Abstract

This project compares three neuroimaging biomarkers to predict progression to dementia in subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Eighty-eight subjects with MCI and 40 healthy controls (HCs) were recruited. Subjects had a 3T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and two positron emission tomography (PET) scans, one with Pittsburgh compound B ([11C]PIB) and one with fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG). MCI subjects were followed for up to 4 years and progression to dementia was assessed on an annual basis. MCI subjects had higher [11C]PIB binding potential (BPND) than HCs in multiple brain regions, and lower hippocampus volumes. [11C]PIB BPND, [18F]FDG standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) and hippocampus volume were associated with time to progression to dementia using a Cox proportional hazards model. [18F]FDG SUVR demonstrated the most statistically significant association with progression, followed by [11C]PIB BPND and then hippocampus volume. [11C]PIB BPND and [18F]FDG SUVR were independently predictive, suggesting that combining these measures is useful to increase accuracy in the prediction of progression to dementia. Hippocampus volume also had independent predictive properties to [11C]PIB BPND, but did not add predictive power when combined with the [18F]FDG SUVR data. This work suggests that PET imaging with both [11C]PIB and [18F]FDG may help to determine which MCI subjects are likely to progress to AD, possibly directing future treatment options.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Prognosis, PET, volumetric MRI

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia[1]. It is disabling, potentially fatal and not reversible. The disorder progresses from mild cognitive impairment (MCI), where there are some cognitive symptoms to clinical dementia that involve functional impairment [2]. Not all patients with MCI progress to AD. Clinical tests to predict which patients are at high risk of progressing would improve patient selection for clinical treatment, enable research into new interventions, and allow for family preparation.

Potential neuroimaging biomarkers to predict progression to dementia include elevated brain binding of the positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer [11C]PIB (Pittsburgh compound) that measures the pathognomonic amyloid deposits, decreased brain uptake of [18F]FDG (fluoro-2-deoxy-glucose) that reflects a decreased rate of glucose consumption, and brain atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that indicates neurodegeneration in the disease. AD subjects, when compared to HCs, have demonstrated increased brain [11C]PIB binding[3], lower brain [18F]FDG uptake[3], and lower hippocampus volume. All three of these neuroimaging findings, when seen in MCI, have been associated with a greater rate of progression to dementia [4–12]. There have been few reports, though, investigating all three imaging methods in the same sample of patients in order to compare them and to determine if a multimodal imaging approach can determine who is at risk for developing dementia [13–15]. One of these was a cross-sectional study focused on aging in general and not progression from MCI [14], while another study had limited size and statistical power [15]. Two other studies had a similar design to this one and used data from Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) [13, 16]. We sought to perform a multimodal imaging study in a new and independent patient sample to examine the ability of these distinct imaging assessments to predict progression to dementia from MCI.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Patients of both sexes presented with memory complaints to the Memory Disorders Center at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital between September 2007 and January 2010. Healthy Control (HC) subjects were recruited primarily by local media advertising. All subjects had a medical and psychiatric screening including a physical exam, and neuropsychological and psychiatric evaluation. To rule out unstable medical conditions and possible reversible causes of impairment, all participants had general screening laboratory tests. Apolipoprotein E genotype was assessed as part of the research protocol, and patients were characterized as ε4 carriers (ε3/ε4, ε2/ε4 or ε4/ε4) or ε4 non-carriers. All subjects signed informed consent in this protocol that was approved by our institutional review board for human subjects.

Inclusion criteria were age 55–90 years, a Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 22 or higher, amnestic MCI defined as subjective memory complaints and a score of >1.5 SD below norms on of the following tests of memory: Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) immediate and delayed recall, WMS-III Visual Reproduction I and II immediate and delayed recall, WMS-R Logical Memory I and II immediate and delayed recall. Patients with amnestic MCI with and without deficits in other cognitive domains were included. A comprehensive neuropsychological test battery was administered. Key exclusion criteria were clinical stroke or cortical stroke or large subcortical lacune or infarct (≥ 2 cm diameter in any MRI slice), cognitive deficits primarily due to medical conditions/medications, specific neurologic disorder, e.g. Parkinson’s disease, alcohol/substance abuse/dependence currently or in the past 6 months, current major depression and history of psychosis. If inclusion and exclusion criteria were met, the final diagnosis of MCI was based on a consensus between two expert raters (DPD and YS) [17].

