Abstract

Objectives

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is often accompanied by weight loss. We sought to characterize factors associated with weight loss and observed nutritional interventions, as well as define the effect of weight loss on survival.

Methods

Consecutive subjects diagnosed with PDAC (n = 123) were retrospectively evaluated. Univariate analysis was used to compare subjects with and without substantial (>5%) weight loss. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with weight loss, and survival analyses were performed Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox survival models.

Results

Substantial weight loss at diagnosis was present in 71.5% of subjects, and was independently associated with higher baseline body mass index, longer symptom duration, and increased tumor size. Recommendations for nutrition consultation and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy occurred in 27.6% and 36.9% of subjects, respectively. Weight loss (>5%) was not associated with worse survival on multivariate analysis (hazard ratio (HR) 1.32, 95% CI, 0.76–2.30), unless a higher threshold (>10%) was used (HR 1.77, 95% CI, 1.09–2.87).

Conclusions

Despite the high prevalence of weight loss at PDAC diagnosis, there are low observed rates of nutritional interventions. Weight loss based on current criteria for cancer cachexia is not associated with poor survival in PDAC.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, weight loss, cachexia, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) has recently become the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, and is projected to become the second by 2030.1,2 This reflects the combination of a projected increased incidence paralleling the increased prevalence of obesity and poor five-year survival (8%), which has only minimally improved over the last two decades.2 Contributing factors to the poor prognosis include frequent diagnosis at a late cancer stage, aggressive tumor biology, and ineffective treatment options. Existing cancer treatments can be limited due to patient-related factors or side effects of therapy. These limitations are often the consequence of malnutrition, which can lead to impaired quality of life. Malnutrition is primarily characterized by weight loss, and is multifactorial in PDAC due to premorbid malnourishment, cancer-associated cachexia, anatomic factors (e.g., extrinsic compression from the tumor causing gastric outlet obstruction), cancer-induced pancreatic insufficiency (both exocrine (i.e., steatorrhea) and endocrine (i.e., diabetes mellitus)), and/or side effects of treatment (both surgery and chemotherapy).

It is widely accepted that patients with PDAC are at risk for poor nutrition, however factors contributing to malnutrition and the clinical consequences have not been fully studied. Body weight is an objective measure of nutritional status. Although weight is subject to various factors including access to food, dietary intake, physical activity, and genetic influences, it is a widely accepted measure and is currently incorporated in the definition of cancer-associated cachexia, with weight loss >5% supporting a diagnosis of cancer cachexia.3 Previous studies have reported a high prevalence of cachexia in up to 80% of patients with PDAC, and cachexia has been associated with reduced quality of life.4 Studies investigating the effect of weight loss on survival are limited, however, and have had varied results.4 In the present study we sought to more fully characterize weight loss across all stages of PDAC, examining weight trends, nutritional interventions, and the influence of weight loss on survival.

MATERIALDS AND METHODS

This study was approved by The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

