Abstract

The soybean cyst nematode (SCN) is one of the most destructive pathogens of soybean plants worldwide. Host-plant resistance is an environmentally-friendly method to mitigate SCN damage. To date, the resistant soybean cultivars harbor limited genetic variation, and some are losing resistance. Thus, a better understanding of the genetic mechanisms of the SCN resistance, as well as developing diverse resistant soybean cultivars, is urgently needed. In this study, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) was conducted using 1,032 wild soybean (Glycine soja) accessions with over 42,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to understand the genetic architecture of G. soja resistance to SCN race1. Ten SNPs were significantly associated with the response to race 1. Three SNPs on chromosome 18 were localized within the previously identified quantitative trait loci (QTLs), and two of which were localized within a strong linkage disequilibrium block encompassing a nucleotide-binding (NB)-ARC disease resistance gene (Glyma.18g102600). Genes encoding methyltransferases, the calcium-dependent signaling protein, the leucine-rich repeat kinase family protein, and the NB-ARC disease resistance protein, were identified as promising candidate genes. The identified SNPs and candidate genes can not only shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying SCN resistance, but also can facilitate soybean improvement employing wild genetic resources.

Keywords: wild soybean, soybean cyst nematode (SCN), single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), genome-wide association study (GWAS), candidate genes, Crop wild relatives

1. Introduction

SCN is a major pest of soybeans [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] worldwide. Soybean plants infected with SCN exhibit symptoms of root necrosis and stunting underground as well as leaf chlorosis, early senescence, and seed weight reduction. The soybean production loss caused by SCN is estimated to cost $1.5 billion annually in the USA, which makes it the most damaging pest than any other soybean pathogens (Wrather and Koenning 2006). Crop rotation for multiple years can reduce levels of SCN in the field, but this practice is dependent on the profitability and practicality of the non-host crops. Nematicides are costly and environmentally harmful. In contrast, the use of resistant soybean cultivars is an economically and environmentally friendly method of mitigating SCN damage to soybeans. However, continuous use of cultivars derived from a single genetic source of resistance can cause the SCN population to evolve to overcome host resistance, thus diminishing the utility of any given SCN-resistant soybean cultivar.

The first reported case of SCN in North America occurred in North Carolina (Winstead et al. 1955), and the pest has since spread through soybean growing areas of the United States. Thus far, SCN has been found in every soybean-producing state except New York and West Virginia and continues to spread considerably (Tylka and Marett 2014). Sixteen potential SCN races have been identified using four different hosts: PI548402 (Peking), PI548988 (Pickett), PI88788, and PI90763 (we call this classification scheme as SCN race scheme). A modified classification scheme was subsequently developed using the H. glycine (HG) type to characterize a SCN population (Niblack et al. 2003); this scheme is more suitable for characterizing a heterogeneous SCN population and has been extensively used in classifying SCN populations. The method uses a panel of seven soybean genotypes (Peking, PI88788, PI90763, 437654, 209332, PI89772 and PI548316) with varying levels of resistance to SCN (we call this modified classification scheme as SCN type scheme). Here we use SCN race scheme because 1) the SCN screening in this study was performed in the year 2000 (prior to the development of SCN type scheme) (Niblack et al. 2002); 2) both race 1 and race 5 have the same SCN type (HG 2.5.7); 3) the term “race” has been used in soybean-breeding efforts referring to the SCN population for many decades and it is convenient for comparison. The SCN originally found in North Carolina was later categorized as race 1 (Golden et al. 1970). Now this race is widely spread in most soybean fields. It has been demonstrated that cultivated soybeans underwent a severe “genetic bottleneck” (Hyten et al. 2006), and some of well-used resistant cultivars are loosing resistance due to SCN race shifts (Mitchum et al. 2007; Niblack et al. 2008). It is in urgent needs to explore new sources of SCN resistance in the wild relatives of soybeans and to develop novel SCN resistant soybean cultivars.

Knowledge of the genetic basis of the soybean-SCN interaction mostly comes from quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping and genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Soybean resistance to SCN is a complex trait involving many genes. To date, at least 40 QTLs from different resistant varieties have been mapped to 17 of 20 chromosomes (Concibido et al. 2004; Vuong et al. 2010); 14 of these QTLs were associated with race 1 resistance. The identification of two significant loci, rhg1 on chromosome 18 and Rhg4 on chromosome 8, has revealed that the copy number variation of three tandem genes (an amino acid transporter, an alpha-SNAP, and a wounding-inducible protein 12) and the involvement of a serine hydroxymethyltransferase provide resistance to SCN. Genomic regions containing or adjacent to these important loci are associated with resistance to multiple races (Yue et al. 2000; Guo et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2009). GWAS is increasingly being used to identify the genetic basis of complex traits variation in diverse crop species (Li et al. 2013; Morris et al. 2013). Recent analyses of sudden death syndrome resistance in soybean plants confirmed 7 loci in previously reported QTL intervals and identified 13 novel loci using the GWAS approach (Wen et al. 2014). Accordingly, GWAS was also applied to scan genomic regions associated with resistance to SCN races 3 and 4 in cultivated soybean populations (Han et al. 2015; Vuong et al. 2015). In these and other studies, both known and novel QTLs were identified, and candidate genes underlying SCN resistance were suggested (Wen et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2015b). GWA mapping showed a useful complementary approach to classical bi-parental QTL mapping for dissecting the genetic basis of complex traits variation.

