Summary

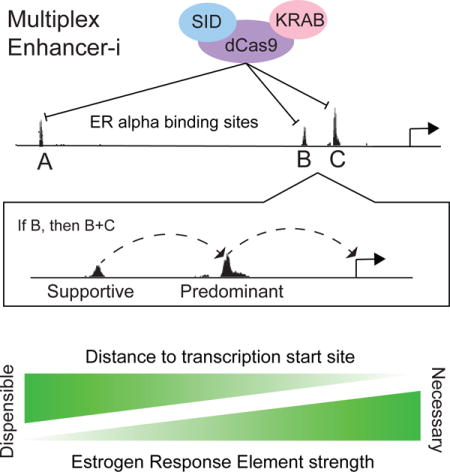

Multiple regulatory regions have the potential to regulate a single gene, yet how these elements combine to impact gene expression remains unclear. To uncover the combinatorial relationships between enhancers, we developed Enhancer-interference (Enhancer-i), a CRISPR interference-based approach that uses 2 different repressive domains, KRAB and SID, to prevent enhancer activation simultaneously at multiple regulatory regions. We applied Enhancer-i to promoter-distal estrogen receptor α binding sites (ERBS), which cluster around estradiol-responsive genes and therefore may collaborate to regulate gene expression. Targeting individual sites revealed predominant ERBS that are completely required for the transcriptional response, indicating a lack of redundancy. Simultaneous interference of different ERBS combinations identified supportive ERBS that contribute only when predominant sites are active. Using mathematical modeling, we find strong evidence for collaboration between predominant and supportive ERBS. Overall, our findings expose a complex functional hierarchy of enhancers, where multiple loci bound by the same transcription factor combine to fine tune the expression of target genes.

eTOC blurb

Carleton et al have developed a CRISPR-based technique, Enhancer-i, which enables simultaneous deactivation of multiple enhancers and allows for the functional dissection of how enhancers work together to regulate gene expression. They used Enhancer-i to identify estrogen receptor alpha bound enhancers required for the transcriptional response to estrogens and discovered that specific combinations of enhancers collaborate to produce the estrogen response.

Introduction

Transcription factors (TFs) provide spatiotemporal regulation of gene expression by binding to specific genomic regions and recruiting co-factors required for transcriptional activation or repression. Large-scale sequencing projects have now identified millions of TF-bound loci and potential enhancers within the human genome across hundreds of cell types (Andersson et al., 2014; Consortium, 2012; Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015). Both the overabundance of potential enhancers relative to genes as well as correlative studies across cell types (Andersson et al., 2014; Consortium, 2012; Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015) suggest that many genes are likely controlled by multiple TF binding events. However, the functional consequences of having multiple TF-bound loci near a given gene remain unclear, as some TF binding sites may be dispensable for gene regulation. Thus, a significant remaining challenge is to causally connect TF-bound loci to gene expression and determine their individual contributions to gene regulation.

Classical genetics approaches have provided evidence of redundant, additive, and synergistic enhancer relationships at a handful of loci (Banerji et al., 1983; Banerji et al., 1981; Bender et al., 2012; Blasquez et al., 1992; de Villiers and Schaffner, 1981; Fujioka et al., 1999; Fulton and van Ness, 1994; Guo et al., 2012; Hong et al., 2008; Kehayova et al., 2011; Lam et al., 2015; Montavon et al., 2011; Perry et al., 2010; Small et al., 1992; Stern and Frankel, 2013). For example, two enhancers regulating Pomc are both necessary in the mouse embryo, indicating a synergistic relationship, while the enhancers contribute additively to Pomc expression in adult mice (Lam et al., 2015). There are also examples of TF-bound loci working in a redundant fashion in development, termed “shadow enhancers”, which leads to robustness in regulation of important developmental genes (Cannavo et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2008; Perry et al., 2010). Unfortunately, there are few examples of functional dissection of distal regulatory region combinations due to the technical difficulty of these experiments. As a result, we have little knowledge of how multiple regulatory regions, even those bound by the same TF, combine to regulate gene expression.

To identify functional enhancers and relationships between enhancers, these elements must be studied in their native genomic context. The ability to make genetic deletions to study regulatory function has been greatly accelerated by recently developed CRISPR/Cas9 tools (Mali et al., 2013). However, it remains difficult to study multiple regulatory regions: creating combinations of deletions for multiple loci near a given gene is time-consuming with the generation of successive clones, while creating multiple deletions simultaneously may result in large genomic rearrangements and cytotoxicity. In addition, genetic deletion creates new genomic sequence at the deletion junction and may result in the accidental creation of novel regulatory elements. As an alternative to genetic deletions, a nuclease-deficient form of Cas9 (dCas9) can be fused with repressive domains that epigenetically silence target loci (Fulco et al., 2016; Gilbert et al., 2013; Kearns et al., 2015; Larson et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2013; Thakore et al., 2015). These techniques, termed CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), do not alter DNA sequence while functionally interrogating the regulatory region in situ, and can theoretically target multiple loci simultaneously. In this study, we modify the CRISPRi approach by fusing two repressive domains to dCas9 and apply the technique, termed Enhancer-interference (Enhancer-i), to the study of combinations of estrogen receptor α (ER) bound sites in endometrial cancer cells.

Estrogen signaling provides a relevant model system for studying the functional contributions of TF binding site combinations to gene regulation. ER is a ligand-dependent transcription factor and an important regulator of growth and proliferation in breast and endometrial cancers (Droog et al., 2016). While hundreds of genes change expression in response to 17β-estradiol (E2), an order of magnitude more binding events than gene expression changes are observed (Gertz et al., 2012; Gertz et al., 2013), similar to other TF inductions (Cheng et al., 2009; Reddy et al., 2009; Vockley et al., 2016). The overabundance of TF binding sites suggests that many redundant or non-functional TF binding events exist, or that the concerted activity of multiple regulatory regions is required to confer a gene expression response.

Results

ER genomic binding is clustered around estrogen responsive genes

To better understand the relationship between ER binding and gene expression, we analyzed previously published ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data for the estrogen-responsive cell lines Ishikawa (endometrial) and T-47D (breast) (Gertz et al., 2013). We first examined where ER localizes relative to estrogen responsive genes by calculating the distance between the annotated transcription start site (TSS) and the nearest ER binding site (ERBS) for genes up-, down-, or not regulated by E2 following an 8-hour treatment. We found that the majority of ERBS occur distally from their putative target promoter, with only 5.9% occurring within a 2 kb proximal promoter window, suggesting that ER tends to participate in long-range gene regulation in these cell types, as previously described in MCF-7 cells (Fullwood et al., 2009). ER binding is enriched near up-regulated genes, relative to down-regulated or not-regulated genes, up to 100 kb away from the TSS (Figure S1A–B; Wilcoxon p-value up-regulated vs. not-regulated < 2.2×10−16 for both Ishikawa and T-47D). Based on this observation, we focused on this 100 kb neighborhood for subsequent analyses.

