Summary

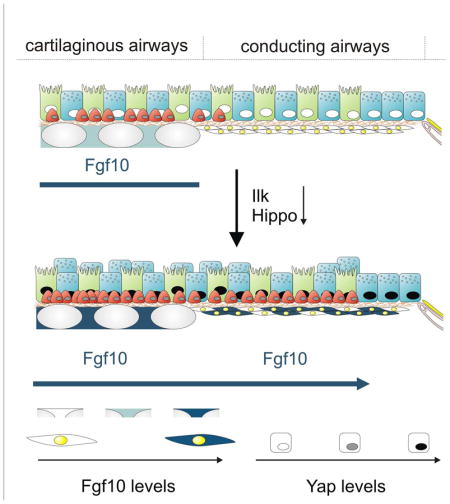

The lung harbors its basal stem/progenitor cells (BSCs) in the protected environment of the cartilaginous airways. After major lung injuries, BSCs are activated and recruited to sites of injury. Here, we show that during homeostasis, BSCs in cartilaginous airways maintain their stem cell state by down-regulating the Hippo pathway (resulting in increased nuclear Yap), which generates a localized Fgf10 expressing stromal niche; in contrast, differentiated epithelial cells in non-cartilaginous airways maintain quiescence by activating the Hippo pathway and inhibiting Fgf10 expression in airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs). However, upon injury, surviving differentiated epithelial cells spread to maintain barrier function and recruit integrin linked kinase to adhesion sites, which leads to Merlin degradation, down-regulation of the Hippo pathway, nuclear Yap translocation and expression and secretion of Wnt7b. Epithelial-derived Wnt7b, then in turn, induces Fgf10 expression in ASMCs which extends the BSC niche to promote regeneration.

eTOC blurb

Volckaert et al. demonstrate a novel mode of stem cell regulation in which basal stem cells during homeostasis or differentiated airway epithelial cells after injury down-regulate their Hippo signaling to generate their own localized Fgf10-expressing stromal niche, which maintains or amplifies the stem/progenitor cell population via Fgf10-Fgfr2b signaling.

Introduction

Stem cells are required for tissue homeostasis and repair. They reside in a highly specialized stromal microenvironment called the stem cell niche (Scadden, 2006), where they are kept in a quiescent state during homeostasis or rapidly amplify upon tissue insults. Basal stem/progenitor cells (BSCs), located in the protected environment of the cartilaginous airways of the trachea and mainstem bronchi, were identified as progenitors of secretory or ciliated cells (Rock et al., 2009). Secretory cells represent transit-amplifying cells with the potential to self-renew or differentiate into post-mitotic ciliated daughter cells (Pardo-Saganta et al., 2015; Rawlins et al., 2009). Secretory cells drive almost the entire cell turnover in the conducting airways during homeostasis or repair of small injuries (Rawlins et al., 2009), and give rise to alveolar epithelial cells after major lung epithelial injuries (Barkauskas et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2014). Interestingly, after major lung epithelial injuries, BSCs emerge at sites of injury where they aid in restoring lung architecture (Kumar et al., 2011; Vaughan et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2015). How BSCs are maintained and restricted to cartilaginous airways during homeostasis, and how they are activated and recruited to sites of severe injury are not well understood.

The production and maintenance of BSCs during development depends on Fgf10 secreted by the stromal tissue located in between the cartilage rings (Volckaert et al., 2013b). Furthermore, overexpression of Fgf10 in all lung cells during late embryonic development induces the ectopic development of BSCs in conducting airways (Volckaert et al., 2013b), where they normally do not reside. Similarly, the maintenance of the adult BSC pool depends on Yap, the nuclear effector of the Hippo pathway, whereas overexpression of Yap in adult tracheal BSCs results in BSC hyperplasia and stratification (Tata et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). These findings indicate that lung stem/progenitor cells deploy Hippo signaling to maintain their stemness, and that Hippo signaling executes these tasks by controlling Fgf10-Fgfr2b signaling. It further suggests that BSCs are absent from non-cartilaginous conducting airways because airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) which envelop them, do not secrete Fgf10 during homeostasis (Volckaert et al., 2013b; Volckaert et al., 2011).

Interestingly, upon injury-induced loss of airway epithelial cells, surviving differentiated cells spread out to seal the wound and maintain barrier function, and secrete Wnt7b to induce ectopic Fgf10 expression in ASMCs (Volckaert et al., 2013a; Volckaert et al., 2011). This mesenchymal-derived Fgf10 then acts back on the airway epithelium to drive regeneration by expanding secretory transit amplifying cells and inhibiting their differentiation into ciliated cells (Volckaert et al., 2013b; Volckaert et al., 2011). Airway epithelial injury leads to the inactivation of the Hippo pathway in differentiated epithelial cells of the conducting airway (Lange et al., 2015), and genetic inactivation of the Hippo pathway or overexpressing Yap in secretory cells breaks their quiescence (Lange et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014).

In the present paper, we tested how the Hippo pathway regulates Fgf10 expression in stromal cell niches. We report the existence of a mode of stem cell regulation in which tracheal BSCs during homeostasis or differentiated cells after injury down-regulate their Hippo signaling (resulting in increased nuclear Yap) to generate their own localized Fgf10-expressing stromal niche, which maintains or amplifies the stem/progenitor cell population via Fgf10-Fgfr2b signaling. Mechanistically, we also show that surviving epithelial cells spread out after airway epithelial injury and recruit integrin-linked kinase (Ilk) to adhesion sites, which results in the destabilization of Merlin, an upstream activator of the Hippo pathway. An increase in nuclear Yap in surviving and spreading airway epithelial cells then leads to the expression and secretion of Wnt7b, which acts on the ASMCs to induce the release of Fgf10. Fgf10 subsequently activates Fgfr2b signaling on BSCs to drive their expansion, mobilization and/or differentiation. This intricate epithelial-mesenchymal reciprocal signaling pathway between stem/progenitor cells or differentiated cells and their niche cells ensures maintenance of stemness during homeostasis and promotes regeneration in response to injury.

Results

Tracheal basal stem/progenitor cells maintain and restrict their cell pool during homeostasis by generating a localized Fgf10-expressing stromal niche

Our previous studies have demonstrated that the development and maintenance of BSCs during embryogenesis depends on Fgf10 secreted by stromal cells in between cartilaginous rings of the upper airway (Volckaert et al., 2013b). To test whether the Fgf10-Fgfr2b signaling axis controls BSC amplification and maintenance in adult tracheas, we induced the expression of Fgf10 in adult Rosa26-rtTA;Tet-Fgf10 mice (hereafter, referred to as rtTa-Fgf10), or inactivated Fgfr2b in all adult airway epithelial cells using Sox2-CreERT2;Fgfr2bf/f or in BSC specifically using Krt5-CreERT2;Fgfr2bf/f mice (hereafter, referred to as Sox2-Fgfr2bf/f and K5-Fgfr2bf/f respectively). While overexpression of Fgf10 for 2 weeks caused a significant expansion of Keratin-5 (K5)- and p63-positive BSCs in the trachea, conditional deletion of Fgfr2b resulted in a depletion of BSCs (Fig. 1A–C, S1A,B). BSCs were lost both to differentiation (Fig. S1A) as well as apoptosis (Fig. S1C) due to the loss of Fgfr2b signaling within the basal cell compartment but not upon inactivation of Fgfr2b in secretory daughter cells using Scgb1a1-CreER;Fgfr2bf/f mice (Fig. S1D). These data, together with our previous findings during development (Volckaert et al., 2013b), indicate that Fgfr2b signaling is required for BSC maintenance during pre- and post-natal life.

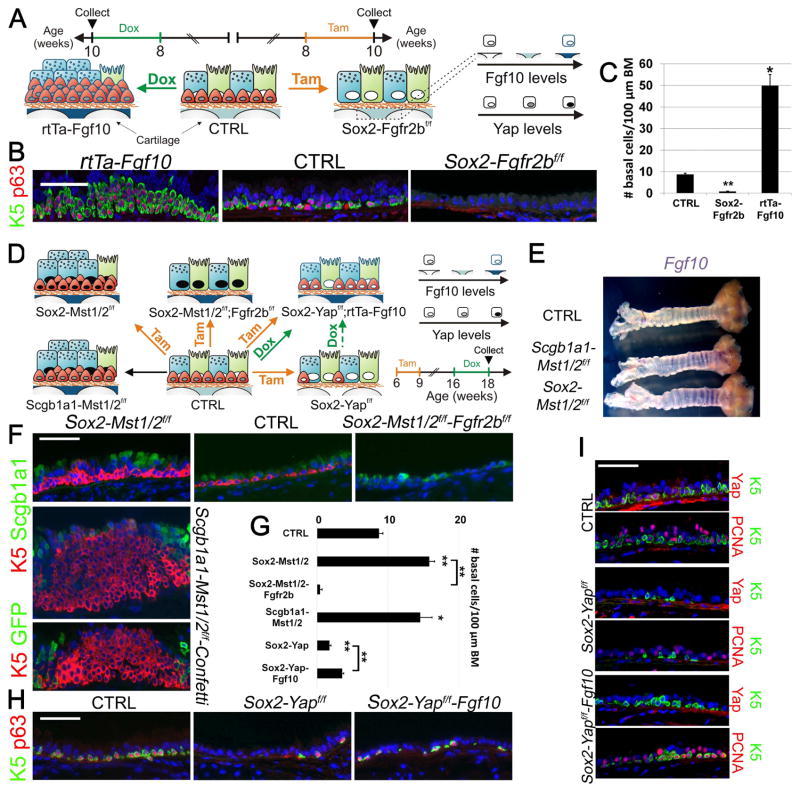

Figure 1. The inactive Hippo pathway in basal stem/progenitor cells generates the Fgf10-expressing tracheal stromal niche required to maintain their cell pool.

