Abstract

We report two primary renal sarcomas demonstrating BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusions that have recently been identified in undifferentiated round cell sarcomas of bone and soft tissue. These neoplasms occurred in male children aged 11 and 12, and both were cystic as a result of entrapment and dilatation of native renal tubules. Both cases were composed of variably cellular bland spindle cells with fine chromatin set in myxoid stroma and separated by a branching capillary vasculature. Both neoplasms demonstrated immunoreactivity for BCOR, cyclin D1, TLE1 and SATB2 in the spindle neoplastic cells and negativity in the prominent capillary vasculature. One case was extensively cystic and had hypocellular areas that simulated cystic nephroma; this neoplasm recurred 3 years later as a solid, highly cellular spindle cell sarcoma in the abdominal cavity. The morphology and immunoprofile of these renal neoplasms was compared to a control group of other sarcomas with BCOR genetic abnormalities, including clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK), infantile undifferentiated round cell sarcomas of soft tissue/primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy (URCS/PMMTI), and bone/soft tissue sarcomas with BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion; along with primary renal synovial sarcoma. Our findings show that the renal sarcomas with BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion overlap with CCSK. They are in keeping with a “BCOR-alteration family” of renal and extra-renal neoplasms which includes CCSK and URCS/PMMTI (which typically harbor BCOR internal tandem duplication), and BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas, all of which are primarily driven by BCOR overexpression and have overlapping (but not identical) clinicopathologic features.

Keywords: Renal Neoplasm, Clear cell sarcoma: BCOR, Translocation

Introduction

Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK) comprises approximately 3% of pediatric renal neoplasms, and occurs at a mean patient age of 3 years1, 2. The classic morphologic pattern of CCSK is that of nests or cords of neoplastic cells separated by regularly spaced, arborizing fibrovascular septa. The cord cells can be either round, epithelioid or spindled, and are separated by extracellular mucopolysaccharide that creates a resemblance to clear cytoplasm. The nuclei are round to ovoid with fine chromatin without prominent nucleoli. The septal cells are spindled, fibroblast-like cells that surround thin, regularly-branching capillaries, and quite often form cellular perivascular sheaths (“cellular septa”). CCSK may also display a variety of variant morphologic patterns that mimic other neoplasms, including myxoid, sclerosing, cellular, spindled, storiform, palisaded, trabecular, and epithelioid patterns. While cyclin D13, 4 and SATB25 are often immunoreactive in CCSK, most other immunohistochemical markers such as CD34, S100, desmin, CD99, and cytokeratin are negative.

As implied by its name, CCSK has long been thought to be a kidney-specific sarcoma, with only rare putative extrarenal CCSK-like neoplasms reported1. Long a mystery, genetic alterations underlying CCSK have been delineated in the past decade. The majority (>90%) of CCSK harbor internal tandem duplications (ITD) in the last exon of the BCOR (Bcl6 interacting co-repressor) gene, which in CCSK is thought to regulate gene transcription through an epigenetic silencing mechanism6,7,8. A smaller subset of CCSK harbor a YWHAE-NUTM2B gene fusion resulting from a t(10;17)(q22.3;p13.3) translocation which is identical to that seen in high grade endometrial stromal sarcoma9,10. These two genetic alterations in CCSK appear to be mutually exclusive11, 12. A small subset of otherwise typical CCSK (<10%) lack either alteration11.

In the past five years, upregulation of BCOR by similar mechanisms as found in CCSK has been identified as an underlying genetic alteration in several soft tissue sarcomas of young patients. First, BCOR ITD and the YWHAE-NUTM2B/E gene fusion have been identified in undifferentiated round cell sarcoma (URCS) and primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy (PMMTI), two neoplasms that typically affect children under the age of 1 year5, 13, 14. On careful morphologic review, the latter two neoplasms overlap significantly morphologically with CCSK14. Second, a BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion resulting from an X chromosomal pericentric inversion has been identified in previously unclassified soft tissue and bone sarcomas which typically affect teenagers and young adults with a male predominance15–18. While the majority of these BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas were identified among EWSR1-negative Ewing-sarcomas and thought to be primarily small round neoplasms15, 16, more recently cases with spindled morphology have been described17, 18. Importantly, high levels BCOR mRNA expression resulting in BCOR protein overexpression as detected by immunohistochemistry5 and a distinctive BCOR-driven transcriptional profile14 have been identified in URCS/PMMTI, BCOR-CCNB3 fusion-positive sarcomas, and CCSK, suggesting that all of these neoplasms are highly genetically related. However, the existence of BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas originating in the kidney as well as a relationship between bone/soft tissue sarcomas with the BCOR-CCNB3 fusion and CCSK has not previously been described.

