Abstract

Background

Short message service (SMS) surveys are a promising tool for understanding whether pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence aligns with risk for HIV acquisition— a concept known as prevention-effective adherence.

Methods

The Partners Demonstration Project was an open-label study of integrated PrEP and antiretroviral therapy (ART) delivery among high-risk HIV serodiscordant couples in East Africa. HIV-uninfected partners were offered PrEP until their HIV-infected partner had taken ART for ≥6 months. At 2 study sites, HIV-uninfected partners were offered enrollment into the Partners Mobile Adherence to PrEP (PMAP) sub-study based on ongoing PrEP use, personal cell phone ownership, and ability to use SMS. SMS surveys asked about PrEP adherence and sexual activity in the prior 24 hours; these surveys were sent daily for the 7 days prior and 7 days after routine study visits in the Partners Demonstration Project.

Results

The PMAP sub-study enrolled 373 HIV-uninfected partners; 69% were male and mean age was 31 years. Participants completed 17,030 of 23,056 SMS surveys sent (74%) with a mean of 47 surveys per participant over 9.8 months of follow-up. While HIV-infected partner use of ART was <6 months, mean reported PrEP adherence was 92% on surveys concurrently reporting sex within the serodiscordant partnership and 84% on surveys reporting no sex (p<0.001).

Discussion

SMS surveys provided daily assessment of concurrent PrEP adherence and sexual behavior. Higher PrEP adherence was temporally associated with increased risk for HIV acquisition.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), SMS, adherence

Introduction

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been shown to be very effective in preventing HIV acquisition when taken consistently(1–3). High adherence in the absence of HIV risk, however, may lead to unnecessary financial or emotional burden or rarely side effects for the PrEP user, as well as unnecessary expenditures for the healthcare system(4). These considerations have likely contributed to the slow roll-out of PrEP in many settings(5). PrEP adherence should therefore be aligned with periods of substantial HIV risk, with options for temporary or permanent discontinuation when risk is minimal— a concept known as prevention-effective adherence(4).

Traditional methods for understanding dynamic HIV acquisition risk behaviors and concurrent use of HIV prevention strategies are limited. Typically, these data are collected at infrequent intervals (e.g., quarterly study visits), which may be subject to recall bias(6). Moreover, social desirability bias may limit reporting accuracy on these sensitive topics, particularly when assessed face-to-face. Novel, real-time approaches are therefore needed to understand the context in which PrEP adherence is (or is not) occurring.

Approximately 5 billion people own mobile phones globally, making them a potentially valuable tool for self-reported data collection(7). Kenya, for example, had 33.6 million mobile phone subscribers in 2014 (reflecting 83% country penetration), with short message service (SMS) preferred to voice calls(8). SMS enables frequent, inexpensive surveys that could potentially overcome the recall and social desirability biases inherent in traditional data collection(9, 10). Moreover, preliminary work has shown SMS surveys to be feasible and acceptable for collection of antiretroviral adherence and sexual behavior data(11, 12).

In this paper, we describe the use of SMS surveys for determining prevention-effective adherence among HIV serodiscordant couples enrolled in a demonstration project of antiretroviral-based prevention in East Africa.

Methods

The Partners Demonstration Project

The Partners Demonstration Project was a prospective, open-label study of integrated ART and PrEP delivery for HIV prevention among high-risk heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda. Study procedures are detailed elsewhere(13). Briefly, eligible couples were ≥18 years old, sexually active, and intending to remain a couple for ≥1 year. HIV-uninfected partners were offered once daily oral PrEP (emtricitabine 200mg/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300mg) with use recommended until the partner living with HIV had been on ART for ≥6 months, permitting time to achieve viral suppression (a strategy called “PrEP as a bridge to ART”). The PrEP “bridge” period could be extended for couples in which the partner living with HIV delayed or declined ART or if the HIV-uninfected partner and/or clinician felt there was other rationale to continue. Study visits occurred at one month and quarterly for up to 24 months. Counseling messages were consistent with US Center for Disease Control guidance (14), including daily PrEP use (15).

