SUMMARY

The motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are linked to abnormally correlated and coherent activity in the cortex and subthalamic nucleus (STN). However, in parkinsonian mice we found that cortico-STN transmission strength had diminished by 50–75% through loss of axo-dendritic and axo-spinous synapses, was incapable of long-term potentiation, and less effectively patterned STN activity. Optogenetic, chemogenetic, genetic, and pharmacological interrogation suggested that downregulation of cortico-STN transmission in PD mice was triggered by increased striato-pallidal transmission, leading to disinhibition of the STN and increased activation of STN NMDA receptors. Knockdown of STN NMDA receptors, which also suppresses proliferation of GABAergic pallido-STN inputs in PD mice, reduced loss of cortico-STN transmission and patterning, and improved motor function. Together, the data suggest that loss of dopamine triggers a maladaptive shift in the balance of synaptic excitation and inhibition in the STN, which contributes to parkinsonian activity and motor dysfunction.

Keywords: basal ganglia, cortex, globus pallidus, glutamate, NMDA, Parkinson's disease, plasticity, subthalamic nucleus, synapse

eTOC BLURB

Chu et al., report that, following loss of dopamine, activation of subthalamic nucleus (STN) NMDA receptors triggers a maladaptive reduction in cortico-STN transmission.

INTRODUCTION

The glutamatergic subthalamic nucleus (STN) is a key element of the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop, a brain circuit critical for movement control and a major site of dysfunction in psychomotor disorders such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (Albin et al., 1989). The STN is a component of two pathways that facilitate the initiation, execution and termination of appropriate actions through elevation of GABAergic basal ganglia output: the hyperdirect pathway, where cortical excitation is relayed to the output nuclei by the STN, and the indirect pathway, which traverses the striatum, external globus pallidus (GPe) and STN (Albin et al., 1989; Baunez et al., 1995; Kita and Kita, 2011; Kravitz et al., 2010; Mink and Thach, 1993; Nambu et al., 2002; Tecuapetla et al., 2016). Increased cortical driving and hyperactivity of the STN have been linked to akinesia, bradykinesia, and rigidity in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and its models (Galvan and Wichmann, 2008; Jenkinson and Brown, 2011), whereas loss or reduction of STN activity are associated with hyperkinesia and dyskinesia in hemiballism and Huntington’s disease (Albin et al., 1989; Callahan and Abercrombie, 2015; Hamada and DeLong, 1992). Excessively coherent and correlated cortico-STN activity, particularly in the β band, is also correlated with parkinsonian motor symptoms (Delaville et al., 2015; Blumenfeld and Brontë-Stewart, 2015; Sharott et al., 2014; Shimamoto et al, 2013; Zaidel et al., 2009). Theoretical studies suggest that cortico-STN transmission contributes not only to pathological STN activity but also to abnormally persistent and widespread β band activity throughout the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop in PD (Moran et al., 2011; Pavlides et al., 2015). Indeed, blockade of STN glutamate receptors reduces abnormal STN activity (Tachibana et al., 2011) and high-frequency deep brain electrical stimulation in PD has been proposed to exert its therapeutic effects by modifying cortico-STN activity and transmission (Gradinaru et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012; de Hemptinne et al., 2015; Sanders and Jaeger, 2016).

In acute lesion models of PD it takes days to weeks for parkinsonian STN activity to develop (Vila et al., 2000; Mallet al., 2008a) implying that plasticity triggered by loss of dopamine (e.g. Day et al., 2006; Fan et al., 2012; Gittis et al., 2011) contributes to its emergence. Alterations in the frequency and pattern of GPe-STN inhibition due to elevated striato-pallidal transmission may lead to disinhibited cortical patterning of the STN (Albin et al., 1989; Mallet et al., 2008b; Tachibana et al., 2011; Pavlides et al., 2015). Increased activation of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) at cortico-STN synapses could therefore promote LTP of cortical inputs (Chu et al., 2015). Indeed, STN neurons exhibit an increase in the ratio of AMPA receptor (AMPAR) to NMDAR current (Shen and Johnson, 2005) and GPe-STN synapses proliferate through NMDAR-dependent heterosynaptic plasticity in PD rodents (Chu et al., 2015). However, in parkinsonian monkeys a decrease in the number of cortico-STN inputs has been reported (Mathai et al., 2015). Together, these data suggest that cortico-STN transmission may be mediated by fewer but potentially more powerful inputs following loss of dopamine.

The balance of synaptic excitation and inhibition in neuronal networks is critical to their performance and is controlled by long-term and/or homeostatic plasticity (Malenka and Nicoll, 1999; Turrigiano et al., 2011). These plasticities optimize information processing and storage under normal conditions but in disease states can produce maladaptive changes, which compromise both network performance and behavior. We therefore tested 3 hypotheses using the chronic, unilateral, 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-lesion mouse model of mid-late stage PD: 1) the properties of cortico-STN synaptic inputs are modified following loss of dopamine 2) cortico-STN synaptic plasticity is triggered by elevated striato-pallidal transmission, leading to disinhibition of the STN, and increased activation of STN NMDARs 3) an abnormal balance of cortico-STN excitation relative to GPe-STN inhibition impairs motor function.

RESULTS

Data are reported as median and interquartile range. Box plots illustrate the median (central line), interquartile range (box) and 10–90% range (whiskers) of the data. Unpaired and paired non-parametric statistical comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test, respectively. The Holm-Bonferroni method was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

The strength of cortico-STN transmission decreases following chronic loss of dopamine

The physiological properties of motor cortico-STN transmission were compared in brain slices from 6-OHDA-injected, dopamine-depleted and vehicle-injected dopamine-intact mice using optogenetic stimulation and patch clamp recording. Cortico-STN excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were evoked at -80 mV to isolate AMPAR-mediated transmission (Chu et al., 2015). The amplitude of cortico-STN transmission was diminished across a range of stimulation intensities in slices from dopamine-depleted relative to control mice (e.g. EPSC amplitude at 2.6 mW/mm2: vehicle = 488, 405–552 pA, n = 18 neurons, 3 mice; 6-OHDA = 129, 103–242 pA, n = 16 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 1A–D). The ratio of EPSC2 (stimulated 100 ms after EPSC1) to EPSC1 was similar in slices from dopamine-depleted versus -intact mice (e.g. EPSC2:EPSC1 at 2.6 mW/mm2: vehicle = 0.81, 0.61–0.86, n = 18 neurons, 3 mice; 6-OHDA = 0.75, 0.54–1.07, n = 16 neurons, 3 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 1E–F) arguing that a lower initial probability of transmission was not responsible for reduced cortico-STN transmission. Asynchronous cortico-STN transmission, optogenetically evoked in the presence of Sr2+, was compared in slices from dopamine-depleted versus -intact mice. Both the frequency (vehicle = 14.9, 7.8–24.9 Hz, n = 24 neurons, 4 mice; 6-OHDA = 5.9, 3.8–10.6 Hz, n = 19 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 1G, H) and amplitude (vehicle = 12.6, 10.8–19.6 pA, n = 24 neurons, 4 mice; 6-OHDA = 10.8, 9.7–12.0 pA, n = 19 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 1G, I) of asynchronous transmission were reduced following dopamine depletion. Together, these data suggest that following the loss of dopamine the strength of AMPAR-mediated cortico-STN transmission decreases, largely through a reduction in the number of functional inputs.

Figure 1. The strength of cortico-STN transmission decreased following loss of dopamine.

(A, B) Viral expression of ChR2(H134R)-eYFP (green) in infected cortical neurons at the site of injection in primary motor cortex (M1; A) and at the site of their axon terminal fields in the STN (B). Cortical (A) and STN (B) neurons were immunohistochemically labeled for neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN; red). (C, D) The amplitude of cortico-STN transmission was lower across a range of optogenetic stimulation intensities in 6-OHDA-injected, dopamine-depleted mice relative to vehicle-injected, dopamine-intact mice (C, representative examples; D, population data). (E, F) The amplitude of optogenetically stimulated cortico-STN EPSC2 relative to EPSC1 was similar in 6-OHDA- and vehicle-injected mice across a range of stimulation intensities (E, representative examples; F, population data). (G–I) The frequency (G, H) and amplitude (G, I) of asynchronous cortico-STN transmission optogenetically evoked in the presence of Sr2+ was reduced in 6-OHDA- relative to vehicle-injected mice (G, representative examples; H, I, population data). Blue arrow, optogenetic stimulation; *, p < 0.05.

The number of cortico-STN inputs decreases following loss of dopamine

To determine the impact of dopamine depletion on cortico-STN innervation, immersion-fixed brain slices from 6-OHDA and vehicle-injected mice were processed for the immunohistochemical detection of vesicular glutamate transporter type 1 (vGluT1), a predominantly cortical axon terminal marker that is not expressed by subcortical afferents of the STN (Barroso-Chinea et al., 2008; Wang and Morales, 2009). The densities of vGluT1-immunoreactive puncta in the STN were then determined stereologically (West, 1999). Consistent with non-human primate data (Mathai et al., 2015), the density of vGluT1-immunoreactive puncta was lower in slices from dopamine-depleted versus -intact mice (vehicle = 19.2, 15.1–23.7 million/mm3, n = 31 samples, 8 mice; 6-OHDA = 13.2, 8.8–14.7 million/mm3; n = 30 samples, 8 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 2A–C). No alteration in the area of the STN was observed (vehicle = 0.24, 0.20–0.28 mm2, n = 14 slices, 8 mice; 6-OHDA = 0.20, 0.17–0.24 mm2; n = 14 slices, 8 mice; p > 0.05).

Figure 2. Cortico-STN axon terminals and their post-synaptic targets were eliminated following loss of dopamine.

