Summary

The intestinal lamina propria (LP) contains antigen‐presenting cells with features of dendritic cells and macrophages, collectively referred to as mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs). Association of MNPs with the epithelium is thought to play an important role in multiple facets of intestinal immunity including imprinting MNPs with the ability to induce IgA production, inducing the expression of gut homing molecules on T cells, facilitating the capture of luminal antigens and microbes, and subsequent immune responses in the mesenteric lymph node (MLN). However, the factors promoting this process in the steady state are largely unknown, and in vivo models to test and confirm the importance of LP‐MNP association with the epithelium for these outcomes are unexplored. Evaluation of epithelial expression of chemoattractants in mice where MNP–epithelial associations were impaired suggested CCL20 as a candidate promoting epithelial association. Expression of CCR6, the only known receptor for CCL20, was required for MNPs to associate with the epithelium. LP‐MNPs from CCR6−/− mice did not display defects in acquiring antigen and stimulating T‐cell responses in ex vivo assays or in responses to antigen administered systemically. However, LP‐MNPs from CCR6‐deficient mice were impaired at acquiring luminal and epithelial antigens, inducing IgA production in B cells, inducing immune responses in the MLN, and capturing and trafficking luminal commensal bacteria to the MLN. These findings identify a crucial role for CCR6 in promoting LP‐MNPs to associate with the intestinal epithelium in the steady state to perform multiple functions promoting gut immune homeostasis.

Keywords: bacteria, dietary antigen, intestine, mononuclear phagocyte

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- EA

epithelium‐associated

- GI

gastrointestinal

- LP

lamina propria

- LTβR

lymphotoxin β receptor

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- MNP

mononuclear phagocyte

- OVA

ovalbumin

Introduction

The primary function of the luminal gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the absorption of nutrients, necessitating that the expansive surface of the GI tract epithelium be exposed to a wide array of environmental substances including food, commensal organisms and potential pathogens. The lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MPNs) of the immune system underlying the epithelium of the GI tract continually monitor the luminal contents to promote appropriate immune responses and maintain homeostasis. The current perception is that LP‐MNPs need to closely associate with the epithelium to sample the luminal contents, become imprinted by epithelial cell interactions, and induce immune responses to luminal antigens in the draining mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN). However, despite the importance of these processes, little is known about the factors promoting LP‐MNPs to associate with the epithelium, and in vivo models to test the importance of MNP–epithelium associations in surveillance and imprinting are lacking.

The LP underlies the single‐cell layer epithelium and contains a large population of myeloid derived (CD11b+ CD11c+ MHCII+) MNPs.1, 2 MNPs expressing the integrin α E, or CD103+, have the phenotype of dendritic cells (DCs) and can be positioned with significant portions of their cell body within the small intestinal villous epithelium and acquire luminal substances.3, 4, 5 In addition, in vitro studies have shown that intestinal epithelial cells can imprint DCs to express aldehyde dehydrogenase 1,6, 7 which is necessary for the production of all‐trans retinoic acid, the biologically active vitamin A metabolite inducing IgA production by B cells and gut‐homing molecule expression by responding lymphocytes.8, 9, 10 These observations imply that LP‐DCs physical association with the epithelium is important for these processes. In contrast, LP‐MNPs expressing the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 have properties resembling macrophages, and have been demonstrated to extend dendrites into the lumen to acquire luminal antigens, and to capture luminal bacteria and carry them to the MLN.11 Epithelial expression of fractalkine, or CX3CL1, the ligand for CX3CR1, plays a role in the extension of dendrites into the lumen by CX3CR1+ LP‐MNPs, as loss of CX3CL1 impaired this process in response to Aspergillus conidia,12 and deletion of CX3CR1 decreased the number of dendrites extended into the lumen in the proximal ileum by CX3CR1+ LP‐MNPs.11, 13 Studies have found that capture of luminal bacteria and carriage to the draining MLN by LP‐MNPs is impaired in the absence of CX3CR1.11, 14, 15 However, other studies have demonstrated that luminal antigen uptake by CX3CR1+ LP‐MNPs and subsequent T‐cell responses in the MLN are not impaired in the absence of CX3CR1,16 indicating no role, or a limited role, for CX3CR1 and CX3CL1 in the acquisition of soluble luminal antigens and suggesting that the lack of CX3CR1 or CX3CL1 may confer other defects on immune responses. In contrast to observations suggesting a role for CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 in facilitating LP‐MNPs to sample the luminal contents, studies have not identified factors promoting CD103+ LP‐MNPs to associate with the villous epithelium, making it difficult to test the importance of epithelial association for imprinting and acquisition of luminal antigen in the steady state. Here, we explored this process and identify that CCR6 facilitates epithelial association and luminal antigen acquisition by both CD103+ and CD103− LP‐MNPs and that impairing epithelial association results in the loss of responses to luminal antigens in the MLN, impaired imprinting of CD103+ LP‐MNPs, and the inability to capture and traffic commensal bacteria to the MLN. These studies demonstrate an unappreciated role for CCR6 in intestinal immune surveillance at the villous epithelium in the steady state and document the in vivo importance of epithelium–MNP interactions promoting homeostasis.

Materials and methods

Mice

All knockout and reporter mice used in these studies were on the C57BL/6 background. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD) or The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MN). OTI T‐cell receptor transgenic mice,17 OTII T‐cell receptor transgenic mice,18 CD11cYFP transgenic mice,19 and CX3CR1GFP mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) knockout mice20 and CCR6 knockout mice21 were bred and maintained in‐house. Animals were housed in a specific pathogen‐free facility and fed routine chow diet. Animals were 6–16 weeks of age at the time of analysis unless noted otherwise. In some experiments mice were treated with either 100 μg human immunoglobulin (Hum‐Ig; Innovative Research, Inc., Novi, MI) or 100 μg LTβR immunoglobulin (LTβR‐Ig) intraperitoneally 4 days before analysis. LTβR‐Ig was produced as previously described.22 Procedures and protocols were carried out in accordance with the institutional review board at Washington University School of Medicine.

Isolation of cell populations and flow cytometric sorting

Small intestines were harvested, rinsed with PBS, and the Peyer's patches (PP) were removed. Epithelium‐associated (EA) MNPs were released by incubating for 15 min twice in a 37° rotating incubator in Hanks’ balanced salt solution medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) containing 5 mm EDTA as previously described.4 The second incubation, which contained > 90% of the MNPs released with the epithelium,4 was used for analysis. After a third incubation with Hanks’ balanced salt solution medium with 5 mm EDTA, isolation of LP cellular populations was performed as previously described.4 Cellular suspensions were then passed through a 70‐μm nylon filter and the cells were prepared for flow cytometric analysis or sorting. Antibodies used for analysis are listed in the Supplementary material (Table S1). MNP subpopulations were identified as 7AAD−, CD45+, CD11c+, CD11b+, MHCII+ and either CD103+ or CD103− for flow cytometric sorting. Analysis of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity was performed using the Aldefluor assay (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) per the manufacturer's recommendations as previously described.4

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry on frozen sections was performed as previously described.4 Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are listed in the Supplementary material (Table S1). Monochrome fluorescent images were obtained with an axioskop 2 microscope and each channel was pseudocoloured using axiovision software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY). Cytospins of LP‐MNPs were evaluated for the presence of cytokeratin 18 as previously described.5

PCR arrays and quantitative real‐time PCR assay

RNA was extracted from cellular populations isolated as above, treated with DNAse, and transcribed into cDNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The expression of 84 genes encoding targets relevant to chemotaxis was evaluated using the RT2 PCR array system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The absolute copy number of the target was calculated from standards that were constructed as previously described.23 Primers used for RT‐PCR are described in the Supplementary material (Table S2).

Ex vivo analysis of luminal antigen delivery to LP‐MNPs

To evaluate the acquisition of fluorescent luminal protein, mice were gavaged with 250 μg ovalbumin (OVA)‐647 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and killed 2 hr later; LP cellular populations were isolated from the non‐follicle‐bearing LP as previously described23 and analysed by flow cytometry. To evaluate for intrinsic defects in antigen acquisition, LP‐MNPs were isolated and cultured as previously described24 in the presence of OVA‐647 for 30 min and analysed by flow cytometry. To evaluate if antigen captured by LP‐MNPs was effective at inducing T‐cell responses, mice were anaesthetized and 2 mg of OVA (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO) dissolved in PBS, or PBS alone (controls), was injected into the lumen of the intestine. Two hours after the administration of OVA, cell populations were isolated from the non‐follicle‐bearing LP as previously described23 and sorted by flow cytometry. Sorted DC populations were cultured with flow cytometry‐sorted CSFE‐labelled CD3+ CD8α+ Vα2+ Vβ5+ splenic T cells from OTI T‐cell receptor transgenic mice or CD3+ CD4+ Vβ5+ splenic T cells from OTII T‐cell receptor transgenic mice at a ratio of 1 : 10 MNPs to T cells. As a positive control, 20 μg of OVA was added to cultures of DC populations isolated from mice receiving luminal PBS. After 3 days, cultures were evaluated for the number of T cells by flow cytometry and cell counting as previously described.5

Analysis of bacterial translocation

Evaluation of bacterial translocation to the MLN was performed as previously described.15, 25 Mice were gavaged with 500 mg ampicillin, 500 mg metronidazole, 500 mg neomycin and 250 mg vancomycin and colon‐draining MLNs were isolated 4 days later. To quantify bacteria, single‐cell suspensions of MLNs were cultured on Luria–Bertani agar plates overnight at 37° and individual colonies counted.

