Abstract

B cell responses result in clonal expansion, and can occur in a variety of tissues. To define how B cell clones are distributed in the body, we sequenced 933,427 B cell clonal lineages and mapped them to 8 different anatomic compartments in 6 human organ donors. We show that large B cell clones partition into two broad networks—one spans the blood, bone marrow, spleen and lung, while the other is restricted to tissues within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (jejunum, ileum and colon). Notably, GI tract clones display extensive sharing of sequence variants among different portions of the tract and have higher frequencies of somatic hypermutation, suggesting extensive and serial rounds of clonal expansion and selection. Our findings provide an anatomic atlas of B cell clonal lineages, their properties and tissue connections. This resource serves as a foundation for studies of tissue-based immunity, including vaccine responses, infections, autoimmunity and cancer.

B cells are key players in the generation of protective immunity.1 During an immune response, B cells recognize antigen through their B cell receptors (antibodies) and can receive T cell help in specialized tissue-based structures termed germinal centers.2 The antibody genes in activated B cells can undergo somatic hypermutation (SHM), generating antibody sequence variants within lineages of clonally-related B cells.3,4 Activated B cells can become memory B cells or differentiate to become antibody-secreting plasma cells.5 Secreted antibodies contribute to the humoral immune response by neutralizing viruses and toxins, interacting with other immune cells via their constant regions and forming immune complexes that are processed by the reticuloendothelial system.6

B cells can combat infection locally, activating antigen-specific T cells and elaborating cytokines that influence nearby immune cells. The tissue distribution and trafficking of B cell clones influences how infections are controlled throughout the body. Animal studies indicate that tissue localization of B cells and plasma cells is important for protective immunity and homeostasis of bacterial microflora.7-9 However, unlike lab mice, humans are outbred, and live for decades in diverse environments with exposures to many different antigens and pathogens. Humans and mice also differ in the microanatomy of their tissues and in how their B cell subsets are defined.10,11 Tissue-based B cell subsets are not well understood in humans. Furthermore, most studies of human B cells have sampled the blood or tonsils. Consequently, how clones are localized to specific regions or tissues in the human body – as has been described for tissue resident T cells12,13 – is not known for B cells.

To understand how B cell clones are distributed in the human body, we performed next generation sequencing of antibody heavy chain gene rearrangements directly from the tissues. Because clonal lineages are somatically generated, the definition of clonal networks required the sampling and comparison of several different tissues from the same individual. Hence, VH rearrangements in 7 different tissues and blood were analyzed from 6 different human organ donors. After extensive sampling and clonal overlap analysis within the tissues, we identified the largest B cell clones that overlapped between the tissues. We mapped the tissue distribution of each large clone, creating an atlas of B cell clonal networks.

RESULTS

Sequencing pipeline and clone size thresholding

Using our resource of human tissues obtained from organ donors12-14, DNA was extracted from blood, bone marrow, spleen, lung, mesenteric lymph node, jejunum, ileum and colon. Donor information is provided in Table 1. Samples were amplified and sequenced at high depth from two donors (D207 and D181) and at lower depth in four additional donors (D145, D149, D168 and D182) for confirmatory analyses. As different B cell subsets differ in their antibody RNA transcript levels, are not fully defined in human tissues and vary in their ease of recovery in single cell suspensions from tissues, we extracted DNA from whole tissue samples.15 The analysis of DNA permitted efficient (one template per cell), large-scale, and agnostic sampling of all B cells. Antibody heavy chain gene rearrangements were amplified and sequenced (see Methods and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Rearranged heavy chain VH regions were used to distinguish clonally related B cells from each other by virtue of the highly diverse junction between the V (variable), D (diversity) and J (joining) gene sequences, which comprises the third complementarity determining region (CDR3).16,17

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the organ donors.

| Donor | Age | Sex | Race | Cause of Death | WBC final | HCV | CMV | EBV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D145 | 58 | M | White | CVA | 15.8 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| D149 | 55 | M | White | Anoxia | 12.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D168 | 56 | F | Hispanic | CVA | 2.6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| D181 | 46 | M | Black | CVA | 10.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D182 | 46 | M | Hispanic | CVA | 11.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| D207 | 23 | M | Hispanic | Head Trauma | 15.7 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Donor numbers are assigned by the Farber Lab. Age is in years. Cause of death is classified as cerebrovascular accident (CVA), head trauma or anoxia. WBC = white blood cell count in thousands per microliter. Serologic status (IgG) for Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein Barr Virus (EBV). 1=positive; 0=negative.

We defined clonally related B cells as sharing the same VH and JH gene groups18, having the same CDR3 length and exhibiting at least 85% CDR3 amino acid identity.19 This sequence similarity threshold was low enough to combine clonally related sequences with somatic mutations together, while being high enough to limit too many unrelated sequences from being incorrectly combined into the same lineage.19,20 The definition used for clone size thresholding was the sum of the number of unique sequence variants weighted by the number of instances of each unique sequence in independent PCR amplifications (see Methods for detailed calculations). This hybrid definition (“unique sequence instances”) affords some correction for differences in sequencing depth (which can influence unique sequence numbers), while not relying exclusively on resampling to establish clone size cut-offs. To assess the power of detection of clonal overlap, rarefaction analysis21 was performed on replicate sequencing libraries from each tissue (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Clones larger than 20 unique sequence instances (hereafter called C20 clones, see Methods) had at least a 75% chance of being resampled within most tissues (Supplementary Fig. 1b). D207 had 579,332 clones, of which 5,214 were C20 clones (see Methods and sequencing metadata in Table 2).

Table 2. Sequencing Metadata.

| Donor | Library | Total copies | Unique seq | Clones | C20 clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D145 | 54 | 2,439,338 | 143,573 | 67,342 | 400 |

| D149 | 45 | 1,456,188 | 79,933 | 12,183 | 501 |

| D168 | 50 | 1,224,202 | 68,537 | 23,810 | 356 |

| D181 | 111 | 8,077,742 | 567,444 | 225,950 | 1,074 |

| D182 | 51 | 1,302,469 | 80,741 | 24,810 | 375 |

| D207 | 257 | 23,583,180 | 1,418,182 | 579,332 | 5,214 |

Library indicates the number of sequencing libraries generated per donor. Total copies refers to the total number of valid IGH rearrangement sequences. Unique seq refers to the total number of unique in-frame sequences without a stop codon (productive rearrangements). Clones refers to the number of clonally related sequences, defined as having the same VH gene, the same CDR3 length and 85% sequence identity in the CDR3 (see Methods). C20 clones have at least 20 unique sequence instances (see text).