The Partners Mobile Adherence to PrEP (PMAP) sub-study

The Partners Mobile Adherence to PrEP (PMAP) sub-study was designed to assess PrEP adherence and concurrent risk for HIV acquisition via SMS surveys and was implemented at 2 study sites (Thika and Kampala). HIV-negative partners were eligible if they had ≥3 months of planned PrEP use, owned a mobile phone using a service provider compatible with the SMS platform (i.e., Safaricom in Thika; MTN and Airtel in Kampala), were literate, able to receive and send SMS, and had regular access to electricity for charging their phone. Eligible participants completed a 1-week trial period of daily surveys and were enrolled if they completed ≥3 daily surveys; additional training was provided as needed.

Participants were sent daily SMS surveys for 7 days before and 7 days after each study visit in the Partners Demonstration Project (the “reporting window”). Surveys were sent at participant-selected times and were available for responses for 23 hours after delivery. Each survey was initiated only after receipt of a 4-digit password and consisted of 7 questions with branching logic on sexual activity and PrEP adherence in the prior 24 hours (Appendix). Depending on survey skip patterns, questions about general health behaviors (e.g., drinking boiled water) were used to ensure each survey consisted of 7 questions, thus discouraging responses leading to shorter surveys. Participants were incentivized with approximately $0.50 of airtime for each completed survey, which was automatically delivered to their phones. SMS surveys were sent while participants were eligible to take PrEP and held during protocol-defined holds (e.g., drug toxicity). During prolonged cellular network outages, additional SMS surveys were sent to affected participants so approximately 14 surveys were sent around each study visit.

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics and survey responses were summarized. Sexual activity and PrEP adherence were assessed at the level of the survey. Average adherence was calculated per participant using the number of days on which adherence was reported, divided by the number of days for which SMS survey data were available. Adherence was then stratified by days reporting or not reporting sex, and averaged over the study period. Data were limited to periods when PrEP was dispensed. ART use by partners living with HIV was obtained from Partners Demonstration Project records. HIV-uninfected partners were considered at risk for HIV if they had condomless sex within the serodiscordant partnership while the partner living with HIV had taken ART for <6 months. Wilcoxon rank sum and Chi-square tests were used for comparisons of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Comparisons were performed within each individual using a fixed effects model to control for time-invariant confounding. Differences were also assessed by biological sex and compared before and after study visits.

Ethics statement

All participants provided written informed consent. Institutional review board approval was obtained from Partners Healthcare/Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Washington, the Kenyan Medical Research Institute, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Results

PMAP participant characteristics

The Thika and Kampala sites contributed 332 and 292 participants, respectively, to the Partners Demonstration Project (total N=624). Twenty-seven participants were lost to follow-up and could not be approached for participation in PMAP. Of the 597 screened,, 6 declined, 68 were not planning ≥3 months of PrEP use at screening, and 150 were found ineligible for other reasons: 77 were illiterate/unable to read or send SMS; 49 lacked a functional, personal mobile phone on a compatible service provider, and 24 failed the SMS survey trial. Some individuals had multiple reasons for ineligibility. A total of 373 individuals enrolled in PMAP.

Sixty-nine percent of PMAP participants were male with a mean age of 31 (standard deviation [SD] 8) years and 10 (SD 3) years of education. Condomless sex was reported in the month prior to enrollment by 68%. Site differences in participant characteristics are shown in the Table.

Table.

Participant characteristics and SMS survey findings by study site. Data indicate number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

| Thika (N=193) |

Kampala (N=180) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | |||

| Male gender | 155 (80%) | 101 (56%) | <0.001 |

| Age (mean [SD] years completed) | 32 (8.5) | 31 (8.7) | 0.01 |

| Education (mean [SD] years completed) | 9.5 (3.4) | 8.1 (4.2) | 0.08 |

| Condomless sex reported in the month prior to enrollment | 119 (66%) | 133 (69%) | 0.56 |

| SMS survey findings | |||

| Surveys completed | 10,648 (82%) | 6,382 (63%) | <0.001 |

| Surveys reporting PrEP use in the prior 24 hours | 9,064 (85%) | 4,671 (73%) | <0.001 |

| Surveys reporting sex in the prior 24 hours | 3,870 (36%) | 1,672 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Of those reporting sex, surveys reporting condomless sex | 604 (16%) | 721 (43%) | <0.001 |

SMS surveys

A total of 23,056 SMS surveys were sent during the PMAP study, of which 17,030 (74%) were completed by 359 participants. A mean of 47 (SD 29) SMS surveys were completed per participant over a mean of 4.6 (SD 2.2) 14-day reporting windows, reflecting a mean of 9.8 (SD 6.0) months of study participation. Differences in SMS surveys between the study sites are shown in the Table; participants in Thika completed more surveys and reported more PrEP use, more days with sex, and more condom use. Data on sex, condom use, and PrEP adherence were missing from 46, 67, and 93 surveys, respectively. Of note, mid-way through the study, a Ugandan national telecommunication policy aimed at limiting undesired bulk SMS(16) temporarily disrupted SMS delivery, resulting in ≥3 weeks of missed surveys for participants in the Kampala site and permanent termination for 13 participants who only had access to the service provider, Airtel.