Crop wild relatives (CWR) have gradually gained attention during the past decade due to their higher genetic diversity than that of their domesticated decedents. CWRs have been extensively studied for identification of genes associated with abiotic and biotic stress resistance, as well as crop improvement (Zhang et al. 2016a). The wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. & Zucc.) is the closest relative of the cultivated soybean (Glycine max). G. soja has retained more than half of the genetic diversity that had been lost in the cultivated soybean due to “bottleneck” events during the domestication process (Hyten et al. 2006; Zhou et al. 2015). Long-term exposure to the combination of various harsh environmental stresses has led G. soja to possess superior characteristics in abiotic stress tolerance (Qi et al. 2014) and biotic stress resistance (Kim et al. 2011; Tian and Smith 2015). To date, few studies have used G. soja to identify QTLs for SCN resistance (Kim et al. 2011; Kim and Diers 2013; Zhang et al. 2016b), whereas no studies have applied high-density SNP markers to understand the genetic architecture of the G. soja response to race 1.

In this study, we evaluated the resistance responses of a set of 1,032 G. soja accessions to (1) quantify the diversity of the G. soja resistance response to SCN race 1; (2) identify genomic regions significantly associated with race 1 resistance using the GWAS strategy with ~42,000 genome-side SNPs, and (3) predict candidate genes involved in the G. soja response to race 1 infection.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

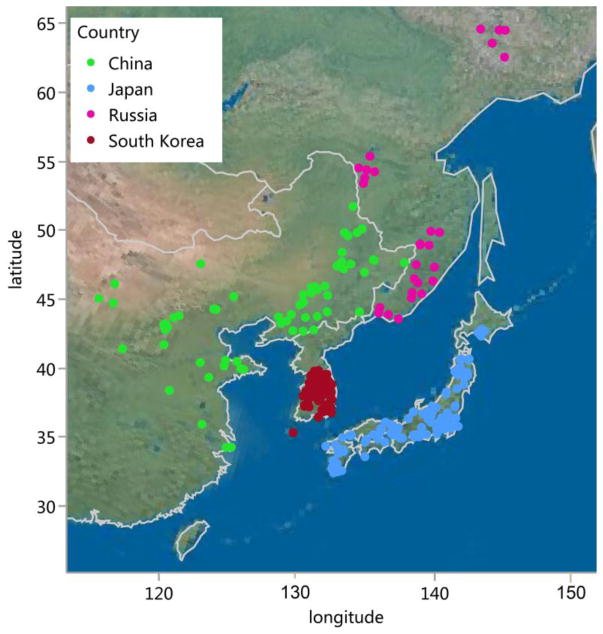

2.1. Wild Soybean Samples and Phenotype

A total of 1,032 G. soja accessions from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Soybean Germplasm Collection were used for association analysis in this study (Table S1). This set of G. soja accessions originated from four East Asian countries: Russia, China, Japan, and South Korea (Figure 1). All these 1,032 accessions were evaluated for resistance levels to SCN race 1 in the year 2000 by Prakash team. The SCN screening assay was performed in the greenhouse as described previously (Arelli et al. 2000). Ten seedlings of each accession were used for SCN inoculation. Peking, Pickett, PI 88788, PI 90763, and PI 437654 were used as host differentials, with Hutcheson as the susceptible control. Bioassays were repeated with the lines initially found to be resistant. Each seedling was inoculated with 1200 ± 25 eggs in 5 mL distilled water suspension. The resistance level for each accession was evaluated using female index (FI), which is a percentage of the number of females produced on each line divided by the number produced on a standard susceptible soybean, and the result is multiplied by 100. The screening result was retrieved from USDA website: https://training.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/, which was reported using SCN race scheme (Table S1). We used the term “HG type” when to compare to recently published results.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of 1,032 G. soja accessions in East Asia.

2.2. Genotype Data and Quality Control

This set of 1,032 G. soja accessions was previously genotyped with the Illumina SoySNP50k iSelect BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA. USA) and contained a total of 52,041 SNPs (Song et al. 2013; Song et al. 2015). The SNP data for this set of population are available and can be retrieved from the public SoyBase database (http://soybase.org/). During the quality control process, SNPs without a physical position on 20 chromosomes, with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 5% and a missing rate > 10% were eliminated from further analysis.

2.3. Population Structure and Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

The STRUCTURE (version 2.3.4) program was used to estimate the population structure with the Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo model (MCMC) (Hubisz et al. 2009). The burn-in length of the 10,000 MCMC iterations and the subsequent 50,000 iterations were used to estimate the parameters. Three replicates were performed for each K value (K = 2 – 8). The true K value was determined by a web tool called STRUCTURE HARVESTER, as described by Earl and Vonholdt (2012). A kinship matrix was calculated using TASSEL version 5.0 (Bradbury et al. 2007) to determine relatedness among individuals. Pairwise LD between SNP markers was calculated with squared allele frequency correlations (r2) in TASSEL version 5.0 (Bradbury et al. 2007).

