Summary

This article rethinks the formative decades of American drug wars through a social history of addiction to pharmaceutical narcotics, sedatives, and stimulants in the first half of the twentieth century. It argues, first, that addiction to pharmaceutical drugs is no recent aberration; it has historically been more extensive than “street” or illicit drug use. Second, it argues that access to psychoactive pharmaceuticals was a problematic social entitlement constructed as distinctively medical amid the racialized reforms of the Progressive Era. The resulting drug control regime provided inadequate consumer protection for some (through the FDA), and overly punitive policing for others (through the FBN). Instead of seeing these as two separate stories—one a liberal triumph and the other a repressive scourge—both should be understood as part of the broader establishment of a consumer market for drugs segregated by class and race like other consumer markets developed in the era of Progressivism and Jim Crow.

Keywords: pharmaceutical history, drug and alcohol history, race, addiction

When the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed tightening limits on medical use of amphetamines in 1973, it expected howls from a pharmaceutical industry legendary for its antiregulatory prowess. But the new limits also provoked other, less predictable protests. “I suppose I could be considered one of the silent majority,” an Arizona man wrote to his congressman. “One by one they are disappearing—our freedoms—down the bureaucratic drain.”1 Another woman wrote directly to the FDA: “I feel that my rights as a citizen of the United States has been infringed upon… . Whatever happened to free enterprise, or do we really have something else?”2 Wrote another, “I, as one American citizen make demand at this writing to restore all the drugs people need … too many people are suffering because of being penalized on account of the drug abusers … if the drug works for them, they should have the American privilege to obtain it … this is still a free country, and we will not submit ourselves to dictatorial powers.”3

These and other letters were a sign that something strange was happening in America's recently declared drug war. On the one hand, they shared the instantly recognizable political rhetoric of the so-called Silent Majority: white voters, many of them formerly Democrats, courted by presidential candidate (and then president) Richard M. Nixon through appeals to their sense of lost status in the face of civil rights and other social changes of the era. These were the kind of people who had enthusiastically supported “law and order” politicians and their war against drugs.4

On the other hand, the letters were also written by clients of what would in the twenty-first century be called a “pill mill,” that is, a clinic whose main purpose was to sell prescriptions for psychoactive pharmaceuticals—in this case, amphetamine. Yet the letter writers were conspicuously unconcerned about being targeted as drug addicts. Instead, they openly announced their dependence on amphetamine to federal authorities and complained about their supply being shut off. Their doctors were similarly outraged, and similarly unworried about being seen as “drug dealers.” Claiming to have “ladies who need these pills for pep,” for example, one Wisconsin physician fumed in 1977 that “if amphetamines are prohibited … I'll go underground or you'll see a big jump in the narcolepsy cases around here.”5

The sense of entitlement that so clearly marks these letters does not fit easily into existing historical narratives about drugs in America. These narratives fall into two distinct scholarly fields. The first, what might be called “drug war” historiography, examines heroin, cocaine, and marijuana, focusing on illicit trafficking and use, as well as the policing and medical responses to the compulsive, harmful use known as addiction. A central theme of this scholarship is the origins and phases of the twentieth century's “drug wars,” characterized by cultural stigmatization and punitive policing of illicit drug users, especially (but not exclusively) the nonwhite urban poor. In this literature drug users (and drug sellers) are far from entitled; instead they are demonized, persecuted, and punished. At most they embrace a rebellious or even outlaw identity.6

Meanwhile, scholars in the second field, pharmaceutical history, explore a wide range of legally manufactured medicines of which psychoactive drugs make up just one part. They track the origins and growth of the pharmaceutical industry, the evolution of medical research and therapeutic practices, and the contested development of federal regulations. A central theme in their scholarship is the drug industry's quest to build mass consumer markets by influencing research, outfoxing regulators, intensively marketing their drugs, and, ultimately, redefining health, illness, and therapy.7 The biggest role for psychoactive medicine users in this story is to be studied, enticed, and exploited (or sometimes helped) by pharmaceuticals companies. Drug sellers—physicians—play similar roles. In this story, when end consumers or physicians throw off their passivity to act intentionally or collectively, it is to condemn overuse of drugs rather than to insist on their right to more of them.

These are two very different schools of scholarship, with their own central narratives and their own scholarly organizations, journals, and conferences, and associated with two very different political projects.8 One critiques antidrug moral panics while the other critiques prodrug marketing. One sees the state as problematically strong, the other sees the state as problematically weak. One sometimes questions the conceptual validity of “addiction,” the other identifies it as one among many self-evidently harmful drug risks downplayed by industry.

No matter how careful or nuanced individual histories may be, this overall historiographical structure recapitulates one of the most problematic aspects of the story it tells: the division of drug users into illicit pleasure seekers and licit health seekers. This is strange, because even a cursory reading of existing literature makes clear that there has been a vast middle ground between those two ideal types, and that categories like “pleasure” and “health” have changed, often dramatically, over time. In this article I explore that vast middle ground during the “classic era” of American drug control—from the early 1920s to the 1960s—and imagine what American drug history might look like if it were not divided by these historically constructed categories.

This exploration involves three main tasks. The first is historiographical, and involves reading together the divided historical literature on the origins of American drug wars and pharmaceutical regulations in the Progressive Era. Pharmaceutical historians rightly focus on the Food and Drug Act of 1906, interpreting it as a flawed and partial, but hard-won and pioneering, liberal victory in the long and contested process of building the federal regulatory state. Drug war historians, meanwhile, focus on the Harrison Anti-Narcotic Act of 1914 and tell a very different story, not of new consumer protections, but of how a new branch of the regulatory state evolved into a long-lasting tool for punitively policing and racially stigmatizing the urban poor. Borrowing from Joseph Gabriel's conceptual framework, I reimagine both stories as part of the same overall process: the development of modern commercial markets for psychoactive drugs. To enable these markets reformers redefined and strengthened divisions between “medical” and “nonmedical” drug use and sales, thus obscuring the reality that much, perhaps most, psychoactive drug use did not belong fully to either category.

Second, I use existing literature and new primary research to make direct comparisons between use of psychoactive pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical drugs in the twentieth century. In doing so I provide evidence for facts that are widely believed but which have not been fully substantiated, especially for the first half of the twentieth century: first, that a majority of psychoactive drug use involved pharmaceuticals rather than illicit drugs such as heroin or cocaine; second, that despite its classification as “medical,” such use fostered the majority of compulsive, harmful use that would in other contexts have been identified as “addiction”; and finally, that such use was preferentially available to white, middle-class men and especially women.

Finally, I introduce new primary research to build on something suggested but not explored in current literature: the social history of psychoactive pharmaceutical markets. Historians have done an excellent job tracing how scientific research, sophisticated marketing, and relatively weak regulation helped enable mass use of tranquilizers and amphetamines after World War II. Here I argue that the social configuration of these markets in the early twentieth century encouraged pharmaceutical sellers and users to see themselves as entitled to sedatives, stimulants, and, in some cases, even narcotics. This entitlement, like the markets that enabled it, was structured but not entirely dictated by medical, state, and industry authorities. Ostensibly linked by those authorities to health-seeking behavior, in practice it was powerfully shaped by social hierarchies of class, gender, and, increasingly over time, race. And like many such privileges, it was fiercely defended by those who held it. In this way, psychoactive drugs belong in the historiography of American housing, popular entertainment, and other consumer goods whose markets were also segregated, with enormous political consequences, in the early and mid-twentieth century. That access to drugs was a problematic social entitlement—providing needed pharmaceutical relief but also exposing consumers to sometimes hidden drug risks—offers a new perspective on the costs of such social privileges.

