Abstract

Kin and multilevel selection theories predict that genetic structure is required for the evolution of cooperation. However, local competition among relatives can limit cooperative benefits, antagonizing the evolution of cooperation. We show that several ecological factors determine the extent to which kin competition constrains cooperative benefits. In addition, we argue that cooperative acts that expand local carrying capacity are less constrained by kin competition than other cooperative traits, and are therefore more likely to evolve. These arguments are particularly relevant to microbial cooperation, which often involves the production of public goods that promote population expansion. The challenge now is to understand how an organism’s ecology influences how much cooperative groups contribute to future generations and thereby the evolution of cooperation.

Keywords: social evolution, multilevel selection, kin selection, group selection, altruism, viscous population, Hamilton’s Rule, relatedness, local competition, scale of competition, hard selection, soft selection, density dependence, limited dispersal, Price equation, public good

Limited dispersal and the evolution of cooperation

Explaining the evolution of cooperative or altruistic traits is a fundamental challenge in evolutionary theory. Cooperative traits impose a cost on individuals exhibiting the trait to the benefit of other individuals. Consequently, within-group natural selection disfavors cooperative individuals, favoring instead individuals that cheat or freeload by avoiding the costs of cooperation while continuing to receive the benefits provided by cooperative individuals1, 2. Despite this, cooperation is commonplace in nature, being found in a variety of biological systems including primates3, social insects4 and bacteria5, suggesting that costs of cooperation can be overcome.

Hamilton posed the first evolutionary explanation of how cooperation can evolve despite its direct costs1, 6, known as Hamilton’s rule (see Glossary). He showed that cooperative traits can evolve whenever the benefits that recipients accrue weighted by genetic relatedness outweigh the costs that actors pay1, 6. Accordingly, relatedness is required for the evolution of cooperative traits; that is, individuals must tend to interact within family groups or with other genetically similar individuals. Relatedness among interacting individuals can arise due to limited dispersal or assortative interactions based on genetic similarity1, 6. Limited dispersal can be a particularly powerful means of generating relatedness because it does not require active kin recognition but can yield substantial between-group genetic variation1. Groups with a higher proportion of cooperative individuals can then have higher productivity and this increased productivity can be sufficient to overcome the costs of cooperation (see Box 1)7.

Box 1. Kin competition in social evolutionary theory.

Kin and multilevel selection theories are the two most prominent frameworks for the evolution of cooperation. While these complementary approaches partition fitness differently, they are fully interchangeable frameworks for social evolution18, 19. Multilevel and kin selection models both emphasize the importance of genetically structured interactions, wherein individuals are more likely to cooperate with individuals with whom they are more genetically similar69, 70. Despite their similarities, these frameworks address the potential antagonistic effects of kin competition on the evolution of cooperation in different ways.

Kin selection theorists have incorporated kin competition’s antagonistic effect into Hamilton’s rule using a variety of approaches9. One approach is to augment the cost of cooperation with an additional term accounting for the decrease in fitness associated with kin competition, weighted by the relatedness of the actor to the individuals experiencing this fitness cost11, 14. The effect can also be put into the benefit term by devaluing the benefit to a degree that depends on the scale of competition71. Alternatively, the effect can be captured in the relatedness term by defining relatedness relative to the subpopulation of competitors (rather than the global population)13.

Just as Hamilton’s rule is the centerpiece of kin selection theory, partitioning selection into within- and between-group components is essential to multilevel selection approaches to social evolution72, 73. Though cooperative traits are expected to be selected against within groups whenever there is variation within groups, they can be selectively favored between groups if cooperative groups are more productive than less cooperative groups72. Between-group responses to selection depend on the degree of genetic structure among groups. Low relatedness corresponds to a high proportion of genetic variation within groups, while high relatedness corresponds to a high proportion of genetic variation between groups74. Considering this, it is not surprising that the formal equivalence of kin and multilevel selection models has been demonstrated by many researchers19, 72, 75.

The multilevel selection approach emphasizes that cooperative groups must be more productive in order for the cooperative trait to spread by between-group selection. If the population density of all groups is regulated at the local scale to the same density, then the spread of cooperation is stymied because uniform local density dependence precludes cooperative groups from being more productive than less cooperative groups (Figure 1a)7, 12, 29. This directly parallels kin selection models that incorporate the effect of kin competition by devaluing cooperative benefits71.

Viscous populations are characterized by limited dispersal. Discussions of population viscosity and the evolution of cooperation have emphasized the potential for kin competition to limit the evolution of cooperation in viscous populations8–10. While cooperative individuals are more likely to benefit kin in viscous populations, they also compete for limiting resources with these same kin. Early theoretical work found that such kin competition can strongly antagonize the benefits of kin cooperation and inhibit the evolution of cooperation in viscous populations9, 11–15. Consistent with this, empirical studies have failed to find a relationship between relatedness and aggressiveness in fig wasps16 and bruchid beetle larvae17, suggesting that the effects of kin competition might negate any kin-selected benefits associated with being less aggressive toward kin.

We critically evaluate the importance of kin competition in constraining the evolution of cooperation and demonstrate that the evolution of cooperation is facilitated when the cooperative trait increases local population productivity. In addition, we explicitly examine the ecological factors influencing the evolution of cooperation and conclude that for many systems limited dispersal facilitates, not antagonizes, the evolution of cooperation. This conclusion stems from the fact that ecological factors can influence the degree of kin competition, the benefits of cooperation, and the degree to which individuals cooperatively interact with kin.

