Abstract

Objective

Many adolescents needing specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment never access care. We examined initiation and engagement with addiction and/or psychiatry treatment among adolescents referred to treatment from a trial comparing two different modalities of delivering Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) to Usual Care in pediatric primary care. We hypothesized that both intervention arms would have higher initiation and engagement rates than usual care.

Methods

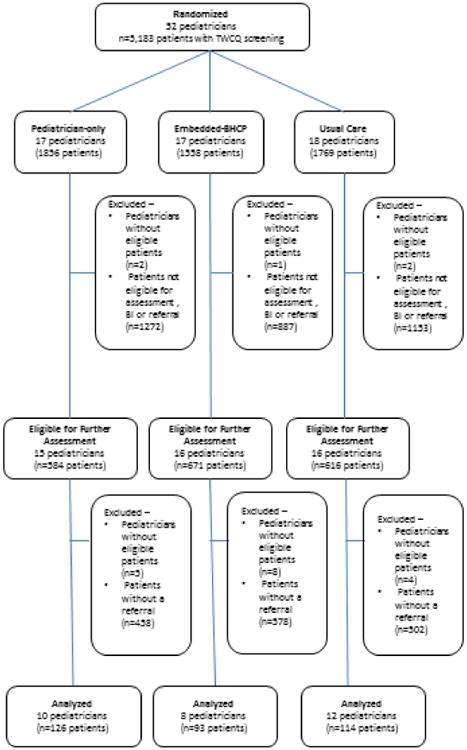

We randomized all pediatricians (n=52) in a pediatric primary care clinic to three arms: 1) pediatrician-only arm, in which pediatricians were trained to deliver SBIRT for substance use and/or mental health problems; 2) embedded-behavioral health clinician (embedded-BHC arm), in which pediatricians referred adolescents who endorsed substance use and/or mental health problems to a BHC; and 3) Usual Care (UC). We used electronic health record (EHR) data to examine specialty addiction and psychiatry treatment initiation and engagement rates after referral.

Results

Among patients who screened positive for substance use and/or mental health problems and were referred to specialty addiction and/or psychiatry (n=333), those in the embedded-BHC arm had almost four times higher odds of initiating treatment than those in the pediatrician-only arm, OR=3.99, 95% CI=[1.99-8.00]. Compared to UC, those in the pediatrician-only arm had lower odds of treatment initiation (OR=0.53, 95% CI=[0.28-0.99]), while patients in the embedded-BHC arm had marginally higher odds (OR=1.83, 95% CI=[0.99-3.38]). Black patients and those with other/unknown race/ethnicity had lower odds of treatment initiation compared with white adolescents; there were no gender or age differences. We found no differences in treatment engagement across the three arms.

Conclusions

Embedded BHCs can have a significant positive impact on facilitating treatment initiation for pediatric primary care adolescents referred to addiction and/or psychiatry services.

Keywords: SBIRT, screening, substance use, adolescent, primary care, specialty treatment

1. Introduction

Substance use problems can negatively affect adolescents' physical and mental health, and can seriously disrupt developmental trajectories (Clingempeel, Henggeler, Pickrel, Brondino, & Randall, 2005; C. E. Grella, Hser, Joshi, & Rounds-Bryant, 2001; Mertens, Flisher, Fleming, & Weisner, 2007; S. Sterling & Weisner, 2005; Subramaniam & Volkow, 2014; Wu, Gersing, Burchett, Woody, & Blazer, 2011). For those with more severe problems or significant psychiatric comorbidity, specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment can be effective (Godley, Godley, Dennis, Funk, & Passetti, 2002; Godley, Godley, Dennis, Funk, & Passetti, 2007; Liddle, 2016), yet most patients who could benefit from specialty treatment do not receive it, even if they are referred. It is estimated that little more than a third of adolescents in need of specialty treatment for mental health or substance use problems actually start treatment (Merikangas et al., 2011). Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT), a public health approach to early identification and intervention for substance use problems, includes referral to specialty care for those whose problems warrant additional assessment and treatment. This intervention model is widely endorsed by pediatric medical organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (Committee On Substance Use and Prevention, 2016). Although referral to treatment is an essential component of SBIRT, most studies of brief interventions for adolescents have focused specifically on reducing alcohol and drug use (Harris et al., 2012), use initiation (Walton et al., 2014), or driving while intoxicated (Bernstein et al., 2010), with few studies focusing on specialty treatment initiation among patients who could benefit from such treatment (Glass et al., 2015). It is important to understand the most effective ways to provide effective referrals to specialty treatment, where emerging behavioral health problems can be addressed more thoroughly than in primary care.