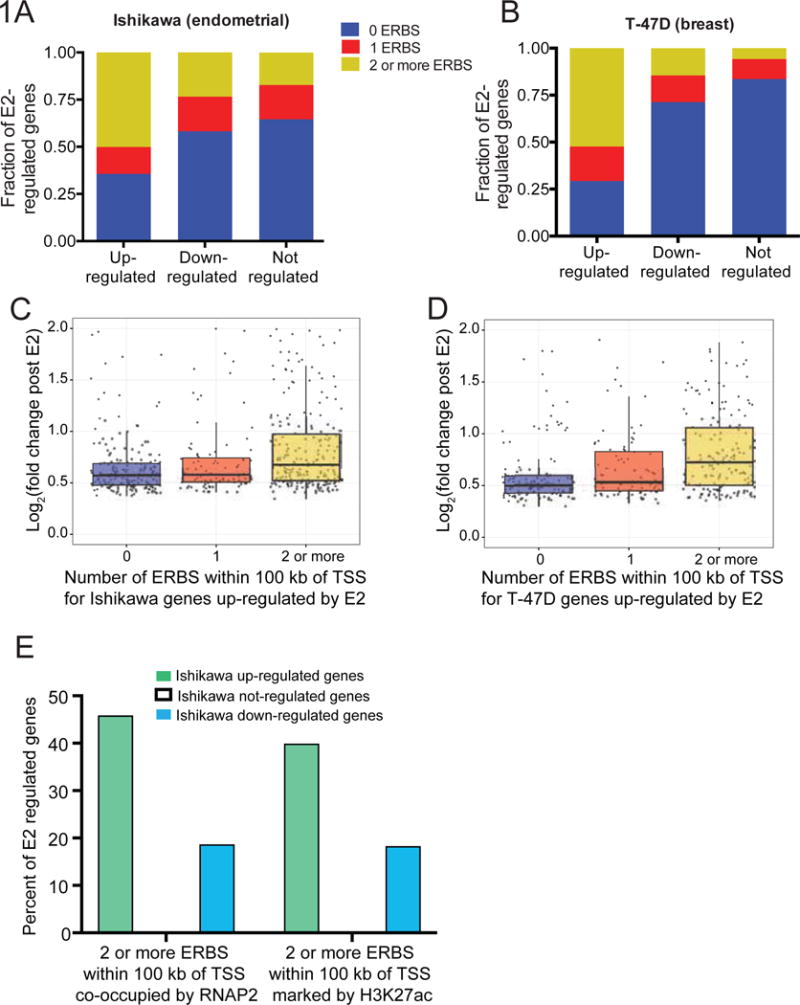

In order to determine if estrogen responsive genes show signs of combinatorial control by multiple ER-bound loci, we counted the number of ERBS within 100 kb of genes up-, down-, or not regulated by estrogen. The majority (51% and 53%) of genes up-regulated by E2 had more than one ERBS within 100 kb of the TSS in Ishikawa and T- 47D cells (Figure 1A–B, S1C–D). In contrast, most down-regulated genes (76% and 86%) and not-regulated genes (82% and 94%) had zero or one ERBS within 100 kb (Figure S1C–D). We repeated this analysis using boundaries delimited by CTCF binding sites as opposed to the 100 kb neighborhood and found similar results (Figure S1G–H). We also observed a positive correlation between the number of ERBS and gene expression fold change due to E2 for up-regulated genes in Ishikawa cells and T-47D cells (Figure 1C–D, S1I), with genes that have 2 or more ERBS nearby achieving significantly higher fold changes than genes with only 1 ERBS within 100 kb of the TSS (Wilcoxon p-value = 0.0007 and 0.0009 for 1 ERBS vs 2 or more ERBS in Ishikawa and T-47D, respectively). There was no correlation between fold change of down-regulated genes and the number of ERBS within 100 kb of the TSS (Figure S1E–F, S1J). It remains unclear why down-regulated genes have fewer ER binding sites nearby, and how ER achieves down-regulation of these genes, though a variety of potential mechanisms for repression by nuclear hormone receptors have been suggested (Santos et al., 2011). As our findings indicate that the cooperation of multiple ERBS may be required specifically for activation of gene expression in response to estrogens, we focused on up-regulated genes in this study.

Figure 1. Genes up-regulated by estrogens likely receive input from multiple ER-bound enhancers.

(A–B) The number of ER binding sites within 100 kb of the transcription start sites (TSSs) of genes up-, down-, or not regulated by estrogen following an E2 induction in Ishikawa cells (A) and T-47D cells (B) shows that up-regulated genes are enriched for multiple ER binding sites in the vicinity. See also Figure S1. (C–D) The relationship between fold change in response to E2 and the number of ER binding sites within 100 kb of the TSS for genes up-regulated by ER in Ishikawa cells (C) and T-47D cells (D) demonstrates that having more ER binding sites nearby leads to larger gene expression changes. (E) Many genes up-regulated by E2, in comparison to genes down-regulated and not regulated, have multiple ER binding sites that are co-occupied by RNAP2 (left) or marked by H3K27ac (right).

To better understand which ERBS may be active and contributing to the estrogen response in Ishikawa cells, we generated ChIP-seq data for H3K27ac, which marks active regulatory regions (Wang et al., 2008), and RNA Polymerase II (RNAP2), which localizes at active enhancers (Kim et al., 2010; Nechaev et al., 2010; Savic et al., 2015). We called 40,162 peaks for H3K27ac in the presence of estrogen and 43,578 peaks in the absence of estrogen. For RNAP2, we called 18,170 peaks following a 1-hour estrogen treatment and 35,167 in a control DMSO treatment. When we intersected these peaks with ER binding sites, we found that in total 31% of all Ishikawa-bound ERBS have RNAP2 present before or after estrogen treatment, while 72.5% of all ERBS exhibit H3K27ac in the presence or absence of E2, and 28% have both features. Using RNAP2 as a marker of activity in Ishikawa cells, we found that 46.1% of up-regulated genes have more than one active ERBS within 100 kb of the TSS, while only 18.8% of down-regulated genes have more than one active site nearby, and 13.4% of not-regulated genes show multiple active sites nearby (Figure 1E). Using H3K27ac as a marker of activity in Ishikawa cells, we found that 40.1% of up-regulated genes have more than one active ERBS nearby, while 24.3% of down-regulated genes have more than one active site nearby, and 18.5% of not-regulated genes show multiple active sites nearby (Figure 1E). Having multiple active sites nearby also resulted in significantly higher fold changes for up-regulated genes in Ishikawa cells (Wilcoxon p-value = 0.00087 for 1 RNAP2 co-occupied site vs 2 or more; Wilcoxon p-value = 4.73e-06 for 1 H3K27ac marked site vs 2 or more). These observations indicate that up-regulated genes are often associated with multiple active ERBS, further suggesting that multiple enhancers may cooperate to mediate estrogen-responsive regulation.

Recruitment of dCas9-SID fusions effectively blocks an estradiol gene expression response

In order to functionally test combinations of ERBS for their contributions to gene expression, we needed a method for interrogating the gene regulatory function of multiple TFBS simultaneously. We turned to the nuclease-deficient CRISPR/Cas9 system, which has been used to activate multiple genes using the potent viral activation domain VP64 fused to dCas9 (Cheng et al., 2013), though multiplexed deactivation using repressive fusions has been less explored. As repression mediated by dCas9-KRAB can vary from gene to gene (Gilbert et al., 2013), we decided to experiment with additional fusion proteins to determine which best inhibited the estrogen response. In addition to the original form of CRISPRi (Gilbert et al., 2013), which uses the KRAB repressive domain to recruit KAP1 and deposit heterochromatin at targeted sites (Groner et al., 2010), we also investigated the repressive capacity of the SIN3A interacting domain of MAD1, also known as the SID domain (Ayer et al., 1996). The SID domain recruits HDAC1/2, facilitating the removal of histone acetylation marks associated with activation (Alland et al., 1997). Previous studies using TALEs have shown that SIN3A can repress transcription when targeted to enhancers (Rennoll et al., 2014). While the dCas9-SID fusion has been targeted to an enhancer (Konermann et al., 2015), it has yet to be employed in blocking a transcriptional response.

To determine which repressive fusion protein is most effective at inhibiting an estrogen transcriptional response, we targeted 3 different fusions to an ERBS 5 kb upstream of G0S2, a gene that is highly induced by E2 in Ishikawa cells and has only 1 binding site nearby (Figure S2A–B). The greatest inhibition of G0S2’s estrogen response was achieved with the SID4X-dCas9-KRAB fusion (Figure S2C), suggesting that the combination of the SID and KRAB domains is most effective at blocking an estrogen transcriptional response. We made a stable line expressing the SID4X-dCas9-KRAB fusion protein, and found that we could achieve similar levels of inhibition of G0S2, with an 86.1% reduction in stable line experiments and 82.4% in transient transfections. To better understand the number of binding sites that can be targeted simultaneously with Enhancer-i, we explored the extent to which we can dilute our guide RNAs targeting the single G0S2 ERBS (see Methods). We observed significant deactivation of G0S2 with a 1:50 dilution of guide RNA (Figure S2D). We repeated these experiments on a separate ERBS and found similar results (Figure S2E). These findings suggest that we should be able to target up to 50 sites simultaneously, allowing us to quickly test multiple ERBS.

Simultaneous disruption of multiple estrogen regulated genes using Enhancer-interference

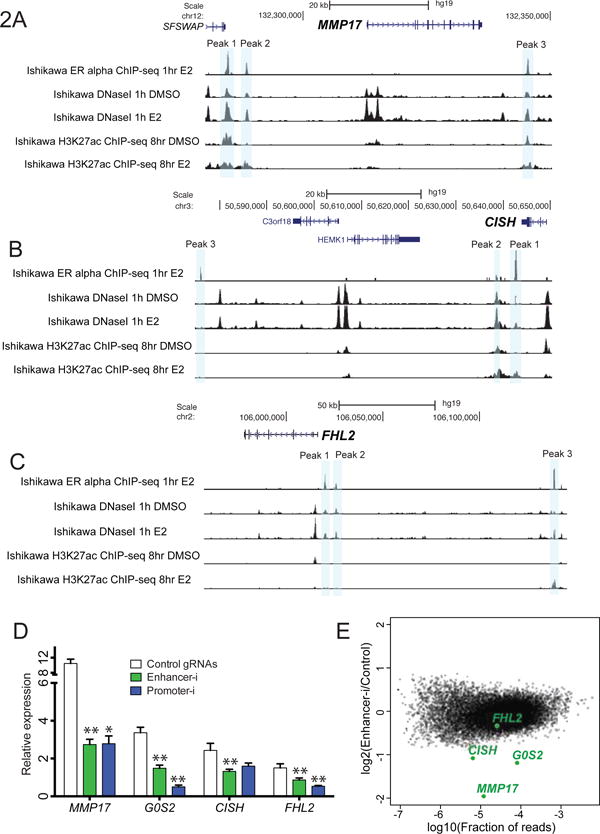

To determine if Enhancer-i can disrupt multiple ERBS simultaneously, we targeted a set of 10 ERBS that may contribute to the estrogen induction of 4 genes in Ishikawa cells, including G0S2 as mentioned above. MMP17 has 3 reproducible ERBS within 100 KB of its TSS: 2 upstream ERBS and 1 downstream ERBS (Figure 2A). CISH also has 3 ERBS within 100 kb: 3 downstream ERBS (Figure 2B). FHL2 has 3 ERBS within its genomic neighborhood that could be reproducibly identified, all of which are upstream (Figure 2C). Each ERBS has unique features as listed in Database S1, including RNAP2 occupancy, DNase I hypersensitivity, estrogen response element (ERE) strength, GC content, and evolutionary conservation. To facilitate guide RNA design for these 10 sites, we created a computational pipeline based on e-crisp’s design parameters (Heigwer et al., 2014) that incorporated findings from CRISPRi screens (Xu et al., 2015) and allowed for batch identification of guide RNAs. For each ERBS, we selected and cloned simultaneously (see Methods) 4 guide RNAs that tile across the ERBS in a 500 bp window, with the exception of G0S2, which had 6 guide RNAs to cover a wide ChIP-seq peak. To compare the performance of Enhancer-i to CRISPRi, we also created a pool of guide RNAs targeting the promoters of the putative target genes, containing 4 guide RNAs located within 500–700 bp of the transcription start site for each promoter.

