Abstract

Objectives

The advancement of microfluidic technology has facilitated the simulation of physiological conditions of the microcirculation, such as oxygen tension, fluid flow, and shear stress in these devices. Here, we present a micro-gas exchanger integrated with microfluidics to study red blood cell (RBC) adhesion under hypoxic flow conditions mimicking post-capillary venules.

Methods

We simulated a range of physiological conditions and explored RBC adhesion to endothelial or sub-endothelial components (fibronectin, FN, or laminin, LN). Blood samples were injected into microchannels at normoxic or hypoxic physiological flow conditions. Quantitative evaluation of RBC adhesion was performed on 35 subjects with homozygous sickle cell disease (SCD).

Results

Significant heterogeneity in RBC adherence response to hypoxia was seen among SCD patients. RBCs from a hypoxia enhanced adhesion population showed a significantly greater increase in adhesion compared to RBCs from a hypoxia non-enhanced adhesion population, for both FN and LN.

Conclusions

The approach presented here enabled the control of oxygen tension in blood during microscale flow and the quantification of RBC adhesion in a cost-efficient and patient-specific manner. We identified a unique patient population in which RBCs showed enhanced adhesion in hypoxia in vitro. Clinical correlates suggest a more severe clinical phenotype in this subgroup.

I. INTRODUCTION

Oxygen tension of the cell microenvironment is one of the most critical parameters to mimic physiological conditions in vitro due to its effect on cell behavior and vital functioning.1, 2 For example, hypoxia, meaning deprivation of oxygen in tissue regions, plays an essential role for the pathophysiology of various diseases such as cancer and sickle cell disease (SCD) by affecting angiogenesis, cell proliferation, glucose metabolism, and cell morphology.3–6 In particular, red blood cells (RBCs) in SCD demonstrate significant differentiation in biophysical properties such as cell morphology, deformability, and adherence in hypoxic environments.7–12 Even though maintaining a physiologically realistic microenvironment is critical for in vitro systems, currently available methods for oxygen tension control present several challenges and shortcomings, including bulky peripheral equipment, labor, and cost-intensive fabrication.2, 13 In the last couple of decades, microfluidic devices have become one of the most powerful platforms for biological and clinical studies due to the unique ability of imposing various physiological conditions, such as hypoxia, at microscale.2, 13–18

Recent advances in microfluidic technologies have enabled the study of various aspects of cellular interactions, cell mechanics, and rheological properties of bulk fluid at the microscale.1, 12, 14, 16, 17, 19–25 The main advantages of microfluidic technologies involve fluid manipulation in microchannels with a plethora of physiological conditions such as flow, oxygen tension, and shear stress requiring only a miniscule volume of reagent and sample.2, 15, 17, 24, 26 Furthermore, microfluidic systems provide a stable and closed-system microenvironment to observe biophysical characteristics at a single-cell level due to microscale geometries.27

Most of the microfluidic devices in the literature have been fabricated via soft lithography by relying on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), which is an optically transparent, gas-permeable, and biocompatible material.2, 19, 24 Though soft-lithography-based systems have grown popular for their superior properties and a relatively rapid prototyping capability, fabrication of these microfluidic devices requires labor-intensive processes and clean room facilities, which is a limiting factor for high-throughput clinical applications.16, 28 Furthermore, oxygen tension control in soft lithographical microfluidic systems such as PDMS based devices have been achieved through the Fickian diffusion of gas molecules through the permeable channel walls from a source channel (filled with gas) to a sample channel, where biological sample is processed.1, 2, 12, 23, 24, 26, 29 This diffusion phenomenon is facilitated by creating multiple channels (source and sample) either in parallel or in stack configuration, requiring complex device design and implementation.

To overcome these challenges, we have designed and developed a lamination-based, low-cost, single-use, easily implementable microfluidic system that can mimic microcirculation and allows oxygen tension control of microscale flow. We utilized an established microfluidic system with which to study adhesion of RBCs to endothelium-associated proteins (fibronectin, FN, and laminin, LN) under hypoxic conditions, which is one of the main driving factors in vaso-occlusion in SCD, thereby mimicking the physiological conditions of the microvasculature in post-capillary venules. Even though deoxygenation has been shown to make RBCs more adherent and less deformable in SCD 6, 30, 31, there is no clinically applicable and low-cost device to analyze RBC adhesion in physiologically relevant conditions, such as flow and hypoxia. In this study, we analyzed adhesion of RBCs in 35 SCD patient blood samples under physiologically relevant hypoxia and flow conditions. In addition, we evaluated the effect of BCAM/Lu receptor (which has been shown to mediate sickle RBC adhesion to LN 32) on increased adhesion of RBCs under hypoxic conditions by blocking the RBC binding sites with anti-BCAM/Lu antibody. Utilizing this new microfluidic platform, we report, for the first time, a heterogeneity in SCD patient blood samples in terms of number of adhered RBCs under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Furthermore, we report an association between SCD patients with or without RBCs that are responsive to hypoxia in terms of adhesion in vitro and clinical phenotypes, including increased LDH and reticulocytosis. We also describe a decreased effect of anti-BCAM/Lu treatment on RBC adhesion in patient blood samples that show hypoxia enhanced adhesion.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Blood collection

Blood samples from SCD and normal subjects were obtained with standard laboratory procedures that had been approved by the institutional review board (IRB). Clinical information, such as medical history and treatment course, were obtained after patients had given informed consent. Upon collection, the samples were treated with an anticoagulant, EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), in vacutainer tubes and were stored at 4 °C. All the experiments were performed within 24 hours of venipuncture, using whole blood samples without any dilution. Clinical data such as hemoglobin phenotype (%), complete blood counts (including white blood cell (WBC) (109/L), RBC (1012/L), absolute neutrophil count (ANC) (106/L), and platelet count (109/L)) reticulocyte count (109/L), and plasma LDH (IU/L) were received from the Adult Sickle Cell Clinic at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UHCMC) in Cleveland, Ohio. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted to identify the proportion of Hb S, Hb F, Hb A, and Hb A2 with the Bio-Rad Variant II Instrument (Bio-Rad, Montreal, QC, Canada) at the Core Laboratory of UHCMC.

Although BCAM/Lu has been shown to mediate sickle RBC adhesion to LN,33–36 there is no controlled in-vitro study in the literature investigating this under hypoxic conditions. For anti-BCAM/Lu blocking experiments, whole blood samples were treated with the antibody of basal cell adhesion molecule, a Lutheran blood group glycoprotein (BCAM/Lu: CD239 Antibody, Novus Biologicals), by adding BCAM/Lu antibody to the whole blood. 50 µL of BCAM/Lu antibody (0.5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to 300 µL of blood samples and were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes.

B. Microfluidic system fabrication

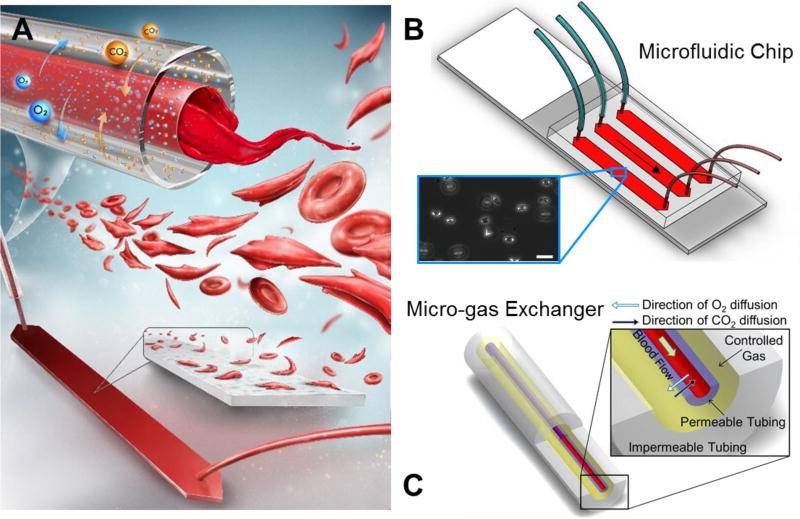

The system was comprised of two main components: the microfluidic chip and the micro-gas exchanger (Fig. 1). The microfluidic chip’s fabrication process involved laser-micromachining (VersaLASER, Universal Laser Systems Inc., Scottsdale, AZ) 3.125 mm thick poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) sheets (McMaster-Carr, Elmhurst, IL) and double-sided adhesive (DSA) (iTapestore, Scotch Plains, NJ) to a desired channel geometry (4 mm width and 25 mm length) with inlet and outlet ports using VersaLASER system (Universal Laser Systems Inc., Scottsdale, AZ). Cut pieces of PMMA and DSA were assembled with Gold Seal glass slide (adhesion coating: APTES, 3-Aminopropyl Triethoxysilane, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Design and fabrication of the microfluidic channels was explained in detail in our previously published work.37–39 To mimic blood vessel wall, microchannels in the chip were functionalized with N-g-Maleimidobutyryloxy succinimide ester (GMBS: 0.28% v/v), and endothelium associated proteins, FN (1:10 dilution with PBS, Sigma Aldrich) and LN (1:10 dilution with PBS, Sigma Aldrich), were immobilized on the channel surface via covalent interactions, ensuring the sustainability of the protein coating under flow conditions.40 After 1.5 hours of incubation at room temperature with either protein, the channels were flushed with bovine serum albumin solution (BSA: 20 mg/ml) and incubated overnight at 4 °C to prevent non-specific binding events.

