Abstract

AIMS

To examine the association of connecting peptide (C-peptide) and the risks of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes among women with a history of gestational diabetes.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study of 1263 women with a history of gestational diabetes was carried out at 1–5 years after delivery in Tianjin, China. Logistic regression was used to assess the associations of C-peptide and the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes.

RESULTS

The multivariable-adjusted odds ratios based on different levels of C-peptide (0–33%, 34–66%, 67–90%, and >90% as C-peptide cutpoints) were 1.00, 1.93 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.85–4.39), 2.49 (95% CI 1.06–5.87), and 3.88 (95% CI 1.35–11.1) for diabetes (P for trend <0.0001), and 1.00, 1.66 (95% CI 1.18–2.36), 2.38 (95% CI 1.56–3.62) and 2.35 (95% CI 1.27–4.37) for pre-diabetes (P for trend <0.0001), respectively. Restricted cubic splines models showed a positive linear association of C-peptide as a continuous variable with the risks of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes. The positive association was significant when stratified by healthy weight and overweight participants.

CONCLUSIONS

We found a positive association between serum C-peptide levels and the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes among Chinese women with a history of gestational diabetes. Our finding suggested that elevated C-peptide levels may be a predictor of diabetes and pre-diabetes.

Keywords: diabetes, pre-diabetes, C-peptide, gestational diabetes mellitus

1. Introduction

Connecting peptide (C-peptide), produced in equal amounts to insulin, is known to be a useful marker of beta-cell function and can be used to assess endogenous insulin secretion 1. In clinical practice, it helps to differentiate between type 1 and type 2 diabetes 2, detect absolute insulin deficiency 3–5, and determine diabetes prognosis 3, 6–9. Recently, several studies have suggested that C–peptide is not only an insulin secretion marker but also a biologically active peptide 10. C-peptide may provide much more important information for choosing therapies, but very few studies have conducted to identify factors that might predict the diabetes, especially in certain special populations, such as women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). It is unclear if serum C-peptide is more effective in the prediction of diabetes compared to the insulin application recommendations.

GDM, which is regarded as impaired glucose intolerance and first diagnosed during pregnancy, complicates 7% of pregnancies in the U.S. and Asian women have a higher risk for GDM compared with other groups11–15. The prevalence of GDM has increased from 2.4% in 1999 to 8.2% in 2012 in urban China 16 by using the WHO’s criteria17. Resolution of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) is usually accompanied by delivery of the baby. In the past years, many studies have shown that women with a history of GDM have a significantly increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes later in life 18, 19. However, very few studies have observed the risk of elevated serum C-peptide on the development of diabetes after delivery among women with GDM. Lappas M et al. 20 reported that postpartum C-peptide was a significant risk factor for later type 2 diabetes in women with a history of GDM, but the study was limited by the small sample size. Our study aims to examine the association between plasma C-peptide and the risks of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes among 1263 women with a history of GDM.

2. Methods

2.1 Study population

A cross-sectional study of 1263 women with a history of GDM at 1–5 years after delivery was performed using the survey data from the Tianjin Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Program. The program is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted among GDM women living in six urban districts in Tianjin, China21. Pregnant women from six urban districts in Tianjin had been enrolled in a universal screening for GDM from 1999 to 2008. The average proportion of screened pregnancies was over 91%. All pregnant women participated in a 1-h 50-g glucose screening test (GCT) at 26–30 weeks’ gestation. Those who had a glucose reading ≥7.8 mmol/L were invited to undergo a 75-g 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)16. We used the World Health Organization (WHO)’s criteria 17 to define GDM. Women verified by a 75-g glucose 2-h OGTT test as either diabetes (a fasting glucose ≥7 mmol/L or 2-h glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L) or IGT (2-h glucose ≥7.8 mmol/L and <11.1 mmol/L) were regarded as having GDM. A total of 4644 women with GDM from 2005 to 2009 were invited to join the program. Among them, 1,263 (27.2%) GDM women were eligible and finished the visit during August 2009 and July 2011. No differences were found between the returned and unreturned GDM women in age, fasting glucose, 2-h glucose, and the prevalence of IGT and diabetes at 26–30 gestational weeks’ OGTT22. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