Unlike other segregated markets, the ideological basis for divided drug consumerism is still alive and well in the twenty-first century, with serious consequences. Harsh “drug war” policies have reproduced social inequality, intensified urban crises, and, more recently, contributed significantly to the racialized carceral state. Meanwhile, insufficient pharmaceutical regulations have encouraged a boom-bust cycle in addictive medicines, enabling a series of preventable public health crises including an early twenty-first-century epidemic of prescription-opioid-related deaths. This article suggests that at least some of these troubles stem from the founding assumption that these are separate stories in the first place.

Building the Drug-Medicine Divide: A New Drug-War Origin Story

Like most societies, America has long divided psychoactive substances into medicinal and recreational categories.9 In the nineteenth century the pharmaceutical industry's products fell firmly on the medicinal side of this category, even if, like morphine and eventually cocaine, they could foster addiction. All medicines carried risks; horrifying as it was, addiction was just one of them. More salient to pharmaceutical reformers was the distinction between pure, proven, “ethical” pharmaceuticals and those that were adulterated, were counterfeit, or contained secret ingredients.10 By the early twentieth century, however, the distinction between addictive drugs and therapeutic medicines had become the centerpiece of a new federal drug control regime divided between a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and a Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN). Historians still largely honor this division, examining the two regimes as belonging to separate stories: one a heroic tale of progress toward liberal market governance, the other a tragic tale of harsh and illiberal repression.11 Here I apply Joseph Gabriel's conceptual framework to renarrate both as part of the early twentieth century's development of segregated consumerism. Together, I argue, they established what I call “white markets” for sedatives, stimulants, and narcotics as a deeply problematic social entitlement preferentially available to white, middle-class men and especially women.

In the nineteenth century opiates and cocaine were essential therapeutic tools, distinctive mainly because physicians relied on them so heavily. In some communities more than 10 percent of prescriptions included some form of opiate.12 Perhaps predictably, the lively medical trade produced a great deal of addiction among the native-born white, middle-class men and especially women who could afford doctor visits.13

By the early twentieth century, it had also spilled over into popular markets, where disreputable druggists and street peddlers in urban “vice districts” helped expand the ranks of working- and lower-class opiate users previously supplied by opium dens. As so often in American history, these class distinctions were associated with racial difference. Nonprescribed cocaine use, for example, which first spread among manual and industrial laborers, was widely understood to be common among African American workers, particularly in the South.14 Opiate users, on the other hand, were “white,” but many were immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe or their American-born children—people whose status as members of the white race was very much under debate during an era of immigration restriction and eugenics.15 The ranks of opiate addicts also included former opium smokers, many of whom were Chinese; nefarious Chinese drug sellers and addicts remained a stock figure in media coverage.16

Progressive reformers interpreted these two groups of drug users very differently. In middle-class and “Anglo Saxon” contexts, drug dependence was still seen as similar to accidental poisoning: a horrifying tragedy caused by an unregulated market. The solution, reformers believed, was stronger consumer protections such as honest labeling and higher professional standards for doctors and druggists. Once provided with full information, consumers would make rational choices and protect themselves from dangerous drugs.17 As pure food and drug champion Harvey W. Wiley explained, there was no need to prohibit any product; the only goal was to ensure that “the innocent consumer may get what he thinks he is buying.”18 This consumer-protection campaign culminated in the Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required truthful labeling of medicines and empowered the FDA to expose mislabeling, adulteration, counterfeiting, and other frauds.

Poorer urban drug users, however, were a different matter. Progressive reformers already thought little of their innate intellectual and moral capacities, and their purchase of drugs in the seamy and racially mixed worlds of urban vice rather than through the medical system only reaffirmed this prejudice. They were not potentially rational consumers victimized by market forces; they were pleasure seekers with undeveloped moral compasses.19 Their drug dependence, Progressive reformers believed, could be controlled only through prohibition and strict and punitive policing of the criminals who contravened it.20 The earliest manifestations of this approach had involved restrictions on the sale of alcohol to Native Americans, and, later, sales of narcotics to Africa and the Philippines.21 It culminated in the Harrison Anti-Narcotic Act of 1914, which began as an effort to use tax law to restrict narcotic commerce to licensed medical professionals, but which, by the 1920s, had successfully been interpreted by a new Narcotics Division of the Treasury Department as empowering them to arrest and incarcerate drug sellers and drug users they deemed “nonmedical”—a type of drug user that came to be known as a “dope fiend” or a “junkie.”22

It is important to emphasize that the Harrison Act did not purify an already-existing category of “medicines” by excluding addictive drugs. Clearly not: narcotics remained (and remain) important medicines. Instead, the act inscribed new meanings into the category of “medicines.” Medicines were now defined, in part, as those drugs produced for and used by rational consumers for therapeutic purposes. But how did one define “rational consumer” and “therapeutic purposes”? Ostensibly they referred to drug use under a physician's care. But as we will see, federal narcotics authorities controversially claimed the right to prosecute physicians for what authorities considered to be improper narcotics prescribing—in other words, a physician's expertise did not necessarily define “rational” or “therapeutic” use. Instead, as with many cultural binaries, the terms were most easily defined through opposition: rational drug users were those who were not junkies—with all the social stereotypes increasingly associated with that term. Through this backdoor cultural logic, the concept of “medicines,” like that of “drugs,” acquired a social component.

As the twentieth century wore on, race became increasingly central ingredient in that social component. The use of drugs without explicit medical sanction had long been associated by American moral crusaders with “Oriental” decline, African American barbarity (in the case of cocaine), and interracial sexual depravity.23 As Eric Schneider has shown, the structure of illicit markets formalized by the Harrison Act reinforced those racial associations. Illicit markets developed in dense urban “vice districts” near major ports that already housed a well-developed network of illicit commerce. These areas had also been shaped by ethnic and racial segregation, first of Southern and Eastern European immigrants and then, starting in the 1920s, African Americans. Over time white Americans were increasingly shut out of ever more carefully guarded illicit markets.24 Meanwhile, African Americans faced obstacles accessing medical care (and physicians' prescriptions). In practice, then, the set of morally significant behaviors associated with “medical” and “nonmedical” drug use were powerfully structured by the uneven social availability of drug markets, by class and increasingly by race, and, throughout, by gender (with white women enjoying especially privileged access to medical markets).

As divisions between medical and nonmedical drug markets became more formal, many drug sellers and drug users responded by conforming to the new expectations. Physicians reduced their prescribing,25 and sales of narcotized patent medicines dropped by 24 to 50 percent.26 Legal opium imports declined by 75 percent, and prescription surveys saw the proportion of prescriptions with morphine drop from nearly 13 percent to less than 5 percent (see Figure 1).27 Studies at the time reported fewer white, native-born, middle-class Americans claiming addiction to medically supplied morphine.28 In short, medical consumers (and sellers) appeared to be acting like the rational health seekers the markets encouraged them to be. Nonmedical drug users, on the other hand, did not abandon narcotics; instead, they shifted to easier-to-smuggle forms (for example, heroin instead of smoking opium), and came to increasingly embrace their identities as outsiders or even outlaws.29

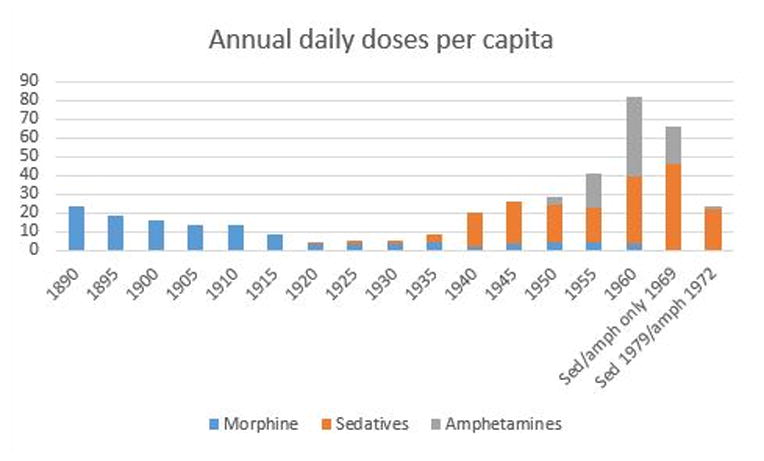

Figure 1.