Clonal networks within and between tissues

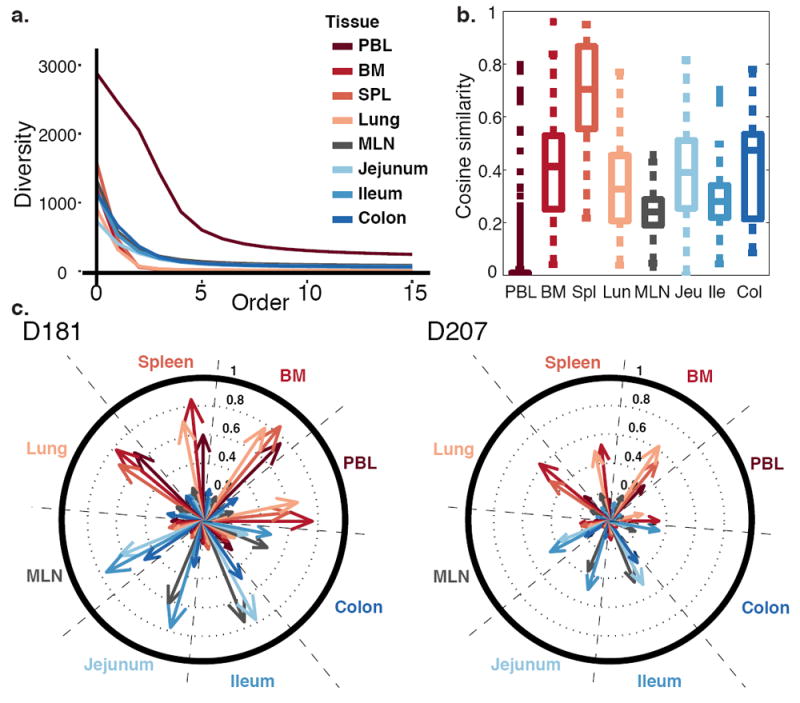

Tissues differed in the diversity of their C20 clones (Fig. 1a). Of the tissues analyzed, the spleen had the highest level of internal similarity and the blood had the lowest internal similarity in replicate sequencing libraries from each tissue (Fig. 1b). These findings are consistent with blood having the highest sampled diversity. The high diversity observed in the blood may be due to the fact that the blood undergoes extensive mixing, unlike the tissues. The internal similarity tissue map in D181 differed from D207, but became more similar to D207 when the largest clones were removed (Supplementary Fig. 2a). D181 was noteworthy for having a very large clone that comprised 15% of total sequence copies in the lung that was also detected in the spleen (~5%), bone marrow (~2.5%) and blood (~1%). This massive clone, (ID 183,264 of the ImmuneDB database; Methods and http://immunedb.com/tissue-atlas), had 218,000 copies in the entire body, including 4,265 unique sequence variants. In the blood, a clone of this size could be worrisome for malignancy or a pre-malignant condition such as monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis22. However, in the tissues, the levels of clonal expansion are not fully defined and may be influenced by regional localization of clones, including tissue resident cells, in the sampled tissue fragments.

Figure 1. Diversity, Similarity and Networks of Large Clones.

(a) Peripheral blood clones exhibit the highest sampled diversity. Diversity of clones with at least 20 unique sequence instances (C20 clones) is plotted at different orders (Hill numbers) in different tissues in D207. At an order of 0, the diversity is the number of different clones. At orders >1, diversity is influenced more by the most abundant clones. (b) Tissues exhibit higher internal similarity than blood. Box plots represent the distribution of cosine similarity between all pairs of sequencing libraries within a tissue (see Methods). Similarity is assessed for C20 clones in D207. Boxes represent the first and third quartiles bisected by the median. Whiskers represent the most extreme data excluding outliers, where outliers (dots) are data beyond the third or first quartile by a distance exceeding 1.5 times the inter-quartile interval. Higher cosine values correspond to greater sharing of large clones between replicate libraries from the same tissue. (c) Large clones form two major networks– one in blood-rich compartments (red tones) and one in the GI tract (blue tones). Shown are the cosine similarities of C20 clones between tissue pairs in D181 and D207. Each wedge within the circle represents a tissue. Each arrow represents the level of overlap (cosine similarity) in clones from other tissues to the clones in that wedge. Longer arrows indicate more overlap between the tissues. PBL = peripheral blood; BM = bone marrow; SPL = spleen; MLN = mesenteric lymph node.

Analysis of overlap between the tissues revealed two prominent networks of overlapping clones in both of the deeply sequenced donors (Fig. 1c). One network comprised the blood, bone marrow, lung and spleen and the other network consisted of the jejunum, ileum and colon. Clones in the mesenteric lymph node (MLN) spanned both the blood-rich sites and the GI tract, but exhibited greater overlap with the GI tract. When clones with sequences found in the blood were computationally removed, the network of overlapping clones within the blood-rich sites was more diminished than the GI tract network (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Regardless of the clone size definition used, blood and GI tract networks were observed (Supplementary Fig. 3). These data support the existence of two major networks of expanded B cell clones, one in blood-rich tissues and a separate network in the GI tract.

