Abstract

Behavior therapy is effective for Persistent Tic Disorders (PTDs), but behavioral processes facilitating tic reduction are not well understood. One process, habituation, is thought to create tic reduction through decreases in premonitory urge severity. The current study tested whether premonitory urges decreased in youth with PTDs (N = 126) and adults with PTDs (N = 122) who participated in parallel randomized clinical trials comparing behavior therapy to psychoeducation and supportive therapy (PST). Trends in premonitory urges, tic severity, and treatment outcome were analyzed according to the predictions of a habituation model, whereby urge severity would be expected to decrease in those who responded to behavior therapy. Although adults who responded to behavior therapy showed a significant trend of declining premonitory urge severity across treatment, results failed to demonstrate that behavior therapy specifically caused changes in premonitory urge severity. In addition, reductions in premonitory urge severity in those who responded to behavior therapy were significant greater than those who did not respond to behavior therapy but no different than those who responded or did not respond to PST. Children with PTDs failed to show any significant changes in premonitory urges. Reductions in premonitory urge severity did not mediate the relationship between treatment and outcome in either adults or children. These results cast doubt on the notion that habituation is the therapeutic process underlying the effectiveness of behavior therapy, which has immediate implications for the psychoeducation and therapeutic rationale presented in clinical practice. Moreover, there may be important developmental changes in premonitory urges in PTDs, and alternative models of therapeutic change warrant investigation.

Keywords: Tics, Psychotherapy, Behavior Therapy, Habituation

INTRODUCTION

Persistent Tic Disorders (PTDs) such as Tourette’s Disorder (also known as Tourette’s syndrome) are neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by the presence of tics for at least 1 year (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Tics are repetitive motor movements (e.g., hard blinking and head jerking) and vocalizations (e.g., grunting and repetition of words or phrases) that can cause significant functional impairment and distress (Houghton, Alexander, & Woods, 2016). PTDs primarily affect children and have a waxing-to-waning developmental course. The age of tic onset tends to be between 4 and 6 years, and tics reach peak severity between ages 10–12 and often decline in severity during late adolescence (Bloch & Leckman, 2009). However, nearly one quarter of individuals with PTDs experience chronic tic symptoms into adulthood (Bloch & Leckman, 2009; Groth, Debes, Rask, Lang, & Skov, 2017; Leckman et al., 1998).

PTDs can be treated effectively with behavior therapy (Capriotti, Himle, & Woods, 2014; Cook & Blacher, 2007; Piacentini et al., 2010; McGuire et al., 2014; Wilhelm et al., 2012), which is thought to facilitate conditioning experiences central to promoting tic reduction. Behavioral interventions approach tics as being initiated by aberrant neural functioning but perpetuated largely by conditioning processes surrounding core PTD symptoms (Conelea & Woods, 2008; Himle, Woods, Piacentini, & Walkup, 2006; Himle et al., 2014). Indeed, a neurobehavioral perspective on tics acknowledges that tics are supported by motor hyperexcitability within fronto-striatal neural circuits (Albin & Mink, 2006), but tics are maintained, in part, by operant reinforcement and respondent associations (reviewed by Himle et al., 2006). One crucial aspect of these conditioning processes involves the functional relation between certain somatic phenomena, known as premonitory urges (PMUs), and tics (reviewed by Houghton, Capriotti, Conelea, & Woods, 2014).

A substantial body of literature has shown that individuals with PTDs experience PMUs, which are aversive sensations that precede and accompany tics (Cohen & Leckman, 1992; Kurlan, Lichter, & Hewitt, 1989; Kwak, Vuong, & Jankovic, 2003; Leckman, Walker, & Cohen, 1993; Leckman, Walker, Goodman, Pauls, & Cohen, 1994; Woods, Piacentini, Himle, & Chang, 2005). Patients describe these experiences as various feelings of unfulfillment, irritation, and musculoskeletal tension (Bliss, Cohen, & Freedman, 1980). Whereas early conceptualizations considered tics to be involuntary (Caine, Polinsky, Kartzinel, & Ebert, 1979), accounts of PMU phenomena suggested that tics are better characterized as somewhat volitional and instigated by highly aversive PMUs, which are alleviated upon ticcing (Evers & van de Wetering, 1994; Kane, 1994; Lang, 1991). Several studies have supported this notion using an experimental paradigm comparing periods in which tic suppression is intermittently reinforced by monetary reward with periods when participants are instructed to tic freely and suppression is not rewarded (e.g., Capriotti, Brandt, Turkel, Lee, & Woods, 2014; Himle, Woods, Conelea, Bauer, & Rice, 2007; Woods & Himle, 2004). Results of these studies showed that tics can be suppressed for brief periods and that PMU strength increased during reinforced tic suppression and decreased during breaks from suppression. Furthermore, a recent study found that PMU strength increases prior to ticcing and decreases after ticcing (Brandt, Beck, Sajin, Baske, et al., 2016).

The neurobehavioral model of PTDs posits that the short-term reductions in PMUs following tic completion result in longer-term strengthening or maintenance of tics and PMUs (Himle et al., 2006). When individuals engage in prolonged tic suppression, they experience PMUs without ticcing, and PMUs are thought to dissipate (Woods et al., 2008). Thus, tic suppression might facilitate a PMU habituation process whereby repeated exposure to the PMU results in decreased physiological response to PMUs and similar sensory stimuli (Evers & van de Wetering, 1994; Himle et al., 2006; Hoogduin, Verdellen, & Cath, 1997; Verdellen et al., 2008; Woods, Hook, Spellman, & Friman, 2000). PMU habituation is thought to occur both within individual periods of tic suppression (i.e., within treatment sessions) and between periods of suppression (i.e., across sessions). The notion of PMU habituation through tic suppression is similar to the rationale underlying exposure and response prevention (ERP) for obsessive-compulsive disorder (Abramowitz, 1996). However, ERP-based behavioral treatments for PTDs are thought to work by having clients engage in prolonged tic suppression and learn to habituate to the accompanying increases in PMUs (Verdellen, Keijsers, Cath, & Hoogduin, 2004), whereas ERP for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) involves deliberate exposure to fear-evoking stimuli and prevention of rituals and/or avoidance behaviors.