Figure 1. Single-use micro-gas exchanger integrated with microchannels for oxygen tension control of cell microenvironment.

(A) Blood deoxygenated in the micro-gas exchanger during flow and reached the functionalized microchannels, where the flow conditions were physiologically relevant. The system was applied to SCD blood to observe sickling and adhesion behavior of RBCs. (B) The microfluidic system, composed of three parallel microchannels of 50 µm height, outlet tubing, and micro-gas exchanger inlet tubing, as shown. Inset shows adhered sickle RBC on endothelium associated protein (fibronectin, FN, and laminin, LN) functionalized surface. Scale bar indicates 20 µm of length. (C) The micro-gas exchanger, comprised of two concentric tubing; an inner gas-permeable tubing and an outer gas-impermeable tubing, as shown. Controlled gas flow takes place between the inner and outer tubing; blood flows inside the inner tubing. Deoxygenation of blood occurred due to gas diffusion (5% CO2 and 95% N2) through inner gas-permeable tubing wall. The micro-gas exchanger is single-use, allowing easy adaptation to biological and point-of-care microfluidic systems.

C. Micro-gas exchanger design, fabrication, and operation

To setup the micro-gas exchanger, medical grade gas-permeable silicone tubing (300 µm inner diameter (ID) × 640 µm outer diameter (OD), Silastic Silicone Laboratory Tubing, Dow Corning) was placed inside the impermeable tubing (1600 µm ID × 3200 µm OD, FEP tubing, Cole-Parmer). Permeability of the outer FEP tubing (0.59 Barrer for CO2 1.4 Barrer for O2) (1 Barrer = 10−10 (cm3 O2) cm cm−2 s−1 cmHg−1) and was less than 0.2% of the inner silicone tubing (2000 Barrer for CO2 800 Barrer for O2) for both CO2 and O2. The blood exchanged gases through the permeable tubing wall with 5% CO2 and 95% N2 controlled gas inside the impermeable tubing by diffusion (Fig. 1A), and the normoxic condition was controlled by introducing ambient air into the micro-gas exchanger system. The entire system was designed to be single-use as the cost of material and fabrication was less than $5 per experiment (Table S1).

The silicone tubing was filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Life Technologies) before flowing the blood. All possible points of leakage were sealed with an epoxy glue (5 Minute Epoxy, Devcon) to ensure that there was no diffusion of gas molecules inside the microfluidic chip. The blood was injected with the syringe pump (NE300, New Era Pump Systems) into the system at 18.5 µL/min to fill the tubing and the channel, and at 1.85 µL/min to impose about 1 dyn/cm2 of shear stress, which is in the range of shear stress in postcapillary venules (1–5 dyn/cm2) while flowing in the functionalized microfluidic channel (Fig. 1B). Blood loading took ~2 min each time as the tubing length and flow rate were kept the same in all experiments. After flowing 15 µL of blood, flow cytometry staining buffer (FCSB, 1X) was injected to wash the microchannels at 10 µL/min, which imposed 1 dyn/cm2 of shear stress, making the adhered RBCs visible through the inverted microscope (Olympus IX83) and microscopy camera (EXi Blue EXI-BLU-R-F-M-14-C) for high-resolution images. At least 180 µL of FCSB was used to wash the channels and the images were taken during buffer flow. For the entire procedure, except for control experiments (normoxic conditions), the medium flowing in the channel (blood or wash buffer) was deoxygenated with the micro-gas exchanger (Fig. 1C). Further, in reoxygenation experiments, blood samples were injected into the channel as deoxygenated and, after adhesion of RBCs, reoxygenation was performed in-situ by injecting wash buffer equilibrated with ambient air.

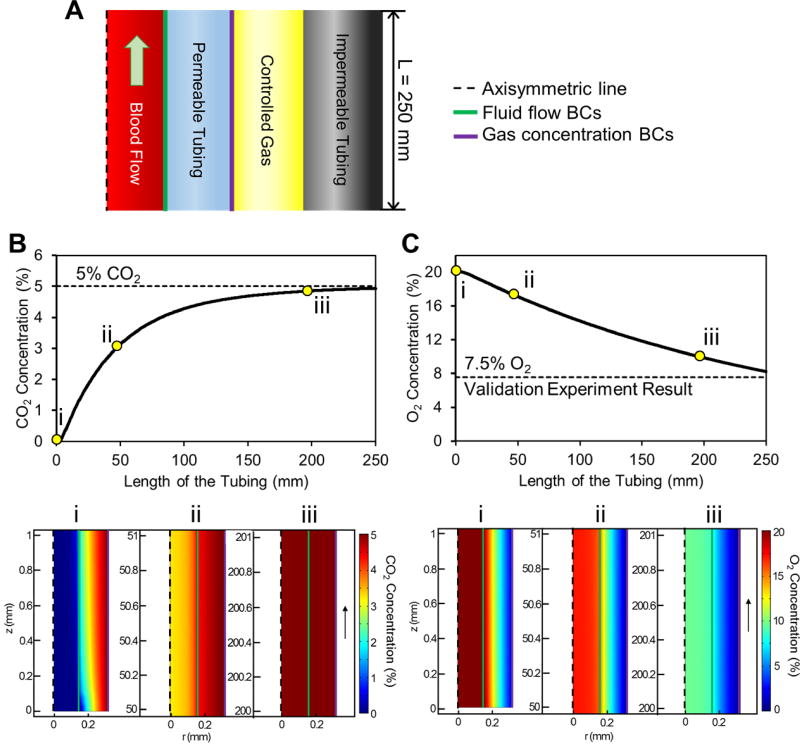

D. Computational modeling and experimental validation of gas diffusion within micro-gas exchanger

Gas diffusion of blood during flow within the micro-gas exchanger was modeled using COMSOL (COMSOL Inc., Burlington, MA) (Fig. 2). Two sets of boundary conditions were chosen to couple laminar flow and gas diffusion through the permeable tubing wall (Fig. 2A). To approximate the diffusion coefficient of CO2 and O2 for the permeable tubing with Fick’s second law of diffusion, the kinematic viscosity of blood was first calculated to be ~0.054 Pa·s at room temperature assuming 2% increase every 1 °C drop.41 Then Hagen-Poiseuille equation was used to approximate the pressure difference (ΔP) along the tubing. As blood was assumed to be Newtonian to simplify the model and shorten the computation time, the simulation result was used as a baseline reference for the experimental setup only (Table S2). The flow of FCSB was also computationally modeled to analyze adequate tubing length and flow rates for constant deoxygenation of the microenvironment.

Figure 2. Computational modeling of flow and gas equilibrium in the micro-gas exchanger.

(A) Schematic for axisymmetric cross section of the micro-gas exchanger shows gas concentration and fluid flow boundary conditions. Gas diffusion rate depends on the flow rate, gas concentration, and tubing length. Micro-gas exchanger length is specifically designed to allow CO2 and O2 equilibrium before blood reaches to the microchannel. (B & C) CO2 and O2 concentration (%) shift in blood flowing within the micro-exchanger tubing. Contour plots (i-iii) on the axisymmetric cross section of blood and permeable tubing in micro-gas exchanger show (B) CO2 and (C) O2 concentration in blood at different lengths of the tubing. CO2 concentration of blood starts to increase as blood flows through the permeable tubing and reaches equilibrium at 5% in 250 mm. O2 concentration of blood reaches 7.5% in 250 mm through the micro-gas exchanger tubing, which corresponds to results obtained in the validation experiments (see Fig. S1 for additional details).