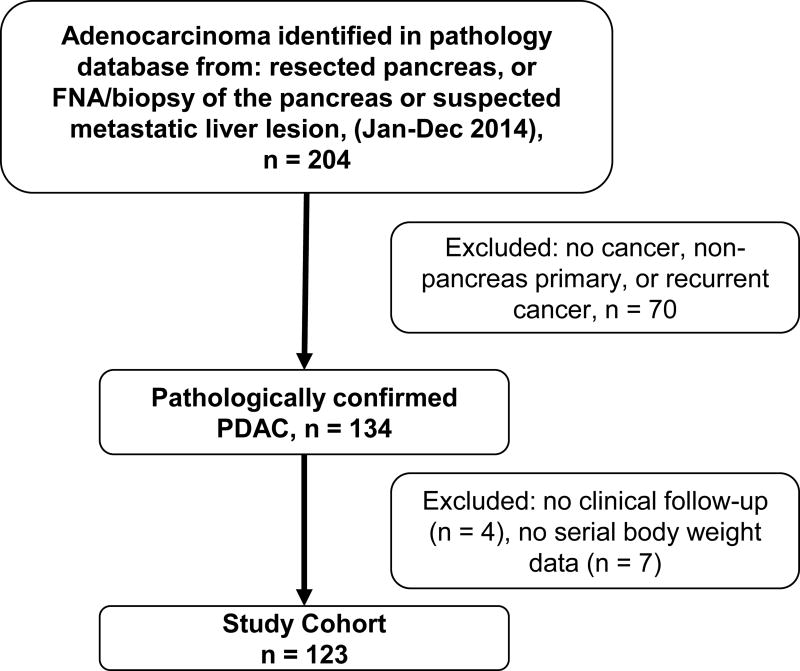

Development of Study Cohort

A retrospective review was performed including subjects with a new pathologic diagnosis of PDAC evaluated at our tertiary care center during the study period (January–December 2014). An electronic pathology database search was performed to identify subjects with histopathologic evidence of PDAC on fine needle aspiration, biopsy, or resected surgical specimen from a pancreatic tumor or liver metastasis secondary to PDAC (Figure 1). Cases were reviewed to ensure the pancreas was the primary site, and subjects were excluded if the tumor was either a non-pancreatic primary (e.g., duodenal or ampullary adenocarcinoma) or if the pathology was inconclusive. Also, for this study only those with ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas were included (i.e., neuroendocrine tumors, adenocarcinoma arising from an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, and other histologic subtypes were excluded). Subjects without clinical follow-up after the initial clinical evaluation and subjects without serial body weights were not included in the analyses.

FIGURE 1.

Study participant flowchart. FNA indicates fine needle aspiration.

Study Definitions

Serial body weights were abstracted from vital signs recorded in the medical record; when unavailable, self-reported weights were used. The “usual adult body weight” (and derived BMI) represents a subject’s typical weight approximately one year prior to diagnosis. For the purposes of this study, “significant” or “substantial” weight loss was defined as weight loss of >5% of the usual body weight, based on the acceptance of this threshold for defining cancer cachexia3. We described surgery as being ‘potentially curative’ when the surgery was pursued with the intent of cancer resection and an R0–R1 resection margin was achieved. The date of PDAC diagnosis was defined as the date of pathologic diagnosis. For time to event analyses, the administrative data of closure was October 27, 2015. The date of last clinical follow-up was defined as either the expiration date or the date of the most recent physician evaluation, whichever was more recent.

Statistical Analyses

Clinical and tumor-related variables were compared between subjects with and without weight loss of at least 5% at PDAC diagnosis to: 1. Identify independent predictors of weight loss in PDAC and 2. Determine the independent effect of weight loss on survival in PDAC. Continuous variables were analyzed with t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and categorical variables were analyzed with chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate.

To identify factors associated with a weight loss of greater than 5% a multivariate logistic regression model was fit. The model included significant variables from univariate comparisons and clinically relevant variables (defined a priori as age, sex, tumor size, cancer stage, and usual adult body mass index [BMI]) in addition to duration of symptoms. This additional variable was selected through a forward stepwise procedure where duration of symptoms, any surgery, potential curative surgery, surgery type, tumor stage, tumor location, N stage, M stage, cancer stage, chemotherapy, and duration of chemotherapy were eligible for inclusion.

Median survival was compared through Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests. Multivariate Cox survival models were fit that included the following a priori covariates: age, tumor size, cancer stage, significant weight loss at cancer diagnosis, sex, and diabetes present at diagnosis. The model was repeated using a series of weight loss thresholds, including >5%, median relative weight loss, >10%, and treating weight loss as a continuous variable based on previous publications. All analyses were completed using Stata version 14 (College Station, Texas). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population Characteristics

A total of 130 subjects with newly diagnosed PDAC were identified during the study period. Serial body weights were not available for 7 subjects who were excluded from subsequent analyses. The mean age at diagnosis was 65.9 years with an equal sex distribution (51.2% were male) (Table 1). The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage distribution at the time of diagnosis reflects the tertiary nature of our clinical center, with a distribution of subjects in stages I, II, III, and IV of 5.8%, 45.0%, 9.2%, and 40.0%, respectively. A total of 63 subjects underwent surgical treatment, including 54 (43.9%) who received a potentially curative surgery (i.e., pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, or total pancreatectomy). The majority (79.3%) of subjects who completed a potentially curative surgery received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, whereas 75.8% of all other subjects underwent chemotherapy.

TABLE 1.