In this report, we describe two primary renal sarcomas harboring BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusions. We review the morphology and perform a broad immunochemical analysis of these neoplasms, and compare them to control groups of typical CCSK, BCOR-CCNB3–positive bone/soft tissue sarcoma, and BCOR-ITD positive URCS/PMMTI. Review of the morphology and immunohistochemical profile of BCOR-CCNB3 –positive renal and bone/soft tissue sarcomas demonstrates overlap with CCSK. Finally, given prior work demonstrating upregulation of BCOR identified in approximately 50% of soft tissue synovial sarcomas, we examine the expression of BCOR and related markers in primary renal synovial sarcoma19, which represents the main differential diagnosis of the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas.

Methods

Cases

Both renal sarcomas with BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion were identified in a review of renal sarcomas in our files with overlapping features of CCSK and renal synovial sarcoma. Both of these neoplasms had been considered unclassified at the time of diagnosis. All of the cases in the review cohort were screened by immunohistochemistry by BCOR, and positively-labeling cases were analyzed for the presence of BCOR and CCNB3 fusion/inversion by FISH. Break-apart FISH was also performed with custom BAC probes for the following genes: SS18, SSX1, SSX2, SS18L1 (all for synovial sarcoma), or YWHAE (for CCSK) using previously described methodology20. BCOR and CCNB3 FISH probes utilized are listed in Supplementary Table 1. SSX1, SSX2, SS18 and SS18L1 probes utilized have been described previously20.

Review of a control group of BCOR-associated soft tissue sarcomas

Following identification of renal sarcomas with BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusions, we reviewed the morphologic and immunohistochemical features of a cohort of 20 undifferentiated round cell sarcomas/primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumors of infancy (URCS/PMMTI) (all showing BCOR internal tandem duplication) and 3 other cases demonstrating the YWHAE-NUTM2B/E fusion from the files of one author (CRA), most of them included in previous publications5,14. All but one of these neoplasms had accompanying BCOR IHC for evaluation. We also reviewed 24 cases of genetically confirmed BCOR-CCNB3 bone and soft tissue sarcomas from the files of one author (CRA). Twelve of these cases had accompanying BCOR IHC.

Primary Renal Synovial Sarcoma Control Group

We identified 7 genetically confirmed primary renal synovial sarcomas from our files, all of which demonstrated SS18 rearrangements by FISH. These cases occurred in 5 males and 2 females. These patients ranged in age from 35 to 66 (mean age 49 years; median age 48.5 years). Of cases with known fusion partner, 3 of 4 were SSX2 while one was SSX1, consistent with the previously-reported distribution of gene fusions found in primary renal synovial sarcoma21.

Clear Cell Sarcoma of Kidney (CCSK) Control Group

We identified 9 CCSK from the files of one author (PA). These cases occurred in 6 males and 3 females, and ranged in age from 6 months to 42 months (mean 24 months, median 19 months). All 9 of these cases demonstrated strong nuclear labeling for BCOR by immunohistochemistry. Of the 5 cases studied genetically, 4 demonstrated BCOR internal tandem duplication (ITD), while one demonstrated the YWHAE-NUTM2B gene fusion.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described1, 5, 14, 19 for the following proteins on the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas: BCOR, SATB2, TLE1, cyclin D1, Bcl2, CD56, CD99, CD10, desmin, S100, cytokeratin AE1/3 and, cyclin D1. Immunohistochemistry for selected markers from this group were also performed on cases in the control groups.

Results

Case Reports

Case 1 was an 11 year-old male who presented with a 27 cm cystic renal neoplasm which was treated by radical nephrectomy. The nephrectomy specimen weighed 1,845 grams and no further follow-up is available.