(A-C). The density of vGluT1-immunoreactive cortico-STN axon terminals (red puncta) was lower in 6-OHDA-injected mice compared to vehicle controls (A, B, representative confocal micrographs; C, population data). (D–K) The dendritic morphology of Golgi-impregnated STN neurons was altered in 6-OHDA-treated mice compared to vehicle controls. (D–G) Representative Golgi-impregnated neurons, illustrating loss of dendrites (D–F) and dendritic spines (G; red arrowheads) in 6-OHDA-treated mice. (F) Sholl plots of the neurons in D and E. Concentric shells, which increase in diameter in 10 μm increments, are centered on the soma of each representative neuron. (H) Population data. The number of dendritic intersections at distances greater than 30 μm from the soma was lower in neurons from 6-OHDA-treated mice relative to neurons from vehicle- treated mice. (I–K) Population data for dendritic length (I) and dendritic spines (J, K) in Golgi-impregnated neurons from dopamine-depleted and -intact mice. *, p < 0.05.

Cortico-STN axon terminals synapse with distal dendrites and to a lesser degree dendritic spines (Bevan et al., 1995). To determine whether dopamine-depletion produced corresponding postsynaptic alterations, the morphologies of Golgi-impregnated STN neurons in tissue from perfuse-fixed 6-OHDA- and vehicle-injected mice were compared (Figure 2D–K). Three-dimensional, morphometric analysis confirmed several alterations in dopamine-depleted mice 1) there were fewer dendritic branches at distances greater than 30 μm from the soma (e.g. dendrites intersecting a 50 μm diameter sphere centered on the soma: vehicle = 5, 4–6; n = 26 neurons, 3 mice; 6-OHDA = 3, 2–4; n = 26 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 2D, E, F, H) 2) the total dendritic length was shorter (vehicle = 421, 307–558 μm; n = 26 neurons, 3 mice; 6-OHDA = 294, 261–375 μm; n = 26 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 2D, E, F, I) 3) there were fewer dendritic spines (vehicle = 21, 5–31; n = 26 neurons, 3 mice; 6-OHDA = 8, 5–16; n = 26 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 2G, J, K). Together these data demonstrate that both cortico-STN axon terminals and their postsynaptic targets were eliminated following loss of dopamine.

The physiological properties of cortico-STN transmission are altered following loss of dopamine

Plasticity and pathological processes can modulate the strength and nature of glutamatergic transmission through changes in GluA2 AMPAR subunit expression (Isaac et al., 2007; Jonas et al., 1994; Liu and Savtchouk, 2011). The pharmacological and biophysical properties of cortico-STN synapses were therefore assessed. Cortico-STN EPSCs optogenetically evoked at −80 mV were relatively sensitive to the Ca2+-permeable AMPAR antagonist 1-Naphthyl acetyl spermine trihydrochloride (Naspm; 100 μM) in slices from 6-OHDA-injected mice (Naspm inhibition: vehicle = 38.7, 24.5–42.5%; n = 8 neurons, 3 mice; 6-OHDA = 57.4, 53.3–60.8%; n = 7 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 3A, B), implying a reduction in GluA2 expression. Consistent with reduced GluA2 expression, AMPAR-mediated cortico-STN transmission in the presence of the NMDAR antagonist D-APV (50 μM) was faster (τdecay: vehicle = 6.8, 4.6–7.8 ms; n = 18 neurons, 3 mice; 6-OHDA = 4.0, 3.3–5.0 ms; n = 16 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 3C–D) and inward rectification was stronger in 6-OHDA-treated mice (EPSC amplitude at −80 mV/+40 mV: vehicle = 3.1, 2.6–4.4; n = 30 neurons, 7 mice; 6-OHDA = 4.9, 3.9–6.3; n = 31 neurons, 6 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 3C, E). Together these data suggest that following loss of dopamine cortico-STN AMPAR-mediated transmission undergoes associated molecular and biophysical alterations. No change in AMPAR:NMDAR ratio was observed (Figure S1).

Figure 3. The post-synaptic receptor and long-term plasticity properties of cortico-STN transmission were modified following loss of dopamine.

(A, B) The sensitivity of optogenetically stimulated cortico-STN transmission evoked at −80 mV to the Ca2+ permeable (GluA2-deficient) AMPAR antagonist Naspm is greater in 6-OHDA- relative to vehicle-treated mice (A, representative examples, B, population data). (C–E) Optogenetically stimulated and pharmacologically isolated AMPAR-mediated cortico-STN EPSCs exhibited relatively rapid decay kinetics (C, D) and rectification (C, E) at depolarized voltages in 6-OHDA-injected mice (C, representative examples; D, E, population data). (F–H) Application of an optogenetic stimulation protocol (1 ms light pulses delivered at 50 Hz for 300 ms, repeated 30 times at 0.2 Hz), which induced LTP of cortico-STN transmission in vehicle-treated mice (F), failed to induce LTP in 6-OHDA-treated mice (G). Furthermore, application of 0.5–1.0 μM dopamine failed to rescue LTP in 6-OHDA-treated mice (H). (F–H) Left panel, normalized transmission before and following the induction protocol; right panel, representative cortico-STN EPSCs at time points 1 and 2, prior to and following the induction protocol, respectively. Blue arrow, optogenetic stimulation; *, p < 0.05. See also Figure S1.

Repeated optogenetic driving of cortico-STN transmission in dopamine-intact mouse brain slices can lead to NMDAR-dependent LTP, most likely through insertion of postsynaptic AMPAR subunits (Chu et al., 2015). Loss of dopamine prevents/alters the induction of synaptic plasticity in the striatum (Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011). To determine whether dopamine depletion affects LTP in the STN, cortico-STN EPSCs were compared 5 minutes before and 35–40 minutes after an optogenetic stimulation protocol shown to induce LTP (1 ms light pulses delivered at 50 Hz for 300 ms, with stimulus trains repeated 30 times at 0.2 Hz; Chu et al., 2015). LTP was induced in slices from dopamine-intact (median EPSC amplitude post-induction relative to pre-induction: vehicle = 134.5, 108.3–151.5%; n = 7 neurons, 5 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 3F) but not -depleted mice (6-OHDA = 79.7, 54.9–90.5%; n = 10 neurons, 5 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 3G). LTP was not rescued by application of 0.5–1.0 μM dopamine (99.7, 82.2–102.8%; n = 8 neurons, 4 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 3H). Thus, the capacity for LTP of cortico-STN transmission is impaired in PD mice.

Cortico-STN patterning is diminished following loss of dopamine

To determine the impact of dopamine depletion on cortico-STN β band patterning, the effects of optogenetic stimulation (15 Hz in 1 ms pulses for 1 second at an intensity of 1.0 mW/mm2) of cortico-STN axon terminals on STN activity were compared in slices from 6-OHDA- and vehicle-injected mice. β band stimulation of each STN neuron was repeated 3 times at a frequency of 0.033Hz. STN neurons were recorded in the loose-seal, cell-attached configuration to minimize perturbation of their firing. The number of cortically generated action potentials (synaptic drive) was defined using peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) as those exceeding the mean plus 3 standard deviations of action potential counts in the 2 seconds preceding stimulation. The spontaneous firing of STN neurons (Atherton et al., 2008) decreased in frequency (vehicle = 11.6, 8.2–13.9 Hz; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; 6-OHDA = 2.7, 0–8.5 Hz; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 4A–E) and regularity (CV: vehicle = 0.12, 0.10–0.18; n = 16 neurons, 4 mice; 6-OHDA = 0.43, 0.16–0.58; n = 10 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 4A–E) following loss of dopamine, consistent with previous observations (Wilson et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2002). In neurons from 6-OHDA-injected mice 1) the number of cortically generated action potentials was lower (synaptic drive: vehicle = 31, 20–41; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; 6-OHDA = 15, 9–23; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 4A–D, F) 2) the latencies and interquartile ranges of latencies of cortically stimulated action potentials were increased (latency: vehicle = 3.7, 2.5–6.3 ms; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; 6-OHDA, 18.2, 11.6–31.6 ms; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 4A, B, F) (interquartile range of latency: vehicle = 0.9, 0.5–3.5 ms; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; 6-OHDA, 13.0, 8.4–24.9 ms; n = 17 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 4A, B, F). The reduced effectiveness of cortico-STN patterning in terms of the number, latency and temporal precision of synaptically generated action potentials is consistent with the reduction in cortico-STN transmission strength following loss of dopamine.

Figure 4. The strength of cortico-STN patterning decreased following loss of dopamine.

(A–F) Cortico-STN inputs optogenetically stimulated (blue) at 15 Hz less effectively patterned STN neuronal activity in ex vivo brain slices derived from 6-OHDA-injected mice versus vehicle-injected mice. (A, B) Representative examples and (C, D) population peristimulus time histograms derived from vehicle- (A, C) and 6-OHDA-injected (B, D) mice. Cyan dashed line, mean of action potentials preceding optogenetic stimulation. Red dashed line, mean plus 3 standard deviations of action potentials preceding optogenetic stimulation. Blue rectangle, period of optogenetic stimulation. (E) The frequency and regularity (CV) of spontaneous firing were reduced in 6-OHDA-injected mice relative to vehicle-injected controls. (F) The number of cortically driven action potentials (synaptic drive) was lower and the latency of action potentials following each optogenetic stimulus greater in 6-OHDA mice relative to vehicle-injected controls. (G–J) Application of the AMPAR antagonist GYKI 53655 but not the NMDAR antagonist D-APV reduced the effectiveness of optogenetically stimulated cortico-STN patterning both in terms of the number (G-I) and latency (J) of synaptically generated action potentials in both vehicle- (G, I, J) and 6-OHDA-injected mice (H–J) (G, H, representative examples; I, J, population data). *, p < 0.05. ns, not significant.

