Abstract

Objective

Evaluate blood mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content in HIV/antiretroviral (ARV)-exposed uninfected (HEU) vs. HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) infants and investigate differences in mitochondrial-related metabolites by exposure group.

Design

We enrolled a prospective cohort of HIV-infected and -uninfected pregnant woman/infant pairs in Cameroon.

Methods

Dried blood spot mtDNA:nuclear DNA ratio was measured by monochrome multiplex qPCR in HEU infants exposed to in utero ARVs and postnatal zidovudine (HEU-Z) or nevirapine (HEU-N), and in HUU infants at 6 weeks of life. Acylcarnitines (ACs) and branch-chain amino acids (BCAAs) were measured via tandem mass spectrometry and consolidated into 7 uncorrelated components using principal component analysis (PCA). Linear regression models were fit to assess the association between in utero/postnatal HIV/antiretroviral exposure and infant mtDNA, adjusting for confounders and PCA-derived AC/BCAA component scores.

Results

Of 364 singleton infants, 38 were HEU-Z, 117 HEU-N, and 209 HUU. Mean mtDNA content was lowest in HEU-Z infants (140 vs. 160 in HEU-N vs. 174 in HUU, p=0.004). After adjusting for confounders, HEU-Z infants remained at increased risk for lower mtDNA content compared to HUU infants (β: −4.46, p=0.045), while HEU-N infants did not, compared to HUU infants (β: −1.68, p=0.269. Furthermore, long-chain ACs were associated with lower (β:−2.35, p=0.002) and short-chain and BCAA-related ACs were associated with higher (β:2.96, p=0.001) mtDNA content.

Conclusion

Compared to HUU infants, HEU infants receiving postnatal zidovudine appear to be at increased risk for decreased blood mtDNA content which may be associated with altered mitochondrial fuel utilization in HEU-Z infants.

keywords/Phrases: HIV-exposed infants, mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA, acylcarnitines, branched-chain amino acids, zidovudine infant prophylaxis

Introduction

In 1999, one of the first reports of clinical mitochondrial dysfunction in infants exposed to HIV and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) emerged, demonstrating neurological impairment in these infants.[1] Since then, concern has evolved regarding the short- and long-term effects of in utero ARVs on the developing fetus. Several studies have shown abnormalities in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content,[2–8] aberrant mitochondrial morphology,[1, 3] respiratory chain compromise,[8, 9] and also significant mitochondriopathy presenting as seizures, cognitive delays, motor and cardiac dysfunction, and even death.[1, 10]

Definitive assessment of mitochondrial dysfunction is difficult and requires direct measurement of mitochondrial respiration which is not always feasible. Therefore, several studies have evaluated other aspects of mitochondria such as mitochondrial histology,[1, 3] DNA content,[2–5] and OXPHOS enzyme activity.[8, 9] Another aspect of mitochondrial health includes the biochemical reactions which produce cellular metabolites or energy and localize to the mitochondria such as fatty-acid oxidation, glycolysis, and parts of amino-acid catabolism. Intermediary metabolites involved in these metabolic pathways include, but are not limited to, acylcarnitines (ACs) and amino acids (AAs), the latter of which includes branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). Studies have demonstrated that HIV/ARV-exposed uninfected (HEU) infants exhibit higher rates of abnormal AC profiles than the general population.[11, 12] Moreover, we have also previously described a signature array of short-chain ACs and BCAAs in association with insulin resistance in HEU infants.[13] Few studies have evaluated mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content or the relationship between mtDNA levels and pathways of intermediary metabolism in HEU compared to HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) infants in Africa. Given that approximately 20% of the general pediatric population is currently HEU in sub-Saharan Africa, [14] we sought to assess mtDNA content in HEU infants in Cameroon and investigate its relationship with intermediary metabolites.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Between 2011–2014, HIV-infected and -uninfected pregnant woman/infant pairs were enrolled at the Nkwen Family Care and Treatment Center, within the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services (CBCHS) consortium. This was a prospective cohort study where pregnant women were enrolled between 20 and 36 weeks gestation and followed through delivery until the infant reached 12 months of age. Blood specimens were collected on infants at 6 weeks of life, and subsequent study visits occurred at 6 months and 12 months after delivery. The design of this study has been previously reported.[13] Multiple gestation pregnancies and those ending in spontaneous/therapeutic abortions or intra-uterine fetal demise, as well as infants with HIV infection by positive DNA PCR testing at 6 weeks of life were excluded. During the study period, national guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) underwent changes, reflecting updated WHO Guidelines.[15, 16] At study initiation, national PMTCT guidelines recommended that HIV-infected pregnant women with a CD4 cell count ≤350 cells/mm3 or WHO Stage III/IV disease be eligible for lifetime combination antiretroviral treatment (ART) while their infants received nevirapine for 4–6 weeks after birth. Pregnant women with a CD4 >350 cells/mm3 received prenatal zidovudine monotherapy plus single dose nevirapine intrapartum and nevirapine/lamivudine for 1 week postpartum; infant nevirapine prophylaxis was administered until cessation of breastfeeding as women with higher CD4 cell counts were not receiving ART during breastfeeding. During the final year of the study, national guidelines expanded PMTCT services extending lifetime ART eligibility to all HIV-infected pregnant women, regardless of maternal CD4 count, and HIV-exposed infants received prophylactic nevirapine for 6 weeks. First-line ART for pregnant women in Cameroon during the time of the study consisted of zidovudine/lamivudine/nevirapine. In addition, during the study, there were random periods where infant nevirapine shortages occurred throughout the country, and thus zidovudine was administered as infant prophylaxis instead of nevirapine as per national protocols. Because of this, we were able to evaluate and compare a sample population of HEU infants exposed to infant nevirapine vs. zidovudine prophylaxis. All infants in this study were breast-fed. Informed consent was provided by all women for their and their infants’ participation, and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of CBCHS and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Primary Outcome