Case 2 was a 12 year-old male who presented with a 13 cm solid and cystic renal neoplasm which was treated by radical nephrectomy. Fifteen months later, the patient developed an abdominal mass which represented a recurrence of the prior neoplasm.

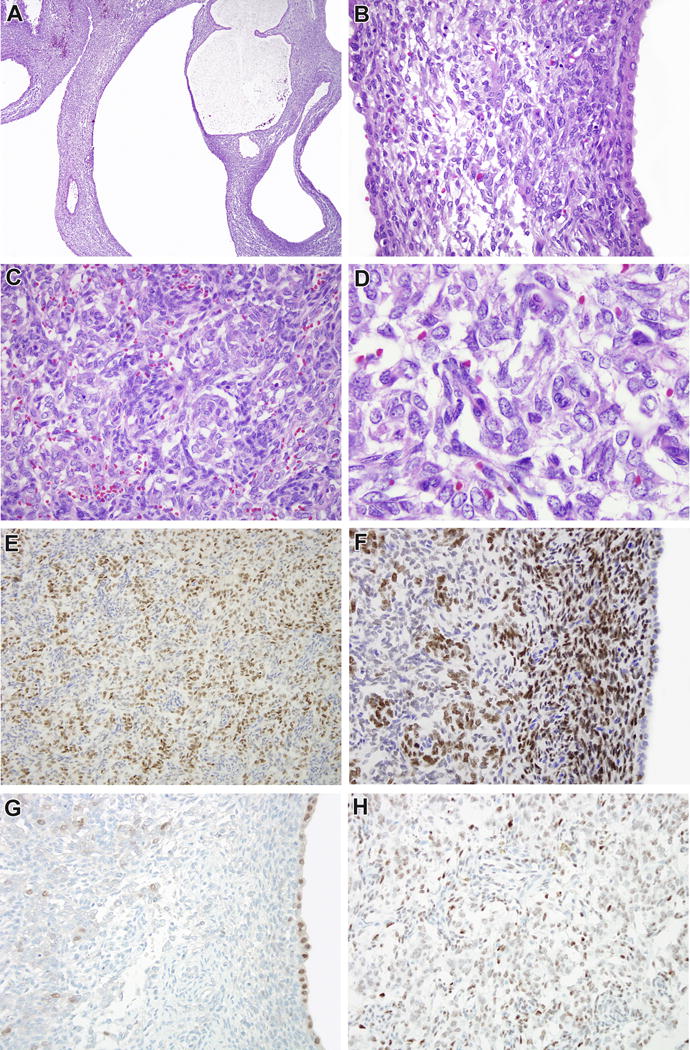

In both cases, the primary renal neoplasm was extensively cystic, with the cysts being lined by non-neoplastic, dilated native renal tubules. The cyst walls were variably cellular in both cases. In many areas of case 1, the cyst walls were composed of non-descript, non-pleomorphic, bland spindle cells which condensed beneath the cyst epithelium, creating a “cambium-like” appearance. In other areas, these cells became more plump and epithelioid, and alternated with prominent perivascular spindle cells in a pattern reminiscent of the biphasic cord cell-septal pattern of CCSK. The more epithelioid cell nuclei were bland, and had fine, open chromatin similar to that of CCSK (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Case 1. This 27 cm renal neoplasm was extensively cystic (A). The cysts were lined by bland cuboidal epithelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm consistent with native renal tubules, while the stroma was moderately cellular, non-pleomorphic, and demonstrated subepithelial condensations resembling a cambium layer (B). In more cellular areas, one could appreciate a biphasic cord cell-septal cell appearance similar to that seen in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK). A regular branching capillary vasculature was more evident in these areas. The cord cells demonstrated finely dispersed, open chromatin, particularly relative to the more hyperchromatic septal cells (D). Immunohistochemistry for BCOR highlighted the cord cells (E), and highlighted the cambium layer but not the entrapped cyst lining (F). Focally, the cord cells demonstrated weak labeling for PAX8 relative to the intense staining of the cyst lining (G). The cord cells were immunoreactive for SATB2 (not shown) and TLE1 (H).

