SUMMARY

Interleukin 2 (IL-2) promotes Foxp3+-regulatory T (Treg) cell responses, but inhibits T follicular helper (TFH) cell development. However, it is not clear how IL-2 affects T follicular regulatory (TFR) cells, a cell type with properties of both Treg and TFH cells. Using an influenza infection model, we demonstrated that high IL-2 concentrations at the peak of the infection prevented TFR cell development by a Blimp-1–dependent mechanism. However, once the immune response resolved, some Treg cells down-regulated CD25, up-regulated Bcl-6 and differentiated into TFR cells, which then migrated into the B cell follicles to prevent the expansion of self-reactive B cell clones. Thus, unlike its effects on conventional Treg cells, IL-2 inhibits TFR cell responses.

INTRODUCTION

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) is essential for the development and maintenance of Foxp3+CD4+ T regulatory (Treg) cells, which prevent autoimmune disease development1. The principal mechanism by which IL-2 promotes Treg cell development is by triggering STAT5 activation, which binds to the Foxp3 locus and promotes Foxp3 expression2–4. IL-2 signaling is also required to maintain the competitive fitness of Treg cells in secondary lymphoid organs5,6 and for reinforcing their suppressive activity7,8. Hence, mice lacking IL-2 or IL-2Rα (CD25) fail to maintain peripheral tolerance and develop autoimmune disease9.

Treg cells express high amounts of CD25, the α chain of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor, allowing them to effectively compete with other cells for available IL-210–12. Indeed, IL-2-consumption by Treg cells is one of the main mechanisms by which they prevent effector-T cell (Teff) responses13. Conversely, IL-2 consumption by Treg cells facilitates CD4+ T follicular helper (TFH) cell development10, since IL-2 signaling inhibits TFH cell differentiation14–16. Interestingly, some activated Treg cells down-regulate CD25, and do not require IL-2 for their homeostatic maintenance17. Instead, their survival is dependent on ICOS–ICOS-L interactions17. Similarly, antigen-experienced Treg cells in the skin18 and in aged mice19 express less CD25, and depend on IL-7 and IL-15 rather than IL-2 for their maintenance, thus suggesting that IL-2 might be dispensable for the homeostasis of some Treg cell subsets.

Interestingly, some Foxp3-expressing Treg cells up-regulate Bcl-6 and CXCR5, molecules that are normally expressed by TFH cells20,21. These Foxp3+Bcl-6+CXCR5+CD4+ cells are known as T follicular regulatory (TFR) cells20–22, which home to B cell follicles where they suppress B cell responses20–25. The ability of TFR cells to co-express Foxp3 and Bcl-6 is somewhat surprising, as IL-2 signaling is important for Foxp3 expression, but inhibits Bcl-614,15,26. Thus, it is unclear how IL-2 might be involved in the differentiation or maintenance of TFR cells.

In this study, we investigated the role of IL-2 in TFR cell responses to influenza. We demonstrated that high concentrations of IL-2 at the peak of the infection promoted the expression of Blimp-1 in Treg cells, which suppressed Bcl-6 expression and thereby precluded TFR cell development. As a consequence, TFR cells failed to accumulate at the peak of the influenza infection. However, once the virus was eliminated and the IL-2 concentrations declined, some CD25hi Treg cells down-regulated CD25, up-regulated Bcl-6 and differentiated into TFR cells, which migrated into the B cell follicles to prevent the accumulation of self-reactive B cell clones. Collectively, our data demonstrate that IL-2 signaling differentially controls conventional Treg and TFR cell responses to influenza virus, and reveal an important role for TFR cells in maintaining B-cell tolerance after influenza infection.

RESULTS

Kinetics of TFR cell expansion upon influenza infection

To evaluate whether TFR cells could be detected after influenza infection, C57BL/6 (B6) mice were intranasally (i.n) infected with influenza A/PR8/34 (PR8) and Foxp3+CD4+ T cells were characterized in the lung-draining mediastinal lymph node (mLN) 30 days later (Fig. 1a–c). Foxp3+CD69loCD4+ cells expressed low amounts of Bcl-6 and CXCR5 (Fig. 1a). In contrast, Foxp3+CD69hiCD4+ T cells could be separated into Bcl-6loCXCR5lo cells, which were PD-1lo and GL-7lo, and Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi cells, which were PD-1hi and GL-7 hi (Fig. 1a–c). Thus, we designated the Bcl-6loCXCR5loFoxp3+CD4+ T cells as conventional Treg cells and Bcl-6hiCXCR5hiFoxp3+CD4+ T cells as TFR cells. TFR cell development requires SAP-mediated interaction with B cells21. As such, the frequency and number of Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR cells were decreased in SAP-deficient (B6.Sh2d1a−/−) mice relative to B6 mice (Fig. 1d,e). Finally, to show that Foxp3+ cells homed to GCs following influenza infection, we determined the placement of Foxp3+ cells relative to B cell follicles and GCs in sections of mLNs obtained from day 30 influenza-infected mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a). As expected, we identified CD4+Foxp3+ cells within the B cell follicles, the interfollicular area and inside the GCs (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). These results indicated that bona fide TFR cells did develop following influenza virus infection.

Figure 1. Kinetic of the TFR cell response to influenza.

(A–C) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed on day 30 after infection by flow cytometry. (A) Expression of Bcl-6 and CXCR5 in FoxP3+CD69hi and FoxP3+CD69lo CD4+ T cells. Expression of PD-1 (B) and GL-7 (C) on Bcl-6loCXCR5lo and Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi FoxP3+CD69hi CD4+ T cells. Data are representative of five independent experiments (3–5 mice per experiment). (D–E) B6 and B6.Sh2d1a−/− mice were infected with PR8 and the frequency (D) and number (E) of FoxP3+CD69hiCD4+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR cell phenotype were evaluated in the mLN on day 30 after infection. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± SD of 3–5 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (F–I) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed by flow cytometry at the indicated time-points. Frequency (F) and number (G) of Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR cells. Representative plots were gated on FoxP3+CD69hiCD19− CD4+ T cells. (H) Number of FoxP3+CD69hi Treg cells with a Bcl-6loCXCR5lo phenotype. Frequency (I) and number (J) of CD19+CD138–PNAhiCD95hi GC B cells. Frequency (K) and number (L) of Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFH cells. Representative plots were gated on CD4+FoxP3−CD19−T cells. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4–5 mice/time point). Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We next infected B6 mice with influenza and enumerated TFR cells and conventional Treg cells in the mLN at different times after infection (Fig. 1f–h). Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR cells were barely detectable at the peak of the infection (day 7 to 15), but largely accumulated during the late phase of the primary response (day 30 to 60) (Fig. 1f,g). In contrast, conventional Treg cells rapidly expanded between days 3 and 7 (Fig. 1h). Importantly, the paucity of TFR cells at the peak of the infection was not due to a lack of GC B cells, since GC B cells were easily detected at day 10, continued to expand through day 15, and declined thereafter (Fig. 1i,j). We also observed that Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFH cells (Fig. 1k,l) peaked between days 7 and 15 after infection, and subsequently contracted between days 15 and 30. Thus, in contrast to GC cells, TFH cells and conventional Treg cells, TFR cells failed to accumulate at the peak of the infection.

To further confirm this conclusion, we evaluated the presence of Foxp3+ cells within the GCs at days 10 and 30 after infection by immunohistochemistry (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Foxp3+ cells were easily detected in the B cell follicles, interfollicular area and GCs on day 30. By contrast, very few Foxp3+ cells were present within the GCs at day 10, despite being abundant in the T cell area. Collectively, these results indicated that the TFR cells failed to develop during the peak of the influenza infection, but accumulated in the mLN at later time points.

Previous studies have shown that TFR cells develop quickly (days 7–14) upon immunization with soluble antigens20,21,23. To test whether the delayed appearance of TFR cells was unique to influenza, we enumerated TFR cells in B6 mice that were either immunized with influenza hemagglutinin (HA) adsorbed to alum (Supplementary Fig.1 d,e) or infected with LCMV-Armstrong (Supplementary Fig. 1 f,g). In agreement with the published studies, we found that TFR cells were readily detected at day 9 after HA immunization and were maintained for at least 30 days (Supplementary Fig. 1 d,e). By contrast, TFR cells were virtually undetectable at day 9 following LCMV-Armstrong infection, but accumulated in large numbers at day 30 after infection (Supplementary Fig. 1 f,g). Collectively, these results suggested that, whereas TFR cell responses quickly develop following soluble protein immunization, TFR cells fail to differentiate at the peak of acute viral infections.