Ecological factors influence social evolution

Results from kin and multilevel selection theories have shown that kin competition can antagonize the evolution of cooperation. Many theoreticians have demonstrated that these frameworks are complementary descriptions of the same evolutionary processes18, 19 (Box 1). The Price equation has proven a particularly useful conceptual tool for identifying the common foundations of kin and multilevel selection theories18–20 (Box 2). Extending this approach, we show that when cooperative traits increase the pre-dispersal population size of local groups there can be additional pathways for cooperative benefits that promote the evolution of cooperation (Figures 1 and 2; Box 2). That is, increased local carrying capacity or relaxed local density dependence can facilitate the evolution of cooperation within viscous populations even in the face of kin competition. In studies emphasizing the negative effect of local scale competition, the relationship between population size and fitness is thought to be negative because of increased kin competition, potentially reducing the rate of genetic change. We describe multiple circumstances in which this relationship can be positive, thereby facilitating the evolution of cooperation.

Box 2. Hamilton’s rule when cooperative behavior influences population expansion.

The effect of genetically determined population expansion on the response to selection can be incorporated into a kin selection model using Queller’s method76. A simplified version of the Price equation20 describes selection’s effect on the population average genetic composition

| Eqn. 1 |

where Gi and Wi represent the ith individual’s genes underlying the trait and fitness, respectively.

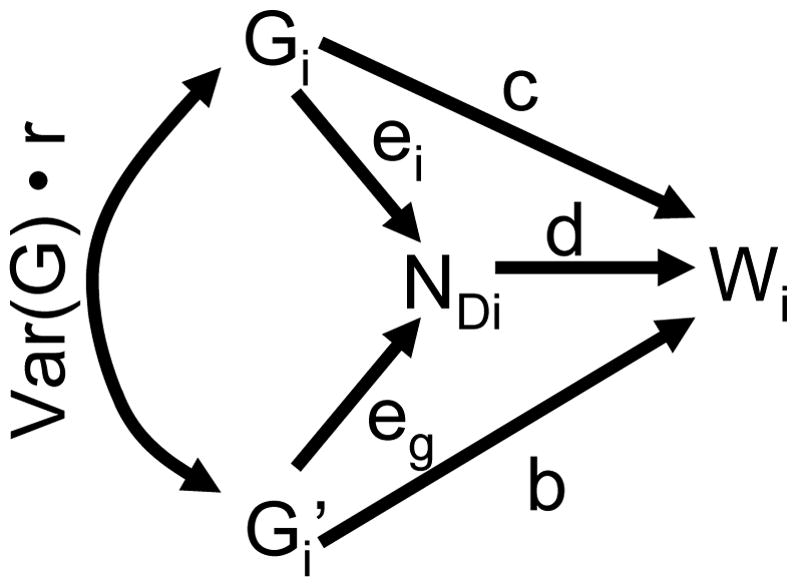

For a social trait that influences population size the relative fitness of an individual depends on its own genes (Gi), its neighbor’s genes ( ), and the pre-dispersal size of the individual’s group (NDi) (Figure 2). Thus, an individual’s fitness can be described by the following least squares regression:

| Eqn. 2 |

wherein describes the average genic value of the group and each of the partial regression coefficients, of the form βWX•YZ, describes the linear relationship between fitness and the X variable holding the other variables (Y and Z) constant, while α and ε represent the intercept and residuals of the model, respectively. The average genic value of the group and the genic value of the focal individual also influence population size, represented by a second regression:

| Eqn. 3 |

This assumes a simple form of density-regulation where population size depends only on the genetic composition of the group. Combining Equations 1, 2, and 3 gives the following expression for the response to selection:

| Eqn. 4 |

A modified form of Hamilton’s rule can be recovered from Equation 4 by simply dividing through by Var(Gi):

| see Table I | Eqn. 5 |

As identified by Queller, the first two terms of Equation 5 are analogous to the cost (c) and the benefit term (b • r), giving Hamilton’s rule when there are no paths through NDi76.

The third and fourth terms of Equation 5 describe the direct and indirect feedbacks on genetic change through population size, respectively. The direct feedback depends on how fitness changes as a linear function of group size (βWN•G′G or d) and how population size changes as a linear function of a focal individual’s genes (βNG•G′ or ei). The effect through indirect feedback similarly depends on the benefits or costs accrued through growth or decline of the individual’s group (d) and how group size changes as a linear function of neighbor’s genes (βNG′•G or eg), and is also mediated by relatedness. These additional terms potentially augment cooperative benefits thereby facilitating the evolution of cooperation in viscous populations despite kin competition.

Table I.

Variables used in deriving modified version of Hamilton’s rule for cooperative traits that influence population growth or decline

| Regression coefficient | Interpretation | Simplified notation |

|---|---|---|

| βWG•G′N | Fitness cost of cooperation | c |

| βWG′•GN | Fitness benefit of cooperation stemming from effects on neighbors | b |

| βG′G | Relatedness | r |

| βWN•G′G | Fitness benefit or cost resulting from group elasticity | d |

| βNG•G′ | Elasticity of group size in response to focal individual’s genes | ei |