Studies investigating PMU habituation have yielded mixed results. The first study to systematically investigate PMU habituation reported on 4 patients with Tourette’s Disorder (3 adults and 1 child) who received 10 sessions of exposure and response prevention for PTDs (ERP; Hoogduin, Verdellen, & Cath, 1997). Repeated-measures data from 3 of the 4 participants showed evidence of short-term PMU habituation within sessions (i.e., decreases in urge ratings at the end of a session relative to the beginning of those same sessions). In an open trial of 19 adults and children with PTDs who received the same ERP treatment protocol, longitudinal analyses showed evidence of PMU habituation both within and between sessions (Verdellen et al., 2008). However, three studies found a lack of evidence for within-session PMU habituation using differential reinforcement for tic suppression paradigms lasting 25–80 minutes (Capriotti, Brandt, et al., 2014; Himle et al., 2007; Specht et al., 2013).

These mixed findings may be at least partially due to methodological inconsistencies and shortcomings. First, studies examining PMU habituation have used samples of differing age ranges, despite the fact that there are important age-based differences in PMUs. Research has shown that while a majority of persons with PTDs aged 9 years or older report some type of PMU, younger children are less likely to report PMUs (Banaschewski, Woerner, & Rothenberger, 2003; Leckman et al., 1993; Woods et al., 2005), suggesting younger children may show a less clear association between PMUs and tics throughout treatment. Indeed, studies that showed positive evidence of PMU habituation included both adults and children but were weighted toward adults (Hoogduin et al., 1997; Verdellen et al., 2008). For example, the sample in Verdellen et al. (2008) had a mean age of 23, and in the study by Hoogduin et al. (1997), the three participants who showed evidence of PMU habituation were adults while the one participant showing no PMU habituation was a child. By comparison, the studies that reported a lack of evidence for PMU habituation used younger samples consisting of children and adolescents (Capriotti, Brandt, et al., 2014; Himle et al., 2007; Specht et al., 2013). These results suggest that perhaps adults but not children experience PMU habituation during behavioral treatment. A second limitation of existing evidence for or against the habituation hypothesis is that lab-based tic suppression studies, on which the findings primarily have been based, may not generalize to clinical settings and have used relatively small sample sizes with no control groups (Capriotti, Brandt, et al., 2014; Himle et al., 2007; Specht et al., 2013). As such, future research is needed to examine PMUs using (a) studies that enable differential analyses for adults and children, (b) longitudinal designs that reflect real-world behavior therapy for PTDs, and (c) large samples with control conditions.

The current study sought to examine PMU habituation as a mechanism of change within a two, large, multi-site trials of behavior therapy, based primarily on habit reversal training (HRT; Azrin & Nunn, 1973), versus supportive psychotherapy plus psychoeducation control for pediatric (Piacentini et al., 2010) and adult (Wilhelm et al., 2012) PTDs. Data from the child trial were analyzed separately from the adult trial in order to examine age-based differences. Several predictions were made to examine whether PMU habituation occurred. First, PMU severity should have decreased across time for those who received behavior therapy but not for those who received a control treatment (Hypothesis 1), particularly in those who responded to treatment (Hypothesis 2). It was also predicted that pre-to-post treatment decreases in PMU severity should mediate the relationship between treatment condition and outcome (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002) (Hypothesis 3). In addition, because some research has indicated that premonitory urges correlate positively with measures of OCD symptoms, anxiety, and depression (Eddy & Cavanna, 2013; Steinberg et al., 2009; Woods et al., 2005; Rozenman et al., 2015), exploratory analyses were conducted to determine whether reductions in PUTS scores were associated with change on any secondary outcome measures used in the clinical trials.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

In the child trial, a total of 178 children and adolescents were screened and 126 eligible youth enrolled between December 2004 and May 2007. Participants were recruited via psychiatry and psychology clinics, primary care and mental health referrals, schools, churches, community organizations, paid/public service notices, and ads in local media and on the Tourette Association of America website and newsletter. Inclusion criteria were (a) age 9–17 years, (b) Tourette’s Disorder or Persistent Tic Disorder of at least moderate severity, (c) English language fluency, and (d) IQ > 80. Children who were medication free or on a stable medication regimen were eligible to participate. For a more detailed description of inclusion criteria and sample characteristics, see Piacentini et al. (2010) and Specht et al. (2011), respectively. Participants were randomized to receive the index treatment, Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT), consisting of HRT plus functional intervention (Woods et al., 2008) (N = 61), or a comparison condition consisting of psychoeducation and supportive therapy (PST) (N = 65). By the end of the 10-week treatment phase, 5 participants (8%) had discontinued behavior therapy, whereas 7 participants (11%) discontinued supportive therapy.

In the adult trial, a total of 172 adults were screened and 122 eligible participants enrolled between December 2005 and May 2009. Participants were recruited via psychiatry and psychology clinics at major medical centers, flyers in public places, physician referrals, online advertisements, presentations at local patient organization meetings, and ads in local media. Inclusion criteria were identical to the child trial except that age was required to be ≥ 16. Participants on stable medication for at least 6 weeks were allowed to participate. See Wilhelm et al. (2012) for a more detailed description of inclusion criteria and sample characteristics. Also similar to the child trial, participants were randomized to receive 10 weeks of CBIT (N = 63) or PST (N = 59). At the end of treatment, 7 participants (11%) had discontinued behavior therapy, whereas 10 participants (17%) discontinued supportive therapy.

Assessments

The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) is a clinician-rated assessment of tic severity (Leckman et al., 1989). All current tics are rated on each dimension (score of 0–5) for motor and vocal separately and then totaled for a score of 0–25. The motor and vocal tic totals are summed for a combined total tic score (0–50). The YGTSS has adequate internal consistency (item-total correlations ranging from 0.78–0.88) and inter-rater reliability (intra-class correlation coefficients ranging from 0.52–0.99) and acceptable convergent and divergent validity (Leckman et al., 1989).

The Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS) is a self-report measure designed to assess PMU severity (Woods et al., 2005). The PUTS contains 9 items (displayed in Table 1) rated on a 4-point scale (1 = “not at all true” to 4 = “very much true”). Item responses are summed for a score ranging from 9 (no PMUs) to 36 (high PMU severity). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients = 0.79–0.85) and test-retest reliability has been reported in the acceptable to good range (two week test-retest correlations = 0.79–0.86), and concurrent validity of the PUTS is generally satisfactory (Crossley, Seri, Stern, Robertson, & Cavanna, 2014; Reese et al., 2014; Steinberg et al., 2009; Woods et al., 2005). A recent study also found that the PUTS showed convergent validity with real-time urge intensity scores on visual analogue scale (Brandt, Beck, Sajin, Anders, & Munchau, 2016). However, studies have shown that the internal consistency and convergent validity of the PUTS is poorer in children younger than 10 as compared to youths older than 10 (Steinberg et al., 2009; Woods et al., 2005).

TABLE 1.

Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS)

| Item # | Item Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Right before I do a tic, I feel like my insides are itchy. |

| 2 | Right before I do a tic, I feel pressure inside my brain or body. |

| 3 | Right before I do a tic, I feel “wound up” or tense inside. |

| 4 | Right before I do a tic, I feel like something is not “just right” |

| 5 | Right before I do a tic, I feel like something isn’t complete. |

| 6 | Right before I do a tic, I feel like there is energy in my body that needs to get out. |

| 7 | I have these feelings almost all the time before I do a tic. |

| 8 | These feelings happen for every tic I have. |

| 9 | After I do the tic, the itchiness, energy, pressure, tense feelings, or feelings that something isn’t “just right” or complete go away, at least for a little while. |

The Clinical Global Impressions – Improvement Scale (CGI-I) (Guy & Bonato, 1970) is a single-item clinician-rated measure of overall treatment response. A trained rater indicates improvement or worsening via an 8-point rating scale ranging from 1–8, with scores of “very much improved” (1) and “much improved” (2) defining treatment response. Reliability of the CGI-I has shown to be high in other disorders (i.e., schizophrenia; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.69–0.96) (Ventura, Cienfuegos, Boxer, & Bilder, 2007). Validity coefficients are also high for the CGI-I across many different psychiatric conditions in both pharmacological and psychosocial treatment paradigms (Bandelow, Baldwin, Dolberg, Andersen, & Stein, 2006; Leon et al., 1993; Leucht & Engel, 2006; Spielmans & McFall, 2006; Zaider et al., 2003).

Several other self-report questionnaires were used to measure relevant secondary outcomes in the clinical trials. In the child trial, secondary outcome measures included the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Scahill et al., 1997), the attention problems subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1991), the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale – Parent Version (Friedman-Weieneth, Doctoroff, Harvey, & Goldstein, 2009), the Child Depression Inventory (Helsel & Matson, 1984), the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders as rated by children and parents (Birmaher et al., 1997), and the Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index (Silverman, Fleisig, Rabian, & Peterson, 2010). In the adult trial, secondary outcome measures included the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Goodman et al., 1989), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck et al., 1988), and the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Steer, & Carbin, 1988).

Procedure

The child trial was conducted at 3 sites: The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The adult trial was conducted at 3 additional sites: Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Yale University, and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Each of these sites also provided collaborative support in the form of administrative procedures, data management, rater training, and quality assurance across the two studies. Archival data analysis related to the present study was performed at Texas A&M University. All institutions obtained IRB approval for the project, procedures were performed in compliance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), and the studies are publicly listed on the U.S. National Institutes of Health human subjects trial forum (ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT00218777, NCT00231985). All adult participants and parents of child participants provided written informed consent, and child participants provided assent.

Participants in both trials completed 8 sessions of treatment across 10 weeks. CBIT consisted primarily of habit reversal training (Azrin & Nunn, 1973) but also included psychoeducation, relaxation training, and a functional intervention aimed at mitigating tic triggers (e.g., anxiety, public performance) and consequences associated with increased ticcing (e.g., teasing, escape from responsibility). The control treatment, PST, consisted of psychoeducation and supportive psychotherapy (Goetz & Horn, 2005). PST precluded any instruction or advice pertaining to tic management strategies. Treatment conditions were matched in terms of time and therapist contact. For more detailed descriptions of therapeutic components, see Piacentini et al. (2010), Wilhelm et al. (2012), and Woods et al. (2008).

The current study utilized assessment data, collected from participants’ self-reports, parent-reports, as well as trained clinical evaluators masked to treatment condition, from 3 time points: baseline (0 weeks), mid-treatment (5 weeks), and post-treatment (10 weeks). Missing data were addressed via imputation techniques (Piacentini et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2012).

Statistical Analysis

To investigate the predictions that PMU severity would decline in those who received CBIT and particularly those who responded to CBIT, as compared to other participants, we conducted 2 × 2 × 3 (treatment condition x response status x time) repeated-measures ANOVA tests. For both the child and adult data, Mauchly’s tests of sphericity were rejected (X2[2] = 12.27, p < 0.001; X2[2] = 16.25, p < 0.001), so the ANOVAs were interpreted through Greenhouse-Geisser corrected results (ε = .897; ε = .863). Significant results were further investigated by conducting a one-way ANOVA and bonferroni post-hoc tests comparing the magnitude of PMU reductions across treatment between four groups of participants: participants who received CBIT and responded to treatment, participants who received CBIT and did not respond to treatment, participants who received PST and responded to treatment, and participants who received PST and did not respond to treatment.

To investigate Hypothesis 3, that reductions in PMU severity would mediate the relationship between treatment assignment and outcome, a bootstrapping regression-based technique (Hayes & Preacher, 2014) was used to measure the strength of the indirect effect of PUTS changes across treatment on the association between treatment assignment and changes in YGTSS scores from baseline to post-treatment. See Figure 1. The SPSS Macro “MEDIATE” was used to perform such analyses (Hayes, 2014). The number of bootstrap samples was set to 5000, and a 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval was used. A significant indirect effect is inferred when zero lies outside of the confidence interval.

FIGURE 1.

Proposed mediation path in which reductions in premonitory urges exert an indirect effect on the direct relationship between treatment assignment and treatment outcome (reductions in tic severity).