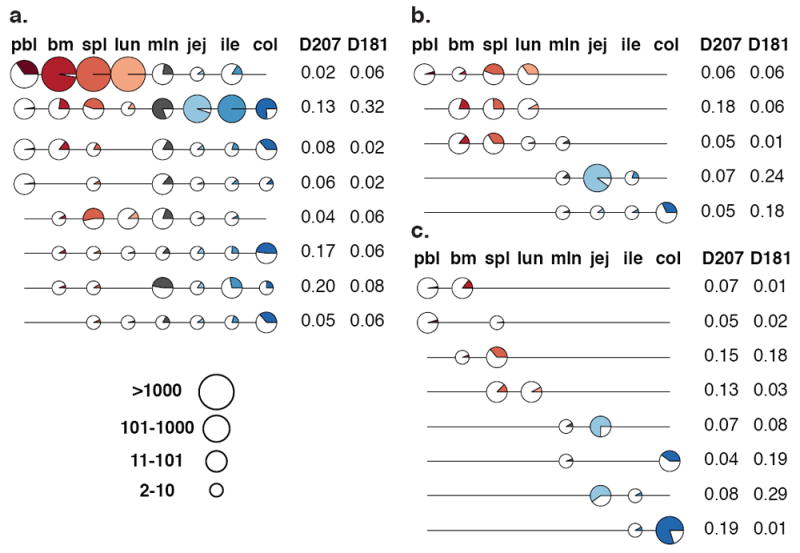

The preceding analysis focused on pairwise tissue comparisons. To evaluate the distribution of C20 clones across all of the tissues, C20 clones from D207 and D181 were classified into different tissue representation categories: global (found in 6-8 tissues), regional (3-5 tissues), two-tissue and single-tissue (Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Globally distributed clones tended to be the largest (Supplementary Fig. 4). Both the regional and two-tissue clones echoed the patterns of overlap observed in the paired tissue analysis: they were usually present in either the GI tract or the blood-rich tissues (Fig. 2). Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6 show all C20 clonal distribution patterns in D207 and D181, confirming the existence of two distinct networks inferred from the pairwise comparisons. Blood and GI tract networks across all of the tissues were observed at different clone size cut-offs (Supplementary Fig. 7a) and at two different stringencies of clone collapsing (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Furthermore, the analysis of networks revealed similar blood and GI tract networks in all six donors (Supplementary Fig. 8). As with the two-tissue comparisons, computational removal of the clones with peripheral blood sequences had a more profound influence on the blood-rich than the GI tract tissue clonal networks (Supplementary Fig. 9 and 10).

Figure 2. Tissue Distributions of Large Clones.

(a) Global (found in 6-8 tissues); (b) Regional (3-5 tissues) and (c) Two-Tissue C20 Clones. Each line is a clone. Each circle denotes membership of the clone in a particular tissue. The size of circle represents the total number of sequence instances the clones have in each tissue (depicted in legend). The portion of the circle that is colored represents the fraction of sequencing libraries from that tissue that contain at least one sequence of the clone (with at least two copies). The frequencies of each distribution type are indicated to the right of each clone line. Only the most frequent tissue distribution types (those that are present in at least 5% of a given tissue category in at least one of the two donors—D181 or D207) are shown. Tissues are colored as in Fig 1. lun = lung; jej = jejunum; col = colon; other abbreviations are as in Fig. 1.

Clonal lineage analysis

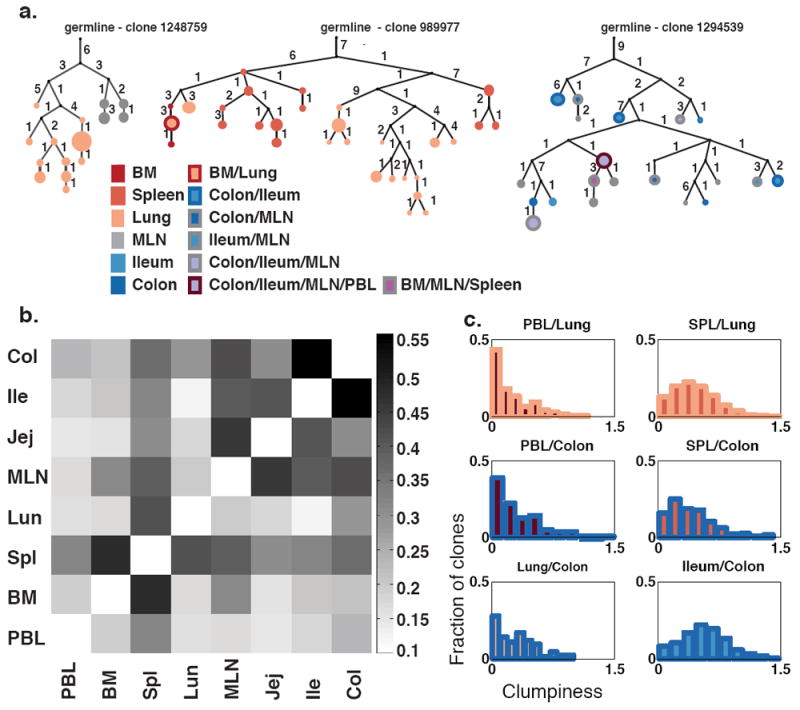

To gain further insight into how clones interconnected in different tissues, we performed clonal lineage analysis (see Methods and 23,24 for details on lineage construction). Clonal lineages tree structures are inferred by neighbor-joining based upon the different somatic mutations found in their unique sequence variants.23 Lineage trees can have trunks (consisting of somatic mutations that are shared amongst sequences) and branches and leaves (the latter consisting of mutations that are restricted to successively smaller subsets of the sequences in the tree). Clonally diversifying lineages within the blood-rich tissues have a branch structure in which the sequences from single tissues tend to all be located on single branches, as shown in Fig. 3a (left and center trees). In contrast, similar lineages in the GI tract have multiple tissues represented in each branch (Fig. 3a, right tree). Furthermore, the lineage tree nodes, which represent unique sequences, in such GI tract clones have contributions from multiple tissues (11 of 20 nodes in the right tree vs. 1 of 45 populated nodes in blood-rich trees, left and center). In order to quantitate the extent of dispersion of mutated clonal lineages throughout the different tissues, we calculated for each lineage with a specific combination of tissues the extent of sequence sharing in every pairwise combination of tissues (see25 and Methods). The level of sequence sharing we observed between different GI tract tissues was higher than between blood-rich tissues (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11).

Figure 3. Analysis of Sequence Variants in Clonal Lineages.

(a) Multi-tiered clonal lineages exhibit diversification and sharing of sequence variants within and between tissues. Trees are rooted in the closest germline VH gene allele in the IMGT database (see Methods). Numbers indicate somatic mutations. Circles are colored according to the tissue distribution of the sequence variants. Circle sizes are proportional to sequence copy numbers. Black dots indicate inferred nodes. Each clone is identified by an unique identifier number in http://immunedb.com/tissue-atlas. (b) GI tract tissue clones exhibit extensive sharing of sequence variants. The median of the distribution of clumpiness (a metric of sequence sharing within clonal lineages, see Methods) is shown for all two-tissues pairs across all C20 clones. (c) Sequence sharing distributions within clonal lineages that are found in different tissue pairs. Clones with peripheral blood (PBL) and another tissue were the least mixed, followed by clones mixing blood and GI tract tissues, then blood tissue clones and finally GI tract clones were the most mixed. SPL = spleen.