Figure 2. Enhancer-i can simultaneously target multiple ER binding sites.

MMP17 (A), CISH (B), and FHL2, (C) are up-regulated by E2 in Ishikawa cells and harbor multiple ER binding sites within 100 kb of their TSS. Gray bars indicate ERBS targeted by Enhancer-i. (D) The gene expression response to E2 (white, control gRNAs, N = 8 replicates from 4 independent experiments) is significantly reduced by targeting of 10 ER binding sites (green, Enhancer-i, N = 8 replicates from 4 independent experiments), or the 4 promoters of G0S2, MMP17, CISH, and FHL2 (blue, Promoter-i, N= 4 replicates from 2 independent experiments) as measured by qPCR. (E) Enhancer-i specifically reduces the transcriptional response to E2 of targeted genes without dramatically altering the transcriptome as measured by RNA-seq. See also Figure S2. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM), double asterisks indicate p < 0.01 and single asterisks indicate p < 0.05 in a paired t-test.

The complex pool of 42 ERBS-targeting guide RNAs caused significant reduction of the E2 response for all 4 genes when transfected into the SID4X-dCas9-KRAB stable line (Figure 2D). Pooled targeting of promoters revealed a similar decrease in expression as targeting of distal ERBS (Figure 2D), indicating that Enhancer-i is highly efficient. Enhancer-i did not significantly affect the estrogen response of an un-targeted estrogen responsive gene HES2 (p = 0.2916 in paired t-test, control vs Enhancer-i), indicating that the method is specific. In the absence of estrogen, Enhancer-i led to 1.5- to 2-fold repression of basal gene expression levels, while Promoter-i was slightly more effective in reducing basal levels of MMP17, FHL2, and G0S2 (Figure S2F). Overall, the results suggest that multiplex targeting of enhancers using SID4X-dCas9-KRAB is an efficient way to disrupt multiple ERBS.

To further investigate the specificity of pooled Enhancer-i, we performed RNA-seq on cells transfected with either pooled Enhancer-i or control IL1RN-targeting guide RNAs, in the presence of estrogens. We found that the targeted genes are the most significantly down-regulated genes with the exception of FHL2, which exhibits only a modest 1.8-fold change in response to E2 and therefore should not show a large reduction due to Enhancer-i (Figure 2E). One non-targeted gene, a ribosomal subunit RPL39, was significantly impacted by Enhancer-i. However, there are no ERBS within 250 kb of the transcription start site of this gene and the closest site bound by SID4X-dCas9-KRAB in our ChIP-seq data (see below) is 70 mb away, suggesting its differential expression may be an indirect effect of targeting the 4 genes. To better understand the effects of Enhancer-i on the transcriptome, we also performed RNA-seq on Enhancer-i transfected cells in the absence of estrogens and found a slight down-regulation of CISH, G0S2, and FHL2 compared to control transfected cells (Figure S2G). Importantly, the non-targeted transcriptome was not dramatically altered by pooled Enhancer-i in the presence or absence of estrogens, emphasizing the specificity of this technique.

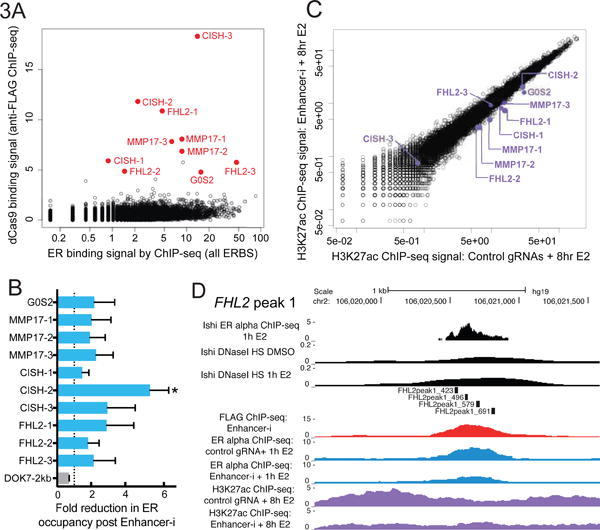

SID4X-dCas9-KRAB is specifically targeted to genomic loci and leads to reduction of ER binding

We next measured genomic binding of SID4X-dCas9-KRAB when targeted to 10 ERBS simultaneously in order to better understand the specificity and genome binding efficiency of Enhancer-i. Using an anti-FLAG antibody to pull down the epitope-tagged fusion protein, we identified 83 regions bound by SID4X-dCas9-KRAB, including each of the targeted sites. We examined the FLAG signal across all ERBS and found that the fusion binds highly specifically to each of the targeted ERBS (Figure 3A, S3–S5), with many off-target binding events at regions that also show high signal in the input control. Importantly, these off-target binding events did not appear to alter the expression of nearby genes based on RNA-seq data and may represent inefficient dCas9 binding.

Figure 3. Enhancer-i is specific to targeted sites and reduces ER occupancy as well as histone acetylation.

(A) The specificity of targeting for Enhancer-i can be seen by ChIP-seq of FLAG-tagged SID4X-dCas9-KRAB when looking at all ER binding sites, targeted sites shown in red. (B) ER occupancy is reduced by Enhancer-i at all targeted sites as shown by the fold reduction in ER occupancy quantified by comparing normalized ChIP-seq signals of ER following an E2 induction in control cells and Enhancer-i cells (2 independent replicates per condition). The un-targeted ERBS near DOK7 (gray bar) does not show a reduction in ER occupancy following Enhancer-i treatment. (C) Enhancer-i (x-axis) reduces H3K27ac at most targeted sites (purple) following E2 treatment in in comparison to control guide RNAs (y-axis). See also Figures S3–S6. (D) Example of Enhancer-i effects on ER binding (blue), H3K27ac (purple) and dCas9 binding (red), at FHL2-1, as measured by ChIP-seq. Error bars represent the SEM, double asterisks indicate p < 0.01 and single asterisks indicate p < 0.05 in a paired t-test.

To determine how Enhancer-i impacts ER binding, we performed ChIP-seq for ER on cells treated with estradiol and transfected with either ERBS-targeting guide RNAs or control IL1RN-targeting guide RNAs. We found that ER occupancy is reduced at least 2-fold at all 10 of the targeted loci (p-value range = 0.035 – 0.212), with no reduction observed at an un-targeted ERBS near the estrogen-responsive gene DOK7 (Figure 3B, S3–S5). However, the amount of reduction in ER occupancy cannot be explained by increased occupancy of the SID4X-dCas9-KRAB fusion, as some sites such as FHL2-1 that are highly occupied by the fusion also show some residual ER binding (Figure 3D). Overall, the reduction in ER binding was modest and not completely lost, suggesting that complete removal of a TF is not necessary to block its ability to regulate transcription.

Enhancer-interference reduces H3K27ac and deactivates in an HDAC-dependent manner

Both repressive domains on SID4X-dCas9-KRAB have the potential to alter the epigenetic state of target regions. To identify the epigenetic consequences of SID4X-dCas9-KRAB targeting, we performed ChIP-seq with and without Enhancer-i before and after an E2 induction. We first examined acetylation status of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac), which should be reduced by the SID domains through the recruitment of SIN3A and HDACs. We found that all of the sites targeted by Enhancer-i exhibited less H3K27ac due to Enhancer-i after an E2 induction, with the exception of CISH-3 which does not exhibit H3K27ac even in the absence of Enhancer-i (Figure 3C, S4). This decrease in H3K27ac is specifically seen at enhancers, as promoter H3K27ac for all target genes appears to be largely unaffected by Enhancer-i (Figure S6A), suggesting that loss of promoter H3K27ac is not necessary for attenuation of the estrogen transcriptional response. We also performed ChIP-seq for trimethylation at histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3), a mark that can be deposited during KRAB-mediated repression (Thakore et al., 2015). While we identified a slight increase in H3K9me3 at CISH-2 and MMP17-1 in enhancer interference conditions, the amount of signal was very low at these sites as well as other targeted ERBS and their respective promoters (Figure S6D), indicating that deposition of H3K9me is not the main mechanism by which Enhancer-i is acting. Instead, our results suggest that Enhancer-i is a specific tool that causes a reduction in H3K27ac. As observed with ER binding, H3K27ac is not completely lost with Enhancer-i (Figure 3C, S3–S5), suggesting that complete loss of H3K27ac is not necessary to prevent enhancer deactivation.

To functionally test the importance of H3K27ac reduction in Enhancer-i by SID4X-dCas9-KRAB, we applied the class II HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin A (TSA) along with Enhancer-i to attempt to rescue the estrogen response of MMP17, CISH, and G0S2. We treated cells with 3 different doses of inhibitor in the presence of ERBS-targeting guide RNAs. We found that at doses of 10 nM TSA or higher the inhibition of CISH, MMP17 and G0S2 caused by Enhancer-i was rescued, while a 1 nM dose was unable to relieve the inhibition (Figure S6B). These results indicate that enhancer deactivation by Enhancer-i is HDAC-dependent. To determine whether this HDAC dependence is unique to either the SID domain or KRAB domain, we tested the ability of TSA to prevent enhancer deactivation by dCas9-KRAB and SID4x-dCas9 in transient transfections. We found that a 100 nM dose could restore the activation of G0S2 for all fusion proteins tested (Figure S6C), indicating that histone deacetylation is an important mechanism by which inhibitory dCas9 fusions function in blocking estrogen induced transcription.