Finally, exploratory analyses investigating the relationship between PMU severity reductions and changes in secondary outcome measures in the clinical trials were conducted using Pearson’s correlations.

RESULTS

Child Trial

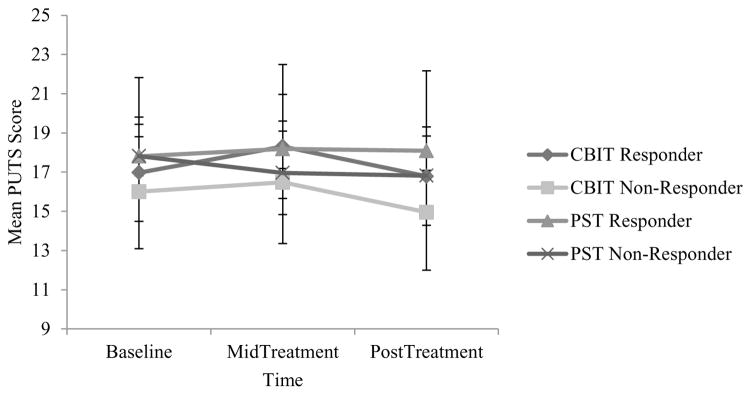

Results were inconsistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2, in that PMU severity did not decrease over time for either PST or CBIT, nor in those who responded versus those who did not respond to treatment. There were no significant main effects of time (F[2, 204] = 1.59, p = 0.21), treatment condition (F[1, 102] = 0.52, p = 0.47), or response status (F[1, 102] = 0.69, p = 0.41), and there were no significant interactions between time and treatment condition (F[2, 204] = 1.33, p = 0.27), time and response status (F[2, 204] = 0.89, p = 0.41), or time and treatment and response status (F[2, 204] = 0.03, p = 0.96). See Figure 2. These results are neither consistent with the notion that CBIT results in PMU severity reductions nor with the hypothesis that PMU severity reduction is associated with treatment gains in children who receive behavior therapy for PTDs.

FIGURE 2.

Repeated measures ANOVA of premonitory urge (PMU) trends across treatment in the child trial. Note: CBIT = Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics; PST = psychoeducation and supportive psychotherapy; PUTS = Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale. Data points reflect estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals.

When investigating whether changes in PMU mediated the relationship between treatment and outcome, there was a significant direct effect with regard to the relationship between treatment assignment and changes in YGTSS scores (F[1, 104] = 12.99, p < 0.001), but there was no significant indirect effect of PMU severity changes (Effect = 0.003; Lower Level Confidence Interval = −0.21, Upper Level Confidence Interval = 0.31). As such, results were inconsistent with Hypothesis 3.

Reductions in PMU severity were not significantly correlated with changes in OCD symptoms (r(107) = .13, p = .17), ADHD symptoms (r(106) = .11, p = .26), disruptive behavior severity (r(104) = −.05, p = .62), or anxiety symptoms as measured by child (r(106) = .12, p = .21) or parent (r(107) = .11, p = .24). However, reductions in PMU severity were significantly correlated with reductions in depression symptoms (r(103) = .27, p = .006) and anxiety sensitivity (r(105) = .27, p = .006).

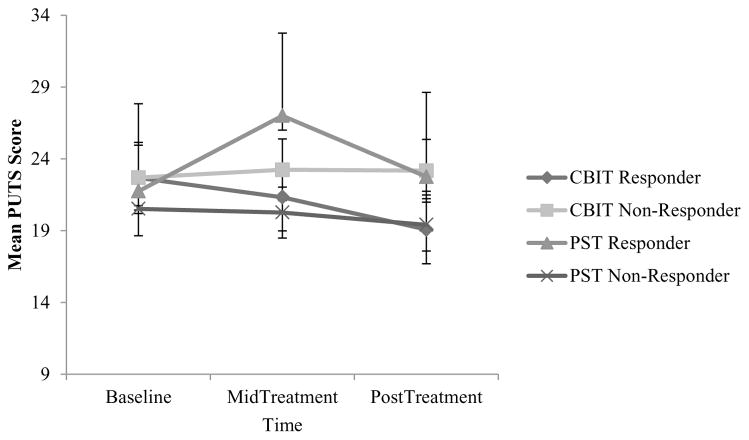

Adult Trial

Results were partially consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2. PMU severity decreased over time in all participants, but a linear trend of PMU severity reduction was only apparent in those who received CBIT and responded to treatment versus those who did not respond to CBIT and persons who received PST. There was a significant main effect of time (F[2, 190] = 4.55, p = 0.012, d = 0.439) and no significant main effects of treatment assignment (F[1, 95] = 0.003, p = 0.96) or response status (F[1, 95] = 0.30, p = 0.59). In addition, there was no significant interaction between time and treatment assignment (F[2, 190] = 2.73, p = 0.076), no significant interaction between time and response status (F[2, 190] = 2.63, p = 0.083), no significant interaction between treatment assignment and response status (F[1, 95] = 3.23, p = 0.076), and a significant three-way interaction between time, treatment assignment, and response status (F[2, 190] = 5.16, p = 0.009, d = 0.468). See Figure 3. However, although PMU severity generally decreased across the course of treatment in those who responded to CBIT versus showing no such linear trend in other groups, the reduction in PMU severity in those who responded to CBIT was not significantly larger than all other groups. The mean reduction in PUTS scores across treatment in persons who responded to CBIT (22.67 to 19.08; Mean difference = 3.58, SD = 6.39) was greater than those who did not respond to CBIT (22.69 to 23.17; Mean difference = −.52, SD = .80) (p = .015), but it was not greater than persons who received PST and either responded (21.75 to 22.75; Mean Difference = −1.0, SD = 4.32) (p = .51) or did not respond to treatment (20.52 to 19.40; Mean difference = 1.33, SD = 4.20) (p = .42).

FIGURE 3.

Repeated measures ANOVA of premonitory urge (PMU) trends across treatment in the adult trial. Note: CBIT = Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics; PST = psychoeducation and supportive psychotherapy; PUTS = Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale. Data points reflect estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals.

