Abstract

Inhibition of prostaglandin (PG) biosynthesis has been used to relieve pain for thousands of years. Today non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (which largely inhibit PG synthesis) are widely used to treat pain. Four main types of prostaglandins (PGD2, PGE2, PGF2 and PGI2) are synthesized from arachidonic acid during inflammation and have been demonstrated to impact nociception. PGE2 has been the most studied and utilized for its pain producing properties and has been demonstrated to increase hypersensitivity in rodent nociceptive behavioral models when applied centrally and/or peripherally. Surprisingly, there are no published reports that use withdrawal from radiant light beam (Hargreaves apparatus) to examine the dose response effect of peripherally applied PGE2 on thermal nociceptive hypersensitivity. To address this gap in the literature, we performed a dose response study examining the effect of PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity (assessed using a Hargreaves apparatus) where rats were injected with 0.003–30 μg of PGE2, intradermally into the hindpaw. Thermal hypersensitivity was assessed by measuring withdraw latency from a radiant light beam (Hargreaves test) and our primary objective was to determine the dose of PGE2 causing the most pronounced increase in thermal hypersensitivity (i.e. lowest withdraw latency). A secondary objective was to determine the minimum dose of PGE2 required to cause statistically significant decreases in thermal withdrawal latency as compared to rats injected with vehicle. We found that rats injected with the 30 μg dose of PGE2 exhibited the most pronounced thermal nociceptive hypersensitivity though secondary analysis showed that rats injected with PGE2 doses of 0.03–30 μg had lower withdrawal latencies as compared to rats injected with vehicle. This work fills an evidence gap and provides context to guide dose selection in future rodent pain behavior studies.

Introduction

Humans have been blocking the formation of prostaglandins to relieve pain since ancient Egyptian times (1). Though it was not until the discovery of salicylic acid as the active ingredient of willow bark (a popular natural pain remedy) and the more tolerable acetylsalicylic acid (Apirin) that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) became widespread (1). While NSAID (particularly aspirin) use spread throughout the 20th century the mechanism of action of such drugs was not known until the early 1970s when Vane discovered the anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties were due to inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis (2). Prostaglandins, particularly prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), have been subsequently demonstrated to have algesic properties and have been implicated in a number of acute and chronic pain disorders and rodent behavioral models (3–7).

Rodent behavioral testing for nociception generally focuses on thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia (8). While PGE2 has been demonstrated to affect both thermal and mechanical nociceptive sensitivity (9, 10) the majority of studies using PGE2 as a pain stimulus have evaluated mechanical pain only (9, 11, 12). Studying only one modality of PGE2 evoked nociception is problematic because previous reports have shown that the effect of PGE2 on thermal and mechanical sensitivity are not equivalent (13). Conventionally, thermal hypersensitivity is assessed using the tail flick test, hot plate test or Hargreaves test (also known as plantar test) (8). Of these tests the Hargreaves test has been the most cited (14) and is best suited for assessing unilateral hindpaw (i.e. local) allodynia (2, 15). Importantly, dose response studies that have investigated the effect of PGE2 on thermal nociceptive hypersensitivity have not utilized conventional methods for assessing this type of nociception (16, 17). To address this gap, and to guide future use of PGE2 in pain models, we performed a dose response study evaluating the effect of PGE2 injected intradermal (i.d.) on thermal nociceptive hypersensitivity, as measured by latency to withdraw from a radiant light beam (Hargreaves test). Our primary objectives were to determine (1) the dose of PGE2 that caused the most pronounced increase in thermal hypersensitivity; and (2) the minimum dose of PGE2 required to cause a statistically significant decrease in thermal withdrawal latency.

Materials and Methods

Experimental compound and vehicle

PGE2 was ordered from Cayman Chemical (14010 – Ann Arbor, MI – 99% pure, confirmed by LC-MS/MS) dissolved in ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and stored under N2 at −80 °C. Vehicle was 1% ethanol (by volume) in sterile saline (APP pharmaceuticals, IL) and prepared fresh the week of animal testing.