ER bound loci collaborate to regulate gene expression

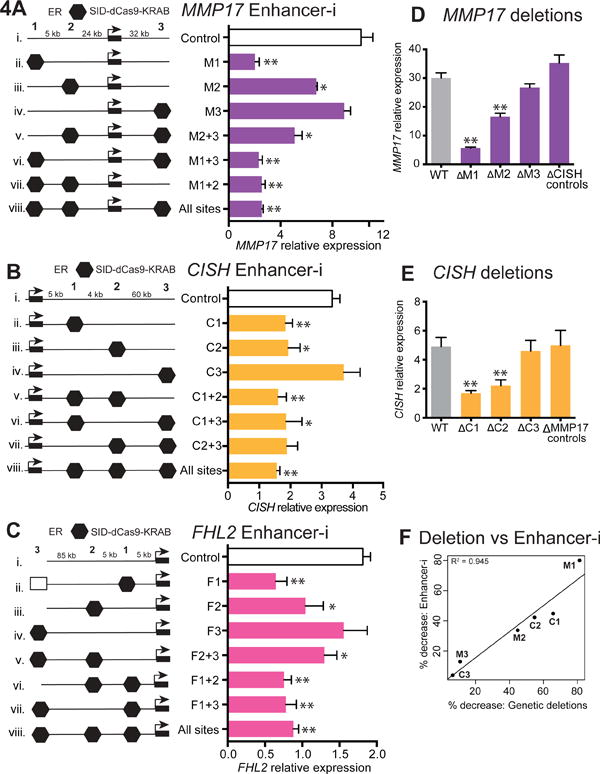

Using the pooled Enhancer-i strategy, we were able to identify sets of ERBS that participate in the estrogen-induced expression of MMP17, CISH, and FHL2. We next wanted to determine which individual sites were necessary for the estrogen response of each gene, and whether these sites were acting independently or cooperatively. We therefore used Enhancer-i to target each ERBS individually and in combinations for MMP17, CISH, and FHL2. For MMP17, we identified a predominant site, MMP17-1, whose targeting resulted in a dramatic decrease in expression both when targeted alone and in combination with other sites (Figure 4A, lanes ii, vi, and vii). We found that MMP17-2 is also necessary for the full estrogen response, though its disruption led to only a partial loss of the transcriptional response (Figure 4A, lane iii). Targeting MMP17-3 did not result in a significant decrease in expression, suggesting that this site is not necessary for the estrogen response of MMP17. To better understand the contributions of individual sites, we inhibited pairs of ERBS near MMP17, allowing only 1 site to be active at a time (Figure 4A, lanes v–vii). When MMP17-2 and MMP17-3 are targeted together and only MMP17-1 is allowed to be active, the estrogen response is still significantly reduced compared to controls (Figure 4A, lanes i and v), suggesting that the contribution of another ERBS is needed to produce MMP17’s estrogen response. One obvious candidate is MMP17-2, as its inhibition impairs the estrogen response of MMP17. Indeed, when MMP17-3 is disrupted and both MMP17-1 and MMP17-2 are active, the estrogen response of MMP17 is not significantly different from control levels (Figure 4A, lanes i and iv), suggesting a collaboration between MMP17-1 and MMP17-2. While MMP17-2 is needed for the full response, allowing only MMP17-2 to be active results in the same expression level as when all ERBS are targeted (Figure 4A, lanes vi and viii), indicating that MMP17-2 can only contribute to the estrogen response when MMP17-1 is also active. Based on this data, we consider MMP17-1 a predominant site, contributing the majority of MMP17’s estrogen response, while MMP17-2 is a supportive site, contributing conditionally.

Figure 4. Enhancer-i reveals necessary ERBS and suggests sites collaborate.

(A–C) The impact on gene expression after E2 induction of targeting individual and combinations of ERBS nearby MMP17 (A), CISH (B), and FHL2 (C), is shown with the left schematic depicting the targeted sites with black hexagons. Untargeted ERBS are indicated with empty rectangles. Bars in (A–C) represent 4 biological replicates from 2 independent experiments, except C2+3 and C1+3, which represent 3 biological replicates, from 2 independent experiments. (D–E) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genetic deletions of 3 ERBS near MMP17 (D) and CISH (E) confirm the necessity of individual sites. Bars labeled WT, ΔM1-3 and ΔC2-3 (D,E) represent 4 biological replicates from 2 individual clones (N = 8, 2 independent experiments), while ΔC1 represents 4 biological replicates from 3 individual clones (N = 12, 2 independent experiments). The bar labeled ‘ΔCISH controls’ (D) represents MMP17 expression in CISH ERBS deletions (N = 3 independent clones). The bar labeled ‘ΔMMP17 controls’ (E) represents CISH expression in MMP17 ERBS deletions (N = 3 independent clones). See also Figure S7. (F) The percent reduction in the estrogen response achieved with Enhancer-i and genetic deletions is highly correlated as shown by scatter plot. Error bars represent SEM, double asterisks indicate p < 0.01 and single asterisks indicate p < 0.05 in a paired t-test.

We found that CISH had two nearby ERBS (CISH-1 and CISH-2) that are both necessary for the full transcriptional response to E2, with individual targeting of each site producing a similar reduction in expression compared to targeting all three sites simultaneously (Figure 4B). CISH-3 targeting did not impact expression and is therefore not necessary for the estrogen response. As disruption of CISH-3 also reflects the estrogen response when CISH-1 and CISH-2 are allowed to be active (Figure 4B, lane iv), our data suggest that together these two sites can nearly produce the full estrogen response of CISH. By allowing only single sites to be active (Figure 4B, lanes vi and vii), we find that neither CISH-1 nor CISH-2 by itself can recapitulate a full estrogen response, suggesting that each site is dependent on the activity of the other for activation of CISH. For FHL2, we found a similar situation as for MMP17, where FHL2-1 is a predominant site that is completely necessary and FHL2-2 is a supportive site that can also contribute to expression, but only when FHL2-1 is active (Figure 4C). Site FHL2-3 is not necessary for the estrogen response. In summary, our Enhancer-i results from all 4 genes suggest that the estrogen transcriptional response lacks the completely redundant back-up shadow enhancers seen in development that buffer against variation, and that the response is likely coordinated by a smaller subset of sites than predicted by ChIP-seq data alone. These data provide evidence for functional collaborations between pairs of ER-bound enhancers in driving the transcriptional response to estrogens.

We used mathematical models to quantitatively investigate the evidence for ERBS collaborations in producing the estrogen transcriptional response. We tested 3 generalized linear models defined by Dukler et al (Dukler et al., 2016) that relate enhancer activity to gene expression: 1) a simple linear additive model, 2) a multiplicative linear-exponential model, and 3) a linear-logistic model (see Methods). The additive model assumes that each enhancer linearly contributes to the expression level of the gene, while the multiplicative model allows for sub-additive behavior, such that low activity enhancers do not have to directly increase gene expression. The linear-logistic model incorporates the sub-additive behavior in the linear-exponential model, but also takes into consideration the saturating nature of gene expression. To investigate whether cooperation between specific combinations of active enhancers better describe the expression of a gene than the simple additive or sub-additive relationships specified in the base models, we incorporated interaction terms for specific pairs of ERBS into the models. In this context, an interaction is defined as a statistical departure from a model that assumes independence between enhancers. We first fit each of the three models, described above, assuming independence for each gene using the Enhancer-i data. To maintain adequate power, we then incorporated one collaborative ERBS pair into each model at a time. The fits of the independent models were compared to corresponding models with interactions using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), a measure of goodness of fit that penalizes the addition of extra parameters (such as interaction terms). We found that for all 3 models and all 3 genes, the highest relative BIC, and therefore best fit, was obtained when an interaction between two ERBS was allowed (MMP17-1+2, CISH-1+2, FHL2-1+2; Figure S7A). These modeling results support the conclusion that ERBS collaborate to produce the estradiol-induced transcriptional response.

High concordance of Enhancer-i and genetic deletion confirms the necessity of predominant ERBS

Genetic deletion is currently the gold standard for determining regulatory region function and we next sought to compare Enhancer-i and genetic deletion of ERBS nearby MMP17 and CISH. We introduced Cas9 along with pairs of ERBS-flanking guide RNAs for these 6 sites into Ishikawa cells (see Methods). For MMP17 we recovered 2 homozygous deletions for each of the 3 ERBS (Figure S7B). We identified 3 homozygous deletion clones for CISH-1 and 2 clones homozygous for either CISH-2 or CISH-3 deletion (Figure S7C). Altogether, we identify a strong positive correlation in expression when comparing Enhancer-i and genetic enhancer deletions (R2 = 0.945, Figure 4D–F), confirming our Enhancer-i findings. Importantly, the deletions did not globally affect the estrogen response, as CISH still induced at wild-type levels in MMP17 deletion clones and the same could be observed for MMP17 in CISH deletion clones. These results establish Enhancer-i as an easier alternative to genetic deletion that enables multiplex regulatory region testing in situ.