Results failed to support Hypothesis 3, as reductions in PMU severity did not mediate the relationship between treatment and outcome. Although there was a significant direct effect with regard to the relationship between treatment assignment and changes in YGTSS scores (F[1, 101] = 15.96, p < 0.001), there was no significant indirect effect of PMU severity changes (Effect = −0.03; Lower Level Confidence Interval = −0.67, Upper Level Confidence Interval = 0.32).

In exploring the relationship between reductions in PUTS scores and secondary outcome measures, there were no significant correlations between PMU severity reductions and changes in OCD symptoms (r(104) = −.12, p = .25), depression (r(102) = −.06, p = .52), or anxiety (r(103) = −.17, p = .09).

DISCUSSION

Findings from the current study generally do not support the notion that PMU habituation/reduction in urge severity is a mechanism of change in behavior therapy for PTDs. In children, reductions in PMU severity across treatment were not significantly related to assignment to behavior therapy or response status. Adults who received CBIT and responded to treatment showed a significant linear trend consistent with PMU severity reductions, but the magnitude of PMU severity reductions in those who responded to CBIT was not significantly greater than in all the other study groups. Moreover, reductions in PMU severity did not mediate the relationship between treatment and outcome in either children or adults, suggesting that even when PMU severity reduction occurs, this process does not drive reductions in tic severity.

Indeed, even though adults who responded to CBIT showed a trend consistent with declining PMU severity as compared to other groups, our findings do not satisfy the necessary criteria to establish that PMU reductions are mechanisms of change in adult patients. Mediation in clinical trials is evidenced by a main effect of treatment, an interaction between treatment and outcome, as well as a significant indirect effect of the proposed mediator on the relationship between treatment and outcome (Kraemer et al., 2002). Findings from the adult CBIT trial lacked the main effect of treatment but showed an interaction between time, treatment, and outcome. In addition, results showed a main effect of time. Due to the fact that adult patients who received either behavior therapy or supportive therapy showed PMU reductions and because there was no main effect of treatment, we cannot infer that PMU habituation is caused by CBIT specifically.

Present findings necessitate changes in models on the role of PMU habituation in behavior therapy for PTDs. Current models suggest that as tics are suppressed, patients are exposed to the PMU experience, which initially builds and then gradually dissipates; as this cycle is repeated times, patients come to habituate to PMUs. As a product of extensive habituation and reduced PMU severity, patients are thought to feel less compelled to tic. Instead, our results contradict this model in several ways. First, it appears that PMU severity reductions can occur in persons whose tic severity improves without explicit training in tic suppression. Perhaps individuals in the adult clinical trial who received PST benefitted from factors such as regression toward the mean or therapeutic common factors, and that as their tic severity declined they experienced concurrent reductions in PMU severity. Additionally, it is possible that PMUs do indeed habituate during CBIT, but PMU habituation is not a large effect that outpaces and drives tic reduction. Results from the adult clinical trial showed that although PMUs did show a declining trend in those who responded to CBIT relative to other groups, the size of PMU severity reductions in those who responded CBIT was not significantly larger than persons who both did and did not respond to PST. This would suggest that if PMU habituation does occur in CBIT, it is not a large change that is important for outcomes.

Although study results provide evidence for some degree of PMU severity reductions in adults who responded to behavior therapy, children who underwent treatment did not report significant global PMU reductions. This suggests that there may be important age-based differences in how PMUs are affected by tic treatment. We mentioned earlier that children are less likely to report PMUs, which would suggest that with fewer and less severe PMUs, there may be less room for PMU change across treatment. Visual inspection of Figures 2 and 3 provide support for this notion, in that baseline PMU severity was lower in children (M = 17.35) than in adults (M = 21.53). There is also evidence that the psychometric properties of the PUTS are less satisfactory in young children, which is a limitation to the current study but could also reflect further evidence of age-based differences in PMUs. Indeed, a behavioral model of PMU development provides an expanded explanation of the current findings. Central to this model is the idea that PMU-tic associations are not solidified until years after tics emerge. For instance, researchers have suggested that PMUs emerge and are maintained by not only developmental and neurological factors, but also certain environmental events such as aversive consequences that accompany tics (Capriotti et al., 2013; Himle et al., 2006; Woods et al., 2005; Himle et al, 2014). The underlying neural and somatic correlates of the urge may be present at tic onset, but children may fail to recognize these feelings or experience them as non-aversive. As tics continue to occur and increase in severity, they result in aversive consequences (e.g., pain, embarrassment) (Conelea & Woods, 2008). As a result of these consequences, affected children become more vigilant to sensations that precede tics, and as with any stimulus that signals an impending aversive event, the urges acquire an aversive valence (Woods et al., 2005). Accordingly, as children age and become more attuned to PMUs (possibly around age 10), a conditioned association between PMUs and tics develops and strengthens. Adults, who may be more attuned to this functional relationship, may be more likely to notice that as their tics extinguish and become less frequent, they feel reduced PMUs. By comparison, children who are less attuned to PMUs (i.e., those younger than 10) and have weaker PMU-tic conditioned associations would be expected to show a less clear relationship between tic reductions and PMU reductions.

It is also possible that children with PTDs may have difficulty in differentiating between “true PMUs” and other aversive internal experiences (e.g., sensory underpinnings of negative affect, non-tic somatic symptoms) due to insufficiently developed levels of interoceptive awareness and verbal naming repertoires required to (a) reliably discriminate between between tic-relevant somatosensory experiences and other affective/somatic events, and (b) reliably report on these differences. Although speculative, prior research has found child-reported PUTS sores to correlate with scores on anxiety and depression measures (Eddy & Cavanna, 2013; Rozenman et al., 2015; Steinberg et al., 2009; Woods et al., 2005), and, in the present study, PMU severity reductions in children were associated with improvements in depressive symptoms and anxiety sensitivity.