| βNG′•G | Elasticity of group size in response to neighbor’s genes | eg |

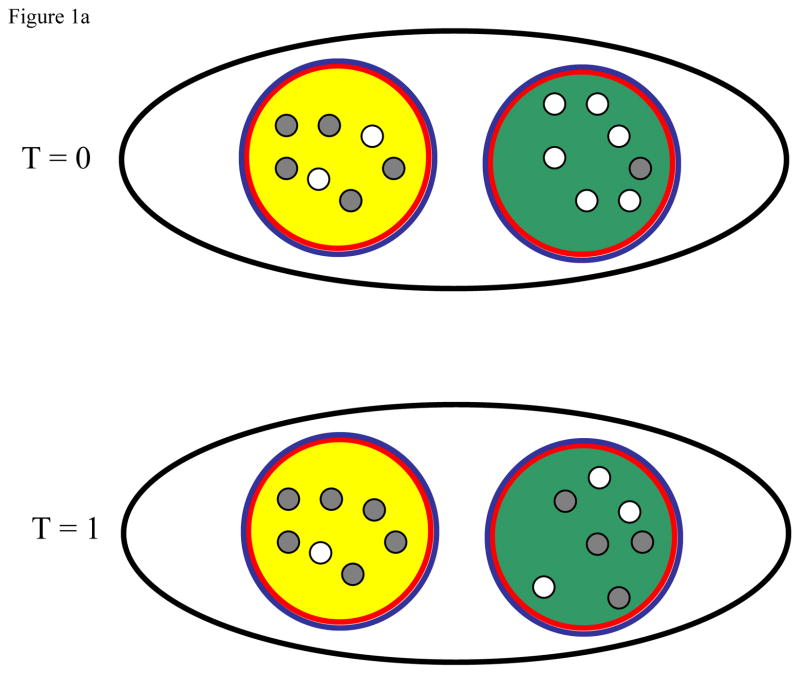

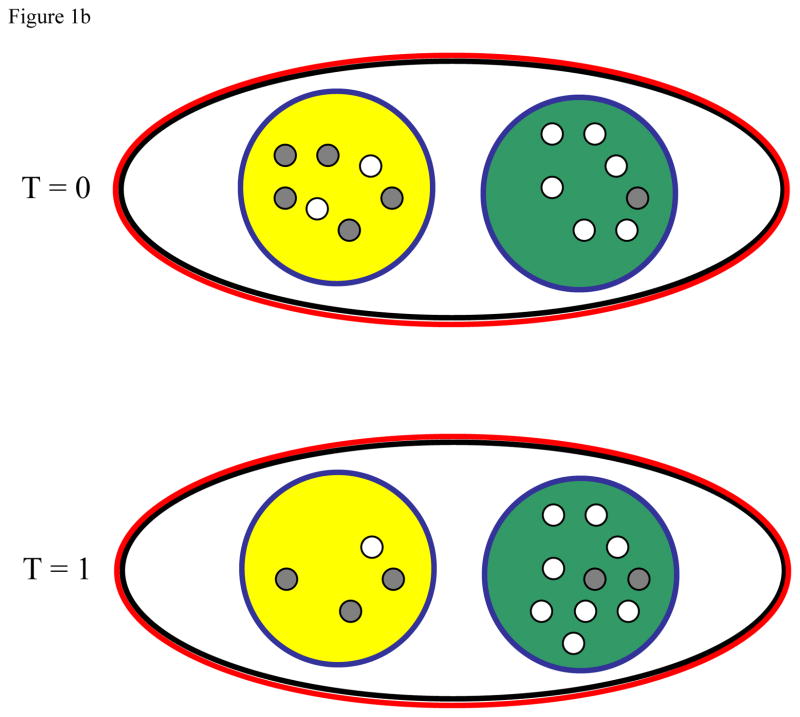

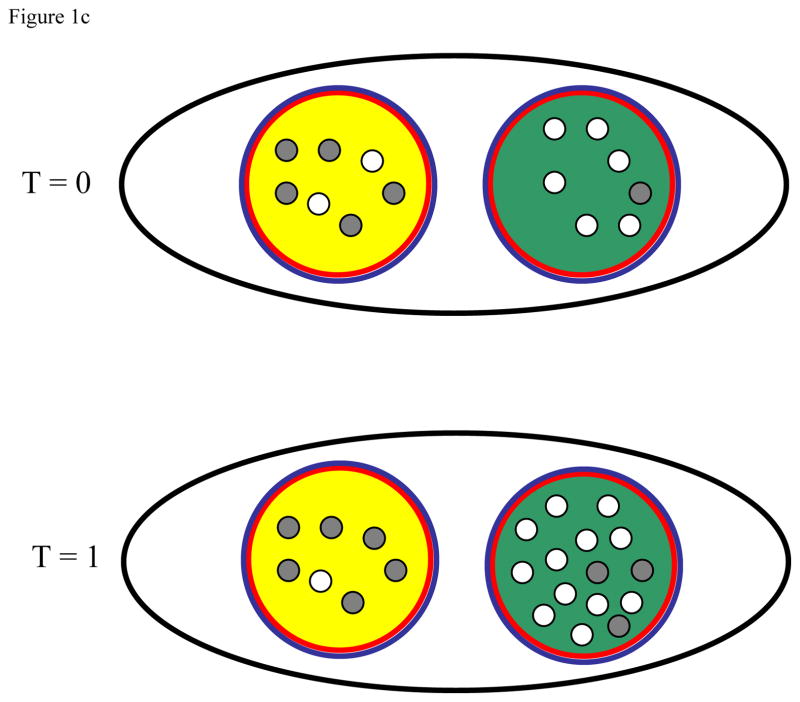

Figure 1.