Limited evidence suggests that SBIRT could positively impact specialty addiction and psychiatry treatment initiation. A randomized trial examined the effects of a brief intervention on Australian adolescents presenting in the emergency department for a substance use-related event. The intervention included a facilitated referral to specialty treatment consisting of a supportive counselor who helped patients identify and overcome barriers to treatment, made initial treatment appointments, made reminder calls, and assisted with transportation, as needed, compared to emergency department care as usual. Intervention-group participants were more likely to initiate addiction treatment, and those who initiated treatment experienced better substance use and emotional outcomes (based on a general psychological well-being instrument) than those who did not (Tait, Hulse, & Robertson, 2004). To our knowledge, no studies have examined the effectiveness of different approaches to delivering SBIRT in pediatric primary care in facilitating specialty treatment initiation and engagement.

This study examined the effectiveness of two modalities of delivering SBIRT in pediatric primary care (delivered by a pediatrician or by an embedded behavioral health clinician (BHC)) with usual care, and compared rates of initiation in specialty addiction and/or psychiatry treatment (“specialty treatment”) among patients referred for substance use and/or mental health problems. Differences between intervention arms were also examined. We examined both specialty addiction and psychiatry treatment because previous pilot experiences and anecdotal evidence from both patients and physicians suggested that many, if not most, patients and families find the prospect of entering addiction treatment less palatable than trying mental health treatment offered in psychiatry, due to stigma associated with addiction treatment. Similarly, in our pilot work we found that many teens initially endorse mental health distress, and only disclose substance use in the course of an in-depth assessment. (S. A. Sterling, Kline-Simon, Wibbelsman, Wong, & Weisner, 2012) Based on these findings combinbed with the fact that substance use and psychiatric problems are frequently comorbid, (Christine E. Grella, Joshi, & Hser, 2004; S. Sterling & Weisner, 2005; S. Sterling et al., 2003) we considered endorsement of either substance use or mood symptoms, or pediatricians' clinical judgment, as sufficient reason for SBIRT delivery. We hypothesized that patients in both intervention arms would have higher specialty treatment initiation rates than usual care, due to SBIRT training provided in the pediatrician-only arm, and to additional clinical resources available for SBIRT in the BHC arm. We also expected that patients in the BHC arm would have higher specialty treatment initiation rates than the pediatrician-only arm because BHCs typically have more knowledge of specialty services and have more time than pediatricians to facilitate referrals. Rates of treatment engagement across the arms were also examined. However, because specialty care engagement is likely affected by many additional factors outside of the primary care context, we did not have specific hypotheses about which arms would have higher engagement rates.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a non-profit integrated health care delivery system serving approximately 4 million members. Addiction and psychiatry treatment services are covered benefits and provided internally. The study examined patient data from an intent-to-treat, population-based sample of adolescent patients of primary care pediatricians, conducted from 11/1/2011–10/31/2013, in KPNC's Oakland Pediatrics Department, which treats a racially and socio-economically diverse population (S. Sterling et al., 2015).