The presence of identical sequence variants within clones that reside in different parts of the GI tract, as seen in Fig. 3, implies local proliferation after somatic hypermutation.26 Furthermore, in the GI tract, the branching structures of clonal trees show participation of multiple tissue sites in the ongoing mutation and selection process. The fact that identically mutated sequences can often be found at multiple GI sites can be explained if mutated clones disseminate throughout the GI tract, yet also undergo serial rounds of mutation and selection. B cells in these clones are most likely taken up by regional lymphatics, enter the thoracic duct and eventually re-seed the GI tract via the blood.27,28

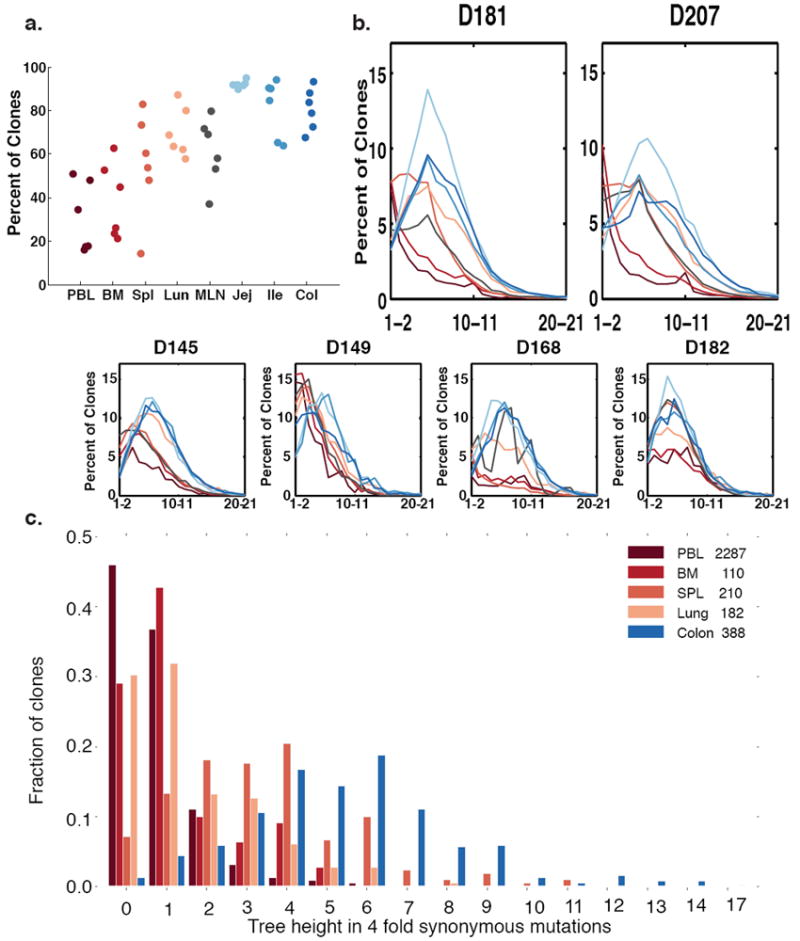

Sequence variation within lineages also provides information about antigen experience and the extent of clonal expansion.1,29,30 Clones with somatic VH region mutations were more frequent in the tissues than in the blood or bone marrow, suggesting that there are more memory B cells in the tissues (Fig. 4a), consistent with previous studies.31-33 Of note, we found that the jejunum has the highest fraction of somatically mutated clones in all of the donors (Fig. 4a). The jejunum also has many memory T cells13 and is a location where memory T cells accumulate in early life.12 Across all donors, GI tract B cell clones contained higher fractions of mutated clones and higher numbers of mutations per clone than B cells sampled in the other sites (Fig. 4b). GI tract clones also exhibited the highest accumulation of synonymous mutations from the nearest germline sequence, consistent with them having undergone the greatest number of divisions while the mutation process was engaged (Fig. 4c and Methods).34,35

Figure 4. Somatic Hypermutation in Different Tissues.

(a) Clones are more mutated in the tissues. Shown are percentages of clones that have average mutation frequencies of 1% or more. In all clones, only sequences from a specific tissue are counted (see Methods). Each column represents a separate tissue. Each dot represents an individual donor. (b) GI tract clones have right-shifted mutation frequency distributions compared to blood tissue clones in most donors. The average number of mutations per clone is plotted versus the percent of clones with that mutation level. Each line denotes a separate tissue. Segregation of mutations per clone to different tissues was accomplished as in Fig. 4a (see Methods). (c) Lineage tree heights of C20 single-tissue clones in different tissues of D207. Only tissues with >100 single tissue clones are shown. The tree height is defined as the maximum distance of a sequence in the clone from the germline when considering only 4-fold redundant synonymous mutations (see Methods).

DISCUSSION

Here we used deep immune repertoire profiling to construct an atlas that describes how expanded B cell clones distribute and develop within the human body. This resource data set is unique in two respects. First, the generation of these data could only be accomplished through the analysis of multiple samples from multiple tissues of multiple organ donors. Second, the computational analysis of clonal lineages, which relied upon a data set of over 568 sequencing libraries with over 38 million total IGH gene rearrangements, was at a substantially higher scale than previous work and required the development of data analysis and visualization tools. The atlas revealed two major networks of large clones, one in the blood, bone marrow, spleen and lung, and another in the GI tract. While some clones overlapped between the mucosal sites, the restriction of expanded clones in the GI tract was striking. Our analysis also revealed that the evolution of clonal lineages appeared to be distinctive in the GI tract, which contained large clones with the highest levels of somatic hypermutation.