2.4. Genome-Wide Association Analysis

Genome-wide association analysis was performed with a mixed linear model (MLM) in R package GAPIT (Lipka et al. 2012). The average value of SCN Female Index (FI) value per accession was used as phenotype for GWAS analysis as previously described (Arelli et al. 2000; Vuong et al. 2015). The Q matrix generated from STRUCTURE and a kinship matrix were used to account for population structure and kinship, respectively. We also ran the GWAS without using the Q matrix to control population structure, and both models (with and without the Q matrix) generated similar results. We then used permutation as previously described (Zhang et al. 2015a; Zhang et al. 2015b) to determine the significance threshold with the empirical significance value (p <0.001).

2.5. Candidate Gene Prediction

Genes located within 50 kb on both sides of the significant SNPs were selected as the source for candidate gene identification as previously described (Zhang et al. 2016b). Annotations for the gene list and protein sequences could be retrieved from the public database Phytozome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov). Functional annotation for each gene were also conducted using Blast2GO software (Conesa et al. 2005) or through reference annotation of the Williams 82 soybean reference genome G. max Wm82.a2.1 (SoyBase, http://soybase.org/), as well as previously published literatures. Genes localized with significant SNPs or with functional descriptions relevant to disease resistance were regarded as candidate genes involved in the G. soja response to SCN race 1.

3. Results

3.1. Variation in G. soja Response to Race 1 Infection

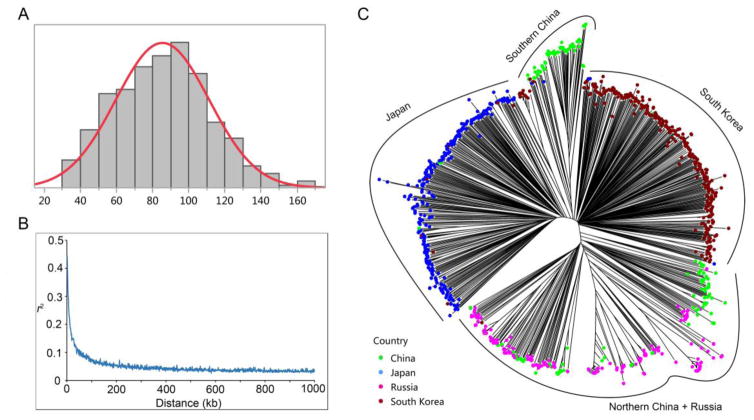

The set of 1,032 G. soja accessions used in this study represents 88.3% of the USDA wild soybean germplasm collection (1,168 accessions) (http://www.ars-grin.gov/). The phenotype data showed a wide range of variation in the G. soja response to race 1 infection in this studied population. The FI values of 1,032 G. soja accessions ranged from 30 to 168.3, with an average FI value of 76.8 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Analysis of female index (FI) distribution and estimated population structure. (A) Distribution of FI among 1,032 G. soja accessions. (B) Genome-wide average LD decay for the association panel. (C) Unrooted neighbor-joining tree of 1,032 G. soja accessions. Colored dots represent the country of origin of G. soja accessions.

3.2. SNP data and LD in G. soja population

A SoySNP50K Illumina Infinium II BeadChip containing 52,041 SNPs was used to genotype the G. soja population. As a result, a total of 41,087 SNPs were polymorphic among the 1,032 G. soja accessions. After quality control, 31,019 SNPs with a minor allele frequency ≥ 5% and a miss rate > 10% were saved for further analyses. The SNP markers ranged from 1,643 on chromosome 20 to 3,221 on chromosome 18, with an average of 1,550 for each soybean chromosome. Accordingly, the SNP density across chromosomes ranged from 17.2 kb on chromosome 13 to 33.08 kb on chromosome 1, with an average genome-wide SNP density of one SNP per 23 kb. The trend of LD decay by plotting r2 against distances (kb) between SNP pairs showed that the LD decays quite rapidly (Figure 2B). The LD decay rate (the distance where the maximum r2 drop to half of its value) was estimated as 10 kb.

3.3. Population structure

To understand the genetic relationships among the 1,035 G. soja accessions, a model-based Bayesian clustering method was used to characterize the population structure. The results from STRUCTURE HARVESTER (Earl and Vonholdt 2012) indicated that the highest ΔK value was observed at K= 4 (Figure S1B), suggesting that this population contains four subgroups (Figure S1A). To further understand population stratification in this G. soja population, an NJ tree for the 1,032 accessions was constructed. As shown in Figure 2C, the resulting NJ tree clustered the 1,032 accessions into four groups, with accessions from Japan and South Korea each forming a group, accessions from northern China and Russia sharing one larger group, and accessions from southern China clustering in a smaller group. These results indicate a high correlation between geographical origin and population structure in the G. soja population, which is also observed in the G. max population (Zhang et al. 2015a). The consistency of the structure in the two analyses was also manually checked, and the four clusters identified by the NJ tree are consistent with the population stratification observed with STRUCTURE. For example, as observed in NJ tree, accessions from South Korea (red) and Japan (blue) were also primarily assigned into two major groups in STRUCTURE result, while accessions from Northern (yellow) and Central China (green) were separately grouped (Figure S1A). Thus, it is appropriate to classify this set of sample into four groups, which can appropriately account for the population structure.