In vitro co‐cultures of sorted LP‐MNPs and B cells

Flow cytometrically sorted LP‐MNP subtypes were cultured at a 1 : 1 ratio (3 × 104 cells each) with flow cytometrically sorted splenic CD19+ IgM+ B cells in RPMI media containing 10% fetal calf serum, 5 × 10−5 m 2‐mercaptoethanol, 2 mm l‐glutamine, 10 mm HEPES, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 1 mm sodium pyruvate at 37° in 5% CO2 in the presence of 5 μg/ml anti‐CD40 (Axxora, San Diego, CA). After 6 days of culture the concentration of IgA was measured by ELISA as previously described.22

Adoptive transfers and evaluation of antigen‐specific responses to oral or systemic antigen in the MLN

Mice were injected with 1 × 107 CD4+ magnetically negative selected (EasySep, StemCell Technologies) CSFE‐labelled OVA‐specific splenic T cells from OTII T‐cell receptor transgenic mice. Twenty‐four hours later mice were gavaged with 100 mg OVA (Sigma Aldrich), or given an injection of 5 mg OVA intravenously. Forty‐eight hours after OVA administration, mice were killed and the proliferation of OVA‐specific T cells was evaluated by flow cytometry gating on CD3+ Vα2+ Vβ5+ CSFE‐labelled cells isolated from the MLN.

Gentamicin protection assay

Flow cytometrically sorted LP‐MNP subtypes were cultured at a density of 4·5 × 105 cells/ml. Either 3 × 1010 Salmonella typhimurium wild‐type strain SB300A1,26 or its isogenic invasion‐deficient mutant ΔInv, was added to the cell cultures and incubated for 30 min. The cultures were treated with 500 μg/ml gentamicin for 90 min, washed, and fresh media containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin was added. Cultures were harvested at 24 hr and the presence of live bacteria was evaluated by growth on Luria–Bertani agar plates following lysis with 1% Triton X‐100 in Luria–Bertani medium.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis using a Student's t‐test or a one‐way analysis of variance with a Dunnett's post comparison test was performed using graphpad prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). PCR array analysis was performed using the RT2 PCR profiler software (Qiagen). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0·05.

Results

Epithelial expression of CCL20 and its receptor CCR6 are candidates for promoting LP‐MNP association with the epithelium

Dendritic cells have been shown to reside near or within the villous epithelial layer of the small intestine, with significant portions of their cell bodies lying at or above the basement membrane.3, 4, 27 Moreover, macrophages have been described as extending portions of their cell body through the fenestrated basement membrane to come into contact with the villous epithelium.28, 29 These observations suggest that at least two subsets of MNPs may have physical contact with the villous epithelium. To evaluate these populations we removed the epithelium from the non‐PP‐bearing small intestine by treatment with EDTA, a process that has been demonstrated in other studies to be selective for isolating haematopoietic cell populations associating with the epithelium and not those of the lamina propria.30 This approach left the underlying basement membrane and LP intact, including the LP‐MNP population, as determined by immunofluorescence for CD11c and the basement membrane marker CD49f (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1a). Consistent with previous reports, analysis of the live cellular population released with the epithelium revealed the presence of haematopoietic (CD45+) cells expressing CD11c, MHCII and CD11b (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1b,c),1, 3, 4 collectively referred to as MNPs. This population could be divided based upon the expression of CD103 (Fig. S1d). Evaluation of CX3CR1GFP reporter mice revealed that the CD103− EA population expressed CX3CR1, whereas the CD103+ EA population was largely CX3CR1− (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1e), consistent with previous observations of LP‐MNPs isolated with the epithelium.1, 3, 4 The two EA CD11b+ CD11c+ MHCII+ MNP subpopulations expressed similar levels of the co‐stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1f,g). The CD103+ population expressed low levels and the CD103− population expressed higher levels of signal regulatory protein‐α (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1h). Analysis of the EA and LP cellular populations from the same intestine of CX3CR1GFP reporter mice using the same gating strategy revealed that the EA population was devoid of CX3CR1hi CD64hi cells, which were easily identified in the LP (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1i), indicating that the EA‐MNP population did not contain macrophages and that the population isolated with the epithelium was not a random sampling of the LP cellular population.

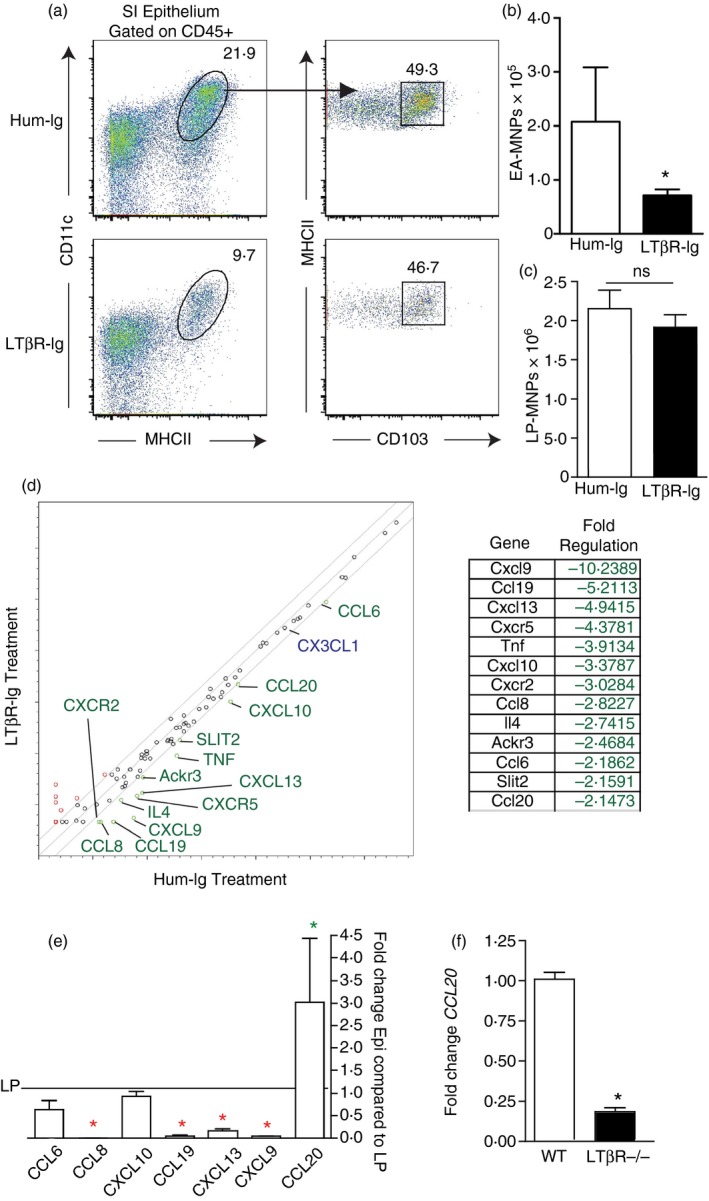

Mice deficient in the LTβR have a diminished population of EA‐MNPs.4 This could arise due to decreased production of chemokines downstream of LTβR signalling in epithelial cells, as LTβR signaling in epithelial cells induces the production of multiple chemokines,31, 32 or alternatively, could result from developmental defects related to the roles the LTβR plays in development in early life.20, 33, 34, 35 To help exclude the latter possibility, we treated mice with a single injection of either Hum‐Ig or LTβR‐Ig fusion protein to transiently block LTβR signalling,22 and evaluated the small intestine MNP populations isolated with the villous epithelium and LP. Mice treated with transient LTβR blockade had a significantly diminished population of CD11c+ MHCII+ cells isolated with the epithelium when compared with Hum‐Ig‐treated controls (Fig. 1a,b). LTβR‐Ig blockade did not skew the ratio of CD103+ to CD103− cells in the population, indicating that it affected both MNP populations (Fig. 1a). Notably, LP‐MNPs were unaffected by LTβR‐Ig treatment (Fig. 1c). This indicates that LTβR blockade primarily blocked interactions of the LP‐MNPs with the epithelium as opposed to global recruitment to the intestine, and suggests that epithelial factors downstream of LTβR signalling promote LP‐MNP association with the small intestine villous epithelium in the steady‐state.

Figure 1.

Identification of CCL20 as a candidate to promote lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) to associate with the small intestine (SI) epithelium. (a) Flow cytometry plots of the CD45+ MHCII+ CD11c+ CD103+ and CD103− MNP population released with the SI epithelium in human‐Ig‐treated or lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) ‐Ig‐treated mice. (b, c) Quantification of the MNPs released with (b) SI epithelium or (c) the SI LP in human‐Ig‐treated or LTβR‐Ig‐treated mice reveals a significant decrease in the MNP population release with the epithelium but not the LP following LTβR‐Ig treatment. (d) Real‐time PCR array for > 80 targets associated with chemotaxis performed on the SI epithelium isolated from human‐Ig or LTβR‐Ig‐treated mice revealed that 13 targets were significantly decreased by LTβR‐Ig treatment. Targets with a greater than twofold change are indicated in green. CX3CL1, a chemokine implicated in promoting MNP interactions with the epithelium was not changed, indicated in blue. (e) Real‐time PCR of SI epithelium and LP reveals that of the seven chemokines whose epithelial expression was decreased by LTβR‐Ig, only one, CCL20, is expressed at a significantly greater level in the epithelium when compared with the LP. (f) Real‐time PCR of SI epithelium demonstrates a decrease in CCL20 expression in LTβR‐deficient mice. (a) Representative of one of three independent replicates. n = 3 for (b, c, e, and f), panel (d) shows combined data from three independent replicates. *P < 0·05, ns = not significant, green * indicates significantly increased expression in the epithelium, red * indicates significantly increased expression in the LP. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We compared the expression of chemotactic factors in the small intestine epithelium of Hum‐Ig‐treated and LTβR‐Ig‐treated mice using a real‐time PCR array. Of the ~80 targets evaluated, 13 showed a greater than twofold decrease in epithelial expression in response to LTβR‐Ig treatment, and seven of these targets were chemokines (Fig. 1d). Of note CX3CL1, a target that has been proposed to facilitate interactions of CX3CR1+ CD103− MNPs with the epithelium, was expressed at high level in the epithelium, but was not altered by LTβR‐Ig treatment (Fig. 1d). We reasoned that a chemokine gradient would be required to promote LP‐MNPs to interact with the epithelium and therefore the most relevant targets for mediating MNP–epithelial association would be chemokines that had higher epithelial expression relative to expression within the LP. Of the chemokine targets, only CCL20 expression was significantly higher in the epithelium compared with the LP (Fig. 1e), further suggesting that it may have a role in recruiting cellular populations to the villous epithelium. Furthermore, we observed that CCL20 expression was significantly reduced in the epithelium of LTβR‐deficient mice (Fig. 1f), consistent with the previously reported loss of EA‐MNPs in LTβR‐deficient mice.4