Approximate annual doses per capita of selected psychoactive pharmaceuticals.

Figures are not exact due to incomplete, unreliable, and sometimes conflicting data, but overall trends are reliable. For narcotics, early numbers are drawn from Courtwright, Dark Paradise (n. 6), and later numbers from U.S. Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States and U.S. Bureau of Narcotics, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs. At time of printing I have not yet collected data on narcotics for years after 1963. Following Courtwright, all opioids were converted to their equivalent in morphine. For barbiturates, numbers are drawn from American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record 52-53 (1908): 66; U.S. Tariff Commission, Diethylbarbituric Acid and Derivatives (Government Printing Office, 1925): 3-4; U.S. Tariff Commission, Census of Dyes and Other Synthetic Organic Chemicals (Government Printing Office, annually 1922-1958); U.S. Department of Commerce, Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States, U.S. Department of Commerce, Biennial Census of Manufactures; U.S. House of Representatives, Control of Narcotics, Marihuana, and Barbiturates (Government Printing Office, 1951): 228; U.S. House of Representatives, Traffic In, and Control Of, Narcotics, Barbiturates, and Amphetamines (Government Printing Office, 1956): 208; U.S. House of Representatives, Drug Abuse Control Amendments of 1965 (Government Printing Office, 1965): 69; and Herzberg, Happy Pills (n. 7). Data for amphetamines drawn from Rasmussen, On Speed (n. 7).

As Courtwright and Acker have shown, these developments helped create expert consensus around the problem of addiction, as medical and political authorities endorsed the basic categories of the dual drug regime. Following this logic, authorities increasingly agreed that addiction was a problem of street-hustling urban “junkies” and heroin, not of patients and their medicines. The result was what historians call the “classic era of narcotic control” characterized by punitive policies justified by a steady drumbeat of antinarcotic propaganda.30

But there were many people who did not, or could not, conform their drug use to fit one or the other category.31 All the attention paid to urban, street-hustling “junkies” meant relatively little effort to identify, quantify, or study psychoactive drug users who lived outside of major cities, who continued to purchase their supply through medical markets, who might never have faced arrest or institutional treatment, or who used drugs other than heroin and cocaine.32 When one broadens the lens to include these drug users, a startling fact emerges: far from disappearing, psychoactive drug use, and the harmful kind of use associated with addiction, grew substantially within the medical system and continued to dwarf street drug problems.33 From this perspective, the mass medical markets enabled by drug reformers loom as equally important, if not more so, than the street markets they cracked down on. In the next section I turn to these “white markets,” showing how they were both encouraged and obscured by the divided drug regime even as they fostered a large volume of chronic, compulsive, and harmful use that, in other contexts, would have been understood as addiction.

White Markets for Pharmaceuticals in the “Classic Era of Narcotics Control”

“Entitled to Morphine”: White-Market Narcotics

Medical use of narcotics did not disappear entirely in the early twentieth century, and medical markets continued to support long-term use that was, at best, ambiguously therapeutic. Such “middle-ground” use was typically small in scale and took place in putatively therapeutic settings far removed from the junkie stereotype: outside of major hubs of illicit traffic like New York and Chicago; in mostly informal and noncommercial transactions; and involving only a handful of white, native-born addicts judged to have legitimate medical conditions by the prescribing physician. The persistence of this type of use despite the dedicated opposition of federal narcotics authorities showed the difficulty of policing the boundaries between “medical” and “nonmedical,” especially in cases that challenged the social logic (of class and, increasingly, of race) that helped give those categories meaning.

According to David Courtwright, American medicinal opiate use (i.e., not opium prepared for smoking) reached a height of 17.9 ounces of morphine equivalent per 1,000 people in the early 1890s. Thanks to professional reforms in medicine and pharmacy, that number dropped to 10.5 ounces in the early 1910s. After the Harrison Act it continued to drop, to 6.3 in the late 1910s and then more lastingly to 2.2 for several decades starting in the 1920s. The number began to rise again after World War II, however, perhaps boosted by the availability of synthetic narcotics such as Demerol; by the late 1950s it had risen to 3.1.34 Following Courtwright's calculations, the maximum number of addicts the 1950s volume could have supported would have been just over 100,000.35 (Of course, not all narcotics were used by addicts, and it is impossible to establish what proportion of them were. A standard Pareto distribution, for example, holds that 80 percent of a product is used by 20 percent of its consumers; this would suggest approximately 80,000 pharmaceutical narcotic addicts.)36 This estimate is far from Courtwright's maximum of 200,000 American opiate addicts in the 19th century, especially considering that the U.S. population had more than doubled, but still more than the FBN's admittedly questionable estimates of 60,000 nonmedical addicts in 1955 (see Figure 1).37

The difficulty of compiling these figures and the impossibility of knowing the medical circumstances of those prescribed narcotics are a form of evidence in their own right: they demonstrate the relatively weak surveillance and policing of physicians during this period. True, the Harrison Act gave federal authorities the power to judge whether a prescription for narcotics was written in “good faith” or not—an important and highly contested abrogation of doctors' professional autonomy. Yet the specific regulations governing “good faith” medical practice did contain wiggle room. Physicians could still prescribe at will for addicted patients they diagnosed with an incurable disease or for “an aged and infirm addict whose collapse would result from the withdrawal of the drug.”38 After the U.S. Supreme Court narrowed the Narcotics Division's authority to criminalize prescriptions to addicts in the 1925 Linder case, the regulations were amended to permit physicians to “accord temporary relief for an ordinary addict [i.e., one who was not ill or aged] whose condition demands immediate attention.”39

The wiggle room written into federal regulations was just one consequence of medical elites' reluctance to cede professional prerogatives to non-medical authorities. They opposed “dope doctors” but believed that the matter should be taken care of within the profession, not through intrusions of an agency that the American Medical Association warned might become a “federal narcotics dictator.”40 The AMA's fierce lobbying bore many fruits. Most importantly, the Narcotics Division and its successor the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) were required to give a narcotics permit to any licensed physician, even if that physician was an addict.41 Licenses, in turn, were governed by state laws, which often protected physicians' professional autonomy: by 1926 only 6 states outlawed medical maintenance of opiate addicts, and only 9 states allowed licenses to be revoked solely for violations of the Harrison Act.42 These protections could last, as they did in Wisconsin, where only violations of the state's own laws (not federal law) were grounds for revocation until 1947.43 Moreover, revocations within a state were handled exclusively by the state Medical Board—and while some boards cooperated with the FBN (notably California's),44 others did not. From 1930 to 1935, for example, 1,362 physicians were reported to state boards for narcotics violations, but only 184 licenses were revoked or suspended.45

The reluctance or even outright resistance of state medical authorities mattered a great deal at a time when practical obstacles limited federal power. The federal narcotics bureau had fewer than 300 agents to police 150,000 physicians.46 Those physicians had to keep records of their prescriptions, but tracking of those records was relatively primitive and narcotics administered in person were exempted.47

