Summary

Successful regeneration requires that progenitors of different lineages form the appropriate missing cell types. However, simply generating lineages is not enough. Cells produced by a particular lineage often have distinct functions depending on their position within the organism. How this occurs in regeneration is largely unexplored. In planarian regeneration, new cells arise from a proliferative cell population (neoblasts). We used the planarian epidermal lineage to study how the location of adult progenitor cells results in their acquisition of distinct functional identities. Single-cell RNA sequencing of epidermal progenitors revealed the emergence of distinct spatial identities as early in the lineage as the epidermal neoblasts, with further pre-patterning occurring in their post-mitotic migratory progeny. Establishment of dorsal-ventral epidermal identities and functions, in response to BMP signaling, required neoblasts. Our work identified positional signals that activate regionalized transcriptional programs in the stem cell population and subsequently promote cell type diversity in the epidermis.

In-Brief/eToC blurb

Wurtzel et al. examine how in planarian regeneration, adult progenitor cell location contributes to acquisition of distinct functional identities. They provide insight for how progenitors in the epidermis read their position in the animal to activating region-specific transcription, which is ultimately propagated to differentiated progeny generate the required cellular functions.

Introduction

A major challenge of adult regeneration and tissue turnover is the production of region-appropriate cell types in the absence of embryonic patterning mechanisms (Sanchez Alvarado and Yamanaka, 2014). Progenitors for regeneration, such as stem cells or dedifferentiated cells, must be regulated to choose which cell types to make, and these cell types must be appropriate for their location (Reddien, 2011). Furthermore, cells of the same lineage and cell type often have specialized functions depending on their location (Lavin et al., 2014), which requires additional control over their differentiation (Baxendale et al., 2004; Gautier et al., 2012). Therefore, mechanisms governing lineage choice and the regional specialization of cell function are of central importance in regeneration. Here, we focus on the questions of how and when region-appropriate specialization occurs within a lineage.

Planarians are free-living flatworms that use adult stem cells to maintain tissues and to regenerate (Reddien and Sanchez Alvarado, 2004). The only proliferating cell population in planarians, neoblasts, contain pluripotent stem cells (Wagner et al., 2011). Many neoblasts are specialized towards particular cell types including cells of the protonephridia (Scimone et al., 2011), intestine (Forsthoefel et al., 2012), pharynx (Adler et al., 2014; Scimone et al., 2014a), nervous system (Cowles et al., 2013; Scimone et al., 2014a), eye (Lapan and Reddien, 2012), and anterior pole (Scimone et al., 2014b). The location of a neoblast (Reddien, 2013) impacts its identity: For example, eye-specialized neoblasts are not found in the posterior of the animal (Lapan and Reddien, 2012) and intestinal neoblasts are often in proximity to the planarian gut (Wagner et al., 2011). Therefore, spatial information likely affects the identity of neoblasts and their progeny (Reddien, 2013).

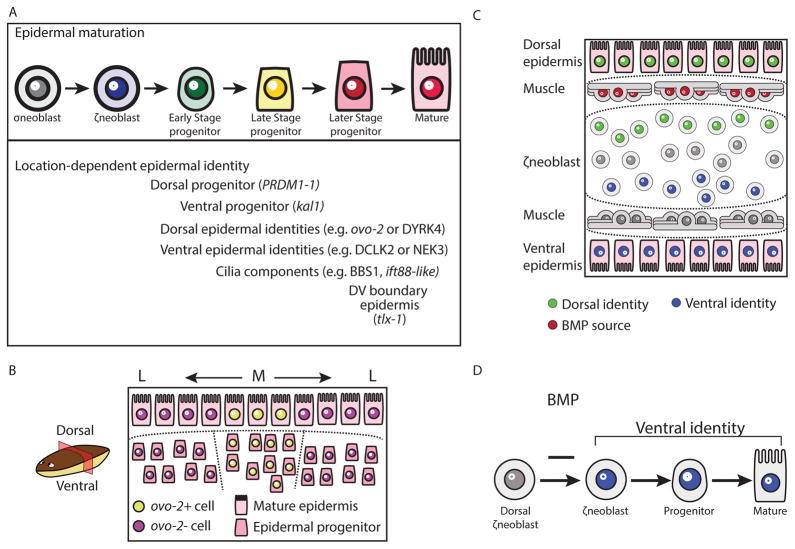

Conversely, it is unknown how the spatial distribution of neoblasts and progenitors within a lineage generates a diversity of cellular identities and functions. The planarian epidermis presents an ideal system for studying this question: First, multiple cellular identities with specialized functions are found in the epidermis in specific body locations (Glazer et al., 2010; Tazaki et al., 2002), and these cells appear to emerge from a single specialized neoblast lineage (ζneoblasts; Fig 1A) (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014). Second, there are well-established assays for evaluating planarian epidermal integrity and function (Tu et al., 2015; van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014; Vij et al., 2012), and the status of the lineage from neoblasts (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014) all the way to mature cells (Tu et al., 2015). Finally, the epidermal lineage has well-characterized differentiation stages (Fig 1A) that are both spatially and temporally distinct (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Tu et al., 2015; van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014).

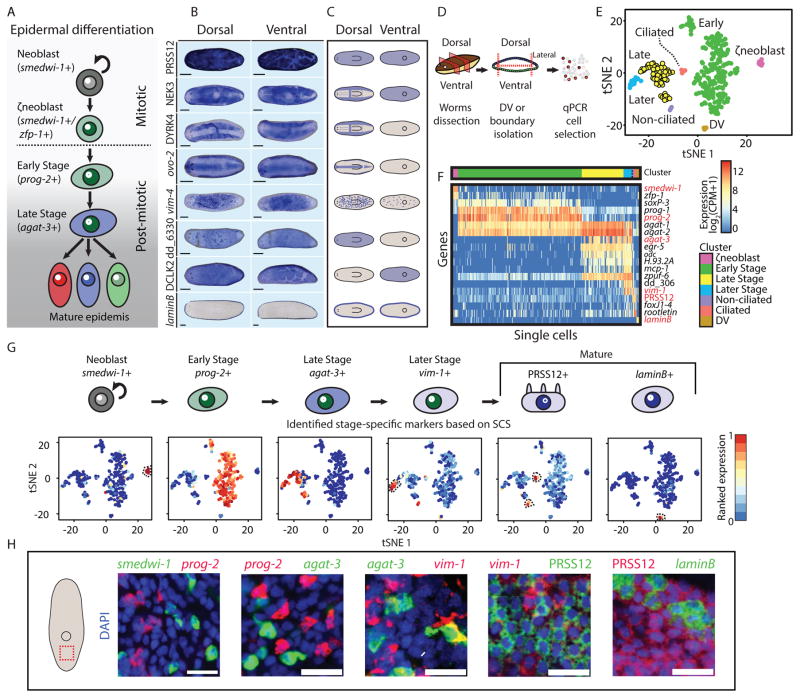

Figure 1. Mature epidermal identities revealed by RNA-seq.

(A) A model for planarian epidermal maturation. Epidermal progenitors have spatiotemporally distinct stages (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Tu et al., 2015). Stage-specific gene expression markers distinguish different maturation stages. Epidermal progenitors generate multiple epidermal cell types characterized by different spatial distribution and gene expression. (B) Different epidermal gene expression patterns were detected by WISH. Shown are eight representative expression patterns (blue) in dorsal (left column) and ventral (right column) views. As animals are semitransparent, following bleaching (Pearson et al., 2009), assessing domains of expression requires examination from multiple viewpoints (scale bar = 100 μm). (C) Cartoon of the expression patterns reported in Fig 1B. Blue color represents region of epidermal expression. (D) Analysis of the epidermal lineage by SCS. Isolation of epidermal progenitors; pre-pharyngeal fragments were dissected to isolate dorsal, ventral, or lateral fragments, separately (STAR Methods). Tissues were disassociated and individual cells were sorted to plates by FACS. agat-1 expression (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008) was measured by qPCR and cells expressing agat-1 were sequenced and used for analysis, in combination with previously published SCS of the epidermal lineage (Wurtzel et al., 2015). (E) t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) representation of epidermal cells (dots) is shown (STAR Methods). Colors represent different clusters, with labels for cluster identities based on gene expression markers for epidermal maturation stages (Tu et al., 2015). (F) Gene expression in single cells (columns) of previously described epidermal genes (rows). Gene expression is represented by color (blue to red, low to high expression; counts per million, CPM; Hierarchal clustering was used to order cells within a cluster). Red labels denote genes that were subsequently used for FISH experiments, because of their power to discriminate between clusters, and their low background expression in FISH (Table S3). (G) Upper panel: Cluster-specific gene expression markers that were used for evaluating the distribution of epidermal lineage progenitors in situ. Markers were selected based on their fold-enrichment and power to discriminate between clusters. Lower panel: tSNE plot of cells (dots) colored by the ranked expression of the gene markers we selected across all sequenced cells (blue to red, low to high gene expression, respectively; dotted black line highlights cell clusters). (H) The selected gene expression markers were assessed by co-expression FISH analysis (scale bar = 20 μm). The markers had a nearly complete lack of co-expression, therefore permitting the analysis of distinct maturation stages.

The epidermal lineage is derived from mitotic ζneoblasts that are distributed throughout the mesenchyme (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014). A ζneoblast exits the cell-cycle and progresses through a series of defined stages during its differentiation (Fig 1A) (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Tu et al., 2015), a process that takes at least seven days (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014). During differentiation, cells migrate from the mesenchyme outwards to the epidermis, and ultimately integrate into the mature epidermis, a single-layered epithelial sheet (Tu et al., 2015). This is in contrast to other established models used for studying the generation of epithelial cell type diversity (Cibois et al., 2015; Dubaissi and Papalopulu, 2011; Quigley et al., 2011), such as the Xenopus embryonic epidermis, in which epithelial progenitors migrate from an inner monolayer to an outer monolayer. In this case, progenitors can rely on physical cell-cell communication to determine cell fates (Cibois et al., 2015; Dubaissi and Papalopulu, 2011; Quigley et al., 2011). In planarians, mesenchymal progenitors are hypothesized to rely on secreted positional cues (Reddien, 2011), creating different challenges for the generation of cell-type diversity. In this process progenitors display a stereotyped sequence of gene expression changes, collectively described as maturation (Fig 1A) (Tu et al., 2015). This apparently homogeneous population of progenitors gives rise to spatially distinct mature epidermal cell types (Glazer et al., 2010).