TFR cells exhibit low expression of CD25

TFR cells depend on Bcl-620–22, whose expression is inhibited by IL-210,14,16. To examine the relationship between TFR cells and IL-2 signaling, we divided the CD69+Foxp3+CD4+ T-cell population into CD25hi and CD25lo cells and analyzed the expression of TFR cell markers in these subpopulations (Fig. 2a,c). We found that CD25loFoxp3+ cells, but not CD25hiFoxp3+ cells, up-regulated TFR markers following infection (Fig. 2a,c). Importantly, although CD25loFoxp3+ cells were present at the peak of the infection (d10), they expressed low amount of CXCR5, Bcl-6 and PD-1 relative to later time points, suggesting that lack of TFR cells at the peak of the infection was not due to a lack of CD25loFoxp3+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Similar results were obtained in LCMV-infected mice or HA-Alum-immunized mice (Supplementary Fig. 2d,e). Thus, unlike conventional Treg cells, which are CD25hi, TFR cells are CD25lo.

Figure 2. TFR cells are CD25lo.

(A–E) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed on day 30 by flow cytometry. (A) Frequency of CD25hi and CD25lo FoxP3+CD69hi CD4+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype. Expression of PD-1 (B) and GL-7 (C) in CD25hi and CD25lo Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi cells. Data are representative of five independent experiments. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4 mice). P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (D) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and STAT5 phosphorylation in CD4+B220−CD25loBcl-6hiCXCR5hi Foxp3+ TFR cells, CD4+B220−CD25hiBcl-6loCXCR5loFoxp3+ conventional Treg cells and CD4+B220−Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi Foxp3− TFH cells was determined by flow cytometry on day 15. Cells were stimulated with 100ng/ml of rIL-2 for 15 minutes before analyzing staining. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4 mice). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (E–F) Conventional Treg cells (CD19−CD4+FoxP3+CD69hiPD-1loCXCR5loCD25hi) and TFR cells (CD19−CD4+FoxP3+CD69hiPD-1hiCXCR5hiCD25lo) were sorted from the mLN of FoxP3–DTR–GFP at day 30 after infection and RNA-seq was performed. (E) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA, Broad Institute) examining differentially expressed genes between Treg cells and TFR cells (adjusted p-value <0.05, Log2fold change greater than or equal to 1. The Normalized Enriched Score (NES) and the number of up-regulated genes for each of the top 10 Hallmark -signaling Pathways resulting from the GSEA analysis are shown. (F) Heatmap displaying the expression of the IL-2–STAT5 Hallmark-signaling pathway genes that are differentially expressed in conventional Treg cells relative to TFR cells. Three replicates for each cell type were obtained from three independent experiments. (G and H) Expression of CD25 (G) and CD122 (H) in Bcl-6loCXCR5lo FoxP3+CD69hi CD4+ T cells, Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR cells and CD44loCD69loFoxP3− CD4+ T cells (naïve). Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=5 mice). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We next evaluated STAT5 phosphorylation in TFR and conventional Treg cells and found that pSTAT5 was reduced in TFR cells compared to conventional Treg cells (Fig. 2d), suggesting that TFR and conventional Treg cells responded differently to IL-2. To confirm this conclusion, we sorted conventional Treg cells (Foxp3+CD69hiPD-1loCXCR5loCD25hi) and TFR cells (Foxp3+CD69hiPD-1hiCXCR5hiCD25lo) from the mLN of day 30 infected B6.Foxp3–DTR–GFP mice and performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to identify hallmark-signaling pathways differentially enriched in these populations (Fig. 2e,f). Approximately 2,000 genes were differentially expressed between conventional Treg and TFR cells (Supplementary Table 1). Importantly, the IL-2–STAT5 signaling pathway had the highest normalized enrichment score (NES=3.54; FDR < 0.001) and contained the largest number of genes up-regulated in Treg cells relative to TFR cells (Fig. 2e). Of the 200 genes in the hallmark IL-2–STAT5 signaling pathway, 72 were significantly downregulated in TFR vs Treg cells (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Tables 2,3). Interestingly, despite their low expression of CD25 (Fig. 2g), TFR cells expressed high amounts of IL-2Rβ (CD122) (Fig. 2h), suggesting that TFR cells may have some remaining capacity to respond to IL-2, particularly when its physiological concentration is sufficiently high27. Altogether, our results indicated that the IL-2–STAT5 signaling pathway was downregulated in TFR cells compare to conventional Treg cells.

CD25+ Treg cells are the precursors of TFR cells

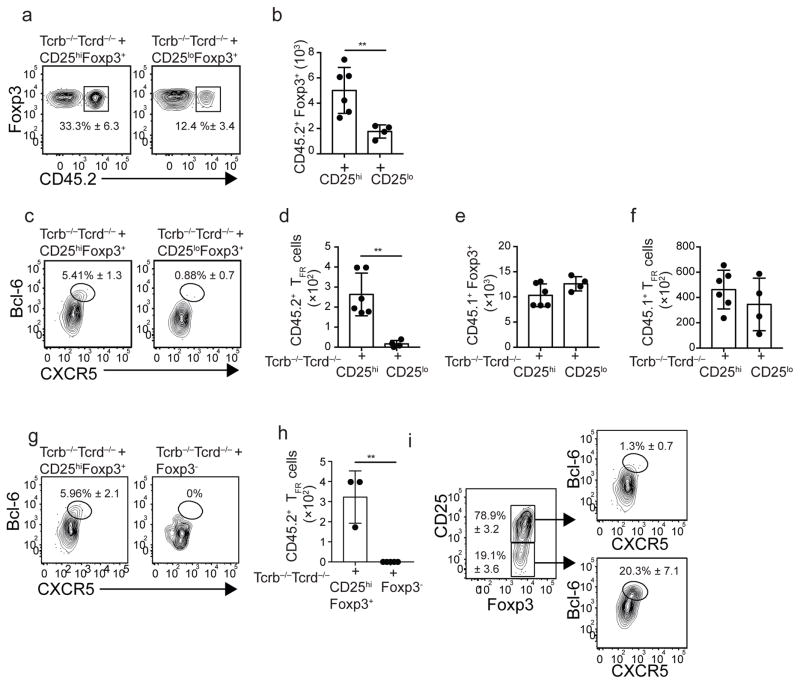

Previous studies showed that TFR cells differentiate from pre-existing Foxp3+ Treg precursors20,21. Given that TFR cells were CD25lo, we used adoptive-transfer experiments to test whether TFR cells were derived from pre-existing CD25hiFoxp3+ or CD25loFoxp3+ T cells. Therefore, we sorted CD25hiFoxp3+ or CD25loFoxp3+ CD4+ T cells from the spleen of naïve B6.Foxp3–DTR–GFP (CD45.2+) mice, which express the diphtheria-toxin receptor and the eGFP genes under the control of the Foxp3 promoter, and adoptively transferred equivalent numbers of these cells into naïve Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− mice, that lack T cells. We also transferred total CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from B6.CD45.1 mice to provide a competent T-cell environment. One day later, mice were infected with influenza and the donor-derived Foxp3+ cells were characterized on day 30. The frequencies and numbers of activated Foxp3+ cells derived from the CD45.2+ donors were increased in recipients of CD25hiFoxp3+ cells compared to recipients of CD25loFoxp3+ cells (Fig. 3a,b). We also found that nearly 6% of the progeny derived from CD25hiFoxp3+ cells up-regulated Bcl-6 and CXCR5, whereas few of the progeny derived from CD25loFoxp3+ cells up-regulated Bcl-6 and CXCR5 (Fig. 3c). As a result, the numbers of CD45.2+ TFR cells were significantly higher in recipients of CD25hiFoxp3+ cells compared to recipients of CD25loFoxp3+ cells (Fig. 3d). Importantly, the number of CD45.1+Foxp3+ cells, and the number of CD45.1+ TFR cells were similar in the two groups (Fig. 3e,f). These data indicated that pre-existing CD25hiFoxp3+ cells, but not pre-existing CD25loFoxp3+ cells, differentiate into TFR cells following influenza infection.

Figure 3. CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells down-regulate CD25 and differentiate into TFR cells.