As a result of these various challenges, convictions were difficult to achieve except in the most egregious of cases, and penalties for convicted physicians were relatively mild. From 1931 to 1935 the FBN convicted only 11 percent of the registrants (physicians but also pharmacists, wholesalers, etc.) reported for violations, in contrast to the nearly 70 percent of nonregistrants (i.e., “street” peddlers and consumers) reported for violations during the same time period.48 Between 1920 and 1935 this amounted to eleven hundred physicians, an average of seventy-five per year. That is certainly enough to have made others watchful of their narcotics prescribing, as Joseph Spillane has argued.49 But on closer inspection the numbers are slightly less intimidating: they represented only 0.05 percent of physicians, or one in two thousand. But three hundred of the convictions were of doctor-addicts, not doctor-suppliers, reducing the yearly average of physicians convicted for illegal prescribing to fifty-three—0.03 percent or one out of every three thousand. Then, too, enforcement was uneven between states, meaning that some states experienced much lower conviction rates. Wisconsin's Medical Examination Board, for example, investigated only eight physicians for narcotics infractions from 1920 to 1946, and six of these were addicts who supplied only themselves. Only one physician was convicted, although several others had their licenses temporarily suspended.50 Such relatively light penalties do not seem to have been the exception; FBN Annual Reports typically reported fines of two hundred dollars and brief license suspensions.

Taken together, these figures suggest that while physicians were policed, they still enjoyed a fair amount of leeway in the provision of narcotics, at least some of which they used for purposes disapproved of by the FBN—presumably, supplying drugs to addicts.51 Reliable data on the extent of such activity are not extant, unfortunately, but the few glimpses available are suggestive. A mid-1920s survey of Detroit physicians by the National Research Council's Committee on Drug Addictions, for example, identified over five hundred regular morphine users being supplied by physicians, over half of them having received no diagnosis or simply having been diagnosed as “addicted.” The authors estimated that this would mean over thirty-five thousand medically supplied addicts nationally—a figure close to those derived earlier in this article through other methods.52

Even when physicians did change their prescribing practices, this did not always reduce provision of narcotics. By the early 1930s, for example, a national prescription survey found that the portion of prescriptions containing an opiate had rebounded fully to nineteenth-century levels, except that codeine had supplanted morphine as the most common opiate (codeine, in fact, was the most common prescription ingredient of all, second only to distilled water).53 In Detroit, for example, codeine made up 85 percent of all narcotics sales, and one researcher claimed that at least some of those sales went to long-term, high-volume users.54 And yet codeine is only a tenth as strong as morphine and is far less addictive, so this switch must be counted as a genuine public health improvement for those with access to medical narcotics markets.

But in many places efforts to change prescribing practices appear to have made much less headway. As late as 1957, for example, an FBN report on Virginia claimed that “to date, almost without exception, the traffic in narcotics in Virginia's Western District stems from diversion from registrants [i.e., sales from physicians].”55 A few years later in the early 1960s, a federal study of Kentucky—the only large-scale study conducted outside a major urban setting—found that the state had among the highest rates of addiction in the nation, and that addicts were largely “white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants” from “long-established families” who saw themselves as ill and who used morphine provided by physicians.56 A similar pattern may have held in California as well: a 1954 report commissioned by the state's attorney general claimed to have found thirty-two thousand legal narcotics users, as compared to only twenty thousand illicit users.57

All told, then, three things are clear: physicians remained a significant source of narcotics to addicts; relatively few of them were punished; and when they were, their punishments were relatively light. These circumstances owed much to the practical difficulties of policing 150,000 physicians with a rudimentary state bureaucracy: surveillance was only tight enough to catch egregious cases. But these difficulties were also compounded by the racial, class, and gender assumptions that had been built into the concept of “medical” drug use.

Take, for example, the case of Bristol, Tennessee, where in 1926 federal agents found a surprising number of addicts (upward of sixty) and soon discovered the cause: two local physicians were providing morphine to dozens of addicts, many of whom later sold some of their supply on the street.58 The agents were outraged and confronted the physicians, only to find them outraged right back. By what right, one asked in an angry letter, did an agent who “admits … he knows nothing about medicine” judge a physician's prescribing practices?59 Especially when, it turned out, those practices had been approved on a case-by-case basis by Lawrence Kolb, a psychiatrist and the nation's foremost expert on addiction, who had visited Bristol doing research for the Public Health Service.60 As Caroline Jean Acker has shown, although Kolb was best known for his influential theory that many addicts were “psychopaths,” he showed marked sympathy for many medically supplied addicts.61 That sympathy had been in full effect in Bristol. He described one patient as an “honest, hard-working man” and a “good moral citizen.” Another had only ambiguous medical need, but Kolb argued that morphine “made a more stable citizen of him”; elsewhere he approved morphine because it enabled a woman to “keep a good home.” Of one woman, he noted that “she is a steady worker and supports herself. I have no doubt she is a sufferer from some ailment.” In a few remarkable cases Kolb recommended morphine simply because the person was unlikely to quit because of the individual's “inebriate personality,” because the person's spouse was also an addict, or because quitting would cause too much suffering.62

Bristol's addicts—and the town's drug sellers—earned Kolb's sympathy by the multiple registers on which they diverged from the “junkie” stereotype. The addicts were overwhelmingly white and native-born; lived in rural areas or a small town; were middle aged; had been addicted for many years; and had been diagnosed with medical conditions such as rheumatism, tuberculosis, nervousness, asthma, or pain from injury. The importance of social factors such as race, class, and respectability in determining “medical need” for morphine is made clear by three facts. First, Kolb approved patients diagnosed with vague conditions such as “neurotic,” “nervous,” or “invalid,” or conditions for which morphine was seemingly inappropriate such as asthma or alcoholism, in the same way he approved patients with illnesses such as terminal cancer that unambiguously called for morphine.63 Second, at least some of the addicts turned out not to be suffering from the illness with which they had been diagnosed.64 And finally, even many of those with genuinely pitiable illnesses had been selling morphine on the street.65 The same held true for the drug sellers: the physicians involved were prominent local men who also had large, nonaddict practices; one had even been town mayor three times.

In the end, federal authorities determined that it would be impossible to get a conviction and so they dropped the case. The agency's postmortem on the debacle? That physicians like Kolb should not be allowed to meddle in narcotics policing—in other words, that definitions of “medical” should be in the hands of police, not physicians.66

Obviously, Bristol was just one town, and these events took place less than a decade into the fledgling drug war. And as Courtwright has observed, the South was distinctive: it appears to have had more addicts, and more addicts being supplied by physicians and pharmacists, than other regions.67 Given this, it is easy to see addiction in the South as modernizing more slowly—but still inevitably—toward the end point of city-dwelling street junkies. But regional differences were not necessarily chronological differences. Given that this method of morphine provision persisted well into the 1950s, it is more likely that American narcotics markets were enduringly divided between major cities (where non medical “street” purchase dominated) and smaller towns and rural areas (where medical provision dominated).. Most physicians may well have wished to avoid the disrepute and aggravation of dealing with addicts, but what they actually did varied depending on local circumstances. In cities, where smuggled narcotics were cheap and plentiful, anti-vice policing was at its most intense, and racialized addicts might crowd a willing doctor's waiting room (and raise the doctor's overall prescribing volume to suspicious levels), a physician had more incentive to limit prescribing. Elsewhere those incentives were weaker, and at least some physicians were willing to assist sympathetic addicts. Given the large number of physicians in America, even isolated decisions such as these would mean a relatively large number of medically supplied addicts.