We devised a strategy to determine at which stage in the epidermal lineage cells express genes associated with distinct spatial identities. We developed a method for isolating dorsal and ventral epidermis, which facilitated the detection of eight spatial mature epidermal identities. We asked whether these identities emerge in the differentiated cells, their immediate progenitors, or even as early as in the spatially and temporally distant ζneoblasts that will produce these cells. The emergence of distinct expression patterns was analyzed by single-cell RNA sequencing (SCS) of 303 cells spanning every step of epidermal maturation, combined with in situ hybridization (ISH) of over 125 epidermal genes. We found that epidermal neoblasts (ζneoblasts) and progenitors from all stages of epidermal maturation express genes according to their location within the animal. Analysis of ζneoblasts and progenitors across the dorsal-ventral (DV) axis revealed divergent transcriptional programs that correlated with the emergence of distinct dorsal or ventral epidermal identities. Inhibition of bmp4, a dorsalizing factor (Molina et al., 2007; Orii and Watanabe, 2007; Reddien et al., 2007) that is constitutively expressed in dorsal muscle cells (Witchley et al., 2013), resulted in the rapid dorsal emergence of ventral ζneoblasts and their progeny. This lineage ventralization, following bmp4 inhibition, did not occur in the absence of ζneoblasts even when their progeny were present. This indicates that ζneoblasts respond to positional signals in their environment and activate region-appropriate transcriptional programs. These findings demonstrate that single-cell RNA sequencing, from distinct body regions, is a powerful method for revealing the spatial identity of progenitors for regeneration and tissue maintenance. Our results demonstrate that distinct regional identities are detectable within the neoblast population, and that signals from differentiated cells can be read by neoblasts to promote spatial cell-type diversity.

Results

Epidermal genes are expressed in at least eight different spatial patterns

Multiple cellular identities, distinguished by distinct gene expression domains, make the planarian epidermis. Our goal was to find how and when, during the formation of new epidermal cells, distinct epidermal identities emerge. Previous work identified three epidermal identities: ciliated epidermis (Glazer, 2010), non-ciliated epidermis, and dorsal-ventral (DV) boundary epidermis (Tazaki, 2002). However, other epidermal identities might exist. Since our work required a broad classification of epidermal identities, we first characterized mature epidermal identities through analysis of epidermal gene expression. We implemented an epidermal-enrichment strategy based on ammonium thiocyanate treatment (Trost et al., 2007), which allowed for the collection of the epidermis (Fig S1A; STAR Methods). Isolated epidermis was used for RNA extractions from six biological replicates from the dorsal or ventral epidermal surfaces, separately (Fig S1A–B; STAR Methods), which was followed by preparation of RNA sequencing libraries (STAR Methods). Comparison of the epidermis-enriched RNAseq libraries with libraries prepared from RNA extracted from whole worms identified 3,315 genes that were overexpressed in the epidermis (Fig 1C–E; fold-change ≥ 2; FDR < 1E-4; STAR Methods), including 393 and 233 genes enriched in either the dorsal or ventral epidermis, respectively (Fig S1D; Table S1).

We characterized the diverse patterns of epidermal gene expression by selecting 125 epidermis-enriched genes (Fig S1D–E; Table S1) and performing whole-mount in situ hybridizations with RNA probes (WISH). WISH analysis revealed that 90% (113/125) of the genes were in fact enriched in the epidermis (Fig 1B, S1F; Table S1), which we then classified to eight distinct expression patterns (Fig 1B–C; Fig S1F–G; Table S1), representing diverse mature epidermal identities (Fig 1C). We subsequently used representatives of these patterns to study when, during epidermal differentiation, spatial gene expression domains emerge.

Reconstructing the epidermal lineage by single-cell sequencing

The expression of epidermal genes can emerge before differentiation is complete (Tu et al., 2015). For example, vim-1 was expressed in epidermal cells that were not yet integrated into the epidermis (Fig S1G), in contrast to PRSS12 and laminB (Fig S1G), which were expressed only in the mature epidermis. However, it is unclear how early in differentiation mature epidermal gene expression can initiate. To determine the stage of epidermal differentiation at which epidermal identities emerge, we characterized the transcriptomes of epidermal progenitors with single cell resolution. We dissected different body regions, including dorsal, ventral, or lateral tissues (Fig 1D; STAR Methods) and, following maceration of the fragments, we isolated cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; STAR Methods). Then, we selected cells for sequencing by quantitative PCR (qPCR) for the expression of an epidermal progenitor marker, agat-1, which we found to be expressed in all post-mitotic epidermal progenitors both by SCS (Wurtzel et al., 2015) and FISH (Fig S2A–B; STAR Methods). In addition, we isolated lateral tissues and selected cells expressing an epidermal boundary marker (laminB; Fig 1B, S1G; (Tazaki et al., 2002)). In total, we collected 205 epidermal progenitors (agat-1+) and 6 epidermal boundary cells (laminB+). We used these cells for SCS (Picelli et al., 2014), and the data that was generated was analyzed in combination with published epidermal lineage SCS data (98 cells; (Wurtzel et al., 2015)). SCS gene expression data was visualized by t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) (van der Maaten and Hinton, 2008), and the data was clustered using the Seurat package (Satija et al., 2015) (Fig 1E; Table S2; STAR Methods). The clustering analysis recapitulated known epidermal lineage cell states (Tu et al., 2015), here defined as: “ζNeoblast”, “Early Stage”, “Late Stage”, “Later Stage”, and 3 mature cell types (Fig 1E–F; S2C–F). Gene expression comparison between clusters identified 1,452 genes enriched in particular clusters (Table S3; FDR < 0.001, fold-change > 4; STAR Methods). We selected highly specific gene markers to each maturation state based on this analysis (AUC range 0.81–1; Fig 1F–G; S2C–D), and used them for FISH (Fig 1H). These data represent comprehensive gene expression profiles of every stage of planarian epidermal differentiation.

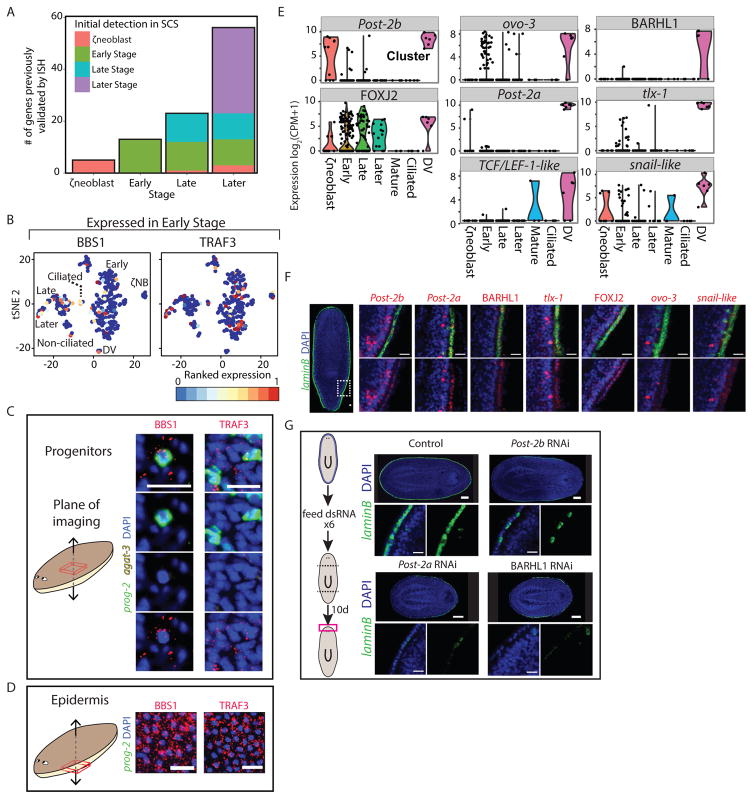

Many mature epidermal genes are expressed in Early Stage progenitors

The SCS data we collected spanned every stage of epidermal maturation, which allowed determination of whether genes expressed in the mature epidermis (Table S1), were also expressed in progenitors and at what stage. We found that 24% of these genes (Fig 2A) were expressed in at least 30% of the Early Stage or Late Stage progenitors (Table S1; STAR Methods). Interestingly, some of these genes encode proteins that are associated with mature epidermal functions, such as ciliogenesis (Fig 2B, S3A). This raised the possibility that progenitor populations display distinct epidermal identities despite having at least four days to complete their maturation (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014). We tested these results by FISH on whole animals (Fig 2B–D; S3A–C) or by FISH on FACS-sorted cells (cell FISH; Fig S3D; STAR Methods). Expression of tested genes encoding cilia components (e.g. BBS1 and ift88-like) was detectable in Early Stage progenitors and mature epidermis (Fig 2B–D, S3A–D), but not in dividing neoblasts (Fig S3E). SCS, however, predicted that 23% of the centriole-associated genes (Azimzadeh et al., 2012) were also expressed in neoblasts (Table S4). This observation is consistent with the recent report by Duncan et al. on the expression of cilia components in neoblasts (Duncan et al., 2015). Furthermore, transcripts for 75% (20/27) of centriole-associated genes (Azimzadeh et al., 2012), which are expressed in ciliated cells (Azimzadeh et al., 2012; Wurtzel et al., 2015) were detectable in Early Stage or Late Stage progenitors (Table S4), despite the fact that cilia were restricted to the mature epidermis (Fig S3F). Therefore, cilia appeared to only be assembled in mature epidermal cells despite transcription of genes encoding cilia components in progenitors. The correlation of co-expression of multiple structural cilia genes in single cells was much higher in Later Stage progenitors compared to Early Stage or Late Stage progenitors (Average Pearson correlation r=0.08, 0.1, 0.43 for Early Stage, Late Stage, and Later Stage, respectively; STAR Methods). However, expression of cilia-encoding genes was unlikely non-specific even in Early Stage progenitors, because expression of genes encoding cilia components was completely undetectable in non-ciliated cell types, such as muscle or gut (STAR Methods; (Wurtzel et al., 2015)). These results suggest that epidermal cells can adopt a distinct functional identity (becoming ciliated or not) early during differentiation, rather than acquiring an identity only after integration into the mature epidermis.