(A–F) Equivalent numbers of sorted CD25hiFoxP3+ and CD25loFoxP3+ CD4+ T cells obtained from the spleens of naïve CD45.2+ B6-Foxp3-DTR–GFP mice were adoptively transferred into Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− recipient mice. Recipient mice also received purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the spleen of naïve CD45.1+ B6 mice. One day later, recipient mice were infected with influenza and donor-derived CD45.2+ (A–D) and donor-derived CD45.1+ (E–F) CD69+FoxP3+CD4+ T cells were assessed in the mLN on day 30 by flow cytometry. The frequency (A) and number (B) of CD45.2+FoxP3+ cells in recipients receiving CD25hiFoxP3+ and CD25loFoxP3+ cells are shown. Plots were gated on FoxP3+CD69hiCD4+ T cells. The frequency (C) and number (D) of CD45.2+CD69+FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype in recipients receiving CD25hiFoxP3+ and CD25loFoxP3+ cells are shown. (E) The number of donor-derived CD45.1+CD69+FoxP3+CD4+ T cells in recipients receiving CD25hiFoxP3+ and CD25loFoxP3+ cells are shown. (F) The number of donor-derived CD45.1+CD69+FoxP3+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype in recipients receiving CD25hiFoxP3+ and CD25loFoxP3+ cells are shown. Data were pooled from two independent experiments (mean ± SD). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (G–H) Equivalent numbers of sorted CD25hiFoxP3+ and FoxP3− CD4+ T cells obtained from the spleen of naïve CD45.2+ B6-Foxp3-DTR–GFP mice were adoptively transferred into Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− recipient mice. The recipient mice also received purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the spleen of naïve CD45.1+ B6 mice. One day later, the mice were infected with influenza and the donor-derived CD45.2+ CD69+FoxP3+CD4+ T cells were assessed in the mLN on day 30 by flow cytometry. Frequency (G) and number (H) of CD45.2+CD69+FoxP3+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype in recipients of CD25hiFoxP3+ and FoxP3−CD4+ T cells. (I) Frequencies of Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi in CD25hi and CD25lo FoxP3+ cells derived from the CD45.2+CD25hiFoxp3+ donors. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=3–5 mice). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Recent data suggest that TFR cells can also be derived from CD4+Foxp3− precursors28. Therefore, we performed adoptive-transfer experiments to compare the capacity of CD4+Foxp3− and CD25hiFoxp3+ cells to differentiate into TFR cells following infection. Although some CD4+Foxp3− cells up-regulated Foxp3 after infection (data not shown), CD45.2+ TFR cells were only generated from CD25hiFoxp3+ cell precursors (Fig. 3g,h). Collectively, these data indicated that CD25hiFoxp3+ cells are the precursors of TFR cells after influenza infection.

We next tested whether the Foxp3+ cells derived from the CD25hiFoxp3+ donors maintained CD25 expression (Fig. 3i). We found that, although the majority of Foxp3+ progeny derived from the CD25hiFoxp3+ donors were CD25hi, some cells lost expression of CD25 and only the CD25lo cells up-regulated TFR markers (Fig. 3i). Collectively, these results demonstrated that a fraction of the activated CD25+Foxp3+CD4+ T cells down-regulate CD25 and up-regulate Bcl-6, PD-1 and CXCR5 late after infection.

IL-2 signaling precludes TFR cell development

Given that IL-2 signaling inhibits Bcl-6 expression10,14,16, we next tested whether TFR cells could develop in a high-IL-2 environment. To do this, B6 mice were infected with influenza, treated them with either 30,000 units (U) of recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2) or PBS for nine consecutive days starting on day 20 and TFR cells were enumerated in the mLN on day 30. As a control, we analyzed day 10 infected mice. As expected, the frequencies and numbers of TFR cells were higher in day 30 infected mice relative to day 10 infected mice (Fig. 4a,b). By contrast, TFR cells failed to accumulate in rIL-2-treated mice (Fig. 4a,b), suggesting that a high-IL-2 environment prevented the accumulation of TFR cells.

Figure 4. IL-2 inhibits TFR cell differentiation.

(A–B) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and treated daily with 30,000 U of rIL-2 or PBS starting on day 20. Cells from the mLNs were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 30. As a control, cells from the mLNs of day 10 infected mice are also shown. The frequency (A) and number (B) of CD25loFoxP3+ CD4+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=3–5 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (C) Il21-mCherry-Il2-emGFP mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed at the indicated time-points. Representative plots were gated on CD4+ T cells. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=3–5 mice per group). Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D–H) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and treated daily with 500 μg of a mix of anti IL-2 neutralizing Abs (JES6-1A12 + S4B6-1) or control Ab (2A3) starting on day 3 after infection. The frequency (D) and number (E) of Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR cells were calculated on day 10 after infection. Plots were gated on FoxP3+CD69hiCD4+ T cells. (F) Number of Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFH cells. Frequency (G) and number (H) of CD25hiFoxP3+ cells. Plots were gated on CD4+ T cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4–5 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (I–O) B6.FoxP3-DTR–GFP mice were infected with PR8 and CD25hiFoxP3+ CD4+ T cells were sorted from the mLN and spleens at day 7 after infection. Sorted cells were then activated with anti-CD3–CD28 beads in the presence of high (200U/ml) or low (5U/ml) IL-2 concentrations. The expression of CD25 (I), Blimp-1 (J), T-bet (K), Bcl-6 (L) and CXCR5 (M) were assessed 72h later by flow cytometry. The frequency (N) and number (O) of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype are shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments. All values were obtained in triplicate and the data are shown as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001P. values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We next determined the kinetic of IL-2 production during influenza infection using Il21-mCherry-Il2-emGFP dual reporter transgenic mice29 (Fig. 4c). We found that the frequency of IL-2-producing CD4+ T cells peaked at day 10 and declined thereafter (Fig. 4c). We also found that the frequency of IL-2-producing CD4+ T cells was significantly increased in day 10 influenza-infected mice relative to day 10 HA-immunized mice (Supplementary Fig. 3). Given that IL-2 is highly produced at the peak of the infection, we hypothesized that strong IL-2 signals prevented the differentiation of TFR cells at this time. To address this possibility, we infected B6 mice with influenza, treated them daily from day 3 to day 9 with neutralizing IL-2 antibodies (JES6-1A12 + S4B6-1) or control antibody (2A3), and analyzed the Foxp3 compartment in the mLN on day 10 (Fig. 4d,e). As expected, we detected very few TFR cells in control-treated mice. The frequency and number of TFR cells was, however, significantly increased in the anti-IL-2–treated mice (Fig. 4d,e). These results suggested that an elevated concentration of IL-2 at the peak of the infection prevented Foxp3-expressing cells from differentiating into TFR cells. We also found more TFH cells, but less conventional CD25+ Treg cells in the anti-IL-2-treated mice compared to control mice (Fig. 4f–h), which is consistent with previous studies showing that IL-2 signaling is required for CD25hiFoxp3+ Treg cell expansion2,7,30–32, but prevents TFH cell differentiation14–16,26.

To confirm that IL-2 signaling inhibited TFR cell differentiation, we sorted CD25hiFoxp3+ cells from day 7 influenza-infected B6.Foxp3-DTR–GFP mice, activated them in vitro with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 beads in the presence of high (200U/ml) or low (5U/ml) rIL-2 concentrations and assessed the phenotype of Foxp3+ cells three days later (Fig. 4i–o). Foxp3+ cells activated in the presence of high-IL-2 concentrations expressed high levels of CD25, Blimp-1 and T-bet relative to Foxp3+ cells cultured in low-IL-2 conditions (Fig. 4i–k). In contrast, Bcl-6 and CXCR5 were up-regulated in Foxp3+ cells cultured in low-IL-2 concentrations (Fig. 4l,m). As a result, Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi cells differentiated in the low but not high-IL-2 cultures (Fig. 4n,o). Collectively, our data indicated that, while elevated IL-2 signaling at the peak of the infection promoted CD25hi Treg cell responses, it simultaneously prevented Foxp3-expressing cells from up-regulating Bcl-6 and CXCR5 and differentiating into TFR cells.