Healthy control subjects were group-matched by age and sex. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for controls were similar, except that cognitive criteria required MMSE score of 28 or higher and scores within 1 SD of norms on the three tests of memory used for MCI inclusion criteria.

MRI Scan acquisition

At baseline, each subject had a brain MRI acquired on a 3T GE MRI scanner (General Electric, Fairfield, CT, USA). T1 weighted spoiled gradient recalled echo (SPGR) sequence images were obtained in 3D using slice thickness of 1.1 mm, TR 9 ms, TE minimum, flip angle 20 degrees, 1 nex, 256 × 256 matrix.

MRI preprocessing

Skull-stripping of T1 images was done with Atropos[18], and grey and white matter segmentation was performed with SPM (SPM8; Institute of Neurology, University College of London, London, England) implemented in Matlab2009b (The Mathworks Inc, Natick, Mass). The individual MRIs were used for calculation of regional gray matter volume as well as for extraction of region of interest (ROI) signals from the PET data.

ROIs were identified with an automated algorithm previously described elsewhere [19] and cropped for grey matter. Upon manual inspection, significant atrophy of the brain tissue produced gross errors for delineating the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampus and precuneus ROIs. Therefore, for these ROIs, a trained, experienced technician drew each mask using atlas-based approaches on MRI scans [20]. Total intracranial volume was obtained by manually drawing an ROI within the dura matter on individual MRIs that included all supratentorial structures, the cerebral and corpus callosum areas, the parenchymal area and the brain stem area rostral to the opening of the medulla.

[18F] FDG PET acquisition

2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose ([18F]FDG) was purchased from PETNET (Hackensack, NJ, USA). PET images were acquired on an ECAT EXACT HR+ scanner (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville Tenn.). After a transmission scan of 10 minutes, an IV infusion of 5 mCi of [18F]FDG was delivered in an eyes-open resting condition. Dynamic scans were acquired for 60 minutes with 26 frames of increasing duration (8 × .25 minutes, 6 × .5 minutes, 5 × 1 minute, 4 × 5 minutes, 3 × 10 minutes). Images were reconstructed to 128 × 128 matrix (pixel size 2.5 × 2.5 mm2). Reconstruction was performed from transmission data and scatter correction was performed using a model-based approach. The reconstruction and estimated image filters were Shepp 0.5 (2.5 full width half maximum, FWHM), Z filter was all pass 0.4 (2.0 FWHM) and the zoom factor was 4.0, leading to a final image resolution of 5.1 mm FWHM at the center of field of view.

[11C]PIB PET scanning

The full radiosynthesis technique for [N-Methyl 11C]-2-(4-methylaminophenyl)-6-hydroxybenzothiazole ([11C]-6-OH-BTA-1 or [11C]PIB) is reported elsewhere[21]. The average yield was found to be 3.8 μg (SD 1.4) at the end of synthesis with an average specific activity of 12.3 mCi (SD 3.2). PET images were acquired on an ECAT EXACT HR+ (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville Tenn.) at two different imaging sites: 40/96 (41.7%) scans were performed at Weill Cornell Medical Center (WCMC) and 56/96 (58.3%) scans were performed at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC). Mean [11C]PIB BPND, did not differ between sites [22] and the percentage of HCs did not differ between sites: 10/40 (25%) at CUMC and 25/57 (43.9%) at WCMC, p=0.085. After a transmission scan of 10 minutes, [11C]PIB was administered intravenously as a bolus over 30 seconds. Emission data were obtained in 3D mode for 90 minutes, binning over 18 frames of increasing duration (3 × 20 sec, 3 × 1 min, 3 × 2 min, 2 × 5 min and 7 × 10 min). Images were reconstructed to 128 × 128 matrix (pixel size 2.5 × 2.5 mm2). Reconstruction was performed in an identical manner to [18F]FDG data as described above.