Prevention-effective adherence

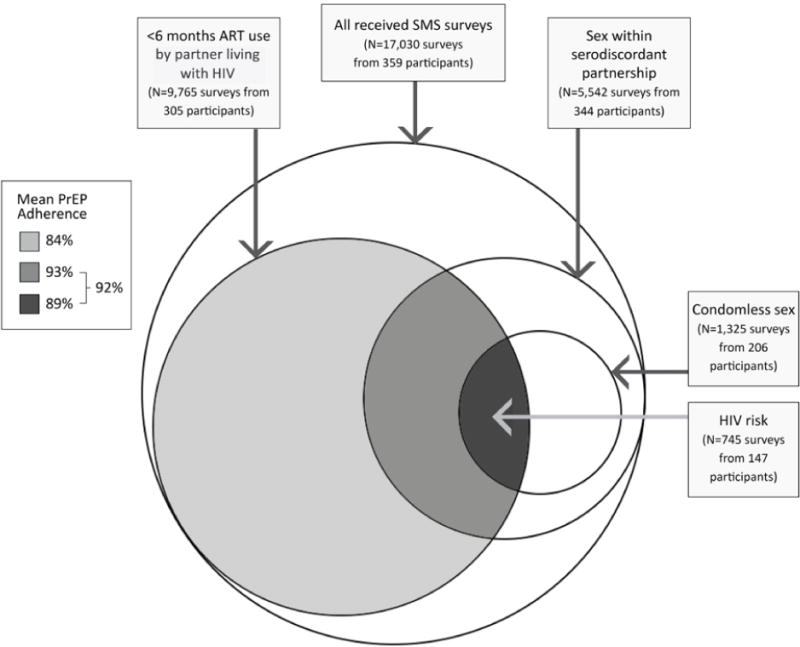

Overall mean adherence to PrEP without regard to other behaviors was reported as 80% (SD 25). As shown in the Figure, 305 participants completed 9,765 surveys while their partner living with HIV had taken ART for <6 months. Sex within the serodiscordant partnership in the prior 24 hours was reported by 344 participants on 5,542 surveys, and 206 participants reported lack of condom use on 1,325 of these surveys. Considered concurrently, condomless sex within the serodiscordant partnership while the partner living with HIV had used ART for <6 months (the definition of HIV risk in this analysis) was reported by 147 participants on 745 surveys (4% of all completed surveys). PrEP adherence was reported on 89% (SD 26) of these surveys indicating HIV risk (p<0.001 compared to 80% PrEP adherence among all other surveys). No differences were seen when comparing average or prevention-effective adherence before and after study visits, although condom use increased by 4% after the study visit (p=0.013). One PMAP participant was found to have HIV at Month 3; SMS-reported adherence was 67% around that visit.

Figure.

Mean PrEP adherence associated with risk for HIV transmission. Circles indicate risk behaviors for HIV acquisition: <6 months of ART use by the partner living with HIV, sex reported within the serodiscordant partnership, and reported condomless sex. Mean reported PrEP adherence concurrent with each overlap of behaviors is shown in the legend.

Differences in PrEP adherence by reported risk

While the partner living with HIV had taken ART for <6 months, mean PrEP adherence was higher on the 3,266 surveys reporting sex (regardless of condom use) versus the 6,453 surveys not reporting sex (92% versus 84%, p<0.001), although PrEP adherence when reporting sex was lower in the 709 surveys completed by females compared to the 2,464 surveys completed by males (87% versus 94%, p=0.019). Mean PrEP adherence was similar for the 2,454 surveys reporting condom use versus the 745 not reporting condom use (93% versus 89%, p=0.24).