(A) Experimental strategy and schematic representation of tracheal BSC amplification after Fgf10 overexpression or tracheal BSC loss after Fgfr2b ablation in airway epithelial cells. Ciliated, secretory and BSCs are shown in green, blue and red, respectively.

(B) Immunostaining on rtTa-Fgf10, control and Sox2-Fgfr2bf/f tracheas for the BSC markers Keratin 5 (K5) (green) and p63 (red) 14 days after doxycycline or tamoxifen induction.

(C) Quantification of the number (#) of BSCs per 100 μm basement membrane of pictures represented in (B).

(D) Experimental strategy and schematic representation of Mst1/2 ablation in all airway epithelial cells or selectively in secretory/ciliated cells alone or in combination with either Fgfr2b or Yap in all airway epithelial cells with or without simultaneously inducing Fgf10 expression.

(E) Whole mount in situ hybridization for Fgf10 in control, Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f and Sox2-Mst1/2f/f tracheas. Note purple Fgf10 expression between the tracheal cartilage rings.

(F) Upper panels show immunostaining on control, Sox2-Mst1/2f/f and Sox2-Mst1/2f/f-Fgfr2bf/f tracheas 2 months after tamoxifen induction as well as on a 2.5 month old Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f-Confetti trachea for the BSC marker K5 (red) and the secretory cell marker Scgb1a1 (green). Lower panel shows immunostaining on Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f-Confetti trachea for the BSC marker K5 (red) and GFP (green).

(G) Quantification of the number (#) of BSCs per 100 μm basement membrane (BM) of pictures represented in (F,H).

(H) Immunostaining on control, Sox2-Yapf/f, Sox2-Yapf/f-rtTa-Fgf10 tracheas for the BSC markers K5 (green) and p63 (red) after tamoxifen-induced deletion of Yap and/or doxycycline-induced Fgf10 expression. Refer to panel D for experimental strategy.

(I) Immunostaining on adjacent tracheal sections from control, Sox2-Yapf/f and Sox2-Yapf/f-Fgf10 mice for BSC marker K5 (green) and Yap (red) or proliferation marker PCNA (red) 12 weeks after tamoxifen and 2 weeks after doxycycline induction, starting at 10 weeks after tamoxifen induction.

Nuclei, DAPI (blue). **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. n ≥ 6.; error bars mean ± SEM. Scale bars, 100 μm (B,F,H); 50 μm (I). (See also Figure S1)

It has been shown that inactivation of the Hippo pathway or overexpression of Yap, the transcriptional effector of the Hippo pathway, in secretory and/or tracheal BSCs drives their amplification. In addition, Yap ablation in BSCs results in their loss over a period of 12 weeks (Lange et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014), supporting the concept that lung stem/progenitor cells deploy Hippo signaling to control their fate. To test whether Hippo signaling executes this task by controlling Fgf10-Fgfr2b signaling, we disrupted the Mst1/2 genes, which results in the inactivation of the Hippo pathway and increased nuclear Yap. This was accomplished by either conditional deletion of Mst1/2 genes in all airway epithelial cells using Sox2-CreERT2;Mst1/2f/f mice, or only in secretory/ciliated daughter cells using Scgb1a1-Cre;Mst1/2f/f mice (referred to as Sox2-Mst1/2f/f and Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f, respectively) (Fig. 1D). These experiments revealed increased Fgf10 expression in the tracheal stromal niche (Fig. 1E, S1E,F), and amplification of the tracheal BSC population in both mouse strains (Fig. 1D,F,G). Lineage tracing using the Confetti allele in tracheas of Scgb1a1-Cre;Mst1/2f/f;Rosa26R-Confetti mice (hereafter, referred to as Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f-Confetti) indicated that the expansion of BSCs in Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f-Confetti tracheas was not caused by the dedifferentiation of secretory cells, but rather by amplification of existing BSCs (Fig. 1F). To test the hypothesis that this BSC expansion was due to the increase in stromal Fgf10 expression, we simultaneously deleted Mst1/2 and Fgfr2b in all tracheal epithelial cells using Sox2-CreERT2;Mst1/2f/f;Fgfr2bf/f mice (referred to as Sox2-Mst1/2f/f-Fgfr2bf/f), and found that BSCs failed to expand and were lost (Fig. 1D,F,G and S1C), indicating that the Hippo pathway in epithelial cells promotes BSC quiescence by repressing Fgf10 expression in a non-cell autonomous manner within the stromal niche. To further confirm this finding, we deleted Yap in all tracheal epithelial cells and simultaneously overexpressed Fgf10 by intercrossing Sox2-CreERT2;Yapf/f and rtTA-Fgf10 mice (referred to as Sox2-Yapf/f-rtTa-Fgf10) (Fig. 1D) or intercrossing Sox2-CreERT2;Yapf/f and Rosa26-LSL-rtTa;Tet-Fgf10 mice (referred to as Sox2-Yapf/f-rtTaf/f-Fgf10) (Fig. S1G). The Rosa26-LSL(Lox-STOP-Lox)-rtTA (referred to as rtTaf/f) cassette carries a loxP-flanked stop codon, which is removed in the presence of active Cre recombinase allowing for cell type-specific rtTa expression. Consistent with previous studies (Zhao et al., 2014), the majority of BSCs was lost 10–12 weeks after tamoxifen-induced ablation of Yap when Fgf10 expression was not induced (Fig. 1D,G–I). In sharp contrast, however, induction of Fgf10 expression after tamoxifen-induced Yap ablation, efficiently triggered BSC proliferation and halted further BSC loss (Fig. 1D,G–I), suggesting that epithelial Yap is critical for generating a localized Fgf10-expressing stromal niche. Indeed, inactivation of Yap in Sox2-CreERT2;Yapf/f mice resulted in decreased Fgf10 expression in the tracheal stromal niche (Fig.S1F,H).

Next we wanted to address how increased nuclear Yap induces Fgf10 expression in the tracheal stromal niche. Intriguingly, an interaction between Yap and p63 has been suggested to indirectly regulate basal stem cell proliferation and maintenance in squamous cell carcinoma by inducing Fgf10 expression in the adjacent stroma (Ramsey et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). Expression of Wnt7b, which is one of the main upstream regulators of Fgf10 expression in the lung, has been shown to be driven by p63 in other tissues (Trink et al., 2007). In the lung, Wnt7b expression is regulated in part by the transcription factors Foxa2, Nkx2.1 and Gata6 (Weidenfeld et al., 2002), and binding of Yap/Taz to Nkx2.1 increases its transcriptional activity (Park et al., 2004). Based on these observations we wondered if epithelial-derived Wnt7b could be downstream of the Hippo pathway to regulate Fgf10 expression in the stroma. As expected, we found increased epithelial Wnt7b expression in tracheas of Sox2-CreERT2;Mst1/2f/f and Scgb1a1-Cre;Mst1/2f/f mice, whereas Wnt7b was drastically reduced in Sox2-CreERT2;Yapf/f tracheal epithelium (Fig S1I). To determine if epithelial Wnt7b expression induces Fgf10 expression in the stroma, we generated Sox2-CreERT2;Wnt7bf/f mice and found a decrease in stromal Fgf10 expression compared to control tracheas (Fig. S1F) concomitant with a decrease in BSCs (Fig. S1J). Interestingly, conditionally ablating Wnt7b in secretory cells alone using Scgb1a1-Cre;Wnt7bf/f mice did not affect the BSC population (Fig. S1J), indicating that Wnt7b expressed by basal cells is required for their maintenance through the induction of Fgf10 in the adjacent mesenchyme.