Despite its persistence, however, physician-prescribed morphine addiction clearly did decline significantly from its turn-of-the-century peak, as older addicts died and fewer new addicts were created. Given the historical rarity of reining in markets for addictive drugs, even this less-than-decisive victory must be seen as a significant achievement.68 The victory is also useful in shedding light on a central drug policy debate: whether it is possible to legally maintain current addicts on their required drug without producing new cases of addiction because of the increased legal drug supply and added enforcement complexities. In the early twentieth century, many pharmaceutical addicts were maintained even as the overall rate of new pharmaceutical addictions dropped; meanwhile, “street” addicts were not similarly maintained, yet there is no parallel evidence of a decline in the number of new cases of “street” addiction. In this case, legal access to drugs and relatively effective drug policy were both social privileges restricted by race and social class.

Establishing White Markets for Sedatives and Stimulants

As narcotics prescribing was waning—or, perhaps, because narcotics prescribing was waning—pharmaceutical white markets for newer and less stigmatized drugs, especially barbiturate sedatives and amphetamine stimulants, expanded dramatically, enabling continued mass use (and addiction) by those with privileged access to the medical system.

Barbiturates, first introduced in 1903, were a comparably safe, predictable, and effective replacement for late nineteenth-century sedatives Sulfonal and Trional, which were both toxic and slow to take effect—a dangerous combination.69 Unlike the first narcotics, barbiturates were not advertised directly to the public and were available only from pharmacists. Initially this kept use relatively low, but sales increased dramatically in the 1920s—precisely when enforcement of the Harrison Act began in earnest. With the introduction of “minor tranquilizers” such as Miltown and Valium in the 1950s and 1960s, sales of pharmaceutical sedatives reached a peak of nearly ten billion doses (over fifteen doses per person) in 1969.70 Meanwhile, as Nicolas Rasmussen has shown, Benzedrine, the first amphetamine, became available in 1937 and gained wide use as a morale booster for soldiers during World War II. After the war use grew even more as the drug was marketed as an antidepressant, and another amphetamine, Dexedrine, became a wildly popular diet drug. By 1962 the FDA estimated that eight billion pills, or an astonishing forty-three per person, were being sold annually (see Figure 1).71

By the 1950s enough sedatives and stimulants were being sold to provide over fifty doses annually to every man, woman, and child in the United States. At least a quarter of all prescriptions included a sedative, tranquilizer, or stimulant (narcotics were in another 5 to 7 percent of prescriptions).72 Especially when combined with continued prescribing of narcotics, this represented a significant expansion, not a decline, in the medical provision of addictive drugs to “rational consumers” since the late nineteenth century.

The details of white-market regulations make clear that this mass drug use was an intentional aspect of America's dual drug control regime. Initially, there were no restrictions on pharmaceutical sales other than a requirement for honest labeling. It was not until the mid-1940s that prescription-only requirements gave federal authorities their first tools to restrict the volume of trade in pure, honestly labeled medicines. Even then, the law was hardly draconian: it imposed no limits on manufacturing so supply was essentially unlimited; it required no records of sales or prescriptions; it set no limits on how much or how often a physician could prescribe; and it did not outlaw possession of the drugs without a prescription. Penalties for transgressing the law were mild, at least in drug-war terms: fines, temporary suspensions, or, in rare cases, revocations of pharmacy licenses. Even these penalties were almost never administered, however, because the law was enforced by the FDA, an agency devoted to ensuring the purity and safety of legal products—devoted, in other words, to enabling, not quashing, mass use of approved drugs, and to protecting, not policing, drug users. It was not until the 1940s that the agency even began to investigate “over-the-counter” sales by druggists, and even then it was woefully undermanned for the task. By 1948 the FDA had only 230 inspectors who devoted part of their time to making “sting” purchases at the nation's 50,000 retail druggists.73

Relatively weak policing meant few limits on sales, and white markets for pharmaceutical sedatives and stimulants quickly grew to become the nation's largest sources of psychoactive substances. But like illicit drug markets, white markets were not equally available to all consumers. Schneider has shown that heroin markets during this period were located in nonwhite neighborhoods of major port cities, and were guarded by a range of hidden locales, secret passwords, and other gatekeepers that made them unavailable to all but the most persistent outsiders (including most whites).74 Pharmaceutical white markets featured similar gatekeepers, only these performed the opposite function.

The most important gatekeepers were doctors and druggists. Physicians prescribed to people who persuasively represented their suffering as medical—a task easiest for the white-collar men and especially women portrayed in medical literature (and pharmaceutical advertising) as prone to nerves, anxiety, obesity, lack of “pep,” and so forth. Once reliable data became available in the late 1960s, it was clear that white, middle-class men and especially women were the most likely people to receive prescriptions for sedatives and stimulants.75 Druggists, for their part, filled physicians' prescriptions, but also serviced a lively illicit market by “counter prescribing” or selling without a physician's approval. As we will see, even these illicit sales were not equally available, since druggists were much more likely to sell to familiar, reputable customers who would not raise suspicion.

Reinforcing physicians' and druggists' predilections was an enforcement system that could only target pharmaceutical sales that most resembled illicit “street” transactions: urban, visibly commercial, and leading to clear and tragic harm to sympathetic victims. As the FDA proudly noted in a 1960 circular to physicians, “We do not engage in random shopping of drugstores. We investigate only when we have responsible complaints—commonly from physicians, hospitals, coroners, police, or other pharmacists.”76 The agency routinely declined to prosecute cases that did not have what they called “background,” that is, “the atmosphere or reports of illicit sales to addicts,” as one memo explained, or clear and dramatic harm to innocents.77

Agents were also admonished to avoid the slightest hint of entrapment, by which the FDA meant anything that could be seen as supporting the presumptively therapeutic nature of the transaction. For example, FDA buyers should not claim they were a medical student, or “beg drugs for an allegedly sick wife or child or relatives,” or “play upon the vendor's sympathies” in any way. Instead, “an air of commercialism [should] be maintained at all times” with purchases “as large as possible” and perhaps even an open admission that “you are purchasing for use by some individual other than yourself.”78 This meant that druggists could avoid prosecution if—as one FBN agent reported from Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1948—they were “careful not to sell to persons who it appeared were using the drugs for other than medicinal purposes.”79 Such judgments were fundamentally shaped by the class and, increasingly, racial presumptions built into the medicine-drug divide in the first place. This helps explain why so many questionable transactions investigated (but rarely prosecuted) by the FDA seemed to involve, as one report put it, “quite respectable women enlisting the aid of a personal acquaintance in the profession in counter prescribing for them.”80

The difficulty in policing “respectable” consumers of medicines was even worse in small towns, where druggists often refused to sell illicitly to anyone but familiar customers. This made “sting” purchases impossible and effectively stopped enforcement in entire rural regions such as east Texas, which FDA inspectors judged to be “our greatest problem in connection with the indiscriminate sale of dangerous drugs, particularly sleeping tablets.”81 The vast majority of FDA convictions thus took place in the most urban states, with New York alone accounting for nearly 80 percent of the 564 successful cases in 1952–53. In eighteen less populous states there were no convictions, and very few in twenty-one others. This did not mean, however, that drug problems were concentrated in urbanized states—only convictions. Obscure towns like Kinston, North Carolina, appeared more often in FDA investigators' reports than major cities, and the agency filed more cases in states like Oklahoma and Nevada than anywhere else.82