Animals

Male, Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River, USA) arrived at our facility at 10–12 weeks of age. Animals were immediately housed two to three per cage and kept on an inverted light/dark cycle (lights turn off at 9 am) and given ad libitum access to food and water. Animals were housed in our facility for 5 days before beginning a one week habituation period. During habituation animals were transferred, in their home cages, to the testing room and allowed to habituate to the room for at least 20 min. Animals were then transferred to 10 × 20 cm Perspex testing boxes (2 sides opaque, boxes arranged so animals were unable to see each other) which were placed on a glass surface heated to 30 °C of the Hargreaves testing device (IITC Life Science, model 400). Animals were kept in the boxes, on the device for 20–30 min while the radiant light stimulus of the device was periodically moved into the box in order to habituate animals to both the testing conditions and radiant light stimulus. Radiant light stimulus was not applied to the animals prior to the testing day and each animal was habituated in their testing box a minimum of 4 times. Experiments were in accordance with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders Animal Care and Use Committee and the International Association for the Study of Pain guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals.

Preparation and injection of PGE2

PGE2 (30, 3, 0.3, 0.03, 0.003 or 0 μg) was aliquoted into amber GC vials containing glass inserts (Agilent Technologies) and solvent (ethanol) was immediately evaporated under N2 at 30–37 °C. Once an aliquot was completely dried it was reconstituted in 5 μL of vehicle (described above), mixed by vortex and centrifuged (6,200 rpm – Micro One, Tomy) for approximately 10s. All aliquots were stored on ice for the duration of the experiment. Previous work in our laboratory found a sample size of at least 4 was sufficient to find a statistically significant decrease in thermal withdrawal latency with a 30 μg dose of PGE2 as compared to vehicle. We chose to at least triple our previously sufficient sample size to maximize our power to detect smaller changes that we expected with the lower doses of PGE2. Sample sizes were 12 (30, 3 and 0.03 μg), 13 (0.003 μg) and 17 (vehicle) rats for each respective dose.

We chose to inject PGE2 i.d. as previous reports found this route to be most effective at eliciting PGE2 evoked hypersensitivity (9) and rats were anesthetized to facilitate precise i.d. delivery of the injectate. Plantar surface of the hindpaw of anesthetized rats were disinfected with alcohol wipes and injected, i.d, with 1, 5 μL aliquot of PGE2 or vehicle using a sterilized Hamilton Microliter syringe (#701 – 10 μL capacity, USA). i.d. injections were carried out by guiding the needle sub-dermally to a spot in the middle of the plantar surface of the hindpaw and then inserting the sharp needle into the dermis and injecting. I.d. injections were confirmed by the appearance of a wheal at the site of injection and the needle was removed from the paw slowly and carefully to prevent any backwash of injectate. The dose each animal received was chosen at random by the blinded examiner. After injection, animals were immediately transferred to testing boxes and allowed to recover from anesthesia. After experimentation, PGE2 integrity was checked by TLC (Analtech Silica Gel GF 250um Thin Layer Chromatography glass plates; visualized with UV fluorescence quenching at 254nm and sulfuric acid charring, mobile phase 70/30/1 ethyl acetate/hexane/acetic acid, Rf=0.3) to confirm integrity of injected compounds.