IL-2 prevents TFR cell responses by promoting Blimp-1

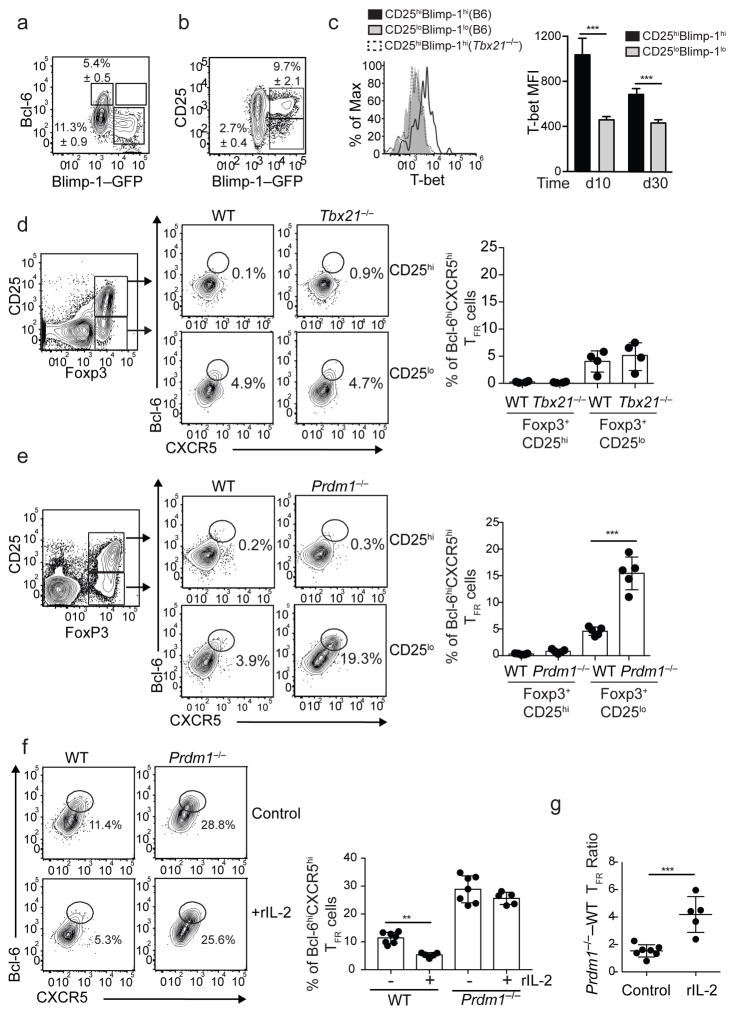

IL-2 inhibits Bcl-6 expression by up-regulating Blimp-114,15 and by favoring the formation of T-bet–Bcl-6 complexes, which mask the Bcl-6 DNA-binding domain and prevent it from binding to its target genes26. Thus, we next assessed the expression of these transcription factors in Foxp3+ cells following influenza infection (Fig. 5a–c). To do this, B6.Blimp-1–YFP reporter mice were infected and the expression of the Blimp-1–YFP reporter was examined in CD69+Foxp3+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5a,b). We found that nearly 12% of these cells were Blimp-1–YFP+ (Fig. 5a). As predicted, Blimp-1–YFP+ cells were Bcl-6lo (Fig. 5a). We also found that although some Blimp-1–YFP+ cells were CD25int/low, the majority of Blimp-1–YFP+ cells expressed high amounts of CD25 (Fig. 5b). We next analyzed T-bet expression and found that it was highly expressed in CD25hiBlimp-1+ cells relative to CD25loBlimp-1− cells (Fig. 5c). Thus, in agreement with previous studies33–35, Treg cells expressed T-bet and Blimp-1 following influenza infection.

Figure 5. IL-2 inhibits TFR cell differentiation by a Blimp-1 mechanism.

(A–B) B6.Blimp-1/YFP reporter mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed on day 30 by flow cytometry. (A) Expression of Bcl-6 and Blimp-1/YFP in FoxP3+CD69hiCD4+ T cells. (B) Expression of CD25 and Blimp-1/YFP in FoxP3+CD69hiCD4+ T cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± S.D of 3–5 mice per group). (C) B6 and Tbx21−/−mice were infected with PR8 and the expression of T-bet in CD25hiBlimphi and CD25loBlimplo FoxP3+CD69hiCD4+ T cells was analyzed at days 10 and 30 by intracellular staining. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean ± S.D of 3–5 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (D) Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− mice were irradiated and reconstituted with a 50:50 mix of BM from CD45.1+ WT and CD45.2+ Tbx21−/− donors. Eight weeks later, reconstituted mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed on day 10. The frequency of CD25loFoxP3+ and CD25hiFoxP3+ cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype was determined in the CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ compartments. Representative plots are shown. Data in the graph are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4 mice). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (E) Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− mice were irradiated and reconstituted with a 50:50 mix of BM from CD45.1+ WT and CD45.2+ Prdm1fl/fx-Lckcre/+ donors. Eight weeks later, reconstituted mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed on day 10. The frequency of CD25loFoxP3+ and CD25hiFoxP3+ cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi phenotype were calculated in the CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ compartments. Representative plots are shown. Data in the graph are shown as the mean ± SD (n=5 mice). Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (F–G) WT-Prdm1fl/fl-Lckcre/+ chimeric mice were infected with PR8 and treated daily with 30,000 U of rIL-2 or PBS (control) starting 20 days after infection. Cells from the mLNs were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 30. (F) Frequency of CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ CD25loFoxP3+ CD4+ T cells with a Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR-cell phenotype. Data in the graph are shown as the mean ± SD (n=5–7 mice/group). Representative plots are shown. (G) Ratio of Prdm1−/− to WT TFR cell was calculated in control and rIL-2-treated mice. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=5–7 mice/group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To investigate the role of these transcription factors in TFR cell development, we made mixed-bone marrow (BM) chimeras in which irradiated Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− recipient mice were reconstituted with a 50:50 mixture of BM obtained from CD45.1+ wild-type and CD45.2+ Tbx21−/− (T-bet-deficient) B6 donor mice. Two months later, chimeras were infected with influenza and the frequency of TFR cells derived from each donor was determined on day 10. As expected, we failed to detect Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi cells within the CD25hiFoxp3+ compartment of either donor (Fig. 5d). Although we did observe approximately 5% Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi cells in the CD25loFoxp3+ compartment, there was no difference between the wild-type and Tbx21−/− donor cells (Fig. 5d). These results suggested that T-bet did not prevent TFR cell differentiation at the peak of the infection.

To address a potential role for Blimp-1 in preventing TFR differentiation, we generated mixed-BM chimeras using wild-type (CD45.1+) and Prdm1fl/fl-Lck-cre/+ (CD45.2+) donors (WT–Prdm1−/− chimeras). After reconstitution, chimeras were infected with PR8 and analyzed at day 10. As expected, very few wild-type CD25loFoxp3+ cells expressed TFR markers at day 10 post-infection. However, 20% of the Prdm1−/−CD25loFoxp3+ cells were TFR cells (Fig. 5e). These results suggested that Blimp-1 prevented the development of TFR cells at the peak of the influenza infection.

Finally, we examined whether IL-2 prevents TFR cell differentiation by a Blimp-1-dependent mechanism. Thus, WT–Prdm1−/− chimeras were infected with influenza, treated daily with rIL-2 or control PBS starting at day 20, and the TFR cell response was assessed within the wild-type and Prdm1−/− compartments on day 30 after infection (Fig. 5f,g). Similar to our prior experiment, we found more CD25loFoxp3+ cells with a TFR cell phenotype in the Prdm1−/− compartment relative to the wild-type compartment in the PBS-treated mice (Fig. 5f). We also found diminished frequencies of TFR cells in the wild-type compartment of the rIL-2 treated mice relative to PBS-treated mice (Fig. 5f). However, we observed similar frequencies of Prdm1−/− TFR cells in both PBS control and IL-2-treated mice (Fig. 5f). As a consequence, the ratio of Prdm1−/− to wild-type TFR cells was increased in the rIL-2-treated mice compared to PBS control counterparts (Fig. 5g). These results indicated that high-IL-2 signaling directly prevented TFR cell differentiation by an intrinsic IL-2/Blimp-1-dependent mechanism.

