Abstract

This study examined the effect of parenting on the association between childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and psychiatric resilience in adulthood in a large female twin sample (n=1423) assessed for severe CSA (i.e., attempted or completed intercourse before age 16). Severe CSA was associated with lower resilience to recent stressors in adulthood (defined as the difference between their internalizing symptoms and their predicted level of symptoms based on cumulative exposure to stressful life events). Subscales of the Parental Bonding Instrument were significantly associated with resilience. Specifically, parental warmth was associated with increased resilience while parental protectiveness was associated with decreased resilience. The interaction between severe CSA and parental authoritarianism was significant, such that individuals with CSA history and higher authoritarianism scores had lower resilience. Results suggest that CSA assessment remains important for therapeutic work in adulthood and that addressing parenting may be useful for interventions in children with a CSA history.

Keywords: childhood sexual abuse, parenting, resilience, parental authoritarianism

Introduction

Exposure to childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has been shown to have deleterious effects on physical and mental health outcomes in childhood [1, 2] and adulthood [3, 4]. Psychiatric outcomes associated with CSA include major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, bulimia, and substance dependence, among others [5–7]. There is support for a dose-response relationship with level of CSA severity and psychopathology risk, such that higher levels of CSA severity (e.g., attempted/completed intercourse vs. other types) are indicative of higher risk for psychiatric and substance use disorders [2, 5]. Results of large-scale meta-analyses and surveillance studies have found that the prevalence of CSA is approximately 20–25% for women [8–11]. The high prevalence of CSA exposure and insidious outcomes associated with CSA highlight the public health value for understanding potential risk and protective factors that are associated with mental health outcomes related to CSA. In particular, understanding the processes that influence resilience can help inform secondary prevention and treatment programs for exposed individuals.

Resilience is often defined as a dynamic process of successful adaptation to stressful experiences or adversity [12]. While resilience is often operationalized as the absence of psychopathology, operationalizing resilience as a continuous outcome may better capture the wide variation in adaptation following adverse events. Indeed, it has been suggested in the literature that resilience should be defined along a continuum, rather than as an arbitrary dichotomous outcome [12]. In line with this approach, our group has defined resilience in a quantitative manner, using a method that measures relative psychological resilience, as indicated by the residual of general internalizing symptoms of distress after the effect of identified risk factors (e.g., stressful life events) has been regressed out [13, 14]. These continuous residual scores result in a definition of resilience along a continuum, rather than as a potentially arbitrary dichotomy, which is believed to more accurately reflect the natural variation of responses to stressful life events. This approach to studying resilient outcomes represents the importance of understanding the detrimental effects of adverse events as well as characterizing the full range of individual differences in adaptation to adverse events and identifying factors that support this successful adaptation.

The early childhood environment, and parenting in particular, has been a central component of theories of psychosocial health. For the purpose of this study, we examine parenting in terms of parental warmth, rejection, control, and overprotection. Countless studies have found evidence that parenting behaviors characterized by hostility, rejection, and control are generally associated with negative psychiatric outcomes throughout the life course. For example, in a study of over 6,000 participants across two large birth cohort studies in the United Kingdom, parenting style, as measured by an adaptation of the Parental Bonding Instrument [PBI; 15], was significantly associated with adult mental health problems [16]. Specifically, using this two-scale version of the PBI, items associated with parental care and warmth (e.g., “are loving/caring/look after me”) were associated with decreased psychiatric symptoms, whereas items associated with overprotection (e.g., “are nagging/moaning/complaining”) were associated with increased psychiatric symptoms. Parental overprotection has also been associated with onset and occurrence of somatic symptoms in youth [17] and psychopathology in adults [18]. Low overprotection (i.e. autonomy) in mothers has been shown to mitigate the influence of maternal depression on adolescent resilience [19]. Additionally, although prior research indicates that parental authoritarianism may be associated with increased risk for multiple psychiatric and substance use disorders, these associations do not necessarily hold when the other two parenting dimensions, parental warmth and overprotection, are included, suggesting that parental authoritarianism itself may not have a unique relationship with risk of psychopathology [20–22].

Further evidence suggests that parenting factors may serve as protective factors, helping to mitigate the influence of CSA on the development of adult psychopathology. For example, studies have found that factors such as positive family environment [23] and parental care [24, 25] are associated with resilience to adult psychiatric diagnoses for those exposed to childhood maltreatment. When examining resilience to CSA, several large-scale studies found that parental warmth/care, as measured by the PBI, was associated with adult resilience (as defined by the absence of psychiatric disorders) among individuals exposed to CSA [24, 26].