Univariate Comparisons of Clinical Variables Between Patients With Weight Loss Above and Below 5% at Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis

| Overall (n = 123) |

At or Below 5% (n = 35) |

Above 5% (n = 88) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 63 (51.22) | 18 (51.43) | 45 (51.14) | 0.977 |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 65.88 (11.29) | 67.91 (1.78) | 65.07 (1.23) | 0.211 |

| Duration of Symptoms, median (IQR), mo* | 1.58 (0.99–3.32) | 1.12 (0.69–1.78) | 1.86 (1.07–3.60) | <0.001 |

| Surgery Type, n (%)* | 0.035 | |||

| Whipple | 40 (63.49) | 9 (50.00) | 31 (68.89) | |

| Distal Pancreatectomy | 13 (20.63) | 7 (38.89) | 6 (13.33) | |

| Total Pancreatectomy | 1 (1.59) | 1 (5.56) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 9 (14.29) | 1 (5.56) | 8 (17.78) | |

| Potentially curative surgery, n (%) | 54 (43.9) | 17 (48.6) | 37 (42.1) | 0.511 |

| Tumor Size, mean (SD), cm | 3.78 (1.57) | 3.39 (0.20) | 3.95 (0.18) | 0.076 |

| Cancer Stage, n (%) | 0.474 | |||

| Early (stages I–II) | 64 (52.03) | 20 (57.14) | 44 (50) | |

| Late (stages III–IV) | 59 (47.97) | 15 (42.86) | 44 (50) | |

| Chemotherapy Ever, n (%) | 89 (77.39) | 27 (81.82) | 62 (75.61) | 0.472 |

| Usual weight, mean (SD), kg | 87.45 (22.92) | 81.14 (4.05) | 89.96 (2.36) | 0.054 |

| Usual BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 31.18 (7.92) | 28.70 (1.23) | 32.17 (0.85) | 0.028 |

| Weight at diagnosis, mean (SD), kg | 78.89 (20.20) | 80.05 (3.94) | 78.43 (2.02) | 0.688 |

| BMI at diagnosis, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 28.14 (7.00) | 28.30 (1.18) | 28.07 (0.75) | 0.871 |

| Any weight loss at diagnosis, n (%) | 109 (88.62) | 21 (60) | 88 (100) | <0.001 |

| Weight loss at diagnosis mean (SD), kg | 8.56 (7.93) | 1.08 (0.41) | 11.53 (0.79) | <0.001 |

| Any weight loss at last follow-up, n (%) | 85 (72.65) | 26 (76.47) | 59 (71.08) | 0.553 |

| Weight loss at follow-up, mean (SD), kg | 4.65 (10.38) | 5.95 (2.07) | 4.11 (1.06) | 0.388 |

| Total weight Loss, mean (SD), kg | 13.23 (12.38) | 7.06 (2.12) | 15.77 (1.27) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes present at diagnosis, n (%) | 51 (41.46) | 14 (40) | 37 (42.05) | 0.835 |

| Outpatient nutrition counseling, n (%) | 34 (27.64) | 12 (34.29) | 22 (25.00) | 0.299 |

| Pancreatic enzymes recommended, n (%) | 46 (37.40) | 11 (31.43) | 35 (39.77) | 0.388 |

Variables analyzed with nonparametric methods (Wilcoxon rank sum or Fisher’s exact).

Distribution of Weight Loss at PDAC Diagnosis

The mean (standard deviation, SD) body weight and BMI at the time of diagnosis were 78.9 (20.2) kg and 28.1 (7.0) kg/m2. The vast majority of subjects (88.6%) had lost weight at the time of cancer diagnosis compared with their usual adult body weight. The median (IQR) amount of weight loss was 6.8 kg (3.2–11.4), which represented a relative weight loss of 8.4%. A total of 88 (71.5%) of subjects lost >5% of their usual body weight at the time of PDAC diagnosis, and 48 (39.0%) lost >10%.

Clinical Factors Associated With Weight Loss

There were no differences in the clinical profiles of subjects with and without significant weight loss (>5%) at PDAC diagnosis, with the exception that patients who had more weight loss had a longer duration of symptoms (Table 1). There was a higher mean usual BMI among patients who experienced greater weight loss (32.2 mg/kg2 vs. 28.7, P = 0.03). There was a similar trend with an increased mean usual body weight in group that experienced >5% weight loss (90.0 kg vs. 81.1 kg, P = 0.054). Although there were differences in the distribution of cancer stages, this effect was lost when those with stages I and II were compared to III and IV. Lastly, there were no differences in weight loss at diagnosis based on their ability to undergo a potentially curative surgery. The trends observed were similar when groups were redefined using the thresholds for weight loss based on the median absolute weight lost (6.8 kg) and median relative weight loss (8.4%) (data not shown).