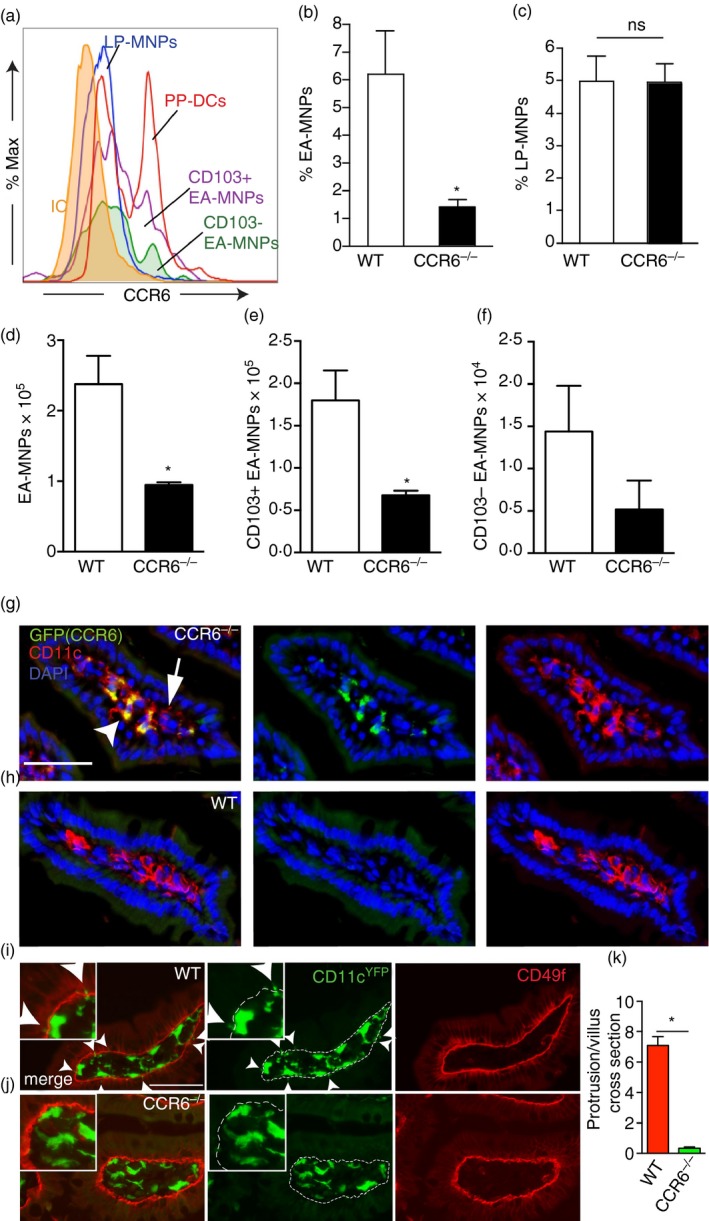

The DCs residing in the PP express high levels of CCR6,36 the only known receptor for CCL20,37 which plays an important role in recruiting DCs to the PP follicle associated epithelium.36 In contrast, reports of CCR6 expression by LP‐MNPs has varied, with some studies concluding that LP‐MNPs lack CCR6 expression and others reporting low levels of CCR6 expression.3, 36 We observed that LP‐MNPs expressed lower, but detectable levels of CCR6, when compared with PP DCs (Fig. 2a). Moreover, both EA‐MNPs subsets, expressed CCR6 at slightly higher levels than LP‐MNPs (Fig. 2a), with the CD103+ population expressing higher levels than the CD103− population. Importantly, CCR6 was necessary for the epithelial localization of MNPs within the intestine, as mice deficient in CCR6 had diminished EA‐MNPs, but not LP‐MNPs (Fig. 2b–f). Examination of fixed tissue sections from CCR6GFP/GFP (CCR6−/−) mice revealed that the small intestine LP contained CD11c+ cells that expressed CCR6 (Fig. 2g,h), confirming that cells in the villi contributed to the CCR6‐expressing MNP population. Moreover, consistent with analysis by flow cytometry, the LP contained both CCR6+ and CCR6− CD11c+ populations (Fig. 2g,h). To evaluate if deficiency of CCR6 resulted in differential localization of CD11c+ cells within the LP, we evaluated the intestine of CCR6−/− CD11cYFP and wild‐type CD11cYFP mice. Consistent with the analysis by flow cytometry, we did not observe a decrease in CD11c+ cells in the LP of CCR6−/− mice. However, we observed that wildtype mice had significantly more CD11c+ cells protruding dendrites or portions of their cell body above the CD49f+ basement membrane (Fig. 2i–k), indicating that CCR6 was promoting interactions with the epithelium. We never observed CD11c+ cells extending dendrites into the lumen in wildtype or CCR6−/− mice, consistent with prior observations that this is a rare event in the steady state when the mucus barrier is intact.25

Figure 2.

CCR6 is expressed by mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs) and is required for their association with the epithelium. (a) Flow cytometry histogram demonstrating CCR6 expression by Peyer's patch dendritic cells (PP DCs), lamina propria (LP) ‐MNPs, and epithelium‐associated (EA) ‐ MNPs. Quantification of the percentage of (b) EA ‐ MNPs and (c) LP‐MNPs in wild‐type (WT) or CCR6−/− mice. Absolute numbers of (e) CD103+ and (f) CD103− EA‐MNP populations in WT or CCR6−/− mice. (g and h) Photomicrographs of fixed tissue sections of small intestine from CCR6GFP/GFP or WT mice demonstrate CD11c+ cells (red) in the LP express CCR6 (white arrow head) and do not express CCR6 (white arrow; green); blue = DAPI nuclear stain. Sections from WT mice demonstrate lack of GFP expression. (i and j) Photomicrographs of small intestine sections from WT CD11cYFP and CCR6−/− CD11cYFP reporter mice stained with CD49f (red) to mark the basement membrane, demonstrates an increased number of CD11cYFP+ cells extending protrusions (white arrow heads) through the CD49f basement membrane in wild‐type mice. (k) Quantitative analysis of the number or CD11cYFP+ protrusions above the basement membrane in wild‐type and CCR6−/− CD11cYFP reporter mice. n = 3 or more mice for a–f, n = 3 mice in panels (g) and (h), n = >35 villus sections from two mice of each genotype for (i–k), scale bars = 50 μm, *P < 0·05, ns = not significant. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

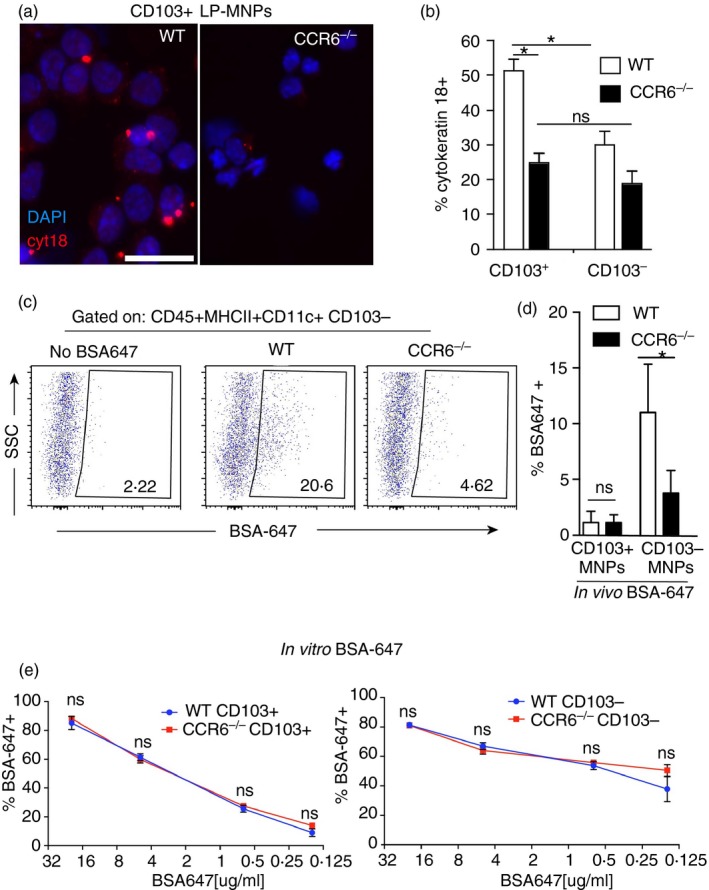

In the absence of CCR6, LP‐MNPs have reduced acquisition of luminal antigens and epithelial cell proteins