Figure 2. Mature epidermal gene expression is abundant in epidermal progenitors.

(A) Expression of validated epidermal genes in SCS data across epidermal clusters. Shown are genes that were expressed only in the epidermal lineage. Color coding corresponds to the maturation stage in which the gene was initially expressed. (B) tSNE plots of two epidermal genes validated by WISH (BBS1 and TRAF3), that were found to be expressed in Early Stage progenitor cells (expression low to high, blue to red, respectively). (C–D) FISH validation of epidermal gene expression in Early Stage and Late Stage progenitors (C) and in mature epidermis (D), taken in different focal planes in the same animals (see schematic) by confocal microscopy (scale bar = 20 μm). White arrows indicate co-expression. Early Stage (prog-2) and Late Stage (agat-3) progenitor markers are not expressed in the mature epidermis. (E) Violin plots of the eight TFs that were enriched in the DV boundary epidermal cells are shown. Black dots represent expression of a single cell. (F) FISH validation of DV-boundary epidermis TFs, including co-expression with laminB. The expression of the TFs is shown in higher magnification at a DV region corresponding to the white-dashed box in the overview (left) image. See also Fig S3G. Scale bar = 20 μm. (G) Inhibition of three of the DV epidermal boundary TFs led to a reduction in DV epidermal boundary gene expression in regenerating animals 10 days following amputation, as observed by FISH for laminB expression. Top panels: The expression of laminB is greatly reduced in the perturbed animals. Scale bar = 100 μm. Bottom panels: Higher magnification of the DV boundary in the different RNAi conditions. Scale bar = 20 μm.

RNAi identifies transcription factors required for spatially-restricted epidermal identity

We observed that a number of genes with spatially-restricted expression patterns in the epidermis encode predicted transcription factors, raising the possibility that multiple transcription factors (TF) regulate epidermal spatial patterning. For instance, eight TFs were predicted to be expressed in the DV epidermal boundary cells in our SCS data (Fig 2E; STAR Methods). We validated the DV-boundary epidermis expression for seven of eight by FISH (Fig 2F, S3G). We inhibited these genes by RNAi (Fig 2G; STAR Methods) and performed FISH on regenerating heads or tails for a DV epidermal marker (laminB). RNAi of three genes, Post-2a, Post-2b, and BARHL1, resulted in a striking reduction of epidermal DV boundary expression (laminB; Fig 2G), and in addition BARHL1 RNAi also resulted in lesions around the pharyngeal cavity (Fig S3H), a region in which BARHL1 is expressed (Fig S3I). In contrast, these three TFs did not affect other mature epidermal cell types, as tested by FISH, indicating their specific requirement for activation of DV-boundary epidermis gene expression (Fig S3J). These results demonstrate that certain TFs specifically drive gene expression of epidermal subpopulations and that TFs are good subjects for study of the acquisition of spatial identity within the epidermal lineage.

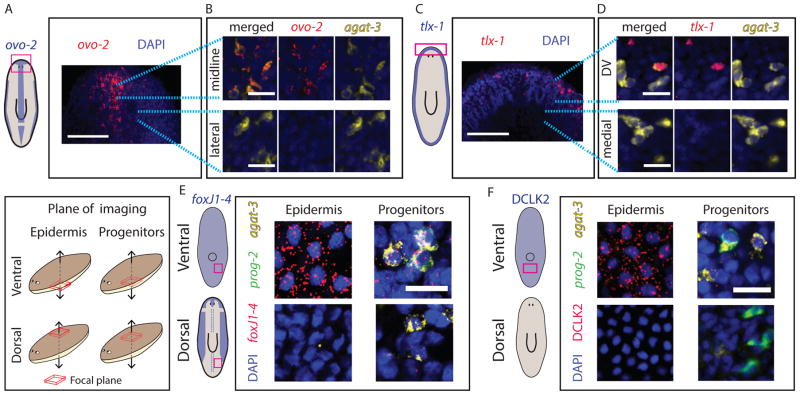

Spatially-restricted epidermal identities emerge in progenitors

Mature epidermal identities have distinct spatial distributions across the different body axes (Fig 1B–C). These distinct patterns of gene expression might (1) emerge in progenitors, or (2) might only be present after cells have been incorporated into the mature epidermis. We selected epidermal TFs, which are expressed in a spatially restricted manner in the mature epidermis (Fig 1B–C, 2F, S3G), and analyzed their expression in epidermal progenitors. In the mature epidermis, ovo-2 (Fig 1B–C, Fig 3A–B, S4A–B) was expressed in the dorsal midline and the lateral edges. Imaging a plane of internal tissues (Fig 3A–B, Fig S4B; STAR Methods) showed spatially restricted expression in immature epidermal progenitors (agat-3+) that was highly reminiscent of the pattern of ovo-2 expression in the mature epidermis (Fig 1B–C, 3A). Inhibition of wnt5, which causes expansion of the planarian midline (Adell et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2010), resulted in expansion of the ovo-2 expression domain (Student’s unpaired t-test p < 0.02; Fig S4C). In a similar fashion to ovo-2, tlx-1, which is specifically expressed in the DV boundary (Fig 2E–F, S3G), was expressed in epidermal progenitors (agat-3+) only next to the DV boundary and not in epidermal progenitors further away (Fig 3C–D). Furthermore, foxJ1-4, which is expressed in ciliated epidermis (Fig S3K), was abundantly expressed in agat-3+ cells near ciliated epidermal regions, such as on the ventral surface (Fig 3E), but not in the vicinity of non-ciliated areas, such as the dorsal midline region (Fig 3E). Finally, we examined the spatially restricted expression of the gene DCLK2, which encodes a doublecortin protein kinase rather than a TF, and which is expressed in the ventral epidermis (Fig 1B–C). DCLK2 was expressed in multiple ventral epidermal progenitors, but not in any dorsal progenitors (Fig 3F). By contrast, the expression of DYRK4 (Fig 1B–C) was not detectable in epidermal progenitors (Fig S4D), despite having a spatially restricted expression pattern in mature cells. These results demonstrate that gene expression in immature epidermal progenitors is pre-patterned in a manner that reflects some of the spatial identities that are found in the mature epidermis. This suggests that migratory epidermal progenitors detect their position in the animal to activate regionallyappropriate transcriptional programs that will reflect the pattern of gene expression in the mature epidermis.

Figure 3. Expression of spatially-restricted mature epidermal identities is pre-patterned in epidermal progenitors.

(A) ovo-2 expression in the head is restricted to the midline (Scale bar = 100 μm; schematic shows spatial expression restriction in blue). (B) In the focal plane of the progenitors, ovo-2 expression is limited to progenitors in the midline (upper panel), and is not found in progenitors immediately lateral to the midline (lower panel). Blue dotted lines indicate higher magnification area. Scale bar = 20 μm. (C) tlx-1 expression in mature epidermis is found in DV epidermal cells (left schematic), however, tlx-1 expression was also detectable in epidermal progenitors in proximity to the DV boundary, but not detected in progenitors in other parts of the animal (scale bar = 20 μm). (E–F) Shown are confocal images at different focal planes of dorsal or ventral regions of the animal. See key (left panel). Scale bar = 20 μm. (E) foxJ1-4, an essential gene for ciliogenesis (Vij et al., 2012) is expressed in ventral epidermis (top-left), and the lateral flanks the dorsal epidermis, but not in the dorsal-medial part (bottom-left; See schematic). The expression of foxJ1-4 is present in epidermal progenitors at the ventral region (top-right), but not in the dorsal region (bottom-right). (F) The expression of DCLK2 is detectable in ventral but not dorsal epidermis (Fig 1B; left schematic). Similarly, ventral epidermal progenitors, but not dorsal progenitors already displayed DCLK2 expression, demonstrating that epidermal progenitors activate region-appropriate transcriptional program according to their DV position.

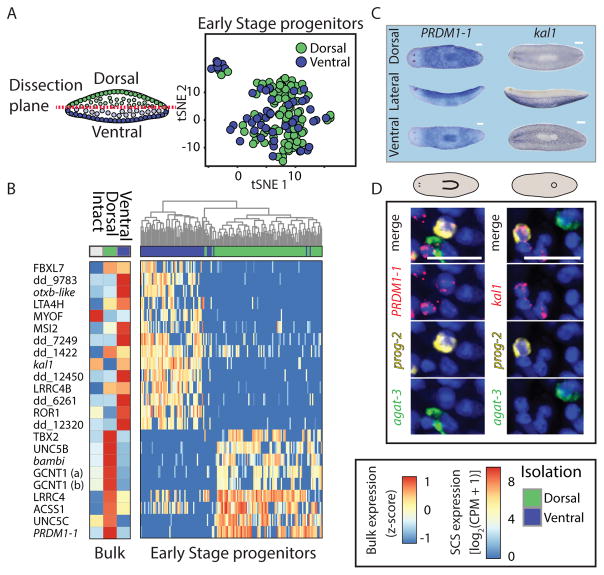

Dorsal and ventral gene expression distinguishes Early Stage post-mitotic progenitors

The results above demonstrated that some genes are expressed in epidermal progenitors based on their location in the animal (Fig 3, S4B). Because the dorsal and ventral epidermis display strikingly different expression patterns (Fig 1B–C), we sought to elucidate how early during maturation dorsal and ventral identities emerge. Approaches for identifying genes that are expressed in a spatially restricted pattern within a lineage are challenging because they require comparing cells from a similar maturation stage, but from different locations. The single cells we sequenced were isolated from physically separated dorsal or ventral regions in the animal (Fig 4A), and through SCS clustering (Fig 1E–F; STAR Methods), they were assigned to a maturation stage (Fig 1E, 4A; Table S2). Therefore, this approach allows for the systematic identification of genes with spatially restricted expression in epidermal progenitors. To find the earliest differences in gene expression across epidermal populations we compared gene expression of Early Stage progenitors from dorsal and ventral regions (Fig 4A). In total, we found 23 genes that were significantly enriched (Fig 4B; Fold-change > 4; FDR < 0.1; Power > 0.4; Table S5) in dorsal or ventral progenitors, a finding that was supported by bulk RNA sequencing from dorsal or ventral animal fragments for 19/23 genes (Fig 4B). Remarkably, the expression of two genes strongly predicted whether a cell is dorsal (PRDM1-1; AUC = 0.85; Fig S5A; Table S5) or ventral (kal1; AUC = 0.9; Fig S5B; Table S5), a finding that is consistent with the whole-mount expression patterns for these genes (Fig 4C). FISH analysis validated that prog-2+/PRDM1-1+ cells were restricted dorsally and that prog-2+/kal1+ were exclusively ventral (Fig 4D). Importantly, whereas PRDM1-1 expression appeared exclusively in dorsal epidermal progenitors, kal1 was expressed in other cell types in ventral tissues, including neural and muscle cells (Fig S5C–D), suggesting it is a broader ventral marker. The expression of PRDM1-1 and kal1 strongly correlated with other DV-biased identities: the majority of cells expressing ovo-2 (log2(CPM) > 5), which is expressed only dorsally (Fig 1B–C, 3A–B), also expressed PRDM1-1 in SCS data (Fig S5E; overlap = 67%; percentile rank of fraction overlap = 0.98; STAR Methods), but none expressed kal1 (Fig S5E). Similarly, the expression of DCLK2 overlapped with the expression of kal1 (Fig S5F; overlap = 35%; percentile rank of overlap = 0.84), a gene that is expressed specifically in the ventral epidermis (Fig 1B–C, 3F), but not with the expression of PRDM1-1 (0%). These results indicate that the DV-bias observed in Early Stage gene expression is correlated with subsequent spatially restricted epidermal identities.