PET preprocessing

In order to correct for subject motion, each PET frame was registered to the eighth frame using the FMRIB linear image registration tool (FLIRT), version 5.0 (FMRIB Image Analysis Group, Oxford, UK). Each subject’s mean PET image was co-registered to their T1 image using FLIRT, optimized as previously described[23]. Time activity curves were calculated as the average activity measured across all voxels within each ROI over the time course of the acquisition.

For [18F]FDG, the Standard Uptake Value Relative to the cerebellum (SUVR) was calculated in each ROI as the sum of the [18F]FDG tissue activity between 40 and 60 min after radiotracer injection in the ROI, divided by the same measure in the cerebellum[24].

For [11C]PIB, BPND was calculated for each ROI using the Logan graphical approach and the TAC from the cerebellar gray matter as reference[25]. The t* for the Logan plot was set to be 35 minutes after injection.

Apolipoprotein E genotyping

Blood was stored at the Human Genetics Resources Core at Columbia University and annually sent in a batch to Prevention Genetics (Marshfield, Wisconsin, USA) for identification of apolipoprotein E genotype. Using a standard protocol, DNA was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The genotypes were determined by the sizes of DNA fragments present.

Statistical Methods

Group differences in imaging-based measures between subjects with amnestic MCI and HCs were determined using a linear mixed model analysis with group as a fixed effect and subject as a random effect. For [11C]PIB and [18F]FDG analyses, age was used as a fixed effect. In MRI T1 volumetric analyses, age and total intracranial volume were used as fixed effects. When multiple regions were considered in a single analysis, the analysis was performed on the natural logarithmic of the neuroimaging outcome measure in order to stabilize the variance across regions, and to naturally allow for proportional differences in outcome measures. For the group analysis of MRI data, all medial temporal regions were analyzed together in this way. Standard errors were computed for each PET outcome measure using a bootstrap algorithm that takes into account the errors in brain TACs; observations were weighted accordingly[26].

The analysis of the time to progression to clinical dementia was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model applied only to the MCI patients. A priori ROIs based on regions that have demonstrated consistent differences in AD relative to HC were used for [11C]PIB (precuneus) and [18F]FDG data (parietal cortex)[3, 27]. Each analysis was run with and without sex, age, education level and APOE ε4 carrier status as covariates, as these are known to affect rates of progression to dementia. Each analysis was run in the individual imaging modality first and then the modalities were combined to compare them. To assess discriminatory power of the various proportional hazards models, we calculated the concordance statistic, analogous to Kendall’s tau, for which a value of 1 represents perfect discrimination and a value of 0.5 would indicate that a coin toss would do as well as the model in predicting outcome [28].

Statistical differences of continuous demographic or clinical measures were calculated using the Student’s t-test and categorical data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Significance was defined as P less than 0.05 and all tests were two-sided. SPSS 12 for Mac OSX (www.spss.com) and R (www.R-project.org) were used for calculations.

Results

Demographics

88 subjects with MCI and 40 HCs participated (Table 1). HCs did not differ from MCI subjects in age, sex or education level. MCI subjects who progressed to dementia did not differ from those that did not progress in any of those variables, though the relatively small number of progressors (n=17) limited these statistical analyses. MCI subjects had lower MMSE scores at baseline than HCs, and those that progressed to dementia had lower MMSE scores at baseline than those who did not progress. The number of subjects with [11C]PIB scans, [18F]FDG scans and APOE4 genotyping is included in Table 2; all subjects had MRI scans at baseline. Missing genotypic or neuroimaging data were due to technical problems with acquisition.

Table 1.