CD103+ LP‐DCs can contain epithelial cell proteins, as evidenced by the presence of epithelial cell‐expressed cytokeratin 18 within the DCs, despite the lack of detectable cytokeratin 18 expression by DCs at the RNA level.5 We tested whether LP‐MNPs in CCR6−/− mice had reduced capacity to capture epithelial proteins, by performing cytospins of LP‐DCs isolated from CCR6−/− and wild‐type mice and staining for cytokeratin 18. Cytokeratin 18 staining was significantly less frequent in CCR6−/− CD103+ LP‐MNPs when compared with wild‐type CD103+ LP‐MNPs (Fig. 3a,b), consistent with the inability of CCR6−/− CD103+ LP‐MNPs to interact with the epithelium. CD103− LP‐MNPs from wild‐type and CCR6−/− mice had low levels of cytokeratin 18 staining, equivalent to that seen in CD103+ LP‐MNPs from CCR6−/− mice (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Lamina propria dendritic cells (LP‐DCs) are impaired at acquiring epithelial and luminal antigens in the absence of CCR6. (a) Photomicrographs of cytospins of CD103+ LP‐DCs from wild‐type (WT) and CCR6−/− mice stained with cytokeratin 18 (cyt18; red) and DAPI (blue). (b) Quantification of the percentage of CD103+ and CD103− LP‐DCs from WT and CCR6−/− mice staining for cytokeratin 18. (c) Flow cytometry plots and (d) graphical representation of small intestine lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) after gavage of fluorescent bovine serum albumin (BSA‐647) demonstrating CD103− LP‐MNPs from CCR6−/− mice are impaired at acquiring gavaged labelled protein. (e) Quantification of BSA‐647+ LP‐MNPs following in vitro culture with various concentrations of BSA‐647 demonstrates no significant difference in the ability of CCR6‐deficient LP‐MNPs to acquire BSA‐647 in culture. n = 3 in each panel. *P < 0·05, ns = not significant. Scale bar in (a) = 20 μm. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Gavaged fluorescent protein is predominantly acquired by CD103− LP‐MNPs.16, 38 Therefore, we assessed whether CD103− LP‐MNPs were impaired at acquiring gavaged fluorescent BSA in the absence of CCR6. Consistent with previous studies, we observed that gavaged fluorescent BSA was predominantly acquired by CD103− LP‐MNPs, and that this was significantly inhibited in CCR6−/− mice (Fig. 3c,d). The impaired acquisition of gavaged protein was consistent with the inability of the LP‐MNPs to associate with the epithelium to acquire luminal substances as acquisition of fluorescent BSA by CCR6−/− LP‐MNPs was not impaired when given access to the protein in ex vivo culture (Fig. 3e). Further consistent with the reduced acquisition of fluorescent gavaged protein in vivo, CD103+ LP‐MNPs were much less efficient at acquisition of low concentrations of fluorescent protein in ex vivo cultures when compared with their CD103− counterparts (Fig. 3e). LP‐MNPs from wild‐type or CCR6−/− mice did not acquire luminally injected inert beads down to a size of 0·2 μm (data not shown), suggesting that the steady‐state antigen capture mediated by CCR6 might be restricted to soluble substances in the small intestine.

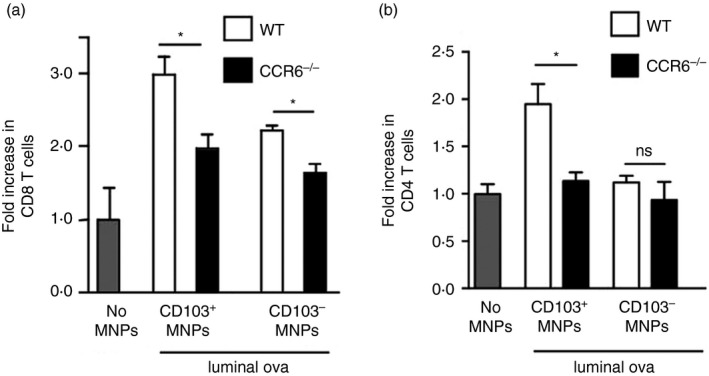

CD103− LP‐MNPs are relatively weak antigen‐presenting cells, but can transfer antigen to CD103+ LP‐DCs to induce T‐cell responses.16, 38 We evaluated the ability of LP‐MNPs to stimulate T‐cell responses to acquired luminal antigen by administering luminal OVA to wild‐type and CCR6−/− mice, isolating LP‐MNP populations from the non‐PP‐bearing intestine 2 hr later, and assessing the ability of LP‐MNPs to stimulate both CD8+ OTI and CD4+ OTII OVA‐specific T‐cell proliferation in vitro. CD103+ LP‐DCs from wild‐type mice were effective at stimulating T cells in response to luminal OVA, whereas CD103+ LP‐DCs from CCR6−/− mice were inefficient at inducing both CD4+ and CD8+ T‐cell proliferation in response to luminal antigen (Fig. 4a,b). The lack of stimulatory capacity seen in CCR6−/− LP‐DCs was not due to an intrinsic antigen presentation defect, as CCR6−/− LP‐DCs were capable of inducing T‐cell proliferation comparable with wild‐type LP‐DCs when exogenous OVA was added to the cultures (see Supplementary material, Fig. S2). The wild‐type CD103− MNP population displayed the ability to stimulate CD8+ T cells in response to luminal antigen (Fig. 4a), which is surprising given previous observations that this population is relatively inefficient at inducing T‐cell responses,16 but could be explained by their enhanced capacity to capture luminal antigen (Fig. 3c,d). The absence of antigen presentation is consistent with the inability of LP‐MNPs in CCR6−/− mice to associate with the epithelium to capture luminal antigen, suggesting that CCR6 facilitated interactions with the epithelium are central to immune surveillance of the small intestine luminal contents.

Figure 4.

Lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) from CCR6−/− mice are impaired at inducing T‐cell proliferation in response to luminal antigen. Changes in T‐cell numbers following co‐culture of naive ovalbumin (OVA) ‐specific splenic T cells from (a) CD8+ OTI T‐cell receptor transgenic mice or (b) CD4+ OTII T‐cell receptor transgenic mice with LP‐MNPs isolated from wild‐type (WT) or CCR6−/− mice receiving luminal OVA demonstrates an impaired ability of LP‐MNPs from CCR6−/− mice to induce T‐cell responses to luminal antigen. n = 2 mice of each genotype, data are representative of one of two independent replicates.

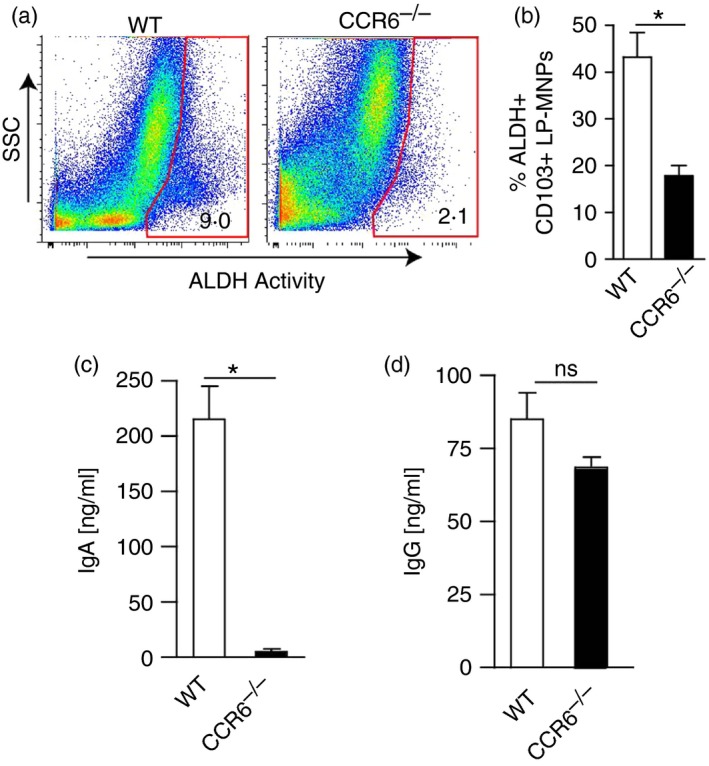

Imprinting of CD103+ LP‐MNPs is impaired in the absence of CCR6

In vitro studies have shown that intestinal epithelial cells can imprint CD103+ LP‐DCs to express aldehyde dehydrogenase,6, 7 which is essential in producing the vitamin A metabolite all‐trans retinoic acid. All‐trans retinoic acid mediates multiple events that are important for immune surveillance and homeostasis in the steady state, including inducing responding lymphocytes to express gut homing molecules and facilitating the production of IgA.8, 10, 39, 40 We observed that CD103+ LP‐DCs had significantly decreased, but not absent, expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase in the absence of CCR6 (Fig. 5a,b). Moreover CD103+ LP‐DCs from CCR6−/− mice were impaired at promoting IgA production in ex vivo cultures with wild‐type splenic B cells (Fig. 5c). Notably IgG production was not impaired in these assays, indicating a selective defect in promoting IgA production and that B‐cell survival was not altered by culture with CCR6−/− LP‐DCs (Fig. 5d). We did not observe a defect by CCR6−/− LP‐MNPs in inducing gut homing molecule expression on responding T cells (not shown), suggesting that the remaining aldehyde dehydrogenase activity in CCR6−/− LP‐MNPs was sufficient to mediate some all‐trans retinoic acid dependent events.

Figure 5.