The wide dissemination of some clones within the GI tract is consistent with earlier observations in mice and in humans.8,36 The distinctive clonal lineages in the GI tract and high levels of somatic hypermutation are consistent with antigen experience and clonal longevity, potentially due to chronic exposure to environmental antigens and gut microbiota. In mice bacterial microflora have been shown to play a role in clonal generation and localization37, however in humans at least some large IgA clones can persist in the colon despite antibiotic therapy.8 There may be different classes of endogenous and environmental antigens that periodically restimulate large, tissue resident B cell clones in humans. The patterns of clonal expansion we have described here also imply that there is a dynamic mechanism for mutating, expanding and periodically redistributing members of the same clone to different locations within the GI tract. Clones that overlap between the blood and one or more tissues, such as the colon, may be circulating subsets of B cells that home to specific tissues, as has been described for some IgA-expressing B cells in the blood that share antigenic specificities with clones in the human GI tract.38

The generation of this B cell clone tissue atlas required the development of data sharing, analysis and visualization tools. The raw sequencing data are shared via GenBank/SRA and can be downloaded for further analysis as described in Methods. The data can also be accessed and analyzed further using our framework for B cell repertoire analysis, ImmuneDB (https://immunedb.com/tissue-atlas).23 With ImmuneDB, we have created software applications for data analysis and visualization of high throughput immune repertoire profiling experiments. The applications are continuously updated and are available at http://immunedb.com and at https://github.com/DrexelSystemsImmunologyLab/ (see Methods for further details). This analysis pipeline permits modification of how clones are defined and how clone sizes are calculated. While these parameters and calculations are fundamental to all immune repertoire studies (see discussions in 19,39-41), they are often not explicitly tested when conclusions are drawn about clonal diversity or clonal overlap. Our analysis pipeline also is scalable to millions of DNA sequences and permits clone tracing across different tissues and samples. We also provide new data visualization tools, including “line circle” plots that can be used to view tissue distributions of clones by copy number and instance number across different sampling and re-sequencing depths and “clumpiness” to measure the degree of intermingling of sequence variants among different tissues within clonal lineages (see Methods and 24).

The tissue localization of large clones defined in this study, along with their VH and CDR3 sequence information, provide normative data for future studies of tissue-specific and response-specific motifs in antigen-driven immune responses. These data can also be used for general repertoire comparisons between health and disease, where “control” samples from tissues are rarely available. Even when antibody sequences are available from tissues in other data sets, they may not represent bona fide tissue-specific antibodies because the level of clonal overlap with other tissues or the blood is not known as it is with the large clones in this data set. In addition to providing data on tissue-based antibody repertoires, this atlas provides insights into which tissues have B cell clones that are most connected with the blood.

The analysis of somatic hypermutations within individual clonal lineages may contribute to a better understanding of how and in what order B cells traffic through tissues. For example, clones that originate in one tissue may migrate and accumulate additional somatic hypermutations in a different tissue. Clonal lineages can also be analyzed for B cell subset representation to gain further insights into ontogenic relationships between different tissue-based B cell subsets, with more closely related subsets sharing more clonal overlap or other repertoire features. Understanding the types of B cell subsets that reside in different tissues and how they move through the body could reveal new ways of tracking and targeting B cell clones. Furthermore, different selective pressures may be exerted upon large clones residing in or passing through different tissues. These differences in the immune environment will need to be further defined and taken into account as we monitor and attempt to manipulate tissue-specific immunity.

METHODS

Methods, including statements of data availability and any associated accession codes and references, are available in the online version of the paper.

Note: Any Supplementary Information, Source Data files and the Life Sciences Reporting Summary are available in the online version of this paper.

Study subjects

Tissue acquisition was coordinated through a research protocol and material transfer agreement with LiveOnNY (formerly the New York Organ Donor Network, NYODN). All tissues were obtained from research-consented, deceased (brain dead) organ donors at the time of clinical procurement for life-saving transplantation. All donors were free of cancer as well as Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and were HIV negative. The study was determined to be non-human subjects research by the Columbia University IRB, as tissue samples were obtained from deceased individuals. LiveOnNY transplant coordinators identified research-consented organ donors, and then coordinated tissue acquisition with the on-call surgeon for the project. Tissue collection occurred immediately after the donor organs were flushed with cold preservation solution and the clinical procurement process was completed. Once removed, tissue samples were placed in sterile specimen cups, submerged in cold saline, and brought to the laboratory and processed within approximately two to four hours of organ procurement.

Sample processing and DNA extraction

Tissues from organ donors were shipped overnight to the University of Pennsylvania. Cells were liberated from tissue fragments (approximately 1 cm3 in size) using physical methods (tissues were washed with PBS and cut into small pieces using razor blades) and placed in lysis buffer with proteinase K following the manufacturer’s directions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, Cat. No. 158667). DNA from peripheral blood and bone marrow were extracted using a Qiagen Gentra Puregene blood kit, following the manufacturer’s directions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, Cat. No. 158389). All blood and bone marrow samples were processed upon receipt. For D145 and D149, fresh tissue samples were processed when received. For donor D168, D181, D182 and D207, tissues were snap frozen and processed later for DNA extraction. DNA quality and yield were evaluated by spectroscopy (Nanodrop, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

VH rearrangement amplification

Immunoglobulin heavy chain family-specific PCRs were performed on genomic DNA samples. The libraries for sequencing used the Illumina MiSeq platform and were prepared using a cocktail of VH1, VH2, VH3, VH4, VH5, VH6 from framework region (FR)1 forward primers, and one consensus J region reverse primer modified from the BIOMED2 primer series.42 To capture the full-length VH region sequences, VH family leader primers were also used as described.43 Primer sequences and locations are provided in Supplementary Table 1 and the number of sequencing libraries prepared with the different primer mixes is given for each donor tissue combination in Supplementary Table 2. For the VH leader PCR, three separate amplification mixes were prepared for each sample: VH3 and VH3-21 primers (mix 1), VH4 and VH6 primers (mix 2), VH1, VH2 and VH5 primers (mix 3). In each 50μL mix with 1 unit of AmpliTaq gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), VH leader primers were used at a concentration of 0.6μM, genomic DNA at 200-400 ng (except for D168 MLN, which was hypocellular), 0.2 mM dNTPs and 1X PCR buffer with 1.5mM MgCl2. For the FR1 PCR, the VHFR1 and 3’ JH primers were used at 0.6 μM in a reaction volume of 50 μL using the same AmpliTaq Gold system. Valencia, CA). Amplification conditions for the leader PCR were primary denaturation followed by cycling at 95°C 30s, Ta (56°C for mix 1, 58°C for mix 2 and 60°C for mix 3) for 90s, extension at 72°C for 90s for 35 cycles, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes. Amplification conditions for FR1 PCR were primary denaturation, followed by cycling at 95°C 45s, 60°C for 45s, extension at 72°C for 90s for 35 cycles, and a final extension step at 72°C for 15 minutes.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Amplicons were purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP beads system (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) in a 1:1 ratio of beads to sample. Second round PCRs to generate the sequencing library were carried out using 2-4 μL of the first round PCR product and 2.5 μL each of NexteraXT Index Primer S5XX and N7XX primers, 0.325 μL KAPA in a reaction volume of 25 μL. Amplifications were carried out as recommended by the manufacturer (Illumina, San Diego, CA). To confirm adequacy of amplification, aliquots of both the 1st and the 2nd round PCR products were run on agarose gels. Library quality was evaluated using Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and quantified by Qubit Fluorometric Quantitation (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY). A sharp single band from Bioanalyzer analysis indicated a good quality library and was used for sequencing. The reading from Qubit using dsDNA HS (high sensitivity) assay kit (Cat. No. Q32851) was used to calculate the molarity of the library. Libraries were then loaded onto an Illumina MiSeq in the Human Immunology Core Facility at the University of Pennsylvania. 2×300 bp paired end kits were used for all experiments (Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3, 600-cycle, Illumina Inc., San Diego, Cat. No. MS-102-3003).