All pediatricians in the clinic (n=52) were randomized using a blocked randomization to ensure an equal number of bilingual pediatricians to one of three study arms: 1) Pediatrician-only arm: Pediatricians trained to assess substance use and mental health problems using evidence-based screening tools, deliver brief interventions (BIs), and refer patients to specialty treatment; 2) Embedded-Behavioral Health Clinician arm: Pediatricians were trained to refer adolescents who endorsed substance use and/or mental health problems to an Embedded BHC who delivered brief interventions and referrals; and 3) UC: Care administered as usual (no SBIRT training or access to the BHC, but with access to screening tools and results in the electronic health record (EHR)). UC-arm pediatricians addressed patient-reported substance use or mental health symptoms per their usual practice, which might vary based on expertise, time, interest and clinical presentation. See Procedures section below for a description of the training and treatment approaches in the three study arms. Pediatrician assignment to study arm was not blinded. Pediatricians' patients aged 12-18 were eligible for the study, and there were no exclusion criteria. EHR data collected during pediatric visits were used to examine outcomes. Patients were not recruited to the study or informed of which study arm included their pediatrician, consistent with other comparative effectiveness studies (Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2007). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of KPNC and University of California, San Francisco.

2.2. Procedures

Pediatricians in both intervention arms were offered on-site trainings (three 60-minute sessions in the pediatrician-only arm, and one 60-minute session in the embedded-BHC arm) for which they received lunch and continuing education credit. In the pediatrician-only arm, 64% of pediatricians attended at least two trainings. In the embedded-BC arm, 75% of pediatricians attended the training. Pediatricians in both arms received supplemental recordings and slides, and research staff was available for technical assistance. Performance feedback and discussion of SBIRT techniques were provided at quarterly meetings. Trainings in the pediatrician-only arm covered: adolescent substance use and mental health prevalence, comorbidity and consequences; assessment; brief intervention strategies for substance use (e.g., Motivational Interviewing (MI) skills (Miller & Rollnick, 2013), decisional balance exercises, goal-setting) and depression (e.g., empathic listening, psychoeducation, problem-solving, behavioral activation, stress reduction, and exploration of challenges in interpersonal relationships) (Stein, Zitner, & Jensen, 2006); and protocols for referring patients to specialty addiction and psychiatry treatment. Pediatricians in the pediatrician-only and usual care arms, if they delivered SBIRT, incorporated all SBIRT components, including referral to specialty treatment services, into their regular clinical workflow and well-visit appointments times (typically 15-30 minutes). Pediatrician training in the embedded-BHC arm covered similar elements, but focused less on intervention delivery and more on how to assess severity and refer patients to the BHC. This training approach has been used in prior studies and has been associated with sufficient skill acquisition (Fallucco, Seago, Cuffe, Kraemer, & Wysocki, 2015). The BHC (N=1) was a licensed clinical psychologist who received 10 hours of MI-based SBIRT training, and had prior adolescent depression and substance use treatment experience. She provided brief cognitive behavioral therapy-based treatment and crisis management for substance and mood problems, and received weekly clinical supervision with the study intervention trainer, an experienced clinical psychologist. Pediatricians in the embedded-BHC arm were able to directly call the BHC, who was available during clinic hours, and could generally meet with patients immediately following their primary care appointment, or could schedule a future appointment if patients were unable to stay. In the embedded-BHC arm, the BHC provided patients with information regarding the KPNC psychiatry and addiction treatment programs. In the embedded-BHC arm, the BHC generally spent from 30 to 60 minutes on SBIRT activities, with potential additional follow-up phone interactions to facilitate referrals.

Because this was a pragmatic trial, to the extent possible we used the health system's indigenous screening and assessment tools. Per established clinic workflow in the health system, all adolescents presenting for well visits completed the Teen Well Check Questionnaire (TWCQ), a comprehensive health screening instrument created by health system clinical leaders and based on the Bright Futures (Simon et al., 2014) screening guidance. TWCQ responses are entered into the patient's EHR. The TWCQ includes items on past-year (Yes/No) alcohol, marijuana and other drug use, and recent depression symptoms (“During the past few weeks, have you OFTEN felt sad, down or hopeless?” and “Have you seriously thought about killing yourself, made a plan, or tried to kill yourself?”) which served as the initial substance use and mental health risk screening questions. Because of the pragmatic design of this trial, endorsement of any of these items, or pediatrician clinical judgment, triggered further assessment of substance use-related problems using the 6-item CRAFFT adolescent substance use problem screening instrument (Knight, Sherritt, Shrier, Harris, & Chang, 2002) (also already embedded in the EHR) and brief intervention or referral to specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment, as needed.