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity is reduced in lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) deficient in CCR6. (a) Flow cytometry scatter plots for ALDH activity in small intestine LP from wild‐type (WT) and CCR6−/− mice. (b) Graph of the percent of CD103+ LP‐dendritic cells (DCs) from WT or CCR6−/− mice that are positive for ALDH activity. (c and d) IgA and IgG production following co‐culture of splenic B cells from WT mice with small intestine CD103+ LP‐MNPs isolated from WT or CCR6−/− mice. n = 4 mice for each condition, *P < 0·05, ns = not significant. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

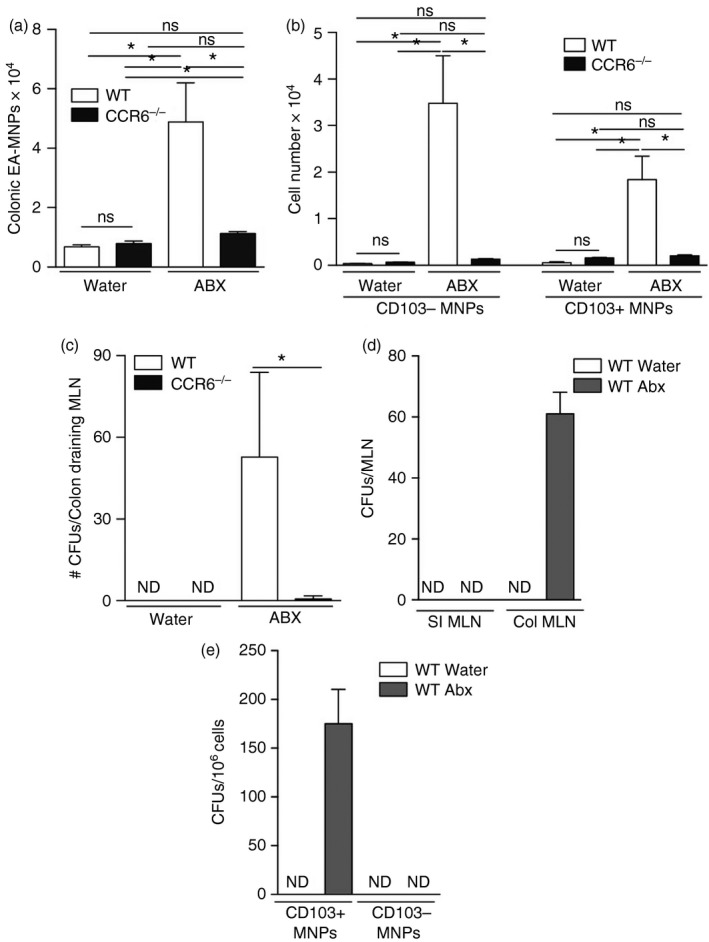

LP‐MNP association with the colonic epithelium and translocation of luminal commensal bacteria to the MLN are impaired in the absence of CCR6−/−

In comparison to the small intestine, few LP‐MNPs associate with the colonic epithelium.4 However, following antibiotic treatment to induce dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, LP‐MNPs migrate to the colonic epithelium,25 suggesting that antibiotic treatment might increase the EA‐MNP population. Moreover, disruption of the gut microbiota by antibiotics induces bacterial translocation across the colonic epithelium and their carriage to the MLN,14, 15, 41 suggesting that the presence of the EA‐MNP population may be necessary for antibiotic‐induced bacterial translocation to the MLN. Therefore, we evaluated the colonic EA‐MNP populations and bacterial translocation to the MLN in wild‐type and CCR6−/− mice in the steady state and following dysbiosis induced by treatment with a single dose of antibiotics. We found very few LP‐MNPs associated with the colonic epithelium in the steady state in wild‐type and CCR6−/− mice (Fig. 6a). However, following a single dose of antibiotics the populations of CD103+ and CD103− LP‐MNPs associating with the epithelium increased significantly in wild‐type but not CCR6−/− mice (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast to the SI in the steady state the, CD103− EA‐MNP population was larger than the CD103+ EA‐MNP population in the colon following antibiotic treatment (Fig. 6b). The increase in MNPs associating with the colonic epithelium occurred 4 days after the transient dysbiosis induced by treatment with a single dose of antibiotics, suggesting that the recovery of the gut bacteria and bacterial stimuli might drive CCR6‐dependent recruitment to the epithelium. Consistent with this we observed that continual antibiotic treatment did not result in recruitment of MNPs to the colonic epithelium (see Supplementary material, Fig. S3). Moreover, consistent with the inability of CCR6−/− LP‐MNPs to interact with the epithelium to capture luminal substances in the small intestine, translocation of commensal bacteria to the colon draining MLN following treatment with a single dose of antibiotics was impaired in the absence of CCR6 (Fig. 6c). We did not observe translocation of bacteria to the small‐intestine‐draining MLN of wild‐type mice in the presence or absence of a single dose of antibiotics (Fig. 6d), indicating that sampling of commensal bacteria in the small intestine in the steady state is a rare event. To evaluate which MNP population contained live bacteria, we sorted LP‐MNP populations from the colon of wild‐type mice given normal drinking water or a single dose of antibiotics and cultured the cells for the presence of live bacteria. We found that following antibiotic treatment, live bacteria were found in CD103+ LP‐MNPs (Fig. 6e). Our observation contrasts with previous studies demonstrating that following antibiotic treatment, fluorescently labelled bacteria are predominantly captured by macrophage‐like CX3CR1+ (CD103−) LP‐MNPs.14 This discrepancy could be explained by the enhanced capacity for macrophages to kill ingested pathogenic and non‐pathogenic bacteria.42 Indeed, we observed that CD103+ MNPs readily harboured live non‐pathogenic S. typhimurium for up to 24 hr (see Supplementary material, Fig. S4). Together these observations suggest that CX3CR1+ MNPs have not only an enhanced phagocytic capacity for live bacteria, but also an enhanced capacity to kill ingested bacteria. Whereas in contrast, CD103+ LP‐MNPs may have a reduced phagocytic capacity, but can harbour live bacteria for extended periods to allow trafficking of live bacteria to the MLN.

Figure 6.

Lamina propria mononuclear phagocyte (LP‐MNP) association with the colonic epithelium and translocation of luminal commensal bacteria to the mesenteric lymph node (MLN) is impaired in the absence of CCR6. Quantification of (a) total and (b) CD103+ or CD103− LP‐MNPs isolated with the colonic epithelium following treatment with normal drinking water or a single dose of antibiotics in wild‐type and CCR6−/− mice. (c) Colony‐forming units (CFUs) in the colon‐draining MLN following treatment with drinking water or a single dose of antibiotics in wild‐type or CCR6−/− mice. (d) Live bacteria (CFUs) in the small intestine (SI) or colon (Col) draining MLN after treatment with normal drinking water or a single dose of antibiotics. (e) Live bacteria within sorted CD103+ or CD103− colonic LP‐MNPs from wild‐type mice following a single dose of antibiotics. n = 4 per group in panels a–c and e, n = 2 panel d, data in (d) are representative of one of two independent replicates, *P < 0·05, ns = not significant.

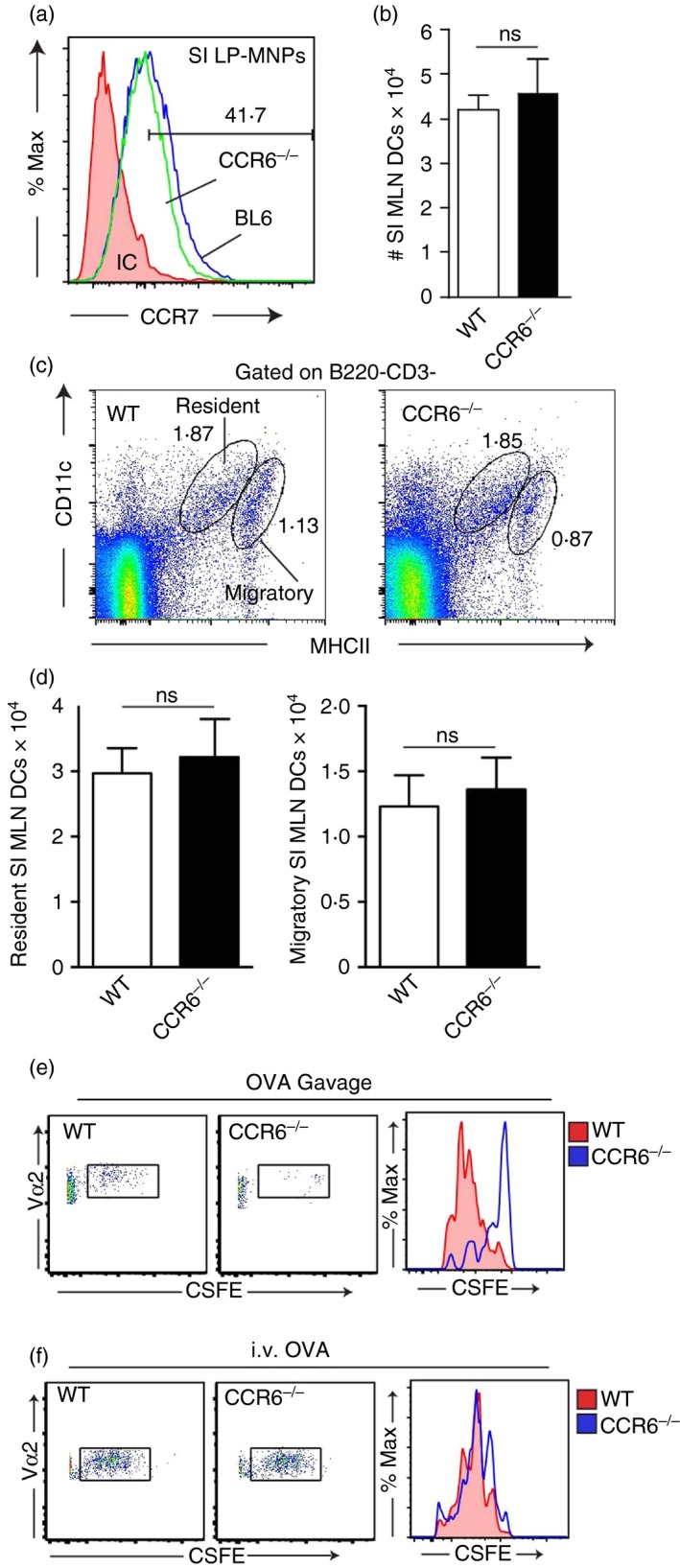

CCR6 deficiency impairs immune responses to luminal antigens in the draining MLN

Inflammatory signals induce the maturation of immature DCs, resulting in the up‐regulation of CCR7 expression and subsequent migration to the MLN. Accordingly, in the absence of CCR7, migration to the MLN and immune responses to luminal antigens in the MLN are impaired.43 We observed that LP‐MNPs from wild‐type mice and CCR6‐deficient mice had equivalent expression of CCR7 (Fig. 7a), suggesting that migration to the MLN would not be impaired in the absence of CCR6. In support of this we observed that the numbers of MLN DCs were comparable between WT and CCR6−/− mice (Fig. 7b). MLN DC populations can be characterized as resident or migratory on the basis of the levels of CD11c and MHCII expression, with the resident population being CD11chi MHCIIlo and the migratory population being CD11clo MHCIIhi.44, 45 No differences were found in the number of resident or migratory MLN DC populations in wild‐type and CCR6−/− mice (Fig. 7c,d), further supporting that, in the absence of CCR6, LP‐DC migration to the MLN was intact.