White Markets and the Public Health

Thanks to weak policing and strong gatekeepers, then, white markets for pharmaceuticals provided vast quantities of powerful sedatives and stimulants to the same middle-aged and middle-class consumers who had supposedly stopped using drugs in the early twentieth century. And despite its categorization as therapeutic, drug commerce and drug use within these markets clearly produced harm as well as benefit. White markets produced the vast majority of America's drug overdose deaths, for example; fatal barbiturate overdoses alone rose nearly fivefold between 1933 and 1953 (the per-capita rate rose fourfold), reaching a high of nearly eight per hundred thousand population—a higher mark than prescription opioid deaths in 2014 during the twenty-first-century epidemic.83

It is impossible to know with certainty how many Americans were addicted to barbiturates and amphetamines during these years, but it is possible to estimate the maximum number of chronic high-dose users that the volume of drugs sold each year could have supported. For barbiturates, for example, enough was sold in the early 1920s to supply 17,000 “mild” (0.6 grams per day) or 12,000 “serious” (0.8 grams per day) addicts. By the mid-1950s, these numbers had risen to over 1.5 million mild or 1.1 million serious addicts—and these figures do not even include the minor tranquilizers, which became even more popular once they were introduced in 1955.84 Obviously not all use was by addicts, but if we again apply the Pareto distribution (in this case, at least partially warranted by research suggesting that one-fifth of sedative users had been using daily for over a year, i.e., that 20 percent of users truly were using 80 percent of the pills),85 those numbers are barely reduced below a million.

On the other hand, Rasmussen cites evidence that approximately 2 to 3 percent of those prescribed the drug in the 1960s became addicted; since 10 million Americans had been prescribed an amphetamine in 1970, this would mean 200,000 to 300,000 addicts.86 This is still a very large number, but it suggests that barbiturate estimates are too high, perhaps by as much as an order of magnitude. In any case, it is clear that the total number of medical sedative, stimulant, and narcotic addicts still equaled or exceeded the number of heroin addicts, which Courtwright estimates may have reached a peak of over 600,000 in 1970.87

The scale of these numbers is also supported by FDA enforcement records, which reveal pharmaceutical use to have been rife with behavior that, in other circumstances, would have been called “drug dealing” and “drug addiction.” Many patients took dramatic steps to secure supplies of their favored drugs, for example, such as the woman who visited multiple doctors in Las Vegas and Reno using aliases, at one point in 1956 receiving prescriptions for twelve different kinds of barbiturates from seven doctors in one day. “Due to Mrs. A's obviously ill condition,” FDA investigators noted, “she had had no trouble in obtaining the prescriptions from the physicians,” despite being a heavy drinker and having set fire to five different homes in the past two years. The FDA, concluding that the drug sales had been legal, declined to investigate.88

FDA agents also regularly encountered overprescribing physicians, such as the Omaha, Nebraska, doctor who owned a drugstore and left a pad of presigned prescription forms at the counter for his pharmacist employee to use whenever a customer needed one. Upon being criticized by the FDA, the doctor was unapologetic, saying that in the future he would have the druggist send customers to his office, where he would “glance at them” and write a prescription at no charge. The FDA saw no way to prosecute such behavior.89 In Gary, Indiana, the FDA abandoned an investigation upon discovering that unusually large sales of amphetamines at a small drugstore (over 150 bottles per day) were based on legal prescriptions by a diet-clinic physician who was also part owner of the drugstore.90

Both doctor shopping and prescription sales were fully legal, to the immense frustration of FDA investigators. “Despite our beliefs and convictions,” an FDA supervisor admonished an overeager agent, “our job is not to interfere with the practice of medicine, and regardless of motive, to do so can only invite criticism.”91 Agents were directed not to search for or even ask about overprescribing doctors; instead, problematic doctors should be “so notoriously flagrant” that they will “inevitably come to attention in the normal course of our work.”92 And even those flagrant cases might not be worth pursuing. In Hillsville, Virginia, for example, FDA agents were unable to do anything for a local sheriff who sat impotently outside a “scrip” doctor's office, arresting visibly inebriated “patients” (many from nearby Mt. Airy, North Carolina) for public intoxication as they exited.93

A druggist's own respectability could also be a protection, as happened in the case of Mt. Vernon Seminary for Girls in Washington, D.C. In 1954 the FDA flagged the school for handing out barbiturates too freely, and the investigation led to a druggist who turned out to have multiple other violations. However, he also had a “high reputation in the Georgetown section” and his clientele included “many of the most prominent, most influential and wealthiest people in the city.” His transgressions, the agency concluded, “might best be described as acts of omission rather than commission,” and the case was dropped.94 Druggists might also have powerful protectors. In Hazard, Kentucky, FDA agents successfully executed “sting” purchases from a druggist who had sold barbiturates without prescription, and found themselves explaining themselves to an irate senator, John Cooper, to whom the druggist had complained. The druggist had initially come under suspicion after one of his customers fell down a flight of stairs in a barbiturate fog, and then lay unconscious on a heat register, which burned his face beyond recognition.95

Some of the best, or at least best documented, examples of 1950s-era white markets' racial and class dimensions come from records collected in the 1970s, when the markets temporarily came under stricter policing (for complicated reasons that will be discussed briefly in the conclusion). Although the actual cases come from outside our time period, a number of them involved older physicians who came under new suspicion for practices they had followed for decades. It is thus worth taking a chronological detour to examine two particularly compelling examples from Wisconsin, whose state medical board kept unusually good records.

The first case involved Dr. Theiler, a practitioner in the tiny town of Kiel, Wisconsin (population three thousand) since 1954. In 1976 he was among dozens of physicians investigated for prescribing unusually large quantities of amphetamines, whose use had just recently been restricted by the state Medical Board.96 Under questioning at a formal disciplinary hearing, Theiler confidently explained that he ignored prescribing guidelines as he saw fit, giving amphetamines to help patients maintain normal weight (rather than to diet); to “make them feel a little peppier,” especially when they “happen to be a little depressed or slightly tired in the morning”; to help working housewives “keep up with the housework”; and, sometimes, simply because they “are paying for an office call [and] want relief—they don't want you to say go home and take two aspirins.” Many patients received near-automatic refills with only a brief examination by an untrained office “nurse.” Ironically, Theiler—the town's single largest purveyor of drugs—reassured authorities that Kiel had no “black market” for pills, at least, “nothing like the city.”97

The second case involved Dr. Balcunias, another small-town Wisconsin physician caught up in the 1976 dragnet for amphetamine prescribing. Like Theiler, Balcunias was unembarrassed, claiming that “I prescribe controlled substances only for patients I know well and who I feel will not abuse the drug.” For example, he continued, he refused to prescribe amphetamines to “those on welfare”: “I recommend cutting their welfare benefits to force them to reduce weight.”98 He claimed to be mystified that anyone would doubt a physician like him, who had practiced for five decades without ever having a complaint lodged against him.99 Balcunias had a point: dispensing drugs freely to known and trusted patients of preferred race and class status had, for most of his life, been a perfectly legal and appropriate part of medical practice.100

Theiler and Balcunias's sense of therapeutic entitlement was also shared by many pharmacists. In another Wisconsin case, this one from 1960, a pharmacist who operated in the solidly middle-class Milwaukee neighborhood of Tippecanoe was charged by the State Pharmacy Examining Board with refilling a Dexedrine prescription without a physician's approval. The pharmacist willingly confessed to the crime but clearly believed that state authorities should respect his judgment:

I don't know why we have to go through such lengths to build up such a case against me… . I don't think I am that bad a character… . I don't think I have violated the laws very often… . I think we run a nice store in Milwaukee. I think it is the top store, in fact, in the city… . The only thing I can ask for is leniency and that is about it. After all, I wish to continue in the business. It has been good to me.101