Demographic data of subjects in the study.

| HC | MCI | HC v. MCI p value | Non-Progressor to dementia | Progressor to dementia | Progressor v. non-progressor p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Number | 40 | 88 | 63 | 17 | ||

| Age (years) | 67.3 (8.0) | 69.5 (7.5) | 0.13 | 69.51 (7.0) | 68.29 (9.4) | 0.55 |

| Sex (# Female) | 25/40 (62.5%) | 47/88 (53.4%) | 0.44 | 33/63 (52.4%) | 9/17 (52.9%) | 1.00 |

| Education (Years) | 16.8 (2.3) | 15.6 (3.1) | 0.03 | 15.5 (2.9) | 16.6 (3.9) | 0.21 |

| MMSE at Baseline | 29.1 (0.8) | 26.5 (2.4) | 5.9 e-10 | 27.02 (2.2) | 24.5 (2.0) | 5.7 e-5 |

| APOE4 carriers | 9/32 (28.1%) | 28/51 (54.9%) | 0.02 | 18/63 (28.6%) | 7/14 (50%) | 0.21 |

| Time to follow up (Years) | N/A | N/A | 1.91 (0.8) | 1.78 (1.36) | 0.69 | |

Table 2.

Numbers of subjects in the study that had each research measure at baseline

| HC (N=40) | MCI (N=88) | Non-progressor to dementia (N=63) | Progressor to dementia (N=17) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # with MRI | 40 (100%) | 88 (100%) | 63 (100%) | 17 (100%) |

| # with [11C]PIB PET | 35 (87.5%) | 62 (70.4%) | 44 (70%) | 14 (82.4%) |

| # with [18F] FDG PET | 38 (95%) | 76 (86.4%) | 51 (81%) | 17 (100%) |

| # with APOE genotyping | 32 (80%) | 51 (57.9) | 42 (67%) | 14 (82.4%) |

Diagnostic Categorical Differences

MCI subjects had higher [11C]PIB BPND than HCs (F = 14.5; df = 1, 94; p = 2.0 e-4) when using a linear mixed model across all regions with age as a covariate. A significant region by diagnosis interaction was found (F = 6.71; df = 5,475; p = 1.0 e-4). Post hoc analyses without adjustment for multiple comparisons found significant higher [11C]PIB BPND in the cingulate, the parietal cortex, the prefrontal cortex and the precuneus (Supplemental Figure 1). Binding did not differ in the hippocampus or the parahippocampus.

MCI subjects had smaller medial temporal lobe volumes than HCs (F = 12.72; df = 1,123; p = 5.0 e-4) with age, sex and intracranial volume as covariates. A significant region by diagnosis interaction was found (F = 5.71; df = 3,251; p = 9.0 e-4). Post hoc analyses found smaller volume in hippocampus and parahippocampus of MCI subjects when compared to HCs (Supplemental Figure 2). No differences were found in entorhinal cortex.

MCI subjects did not differ from HCs in SUVR of [18F]FDG with age as a covariate (F = 0.01; df = 111; p = 0.92).

Prediction of Progression to Dementia

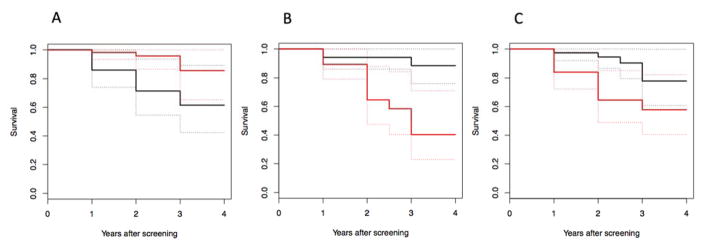

Cox proportional hazards model for time to progression with [11C]PIB BPND in the precuneus at baseline as a predictor was significant (Chi square=10.81, p= 1.0 e-3) with age, sex, education level and APOE4 status as covariates (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of a median split of imaging outcome measure. Black curves are for subjects with greater than the median and red curves are less than the median imaging signal. Dashed lines are the 95% confidence interval lines. A: Higher [11C]PIB binding in the precuneus is associated with greater rates of progression to dementia. B: Lower [18F]FDG SUVR in the parietal cortex is associated with greater rates of progression to dementia. C: Lower hippocampus volume is related to greater rates of progression to dementia.

Cox proportional hazards model for time to progression showed that [18F]FDG uptake in the parietal cortex at baseline was a significant predictor (Chi square=18.37, p=1.8 e-5) with age, sex, education level and APOE4 carrier status as covariates (Figure 1B).