Figure 7.

Immune responses in the mesenteric lymph node to luminal, but not systemic antigen, are impaired in the absence of CCR6. (a) Flow cytometry histograms of lamina propria (LP) ‐MNPs from wild‐type (WT) and CCR6‐deficient mice demonstrating similar levels of in CCR7 expression in the absence of CCR6. (b) Absolute numbers of mesenteric lymph node (MLN) dendritic cells (DCs) in WT and CCR6‐deficient mice. (c) Representative flow cytometry plots and (d) graphical representation of the resident and migratory MLN DC populations from WT and CCR6‐deficient mice. (e) Flow cytometry plots and histograms of adoptively transferred ovalbumin (OVA) ‐specific CD4+ OTII T cells from the MLNs of WT or CCR6‐deficient mice given that (e) luminal or (f) intravenous OVA demonstrates that MLN T‐cell responses to luminal but not systemic antigen are impaired in the absence of CCR6. Panels a, c, e, and f are representative of three replicates, n = 3 panels b and d. ns = not significant, *P < 0·05. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

CD103+ LP‐MNPs acquire luminal antigens either directly or through transfer from CD103− LP‐MNPs and migrate to the MLN in a CCR7‐dependent manner to initiate adaptive immunity.5, 16, 38, 43 Because CCR7 is required for LP‐DC migration to the MLN16, 43 and CCR6 deficiency impairs the acquisition of luminal antigens by LP‐DCs, we expect that, like CCR7‐deficient mice, CCR6‐deficient mice would have an impaired ability to induce immune responses in the MLN to a luminal antigen, but would have intact responses to antigens encountered by other routes. We adoptively transferred OVA‐specific splenic T cells from OTII T‐cell receptor transgenic mice and evaluated antigen‐specific T‐cell proliferation in the MLNs of wild‐type and CCR6‐deficient mice following gavage or intravenous injection of OVA. CCR6‐deficient mice had impaired MLN T‐cell proliferation in response to luminal OVA (Fig. 7e), similar to what has been reported for CCR7‐deficient mice.43 The small number of OTII T cells responding to luminal OVA in the MLN precluded identifying changes in cytokine production (data not shown). However, the absence of CCR6 did not impair MLN responses to systemic OVA (Fig. 7f), indicating that the absence of CCR6 did not impair T‐cell responses when antigen was delivered to the MLN by other routes.

Discussion

The foremost function of the intestinal epithelium is the absorption of vital nutrients, necessitating that this be an imperfect barrier. As a consequence, the underlying immune system continually monitors the luminal environment to maintain homeostasis. Disruption of immune surveillance could result in failure to induce and maintain tolerance to innocuous substances and subsequent inappropriate inflammatory responses, or alternatively failure to mount protective immunity to pathogens. Despite the importance of this process, little was known about the factors promoting immune surveillance at the non‐follicle‐bearing epithelium in the steady state and models to test the importance of LP‐MNP interactions with the epithelium in vivo were lacking.

A current model of immune surveillance of the intestine suggests the sequential migration of LP‐MNPs to the epithelium, the acquisition of luminal substances by LP‐MNPs, and the migration of the LP‐DCs to the MLN to induce immune responses. Here, we identified potential factors that mediate the early steps of immune surveillance by evaluating the expression of a panel of targets related to chemotaxis in mice where LP‐MNP association with the epithelium was blocked. Candidates were selected based on the following criteria: decreased epithelial expression following LTβR blockade, a pathway identified as being important for LP‐MNPs to associate with the epithelium in the steady state,4 and higher expression in the epithelium relative to the LP, which would provide a gradient for migration. CCL20 met these criteria. CCR6, the receptor for CCL20, was present on the surface of LP‐MNPs associating with the epithelium and deletion of CCR6 impaired LP‐MNP association with the epithelium. In support of these molecules being key factors, previous studies have noted that CCL20 is expressed by intestinal epithelial cells,46 and that its expression is increased in response to LTβR ligation in epithelial cell lines.47 In addition, CCR6, the only known receptor for CCL20, is expressed by myeloid DCs,21 which make up the bulk of the LP‐MNP population.1, 2 Moreover CCR6 and CCL20 serve parallel functions to recruit DCs to the epithelial surface to sample the environment in other mucosal sites.36, 48 We observed that the LP contained CCR6+ and CCR6− CD11c+ populations. CCR6 expression is down‐regulated as DCs mature and coordinated with increased expression of CCR7, which facilitates migration to the MLN and the induction of T‐cell responses to luminal antigen.43, 49 This suggests that the CCR6+ and CCR6− CD11c+ LP populations are probably related populations at different stages in the process of maturation and antigen capture and migration to the MLN as opposed to distinct lineages.

Using TCR transgenic mice specific for S. typhimurium flagellin, Salazar‐Gonzalez et al.36 evaluated which PP DCs played a role in initiating T‐cell responses to an enteric pathogen. They observed that CCR6+ DCs in the subepithelial dome PP were recruited to the follicle‐associated epithelium following infection. These PP DCs were CX3CR1−, and initiation of T‐cell responses to S. typhimurium was dependent upon CCR6. They noted that CCR6 expression was largely restricted to the DCs in the PP, with LP‐DCs being largely CX3CR1+ with little CCR6 expression. In combination with studies showing that CCL20 is highly expressed by the follicle‐associated epithelium overlying the PP,50, 51 these observations suggested distinct roles for PP DCs based upon CCR6 expression, and by extension were interpreted to indicate that CCR6 was unlikely to play a role in LP‐MNP functions. Like Salazar‐Gonzalez et al., we observed that a subset of PP DCs expressed high levels of CCR6. However, we also observed that CCR6 expression is not absent, but expressed at lower levels on LP‐MNPs. Moreover, CCR6 expression was increased in the subset of MNPs associating with the epithelium. Similar to our observations, Farache et al.3 also noted that CD103+ LP‐MNPs express CCR6. However, they did not find changes in the population of CD103+ MNPs isolated with the epithelium in S. typhimurium‐infected mice given CCL20 blockade or in S. typhimurium‐infected mice reconstituted with CCR6‐deficient bone marrow,3 suggesting that in response to enteric infection other chemotactic factors recruit CD103+ MNPs to the epithelium.

Multiple studies have observed that LP‐MNPs associate with the intestinal epithelium.11, 13, 27, 52, 53 It has been suggested that the CD103− LP‐MNPs isolated with the epithelium represent an artefact from cells that crawl out of the LP when the epithelium is removed.3 Although we agree that the CD103− LP‐MNPs isolated with the epithelium arise from those that have been observed protruding through the fenestrated basement membrane and contact epithelial cells,28, 29 the interpretation that this is an artefact is inconsistent with the observations here demonstrating that the population of LP‐MNPs isolated with the epithelium is reduced by manipulations such as CCR6 loss and LTβR‐Ig blockade, which do not affect the LP‐MNP population. Moreover, the number of MNPs isolated with the epithelium, which includes both CD103+ and CD103− LP‐MNPs, is consistent with the hundreds of thousands of villi in the small intestine and studies identifying that ~2 MNPs per villus are positioned with substantial portions of the cell above the basement membrane.3, 4, 54 These observations, combined with observations demonstrating impaired luminal antigen capture, impaired T‐cell responses to luminal antigen, and impaired sampling of commensal bacteria correlate with a reduction in the LP‐MNP population isolated with the epithelium indicate the biological relevance of LP‐MNP interactions with the epithelium and that evaluating alterations in this cellular population is a valid way to assess alterations in this biological process.

Previous work has suggested a role for MNP–epithelial interactions in luminal antigen capture, sampling the commensal microbiota, and imprinting DCs; however, an in vivo model to validate the importance of these observations was lacking. Leveraging the observation that these interactions were impaired in the absence of CCR6, we evaluated a requirement for these interactions in downstream events related to immune surveillance. Like other studies, we observed that luminal fluorescent protein was largely acquired by CD103− LP‐MNPs,16, 38 but we also observed that acquisition of the luminal protein was impaired in the absence of CCR6. The failure to acquire the fluorescent protein was not due to defects in antigen uptake by LP‐MNPs, as knockout and wild‐type MNPs displayed similar uptake across a wide range of concentrations when protein was added ex vivo, further supporting that the relevant defect in the absence of CCR6 is related to positioning of the MNPs near the epithelium. Like previous observations,16, 38 we also observed that CD103+ LP‐MNPs were less efficient at acquiring luminal fluorescent protein. This may reflect the relatively low concentration of luminal protein to which they are exposed following gavage and their relatively inefficient capture of proteins when compared with CD103− LP‐MNPs, as evidenced by the smaller population of DCs staining positive for fluorescent protein when exposed to low concentrations ex vivo. We did not observe a reduction in the CD103+ LP‐DC population staining positive following gavage of fluorescent protein in the absence of CCR6; however, the CD103+ population staining positive in wild‐type mice was small, making it difficult to detect a further reduction.