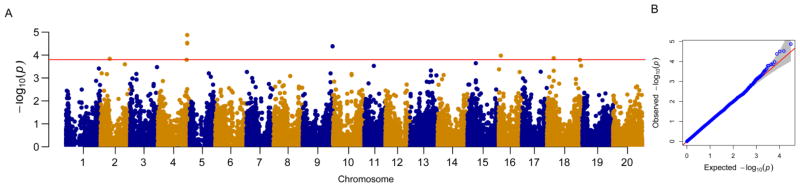

3.4. Association Mapping

Association analysis were performed using the MLM model in GAPIT with the population structure controlled by the Q matrix (K = 4) from STRUCTURE and familial relatedness. After 1,000 permutations, the SNP markers were identified as significantly associated with the response to SCN race 1 infection using a threshold of −Log (P-value) ≥ 3.64. As a result, a total of ten SNPs significantly associated with the G. soja response to race 1 infection were identified. These significant SNPs are located on five chromosomes (2, 4, 9, 16, and 18) (Figure 3, Table 1). Of the ten significant SNPs, four are clustered on chromosome 4 and two are grouped on chromosome 18. Many of the significant SNPs are located within the previously identified QTLs. For example, the significant SNPs, ss715628474 and ss715628480, on chromosome 4 are localized within two previously mapped QTLs, SCN 18-5 and SCN 19-4 (Yue et al. 2001); ss71561958 on chromosome 18 is located within a known QTL SCN 37-2 (Vuong et al. 2010). The other seven significant SNPs without co-localization in known QTLs related to SCN resistance are regarded as novel. The ten SNPs explained 11.42–11.84% of the total phenotypic variation.

Figure 3.

Genome-wide association analysis of G. soja response to race 1 infection. (A) Manhattan plot for SCN response. The red horizontal line represents the empirical threshold (P < 10−3.64) defined by 1,000 permutations of the association analysis. (B) Quantile-Quantile plot using MLM.

TABLE 1.

Significant SNPs and predicted candidate genes associated with G. soja response to race 1

| SNP | Chr | Position (bp) | P-value | MAF | R2 (%) | QTLs | Gene model | Functional description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ss715581323 | 2 | 15021137 | 1.45E-04 | 0.29 | 11.43 | - | Glyma.02G145200 | Kinase interacting family protein |

| ss715588479 | 4 | 47369068 | 1.61E-04 | 0.47 | 11.42 | - | Glyma.04G200900 | Glycosyl hydrolase family 38 protein |

| ss715588590 | 4 | 48326088 | 1.34E-05 | 0.50 | 11.84 | - | Glyma.04G211300 | S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase |

| ss715588591 | 4 | 48326829 | 2.95E-05 | 0.46 | 11.71 | - | Glyma.04G211000 | Calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding protein |

| ss715588601 | 4 | 48369151 | 3.11E-05 | 0.36 | 11.70 | - | Glyma.04G211400 | Leucine-rich repeat protein kinase family protein |

| ss715604994 | 9 | 49421689 | 4.14E-05 | 0.22 | 11.65 | - |

Glyma.09G278900 Glyma.09G279100 |

RNA polymerase II large subunit cytochrome P450 family protein |

| ss715624650 | 16 | 3378162 | 1.06E-04 | 0.17 | 11.49 | - | - | - |

| ss715628474 | 18 | 10902721 | 1.36E-04 | 0.08 | 11.45 | (Yue et al., 2001) | Glyma.18G102600 | Disease resistance protein (NB-ARC domain) |

| ss715628480 | 18 | 10923245 | 1.36E-04 | 0.08 | 11.45 | (Yue et al., 2001) | Glyma.18G102600 | Disease resistance protein (NB-ARC domain) |

| ss715631958 | 18 | 53922753 | 1.62E-04 | 0.44 | 11.42 | (Vuong et al., 2010) | Glyma.18G252200 | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 13 |

| Glyma.18G252300 | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 13 | |||||||

| Glyma.18G252400 | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 13 | |||||||