Cox proportional hazards model for time to progression showed MRI-derived hippocampal volume as a significant predictor (Chi square=4.05, p=0.044) with age, sex, education level, total intracranial volume and APOE4 carrier status as covariates (Figure 1C).

Cox proportional hazards models were run inputting the three outcome measures in one model in a step-wise fashion ([11C]PIB chi square=9.7, p=1.8 e-3; [18F]FDG chi square=10.0, p=1.6 e-3; hippocampus volume chi square=1.4, p=0.24). This algorithm only included subjects with data from all three imaging modalities. This model was iterated to enter the variables in different orders. Whenever [18F]FDG uptake was entered into the model after [11C]PIB BPND, it remained significant to predict progression. The reciprocal was also true. These data suggest that the two PET imaging outcome measures had independent predictive value. Whenever hippocampus volume was entered into the model after [18F]FDG data, it did not remain significant, but [18F]FDG data remained significant when entered after the hippocampus volume. This result suggests that the predictive power of the hippocampus volume did not add to that of the [18F]FDG data. Lastly, when the hippocampus volume was entered into the model after [11C]PIB BPND, it remained significant and the reciprocal was true, indicating that hippocampus volume and [11C]PIB BPND had independent predictive power.

The proportional hazards model with [18F]FDG SUVR as predictor showed the best predictive performance (concordance 0.807), followed by [11C]PIB BPND (concordance 0.771), followed by hippocampus volume (concordance 0.726).

Discussion

Our results indicate that PET imaging with [11C]PIB using the outcome measure BPND, and PET imaging with [18F]FDG using the outcome measure SUVR, have independent predictive properties of progression to dementia in MCI. Hippocampus volume did not add predictive power to signal from [18F]FDG SUVR and was less significantly predictive of progression than either [11C]PIB BPND or [18F]FDG SUVR. Concordance analyses indicated [18F]FDG SUVR to be the strongest predictor, followed by [11C]PIB BPND and then hippocampus volume. We also found greater brain [11C]PIB BPND and smaller hippocampal volumes in MCI relative to HCs. The number of patients who progressed from MCI to dementia was relatively low due to limited follow-up duration.

One previous study, which directly compared these imaging modalities to predict progression to dementia using the ADNI dataset [13], contrasted to ours in that it reported lower hippocampus volume as a better predictor of progression than either [18F]FDG or [11C]PIB PET imaging. A different study of the ADNI dataset found that [18F]FDG was more effective at predicting progression to AD from MCI than either [18F]Florbetapir PET or MRI [16]. Their results paralleled ours in that the structural MRI data was not as effective as the PET imaging. A different study with a limited sample size found that [18F]FDG and [11C]PIB imaging predicted progression but hippocampus volume did not, more consistent with our results [15]. Another study based on the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging focused on the effect of age on the neuroimaging data [14]. The results of such study are not directly comparable to ours, as they combined MRI volume, cortical thickness and [18F]FDG together into a neurodegeneration factor, which was used as a biomarker to predict progression to dementia. This neurodegeneration factor was almost always required for progression to dementia in that study. Discrepancies between these and our study may be explained either by differences in definitions of MCI, or in variability in observation length after imaging.

A meta-analysis of studies that used both [18F]FDG and MRI hippocampus volume data reported a better prediction of progression to dementia with [18F]FDG than hippocampus volume, consistent with our results[29].

A previous study of both [18F]FDG and [11C]PIB found that the data from these imaging modalities did not correlate with each other over time[30]. This is consistent with our data, suggesting an independent role of these two biomarkers in predicting progression to dementia. Our results also confirm the handful of studies that have reported greater [11C]PIB BPND and lower hippocampus volume in MCI compared to HCs [24, 29, 31, 32]. Some previous studies have reported lower cerebral metabolic rate in the brain of MCI subjects when compared to HCs as measured by [18F]FDG imaging [3, 33], but other reports found no differences in MCI [34, 35]. In our dataset, we did not find group differences between MCI and HCs. The variation in the literature can be explained by the heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s Disease etiology. For example, cognitive reserve capacity is thought to compensate for brain pathology [36], or cormorbid vascular disease could contribute to such differences.