All participants completed a self-administered questionnaire at the survey. The questionnaire included the women’s history of GDM (fasting and 2-h glucose in the OGTT copied from the center lab and the treatment of GDM during the pregnancy), socio-demographics (age, marital status, education , income and occupation), family history (diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer), dietary habits (participants completed a 3-day 24-h food record with the instruction of a dietician), physical activity including sedentary activities, frequency and duration of leisure time, other habits such as alcohol intake, smoking habits and passive smoking status. The physical examination mainly included the measurement of height, body weight, and blood pressure, and a blood test. The body weight and height for all participants were measured by specially trained research doctors using a standardized protocol. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm, and weight was rounded to the nearest 0.1 kilogram. BMI for all participants was calculated by dividing their weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. BMI was categorized as <24, 24 –27.9, and ≥28 kg/m2 based on the Chinese BMI cut-offs 2323. All participants’ venous blood samples were collected before fasting at least 12 hours and 2 hours after the ingestion of 75g glucose. Fasting plasma C-peptide was measured on an automatic analyzer (Siemens ADVIA centaur XP).

2.2 Definition of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes after delivery

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA)’s criteria, type 2 diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L and/or 2-h glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L 24. Pre-diabetes was defined as either impaired fasting glucose (IFG, fasting glucose ≥5.6 mmol/L and <7.0 mmol/L), or IGT (2-h glucose ≥7.8 mmol/L and <11.1 mmol/L) 24. Those using antidiabetic drugs in the examination were also included into the type 2 diabetes cases.

2.3 Statistical analysis

C-peptide was analyzed separately as a continuous variable, the four categories (≤33%, 34–66%, ≥67–90%, and >90%), or a binary variable grouped by median. We chose to analyze C-peptide as four categories because we first divided participants into three groups based on C-peptide levels (tertiles: ≤33%, 34–66%, ≥67%). Then we found the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes probably increased as C-peptide level increased, and added a new group (>90%) to make balance of study samples and incident cases of diabetes and prediabetes in each group. The means and standard deviations (SD) or proportions of the demographic and lifestyle data were summarized by the four categories of C-peptide. Comparisons among groups including continuous measures and categorical measures were respectively analyzed by One-way ANOVA and χ2 tests. Logistic regression models were performed to assess the association between C-peptide concentrations and the risks of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes. The different categories of C-peptide were included in the models (as dummy variables) and the significance of the trend over different categories was tested in the same models with the median of each category as a continuous variable. The analyses were first adjusted for age (Model 1), and then for years after delivery, education, family income, family history of diabetes, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, leisure-time physical activity, sitting time, total energy intake, dietary fiber intake, energy percent of monounsaturated fat, energy percent of polyunsaturated fat, and energy percent of saturated fat intake (Model 2), and further for BMI (Model 3) and fasting insulin (Model 4). In order to determine the mediate effect of BMI between C-peptide and diabetes risk, we utilized a mediation analysis. The P-values were two–sided and the statistical significance was set at P<0.05. All statistical analyses used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA) The mediation analysis was conducted by Sobel Test and Bootstrapping Method with the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

3. Results

The characteristics of the study participants based on different levels of C-peptide are shown in Table 1. In the study population of 1263 women with a history of GDM, 401 (32.0%) and 83 (6.6%) women were diagnosed as pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes, respectively. Plasma C-peptide values of all GDM women ranged from 0.20 to 6.52 mg/dl with a mean ± SD of 1.38 ± 0.65 mg/dl. BMI was positively associated with the plasma C-peptide level. Age-adjusted partial correlation was 0.77 for C-peptide and fasting insulin (P <0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects by C-peptide levels

| Characteristics | C-peptide levels

|

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–33% | 34–66% | 67–90% | >90% | ||