Fewer studies have examined the effects of CSA, and potential protective factors, in relation to resilience in adulthood, particularly in a way that can capture the wide range of possible outcomes, and in a quantitative manner that incorporates the number of stressors experienced. Research suggests that child maltreatment, including CSA, is associated with reduced self-reported resilience to stressors in adulthood [27]. Although research suggests that much of the variance in resilience to adult stressors is due to genetic factors (31–50%), there remains a significant portion of variance attributable to environmental factors [13, 14]. Thus, identifying those environmental factors, such as parenting, that mitigate the influence that CSA has on adult resilience is important for understanding the stress adaptation process as well as informing secondary prevention efforts for those who experience CSA.

The present study sought to examine the influence of severe CSA exposure (defined as attempted or completed intercourse; see the Methods section) and parenting on psychiatric resilience in adulthood. Specifically, we hypothesized that 1) severe CSA would serve as an enduring risk factor for diminished resilience to recent stressful life events, and 2) positive parenting (i.e., high parental warmth, low protectiveness, and low authoritarianism) would be associated with higher levels of resilience to recent events. We also examined whether any of these parenting variables moderated the impact of severe CSA on resilience.

Methods

Sample

Participants were taken from the Virginia Adult Twin Studies of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders (VATSPSUD) study [28], ascertained from the birth certificate-based Virginia Twin Registry (this study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board). This dataset contains a detailed assessment of CSA, and thus has been used to analyze CSA and related outcomes in multiple prior papers [e.g., 5, 6, 29]. Caucasian female-female (FF) twin pairs, born 1934–1974, were eligible if both members responded to a mailed questionnaire in 1987–1988. Response rates across the four interview waves (FF1–FF4) ranged from 72–83%. Of the female twins who responded, only those who filled out the CSA portion of the questionnaire at FF4 were included in the subsequent analyses (n=1423 individual female twins, who were part of a monozygotic or dizygotic pair). The FF4 wave took place from 1995–1997 when twins were, on average, 35.1 years of age (SD = 7.5). Demographic covariates (age and income) from this wave were used as covariates in all regression models. Parenting variables were assessed at Wave 2 (FF2). Both twin pairs and singletons (i.e., individuals whose co-twin was not part of the study) were included in all analyses, and the data was treated as an epidemiologic sample (as done in prior analyses of CSA within this sample; [e.g., 5, 6, 29]), with statistical corrections made for twin structure to account for the correlated nature of the sample.

Measures

Demographic variables

Age and income level (at FF4) were used as covariates in all analyses. Income level was assessed using an ordinal scale comprised of 15 income ranges, beginning at ‘under $3,000’ and ending at ‘$200,000 and over.’

Parenting

A shortened version (16 items; 9 items dropped from the original 25-item scale) of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI, [15, 30, 31] was used to assess perception of both maternal and paternal parenting. Each item had 4 response options, rated on a 1 to 4 Likert scale, ranging from “a lot like” (1) to “not at all like” (4). Prior papers using this data have indicated that a three-factor solution is appropriate for these 16 items [e.g., 20, 32]. Thus, sum scores were created for both mother and father on three parenting dimensions (self-rated): Warmth (e.g., “was emotionally distant from me” [reverse coded] and “enjoyed talking things over with me”), Protectiveness (e.g., “ was overprotective of me” and “tended to baby me”), and Authoritarianism (e.g., “was consistent in enforcing rules” and “let me dress in any way I pleased” [reverse coded]). As our interest was in examining the influence of overall environment, and given previous findings with this dataset that parenting variables and risk for psychiatric disorders did not differ for mothers vs. fathers [20], sum scores were averaged across ratings of both parents to create the final variables. Within the full FF2 sample where the PBI was administered, mean Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.71 to 0.89 across maternal and paternal measures of parenting [20]. The sum scores represent greater amounts of each dimension (e.g., greater warmth, greater protectiveness [i.e., overprotectiveness], and greater authoritarianism).