To determine the relative contribution of AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated transmission to cortico-STN patterning, a subset of neurons was sequentially administered the NMDAR antagonist D-APV (50 μM) alone and then together with the AMPAR antagonist GYKI 53655 (50 μM). In STN neurons from both vehicle- and 6-OHDA-injected mice only AMPAR antagonism reduced and delayed cortical generation of action potentials (synaptic drive: vehicle, control = 34, 30–44; vehicle, D-APV = 35, 21–44; n = 7 neurons, 4 mice; p > 0.05; vehicle, GYKI 53655 = 2, 0–8; n = 7 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; 6-OHDA, control = 21, 15–44; 6-OHDA, D-APV = 24, 14–38; n = 8 neurons, 4 mice; p > 0.05; 6-OHDA, GYKI 53655 = 0, 0–3; n = 8 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 4G–I) (latency: vehicle, control = 3.5, 2.5–4.4 ms; vehicle, D-APV = 3.4, 2.8–4.2 ms; n = 7 neurons, 4 mice; p > 0.05; vehicle, GYKI 53655 = 31.9, 20.5–35.6 ms; n = 7 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; 6-OHDA, control = 11.6, 9.1–17.0 ms; 6-OHDA, D-APV = 12.3, 6.1–18.0; n = 8 neurons, 4 mice; p > 0.05; 6-OHDA, GYKI 53655 = 31.6, 30.2–33.7 ms; n = 6 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 4G, H, J) consistent with the relatively large magnitude of AMPAR- versus NMDAR-mediated EPSCs at subthreshold voltages (Chu et al., 2015). Together these data confirm that cortico-STN patterning is greatly diminished following chronic loss of dopamine and that AMPAR-mediated transmission largely mediates cortico-STN patterning in both dopamine-depleted and -intact mice.

Chronic chemogenetic elevation of striato-pallidal transmission in vivo leads to a reduction in cortico-STN transmission

Following loss of dopamine, elevated D2-striatal projection neuron (D2-SPN) transmission to the GPe leads to disinhibition and altered patterning of the STN (Kita and Kita, 2011; Mallet et al., 2006, 2008b). To determine whether elevated D2-SPN-GPe transmission is sufficient for cortico-STN input loss, dopamine-intact, transgenic adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mice (Figure 5A–C) were administered clozapine-N-oxide (CNO; 1 mg/kg) or vehicle subcutaneously approximately every 12 hours over 2–3 days to chemogenetically activate rM3Ds-mCherry in D2-SPNs (Farrell et al., 2013) and control for injection, respectively. Mice were placed in an open field chamber and locomotor activity was monitored for 5 min, 45 minutes before and 30 mins after injection. Data from the first 2 mins of activity were analyzed separately to minimize the contribution of exploration due to a novel environment (see Figure S2; c.f. Lemos et al., 2016). Consistent with an increase in D2-SPN-GPe transmission chemogenetic activation of rM3Ds in vivo 1) reduced the distance traveled in the open field during minutes 3–5 (e.g. distance traveled day 2: vehicle = 3.94, 1.75–7.76 m; n = 6 mice; CNO = 0.036, 0.02–0.06 m; n = 6 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 5D–F) 2) reduced firing of GPe neurons recorded under urethane anesthesia during cortical slow-wave activity (mean frequency of GPe activity: 20 minutes pre-CNO = 19.4, 13.7–27.3 Hz; > 30 minutes post-CNO = 14.8, 7.7–24.0 Hz; n = 28 neurons, 4 mice; p <0.05; Figure 5G, H). Furthermore, chem3ogenetic activation of rM3Ds ex vivo (10 μM CNO) elevated the frequency but not the amplitude of GABAA receptor-mediated miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) recorded in GPe neurons in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin (frequency: control = 10.3, 9.2–13.1 Hz; n = 6 neurons, 2 mice; CNO = 20.4, 14.1–24.5 Hz; n = 7 neurons, 2 mice; p < 0.05; amplitude: control = 35.2, 32.0–41.5 pA; n = 6 neurons, 2 mice; CNO = 34.1, 27.0–37.3 pA; n = 7 neurons, 2 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 5I–K). However, chemogenetic activation of rM3Ds ex vivo did not increase the excitability of D2-SPNs (Figure S2), arguing that an increase in the probability of D2-SPN transmission is sufficient for akinesia (c.f. Lemos et al., 2016). Chemogenetic activation of D2-SPN rM3Ds for 2–3 days in vivo led to a reduction in the density of vGluT1-immunoreactive cortico-STN axon terminals (vehicle = 38.6, 30.7–46.9 million/mm3; n = 35 samples, 3 mice; CNO = 22.4, 19.6–27.2 million/mm3; n = 35 samples, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 5L–N) and to a reduction in the strength of optogenetically stimulated cortico-STN transmission (e.g. amplitude at 2.6 mW/mm2: vehicle = 528.8, 509.3–813.2 pA, n = 17 neurons, 2 mice; CNO = 163.8, 105.3–236.5 pA; n = 24 neurons, 2 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 5O–P) relative to vehicle-injected mice. Together, these data argue that elevated D2-SPN-GPe transmission is sufficient to trigger downregulation of cortico-STN transmission in dopamine-intact mice.

Figure 5. The strength of cortico-STN transmission decreased following chemogenetic activation of D2-SPNs in dopamine-intact mice.

(A, B) Expression of rM3Ds-mCherry in D2-SPNs (A, red arrows) and their axon terminal fields in the GPe (B) in the adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mouse. Expression was absent in putative D1-SPNs (A; white arrows) and their axon terminal fields in the SNr (C). (B, C) Expression was also absent in GPe (B; white arrows) and SNr (C; white arrows) neurons. Immunohistochemistry for NeuN (white) was used as a neuronal marker in A–C. (D–F) Chemogenetic activation of rM3Ds in D2-SPNs through subcutaneous (SC) injection of CNO (1 mg/kg) led to inhibition of open field motor activity relative to vehicle injection. (D) Representative examples of open field activity before and after first injection. (E, F) Population data confirming that CNO injection reduced movement traveled in the open field (E, left and right box plots for vehicle and CNO represent movement prior to and following first injection, respectively; F, movement following injection of vehicle or CNO over 3 consecutive days). (G) Simultaneous recordings of the electroencephalogram (EEG) band pass filtered at 0.5–1.5 Hz and 10–100 Hz, and GPe unit activity in a urethane-anesthetized adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mouse prior to (control), and 30–45 mins following the SC administration of CNO (1 mg/kg). The rate of GPe unit activity during periods of robust cortical slow-wave activity decreased following the injection of CNO both in each example neuron (G) and across the population sample (H). (I–K) the frequency (I, J) (but not the amplitude; I, K) of mIPSCs in GPe neurons was greater in brain slices treated with CNO (10 μM) ex vivo versus untreated control slices (I, representative examples; J, K, population data). (L–P) Subcutaneous injection of CNO every 12 hours for 2–3 days led to a reduction in the density of vGluT1 expressing cortico-STN axon terminals (L–N) and to a reduction in the amplitude of optogenetically stimulated (blue arrow) cortico-STN transmission (O, P) relative to vehicle-injected control mice (L, M, representative micrographs; N, population data; O, representative traces; P, population data). Blue arrow, optogenetic stimulation; *, p < 0.05. ns, not significant. See also Figure S2.

Excessive activation of STN NMDARs triggers downregulation of cortico-STN transmission following loss of dopamine

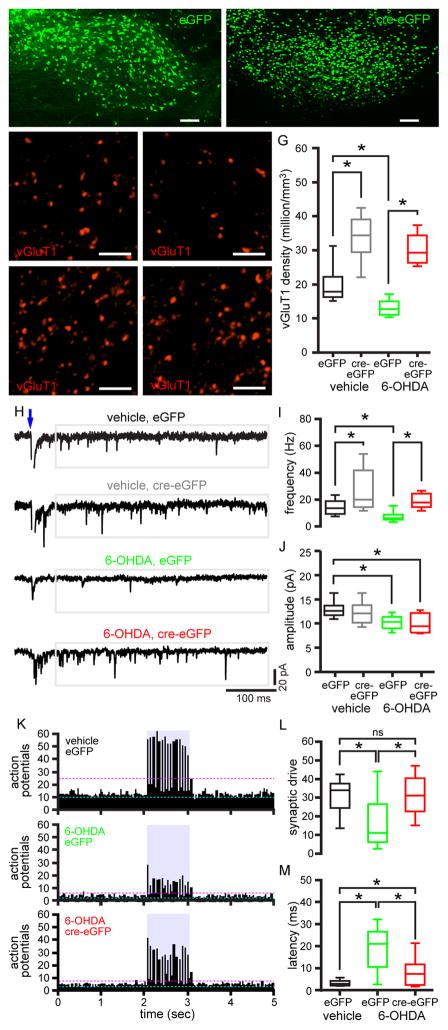

The experiments described above suggest that elevated inhibition of the GPe by D2-SPNs is sufficient for downregulation of cortico-STN transmission. In 6-OHDA-injected rodents, which exhibit similarly elevated D2-SPN-GPe transmission and STN disinhibition (Mallet et al., 2006, 2008b), increased activation of STN NMDARs triggers proliferation of GPe-STN synapses (Fan et al., 2012; Chu et al., 2015). To determine whether STN NMDARs regulate the number of cortico-STN synapses, AAV vectors expressing eGFP (Figure 6A) or cre recombinase (cre)-eGFP (Figure 6B) were injected into the STN of Grin1lox/lox transgenic mice (Tsien et al., 1996) to control for AAV injection and to knockdown STN NMDARs, respectively, as described previously (Chu et al., 2015). 6-OHDA or vehicle was also injected into the medial forebrain bundle in the same surgery. Knockdown of STN NMDARs with this approach has been validated recently (Chu et al., 2015). Several weeks later brain slices from these mice were prepared, immersion fixed, and processed for vGluT1 immunohistochemistry. In eGFP expressing, NMDAR-intact mice dopamine depletion led to a decrease in vGluT1 expressing cortico-STN axon terminal density relative to vehicle-injected control mice, consistent with the above data (vGluT1 density: vehicle, eGFP = 17.9, 16.3–22.3 million/mm3; n = 18 samples, 3 mice; 6-OHDA, eGFP = 12.8, 11.1–15.0 million/mm3, n = 18 samples, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 6C, D, G). In cre-eGFP expressing mice with knockdown of STN NMDARs the density of cortico-STN axon terminals increased in both dopamine-intact and -depleted mice relative to their eGFP expressing counterparts (vGluT1 density: vehicle, cre-eGFP = 34.5, 29.5–39.1 million/mm3; n = 18 samples, 3 mice; p < 0.05; 6-OHDA, cre-eGFP = 29.3, 26.3–34.4 million/mm3; n = 18 samples, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 6E–G). NMDAR knockdown therefore prevented the loss of cortical inputs that follows dopamine depletion. Cortico-STN axon terminal density was not significantly different in dopamine-intact and -depleted mice with STN NMDAR knockdown (p > 0.05; Figure 6E–G). Together these data suggest that following dopamine depletion increased activation of STN NMDARs, presumably due to disinhibition, triggers cortico-STN input loss.