| Glyma.18G278200 | NSP-interacting kinase 1 |

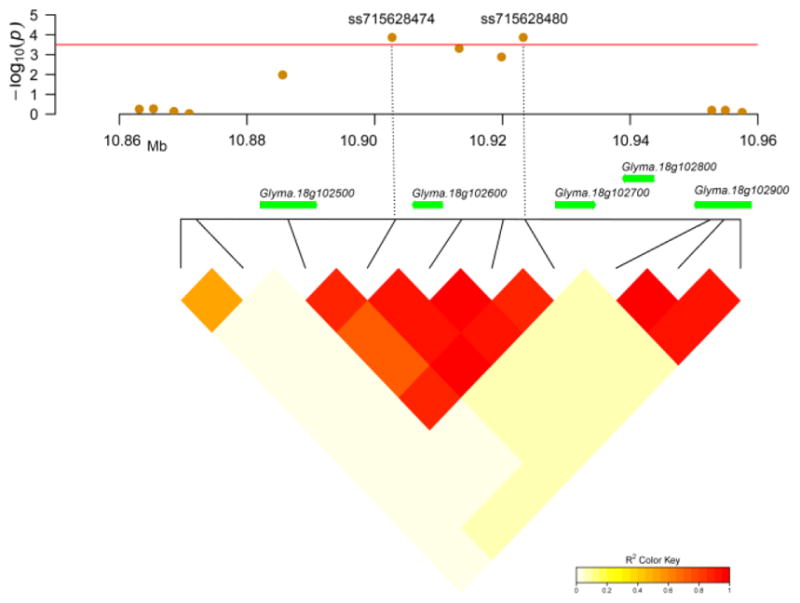

3.5. Candidate Genes Associated with the G. soja Response to SCN Race 1 Infection

To further understand the molecular mechanism of the G. soja response to race 1 infection, genes located in or close to significant SNPs were evaluated. Four soybean genes were located within the SNP regions (Table 1) and were thus considered the most likely candidate genes underlying the G. soja response to SCN race 1. Another six SNPs were located in intergenic regions. In addition, genes within 50 kb at either side of significant SNPs were also retrieved, as previously described (Zhang et al. 2016b). As a result, a total of 83 gene models were predicted within the search region (Table S2), thirteen of which might be involved in plant disease resistance based on reference annotations and results from published literature (Table 1). This candidate list includes genes encoding calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding protein, leucine-rich repeat protein kinase family protein, nucleotide-binding (NB)-ARC domains-containing protein, ethylene-responsive element binding factor, and cytochrome P450 family protein.

It is important to note that the gene Glyma.18G102600 on chromosome 18 was regarded as a highly promising candidate gene involved in G. soja responding to SCN race 1 infection because this gene is located in a strong LD block (average r2 = 0.88) harboring two significant SNPs, ss715628474 and ss71568480 (Figure 4). Glyma.18G102600 encodes an NB-ARC domains-containing protein, a typical disease resistance protein involved in pathogen recognition and activation of the innate immune response (Van Ooijen et al. 2008).

Figure 4.

Regional plot and candidate gene for loci ss715628474 and ss715628480. The top panel shows the regional Manhattan plot for significant loci ss715628474 and ss715628480 and their adjacent loci on chromosome 18. The corresponding genes within the regional plot are drawn in green arrows in the middle panel. The putative disease resistance gene Glyma.18g102600 encoding an NB-ARC protein is regarded as a candidate gene. The LD pattern in this region is illustrated by an LD triangle based on a pairwise r2-value that is drawn at the bottom pane. The r2-values in the LD block are indicated with a color key index.

4. Discussion

4.1. Applying wild soybeans to improve soybean resistance to SCN

Novel and exotic resources with rich genetic diversity are crucial in managing crop pest damage due to evolutionary arms races. Pest-resistant cultivars will gradually lose their resistance after many years; pests, especially pathogens and viruses, can evolve rapidly because of their short life cycles and the selection pressure from host plants. To date, most pest-resistant cultivars have been developed using the gene pool of cultivated crops. It is known that the genetic diversity in modern cultivated crops has been substantially reduced during domestication (Hyten et al. 2006), whereas their wild relatives retain much higher genetic diversity. The promising potential of wild relatives in crop improvement has been gradually recognized in recent decades, and their application for crop improvement is well documented (Zhang et al. 2016a). In G. soja, the identification of superior characteristics in abiotic stress tolerance (Qi et al. 2014) and biotic stress resistance (Tian and Smith 2015) suggests that G. soja harbor promising novel genetic resources in biotic and abiotic resistance/tolerance. As expected, over a dozen of G. soja accessions were identified resistant to HG type 2.5.7 (race 5) in recent studies (Kim et al. 2011; Kim and Diers 2013; Zhang et al. 2016b). However, no G. soja resistance showed high levels of resistance to race 1 (FI<10). This lack of resistance might be due to the completely distinct molecular mechanisms of G. soja defending against race 5 (HG type 2.5.7) vs. race 1. Our recent study (Zhang et al. (2016b) identified different SNPs and candidate genes involved in G. soja resistant to race 5 (type 2.5.7) compared to this current study on SCN race 1.

The continuous distribution of FI values suggests that the G. soja response to SCN race 1 is quantitatively controlled, which can involve many genes and the interactions between them. Although no G. soja accessions showed FI value < 10, which is not quite useful for breeding scientists, it is such a large population with wide variation in resistance levels. Thus, together with large genomic data available, this is useful population to understand the genetic basis of resistance variation in G. soja, which is our main aim in this study. To date, the majority of QTLs underlying SCN resistance have been identified from linkage mapping cultivated soybeans (Concibido et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2009; Vuong et al. 2010; Han et al. 2015; Vuong et al. 2015), which can only capture the variation of the two parental individuals. It is not surprising that some of the significant SNPs identified in our study are not located within the previously identified QTLs underlying SCN resistance as this studied populations capture diversity from over a thousand of accessions, rather than two parents. Indeed, we expect to identify novel SNPs or candidate genes in G. soja as it is a genetically different species from cultivated soybean (G. max), and the former also harbors much higher genomic diversity than the latter. Identification of the genomic regions responsible for the race 1 response in our study might provide a novel understanding of the genetic architecture of the G. soja response to SCN. Nevertheless, our study provides several genomic regions that might be response to the large variation of G. soja resistance to SCN race 1, and the two loci on chromosome 18 are promising candidate markers deserving further investigation.