Childhood sexual abuse

A self-report questionnaire included items that queried about childhood sexual abuse, including incident characteristics such as relationship to the perpetrator. Prior to CSA assessment, twins were asked how they would prefer to report on CSA items, and self-report was chosen over interview. The questionnaire included 6 items that assessed the occurrence and severity of CSA, in response to the following question: “Before the age of 16, did any adult, or another person older than yourself, involve you in any unwanted incidents like…” In the present study, response to one of these 6 items (attempting or having sexual intercourse) was used to create a binary CSA variable, where a response of “once” or “more than once” to this item was coded as a 1 (indicated attempted or completed sexual intercourse) and “never” was coded as 0 (did not indicate experiencing attempted or completed intercourse). Prior studies of CSA and psychopathology within this sample have examined a less strict version of CSA, and have also explored across different severity levels [5, 6]. We chose to include the most stringent definition of CSA (attempted or completed intercourse) within our analyses, as CSA severity has been shown to have a dose-response relationship with psychiatric disorders, with the highest category (i.e., intercourse) resulting in the highest risk [5]. Throughout the paper, we will refer to this as “severe CSA.” Within the incident characteristics, participants were asked to indicate their “relationship to the person, or persons, involved in all such incidents” and using these responses, a binary variable was created to reflect the endorsement of a relative as the perpetrator for use in follow-up analyses.

Resilience

Participants completed a shortened version of the Symptom Checklist-90 [33], which utilized a past month timeframe (at FF4). There were 27 items from four of the SCL subscales: depression (10 items), somatization (5 items), anxiety (7 items), phobic anxiety (5 items), and 3 items that assessed sleep difficulty. This measure demonstrated relatively high internal reliability (Cronbach’s α= 0.91). Participants were also assessed for exposure to stressful life events (SLEs) during personal interview at FF4. Events queried included those that were personal in nature (assault, serious marital problems, divorce, job loss, loss of a confidant, serious illness, major financial problem, being robbed, serious legal problems), and “network” events (i.e., events that occurred primarily to, or in interaction with, an individual in the respondent’s social network such as death or severe illness of the respondent’s spouse, child, parent, co-twin, or other relative, serious trouble getting along with others close to the respondent). Inter-rater reliability for determining the occurrence of the events was high (kappa = 0.93) [34]. A count of the total number of SLEs (out of 15 types total) over the past 90 days (at FF4) was computed and used in creating the resilience variable, below.

Resilience was operationalized as the residual of the SCL score after the effect of recent number of SLEs has been regressed out (i.e., the difference between actual and predicted SCL), resulting in a continuous measure of resilience. If an individual’s SCL was lower than predicted by the regression this would result in a negative residual, reflecting resilience; if an individual’s SCL was higher than expected, this would result in a positive residual, reflecting low levels of resilience. For clarity in interpretation of subsequent analyses, the resilience variable was then multiplied by −1 so that a positive score indicates higher resilience and a negative score indicates lower resilience.

Stressful life events

SLEs were also assessed at FF3, in the same way as described for FF4, above. Past year SLE count was computed at FF3 and used in follow-up regression analyses.

Data Analytic Plan

Linear regressions were conducted in SAS 9.4 [35]. To account for the non-independence of the nested twin structure, we used the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) command of the SAS PROC GENMOD procedure. Parenting variables were mean centered to facilitate use in interaction analyses. Three hierarchical models were run to examine the effects of CSA, parenting, and their potential interactions on resilience at FF4. Model 1 assessed the effects of CSA (with age and income at FF4 as covariates) on resilience in order to examine this relationship without parenting variables. In Model 2, the three parenting variables (warmth, protectiveness, and authoritarianism) were added to examine their main effects on resilience above and beyond that of CSA. Finally, to examine potential interactions between CSA and parenting on resilience, Model 3 included multiplicative CSA and parenting interaction terms (CSA by parental warmth, CSA by parental protectiveness, CSA by parental authoritarianism) to test for moderation. For each regression, individual beta coefficients, p values, and the adjusted R2 of the model are reported. We also conducted several follow-up regressions, which included the addition of SLEs as a covariate in the models described above, as well as the use of the relationship to perpetrator variable to predict resilience for individuals endorsing severe CSA.

Results

Sample Characteristics

1423 individuals with available CSA data were included in analysis. The prevalence of severe CSA in this sample was 8.6% (N=123). Descriptive information for key variables, for the full sample and by group status, is shown in Table 1. There were no meaningful differences between individuals who endorsed severe CSA and those who did not on age, income, or parental protectiveness. However, individuals endorsing severe CSA had lower scores on parental warmth and resilience and higher scores on parental authoritarianism and stressful life events, than those without a severe CSA history. Pearson correlations are presented in Table 2, and the pattern of correlations was in the expected direction. The only exception was protectiveness and severe CSA, which were not significantly correlated.