TFR cells maintain B-cell tolerance after infection

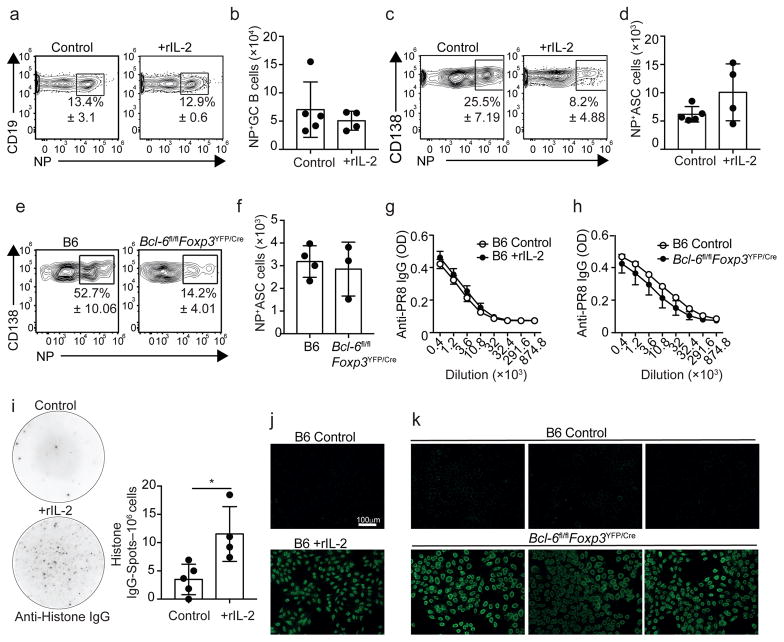

We next used three independent approaches to test the effect of TFR cells on the B cell response to influenza. First, we crossed Bcl-6fl/fl mice36 to Foxp3YFP/Cre mice37 to generate Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice, in which the zinc finger-domains of Bcl-6 are conditionally deleted in Foxp3–expressing T cells36. Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice were infected with influenza and analyzed them on day 30. As expected, the number of TFR cells was reduced in Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice compared to control mice (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, TFH cells normally accumulated in Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice (Fig. 6c,d). Similar results were obtained when we used fluorochrome-labeled MHC Class II tetramers to identify influenza nucleoprotein (NP)-specific TFH cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). We also found GC B cells normally accumulated in control and Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice (Fig. 6e,f). Importantly, however, the frequency and number of CD138+ antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) were increased in Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice relative to control mice (Fig. 6g,h). These results suggested that lack of TFR cells did not change TFH cell or the GC B-cell responses, but promoted the accumulation of CD138+ ASCs.

Figure 6. Abnormal expansion of CD138+ ASCs in the absence of TFR cells.

(A–H) B6 and Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice were infected with PR8 and cells from the mLN were analyzed by flow cytometry at day 30. Frequency (A) and number (B) of PD-1hiCXCR5hi TFR cells. Representative plots were gated on FoxP3+CD69hiCD25loCD19− CD4+ T cells. Frequency (C) and number (D) of PD-1hiCXCR5hi TFH cells. Representative plots were gated on FoxP3−CD19− CD4+ T cells. Frequency (E) and number (F) of CD19+CD138–GL-7+CD38loCD95hi GC B cells. Frequency (G) and number (H) of CD138+ ASCs. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=3–5 mice/group). Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To confirm this observation, we generated BM chimeras in which TFR cells were selectively depleted after diphtheria toxin (DT) administration (Fig. 7a–f). Thus, we reconstituted irradiated Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− recipient mice with a 50:50 mix of Cxcr5−/−and Foxp3-DTR BM (Foxp3-Cxcr5−/− chimeras), or wild-type BM and Foxp3-DTR BM (Foxp3-WT chimeras). Because TFR cells cannot be produced from Cxcr5−/− precursors20, all the TFR cells in the influenza-infected Foxp3-Cxcr5−/− chimeras developed from the Foxp3-DTR donors (Fig. 7a). In contrast, TFR cells in the Foxp3-WT chimeras developed equally from the WT and Foxp3-DTR donors (Fig. 7a). As a consequence, TFR cells were depleted following DT administration in the Foxp3-Cxcr5−/− but not in the Foxp3-WT influenza-infected chimeras (Fig. 7b,c). The Treg cell response was, however, similar in the two groups (Fig. 7d). Therefore, we infected the chimeric mice with influenza, treated them with DT every four days starting on day 15 and enumerated TFH cells, GC B cells and CD138+ ASCs on day 50 in the mLN. We found similar frequencies and numbers of TFH cells and GC B cells (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d) in the DT-treated Foxp3-Cxcr5−/− and Foxp3-WT chimeras. However, CD138+ASCs accumulated to a greater frequency in Foxp3-Cxcr5−/− chimeras compared to Foxp3-WT controls (Fig. 7e,f). Importantly, no differences were detected between PBS-treated Foxp3-Cxcr5−/−and Foxp3-WT chimeras (Supplementary Fig. 5e). These findings indicated that lack of TFR cells promotes the expansion of CD138+ASCs.

Figure 7. CD138+ ASCs accumulate in TFR cell depleted mice.

(A–F) Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− mice were irradiated and reconstituted with a 50:50 mix of BM from CD45.1+ FoxP3-DTR and CD45.2+ B6 donors (FoxP3-WT) or from CD45.1+ FoxP3-DTR and CD45.2+ Cxcr5−/−donors (FoxP3-Cxcr5−/−). (A) Reconstituted FoxP3-WT and FoxP3-Cxcr5−/−chimeras were infected with PR8 and the frequency of CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ cells within the FoxP3+CD69hiCD25lo TFR cell population was calculated on day 50. (B–F) Reconstituted FoxP3-WT and FoxP3- Cxcr5−/− chimeras were infected with PR8, treated with DT every four days starting 20 days after infection, and cells from the mLN were analyzed on day 50. Frequency (B) and number (C) of Bcl-6hiCXCR5hi TFR cells. Representative plots were gated on FoxP3+CD25loCD19− CD4+ T cells. (D) Number of conventional CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells. Frequency (E) and number (F) of CD138+ ASCs. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4–5 mice/group). Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (G–H) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and treated daily with 15,000 U of rIL-2 or PBS starting on day 20. Cells from the mLNs were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 30. Frequency (G) and number (H) of CD138+ ASCs. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4–5 mice/group). Data are representative of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To confirm our observations, we treated influenza-infected B6 mice daily with 15,000U of rIL-2 starting on day 20 to deplete TFR cells, and evaluated the - cell response in the mLN on day 30. TFR cells were significantly depleted in rIL-2-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 5f). In contrast, rIL-2 treatment did not affect the accumulation of total or NP-specific TFH cells at this time and dosage (Supplementary Fig. 5g–j). Similarly, the GC B cell response was similar in PBS and rIL-2 treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 5k,l). In contrast, the frequencies and numbers of CD138+ASCs were increased in rIL-2-treated mice (Fig. 7g,h). Collectively, our data indicated that absence of TFR cells late after infection promoted the expansion of CD138+ASCs.

Lack of TFR cell promotes the outgrowth of self-reactive B cell clones following immunization with T-dependent antigens21. To characterize the role of TFR cells in controlling the influenza-specific B-cell response, we used fluorochrome-labeled recombinant NP-tetramers10,16 to identify NP-specific B cells in IL-2-treated and Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice (Fig. 8a–h). The frequencies and numbers of NP-specific GC B cells were similar in control and rIL-2 treated mice (Fig. 8a,b). In contrast, while 30% of the CD138+ ASCs were NP-specific in control mice, only 8% of the CD138+ ASCs were NP-specific in the rIL-2-treated mice (Fig. 8c). As a consequence, the number of NP-specific CD138+ ASCs was similar in control and rIL-2 treated mice (Fig. 8d). Similar results were obtained when comparing Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre and control counterparts (Fig. 8e,f). Finally, the titers of influenza-specific serum IgG were similar in PBS and rIL-2-treated mice (Fig. 8g), or when we compared the serum from Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre and control mice (Fig. 8h). These results suggested that a lack of TFR cells did not significantly affect the influenza-specific B-cell response, but instead promoted the accumulation of non-influenza-specific CD138+ ASCs.

Figure 8. TFR cells prevent the development of self-reactive ASC responses after infection.