2.3. Measures and Data Sources

Pediatrician age, gender and years of experience, and patient age, sex and race/ethnicity (Asian, Black, Hispanic, White and other/missing), as well as specialty treatment utilization, were extracted from the EHR. Manual review of clinical notes identified referrals to specialty treatment within KPNC.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of specialty treatment initiation was calculated among patients referred to treatment, and was defined as having at least one visit to either a psychiatry or addiction program within 6 months of the respective referral. We used this relatively long time window because it is common for families to delay treatment entry. We examined both types of treatment as appropriate referral destinations for either substance use or mental health problems because our previous experience in this system suggests that families and pediatricians often prefer to have the adolescent initially obtain care in psychiatry over addiction treatment, regardless of their symptoms. Specialty treatment engagement was calculated among patients who were referred to and initiated treatment, and was defined as having at least two visits to the same type of treatment (addiction or psychiatry) within 30 days. This definition is consistent with the evidence-based substance use treatment engagement performance measure (National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), 2014).

2.4. Statistical methods

The primary outcome was initiation with specialty treatment. Models included only those who were referred to specialty treatment, rather than including all patients who endorsed substance use or mental health problems, many of whom had only mild symptoms and thus were not appropriate for referral. ANOVA and chi-square tests examined bivariate treatment arm differences between continuous and categorical patient characteristics, respectively. Generalized estimating equation techniques were used to fit multivariable logistic regression models to account for the fact that patients were nested within pediatricians and observations within these clusters may be correlated. Initial models included both provider and patient characteristics. Provider characteristics (gender, age and years of experience) did not differ across treatment arms and were not significant in the models, therefore only patient characteristics were included in the final models. Models examined differences in initiation and engagement to specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment across the 3 arms (UC [reference]) and between the two intervention arms only (pediatrician-only [reference]). Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc.); significance was defined at p<.05.

Power calculations accounted for intra-class correlation (ICC) among patients clustered within pediatricians (unit of randomization) which reduced effective sample size by a factor of 1+(n-1)*ICC, where n is the average cluster size.(M. K. Campbell, Mollison, Steen, Grimshaw, & Eccles, 2000) For the primary outcome of treatment initiation, our final sample size of 333 patients referred to treatment among 30 pediatricians with an ICC estimate of 0.02 provided adequate power (.83) to detect a medium effect size of 23-25% in treatment initiation.

3. Results

There were 1871 patients deemed eligible for further assessment based on endorsement of substance use or mental health problems on the screening questionnaire or pediatrician clinical judgment. Among these patients, 18% were referred to specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment. More females (61.3% vs. 54.6%, X2(1,N=1871)=5.00, p=0.025) and younger patients (M=15.6 SD=1.5vs. M=15.9 SD=1.5, t(1869)=3.75, p<.001) were referred to treatment; race/ethnicity did not differ between those referred and not. The embedded-BHC arm had fewer referrals (13.9%) than the pediatrician-only (21.6%) and usual care arms (18.5%, X2(2,N=1871)=13.02, p=0.002; not shown).

Patient Demographics

The embedded-BHC arm referred fewer Asian, and White patients and more Hispanic patients compared with the pediatrician-only and UC arms. Gender and age of patients referred did not differ across groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics by treatment arm among patients referred to treatment (n=333).

| Embedded-BHC | Pediatrician-only | UC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| (n=93) | (n=126) | (n=114) | p | ||||

|

| |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Male | 39 | 41.9 | 46 | 36.5 | 44 | 38.6 | 0.717 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Asian | 6 | 6.5 | 17 | 13.5 | 16 | 14.0 | 0.044 |

| Black | 32 | 34.4 | 46 | 36.5 | 37 | 32.5 | |

| Hispanic | 35 | 37.6 | 29 | 23.0 | 25 | 21.9 | |

| White | 10 | 10.8 | 26 | 20.6 | 28 | 24.6 | |

| Other/unknown | 10 | 10.8 | 8 | 6.4 | 8 | 7.0 | |

|

|

|||||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Age | 15.5 | 1.5 | 15.7 | 1.5 | 15.4 | 1.5 | 0.312 |

Note: BHC=behavioral health clinician; UC=usual care.