We measured mtDNA content in dried blood spot (DBS) collected at 6 weeks of life in HEU and HUU infants. DBS specimens were collected via heel stick method, dried appropriately, then shipped at 0°C and stored at −80°C until the time of biochemical assessments. DBS DNA was extracted from six 3-mm discs using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit on the QIAcube (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), using a customized DBS protocol. The extraction yielded 50 μL at typically 2–6 ng/mL. The mtDNA content, expressed as the ratio between mtDNA copy number (D loop region) and the copy number of a single-copy nuclear gene (albumin), was determined using a monochrome multiplex quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR), adapted from a published assay for relative telomere length.[17] DNA extracts were assayed on the LightCycler® 480 (Roche). For each reaction, 2 μL of DNA was added to 8 μL of master mix for final concentrations of 1X FastStart SYBR Green Master (Roche), 1.2 mM EDTA, and 0.9 μM for each of the four primers. (See Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 for primer sequences and thermal-cycling profile). Each extract was assayed in duplicate, and each plate included a standard curve generated by 1:5 serial dilution of two cloned plasmids (one containing the albumin the other the D-loop amplicon, and mixed in a 1:50 albumin:D-loop ratio), as well as two internal controls. The assay’s intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 5% and 8%, respectively.

Primary Exposure of Interest

The primary exposure of interest was in utero/postnatal ARVs. Per maternal serological HIV ELISA testing, infant HIV DNA PCR testing at six-weeks of life, and ART history, infants were categorized as: 1) in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal zidovudine-exposed, uninfected (HEU-Z), 2) in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal nevirapine-exposed, uninfected (HEU-N), and 3) HIV/ARV-unexposed uninfected (HUU). Maternal ART history was assessed via self-report as well as medical and pharmacy record review. Infants were considered exposed to postnatal zidovudine if they received ≥ 4 weeks of zidovudine or exposed to postnatal nevirapine if they received ≥ 4 weeks of nevirapine after birth, prior to insulin assessment at 6 weeks of life.

Covariates

Information on maternal socio-demographics, obstetrical history, and HIV immune status as well as infant birth outcomes and anthropometrics was collected. Infant weight, length, and head circumference were measured in standardized fashion using a recumbent stadiometer, manual scale, and paper tape measures, respectively, by one of two trained research assistants.