| Age, y | 32.6 ± 3.20 | 32.4 ± 3.60 | 32.2 ± 3.77 | 31.6 ± 3.51 | 0.197 |

| Duration after delivery, y | 2.23 ± 0.86 | 2.26 ± 0.87 | 2.38 ± 0.90 | 2.34 ± 0.87 | 0.104 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.0 ± 2.83 | 23.6 ± 3.26 | 26.1 ± 3.67 | 28.4 ± 4.12 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index categories, % | <0.0001 | ||||

| <24 kg/m2 | 79.2 | 59.7 | 29 | 32.7 | |

| 24 –27.9 kg/m2 | 18.4 | 30.8 | 44.3 | 33.0 | |

| ≥28 kg/m2 | 2.4 | 9.5 | 26.7 | 34.3 | |

| Education, % | 0.092 | ||||

| <13 years | 18.4 | 23.1 | 25.3 | 27.0 | |

| ≥13 to <16 years | 72.7 | 68.3 | 69.3 | 68.2 | |

| ≥16 years | 8.9 | 8.6 | 5.3 | 4.8 | |

| Income, % | 0.007 | ||||

| <5,000 Yuan/month | 22.0 | 26.8 | 33.0 | 34.9 | |

| 5,000–7,999 Yuan/month | 41.6 | 36.4 | 31.3 | 36.5 | |

| ≥8,000 Yuan/month | 36.4 | 36.8 | 35.7 | 28.6 | |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 29.7 | 41.6 | 35.5 | 38.1 | 0.004 |

| Current smoking, % | 1.4 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.612 |

| Passive smoking, % | 49.5 | 54.4 | 58.0 | 56.3 | 0.132 |

| Current alcohol drinkers, % | 19.4 | 23.4 | 22.3 | 23.0 | 0.528 |

| Leisure time physical activity, % | |||||

| 0 min/day | 79.0 | 77.5 | 79.7 | 80.1 | |

| 1–29 min/day | 19.6 | 19.6 | 18.7 | 16.7 | 0.729 |

| ≥30 min/day | 1.4 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 2.2 | |

| Sitting time at home, h/day | 3.02 ± 2.05 | 3.17 ± 1.93 | 3.42 ± 2.27 | 3.36 ± 2.28 | 0.008 |

| Dietary intakes a | |||||

| Energy consumption, kcal/day | 1702 ± 441 | 1691 ± 396 | 1671 ± 445 | 1715 ± 561 | 0.746 |

| Fiber, g/day | 10.7± 4.29 | 10.4 ± 4.00 | 10.2 ± 3.97 | 10.3 ± 4.54 | 0.446 |

| Fat, % energy | 33.4 ± 6.23 | 33.5 ± 6.30 | 33.4 ± 6.42 | 33.8 ± 6.96 | 0.930 |

| Saturated fat, % energy | 7.97 ± 2.08 | 8.02 ± 1.99 | 7.94 ± 2.09 | 7.98 ± 2.33 | 0.956 |

| Monounsaturated fat, % energy | 13.5 ± 2.66 | 13.5 ± 2.78 | 13.6 ± 2.80 | 13.7 ± 2.92 | 0.780 |

| Polyunsaturated fat, % energy | 11.94 ± 2.92 | 12.0 ± 3.02 | 11.9 ± 2.88 | 12.1 ± 3.36 | 0.834 |

The cutpoints were 1.01, 1.49, and 2.16 ng/ml.

Data are means ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. One-Way ANOVA and χ2 tests were used to assess the four groups.

Dietary intakes are assessed by 3-day 24-h food records.