Specialty Addiction or Psychiatry Treatment Initiation

Among those referred, 27% initiated either addiction or psychiatry treatment. The pediatrician-only arm had lower odds of addiction or psychiatry treatment initiation compared with the UC arm, OR=0.53, 95% CI [0.28-0.99], while those in the embedded-BHC arm had higher odds of initiation than those in UC, although the difference only approached significance, OR=1.83, 95% CI [0.99-3.38] (Table 2a). Patients in the embedded-BHC arm had almost four times higher odds of initiating either addiction or psychiatry treatment than the pediatrician-only arm patients, OR=3.99, 95% CI [1.99-8.00] (Table 2b). Black patients had lower odds of addiction or psychiatry treatment initiation compared with White patients, OR=0.47, 95% CI [0.23, 0.95]; there were no gender or age differences (Table 2a). Both Black patients (OR=0.32, 95% CI [0.13, 0.81]) and those with other/unknown race/ethnicity (OR=0.12, 95% CI [0.02, 0.69]) had lower odds of initiation compared with whites in the intervention only model.

Table 2A. Initiation to specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment, among patients referred, across all arms (n=333).

| AOR | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Treatment arms (reference: UC) | ||||

| Embedded-BHC | 1.83 | 0.99 | 3.38 | 0.056 |

| Pediatrician-only | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.046 |

| Male (reference: female) | 0.82 | 0.48 | 1.38 | 0.446 |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.81 | 1.13 | 0.589 |

| Race/ethnicity (reference: White) | ||||

| Asian | 0.63 | 0.25 | 1.58 | 0.326 |

| Black | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.95 | 0.036 |

| Hispanic | 0.58 | 0.28 | 1.22 | 0.151 |

| Other/unknown | 0.45 | 0.14 | 1.43 | 0.175 |

Note: Initiation defined as at least one visit to either addiction or psychiatry treatment within 6 months of the respective referral; AOR=adjusted odds ratio; UC= usual care; BHC=behavioral health clinician

Table 2B. Initiation to specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment, among patients referred, in intervention arms only (n=219).

| AOR | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Embedded-BHC (reference: pediatrician-only) | 3.99 | 1.99 | 8.00 | <.001 |

| Male (reference: female) | 0.87 | 0.44 | 1.72 | 0.690 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.81 | 1.25 | 0.939 |

| Race/ethnicity (reference: White) | ||||

| Asian | 0.52 | 0.15 | 1.74 | 0.287 |

| Black | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.81 | 0.016 |

| Hispanic | 0.39 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 0.056 |

| Other/unknown | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.018 |

Note: Initiation defined as at least one visit to either addiction or psychiatry treatment within 6 months of the respective referral; AOR=adjusted odds ratio; BHC=behavioral health clinician

Specialty Addiction or Psychiatry Treatment Engagement

Among those who were referred and initiated specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment, 92% engaged in treatment. Due to power limitations only a bivariate comparison between the percent of patients who engaged in addiction or psychiatric treatment across arms was examined. No differences were found in treatment engagement across study arms: 95.2% pediatrician-only, 91.7% embedded-BHC, 90.6% UC, X2(2,N=89)=0.39, p=0.823 (not shown).

4. Discussion

The question of how effective referral to treatment (the “RT” in SBIRT) is for facilitating treatment initiation among patients whose substance use, or risk for use due to mental health problems, is serious enough to warrant specialty addiction or psychiatry services has rarely been examined in adolescents (Glass et al., 2015). The only study to our knowledge to examine the effects of referral to treatment among adolescents found that those receiving the intervention had higher rates of specialty treatment initiation than controls, however that study was based in an emergency department (Tait et al., 2004). We examined specialty treatment initiation and engagement rates among adolescents who received SBIRT delivered by pediatricians, an embedded BHC, or who received usual care. Results indicated that SBIRT can indeed be effective at increasing specialty treatment initiation, especially when delivered by a trained behavioral health clinician.