Biochemical Measurements

Using an Agilent 6460 tandem mass spectrometry coupled with an Agilent 1260 liquid chromatography system, we measured 37 ACs and three BCAAs (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) from stored DBS specimens which had been collected from infants at 6 weeks of life. ACs and BCAAs were extracted with methanol containing stable isotope internal standards of ACs and BCAAs. Dried AC and BCAA extracts were derivatized with 3 N-Butanolic HCl to form their respective butyl esters. Butyl esters of ACs were analyzed in the positive ion mode using a flow injection program and selective reaction monitoring (SRM) [18]. Butyl esters of BCAAs were separated on Zorbax Eclipse Plus C8 column and analyzed in the positive ion mode and SRM.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of pregnant women and their infants were compared between groups using Kruskal Wallis or Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests as appropriate. Weight-for-age (WAZ), length-for-age (LAZ), weight-for-length (WLZ), and head circumference-for-age (HCAZ) z scores were calculated from WHO 2006 child growth standards [19]. The ratio of mtDNA:nuclear DNA was three-quarter-root transformed using the Box Cox transformation in order to normalize the variable. Principal component analysis (PCA) using an orthogonal rotation was performed as a means of reducing the number of AC and BCAA metabolite variables, converting the 40 possibly correlated metabolites into a set of values of uncorrelated variables defined as principal components. The number of components was chosen based on eigenvalues >1, scree plots, and theoretical congruence with prior knowledge of intermediate metabolic pathways as previously described. [13] Principal component (PC) scores were calculated for each infant as a linear combination of the optimally weighted metabolites (based on standardized scoring coefficients) with each PC score representing the level of activity for a particular mitochondrial metabolic pathway.[13] Correlations between each of the PCs and mtDNA ratio were evaluated using Spearman’s correlation. Lastly, linear regression modeling was applied to assess the association of in utero HIV/ARV plus either postnatal zidovudine or nevirapine with mtDNA content while adjusting for confounders and PCA-derived PC scores of the metabolites. All PCs were forced into the final model in order to fully adjust for and evaluate any residual confounding effects of intermediary metabolites on mtDNA content. In addition, we tested for interactions between infant in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal ARV exposure, and each PC score on the primary outcome. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 364 singleton infants were included in this analysis: 38 were HEU-Z, 117 HEU-N, and 209 HUU infants. Mothers of HEU-Z and HEU-N were older than those of HUU infants (median age 30 vs. 30 vs. 28 years, respectively, p=<0.01) and less likely to have completed a high school education or higher (32% vs. 34% vs. 48% respectively, p=0.023). (Table 1) Amongst HEU infants, 15 (10%) were not exposed to any in utero ARVs, 33 (21%) to in utero zidovudine monotherapy, and 108 (69%) to combination ART. Of those exposed to combination ART, only two were exposed to lopinavir/ritonavir while the remainder were exposed to a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based regimen. The types of in utero ARV exposures did not differ significantly between HEU-Z and HEU-N infants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women and Infants

| HEU-Z Infants (n=38) | HEU-N Infants (n=117) | HUU Infants (n=209) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMEN | ||||

| Age of Mother, years | 30 (27–33) | 30 (27–33) | 28 (24–31) | <0.001 |

| Gravidity | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.019^ |

| Marital Status | 0.070 | |||

| Single | 8 (21.0) | 28 (23.5) | 26 (12.3) | |

| Living with partner | 2 (5.0) | 3 (2.5) | 12 (5.7) | |

| Married | 28 (74.0) | 87 (74.0) | 172 (82.0) | |

| Highest Level of Education | 0.023 | |||

| Secondary school or lower | 26 (68.0) | 78 (66.0) | 110 (52.0) | |

| High school or higher | 12 (32.0) | 40 (34.0) | 100 (48.0) | |

| Gainful Employment | 6 (19.0) | 28 (26.9) | 50 (24.5) | 0.640 |

| Water Source | 0.270 | |||

| Tap water in the home | 4 (10.5) | 20 (17.0) | 44 (20.9) | |

| Community water | 34 (89.5) | 98 (83.0) | 166 (79.1) | |

| Maternal BMI, 6 weeks postpartum, kg/m2 | 24.7 (22.8–27.0) | 26.1 (23.7–28.8) | 25.3 (23.1–29.3) | 0.383 |