Illustration of how local density dependence (a), global density dependence (b), and local carrying capacity elasticity (c) influence the evolution of a cooperative trait. In each, the black line demarks the population while the blue and red lines indicate the scale of cooperation and density dependence, respectively. Gray dots represent non-cooperative individuals while open dots represent cooperative individuals. In all cases, the green group has a higher initial (T = 0) frequency of cooperative individuals than does the yellow group. For each ecological scenario we then show the composition of both groups after cooperation and reproduction, but before the progeny disperse (T = 1).

Figure 1a. Cooperative traits are unlikely to spread when local density dependence occurs at the same scale as cooperative benefits if the cooperative behavior does not increase the locally carrying capacity. In this example, the local carrying capacity is fixed at seven individuals for each group and for simplicity each group is assumed to stay at this carrying capacity. After cooperation and reproduction, the frequency of cooperative individuals decreases within both groups due to the cost associated with the cooperative behavior. Under these ecological conditions, local density dependence constrains group productivity such that cooperative groups do not contribute more to the next generation, preventing the spread of cooperative individuals in the global population.

Figure 1b Global density dependence facilitates the spread of cooperative traits by allowing cooperative groups to contribute more to the next generation. In this example, the scale of density dependence is more global than the scale of cooperation. For simplicity, the global carrying capacity is fixed in this example. Under these conditions, cooperative individuals once again decline in frequency within both interaction groups; however their frequency increases globally because the group with more cooperative individuals contributes more to the next generation. The more cooperative group is shown larger at T = 1 than T = 0. It might not remain this way as the additional individuals can subsequently disperse away. Conditions that facilitate the potential of a cooperative interaction group exporting the benefits of cooperation (e.g. empty sites33 and kin-structured dispersal55) help facilitate the evolution of cooperation.

Figure 1c. Cooperative traits that increase local carrying capacity are able to spread under local density dependence. When a cooperative trait increases the local carrying capacity, cooperative groups contribute more to the next generation thereby facilitating the spread of cooperative traits. As before, the frequency of cooperators declines within both groups due to the costs of cooperation. Though differing in the scale of density dependence, this case is similar to that of Figure 1b in that both depend on elasticity of group productivity resulting from cooperation. Likewise, increased local population size in response to the cooperative behavior also facilitates the evolution of cooperation under global density dependence (Figure 1b and 1c).

Figure 2.

Path diagram of factors influencing individual fitness for a cooperative trait that influences population growth or decline. This yields a modified version of Hamilton’s rule that includes the direct and indirect fitness consequences of the cooperative trait (c and b • r, respectively) as well as the direct and indirect effects of the trait’s impact on pre-dispersal population size (d • ei and d • eg • r, respectively).

In this section, we examine the ecological conditions that promote the evolution of cooperation despite kin competition in viscous populations. Ecological factors such as the scale of density dependence, population elasticity, and patterns of dispersal influence the degree to which cooperative groups can contribute to the next generation and thus shape the selective pressures acting on cooperative traits.

Scale of population density dependence

The manner in which population density is regulated can alter the evolutionary process. This is particularly true when selection occurs both within- and between-groups because density regulation can influence how much each group contributes to the next generation21. Kin competition is most antagonistic to the evolution of cooperation when cooperative groups are constrained in their productivity22. For this reason, the evolution of cooperation is unlikely when the scale of cooperation is larger than or equal to the scale at which group size is regulated to a fixed carrying capacity (see Figure 1a)21, 23. Such scenarios can occur when reproductive potential is locally fixed (Box 3).

Box 3. Taylor’s kin selection model of cooperation with competition.

Taylor presented a simple patch-structured model of the evolution of cooperation wherein cooperation increases the competition for space experienced by the progeny of a cooperator11. This model envisions cooperative acts that increase the number of offspring produced on a local patch by nb at the cost of cooperative mothers who produce nc fewer offspring. The fitness of a focal cooperative asexual female depends on her indirect benefits of cooperating (R • nb), her direct cost of cooperating (nc), and the cost of having related individuals displaced by the extra individuals present on the patch because of the cooperative act (sR • s (nb - nc)), with s being the probability that an individual remains in its natal patch and R being the average relatedness in the patch. The model assumes that s(nb - nc) individuals are above carrying capacity, which is fixed by the number of breeding sites on the patch (F). The focal female’s relatedness to these displaced individuals is given by sR.

Assuming females are equally productive, the probability that any two individuals on the patch are siblings is given by . The probability that two individuals are non-sibling relatives is given by . These probabilities sum to give relatedness. The cooperative trait is predicted to spread when the net fitness gain of a cooperative individual is greater than zero. With the costs, benefits, and relatedness described above this occurs when females accrue a net benefit to themselves ( ) because kin selected benefits are exactly cancelled by the effects of kin competition.

This model makes a number of simplifying assumptions that enhance the degree to which kin competition antagonizes the evolution of cooperation. In this model, individuals compete locally for a fixed number of breeding sites in a fully saturated environment (see Figure 1a). Relaxing the restrictive conditions of Taylor’s model has provided a useful approach for subsequent investigations of conditions facilitating the evolution of cooperation31, 33. Allowing population elasticity (either through increased local density or effective dispersal to other patches) or allowing a more global scale of competition can greatly facilitate the spread of cooperation in viscous populations by enhancing the degree to which cooperative groups contribute to the next generation (Box 2, Figure 1b and 1c).