A multivariate logistic regression model for significant weight loss demonstrated that increased tumor size, higher usual BMI, and longer duration of symptoms were independently associated with weight loss of >5% at diagnosis (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With a Weight Loss Greater Than 5%.

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.98 | (0.94–1.02) | 0.263 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 0.69 | (0.28–1.71) | 0.419 |

| Female | Reference | ||

| Tumor Size | 1.56 | (1.07–2.29) | 0.022 |

| Cancer stage | |||

| Early (I–II) | 0.85 | (0.34–2.16) | 0.740 |

| Late (III–IV) | Reference | ||

| Usual Adult BMI | 1.09 | (1.01–1.17) | 0.019 |

| Duration of Symptoms | 1.65 | (1.17–2.33) | 0.004 |

It was determined a priori that age, sex, tumor size, cancer stage, and usual adult BMI would be included.

Nutritional Assessments/Interventions

Due to the high prevalence of weight loss in the study cohort, we examined the patterns of nutritional assessments and interventions following PDAC diagnosis. Overall, 34 (27.6%) subjects underwent formal outpatient nutrition counseling involving referral to a dietician; interestingly, the frequency of dietician consultation was similar among patients with and without weight loss (25.0% vs. 34.3%, P = 0.30). Enteral or parenteral nutritional preoperative supplementation was rarely utilized (5 and 5 subjects, respectively). Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) was recommended at similar rates in those with and without significant weight loss (39.8% vs. 31.4%, P = 0.39). Conversely, PERT was used more frequently by those who underwent any surgery compared to those without surgery (53.0% vs. 20.3%, P < 0.01). The median dose of pancreatic enzymes for the 46 subjects who used them was 24,000 units of lipase with meals (IQR, 20,000–48,000). Adherence to recommendations for PERT was not complete in six subjects that declined treatment due to either noncompliance or cost.