| CD4 cell count at enrollment, cells/mm3 | 0.133 | |||

| 0–200 | 5 (13.2) | 32 (27.1) | --- | |

| 201–350 | 12 (31.6) | 26 (22.0) | --- | |

| 351–500 | 11 (28.9) | 21 (17.8) | --- | |

| >500 | 10 (26.3) | 39 (33.1) | --- | |

| ART regimen during pregnancy | 0.465 | |||

| No ARV | 2 (5.3) | 13 (11.0) | --- | |

| Zidovudine monotherapy | 7 (18.4) | 26 (22.0) | --- | |

| Combination ART | 29 (76.3) | 79 (67.0) | --- | |

| C-section delivery | 7 (18.4) | 14 (12.3) | 32 (15.6) | 0.585 |

| INFANTS | ||||

| Female Infant | 16 (42.1) | 60 (51.7) | 109 (52.2) | 0.512 |

| Preterm (<37 weeks GA) | 6 (15.8) | 15 (12.7) | 29 (13.8) | 0.887 |

| Infant Birth Weight, g* | 3200 (2800–3400) | 3400 (3000–3600) | 3300 (3050–3600) | 0.045 |

| Infant LBW, % | 3 (8.0) | 6 (5.1) | 7 (3.3) | 0.404 |

| Infant WAZ at 6 wk | 0.24 (−0.25, +0.85) | 0.10 (−0.57, +0.90) | 0.35 (−0.38, +0.91) | 0.180 |

| Infant LAZ at 6 wk | 0.08 (−0.64, +0.87) | 0.68 (−0.43, +1.73) | 0.92 (−0.12, +1.73) | 0.018 |

| Infant WLZ at 6 wk | 0.36 (−0.31, +1.31) | −0.80 (−1.89, +0.50) | −0.63 (−1.55, +0.51) | 0.002 |

| Infant mtDNA ratio at 6 wk | 140 (118, 175) | 160 (128, 209) | 173 (138, 217) | 0.004 |

All continuous variables shown as Median (IQR) and categorical variables as No. (%). P values for continuous variables from Kruskal Wallis and for categorical variables from Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests as appropriate.

p value confirmed by comparing means between groups via ANOVA [Mean gravidity (number of pregnancies including current pregnancy) = 3.13 amongst mothers of HEU-A infants, 3.58 amongst mothers of HEU-N infants, and 3.07 amongst mothers of HUU infants]

Comparison amongst term infants only (n=350)

ARV= antiretroviral; BMI= Body Mass Index; ART= Antiretroviral Therapy; GA= Gestational Age; HC= Head Circumference; HCAZ= Head Circumference-for-Age z score; HEU-Z= in utero HIV/ARV, postnatal zidovudine-exposed uninfected; HEU-N= in utero HIV/ARV, postnatal nevirapine-exposed uninfected; HUU= HIV/ARV-unexposed uninfected; HOMA-IR= Homeostatic Model Assessment Insulin Resistance; IQR= Interquartile Range; LAZ= Length-for-Age z score; LBW= Low Birth Weight; mtDNA= mitochondrial DNA; WAZ=Weight-for-Age z score; wk=weeks; WLZ= Weight-for-Length z score

As previously described,[13] we used PCA to consolidate and reduce the total number of AC and BCAA metabolites into a smaller number of uncorrelated variables/components. In general, PC1 was comprised of long-chain ACs and free carnitine (C0), PC2 of 3-hydroxy long-chain ACs, PC3 of short-chain and BCAA-related ACs, PC4 of unsaturated medium- and long-chain ACs, PC5 of BCAAs, PC6 of adipoyl/3-methylglutarylcarnitine (C6-DC) and dodecanoylcarnitine (C12) ACs, and PC7 of medium-chain ACs and tetradecenoylcarnitine (C14:1). (Supplemental Table 3)