Hamilton provided an example of this when he pointed out that competition among siblings for resources within the same mammalian womb slows the rate of evolution of a cooperative behavior between these siblings1. Siblings only have “a local standard–sized pool of reproductive potential” available to them via the provisioning of their mother1. Despite the high assurance that the genes of individuals within the same womb covary, cooperative behaviors directed toward siblings within the same womb are unlikely to evolve because the scale of cooperation equals that of competition and the available resources are fixed. Considering this, it is perhaps unsurprising that sibling rivalry sometimes results in hostile interactions among mammalian and avian siblings within the same womb or in the same nest24, 25. In fact, while local competition resulting from limited dispersal antagonizes the evolution of cooperation, it can also favor the evolution of spiteful interactions25, 26 and the dispersal of individuals away from the natal site27, 28.

Early discussion of the evolution of cooperation with kin competition focused on ecologies that are restrictive to the evolution of cooperation (see Box 3). This led to the common view that special conditions are required to explain the evolution of cooperative behaviors that occur without subsequent dispersal. Taylor’s patch-structured model of altruism in a viscous population has been one of the most influential theoretical investigations of the effects of kin competition on the evolution of cooperation11 (Box 3). The main result of this work demonstrates that under the assumed life-history and ecological conditions the effects of kin competition fully offset the benefits of cooperation. Researchers have argued that patterns of sibling competition in organisms with inelastic local competition (Figure 1a), such as beetles17 and fig wasps16 competing at natal sites, are consistent with the predictions of Taylor’s model.

The effect of kin competition is weakened when density dependence is more global than the local scale of cooperation because global density dependence allows cooperative groups to be more productive than less cooperative groups7, 16 (Figure 1b). Griffin et al.29 experimentally tested this prediction by examining how the scale of density dependence influences the evolution of cooperative siderophore production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Many bacterial pathogens facultatively produce extracellular siderophores that aid neighboring cells in acquisition of limiting iron by ligating free or bound iron in the external environment. As expected, cooperative siderophore-producing strains spread under global but not local density dependence29. As with any cooperative behavior, siderophore producers pay the cost of production and thus are selected against within their groups regardless of the scale of density dependence. However, under global density dependence there is increased potential for between-group benefits of the behavior to override this cost.

Many factors determine the degree to which cooperative groups are able to be more productive. When cooperative benefits are directed to recognized kin or excluded from non-kin, cooperation likely occurs at a more local scale than does competition and there is a positive genetic covariance (relatedness) among interacting individuals30. The scale of cooperation can also be more restricted than the scale of competition whenever cooperative behaviors are timed to occur before dispersal11, 31. This is notably the case when juveniles cooperate at or near the natal site before then dispersing away from the site. Here cooperatively interacting individuals enjoy the benefits of viscosity (e.g. enhanced relatedness) but minimize its drawbacks (i.e. kin competition) since by separating after cooperating they have less opportunities to compete with their kin. However, there is still potential for kin competition if available breeding sites are limited32, 33.

Population elasticity

Group productivity can vary in elastic populations22. In such populations, cooperative behaviors can affect a variety of factors that influence how much a group contributes to the next generation by increasing the group’s population density, range, migrant output, or survivorship22, 32, 34–37. The organism’s ecology determines which of these effects can vary depending on the genetic composition of the group. A cooperative behavior can increase group productivity by increasing the group’s local carrying capacity (Figure 1c) or when population density is regulated at a scale broader than the scale of cooperation (Figure 1b). In each case, the scope of cooperative benefits is greater than it is when fixed reproductive potential constrains the productivity of the group (i.e. groups are locally inelastic). These additional benefits increase the degree to which group (and kin) selection favors the cooperative trait (Box 2).

Competition for breeding sites (space) illustrates how the selective dynamics of cooperation depends on the potential for groups to export the benefits of cooperation. When breeding sites are fixed and fully occupied, competition for space is particularly fierce11 (Box 3). However, when empty sites are available kin competition is likely to be less severe and as a consequence the fitness of cooperative individuals is less compromised33. In this case, there are more sites available thereby reducing competition such that the increased demand for sites due to cooperation does not necessarily come at the expense of the fitness of the cooperative individual. The availability of empty sites facilitates the evolution of cooperation by allowing the export of cooperative benefits from cooperative groups, so that such groups can be more productive than non-cooperative groups.

The benefits of cooperation often stem from the increased reproductive potential of groups of individuals. In many species, males are less constrained in their reproductive potential because they are able to attain higher fitness via increased access to females38, 39. Because of this, coalitions of males that cooperatively court can have more reproductive potential than males courting alone, even though subordinate males in coalitions have lower reproductive success than solo males40. For example, coalitions of related male turkeys have overall more success than do solo males, as the net effect of cooperating is positive40. This is despite subordinate males in coalitions having poor reproductive success due to competition with the coalition’s dominant male.

Cooperative behaviors that increase the local carrying capacity of a group also allow for increased group productivity. Microbial cooperation is often associated with public goods that can increase the local carrying capacity (reviewed in ref.5). Examples include the production of siderophores41, viral replication enzymes42, specialized resources43, 44, and secreted exoenzymes45. In these cases, a cooperative group is able to grow to a higher local density than can a non-cooperative group. The effects of this increased group productivity can offset the consequences of kin competition (Figure 1c). For example, Kümmerli et al. have shown experimentally that cooperation can spread when highly productive siderophore producing groups are able to export these cooperative benefits because of an advantage in colonizing new subpopulations, but fails to spread without this colonization advantage46.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a common plant pathogen, provides an illustrative example. The Ti plasmid of A. tumefaciens confers the ability to cause plant tissues to produce opines, a specialized resource that only cells harboring a Ti plasmid can catabolize47. Expressing the virulence system is costly to the individual cell and the benefits of this cooperative act are available to any Ti plasmid bearing cell near the infection. As consequence, an Agrobacterium subpopulation in the vicinity of an infected plant has a higher local carrying capacity than a group in the non-disease environment43. Because opines can only be catabolized by cells bearing the virulence plasmid, this organism employs a greenbeard-like ‘recognition’ that ensures that cooperative benefits are only available to genetically similar individuals. These individuals are likely to have both virulence and opine catabolic functions due to linkage of these genes on the Ti plasmid. The cooperative pathogenesis of A. tumefaciens increases both the competitive ability and carrying capacity of cells with a Ti plasmid at the site of the infection allowing increased group productivity.