After optimizing the design parameters, such as tubing length, flow rate, and pressure difference, simulation results were validated by measuring the oxygen saturation level of blood (SpO2) with a finger pulse oximeter (OT-99, Clinical Guard) using a model finger.42 The model finger was fabricated by stacking micromachined poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) with double-sided adhesive (DSA) films (Fig. S1A). Specific geometries were chosen to prevent bubble formation and to maximize sensing capabilities requiring ~300 µL of blood. The validation experiment setup was placed at temperature and gas concentration controlled environments to test the in vitro measurements of the finger pulse oximeter (Fig. S1B).

E. Image processing and quantification

Phase contrast images of microfluidic channels were obtained using an Olympus long working distance objective lens (20×/0.45 ph2) and a commercial software (cellSens Dimension, Olympus Life Science Solutions, Center Valley, PA), which provides mosaic patches of a designated area. Microchannel images were processed using Adobe Photoshop software (San Jose, CA) for the quantification of adhered RBCs per unit area (32 mm2) which covers the one third (center) of the channel area.

F. Statistical Analysis

RBC adhesion data were collected from a total of 45 blood samples obtained from 35 patients. For each tested sample, one microchannel was used for RBC adhesion experiment at hypoxic conditions and a second separate channel for adhesion experiment at normoxic conditions. In addition, adhesion data from two more channels were collected for BCAM/Lu blocking experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was utilized (Microsoft Excel, Seattle, WA) with a minimum confidence level of 95% (p < 0.05) to assess and identify statistically significant differences. Since the ANOVA method uses the ratio of two variances to test if a specific factor (e.g., hypoxia) accounts for a significant variation (e.g., RBC adhesion), this test is ideal for statistically comparing the data sets in this study, such as the number of adhered RBCs in response to hypoxia or normoxia. Individual patients’ clinical data such as LDH level, reticulocyte count, Hb F level were compared between hypoxia enhanced and hypoxia non-enhanced groups (Table 1). Bar graphs reported show mean ±standard error of the mean, and the dotted plots show mean lines with p-values from one-way ANOVA test.

Table 1.

Clinical phenotype of the study population based on hypoxia enhancement of red blood cell adhesion to LN (N=23).

| Hypoxia enhanced adhesion (Mean ± St. Err.) |

Hypoxia non-enhanced adhesion (Mean ± St. Err.) |

P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 8 | 15 | - |

| Age | 27.5±2.1 | 37.1±2.4 | 0.0154 |

| WBC (109/L) | 13.7±1.2 | 9.0±1.0 | 0.0078 |

| Absolute Neutrophil Count (106/L) | 8202.5±939.7 | 4803.1±691.2 | 0.0090 |

| Reticulocyte Count (109/L) | 605.3±77.8 | 244.6±77.2 | <0.0001 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (U/L) | 557.0±79.7 | 417.6±77.2 | 0.0128 |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | 2936.6±658.2 | 1383.6±489.6 | 0.0024 |

| Total Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.4±0.8 | 8.8±0.3 | 0.0548 |

| Hemoglobin S (%) | 56.2±6.6 | 72.4±3.6 | 0.0091 |

| Hemoglobin A (%) | 30.7±6.2 | 8.6±3.5 | 0.0004 |

| Hemoglobin F (%) | 3.5±0.8 | 12.3±2.3 | 0.0079 |

Calculated based on one-way ANOVA test.

III. RESULTS

A. Microfluidic platform integrated with the micro-gas exchanger

Microfluidic platform integrated with the micro-gas exchanger was developed to analyze the adhesion behavior of RBCs from SCD patient blood samples in physiological flow and hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1A). The microfluidic chip consisted of three parallel microchannels functionalized with endothelium-associated adhesive glycoproteins, either laminin (LN) or fibronectin (FN), mimicking endothelial wall characteristics (Fig. 1B).32, 37, 38, 43 The fabrication of the chip was achieved by assembling laser-micromachined PMMA sheets and DSA with a Gold Seal glass slide, costing ~$1 per chip as a result (see also materials and methods section). The micro-gas exchanger is composed of a gas permeable inner tubing placed in a concentric way into a gas impermeable outer tubing (Fig. 1C). Blood flow takes place within the inner gas permeable tubing, whereas controlled gas mixture (5% CO2 and 95% N2) flows in the space between inner and outer tubing. The micro-gas exchanger can deoxygenate whole blood samples through gas diffusion across the permeable tubing wall, providing deoxygenated whole blood to microchannels.

Micro-gas exchanger design was optimized by computational analysis followed by experimental validation (Fig. 2 & S1). Based on the computational analyses, length of the micro-gas exchanger was designed to be 250 mm, which provides 5% CO2 and 7.5% O2 concentration at the tubing outlet (Fig. 2 B–C). These results were validated using a model finger integrated with micro-gas exchanger and a pulse oximeter (Fig. S1).42 Blood injected into a model finger using the micro-gas exchanger resulted in a SpO2 of 83% measured with the pulse oximeter, which represents hypoxia. The results from computational and experimental analyses matched when the SpO2 values from validation experiments were converted to percent gas concentration using hemoglobin oxygen dissociation curve.41, 44

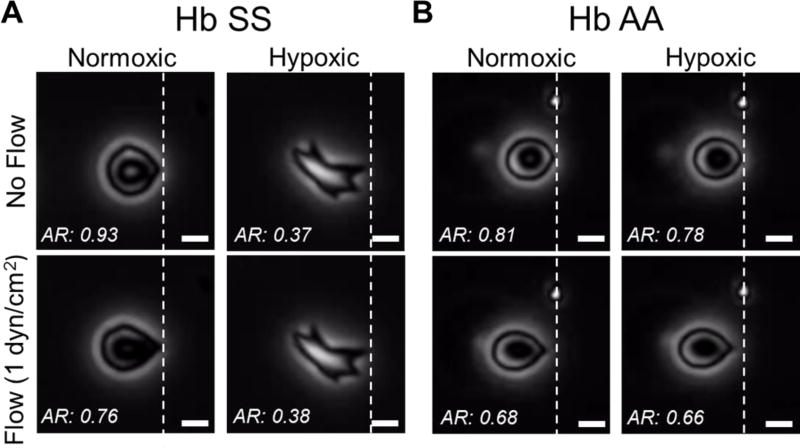

When blood samples from SCD subjects were injected into microchannels through the micro-gas exchanger, we observed single adhered RBCs on functionalized microchannel surfaces (Fig. 3). Adhered RBCs sickled and their aspect ratio decreased upon deoxygenation (hypoxic conditions) from normoxic conditions (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, their deformability, indicated by difference in the aspect ratio in response to applied flow shear stress (1 dyn/cm2), were decreased in hypoxic condition. Though not all adhered RBCs underwent the shown dramatic morphology change (Fig. 3A), all adhered RBCs polymerized and showed decreased deformability when deoxygenated. On the other hand, RBCs from healthy subjects preserved their morphology and deformability in hypoxic condition as expected (Fig. 3B). Of note, adhesion of blood cells other than RBCs was rarely observed, other than platelets. Micro-gas exchanger allows continuous oxygenation-deoxygenation of adhered RBCs in microfluidic channels, which reveals unsickling (Movie S1) and sickling (Movie S2) of RBCs and accompanying biophysical alterations.

Figure 3. Deoxygenation of adhered RBCs in blood samples from SCD (Hb SS) and normal (Hb AA) subjects.

(A) Shown are single adhered HbSS containing RBCs, with (hypoxic) and without (normoxic) deoxygenation, from patients with SCD, under different flow conditions. Under hypoxic conditions, the aspect ratio of sickle RBCs decreased and displayed decreased deformability, defined by changes in aspect ratio in response to fluid flow shear stress application, in comparison with normoxic conditions. (B) Shown are single HbAA containing RBCs, from patients without SCD. Overall, these RBCs showed a preserved morphology and deformability characteristic under hypoxic conditions, with greater deformability than that seen in HbSS-containing RBCs 37,38. The scale bars indicate 5 µm of length.