Figure 6. Knockdown of STN NMDARs prevented loss of cortico-STN transmission and patterning in dopamine-depleted mice.

(A–B) Viral expression of eGFP (A) and cre-eGFP (B) centered on the STN (ic, internal capsule; parasagittal plane). (C, D, G) The density of vGluT1-immunoreactive axon terminals in the eGFP expressing, NMDAR-intact STN was lower in 6-OHDA-injected (D, G) versus vehicle-injected Grin1lox/lox mice (C, G). (C–G) The densities of vGluT1-immunoreactive axon terminals in the cre-eGFP expressing, NMDAR knockdown STN (E–G) were elevated relative to the eGFP expressing, NMDAR-intact STN (C, D, G) in both dopamine-depleted (D, F, G) and dopamine-intact (C, E, G) Grin1lox/lox mice. (A–F) Representative confocal micrographs. (G) Population data. (H–J) The amplitude and frequency of optogenetically evoked (blue arrow), asynchronous, miniature cortico-STN transmission in eGFP expressing, NMDAR-intact STN neurons were lower in 6-OHDA-injected versus vehicle-injected Grin1lox/lox mice. (H, I) The frequency of optogenetically evoked asynchronous cortico-STN transmission in cre-eGFP expressing, NMDAR knockdown STN neurons was significantly elevated in both vehicle- and 6-OHDA-injected Grin1lox/lox mice relative to their eGFP expressing, NMDAR-intact counterparts. (H, J) The amplitude of asynchronous cortico-STN EPSCs in STN neurons in cre-eGFP expressing, NMDAR-knockdown neurons in 6-OHDA-injected Grin1lox/lox mice was lower than in eGFP expressing, NMDAR-intact neurons from vehicle-injected Grin1lox/lox mice. (H) Representative traces. (I–J) Population data. (K–M) In eGFP-expressing NMDAR-intact neurons cortico-STN inputs optogenetically stimulated at 15 Hz less effectively patterned neuronal activity in slices from 6-OHDA- versus vehicle-injected Grin1lox/lox mice. In slices from 6-OHDA-injected Grin1lox/lox mice loss of cortico-STN patterning was largely prevented in cre-eGFP-expressing neurons with knockdown of STN NMDARs. (K) Population peristimulus time histograms. Cyan dashed line, mean of action potentials preceding optogenetic stimulation. Magenta dashed line, mean plus 3 standard deviations of action potentials preceding optogenetic stimulation. Blue rectangle, period of optogenetic stimulation. (L, M) Population data for synaptic drive and latency of action potentials in response to optogenetic stimulation. *, p < 0.05. ns, not significant. See also Tables S1–S3.

To determine the impact of NMDAR knockdown on the physiological properties of cortico-STN transmission, the cohorts of mice described above were additionally injected with an AAV expressing ChR2(H134R)-eYFP in the motor cortex. Cortico-STN inputs were then interrogated optogenetically ex vivo in the presence of Sr2+ to assess quantal properties, as described above. Neurons expressing eGFP or cre-eGFP were targeted for patch clamp recording using epifluorescent imaging. Consistent with the above data, loss of dopamine led to a reduction in the frequency and amplitude of optogenetically evoked, asynchronous cortico-STN transmission in NMDAR-intact STN neurons (frequency: vehicle, eGFP = 13.6, 9.3–18.9 Hz; n = 18 neurons, 2 mice; 6-OHDA eGFP = 6.1, 5.2–8.9 Hz; n = 26 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; amplitude: vehicle, eGFP = 12.6, 11.7–13.7 pA; n = 18 neurons, 2 mice; 6-OHDA, eGFP = 10.4, 9.0–11.4 pA; n = 26 neurons, 4 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 6H–J).

Knockdown of STN NMDARs significantly elevated the frequency of optogenetically evoked, asynchronous cortico-STN transmission in both dopamine-intact and -depleted mice relative to their NMDAR-intact counterparts (vehicle, cre-eGFP = 20.0, 14.4–41.8 Hz; n = 23 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; 6-OHDA, cre-eGFP = 17.8, 14.4–24.4 Hz; n = 23 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 6H, I). However, the amplitude of asynchronous cortico-STN transmission in NMDAR-knockdown, dopamine-depleted mice was modestly lower than in NMDAR-intact, vehicle-injected mice (6-OHDA cre-eGFP = 9.4, 8.1–12.2 pA; n = 23 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 6H, J). Thus, knockdown of STN NMDARs increased the frequency of asynchronous cortico-STN AMPAR-mediated transmission and prevented the reduction in the frequency but not the amplitude of asynchronous cortico-STN transmission that follows loss of dopamine. Knockdown of STN NMDARs also largely prevented the loss of cortico-STN synaptic patterning in dopamine-depleted mice (Figure 6K–M). In NMDAR-intact mice cortico-STN synaptic patterning was reduced by dopamine depletion (synaptic drive: vehicle, eGFP = 34.0, 24.5–37.5; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; 6-OHDA, eGFP = 11.0, 6.0–26.5; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; p < 0.05; latency: vehicle, eGFP = 2.9, 2.1–4.2 ms; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; 6-OHDA, eGFP = 21.0, 10.5–26.5 ms; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; p < 0.05; interquartile range of latency: vehicle, eGFP = 1.7, 0.6–2.3 ms; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; 6-OHDA, eGFP = 18.4, 11.9–27.4 ms; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 6K–M). In dopamine-depleted mice, knockdown of STN NMDARs increased the strength of cortico-STN patterning relative to mice with intact NMDARs (synaptic drive: 6-OHDA, cre-eGFP = 31, 22.5–40.5; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; latency: 6-OHDA, cre-eGFP = 7.4, 2.3–11.7 ms; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; p < 0.05; interquartile range of latency: 6-OHDA, cre-eGFP = 5.5, 0.9–10.2 ms; n = 20 neurons, 2 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 6K–M). In dopamine-depleted mice with knockdown of STN NMDARs cortico-STN synaptic drive was not significantly different from that in dopamine- and NMDAR-intact mice (p > 0.05; Figure 6K–M). However, the latency and range of latency of synaptically generated action potentials were modestly but significantly greater in dopamine-depleted mice with knockdown of STN NMDARs relative to dopamine- and NMDAR-intact mice (p < 0.05; Figure 6K–M).

Application of exogenous NMDA ex vivo is sufficient to mimic NMDAR-dependent synaptic and cellular plasticities in the STN of PD (Chu et al., 2015) and Huntington’s disease (Atherton et al., 2016) mice. To determine whether NMDAR activation is sufficient to downregulate cortico-STN transmission, brain slices were incubated in 25 μM NMDA for 1 hour, prior to anatomical and electrophysiological measurements. This treatment did not affect the density of STN neurons (Figure S3) and does not abolish their electrophysiological activity (Atherton et al., 2016) arguing that it is not excitotoxic. In brain slices from vehicle-injected, dopamine-intact mice, NMDAR activation ex vivo reduced both the density of vGluT1 cortico-STN terminals (vGluT1 density: control = 19.5, 15.8–23.6 million/mm3; n = 15 samples, 3 mice; NMDA-treated = 11.9, 9.7–12.9 million/mm3; n = 18 samples, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 7A–C) and the amplitude of optogenetically stimulated cortico-STN transmission (amplitude at 2.6 mW/mm2: control = 350.3, 254.2–659.4 pA; n = 13 neurons, 3 mice; NMDA-treated = 141.1, 68.1–172.8 pA; n = 13 neurons, 3 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 7G–I). However, NMDA incubation ex vivo had no effect on these parameters in brain slices from 6-OHDA-injected mice (vGluT1 density: control = 10.9, 8.9–12.5 million/mm3; n = 12, 2 mice; NMDA-treated = 11, 8.8–12.3 million/mm3; n = 12, 2 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 7D–F; amplitude at 2.6 mW/mm2: control = 155.9, 85.2–350.8 pA; n = 21 neurons, 2 mice; NMDA-treated = 189.0, 86.2–271.5 pA; n = 21 neurons, 2 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 7J–L). These data suggest that 1) NMDAR activation ex vivo was sufficient to downregulate cortico-STN transmission in slices from dopamine-intact mice 2) in dopamine-depleted mice NMDAR-dependent cortico-STN downregulation in vivo occluded the effect of NMDAR activation ex vivo. NMDAR-dependent downregulation ex vivo was similarly occluded in slices from CNO- but not vehicle-treated adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mice (Figure S3). Excessive activation of Cav1.3 channels contributes to loss of cortico-D2-SPN axospinous synapses following chronic dopamine depletion (Day et al., 2006). However, cortico-STN downregulation was still observed in dopamine-depleted transgenic Cav1.3 channel knockout (Cacna1d−/ −) mice (Platzer et al., 2000; Figure S3). Together our data suggest that STN NMDAR activation is sufficient for cortico-STN downregulation in dopamine-depleted mice and in dopamine-intact mice in which D2-SPNs have been chemogenetically activated.