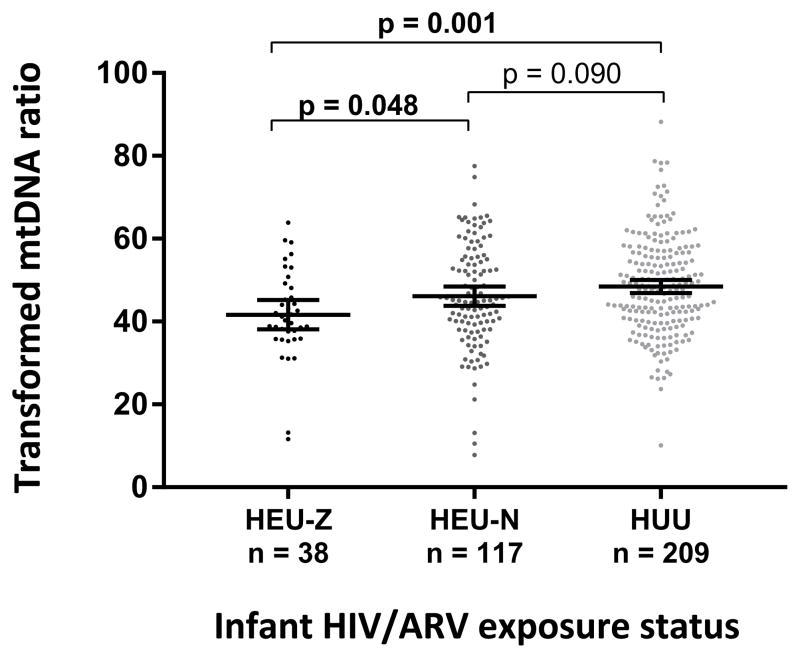

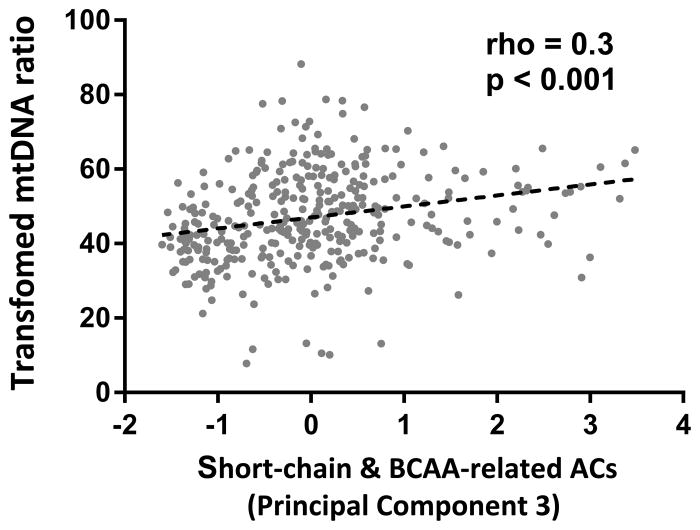

Overall, mtDNA ratio at 6 weeks of life was lowest in HEU-Z followed by HEU-N and highest in HUU infants (140 vs. 160 vs. 174, overall p=0.004; for HEU-Z vs. HUU infants, p=0.001). (Figure 1) This difference remained statistically significant when comparing the mtDNA ratio between HEU-Z and HEU-N infants (p=0.048) but not when comparing HEU-N and HUU infants. PC3 (short chain and BCAA-related ACs) and mtDNA ratio were positively associated (rho=0.3, p<0.001). (Figure 2) No correlation was found between the other PCs and mtDNA ratio in univariate analyses. After adjustment for potential confounders, in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal zidovudine exposure remained associated with a lower mtDNA ratio at 6 weeks of life (β= −4.46, p=0.045 for HEU-Z vs. HUU and β= −1.68, p=0.269 for HEU-N vs. HUU infants). (Table 2) In addition, long-chain ACs and C0 (PC1) were associated with a decreased mtDNA ratio (β= −2.35, p=0.002) while short-chain and BCAA-related ACs were associated with an increased mtDNA ratio (β=2.96, p=0.001). (Figure 2)

Figure 1.

Transformed mitochondrial DNA ratio by infant HIV/ARV exposure status. HEU-Z=in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal zidovudine-exposed uninfected; HEU-N=in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal nevirapine-exposed uninfected; HUU=HIV/ARV unexposed uninfected

Figure 2.