Table 1.

Key variables by severe CSA status

| Total sample | CSA + | CSA − | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | df | t value | Pr > |t| | |

| 1. Age (at FF4) | 36.40 | 8.43 | 37.64 | 8.47 | 36.29 | 8.42 | 1419 | −1.69 | 0.091 |

|

| |||||||||

| 2. Income (at FF4)1 | 9.18 | 2.37 | 8.68 | 2.33 | 9.23 | 2.67 | 138* | 2.18 | 0.031 |

|

| |||||||||

| 3. Parental warmth | 23.05 | 4.19 | 21.11 | 4.86 | 23.23 | 4.08 | 118* | 4.34 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||||||

| 4. Parental protectiveness | 9.97 | 3.33 | 10.46 | 3.25 | 9.93 | 3.33 | 1222 | −1.55 | 0.12 |

|

| |||||||||

| 5. Parental authoritarianism | 8.49 | 2.54 | 9.26 | 2.60 | 8.42 | 2.52 | 1222 | −3.24 | 0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| 6. Total SLEs (past 12 mo.; at FF3)2 | 1.48 | 1.49 | 2.19 | 1.87 | 1.41 | 1.43 | 119* | −4.19 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||||||

| 7. Resilience (at FF4) | −0.003 | 0.98 | −0.50 | 1.15 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 136* | 5.02 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: SLEs = Stressful life events.

Note that income levels correspond as follows: 8 = $27,000–$35,000; 9 = $35,000–$45,000

Note that the highest SLE categories had the lowest endorsement and were collapsed into a revised SLE variable (Range = 0–6), presented here.

Variances were not equal across groups so the Satterthwaite method was used.

Table 2.

Correlations between key variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (at FF4) | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2. Income (at FF4) | 0.25** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3. Severe childhood sexual abuse | 0.05 | −0.07* | 1.00 | |||||

| 4. Parental warmth | −0.19** | 0.01 | −0.14** | 1.00 | ||||

| 5. Parental protectiveness | −0.02 | −0.08** | 0.04 | −0.14** | 1.00 | |||

| 6. Parental authoritarianism | 0.18** | −0.02 | 0.09** | −0.40** | 0.48** | 1.00 | ||

| 7. Total SLEs (past 12 mo.; at FF3) | 0.00 | −0.12** | 0.15** | −0.15** | 0.08** | 0.10** | 1.00 | |

| 8. Resilience (at FF4) | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.16** | 0.17** | −0.14** | −0.12** | −0.15** | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: SLEs = Stressful life events.

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01.

Shown are Pearson correlations between all variables.