Figure 4. Early Stage progenitors activate divergent transcriptional programs based on their DV location.

(A) Left: Tissues were dissected from dorsal and ventral regions and epidermal progenitors were isolated by FACS and qPCR (Fig 1D; STAR Methods). Early Stage progenitors were identified computationally (STAR Methods), and gene expression of dorsal and ventral Early Stage progenitor samples was compared. Right: tSNE plot of Early Stage progenitors from dorsal and ventral regions (green and blue dots, dorsal and ventral cells, respectively). (B) Right: Differentially expressed genes (rows) in dorsal and ventral Early Stage progenitors (columns) demonstrate differences between cells that differ in their position across the boundary. Dendrogram was generated by hierarchical clustering of the gene expression. Many of the genes that have a biased DV-expression in the progenitors also display biased expression in the mature epidermis-enriched samples (left heat map; shown is the average expression across replicates from the same sample type). (C) WISH analyses of the dorsal-specific gene marker (PRDM1-1) and the ventral-specific gene marker (kal1) demonstrate distinct regionalized expression (scale bar = 100 μm). (D) Expression of PRDM1-1 and kal1 is found in Early Stage progenitors and is restricted to the dorsal or ventral regions, respectively. Shown is co-expression of either PRDM1-1 or kal1 with an Early Stage marker (prog-2; white arrow).

Epidermal neoblasts express dorsal and ventral markers

Epidermal progenitors are the product of mitotic ζneoblasts (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014). The expression of DV-biased genes in epidermal progenitors raised the question of whether DV identities exist as early in the lineage as the ζneoblasts. We tested this possibility by analyzing the expression of DV-biased epidermal progenitor genes in neoblasts. PRDM1-1 and kal1 expression was highly specific to ζneoblasts in SCS data (Fig S6A), and was detectable in 68% of the cells (Fig 5A). In addition, we used cell FISH to quantify the fraction of dividing neoblasts expressing PRDM1-1 or kal1, and found that 6.7% and 9.7% of the neoblasts expressed PRDM1-1 or kal1, respectively (Fig 5B). Similarly, we quantified the proportion of ζneoblasts in the dividing neoblast pool by cell FISH and found that they comprised 31% of dividing neoblasts (Fig S6B). Therefore, we estimated that ~53% of ζneoblasts express either PRDM1-1 or kal1 using cell FISH. Strikingly, the expression of PRDM1-1 and kal1 in SCS was mutually exclusive in ζneoblasts (Fig 5A), a finding we corroborated with cell FISH on dividing neoblasts (Fig S6C; number of cells counted = 1061).

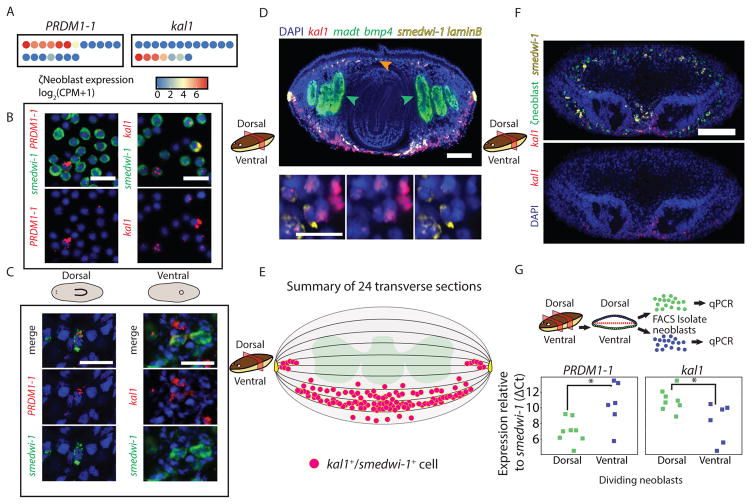

Figure 5. Spatially opposed expression of PRDM1-1 and kal1 in neoblasts.

(A) ζneoblasts express PRDM1-1 or kal1 in mutually exclusive single ζneoblasts (dots; blue to red, low to high gene expression, respectively). (B) The fraction of neoblasts expressing dorsal (PRDM1-1) or ventral (kal1) markers was estimated by co-expression analysis of FACS-isolated dividing neoblasts, and co-staining with a neoblast marker (smedwi-1). (C) FISH showing PRDM1-1 expression in dorsal neoblasts (left), and kal1 is found only in ventral neoblasts (right). kal1 was not expressed in dorsal neoblasts in at least 10 animals; PRDM1-1 was not expressed in ventral neoblasts in at least 10 animals. (D) Shown is a transverse section (see cartoon) labeled for kal1 (red), madt (green; intestinal marker; green arrows), bmp4 (green; orange arrow), smedwi-1 (yellow; neoblast marker), and laminB (yellow; DV-boundary epidermis). Scale bar = 100 μm. kal1+/smedwi-1+ cells were counted (bottom panel, white arrows) and their position in the animal was documented (STAR Methods). Scale bar = 20 μm. See also Fig S6E. (E) Summary of the location of kal1+/smedwi-1+ cells in 24 transverse sections (magenta circles). Sections were divided to 10 regions (bounded by black lines) and the number of kal1+/smedwi-1+ cells was counted in each region (STAR Methods). The medial-lateral position of the cells was not measured and the medial-lateral spread is for clarity, except for cells next to the DV-boundary epidermis (yellow cartoon), which represent the approximate distance of these cells from the boundary. All kal1+/smedwi-1+ cells were ventral to the intestine (green cartoon), except for those next to the DV-boundary epidermis. (F) FISH on animals labeled for ζneoblasts markers (pool of soxP-3 and zfp-1) and kal1 shows that kal1-ζneoblasts extends more internally than kal1 expression (white arrow), suggesting that ventral ζneoblasts express kal1 when they are only near the epidermal surface. Top panel shows all channels; bottom panel shows kal1 expression and DAPI. Scale Bar = 100 μm. See Figure S6F for single channel images. (G) Top panel: Schematic of dividing neoblast isolation by FACS (STAR Methods). Pre-pharyngeal segments were isolated and were dissected into dorsal and ventral fragments. The fragments were macerated, separately, and cells (green and blue dots, dorsal and ventral cells, respectively) were isolated by FACS into groups of 500 cells (STAR Methods; eight dorsal samples and six ventral samples). The samples were processed (STAR Methods) and; bottom panel: tested by qPCR for the expression of PRDM1-1 and kal1, with their expression normalized by smedwi-1 expression (green and blue squares represent 500-cell samples, dorsal or ventral, respectively). Significance of difference in expression was tested by Student’s t-test and corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using Bonferroni correction. Overlaid are 95% bootstrap-calculated confidence intervals.

We examined the spatial distribution of PRDM1-1+ ζneoblasts by whole-mount FISH, and detected them only on the dorsal side (Fig 5C). Conversely, kal1+ ζneoblasts were found only ventrally (Fig 5C, S6D). We quantified the positions of kal1+ neoblasts along the DV axis by imaging transverse sections (Fig 5D, S6E), which were labeled for major anatomical structures (intestine, madt (Wenemoser and Reddien, 2010); and DV-boundary epidermis, laminB). kal1+ cells were always ventral to the intestine or next to the DV-boundary epidermis (Fig 5D–E). We divided each transverse section into 10 regions along the DV axis and counted the number of kal1+ neoblasts in each region (Fig 5E; STAR Methods). The majority (79%) of the kal1+ neoblasts were found in the two regions above the ventral epidermis (Fig 5E), and notably kal1+ neoblasts were not found in any of the dorsal regions. Utilizing ζneoblast markers, we found that kal1+ ζneoblasts were closer to the ventral epidermis, and that ζneoblasts more internally did not express kal1 (Fig 5F, S6F). These findings show that kal1 expression in neoblasts is correlated to the position of the cells across the DV axis. To further confirm these results, we isolated groups of 500 dividing neoblasts by FACS from either dorsal or ventral planarian fragments. We performed qPCR analysis on eight dorsal and six ventral neoblast groups (STAR Methods) and found that in dividing neoblasts, PRDM1-1 was significantly overexpressed on the dorsal side, and by contrast, kal1 was significantly overexpressed on the ventral side (Fig 5F). These findings demonstrate that gene expression in neoblasts within a lineage reflects their position in the animal. This positional identity is likely subsequently propagated to the spatially divergent epidermal progenitors, which ultimately generate regionally appropriate mature epidermal cells.