4.2. Candidate Genes Involved in G. soja Response to SCN Race 1

The current knowledge of SCN resistance genes stem from the identification of two key loci, rhg1 (Cook et al. 2014) and Rhg4 (Liu et al. 2012). These studies indicated that a copy number of three tandem genes (an amino acid transporter, an alpha-SNAP, and a WI12 protein) (rhg1) and a serine hydroxymethyltransferase function (Rhg4) in SCN resistance. These findings were not consistent with the results that plant resistance to pathogens or pests is controlled by canonical NB-ARC or NBS-LRR-type genes (Cheng and Li 2012). The rhg1 and Rhg4 genes were not identified among the 83 gene models within the search regions of the significant SNPs in this study. Explanations include: 1) the genetic architecture of most quantitative traits is very complex and population-specific, with different QTLs/candidate genes for the same trait identified in different populations and/or species. The wild soybean used here is the closest wild relative of cultivated soybean, but has a substantially higher level of genetic diversity. We therefore did not expect to find the same SNPs/genes controlling the SCN response to race1 in our sample as those previously discovered in the cultivated soybean populations. 2) This result may simply be a reflection of a lack of sufficiently close SNP markers. The linkage disequilibrium blocks in wild soybean populations are much smaller than those in domesticated soybean samples. 3) The frequency of the responsible alleles might be very low, and GWAS fails to detect them (Auer and Lettre, 2015).

Previous studies have indicated that protein kinases show a broad spectrum of resistance to diverse invading pathogens (Song et al. 1995; Gomez-Gomez and Boller 2000). Mutation of a receptor-like protein kinase, RPK2, results in a decrease in both nematode infection and syncytium size in the rpk2 mutant (Replogle et al. 2013), which suggests the important roles of kinase in nematode resistance. However, plants trigger a cascade of defense signals once they encounter environmental stress. The calcium-mediated regulation of plant immunity (Lecourieux et al. 2006) and plant phytohormones, such as ethylene (Lorenzo et al. 2003), are two important regulatory mechanisms involved in plant defense signaling that subsequently trigger a battery of defense actions. In our recent studies using transcriptome profiling to characterize the molecular mechanism of the soybean-SCN interaction, significant changes in the expression of genes participating in calcium and ethylene-related pathways were observed, suggesting that calcium and ethylene play important roles in soybean defense against or response to SCN infection (Klink et al. 2007b; Klink et al. 2007a; Kandoth et al. 2011). Calcium- and ethylene-mediated plant defense signaling was recently verified conserved in the plant defenses against nematodes, as previously described (Manosalva et al. 2015).

Plant R proteins have been extensively studied in plant defenses against diverse pathogens and pests (Van Ooijen et al. 2008; Cheng and Li 2012). However, to date, the major SCN-resistant genes are not canonical NBS-LRR or NB-ARC genes; several types of R genes were identified as resistant to other nematodes in various plants (Williamson and Kumar 2006). In addition, a significant change in R gene expression in soybean roots was observed after SCN infection (Klink et al. 2007b; Guo et al. 2015). Thus, the putative disease-resistant R gene (Glyma.18G102600) that was identified in a strong LD block harboring two significant SNPs might be a promising candidate gene meriting further investigation.

Supplementary Material

(A) The population structure of 1,302 wild soybean accessions based on 10,000 SNPs. (B) Calculation of the true K of 1,035 accessions according to STRUCTURE HARVESTER (Earl and Vonholdt 2012).

Accession ID, country of origin, maturity group, and Female Index (FI) of the 1,032 G soja accessions used in this study.

A gene list containing 83 genes that were identified within a 50 kb region of both sides of the ten significant SNPs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. We also thank Dr. Jiaoping Zhang at Iowa State University for his great assistance in performing permutation and Dr. Arelli Prakash for helpful discussion.

Funding: This study was funded by The National Institute Of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, Award Number: R15GM122029; North Carolina Biotechnology Center, Award number: 2014-CFG-8005; Charlotte Research Institute, Award Number: 1603-020; University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Abbreviations

- SCN

soybean cyst nematode

- HG

Heterodera glycines

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- QTL

Quantitative Trait Loci

- NB-ARC

nucleotide-binding adaptor shared by Apaf-1, Resistance proteins, and CEO-4

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- CWR

Crop wild relatives

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- LRR

leucine-rich repeat

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Availability of data and material

The datasets analyzed during the current study can be retrieved in the publically accessible database: http://www.soybase.org/.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Arelli PR, Sleper DA, Yue P, Wilcox JA. Soybean reaction to Races 1 and 2 of Heterodera glycines. Crop Sci. 2000;40:824–826. [Google Scholar]

- Auer PL, Lettre G. Rare variant association studies: considerations, challenges and opportunities. Genome Med. 2015;7:16. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0138-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2633–2635. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YT, Li X. Ubiquitination in NB-LRR-mediated immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concibido VC, Diers BW, Arelli PR. A decade of QTL mapping for cyst nematode resistance in soybean. Crop Sci. 2004;44:1121–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DE, Bayless AM, Wang K, Guo XL, Song QJ, Jiang JM, Bent AF. Distinct copy number, coding sequence, and locus methylation patterns underlie Rhg1-mediated soybean resistance to soybean cyst nematode. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:630–647. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.235952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl DA, Vonholdt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012;4:359–361. [Google Scholar]