Thermal hypersensitivity testing

Thermal hypersensitivity was assessed within 30 mins of an animal being injected using the method of Pitcher et al 2017 (18, 19). Briefly, latency to withdrawal from a radiant light beam was measured using a Plantar Test device (IITC Life Science) with a glass surface, heated to 30 °C. Rats were placed in testing boxes (described above) and latency to withdraw from a radiant light beam that was directed at the plantar surface of the hindpaw (in the area where PGE2 was injected) was recorded. A minimum of 2 withdraw latencies were recorded on both injected and non-injected paws, except for in one rat which after one stimulus would not place its injected paw on the glass. Average latency was calculated for each paw and reported here as average latency per paw or proportional average latency of injected paw to non-injected paw. All habituation and testing was done during the animals wake cycle (between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m.), in dark (red light) conditions. In all cases bedding in animals home cage was changed 2 days prior to testing. Withdraw was assessed by 2 investigators (AD and BW) and considered a response if the rat: 1) lifted its stimulated paw off the glass without otherwise changing body position, or 2) moved or changed body position and looked down at the spot where the stimulus was applied, or 3) moved or changed body position and displayed nociceptive behavior (shaking or licking of paw or refusal to bear weight on paw). The device operator was blinded throughout. Animals were tested in random order so that the dose of PGE2 did not affect the testing order of the animals.

Statistics

Our a priori aims were to perform a dose response of PGE2 injected into the hindpaw of rats and determine (1) dose of PGE2 that caused the most pronounced increase in thermal hypersensitivity; and (2) the minimum dose of PGE2 required to cause a statistically significant decrease in thermal withdrawal latency. Therefore, all results were compared using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism 7) where average latency for each dose of PGE2 was compared to average latency of all other groups. Additionally, to determine if each dose of PGE2 causes a significant change in thermal hypersensitivity as compared to vehicle, a secondary analysis we performed using Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons, comparing the average withdrawal latency of each PGE2 injected group with the average withdrawal latency of the vehicle injected group. In both analyses, a difference was considered statistically significant if the multiplicity adjusted p <0.05.

Results

PGE2 purity

Using PGE2 stock following injections, only one spot corresponding to PGE2 was visualized by TLC, confirming the integrity of our stock solution.

Qualitative observations

In general, a 5 μL i.d. PGE2 injection did not produce any noticeable hindpaw swelling or nocifensive behaviors in rats. Only one animal that received the highest dose of PGE2 (30 μg/paw) showed significant spontaneous nocifensive behaviors such as refusal to bear weight and paw licking. In fact, after one radiant light stimulus this animal completely refused to bear weight on its injected paw which prevented us from obtaining a second latency measure on that paw.

Thermal hypersensitivity

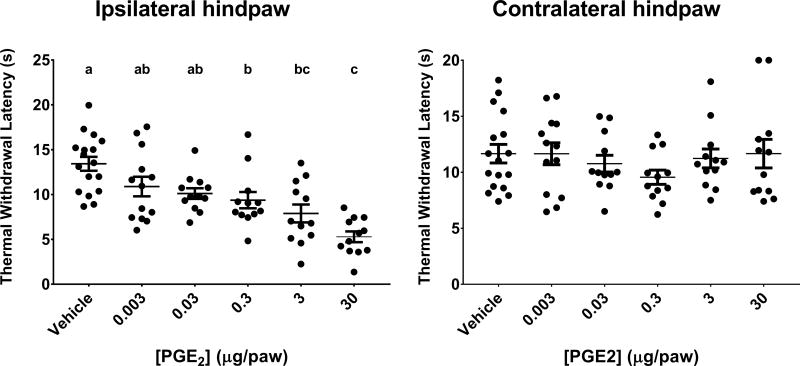

Figure 1 illustrates the effect of 0.003–30 μg of PGE2 injected i.d. into rat hindpaw on thermal withdrawal latency. A PGE2 dose of 30 μg produced the most pronounced effects on pain with mean withdraw latency of 5.3 ± 0.6 s as compared to 13.4 ± 0.7 s for rats injected with vehicle. 0.3 and 3 μg of PGE2 induced decreases in withdraw latency that were significantly different from vehicle injection but not significantly different from the other doses of PGE2 (9.4 ± 0.9 and 7.9 ± 1.0 s for 0.3 and 3 μg PGE2, respectively). The other PGE2 doses (0.003 and 0.03 μg) produced changes in withdraw latency that did not differ from one another. However, upon secondary analysis comparing the effect of each dose on thermal withdraw latency to vehicle using Dunnett’s test for multiple comparison, all but the lowest dose (0.003 μg) of PGE2 caused significant decreases in withdraw latency (10.89 ± 1.1 and 10.1 ± 0.6s for 0.003 and 0.03 μg PGE2 respectively, p<0.05). Contralateral hindpaw withdraw latencies were not significantly different for any PGE2 dose compared to vehicle (Figure 1 right panel).