Relationship of short-chain and BCAA-related ACs with transformed mtDNA ratio. ACs=acylcarnitines; BCAA=branched chain amino acids; mtDNA=mitochondrial DNA

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Infant Mitochondrial DNA Ratio

| Effect | β coefficient | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Infant HIV/ARV Exposure Status | ||

| HUU | Ref | -- |

| HEU-N | −1.68 | 0.269 |

| HEU-Z | −4.46 | 0.045 |

| Maternal Age, per year | 0.04 | 0.728 |

| Infant Female Sex | −0.59 | 0.650 |

| Low Birth Weight (<2500 g) | −0.18 | 0.962 |

| Preterm Birth (<37 weeks) | −1.05 | 0.587 |

| Infant WLZ at 6 weeks | −0.07 | 0.832 |

| PC1 - Long-chain ACs & C0 | −2.35 | 0.002 |

| PC2 - 3-Hydroxy Long-chain ACs | 0.05 | 0.943 |

| PC3 - Short-chain & BCAA-related ACs | 2.96 | 0.001 |

| PC4 – Unsaturated Medium- & Long-chain ACs | 0.74 | 0.268 |

| PC5 - BCAAs | 0.63 | 0.338 |

| PC6 - C6-DC and C12 ACs | 1.27 | 0.075 |

| PC7 - Medium-chain ACs and C14:1 | 0.18 | 0.812 |

ACs=acylcarnitines; ARV=antiretrovirals; AZT=zidovudine; BCAAs=branched-chain amino acids; HEU-N=in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal nevirapine-exposed uninfected; HEU-Z=in utero HIV/ARV and postnatal zidovudine-exposed uninfected; HUU=HIV/ARV unexposed uninfected; PC=principal component; WLZ=weight-for-length Z score

Discussion

In this cohort of HEU and HUU infants in Cameroon, we found that in utero HIV/ARV exposure plus postnatal zidovudine was associated with decreased mtDNA content at 6 weeks of life. In addition, lower mtDNA content in HEU-Z infants may be associated with altered mitochondrial fuel utilization.

Despite conflicting results in the literature on mtDNA content in HEU infants,[2–8] our results are consistent with other reports comparing HEU to HUU infants. The Women and Infants Transmission Study (WITS) reported lower mtDNA content in cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) and infant peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of HEU infants exposed in utero to zidovudine compared with HUU infants,[2] while another U.S. study reported similar findings in HEU infants exposed in utero to zidovudine/lamivudine compared with HUU infants.[3] In a large combined analysis of WITS and the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) 1009 Protocol, significantly lower mtDNA was observed in HEU vs HUU infants at birth and 2 years of life with the following in utero exposures demonstrating higher mtDNA levels in increasing order: in utero HIV, but no ARV exposure < in utero HIV plus zidovudine monotherapy exposure < in utero HIV plus zidovudine/lamivudine exposure < HUU infants.[4] Of note, in our cohort, we also observed lower mtDNA levels amongst HEU infants with in utero HIV, but no ARV exposure compared to those with in utero HIV plus zidovudine monotherapy exposure (140 vs. 163, data not shown), but were limited by a small number (n=15) of HEU infants who had no in utero ARV exposures. One small Tanzanian study found similar results showing lower mtDNA levels at birth in CBMCs between infants with in utero HIV, but no ARV exposure vs. in utero HIV plus zidovudine monotherapy exposure. However, this study lacked an HUU comparison group.[7]

In contrast, three North American studies have demonstrated higher mtDNA content in HEU compared to HUU infants.[5, 6, 8] Two were U.S. studies which evaluated mtDNA content from infant PBMCs[6, 8] while the other evaluated mtDNA levels in whole blood.[5] In the North American studies, the majority of participants were exposed to protease inhibitors (PIs), unlike our study where all but two HEU infants were exposed in utero to combination non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) ART. In vitro studies have shown that PIs may potentially increase mtDNA levels.[20] The fact that we observed lower and not higher mtDNA content in our cohort may also be explained by possible racial or ethnic differences. Our participants were all Black African while North American studies often report imbalance between the ethnic make-up of the HUU and HEU groups. It is also important to note that differences in whole blood, PBMC, or CBMC testing may account for some differences in reported results. Lastly, all studies to date have had HEU infants with the same infant prophylaxis, namely zidovudine for the first 4–6 weeks of life. Our study is one of the first to attempt to compare mtDNA content based on infant prophylaxis regimens during the first 6 weeks of life.