Filtering and germline gene association of raw sequence data

Raw sequence data (fastq files) were filtered based upon the positional Q score. A sliding window of 10 bases was used to run through all sequences. Any sequence with 10 bp section that had an average Q score lower than 20 was removed, along with any sequence that was shorter than 100 bases. R1 and R2 sequences were paired using pRESTO version 0.4.7.44 Sequences which were amplified by FR1 primers were trimmed after alignment to IMGT position 82, inclusive, to remove the primer sequence. In the composite R1+R2 read, any base with a Q score lower than 20 was replaced with an N and all sequences with more than 10 N’s were removed. Filtered sequences were aligned to their appropriate germline gene using the Anchor method.18 Then a sliding window of 30 nucleotides was used to flag insertion/deletions (indels). Any sequence with more than 18 mismatches in a sliding window was flagged as potentially having indels. These sequences were also removed.

Identification of unique sequences and association of sets of clonally related sequences

After V(D)J identification, duplicated sequences (those with identical nucleotide sequences) were collapsed in a two-level process. First, sequences were collapsed within each sample library into sets of unique sequences. Partial sequences were reconstructed into full length with their missing bases replaced by ‘N’. All duplicated sequences were collapsed to the longest sequence. Second, the numbers of different sequencing libraries that contained the same sequence were counted. Each time a sequence appeared at least one time in another library, it was counted as a separate “instance” of that sequence. Because DNA was sequenced, these instances represented separate B cells in which the same sequence was present. For each unique sequence, its total copy number and its number of instances were tracked for each tissue and overall in each donor. As PCR amplification and DNA sequencing are prone to error45, only sequences with more than one copy were considered for analysis. Next, unique sequences (copy >1) were parsed into clones (sets of B cells with sufficiently similar VH region rearrangements that they very likely share a common ancestry). Sequences were divided into bins with a common VH/JH gene and the same CDR3 length.18 Then, all of the sequences in the same bin from a given donor were grouped into clones based on their CDR3 amino acid similarity. Any two sequences within the same clone have CDR3 sequences that have 85% or higher amino acid identity.19 This process is order dependent, so sequences with the highest copy numbers in each bin were the first to be associated to a specific clone.

Clone size thresholding and rarefaction analysis

Even at the current level of high-depth sequencing, the true repertoire is being under-sampled. Sampling is particularly important for estimations of clonal overlap. Only clones with larger sizes will be sufficiently sampled to demonstrate overlap or lack of overlap. For this analysis, we considered clone size to be the sum of the number of uniquely mutated sequences and all the different instances of the same unique sequence that are found in separate sequencing libraries. In other words, we sum across all sequencing libraries the unique members of a clone that are found in each sequencing library. Thus, for instance, if a clone C1 were found in two sequencing libraries (L1 and L2) from spleen and had n unique sequences in L1 and m unique sequences in L2, we would say the clone size was n+m, even if all of the unique sequences in L2 were identical to those of L1. We refer to this hybrid clone size measure as “unique sequence instances.”

To estimate clone sizes for which sampling was sufficient, a sample-based rarefaction analysis was performed on clones of different sizes found in exactly two samples.21,46 This is a widely accepted method to estimate sufficient sampling in different fields of ecology and plant biology. The code written for diversity and rarefication analyses can be found at https://github.com/DrexelSystemsImmunologyLab/diversity and in references 47,48. Using these methods, we determined that the repertoire of clones with at least 20 unique sequence instances in a tissue were sufficiently large that we should be observing three quarters of their real population. For this reason, unless stated otherwise, we only considered in our analysis clones that had at least 20 unique sequence instances (C20 clones) in at least one tissue.

Measures of clonal overlap across samples and across tissues

To measure the amount of overlap between tissues, the cosine similarity was calculated for all combinations of two-tissue samples for the most heavily sequenced donors, D207 and D181. The cosine similarity is calculated as:

where Ai and Bi are components of vectors A and B, respectively. Each attribute in vector A or B represents the size of clone in sample 1 (for example, colon from D207) and sample 2 (for example, spleen from D207), respectively.

To quantify overlap within a tissue, the clone size was defined as the number of unique sequences in each sequencing library from that tissue. Thus the size of clone C in each sequencing library Li from a given tissue, was calculated as S(CLi)= ULi, where ULi is the number of unique sequences of clone C in sequencing library Li.

To quantify overlap between tissues, clone size was defined as the sum of the number of sequencing libraries in which at least one unique sequence variant of the clone occurred for each sequence variant within each tissue. In other words, the size of clone C in a given tissue was calculated S(Ctissue)= ktissue, where ktissue is the number of sequencing libraries of a given tissue in which clone C is found.

To characterize the interconnections of clones between more than two tissues, sequence alignment and clone assembly were first processed by MiXCR (version 1.7).49 To compare the distribution of overlapping clones across all tissues, the TrackClonotypes function of VDJtools (version 1.0.7)50 was used with the default settings. MiXCR was used to concatenate all of the FR1 and leader sequencing libraries for each tissue within each donor. The analysis was performed with different clone size cut-offs, including 0.01% (the default), 0.005% and 0.001% of total copies within at least one tissue (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The clone size cut-off is expressed as a percentage of total copies in a given tissue from a single donor.

Construction of B cell clonal lineages

Lineage trees of clonally related sequences (clonal lineages) were made based on their mutations using clearcut v1.0.9 with traditional neighbor joining and deterministic joining.24 To reduce the contribution of sequencing errors, when calculating clumpiness (see section on Sequence sharing across tissues, Methods), we considered only mutations that occurred in at least two sequences in a donor. Lineage nodes could thus include multiple unique sequences a single mutation apart and their multiple sample instances.