Figure 1. Thermal withdrawal latencies (s) in rats injected with differing doses of PGE2.

Ipsilateral (left panel) and contralateral (right panel) hindpaw. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters signify means are significantly different from each other as determined by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (multiplicity adjusted p<0. 05). N=17 (vehicle), 13 (0.003 μg) and 12 (all other groups).

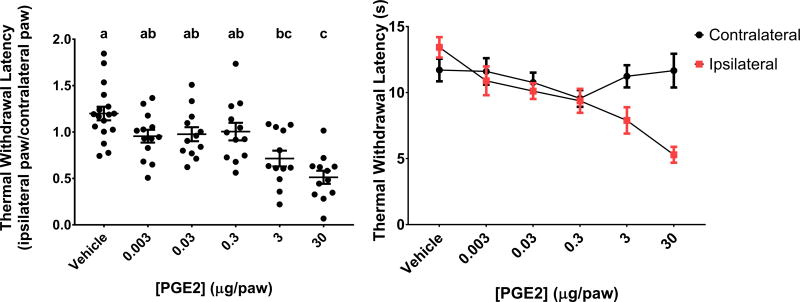

The relative latency to withdraw (ipsilateral/contralateral hindpaw) for animals injected with 30 μg PGE2 was 0.5 ± 0.7, which was significantly different than rats injected with vehicle 1.2 ± 0.07 (Figure 2 left panel). The relative withdraw latency in animals injected with 30 μg PGE2 was also significantly lower than in animals injected with 0.003, 0.03 and 0.3 μg (0.95 ± 0.07, 0.98 ± 0.08, 1.0 ± 0.09, respectively). Injection of 3 μg PGE2 decreased the relative withdraw latency as compared to vehicle (0.7 ± 0.08) but was not different compared to any other PGE2 dose. Upon secondary analysis, only the 30 and 3 μg doses significantly reduced relative withdraw latencies as compared to vehicle.

Figure 2. Relative thermal withdrawal latencies in rats after dose response injections of PGE2.

Ipsilateral hindpaw withdrawal latency as a proportion of contralateral hindpaw withdrawal latency (left panel) and combined withdrawal latencies (s) for both ipsilateral and contralateral hindpaws (right panel). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters signify means are statistically significant from each other as determined by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (multiplicity adjusted p<0.05). N=17 (vehicle), 13 (0.003 μg) and 12 (all other groups).

Discussion

Here we investigated the dose response effects of PGE2 injected i.d. into the hindpaw of rats on latency to withdraw from a radiant light beam. We found that doses of PGE2 ranging from 0.03 to 30 μg decrease withdrawal latencies compared to vehicle, indicating that PGE2 at doses above 0.03 μg increase thermal hypersentivity. Notably, the most pronounced effects were observed after injecting 30 μg, a dose much higher than often reported in rats and mice (9, 17, 20, 21). Therefore, previous reports using PGE2 to evoke hyperalgesia or sensitivity may be using suboptimal doses. For example, a recent report failed to detect thermal hypersensitivity 1 hour after injection of 0.35 μg PGE2 using the radiant light stimulus method similar to that used here (16). We observed that this dosage of PGE2 caused only minor decreases in thermal withdraw latencies which were likely not detected due to the time duration between injection and testing, as effects of PGE2 have previously been shown to diminish by 1 hour post injection (17). It should be noted, however, that, a dose of 0.1 μg PGE2 injected intraplantar has been reported to be maximally effective in mice, although dose response data from that study were not reported (21).