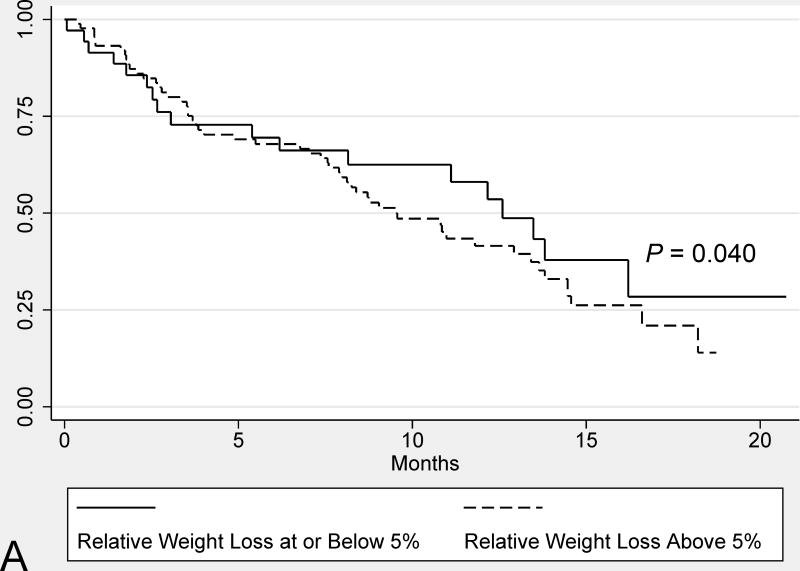

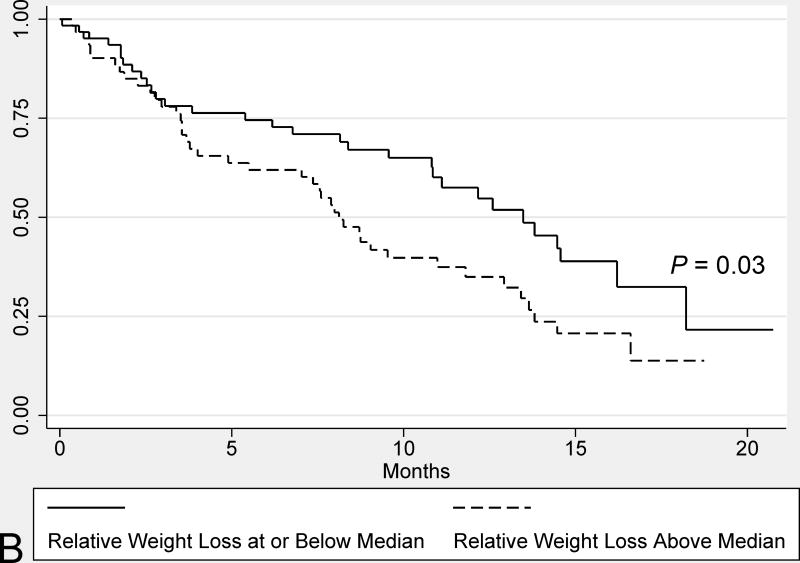

Survival Analysis

Subjects with significant weight loss (>5%) at diagnosis had a similar median survival compared to those without significant weight loss (9.5 months vs. 12.6 months, respectively, P = 0.40) (Figure 2). In contrast, weight loss above the median (8.4%) was associated with worse survival on univariate analysis (8.1 vs. 13.5 months, P = 0.03). Other variables associated with a shorter median survival on univariate analysis included male sex, lack of undergoing a potentially curative surgery, and advanced cancer stage (i.e. AJCC stages III/IV vs. I/II).

FIGURE 2.

Univariate comparisons of the median survival from PDAC diagnosis in all study subjects based on: weight loss above and below 5% weight loss at diagnosis (A) and weight loss above and below the median relative weight loss (8.4%) (B). Survival comparisons were performed for the Kaplan-Meier plots using log-rank tests.

In the primary multivariate survival analysis weight loss (>5%) at cancer diagnosis was not associated with worse survival (Table 3, Model 1); however, when the threshold was raised to >10%, weight loss was independently associated with worse survival (Table 3, Model 2). Conversely, weight loss greater than the median (8.4%) was not associated with survival (see Supplemental Table 1, Model 1). Alternatively, when the model was repeated considering relative weight loss as a continuous variable, weight loss was independently associated with worse survival, but the effect size was relatively small in comparison to other variables (see Supplemental Table 1, Model 2).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Cox Model for Survival

| Model 1 (>5% Weight Loss) |

Model 2 (>10% Weight Loss) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age | 1.03 | (1.01–1.05) | 0.017 | 1.03 | (1.01–1.06) | 0.010 |

| Tumor Size | 1.17 | (1.01–1.37) | 0.042 | 1.16 | (0.99–1.35) | 0.066 |

| Cancer stage | ||||||

| Early (I–II) | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Late (III–IV) | 2.39 | (1.46–3.92) | 0.001 | 2.22 | (1.35–3.66) | 0.002 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Male | 1.48 | (0.91–2.41) | 0.111 | 1.39 | (0.86–2.25) | 0.177 |

| Diabetes at Diagnosis | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.78 | (0.48–1.26) | 0.305 | 0.78 | (0.48–1.25) | 0.294 |

| Weight Loss at Diagnosis | ||||||

| At or Below 5% | Reference | – | – | – | ||

| Above 5% | 1.32 | (0.76–2.30) | 0.323 | – | – | – |

| At or Below 10% | – | – | – | Reference | ||

| Above 10% | – | – | – | 1.77 | (1.09–2.87) | 0.022 |

Factors included were determined a priori.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort study of consecutive subjects diagnosed with PDAC, there was a high prevalence of weight loss at PDAC diagnosis, including almost three-fourths of subjects who lost >5% of their usual body weight. Clinical factors associated with increased weight loss included higher usual adult BMI, a longer duration of symptoms, and increased tumor size. Despite the risk for malnutrition in the cohort, a relatively small number of patients received nutrition consultation or PERT, although the use of PERT was more common in those who underwent surgery. In the present study weight loss >5% at PDAC diagnosis (the most common threshold in defining cancer-associated cachexia) was not associated with worse survival; however a negative impact was observed in those with a greater degree (>10%) of weight loss.