Sequence sharing across tissues measured by clumpiness within clonal lineages

Clumpiness is a measure of the tendency of two label types to be close on a given hierarchical structure.25 In the lineage tree of a clone that spans two or more tissues, a higher clumpiness value indicates that members of the clone exhibit more intermingling (mixing and overlapping of sequence variants) in the different tissues. In this case, we assessed the clumpiness of tissue types that annotated the mutant B cell receptor lineages. The clumpiness of clonal lineages was calculated by applying the clumpiness measure to each tissue and pairs of tissues on a B cell lineage tree. Clumpiness measures the clumping of groups of leaves, so the lineages were transformed in such a way that any intermediate vertex containing a compartment label became an unlabeled vertex with an additional edge connecting a leaf with the compartment label. For the analysis in Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 11, we considered all C20 clones in D207. Some sequences / nodes are themselves observed in multiple tissues. However, in most cases the relationship was lopsided, with one tissue being highly dominant. We therefore assigned a tissue to each node by the tissue of the majority of sequence instances found at that position in the lineage. The code written for the analysis of clumpiness can be found at https://github.com/DrexelSystemsImmunologyLab/find-clumpiness and is described in 25.

Mutation analysis

We calculated the average mutation frequency of each clone in each tissue. All instances of each unique sequence within a clone (across multiple sequencing libraries from a given tissue) were compared to their assigned germline VH gene. For Figs. 4a and 4b, the mutation frequency was calculated as the number of mismatched nucleotides divided by total number of nucleotides to the end of V gene until three mismatches were found in CDR3. The mutation frequency of clone in a given tissue was calculated as the average of mutation frequency of all sequences in that clone that belonged to that tissue. To assess clonal division during somatic mutation, we counted the maximal number of synonymous mutations from the germline observed in each clone. Only synonymous mutations in amino acids that are encoded with 4 codons were considered; such “four-fold silent” codons encode the same amino acid with any nucleotide in the third position, hence mutations in the third position of these codons should be neutral to selection.

Significance testing

In all cases non-parametric statistical tests were used to compare distributions and the necessary assumptions for these tests were met. The Kurskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance was used to show that sets of distributions differed. The Mann Whitney test was used to compare between individual distributions.

Data Availability and Accession Code Availability Statements

Raw data, including barcoding schema and sequencing run metadata are publicly available. QC filtered data in the form of fasta files that have undergone quality thresholding, paired read assembly and collapsing into unique sequences are available via SRA under accession number PRJNA343738. Analyzed data (VDJ assignment, clonal lineage assignment, somatic hypermutation selection analysis etc.) are available for viewing and download at (http://immunedb.com/tissue-atlas). A description of the immune database that was constructed for viewing these data is provided in http://immunedb.com 23. Listings of C20 clones in the two most highly sequenced donors are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 (D207) and 4 (D181).

Code Availability Statement

All code for antibody repertoire data analysis and visualization used in this manuscript is freely available without restriction at: https://github.com/DrexelSystemsImmunologyLab.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Human Immunology Core facility at the University Pennsylvania for assistance with cell preparations and sequencing support. We thank Y. Louzoun, M. Cancro and R. Thomas Jr. for discussions. We thank the organ donor families and the LiveOnNY transplant staff and coordinators. This work was supported by NIH P01 AI106697 (D.L.F., U.H., M.J.S., W.M., B.Z., A.M.R., D.R., D.J.C., N.M., T.G. and E.L.P.), P30-CA016520 (E.L.P.) and F31AG047003 (J.J.C.T.). G.W.S. was funded by the U.S. Department of Education Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) program, CFDA Number: 84.200.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: W.M. designed and performed experiments, developed methods, analyzed data, prepared figures and helped write the manuscript. B.Z., G.W.S. and A.M.R. developed methods for data analysis and visualization, analyzed data, prepared figures and helped revise the manuscript. D.R. performed experiments and helped revise the manuscript. J.J.C.T., D.J.C., N.M., H.L., A.L.F. and T.G. were involved in donor recruitment, organ recovery and helped revise the manuscript. D.L.F. directs the organ donor tissue resource for acquisition of tissues and helped write the manuscript. M.J.S. designed experiments, contributed ideas and helped write the manuscript. E.L.P. and U.H. planned the study. U.H. developed methods for data analysis and visualization, designed the data analysis and helped write the manuscript. E.L.P. designed experiments, contributed ideas to the data analysis, oversaw the overall study and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests Statement: None of the authors has any competing financial interests.

