defects. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21(2):273–278. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwink N, Jenetzky E, Brenner H. Parental risk factors and anorectal malformations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.