Initiation rates of addiction or psychiatry treatment were almost four times higher in the embedded-BHC arm, and twice as high in the UC arm, compared to the pediatrician-only arm. The low rates in the pediatrician-only arm maybe be due to patients feeling they received enough intervention services from their pediatrician, a known and trusted professional trained in brief intervention, that they preferred not to initiate specialty treatment, or they may have decided to schedule a return visit with their pediatrician for further discussion rather than initiating specialty treatment. The odds of treatment initiation in the embedded-BHC arm was also almost twice as high as in UC, though with only marginal statistical significance. This suggests that BHCs may be more effective than pediatricians in facilitating adolescent patient referrals to specialty treatment.

The embedded-BHC arm had fewer referrals to specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment than either the pediatrician-only or the UC arms (S. Sterling et al., 2015), which could be explained by BHCs having more time to address mild-to-moderate behavioral health problems in primary care, thus alleviating the need for referral to specialty treatment for those patients unless clinically indicated. The lower rates of treatment initiation among patients in the pediatrician-only arm may also reflect the relatively limited time and expertise with behavioral health and substance abuse among pediatricians compared to BHCs. With training in behavioral health and knowledge of health system and community mental health and substance abuse treatment resources, BHCs may have greater capacity to effectively facilitate treatment referrals. For patients with more severe problems, BHCs may have more knowledge of the appropriate clinical services, and more time to motivate patients and their families and help them navigate logistical and stigma-related barriers, e.g., helping to schedule and remind families of appointments, which may help facilitate treatment initiation. A BHC could be particularly advantageous in healthcare systems without integrated addiction and psychiatry services, in which access to treatment may be more challenging and pediatricians may be less familiar with specialty care services available in the community.

We found that Black adolescents and those of unknown race/ethnicity were less likely to initiate specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment compared to Whites. This adds to the literature suggesting that non-white ethnic groups are less likely to access needed specialty treatment even in integrated systems (C. I. Campbell, Weisner, & Sterling, 2006; Satre, Campbell, Gordon, & Weisner, 2010), which may be a result of heightened stigma around mental health and substance use problems and treatment in some communities (Alegria, Carson, Goncalves, & Keefe, 2011; Gary, 2005; Knifton et al., 2010; Mulvaney-Day, DeAngelo, Chen, Cook, & Alegria, 2012; Rose, Joe, & Lindsey, 2011). Providers or health systems adopting SBIRT should consider whether non-white patients need additional support and encouragement to access needed specialty treatment (Manuel et al., 2015), and whether access to a BHC trained in substance use and mental health problems based in pediatric primary care may better meet their needs and preferences. Specialty treatment programs may need to assess whether current programming, treatment approaches and staffing are equipped to appeal to and meet the linguistic and cultural needs of increasingly diverse patient populations, and may need to do more outreach to these patient populations (Alegria, Alvarez, Ishikawa, DiMarzio, & McPeck, 2016).

We found no differences in engagement rates in specialty addiction or psychiatry treatment across the three arms, all of which were over 90%. This is noteworthy, and suggests that once adolescents initiated treatment, patient and specialty treatment providers or milieu factors may have had more influence on retention than how they were referred there.

There are a number of limitations to this study. It was conducted in an integrated healthcare delivery system with an insured population in which adolescent patients' parents received insurance through employment, Medicaid, or individual health plans, and may not be generalizable to uninsured populations. KPNC has integrated psychiatry and addiction treatment programs and clinician practices, which may result in differences in treatment accessibility compared to other settings.