(A–D) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and treated daily with 15,000 U of rIL-2 or PBS starting on day 20. Cells from the mLN were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 30. Frequency (A) and number (B) of CD19+CD138–GL-7+CD38loCD95hi GC B cells that were NP-specific. Frequency (C) and number (D) of CD138+ ASCs that were influenza-NP specific. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=4–5 mice/group). Data are representative of four independent experiments. (E–F) B6 and Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice were infected with PR8 and CD138+ ASCs from the mLN were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 30. Frequency (E) and number (F) of CD138+ ASCs that were NP-specific. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=3–4 mice/group). Data are representative of three independent experiments. (G) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and treated daily with 15,000 U of rIL-2 or PBS starting on day 20. Serum was obtained on day 30 and PR8-specific IgG Abs were measured by ELISA. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± SD of 5 mice per group). (H) B6 and Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice were infected with PR8. Serum from was obtained on day 30 and PR8-specific IgG Abs were measured by ELISA. (I) B6 mice were infected with PR8 and treated daily with 15,000 U of rIL-2 or PBS starting 20 days after infection. Histone-specific IgG-secreting cells in the mLN were enumerated by ELISPOT on day 30. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean ± SD of 4–5 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All P values were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (J) The presence of ANAs in the serum from day 30 influenza-infected control and IL-2-treated mice was determined by fluorescence microscopy using HEp-2 slides. Images are representative of two independent experiments (n=4–5 mice/group). (K) ANAs in the serum from day 30 influenza-infected B6 and Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice. Images are representative of three independent experiments (n=4–5 mice/group).

We next hypothesized that these ASCs represented the differentiated daughter cells of self-reactive B cells that are known to be generated in the GCs during infections38. To test this possibility, we first enumerated histone-specific, IgG-secreting cells by ELISPOT in the mLNs of day 30-infected PBS and rIL-2-treated mice. As expected, we found very few histone-specific ASCc in the mLN of PBS-treated mice (Fig. 8i). In contrast, the frequency of anti-histone, IgG ASCs was increased in rIL-2-treated mice, suggesting that lack of TFR cells resulted in the development of anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) responses (Fig. 8i). Thus, we evaluated the serum samples for ANA reactivity. As expected, PBS-treated control mice lacked ANAs, whereas IL-2-treated mice were ANA positive (Fig. 8j). Finally, we evaluated the presence of ANAs in the serum of Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice. We found that, while the sera from B6 infected mice (Fig. 8k) or naïve Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice (Supplementary Fig. 6) were negative for ANA staining, the sera obtained from day 30-infected Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice were positive (Fig. 8k). Therefore, our data indicated that TFR cells prevented the expansion of self-reactive ASCs after influenza infection.

DISCUSSION

We show here that TFR cells are characterized by low expression of CD25 and that IL-2 signaling inhibits, rather than promotes, the development of TFR cells. Correspondently, TFR cells fail to accumulate at the peak of the influenza infection, a time during which IL-2 is highly produced. However, after IL-2 withdrawal, some Foxp3+ cells down-regulate CD25, up-regulate Bcl-6, express CXCR5 and differentiate into TFR cells, which migrate into the B-cell follicles to prevent self-reactive B-cell responses. Thus, unlike conventional Treg cells, high-IL-2 signaling precludes TFR cell development. Importantly, IL-2 consumption by CD25+ Treg cells is required for the initial development of virus-specific TFH cells10. Thus, IL-2-consumption acts as a rheostat that, while facilitating virus-specific TFH cell responses, it selectively prevents TFR cell development at the peak of the infection.

TFR cells prevented self-reactive ASCs, but had no significant effect on the influenza-specific B-cell response, suggesting that TFR cells may be self-specific rather than influenza-specific. This idea is consistent with data showing that the TCR repertoire of TFR cells is skewed towards self-antigens39, and so is the TCR repertoire of thymic-Treg cells40,41, which we show here are the likely precursors of TFR cells after influenza infection. However, TFR cells prevent antigen-specific B-cell responses following immunization with soluble antigens, suggesting that antigen-specific TFR cells can develop under some circumstances 20,21,23,28. In this regard, a recent study suggests that a fraction of the TFR cells differentiate from naïve T-cells precursors following immunization and are specific for the immunizing Ag28. Thus, depending on the specific nature of the immune response, TFR cells can prevent foreign and self-reactive B-cell responses based on their origin and TCR-specificity. In any case, the capacity of TFR cells to prevent influenza-specific effector B responses is overcome in the context of influenza infection. Indeed, influenza-NP is normally complexed with viral-RNA42, which targets it to the intracellular TLR7 compartment following BCR stimulation43. Thus, it is possible that co-ligation of the BCR and pathogen-recognition-receptors in virus-specific B cells synergize to overcome TFR-mediated suppression during influenza infection.

We found that Blimp-1, but not T-bet, suppresses TFR cell development. However, we failed to detect Bcl-6 up-regulation in CD25hi Treg cells even in Blimp-1-deficient cells, suggesting that Bcl-6 expression in CD25hi cells is prevented by additional Blimp-1-independent mechanisms. Given that STAT5 binds to the Bcl-6 promoter and directly represses Bcl-6 expression in response to high-IL-2 signaling26,44–46, it is likely that strong IL-2 signaling through CD25 prevents Bcl-6 expression by a direct STAT5-dependent mechanism.

Our data showing that IL-2 prevents TFR cell responses are in conflict with the notion that IL-2–STAT5 signaling is required for maintaining Foxp3 expression1. However, TFR cells express high amounts of CD122. Thus, although insufficient for inducing sustained Blimp-1 expression in low-IL-2 environments, basal IL-2–STAT5 signaling through the intermediate-affinity IL-2R may be sufficient to prevent Foxp3 down-regulation in TFR cells. Alternatively, TFR cell homeostasis may be partially independent of IL-2, but may require signals from other common–γ chain cytokines and costimulatory molecules, such as IL-7, IL-15 or ICOS which can contribute towards the maintenance of Foxp3-expressing cells in the absence of IL-218,19,47,48. In any case, it is likely that conventional CD25+ Treg and TFR cells use different cellular and molecular pathways for their homeostatic maintenance.

In summary, our data demonstrate that IL-2 signaling temporarily inhibits TFR cell responses during influenza infection. However, once the immune response is resolved, TFR cells differentiate and home to B cell follicles, where are required for maintaining B cell tolerance after infection. Thus, the same mechanism that promotes conventional Treg cell responses, namely IL-2 signaling, also prevents TFR cell formation. Collectively, our data provide a new perspective into how IL-2 dynamically regulates Treg cell homeostasis and function along the course of a relevant pathogen infection.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6), B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (B6.CD45.1), B6.129S6-Tbx21tm1Glm/J, (B6. Tbx21−/−) B6.129P2-Tcrβtm1MomTcrδtm1Mom (Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/−), B6.129S6-Sh2d1atm1Pls/J (Sh2d1a−/−), B6.129-Prdm1tm1Clme/J (Prdm1fl/fl and B6.Cg-Tg(Lck-cre)3779Nik/J, B6.129S(FVB)-Bcl-6tm1.1Dent/J (Bcl-6fl/fl, B6.129(Cg)-Foxp3tm4(YFP/icre)Ayr/J (Foxp3YFP-/Cre), B6.129S2(Cg)-Cxcr5tm1Lipp/J (Cxcr5−/−) were originally obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Il21-mCherry-Il2-emGFP dual-reporter transgenic mice were obtained from W. J. Leonard (NHLBI). Blimp-1 reporter mice were obtained from E. Meffre (Yale University). B6.129S6-Foxp3tm1DTR (Foxp3–DTR–GFP) mice were originally obtained from A Rudensky (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center). Prdm1fl/fl mice were crossed to B6.Cg-Tg(Lck-cre)3779Nik/J mice to generate B6.Prdm1fl/fl-Lckcre/+ mice. Bcl-6fl/fl mice were crossed to Foxp3YFP-/Cre mice to generate Bcl-6fl/flFoxp3YFP/Cre mice. All mice were bred in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) animal facility. All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed according to guidelines outlined by the National Research Council.