B. Heterogeneity in RBC adhesion response to hypoxia

We analyzed the number of adhered RBCs in blood samples obtained from 35 SCD patients in hypoxic and normoxic conditions using the microfluidic platform integrated with the micro-gas exchanger. Blood samples from SCD patients showed heterogeneity in increase of adhered RBCs between normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Fig. 4). A subset of patients showed a larger increase in absolute adhesion under hypoxic conditions in both FN and LN experiments (Fig. 4), resulting in a pseudo threshold for number of increased RBCs due to hypoxia of approximately 400 for FN and 5000 for LN. We observed a statistically significant increase in the number of adhered RBCs to LN compared to FN in response to hypoxia (Fig. 4B, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). We clustered blood samples from SCD patients into hypoxia enhanced adhesion (HEA) or hypoxia non-enhanced adhesion (HNA) categories, depending on whether or not RBC adhesion under hypoxic conditions crossed the described pseudo threshold (Fig. 4C) with a significantly greater increase in adhered RBCs to FN or LN in the HEA patient subpopulation (Fig. S2, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). Most patient blood samples tested for FN and LN (4 out of 8 patients) showed parallel responses to hypoxia for both FN and LN. However, due to the significantly greater adhesion response observed in response to hypoxia in LN functionalized microchannels compared to FN functionalized microchannels, further analyses and associations with clinical phenotypes were only performed for patient blood samples tested for LN. Of note, in control experiments performed with normal (Hb AA) blood samples, the change in the number of adhered RBCs between normoxic and hypoxic conditions were negligible for both FN and LN (Fig. S3).

Figure 4. Heterogeneity in RBC adhesion in response to hypoxic microscale blood flow.

(A) Shown are blood samples from different SCD patients, with heterogeneous responses to hypoxia in terms of increase in number of adhered RBCs. Among the analyzed patient blood samples, a subpopulation of patients (HNA) showed a negligible increase in the number of adhered RBCs to FN and LN. Samples from the remaining patients (HEA) displayed a dramatic increase in number of adhered RBCs to FN and LN in response to hypoxia. Colored dots indicate adhered RBCs. (B) Analyzed patient blood samples showed significantly greater increase in number of adhered RBCs to LN compared to FN in response to hypoxia. (N=35) (C) Patients clustered in two subpopulations, HEA and HNA, based on increase in number of adhered RBCs to FN (N=17) and LN (N=26) in response to hypoxic conditions. The HEA patient subpopulation showed significantly greater increase in the number of adhered RBCs with hypoxia compared to HNA patient subpopulation (p<0.05, See Fig. S2). The horizontal lines between individual groups represent a statistically significant difference based on a one-way ANOVA test (P<0.05). Data point cross bars represent the mean. ‘N’ represents the number of subjects.

C. Clinical association with the number of adhered RBCs under hypoxic conditions

Strikingly, HEA and HNA SCD patients displayed statistically significant differences in clinical laboratory values, including HbF and HbA levels, ferritin levels, serum LDH levels, and reticulocyte counts (Fig. 5 and Table 1), with borderline significant changes in total hemoglobin level. The HNA patient population showed significantly greater HbF values, total hemoglobin (borderline significant) and lower LDH levels, absolute reticulocyte counts, ferritin, and HbA, suggesting a more mild clinical phenotype with diminished requirements for red cell transfusions, compared with the HEA patient population (Fig. 5A, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, except for total hemoglobin at P=.055). All HEA patients showed less than 7% HbF. We also compared transfused (>10% HbA) and non-transfused SCD patients, and observed that 7 out of 8 subjects in HEA subpopulation were transfused, whereas only 2 out of 15 subjects in the HNA subpopulation were transfused (Fig. S4 & S5). Furthermore, HEA patients showed significantly greater white blood cell and neutrophil counts than the HNA patient subpopulation (Fig. S5 and Table 1, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA), suggesting greater inflammation in these patients. HEA patients were also significantly younger (<35 years) than HNA patients (Fig. S6 and Table 1, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). Of note, when hypoxia enhanced adhesion was evaluated as a continuous parameter in terms of change in number of adhered RBCs due to hypoxia, there was no statistically significant correlation with different clinical phenotypes.

Figure 5. Association of hypoxic RBC adhesion with clinical phenotypes in SCD.

Patients with HEA RBCs (N=8), compared with HNA RBCs (N=15), showed (A) significantly higher fetal hemoglobin (Hb F) levels (p=0.0079), (B) significantly higher reticulocyte counts (p<0.0001), and (C) significantly higher LDH levels (p=0.0102). The horizontal lines between individual groups represent a statistically significant difference based on a one-way ANOVA test (p<0.05). Data point cross bars represent the mean. ‘N’ represents the number of subjects.

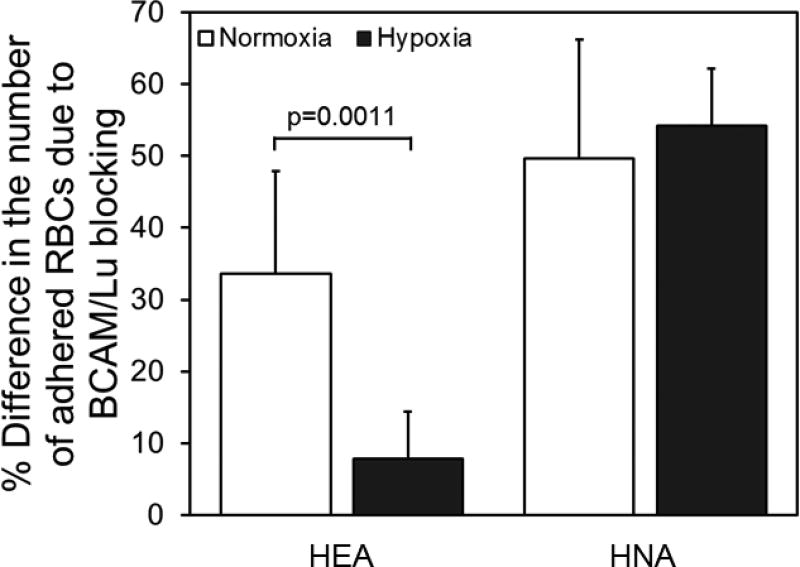

D. Role of BCAM/Lu blocking under hypoxia

To test the role of BCAM/Lu in hypoxic adhesion, we analyzed RBC adhesion in hypoxic and normoxic conditions in whole blood samples treated with anti-BCAM antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in parallel with untreated control samples (Fig. 6). Under normoxic conditions, the BCAM/Lu blocking decreased the number of adhered RBCs by 34% for HEA samples, and 50% for HNA samples. Moreover, BCAM/Lu blocking decreased number of adhered RBCs by 54% for HNA samples under hypoxic conditions. Reduction in the number of adhered RBCs was significantly lower in hypoxic conditions in comparison to normoxic conditions for HEA patient subpopulation (Fig. 6, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). On the other hand, the decrease in the number of adhered RBCs was not significantly different between hypoxic and normoxic conditions for HNA patient subpopulation (Fig. 6, p>0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Figure 6. The effect of BCAM/Lu blocking on RBC adhesion in normoxic and hypoxic conditions for HEA and HNA patient populations.

Shown is mean percent change (+/− standard deviation) in the number of adhered RBCs under hypoxic conditions compared to normoxic conditions in patients with HEA RBCs (N=4) and in patients with HNA RBCs (N=6), following exposure to BCAM/Lu blocking antibodies. The horizontal lines between individual groups represent a statistically significant difference based on a one-way ANOVA test (p<0.05). ‘N’ represents the number of subjects.

IV. DISCUSSION

Oxygen tension control of the cell microenvironment is of utmost importance for in vitro systems aiming to capture physiologically relevant conditions. Microfluidic platforms provide a closed-system environment at the same size scale of the cells along with the capability of fluid flow. However, oxygen control of the cell microenvironment, which has critical implications from angiogenesis to tumor invasion,45–47 in microfluidic systems remains challenging. Soft lithographical techniques such as PDMS based systems, have been widely utilized to control gas concentrations of media in microfluidic systems due to their relatively low-cost and rapid prototyping potential.28 However, these techniques require complicated microfabrication processes, such as casting, baking, aligning, and spin coating in cleanroom facilities, which can take from hours to days to complete fabrication.16 Furthermore, high throughput experiments for larger patient population and single-use clinical application would be challenging. In addition, soft-lithography-based oxygen control system for microfluidic devices is mostly achieved through either stacking structures or placing channels in parallel, further complicating the design and fabrication processes. Also, previously introduced microfluidic systems in the literature for RBC adhesion analyses required specially obtained blood samples, extensive sample manipulation and processing such as packing RBCs, increasing the time needed per experiment.