Our a priori outcome measure for [11C]PIB was BPND, but other groups have used SUVR. When we calculated SUVR in our data, the values were highly correlated with BPND (Pearson’s r=0.92). Based on this linear correlation, the median cutoff value of BPND used in Figure 1 is equivalent to an SUVR value of 1.465.

Beta amyloid imaging with PET has been sensitive to predict progression to AD from MCI, but with lower specificity. For example, in a recent Cochrane review article, it was estimated that for every 100 subjects with a [18F]PIB scan, only 1 with low [18F]PIB values would be inaccurately considered a non-progressor to dementia, but 28 subjects with high [18F]PIB values would be inaccurately considered a progressor to dementia [7]. This lower sensitivity is due to clinically insignificant beta amyloid accumulation in some healthy individuals with age. Previous studies on the sequence of molecular changes that occur during the development of dementia indicate that brain beta amyloid accumulates first in the asymptomatic stage, and that metabolic and structural changes occur later in the course of the disorder [37]. Our data suggest that combining either [18F]FDG or hippocampal volume with [18F]PIB improves the prediction of progression to dementia. This can be explained by a model in which those subjects with [18F]FDG differences or hippocampus volume changes were those subjects whose beta-amyloid accumulation impacted the structure or function of the brain.

Our results may have significance to future clinical trials. Medications approved for AD, including cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, do not alter the poor long-term prognosis [38]. Recently, a number of medications have been investigated to decrease amyloid deposits in the brain, and thus reverse the amyloid pathology. AD subjects did demonstrate diminished amyloid deposits with these medications, but the medications did not reverse the cognitive deficits of the disorder [39–41]. Our results suggest that PET imaging with [18F]FDG would help in future clinical trials to select subjects with elevated [11C]PIB binding who would most likely benefit from the medications, due to the fact that the AD pathology has an impact on their brain metabolic rate. The medications may, in turn, prove to be more effective in that high-risk population. Arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI (ASL) is a noninvasive technique that measures brain perfusion that often correlates with brain glucose metabolic rate. ASL has less cost to PET imaging and minimal risk to patients. It is possible that ASL could be used as a substitute to [18F]FDG imaging for clinical purposes [42].

Other classes of biomarkers have been investigated to predict the progression to dementia, including cerebrospinal fluid AB1-42, tau and phospho tau protein [27] and the apolipoprotein E e4 (APOE e4) allele [43]. Our study did not collect cerebrospinal fluid or genetic samples from all subjects, so a comparison between these and the neuroimaging data could not be made. Future studies that include these markers in combination with multimodal imaging would help to clarify further their relative predictive properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participants in the study. We appreciate the helpful discussions with Martin Schain during revision of the manuscript. This study was funded through National Institute of Health (R01AG017761, R01AG041795, and K23MH105688).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosure Statement: ML received salary support from a medical education grant from Sunovian Pharmaceuticals unrelated to this project. JM’s wife’s family own stock in Johnson & Johnson unrelated to this project. DP receives salary support from a grant from Avanir and is a consultant for Astellas, Abbvie, Eisai and Genentech.