Linear regression models

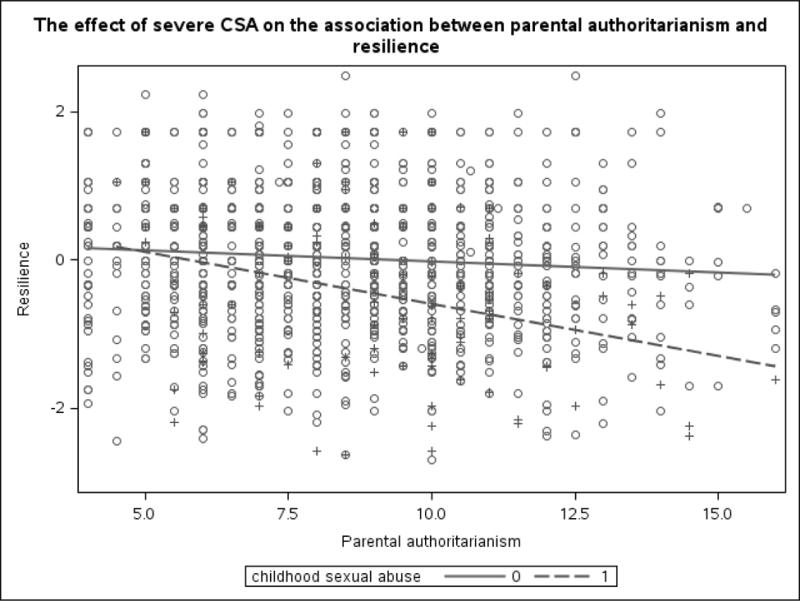

Table 3 shows results for the three regression models. Note that some variables of interest predicted higher levels of resilience, while others predicted lower levels of resilience. In Model 1, which examined the effects of severe CSA on resilience, severe CSA was a significant predictor of lower resilience at FF4 (β = −0.504, p < 0.0001). Age (β = −0.007, p = 0.034; older age predicting lower resilience), but not income, was a significant covariate. Model 1 explained approximately 2% (Adjusted R2 = 0.024) of the variance in resilience. When parenting variables were included in Model 2, severe CSA continued to significantly predict lower resilience (β = − 0.419, p = 0.0002). Similarly, parental protectiveness (β = −0.030, p = 0.001) significantly predicted lower resilience, while parental warmth (β = 0.030, p < 0.0001) was significantly associated with higher resilience in this model. There were no significant effects of parental authoritarianism or either covariate (age, income) on resilience. Model 2 explained 5% (Adjusted R2 = .049) of the variance in resilience. In Model 3, which included interaction terms to test for moderation, severe CSA (β = −0.357, p = 0.003) and parental protectiveness (β = −0.031, p = 0.002) remained significantly associated with lower resilience, and parental warmth (β = 0.034, p < 0.0001) maintained its association with higher resilience. There was also a significant interaction between severe CSA and parental authoritarianism (see Figure 1; β = −0.129, p = 0.005), such that for individuals exposed to severe CSA, higher scores on parental authoritarianism predicted lower resilience. There were no significant interactions between severe CSA and the other parenting subscales, and once again, no other covariates were significant. This final model explained approximately 6% (Adjusted R2 = .057) of the variance in resilience.

Table 3.

Coefficients from linear regression models predicting resilience

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | −0.007* | −0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2. Income | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| 3. Severe childhood sexual abuse (CSA) | −0.504*** | −0.419*** | −0.357** |

| 4. Parental protectiveness | – | −0.030** | −0.031** |

| 5. Parental warmth | – | 0.030*** | 0.034*** |

| 6. Parental authoritarianism | – | 0.000 | 0.014 |

| 8. CSA × parental warmth | – | – | −0.017 |

| 9. CSA × parental protectiveness | – | – | −0.019 |

| 10. CSA × parental authoritarianism | – | – | −0.129** |

|

| |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.024 | 0.049 | 0.057 |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Note that all parental variables have been mean centered to facilitate interpretation of the interactions.

Figure 1.

The effect of severe childhood sexual abuse on the association between parental authoritarianism and past-year psychiatric resilience. Scores on the PBI authoritarianism scale are shown on the x-axis, while the y-axis represents the residual score for resilience to recent stressors. + indicates exposure to severe CSA; o indicates non-exposure.

Follow-up Analyses

We also re-ran the hierarchical models using past year SLEs from FF3 as an additional demographic covariate (included in the initial and subsequent models). SLEs were significantly correlated with all variables except for age (see Table 2) and were a significant covariate in all models (coefficients ranging from −0.079 to – 0.063, all p values < 0.001). Overall results did not differ upon the inclusion of SLEs, but the effect of severe CSA on resilience in the final model did decrease (from −0.357 [original] to −0.296) and the amount of variance explained by this final model was slightly larger (adjusted R2 = 0.064). Further, given the interaction between severe CSA and parental authoritarianism, we also conducted a follow-up analysis on individuals endorsing severe CSA in order to rule out the potential confounding effects that could occur if a parent was the perpetrator of the abuse. Using additional self-report information on relationship to the perpetrator (used as a proxy variable for parent), we conducted regressions examining the main effects of both relationship to the perpetrator and parental authoritarianism, as well as their interaction, on resilience. In the final model with all covariates, parental authoritarianism was a significant predictor of resilience in individuals endorsing severe CSA (β = −0.132, p = 0.002), but neither having a relative as the perpetrator, nor the interaction with authoritarianism, was significant.