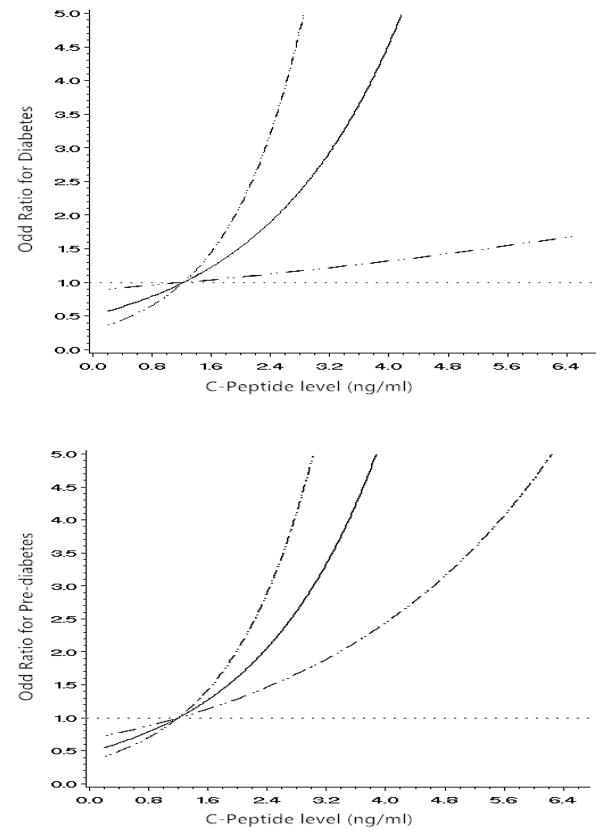

The multivariable-adjusted (age, years after delivery, education, family income, family history of diabetes, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, leisure-time physical activity, sitting time, total energy intake, dietary fiber intake, energy percent of monounsaturated fat, energy percent of polyunsaturated fat, energy percent of saturated fat, and BMI (Model 3) odds ratios based on different levels of C-peptide (0–33%, 34–66%, 67–90%, and >90%) were 1.00, 1.94 (95% CI 0.86–4.41), 2.54 (95%CI 1.11–5.82), and 4.06 (95%CI 1.60–10.3) for type 2 diabetes (P for trend <0.0001), and 1.00, 1.73 (95%CI 1.23–2.44), 2.65 (95%CI 1.81–3.87), and 2.91 (95%CI 1.75–4.84) for pre-diabetes (P for trend < 0.0001), respectively (Table 2). After additional adjustment for fasting insulin (Model 4), these positive associations did not change (P for trend < 0.0001). When C-peptide was considered as a continuous variable, multivariable-adjusted ORs (Model 4) were 1.73 (95% CI 1.10–2.70) for type 2 diabetes and 1.73 (95% CI 1.24–2.43) for pre-diabetes, respectively. The restricted cubic splines models showed a positive linear association of C-peptide as a continuous variable with the risks of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Odds ratios of diabetes and pre-diabetes by C-peptide as a categorized variable and a continuous variable

| No. of participants | No. of cases | Odds Ratio (95% CIs)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| As a continuous variable | 1263 | 83 | 2.51 (1.91, 3.31) | 2.35 (1.77, 3.13) | 1.64 (1.17, 2.28) | 1.73 (1.10, 2.70) |

| As a categorical variable | ||||||

| 0–33% | 418 | 9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 34–66% | 419 | 23 | 2.65 (1.21, 5.80) | 2.47 (1.11, 5.50) | 1.94 (0.86, 4.41) | 1.93 (0.85, 4.39) |

| 67–90% | 300 | 28 | 4.73 (2.20, 10.2) | 4.26 (1.95, 9.35) | 2.54 (1.11, 5.82) | 2.49 (1.06, 5.87) |

| >90% | 126 | 23 | 10.4 (4.67, 23.2) | 9.35 (4.07, 21.5) | 4.06 (1.60, 10.3) | 3.88 ( 1.35, 11.1) |

| P for trend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Pre-diabetes | ||||||

| As a continuous variable | 1180 | 401 | 2.66 (2.13, 3.31) | 2.62 (2.10, 3.28) | 1.86 (1.44, 2.40) | 1.73 (1.24, 2.43) |

| As a categorical variable | ||||||

| 0–33% | 396 | 76 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 34–66% | 383 | 123 | 2.00 (1.44, 2.79) | 1.98 (1.42, 2.77) | 1.73 (1.23, 2.44) | 1.66 (1.18, 2.36) |