Distinct features separate functional ERBS from non-functional ERBS

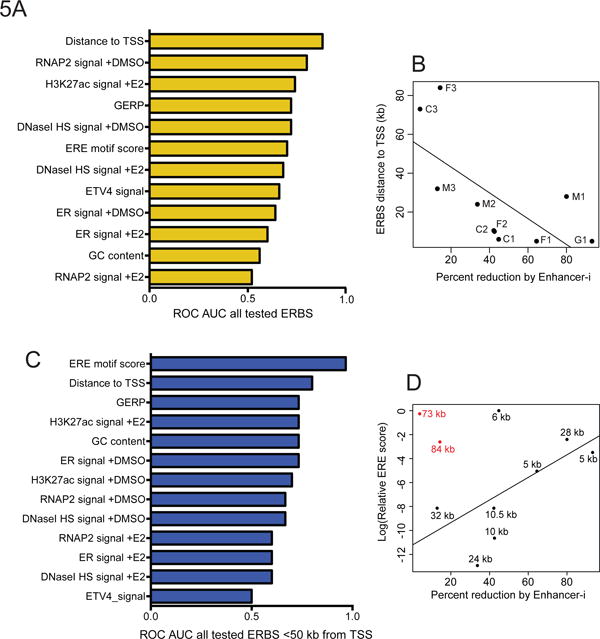

This unique dataset enabled us to explore features that distinguish necessary from non-essential ERBS. To identify features that were predictive of necessity, we first ranked ERBS by their importance in terms of percent reduction in estrogen response produced when targeted individually. We then compared each site’s importance to sequence/epigenetic features (RNAP2 ChIP-seq signal, chromatin accessibility, ERE motif strength, sequence conservation) as well as the results of our disruptions of these ERBS, such as fusion protein targeting and reduction in H3K27ac (Database S1). To identify features that best predicted the importance of ERBS in gene regulation, we performed ROC AUC analysis using a binary classification of ERBS necessity with G0S2, MMP17-1, FHL2-1, CISH-1, and CISH-2 classified as most important. Of the features altered by Enhancer-i, the most predictive attribute was H3K27ac ChIP-seq signal, both with and without Enhancer-i (Figure S8A; AUC = 1). For sequence/epigenetic features not manipulated by Enhancer-i, the most predictive feature was distance of the site from the target gene’s TSS (Figure 5A,B; AUC = 0.88). Sites that were farther away were less likely to be required for gene expression, as seen at MMP17-3, CISH-3, and FHL2-3. When we account for distance and the 2 farthest sites are removed (CISH-3: 84kb, FHL2-3: 73 kb), ERE motif score becomes highly predictive of necessity (Figure 5C,D, AUC = 0.97). More positive ERE scores, as calculated by Patser (Hertz and Stormo, 1999), indicate better matches to the full canonical palindromic ERE motif, which we term “strong” EREs, while “weak” EREs match only one half of the motif at best. Necessary sites tend to contain strong EREs, while unnecessary sites have weak EREs (Figure S8B). These results lead us to a model in which ER binding to sites with a strong ERE is more likely to induce a gene expression response; however, there are constraints on distance to the TSS of the target gene.

Figure 5. Necessary ER binding sites have distinct genomic features.

(A) Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC) values for genomic features indicate that genomic distance is the best predictor of necessity. See also Figure S8 and Database S1. (B) The relationship between necessity and distance can be seen by scatter plot. (C) ROC AUC analysis after removing 2 ERBS that are more than 70kb from the TSS of the target genes shows that ERE strength is most predictive. (D) The relationship between necessity and ERE strength is shown as a scatter plot.

To see if this model can explain genome wide patterns of estrogen-induced gene regulation, we examined the distribution of ERBS with strong EREs near up-regulated genes. We counted the number of strong EREs (full sites), called as significant by Patser (Hertz and Stormo, 1999), and weak EREs (half sites at best) within 100 kb of the TSS of genes up-regulated by estrogen that have multiple ERBS nearby. We observed significantly greater fold changes in expression for genes with 1 strong ERE ERBS nearby compared to genes with 0 strong ERE ERBS nearby (p < 0.0001 in Wilcoxon test, 1 strong EREs vs none); however, the presence of a 2nd strong ERE site nearby did not significantly add to the estrogen induction (p=0.126 in Wilcoxon test, 1 strong ERE vs multiple, Figure S8C). In contrast, the number of nearby ERBS with weak EREs is positively correlated with fold change, with significantly greater fold changes achieved when 2 or more weak ERBS are near a gene compared to just 1 (p=0.021 in Wilcoxon test, Figure S8D). Thus, while ERBS containing strong EREs may be required for induction, multiple weak sites may either help to stabilize ER’s interaction with DNA, increase the chance of recruitment of ER to that locus, or contribute to gene regulation in another manner. Our functional data shows that having weaker sites near strong sites appears to affect gene expression (e.g. MMP17-2 and FHL-2), suggesting that they might be important for supporting ERBS with strong EREs. Overall, these genome-wide observations support our model in which ERBS containing strong EREs are necessary for estrogen-induced gene expression, while ERBS with weak EREs contribute in a supportive and progressive manner.

Discussion

Our ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analyses uncovered an enrichment of ER binding in the vicinity of genes up-regulated by estrogen in breast and endometrial cancer cells. We found that up-regulated genes often have multiple ERBS in the neighborhood and that the number of ERBS is correlated with larger gene expression responses to estrogen, suggesting that multiple ERBS may be involved in the regulation of many estrogen-induced transcripts. Our correlative findings motivated the functional evaluation of combinations of ERBS to determine if and how they work together to regulate gene expression.

We adapted CRISPRi in order to enable simultaneous interruption of distal regulatory regions. The method, which we call Enhancer-i, incorporates two repressive domains: 1) The SID domain that should lead to loss of H3K27ac and enhancer deactivation, 2) A KRAB domain that can lead to heterochromatin formation. This SID4X-dCas9-KRAB fusion protein allowed us to target 10 ERBS simultaneously and block the transcriptional response to estrogens of nearby genes. We found that Enhancer-i was highly specific in both its genomic targeting and its effects on gene expression. While our data suggests that we could target up to 50 sites simultaneously and still see a reduction in the estrogen response, we may produce indirect effects on gene expression. In addition, many cells may not receive guides for all 50 sites. A recent technique addresses this issue by coupling multiplex CRISPR interference with guide RNA barcoding and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), such that each cell’s transcriptome and guide RNA content are measured simultaneously (Xie et al., 2017). While this technique may be ideal for screening putative enhancer regions near highly-expressed genes, scRNA-seq is not currently suited for the study of medium or low-expressed genes, such as most estrogen-regulated transcripts.

We investigated potential mechanisms of Enhancer-i function and found that it caused reduction in ER binding and H3K27ac at targeted sites. Interestingly, complete loss of ER binding or H3K27ac was not required for the inhibitory impact of the fusion on gene expression. Nonetheless, the reduction in H3K27ac was found to be important for Enhancer-i function, as the HDAC inhibitor TSA rescued Enhancer-i’s prevention of activation. Our findings reinforce the functional importance of H3K27ac in gene regulation, as removal can prevent gene activation and the introduction of H3K27ac by dCas9-P300 can activate gene expression (Hilton et al., 2015). Enhancer-i did not lead to substantial deposition of H3K9me3 at enhancers or promoters. We speculate that this is a result of our transient transfection of guide RNAs, as H3K9me3 was observed when guide RNAs were expressed for a week via lentiviral integration (Thakore et al., 2015). Overall, the agreement between Enhancer-i and enhancer deletion was very high (R2 = 0.945) with similar magnitude changes in gene expression, suggesting that Enhancer-i is functionally similar to complete genetic loss. Enhancer-i is thus a powerful and flexible tool for functionally characterizing regulatory regions in situ.

The flexibility of the Enhancer-i system allowed us to interrogate the functional consequences of having multiple ERBS near genes up-regulated by estradiol. By targeting sites individually at 4 different genes, we found that each gene had at least one predominant ERBS that was necessary for the bulk of the estrogen response. Therefore, none of the genes that we tested harbor complete redundancy in their transcriptional response to estrogens. This is the opposite scenario of shadow enhancers (reviewed in (Barolo, 2012)), where there are backup enhancers that play an important role in ensuring robust gene expression during development. It is possible that different evolutionary pressures have shaped the regulation of estrogen-responsive genes compared to key developmental genes. Future studies targeting more genes will be needed to determine whether this lack of redundancy we observed at 4 genes can be generalized to all estrogen-responsive genes.

We were also able to reject the model that all ERBS nearby a gene participate in the transcriptional response to estrogens, as 3 ERBS we targeted led to little or no change in the estrogen response of their putative target genes. In dissection of the murine alpha globin enhancer (Hay et al., 2016), as well as enhancers near the c-fos gene (Joo et al., 2016), similar seemingly non-functional regulatory elements were identified, suggesting that these sites may be a pervasive feature of mammalian genomes. A functional hierarchy with one dominant site was also described at the murine Wap superenhancer, though in this case all 3 STAT5 binding sites were required for the induction of Wap during pregnancy (Shin et al., 2016). Dominant repressors have also been identified in the Drosophila embryo (Perry et al., 2011). Thus, it appears a predominant regulatory region, which sits atop the functional hierarchy and is responsible for a large portion of a gene’s expression, may be a common property in mammalian gene regulation.