Discussion

The aims of the present study were to examine the long-term impact of severe CSA, three parenting dimensions, and their interactions, on adult resilience. Results suggested an enduring effect of severe CSA on level of adult resilience, such that a history of severe CSA was related to lower resilience, despite an average of 27 years passing since the abuse. This extends the limited literature with regard to resilience as a construct, or response, in the context of a history of CSA. This work aligns with the findings of Campbell-Sills and colleagues [27] that examined childhood trauma in relation to self-reported resilience in adulthood, and expands it to include an alternative and unique conceptualization of resilience, how one responds to SLEs experienced in adulthood. Further, findings are also consistent with a larger body of existing literature on the long-term association of CSA with a wide range of negative mental health outcomes [6, 36, 37] which appears to be particularly strong with sexual abuse [vs. physical abuse; 38]) and when controlling for other childhood adversities [39].

The present findings also suggest that parental warmth, protectiveness, and authoritarianism are associated with enduring effects on resilience in adulthood. Parental warmth was independently associated with greater psychiatric resilience, while protectiveness, perhaps better conceptualized as overprotectiveness, was associated with decreased resilience. These results align with extant studies demonstrating that poor relationship quality with parents in general [16] and parental warmth and overprotection in particular [18, 40, 41] predict mental health problems in adulthood. The finding of a non-significant main effect for authoritarianism when the other parenting dimensions are included in the model is consistent with other analyses of psychiatric outcomes using this dataset, indicating that results remain consistent when utilizing resilience as an outcome instead [20, 21].

When examining the potential moderating effect of parenting on the relationship between severe CSA and resilience, a significant interaction was observed with authoritarianism. Specifically, individuals with a history of severe CSA and higher reported parental authoritarianism had significantly lower resilience. Our finding of a significant interaction in the absence of a main effect is consistent with prior research on parenting dimensions finding moderation effects without main effects in relation to adult psychopathology [42]. Differences in authoritarian parenting have shown significant relationships with adult psychopathology, although directions have differed with respect to specific diagnostic outcomes [22]. Additionally, there is some evidence that authoritarian parenting exerts differing effects depending upon other environmental and psychosocial factors. For instance, authoritarian parenting appears to be particularly associated with poorer subjective wellbeing in early adulthood when it occurred in the context of emotional abuse [43], while it appears to be protective for children who exhibit behavioral inhibition [44]. There also exists a body of literature that has suggested that it is not the authoritarian parenting and punishment itself that is most impactful, but instead, is the youth’s perception of parental acceptance [45]. Thus, with regard to the present study findings, severe CSA history is perhaps indicative of other environmental or familial problems or has resulted in child reactions that are more likely to translate into poor responses to authoritarian parenting, all of which should be assessed in order to inform childhood interventions in this population. Further research is also needed to identify key mechanisms (e.g., child temperament, attachment style, family structure) underlying the association between parenting, CSA, and resilience. Research has found evidence for bidirectional/transactional influences between child temperament, parenting, and adjustment [46, 47], and research applying these frameworks to the study of the effects of CSA on resiliency may further our understanding of these complex developmental pathways.

Follow-up analyses in individuals endorsing severe CSA showed that parental authoritarianism, but not relationship to the perpetrator, was a significant predictor of adult resilience. This helps to rule out potential confounding effects in the event that a parent was the perpetrator and suggests that growing up in an environment characterized by greater parental authoritarianism may be particularly detrimental for children with a history of severe CSA. As demonstrated by the present findings, in combination with the likely importance of other environmental and psychosocial factors, there is a need for additional empirical work to determine the nuances of the relationship between CSA, parenting, and resilience.

Despite significant associations, the effects of both severe CSA and parenting on adult resilience were relatively small, which align with existing literature [3, 18] and do seem to be intuitive given the wealth of lifetime experience that occurred between severe CSA and current experiences transpiring decades after the abuse. This emphasizes the importance of further research into the cumulative impact of a range of developmental, family, and environmental moderators (e.g., relationship status and quality [48, 49]) that may each have a small, although not insignificant, effect on later mental health problems.

There are a number of limitations to note in the present study. First, all measures were self-report in nature and the retrospective nature of the CSA and parenting items presents the potential for bias. In this study, we conceptualized resilience as the residuals left after regressing stressful life events onto ratings of internalizing symptoms, viewing resilience as “better than expected” outcomes. This represents just one approach to operationalize the complicated and multifaceted construct of resilience, and while it carries the strength of being data-based and capturing a spectrum of responding, it does not capture the process of resilient responding, nor does it capture aspects of functioning or environmental variables that may be related to resilience (e.g., social support, treatment), which may be important. The average number of stressful life events reported by this sample was quite small. Thus, it remains to be determined whether these findings would hold in the context of greater self-reported stressors. The sample characteristics (all female, primarily Caucasian) limit the generalizability of results to other populations, and thus replication in diverse samples is needed. Finally, although the study was longitudinal in nature, which represents a strength, the findings cannot speak to causality or the potential for bidirectional effects.