| 67–90% | 286 | 138 | 3.98 (2.82, 5.60) | 3.93 (2.77, 5.57) | 2.65 (1.81, 3.87) | 2.38 (1.56, 3.62) |

| >90% | 115 | 64 | 5.40 (3.46, 8.45) | 5.27 (3.35, 8.30) | 2.91 (1.75, 4.84) | 2.35 (1.27, 4.37) |

| P for trend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

Model 1, adjusted for age; model 2, adjusted for age, years after delivery, education, family income, family history of diabetes, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, leisure-time physical activity, sitting time, total energy intake, dietary fiber intake, energy percent of monounsaturated fat, energy percent of polyunsaturated fat, and energy percent of saturated fat; model 3, adjusted for variables in model 2 and body mass index; model 4, adjusted for variables in model 3 and fasting insulin.

Figure 1.

Odds ratios (solid line) and 95% confidence interval (dashed lines) for type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes according to different levels of C-peptide among women with a history of GDM. Adjusted for age, years after delivery, education, family income, family history of diabetes, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, leisure-time physical activity, sitting time, total energy intake, dietary fiber intake, energy percent of monounsaturated fat, energy percent of polyunsaturated fat, energy percent of saturated fat, body mass index and insulin.

We utilized the mediation analysis for BMI on the association of C-peptide with the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes. The direct effect of C-peptide on diabetes risk was 0.43, SE = 0.14, P=0.002; the indirect effect of C-peptide on diabetes risk mediated through BMI was 0.28, SE = 0.068, p<0.001. In pre-diabetes analyses, the direct effect of C-peptide on pre-diabetes risk was 0.39, SE = 0.08, p<0.001; the mediate effect for BMI on the association of C-peptide with pre-diabetes risk was 0.22, SE = 0.004, p<0.001. BMI was the intermediator of C-peptide with the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes and it had part of the mediation effect and explained 39.4% of the total effect in diabetes risk and 36.1% of the total effect in pre-diabetes risk, respectively.

We also calculated the odds ratios of diabetes and pre-diabetes based on different levels of C-peptide and BMI (normal weight–BMI <24 kg/m2 and overweight - BMI ≥24 kg/m2). The positive associations of C-peptide level with the risks of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes were consistent among normal weight and overweight women with GDM (all P for trend <0.05) (Table 3). There were no statistically significant interactions of C-peptide and BMI on the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes (all P>0.1).

Table 3.

Odds ratios of diabetes and pre-diabetes based on different levels of C-peptide and body mass index

| C-peptide levels

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–33% | 34–66% | 67–90% | >90% | P for trend | |

| Diabetes | |||||

| Body mass index <24 kg/m2 | |||||

| No. of participants/cases | 228/4 | 227/4 | 160/5 | 68/5 | |

| Odd ratios (95% CIs) | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.18, 3.86) | 1.92 (0.44, 8.42) | 6.98 (1.16, 41.9) | 0.0180 |

| Body mass index ≥24 kg/m2 | |||||

| No. of participants/cases | 193/11 | 193/22 | 137/17 | 57/15 | |

| Odd ratios (95% CIs) | 1.00 | 1.98 (0.88, 4.45) | 2.19 (0.91, 5.28) | 5.30 (1.61, 17.49) | 0.0040 |

| Pre-diabetes | |||||

| BMI <24 kg/m2 | |||||

| No. of participants/cases | 224/37 | 215/49 | 163/60 | 63/25 | |

| Odd ratios (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.46 (0.88, 2.41) | 2.34 (1.34, 4.09) | 2.73 (1.23, 6.08) | 0.0010 |

| BMI≥24 kg/m2 | |||||

| No. of participants/cases | 174/52 | 166/78 | 124/69 | 51/31 | |

| Odd ratios (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.80 (1.09, 2.96) | 2.42 (1.35, 4.33) | 2.28 (0.92, 5.69) | 0.0018 |

Adjusted for age, years after delivery, education, family income, family history of diabetes, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, leisure-time physical activity, sitting time, total energy intake, dietary fiber intake, energy percent of monounsaturated fat, energy percent of polyunsaturated fat, energy percent of saturated fat, and fasting insulin.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we found positive associations of plasma C-peptide with the risks of postpartum type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes among women with a history of GDM independent of major diabetes risk factors including BMI and fasting insulin.