Here, we present a clinically feasible, cost and labor efficient, and easily implementable microfluidic platform integrated with a single-use, disposable micro-gas exchanger that allows interrogation and manipulation of biological fluids. Our system only requires a simple single-step fabrication process using readily available materials in the industry without the need for clean room facilities and specially processed blood samples, making the system feasible for clinical applications handling mass number of patients. Unlike soft-lithography-based systems, our device does not require processes such as mask designing and aligning for UV exposure, spin coating, plasma bonding, or soft baking. The developed microfluidic platform eliminates the need for intricate channel design and configuration by controlling the oxygen tension of the biological fluid before it reaches the microchannel. Furthermore, by implementing the micro-gas exchanger at the tubing portion, the integrity and function of microchannels are uninterrupted when oxygen tension control is implemented. We utilized this new microfluidic platform to study adhesion of RBCs in blood samples of patients with SCD, in which oxygen tension is considered to play a significant role.48

SCD is one of the most prominent genetic diseases in the world, mainly in Africa.31 About 100,000 people suffer from SCD in the United States alone, where its treatment and care are estimated to cost more than 8 million dollars in the lifespan of a patient.49–51 The origin of the name ‘sickle’ comes from the unique crescent shape of RBCs first discovered in 1910.7, 52, 53 In SCD, hemoglobin molecules polymerize when deoxygenated, due to a point mutation in the beta globin chain, which leads to an increase in stiffness and adherence of RBCs.7, 8 Increased stiffness and adhesion of RBCs result in occlusion of the blood vessels (vaso-occlusion), which is a driving factor for pain crises, organ damage, and early mortality in SCD.6, 30, 31 Even though SCD has been studied for decades, the pathophysiology of the disease is not fully understood due to the complexity of multi-scale systemic interactions.7, 52, 54, 55 For instance, recently, heterogeneous behavior of RBCs was observed in terms of deformability and adhesion strength in SCD and a link between these two biophysical properties was indicated.37, 56 Even though adhesion and hypoxia has been identified as a critical factor in pathophysiology of SCD, there has been no established study of RBC adhesion during physiological flow under hypoxia.7, 8, 57–59

Adhesion behavior of deoxygenated RBCs in SCD has been studied since 1980s. In a seminal paper, Hebbel et al. incubated diluted blood samples from SCD patients on cultured vascular endothelial cells in normoxic and hypoxic conditions, and showed decreased adhesion of sickle RBCs with hypoxia.60 However, in a later work, Setty and Stuart performed a similar study in 1996 and concluded that deoxygenation caused RBCs to adhere more to endothelium, followed by additional studies supporting this result.9, 61, 62 Even though these studies provided significant insight to our understanding of the disease pathophysiology, all were performed in macro-scale and static systems, without the essential physiologically relevant flow conditions. Microfluidic systems have been implemented recently to study the behavior of sickle RBCs in a closed and dynamic system along with physiological flow conditions.11, 23, 29, 37, 38 For example, characterization of rheological differences between oxygenated and deoxygenated SCD blood was performed with a microfluidic device made of PDMS with gas concentration control, albeit lacking endothelium associated proteins and, thus, not incorporating the adhesion aspect.12

The pathophysiology of SCD encompasses biophysical changes in RBC deformability and adhesion, which are dependent on biological components expressed by the microvasculature endothelium, oxygen tension, and flow conditions in microcirculation environment. Therefore, successful incorporation of these physiologically relevant microcirculation environment conditions is crucial to recapitulate and quantitatively assess changes in functional biophysical markers, including cellular deformability and adhesion. Here we report, for the first time, adhesion of RBCs to endothelium-associated proteins, FN and LN, in a closed system mimicking microcirculation with physiologically relevant flow and hypoxic conditions. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study identifying a greater increase in RBC adhesion to LN compared to FN in hypoxic conditions. It can be speculated that increased adhesion stems from changes in RBC surface property that occur over seconds to minutes, in our model the time required for the deoxygenated RBCs to reach the microchannels.

Using the micro-gas control system integrated with microfluidic channels, we showed significant associations between hypoxic RBC adhesion and laboratory measurements of inflammation, iron burden, hemoglobin composition, and hematologic variables. Hb F ameliorates the clinical course of SCD, and decreases hemoglobin polymerization in SCD.7 Hydroxyurea (HU), the only FDA-approved drug for SCD, induces Hb F in RBCs.31 It is plausible that blood samples from patients with low Hb F levels showed deleterious effects from hypoxia, as we see in our studies (Fig. 5a), due to enhanced polymerization. Furthermore, ferritin levels were shown to increase with iron overload caused by blood transfusion in SCD patients.63–65 In parallel to this observation, we found greater serum ferritin levels in HEA subpopulation, of which 7 out of 8 patients were transfused, compared to HNA patients. LDH and reticulocyte counts may signal the presence of intravascular hemolysis, which is pathophysiologically central in SCD.66, 67 Hemolysis and release of heme results in abnormal endothelial activation and inflammation.68–74 Increased levels of soluble adhesion molecules (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), P-selectin, E-selectin, and Von Willebrand factor (VWF)), have been associated with elevated serum LDH levels,66, 72, 75 but a causal association, between hemolysis and abnormal RBC adhesion has not yet been conclusively established in SCD. Here, we identified a unique patient subpopulation whose RBCs, designated as ‘hypoxia-enhanced adhesion’ (HEA) showed enhanced RBC adhesion, to LN and FN, in response to hypoxia in vitro. Patients with HEA RBCs had significantly greater serum LDH levels and reticulocyte counts compared to subjects with HNA RBCs. HEA RBCs may also be more adherent, e. g., to vascular endothelium, in vivo, thereby contributing to further RBC sickling, vaso-occlusion, and hemolysis. The hemolytic profile (high LDH and high absolute reticulocytes) which we see in subjects with HEA RBCs has been associated with debilitating clinical complications in SCD patients, including priapism.76

Adhesion molecules such as BCAM/Lu, VCAM-1, P-selectin, and ICAM-1 that exist in blood vessels have been studied to analyze the abnormal adhesion of RBCs in SCD for decades.9, 32, 48, 77, 78 However, new findings continue to demonstrate the complexity of molecular mechanisms for sickle RBC adhesion. For example, earlier studies involving the expression of adhesion molecules under hypoxia showed contradictory results between in vitro studies and in vivo mouse experiments with endothelial cell-derived VCAM-1.9, 48 BCAM/Lu has been identified as an RBC-expressed adhesion molecule that binds to LN. BCAM/Lu can be phosphorylated during stress, via adrenergic stimulation.32 We examined the contribution made by BCAM/Lu interactions to RBC adhesion, during hypoxia. We found much diminished adhesion to LN by HNA RBCs, but minimal change in adhesion of HEA-RBCs, with hypoxia following exposure to BCAM/Lu blocking antibodies. BCAM/Lu may not contribute significantly to HbSS containing RBC adhesion to LN during hypoxia. Hypoxemia has been associated with clinical syndromes in SCD, including vaso-occlusive crises, priapism, and nocturnal hemoglobin desaturation.79–87 We are in the process of testing whether SCD patients with HEA-RBCs show evidence for more hypoxemia-associated clinical complications. Furthermore, we are currently working on comprehensive predictive models, using larger patient numbers monitored longitudinally, incorporating clinical factors, other complications (priapism, acute chest syndrome, leg ulcers, etc.), and RBC adhesion in normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

In recent years, great advances have been made in the development of translational therapies targeting abnormal cellular adhesion in SCD. For targeting abnormal adhesion of RBCs to activated endothelium, several therapies have been developed, including small molecules (αVβ3)88, low molecular weight heparin (P-Selectin)89, 90, and an oral agent in Phase I/II studies in humans (P-selectin)91–93. A recent publication in the New England Journal of Medicine described a successful randomized trial of p-selectin blockade in patients with sickle cell disease94. Clinicaltrials.gov lists numerous active trials of targeted anti-adhesive therapies, including β-adrenergic receptor blockade (propranolol), anti-selectins (GMI-1070, heparin and its derivatives), as well as anti-inflammatory agents (corticosteroids, regadenoson, and simvastatin). The microfluidic system, along with the micro-gas exchanger described here, may be utilized as a functional in-vitro adhesion model to test efficacy of such therapies, as well as an in-vitro adhesion assay for evaluating patient response to such therapies under physiologically relevant physiological flow and oxygen tension conditions.