Findings from the current study have important implications for future research. To date, few alternatives to the habituation model of therapeutic change in behavior therapy for PTD have been offered, but there does appear to be a specific mechanism of action within behavior therapy for PTDs that explains this treatment’s unique ability to generate tic reductions. Analyses from various clinical trials indicate that the efficacy of behavior therapy is not the result of common therapeutic factors. Specifically, studies have shown that shown that factors such as tic disclosure (Deckersbach, Rauch, Buhlman, & Wilhelm, 2006) and treatment expectancy (Wilhelm et al., 2003) do not account for outcomes in behavior therapy for PTDs. Similarly, increased knowledge and validation gained from psychoeducation may produce limited change, but does not appear to account for the majority of clinical change in behavior therapy (Piacentini et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2012). Despite the paucity of clinical research on identified mechanisms of change in behavior therapy of PTDs, there is a relative wealth of neurocognitive research suggesting alternative processes that may be at work during behavior therapy for PTD. Consistent with this view, a study of adults receiving CBIT demonstrated a nuanced relation between changes in left inferior frontal gyrus functioning (known to subserve top-down motor control) and decreases in tic severity across treatment (Deckersbach et al., 2014). This model of increased self-control could be seen as consistent with research on executive control over tics. Laboratory data suggest there is an inverse relation between tic severity and performance on a top-down cognitive-motor control task (Baym, Corbett, Wright, & Bunge, 2008), and that active tic suppression involves heightened activity in areas involved in top-down control (e.g., the left inferior frontal gyrus [Ganos et al., 2014]). A recent review found evidence suggesting that increased control over motor output, which could occur due to repeated tic suppression during development, leads to declining tic severity as affected individuals age (Jackson, Draper, Dyke, Pepes, & Jackson, 2015). Further, one recent investigation failed to find evidence for habituation across periods of reinforced tic suppression in children (Specht et al., 2013), but the researchers later reported that tics were less likely to occur following severe PMUs that were experienced during reinforced tic suppression periods than following less severe PMUs that were experienced during “free to tic” periods (Specht et al., 2014). This may be seen as indicating that top-down inhibition, manipulated by proxy in this study via the used of reinforcement for tic suppression, led to decreased tic severity in the presence of urges. There are, however, negative findings that contradict the notion that inhibitory control is correlated with improved tic suppression, as a recent study found that improvements in tic severity during CBIT were not associated with performance on a neuropsychological measure of response inhibition (Abramovitch et al., 2017).

In addition to occasioning new directions for future mechanism-focused research, the current study has several immediate implications. These data suggest that, when discussing expectations for therapy, clinicians should indicate to patients that although PMUs may become fewer and less intense over time, treatment really involves learning helpful new ways to manage existing urges. Expectations regarding PMU reduction should be expressed with caution, particularly in child and adolescent cases. Additionally, changes in urge severity across sessions should not be considered an index of treatment progress. Instead, clinicians might consider the patient’s ability to suppress tics in the presence of PMUs. A novel approach to managing tics and PMUs in such a way has been tested using mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Reese et al., 2015), which teaches patients to respond differently to PMUs by observing and tolerating these experiences without ticcing. In a small-scale uncontrolled trial of MBSR in older adolescents and adults, researchers found that the intervention was well-tolerated and resulted in significant improvements in tic severity and impairment (Reese et al., 2015). Perhaps future research should examine such an alternate model of PMU management in PTDs, focusing less on PMU reduction and more on the functional relationship between PMUs and tics within each individual.

It should be noted that a significant limitation of this study is that the PUTS may not be the perfect instrument for studying nuanced changes in PMU severity over time. Although results of this study support the notion that the PUTS can detect changes in PMUs over time, it could be argued that research on PMU habituation may benefit from assessment on a finer temporal scale (e.g., every 15s), as has been done in laboratory-based tic suppression studies (Capriotti et al., 2014; Himle et al., 2007; Specht et al., 2013). Moreover, different tics are associated with different PMUs, and CBIT is meant to target only bothersome tics and ignore benign tics (e.g., McGuire et al., 2015). This means that certain PMUs may be affected by CBIT while others remain unchanged, which could limit reductions in the overall PUTS score despite patients feeling that their most bothersome PMUs have reduced significantly. An ideal way in which to maximize the validity of PMU assessment during treatment would be to gather a continuous measure of urge severity from those urges that are tied to targeted tics, measure several different urges simultaneously, and summarize overall PMU severity. Examination of PUTS item content also reveals that the measure could be characterized as more an inventory of different types of urges experiences, rather than a multidimensional assessment of urge frequency, intensity, and resistance to change. Future studies on therapeutic processes in behavior therapy for PTDs may benefit from using assessment measures designed to measure such important constructs, such as the Individualized Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale, which measures PMUs severity on a tic-by-tic basis (McGuire et al., 2016).

CONCLUSION

Research on behavior therapy for PTDs is burgeoning, and increasing efforts are being made to understand the processes through which these treatments work. At odds with the dominant habituation model, this study found that although adults who respond to CBIT show PMU severity reductions, children who receive CBIT do not show PMU severity reductions, and PMU severity reductions do not mediate change. These results suggest that more attention be devoted to processes of change in behavior therapy for PTDs, with specific consideration of alternative models of change.

A habituation model of behavior therapy for tic disorders was tested.

Reduction in premonitory urge severity was not demonstrated in children.

Adult responders to behavior therapy showed declines in premonitory urge severity.

Reduction in premonitory urge severity did not mediate change in treatment.