Figure 7. Activation of STN NMDARs ex vivo downregulates cortico-STN transmission in brain slices from dopamine-intact but not dopamine-depleted mice.

(A–F) Activation of STN NMDARs ex vivo led to a significant reduction in the density of vGluT1-immunoreactive cortico-STN axon terminals in brain slices derived from vehicle (A–C; A, B, examples; C, population data) but not 6-OHDA-treated (D–F; D, E, examples; F, population data) mice. (G–I) Activation of STN NMDARs ex vivo led to a significant reduction in the amplitude of optogenetically stimulated cortico-STN transmission in brain slices derived from vehicle (G–I; G, H, examples; I, population data) but not 6-OHDA-treated (J–L; J, K, examples; L, population data) mice. *, p < 0.05. ns, not significant. See also Figure S3.

Increasing the strength of cortico-STN transmission relative to GPe-STN transmission ameliorates parkinsonian motor dysfunction

Given that elevated cortical patterning of the STN and STN hyperactivity are linked to motor dysfunction in PD, the combined effects of STN NMDAR knockdown on cortico-STN and GPe-STN transmission (Tables S1–3) are predicted to impair motor function. To test this prediction, we used the viral-mediated expression strategies described above to manipulate cortico-STN and GPe-STN transmission in unilateral vehicle- and 6-OHDA-injected Grin1lox/lox mice and then subjected these mice to tests of motor function. In NMDAR-intact mice dopamine depletion 1) increased the use of the forelimb ipsilateral to the injected hemisphere during the cylinder test (Schallert et al., 2000) (% ipsilateral forelimb use: eGFP, vehicle = 42.3, 36.0–45.0%; n = 11 mice; Movie S1; eGFP, 6-OHDA = 78.3, 72.0–83.5%; n = 7 mice; Movie S2; p < 0.05; Figure 8A) 2) increased rotational behavior towards the injected hemisphere (% ipsiversive rotations: eGFP, vehicle = 48.7, 37.4–71.4%; n = 12 mice; eGFP, 6-OHDA = 100.0, 100.0–100.0 %; n = 10 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 8B) 3) reduced distance traveled in the open field (distance traveled in minutes 3–5: eGFP, vehicle = 7.6, 4.9–10.3 m; n = 12 mice; eGFP, 6-OHDA = 2.9, 0.9–3.7 m; n = 10 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 8C, D; c.f. Figure S4), consistent with hemiparkinsonian motor dysfunction. However, contrary to the above prediction, aspects of motor behavior in NMDAR-knockdown, dopamine-depleted mice were improved relative to NMDAR-intact, dopamine-depleted mice (% ipsilateral forelimb use: cre-eGFP, 6-OHDA = 57.6, 50.8–62.5%; n = 9 mice; Movie S3; p < 0.05; Figure 8A; distance traveled in minutes 3–5 in the open field: cre-eGFP, 6-OHDA = 5.9, 3.6–7.7 m; n = 10 mice; p < 0.05; Figure 8C, D; c.f. Figure S4). However, ipsiversive rotational behavior was not improved (% ipsiversive rotations: cre-eGFP, 6-OHDA = 96.7, 66.7–100%; n = 10 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 8B). Interestingly, the motor behavior of NMDAR knockdown, dopamine-intact mice was not significantly impaired relative to NMDAR-intact, dopamine-intact mice (% ipsilateral forelimb use: cre-eGFP, vehicle = 38.7, 35.6–45.3%; n = 6 mice; Movie S4; p > 0.05; Figure 8A; % ipsiversive rotations: cre-eGFP, vehicle = 44.2, 33.3–72.7%; n = 6 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 8B; distance traveled in minutes 3–5 in the open field: cre-eGFP, vehicle = 7.0, 4.5–9.1 m; n = 6 mice; p > 0.05; Figure 8C, D; c.f. Figure S4). Dopamine-depleted mice with NMDAR knockdown restricted to structures overlying the STN exhibited similar ipsilateral forelimb use to dopamine-depleted mice with eGFP expression in the STN (% ipsilateral forelimb use: cre-eGFP outside STN, 6-OHDA = 82.6, 71.5–87.5%; n = 5; p > 0.05; Figure S5). Taken together, the behavioral data are inconsistent with the view that an increase in the strength of cortico-STN transmission relative to GPe transmission promotes motor dysfunction. Rather, our physiological, anatomical and behavioral data argue that following loss of dopamine a maladaptive decrease in cortico-STN transmission strength relative to GPe-STN transmission strength (Chu et al., 2015) contributes to impaired movement.

Figure 8. Knockdown of STN NMDARs reduced motor dysfunction in dopamine-depleted mice but had no discernable impact on motor function in dopamine-intact mice.

(A–D) Ipsilateral forelimb use (A), ipsiversive rotational behavior (B) and distance traveled in the open field (C, D) were compared in vehicle-injected dopamine-intact and 6-OHDA-injected dopamine-depleted Grin1lox/lox mice. eGFP-expressing NMDAR-intact, 6-OHDA-injected dopamine-depleted mice exhibited significantly increased ipsilateral forelimb use (A), ipsiversive rotational behavior (B) and significantly reduced travel in the open field (C, D) compared to eGFP-expressing NMDAR-intact, vehicle-injected dopamine-intact mice. cre-eGFP-expressing NMDAR-knockdown, 6-OHDA-injected dopamine-depleted mice exhibited reduced ipsilateral forelimb use (A) and increased distance traveled in the open field (C, D) relative to eGFP-expressing STN NMDAR-intact, 6-OHDA-injected dopamine-depleted mice. (A–D) The motor behavior of eGFP-expressing STN NMDAR-intact, vehicle-injected dopamine-intact mice and cre-eGFP-expressing STN NMDAR-knockdown, vehicle-injected dopamine-intact mice were not significantly different. (A–C) Population data. (D) Examples of open field activity. *, p < 0.05. ns, not significant. See also Figures S4 and S5 and Tables S1–3.

DISCUSSION

A wealth of evidence has suggested that the cortico-STN hyperdirect pathway plays a key role in patterning pathological STN activity in PD. Multiple aspects of parkinsonian cortico-STN activity are associated with motor symptoms, including excessive coherent and correlated activity and burst firing (Delaville et al., 2015; Blumenfeld and Brontë-Stewart, 2015; Sharott et al., 2014; Sanders et al., 2013; Shimamoto et al, 2013; Zaidel et al., 2009). Furthermore, “correction” of parkinsonian cortico-STN activity is correlated with the therapeutic effects of dopamine-based medications and STN deep brain stimulation (DBS) (Blumenfeld and Brontë-Stewart, 2015; Delaville et al., 2015; Eusebio et al., 2012; Tachibana et a., 2011). Theoretical studies also consistently link the hyperdirect cortico-STN pathway to pathological activity in the STN and wider cortico-basal ganglia thalamo-cortical circuit (Moran et al., 2011; Pavlides et al., 2015). Indeed, stimulation of cortico-STN axons during STN DBS has been proposed to be particularly critical for therapy (Gradinaru et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012; de Hemptinne et al., 2015; Sanders and Jaeger, 2016).

Because cortico-STN axon terminals exhibit NMDAR-dependent LTP (Chu et al., 2015), we predicted that parkinsonian cortico-STN activity would both promote and be promoted by this form of plasticity. However, we discovered that cortico-STN transmission strength was profoundly reduced in parkinsonian mice and the pre- and post-synaptic components of cortico-STN synapses were lost. These data are consistent with loss of cortico-STN synapses in the MPTP-treated non-human primate model of PD and the reduced “hyperdirect pathway” response of STN and basal ganglia output neurons following electrical stimulation of the cortex in vivo in dopamine-depleted rodents and monkeys (Kita and Kita, 2011; Mathai et al., 2015). The pharmacological profile, rapid kinetics and voltage-dependence of cortico-STN transmission in parkinsonian mice also suggest a reduction in GluA2 AMPAR subunit expression and therefore an increase in Ca2+-permeable AMPAR-mediated transmission (Isaac et al., 2007; Liu and Savtchouk, 2012). However, despite the loss of lower conductance GluA2-containing AMPARs, the amplitude of asynchronous cortico-STN EPSCs decreased modestly. NMDAR-dependent LTP of the cortico-STN pathway was also impaired in dopamine-depleted mice and, in contrast to the striatum (Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011), not rescued by acute dopamine receptor activation. Whether impairment of LTP is due to synapse loss and/or alterations in AMPAR and/or NMDAR expression requires further investigation.

Chronic chemogenetic activation of D2-SPNs in dopamine-intact mice was sufficient to downregulate cortico-STN transmission (Farrell et al., 2013), arguing that elevated striatal inhibition of GPe-STN neurons led to disinhibition of the STN, which triggered cortical input loss. Consistent with this mechanism, chemogenetic activation of D2-SPNs elevated inhibitory transmission to GPe neurons and reduced GPe activity. Thus, in dopamine-intact mice alterations in circuit activity that mimic those in PD are sufficient for cortico-STN downregulation (Mallet et al., 2006). In PD models, increased inhibition of GPe-STN neurons (Mallet et al., 2006) and antiphasic GPe and STN activity (Mallet et al., 2008b) increase the probability that synaptic excitation of the STN is unopposed by GABAergic inhibition (Kita and Kita, 2011). Because excessive NMDAR activation triggers loss of glutamatergic synapses in a variety of diseases and brain regions (Andres at al., 2013; Hasbani et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2008; Meller et al., 2008), we investigated whether NMDARs also underlie downregulation of cortico-STN transmission. In PD mice, knockdown of STN NMDARs largely prevented loss of cortico-STN inputs, transmission and patterning Knockdown of STN NMDARs also increased the number of cortico-STN inputs in dopamine-intact mice relative to NMDAR-expressing controls (cf Adesnik et al., 2008; Mu et al., 2015). Activation of STN NMDARs ex vivo was also sufficient to reduce cortico-STN axon terminal density and transmission in brain slices from dopamine-intact mice. However, this action was occluded in slices from PD mice or chemogenetically activated adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mice, consistent with prior NMDAR-triggered cortico-STN downregulation in vivo. Although the responsible signaling elements downstream of STN NMDARs have not been identified, NMDAR-triggered loss of glutamatergic synapses is mediated through enzymes and enzyme complexes including calpain, caspase 3, PP1/PP2, and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Andres et al., 2013; Henson et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2008; Meller et al., 2008; Waataja et al., 2008). Thus, in addition to their role in heterosynaptic and homosynaptic LTP of GPe-STN and cortico-STN transmission, respectively, STN NMDARs act as global activity sensors that regulate both the number and balance of GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic inputs. Interestingly, the baseline density of cortico-STN axon terminals varied between the wild type and transgenic/knockout mouse lines used in this study. The reasons are unclear but may reflect alterations to basal circuit activity produced by transgene expression or ion channel knockout.