The mutualistic association among rhizobia and legumes similarly results in increased carrying capacity of the bacteria near the nodule due to increased plant exudates48, 49. As with the Agrobacterium system, these increased plant exudates sometimes include specialized resources (rhizopines) that can only be catabolized by other rhizobia50. Recently, several authors have argued that the evolution of cooperation among rhizobia is strongly hindered by kin competition at the nodule 51, 52. These arguments ignore the consequences of population elasticity and greenbeard-like recognition which are likely to swamp out the effects of kin competition. Similar increases in local carrying capacity potentially play roles in the evolution of other root symbionts including arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi53.

Patterns of dispersal

Many of the factors restricting the importance of kin competition in viscous populations can be thought of as the effects of metapopulation and life-history features. We have discussed some of the ways in which these attributes can influence the impact of kin competition (e.g. its effects are limited when individuals disperse after cooperating) and the benefits of cooperative traits (e.g. empty sites increase the potential for benefits through increased group productivity).

Patterns of dispersal play a large role in shaping the genetic structure of populations54. In viscous populations, limited dispersal generally promotes both the genetic similarities among interacting individuals and the degree of kin competition9. Notably, kin-structured dispersal strongly promotes the maintenance of a high degree of relatedness thereby promoting the evolution of cooperative traits55–57. A wide range of organisms exhibit kin-structured dispersal including vertebrates58, plants59, insects60, 61, and bacteria62. Thus, kin-structured dispersal can be important to the evolution of cooperation in many systems. To date, support for this remains largely theoretical and a topic for future empirical research.

Viscosity and social evolution in macro- versus micro-organisms

At the simplest level, in order for kin competition to hinder the spread of cooperation, individuals must compete and cooperate with the same individuals. However, ecological factors alter the degree to which kin competition antagonizes the evolution of cooperation. Whenever cooperative groups are more productive than less cooperative groups there is potential for between-group selection to favor the spread of the cooperative trait. This is likely when population density is globally regulated and/ or if local density dependence is non-uniform. Either way, cooperative groups are more productive in terms of migrants, expansion, or persistence (Box 2). Higher group productivity augments the benefits associated with cooperative traits, potentially offsetting the negative effects of kin competition (Table 1). We have reviewed the ecological factors that determine the impact of kin competition and argue that for many biological systems population viscosity is more likely to promote the evolution of cooperation than hinder it.

Table 1.

Some factors promoting the evolution of cooperation in viscous populations

| Factor | Increases cooperative benefits | Restricts relative scale of competition | Increases relatedness | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population elasticity34, 35, 77 | ✓ | ✓ | Social insects78 Cooperatively breeding beetles79 Beaver dam construction80 AM Fungi53 Myxococcus cooperative predation45 Agrobacterium opine catabolism47 Rhizobium rhizopine catabolism48 Pseudomonas siderophore production29 |

|

| Empty sites33 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Global density dependence7, 29 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kin recognition30 | ✓ | ✓ |

Agrobacterium opine catabolism47 Rhizobium rhizopine catabolism48 Social insect colony discrimination4 |

|

| Kin-structured dispersal55, 56 | ✓ | Colony fission or budding of social insects60 Bacterial biofilm dispersal62 |

The widespread notion that kin competition limits the evolution of cooperation in viscous populations is likely an outgrowth of early models focusing on competition in a saturated environment11, 12 and macro-organisms with relatively inelastic populations16. Social evolution researchers are increasingly turning their attention to microbial cooperation (reviewed by ref.5). Some authors have suggested that the evolution of some forms of microbial cooperation should be expected to be constrained by the fact that cooperation and competition occur at the same spatial scale51, 52. However, microbial populations are generally more elastic than those of macro-organisms, thus limiting the potential for kin competition to outweigh the benefits of cooperation. For example, while the number of breeding sites and mates that sibling birds are competing for are fixed, there is considerably more potential for the behavior of microbes to increase the availability of resources in their environment through cooperative acts (e.g. siderophores increasing iron availability, bacterial pathogens increasing release of resources from hosts, and root symbionts increasing plant exudates). We therefore conclude that for many cooperative systems, particularly microbial ones, limited dispersal is more likely to favor, rather than hinder, the evolution of cooperation by facilitating interactions among kin.

There is a growing body of theoretical work showing that patterns of spatial structure determined by migration alter ecological and evolutionary dynamics23, 63–65. In this paper, we review how the interplay of these dynamics influences the evolution of cooperation. Many aspects of this interplay have been underappreciated. To move forward, future research must begin to account for the ways in which ecological factors influence the costs and benefits of cooperative traits. This is particularly important as the frameworks of social evolution are applied to organisms with varied life-histories such as plants66, 67, fungi53, 68, and microbes5. Moreover, future studies on all organisms should examine the importance of ecological factors that play strong roles in social evolution.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yaniv Brandvain, Clay Fuqua, Anna Larimer, Dave Queller, Joan Strassmann, David Van Dyken, and Mike Wade for helpful conversations and insightful comments on this manuscript. We would also like to thank Stuart West and two anonymous reviewers for suggestions that improved the manuscript. Funding was provided by NSF (DEB 0616891 and DEB 0608155) and an NIH training grant (T32 GM007757).