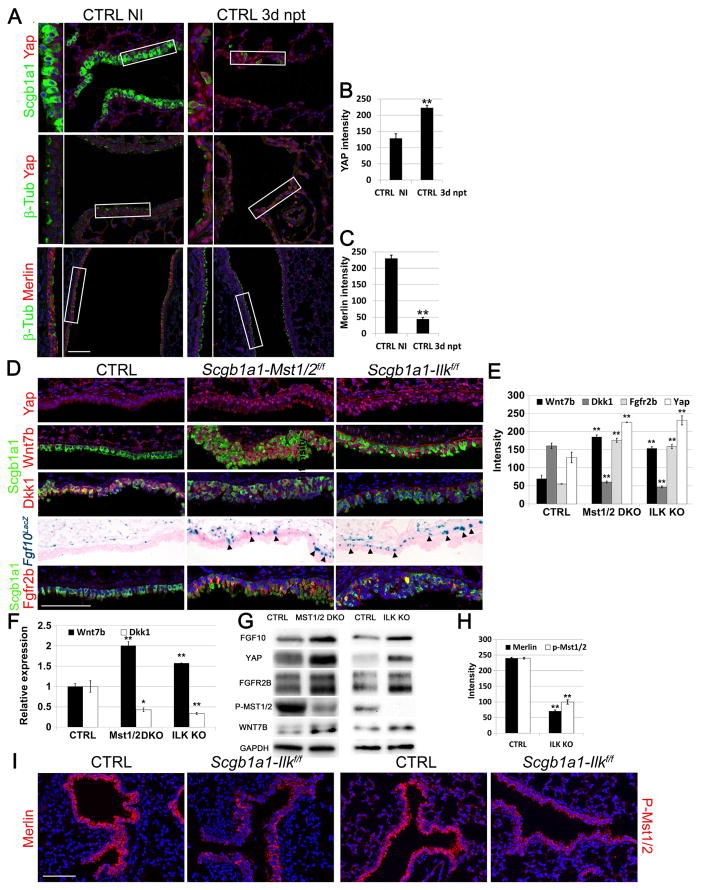

Inactivation of the Hippo pathway in differentiated airway epithelial cells in non-cartilaginous, conducting airways activates Fgf10 expression within the ASMC niche

We have previously shown that ASMCs provide a niche for secretory “transit amplifying” progenitor cells by releasing Fgf10 in response to Wnt7b secreted by airway epithelial cells that survive and spread after airway epithelial injury (Volckaert et al., 2011). We observed that naphthalene-mediated lung injury inactivates Hippo signaling (i.e. increased nuclear Yap translocation) in airway epithelial cells (Fig. 2A,B), suggesting that, similar to that observed in cartilaginous airways, the Hippo pathway may also control Fgf10 expression within the ASMC niche. To further establish that the Hippo pathway controls Fgf10 in the ASMC niche, we deleted Mst1/2 in secretory and ciliated cells using Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f mice and intercrossed the mice with an Fgf10LacZ reporter line to monitor Fgf10 expression. The efficient deletion of Mst1/2 (Fig. S2A) led to nuclear translocation of Yap in secretory cells (Fig. S2B), increased Wnt7b with decreased Dkk1 expression in secretory and ciliated cells, elevated Fgf10 expression in the ASMC niche and increased Fgfr2b expression in airway epithelial cells (Fig. 2D–G, S2A and S3A,B,D). To investigate whether the expansion of airway epithelial cells upon conditional Mst1/2 ablation is caused by the sustained secretion of Fgf10 by the ASMC niche, we simultaneously inactivated the Mst1/2 and Fgfr2b genes in all airway epithelial cells using Sox2-Mst1/2f/f-Fgfr2bf/f mice (Fig. S2). These studies revealed that, despite the accumulation of Yap in their nuclei (Fig. S2B), secretory cell hyperplasia did not occur (Fig. S2 and S4; Fig. S6C shows the specificity of the Sox2-CreERT2 line). This confirms that ASMC niche-derived Fgf10 is induced downstream of epithelial Yap and acts in a non-cell autonomous and paracrine manner on neighboring secretory cells.

Figure 2. Inactivation of the Hippo pathway in differentiated airway epithelial cells after injury or after Ilk inactivation induces epithelial Wnt7b expression and Fgf10 secretion by ASMCs.

(A) Immunostaining on non-cartilaginous airways of non-injured (NI) control lungs and lungs 3 days after naphthalene (npt)-induced injury for secretory cell marker Scgb1a1 (green) or ciliated cell marker β-tubulin (green) and Yap or Merlin (red).

(B) Quantification of Yap pixel intensity of pictures represented in (A) (n ≥ 6 mice).

(C) Quantification of Merlin pixel intensity of pictures represented in (A) (n ≥ 6 mice).

(D) Immunostaining on non-cartilaginous airways of control Fgf10LacZ, Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f-Fgf10LacZ and Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-Fgf10LacZ lungs for secretory cell marker Scgb1a1 (green) with either Yap (red) or Wnt7b (red) or Dkk1 (red) or Fgfr2b (red) and β-gal staining of Fgf10LacZ. Black arrowheads indicate Fgf10 expression in ASMCs.

(E) Quantification of pixel intensity of Yap, Wnt7b, Dkk1 and Fgfr2b signals represented in (D) (n ≥ 6 mice).

(F) Relative mRNA expression of Wnt7b and Dkk1 in control, Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f and Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f lungs.

(G) Western blot analysis showing FGF10, YAP, FGFR2B, P-MST1/2, and WNT7B protein expression in control, Scgb1a1-Mst1/2f/f (MST1/2 KO) and Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f (ILK KO) lungs.

(H) Quantification of pixel intensities of pictures represented in (I) (n ≥ 6 mice).

(I) Immunostaining on control and Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f non-cartilaginous airways for Merlin (red) or phospho-Mst1/2 (red).

Nuclei, DAPI (blue). **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. n ≥ 6.; error bars mean ± SEM. Scale bar, 100 μm. (See also Figures S2, S3, S4, S6 and S7)

Fgf10 overexpression or inactivation of Ilk in secretory cells extend the basal stem cell niche and induces secretory and basal stem/progenitor cell hyperplasia in conducting airways

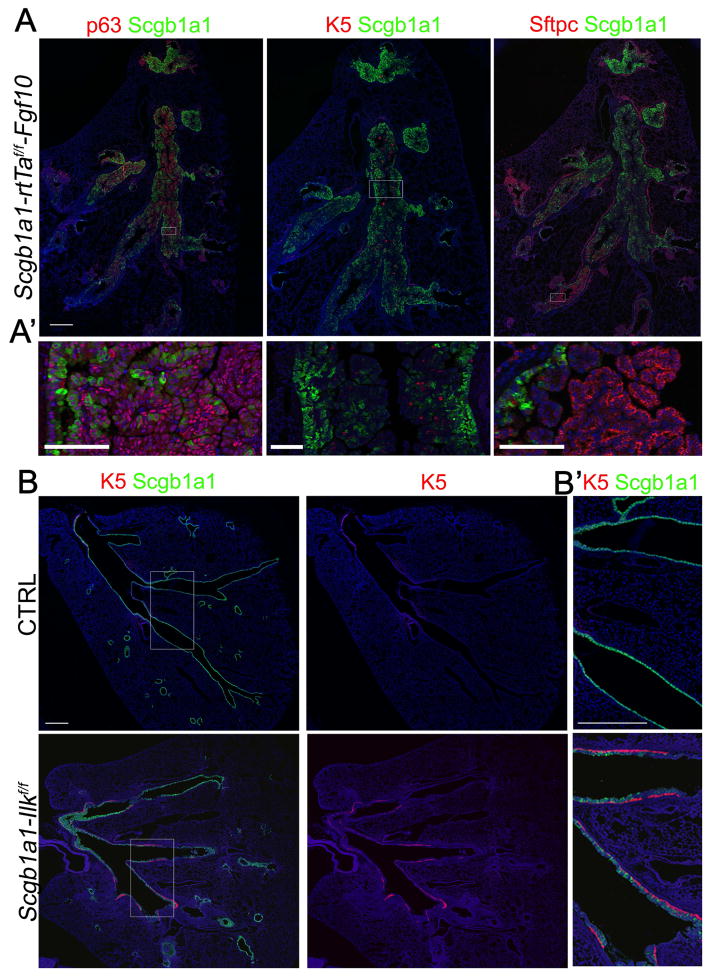

Based on our observation that ectopic BSCs do not populate the non-cartilaginous airways upon Mst1/2 inactivation in secretory cells (data not shown), despite induction of Fgf10 in ASMCs, we suspected that Fgf10 levels did not reach the threshold required to recruit BSCs to the non-cartilaginous airways. To determine whether Fgf10 expression alone is sufficient to induce secretory and BSC amplification in the non-cartilaginous airways in the absence of injury, we overexpressed Fgf10 in all secretory cells for 5.5 weeks starting at 3 weeks of age using Scgb1a1-Cre;Rosa26R-LSL-rtTa;Tet-Fgf10 mice or in ASMCs for 10 weeks starting at 9 weeks of age using Acta2-CreERT2;Rosa26R-LSL-rtTa;Tet-Fgf10 mice, which were first placed on tamoxifen chow for 3 weeks starting at 6 weeks of age (referred to as Scgb1a1-rtTaf/f-Fgf10 and Acta2--rtTaf/f-Fgf10 respectively). These studies demonstrate that Fgf10 overexpression is sufficient to allow for BSCs to populate the non-cartilaginous airways (Fig. 3A, S4 and S5A).

Figure 3. Fgf10 overexpression or Ilk deletion in secretory cells induces basal cell recruitment to the non-cartilaginous conducting airways.

(A) Immunostaining for Scgb1a1 (green) and p63 (red) (left), or Scgb1a1 (green) and K5 (red) (middle), or Scgb1a1 (green) and Sftpc (red) (right) on non-cartilaginous airways of Scgb1a1-rtTaf/f-Fgf10 mice, which were induced with doxycycline for 5.5 weeks starting at 3 weeks of age. (A′) High magnification of selected regions in A.

(B) Immunostaining on control and Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f non-cartilaginous airways for Scgb1a1 (green) and K5 (red) or K5 (red) by itself. (B′) High magnification of selected regions in B.

Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 500 μm (A,C), 100 μm (A′), 300 μm (B′) (See also Figure S5).

Interestingly, Merlin activates the Hippo pathway by regulating Mst1/2 and sequestering Yap in the cytoplasm (Yin et al., 2013). Merlin has been shown to stabilized by binding integrin-linked kinase (Ilk) and Ilk-associated proteins such as paxillin and Rsu (Apte et al., 2009; Donthamsetty et al., 2013; Manetti et al., 2013; Serrano et al., 2013); it is degraded during cell spreading by mechanisms that are not fully understood (Cooper and Giancotti, 2014; Das et al., 2015; Okada et al., 2009). Intriguingly, we observed high expression of Merlin levels in secretory and ciliated cells of non-injured lungs and low expression in surviving, spreading epithelial cells after naphthalene-induced airway epithelial injury (Fig. 2A,C). To determine whether robust activation of the ASMC niche with higher and more sustained levels of Fgf10 permits BSCs to populate the non-cartilaginous conducting airways, we deleted Ilk from secretory cells using Scgb1a1-Cre;Ilkf/f mice (referred to as Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f). We found that Merlin protein levels as well as Mst1/2 phosphorylation is decreased (Fig. 2H,I), while nuclear Yap and Wnt7b is increased in secretory and ciliated daughter cells of Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f mice (Fig. 2D–G). Importantly, we found a significant increase in Fgf10 expression in the ASMC niche of Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f lungs compared to controls as well as Scgb1a1-Cre;Mst1/2f/f mice (Fig. 2D,G and Fig. S3A,B,D) and elevated numbers of secretory cells and BSCs (Fig. 2D, 3B and S6E) in conducting airways by 1 month after Ilk deletion. Interestingly, the airways of Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f mice demonstrated subepithelial fibrosis, with increased stromal SMAD2/3 phosphorylation, and airway obstruction (Fig. S4 and S5B). The recruitment of BSCs to the conducting airways in Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f lungs mostly occurred within the upper and middle non-cartilaginous airways; though it should be noted that BSCs were occasionally found along the entire length of the non-cartilaginous conducting airways all the way down to the distal broncho-alveolar duct junctions (BADJ) (Fig. 3B). Lineage tracing using the Rosa26-mTmG allele in the airways of Scgb1a1-Cre(ER);Ilkf/f;Rosa26-mTmG mice supports the concept that the aberrant accumulation of BSCs and subepithelial fibrotic myofibroblasts in these airways is not due to dedifferentiation of secretory cells (Fig. S6A,B,D).

Integrin-linked kinase (Ilk) inactivation increases Fgf10-Fgfr2b signaling downstream of Yap to drive secretory and basal stem/progenitor cell amplification in non-cartilaginous conducting airways

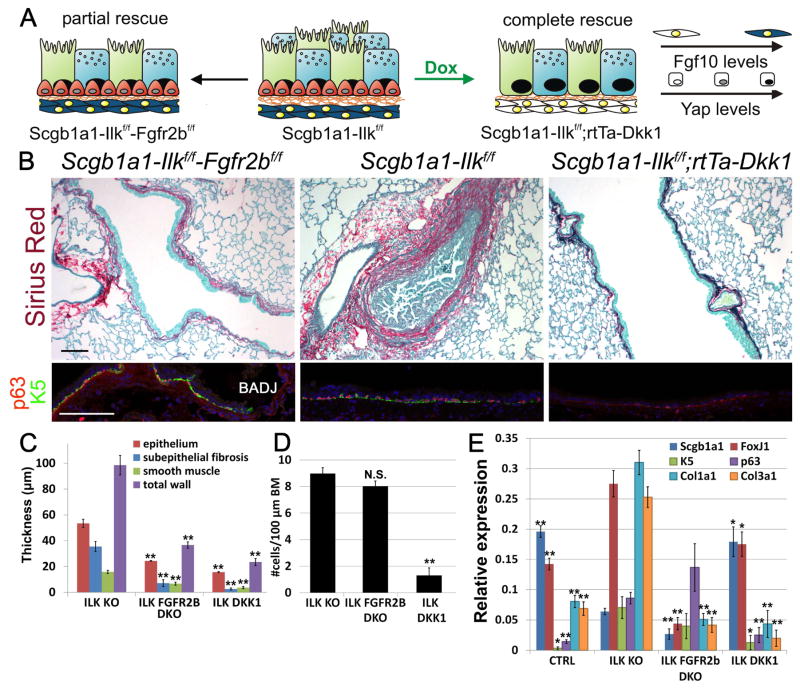

To establish whether the secretory and BSC amplification in Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f non-cartilaginous airways depends on Fgf10 secretion by the ASMC niche, we simultaneously inactivated Ilk and Fgfr2b in secretory, but not BSCs using Scgb1a1-Cre;Ilkf/f;Fgfr2bf/f mice (referred to as Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-Fgfr2bf/f). Despite the rescue of the secretory cell hyperplasia and the subepithelial fibrosis phenotype, we found that the non-cartilaginous airways still showed aberrant accumulation of BSCs (Fig. 4A–E, S4 and S7). However, when we blocked Wnt7b-induced Fgf10 expression in the ASMC niche by overexpressing Dkk1 or deleting Wnt7b simultaneously with Ilk in secretory cells using respectively, Scgb1a1-Cre;Ilkf/f;Rosa26-rtTA;Tet-Dkk1;Fgf10LacZ (referred to as Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-rtTa-Dkk1-Fgf10LacZ) or Scgb1a1-Cre;Ilkf/f;Wnt7bf/f (referred to as Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-Wnt7bf/f) mice, we rescued both the amplification of BSCs/secretory cells and subepithelial fibrosis (Fig. 4A–E, Fig.S3B, S4, S6F and S7). Evidence of inactivation of the Hippo pathway was provided by the nuclear localization of Yap in airway epithelial cells from rescued lungs (Fig. S7).

Figure 4. Fgf10 expression in ASMCs drives secretory and basal cell amplification in the lower non-cartilaginous conducting airways upon Ilk inactivation.

(A) Schematic representation of airway BSC amplification or loss, stromal Fgf10 or nuclear Yap levels in the different mutant strains.

(B) Sirius red (collagen)/fast green staining and immunostaining on Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f (ILK KO), Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-Fgfr2bf/f (ILK FGFR2b DKO) and Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-rtTa-Dkk1 (ILK DKK1) non-cartilaginous airways for BSC markers p63 (red) and Keratin 5 (K5) (green) or secretory cell marker Scgb1a1 (green) and Yap (red).

(C,D) Morphometric analysis of airway remodeling (C) and quantification of BSC numbers (D) of images represented in (B).

(E) Relative mRNA levels of Scgb1a1 (secretory cells), FoxJ1 (ciliated cells), K5 (BSCs), p63 (BSCs), Col1a1 (collagen) and Col3a1 (collagen) in control, Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f, Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-Fgfr2bf/f and Scgb1a1-Ilkf/f-rtTa-Dkk1 lungs.

Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. n ≥ 6.; error bars mean ± SEM. Scale bars, 100 μm. (See also Figures S3, S4, S6F and S7)

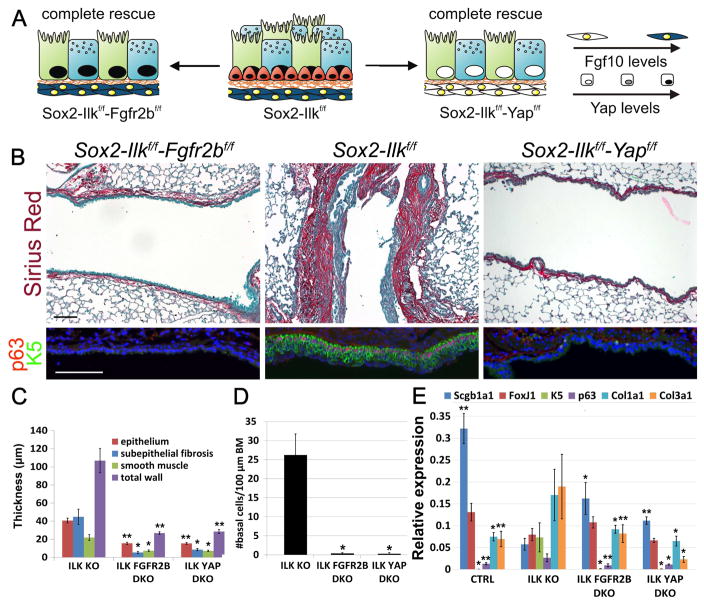

To further confirm that the aberrant accumulation of BSCs upon secretory cell-specific Ilk deletion is due to a non-cell autonomous effect mediated by Fgf10 secreted by the ASMC niche downstream of Yap, we generated Sox2-CreERT2;Ilkf/f, Sox2-CreERT2;Ilkf/f;Fgfr2bf/f and Sox2-CreERT2;Ilkf/f;Yapf/f mouse lines (referred to as Sox2-Ilkf/f, Sox2-Ilkf/f-Fgfr2bf/f and Sox2-Ilkf/f-Yapf/f, respectively), in which we either deleted Ilk alone or in combination with either Fgfr2b or Yap in all airway epithelial cells including BSCs. We found BSC and secretory cell hyperplasia as well as sub-epithelial fibrosis in the non-cartilaginous airways of Sox2-Ilkf/f mice in which Fgf10 is upregulated in the AMSC niche. However, this phenotype was rescued in Sox2-Ilkf/f-Fgfr2bf/f mice, in which the airway epithelium cannot respond to upregulated Fgf10, as well as in Sox2-Ilkf/f-Yapf/f mice in which the ASMC niche does not secrete Fgf10 (Fig. 5A–E, S3C, S4 and S7). These results indicate that epithelial Ilk efficiently activates the Hippo pathway to maintain airway epithelial cell quiescence by inhibiting Fgf10 secretion from the ASMC niche.