References

- 1.Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, de Strooper B, Frisoni GB, Salloway S, Van der Flier WM. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He W, Liu D, Radua J, Li G, Han B, Sun Z. Meta-analytic comparison between PIB-PET and FDG-PET results in Alzheimer’s disease and MCI. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;71:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devanand DP, Bansal R, Liu J, Hao X, Pradhaban G, Peterson BS. MRI hippocampal and entorhinal cortex mapping in predicting conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1622–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devanand DP, Pradhaban G, Liu X, Khandji A, De Santi S, Segal S, Rusinek H, Pelton GH, Honig LS, Mayeux R, Stern Y, Tabert MH, de Leon MJ. Hippocampal and entorhinal atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: prediction of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68:828–836. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256697.20968.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Zhang S, Li J, Zheng DM, Guo Y, Feng J, Ren WD. Predictive accuracy of amyloid imaging for progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease with different lengths of follow-up: a meta-analysis. [Corrected] Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e150. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang S, Smailagic N, Hyde C, Noel-Storr AH, Takwoingi Y, McShane R, Feng J. (11)C-PIB-PET for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010386. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010386.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frisoni GB, Bocchetta M, Chetelat G, Rabinovici GD, de Leon MJ, Kaye J, Reiman EM, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Black SE, Brooks DJ, Carrillo MC, Fox NC, Herholz K, Nordberg A, Jack CR, Jr, Jagust WJ, Johnson KA, Rowe CC, Sperling RA, Thies W, Wahlund LO, Weiner MW, Pasqualetti P, Decarli C Area ISsNPI. Imaging markers for Alzheimer disease: which vs how. Neurology. 2013;81:487–500. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829d86e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smailagic N, Vacante M, Hyde C, Martin S, Ukoumunne O, Sachpekidis C. (1)(8)F-FDG PET for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD010632. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010632.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowe CC, Bourgeat P, Ellis KA, Brown B, Lim YY, Mulligan R, Jones G, Maruff P, Woodward M, Price R, Robins P, Tochon-Danguy H, O’Keefe G, Pike KE, Yates P, Szoeke C, Salvado O, Macaulay SL, O’Meara T, Head R, Cobiac L, Savage G, Martins R, Masters CL, Ames D, Villemagne VL. Predicting Alzheimer disease with beta-amyloid imaging: results from the Australian imaging, biomarkers, and lifestyle study of ageing. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:905–913. doi: 10.1002/ana.24040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ong KT, Villemagne VL, Bahar-Fuchs A, Lamb F, Langdon N, Catafau AM, Stephens AW, Seibyl J, Dinkelborg LM, Reininger CB, Putz B, Rohde B, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Abeta imaging with 18F-florbetaben in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective outcome study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:431–436. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Xu YC, O’Brien PC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Boeve BF, Waring SC, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Prediction of AD with MRI-based hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 1999;52:1397–1403. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trzepacz PT, Yu P, Sun J, Schuh K, Case M, Witte MM, Hochstetler H, Hake A Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Comparison of neuroimaging modalities for the prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jack CR, Jr, Therneau TM, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Lowe VJ, Mielke MM, Vemuri P, Roberts RO, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Rocca WA, Petersen RC. Transition rates between amyloid and neurodegeneration biomarker states and to dementia: a population-based, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:56–64. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00323-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruck A, Virta JR, Koivunen J, Koikkalainen J, Scheinin NM, Helenius H, Nagren K, Helin S, Parkkola R, Viitanen M, Rinne JO. [11C]PIB, [18F]FDG and MR imaging in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1567–1572. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu L, Wu X, Li R, Chen K, Long Z, Zhang J, Guo X, Yao L Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Prediction of Progressive Mild Cognitive Impairment by Multi-Modal Neuroimaging Biomarkers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51:1045–1056. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devanand DP, Schupf N, Stern Y, Parsey R, Pelton GH, Mehta P, Mayeux R. Plasma Abeta and PET PiB binding are inversely related in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2011;77:125–131. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318224afb7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Wu J, Cook PA, Gee JC. An open source multivariate framework for n-tissue segmentation with evaluation on public data. Neuroinformatics. 2011;9:381–400. doi: 10.1007/s12021-011-9109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milak MS, DeLorenzo C, Zanderigo F, Prabhakaran J, Kumar JS, Majo VJ, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. In vivo quantification of human serotonin 1A receptor using 11C-CUMI-101, an agonist PET radiotracer. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1892–1900. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.HD . The Human Brain. Surface, Three-Dimensional Sectional Anatomy and MRI. Springer-Verlag Wien; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsey RV, Sokol LO, Belanger MJ, Kumar JS, Simpson NR, Wang T, Pratap M, Van Heertum RL, John Mann J. Amyloid plaque imaging agent [C-11]-6-OH-BTA-1: biodistribution and radiation dosimetry in baboon. Nucl Med Commun. 