In addition to assessing mtDNA content level, we sought to better understand whether lower mtDNA content reflected abnormal mitochondrial fuel utilization. mtDNA polymerase-γ is required for mtDNA replication and has been shown to be inhibited by dideoxy analogue ARVs such as zidovudine, stavudine, and didanosine.[21] In studies of mtDNA polymerase-γ-related disorders, mtDNA depletion has been shown to result in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) dysfunction and respiratory chain compromise of the mitochondria.[22] A reduction in OXPHOS may presumably cause perturbations in fatty-acid oxidation within the mitochondria.[23, 24] As a result, inefficient fatty acid oxidation from decreased mtDNA and mitochondrial dysfunction could manifest by increased levels of long-chain ACs due to substrate back-up, which here we see reflected in the negative association between PC1 and mtDNA in multivariate analysis. AC levels increase, in general, when fuel utilization does not equal fuel supply. The positive association between PC3 and mtDNA seen reflects the decreased levels of short-chain ACs and BCAA-related ACs seen when mtDNA is decreased, a situation indicating ineffective fatty-acid and BCAA oxidation. Both scenarios were observed in our study. Though it is difficult to determine direct causal pathways between decreased mtDNA content and definitive flux of intermediary metabolites, we have demonstrated that decreased mtDNA content in HEU-Z infants appears to be linked to abnormal fuel utilization in the mitochondria, the long-term significance of which is unclear. Given that a substantial proportion of the pediatric population in sub-Saharan Africa is currently born HEU, it will be important to monitor the mitochondrial and metabolic health of this potentially vulnerable population for long-term effects of decreased mtDNA content and potential metabolic sequelae.

Our study is limited by the lack of longitudinal data on mtDNA content, restricting our ability to draw inferences about the long-term consequences of our findings in early infancy. In addition, we were not able to directly assess mitochondrial function. Lastly, because of the observational nature of our study design, we were not able to disentangle the effects of in utero ARV exposure from postnatal ARV exposure. However, no differences were observed in the types of in utero ARV exposure between HEU-Z and HEU-N infants.

In conclusion, compared to HUU infants, HEU infants in Cameroon receiving postnatal zidovudine prophylaxis appear to be at increased risk for decreased blood mtDNA content. Moreover, in our cohort, decreased mtDNA content in HEU-Z infants was associated with altered mitochondrial fuel utilization. Further studies are needed to assess the long-term significance of these findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

This work was supported in part by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Global Health Innovation Fund. JJ is supported by NICHD K23HD070760. KMP was supported by NICHD K23HD070774 during the preparation of this manuscript. MEG is partially supported by the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) which is supported by the NICHD with co-funding from NIAID, NIDA, NIMH, NIDCD, NHLBI, NINDS, and NIAAA, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard University School of Public Health (U01 HD052102-04) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (U01 HD052104-01). IJK was supported by grants NIDDK P60DK020541 (Einstein DRTC) and NIAID 1U19AI091175 (Einstein CMCR) during the preparation of this manuscript.

We would like to thank all the study participants and staff at CBCHS Nkwen Family Care and Treatment Center without whose involvement and support this study would not have been possible. This work was supported in part by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Global Health Innovation Fund. JJ is supported by NICHD K23HD070760. KMP was supported by NICHD K23HD070774 during the preparation of this manuscript. MEG is partially supported by the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) which is supported by the NICHD with co-funding from NIAID, NIDA, NIMH, NIDCD, NHLBI, NINDS, and NIAAA, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard University School of Public Health (U01 HD052102-04) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (U01 HD052104-01). IJK was supported by grants NIDDK P60DK020541 (Einstein DRTC) and NIAID 1U19AI091175 (Einstein CMCR) during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author’s Contributions