- Golden AM, Epps JM, Riggs RD, Duclos LA, Fox JA, Bernard RL. Terminology and identity of infraspecific forms of the soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) Plant Dis Rep. 1970;54:544–546. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T. FLS2: An LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell. 2000;5:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Sleper DA, Nguyen HT, Arelli PR, Shannon JG. Quantitative trait loci underlying resistance to three soybean cyst nematode populations in soybean PI 404198A. Crop Sci. 2006;46:224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Guo XL, Chronis D, De La Torre CM, Smeda J, Wang XH, Mitchum MG. Enhanced resistance to soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines in transgenic soybean by silencing putative CLE receptors. Plant Biotechnol J. 2015;13:801–810. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YP, Zhao X, Cao GL, Wang Y, Li YH, Liu DY, Teng WL, Zhang ZW, Li DM, Qiu LJ, Zheng HK, Li WB. Genetic characteristics of soybean resistance to HG type 0 and HG type 1.2.3.5.7 of the cyst nematode analyzed by genome-wide association mapping. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:598. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1800-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubisz MJ, Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9:1322–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyten DL, Song QJ, Zhu YL, Choi IY, Nelson RL, Costa JM, Specht JE, Shoemaker RC, Cregan PB. Impacts of genetic bottlenecks on soybean genome diversity. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16666–16671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604379103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandoth PK, Ithal N, Recknor J, Maier T, Nettleton D, Baum TJ, Mitchum MG. The soybean Rhg1 locus for resistance to the soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines regulates the expression of a large number of stress- and defense-related genes in degenerating feeding cells. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1960–1975. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.167536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Diers BW. Fine Mapping of the SCN Resistance QTL cqSCN-006 and cqSCN-007 from Glycine soja PI 468916. Crop Sci. 2013;53:775–785. [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Hyten DL, Niblack TL, Diers BW. Stacking rsistance alleles from wild and domestic soybean sources improves soybean cyst nematode resistance. Crop Sci. 2011;51:2301–2301. [Google Scholar]

- Klink VP, Overall CC, Alkharouf NW, MacDonald MH, Matthews BF. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) and comparative microarray expression analysis of syncytial cells isolated from incompatible and compatible soybean (Glycine max) roots infected by the soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) Planta. 2007a;226:1389–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0578-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink VP, Overall CC, Alkharouf NW, MacDonald MH, Matthews BF. A time-course comparative microarray analysis of an incompatible and compatible response by Glycine max (soybean) to Heterodera glycines (soybean cyst nematode) infection. Planta. 2007b;226:1423–1447. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecourieux D, Raneva R, Pugin A. Calcium in plant defence-signalling pathways. New Phytol. 2006;171:249–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Peng ZY, Yang XH, Wang WD, Fu JJ, Wang JH, Han YJ, Chai YC, Guo TT, Yang N, Liu J, Warburton ML, Cheng YB, Hao XM, Zhang P, Zhao JY, Liu YJ, Wang GY, Li JS, Yan JB. Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of oil biosynthesis in maize kernels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipka AE, Tian F, Wang QS, Peiffer J, Li M, Bradbury PJ, Gore MA, Buckler ES, Zhang ZW. GAPIT: genome association and prediction integrated tool. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2397–2399. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SM, Kandoth PK, Warren SD, Yeckel G, Heinz R, Alden J, Yang CL, Jamai A, El-Mellouki T, Juvale PS, Hill J, Baum TJ, Cianzio S, Whitham SA, Korkin D, Mitchum MG, Meksem K. A soybean cyst nematode resistance gene points to a new mechanism of plant resistance to pathogens. Nature. 2012;492:256–260. doi: 10.1038/nature11651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo O, Piqueras R, Sanchez-Serrano JJ, Solano R. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 integrates signals from ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Plant Cell. 2003;15:165–178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manosalva P, Manohar M, von Reuss SH, Chen SY, Koch A, Kaplan F, Choe A, Micikas RJ, Wang XH, Kogel KH, Sternberg PW, Williamson VM, Schroeder FC, Klessig DF. Conserved nematode signalling molecules elicit plant defenses and pathogen resistance. Nat Commun. 2015:6. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchum MG, Wrather JA, Heinz RD, Shannon JG, Danekas G. Variability in distribution and virulence phenotypes of Heterodera glycines in Missouri during 2005. Plant Dis. 2007;91:1473–1476. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-91-11-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GP, Ramu P, Deshpande SP, Hash CT, Shah T, Upadhyaya HD, Riera-Lizarazu O, Brown PJ, Acharya CB, Mitchell SE, Harriman J, Glaubitz JC, Buckler ES, Kresovich S. Population genomic and genome-wide association studies of agroclimatic traits in sorghum. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:453–458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215985110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niblack TL, Arelli PR, Noel GR, Opperman CH, Ore JH, Schmitt DP, Shannon JG, Tylka GL. A revised classification scheme for genetically diverse populations of Heterodera glycines. J Nematol. 2002;34:279–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niblack TL, Colgrove AL, Colgrove K, Bond JP. Shift in virulence of soybean cyst nematode is associated with use of resistance from PI 88788. Plant Health Progress. 2008 doi: 10.1094/PHP-2008-0118-01-RS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niblack TL, Noel GR, Lambert KN. The Illinois SCN type test: Practical application of the HG type classification system. J Nematol. 2003;35:355. [Google Scholar]