Figure 5. Fgf10-Fgfr2b signaling downstream of Yap drives secretory and basal cell amplification in the lower non-cartilaginous conducting airways upon Ilk inactivation.

(A) Schematic representation of non-cartilaginous airway secretory/ciliated amplification and BSC amplification or loss, stromal Fgf10 or nuclear Yap levels upon airway epithelial Ilk/Fgfr2b ablation, Ilk ablation and Ilk/Yap ablation. All lungs were collected at 2 months after tamoxifen induction.

(B) Sirius red (collagen)/fast green staining and immunostaining on Sox2-Ilkf/f-Fgfr2bf/f, Sox2-Ilkf/f, and Sox2-Ilkf/f-Yapf/f non-cartilaginous airways for BSC markers p63 (red) and Keratin 5 (K5) (green).

(C,D) Morphometric analysis of airway remodeling (C) and quantification of BSC numbers (#) per 100 μm basement membrane (D) from images represented in (B).

(E) Relative mRNA levels of Scgb1a1 (secretory cells), FoxJ1 (ciliated cells), K5 (BSCs), p63 (BSCs), Col1a1 (collagen) and Col3a1 (collagen) in control, Sox2-Ilkf/f (ILK KO), Sox2-Ilkf/f-Fgfr2bf/f (ILK FGFR2b DKO) and Sox2-Ilkf/f-Yapf/f (ILK YAP DKO) lungs.

Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. n ≥ 6.; error bars mean ± SEM. Scale bars, 100 μm. (See also Figures S3, S4 and S6C)

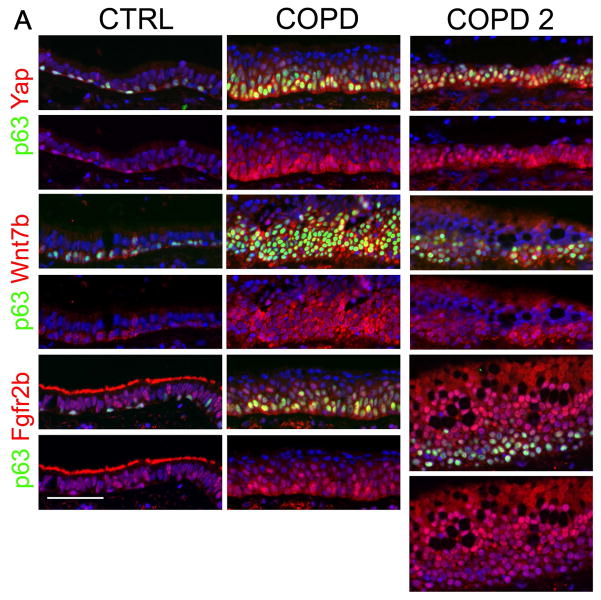

The Yap-Wnt7b-Fgf10 regenerative pathway is chronically activated in COPD airways

Our results demonstrate that epithelial-mesenchymal interactions coordinated by Hippo signaling actively maintain postnatal tissue homeostasis, and downregulation of Hippo signaling during injury is required to initiate regeneration and recruitment of stem cells to the site of injury. However, the activation of the Yap-Wnt7b-Fgf10 regenerative pathway may need to be delicately controlled to maintain airway epithelial quiescence and prevent airway remodeling; indeed, our data in the preceding animal modeling studies supports the concept that deregulation of Hippo signaling leads to aberrant repair and regeneration in the lung. We examined whether this repair cascade is deregulated in the airways of human subjects with COPD, a chronic lung disease associated with airway remodeling and obstructive physiology. Increased nuclear YAP levels, FGFR2b and WNT7b expression were observed in squamous metaplastic areas within the airway epithelium of COPD subjects (Fig. 6 and Table S1). These findings provide proof-of-concept that the Hippo pathway is inactivated to induce Fgf10 expression and BSC amplification in human COPD.

Figure 6. The Hippo pathway regulates Fgf10 signaling to induce basal stem/progenitor cell amplification in COPD.

(A) Immunostaining on control and COPD distal airways for BSC marker p63 (green) and Yap (red) or Wnt7b (red) or Fgfr2b (red). (n=5). Note staining of cilia for Fgfr2b in control but not in COPD airways indicating a loss of ciliated cells in COPD. (See also Table S1)

Discussion

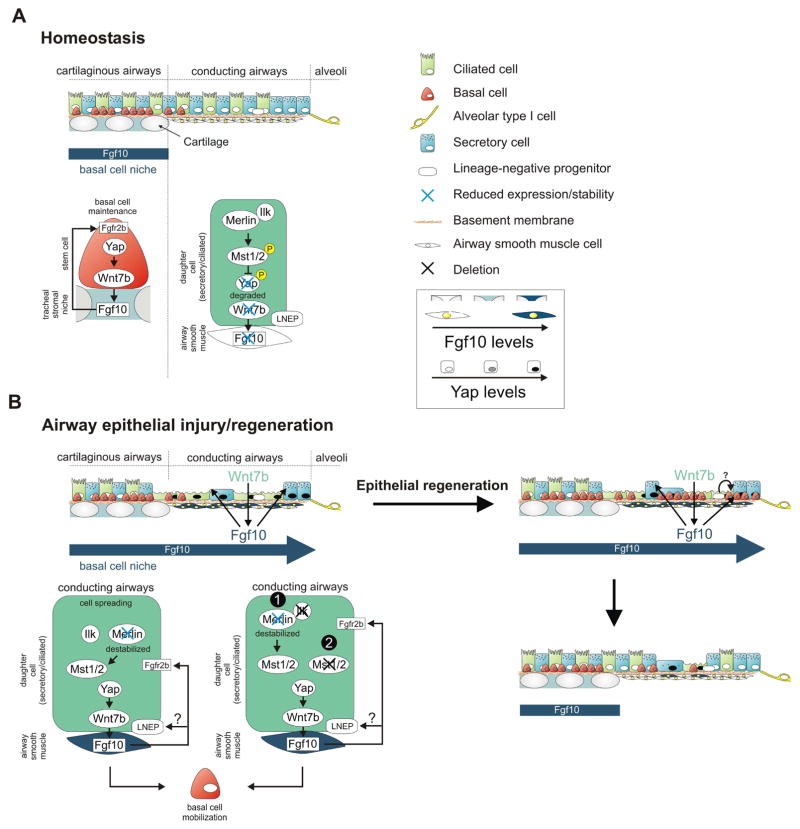

We report a mode of stem cell regulation in which BSCs generate and maintain their own localized stem cell niche by regulating the expression of Fgf10 within the stromal compartment of the cartilaginous airways (Fig. 7A); loss of this tonic Fgf10 signaling leads to BSC depletion. We further demonstrate that the Hippo signaling pathway in either tracheal BSCs themselves during homeostasis, or in sparsely surviving and spread out differentiated epithelial cells after injury, controls the maintenance and neo-generation of Fgf10 expressing stromal stem cell niches in the lung. We previously reported that upon airway epithelial injury, ASMCs that envelop the non-cartilaginous airways, are activated to release Fgf10 (Volckaert et al., 2011). Fgf10 then binds Fgfr2b on BSCs to mobilize and expand this stem/progenitor pool by inhibiting their premature differentiation, thus facilitating efficient lung regeneration (Fig. 7B). The source of recruited BSCs to sites of injury may depend on the level and type of injury, and may include the recently identified lineage-negative epithelial progenitors (LNEPs) (Ray et al., 2016; Vaughan et al., 2015). In our model, we show via lineage tracing that the ectopic BSCs lining the non-cartilaginous airways are not derived from secretory cells, supporting the concept that induction of Fgf10 expression by the stromal niche allows for the recruitment of tracheal BSCs or the differentiation of Sox2+ LNEPs along the BSC lineage.

Figure 7. Model showing how Yap maintains and generates basal like stem cells by activating the stromal niche during homeostasis and epithelial regeneration.

(A) During homeostasis, basal stem/progenitor cells are only found in the trachea, where they maintain themselves by inducing Fgf10 expression in the tracheal stromal niche downstream of Yap. Ilk positively regulates the Hippo pathway in conducting airway epithelial cells to maintain their quiescence by inhibiting Yap-mediated activation of Fgf10 expression in ASMCs.