A previously reported dose-response study investigating the effects of i.d.. PGE2 on mechanical hypersensitivity in rats found that PGE2 effects reached a plateau at a dose of 0.1–1 μg/paw (9). This is in contrast with our finding that the effects of PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity increased up to a dose of 30 μg/paw. It has previously been reported that different types of pain are differentially affected by PGE2 (13). Specifically, the effect of PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity has been demonstrated to be less potent than the effect on mechanical sensitivity (13). Therefore, the lack of concordance between our work and the previously published PGE2 dose responses can likely be explained by the differences in testing modality. Another PGE2 dose-response study in rats evaluated the effects of 0.1 and 1 μg intraplantar PGE2 using 2 methods for thermal sensitivity (17). This report failed to detect changes in latencies to withdraw from radiant heat, however, it should be noted that these authors measured radiant heat withdrawal in restrained animals which has previously been shown to induce analgesia (22–24).

It is widely accepted that prostaglandins are synthesized on demand from unesterified arachidonic acid via the cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX 1 or COX2) followed by specific prostaglandin synthases (e.g. prostaglandin e synthase 2 for PGE2 synthesis) (2, 25). The primary site of prostaglandin action is not agreed upon, however, PGE2 has been shown to cause nociception via both central and peripheral mechanisms (26–30). In the periphery, PGE2 binds its receptors on sensory neurons where it is thought to increase responsiveness of ion channels, thereby facilitating the firing of these pain sensing neurons (31, 32). PGE2 can also be synthesized in the central nervous system in response to peripheral inflammation, and to induce phosphorylation of glycinergic receptors in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (30, 33). Glycinergic receptors are involved in inhibitory neurotransmission which is inhibited by PGE2 induced glycinergic receptor phosphorylation (34). Therefore, in the central nervous system, PGE2 can cause pain by decreasing inhibition induced by descending glycinergic inhibitory neurons in the spinal cord.

An interesting observation was that we were able to detect a significant decrease (relative to vehicle) in ipsilateral hindpaw withdraw latency in rats injected with 0.3 μg PGE2, even though relative withdraw latency (ipsilateral/contralateral) did not differ between these rats. Similarly, PGE2 doses as low as 0.03 μg significantly decreased in ipsilateral hindpaw withdrawal latencies without affecting relative withdrawal latency. It is possible that the current study was not adequately powered to detect the small differences in relative withdraw latency produced by low doses of PGE2. Alternatively, the observed differences in ipsilateral paw withdraw latencies could be chance findings. The possibility of these findings being due to chance is especially likely for the 0.03 μg dose of PGE2, which was only different from vehicle in a secondary analysis, with less conservative corrections for multiple comparisons. Moreover, in a hindpaw withdraw test relative withdraw latencies are likely more meaningful as they account for variances between animals and provide an estimate of the proportional change in hypersensitivity. It has previously been reported that i.d. PGE2 hindpaw injections do not evoke hypersensitivity on the contralateral hindpaw (17) and although PGE2 can act centrally (30) it is unlikely that our 5 μL injection spread to the CNS, especially since all testing was finished within an hour of each injection.