Similar to previous observations,5, 38 we found that luminal antigen acquired by CD103+ LP‐MNPs and to a lesser extent CD103− LP‐MNPs, could induce antigen‐specific T‐cell proliferation. Moreover, we observed that this was impaired in the absence of CCR6. This defect was not due to impaired antigen presentation capacity in CCR6−/− LP‐MNPs as CCR6−/− LP‐MNPs could induce T‐cell responses equivalent to wild‐type LP‐MNPs when exogenous OVA was added to the cultures. LP‐MNPs receiving luminal antigen, migrate to the draining MLN to induce T‐cell responses.16, 43 We also observed that in the absence of CCR6, T‐cell responses in the MLN to luminal, but not systemic, antigen were impaired, further supporting that the relevant defect producing this phenotype is the inability of LP‐MNPs to associate with the epithelium to capture luminal antigen. Consistent with our observation that in the absence of CCR6 the population of MNPs associating with the epithelium was reduced, but not absent, T‐cell responses to luminal antigen in the MLN were significantly reduced but not completely absent. This could suggest that CCR6− MNPs may also sample luminal antigen, or that immune responses in the MLN to luminal antigen might occur independent of antigen capture at the epithelial surface by processes such as leak and drainage through the lymphatics. Similar to the defects we observed in the SI in the absence of CCR6, CCR6−/− mice had impaired colonic LP‐MNP epithelial associations and significantly reduced translocation of commensal bacteria following a single dose of antibiotics, a manipulation that has been demonstrated to induce LP‐MNPs to acquire luminal bacteria and carry them to the MLN.14, 15 The defects downstream of impaired association of LP‐MNPs with the epithelium extended beyond the capture of luminal substances and affected the imprinting of LP‐DCs to induce mucosal type responses, suggesting that some of the defects seen in mucosal immune responses in the absence of CCR651 could be an extension of impaired imprinting of LP‐DCs.

CCR6 is expressed by a variety of cell types, and the absence of CCR6 results in multiple and various defects related to intestinal immunity, including alterations in the development of lymphoid tissues, impaired immunity to enteric antigens and pathogens, reduced IgA production, and enhanced susceptibility to colitis.36, 51, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 However, the basis for these defects is incompletely understood. Here we identify a role for CCL20 and CCR6 in the steady‐state surveillance of the epithelium by LP‐MNPs. Our observations suggest that some of the alterations in intestinal immune responses seen in the absence of CCR6 may be linked to impaired epithelial LP‐MNP interactions.

Author contributions

KGM, LWW, JRM, SJ, JKG, DHK and KAK performed the experiments. IRW, MJM and RDN designed the study. KGM, LWW, IRW, MJM and RDN wrote the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and agree with the manuscript content.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Two populations of mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs) associate with the small intestine (SI) villous epithelium. (a) Photomicrograph of SI villi following removal of the epithelium demonstrates an intact villus structure and the presence of MNPs within the remaining lamina propria (LP), red = CD49f staining, green = CD11c staining, blue = DAPI nuclear stain. (b–d) Flow cytometry of the cell population released with the epithelium demonstrates the presence of (b) CD45+ CD11c+ MHCII+ population that is largely (c) CD11b+ and (d) CD103+ or CD103−. (e) Flow cytometry of the epithelium‐associated (EA) MNP populations isolated from CX3CR1GFP reporter mice reveal that the CD103+ EA‐MNP population is CX3CR1− whereas the CD103− EA‐MNP population is largely CX3CR1+. (f–h) Flow cytometry plots demonstrating the CD103+ and CD103− epithelium‐associated (EA) MNPs expressed similar levels of (f) CD80 and (g) CD86 and (h) the CD103− population expressed higher levels of signal regulatory protein‐α. (i and j) Flow cytometry plots of the CD45+ CD11c+ MHCII+ populations isolated with the (i) epithelium or (j) LP of CX3CR1GFP reporter mice demonstrate that the EA population is largely devoid of the CX3CR1hi CD64hi macrophage population that is present in the LP. Photos and plots are representative of one of three or more replicates.

Figure S2. Lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) from CCR6−/− mice can induce antigen‐specific T‐cell responses when supplied with exogenous antigen. CD103+ and CD103− small intestine LP‐MNPs were isolated from WT and CCR6−/− mice and cultured with 2 μg ovalbumin (OVA) and OVA‐specific splenic T cells isolated from (a) CD8+ OTI T and (b) CD4+ OTII T‐cell receptor transgenic mice. After 72 hr, cultures were harvested and the number of T cells was evaluated by counting and analysis by flow cytometry. ns = not significant. Data are representative of one of two replicates.

Figure S3. Continuous antibiotic treatment does not recruit mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs) to the colonic epithelium. Mice were given regular drinking water, a single dose of antibiotics, or continuous antibiotics in drinking water and evaluated 4 days later for the population of MNPs associating with the epithelium. *P < 0·05, ns = not significant, n = 3 mice in each treatment group.

Figure S4. CD103+, but not CD103− lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) can harbour live non‐invasive bacteria for extended periods. Sorted CD103+ and CD103− LP‐MNPs were incubated with wild‐type (WT) or invasion deficient (ΔInV) Salmonella typhimurium, washed and cultured in a gentamicin protection assay for 24 hr after which cells were lysed and the number of live bacteria was assessed by culture. CD103+ LP‐MNPs harboured live non‐invasive, but not invasive bacteria, whereas CD103− LP‐MNPs killed both non‐invasive and invasive bacteria. n = 2 per treatment group, data are representative of one of two independent replicates.

Table S1. Antibodies/staining reagents used.

Table S2. Primer sequences use for RT‐PCR.

Acknowledgements

DK097317, DK109006, AI131342 and AI077600. The Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Center Core, supported by NIH grant P30 DK052574 assisted with imaging. The High Speed Cell Sorter Core at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes‐Jewish Hospital in St Louis, MO provided flow cytometric cell sorting services. The Siteman Cancer Center is supported in part by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA91842.