(B) Hippo pathway inactivation in conducting non-cartilaginous airway epithelium in response to injury or by deleting Ilk (4) or Mst1/2 (5) results in nuclear Yap localization, increased epithelial Wnt7b expression and Fgf10 expression in ASMCs, which reciprocally breaks epithelial quiescence. The Fgf10-expressing basal stem cell niche extends into the non-cartilaginous airways allowing for BSC mobilization into the lower conducting airways upon airway epithelial Ilk deletion. Alternatively, Fgf10 released by the activated ASMC niche could drive the differentiation of LNEPs, which are scattered along the lower conducting airways, into the basal stem/progenitor cell lineage.

We found that Ilk and Merlin, the stability of which is controlled by its interaction with Ilk, tune the Hippo pathway and the nuclear translocation of Yap that leads to the induction of Wnt7b expression; this, in turn, triggers Fgf10 expression in the airway niche to activate BSCs and/or induce differentiation of LNEPs. We demonstrate that Ilk positively regulates the Hippo pathway in non-cartilaginous airway epithelial cells to maintain their quiescence during normal homeostasis by inhibiting Yap-mediated activation of the Wnt7b-Fgf10 epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk between airway epithelial progenitor cells and their stromal niche. Our findings suggest that integrin signaling through Ilk represents a sensor of airway epithelial injury that acts upstream of the Wnt7b-Fgf10 repair cascade, and functions as a gatekeeper for airway epithelial quiescence; this may prevent sustained airway remodeling as observed in chronic lung diseases, such as COPD and asthma. Interestingly, Ilk has been shown to act as an upstream Hippo pathway activator in the liver where it is essential for the proper termination of the regenerative response (Apte et al., 2009). However, more recently, Ilk was reported to inhibit the Hippo pathway in human breast, prostate and colon cancer cell lines (Serrano et al., 2013), suggesting that Ilk regulation of Hippo signaling may be contextual (e.g. normal versus cancer cells). A recent paper has also defined a role for epithelial Shh in the regulation of airway epithelial cell quiescence; similar to our studies, this occurs through an indirect non-cell autonomous mechanism (Peng et al., 2015). Together, these studies highlight the critical importance of developmental pathways in epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk during injury repair in adult mammalian lungs.

Our data also demonstrate substantial aberrant signaling of these developmental pathways in chronic airway remodeling associated with human COPD. This suggests that chronic activation of the ASMC niche in COPD may drive BSC amplification or drive the differentiation of LNEPs present in the conducting airways along the BSC lineage, possibly preventing them from contributing to alveolar epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. This may explain why airway BSC metaplasia precedes emphysema in COPD (Auerbach et al., 1961; Dye and Adler, 1994; Kennedy et al., 1984; Leopold et al., 2009; Lumsden et al., 1984; Peters et al., 1993; Shaykhiev and Crystal, 2013; Shaykhiev et al., 2011). Thus, while transient Fgf10 expression by ASMCs is critical for proper airway epithelial regeneration in response to injury (Volckaert et al., 2013a; Volckaert et al., 2011), sustained Fgf10 secretion by the stem cell niche, in response to chronic Ilk/Hippo inactivation (i.e. chronic nuclear Yap), results in pathological airway remodeling. Finally, our studies support the therapeutic targeting of the Hippo/Fgf10/Fgfr2b signaling axis in chronic lung disease.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Stijn De Langhe (sdelanghe@uabmc.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All mice were bred and maintained in a pathogen-free environment with free access to food and water. Both male and female mice were used for all experiments. Tet-Dkk1 (Volckaert et al., 2011), Tet-Fgf10 (Clark et al., 2001), Rosa26-rtTa (Volckaert et al., 2011), Scgb1a1-Cre (Ji et al., 2006; Simon et al., 2006), Fgfr2bf/f (De Moerlooze et al., 2000), Fgf10LacZ (Kelly et al., 2001), Ilkf/f (Grashoff et al., 2003), Sox2-CreERT2 (JAX 017593), Rosa26R-Confetti (JAX 017492), Scgb1a1-CreER (JAX 016225), Rosa26R-LSL-rtTa (Belteki et al., 2005), Rosa26-mTmG (JAX 007676), Mst1/2f/f (JAX 017635), Wnt7bf/f (Rajagopal et al., 2008), Acta2-CreERT2 (Wendling et al., 2009), Krt5-CreERT2 (JAX 018394) and Yapf/f (Xin et al., 2013) mice were previously described. All experiments were approved by the National Jewish Health and University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Naphthalene (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in corn oil at 30 mg/ml and administered intraperitoneally at 8 weeks of age, with doses adjusted to achieve a 95% decrease in the abundance of Scgb1a1 mRNA in total lung RNA of WT mice at 3 days after injection. For tamoxifen induction, mice were placed on tamoxifen containing food (rodent diet with 400 mg/kg tamoxifen citrate; Harlan Teklad TD.130860) at 6–8 weeks of age for 2 to 3 weeks and lungs were isolated 8–13 weeks later. For doxycycline induction: mice were placed on doxycycline containing food (rodent diet with 625 mg/kg dox; Harlan Teklad TD.09761). Lungs from non tamoxifen treated mice were isolated at 4–10 weeks of age.

METHODS DETAILS

β-gal staining

Fgf10LacZ lungs were dissected and fixed in 4% formalin in PBS at room temperature for 5 minutes and rinsed in PBS. For staining, X-Gal (Research Products International, B71800) was dissolved in Dimethylformamide and freshly added to LacZ staining solution (5mM Potassium hexacyanoferrate(III), 5mM Potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) trihydrate, 2mM MgCl2, 81mM Na2HPO4 and 20mM NaH2PO4) at a final concentration of 1mg/ml. Lungs were inflated with freshly prepared LacZ staining/X-gal solution and stained overnight at 37°C in the dark with gentle agitation. After rinsing with PBS, lungs were postfixed in 4% formalin in PBS at room temperature overnight. For microtome sections, after 4% formalin fixation, lungs were washed in PBS, dehydrated, and paraffin embedded.

Picro-Sirius/Fast green FCF staining

5 μm paraffin sections were stained for collagen as follows. In brief, after deparaffinization, slides were rehydrated through a series of decreasing ethanol concentrations. Slides were then incubated in Sirius red/Fast green FCF solution (0.1% Fast green FCF (F99-10; Fisher) dissolved in 0.1 % Sirius Red in saturated Picric acid (F-357-2; Rowley Biochemical Institute)) for 1 h. After incubation, slides were washed in 0.01 N Hydrochloric Acid for 2 min, rinsed in dH20, dehydrated, cleared in toluene and mounted.

Immunohistochemistry and fluorescence

All staining was done on paraffin sections of formalin-fixed lungs or tracheas. Immunofluorescent staining was performed with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti–β-tubulin (1:500; 3F3-G2; Seven Hills Bioreagents), goat anti-Scgb1a1 (1:200; clone T-18; sc-9772; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), rabbit anti-Scgb1a1 (1:500; WRAB-CCSP; Seven Hills Bioreagents), rabbit anti-beta-galactosidase (1:500; 100–4136; Rockland Immunochemicals Inc), rabbit anti-Fgfr2 (Bek) (1:500; clone C-17; sc-122; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), mouse anti-α-Actin (1:500; clone 1A4; sc-32251; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), chicken anti-GFP (1:250; GFP-1020; Aves Labs Inc.), rabbit anti-Keratin 5 (1:200; clone EP1601Y; MA5-14473, Thermo Fisher Scientific), rabbit anti-FGF10 (1:1000; AP14882PU-N; Acris) (1:1000, ABN44, Millipore), rabbit anti-p63 (ΔN) (1:500; clone poly6190, 619002; BioLegend), rabbit anti-ILK (1:50; 3862S; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), mouse anti-p63 (1:200; clone 4A4; CM163B; Biocare Medical), rabbit anti-phospho-Mst1/2 (1:250; 3681S; Cell Signaling), goat anti-p-SMAD2/3 (Ser423/425) (1:100; sc-11769; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), rabbit anti-RFP (1:200; 600-401-379; Rockland Immunochemicals Inc), rabbit anti-Sftpc (1:200; WRAB-9337; Seven hills bioreagents), rabbit anti-YAP (1:50; 4912S; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), mouse anti-Yap (1:100; clone 63.7; sc-101199; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), rabbit anti-DKK1 (1:200; clone H-120; sc-25516; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), mouse anti-E-Cadherin (1:200; 610181; BD Transduction Laboratories), goat anti-Wnt7b (1:25; AF3460; R&D systems), rabbit anti-Merlin (Nf2) (1:250; clone A-19; sc-331; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), rabbit anti-Mst1/2 (1:200; ab87322; Abcam), mouse anti-PCNA (PCNA staining kit; 93–1143; Zymed Laboratories Inc.). After deparaffinization, slides were rehydrated through a series of decreasing ethanol concentrations, antigen unmasked by either microwaving in citrate-based antigen unmasking solution (Vector Labs, H-3000) or by incubating sections with proteinase K (7.5μg/ml) (Invitrogen, 25530-049) for 7 min at 37°C. Tissue sections were then washed in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 and blocked with 3% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), 0.4% Triton in TBS for 30 min at room temperature followed by overnight incubation of primary antibodies diluted in 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton in TBS. The next day, slides were washed in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 and incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton in TBS for 3h at room temperature. All fluorescent staining was performed with appropriate secondary antibodies from Jackson Immunoresearch, except for goat anti-chicken FITC (1:200; F-1005; Aves Labs, Inc.). Slides were mounted using Vectashield with (Vector Labs, H-1200) or without DAPI (Vector Labs, H-1000) depending on immunostaining.