The BMP signaling gradient affects the DV identity of ζneoblasts and epidermal progenitors

The dorsal and ventral identities found in ζneoblasts raised the possibility that ζneoblasts respond to an extracellular signal to activate position-specific transcriptional programs. In planarians, many genes regulating adult patterning are expressed in muscle cells (Witchley et al., 2013), but the connection between patterning gene expression in muscle and neoblast states is poorly understood. bmp4 expression from dorsal muscle cells (Witchley et al., 2013) regulates the polarization of the DV axis (Molina et al., 2007; Orii and Watanabe, 2007; Reddien et al., 2007), and thus it is an attractive candidate for regulating the emergence of DV identities in ζneoblasts. Importantly, the expression of kal1 was spatially opposed to bmp4 expression (Fig 5D). bmp4 inhibition leads to progressive ventralization of the animals (Molina et al., 2007; Orii and Watanabe, 2007; Reddien et al., 2007), resulting in ventral features appearing dorsally. We assessed if BMP signaling actively represses the expression of ventral epidermal genes in dorsal epidermal lineage cells. We inhibited bmp4 and examined kal1 expression in two scenarios (Fig 6A; STAR Methods). First, in intact animals, 10 days following bmp4 inhibition, a time-point at which animals appeared indistinguishable from controls (Fig 6A) and; second, in regenerating animals, 10 days following amputation, and a total of 20 days after initiating bmp4 inhibition. In this condition, the animals displayed major morphological defects reflecting ventralization of the regenerating tissue (Fig 6A). Following RNAi, kal1+ cells were found dorsally in bmp4 RNAi animals (Fig 6B), but never dorsally in controls (Fig 6B). Importantly, kal1+ Early Stage progenitors (prog-2+) were present dorsally in both intact and regenerating bmp4 RNAi animals (Fig 6B). Furthermore, kal1+ ζneoblasts were detectable in bmp4 RNAi animals dorsally (Fig 6C) 10 days from the beginning of the experiment, suggesting that proximity to a BMP source represses the ventral ζneoblast identity.

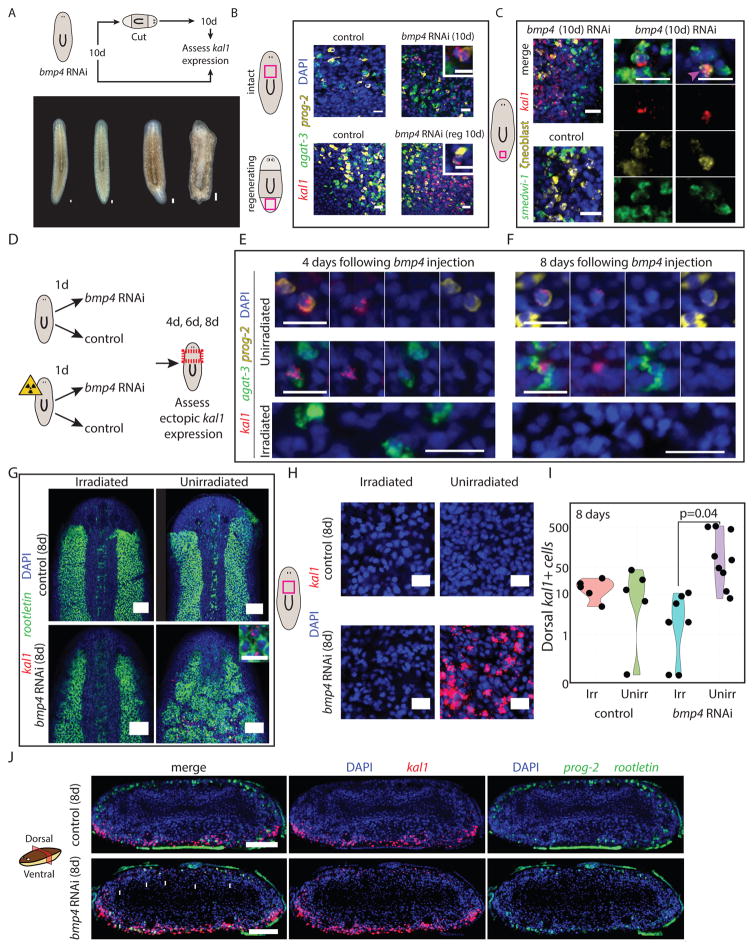

Figure 6. Planarian ζneoblast gene expression is regulated by extracellular positional signaling.

(A) bmp4 was inhibited by RNAi (STAR Methods), and 10 days following the first feeding of three, animals were either fixed or cut and allowed to regenerate for 10 days (upper panel). Animals did not have any visible defects prior to cutting (bottom panel), but following cutting and regeneration, they displayed major morphological defects, as previously reported (Molina et al., 2007; Reddien et al., 2007). (B) kal1 expression was observed 10 days following bmp4 RNAi on the dorsal surface, but never in control animals. Shown are animals before cutting (top) and animals at 10 day following regeneration (labeled reg 10d). Insets show a dorsal cell in bmp4 RNAi animal that co-expresses an Early Stage marker (prog-2) and kal1, demonstrating that reduction in BMP expression is sufficient for the appearance of ventral markers dorsally. Inset scale bar = 10 μm. (C) kal1 expression is observed in dorsal ζneoblasts, suggesting that ζneoblasts sense bmp4 expression in their environment and specify their positional gene expression accordingly. At day 10 following bmp4 inhibition animals displayed kal1 expression dorsally (left panel). Middle panel: In bmp4 RNAi animals, we detected dorsal kal1+ cells that also express smedwi-1 (a pan-neoblast marker), and ζneoblast markers (combination of soxP-3 and zfp-1, (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014)), indicating that they were indeed epidermal neoblasts (white arrow). Right panel: In addition, we identified kal1+/ζneoblast+ cells that did not express smedwi-1, suggesting that they are more differentiated epidermal progenitors. Scale bar = 20 μm. (D) Animals were divided into two cohorts, one of which was lethally irradiated on day zero; the other was unperturbed. Half of the animals each cohort received a single injection of either bmp4 dsRNA or a control dsRNA. Animals were fixed and analyzed at day four, day six and day eight following injection. (E–F) At days four and eight following bmp4 dsRNA injections, epidermal progenitors on the dorsal side (prog-2+ or agat-3+ cells, top and middle panels, respectively), which expressed kal1, were detectable. Conversely, kal1+ dorsal epidermal progenitors were not detected in irradiated animals. At day eight following irradiation, epidermal progenitors are completely ablated. See also Fig S7A. Scale bar = 20 μm. (G) The dorsal expression of rootletin in the irradiated bmp4 animals is indistinguishable from control animals. Conversely, in three of eight unirradiated bmp4 RNAi animals, the dorsal rootletin expression resembled the ventral surface of the animal. See Fig S7B. Scale bar = 100 μm. Inset shows rootletin+ cells expressing kal1. Inset scale bar = 20 μm. (H) Expression of kal1 in dorsal pre-pharyngeal regions. Only unirradiated bmp4 RNAi had dorsal expression. Scale bar = 20 μm. (I) Quantification of the number of kal1+ cells on the pre-pharyngeal dorsal region of each animal (black dot) analyzed. Significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. Groups labeled Irr and Unirr represent irradiated and unirradiated groups, respectively. (J) Transverse section showing the spatial distribution of kal1+ cells in control and bmp4 RNAi animals. kal1+ cells were never found in the middle of the animal, despite ectopic expression in all bmp4 RNAi sections analyzed (white arrows). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Neoblasts are required for responding to changes in BMP signaling

The outcome of bmp4 RNAi on epidermal lineage cells at their various stages, ventralization, could result from a response only in neoblasts, which produce the lineage, or a response in neoblasts and post-mitotic cells of the lineage. To distinguish between these possibilities, we tested whether ventralization of the epidermal lineage following bmp4 RNAi required neoblasts. Animals were split into two groups (Fig 6D), with the first group lethally irradiated on day zero and the second unirradiated. Lethal irradiation ablates all neoblasts by 24 hours post-irradiation but post-mitotic epidermal progenitors persist for up to 6 days as they transit towards differentiation (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). At 24 hours post-irradiation, half of each group was injected with bmp4 or control dsRNA. At four, six, or eight days following injection animals were fixed and analyzed for the expression of kal1 by FISH (Fig 6E–I). Numerous ectopic kal1+ progenitors were present in unirradiated bmp4 RNAi animals, at all time points examined (Fig 6E–F, S7A). Moreover, kal1 expression in the mature dorsal epidermis was detected eight days following injection (Fig 6G). By contrast, we did not detect kal1 expression in progenitors or mature epidermal cells on the dorsal side of animals that were irradiated prior to bmp4 inhibition (Fig 6E–I). Next, we examined the expression of rootletin, which is normally spatially restricted to dorsal epidermis and expressed ubiquitously in ventral epidermis (Fig S7B). Dorsal expression of rootletin was expanded and resembled the ventral side in 3/8 unirradiated bmp4 injected animals (Fig 6G). This transformation did not occur in animals that were irradiated prior to the injection (100%; Fig 6G). Finally, we quantified the number of dorsal kal1+ cells, and confirmed our observations that ectopic kal1 expression was only present in unirradiated animals following bmp4 inhibition (Fig 6H–I). These findings suggest that within the epidermal lineage, it is primarily ζneoblasts that respond to BMP signaling. Finally, we examined the spatial distribution of the ectopic kal1+ cells following bmp4 RNAi by imaging transverse sections of unirradiated bmp4 and control RNAi animals (Fig 6J). We found, in all affected animals, that ectopic kal1+ cells appeared only near the dorsal epidermis, and not in the interior of the animal (Fig 6J). Since we observed (Fig 5F, S6F) that kal1+ ζneoblasts are generally closer to the epidermal surface than kal1-ζneoblasts, this result indicates that kal1 expression is dependent not only on DV position, but also on proximity to the periphery of the animal, which might indicate a more mature cell state that responds to BMP levels. Therefore, we suggest that ζneoblasts sense the BMP levels in their environment and obtain a DV spatial identity, promoting cell type diversity to form region-appropriate epidermis.

Discussion

The body plan of even relatively simple animals is constructed of diverse, spatially arranged cell types. Adult planarians can replace all cell types during tissue turnover or regeneration through neoblast differentiation and integration of their progeny into organs and tissues (Reddien and Sanchez Alvarado, 2004). Therefore, the molecular signals that specify neoblasts and their descendants towards the appropriate cell types are important for understanding tissue turnover and regeneration. Equally important is understanding how cells within a particular lineage acquire unique functions based on their position in the animal (Lavin et al., 2014). These functions are often essential for basic activities. For example, the production of spatially arranged ciliated epidermis is essential for normal planarian motility (Glazer et al., 2010). A major challenge in identifying regulators of this process is that cell population-scale analyses often utilize cells that are heterogeneous with regards to cell type, differentiation state, and location within the animal. Therefore, single-cell analyses are highly advantageous for studying where, when, and how specialization emerges within a cell population.