Discussion

Periodic daily SMS surveys provided real-time assessment of concurrent PrEP adherence and sexual behavior in a demonstration project of antiretroviral-based prevention among HIV serodiscordant couples in East Africa. Data show that overall self-reported SMS adherence was high at 80%. Other adherence measures from the Partners Demonstration Project were similarly high: electronic monitoring indicated that PrEP was taken on 82% of expected days and tenofovir was detected in plasma in 85% of randomly-selected samples(13). Overall incidence of HIV infection was 0.2 per 100 person-years, further suggesting that participants adhered to PrEP and/or ART during periods of risk for HIV acquisition.

SMS data in this analysis also show that adherence was higher when reporting versus not reporting sex prior to 6 months of ART use by the partner living with HIV (92% versus 84%), although adherence with reported sex was somewhat lower in female compared to male participants (87% versus 94%). In the Partners PrEP study, plasma tenofovir concentrations were similarly detected more often in individuals reporting versus not reporting sex(17). This difference suggests that participants adjusted their use of PrEP based on sexual activity and perceived risk. Participants were counseled to take PrEP daily to achieve effective protection against HIV infection; however, they were also advised on risk of HIV acquisition and the protection that achievable through other tools (e.g., sexual abstinence, condoms). Individuals may have chosen to take PrEP based on perceived risk when considering these other factors.

This study presents risk data obtained daily; however, it is important to note that the need for PrEP should not be assessed day-to-day. Pharmacokinetic data suggest that individuals should take several daily doses upon PrEP initiation to achieve steady-state tenofovir levels in blood and longer in tissue compartments, ranging from a few days for men who have sex with men to 1–3 weeks in women(18, 19). Additionally, risk for HIV acquisition may be difficult to anticipate(20). Risk assessment over longer periods or “seasons” is more likely to be accurate and useful when assessing prevention-effective adherence(4). These findings highlight the importance of understanding PrEP adherence patterns and formulating counseling messages that help people regulate their own adherence in ways that provide maximal protection against HIV acquisition when needed, including choice among PrEP and other HIV prevention options.

SMS surveys were feasible for assessing PrEP use and concurrent HIV risk, although completion rates were lower in Kampala compared to Thika. The temporary disruption caused by national Ugandan telecommunications policy was partially contributory. Additionally, although not formally measured, power outages were more common in Kampala, potentially limiting the ability to charge phones. Given wide availability of mobile phones and relatively low cost of SMS, this tool should be considered for future studies and potentially clinical practice. Clinics, for example, could send weekly surveys to help PrEP users assess their risk and use of PrEP, as well as provide support if needed. This approach was used previously with ART delivery in Kenya(21) and showed improved ART adherence and viral suppression. Provision of real-time feedback on adherence is another potential use of this technology and appears favorable to PrEP users(22).

Our study has limitations. First, SMS reports may still be influenced by recall and/or social desirability bias, as seen previously(12). The adherence reported by the one PMAP participant who acquired HIV during the study was suboptimal (67%), but may still have been an overestimate. Differences in adherence and sexual behavior between biological sexes or study sites may thus reflect true differences in behavior and/or differences in reporting behavior. Second, while only 6 individuals declined study participation, 34% of surveys were not completed. It is unknown if these data were missing at random or reflected changes in behavior (e.g., not wanting to report non-adherence). Behavior may have also varied in between reporting windows or because of the timing of the study visit. We found no difference when comparing adherence before and after study visits, although condom use did increase slightly (4%). Third, this study did not assess all potential risk factors associated with HIV acquisition, such as outside partnerships and concurrent sexually transmitted infections. Fourth, the SMS may have served as reminders and increased adherence.

In conclusion, periodic daily SMS surveys provided concurrent, real-time reports of sexual behavior and PrEP adherence within HIV serodiscordant couples that indicate high levels of alignment for PrEP adherence and risk for HIV acquisition. These data and reports of high adherence for PrEP elsewhere(23, 24) are encouraging that PrEP adherence among individuals who desire it will be high enough to realize effective HIV prevention outside of clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the couples who participated in this study for their motivation and dedication and the referral partners, community advisory groups, institutions, and communities that supported this work. We also appreciate Katharine Hutchins for her assistance with preparing the manuscript.