Overall, our findings indicate that elevated cortico-STN correlation and coherence in PD are not due to strengthening of cortico-STN transmission. Abnormal GPe-STN transmission may however promote parkinsonian cortico-STN activity. GPe-STN inputs predominantly act at GABAARs and are sufficiently powerful and hyperpolarizing to synchronize STN activity (Baufreton et al., 2005). GPe-STN inputs also de-inactivate postsynaptic Nav1, Cav1 and Cav3 channels in STN neurons, which facilitates integration of subsequent excitatory synaptic transmission (Bevan et al., 2002; Baufreton et al., 2005). Because cortico-STN and GPe-STN transmission are relatively phase-offset following loss of dopamine (Mallet et al., 2008b), an increase in the synchrony of GPe-STN firing (Mallet et al., 2008b) and transmission strength (Chu et al., 2015) should potently facilitate the response of STN neurons to cortical inputs (Baufreton et al., 2005), despite their downregulation. Thus, an increase in synchronous activity and transmission strength in the indirect pathway may contribute to the abnormally correlated and coherent nature of cortico-STN activity in PD. Elucidating the relative impact of optogenetic or chemogenetic manipulation of cortico-STN neurons, D2-SPNs or GPe-STN neurons on parkinsonian STN activity and associated motor dysfunction should help to resolve this issue.

The product of the frequency and amplitude of cortico-STN AMPAR- (this study; Table S1) and GPe-STN GABAAR-mediated (Chu et al., 2015; Table S2) univesicular transmission in Grin1lox/lox mice as measures of transmission strength reveals that: 1) dopamine depletion reduced the ratio of cortico-STN excitation to GPe-STN inhibition approximately 4-fold in NMDAR-intact mice (Table S3) 2) knockdown of STN NMDARs increased the ratio of cortical excitation to GPe inhibition approximately 3-fold and 14-fold in dopamine-intact and -depleted mice, respectively (Table S3). According to rate models of basal ganglia function and dysfunction (e.g. Albin et al., 1999), the downregulation of cortico-STN synaptic transmission and upregulation of GPe-STN synaptic transmission in PD mice should be homeostatic in nature and oppose STN hyperactivity. However, knockdown of STN NMDARs, which massively increased the strength of synaptic excitation relative to inhibition (Chu et al., 2015), ameliorated motor dysfunction in PD mice. It is conceivable that NMDAR knockdown was therapeutic because NMDAR-mediated patterning was eliminated, but this is unlikely given the dominant influence of AMPAR-mediated cortico-STN patterning. Thus, reduction of cortico-STN transmission strength relative to GPe-STN transmission in this model of mid- to late-stage PD appears to be maladaptive and prevention of this shift is therapeutic. It remains to be determined whether prevention of hyperdirect pathway downregulation or disconnection of the indirect pathway or the combination of these effects contributes to improved motor function. Certainly, GPe-STN neurons appear to be critical for the expression of motor dysfunction, as evinced by the persistent therapeutic effect of their selective optogenetic stimulation in PD mice (Mastro et al., 2017).

STAR Methods

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-NeuN antibody, clone A60 | MilliporeSigma | Cat#MAB377; Lot#:2763860; RRID: AB_2298772 |

| Anti-Tyrosine Hydroxylase antibody, clone LNC1 | MilliporeSigma | Cat#MAB318; RRID: AB_2201528 |

| Polyclonal guinea pig anti-vGluT1 | Synaptic Systems | Cat#135304; Lot#135304/32 |

| Alexa Fluor-488 donkey anti-mouse IgG | Jackson ImmunoReseach Laboratories, Inc | Cat#715-545-150; Lot#125479; RRID: AB_2340846 |

| Alexa Fluor-594 donkey anti-guinea pig IgG | Jackson ImmunoReseach Laboratories, Inc | Cat#706-585-148; Lot#127241; RRID: AB_2340474 |

| Alexa Fluor-594 donkey anti-mouse IgG | Jackson ImmunoReseach Laboratories, Inc | Cat#: 715-585-150; RRID: AB_2340854 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| AAV9.hSyn.hChR2(H134R)-eYFP.WPRE.hGH | UPenn Vector Core | Cat# AV-9-26973P; (Addgene26973P) |

| AAV9.hSyn.eGFP.WPRE.bGH | UPenn Vector Core | Cat# AV-9-PV1696 |

| AAV9.hSyn.HI.eGFP-Cre.WPRE.SV40 | UPenn Vector Core | Cat# AV-9-PV1848 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| 6-Hydroxydopamine hydrobromide | Tocris Bioscience | Cat#2547/50 |

| CGP 55845 hydrochloride | Abcam Inc | Cat#ab120337 |

| Clozapine N-oxide | Tocris Bioscience | Cat#4936 |

| D-APV | Abcam Inc | Cat#ab120003 |

| Desipramine hydrochloride | Sigam-Aldrich | Cat#P3900 |

| DNQX disodium salt | Abcam Inc | Cat#ab120169 |

| GYKI 53655 hydrochloride | Abcam Inc | Cat#ab120490 |

| L-Glutathione reduced | Sigam-Aldrich | Cat#G4251 |

| Naspm trihydrochloride | Tocris Bioscience | Cat#2766 |

| N-Methyl D-aspartic acid | Tocris Bioscience | Cat#0114 |

| Pargyline hydrochloride | Sigam-Aldrich | Cat#P8013 |

| QX-314 bromide | Abcam Inc | Cat#ab120117 |

| Sodium pyruvate | Sigam-Aldrich | Cat#P2256 |

| SR95531 (Gabazine) | Abcam Inc | Cat#ab120042 |

| Strontium chloride | Tocris Bioscience | Cat#4749 |

| Tetrodotoxin citrate | Tocris Bioscience | Cat#120055 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Deposited Data | ||

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: adora2A-rM3Ds-mcherry: B6.Cg-Tg(Adora2a- Chrm3*,-mCherry)AD6Blr/J | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:017863; RRID: IMSR_JAX:017863 |

| Mouse: Grin1lox/lox: B6.129S4-Grin1tm2stl/J | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:005246; RRID: IMSR_JAX:005246 |

| Mouse: Cacna1d−/− | D.J. Surmeier laboratory, Northwestern University; Day et al., 2006 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ANYmaze (version 4.99) | Stoelting Co. | N/A |

| Clampfit (version 10.5) | Molecular Devices | N/A |

| Igor Pro (version 6.37) | Wavemetrics Inc | RRID: SCR_000325 |

| Minianalysis (version 6.0.7) | Synaptosoft Inc | RRID: SCR_014441 |

| Neurolucida (version 11.03) | MBF Bioscience | RRID: SCR_001775 |

| Neurolucida Explorer (version 11.08) | MBF Bioscience | N/A |

| NIH ImageJ (version 1.47) | NIH | RRID: SCR_003070 |

| OriginPro (version 2015) | OriginLab Co. | RRID: SCR_014212 |

| pClamp (version 10.5) | Molecular Device | RRID: SCR_011323 |

| Prism (version 6.0h) | Graphpad software Inc | RRID: SCR_002798 |

| R (version 3.3.1) | http://www.R-project.org/ | RRID: SCR_001905 |

| Other | ||

| sliceGolgi Kit | Bioenno Lifesciences | Cat#003760 |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Requests for reagents and resources should be directed to Mark D. Bevan, Ph.D., Department of Physiology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, 303 E. Chicago Ave, IL 60611, Chicago, U.S.A. Email: m-bevan@northwestern.edu

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL DETAILS

Experiments were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with NIH guidelines. Adult male C57BL/6 mice (77, 65–83 days old; n = 92; Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA), Grin1lox/lox mice (94, 78–109 days old; n = 71; B6.129S4-Grin1tm2stl/J; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), homozygous adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mice (81, 61–94 days old; n = 23; B6.Cg-Tg(Adora2a-Chrm3*,-mCherry)AD6Blr/J; Jackson Laboratory), and Cacna1d−/− (87, 84–111 days old; n = 11; Platzer et al., 2000) mice were used. Transgenic mice were backcrossed for at least 8 generations prior to use. All mice were subject to regular veterinary inspection and only to the experimental procedures detailed here, and maintained on a conventional 14 hour light/10 hour dark cycle with free access to food and water. Littermates were assigned equally and randomly to treatment groups.