Alternative models of change in behavior therapy for tics are discussed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants R01MH070802 (Dr. Piacentini), 5R01MH069877 (Dr. Wilhelm), R01MH069874 (Dr. Scahill), and R01MH069875 (Dr. Peterson) with subcontracts to Drs. Walkup and Woods. The funding agency played no role in the study design; collection; analysis or interpretation of data; the writing of this article; or the decision to submit the article for publication. We thank Julie Collins and Joel Williams for their role in providing editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Clinical trial registration information: U.S. National Institutes of Health human subject’s trial forum (ClinicalTrials.gov; #NCT00218777, #NCT00231985)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramovitch A, Hallion LS, Reese HE, Woods DW, Peterson A, Walkup JT, … Deckersbach T. Neurocognitive predictors of treatment response to randomized treatment in adults with tic disorders. Prog Neuro-Psychoph. 2017;74:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz JS. Variants of exposure and response prevention in the treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1996;27:583–600. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Mink JW. Recent advances in Tourette syndrome research. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(3):175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Nunn RG. Habit-reversal: A method of eliminating nervous habits and tics. Behav Res Ther. 1973;11(4):619–628. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaschewski T, Woerner W, Rothenberger A. Premonitory sensory phenomena and suppressibility of tics in Tourette syndrome: Developmental aspects in children and adolescents. Develop Med Child Neurol. 2003;45(10):700–703. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Baldwin DS, Dolberg OT, Andersen DF, Stein DJ. What is the threshold for symptomatic response and remission for major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder? J Clin Psychiat. 2006;67(9):1428–1434. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baym CL, Corbett BA, Wright SB, Bunge SA. Neural correlates of tic severity and cognitive control in children with Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2008;131:165–179. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psych Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consul Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SM. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Amer Acad Child Adol Psychiat. 1997;36(4):545–553. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss J, Cohen DJ, Freedman DX. Sensory experiences of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1980;37(12):1343–1347. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780250029002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch MH, Leckman JF. Clinical course of Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(6):497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt VC, Beck C, Sajin V, Anders S, Munchau A. Convergent validity of the PUTS. Front Psychiat. 2016;7(51):1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt VC, Beck C, Sajin V, Baaske MK, Baumer T, Beste C, … Munchau A. Temporal relationship between premonitory urges and tics in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Cortex. 2016;77:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine ED, Polinsky RJ, Kartzinel R, Ebert MH. The trial use of clozapine for abnormal involuntary movements. Am J Psychiat. 1979;136:317–320. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capriotti MR, Brandt BC, Turkel JE, Lee H-J, Woods DW. Negative Reinforcement and Premonitory Urges in Youth With Tourette Syndrome: An Experimental Evaluation. Behav Modif. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0145445514531015. 0145445514531015. http://doi.org/10.1177/0145445514531015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Capriotti MR, Espil FM, Conelea CA, Woods DW. Environmental factors as potential determinants of premonitory urge severity in youth with Tourette syndrome. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2013;2(1):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Capriotti MR, Himle MB, Woods DW. Behavioral treatments for Tourette syndrome. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2014;3(4):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AJ, Leckman JF. Sensory phenomena associated with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. J Clin Psychiat. 1992;53(9):319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conelea CA, Woods DW. The influence of contextual factors on tic expression in Tourette’s syndrome: a review. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(5):487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.04.010. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CR, Blacher J. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for tic disorders. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. 2007;14:252–267. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley E, Seri S, Stern JS, Robertson MM, Cavanna AE. Premonitory urges for tics in adult patients with Tourette syndrome. Brain Dev-Jpm. 2014;36(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.12.010. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T, Chou T, Britton JC, Carlson LE. Neural correlates of behavior therapy for Tourette’s disorder. Psychiat Res-Neuroim. 2014;224(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.09.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T, Rauch S, Buhlmann U, Wilhelm S. Habit reversal versus supportive psychotherapy in Tourette’s disorder: A randomized controlled trial and predictors of treatment response. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(8):1079–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy CM, Cavanna AE. Premonitory urges in adults with complicated and uncomplicated Tourette syndrome. Behav Modif. 2013;38(2):264–275. doi: 10.1177/0145445513504432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers RA, van de Wetering BJ. A treatment model for motor tics based on a specific tension-reduction technique. J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 1994;25(3):255–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman-Weieneth JL, Doctoroff GL, Harvey EA, Goldstein LH. The Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale--Parent version (DBRS-PV) factor analytic structure and validity among young preschool children. J Atten Disord. 2009;13(1):42–55. doi: 10.1177/1087054708322991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganos C, Kahl U, Brandt V, Schunke O, Bäumer T, Thomalla G, et al. The neural correlates of tic inhibition in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2014;65:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.08.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz C, Horn S. Handbook of Tourette’s Syndrome and Related Tic and Behavioral Disorders. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2005. The treatment of tics; pp. 411–426. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, … Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psy. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth C, Debes NM, Rask CU, Lange T, Skov L. Course of Tourette syndrome and comorbidities in a large prospective clinical study. J Amer Child Adol Psychiat. 2017;56(4):304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, Bonato RR. Manual for the ECDEU Assessment Battery. Vol. 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, National Institute of Mental Health; 1970. CGI: Clinical Global Impressions Scale; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. MEDIATE [Computer software] 2014 Retreived from http://afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html.