Glossary

- Carrying capacity

maximum sustainable population size

- Global density dependence

when the density of a population is determined at a broad spatial scale; for example, where there is a well mixed food source or where predation is by a roaming predator

- Group productivity

contribution of a group to the next generation; this can depend on migrant dispersal, group survival, or changes in the group’s range

- Hamilton’s rule

prediction that a costly trait benefiting other individuals evolves only when the relatedness weighted benefits of the trait outweigh its direct costs (r • b > c); the cost (c) and benefit (b) describe how the relative fitnesses of the cooperative individual and beneficiaries, respectively, change because of the trait’s expression

- Kin selection

framework of social evolution that emphasizes the costs (c), benefits (b), and genetic relatedness (r) of social interactions (see Hamilton’s rule)

- Local density dependence

when the density of a population is determined by locally acting density regulating processes; for example, where resources are distributed on a local scale

- Multilevel selection (group selection)

evolutionary framework that partitions the effects of selection into within-group and between-group components

- Population elasticity

potential for group productivity to change

- Scale of competition

spatial scale over which competitive interactions influencing an individual’s fitness occur

- Scale of cooperation

spatial scale over which cooperative interactions influencing an individual’s fitness occur

- Relatedness

measure of the statistical association among the genes of interacting individuals (see Hamilton’s rule)

- Viscous population

population characterized by limited dispersal such that individuals tend to live near their natal site

References

- 1.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behavior. I. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1964;7:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wade MJ, Breden F. The evolution of cheating and selfish behavior. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1980;7:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley BJ. Levels of selection, altruism, and primate behavior. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1999;74:171–194. doi: 10.1086/393070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourke AFG, Franks NR. Social evolution in ants. Princeton University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.West SA, et al. The social lives of microbes. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics. 2007;38:53–77. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behavior. II. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1964;7:17–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wade MJ. Soft selection, hard selection, kin selection, and group selection. American Naturalist. 1985;125:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Mouden C, Gardner A. Nice natives and mean migrants: the evolution of dispersal-dependent social behaviour in viscous populations. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2008;21:1480–1491. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West SA, et al. Cooperation and competition between relatives. Science. 2002;296:72–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1065507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grafen A, Archetti M. Natural selection of altruism in inelastic viscous homogeneous populations. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2008;252:694–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor PD. Altruism in viscous populations: an inclusive fitness model. Evolutionary Ecology. 1992;6:352–356. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson DS, et al. Can altruism evolve in purely viscous populations? Evolutionary Ecology. 1992;6:331–341. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Queller DC. Genetic relatedness in viscous populations. Evolutionary Ecology. 1994;8:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grafen A. Natural selection, kin selection, and group selection. In: Krebs JR, Davies NB, editors. Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach. Blackwell Scientific; 1984. pp. 62–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Queller DC. Does population viscosity promote kin selection? Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1992;7:322–324. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(92)90120-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West SA, et al. Testing Hamilton’s rule with competition between relatives. Nature. 2001;409:510–513. doi: 10.1038/35054057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smallegange IM, Tregenza T. Local competition between foraging relatives: Growth and survival of bruchid beetle larvae. Journal of Insect Behavior. 2008;21:375–386. doi: 10.1007/s10905-008-9133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bijma P, Wade MJ. The joint effects of kin, multilevel selection and indirect genetic effects on response to genetic selection. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2008;21:1175–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Queller DC. Quantitative genetics, inclusive fitness, and group selection. American Naturalist. 1992;139:540–558. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price GR. Selection and covariance. Nature. 1970;227:520–521. doi: 10.1038/227520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly JK. The effect of scale-dependent processes on kin selection: mating and density regulation. Theoretical Population Biology. 1994;46:32–57. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor PD. Inclusive fitness in a homogeneous environment. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 1992;249:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lion S, van Baalen M. Self-structuring in spatial evolutionary ecology. Ecology Letters. 2008;11:277–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mock DM, Parker GA. The Evolution of Sibling Rivalry. Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner A, et al. Spiteful soldiers and sex ratio conflict in polyembryonic parasitoid wasps. American Naturalist. 2007;169:519–533. doi: 10.1086/512107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breden F, Wade MJ. Selection within and between kin groups of the imported willow leaf beetle. American Naturalist. 1989;134:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Galliard JF, et al. Mother-offspring interactions affect natal dispersal in a lizard. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 2003;270:1163–1169. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore JC, et al. Kin competition promotes dispersal in a male pollinating fig wasp. Biology Letters. 2006;2:17–19. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin AS, et al. Cooperation and competition in pathogenic bacteria. Nature. 2004;430:1024–1027. doi: 10.1038/nature02744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehmann L, Perrin N. Altruism, dispersal, and phenotype-matching kin recognition. American Naturalist. 2002;159:451–468. doi: 10.1086/339458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor PD, Irwin AJ. Overlapping generations can promote altruistic behavior. Evolution. 2000;54:1135–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Baalen M, Rand DA. The unit of selection in viscous populations and the evolution of altruism. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1998;193:631–648. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alizon S, Taylor P. Empty sites can promote altruistic behavior. Evolution. 2008;62:1335–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitteldorf J, Wilson DS. Population viscosity and the evolution of altruism. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2000;204:481–496. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehmann L, et al. Population demography and the evolution of helping behaviors. Evolution. 2006;60:1137–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Killingback T, et al. Evolution in group-structured populations can resolve the tragedy of the commons. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B. 2006;273:1477–1481. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grafen A. Detecting kin selection at work using inclusive fitness. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B. 2007;274:713–719. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krakauer AH. Sexual selection and the genetic mating system of wild turkeys. Condor. 2008;110:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shuster SM, Wade MJ. Mating systems and strategies. Princeton University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krakauer AH. Kin selection and cooperative courtship in wild turkeys. Nature. 2005;434:69–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West SA, Buckling A. Cooperation, virulence and siderophore production in bacterial parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 2003;270:37–44. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner PE, Chao L. Prisoner’s dilemma in an RNA virus. Nature. 1999;398:441–443. doi: 10.1038/18913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guyon P, et al. Transformed plants producing opines specifically promote growth of opine-degrading agrobacteria. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 1993;6:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon DM, et al. An experimental test of the rhizopine concept Rhizobium meliloti. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1996;62:3991–3996. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.3991-3996.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hillesland KL, et al. Ecological variables affecting predatory success in Myxococcus xanthus. Microbial Ecology. 2007;53:571–578. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kümmerli R, et al. Limited dispersal, budding dispersal, and cooperation: an experimental study. Evolution. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00548.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White CE, Winans SC. Cell-cell communication in the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Series B. 2007;362:1135–1148. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bever JD, Simms EL. Evolution of nitrogen fixation in spatially structured populations of Rhizobium. Heredity. 2000;85:366–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denison RF. Legume sanctions and the evolution of symbiotic cooperation by rhizobia. American Naturalist. 2000;156:567–576. doi: 10.1086/316994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simms EL, Bever JD. Evolutionary dynamics of rhizopine within spatially structured rhizobium populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 1998;265:1713–1719. [Google Scholar]