Expression of spatially restricted epidermal identities in the epidermal lineage

We used the planarian epidermis to study the location, timing, and mechanism of spatially restricted epidermal identity acquisition during differentiation (Fig 7). We first characterized the different spatiallyrestricted identities that are found in the epidermis and then analyzed, using SCS and FISH, the transcriptomes of epidermal progenitors from throughout the lineage. We identified transcriptional programs that were dependent on the position of the cell within the animal (Fig 7A–B). Importantly, position-specific gene expression for different identities emerged at different stages of maturation. For example, the spatially restricted expression of DYRK4 (Fig 1B–C, S4D) was detectable only in the mature epidermis. The expression of ovo-2, on the other hand, could be found both in the mature epidermis and in a pattern similar to its ultimate epidermal pattern in migratory, mesenchymal, Late Stage progenitors (Fig 1B–C, Fig 3E). The expression of genes encoding cilia components was observed by FISH in Early Stage progenitors (Fig 2B–C, Table S4), and SCS suggested that some cilia components were already expressed in neoblasts (Table S4). In fact, Duncan et al. reported recently that some cilia components, such as cfap53 and rsph6A, are expressed in neoblasts, suggesting that cilia specification might occur in mitotic cells (Duncan et al., 2015). Importantly, DV-restricted gene expression was found even at the top of the epidermal lineage, in ζneoblasts (Fig 7C), which have at least eight days and multiple stages to transit before they have fully matured and migrated to their final destination (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014).

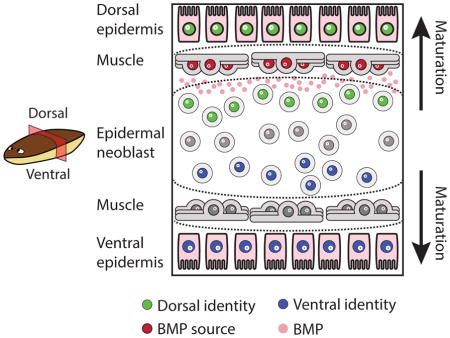

Figure 7. Model for planarian epidermal differentiation.

(A) Top panel: Planarian epidermal cells mature in a spatiotemporally defined sequence, in which progenitors go through several transitions defined by cellular morphology and spatial distribution. Bottom panel: Genes that are associated with distinct epidermal identities are expressed in all stages of the epidermal maturation, in a spatially-defined manner. Some of these genes are already expressed in ζneoblasts suggesting that ζneoblasts sense their position in the animal. (B) Some spatially-restricted epidermal identities are pre-patterned in epidermal progenitors. The model presents a view of a transverse cross-section. Dorsal is up. Medial mature epidermal cells (M; Large shapes) express ovo-2 (yellow nuclei), whereas lateral cells do not (L; purple nuclei). FISH analysis of epidermal progenitors determined that epidermal progenitors near the midline already express ovo-2 (yellow), whereas lateral epidermal progenitors do not (purple). (C) The specification of ζneoblasts to ventral (kal1+) identities is repressed by bmp4 expression from dorsal muscle cells (red elongated cells). ζneoblasts, which are in proximity to the BMP source, can express dorsal markers (PRDM1-1+; green circles), which is correlated with the emergence of additional dorsal epidermal identities. By contrast, cells that are far from the BMP source can specialize to ventral progenitors (kal1+; blue circles), which are associated with ventral epidermal identities. Inhibition of BMP signaling results in the emergence of kal1+ ζneoblasts dorsally. (D) BMP inhibits the expression of genes associated with a ventral identity in dorsal ζneoblasts. Inhibition of BMP leads to emergence of ventral identities dorsally.

The epidermis is a model for generation of regionally appropriate cell types

Planarian epidermal progenitors have been studied in multiple reports, with findings focusing on phases of epidermal maturation (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Tu et al., 2015; van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2015). Less emphasis has been given to the distinct cellular identities individual cells can acquire, and the spatiotemporal regulation of these distinct identities.

The emergence of distinct gene expression domains in the planarian epidermis (e.g. ovo-2 and DYRK4 at the dorsal epidermis; laminB in the DV boundary; DCLK2 at the ventral epidermis; Fig 1B–C) is very likely regulated by multiple mechanisms. Our analysis demonstrated that patterning molecules, such as BMP (Molina et al., 2011; Reddien et al., 2007) and Wnt5 (Adell et al., 2009) were essential for the normal formation of some of these patterns. Interestingly, the major source of these factors is muscle cells at distinct regions of the animal (Witchley et al., 2013). We hypothesize that progenitors for regeneration and tissue-maintenance sense the levels of patterning factors at their location, and respond by activating a region-appropriate transcriptional program. This hypothesis is consistent with several observations made on regional gene expression in planarians: First, patterning molecules are constitutively expressed in planarians (Reddien, 2011); second, RNAi of these molecules leads to patterning defects in intact and regenerating animals (Reddien, 2011), and finally, with the rapid establishment of regionally-appropriate gene expression of patterning factors following injuries, prior to the generation of regionally-appropriate cell types (Gurley et al., 2010; Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Witchley et al., 2013; Wurtzel et al., 2015). Importantly, it has been unclear at what stage of differentiation cells respond to these signals, and in particular whether it is mature cell types, post-mitotic progenitors, and/or neoblasts that respond.

DV gene expression distinguishes populations of epidermal progenitors and ζneoblasts

To identify the cells that respond to positional cues, we first searched for the earliest discernable transcriptional differences between spatially distinct epidermal lineage cells. Using SCS on samples obtained from dorsal or ventral regions, we identified 23 genes that were potentially expressed in a regionally restricted manner at a very early stage of differentiation. Remarkably, the expression of two genes was sufficient to identify the DV-location of the vast majority of Early Progenitors (PRDM1-1 for dorsal cells and kal1 for ventral cells). Furthermore, these genes were expressed in spatially divergent epidermal neoblast populations, as observed by FISH, SCS, and qPCR analysis. These results demonstrated that ζneoblasts are heterogeneous in a manner that is explained best by their position within the animal (Fig 7C–D), which suggests that ζneoblasts can respond to positional cues.

Neoblasts respond to BMP levels by acquiring a DV-positional identity

One positional cue, bmp4, is expressed from dorsal muscle cells (Witchley et al., 2013) in a gradient that is strongest at the midline. It promotes acquisition of dorsal tissue identities, and its inhibition causes progressive ventralization of the animal (Molina et al., 2007; Orii and Watanabe, 2007; Reddien et al., 2007). Strikingly, following a short bmp4 RNAi treatment, expression of a ventral gene (kal1) appeared dorsally in epidermal neoblasts and their progeny. Regions in the dorsal epidermis, normally devoid of cilia, co-expressed kal1 and rootletin in these bmp4(RNAi) animals, indicating that some ectopic kal1+ cells adopted a ventral functional identity. Importantly, kal1+ ζneoblasts were largely found closer to the epidermal surface than kal1-ζneoblasts, indicating that kal1 expression is dependent not only on DV position but also on proximity to the periphery of the animal. This might indicate that as ζneoblasts move peripherally, they mature to a cell state that responds to patterning signals.

Following ablation of neoblasts by lethal irradiation, however, bmp4 inhibition did not result in dorsal expression of kal1 or in ectopic rootletin expression. Therefore, our data suggest that it is the neoblasts that are primarily capable of adopting ectopic ventral identities in response to BMP inhibition, which were then propagated to their progeny. Furthermore, this suggests that mature epidermal identities are not plastic even in response to changes in the BMP signaling environment.

Because bmp4 is expressed largely exclusively in dorsal muscle cells (Witchley et al., 2013), we suggest that neoblasts read a BMP gradient established by dorsal muscle, and respond by activating a DV-appropriate transcriptional program, which subsequently generates the correct types of epidermis (Fig 7B–D). Planarian regeneration requires two components: collectively pluripotent neoblasts (Adler and Sanchez Alvarado, 2015; Reddien, 2013), which are the cellular source for all new tissues, and a set of positional signals (Reddien, 2011), which are expressed from muscle cells (Witchley et al., 2013), that provide the patterning information required for regeneration. Our results support a model in which neoblasts, within a lineage, respond directly to the muscle-derived positional signals in order to produce the required regionally appropriate cell types. This model helps explain how planarians maintain a complex body plan during tissue turnover and in response to injury.

STAR Methods

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Digoxigenin-AP, Fab fragments | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#11093274910 |

| Anti-Digoxigenin-POD (poly), Fab fragments | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#11633716001 |

| Anti-Fluorescein-AP, Fab fragments | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#11426338910 |

| Anti-DNP HRP Conjugate | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#FP1129 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-acetylated Tubulin | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#T7451 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (HRP) | Abcam | Cat#ab6789 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli DH10B | Invitrogen | Cat#18297010 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Ammonium thiocyanate | Sigma Aldrich | Cat#221988 |

| TRIzol | ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc. | Cat#15596018 |

| Buffer TCL | QIAGEN, inc. | Cat#1031576 |

| Western Blocking Reagent | Roche | Cat#11921673001 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| TruSeq RNA library prep kit V2 | Illumina, Inc. | Cat#RS-122-2001/2 |

| Nextera XT | Illumina, Inc. | Cat#FC-131-1096 |

| KAPA HiFi HotStart PCR ReadyMix | Kapa Biosystems | Cat#KK2602 |

| High Sensitivity DNA Qubit kit | Life Technologies | Cat#Q32854 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Sequencing data (single-cell RNA sequencing and RNA sequencing); Accession PRJNA353867 | This paper | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/353867 |