JJ and HC conceptualized and designed the study. JJ analyzed the data. JJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and HC made significant edits as well as produced figures. IK, BK, and KP made substantial edits. KMP, BK, CY, FE, EN, EJA, RSS, and DL, MEG reviewed and revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Blanche S, Tardieu M, Rustin P, Slama A, Barret B, Firtion G, et al. Persistent mitochondrial dysfunction and perinatal exposure to antiretroviral nucleoside analogues. Lancet. 1999;354(9184):1084–1089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poirier MC, Divi RL, Al-Harthi L, Olivero OA, Nguyen V, Walker B, et al. Long-term mitochondrial toxicity in HIV-uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(2):175–183. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Divi RL, Walker VE, Wade NA, Nagashima K, Seilkop SK, Adams ME, et al. Mitochondrial damage and DNA depletion in cord blood and umbilical cord from infants exposed in utero to Combivir. AIDS. 2004;18(7):1013–1021. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200404300-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldrovandi GM, Chu C, Shearer WT, Li D, Walter J, Thompson B, et al. Antiretroviral exposure and lymphocyte mtDNA content among uninfected infants of HIV-1-infected women. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1189–1197. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cote HC, Raboud J, Bitnun A, Alimenti A, Money DM, Maan E, et al. Perinatal exposure to antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased blood mitochondrial DNA levels and decreased mitochondrial gene expression in infants. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(6):851–859. doi: 10.1086/591253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McComsey GA, Kang M, Ross AC, Lebrecht D, Livingston E, Melvin A, et al. Increased mtDNA levels without change in mitochondrial enzymes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infants born to HIV-infected mothers on antiretroviral therapy. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9(2):126–136. doi: 10.1310/hct0902-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunz A, von Wurmb-Schwark N, Sewangi J, Ziske J, Lau I, Mbezi P, et al. Zidovudine exposure in HIV-1 infected Tanzanian women increases mitochondrial DNA levels in placenta and umbilical cords. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross AC, Leong T, Avery A, Castillo-Duran M, Bonilla H, Lebrecht D, et al. Effects of in utero antiretroviral exposure on mitochondrial DNA levels, mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. HIV Med. 2012;13(2):98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gingelmaier A, Grubert TA, Kost BP, Setzer B, Lebrecht D, Mylonas I, et al. Mitochondrial toxicity in HIV type-1-exposed pregnancies in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2009;14(3):331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barret B, Tardieu M, Rustin P, Lacroix C, Chabrol B, Desguerre I, et al. Persistent mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV-1-exposed but uninfected infants: clinical screening in a large prospective cohort. AIDS. 2003;17(12):1769–1785. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200308150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirmse BYT, Hofher S, Williams P, Kacanek D, Hazra R, Borkowsky W, Van Dyke R, Summar M. Abnormal Fatty-Acid Oxidation in HIV-Exposed Uninfected Neonates in the United States. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Boston. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirmse B, Hobbs CV, Peter I, Laplante B, Caggana M, Kloke K, et al. Abnormal newborn screens and acylcarnitines in HIV-exposed and ARV-exposed infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(2):146–150. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827030a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jao J, Kirmse B, Yu C, Qiu Y, Powis K, Nshom E, et al. Lower Preprandial Insulin and Altered Fuel Use in HIV/Antiretroviral-Exposed Infants in Cameroon. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(9):3260–3269. doi: 10.1210/JC.2015-2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filteau S. The HIV-exposed, uninfected African child. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(3):276–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. WHO Press; Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. CONSOLIDATED GUIDELINES on the use of ANTIRETROVIRAL DRUGS FOR TREATING AND PREVENTING HIV INFECTION. WHO Press; Geneva: Jun, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh AY, Saberi S, Ajaykumar A, Hukezalie K, Gadawski I, Sattha B, et al. Optimization of a Relative Telomere Length Assay by Monochromatic Multiplex Real-Time Quantitative PCR on the LightCycler 480: Sources of Variability and Quality Control Considerations. J Mol Diagn. 2016;18(3):425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rinaldo P, Cowan TM, Matern D. Acylcarnitine profile analysis. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2008;10(2):151–156. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181614289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saberi SVF, Ziada A, Hsieh A, Gadawski I, Côté HC for the CIHR Team in Cellular Aging and HIV Comorbidities in Women and Children (CARMA) Physiological concentrations of combination antiretroviral therapy drugs affect mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) quantity and quality in cell culture models. 8th International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Vancouver, BC. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konig H, Behr E, Lower J, Kurth R. Azidothymidine triphosphate is an inhibitor of both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase gamma. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33(12):2109–2114. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.12.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen BH, Chinnery PF, Copeland WC. POLG-Related Disorders. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R) Seattle (WA): 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sim KG, Carpenter K, Hammond J, Christodoulou J, Wilcken B. Acylcarnitine profiles in fibroblasts from patients with respiratory chain defects can resemble those from patients with mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation disorders. Metabolism. 2002;51(3):366–371. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.30521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Mohsen AW, Mihalik SJ, Goetzman ES, Vockley J. Evidence for physical association of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation complexes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(39):29834–29841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.