- 51.West SA, et al. Sanctions and mutualism stability: why do rhizobia fix nitrogen? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 2002;269:685–694. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiers ET, Denison RF. Sanctions, cooperation, and the stability of plant-rhizosphere mutualisms. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics. 2008;39:215–236. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bever JD, et al. Preferential allocation to beneficial symbiont with spatial structure maintains mycorrhizal mutualism. Ecology Letters. 2009;12:13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitlock MC, McCauley DE. Some population genetic consequences of colony formation and extinction: genetic correlations within founding groups. Evolution. 1990;44:1717–1724. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gardner A, West SA. Demography, altruism, and the benefits of budding. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2006;19:1707–1716. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wade MJ, McCauley DE. Extinction and recolonization: their effects on the genetic differentiation of local populations. Evolution. 1988;42:995–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1988.tb02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodnight CJ, et al. Contextual analysis of models of group selection, soft selection, hard selection, and the evolution of altruism. American Naturalist. 1992;140:743–761. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharp SP, et al. Dispersal of sibling coalitions promotes helping among immigrants in a cooperatively breeding bird. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B. 2008;275:2125–2130. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ingvarsson PK, Giles BE. Kin-structured colonization and small-scale genetic differentiation in Silene dioica. Evolution. 1999;53:605–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seppa P, et al. Colony fission affects kinship in a social insect. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2008;62:589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peeters C, Ito F. Colony dispersal and the evolution of queen morphology in social hymenoptera. Annual Review of Entomology. 2001;46:601–630. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Biofilm formation and dispersal and the transmission of human pathogens. Trends in Microbiology. 2005;13:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urban MC, et al. The evolutionary ecology of metacommunities. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2008;23:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saccheri I, Hanski I. Natural selection and population dynamics. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2006;21:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Molofsky J, Bever JD. A new kind of ecology? Bioscience. 2004;54:440–446. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dudley SA, File AL. Kin recognition in an annual plant. Biology Letters. 2007;3:435–438. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Donohue K. Density-dependent multilevel selection in the great lakes sea rocket. Ecology. 2004;85:180–191. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maclean RC, Brandon C. Stable public goods cooperation and dynamic social interactions in yeast. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2008;21:1836–1843. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson DS, Dugatkin LA. Group selection and assortative interactions. American Naturalist. 1997;149:336–351. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamilton WD. Altruism and related phenomena, mainly in the social insects. Annual Review of Ecological Systematics. 1972;3:192–232. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frank SA. Foundations of social evolution. Princeton University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wade MJ. Kin selection: its components. Science. 1980;210:665–667. doi: 10.1126/science.210.4470.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Price GR. Extension of covariance selection mathematics. Annals of Human Genetics. 1972;35:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1957.tb01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goodnight CJ. Multilevel selection: the evolution of cooperation in non-kin groups. Population Ecology. 2005;47:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheverud JM. Evolution by kin selection: a quantitative genetic model illustrated by maternal performance in mice. Evolution. 1984;38:766–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Queller DC. A general model for kin selection. Evolution. 1992;46:376–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1992.tb02045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ingvarsson PK. Group selection in density-regulated populations revisited. Evolutionary Ecology Research. 1999;1:527–536. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bartz SH, Holldobler B. Colony founding in Myrmecocystus mimicus Wheeler (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) and the evolution of foundress-associations. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1982;10:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peer K, Taborsky M. Delayed dispersal as a potential route to cooperative breeding in ambrosia beetles. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2007;61:729–739. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Odling-Smee FJ, et al. Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution. Princeton University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]