In conclusion, the present study adds to the literature demonstrating the enduring effects of severe CSA on adult mental health outcomes. CSA history is also independently associated with increased contact with mental health services [36], which suggests that even though it is distal to the current concerns that individuals present with in therapy, assessment of CSA history is useful to consider in the therapeutic context. Indeed, specific interventions tailored to adults suffering from the long-term negative effects of CSA are important, and existing individual and group-based treatment approaches for this population have been shown to be beneficial [e.g., 50, 51]. The impact of parenting independently and in combination with severe CSA history also strongly suggests its importance for interventions in childhood. Family environment is important with regard to maladjustment following CSA [3] and given that parenting interventions are essential for improving problematic parent-child relationships [16], such interventions may be even more crucial for a CSA population. Moreover, the increasing focus on resilience and even posttraumatic growth in survivors following CSA [52] will provide useful insight into factors that promote resilience such as coping skills and positive, supportive parental relationships [for a review, see 53]. Further empirical work on resilience following CSA is warranted and will inform upon both prevention of negative long-term outcomes and on intervention strategies. A focus on factors such as event characteristics (e.g., age of perpetrator, age at abuse, frequency of abuse, etc.) is needed, given limited information in this domain to date as well as on sex differences, given mixed findings with regard to effects of CSA by gender [53] and evidence of differential impact of parenting, particularly authoritarianism, by gender [22, 41].