By interrogating ERBS alone and in combination, we dissected functional relationships between ERBS. We found that predominant sites can collaborate with other ERBS to regulate gene expression. Previous reporter assay-based studies of ERBS from MCF-7 breast cancer cells at the RET locus also suggested a cooperative relationship between ERBS when 2 EREs were placed individually and in combination in front of an SV40 promoter (Stine et al., 2011). Applying mathematical models of enhancer behavior to our Enhancer-i results provided further evidence that ERBS collaborate to regulate gene expression. The simplest example of this collaboration is at CISH, where two sites must be active to produce an estrogen transcriptional response. The simplest example of this collaboration is at CISH, where two sites must be active to produce an estrogen transcriptional response. In addition, our study reveals evidence for conditional cooperativity between enhancers at MMP17 and FHL2, wherein the contribution of a second “supportive” ERBS is dependent on the activity and contribution of the predominant ERBS. This type of epistatic interaction was initially described in reporter assays in sea urchin (Yuh and Davidson, 1996), and has been identified in autoregulation of the PU.1 locus in hematopoesis (Leddin et al., 2011). While the physical mechanism(s) underlying the observed genetic interactions between ERBS remain unclear, our data suggest that ERBS in close proximity to one another are more likely to participate in collaborative interactions.

We investigated the sequence features of predominant ERBS and found two major hallmarks: They have strong EREs and tend to be closer to their target TSS, though distance and ERE strength are not perfect predictors of ERBS importance. These findings are in agreement with our previous work showing that reporter constructs with strong EREs drive higher expression (Gertz et al., 2013) as well as a recent study from Vockley et al that found the same correlation between glucocorticoid receptor binding motif strength and reporter activity (Vockley et al., 2016). In the context of their model of glucocorticoid receptor, we propose that the direct binding targets of ER are more likely to be necessary sites in terms of gene regulation and that indirect sites clustered nearby direct binding targets can act as supportive sites, contributing to gene regulation when the direct sites are active. It remains unclear whether up-regulated genes that lack strong ERE ERBSs but have multiple proximal weak ERBS nearby would still demonstrate a functional hierarchy between these weak ERBS. Alternatively, strong distal sites (>100 kb from the TSS) may still be driving the majority of the estrogen response at these genes. Enhancer-i represents a flexible strategy for answering this and many other questions, and could be broadly applied to the dissection of enhancer function in other gene regulatory systems.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jay Gertz (jay.gertz@hci.utah.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Ishikawa cells (ECACC) were maintained in RPMI (Gibco) with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). Cells were placed in hormone-depleted RPMI for at least 6 days prior to transfection. Cells were stored at 37 C with 5% CO2 for the duration of all experiments. To validate that our derived Ishikawa cell line stably expressing SID4x-dCas9-KRAB did not greatly deviate from Ishikawa, we compared RNA-seq counts data between the derived line and the parental Ishikawa line using Spearman correlations. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were >0.96 for all comparisons between replicates (2 parental, 2 SID4x-dCas9-KRAB), indicating that our derived line is not substantially different from parental Ishikawa.

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of plasmids

To make the SID4X-dCas9-KRAB construct, we started with a dCas9-VP160 plasmid that contained a P2A linker followed by a neomycin resistance gene (Addgene 48227, a gift from Rudolf Jaenisch) (Cheng et al., 2013). To generate the dCas9 and dCas9-KRAB construct, we removed the C-terminal VP160 by digesting with AscI and ClaI and subsequently ligated in an AscI and CIaI digested gBlock containing a FLAG tag (for dCas9 only) or the KRAB domain from human zinc finger protein 10 (ZNF10) with a FLAG tag (see Table S1 for sequences). To add SID4X to the N-terminus of dCas9 and dCas9-KRAB, we digested the vectors with SgrAI and PfiMI and ligated in an SgrAI and PfiMI digested gBlock containing 4 copies of the SID domain of MAD1 (Ayer et al., 1996) that also reconstituted the promoter, HA epitope tag, and nuclear localization signal (Table S1). Plasmids were verified by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ) and the primers used are in Table S3. These constructs were maxiprepped using ZymoPURE kits (Zymo Research) prior to transfection.

To make guide RNA plasmids, we used the cloning strategy outlined by Mali et al. (Mali et al., 2013), and first moved the guide RNA cloning site from their vector (Addgene 41824, a gift from George Church) into pGL3-U6-PGK-Puro (Addgene 51133, a gift from Xingxu Huang) (Shen et al., 2014), in order to introduce puromycin resistance gene expression. The cloning site from Addgene 41824 was amplified with primers shown in Table S2, which included tails to match the donor vector. Then pGL3-U6-PGK-Puro was digested with EcoRI and NdeI and Gibson assembly was performed with the amplified product from Addgene 41824.

Guide RNA design

To identify guide RNAs for our desired target regions, we created a Perl script that allowed us to find suitable guide RNAs for multiple regions simultaneously. For a given FASTA file, this script identifies sequences that matched the pattern of 19 Ns followed by NGG (N=A,C,G or T), and then aligns these sequences to the human genome using bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) with the parameters -p 20 -k 10 -| 13 -n 0 −5 3 from e-crisp (Heigwer et al., 2014). The bowtie output is parsed and guide RNA sequences are given a score based on their number of mismatches in the seed and PAM regions. This script also takes into account findings from a recent CRISPRi screen (Xu et al., 2015) and excludes sequences with homopolymeric stretches and extreme GC content. We used a 500–700 bp window centered on the ChIP-seq peak as input sequence for each of our regions of input. We used a 500–700 bp window around the transcription start site to design guide RNAs for promoters. We selected 4–6 target sequences of 19 bp in length for each binding site and promoter, all of which had 0–2 predicted off-target sites. Guide RNA sequences with and without the PAM are listed in Table S4. Control gRNA sequences targeting the IL1RN promoter were obtained from Perez-Pinera et al (Perez-Pinera et al., 2013) and prepared similarly.

We then flanked our selected target sequences on the 5′ end with GTGGAAAGGACGAAACACCG and on the 3′ end with GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC to create 59 bp oligos. These oligos (IDT) were amplified and extended with a short 10-cycle PCR using the “U6_internal” primers shown in Table S2. To generate complex pools of guide RNAs, oligos were combined in an equimolar ratio before the PCR step. We digested the destination vector using AfIII and treated it with rSAP (New England Biolabs) to prevent re-ligation. Guide RNAs and digested plasmids were purified using the DNA clean and concentrator kit (Zymo Research) prior to Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs). To generate guide RNA pools, 2–3 independent transformations were performed and plated onto separate plates containing ampicillin. The following day, plates were scraped into a single 150 mL flask of LB, which was then incubated for 3–4 hours at 37 C with shaking prior to maxiprep.

Generation of stable cell lines

To generate stable cell lines expressing SID4X-dCas9-KRAB, Ishikawa cells were plated at a density of ~300,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate. The following day, 2.5 μg of SID4X-dCas9-KRAB plasmid was transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies). Two days later, the media was changed and G418 (Gibco) was added to the media at a final concentration of 600 μg/mL to select for transfected cells. Media changes took place every other day for approximately 3 weeks after transfection until the 6-well plate was confluent. To verify the presence of SID4X-dCas9-KRAB in these cells, we isolated RNA and performed qPCR on dCas9. We also verified integration by isolating genomic DNA from these lines, used PCR to amplify the KRAB and SID domains, and performed Sanger sequencing. Following genotyping, cells were maintained in a lower dose of G418 (300 μg/mL) to ensure continued expression of SID4X-dCas9-KRAB.

Transfection of guide RNAs into stable cell lines

To transfect guide RNAs into the Ishikawa cell line stably expressing SID4X-dCas9-KRAB, cells were grown in phenol red-free RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% Charcoal/Dextran treated fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin for 6–8 days prior to transfection. The day before transfection, approximately 60,000 cells were plated into each well of a 24-well plate in 500 μL of phenol red-free RPMI with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were transfected with FuGENE HD (Promega) per manufacturer’s protocol for unlisted cells at a 3:1 ratio of reagent:DNA with 550 ng of DNA for each well. For guide RNA dilution experiments, G0S2 and MMP17 ERBS targeting guide RNA plasmids were diluted with IL1RN-targeting guide RNA plasmids to keep the overall amount of DNA constant. Similarly, for combination experiments, the total amount of guide RNA plasmid targeting any given enhancer was kept constant and filled to 550 ng/well with IL1RN guide RNAs. Approximately 36 hours after transfection, media was changed and supplemented with 1 μg/mL puromycin and 300 μg/mL G418. Approximately 16 hours after drug treatment, an 8-hour estradiol induction was performed on select wells. Transient transfections in Ishikawa cells were performed similarly, with 300 ng of SID4X-dCas9-KRAB plasmid and 200 ng guide RNA plasmids added. A higher dose of G418 (600 μg/μL) was added to select for cells expressing the dCas9 fusion protein.

RNA isolation and qPCR

To isolate RNA from transfected cells, we performed a direct on-plate lysis of cells with 300 μL of Buffer RLT Plus (Qiagen) supplemented with 1% beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). Lysates were purified using the ZR-96-well Quick-RNA kit (Zymo Research). RNA was quantified using RiboGreen (Invitrogen) on a Wallac EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer) or on a Qubit 2.0 (Invitrogen). Gene expression was quantified using Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step Kit (Applied Biosystems) and a CFX Connect light cycler (BioRad). We used 50 ng of RNA as starting material and performed 40 cycles of PCR following a 30-minute cDNA synthesis as per kit instructions. Primers for CTCF, MMP17, CISH, G0S2, FHL2, and HES2 are listed in Table S5, along with primers to monitor expression levels of the fusion protein and guide RNAs. Experiments were performed with 2 biological replicates per condition in 24-well plates.