Because of the significant co-occurrence of substance use and mental health problems among adolescents, we opted to examine both substance use and mental health problems as an inclusive definition of substance use risk. This is consistent with current recommendations of SBIRT for the spectrum of risk, including “preventing or delaying the onset of substance use in lower-risk patients, discouraging ongoing use and reducing harm in intermediate-risk patients, and referring patients who have developed substance use disorders for potentially life-saving treatment”(Committee On Substance Use and Prevention, 2016). Consequently, adolescents were deemed eligible for further assessment if they endorsed either substance use or mental health problems, and we examined both specialty addiction and psychiatry treatment utilization. Thus, some of the patients did not explicitly endorse substance use problems, and some of the patients initiating treatment in psychiatry may not have been at risk for development of a substance use problem. This inclusive approach is also one which may be more acceptable and efficient for health systems if they are going to provide a BHC, helping to maximize the utility of these professionals in primary care settings.

It is possible that specialty treatment utilization was underestimated due to some patients seeking care outside of KPNC, which would not have been recorded in the EHR. However, since both psychiatry and addiction are covered benefits, we expect such outside utilization to have been minimal. Referral data also relied on the accuracy of provider documentation in the EHR, which likely varied both across pediatricians and between pediatricians and the BHC. This study contributes to the adolescent SBIRT literature by providing valuable information regarding the relative effectiveness of different approaches to SBIRT at facilitating treatment initiation among adolescents. Our findings suggest that SBIRT can be effective in helping patients initiate specialty treatment, but that pediatricians might benefit from the support of other clinicians with substance use and mental health assessment expertise. Health systems should consider the use of pediatric primary care-embedded BHCs as a way to serve more adolescent patients with mild to moderate behavioral health problems in primary care (S. Sterling et al., 2015), and to facilitate initiation in appropriate specialty treatment for those with more severe problems.

Figure 1.

Highlights.

Sample included teens reporting either substance use or mental health symptoms.

An embedded-BHC was effective at helping teens to initiate specialty treatment.

Pediatrician referrals were less effective at facilitating treatment initiation.

White youth referred to treatment were more likely to start than youth of color.

Acknowledgments

We thank Agatha Hinman for editorial assistance with the manuscript. We thank the KPNC Adolescent Chemical Dependency Coordinating Committee, the KPNC Adolescent Medicine Specialists Committee, Anna O. Wong, PhD, Patricia Castaneda-Davis, MD, Thekla Brumder, PsyD, and Jennifer Mertens, PhD, for their guidance. We also thank David Bacchus, MD, and all the physicians, medical assistants, nurses, receptionists, managers, and especially the patients and parents, of KPNC's Oakland Pediatrics clinic, for their participation in the activities related to this study.

Funding source: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA016204).