METHOD DETAILS

Stereotaxic injection of viral vectors and 6-OHDA

Viral vectors (University of Pennsylvania Vector Core, Philadelphia, PA, USA) were injected stereotaxically (Neurostar, Tubingen, Germany) under (1–2%) isoflurane anesthesia (Smiths Medical ASD, Inc., Dublin, OH, USA). hChR2(H134R)-eYFP was expressed in the primary motor cortex of C57BL/6, adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry or Grin1lox/lox mice through unilateral injections of AAV9.hSyn.hChR2(H134R)-eYFP.WPRE.hGH (1013 GC/mL; coordinates: AP, +0.6, +1.2, and +1.8 mm; ML, +1.5 mm; DV, −1.0 mm; 0.3 μl per injection). eGFP or cre-eGFP was expressed in the STN of Grin1lox/lox mice through unilateral injection of AAV9.hSyn.eGFP.WPRE.bGH or AAV9.hSyn.HI.eGFP-Cre.WPRE.SV40, respectively (2 × 1012 GC/mL; coordinates: AP −2.06 mm; ML, +1.4 mm; DV, −4.44 mm; 0.25 μl). In order to lesion midbrain dopamine neurons or to control for surgical injection, 6-OHDA (3–5 mg/ml) or vehicle was injected into the medial forebrain bundle (coordinates: AP −0.7 mm; ML, +1.2 mm; DV, −4.7 mm; 1.5 μl), respectively. The selectivity and toxicity of 6-OHDA were enhanced through intraperitoneal (IP) injection of desipramine (25 mg/kg) and pargyline (50 mg/kg), respectively. Brain slices/sections were prepared from AAV-, 6-OHDA- and vehicle-injected mice approximately 2–4 weeks after injection.

Slice preparation

AAV-injected and 6-OHDA−/vehicle-injected mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (87/13 mg/kg, IP) and perfused transcardially with sucrose-based artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at 1–4°C, equ ilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and containing (in mM): 230 sucrose, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 10 MgSO4, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4 and 0.5 CaCl2. Parasagittal brain slices (electrophysiology, 250 μm; immunohistochemistry, 200 μm) containing the STN were prepared in the same solution using a vibratome (VT1200S; Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Slices were held in ACSF, equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and containing (in mM): 126 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 sodium pyruvate and 0.005 L-glutathione at 35 °C for 30 min and the n at room temperature until electrophysiological recording and/or immersion fixation and/or NMDA pre-treatment.

Ex vivo electrophysiology and optogenetic interrogation

Slices were transferred to a recording chamber, perfused at a rate of ~5 ml/min with synthetic interstitial fluid (SIF) at 35–37 °C, equ ilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and containing (in mM): 126 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 KCl, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.5 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4. SR-95531 (GABAzine, 10 μM) and CGP55845 (2 μM) were routinely added to inhibit GABAARs and GABABRs, respectively. In a subset of experiments, extracellular Ca2+ was replaced with 2 mM Sr2+ to promote asynchronous cortico-STN transmission. Somatic recordings were obtained under visual guidance (Axioskop FS2; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using computer-controlled manipulators (Luigs & Neumann, Ratingen, Germany) and a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and a Digidata 1440A digitizer controlled by PClamp10 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Signals were low-pass filtered online at 10 kHz and sampled at 50 kHz. Cell and electrode capacitances, series resistance and junction potentials were compensated electronically.

Cortico-STN EPSCs were measured in the whole-cell configuration using borosilicate glass micropipettes filled with a cesium methanesulfonate-based internal solution containing (in mM): 135 CH3O3SCs, 10 QX-314, 10 HEPES, 5 phosphocreatine, 3.8 NaCl, 2 Mg1.5ATP, 1 MgCl2, 0.4 Na3GTP, 0.1 Na4-EGTA (pH 7.2, 290 mOsm) except for the experiments in which LTP of cortico-STN inputs was studied. In these experiments a potassium gluconate-based internal solution was used, containing (in mM): 130 C6H11KO7, 10 HEPES, 5 phosphocreatine, 3.8 NaCl, 2 Mg1.5ATP, 1 MgCl2, 0.4 Na3GTP, 0.1 Na4EGTA, (pH 7.2, 290 mOsm). Cortico-STN EPSCs were measured at −80 mV, except when the rectification of AMPAR-mediated transmission or the ratio of AMPAR:NMDAR transmission were studied. In these cases EPSCs were measured at both −80 mV and +40 mV. Cortico-STN synaptic patterning was studied using the loose-seal, cell-attached configuration in order to minimize perturbation of the integrative properties of postsynaptic STN neurons. In the loose-seal, cell-attached configuration glass pipettes were filled with (in mM) 140 NaCl, 23 glucose, 15 HEPES, 3 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 1.6 CaCl2 (pH 7.2 with NaOH, 300–310 mOsm). Optogenetic stimulation was delivered via a 63X objective lens (Carl Zeiss) using a 470 nm light emitting diode (OptoLED; Cairn Research, Faversham, Kent, UK). Cortico-STN transmission was evoked by 1 ms duration optogenetic stimulation of cortico-STN axon terminals. The pattern of stimulation specific to each experiment is detailed in the main manuscript.

In vivo electrophysiology

Adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mice were first injected with urethane (1.24 g/kg, IP) and then 60 minutes later with supplements (up to 0.49 g/kg additional, IP) every 20 minutes until the toe-pinch withdrawal reflex was abolished. Mice were then placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) for the duration of the recording session with urethane supplementation, as required. Craniotomies were drilled over the motor cortex (coordinates: AP: +1.4, ML: +1.5 mm) and GPe (AP: −0.1, ML: +1.7 mm) and irrigated with HEPES-buffered saline during electrode penetration. EEG signals and single unit GPe activity were acquired from a peridural skull screw implanted over M1 and a silicon tetrode array in the GPe, respectively (NeuroNexus Technologies, Ann Arbor, MI), with a reference wire implanted in the ipsilateral temporal musculature. Recordings were made using a 64-channel Digital Lynx (Neuralynx, Bozeman, MT) data acquisition system at a sampling rate of 40 kHz. The EEG was filtered between 0–400 Hz and single unit activity was bandpass filtered during acquisition between 200–9,000 Hz. Following establishment of cortical slow-wave activity and isolation of single unit GPe activity, baseline activity was recorded for 15–20 minutes. 1 mg/kg CNO was then administered (SC) to activate rM3Ds-expressing D2-SPNs and recording continued for at least 45 min post-injection. Finally, mice were administered ketamine/xylazine (87/13 mg/kg, IP), perfuse fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M PB, pH 7.4 and post-fixed overnight, as described above. Seventy μm thick coronal sections were taken using a vibratome to visualize the sites of recording. Silicon probes were immersed prior to usein lipophilic florescent dye (DiI, 20 mg/ml in 50% acetone/methanol) to facilitate reconstruction of recording sites. A combination of template matching, principal component analysis, and manual clustering were used to isolate single unit activity (Plexon Offline Sorter; Plexon, Dallas, Texas).

Immunohistochemistry

vGluT1

200 μm thick parasagittal brain slices containing the STN were prepared as stated above, immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) at room temperature for 15 min and then washed in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4). After washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), slices were incubated in PBS plus 0.2% Triton X-100 and 2% normal donkey serum (NDS; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature before incubation with polycolonal guinea pig anti-vGluT1 (1:1000, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany) for 48 h at 4 °C. Slices were washed three times in PBS and then incubated in Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-guinea pig IgG (1:250, Jackson Immunoresearch) for 90 min at room temperature. Slices were then mounted in ProLong Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) on glass slides and coverslipped.

NeuN

To visualize viral expression of hChR2(H134R)-eYFP, eGFP, cre-eGFP or mCherry, 200–250 μm thick brain slices were prepared as described above and then immersion fixed with 4% PFA (0.1 M PB, pH 7.4) or mice were deeply anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (87/13 mg/kg, IP) and then transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline for 2 min followed by 4% PFA in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4) for 30 min. Perfuse-fixed brains were then removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA (0.1 M PB, pH 7.4) at 4 °C overnight. Parasagittal sections (70 μm) were prepared using a Leica VT 1000S vibratome (Leica Microsystems Inc.) and washed with PBS. Slices/sections were then processed for immunohistochemical detection of NeuN, an antigen expressed by neurons, commonly used to delineate brain structures. Slices/sections were incubated in mouse anti-NeuN antibody (1:200, EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) in PBS plus 0.2% Triton X-100 and 2% NDS for 48 h at 4°C. After washing, slices/s ections were incubated in Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:250, Jackson Immunoresearch) for 90 min at room temperature. Slices/sections were then mounted in ProLong Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) on glass slides and coverslipped.

Confocal imaging and analysis

hChR2(H134R)-eYFP, eGFP, cre-eGFP, mCherry and immunohistochemical labeling were visualized using confocal laser scanning microscopy (A1R; Nikon, Melville, USA). Images of vGluT1 and NeuN immunoreactivity were acquired using a 100 X, 1.45 NA oil immersion objective with a digital zoom of 2.5 (x/y, 1024 X 1024 pixels; 50 nm per pixel; z step, 150 nm) and a 40X, 1.0 NA oil immersion objective with no digital zoom (x/y, 1024 X 1024 pixels; 310 nm per pixel; z step, 1 μm), respectively. Images were acquired using identical settings and analyzed without post-processing. The densities of vGluT1-and NeuN immunoreactive structures were assessed using NIH ImageJ and quantified using the optical dissector method (West, 1999). Sample sites were chosen using a grid (vGluT1: frame size, 20 X 20 μm; NeuN: frame size, 50 × 50 μm) that was superimposed randomly on each image stack. Stereological counting commenced and was terminated at an optical section ~ 5 μm and ~ 10 μm below the slice surface, respectively. Look-up and reference planes for vGluT1 and NeuN analysis were separated by 150 nm and 5 μm, respectively. Dopaminergic innervation was assessed through immunohistochemistry for tyrosine hydroxylase, as described previously (Fan et al., 2012). In the 83 vehicle-injected (45 C57BL/6, 33 Grin1lox/lox, 5 Cacna1d−/−) and 91 6-OHDA-injected mice (47 C57BL/6, 38 Grin1lox/lox, 6 Cacna1d−/−) used in this study ipsilateral striatal TH immunoreactivities were 104.6, 89.0–124.5% and 2.0, 0.0–7.4% of the contralateral hemisphere, respectively (p < 0.05).