Other than directly controlling oxygen tension of the cell microenvironment, chemical agents such as sodium metabisulfite, sodium dithionite, and cobalt chloride have been considered as functional ‘deoxygenators’ for RBCs. These agents have been used to derive hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) as antioxidants imposing molecular effects, which results in sickling of RBCs 10, 95–97, and have mainly been utilized in SCD diagnosis and in testing of anti-sickling drugs.79, 98–103 However, the application of these chemicals is not biomimetic, since deoxygenation does not occur through diffusion with physiological effects such as formation of bicarbonates.

The need for low-cost and easily implementable oxygen tension in microfluidic systems is growing in multiple areas of research. The approach and technique presented here enabled us to control the oxygen tension of the blood in flow and to quantify the adhesion response of RBCs with SCD in a cost-efficient and patient-specific manner, demonstrating the effectiveness of our system. Furthermore, the application of the microfluidic platform integrated with micro-gas exchanger can be utilized in other fields such as neuroscience, stem cells, and cancer.

V. CONCLUSIONS

Mimicking physiologically relevant microenvironments such as oxygen tension and flow is necessary in in vitro experiments for cell and tissue research. We developed a microfluidic platform integrated with micro-gas exchanger that is capable of imposing various physiological conditions, such as flow and hypoxia, in a closed system. The presented approach minimizes the cost of materials and complexity in design and manufacturing of microfluidic channels with precise oxygen tension control. We demonstrated effective oxygen tension control of blood samples from SCD patients and observed increased adhesion of RBCs under hypoxic conditions. By comparing the number of adhered RBCs between normoxic and hypoxic conditions, we reported that there is heterogeneity in patients’ response to hypoxia. Our results associated with the clinical phenotypes that responsive HEA patients had a more severe clinical phenotype, as reflected in lower HbF levels, a higher reticulocyte counts, serum LDH levels, and ferritin levels, reemphasizing the centrality of red cell biological characteristics in determining disease severity in SCD. The microfluidic platform integrated with micro-gas exchanger that we describe here can be used as an in vitro adhesion test for targeted anti-adhesion therapies, for patient selection for clinical trials, and for accurate evaluation of patient response to such therapies under physiologically relevant flow and oxygen tension conditions. Our expectation is that the identification of hypoxia responsive patient subpopulations via a functional biophysical marker, RBC adhesion in physiological flow and oxygen tension, could allow better-guided and more personalized care for patients with SCD. Furthermore, application of the presented microfluidic system can be extended to other areas, where physiologically relevant flow conditions and hypoxic environment are crucial, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, angiogenesis, and stem cell differentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant # 2013126 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute R01HL133574, and National Science Foundation CAREER Award 1552782. Authors acknowledge Cleveland Institute of Art Student, Grace Gongaware for crafting the scientific illustration. U. A. G. would like to thank the Case Western Reserve University, University Center for Innovation in Teaching and Education (UCITE) for the Glennan Fellowship, which supports the scientific art program and the art student internship at Case Biomanufacturing and Microfabrication Laboratory. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of patients and clinicians at Seidman Cancer Center (University Hospitals, Cleveland).