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov#NCT02408952

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alegria M, Alvarez K, Ishikawa RZ, DiMarzio K, McPeck S. Removing obstacles to eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in behavioral health care. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2016;35(6):991–999. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, Keefe K. Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, Heeren T, Edward E, Dorfman D, Bliss C, Winter M, Bernstein E. A brief motivational interview in a pediatric emergency department, plus 10-day telephone follow-up, increases attempts to quit drinking among youth and young adults who screen positive for problematic drinking. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17(8):890–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. doi:ACEM818[pii]10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CI, Weisner C, Sterling S. Adolescents entering chemical dependency treatment in private managed care: ethnic differences in treatment initiation and retention. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(4):343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Mollison J, Steen N, Grimshaw JM, Eccles M. Analysis of cluster randomized trials in primary care: a practical approach. Family Practice. 2000;17(2):192–196. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clingempeel WG, Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ, Randall J. Beyond treatment effects: Predicting emerging adult alcohol and marijuana use among substance-abusing delinquents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(4):540–552. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee On Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1210. http://dx.doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallucco EM, Seago RD, Cuffe SP, Kraemer DF, Wysocki T. Primary care provider training in screening, assessment, and treatment of adolescent depression. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(3):326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary FA. Stigma: barrier to mental health care among ethnic minorities. Issues in mental health nursing. 2005;26(10):979–999. doi: 10.1080/01612840500280638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1404–1415. doi: 10.1111/add.12950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk R, Passetti LL. Preliminary outcomes from the assertive continuing care experiment for adolescents discharged from residential treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00230-1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk RR, Passetti LL. The effect of assertive continuing care on continuing care linkage, adherence and abstinence following residential treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders. Addiction. 2007;102(1):81–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Hser YI, Joshi V, Rounds-Bryant J. Drug treatment outcomes for adolescents with comorbid mental and substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(6):384–392. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser YI. Effects of comorbidity on treatment processes and outcomes among adolescents in Drug Treatment Programs. Journal of child & adolescent substance abuse. 2004;13(4):13–31. doi: 10.1300/J029v13n04_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SK, Csemy L, Sherritt L, Starostova O, Van Hook S, Johnson J, et al. Knight JR. Computer-facilitated substance use screening and brief advice for teens in primary care: An international trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):1072–1082. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knifton L, Gervais M, Newbigging K, Mirza N, Quinn N, Wilson N, Hunkins-Hutchison E. Community conversation: addressing mental health stigma with ethnic minority communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(4):497–504. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(6):607–614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA. Multidimensional Family Therapy: Evidence Base for Transdiagnostic Treatment Outcomes, Change Mechanisms, and Implementation in Community Settings. Family process. 2016;55(3):558–576. doi: 10.1111/famp.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel JK, Satre DD, Tsoh J, Moreno-John G, Ramos JS, McCance-Katz EF, Satterfield JM. Adapting screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment for alcohol and drugs to culturally diverse clinical populations. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2015;9(5):343–351. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. Olfson M. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Flisher AJ, Fleming MF, Weisner CM. Medical conditions of adolescents in alcohol and drug treatment: comparison with matched controls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.021. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney-Day N, DeAngelo D, Chen CN, Cook BL, Alegria M. Unmet need for treatment for substance use disorders across race and ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125 Suppl 1:S44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) HEDIS Measures Included in the 2015 QRS Technical Specifications. 2014 Oct 1; Retrieved from http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/HEDISQM/Hedis2015/HEDIS%20QRS%202015%20Technical%20Update_Final.pdf.

- Rose T, Joe S, Lindsey M. Perceived stigma and depression among black adolescents in outpatient treatment. Children and youth services review. 2011;33(1):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Campbell CI, Gordon NP, Weisner C. Ethnic disparities in accessing treatment for depression and substance use disorders in an integrated health plan. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2010;40(1):57–76. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.1.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GR, Baker C, Barden GA, 3rd, Brown OW, Hardin A, Lessin HR, et al. Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule Workgroup. 2014 Recommendations for Pediatric Preventive Health Care. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):568–570. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RE, Zitner LE, Jensen PS. Interventions for adolescent depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):669–682. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling S, Kline-Simon AH, Satre DD, Jones A, Mertens J, Wong A, Weisner C. Implementation of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment for adolescents in pediatric primary care: A cluster randomized trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(11):e153145. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling S, Weisner C. Chemical dependency and psychiatric services for adolescents in private managed care: Implications for outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;25(5):801–809. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164373.89061.2c. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ALC.0000164373.89061.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling S, Weisner C, Lu Y, Mertens J, Kohn C, Hinman A. Paper presented at the Annual scientific meeting of the College of Problems of Drug Dependence. Bal Harbor, FL: 2003. Pathways, service use and outcomes for adolescents with substance abuse problems in private managed care. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling SA, Kline-Simon AH, Wibbelsman CJ, Wong AO, Weisner CM. Screening for adolescent alcohol and drug use in pediatric health-care settings: predictors and implications for practice and policy. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2012;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-13. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam GA, Volkow ND. Substance misuse among adolescents: to screen or not to screen? JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):798–799. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait RJ, Hulse GK, Robertson SI. Effectiveness of a brief-intervention and continuity of care in enhancing attendance for treatment by adolescent substance users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74(3):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MA, Resko S, Barry KL, Chermack ST, Zucker RA, Zimmerman MA, et al. Blow FC. A randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a brief cannabis universal prevention program among adolescents in primary care. Addiction. 2014;109(5):786–797. doi: 10.1111/add.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Gersing K, Burchett B, Woody GE, Blazer DG. Substance use disorders and comorbid Axis I and II psychiatric disorders among young psychiatric patients: findings from a large electronic health records database. Journal of psychiatric research. 2011;45(11):1453–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]