| S. mediterranea transcriptome assembly (dd_v4) | Liu et al., 2013 | http://planmine.mpi-cbg.de/ |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Schmidtea mediterranea, asexual | Reddien lab | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer for qPCR for agat-1 (fw): CCTAAAAGGCGAAGGTGTGACT | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for agat-1 (rev): TGCAACATCCAAACCGACAGA | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for laminB (fw): TGTGGGTAGCCTTTTCTTCTCCC | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for laminB (rev): CGCAAGGTTCAGGTGATCCG | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for kal1 (fw): TCTGTGTGCCCTCTTGTACG | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for kal1 (rev): CAGATTTTCCGGCTGAGAAG | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for PRDM1-1 (fw): CGGTGAACGACCTTTCAAGT | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for PRDM1-1 (rev): TCAAACAAACCGAACACTCG | This paper | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for smedwi-1 (fw): GTCTCAGAAAACAACTAAAGGTACAGCA | van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Primer for qPCR for smedwi-1 (rev): TGCTGCAATACACTCGGAGACA | van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGEM-T easy vector system | Promega | https://www.promega.com/products/pcr/pcr-cloning/pgem_t-easy-vector-systems/ |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| R v3.2.3 | The R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| edgeR v3.6.8 | Robinson et al., 2010 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html |

| bedtools v2.20.1 | Quinlan and Hall, 2010 | http://quinlanlab.org/tutorials/bedtools/bedtools.html |

| novoalign v2.08.02 | NovoCraft Technologies | http://www.novocraft.com/products/novoalign/ |

| mafft v7.017b | Katoh et al., 2009 | http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/ |

| Seurat v1.2 | Satija et al., 2015 | http://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| RaXMLv7.2.6 | Stamatakis. 2006 | http://sco.h-its.org/exelixis/software.html |

| PANTHER v11 | Mi et al., 2016 | http://www.pantherdb.org/tools/hmmScoreForm.jsp |

| BLAST+ v2.4.0 | Camacho et al., 2009 | https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| FIJI/ImageJ v1.51d | Schindelin et al., 2012 | http://imagej.net/Fiji |

| Other | ||

| Planarian Single cell RNA sequencing resource | Wurtzel et al., 2015 | https://radiant.wi.mit.edu/ |

| Mapping of labels in figure to contig IDs in transcriptome assembly | This paper, Table S6 | N/A |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, Peter W. Reddien (reddien@wi.mit.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

For all experiments, a clonal strain of asexual Schmidtea mediterranea was used. Animals were cultured at 20°C in the dark and were fed weekly with beef liver. Prior to gene inhibition experiments animals were starved for 7 days.

METHOD DETAILS

Gene labeling and nomenclature

Previously published planarian genes, and genes for which we performed phylogenetic (PRDM1-1, ovo-2, ovo-3) or domain-structure analysis (kal1) appear in italics throughout the text and the figures. Uppercase labels are the human best-blast hits (blastx; E-value < 10−5; (Camacho et al., 2009)), or genes not named with detailed analysis (such as phylogenetic analysis). Numeric labels with “dd_” prefix are shown for genes without human best-blast hit; instead the contig id in the dd_v4 transcriptome assembly was used (Liu et al., 2013). Mapping of gene labels in figures to contig ids is found in Table S6.

Planarian epidermis isolation and RNAseq library preparation

Uninjured and injured (3 hours post amputation) animals were used for epidermis extraction separately. Epidermal cells were isolated by incubating planarians in a solution of 3.8% Ammonium Thiocyanate [Sigma-Aldrich 221988-100G] as previously described (Trost et al, 2007) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 minutes. The dorsal or ventral epidermal cells were scraped off the worms, separately, with a needle pulled from a borosilicate glass capillary [Sutter Instrument Co. B100-75-15]. Epidermal cells were transferred into a collection tube on ice. Cells were spun down at 300G for 5 minutes at 4°C, resuspended in PBS, and spun down again. Cells were resuspended in 0.25 mL of TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc. #15596018) and stored at −80°C. In parallel, whole animal controls were put in TRIzol. RNA extraction for samples in TRIzol was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol. For each sample, 1 μg of RNA was used for RNA sequencing library preparation using the TruSeq RNA library prep kit V2 (Illumina, Inc., Cat#RS-122-2001/2) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq.

Differential expression analysis of epidermis-enriched RNAseq libraries

Sequenced RNA-seq libraries were mapped as recently described (Wurtzel et al., 2015) using Novoalign v2.08.02 with parameters [-o SAM -r Random] to the S. mediterranea dd_Smed_v4 transcriptome assembly (Liu et al., 2013). Read count per contig was calculated with bedtools v2.20.1 (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) for each library. Short contigs (<350) were removed from further analysis, and reads mapped to different contig isoforms summed to represent a single contig. Differentially expressed genes were called using EdgeR v3.6.8 (Robinson et al., 2010), requiring minimal fold-change of 2 and FDR smaller than 1E-4.

Single-cell collection by FACS and qPCR

Animals were subjected to 2 transverse amputations to generate pre-pharyngeal fragments. The fragments were further dissected into dorsal, ventral, and lateral fragments (Fig 2A). Samples were macerated, stained with Hoechst (1:25) and propidium iodide (1:500), and 2C cells were sorted to plates containing lysis buffer (TCL buffer; QIAgen, inc.), as recently described (Wurtzel et al., 2015). Following reverse transcription and cDNA amplification (Picelli et al., 2013; Wurtzel et al., 2015), qPCR was performed on plates (total 1,096 cells) to identify and isolate agat-1 expressing cells (forward and reverse sequences, CCTAAAAGGCGAAGGTGTGACT and TGCAACATCCAAACCGACAGA, respectively), with the following program [95°C (30s), 40 cycles (95°C 3s, 60°C 30s)]. Similarly, cells from the lateral region were also screened for the expression of the dorsal-ventral (DV) epidermal boundary marker laminB (forward and reverse sequences, TGTGGGTAGCCTTTTCTTCTCCC and CGCAAGGTTCAGGTGATCCG, respectively). Cells displaying Ct value of 25 or less were considered as expressing the assayed gene and were selected for single-cell RNA sequencing (SCS) library preparation.

Single-cell RNA sequencing library preparation

Libraries were prepared following a published protocol (Picelli et al., 2014) with previously described modifications (Wurtzel et al., 2015).

In Situ Hybridizations

Nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) colorimetric whole-mount in situ hybridizations (ISH) were performed as previously described (Pearson et al. 2009). Fluorescence in situ hybridizations (FISH) were performed as previously described (King and Newmark 2013) with minor modifications. Briefly, animals were killed in 5% NAC and treated with proteinase K (2 μg/ml). Following overnight hybridizations, samples were washed twice in each of pre-hybridization buffer, 1:1 pre-hybridization-2X SSC, 2X SSC, 0.2X SSC, PBS with Triton-X (PBST). Subsequently, blocking was performed in 0.5% Western Blocking Reagent (Roche, 11921673001) and 5% inactivated horse serum PBST solution when anti-DIG or anti-DNP antibodies were used, and in in 1% Western Blocking Reagent PBST solution when an anti-FITC antibody was used. Post-antibody binding washes and tyramide development were performed as described (King and Newmark 2013). Peroxidase inactivation with 1% sodium azide was done for 90 minutes at room temperature.

Immunostainings

Immunostainings for acetylated-tubulin were performed as previously described (Reddien et al., 2007). Immunofluorescence (IF) and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) signals were developed using tyramide conjugated fluorophores generated from AMCA, fluorescein, rhodamine (Pierce), and Cy5 (GE Healthcare) N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters as previously reported (Hopman et al., 1998).

Irradiation

Animals were irradiated using Gammacell 40 dual 137cesium sources (6000 rads) and were used for experiments 24 hours following irradiation, when all neoblasts are ablated (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008).

Gene cloning and transformation

Genes were cloned as previously described (Wurtzel et al., 2015). Briefly, gene-specific primers were used to amplify gene sequences of planarian cDNA. Amplified sequences were cloned into pGEM vectors following the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega), and transformed to E. coli DH10B by heat-shock. Bacteria were plated on agarose plates containing 1:500 carbenicillin, 1:200 Isopropylthio-b-D-galactoside (IPTG), and 1:625 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal) for overnight growth. Colonies were screened by colony PCR and gel electrophoresis. Plasmids were extracted from positive colonies and subsequently validated by Sanger-sequencing (Genewiz, Inc.).

Double-stranded RNA synthesis and RNAi experiments

Gene inhibition was done by feeding the animals with dsRNA corresponding to the target gene. dsRNA was synthesized as previously described (Wurtzel et al., 2015) following a published protocol (Rouhana et al., 2013). Animals were starved for 7 days prior to experiments and were kept in the dark for at least 2 hours before each feeding. Animals were fed 6 times, unless stated otherwise, every 3 days by mixing the dsRNA with homogenized beef liver (1:3). Following the RNAi feedings, animals were cut and allowed to regenerate for 8 days, while being monitored for defects. Following the 8-day recovery period, animals were fixed and analyzed by FISH. dsRNA injections, using Drummond Nanoject II, were performed in the prepharyngeal region. bmp4 inhibition by injection was performed using a single injection.

Isolation of cells by FACS for Cell FISH

Cell suspension was prepared from whole animals or from fragments as recently described (Wurtzel et al., 2015). FACS gating was performed for previously described cell populations (Hayashi et al., 2006).

qPCR of dividing neoblasts isolated from dorsal or ventral regions

Animals were cut transversely and then dorsal and ventral fragments were isolated. Fragments from different animals were pooled (>20) and macerated to a single cell suspension, as recently described (Wurtzel et al., 2015). Groups of 500 dividing neoblasts, from the dorsal and ventral samples, were sorted using a flow cytometer, separately (dorsal replicates: n = 8; ventral replicates: n = 6) into plates containing 30 μl of lysis buffer (TCL buffer; QIAgen, inc.). RNA from samples was converted to cDNA and amplified using the Smart-seq V2 (Picelli et al., 2013) protocol with minor modifications (Wurtzel et al., 2015). The amplified cDNA library concentrations were measured using Qubit fluorometer (Life Technologies; Q32854) and sample concentrations were normalized to 5 ng/μl. Expression of the target genes was measured in each sample using qPCR. qPCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7500-fast RT-PCR machine for smedwi-1 (forward and reverse primer sequences: GTCTCAGAAAACAACTAAAGGTACAGCA and TGCTGCAATACACTCGGAGACA, respectively), PRDM1-1 (forward and reverse primer sequences: CGGTGAACGACCTTTCAAGT and TCAAACAAACCGAACACTCG, respectively), and kal1 (forward and reverse primer sequences: TCTGTGTGCCCTCTTGTACG and CAGATTTTCCGGCTGAGAAG, respectively) with the following program [95°C (30s), 40 cycles (95°C 3s, 60°C 30s)], with at least two technical replicates per sample. The measured Ct values of either kal1 or PRDM1-1 were normalized by the sample expression of smedwi-1, a pan-expressed neoblast gene (Reddien et al., 2005). Student t-test was used for differential expression analysis of between dorsal- and ventral-isolated samples, and p values were corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using the Bonferroni correction.