The present study demonstrated that the C-peptide level progressively increased from women with normal glucose through those with pre-diabetes and diabetes. The higher concentrations of C-peptide were associated with an increased risk of pre-diabetes and diabetes. While the clinical role of C-peptide has not been routinely recommended as a measure of risk for type 2 diabetes, C-peptide has been advocated as a tool to screen people at a high risk of diabetes. C-peptide has been mainly used in differentiating Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes and the treatment change in insulin treated patients in the clinic. Although the present study indicated the strong correlation between C-peptide levels and fasting insulin, we also found a graded positive association between C-peptide values and the risks of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes independent of fasting insulin and BMI and other major diabetes risk factors. Our current observations support the report of Chailurkit, et al25. Chailurkit, et al indicated that C-peptide levels progressively increased from the normal glucose tolerance to the diabetic subjects. They found that serum C-peptide was more strongly associated with newly diagnosed diabetes than insulin, and was an independent risk factor associated with newly diagnosed diabetes in Thais.

Until now, very few studies have assessed the association between C-peptide levels and diabetes risk among women with a history of GDM. Two studies have assessed this association but with small study sample sizes. Lappas et al. found fasting plasma glucose during pregnancy and post-partum, and post-partum C-peptide levels were significant risk factors for the development of postpartum type 2 diabetes among 118 women with a history of GDM20. However, Lin et al. 26 indicated that there were no significant differences in fasting C-peptide levels at least six weeks after delivery among 127 prior GDM women with normal glucose tolerance, abnormal glucose tolerance, and diabetes after delivery. The present study included 1263 women with a history of GDM and found a positive association between serum C-peptide levels and the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes among Chinese women with a history of gestational diabetes which was independent of other major diabetes risk factors including BMI and fasting insulin.

Obesity is known to be a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes. The central role of obesity has been shown to mediate a systemic inflammatory response with potential downstream insulin resistance and glucose dysregulation27, 28. The body fat has been reported to compensate for impaired beta cell function22. A recent study by Lin et al. noted that pre-pregnancy obesity and excessive weight gain from pre-pregnancy to postpartum increased postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes risks among GDM women 26. The present study showed both BMI and C-peptide levels were important risk factors of diabetes in women with GDM, and the significant and positive associations were independent of each other. In addition, we found that the positive associations between plasma C-peptide with the risks of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes persisted among normal weight and overweight GDM women. Thus, we thought that C-peptide independently contributed to the increased risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes in GDM women.

There was an advantage of the present study: the large sample size of women with GDM. Another important strength of our study was that diagnoses of diabetes and pre-diabetes were based on a postpartum 2-hour 75 g OGTT. Limitations of this study included the cross-sectional nature of the study and only GDM participants but lacking the normal glucose participants as the control group.

5. Conclusions

We found a positive association between plasma C-peptide levels and the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes among Chinese women with a history of GDM. More studies are needed to confirm our results. Our finding suggested that elevated C-peptide levels may be a predictor of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes among GDM women.

Highlights.

The association of C-peptide and the risks of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes among women with a history of GDM was examined.

The analysis showed a positive association between plasma C-peptide levels and the risks of diabetes and pre-diabetes among Chinese women with a history of GDM.