Footnotes

Electronic Supporting Information is available.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M. K., Y. A., J. A. L., and U. A. G. developed the idea, M. K., Y. A., J. A. L., and U. A. G. designed the experiments, M. K. and A. A. performed the experiments, M. K., Y. A., A. A., J. A. L., and U. A. G. analyzed the results, M. K., Y. A., J. A. L., and U. A. G. prepared the figures and the supporting information, M. K., Y. A., J. A. L., and U. A. G. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Peng C-C, Liao W-H, Chen Y-H, Wu C-Y, Tung Y-C. A Microfluidic Cell Culture Array with Various Oxygen Tensions. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:3239–3245. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50388g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan MD, Rexius-Hall ML, Elgass LJ, Eddington DT. Oxygen Control with Microfluidics. Lab on a Chip. 2014;14:4305–4318. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00853g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semenza GL. Targeting Hif-1 for Cancer Therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris AL. Hypoxia - a Key Regulatory Factor in Tumour Growth. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinberg MH. Sickle Cell Anemia, the First Molecular Disease: Overview of Molecular Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Approaches. Thescientificworldjournal. 2008;8:1295–1324. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pritchard KA, Ou JS, Ou ZJ, Shi Y, Franciosi JP, Signorino P, Kaul S, Ackland-Berglund C, Witte K, Holzhauer S, Mohandas N, Guice KS, Oldham KT, Hillery CA. Hypoxia-Induced Acute Lung Injury in Murine Models of Sickle Cell Disease. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2004;286:L705–L714. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00288.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barabino GA, Platt MO, Kaul DK. Sickle Cell Biomechanics. In: Yarmush ML, Duncan JS, Gray ML, editors. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. Vol. 12. 2010. pp. 345–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christoph GW, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. Understanding the Shape of Sickled Red Cells. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88:1371–1376. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Setty BNY, Stuart MJ. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Is Involved in Mediating Hypoxia-Induced Sickle Red Blood Cell Adherence to Endothelium: Potential Role in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 1996;88:2311–2320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asakura T, Mayberry J. Relationship between Morphologic Characteristics of Sickle Cells and Method of Deoxygenation. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1984;104:987–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du E, Diez-Silva M, Kato GJ, Dao M, Suresh S. Kinetics of Sickle Cell Biorheology and Implications for Painful Vasoocclusive Crisis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:1422–1427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424111112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood DK, Soriano A, Mahadevan L, Higgins JM, Bhatia SN. A Biophysical Indicator of Vaso-Occlusive Risk in Sickle Cell Disease. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alapan Y, Hasan MN, Shen R, Gurkan UA. 3d Printing Based Hybrid Manufacturing of Microfluidic Devices. Journal of Nanotechnology in Engineering and Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1115/1.4031231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta K, Kim D-H, Ellison D, Smith C, Kundu A, Tuan J, Suh K-Y, Levchenko A. Lab-on-a-Chip Devices as an Emerging Platform for Stem Cell Biology. Lab on a Chip. 2010;10:2019–2031. doi: 10.1039/c004689b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polacheck WJ, Li R, Uzel SGM, Kamm RD. Microfluidic Platforms for Mechanobiology. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:2252–2267. doi: 10.1039/c3lc41393d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferry MS, Razinkov IA, Hasty J. Microfluidics for Synthetic Biology: From Design to Execution. In: Voigt C, editor. Methods in Enzymology, Vol 497: Synthetic Biology, Methods for Part/Device Characterization and Chassis Engineering, Pt A. 2011. pp. 295–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslauer DN, Lee PJ, Lee LP. Microfluidics-Based Systems Biology. Molecular Biosystems. 2006;2:97–112. doi: 10.1039/b515632g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alapan Y, Icoz K, Gurkan UA. Micro- and Nanodevices Integrated with Biomolecular Probes. Biotechnology Advances. 2015;33:1727–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park TH, Shuler ML. Integration of Cell Culture and Microfabrication Technology. Biotechnology Progress. 2003;19:243–253. doi: 10.1021/bp020143k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park H, Cannizzaro C, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Langer R, Vacanti CA, Farokhzad OC. Nanofabrication and Microfabrication of Functional Materials for Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering. 2007;13:1867–1877. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castellana ET, Cremer PS. Solid Supported Lipid Bilayers: From Biophysical Studies to Sensor Design. Surface Science Reports. 2006;61:429–444. doi: 10.1016/j.surfrep.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arlett JL, Myers EB, Roukes ML. Comparative Advantages of Mechanical Biosensors. Nature Nanotechnology. 2011;6:203–215. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JM, Eddington DT, Bhatia SN, Mahadevan L. Sickle Cell Vasoocclusion and Rescue in a Microfluidic Device. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:20496–20500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707122105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nourmohammadzadeh M, Lo JF, Bochenek M, Mendoza-Elias JE, Wang Q, Li Z, Zeng LY, Qi MG, Eddington DT, Oberholzer J, Wang Y. Microfluidic Array with Integrated Oxygenation Control for Real-Time Live-Cell Imaging: Effect of Hypoxia on Physiology of Microencapsulated Pancreatic Islets. Analytical Chemistry. 2013;85:11240–11249. doi: 10.1021/ac401297v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unal M, Alapan Y, Jia H, Varga AG, Angelino K, Aslan M, Sayin I, Han C, Jiang Y, Zhang Z, Gurkan UA. Micro and Nano-Scale Technologies for Cell Mechanics. Nanobiomedicine. 2014;1:5. doi: 10.5772/59379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Y, Cachia MA, Ge J, Xu ZS, Wang C, Sun Y. Mechanical Differences of Sickle Cell Trait (Sct) and Normal Red Blood Cells. Lab on a Chip. 2015;15:3138–3146. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00543d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitesides GM. The Origins and the Future of Microfluidics. Nature. 2006;442:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nature05058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J, Ellis AV, Voelcker NH. Recent Developments in Pdms Surface Modification for Microfluidic Devices. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:2–16. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loiseau E, Massiera G, Mendez S, Martinez PA, Abkarian M. Microfluidic Study of Enhanced Deposition of Sickle Cells at Acute Corners. Biophysical Journal. 2015;108:2623–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bunn HF. Mechanisms of Disease - Pathogenesis and Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:762–769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-Cell Disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Udani M, Zen Q, Cottman M, Leonard N, Jefferson S, Daymont C, Truskey G, Telen MJ. Basal Cell Adhesion Molecule Lutheran Protein - the Receptor Critical for Sickle Cell Adhesion to Laminin. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:2550–2558. doi: 10.1172/JCI1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stuart MJ, Nagel RL. Sickle-Cell Disease. Lancet. 2004;364:1343–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Udani M, Zen Q, Cottman M, Leonard N, Jefferson S, Daymont C, Truskey G, Telen MJ. Basal Cell Adhesion Molecule/Lutheran Protein. The Receptor Critical for Sickle Cell Adhesion to Laminin. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2550–2558. doi: 10.1172/JCI1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zen Q, Cottman M, Truskey G, Fraser R, Telen MJ. Critical Factors in Basal Cell Adhesion Molecule/Lutheran-Mediated Adhesion to Laminin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:728–734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillery CA, Du MC, Wang WC, Scott JP. Hydroxyurea Therapy Decreases the in Vitro Adhesion of Sickle Erythrocytes to Thrombospondin and Laminin. Br J Haematol. 2000;109:322–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alapan Y, Little JA, Gurkan UA. Heterogeneous Red Blood Cell Adhesion and Deformability in Sickle Cell Disease. Scientific Reports. 2014;4 doi: 10.1038/srep07173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alapan Y, Matsuyama Y, Little JA, Gurkan UA. Dynamic Deformability of Sickle Red Blood Cells in Microphysiological Flow. TECHNOLOGY. 2016;0:1–9. doi: 10.1142/S2339547816400045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alapan Y, Kim C, Adhikari A, Gray KE, Gurkan-Cavusoglu E, Little JA, Gurkan UA. Sickle Cell Disease Biochip: A Functional Red Blood Cell Adhesion Assay for Monitoring Sickle Cell Disease. Transl Res. 2016;173:74–91. e78. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shriver-Lake LC, Donner B, Edelstein R, Breslin K, Bhatia SK, Ligler FS. Antibody Immobilization Using Heterobifunctional Crosslinkers. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 1997;12:1101–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhoades RA, Bell DR. Medical Phisiology: Principles for Clinical Medicine. Wolters Kluwer Health. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds KJ, Moyle JTB, Gale LB, Sykes MK, Hahn CEW. Invitro Performance-Test System for Pulse Oximeters. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 1992;30:629–635. doi: 10.1007/BF02446795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu J, Mosher D. Fibronectin and Other Adhesive Glycoproteins. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humes HD, Kelley WN. Kelley's Textbook of Internal Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siveen KS, Kuttan G. Role of Macrophages in Tumour Progression. Immunology Letters. 2009;123:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiche J, Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouyssegur J. Tumour Hypoxia Induces a Metabolic Shift Causing Acidosis: A Common Feature in Cancer. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2010;14:771–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruan K, Song G, Ouyang G. Role of Hypoxia in the Hallmarks of Human Cancer. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2009;107:1053–1062. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gutsaeva DR, Montero-Huerta P, Parkerson JB, Yerigenahally SD, Ikuta T, Head CA. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Synergistic Adhesion of Sickle Red Blood Cells by Hypoxia and Low Nitric Oxide Bioavailability. Blood. 2014;123:1917–1926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-510180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ballas SK. The Cost of Health Care for Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. American Journal of Hematology. 2009;84:320–322. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGann PT, Ware RE. Hydroxyurea Therapy for Sickle Cell Anemia. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2015;14:1749–1758. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2015.1088827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sobota A, Sabharwal V, Fonebi G, Steinberg M. How We Prevent and Manage Infection in Sickle Cell Disease. British Journal of Haematology. 2015;170:757–767. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pauling L, Itano HA, Singer SJ, Wells IC. Sickle Cell Anemia, a Molecular Disease. Science. 1949;110:543–548. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2865.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frenette PS, Atweh GF. Sickle Cell Disease: Old Discoveries, New Concepts, and Future Promise. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:850–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI30920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoots WK, Shurin SB. Future Directions of Sickle Cell Disease Research: The Nih Perspective. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2012;59:353–357. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alapan Y, Fraiwan A, Kucukal E, Hasan MN, Ung R, Kim M, Odame I, Little JA, Gurkan UA. Emerging Point-of-Care Technologies for Sickle Cell Disease Screening and Monitoring. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2016;13:1073–1093. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2016.1254038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Little JA, Alapan Y, Gray KE, Gurkan UA. Scd-Biochip: A Functional Assay for Red Cell Adhesion in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 2014;124 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jison ML, Munson PJ, Barb JJ, Suffredini AF, Talwar S, Logun C, Raghavachari N, Beigel JH, Shelhamer JH, Danner RL, Gladwin MT. Blood Mononuclear Cell Gene Expression Profiles Characterize the Oxidant, Hemolytic, and Inflammatory Stress of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 2004;104:270–280. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noguchi CT, Torchia DA, Schechter AN. Determination of Deoxyhemoglobin-S Polymer in Sickle Erythrocytes Upon Deoxygenation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America-Biological Sciences. 1980;77:5487–5491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Sickle Cell Hemoglobin Polymerization. Advances in protein chemistry. 1990;40:63–279. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hebbel RP, Yamada O, Moldow CF, Jacob HS, White JG, Eaton JW. Abnormal Adherence of Sickle Erythrocytes to Cultured Vascular Endothelium: Possible Mechanism for Microvascular Occlusion in Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1980;65:154–160. doi: 10.1172/JCI109646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aldrich TK, Dhuper SK, Patwa NS, Makolo E, Suzuka SM, Najeebi SA, Santhanakrishnan S, Nagel RL, Fabry ME. Pulmonary Entrapment of Sickle Cells: The Role of Regional Alveolar Hypoxia. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;80:531–539. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.2.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Setty BNY, Chen DC, O'Neal P, Littrell JB, Grossman MH, Stuart MJ. Eicosanoids in Sickle Cell Disease: Potential Relevance of 12(S)-Hydroxy-5,8,10,14-Eicosatetraenoic Acid to the Pathophysiology of Vaso-Occlusion. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1998;131:344–353. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(98)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brownell A, Lowson S, Brozovic M. Serum Ferritin Concentration in Sickle-Cell Crisis. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1986;39:253–255. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Darbari DS, Onyekwere O, Nouraie M, Minniti CP, Luchtman-Jones L, Rana S, Sable C, Ensing G, Dham N, Campbell A, Arteta M, Gladwin MT, Castro O, Taylor JG, Kato GJ, Gordeuk V. Markers of Severe Vaso-Occlusive Painful Episode Frequency in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Anemia. Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;160:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shander A, Cappellini MD, Goodnough LT. Iron Overload and Toxicity: The Hidden Risk of Multiple Blood Transfusions. Vox Sanguinis. 2009;97:185–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Deconstructing Sickle Cell Disease: Reappraisal of the Role of Hemolysis in the Development of Clinical Subphenotypes. Blood Rev. 2007;21:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bessman JD. Reticulocytes. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. Butterworths; Boston: 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Belcher JD, Chen C, Nguyen J, Milbauer L, Abdulla F, Alayash AI, Smith A, Nath KA, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM. Heme Triggers Tlr4 Signaling Leading to Endothelial Cell Activation and Vaso-Occlusion in Murine Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 2014;123:377–390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen G, Zhang D, Fuchs TA, Manwani D, Wagner DD, Frenette PS. Heme-Induced Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Contribute to the Pathogenesis of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 2014;123:3818–3827. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-529982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gladwin MT, Schechter AN, Ognibene FP, Coles WA, Reiter CD, Schenke WH, Csako G, Waclawiw MA, Panza JA, Cannon RO., 3rd Divergent Nitric Oxide Bioavailability in Men and Women with Sickle Cell Disease. Circulation. 2003;107:271–278. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044943.12533.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jison ML, Gladwin MT. Hemolytic Anemia-Associated Pulmonary Hypertension of Sickle Cell Disease and the Nitric Oxide/Arginine Pathway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:3–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2304002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kato GJ, McGowan V, Machado RF, Little JA, Taylor Jt, Morris CR, Nichols JS, Wang X, Poljakovic M, Morris SM, Jr, Gladwin MT. Lactate Dehydrogenase as a Biomarker of Hemolysis-Associated Nitric Oxide Resistance, Priapism, Leg Ulceration, Pulmonary Hypertension, and Death in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 2006;107:2279–2285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reiter CD, Wang X, Tanus-Santos JE, Hogg N, Cannon RO, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Cell-Free Hemoglobin Limits Nitric Oxide Bioavailability in Sickle-Cell Disease. Nat Med. 2002;8:1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rother RP, Bell L, Hillmen P, Gladwin MT. The Clinical Sequelae of Intravascular Hemolysis and Extracellular Plasma Hemoglobin: A Novel Mechanism of Human Disease. Jama. 2005;293:1653–1662. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen J, Hobbs WE, Le J, Lenting PJ, de Groot PG, Lopez JA. The Rate of Hemolysis in Sickle Cell Disease Correlates with the Quantity of Active Von Willebrand Factor in the Plasma. Blood. 2011;117:3680–3683. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nolan VG, Wyszynski DF, Farrer LA, Steinberg MH. Hemolysis-Associated Priapism in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 2005;106:3264–3267. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Belcher JD, Mahaseth H, Welch TE, Vilback AE, Sonbol KM, Kalambur VS, Bowlin PR, Bischof JC, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM. Critical Role of Endothelial Cell Activation in Hypoxia-Induced Vasoocclusion in Transgenic Sickle Mice. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;288:H2715–H2725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00986.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Belcher JD, Mahaseth H, Welch TE, Otterbein LE, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM. Heme Oxygenase-1 Is a Modulator of Inflammation and Vaso-Occlusion in Transgenic Sickle Mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116:808–816. doi: 10.1172/JCI26857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fu S, Tar MT, Melman A, Davies KP. Opiorphin Is a Master Regulator of the Hypoxic Response in Corporal Smooth Muscle Cells. Faseb Journal. 2014;28:3633–3644. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-248708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kovac JR, Mak SK, Garcia MM, Lue TF. A Pathophysiology-Based Approach to the Management of Early Priapism. Asian Journal of Andrology. 2013;15:20–26. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ning C, Wen J, Zhang Y, Dai Y, Wang W, Zhang W, Qi L, Grenz A, Eltzschig HK, Blackburn MR, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Excess Adenosine A2b Receptor Signaling Contributes to Priapism through Hif-1 Alpha Mediated Reduction of Pde5 Gene Expression. Faseb Journal. 2014;28:2725–2735. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-247833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fu S, Davies KP. Opiorphin-Dependent Upregulation of Cd73 (a Key Enzyme in the Adenosine Signaling Pathway) in Corporal Smooth Muscle Cells Exposed to Hypoxic Conditions and in Corporal Tissue in Pre-Priapic Sickle Cell Mice. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2015;27:140–145. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Narang I, Kadmon G, Lai D, Dhanju S, Kirby-Allen M, Odame I, Amin R, Lu Z, Al-Saleh S. Higher Nocturnal and Awake Oxygen Saturations in Children with Sickle Cell Disease Receiving Hydroxyurea Therapy. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015;12:1044–1049. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-473OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Halphen I, Elie C, Brousse V, Le Bourgeois M, Allali S, Bonnet D, de Montalembert M. Severe Nocturnal and Postexercise Hypoxia in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. Plos One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gileles-Hillel A, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Hemoglobinopathies and Sleep - the Road Less Traveled. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2015;24:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Elliott L, Ashley-Koch AE, De Castro L, Jonassaint J, Price J, Ataga KI, Levesque MC, Weinberg JB, Eckman JR, Orringer EP, Vance JM, Telen MJ. Genetic Polymorphisms Associated with Priapism in Sickle Cell Disease. British Journal of Haematology. 2007;137:262–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Madu AJ, Ubesie A, Ocheni S, Chinawa J, Madu KA, Ibegbulam OG, Nonyelu C, Eze A. Priapism in Homozygous Sickle Cell Patients: Important Clinical and Laboratory Associations. Medical Principles and Practice. 2014;23:259–263. doi: 10.1159/000360608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Finnegan EM, Barabino GA, Liu XD, Chang HY, Jonczyk A, Kaul DK. Small-Molecule Cyclic Alpha V Beta 3 Antagonists Inhibit Sickle Red Cell Adhesion to Vascular Endothelium and Vasoocclusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1038–1045. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01054.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matsui NM, Varki A, Embury SH. Heparin Inhibits the Flow Adhesion of Sickle Red Blood Cells to P-Selectin. Blood. 2002;100:3790–3796. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alshaiban A, Muralidharan-Chari V, Nepo A, Mousa SA. Modulation of Sickle Red Blood Cell Adhesion and Its Associated Changes in Biomarkers by Sulfated Nonanticoagulant Heparin Derivative. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1076029614565880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Matsui NM, Borsig L, Rosen SD, Yaghmai M, Varki A, Embury SH. P-Selectin Mediates the Adhesion of Sickle Erythrocytes to the Endothelium. Blood. 2001;98:1955–1962. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kutlar A, Ataga KI, McMahon L, Howard J, Galacteros F, Hagar W, Vichinsky E, Cheung AT, Matsui N, Embury SH. A Potent Oral P-Selectin Blocking Agent Improves Microcirculatory Blood Flow and a Marker of Endothelial Cell Injury in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:536–539. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kutlar A, Embury SH. Cellular Adhesion and the Endothelium: P-Selectin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28:323–339. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ataga KI, Kutlar A, Kanter J, Liles D, Cancado R, Friedrisch J, Guthrie TH, Knight-Madden J, Alvarez OA, Gordeuk VR, Gualandro S, Colella MP, Smith WR, Rollins SA, Stocker JW, Rother RP. Crizanlizumab for the Prevention of Pain Crises in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:429–439. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chikezie PC. Sodium Metabisulfite-Induced Polymerization of Sickle Cell Hemoglobin Incubated in the Extracts of Three Medicinal Plants (Anacardium Occidentale, Psidium Guajava, and Terminalia Catappa) Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2011;7:126–132. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.80670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim KS, Rajagopal V, Gonsalves C, Johnson C, Kalra VK. A Novel Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor in Cobalt Chloride- and Hypoxia-Mediated Expression of Il-8 Chemokine in Human Endothelial Cells. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177:7211–7224. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zarkowsky HS, Hochmuth RM. Sickling Times of Individual Erythrocytes at Zero Po2. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1975;56:1023–1034. doi: 10.1172/JCI108149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Knowlton SM, Sencan I, Aytar Y, Khoory J, Heeney MM, Ghiran IC, Tasoglu S. Sickle Cell Detection Using a Smartphone. Scientific Reports. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep15022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pauline N, Cabral BNP, Anatole PC, Jocelyne AMV, Bruno M, Jeanne NY. The in Vitro Antisickling and Antioxidant Effects of Aqueous Extracts Zanthoxyllum Heitzii on Sickle Cell Disorder. Bmc Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Qamra S, Roy J, Srivastava P. Impact of Sickle Cell Trait on Physical Growth in Tribal Children of Mandla District in Madhya Pradesh, India. Annals of Human Biology. 2011;38:685–690. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2011.608378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Moosavi-Movahedi AA, Mousavy SJ, Divsalar A, Babaahmadi A, Karimian K, Shafiee A, Kamarie M, Poursasan N, Farzami B, Riazi GH, Hakimelahi GH, Tsai FY, Ahmad F, Amani M, Saboury AA. The Effects of Deferiprone and Deferasirox on the Structure and Function of Beta-Thalassemia Hemoglobin. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics. 2009;27:319–329. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2009.10507319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Itano HA, Pauling L. A Rapid Diagnostic Test for Sickle Cell Anemia. Blood. 1949;4:66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sultana C, Shen YM, Johnson C, Kalra VK. Cobalt Chloride-Induced Signaling in Endothelium Leading to the Augmented Adherence of Sickle Red Blood Cells and Transendothelial Migration of Monocyte-Like Hl-60 Cells Is Blocked by Paf-Receptor Antagonist. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1999;179:67–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199904)179:1<67::AID-JCP9>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.