References

- 1. Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, Shang L, Hashimoto D, Greter M et al Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity 2009; 31:513–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Varol C, Vallon‐Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H et al Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity 2009; 31:502–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farache J, Koren I, Milo I, Gurevich I, Kim KW, Zigmond E et al Luminal bacteria recruit CD103+ dendritic cells into the intestinal epithelium to sample bacterial antigens for presentation. Immunity 2013; 38:581–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McDonald KG, Leach MR, Brooke KW, Wang C, Wheeler LW, Hanly EK et al Epithelial expression of the cytosolic retinoid chaperone cellular retinol binding protein II is essential for in vivo imprinting of local gut dendritic cells by lumenal retinoids. Am J Pathol 2012; 180:984–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McDole JR, Wheeler LW, McDonald KG, Wang B, Konjufca V, Knoop KA et al Goblet cells deliver luminal antigen to CD103+ dendritic cells in the small intestine. Nature 2012; 483:345–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iliev ID, Spadoni I, Mileti E, Matteoli G, Sonzogni A, Sampietro GM et al Human intestinal epithelial cells promote the differentiation of tolerogenic dendritic cells. Gut 2009; 58:1481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iliev ID, Mileti E, Matteoli G, Chieppa M, Rescigno M. Intestinal epithelial cells promote colitis‐protective regulatory T‐cell differentiation through dendritic cell conditioning. Mucosal Immunol 2009; 2:340–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia‐Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y et al A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF‐β and retinoic acid‐dependent mechanism. J Exp Med 2007; 204:1757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR et al Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med 2007; 204:1775–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mora JR, Iwata M, Eksteen B, Song SY, Junt T, Senman B et al Generation of gut‐homing IgA‐secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science 2006; 314:1157–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niess JH, Brand S, Gu X, Landsman L, Jung S, McCormick BA et al CX3CR1‐mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science 2005; 307:254–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim KW, Vallon‐Eberhard A, Zigmond E, Farache J, Shezen E, Shakhar G et al In vivo structure/function and expression analysis of the CX3C chemokine fractalkine. Blood 2011; 118:e156–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chieppa M, Rescigno M, Huang AY, Germain RN. Dynamic imaging of dendritic cell extension into the small bowel lumen in response to epithelial cell TLR engagement. J Exp Med 2006; 203:2841–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diehl GE, Longman RS, Zhang JX, Breart B, Galan C, Cuesta A et al Microbiota restricts trafficking of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes by CX3CR1hi cells. Nature 2013; 494:116–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knoop KA, McDonald KG, Kulkarni DH, Newberry RD. Antibiotics promote inflammation through the translocation of native commensal colonic bacteria. Gut 2016; 65:1100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schulz O, Jaensson E, Persson EK, Liu X, Worbs T, Agace WW et al Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J Exp Med 2009; 206:3101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell 1994; 76:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA‐based α‐ and β‐chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol Cell Biol 1998; 76:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lindquist RL, Shakhar G, Dudziak D, Wardemann H, Eisenreich T, Dustin ML et al Visualizing dendritic cell networks in vivo . Nat Immunol 2004; 5:1243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Futterer A, Mink K, Luz A, Kosco‐Vilbois MH, Pfeffer K. The lymphotoxin β receptor controls organogenesis and affinity maturation in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity 1998; 9:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kucharzik T, Hudson JT 3rd, Waikel RL, Martin WD, Williams IR. CCR6 expression distinguishes mouse myeloid and lymphoid dendritic cell subsets: demonstration using a CCR6 EGFP knock‐in mouse. Eur J Immunol 2002; 32:104–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newberry RD, McDonough JS, McDonald KG, Lorenz RG. Postgestational lymphotoxin/lymphotoxin β receptor interactions are essential for the presence of intestinal B lymphocytes. J Immunol 2002; 168:4988–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McDonald KG, McDonough JS, Dieckgraefe BK, Newberry RD. Dendritic cells produce CXCL13 and participate in the development of murine small intestine lymphoid tissues. Am J Pathol 2010; 176:2367–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Knoop KA, McDonald KG, McCrate S, McDole JR, Newberry RD. Microbial sensing by goblet cells controls immune surveillance of luminal antigens in the colon. Mucosal Immunol 2015; 8:198–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knoop KA, Gustafsson JK, McDonald KG, Kulkarni DH, Kassel R, Newberry RD. Gut Microbes Addenda: antibiotics promote the sampling of luminal antigens and bacteria via colonic goblet cell associated antigen passages. Gut Microbes 2017; 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1299846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McKinney J, Guerrier‐Takada C, Galan J, Altman S. Tightly regulated gene expression system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium . J Bacteriol 2002; 184:6056–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maric I, Holt PG, Perdue MH, Bienenstock J. Class II MHC antigen (Ia)‐bearing dendritic cells in the epithelium of the rat intestine. J Immunol 1996; 156:1408–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takahashi‐Iwanaga H, Iwanaga T, Isayama H. Porosity of the epithelial basement membrane as an indicator of macrophage–enterocyte interaction in the intestinal mucosa. Arch Histol Cytol 1999; 62:471–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takeuchi T, Gonda T. Distribution of the pores of epithelial basement membrane in the rat small intestine. J Vet Med Sci 2004; 66:695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Velázquez P, Wei B, McPherson M, Mendoza LMA, Nguyen SL, Turovskaya O et al Villous B cells of the small intestine are specialized for invariant NK T cell dependence. J Immunol 2008; 180:4629–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Cao Y, Makris C et al The lymphotoxin‐β receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF‐κB pathways. Immunity 2002; 17:525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schneider K, Potter KG, Ware CF. Lymphotoxin and LIGHT signaling pathways and target genes. Immunol Rev 2004; 202:49–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alimzhanov MB, Kuprash DV, Kosco‐Vilbois MH, Luz A, Turetskaya RL, Tarakhovsky A et al Abnormal development of secondary lymphoid tissues in lymphotoxin β‐deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:9302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Togni P, Goellner J, Ruddle NH, Streeter PR, Fick A, Mariathasan S et al Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science 1994; 264:703–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rennert PD, James D, Mackay F, Browning JL, Hochman PS. Lymph node genesis is induced by signaling through the lymphotoxin β receptor. Immunity 1998; 9:71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Salazar‐Gonzalez RM, Niess JH, Zammit DJ, Ravindran R, Srinivasan A, Maxwell JR et al CCR6‐mediated dendritic cell activation of pathogen‐specific T cells in Peyer's patches. Immunity 2006; 24:623–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liao F, Alderson R, Su J, Ullrich SJ, Kreider BL, Farber JM. STRL22 is a receptor for the CC chemokine MIP‐3α . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 236:212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mazzini E, Massimiliano L, Penna G, Rescigno M. Oral tolerance can be established via gap junction transfer of fed antigens from CX3CR1+ macrophages to CD103+ dendritic cells. Immunity 2014; 40:248–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. Retinoic acid imprints gut‐homing specificity on T cells. Immunity 2004; 21:527–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kang SG, Lim HW, Andrisani OM, Broxmeyer HE, Kim CH. Vitamin A metabolites induce gut‐homing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2007; 179:3724–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berg RD. Promotion of the translocation of enteric bacteria from the gastrointestinal tracts of mice by oral treatment with penicillin, clindamycin, or metronidazole. Infect Immun 1981; 33:854–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Houghton AM, Hartzell WO, Robbins CS, Gomis‐Ruth FX, Shapiro SD. Macrophage elastase kills bacteria within murine macrophages. Nature 2009; 460:637–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Worbs T, Bode U, Yan S, Hoffmann MW, Hintzen G, Bernhardt G et al Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2006; 203:519–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Satpathy AT, Briseno CG, Lee JS, Ng D, Manieri NA, Kc W et al Notch2‐dependent classical dendritic cells orchestrate intestinal immunity to attaching‐and‐effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:937–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cerovic V, Houston SA, Westlund J, Utriainen L, Davison ES, Scott CL et al Lymph‐borne CD8α + dendritic cells are uniquely able to cross‐prime CD8+ T cells with antigen acquired from intestinal epithelial cells. Mucosal Immunol 2015; 8:38–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tanaka Y, Imai T, Baba M, Ishikawa I, Uehira M, Nomiyama H et al Selective expression of liver and activation‐regulated chemokine (LARC) in intestinal epithelium in mice and humans. Eur J Immunol 1999; 29:633–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rumbo M, Sierro F, Debard N, Kraehenbuhl JP, Finke D. Lymphotoxin β receptor signaling induces the chemokine CCL20 in intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology 2004; 127:213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Le Borgne M, Etchart N, Goubier A, Lira SA, Sirard JC, van Rooijen N et al Dendritic cells rapidly recruited into epithelial tissues via CCR6/CCL20 are responsible for CD8+ T cell crosspriming in vivo . Immunity 2006; 24:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Mantovani A. The role of chemokines in the regulation of dendritic cell trafficking. J Leukoc Biol 1999; 66:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Iwasaki A, Kelsall BL. Localization of distinct Peyer's patch dendritic cell subsets and their recruitment by chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)‐3α, MIP‐3β, and secondary lymphoid organ chemokine. J Exp Med 2000; 191:1381–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cook DN, Prosser DM, Forster R, Zhang J, Kuklin NA, Abbondanzo SJ et al CCR6 mediates dendritic cell localization, lymphocyte homeostasis, and immune responses in mucosal tissue. Immunity 2000; 12:495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R et al Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol 2001; 2:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wendland M, Czeloth N, Mach N, Malissen B, Kremmer E, Pabst O et al CCR9 is a homing receptor for plasmacytoid dendritic cells to the small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:6347–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chabot S, Wagner JS, Farrant S, Neutra MR. TLRs regulate the gatekeeping functions of the intestinal follicle‐associated epithelium. J Immunol 2006; 176:4275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McDonald KG, McDonough JS, Wang C, Kucharzik T, Williams IR, Newberry RD. CC chemokine receptor 6 expression by B lymphocytes is essential for the development of isolated lymphoid follicles. Am J Pathol 2007; 170:1229–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Varona R, Villares R, Carramolino L, Goya I, Zaballos A, Gutierrez J et al CCR6‐deficient mice have impaired leukocyte homeostasis and altered contact hypersensitivity and delayed‐type hypersensitivity responses. J Clin Invest 2001; 107:R37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lügering A, Kucharzik T, Soler D, Picarella D, Hudson III, Williams IR. Lymphoid precursors in intestinal cryptopatches express CCR6 and undergo dysregulated development in the absence of CCR6. J Immunol 2003; 171:2208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Varona R, Cadenas V, Flores JM, Martinez AC, Marquez G. CCR6 has a non‐redundant role in the development of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol 2003; 33:2937–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lügering A, Floer M, Westphal S, Maaser C, Spahn TW, Schmidt MA et al Absence of CCR6 inhibits CD4+ regulatory T‐cell development and M‐cell formation inside Peyer's patches. Am J Pathol 2005; 166:1647–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reboldi A, Arnon TI, Rodda LB, Atakilit A, Sheppard D, Cyster JG. IgA production requires B cell interaction with subepithelial dendritic cells in Peyer's patches. Science 2016; 352:4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Two populations of mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs) associate with the small intestine (SI) villous epithelium. (a) Photomicrograph of SI villi following removal of the epithelium demonstrates an intact villus structure and the presence of MNPs within the remaining lamina propria (LP), red = CD49f staining, green = CD11c staining, blue = DAPI nuclear stain. (b–d) Flow cytometry of the cell population released with the epithelium demonstrates the presence of (b) CD45+ CD11c+ MHCII+ population that is largely (c) CD11b+ and (d) CD103+ or CD103−. (e) Flow cytometry of the epithelium‐associated (EA) MNP populations isolated from CX3CR1GFP reporter mice reveal that the CD103+ EA‐MNP population is CX3CR1− whereas the CD103− EA‐MNP population is largely CX3CR1+. (f–h) Flow cytometry plots demonstrating the CD103+ and CD103− epithelium‐associated (EA) MNPs expressed similar levels of (f) CD80 and (g) CD86 and (h) the CD103− population expressed higher levels of signal regulatory protein‐α. (i and j) Flow cytometry plots of the CD45+ CD11c+ MHCII+ populations isolated with the (i) epithelium or (j) LP of CX3CR1GFP reporter mice demonstrate that the EA population is largely devoid of the CX3CR1hi CD64hi macrophage population that is present in the LP. Photos and plots are representative of one of three or more replicates.

Figure S2. Lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) from CCR6−/− mice can induce antigen‐specific T‐cell responses when supplied with exogenous antigen. CD103+ and CD103− small intestine LP‐MNPs were isolated from WT and CCR6−/− mice and cultured with 2 μg ovalbumin (OVA) and OVA‐specific splenic T cells isolated from (a) CD8+ OTI T and (b) CD4+ OTII T‐cell receptor transgenic mice. After 72 hr, cultures were harvested and the number of T cells was evaluated by counting and analysis by flow cytometry. ns = not significant. Data are representative of one of two replicates.

Figure S3. Continuous antibiotic treatment does not recruit mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs) to the colonic epithelium. Mice were given regular drinking water, a single dose of antibiotics, or continuous antibiotics in drinking water and evaluated 4 days later for the population of MNPs associating with the epithelium. *P < 0·05, ns = not significant, n = 3 mice in each treatment group.

Figure S4. CD103+, but not CD103− lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes (LP‐MNPs) can harbour live non‐invasive bacteria for extended periods. Sorted CD103+ and CD103− LP‐MNPs were incubated with wild‐type (WT) or invasion deficient (ΔInV) Salmonella typhimurium, washed and cultured in a gentamicin protection assay for 24 hr after which cells were lysed and the number of live bacteria was assessed by culture. CD103+ LP‐MNPs harboured live non‐invasive, but not invasive bacteria, whereas CD103− LP‐MNPs killed both non‐invasive and invasive bacteria. n = 2 per treatment group, data are representative of one of two independent replicates.

Table S1. Antibodies/staining reagents used.

Table S2. Primer sequences use for RT‐PCR.