References

- 1.McKean D, et al. Generation of antibody diversity in the immune response of BALB/c mice to influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:3180–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berek C, Berger A, Apel M. Maturation of the immune response in germinal centers. Cell. 1991;67:1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90289-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigert MG, Cesari IM, Yonkovich SJ, Cohn M. Variability in the lambda light chain sequences of mouse antibody. Nature. 1970;228:1045–1047. doi: 10.1038/2281045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob J, Kelsoe G, Rajewsky K, Weiss U. Intraclonal generation of antibody mutants in germinal centres. Nature. 1991;354:389–392. doi: 10.1038/354389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nossal GJ, Lederberg J. Antibody production by single cells. Nature. 1958;181:1419–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder HW, Jr, Cavacini L. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroese FG, de Waard R, Bos NA. B-1 cells and their reactivity with the murine intestinal microflora. Semin Immunol. 1996;8:11–18. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindner C, et al. Diversification of memory B cells drives the continuous adaptation of secretory antibodies to gut microbiota. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:880–888. doi: 10.1038/ni.3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhee KJ, Sethupathi P, Driks A, Lanning DK, Knight KL. Role of commensal bacteria in development of gut-associated lymphoid tissues and preimmune antibody repertoire. J Immunol. 2004;172:1118–1124. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benitez A, et al. Differences in mouse and human nonmemory B cell pools. J Immunol. 2014;192:4610–4619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiniger BS. Human spleen microanatomy: why mice do not suffice. Immunology. 2015;145:334–346. doi: 10.1111/imm.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thome JJ, et al. Spatial map of human T cell compartmentalization and maintenance over decades of life. Cell. 2014;159:814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sathaliyawala T, et al. Distribution and compartmentalization of human circulating and tissue-resident memory T cell subsets. Immunity. 2013;38:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thome JJ, et al. Early-life compartmentalization of human T cell differentiation and regulatory function in mucosal and lymphoid tissues. Nat Med. 2016;22:72–77. doi: 10.1038/nm.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallangeon BD, Tyer C, Williams B, Lagoo AS. Improved detection of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by flow cytometric immunophenotyping-Effect of tissue disaggregation method. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2016;90:455–461. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakano H, Kurosawa Y, Weigert M, Tonegawa S. Identification and nucleotide sequence of a diversity DNA segment (D) of immunoglobulin heavy-chain genes. Nature. 1981;290:562–565. doi: 10.1038/290562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glanville J, et al. Precise determination of the diversity of a combinatorial antibody library gives insight into the human immunoglobulin repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20216–20221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909775106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang B, Meng W, Prak ET, Hershberg U. Discrimination of germline V genes at different sequencing lengths and mutational burdens: A new tool for identifying and evaluating the reliability of V gene assignment. J Immunol Methods. 2015;427:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershberg U, Luning Prak ET. The analysis of clonal expansions in normal and autoimmune B cell repertoires. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaari G, Kleinstein SH. Practical guidelines for B-cell receptor repertoire sequencing analysis. Genome Med. 2015;7:121. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heck KL, van Belle Gerald, Daniel Simberloff. Explicit calculation of the rarefaction diversity measurement and the determination of sufficient sample size. Ecology. 1975;56:1459–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldin LR, McMaster ML, Caporaso NE. Precursors to lymphoproliferative malignancies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:533–539. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenfeld AM, Meng W, Luning Prak ET, Hershberg U. ImmuneDB: A system for the analysis and exploration of high-throughput adaptive immune receptor sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2016 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheneman L, Evans J, Foster JA. Clearcut: a fast implementation of relaxed neighbor joining. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2823–2824. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz GW, Shokoufandeh A, Ontanon S, Hershberg U. Using a novel clumpiness measure to unite data with metadata: Finding common sequence patterns in immune receptor germline V genes. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2016;74:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2016.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuvaraj S, et al. Evidence for local expansion of IgA plasma cell precursors in human ileum. J Immunol. 2009;183:4871–4878. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gowans JL, Knight EJ. The Route of Re-Circulation of Lymphocytes in the Rat. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1964;159:257–282. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1964.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDermott MR, Bienenstock J. Evidence for a common mucosal immunologic system. I. Migration of B immunoblasts into intestinal, respiratory, and genital tissues. J Immunol. 1979;122:1892–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudikoff S, Pawlita M, Pumphrey J, Heller M. Somatic diversification of immunoglobulins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:2162–2166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sablitzky F, Wildner G, Rajewsky K. Somatic mutation and clonal expansion of B cells in an antigen-driven immune response. EMBO J. 1985;4:345–350. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briney BS, Willis JR, Finn JA, McKinney BA, Crowe JE., Jr Tissue-specific expressed antibody variable gene repertoires. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spencer J, Barone F, Dunn-Walters D. Generation of Immunoglobulin diversity in human gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunn-Walters DK, Isaacson PG, Spencer J. Sequence analysis of human IgVH genes indicates that ileal lamina propria plasma cells are derived from Peyer’s patches. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:463–467. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uduman M, et al. Detecting selection in immunoglobulin sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W499–504. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hershberg U, Uduman M, Shlomchik MJ, Kleinstein SH. Improved methods for detecting selection by mutation analysis of Ig V region sequences. Int Immunol. 2008;20:683–694. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holtmeier W, Hennemann A, Caspary WF. IgA and IgM V(H) repertoires in human colon: evidence for clonally expanded B cells that are widely disseminated. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1253–1266. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masahata K, et al. Generation of colonic IgA-secreting cells in the caecal patch. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3704. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkowska MA, et al. Circulating Human CD27-IgA+ Memory B Cells Recognize Bacteria with Polyreactive Igs. J Immunol. 2015;195:1417–1426. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan TA, et al. Accurate and predictive antibody repertoire profiling by molecular amplification fingerprinting. Sci Adv. 2016;2 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta NT, et al. Hierarchical Clustering Can Identify B Cell Clones with High Confidence in Ig Repertoire Sequencing Data. J Immunol. 2017;198:2489–2499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ralph DK, Matsen FA. Likelihood-Based Inference of B Cell Clonal Families. Plos Computational Biology. 2016;12:e1005086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Dongen JJ, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2003;17:2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng W, et al. Trials and Tribulations with VH Replacement. Front Immunol. 2014;5:10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vander Heiden JA, et al. pRESTO: a toolkit for processing high-throughput sequencing raw reads of lymphocyte receptor repertoires. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1930–1932. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schirmer M, et al. Insight into biases and sequencing errors for amplicon sequencing with the Illumina MiSeq platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colwell RK, Chao Anne, Gotelli Nicholas J, Lin Shang-Yi, Mao Chang Xuan, Chazdon Robin L, Longino John T. Models and estimators linking individual-based and sample based rarefaction, extrapolation and comparison of assemblages. Journal of Plant Ecology. 2012;5:3–21. doi: 10.1093/jpe/rtr044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwartz GW, Hershberg U. Germline Amino Acid Diversity in B Cell Receptors is a Good Predictor of Somatic Selection Pressures. Front Immunol. 2013;4:357. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz GW, Hershberg U. Conserved variation: identifying patterns of stability and variability in BCR and TCR V genes with different diversity and richness metrics. Physical biology. 2013;10:035005. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/10/3/035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bolotin DA, et al. MiXCR: software for comprehensive adaptive immunity profiling. Nat Methods. 2015;12:380–381. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shugay M, et al. VDJtools: Unifying Post-analysis of T Cell Receptor Repertoires. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data, including barcoding schema and sequencing run metadata are publicly available. QC filtered data in the form of fasta files that have undergone quality thresholding, paired read assembly and collapsing into unique sequences are available via SRA under accession number PRJNA343738. Analyzed data (VDJ assignment, clonal lineage assignment, somatic hypermutation selection analysis etc.) are available for viewing and download at (http://immunedb.com/tissue-atlas). A description of the immune database that was constructed for viewing these data is provided in http://immunedb.com 23. Listings of C20 clones in the two most highly sequenced donors are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 (D207) and 4 (D181).