The vast majority (88.6%) of subjects with PDAC lost weight at the time of cancer diagnosis, with almost three-fourths losing >5% of their usual body weight. Previous studies have reported similarly high estimates of weight loss in PDAC ranging from 70–75%.5–7 Despite these high rates of weight loss, there are relatively few studies regarding dietary and nutritional interventions in this population. Accordingly, the observed low rates of nutritional interventions in this cohort are likely multifactorial. First, there are currently no consensus guidelines for nutritional management in PDAC. This is a consequence of the lack of studies that have carefully characterized dietary patterns and success of interventions in PDAC. Similarly, the diagnosis and management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) in PDAC is an area of needed research. There are multiple challenges with the current diagnostic approach of EPI, including the lack of an accurate, non-invasive test to diagnose EPI in general.8 Nevertheless, estimates of the prevalence of EPI based on fecal elastase-1 levels in PDAC is approximately 60–80%.9 Despite the high prevalence of EPI in this disease group, there have been no studies to demonstrate the efficacy of PERT in PDAC, with the exception of patients who have previously undergone surgical resection. In those who undergo pancreatic surgery, the post-operative risk of EPI varies depending on the surgery type (EPI risk is higher in pancreaticoduodenectomy than distal pancreatectomy) and health of the remnant gland. In one study, the prevalence of EPI in PDAC prior to surgical resection was approximately 42–45% compared to 12–80% after distal or central pancreatectomy and 56–98% after pancreaticoduodenectomy.10 In the current cohort, the frequency of PERT usage was much higher in the group who underwent surgical intervention (56.1% vs. 21.9%, P < 0.01), which likely reflects an increased awareness of EPI in this disease subgroup. Other groups have also shown that even though patients may be placed on PERT postoperatively, they are often provided with a suboptimal dosage.11 In sum, further study is needed to effectively diagnose and treat EPI in PDAC.

Prior studies have demonstrated variable effects of weight loss on shortened survival in PDAC, which may be explained by differences in the degree of weight loss considered and the cancer stage distribution of study subjects. Previous studies have examined a variety of measures of cachexia, including weight loss, caloric intake, and/or radiographic measures of soft tissue (muscle and/or fat). Although two groups showed worse survival in those with >10% weight loss,6,12 this was not universally observed.13 Other groups did not dichotomize patients as cachectic and non-cachectic, but rather evaluated the effect of weight loss as a continuous variable.7 As our results in Table 3 (Model 2) illustrate this method of comparison is associated with increased statistical power, but only demonstrates a small effect size. In the end, the heterogeneity in study design and reporting does not allow derivation an accurate summary estimate of the effect of weight loss on survival, illustrating the need for standardized definitions in future studies PDAC-associated weight loss and cachexia.

The most widely used definition for clinically significant weight loss (>5%) is one component of an international consensus definition of cancer cachexia.3 It should be noted, though, that this definition is used across all cancer types clinically meaningful weight loss may differ for various tumor types. A potentially more direct means of assessing cachexia, which avoids limitations with self-reported body weights, involves measuring changes in the skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volume on cross-sectional imaging. However, in the absence of a baseline measure, evaluating for the presence of cachexia at cancer diagnosis is not currently possible. Others have begun categorizing patients who have lost more than 2% of their pre-illness body weight as cachectic if they meet a pre-determined definition of low muscle volume. The muscle volume threshold commonly used has been extrapolated from its ability to predict mortality in obese cancer patients, so the generalizability across all cancer types remains unclear.14 A less commonly used definition of cachexia involves the combination of 2% body weight loss and a BMI of < 20 kg/m2. Considering these challenges, there are ongoing efforts to identify a diagnostic biomarker for cancer cachexia, such as a circulating cytokine, in an effort to develop a useful clinical and translational method for monitoring this condition.

An important aspect to consider in regards to weight loss in the setting of PDAC is the increasingly recognized role of obesity in the pathogenesis of PDAC.15 This may partially explain the observation of larger tumor size in those with greater weight loss (and a greater usual body weight). There is growing evidence to suggest increased systemic and tumor-associated levels of inflammation in the context of obesity may accelerate tumor growth.15,16 Specifically, both central adiposity and an increased BMI, which is the most commonly used measure of obesity, are independently associated with PDAC-associated mortality.17 One recent study also suggested that obesity is associated with worse survival following pancreaticoduodenectomy for PDAC.15 One concern with utilizing BMI measurements as the sole measure of obesity is that it does not distinguish between visceral and subcutaneous fat. Since visceral fat is more metabolically active then subcutaneous fat, it is believed that visceral fat is the predominant contributor for the risk of developing PDAC.18,19 Therefore, further studies are needed to accurately describe and understand the mechanisms and independent contributions of visceral and subcutaneous fat in the risk of developing PDAC and survival after diagnosis as well as further understanding the implications of differential patterns of change in these fat compartments across the course of this cancer.