Analysis of single cell RNA sequencing data

Gene expression data were mapped to the dd_Smed_v4 assembly (Liu et al., 2013) as previously described (Wurtzel et al., 2015). Recently published SCS data (Wurtzel et al., 2015) prepared using the same protocol and equipment, was combined if the cells were from the epidermal lineage. Gene expression data for all cells were processed together as follows: Following mapping using Novoalign v2.08.02, a raw expression matrix was generated using custom Perl script, and expression matrix was normalized using edgeR v3.6.8 (Robinson et al., 2010). Contigs shorter than 450 nt were removed. Cells expressing less than 1000 or more than 7800 genes were removed from further analysis to ensure low-quality cells, or potentially contaminated samples were not included in the analysis (Wurtzel et al., 2015). Initial determination of significant principal components was performed by calling function mean.var.plot with parameters [y.cutoff = 2.5, x.low.cutoff = 2, fxn.x = expMean,fxn.y = logVarDivMean], which found 267 genes meeting these criteria. The jackstraw function [num.replicate = 200] determined principal components 1–12 as significantly contributing to cell-to-cell gene expression variance. The function pca.sig.genes was called with parameters [pcs.use = 1:12, pval.cut = 1e-5, max.per.pc = 300] and the resultant list was used for a second principal component analysis (PCA) analysis. Then, four cells were removed from the dataset [“D15.101224_DMX”, “D15.101225_DMX”, “D15.101162_DLX”, “D15.101359_L0X”], as they expressed multiple neural genes (including PC2, synapsin, and synaptotagmin), and were unlikely to be part of the epidermal lineage. tSNE was performed using the function run_tsne [dims.use = c(1:18), perplexity = 20, do.fast = T]. Next, data was clustered by DBclust_dimension [reduction.use = “tsne”, G.use = 2, set.ident = TRUE, MinPts = 3] and clusters were sorted by the buildClusterTree function [do.reorder = TRUE, reorder.numeric = TRUE, pcs.use = 1:18]. Following gene expression analysis, cluster 3 was determined to represent muscle cells, based on expression of multiple muscle markers, and was removed. Clusters 8, 11 and 12 included small number of low complexity cells and were removed as well.

Contig selection for calculating gene expression correlation

The transcriptome assembly was searched for contigs with best-blast hit description including the keywords IFT or “intraflagellar transport”. The expression of all contigs was visualized using the SCS resource (Wurtzel et al., 2015) and genes that were not exclusively expressed in ciliated cells (e.g. epidermal cells, protonephridia, ciliated neurons) were discarded. For each gene pair, Pearson correlation (r) was calculated, per cluster, and then z-transformed using Fisher z-transformation. Average was calculated on z-transformed values, per cluster, and then transformed to r.

| Contig | Best Blast hit description | ID | E-value | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dd_Smed_v4_10638_0_1 | IFT172-like protein | GQ337484.1 | 0 | Smed |

| dd_Smed_v4_11300_0_1 | intraflagellar transport 140 homolog (Chlamydomonas) (IFT140) | uc002cmb.3 | 0 | Human |

| dd_Smed_v4_5043_0_1 | IFT52-like protein | GQ337481.1 | 0 | Smed |

| dd_Smed_v4_5484_0_1 | IFT88-like protein | GQ337482.1 | 0 | Smed |

| dd_Smed_v4_7099_0_1 | intraflagellar transport 57 homolog (Chlamydomonas) (IFT57) | uc003dwx.4 | 3.00E-91 | Human |

| dd_Smed_v4_7533_0_1 | intraflagellar transport 172 homolog (Chlamydomonas) (IFT172) | uc002rku.3 | 1.00E-53 | Human |

| dd_Smed_v4_8803_0_1 | intraflagellar transport 81 homolog (Chlamydomonas) (IFT81) | uc001tqh.3 | 0 | Human |

| dd_Smed_v4_9110_0_1 | intraflagellar transport 80 homolog (Chlamydomonas) (IFT80) | uc021xgr.1 | 0 | Human |

Identification of DV-boundary epidermis transcription factors

TFs that were overexpressed in the epidermal lineage were collected from three datasets: (1) TFs enriched in one or more epidermal progenitor or mature epidermis cluster when compared to previously published SCS gene expression of other cell types (Wurtzel et al., 2015), using the Seurat v1.2 package (Satija et al., 2015) find.markers function with thresholds: [FDR < 1E-3, FC > 2]; (2) TFs that were overexpressed in bulk epidermal RNA-seq compared to whole-worm controls [FDR < 0.01, FC > 2]; or (3) that were downregulated in animals with depleted epidermal lineage (zfp-1 RNAi) using recently published RNAseq data (van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014) that were mapped to the dd transcriptome (Liu et al., 2013) and analyzed using the same approach described for the bulk epidermal RNAseq libraries data analysis with the following thresholds for significance (FDR < 0.01, FC > 2). TFs enriched in the DV boundary epidermis SCS data (Table S3) or expressed in at least half of the DV-boundary epidermis cells but in none of the other mature cell types (Fig 2E) were further analyzed by FISH and RNAi.

Microscopy and image analysis

FISH and IF images were collected using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 700). Cell counting was performed using FIJI/ImageJ v1.51d (Schindelin et al., 2012) by cropping images to a set size and counting cells using the “Cell Counter” component. The same region was used to count cells for both the controls and the experiment. Transverse sections were generated by using a scalpel and generating two transverse cuts. Measurement of spatial distribution of kal1+ neoblasts (Fig 5D) was done by imaging transverse sections, dividing each section into 10 segments of half concentric ellipses, and counting the number of kal1+ neoblasts in each section. Sections were evaluated according to their position compared to major landmarks (bmp4 expressing muscle cells, DV boundary epidermal cells, and the intestine). The number of kal1+ cells in irradiated and unirradiated bmp4 RNAi animals and controls was quantified by taking prepharyngeal images (400 μm2, 10 confocal slices, Fig 6H–I) for all animals in four groups (irradiated control, unirradiated control, irradiated bmp4 RNAi, unirradiated bmp4 RNAi). Then the file names of the images were randomized and the images were analyzed by a different researcher. Positive cells were counted using the “Cell Counter” component in ImageJ, and documented for each file. Following measurements, the file names were derandomized, and data of different groups were compared.

Calculation of the overlap fraction in epidermal progenitors

Overlap fraction was calculated for ovo-2 as follows: [Number of ovo-2+ cells expressing gene X/Number of ovo-2+ cells], where gene X represents any gene in the transcriptome for which gene expression was greater than log2(CPM+1) of 5. Overlap fraction for DCLK2 was calculated similarly. Genes expressed in a small fraction of the entire cell population (<25%) were removed as their overlap fraction was minor. Genes expressed throughout the cell population (> 66%) were also removed, to avoid confounding the results with genes expressed abundantly, such as housekeeping genes.

Phylogenetic analysis of epidermal genes

Phylogenetic analysis of PRDM1-1, ovo-2, and ovo-3 was done by multiple alignment of the protein sequences with known sequences from representative model organisms using mafft v7.017b (Katoh et al., 2009) with flag [--auto]. Then gap sequences were trimmed, and trees resolved using RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006) with flags [Substitution model: PROTCAT DAYHOFF; Matrix name: DAYHOFF; Bootstrap: 100]. kal-1 analysis was done using multiple methods: (1) Reciprocal BLASTP search [e-value < 1E-30) against the human proteome resulted in best similarity with KAL1; (2) Conserved protein domain analysis using CDART (Geer et al., 2002) and InterProScan v5.18-57.0 (Jones et al., 2014) of domain structure in model organisms and S. mediterranea; and (3) Classification based on the PANTHER database prediction using the protein sequence of the predicted planarian kal1 (Mi et al., 2016).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using R v3.2.3. Unless stated otherwise, Student’s t-test was used followed by Bonferroni correction for multiple hypothesis testing where applicable.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

RNA sequencing data generated in this study were deposited to SRA and is available under accession PRJNA353867 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/353867).

Supplementary Material

Table S1, related to Figure 1. Overexpressed genes in the planarian epidermis. Over-expressed genes (fold-change > 2 and FDR < 1E-4) in the epidermis-enriched samples compared to whole-worm controls (STAR Methods).

Table S2, related to Figure 1. Cluster assignment of single-cell RNA sequencing samples. Cluster assignment of epidermal lineage cells that were analyzed in this study by single-cell RNA sequencing.

Table S3, related to Figure 1. Genes enriched in epidermal clusters identified by SCS data. Table includes over-expressed genes in the identified epidermal-lineage clusters (STAR Methods).

Table S4, related to Figure 2. Expression of core centrosome components in the epidermal lineage. Gene expression analysis in single-cell RNA sequencing of genes encoding core centrosome components based on genes identified previously (Azimzadeh et al., 2012).

Table S5, related to Figure 4. Genes enriched in dorsal or ventral Early Stage epidermal progenitors. Gene expression of Early Stage progenitors from dorsal or ventral regions was compared. The expression of 23 genes was found to be differentially expressed (fold-change > 4; FDR < 0.1; Power > 0.4), using the Seurat package (Satija et al., 2015).

Table S6, related to All Figures. Contig annotation of genes used in figures. Mapping of labels shown in figures to contig IDs that correspond to the planarian de novo transcriptome assembly, which was used in this paper (Liu et al., 2013).

Highlights.

Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals spatial patterning in a progenitor pool.

Planarian epidermal neoblasts read their position in the animal.

Position-specific transcriptional programs in progenitors generate cell-type diversity.

Patterning signals from muscle regulate epidermal neoblast positional identity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kellie Kravarik and the Reddien lab members for manuscript comments. OW was supported by an EMBO long-term fellowship, and is the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Fellow of The Helen Hay Whitney Foundation. We acknowledge NIH (R01GM080639) support. PWR is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and an associate member of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

OW, IMO, and PWR conceived the project and designed experiments. OW, IMO, and PWR performed all experiments. OW analyzed high-throughput sequencing data. OW, IMO, and PWR wrote the manuscript.