RNA-seq

RNA-seq was performed in duplicate for stable SID4X-dCas9-KRAB cell lines treated with either the enhancer guide RNA pool or IL1RN-targeting guide RNAs in the presence or absence of an 8-hour estradiol treatment. Poly(A)-selected libraries were generated with the KAPA Stranded mRNA-seq kit (Kapa Biosystems) using 100 ng starting material for each sample. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 as single-end 50 base-pair reads and reads were aligned to hg19 using HISAT (Kim et al., 2015). HTseq (Anders et al., 2015) was used to generate normalized counts for differential expression analysis using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). Genes with a coefficient of variation (CV) greater than 0.35 across replicates were removed from the analysis before generation of scatterplots.

ChIP-seq

To prepare chromatin for Enhancer-i ChIP-seq, Ishikawa cells expressing SID4X-dCas9-KRAB were grown in charcoal-stripped RPMI for 6–8 days. To prepare chromatin for H3K27ac ChIP-seq, Ishikawa cells were grown in full RPMI media supplemented with 1 nm E2 or grown in charcoal-stripped media for 4–6 days. To prepare chromatin for RNA polymerase II (RNAP2) ChIP-seq, Ishikawa cells were grown in charcoal-stripped RPMI for 6 days. All cells were plated at a density of 10 million cells per 15 cm dish. For Enhancer-i ChIP-seq, each dish was transfected the following day with 20 μg of guide RNA using FuGENE HD (Promega). At 36 hours post transfection, cells were treated with puromycin and G418 as described above. Approximately 16 hours later, cells were treated with 10 nM E2 or DMSO (vehicle) for either 1 hr or 8 hr prior to harvesting of chromatin. ChIP was performed as previously described (Reddy et al., 2009). The antibodies used were ER (Santa Cruz MC-20), H3K27ac (Active Motif 39133), H3K9Me3 (Abcam ab8898), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich F1804), and RNA Pol2 (Abcam ab5408). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 as single-end 50 basepair reads and aligned to hg19 using bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) with the following parameters: -m 1 -t –best -q -S -l 32 -e 80 -n 2. To call peaks we used MACS2 (Zhang et al., 2008) with a p-value cutoff of 1e-10 and the mfold parameter bounded between 5 and 50. Each ChIP was compared to an input control library derived from either the stable SID4X-dCas9-KRAB line or the parent Ishikawa cells. Bedtools merge (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) was used to determine overlap between ChIPs with 2 kb window sizes for H3K27ac, 1 kb window sizes for RNAP2, and 500 bp window size for ER. For ER, FLAG, and H3K27ac ChIPs, ChIP signal in reads per million was calculated using Bedtools coverage for all ERBS in Ishikawa using a 500 bp (ER, FLAG) or 2 kb window (H3K27ac). For H3K9me3 ChIPs, ChIP signal in reads per million was calculated for all broad peaks called by MACS2 in both Enhancer-i and control gRNA conditions.

HDAC inhibitor treatments

Ishikawa cell lines stably expressing SID4X-dCas9-KRAB were deprived of estrogens for ~7 days prior to transfection with guide RNA pools. Approximately 36 hours following transfection, media was changed and supplemented with 1 μg/mL puromycin, 300 μg/mL G418, and Trichostatin A (Cayman Chemicals) at a range of doses. Approximately 16 hours after treatment with HDAC inhibitors, an 8-hour 10 nM E2 induction was performed on select wells. Cells were harvested for RNA and quantitative real-time PCR as described above. Transient experiments in Ishikawa cells were performed similarly, with 300 ng dCas9 fusion plasmid and 200 ng guide RNA plasmid pools being transfected per well, though a higher G418 dose (600 μg/μL) was added to select for cells expressing the dCas9 fusion protein.

CRISPR/Cas9 deletions of ER-bound sites

Ishikawa cells were grown in RPMI and plated at a density of 500,000 cells per well prior to transfection in 6-well plates. Pairs of guide RNAs (indicated by an asterisk in Table S3) were co-transfected with the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro vector (Addgene 62988, a gift from Feng Zhang) (Ran et al., 2013) using FuGENE HD (Promega). Two days following transfection, media was changed and puromycin was added to the media at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL. Following 3 days of puromycin selection, cells were subject to limited dilution cloning to isolate individual colonies. For each site, 30–40 colonies were picked and genotyped using primers flanking the deletion site (Table S6). PCR products were purified using Ampure XP beads and submitted for Sanger sequencing. Homozygous and wild-type clones were grown in estrogen-deprived RPMI for ~7 days before 8-hour estradiol inductions and quantitative real-time PCR. Each clone was tested in at least 2 independent experiments with 2 biological replicates per experiment.

Mathematical modeling of ER-bound enhancer interactions

Modeling of enhancer interactions was performed using code from Dukler et al (https://github.com/CshlSiepelLab/super-enhancer-code). In their paper, 3 generalized linear models were defined for relating enhancer activity to gene expression:

- Linear – This model assumes a continuous linear relationship between enhancer activity and gene expression, representing independent, additive enhancer activity. R(x) represents the measured expression of the gene with some biological and technical noise ε, and coefficients βi represent the contribution of individual enhancers, with binary variable xi indicating whether an enhancer was targeted by Enhancer-i (0) or not (1). The generalized linear model takes on the form:

- Linear-exponential model – This model assumes a multiplicative relationship between enhancers, allowing for sub-additive relationships between enhancers at lower enhancer activity levels and super-additive relationships at higher levels. This model is simply the exponential of the linear model:

- Linear-logistic model – The final model most closely captures a free energy-based biophysical model of gene expression with two states: transcription on and transcription off. This model creates asymptotic behavior at both ends of the expression spectrum (i.e. a logistic function), allowing low-activity and high-activity enhancers to make sub- and super-additive contributions to expression up to a finite limit. Letting A(X) represent enhancer activity without noise (β0 + β1x1 + β2x2 + … + βnxn) and γ represents the maximum expression, this model takes on the form:

For each of the three enhancer behavior models (Dukler et al., 2016), we first tested error models for ε (log-normal, normal, and gamma) to determine which error model led to the lowest BIC and therefore best fit for each enhancer behavior model without interactions present. We found that the normal error model produced the lowest BICs for each of the 3 models tested, and used this error model to explore the evidence for interactions between ER binding sites at Enhancer-i targeted sites. To explore interactions between ERBS, we added a term representing the product of binary variables for the two potentially interacting sites for each gene.

For example, the linear model for CISH with the C1/C2 interaction is approximately (assuming a maximal expression of 1):

The expected output of CISH expression would be ~100% of maximal induction levels when sites 1 and 2 are allowed to be active. In the case of no interactions, the linear model is approximately:

The expected output in this situation is 20% of maximal induction levels. When we observe the data in Figure 4C, it is clear that when both C1 and C2 are not targeted by Enhancer-i, they produce greater than 20% of CISH’s estrogen response. Therefore, we expect a better fit from the model when the interaction term is present. When the models with and without interaction terms (introducing only one interaction at a time) are compared by BIC, we find that at least one interaction per gene is favored to independent models (Figure S7A). To determine whether the preference for interactions is unique to the linear model, we also tested the 2 other models of enhancer behavior (Linear-exponential and Linear-logistic) for each gene and each possible pair of interactions between ERBS. For all model forms, allowing interactions between C1/C2, M1/M2, and F1/F2 led to more favorable BIC values, providing further evidence for collaboration between these pairs of ERBS (Figure S7A). All model optimization was performed as described by Dukler et al (Dukler et al., 2016) using the DEoptim package in R.

ROC AUC analysis

The binary classifier was defined based on percent reduction in estrogen response by Enhancer-i. We used this binary classifier to evaluate the predictive ability of a variety of sequence and epigenetic information about these ERBS (Database S1). For each feature, we analyzed the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve, which varies from 1 for a perfect match and 0.5 for a random predictor, using the caTools package in R. ERE score was determined using Patser, a program that scores matches to a position weight matrix. The higher the score, the better the match to the motif. The same program was used to define matches to ETV4 motifs. In all cases, the best match within 250bp of the peak summit was used. DNaseI hypersensitivity data was obtained from ENCODE (GSM1008574). H3K27ac signal data was obtained from ChIP-seq performed in our lab for this study on Ishikawa cells (GSE99905), both in the presence and absence of Enhancer-i and estrogen. RNAP2 signal was obtained from ChIP-seq produced in our lab for this study on Ishikawa cells (GSE99905). ER signal for Ishikawa and T-47D cells was obtained from ChIP-seq data produced by ENCODE (GSM803422 and GSM803539, respectively). Custom Perl scripts were used to generate GC content and CG dinucleotide count for each ERBS.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To quantify differences in fold change in response to E2 for up-regulated genes with specific numbers of ERBS within 100 kb of their TSS, we used Wilcoxon rank sum tests. P-values from these tests can be found in the text and in the figure legend for Supplemental Figure 1. For qPCR data, paired t-tests were used to compare normalized gene expression levels in control-transfected samples to Enhancer-i or Promoter-i transfected samples. P-values and sample sizes for these tests can be found within figure legends for Figures 2 and 4, along with Supplemental Figures 2 and 4. All error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). For ER ChIP-seq quantification, a 1-sample t-test was used to compare ER occupancy in Enhancer-i conditions to control conditions. Error bars represent SEM. Sample size can be found in the figure legend.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Software: See Key Resources Table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| H3K27ac rabbit polyclonal | Active Motif | Cat# 39133; RRID:AB_2561016 |

| H3K9me3 rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | Cat# ab8898; RRID:AB_306848 |

| FLAG mouse monoclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# F1804; RRID:AB_262044 |