In Situ Cell Death Detection (TUNEL staining)

After deparaffinization, slides were rehydrated through a series of decreasing ethanol concentrations and permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100 in TBS for 8 minutes. TUNEL staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein; 11 684 795 910; Roche). After completion of TUNEL staining, slides were subjected to immunofluorescence staining using goat anti-Scgb1a1 (1:100; clone T-18; sc-9772; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). Slides were mounted using Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Labs, H-1200).

Proliferation

Mice were given intraperitoneal injections of 10 μl BrdU (GE Healthcare; RPN201) per gram body weight 4 hours before sacrifice. Lungs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, and paraffin embedded. Sections were treated with monoclonal mouse anti-BrdU (clone BU-1; RPN202; GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FITC-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibodies were used (Jackson Immunoresearch). All slides were mounted using Vectashield with DAPI.

Western Blot

Left lobes of lung tissue were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1% NP40, 10% Glycerol, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and lysates were separated on a 4%–12% acrylimide gel and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Antibodies used for immunoblotting were: rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:3000; ab9485; Abcam), rabbit anti-FGF10 (1:1000; AP14882PU-N; Acris) (1:1000, ABN44, Millipore), rabbit anti-FGFR2 (1:500; sc-122; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), rabbit anti-YAP (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), goat anti-WNT7B (1:500; AF3460; R&D systems), rabbit anti-p-MST1/MST2 (1:500; 3681s; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

In Situ Hybridization

The whole-mount in situ hybridization protocol used was based on a previously described method (Winnier et al., 1995). Tracheas were dissected and fixed in 4% formalin in PBS overnight. The next day, tracheas were rinsed in PBS and dehydrated to 100% ethanol. Tracheas were then bleached in 4 parts ethanol, 1 part 30% hydrogen peroxide for 1h at room temperature. Tracheas were sequentially washed in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST), treated with 1ml of 7.5μg/ml proteinase K (Invitrogen, 25530-049) in PBST for 5 min at room temperature, washed in PBST containing 2mg/ml glycine, washed in PBST, fixed in 4% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature and washed in PBST. Tracheas were then placed in hybridization solution (prewarmed to 70°C) (50% deionized formamide, 5x SSC buffer, 0.05mg/ml tRNA, 1% SDS and 0.05 mg/ml Heparin), replaced with fresh hybridization solution and prehybridized at 70°C for 1h with gentle agitation. Tracheas were then hybridized in probe/hybridization solution overnight at 70°C with gentle agitation. T he next day, tracheas were washed in Solution I (50% deionized formamide, 5x SSC buffer, 1% SDS) for 2x 30 min at 70°C. After solution I washes, tracheas w ere washed in 1:1 Solution I: Solution II (0.5M NaCl, 10mM Tris pH7.5, 0.1% Tween-20) for 10 min at 70°C, washed in Solution II for 3x 5min at room temperature, 2x 30min in 100μg/ml RNAse A (Roche, 109169) in Solution II at 37°C, 2x 30min in Solution III (50% formamide, 2X SSC) for 30min at 65°C and washed wit h TBST/0.5mg/ml Levamisole. Tracheas were then blocked in blocking solution containing 2% Blocking Reagent (11096176001, Sigma-Aldrich), 10% Heat inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (HI-FBS) in TBST/0.5mg/ml Levamisole for 1h at room temperature and then incubated with sheep Anti-Digoxigenin-AP, (1:2000, 11093274910, Sigma-Aldrich) in 1% Blocking Reagent, 1% HI-FBS in TBST/0.5mg/ml Levamisole at 4°C overnight. Blocking Reagent was prepared by dissolving in Malic acid buffer (100mM Maleic acid, 150mM NaCl, pH7.5). The next day, samples were washed 5–6 times with TBST/0.5mg/ml Levamisole and washed in the same solution overnight at 4°C. The following d ay, tracheas were washed with NTMT/Alkaline Phosphatase buffer (100mM NaCl, 100mM Tris pH9.5, 50mM MgCl, 0.1% Tween-20 and 0.5mg/ml Levamisole) 2x for 20min at room temperature. Tracheas were then incubated in BM purple solution (11442074001, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37° degrees in the dark until the signal appears. Finally, tracheas were washed in PBS, post-fixed in 4% formalin in PBS at room temperature. A 584-bp fragment of mouse Fgf10 cDNA was used as template for the synthesis of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled riboprobe (Bellusci et al., 1997) using DIG RNA labeling mix (Roche, 11277073910).

Microscopy and imaging

Tissue was imaged using a micrometer slide calibrated Zeiss Axioimager microscope using axiovision software, a Leica MZ16FA stereomicroscope, a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope using ZEN imaging software as well as a Nikon A1R confocal with NIS-elements software. Subepithelial collagen thickness was quantified on Picro-sirius red stained sections. Structural changes to the airway were morphometrically analyzed as follows: the thickness of the bronchial epithelial layer, subepithelial fibrosis, smooth muscle layer, and total wall was measured on H&E and picro-sirius red stained sections. A minimum of 5 bronchi, measuring 150–350 μm in luminal diameter, were analyzed per mouse (n≥6). BSCs in trachea were quantified covering the entire length of the trachea from cartilage ring 1 to 10 of each mouse using 10–20X magnification fields and was performed on the basis of nuclear staining with DAPI (nuclei) and immunostaining for the BSC specific markers K5/p63 and expressed as the mean number of BSCs per 100 μm of basement membrane or per section. In the lung, cells were counted using at least 5–10 non-overlapping 10–20X magnification fields from ≥6 different lungs. Images were processed and analyzed using ImageJ/Fiji (NIH) and Adobe Photoshop Creative Suite 3 (Adobe) software. Immunostaining intensity was quantified after thresholding of pixel intensities.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from lung accessory lobes using RNALater (Invitrogen, AM7021) and Total RNA Kit I (Omega Biotek, R6834-02) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometry. cDNA was generated using Maxima™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis (Fisher Scientific, FERK1642) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, 4369016) directed against the mouse targets β-glucuronidase (Mm00446953_m1), Scgb1a1 (Mm00442046_m1), FoxJ1 (Mm00807215_m1), keratin 5 (K5) (Mm01305291_g1), p63 (Trp63) (Mm00495788_m1), Muc5a/c (Mm01276718_m1), Col1a1 (Mm00801666_g1), Col3a1 (Mm01254476_m1), Wnt7b (Mm00437358_m1), Dkk1 (Mm00438422_m1). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a StepOne Plus system (Applied Biosystems). Data were presented as expression relative to the housekeeping gene β-glucuronidase ± standard error of mean (SEM). Each experiment was repeated with samples obtained from at least 3 different lungs preparations.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All results are expressed as mean values ± SEM. The ‘n’ represents biological replicates and can be found in the figure legends. The significance of differences between 2 sample means was determined by unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Basal stem cells generate their own Fgf10 expressing stromal niche via Yap-Wnt7b.

ILK mediated Hippo signaling actively maintains adult airway epithelial quiescence.

Hippo inactivation in mature daughter cells activates a basal stem cell niche.

Integrin linked kinase senses airway epithelial injury to drive regeneration.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH R01 HL107307, DFG (BE443/4-1 and BE443/6-1), Loewe and UKGM to S.B., Munich Heart Alliance to R.F., and NIH R01 HL126732, HL092967, HL132156 March of dimes 1-FY15-352 and the Pulmonary fibrosis foundation Albert Rose established investigator award to S.D.L.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Author contributions