Infections, BM chimeras and in vivo treatments

Influenza virus infections were performed intranasally (i.n) with 6,500 VFU of A/PR8/34 (PR8) in 100 μl of PBS. Acute LCMV infections were established by intraperitoneal injection with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV-Armstrong. In some experiments mice were immunized with 50 μg of recombinant hemagglutinin (HA) adsorbed to Alum (Imject® Alum, Thermo Scientific™). BM chimeric mice were generated by irradiating the indicated recipient mice with 950 Rads from an X-ray source delivered in 2 equal doses administered 4–5 h apart. Following irradiation, mice were intravenously injected with 5 × 106 total BM cells and were allowed to reconstitute for 8–10 weeks before influenza infection. In indicated experiments, experimental animals received an intraperitoneal injection of 50 μg/kg of diphtheria toxin (DT - Sigma) at the indicated time points. In some experiments, mice were intraperitoneally administered recombinant IL-2 (National Cancer Institute) at the indicated time points. Control mice received injections of PBS. In some experiments mice were treated with 500 μg of a mix of anti-IL-2 neutralizing antibodies (JES6-1A12 and S4B6) or 500 μg of Isotype control (2A3), all obtained from BioXcell.

Immunofluorescence

Lymph nodes were frozen in OCT (Tissue-Tek; Sakura) and 7 μm frozen sections were prepared and stained as described 49. Slides were probed for 30 min at 25 °C with anti-IgDb (2170-170), Anti-B220 (RA3-6B2) and anti-CD35 (8C12) obtained from BD Biosciences, and anti-Foxp3 (MF-14) from BioLegend. Biotin-conjugated primary antibodies were detected with streptavidin–Alexa Fluor 555 (S21381; Invitrogen Life Sciences). Images were obtained using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with a Zeiss Axiocam digital camera (Zeiss).

Cell preparation and flow cytometry

Cell suspensions from mLNs were prepared and filtered through a 70 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Cells were washed and resuspended in PBS with 2% donor calf serum and 10 μg/ml FcBlock (2.4G2 -BioXCell) for 10 min on ice before staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Fluorochrome-labeled anti-CD45.1 (clone A20, dilution 1/400), anti-CD45.2 (clone 104, dilution 1/400), anti-CD19 (clone 1D3, dilution 1/200), anti-CD138 (clone 281.2, dilution 1/500), Anti-Bcl-6 (clone K112.91, dilution 1/50), anti-CXCR5 (clone 2G-8, dilution 1/50), anti-CD4 (clone RM4–5, dilution 1/200), anti-CD95 (clone Jo2 dilution 1/500), anti-CD69 (clone H1.2F3, dilution 1/200), anti-GL7 (clone, GL7, dilution 1/500), anti-CD25 (clone PC61, dilution 1/200), anti-Blimp-1 (clone 5E7, dilution 1/100) and anti-pSTAT5 (PY694, clone 47-BD, dilution 1/50) were obtained from BD Biosciences. Anti-PD-1 (clone J43, dilution 1/100) and anti-Foxp3 (clone FJK-16s, dilution 1/200) were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-T-bet (clone 4B10, dilution 1/200) was purchased from BioLegend. Recombinant influenza nucleoprotein (NP) B-cell tetramers were prepared as previously described 16. The I-Ab NP311–325 MHC class II tetramer was obtained from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility. Dead cell exclusion was performed using 7-AAD (BioLegend). Intracellular staining was performed using the mouse regulatory T cell staining kit (eBioscience) following manufacturer’s instructions. For p-STAT5 staining, cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml of rIL-2 for 15 minutes and then fixed and permeabilized with BD Cytofix/cytopermTM buffer (BD) and the Phosflow Perm Buffer III (BD) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) and an Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (ThermoFischer Scientific).

Cell purification and adoptive transfer

CD45.1+ CD4+ and CD45.1+ CD8+ T cells were purified from the spleens of naïve B6.CD45.1+ mice by positive selection with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4+Foxp3+CD25hi, CD4+Foxp3+CD25lo and CD4+Foxp3− T cells were sorted from spleens of Foxp3-DTR/GFP mice using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) after positive selection with anti-CD4 MACS beads. Sorted cells (5 × 105) were transferred intravenously into naïve Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− recipient mice. All sorted T-cell subsets were more than 95% pure.

In vitro stimulation of influenza-induced Treg cells

CD4+Foxp3+CD25hi cells were sorted from spleens and mLNs of influenza-infected B6.129S6-Foxp3tm1DTR mice using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) after positive selection with anti-CD4 MACS beads. Sorted cells were activated using pre-load anti-CD3/CD28 MACSiBead Particles (Treg Expansion Kit, Miltenyi Biotec) at a bead-to-cell ratio of 3:1 in the presence of the indicated concentration of rIL-2 (Peprotech). Cells were cultured for 72 h at 37 °C in 125 μl in round-bottomed 96-well plates in RPMI-1640 supplemented with sodium pyruvate, HEPES (pH 7.2–7.6 range), nonessential amino acids, penicillin, streptomycin, 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (all from Gibco).

ELISAs

96-well plates (Corning™ Clear Polystyrene 96-Well Microplates) were coated overnight with purified PR8 proteins 50 at 1 μg/ml in 0.05 M Na2CO3 pH 9.6. Coated plates were then blocked for 1 h with 1% BSA in PBS. Serum from PR8-infected mice was collected and serially diluted (3-fold) in PBS with 10 mg/ml BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 before incubation on coated plates. After washing, bound antibody was detected with HRP-conjugated goat Anti-Mouse, IgG (g heavy chain specific) Ab (Southern Biotech) and quantified by spectrophotometry at 405 nm (OD).

ELISPOT

Multiscreen cellulose filter plates (Millipore) were coated overnight with 10 μg of histone from calf thymus (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells from the mLN were collected and plated starting at 3 × 106/well and in 2-fold serial dilutions in complete RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS. After 5 h, the wells were washed with PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20, and IgG was detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson immunoresearch). Spots were counted using a dissecting microscope. Images were taken using a CTL-immunoSpot S5 analyzer.

ANA analysis

For ANA analysis, serum was diluted 1:5 in PBS/0.2% BSA and incubated on Kallestad® HEp-2 Slides (Bio-rad). Slides were washed and stained with anti–mouse IgG FITC (SouthernBiotech). Slides were mounted with Aqua PolyMount and analyzed on a fluorescent microscope (Axio Observer.Z1). Images were obtained using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with a Zeiss Axiocam digital camera (Zeiss).

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq)

Conventional Treg cells (CD19−CD4+Foxp3+CD69hiPD-1loCXCR5loCD25hi) and T cells TFR cells (CD19−CD4+Foxp3+CD69hiPD-1hiCXCR5hiCD25lo) were sorted from the mLN of Foxp3-DTR/GFP mice at day 30 after influenza infection using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) after positive selection with anti-CD4 MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). RNA was isolated from the sorted cells using the Single cell RNA purification kit (Norgen Biotek Corp). Three replicates from three independent experiments for each condition were analyzed with RNA-seq. Library preparation and RNA sequencing was conducted through Genewiz. Libraries were sequenced using a 1×50bp single end rapid run on the HiSeq2500 platform. Sequence reads were trimmed to remove possible adapter sequences and nucleotides with poor quality (error rate < 0.05) at the end. After trimming, sequence reads shorter than 30 nucleotides were discarded. Remaining sequence reads were mapped to the Mus musculus mm10 reference genome using CLC genomics workbench v. 9.0.1 Differential gene expression was determined using DESeq2. Genes with an adjusted P-value <0.05 and an absolute Log2-fold change > 1 were considered significantly differentially expressed genes between conventional Treg cells and TFR cells.

GSEA, hierarchical clustering and visualization of RNA sequencing results

GSEA was performed using the Molecular Signatures Database on the publically available MIT BROAD Institute server. We ranked the 2002 genes obtained from RNA sequencing (Genewiz) according to a logarithmic transformation of each gene’s P-value multiplied by the sign of the corresponding logarithmic fold change, and subsequently utilized these rank lists to perform a gene set enrichment analysis (Broad Institute’s GSEA Java app, version 2.2.4). Given gene sets can include both activated and repressed genes, we additionally performed an extended assessment of gene enrichment of the two complementary gene sets against N ranked genes51, 52, to confirm the original GSEA results. Separately, we performed hierarchical clustering analysis 53, 54 of IL-2-induced genes that are differentially expressed in Treg cells vs TFR cells, using Matlab (version R2016b). Differential clusters are presented in the form of an annotated heatmap based on standardized expression values, along with the resulting hierarchical clustering dendogram. We additionally plotted in Matlab (version R2016b) the number and proportion of genes expressed within hallmark sets (GSEA), and their corresponding p-values.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software (Version 5.0a) was used for data analysis. The statistical significance of differences in mean values was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. RNA-seq data are available from GEO under accession code GSE101016.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank W. J. Leonard (US National Institutes of Health) for providing the Il21-mCherry-Il2-emGFP dual reporter transgenic mice, E. Meffre (Yale University) for providing the Blimp-1 reporter mice, A. Rudensky (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for providing the Foxp3–DTR–GFP mice and T.S. Simpler and U. Mudunuru for animal husbandry. This work was supported by University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and National Institutes of Health grants 1R01 AI110480 to A.B.-T, R01 AI116584 to B.L, AI097357 and AI109962 to T.D.R, AIAI109962 to F.E.L and AI049360 to A.J.Z. The X-RAD 320 unit was purchased using a Research Facility Improvement Grant, 1 G20RR022807-01, from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. Support for the UAB flow cytometry core was provided by grants P30 AR048311 and P30 AI027767.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS.