It suggested that elevated C-peptide levels may be a predictor of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes among GDM women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant from European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD)/Chinese Diabetes Society (CDS)/Lilly programme for Collaborative Research between China and Europe, Tianjin Women’s and Children’s Health Center, and Tianjin Public Health Bureau. Dr. Hu was supported by grant from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DK100790. We would also like to appreciate all families for participating in the Tianjin Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Program.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jones AG, Hattersley AT. The clinical utility of C-peptide measurement in the care of patients with diabetes. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2013;30(7):803–817. doi: 10.1111/dme.12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger B, Stenstrom G, Sundkvist G. Random C-peptide in the classification of diabetes. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation. 2000;60(8):687–693. doi: 10.1080/00365510050216411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steffes MW, Sibley S, Jackson M, Thomas W. Beta-cell function and the development of diabetes-related complications in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes care. 2003;26(3):832–836. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besser RE, Jones AG, McDonald TJ, Shields BM, Knight BA, Hattersley AT. The impact of insulin administration during the mixed meal tolerance test. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2012;29(10):1279–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effect of intensive therapy on residual beta-cell function in patients with type 1 diabetes in the diabetes control and complications trial. A randomized, controlled trial. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Annals of internal medicine. 1998;128(7):517–523. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-7-199804010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sari R, Balci MK. Relationship between C peptide and chronic complications in type-2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(8):1113–1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panero F, Novelli G, Zucco C, et al. Fasting plasma C-peptide and micro- and macrovascular complications in a large clinic-based cohort of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes care. 2009;32(2):301–305. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inukai T, Matsutomo R, Tayama K, Aso Y, Takemura Y. Relation between the serum level of C-peptide and risk factors for coronary heart disease and diabetic microangiopathy in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 1999;107(1):40–45. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1212071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bo S, Cavallo-Perin P, Gentile L, Repetti E, Pagano G. Relationship of residual beta-cell function, metabolic control and chronic complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta diabetologica. 2000;37(3):125–129. doi: 10.1007/s005920070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahren J, Ekberg K, Jornvall H. C-peptide is a bioactive peptide. Diabetologia. 2007;50(3):503–509. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0559-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Chen L, Xiao K, et al. Increasing incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Louisiana, 1997–2009. Journal of women's health (2002) 2012;21(3):319–325. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara A, Kahn HS, Quesenberry CP, Riley C, Hedderson MM. An increase in the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: Northern California, 1991–2000. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004;103(3):526–533. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000113623.18286.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabelea D, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hartsfield CL, Bischoff KJ, Hamman RF, McDuffie RS. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) over time and by birth cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM Screening Program. Diabetes care. 2005;28(3):579–584. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu SY, Abe K, Hall LR, Kim SY, Njoroge T, Qin C. Gestational diabetes mellitus: all Asians are not alike. Preventive medicine. 2009;49(2–3):265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S103–105. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang F, Dong L, Zhang CP, et al. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Chinese women from 1999 to 2008. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2011;28(6):652–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 1998;15(7):539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchanan TA. Pancreatic B-cell defects in gestational diabetes: implications for the pathogenesis and prevention of type 2 diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2001;86(3):989–993. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2009;373(9677):1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lappas M, Jinks D, Ugoni A, Louizos CC, Permezel M, Georgiou HM. Post-partum plasma C-peptide and ghrelin concentrations are predictive of type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Journal of diabetes. 2015;7(4):506–511. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu G, Tian H, Zhang F, et al. Tianjin Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Program: study design, methods, and 1-year interim report on the feasibility of lifestyle intervention program. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2012;98(3):508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H, Zhang C, Zhang S, et al. Prepregnancy body mass index and weight change on postpartum diabetes risk among gestational diabetes women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2014;22(6):1560–1567. doi: 10.1002/oby.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou B. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2002;23(1):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes care. 2005;28:S37–S42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.suppl_1.s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chailurkit LO, Jongjaroenprasert W, Chanprasertyothin S, Ongphiphadhanakul B. Insulin and C-peptide levels, pancreatic beta cell function, and insulin resistance across glucose tolerance status in Thais. Journal of clinical laboratory analysis. 2007;21(2):85–90. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin CH, Wen SF, Wu YH, Huang YY, Huang MJ. The postpartum metabolic outcome of women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Chang Gung medical journal. 2005;28(11):794–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, Raif N, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B. C-reactive protein and gestational diabetes: the central role of maternal obesity. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;88(8):3507–3512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrannini E, Camastra S, Gastaldelli A, et al. beta-cell function in obesity: effects of weight loss. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S26–33. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]