To our knowledge, this is the first report measuring withdraw from a radiant light stimulus to determine the dose-response effect of i.d. PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity. This study has a number of strengths in the experimental design and testing parameters. Firstly, animals were injected i.d. as opposed to subcutaneous or intraplantar. It has been shown previously that PGE2 is most effective at causing hypersensitivity when injected i.d. (9). Additionally, PGE2 purity was assessed using TLC, to ensure our stock solutions did not degrade throughout the experiment. While we were able to confirm that our stock solutions did not degrade, it should be noted that we were unable to assess the purity of the injectate, and therefore, we were unable to determine if handling of the injectate or an interaction between PGE2 and vehicle promoted PGE2 degradation. However, this is unlikely as PGE2 purity was checked by LC-MS/MS prior to injection, and TLC analysis indicated no compound degradation. This study was also designed such that behavioral testing was performed in the dark during the rat’s subjective night. Rats are nocturnal animals, and therefore, performing neurological testing during their subjective night, when the animal is awake and alert, may be better than testing during their subjective day. It is worth noting, however, that it is often difficult to distinguish a rat’s response to a hindpaw stimulus from normal movement, especially when the animal is awake and active. Therefore, we used strict criteria when determining if movements constituted a response to the thermal stimulus (described above). It is possible, however, that by using these strict criteria we missed subtle responses and biased our testing towards longer latencies which were more painful to the animal. However, this bias is likely to be evenly distributed since injections and testing were done by blinded investigators.

Here for the first time we performed a dose-response study on the effects of i.d. injected PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity in rats, using a widely utilized testing method (14, 19). We found that the PGE2 doses commonly administered produce suboptimal thermal hypersensitivity in rats. Moreover, we found that doses necessary to evoke significant thermal hypersensitivity in rats are higher than doses previously reported to evoke maximal mechanical hypersensitivity, indicating that the effect of PGE2 on different pain modalities is not equivocal. In conclusion, this report on the dose response effect of PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity will serve as a guide for future work using PGE2 to evoke pain responses in rats.

Highlights.

Prostaglandins are the most researched lipid mediators involved in pain and inflammation

PGE2 is the main prostaglandin studied in inflammatory pain though there are no dose response studies measuring the effect of PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity using standard techniques

We measured the effect of different doses of PGE2 on thermal hypersensitivity using withdraw latency from radiant light beam (standard technique) as our assessment tool

Maximally effective PGE2 dose was 10–100 times higher than doses used in literature

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National institute on Aging, and the National Center for Complimentary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health..