- Qi XP, Li MW, Xie M, Liu X, Ni M, Shao GH, Song C, Yim AKY, Tao Y, Wong FL, Isobe S, Wong CF, Wong KS, Xu CY, Li CQ, Wang Y, Guan R, Sun FM, Fan GY, Xiao ZX, Zhou F, Phang TH, Liu X, Tong SW, Chan TF, Yiu SM, Tabata S, Wang J, Xu X, Lam HM. Identification of a novel salt tolerance gene in wild soybean by whole-genome sequencing. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4340. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Replogle A, Wang JY, Paolillo V, Smeda J, Kinoshita A, Durbak A, Tax FE, Wang XH, Sawa S, Mitchum MG. Synergistic interaction of CLAVATA1, CLAVATA2, and RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE 2 in cyst nematode parasitism of Arabidopsis. Mol Plant Microbe In. 2013;26:87–96. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-12-0118-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q, Hyten DL, Jia G, Quigley CV, Fickus EW, Nelson RL, Cregan PB. Fingerprinting soybean germplasm and its utility in genomic research. G3 (Bethesda) 2015;5:1999–2006. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.019000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song QJ, Hyten DL, Jia GF, Quigley CV, Fickus EW, Nelson RL, Cregan PB. Development and evaluation of SoySNP50K, a high-density genotyping array for soybean. Plos One. 2013;8:e54985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WY, Wang GL, Chen LL, Kim HS, Pi LY, Holsten T, Gardner J, Wang B, Zhai WX, Zhu LH, Fauquet C, Ronald P. A receptor kinase-like protein encoded by the rice disease resistance gene, Xa21. Science. 1995;270:1804–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian P, Smith SM. Characterization of soybean and its wild relatives host resistance and Asian soybean rust (ASR) pathogen variability for durable resistance. Phytopathology. 2015;105:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tylka GL, Marett CC. Distribution of the soybean cyst nematode, Heterodera glycines, in the United States and Canada: 1954 to 2014. Plant Health Brief. 2014;15:13. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen G, Mayr G, Kasiem MMA, Albrecht M, Cornelissen BJC, Takken FLW. Structure-function analysis of the NB-ARC domain of plant disease resistance proteins. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;59:1383–1397. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong TD, Sleper DA, Shannon JG, Nguyen HT. Novel quantitative trait loci for broad-based resistance to soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines Ichinohe) in soybean PI 567516C. Theor Appl Genet. 2010;121:1253–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong TD, Sonah H, Meinhardt CG, Deshmukh R, Kadam S, Nelson RL, Shannon JG, Nguyen HT. Genetic architecture of cyst nematode resistance revealed by genome-wide association study in soybean. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:593. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1811-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZX, Tan RJ, Yuan JZ, Bales C, Du WY, Zhang SC, Chilvers MI, Schmidt C, Song QJ, Cregan PB, Wang DC. Genome-wide association mapping of quantitative resistance to sudden death syndrome in soybean. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:809. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson VM, Kumar A. Nematode resistance in plants: the battle underground. Trends Genet. 2006;22:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstead NN, Skotland CB, Sasser JN. Soybean cyst nematodes in North Carolina. Plant Dis Rep. 1955;39:911. [Google Scholar]

- Wrather JA, Koenning SR. Estimates of disease effects on soybean yields in the United States 2003 to 2005. J Nematol. 2006;38:173–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XL, Blake S, Sleper DA, Shannon JG, Cregan P, Nguyen HT. QTL, additive and epistatic effects for SCN resistance in PI 437654. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;118:1093–1105. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-0965-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue P, Arelli PR, Sleper DA. Molecular characterization of resistance to Heterodera glycines in soybean PI438489B. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;102:921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Yue P, Sleper DA, Arelli PR. Genetic analysis of resistance to soybean cyst nematode in PI438489B. Euphytica. 2000;116:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Mittal N, Leamy L, Barazani O, Song B-H. Back into the wild – Apply untapped genetic diversity of wild relatives for crop improvement. Evolutionary Applications. 2016a;10:5–24. doi: 10.1111/eva.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HY, Li CY, Davis EL, Wang JS, Griffin JD, Kofsky J, Song BH. Genome-wide association study of resistance to soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) HG Type 2.5.7 in wild soybean (Glycine soja) Front Plant Sci. 2016b;7:1214. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JP, Singh A, Mueller DS, Singh AK. Genome-wide association and epistasis studies unravel the genetic architecture of sudden death syndrome resistance in soybean. Plant J. 2015a;84:1124–1136. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JP, Song QJ, Cregan PB, Nelson RL, Wang XZ, Wu JX, Jiang GL. Genome-wide association study for flowering time, maturity dates and plant height in early maturing soybean (Glycine max) germplasm. BMC Genomics. 2015b;16:217. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1441-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZK, Jiang Y, Wang Z, Gou ZH, Lyu J, Li WY, Yu YJ, Shu LP, Zhao YJ, Ma YM, Fang C, Shen YT, Liu TF, Li CC, Li Q, Wu M, Wang M, Wu YS, Dong Y, Wan WT, Wang X, Ding ZL, Gao YD, Xiang H, Zhu BG, Lee SH, Wang W, Tian ZX. Resequencing 302 wild and cultivated accessions identifies genes related to domestication and improvement in soybean. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:408–414. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) The population structure of 1,302 wild soybean accessions based on 10,000 SNPs. (B) Calculation of the true K of 1,035 accessions according to STRUCTURE HARVESTER (Earl and Vonholdt 2012).

Accession ID, country of origin, maturity group, and Female Index (FI) of the 1,032 G soja accessions used in this study.

A gene list containing 83 genes that were identified within a 50 kb region of both sides of the ten significant SNPs.