Golgi impregnation

Golgi impregnation of STN neurons was performed as per manufacturer's instructions using the sliceGolgi Kit (Bioenno lifesciences, Santa Ana, CA, USA). Briefly, mice were deeply anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (87/13 mg/kg, IP) and then perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline, followed by fixation with freshly prepared fixative. Brains were post-fixed in the same fixative overnight at 4°C, before preparation of horizontal 200 μm thick vibratome slices (VT1000S; Leica Microsystems Inc.). Sections containing the STN were then immersed in impregnation solution (solution B) for 5 days at room temperature in the dark followed by washing with PBS plus 0.3% Triton X100. Slices were then immersed in staining solution (Solution C) and post-staining solution (Solution D) for 5 min and 3 min respectively. After washing with 0.01 M PBS plus 0.3% Triton X100, brain slices were mounted on glass slides in a mixture of 50% glycerol and PBS, and then coverslipped. Golgi-impregnated STN neurons were visualized and traced on a Zeiss Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using a UplanApo 60X/1.2 NA water immersion objective (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), an AxioCam CCD camera (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and Neurolucida software (MFB Bioscience, Williston, VT, USA). Morphological parameters were analyzed and quantified using NeuroExplorer (MFB Bioscience), including dendritic length and number of primary dendrites. The number of dendritic intersections with Sholl circles (a series of concentric circles centered on the soma) was also measured.

Behavioral testing

Adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mice were subcutaneously administered CNO (1 mg/kg) or vehicle approximately every 12 hours over 2–3 consecutive days in order to chronically chemogenetically activate D2-SPNs and to control for injection, respectively. Mice were placed in the center of an open field apparatus (40 cm X 40 cm X 35 cm) and locomotor activity was monitored for 5 min, approximately 45 minutes before and 30 mins after CNO (1 mg/kg, sc) or vehicle injection (sc) using a video-tracking system (ANY-maze, Stoelting CO, Wood Dale, IL).

The motor behavior of unilateral vehicle- and 6-OHDA-injected Grin1lox/lox mice in which eGFP or cre-eGFP was virally expressed in the STN ipsilateral to the injected hemisphere was assessed in the open field as described for Adora2A-rM3Ds-mCherry mice, except that ipsiversive and contraversive rotational behavior relative to the injected hemisphere were also quantified. In addition, mice were placed in a glass 600 ml beaker (diameter, 9.5 cm; height, 12 cm) and spontaneous forelimb placements on the vertical walls of the beaker were recorded using a digital camcorder (VIXIA HF R40 Full HD Camcorder; Canon, Melville, NY, USA). The beaker was flanked by mirrors to provide a 360o view. Forelimb placements were categorized from digital movies as ipsilateral or contralateral to the vehicle or 6-OHDA-injected hemisphere or both when the two forelimbs were placed simultaneously (Schallert et al., 2000).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed blinded to treatment condition using ANY-maze (Stoelting), Clampfit 10 (Molecular Devices), IgoPro 6 & 7 (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR, USA), Minianalysis (Synaptosoft Inc., Fort Lee, NJ, USA), NIH ImageJ and OriginPro 2015 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) or R (http://www.R-project.org/). In order to minimize assumptions concerning the distribution of data, non-parametric statistical tests were applied. Thus, data are reported as median and interquartile range. Data was excluded in the rare cases that a technical issue was apparent e.g. intracerebral injection produced a lesion or immunohistochemical detection failed completely, most likely due to a processing error. An α-level of 0.05 was used for two-way statistical comparisons performed with the Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired data (represented with box plots), the Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired data (tilted line segment plots). Where datasets were used for multiple comparisons the p-value was adjusted to maintain the family-wise error rate at 0.05 using the Holm-Bonferroni method (Holm, 1979). Box plots illustrate median (central line), interquartile range (box) and 10–90% range (whiskers). For the primary findings reported in the manuscript, sample sizes for Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon tests were estimated to achieve a minimum of 80% power using formulae described by Noether (1987). The effect sizes used in these power calculations were estimated using data randomly drawn from uniform distributions (runif() function in R). For Mann-Whitney tests, with a 50 percentile change in median between groups X and Y (the interquartile ranges of the groups don’t overlap) P(Y > X) ≈ 0.88 giving an estimation that at least 10 observations per group would be needed to achieve 80% power; for a 25 percentile change (the median of Y falls outside the interquartile range of X) P(Y > X) ≈ 0.72 and the estimated requirement is at least 27 observations per group. For Wilcoxon tests, if all pairs of observations show the same direction of change, P(X + X’ > 0) = 1 giving an estimation that at least 10 observations would be needed to achieve 80% power (note though that it is possible to show empirically that 6 observations gives 100% power in this case); if 90% of observations show the same direction of change, P(X + X’ > 0) ≈ 0.98 and the estimated requirement is at least 12 pairs of observations.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Original, processed, and analyzed data are available upon request. Sources of software are detailed in the KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

Supplementary Material

Spontaneous forelimb placement behavior of a STN NMDAR-intact (eGFP-expressing), dopamine intact (vehicle-injected) Grin1lox/lox mouse.

Spontaneous forelimb placement behavior of a STN NMDAR intact (eGFP-expressing), dopamine-depleted (6-OHDA-injected) Grin1lox/lox mouse.

Spontaneous forelimb placement behavior of a STN NMDAR knockdown (cre-eGFP-expressing), dopamine-depleted (6-OHDA-injected) Grin1lox/lox mouse.

Spontaneous forelimb placement behavior of a STN NMDAR knockdown (cre-eGFP-expressing), dopamine-intact (vehicle-injected) Grin1lox/lox mouse.

HIGHLIGHTS.

cortico-STN synaptic transmission is reduced by 50–75% in PD mice

increased striato-pallidal transmission triggers cortico-STN input loss

cortico-STN input loss in PD mice is NMDAR-dependent

reduction of STN plasticity is therapeutic in PD mice

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH NINDS grants 2R37 NS041280, P50 NS047085, 5T32 NS041234 and F31 NS090845. Confocal imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy, which was supported by NCI CCSG grant P30 CA060553. The authors thank DJ Surmeier, CJ Wilson and the rest of the Bevan lab for comments on this study and S Ulrich and DR Schowalter for mouse colony management.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS Conceptualization, H.-Y.C. and M.D.B.; Methodology, Formal Analysis, and Investigation, H.-Y.C., E.L.M., R.F.K., J.F.A., and M.D.B.; Writing – Original Draft, H.-Y.C. and M.D.B.; Writing – Review and Editing, H.-Y.C., E.L.M., R.F.K., J.F.A., and M.D.B.; Visualization, H.-Y.C., E.L.M., R.F.K., and M.D.B.; Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition, M.D.B.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adesnik H, Li G, During MJ, Pleasure SJ, Nicoll RA. NMDA receptors inhibit synapse unsilencing during brain development. PNAS. 2008;105:5597–5602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800946105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:366–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres AL, Regev L, Phi L, Seese RR, Chen Y, Gall CM, Baram TZ. NMDA receptor activation and calpain contribute to disruption of dendritic spines by the stress neuropeptide CRH. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16945–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1445-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton JF, Wokosin DL, Ramanathan S, Bevan MD. Autonomous initiation and propagation of action potentials in neurons of the subthalamic nucleus. J Physiol. 2008;586:5679–700. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso-Chinea P, Castle M, Aymerich MS, Lanciego JL. Expression of vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 in the cells of origin of the rat thalamostriatal pathway. J Chem Neuroanat. 2008;35:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baufreton J, Atherton JF, Surmeier DJ, Bevan MD. Enhancement of excitatory synaptic integration by GABAergic inhibition in the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8505–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1163-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baunez C, Nieoullon A, Amalric M. In a rat model of parkinsonism, lesions of the subthalamic nucleus reverse increases of reaction time but induce a dramatic premature responding deficit. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6531–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06531.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MD, Francis CM, Bolam JP. The glutamate-enriched cortical and thalamic input to neurons in the subthalamic nucleus of the rat: convergence with GABA-positive terminals. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:491–511. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MD, Magill PJ, Hallworth NE, Bolam JP, Wilson CJ. Regulation of the timing and pattern of action potential generation in rat subthalamic neurons in vitro by GABA-A IPSPs. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1348–62. doi: 10.1152/jn.00582.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld Z, Brontë-Stewart H. High Frequency Deep Brain Stimulation and Neural Rhythms in Parkinson's Disease. Neuropsychol Rev. 2015;25:384–97. doi: 10.1007/s11065-015-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan JW, Abercrombie ED. Age-dependent alterations in the cortical entrainment of subthalamic nucleus neurons in the YAC128 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;78:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu HY, Atherton JF, Wokosin D, Surmeier DJ, Bevan MD. Heterosynaptic regulation of external globus pallidus inputs to the subthalamic nucleus by the motor cortex. Neuron. 2015;85:364–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, Wang Z, Ding J, An X, Ingham CA, Shering AF, Wokosin D, Ilijic E, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Mugnaini E, Deutch AY, Sesack SR, Arbuthnott GW, Surmeier DJ. Selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses on striatopallidal neurons in Parkinson disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:251–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaville C, McCoy AJ, Gerber CM, Cruz AV, Walters JR. Subthalamic nucleus activity in the awake hemiparkinsonian rat: relationships with motor and cognitive networks. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6918–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0587-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hemptinne C, Swann NC, Ostrem JL, Ryapolova-Webb ES, San Luciano M, Galifianakis NB, Starr PA. Therapeutic deep brain stimulation reduces cortical phase-amplitude coupling in Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:779–86. doi: 10.1038/nn.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eusebio A, Cagnan H, Brown P. Does suppression of oscillatory synchronisation mediate some of the therapeutic effects of DBS in patients with Parkinson's disease? Front Integr Neurosci. 2012;6:47. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]