Sources of support: The Partners Demonstration Project was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health (grant R01MH095507), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant OPP1056051), and through the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (cooperative agreement AID-OAA-A-12-00023). The PMAP sub-study was funded through the US National Institute of Mental Health (grant R01MH098744). Gilead Sciences donated the PrEP medication, but had no role in data collection or analysis. The results and interpretation presented here do not necessarily reflect the views of the study funders.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: Portions of this work were presented at the 9th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence, June 8–10, 2014, Miami, FL.

Declaration of Interests

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, Curran K, Koechlin F, Amico KR, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015;29:1277–1285. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugo NR, Ngure K, Kiragu M, Irungu E, Kilonzo N. The preexposure prophylaxis revolution; from clinical trials to programmatic implementation. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:80–86. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kagee A, Nel A. Assessing the association between self-report items for HIV pill adherence and biological measures. AIDS Care. 2012;24(11):1448–52. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GSMA. Mobile economy report. 2017 Available at: http://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 8.Kenya Communications Authority. Quarterly Sector Statistics Report: Second quater of the financial year 2014/2015. Available at: http://www.ca.go.ke/index.php/statistics. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 9.Adebajo S, Obianwu O, Eluwa G, Vu L, Oginni A, Tun W, et al. Comparison of audio computer assisted self-interview and face-to-face interview methods in eliciting HIV-related risks among men who have sex with men and men who inject drugs in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2014;9:e81981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson AM, Copas AJ, Erens B, Mandalia S, Fenton K, Korovessis C, et al. Effect of computer-assisted self-interviews on reporting of sexual HIV risk behaviours in a general population sample: a methodological experiment. AIDS. 2001;15:111–115. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101050-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curran K, Mugo NR, Kurth A, Ngure K, Heffron R, Donnell D, et al. Daily short message service surveys to measure sexual behavior and pre-exposure prophylaxis use among Kenyan men and women. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2977–2985. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0510-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haberer JE, Kiwanuka J, Nansera D, Muzoora C, Hunt PW, So J, et al. Realtime adherence monitoring of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults and children in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2013;27:2166–2168. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328363b53f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baeten JM, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, Mugo NR, Katabira E, Bukusi EA, et al. Integrated Delivery of Antiretroviral Treatment and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis to HIV-1-Serodiscordant Couples: A Prospective Implementation Study in Kenya and Uganda. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention and HIV infection in the United States: a clinical practice guideline. 2014 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 15.Morton JF, Celum C, Njoroge J, Nakyanzi A, Wakhungu I, Tindimwebwa E, et al. Counseling Framework for HIV-Serodiscordant Couples on the Integrated Use of Antiretroviral Therapy and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(Suppl 1):S15–S22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uganda Communications Commission. Stopping unwanted SMS. 2014 Dec 22; Available at: http://www.ucc.co.ug/data/dnews/46/Stopping-UNWANTED-SMS.html. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 17.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, Brantley J, Bangsberg DR, Haberer JE, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cottrell ML, Yang KH, Prince HM, Sykes C, White N, Malone S, et al. A Translational Pharmacology Approach to Predicting Outcomes of Preexposure Prophylaxis Against HIV in Men and Women Using Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate With or Without Emtricitabine. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:55–64. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrix CW, Andrade A, Bumpus NN, Kashuba AD, Marzinke MA, Moore A, et al. Dose Frequency Ranging Pharmacokinetic Study of Tenofovir-Emtricitabine After Directly Observed Dosing in Healthy Volunteers to Establish Adherence Benchmarks (HPTN 066) AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016;32:32–43. doi: 10.1089/aid.2015.0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corneli AL, McKenna K, Headley J, Ahmed K, Odhiambo J, Skhosana J, et al. A descriptive analysis of perceptions of HIV risk and worry about acquiring HIV among FEM-PrEP participants who seroconverted in Bondo, Kenya, and Pretoria, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(3 Suppl 2):19152. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Musara P, Etima J, Naidoo S, Laborde N, et al. Disclosure of pharmacokinetic drug results to understand nonadherence. AIDS. 2015;29:2161–2171. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Anderson PL, Doblecki-Lewis S, Bacon O, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection Integrated With Municipal- and Community-Based Sexual Health Services. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:75–84. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, Nguyen DP, Phengrasamy T, Silverberg MJ, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in a Large Integrated Health Care System: Adherence, Renal Safety, and Discontinuation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73:540–546. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.