| RNA pol II 4H8 mouse monoclonal | Abcam | Cat# ab5408; RRID:AB_304868 |

| ER alpha rabbit polyclonal | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-544; RRID:AB_631469 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| β-estradiol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# E2758 |

| Trichostatin A | Cayman Chemicals | Cat# 89730; CAS 58880-19-6 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| ZR 96-well Quick-RNA | Zymo Research | Cat# R1053 |

| KAPA Stranded mRNA-seq | KAPA Biosystems | Cat# KK8420 |

| Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 4389986 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw and analyzed ChIP-seq data | This study | GSE99906 |

| Raw and analyzed RNA-seq data | This study | GSE99906 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human: Ishikawa cells | ECACC | ECACC Cat# 99040201, RRID:CVCL_2529 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Ishikawa SID4x-dCas9-KRAB | This study | |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| gBlocks, see Table S1 | ||

| Primers for constructing and verifying dCas9 fusions and guide RNAs, see Table S2 | ||

| Guide RNA targets, see Table S3 | ||

| qPCR primers, see Table S4 | ||

| Primers for sequencing ERBS deletions, see Table S5 | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| dCas9-VP160 | Cheng et al., 2013 | Addgene 48227 |

| pGL3-U6-PGK-Puro | Shen et al., 2014 | Addgene 51133 |

| gRNA_cloningVector | Mali et al., 2013 | Addgene 41824 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Bowtie | Langmead et al., 2009 | DOI: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 |

| MACS2 | Zhang et al., 2008 | DOI: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137 |

| DESeq2 | Love et al., 2014 | DOI: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 |

| HISAT | Kim et al., 2015 | DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.3317 |

| HTSeq | Anders et al., 2015 | DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 |

| Bedtools | Quinlan and Hall, 2010 | DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 |

| Prism 6 | http://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ | |

| Other | ||

Data produced in this study are available from GEO (GSE99906).

Additional Dataset S1 (separate Excel file)

The 10 ERBS targeted in this study are annotated with sequence/epigenetic features such as RNAP2 occupancy and conservation, as well as the results of Enhancer-i manipulation of these sites, such as the change in ER occupancy and H3K27ac marks.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Multiple ER binding sites (ERBS) cluster near genes up-regulated by estrogen

Multiplex Enhancer-i facilitates dissection of ERBS contribution to gene expression

Distance to target gene and strength of ERE motif predict ERBS necessity

Predominant sites and supportive sites collaborate to produce the estrogen response

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NHGRI R00 HG006922 and NIH/NHGRI R01 HG008974 to J.G., and the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Research reported in this publication utilized the High-Throughput Genomics Shared Resource at the University of Utah and was supported by NIH/NCI award P30 CA042014. J.B.C. was supported by NIH/NIGMS Training Program in Genetics T32 GM007464. We thank Don Ayer for reagents and advice, and we thank K-T Varley and Edward Chuong for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.C. and J.G.; Methodology, J.B.C. and J.G.; Investigation, J.B.C, K.B., and J.G.; Formal Analysis, J.B.C. and J.G.; Writing – Original Draft, J.B.C. and J.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, J.B.C. and J.G.; Funding Acquisition, J.G. and J.B.C.

References

- Alland L, Muhle R, Hou H, Jr, Potes J, Chin L, Schreiber-Agus N, DePinho RA. Role for N-CoR and histone deacetylase in Sin3-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 1997;387:49–55. doi: 10.1038/387049a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson R, Gebhard C, Miguel-Escalada I, Hoof I, Bornholdt J, Boyd M, Chen Y, Zhao X, Schmidl C, Suzuki T, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer DE, Laherty CD, Lawrence QA, Armstrong AP, Eisenman RN. Mad proteins contain a dominant transcription repression domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5772–5781. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji J, Olson L, Schaffner W. A lymphocyte-specific cellular enhancer is located downstream of the joining region in immunoglobulin heavy chain genes. Cell. 1983;33:729–740. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji J, Rusconi S, Schaffner W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell. 1981;27:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barolo S. Shadow enhancers: frequently asked questions about distributed cis-regulatory information and enhancer redundancy. Bioessays. 2012;34:135–141. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender MA, Ragoczy T, Lee J, Byron R, Telling A, Dean A, Groudine M. The hypersensitive sites of the murine beta-globin locus control region act independently to affect nuclear localization and transcriptional elongation. Blood. 2012;119:3820–3827. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-380485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasquez VC, Hale MA, Trevorrow KW, Garrard WT. Immunoglobulin kappa gene enhancers synergistically activate gene expression but independently determine chromatin structure. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23888–23893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannavo E, Khoueiry P, Garfield DA, Geeleher P, Zichner T, Gustafson EH, Ciglar L, Korbel JO, Furlong EE. Shadow Enhancers Are Pervasive Features of Developmental Regulatory Networks. Curr Biol. 2016;26:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AW, Wang H, Yang H, Shi L, Katz Y, Theunissen TW, Rangarajan S, Shivalila CS, Dadon DB, Jaenisch R. Multiplexed activation of endogenous genes by CRISPR-on, an RNA-guided transcriptional activator system. Cell Res. 2013;23:1163–1171. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Wu W, Kumar SA, Yu D, Deng W, Tripic T, King DC, Chen KB, Zhang Y, Drautz D, et al. Erythroid GATA1 function revealed by genome-wide analysis of transcription factor occupancy, histone modifications, and mRNA expression. Genome Res. 2009;19:2172–2184. doi: 10.1101/gr.098921.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, E.P. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers J, Schaffner W. A small segment of polyoma virus DNA enhances the expression of a cloned beta-globin gene over a distance of 1400 base pairs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:6251–6264. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.23.6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droog M, Mensink M, Zwart W. The Estrogen Receptor alpha-Cistrome Beyond Breast Cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2016;30:1046–1058. doi: 10.1210/me.2016-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukler N, Gulko B, Huang YF, Siepel A. Is a super-enhancer greater than the sum of its parts? Nat Genet. 2016;49:2–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M, Emi-Sarker Y, Yusibova GL, Goto T, Jaynes JB. Analysis of an even-skipped rescue transgene reveals both composite and discrete neuronal and early blastoderm enhancers, and multi-stripe positioning by gap gene repressor gradients. Development. 1999;126:2527–2538. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulco CP, Munschauer M, Anyoha R, Munson G, Grossman SR, Perez EM, Kane M, Cleary B, Lander ES, Engreitz JM. Systematic mapping of functional enhancer-promoter connections with CRISPR interference. Science. 2016;354:769–773. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullwood MJ, Liu MH, Pan YF, Liu J, Xu H, Mohamed YB, Orlov YL, Velkov S, Ho A, Mei PH, et al. An oestrogen-receptor-alpha-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature. 2009;462:58–64. doi: 10.1038/nature08497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton R, van Ness B. Selective synergy of immunoglobulin enhancer elements in B-cell development: a characteristic of kappa light chain enhancers, but not heavy chain enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4216–4223. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz J, Reddy TE, Varley KE, Garabedian MJ, Myers RM. Genistein and bisphenol A exposure cause estrogen receptor 1 to bind thousands of sites in a cell type-specific manner. Genome Res. 2012;22:2153–2162. doi: 10.1101/gr.135681.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz J, Savic D, Varley KE, Partridge EC, Safi A, Jain P, Cooper GM, Reddy TE, Crawford GE, Myers RM. Distinct properties of cell-type-specific and shared transcription factor binding sites. Mol Cell. 2013;52:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groner AC, Meylan S, Ciuffi A, Zangger N, Ambrosini G, Denervaud N, Bucher P, Trono D. KRAB-zinc finger proteins and KAP1 can mediate long-range transcriptional repression through heterochromatin spreading. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Monahan K, Wu H, Gertz J, Varley KE, Li W, Myers RM, Maniatis T, Wu Q. CTCF/cohesin-mediated DNA looping is required for protocadherin alpha promoter choice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:21081–21086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219280110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay D, Hughes JR, Babbs C, Davies JO, Graham BJ, Hanssen LL, Kassouf MT, Oudelaar AM, Sharpe JA, Suciu MC, et al. Genetic dissection of the alpha-globin super-enhancer in vivo. Nat Genet. 2016;48:895–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heigwer F, Kerr G, Boutros M. E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat Methods. 2014;11:122–123. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz GZ, Stormo GD. Identifying DNA and protein patterns with statistically significant alignments of multiple sequences. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:563–577. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.7.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton IB, D’Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, Thakore PI, Crawford GE, Reddy TE, Gersbach CA. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nbt.3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JW, Hendrix DA, Levine MS. Shadow enhancers as a source of evolutionary novelty. Science. 2008;321:1314. doi: 10.1126/science.1160631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo JY, Schaukowitch K, Farbiak L, Kilaru G, Kim TK. Stimulus-specific combinatorial functionality of neuronal c-fos enhancers. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:75–83. doi: 10.1038/nn.4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns NA, Pham H, Tabak B, Genga RM, Silverstein NJ, Garber M, Maehr R. Functional annotation of native enhancers with a Cas9-histone demethylase fusion. Nat Methods. 2015;12:401–403. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehayova P, Monahan K, Chen W, Maniatis T. Regulatory elements required for the activation and repression of the protocadherin-alpha gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17195–17200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114357108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, Harmin DA, Laptewicz M, Barbara-Haley K, Kuersten S, et al. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature. 2010;465:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature09033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, Joung J, Abudayyeh OO, Barcena C, Hsu PD, Habib N, Gootenberg JS, Nishimasu H, et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature. 2015;517:583–588. doi: 10.1038/nature14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]