A.B.-T. designed and performed the experiments with help from B.L., H.B., M.J.F., J.E.B. and D.B. A.B.-T., D.B. and B.L. analyzed the data. T.T.M-L. and A.S.W. analyzed the RNAseq data. A.B.-T. wrote the manuscript. D.B. and B.L. contributed to data interpretation and manuscript editing. A.J.Z. performed LCMV infections. T.D.R. and F.E.L. contributed to manuscript editing and discussion, and provided reagents that were critical to this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Yuan X, Cheng G, Malek TR. The importance of regulatory T-cell heterogeneity in maintaining self-tolerance. Immunological reviews. 2014;259:103–114. doi: 10.1111/imr.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lio CW, Hsieh CS. A two-step process for thymic regulatory T cell development. Immunity. 2008;28:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao Z, et al. Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood. 2007;109:4368–4375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Cruz LM, Klein L. Development and function of agonist-induced CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the absence of interleukin 2 signaling. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1152–1159. doi: 10.1038/ni1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng G, Yu A, Dee MJ, Malek TR. IL-2R signaling is essential for functional maturation of regulatory T cells during thymic development. J Immunol. 2013;190:1567–1575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Rosa M, Rutz S, Dorninger H, Scheffold A. Interleukin-2 is essential for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell function. European journal of immunology. 2004;34:2480–2488. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadlack B, et al. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leon B, Bradley JE, Lund FE, Randall TD, Ballesteros-Tato A. FoxP3+ regulatory T cells promote influenza-specific Tfh responses by controlling IL-2 availability. Nature communications. 2014;5:3495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandiyan P, Zheng L, Ishihara S, Reed J, Lenardo MJ. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:1353–1362. doi: 10.1038/ni1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, et al. Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells promote T helper 17 cell development in vivo through regulation of interleukin-2. Immunity. 2011;34:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston RJ, Choi YS, Diamond JA, Yang JA, Crotty S. STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of TFH cell differentiation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:243–250. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nurieva RI, et al. STAT5 protein negatively regulates T follicular helper (Tfh) cell generation and function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:11234–11239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballesteros-Tato A, et al. Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity. 2012;36:847–856. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smigiel KS, et al. CCR7 provides localized access to IL-2 and defines homeostatically distinct regulatory T cell subsets. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211:121–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gratz IK, et al. Cutting Edge: memory regulatory t cells require IL-7 and not IL-2 for their maintenance in peripheral tissues. J Immunol. 2013;190:4483–4487. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raynor J, et al. IL-15 Fosters Age-Driven Regulatory T Cell Accrual in the Face of Declining IL-2 Levels. Frontiers in immunology. 2013;4:161. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung Y, et al. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nature medicine. 2011;17:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linterman MA, et al. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nature medicine. 2011;17:975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wollenberg I, et al. Regulation of the germinal center reaction by Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4553–4560. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sage PT, Francisco LM, Carman CV, Sharpe AH. The receptor PD-1 controls follicular regulatory T cells in the lymph nodes and blood. Nature immunology. 2013;14:152–161. doi: 10.1038/ni.2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sage PT, Paterson AM, Lovitch SB, Sharpe AH. The coinhibitory receptor CTLA-4 controls B cell responses by modulating T follicular helper, T follicular regulatory, and T regulatory cells. Immunity. 2014;41:1026–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wing JB, Ise W, Kurosaki T, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells control antigen-specific expansion of Tfh cell number and humoral immune responses via the coreceptor CTLA-4. Immunity. 2014;41:1013–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oestreich KJ, Mohn SE, Weinmann AS. Molecular mechanisms that control the expression and activity of Bcl-6 in TH1 cells to regulate flexibility with a TFH-like gene profile. Nature immunology. 2012;13:405–411. doi: 10.1038/ni.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levin AM, et al. Exploiting a natural conformational switch to engineer an interleukin-2 ‘superkine’. Nature. 2012;484:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aloulou M, et al. Follicular regulatory T cells can be specific for the immunizing antigen and derive from naive T cells. Nature communications. 2016;7:10579. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, et al. Key role for IL-21 in experimental autoimmune uveitis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:9542–9547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018182108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malek TR, Yu A, Vincek V, Scibelli P, Kong L. CD4 regulatory T cells prevent lethal autoimmunity in IL-2Rbeta-deficient mice. Implications for the nonredundant function of IL-2. Immunity. 2002;17:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng SG, Wang J, Wang P, Gray JD, Horwitz DA. IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta to convert naive CD4+CD25− cells to CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and for expansion of these cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:2018–2027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson TS, DiPaolo RJ, Andersson J, Shevach EM. Cutting Edge: IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta-mediated induction of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4022–4026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch MA, et al. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nature immunology. 2009;10:595–602. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bedoya F, et al. Viral antigen induces differentiation of Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells in influenza virus-infected mice. J Immunol. 2013;190:6115–6125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cretney E, et al. The transcription factors Blimp-1 and IRF4 jointly control the differentiation and function of effector regulatory T cells. Nature immunology. 2011;12:304–311. doi: 10.1038/ni.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollister K, et al. Insights into the role of Bcl6 in follicular Th cells using a new conditional mutant mouse model. J Immunol. 2013;191:3705–3711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Victora GD, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal centers. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:429–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maceiras AR, et al. T follicular helper and T follicular regulatory cells have different TCR specificity. Nature communications. 2017;8:15067. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsieh CS, Lee HM, Lio CW. Selection of regulatory T cells in the thymus. Nature reviews Immunology. 2012;12:157–167. doi: 10.1038/nri3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsieh CS, Zheng Y, Liang Y, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nature immunology. 2006;7:401–410. doi: 10.1038/ni1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu WW, Sun YH, Pante N. Nuclear import of influenza A viral ribonucleoprotein complexes is mediated by two nuclear localization sequences on viral nucleoprotein. Virol J. 2007;4:49. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Avalos AM, Busconi L, Marshak-Rothstein A. Regulation of autoreactive B cell responses to endogenous TLR ligands. Autoimmunity. 2010;43:76–83. doi: 10.3109/08916930903374618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mandal M, et al. Epigenetic repression of the Igk locus by STAT5-mediated recruitment of the histone methyltransferase Ezh2. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1212–1220. doi: 10.1038/ni.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker SR, Nelson EA, Frank DA. STAT5 represses BCL6 expression by binding to a regulatory region frequently mutated in lymphomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:224–233. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonald PW, et al. IL-7 signalling represses Bcl-6 and the TFH gene program. Nature communications. 2016;7:10285. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vang KB, et al. IL-2, -7, and -15, but not thymic stromal lymphopoeitin, redundantly govern CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development. J Immunol. 2008;181:3285–3290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bayer AL, Lee JY, de la Barrera A, Surh CD, Malek TR. A function for IL-7R for CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:225–234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rangel-Moreno J, et al. The development of inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue depends on IL-17. Nature immunology. 2011;12:639–646. doi: 10.1038/ni.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee BO, et al. CD4 T cell-independent antibody response promotes resolution of primary influenza infection and helps to prevent reinfection. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:5827–5838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lim WK, Lyashenko E, Califano A. Master regulators used as breast cancer metastasis classifier. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2009:504–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carro MS, et al. The transcriptional network for mesenchymal transformation of brain tumours. Nature. 2010;463:318–325. doi: 10.1038/nature08712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bar-Joseph Z, Gifford DK, Jaakkola TS. Fast optimal leaf ordering for hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(Suppl 1):S22–29. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.suppl_1.s22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. RNA-seq data are available from GEO under accession code GSE101016.