The pharmacist's remarkable lack of concern about his actions was mirrored by his customer's dubious insistence that she was an entirely passive victim in the transaction. When asked if she knew what the prescription was for she played dumb: “well, no, not exactly. I just—I am not familiar with anything of that sort.”102 Whether she was telling the truth or not, it was a revealing statement, and the board's unquestioning acceptance of it similarly revealing. In white markets, rational consumers had no desire to use drugs and took no pleasure from them; they were, or at least could be, health-seeking innocents trusting in the advice of their professional caregivers. Customers like the Tippecanoe woman received no punishment—possession was not a crime, after all—and her pharmacist had his license suspended briefly. Such consequences may seem appropriate and fair, but this in itself is a remarkable thing in the context of American narcotics laws, which, in 1960, regularly sentenced transgressors to long (even life) prison sentences.103

None of this is to say that problems with barbiturate “goof balls” and amphetamine “pep pills” went unnoticed; in fact, sensationalist exposés had been common in the media since the barbiturates were first introduced in the 1910s. By the 1950s, as Nicolas Rasmussen has shown, such exposés had motivated a range of efforts to push for stricter controls or even include the medicines in the Harrison Act.104 The repeated failure of these efforts is evidence of pharmaceutical company power, but also of the cultural assumptions and social privileges that protected pharmaceutical white markets at the local level.

Epilogue: The Fall and Rise of White Markets for Pharmaceuticals

When narcotics, sedatives, and stimulants are examined together, the social history of white-market drug abuse revises our understanding of the founding half century of American drug policy. Traditionally the first half of the twentieth century has been narrated in two separate stories. In one, liberal reformers pioneered state regulation of the market through slow and piecemeal protection of consumers from the pharmaceutical industry. In the other, moral reformers developed new state capacity to police and punish socially marginal urban communities already suffering from drug abuse and addiction.

A focus on pharmaceutical white markets tells a very different story: of a divided system of drug control designed to encourage and enable a segregated market for psychoactive substances. This regime established a privilege—maximal freedom of rational choice in a relatively safe drug market “governed at a distance” by nonstate actors like physicians and pharmacists—and linked this privilege both institutionally and culturally to social factors such as economic class and whiteness. Meanwhile a parallel and far more repressive system provided riskier drugs to supposedly irrational poor and often racialized minorities who were policed and punished (and, sometimes, treated for addiction) directly by the state.105

Like other elements of segregated America, pharmaceutical white markets and the dual drug regime that enabled them came under serious challenge in the 1960s and 1970s. During these decades the harsh certainties of the drug war gave way to an ambiguous campaign to treat addiction as an illness rather than to punish it as a crime.106 These changing attitudes stemmed, in part, from a frank recognition of widespread problems of prescription drug abuse among the white middle classes.107 As a result, pharmaceutical regulations became stricter even as drug war policies relaxed in some respects. This is evident in the era's drug law reforms, which added resources into addiction treatment (including methadone maintenance)108 while imposing tough new restrictions on prescription sedatives and stimulants. Under the era's signature law, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, addictive medicines joined heroin and cocaine in the Schedule of Controlled Substances. While pharmaceuticals were generally scheduled in categories with less surveillance and punishment, they belonged to the same regulatory mechanism and were ultimately policed by the same entity, the new Drug Enforcement Administration.

Unlike the FDA, the DEA had authority over all drug market actors. Because possession without a prescription was now a crime, this included white markets' relatively privileged consumers, who were now recognized as potential addicts and thus were no longer presumed to be innocent of desire to use drugs. But conveniently for the ranks of newly discovered white and middle-class addicts, the problematic desire to use drugs was now at least potentially recognized as an illness. So white-market consumers were spared the kind of demonization earlier visited upon “junkies.” Instead, the new drug regime's real firepower was trained on powerful social institutions and structural actors such as physicians and the pharmaceutical industry. The DEA surveilled and prosecuted physician prescribers, aided by newly cooperative state-level controlled substances boards. The agency also enjoyed authority over the pharmaceutical industry that a century of reformers could only have dreamed of, including the power to limit production of the most restricted drugs to “medical need” as ascertained by DEA-approved experts.109

As with earlier periods, drug war and pharmaceutical historians narrate these developments very differently. For pharmaceutical historians, this was a rare moment when the regulatory state was given the power it needed to protect consumers by reining in the drug industry. Drug war historians, meanwhile, see it as a moment when the runaway powers of a repressive state were curtailed and addiction was partially and ambivalently “medicalized.” When told together, however, these narratives take on a different and arguably more radical cast. Drug law reforms look more like civil rights acts, fair housing laws, and other efforts to undo the state's harmful investment in segregating consumer markets. There are obvious differences, of course, since prescription drugs, unlike homes or lunch counters, are dangerous or at least highly problematic goods. Thus reformers did not necessarily focus on welcoming new consumers into white markets; instead, they worked to rein in markets that had grown too large under the protection of racial privilege.

The new regimes transformations were more politically complex than there is room to explore here, and it is important not to overstate their impact on long-standing inequalities in American drug policy. For present purposes, however, the regime's most significant success was notable: it helped bring about the nation's first broad-based contraction of pharmaceutical white markets. Amphetamine sales plummeted tenfold from 4 billion pills in 1969 to 400 million in 1972.110 Barbiturates (and their successors, the tranquilizers) saw similar sharp declines from nearly 150 million prescriptions in 1973 to half that number a decade later (see Figure 1).111 Prescription-drug-related emergency room visits and overdose deaths dropped steeply as well, although figures for “street” drug use (where reforms were less thorough) showed no such clear pattern.112

Not everyone was happy about these changes. After all, white, “respectable” Americans had enjoyed relatively unimpeded access to powerful yet relatively safe, relatively inexpensive, and informally policed sedatives, stimulants, and, to a lesser extent, narcotics since the late nineteenth century. And, as the complaint letters that began this article show, at least some white-market consumers understood the new constraints as yet another entitlement lost to intrusive government in the civil rights era.

The new regime did not necessarily satisfy liberals and civil rights activists either. Medicalized approaches were sold as crime-prevention strategies, thus reinforcing the social stereotypes about addiction that they supposedly set out to challenge. Many also favored get-tough approaches that oftentimes differed only in name from punishment.113 Meanwhile, despite the overall decline in pharmaceutical white markets, they did not disappear entirely. Some pharmaceutical companies and some physicians actively sought and often found ways around legal constraints, and those with privileged access to them continued to reap more than their share of benefits, and harms, from psychoactive drugs—and continued to portray themselves, with some success, as fundamentally different from “street” addicts using nonpharmaceutical drugs.114

The persistence of these distinctions left the regime's more radical elements vulnerable to the broader backlash against civil rights politics that was already stirring in the United States. Already in 1973, for example, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller's “harshest in the nation” drug laws encouraged law-and-order politicians to adopt a new and even intensified drug war as part of the nation's resurgent political conservativism.115 This process culminated in the mid-1980s scare over “crack” cocaine, whose punitive legislation helped to produce an era of mass incarceration so racially unequal that some have taken to calling it the “New Jim Crow.”116 Meanwhile, deregulation of the pharmaceutical industry in the 1980s allowed the introduction of a new generation of blockbuster sedatives, stimulants, and narcotics, all hailed as technological triumphs over addiction. Barbiturates and early tranquilizers gave way to Xanax (for panic) or Ambien (for sleep); Benzedrine and Dexamyl gave way to Ritalin, Adderall, and other stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and depression; even narcotics got a new lease on life as morphine and Demerol gave way to Talwin and eventually OxyContin, and pain management emerged as a new medical specialty.117

The end result looked familiar. Once again there was a sharp and massive rise in drug use, powerfully divided between relatively lightly controlled medicines used predominantly by whites, and punitively punished drugs trafficked predominantly in urban, nonwhite neighborhoods.118 These shifts, however, should not be seen as examples of predatory pharmaceutical companies outmaneuvering physicians and regulators and fooling an innocent public. Instead, they represent the maintenance by new means of a long-standing facet of American medical practice: the mass provision of sedatives, stimulants, and narcotics under the racially protected aegis of “therapy” but still inevitably producing a new wave of addiction and harm. Pharmaceutical companies have certainly been key actors in enabling this situation, but their efforts succeeded at least in part because of the social entitlement that encouraged white, “respectable” Americans to see access to psychoactive pharmaceuticals as a basic right, and that obscured the nature of the problems caused by this social entitlement.