T.V. and T.Y. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote and edited the manuscript. H.B., C.C., A.S. and L.S. performed experiments. E.E, C.D., V.T. and S.B edited the manuscript. R.F. wrote and edited the manuscript and provided floxed Ilk mice. S.D.L conceived and led the project, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Scadden DT, Apte U, Gkretsi V, Bowen WC, Mars WM, Luo JH, Donthamsetty S, Orr A, Monga SP, Wu C, Michalopoulos GK. Enhanced liver regeneration following changes induced by hepatocyte-specific genetic ablation of integrin-linked kinase. Hepatology. 2009;50:844–851. doi: 10.1002/hep.23059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach O, Stout AP, Hammond EC, Garfinkel L. Changes in bronchial epithelium in relation to cigarette smoking and in relation to lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:253–267. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196108102650601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Rackley CR, Bowie EJ, Keene DR, Stripp BR, Randell SH, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellusci S, Grindley J, Emoto H, Itoh N, Hogan BL. Fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and branching morphogenesis in the embryonic mouse lung. Development. 1997;124:4867. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belteki G, Haigh J, Kabacs N, Haigh K, Sison K, Costantini F, Whitsett J, Quaggin SE, Nagy A. Conditional and inducible transgene expression in mice through the combinatorial use of Cre-mediated recombination and tetracycline induction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JC, Tichelaar JW, Wert SE, Itoh N, Perl AK, Stahlman MT, Whitsett JA. FGF-10 disrupts lung morphogenesis and causes pulmonary adenomas in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L705–715. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J, Giancotti FG. Molecular insights into NF2/Merlin tumor suppressor function. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2743–2752. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das T, Safferling K, Rausch S, Grabe N, Boehm H, Spatz JP. A molecular mechanotransduction pathway regulates collective migration of epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:276–287. doi: 10.1038/ncb3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moerlooze L, Spencer-Dene B, Revest JM, Hajihosseini M, Rosewell I, Dickson C. An important role for the IIIb isoform of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) in mesenchymal-epithelial signalling during mouse organogenesis. Development. 2000;127:483–492. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donthamsetty S, Bhave VS, Mars WM, Bowen WC, Orr A, Haynes MM, Wu C, Michalopoulos GK. Role of PINCH and its partner tumor suppressor Rsu-1 in regulating liver size and tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye JA, Adler KB. Effects of cigarette smoke on epithelial cells of the respiratory tract. Thorax. 1994;49:825–834. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.8.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grashoff C, Aszodi A, Sakai T, Hunziker EB, Fassler R. Integrin-linked kinase regulates chondrocyte shape and proliferation. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Houghton AM, Mariani TJ, Perera S, Kim CB, Padera R, Tonon G, McNamara K, Marconcini LA, Hezel A, et al. K-ras activation generates an inflammatory response in lung tumors. Oncogene. 2006;25:2105–2112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RG, Brown NA, Buckingham ME. The arterial pole of the mouse heart forms from Fgf10-expressing cells in pharyngeal mesoderm. Dev Cell. 2001;1:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SM, Elwood RK, Wiggs BJ, Pare PD, Hogg JC. Increased airway mucosal permeability of smokers. Relationship to airway reactivity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:143–148. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Jacks T. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell. 2005;121:823–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PA, Hu Y, Yamamoto Y, Hoe NB, Wei TS, Mu D, Sun Y, Joo LS, Dagher R, Zielonka EM, et al. Distal airway stem cells yield alveoli in vitro and during lung regeneration following H1N1 influenza infection. Cell. 2011;147:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange AW, Sridharan A, Xu Y, Stripp BR, Perl AK, Whitsett JA. Hippo/Yap signaling controls epithelial progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in the embryonic and adult lung. J Mol Cell Biol. 2015;7:35–47. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Bhang DH, Beede A, Huang TL, Stripp BR, Bloch KD, Wagers AJ, Tseng YH, Ryeom S, Kim CF. Lung Stem Cell Differentiation in Mice Directed by Endothelial Cells via a BMP4-NFATc1-Thrombospondin-1 Axis. Cell. 2014;156:440–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold PL, O’Mahony MJ, Lian XJ, Tilley AE, Harvey BG, Crystal RG. Smoking is associated with shortened airway cilia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden AB, McLean A, Lamb D. Goblet and Clara cells of human distal airways: evidence for smoking induced changes in their numbers. Thorax. 1984;39:844–849. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.11.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetti ME, Geden S, Bott M, Sparrow N, Lambert S, Fernandez-Valle C. Stability of the tumor suppressor merlin depends on its ability to bind paxillin LD3 and associate with beta1 integrin and actin at the plasma membrane. Biol Open. 2013;1:949–957. doi: 10.1242/bio.20122121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Wang Y, Jang SW, Tang X, Neri LM, Ye K. Akt phosphorylation of merlin enhances its binding to phosphatidylinositols and inhibits the tumor-suppressive activities of merlin. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4043–4051. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Saganta A, Tata PR, Law BM, Saez B, Chow R, Prabhu M, Gridley T, Rajagopal J. Parent stem cells can serve as niches for their daughter cells. Nature. 2015;523:597–601. doi: 10.1038/nature14553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KS, Whitsett JA, Di Palma T, Hong JH, Yaffe MB, Zannini M. TAZ interacts with TTF-1 and regulates expression of surfactant protein-C. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17384–17390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng T, Frank DB, Kadzik RS, Morley MP, Rathi KS, Wang T, Zhou S, Cheng L, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. Hedgehog actively maintains adult lung quiescence and regulates repair and regeneration. Nature. 2015;526:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature14984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EJ, Morice R, Benner SE, Lippman S, Lukeman J, Lee JS, Ro JY, Hong WK. Squamous metaplasia of the bronchial mucosa and its relationship to smoking. Chest. 1993;103:1429–1432. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.5.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal J, Carroll TJ, Guseh JS, Bores SA, Blank LJ, Anderson WJ, Yu J, Zhou Q, McMahon AP, Melton DA. Wnt7b stimulates embryonic lung growth by coordinately increasing the replication of epithelium and mesenchyme. Development. 2008;135:1625–1634. doi: 10.1242/dev.015495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey MR, Wilson C, Ory B, Rothenberg SM, Faquin W, Mills AA, Ellisen LW. FGFR2 signaling underlies p63 oncogenic function in squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3525–3538. doi: 10.1172/JCI68899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins EL, Okubo T, Xue Y, Brass DM, Auten RL, Hasegawa H, Wang F, Hogan BL. The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Chiba N, Yao C, Guan X, McConnell AM, Brockway B, Que L, McQualter JL, Stripp BR. Rare SOX2+ Airway Progenitor Cells Generate KRT5+ Cells that Repopulate Damaged Alveolar Parenchyma following Influenza Virus Infection. Stem Cell Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JR, Onaitis MW, Rawlins EL, Lu Y, Clark CP, Xue Y, Randell SH, Hogan BL. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12771–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906850106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scadden DT. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature. 2006;441:1075–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature04957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano I, McDonald PC, Lock F, Muller WJ, Dedhar S. Inactivation of the Hippo tumour suppressor pathway by integrin-linked kinase. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2976. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaykhiev R, Crystal RG. Basal cell origins of smoking-induced airway epithelial disorders. Cell Cycle. 2013;13:341–342. doi: 10.4161/cc.27510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaykhiev R, Otaki F, Bonsu P, Dang DT, Teater M, Strulovici-Barel Y, Salit J, Harvey BG, Crystal RG. Cigarette smoking reprograms apical junctional complex molecular architecture in the human airway epithelium in vivo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:877–892. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0500-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DM, Arikan MC, Srisuma S, Bhattacharya S, Andalcio T, Shapiro SD, Mariani TJ. Epithelial cell PPARgamma is an endogenous regulator of normal lung maturation and maintenance. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:510–511. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-034MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tata PR, Mou H, Pardo-Saganta A, Zhao R, Prabhu M, Law BM, Vinarsky V, Cho JL, Breton S, Sahay A, et al. Dedifferentiation of committed epithelial cells into stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2013;503:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trink B, Osada M, Ratovitski E, Sidransky D. p63 transcriptional regulation of epithelial integrity and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:240–245. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.3.3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan AE, Brumwell AN, Xi Y, Gotts JE, Brownfield DG, Treutlein B, Tan K, Tan V, Liu FC, Looney MR, et al. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature. 2015;517:621–625. doi: 10.1038/nature14112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volckaert T, Campbell A, De Langhe S. c-Myc Regulates Proliferation and Fgf10 Expression in Airway Smooth Muscle after Airway Epithelial Injury in Mouse. PLoS One. 2013a;8:e71426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volckaert T, Campbell A, Dill E, Li C, Minoo P, De Langhe S. Localized Fgf10 expression is not required for lung branching morphogenesis but prevents differentiation of epithelial progenitors. Development. 2013b;140:3731–3742. doi: 10.1242/dev.096560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volckaert T, Dill E, Campbell A, Tiozzo C, Majka S, Bellusci S, De Langhe SP. Parabronchial smooth muscle constitutes an airway epithelial stem cell niche in the mouse lung after injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4409–4419. doi: 10.1172/JCI58097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenfeld J, Shu W, Zhang L, Millar SE, Morrisey EE. The WNT7b promoter is regulated by TTF-1, GATA6, and Foxa2 in lung epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21061–21070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling O, Bornert JM, Chambon P, Metzger D. Efficient temporally-controlled targeted mutagenesis in smooth muscle cells of the adult mouse. Genesis. 2009;47:14–18. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnier G, Blessing M, Labosky PA, Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is required for mesoderm formation and patterning in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2105–2116. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin M, Kim Y, Sutherland LB, Murakami M, Qi X, McAnally J, Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Tan W, Shelton JM, et al. Hippo pathway effector Yap promotes cardiac regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13839–13844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313192110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F, Yu J, Zheng Y, Chen Q, Zhang N, Pan D. Spatial organization of Hippo signaling at the plasma membrane mediated by the tumor suppressor Merlin/NF2. Cell. 2013;154:1342–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Fallon TR, Saladi SV, Pardo-Saganta A, Villoria J, Mou H, Vinarsky V, Gonzalez-Celeiro M, Nunna N, Hariri LP, et al. Yap Tunes Airway Epithelial Size and Architecture by Regulating the Identity, Maintenance, and Self-Renewal of Stem Cells. Dev Cell. 2014;30:151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo W, Zhang T, Wu DZ, Guan SP, Liew AA, Yamamoto Y, Wang X, Lim SJ, Vincent M, Lessard M, et al. p63Krt5 distal airway stem cells are essential for lung regeneration. Nature. 2015;517:616–620. doi: 10.1038/nature13903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.