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jack DB. One hundred years of aspirin. Lancet. 1997;350(9075):437–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat New Biol. 1971;231(25):232–5. doi: 10.1038/newbio231232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willis AL, Cornelsen M. Repeated injection of prostaglandin E2 in rat paws induces chronic swelling and a marked decrease in pain threshold. Prostaglandins. 1973;3(3):353–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(73)90073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncada S, Ferreira SH, Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis as the mechanism of analgesia of aspirin-like drugs in the dog knee joint. Eur J Pharmacol. 1975;31(2):250–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(75)90047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juan H. Prostaglandins as modulators of pain. Gen Pharmacol. 1978;9(6):403–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(78)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira SH. Prostaglandins, aspirin-like drugs and analgesia. Nat New Biol. 1972;240(102):200–3. doi: 10.1038/newbio240200a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandasamy R, Price TJ. The pharmacology of nociceptor priming. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;227:15–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-46450-2_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrot M. Tests and models of nociception and pain in rodents. Neuroscience. 2012;211:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khasar SG, Green PG, Levine JD. Comparison of intradermal and subcutaneous hyperalgesic effects of inflammatory mediators in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1993;153(2):215–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90325-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Negus SS, Butelman ER, Al Y, Woods JH. Prostaglandin E2-induced thermal hyperalgesia and its reversal by morphine in the warm-water tail-withdrawal procedure in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266(3):1355–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tillu DV, Hassler SN, Burgos-Vega CC, Quinn TL, Sorge RE, Dussor G, Boitano S, Vagner J, Price TJ. Protease-activated receptor 2 activation is sufficient to induce the transition to a chronic pain state. Pain. 2015;156(5):859–67. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taiwo YO, Goetzl EJ, Levine JD. Hyperalgesia onset latency suggests a hierarchy of action. Brain Res. 1987;423(1–2):333–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90858-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turnbach ME, Spraggins DS, Randich A. Spinal administration of prostaglandin E(2) or prostaglandin F(2alpha) primarily produces mechanical hyperalgesia that is mediated by nociceptive specific spinal dorsal horn neurons. Pain. 2002;97(1–2):33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terajima K, Aneman A. Citation classics in anaesthesia and pain journals: a literature review in the era of the internet. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47(6):655–63. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero-Reyes M, Ye Y. Pearls and pitfalls in experimental in vivo models of headache: conscious behavioral research. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(8):566–76. doi: 10.1177/0333102412472557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bastos LC, Tonussi CR. PGE(2)-induced lasting nociception to heat: evidences for a selective involvement of A-delta fibres in the hyperpathic component of hyperalgesia. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(2):113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menendez L, Lastra A, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A. Unilateral hot plate test: a simple and sensitive method for detecting central and peripheral hyperalgesia in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;113(1):91–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitcher MH, Tarum F, Rauf IZ, Low LA, Bushnell C. Modest Amounts of Voluntary Exercise Reduce Pain- and Stress-Related Outcomes in a Rat Model of Persistent Hind Limb Inflammation. J Pain. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32(1):77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aley KO, Messing RO, Mochly-Rosen D, Levine JD. Chronic hypersensitivity for inflammatory nociceptor sensitization mediated by the epsilon isozyme of protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2000;20(12):4680–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04680.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malmberg AB, Brandon EP, Idzerda RL, Liu H, McKnight GS, Basbaum AI. Diminished inflammation and nociceptive pain with preservation of neuropathic pain in mice with a targeted mutation of the type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci. 1997;17(19):7462–70. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07462.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler RK, Finn DP. Stress-induced analgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;88(3):184–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calcagnetti DJ, Stafinsky JL, Crisp T. A single restraint stress exposure potentiates analgesia induced by intrathecally administered DAGO. Brain Res. 1992;592(1–2):305–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91689-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa A, Smeraldi A, Tassorelli C, Greco R, Nappi G. Effects of acute and chronic restraint stress on nitroglycerin-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;383(1–2):7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vane JR, Botting RM. The mechanism of action of aspirin. Thromb Res. 2003;110(5–6):255–8. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bromm B, Rundshagen I, Scharein E. Central analgesic effects of acetylsalicylic acid in healthy men. Arzneimittelforschung. 1991;41(11):1123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim RK, Guzman F, Rodgers DW, Goto K, Braun C, Dickerson GD, Engle RJ. Site of Action of Narcotic and Non-Narcotic Analgesics Determined by Blocking Bradykinin-Evoked Visceral Pain. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1964;152:25–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira SH. Peripheral analgesia: mechanism of the analgesic action of aspirin-like drugs and opiate-antagonists. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;10(Suppl 2):237S–45S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira SH, Lorenzetti BB, Correa FM. Central and peripheral antialgesic action of aspirin-like drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978;53(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taiwo YO, Levine JD. Prostaglandins inhibit endogenous pain control mechanisms by blocking transmission at spinal noradrenergic synapses. J Neurosci. 1988;8(4):1346–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01346.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.England S, Bevan S, Docherty RJ. PGE2 modulates the tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium current in neonatal rat dorsal root ganglion neurones via the cyclic AMP-protein kinase A cascade. J Physiol. 1996;495(Pt 2):429–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson S, Copits BA, Zhang J, Page G, Ghetti A, Gereau RWt. Human sensory neurons: Membrane properties and sensitization by inflammatory mediators. Pain. 2014;155(9):1861–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harvey RJ, Depner UB, Wassle H, Ahmadi S, Heindl C, Reinold H, Smart TG, Harvey K, Schutz B, Abo-Salem OM, et al. GlyR alpha3: an essential target for spinal PGE2-mediated inflammatory pain sensitization. Science. 2004;304(5672):884–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1094925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betz H, Laube B. Glycine receptors: recent insights into their structural organization and functional diversity. Journal of neurochemistry. 2006;97(6):1600–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]