Summary

We investigated how parenting influences the relationship between severe CSA (attempted or completed intercourse) and psychiatric resilience in adulthood using a large sample of female twins. Although it still relies on self-reporting, a strength of our metric of resilience, which statistically quantifies resilient responding, is that it does not rely on individuals to accurately report on a higher level of observation (e.g., how resilient they think they are, their perceived ability to cope), which is more prone to reporting bias and errors in self-perception [14]. Severe CSA significantly predicted lower resilience, and remained significant when parenting dimensions (warmth, protectiveness, and authoritarianism) were included in the model. Higher parental warmth and higher parental protectiveness were both associated with resilience, but in opposite directions (higher resilience for warmth but lower resilience for protectiveness). When potential interactions between parenting scores and severe CSA were added in the final model, the only significant interaction was between parental authoritarianism and CSA: women with a history of severe CSA and higher scores on parental authoritarianism reported lower resilience. These results indicate that it remains important to assess CSA history in adults. Further, for children who have experienced CSA, interventions that target parenting approaches and behaviors may be beneficial. Future work should continue to identify factors in childhood, and post-CSA, which promote resilience throughout development and into adulthood.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Lind and Dr. Sheerin are supported by T32 MH020030. The Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry is supported by NIH grant UL1RR031990. Dr. York is supported by R01 AG037986. Dr. Amstadter’s time is partially funded by K02 AA023239.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: II. Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1365–1374. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maniglio R. The impact of child sexual abuse on health: a systematic review of reviews. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:647–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wegman HL, Stetler C. A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:805–812. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendler KS, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulik CM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Features of childhood sexual abuse and the development of psychiatric and substance use disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:444–449. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergusson DM, Mullen PE. Childhood sexual abuse: an evidence based perspective. Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gomez-Benito J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16:79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorey KM, Leslie DR. The prevalence of child sexual abuse: integrative review adjustment for potential response and measurement biases. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of Indivdual Adverse Childhood Experiences. Violence Prevention 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amstadter AB, Myers JM, Kendler KS. Psychiatric resilience: longitudinal twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:275–280. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.130906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amstadter AB, Maes HH, Sheerin CM, Myers JM, Kendler KS. The relationship between genetic and environmental influences on resilience and on common internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:669–678. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1163-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A Parental Bonding Instrument. Br J Med Psychol. 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan Z, Brugha T, Fryers T, Stewart-Brown S. The effects of parent-child relationships on later life mental health status in two national birth cohorts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1707–1715. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssens KA, Oldehinkel AJ, Rosmalen JG. Parental overprotection predicts the development of functional somatic symptoms in young adolescents. J Pediatr. 2009;154:918–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overbeek G, ten Have M, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R. Parental lack of care and overprotection. Longitudinal associations with DSM-III-R disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brennan PA, Le Brocque R, Hammen C. Maternal depression, parent-child relationships, and resilient outcomes in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1469–1477. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Parenting and adult mood, anxiety and substance use disorders in female twins: an epidemiological, multi-informant, retrospective study. Psychol Med. 2000;30:281–294. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otowa T, Gardner CO, Kendler KS, Hettema JM. Parenting and risk for mood, anxiety and substance use disorders: a study in population-based male twins. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1841–1849. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0656-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long EC, Aggen SH, Gardner C, Kendler KS. Differential parenting and risk for psychopathology: a monozygotic twin difference approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:1569–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1065-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Polo-Tomas M, Taylor A. Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: A cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:231–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collishaw S, et al. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:211–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bick J, Zajac K, Ralston ME, Smith D. Convergence and divergence in reports of maternal support following childhood sexual abuse: Prevalence and associations with youth psychosocial adjustment. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM. Factors protecting against the development of adjustment difficulties in young adults exposed to childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:1177–1190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell-Sills L, Forde DR, Stein MB. Demographic and childhood environmental predictors of resilience in a community sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Genes, environment, and psychopathology: understanding the causes of pyschiatric and substance use disorders. Guilford Press; New York, New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lind MJ, Aggen SH, Kendler KS, York TP, Amstadter AB. An epidemiologic study of childhood sexual abuse and adult sleep disturbances. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8:198–205. doi: 10.1037/tra0000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker G. The Parental Bonding Instrument: psychometric properties reviewed. Psychiatr Dev. 1989;7:317–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker G. The Parental Bonding Instrument. A decade of research. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990;25:281–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00782881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendler KS. Parenting: a genetic-epidemiologic perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:11–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale–preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kendler KS, et al. Stressful life events, genetic liability, and onset of an episode of major depression in women. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:833–842. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.SAS Institute Inc. Base SAS® 9.4 Procedures Guide: Statistical Procedures. Second. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cutajar MC, et al. Psychopathology in a large cohort of sexually abused children followed up to 43 years. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:813–822. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:721–732. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.6.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li M, D’Arcy C, Meng X. Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychol Med. 2016;46:717–730. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibarra P, et al. The BDNF-Val66Met polymorphism modulates parental rearing effects on adult psychiatric symptoms: a community twin-based study. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oldehinkel AJ, Veenstra R, Ormel J, de Winter AF, Verhulst FC. Temperament, parenting, and depressive symptoms in a population sample of preadolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:684–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caron A, Weiss B, Harris V, Catron T. Parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology: specificity, task dependency, and interactive relations. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35:34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brodski SK, Hutz CS. The Repercussions of Emotional Abuse and Parenting Styles on Self-Esteem, Subjective Well-Being: A Retrospective Study with University Students in Brazil. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2012;21:256–276. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams LR, et al. Impact of behavioral inhibition and parenting style on internalizing and externalizing problems from early childhood through adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:1063–1075. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9331-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erkman F, Rohner RP. Youths’ perceptions of corporal punishment, parental acceptance, and psychological adjustment in a Turkish metropolis. Cross-Cultural Research. 2006;40:250–267. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, Zalewski M. Nature and nurturing: parenting in the context of child temperament. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14:251–301. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sameroff AJ. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Overbeek G, Stattin H, Vermulst A, Ha T, Engels RC. Parent-child relationships, partner relationships, and emotional adjustment: a birth-to-maturity prospective study. Dev Psychol. 2007;43:429–437. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaillancourt-Morel MP, et al. Adult Sexual Outcomes of Child Sexual Abuse Vary According to Relationship Status. J Marital Fam Ther. 2016;42:341–356. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McDonagh A, et al. Randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:515–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessler MRH, White MB, Nelson BS. Group treatments for women sexually abused as children: a review of the literature and recommendations for future outcome research. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1045–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaye-Tzadok A, Davidson-Arad B. Posttraumatic growth among women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: Its relation to cognitive strategies, posttraumatic symptoms, and resilience. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8:550–558. doi: 10.1037/tra0000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marriott C, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Harrop C. Factors Promoting Resilience Following Childhood Sexual Abuse: A Structured, Narrative Review of the Literature. Child Abuse Review. 2014;23:17–34. [Google Scholar]