2005;26:875–880. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN, Holden J, Houle S, Huang SC, Ichise M, Iida H, Ito H, Kimura Y, Koeppe RA, Knudsen GM, Knuuti J, Lammertsma AA, Laruelle M, Logan J, Maguire RP, Mintun MA, Morris ED, Parsey R, Price JC, Slifstein M, Sossi V, Suhara T, Votaw JR, Wong DF, Carson RE. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeLorenzo C, Kumar JS, Zanderigo F, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Modeling considerations for in vivo quantification of the dopamine transporter using [(11)C]PE2I and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1332–1345. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devanand DP, Mikhno A, Pelton GH, Cuasay K, Pradhaban G, Dileep Kumar JS, Upton N, Lai R, Gunn RN, Libri V, Liu X, van Heertum R, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Pittsburgh compound B (11C-PIB) and fluorodeoxyglucose (18 F-FDG) PET in patients with Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy controls. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2010;23:185–198. doi: 10.1177/0891988710363715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:834–840. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogden RT, Tarpey T. Estimation in regression models with externally estimated parameters. Biostatistics. 2006;7:115–129. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan TK, Alkon DL. Alzheimer’s Disease Cerebrospinal Fluid and Neuroimaging Biomarkers: Diagnostic Accuracy and Relationship to Drug Efficacy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:817–836. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB. Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med. 2004;23:2109–2123. doi: 10.1002/sim.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan Y, Gu ZX, Wei WS. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron-emission tomography, single-photon emission tomography, and structural MR imaging for prediction of rapid conversion to Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:404–410. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kemppainen N, Joutsa J, Johansson J, Scheinin NM, Nagren K, Rokka J, Parkkola R, Rinne JO. Long-Term Interrelationship between Brain Metabolism and Amyloid Deposition in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48:123–133. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemppainen NM, Aalto S, Wilson IA, Nagren K, Helin S, Bruck A, Oikonen V, Kailajarvi M, Scheinin M, Viitanen M, Parkkola R, Rinne JO. PET amyloid ligand [11C]PIB uptake is increased in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68:1603–1606. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260969.94695.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okello A, Koivunen J, Edison P, Archer HA, Turkheimer FE, Nagren K, Bullock R, Walker Z, Kennedy A, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Rinne JO, Brooks DJ. Conversion of amyloid positive and negative MCI to AD over 3 years: an 11C-PIB PET study. Neurology. 2009;73:754–760. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b23564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karow DS, McEvoy LK, Fennema-Notestine C, Hagler DJ, Jr, Jennings RG, Brewer JB, Hoh CK, Dale AM Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Relative capability of MR imaging and FDG PET to depict changes associated with prodromal and early Alzheimer disease. Radiology. 2010;256:932–942. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jagust WJ. Functional imaging patterns in Alzheimer’s disease. Relationships to neurobiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:30–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosconi L. Brain glucose metabolism in the early and specific diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. FDG-PET studies in MCI and AD. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:486–510. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1762-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, Tang MX, Wilder D, Mayeux R. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA. 1994;271:1004–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen AD, Klunk WE. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using PiB and FDG PET. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;72(Pt A):117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kulshreshtha A, Piplani P. Current pharmacotherapy and putative disease-modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2625-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, Kieburtz K, He F, Sun X, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Siemers E, Sethuraman G, Mohs R Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Steering C, Semagacestat Study G. A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M, Sabbagh M, Honig LS, Porsteinsson AP, Ferris S, Reichert M, Ketter N, Nejadnik B, Guenzler V, Miloslavsky M, Wang D, Lu Y, Lull J, Tudor IC, Liu E, Grundman M, Yuen E, Black R, Brashear HR, Bapineuzumab Clinical Trial I. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, Kieburtz K, Raman R, Sun X, Aisen PS, Siemers E, Liu-Seifert H, Mohs R Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Steering C, Solanezumab Study G. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:311–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Wolk DA, Reddin JS, Korczykowski M, Martinez PM, Musiek ES, Newberg AB, Julin P, Arnold SE, Greenberg JH, Detre JA. Voxel-level comparison of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI and FDG-PET in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:1977–1985. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823a0ef7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michaelson DM. APOE epsilon4: the most prevalent yet understudied risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.