One challenge with retrospectively studying weight loss is the potential for inaccurate self-reported body weights; which is unavoidable to a degree since many patients are referred for evaluation following diagnosis of PDAC. When available, premorbid body weights were directly abstracted from recorded vital signs. In contrast, all weights at and following cancer diagnosis were measured on calibrated scales and abstracted from the medical records. This limitation remains one of the greatest challenges in studying PDAC-associated cachexia, and illustrates the need for a more reliable, objective marker of cachexia. The retrospective nature of this study also did not permit assessment of subjects’ dietary intake, and standardized protocols for dietary interventions, and diagnosis and treatment of EPI were not utilized. A dietetics consultation was used as an indicator of nutritional intervention, but does not account for other interventions that were self-initiated. Lastly, the inclusion of subjects from all cancer stages permitted us more comprehensively evaluate trends across various cancer stages, but introduces heterogeneity of patient and disease characteristics.

In the present study incorporating all stages of PDAC there was a high prevalence of weight loss (88.6%), including almost three-fourths of subjects who fulfilled the existing criteria for cancer-associated cachexia. Weight loss was associated with increasing age, duration of symptoms, and tumor size, but did not have an independent detrimental survival effect until a higher threshold (>10%) was used. Despite these findings there were low rates of nutritional interventions, aside from the use of PERT in patients who had undergone pancreatic resection, which is likely multifactorial. Further studies are needed to better characterize patient’s dietary intake patterns, and develop standardized approaches to dietary interventions, including diagnosis and treatment of EPI secondary to PDAC. Controlled trials are needed to develop a multi-facetted approach to inhibit PDAC-associated weight loss and cachexia, and should assess the impact on survival, tolerance of cancer-related therapies, and quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) under award number U01DK108327 (DC, PH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- EPI

exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PERT

pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/disclosures: No conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozola Zalite I, Zykus R, Francisco Gonzalez M, et al. Influence of cachexia and sarcopenia on survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Pancreatology. 2015;15:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson SH, Xu Y, Herzog K, et al. Weight Loss, Diabetes, Fatigue, and Depression Preceding Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas. 2016;45:986–991. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadoniou N, Kosmas C, Gennatas K, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with locally advanced (unresectable) or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:543–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pausch T, Hartwig W, Hinz U, et al. Cachexia but not obesity worsens the postoperative outcome after pancreatoduodenectomy in pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2012;152:S81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart PA, Conwell DL. Diagnosis of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2015;13:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s11938-015-0057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartel MJ, Asbun H, Stauffer J, et al. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in pancreatic cancer: A review of the literature. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips ME. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency following pancreatic resection. Pancreatology. 2015;15:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sikkens EC, Cahen DL, van Eijck C, et al. The daily practice of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy after pancreatic surgery: a northern European survey: enzyme replacement after surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1487–1492. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1927-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachmann J, Heiligensetzer M, Krakowski-Roosen H, et al. Cachexia worsens prognosis in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1193–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0505-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fearon KC, Voss AC, Hustead DS, et al. Definition of cancer cachexia: effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1345–1350. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:629–635. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz-Monserrate Z, Conwell DL, Krishna SG. The Impact of Obesity on Gallstone Disease, Acute Pancreatitis, and Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2016;45:625–637. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philip B, Roland CL, Daniluk J, et al. A high-fat diet activates oncogenic Kras and COX2 to induce development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1449–1458. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genkinger JM, Kitahara CM, Bernstein L, et al. Central adiposity, obesity during early adulthood, and pancreatic cancer mortality in a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2257–2266. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathur A, Hernandez J, Shaheen F, et al. Preoperative computed tomography measurements of pancreatic steatosis and visceral fat: prognostic markers for dissemination and lethality of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:404–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sah RP, Nagpal SJ, Mukhopadhyay D, et al. New insights into pancreatic cancer-induced paraneoplastic diabetes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:423–433. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.