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2014;67:451–470. doi: 10.1111/bmsp.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsel WJ, Matson JL. The assessment of depression in children: The internal structure of the child depression inventory (CDI) Behav Res Ther. 1984;22(3):289–298. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(84)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle MB, Capriotti MR, Hayes LR, Ramanujam K, Scahill L, Sukhodolsky DG, … Paicentini J. Variables associated with tic exacerbation in children with chronic tic disorders. Behav Modif. 2014;38(2):163–183. doi: 10.1177/0145445514531016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle MB, Woods DW, Conelea CA, Bauer CC, Rice KA. Investigating the effects of tic suppression on premonitory urge ratings in children and adolescents with Tourette’s syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(12):2964–2976. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle MB, Woods DW, Piacentini JC, Walkup JT. Brief Review of Habit Reversal Training for Tourette Syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):719–725. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210080101. http://doi.org/10.1177/08830738060210080101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogduin K, Verdellen C, Cath D. Exposure and Response Prevention in the Treatment of Gilles de la Tourette’s Syndrome: Four Case Studies. Clin Psychol Psychot. 1997;4(2):125–135. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199706)4:2<125::AID-CPP125>3.0.CO;2-Z. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC, Alexander JR, Woods DW. The psychosocial impact of tic disorders: Nature and intervention. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2016;28(2):347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton DC, Capriotti MR, Conelea CA, Woods DW. Sensory phenomena in Tourette syndrome: Their role in symptom formation and treatment. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2014;1(4):245–251. doi: 10.1007/s40474-014-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GM, Draper A, Dyke K, Pépés SE, Jackson SR. Inhibition, disinhibition, and the control of action in Tourette syndrome. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(11):655–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ. Premonitory urges as “attentional tics” in Tourette’s syndrome. J Am Acad Child Psy. 1994;33(6):805–808. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2002;59(10):877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurlan R, Lichter D, Hewitt D. Sensory tics in Tourette’s syndrome. Neurology. 1989;39(5):731. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak C, Dat Vuong K, Jankovic J. Premonitory sensory phenomena in Tourette’s syndrome. Mov Disord. 2003;18(12):1530–1533. doi: 10.1002/mds.10618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. Patient perception of tics and other movement disorders. Neurology. 1991;41(2 Part 1):223. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.2_part_1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, Cohen DJ. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Psy. 1989;28(4):566–573. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. http://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Walker DE, Cohen DJ. Premonitory urges in Tourette’s syndrome. Am J Psychiat. 1993;150(1):98–102. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Walker DE, Goodman WK, Pauls DL, Cohen DJ. “Just right” perceptions associated with compulsive behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. Am J Psychiat. 1994;151(5):675–680. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Zhang H, Vitale A, Lahnin F, Lynch K, Bondi C, … Peterson BS. Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: The first two decades. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1):14–19. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Shear MK, Klerman GL, Portera L, Rosenbaum JF, Goldenberg I. A Comparison of Symptom Determinants of Patient and Clinician Global Ratings in Patients with Panic Disorder and Depression. J Clin Psychopharm. 1993;13(5):327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Engel RR. The relative sensitivity of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in antipsychotic drug trials. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31(2):406–412. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, McBride N, Piacentini J, Johnco C, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Storch EA. The premonitory urge revisited: An individualized premonitory urge for tics scale. J Psychiatric Res. 2016;83:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Brennan EA, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Small BJ, Storch EA. A meta-analysis of behavior therapy for Tourette syndrome. J Psychiatric Res. 2014;50:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Scahill L, Woods DW, Villarreal R, Wilhelm S, Walkup J, Peterson AL. Bothersome Tics In Patient with Chronic Tic Disorders: Characteristics and Individualized Treatment Response to Behavior Therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2015;70:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Chang S, et al. Behavior Therapy for Children With Tourette Disorder. J Amer Med Assoc. 2010;303(19):1929–1937. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese HE, Scahill L, Peterson AL, Crowe K, Woods DW, Piacentini J, et al. The Premonitory Urge to Tic: Measurement, Characteristics, and Correlates in Older Adolescents and Adults. Behav Ther. 2014;45(2):177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese HE, Vallejo Z, Rasmussen J, Crowe K, Rosenfield E, Wilhelm S. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorder: A pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(3):293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenman R, Johnson O, Chang S, Woods D, Walkup J, Wilhelm S, Peterson A, Scahill L, Piacentini J. Relationships between Premonitory Urge and Anxiety in Youth with Chronic Tic Disorders. Children’s Health Care. 2015;44:235–248. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2014.986328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, Cicchetti D. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive scale: Reliability and validity. J Amer Child Adol Psychiatry. 1997;36(6):844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Fleisig W, Rabian B, Peterson RA. Childhood anxiety sensitivity index. J Clin Child Psychol. 2010;20(2):162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Specht MW, Nicotra CM, Kelly LM, Woods DW, Ricketts EJ, Perry-Parrish C, et al. A Comparison of Urge Intensity and the Probability of Tic Completion During Tic Freely and Tic Suppression Conditions. Behav Modif. 2014;38(2):297–318. doi: 10.1177/0145445514537059. http://doi.org/10.1177/0145445514537059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht MW, Woods DW, Nicotra CM, Kelly LM, Ricketts EJ, Conelea CA, et al. Effects of tic suppression: ability to suppress, rebound, negative reinforcement, and habituation to the premonitory urge. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.09.009. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht MW, Woods DW, Piacentini J, Scahill L, Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, … Buzella BA. Clinical characteristics of children and adolescents with a primary tic disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2011;23(1):15–31. doi: 10.1007/s10882-010-9223-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielmans GI, McFall JP. A comparative meta-analysis of the Clinical Global Impressions change in antidepressant trials. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(11):845–854. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000244554.91259.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg T, Shmuel Baruch S, Harush A, Dar R, Woods D, Piacentini J, Apter A. Tic disorders and the premonitory urge. J Neural Transm. 2009;117(2):277–284. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0353-3. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-009-0353-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Cienfuegos A, Boxer O, Bilder R. Clinical global impression of cognition in schizophrenia (CGI-CogS): Reliability and validity of a co-primary measure of cognition. Schizophr Res. 2007;106(1):59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdellen CWJ, Hoogduin CAL, Kato BS, Keijsers GPJ, Cath DC, Hoijtink HB. Habituation of Premonitory Sensations During Exposure and Response Prevention Treatment in Tourette’s Syndrome. Behav Modif. 2008;32(2):215–227. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309020. http://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507309020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdellen CWJ, Keijsers GPJ, Cath DC, Hoogduin CAL. Exposure with response prevention versus habit reversal in Tourette’s syndrome: a controlled study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42(5):501–511. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Deckersbach T, Coffey BJ, Bohne A, Peterson AL, Baer L. Habit reversal versus supportive psychotherapy for Tourette’s disorder: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1175–1177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Piacentini J, Woods DW, Deckersbach T, Sukhodolsky DG, … Scahill L. Randomized trial of behavior therapy for adults with Tourette syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2012;69(8):795–803. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Himle MB. Creating tic suppression: Comparing the effects of verbal instruction to differential reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37(3):417–420. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Hook SS, Spellman DF, Friman PC. Case study: Exposure and response prevention for an adolescent with Tourette’s syndrome and OCD. J Amer Acad Child Psy. 2000;39(7):904–907. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00020. http://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200007000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Piacentini J, Chang S, Deckersbach T, Ginsburg G, Peterson A, et al. Managing Tourette Syndrome: A Behavioral Intervention for Children and Adults Therapist Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Piacentini J, Himle MB, Chang S. Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS): initial psychometric results and examination of the premonitory urge phenomenon in youths with Tic disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(6):397–403. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200512000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaider TI, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Evaluation of the clinical global impression scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychol Med. 2003;33(4):611–622. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]