It is no accident that eras of drug and pharmaceutical reform have so often paralleled each other, nor is it an accident that they map so well onto civil rights history, as the timeline in Figure 2 shows. All belong very much to the same story. From this perspective, America is not an antidrug nation, nor is it a nation that has been duped into taking drugs by Big Pharma. Instead, American drug policies have ambivalently allowed and even encouraged mass use of sedatives, stimulants, and narcotics for over a century. These policies have been ostensibly oriented around the divide between medical and nonmedical use, but they have been as much if not more organized around social divisions of class and, increasingly, race.

Figure 2. Timeline of drug and pharmaceutical histories.

The resulting system has clearly produced real and serious harm. On the one hand, as scholars of mass incarceration and others have shown, drug wars have brought destructive punishment to some of the nation's most vulnerable communities under the assumption that all use of street drugs is by definition abuse. Meanwhile, as a host of critics have explained, pharmaceutical regulations have allowed easy access to dangerous and addictive drugs for too long, in part because of a determination to see all use of medicines by respectable white middle classes as therapeutic. These two problems have not been unrelated: weak pharmaceutical regulations have allowed white markets to expand so dramatically that drug wars are launched to rein them in.

Barring an unprecedented decision to stop the mass use of sedatives, stimulants, and narcotics, the best way to restrain this unhappy cycle would be to back away from the oversimplified and deeply racialized dichotomy between therapy and abuse, and, more generally, from questions of moral condemnation or approval, and instead focus on safe versus unsafe drug use—to acknowledge and manage the risks of a historically common but admittedly dangerous activity. Ironically, perhaps, the best drug policy tools history has to offer along these lines can be found in the Nixon administration's approach to psychoactive pharmaceuticals—policies less noticed than the administration's much louder declaration of a “war on drugs.” These policies accepted that there would be widespread use of sedatives, stimulants, and narcotics, but also took the risks of those drugs seriously. They minimized those risks not by demonizing and punishing drug users (the “drug war” method) and not by assuming that education and other voluntary measures would help rational, innocent patients choose not to abuse drugs (the “white-market” method). Instead, they (mostly) followed a third option: strictly regulating structural market players such as manufacturers, doctors, and druggists, while expanding treatment options for drug users. This can be seen as a form of what addiction activists call “harm reduction,” and it worked.119 After a century of failed or even harmful drug war policies, success should not be taken lightly. It is time to rethink the historically constructed categories that have prevented these tools from being more widely, and more equitably, applied.

David Herzberg is associate professor of history at the University at Buffalo (SUNY). His work on pharmaceuticals and modern consumer cultures has appeared in American Quarterly, in the American Journal of Public Health, and in a book, Happy Pills in America: From Miltown to Prozac (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009). He is currently writing a book-length history of pharmaceuticals and addiction in the long twentieth century.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank David Courtwright, Carl Nightengale, Susan Cahn, Mike Rembis, Nan Enstad, Joseph Gabriel, Nicolas Rasmussen, and Jeremy Greene for generosity with their time and expertise; the staff of the National Archives II, the Wisconsin Historical Society, the Massachusetts State Archives, and the University at Buffalo's Inter-Library Loan Office for invaluable assistance; for funding, the University at Buffalo's Humanities Institute, UB's Baldy Center for Law & Social Policy, and the American Institute for the History of Pharmacy; and the article's anonymous reviewers for their insights and guidance. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health under award number 5G13LM012050. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (or of the scholars and friends thanked earlier in this paragraph).

References

- 1.Roma Valenzuela to Congressman John Rhodes, July 25, 1973, folder 228 (511.09-5121 Vibramycin), box 4866, General Subject Files, 1938-1974, Division of General Service, Records of the Food and Drug Administration, Record Group 88, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD (hereafter FDA Papers).

- 2.Mrs. Steinle to Henry E. Simmons, M.D., Director, Bureau of Drugs, FDA, July 30, 1973, FDA Papers (n. 1).

- 3.Edwin Anderson to Edward Melton, Consumer Safety Officer, Office of Legislative Services, FDA, September 1, 1973, FDA Papers (n. 1).

- 4.See, e.g., Kohler-Hausman Julilly. ‘The Attila the Hun Law’: New York's Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Making of a Punitive State. J Soc Hist. 2010;44:71–95. doi: 10.1353/jsh.2010.0039.; Lassiter Matthew. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 2007.

- 5.Jerry Flynn, “August 31, 1977, 9:30 A.M. Interview with Dr. Theiler,” 2, “Theiler, Alvin,” Wisconsin Medical Examining Board: Investigations, Series 1616, Wisconsin Historical Society, Library-Archives Division, Madison, (hereafter “MEB Investigations”).

- 6.The literature on American drug wars is far too large to cite fully here, but for works addressing cultural stigmatization and punitive policing, see Musto David. The American Disease: Origins of Narcotics Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. 1973; repr.Courtwright David. Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2001. 1982; repr.Reinarman Craig, Levine Harry., editors. Crack in America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1997. Spillane Joseph. Cocaine: From Medical Marvel to Modern Menace in the United States, 1884–1920. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999. Campbell Nancy. Regulating Maternal Instinct: Governing Mentalities of Late Twentieth-Century U.S. Illicit Drug Policy. Signs. 1999 Summer;24(4):895–924.Campbell Nancy. Using Women: Gender, Drug Policy, and Social Justice. New York: Routledge; 2000. Jean Acker Caroline. Creating the American Junkie: Addiction Research in the Classic Era of Narcotic Control. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. Tracy Sarah, Jean Acker Caroline., editors. Altering American Consciousness: The History of Alcohol and Drug Use in the United States, 1800–2000. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press; 2005. Marez Curtis, Wars Drug. The Political Economy of Narcotics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2004. Hickman Timothy. The Secret Leprosy of Modern Days: Narcotic Addiction and Cultural Crisis in the United States, 1870–1920. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press; 2007. Ahmad Diana. The Opium Debate and Chinese Exclusion Laws in the Nineteenth-Century American West. Reno: University of Nevada Press; 2011. Schneider Eric. Smack: Heroin and the American City. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2011. Roberts Samuel K. ‘Rehabilitation’ as Boundary Object: (Bio)medicalization, Local Activism, and Narcotics Addiction Policy in New York City, 1951-1962. Soc Hist Alcohol Drugs. 2012 Summer;26(2):147–69.Alexander Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press; 2012. The Drug Wars in America, 1940–1973. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2013. One important exception is Kathleen Frydl., a sweeping policy history that addresses both “street” drugs and sedative/stimulant pharmaceuticals in an analysis of how American drug wars expanded the nature and reach of federal power.