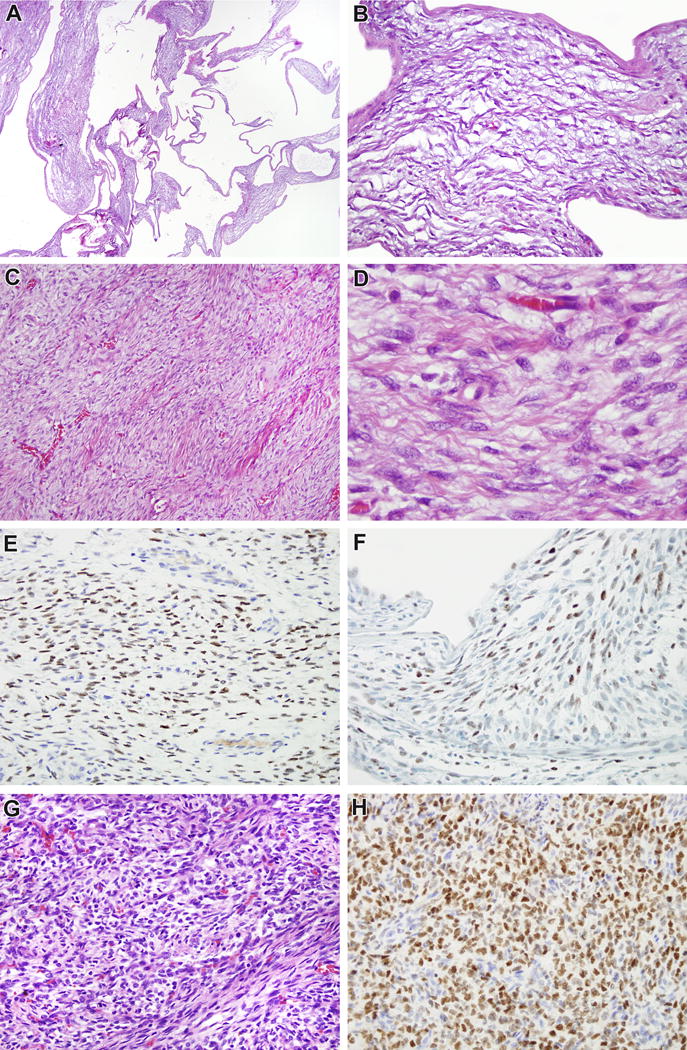

In case 2, the cystic primary renal neoplasm was extremely bland. The cyst walls were hypocellular and composed predominantly of uniform spindle cells with minimal cytoplasm, creating a resemblance to cystic nephroma or mixed epithelial stromal tumor. Focally, the cyst walls were slightly more cellular, and one could appreciate a biphasic cord cell/septal cell pattern that suggested CCSK. The neoplastic cells in the cyst walls were non-pleomorphic and lacked mitotic activity (Figure 2). The abdominal recurrence of this neoplasm, in contrast, demonstrated solid fascicles of cellular, non-pleomorphic spindle cells with frequent mitotic figures.

Figure 2.

Case 2. The original 13 cm renal neoplasm was extensively cystic (A) and the septa were relatively hypocellular in most areas (B), raising the differential diagnosis of cystic nephroma. Focally, more cellular areas in the septa demonstrated the branching capillary vasculature that suggested CCSK (C) and the cord cells between septa demonstrated bland, finely dispersed chromatin (D). The cord cells demonstrated nuclear labeling for BCOR (E), SATB2 (not shown) and TLE1 (F). The abdominal recurrence 15 months later was a highly cellular non-pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm which again had a suggestion of biphasic cord cell-septal cell appearance that is characteristic of CCSK (G). The cord cells demonstrated diffuse immunoreactivity for BCOR while the septal cells did not (H), highlighting this distinction.

Both cases demonstrate similar immunohistochemical profiles; therefore, they are discussed together. In both cases, the neoplasm demonstrated strong and diffuse nuclear labeling for BCOR. Importantly, BCOR IHC highlighted the biphasic pattern of these lesions, with strong nuclear labeling of the “cord cells” and absence of labeling in the prominent admixed “septal cells”, similar to the pattern previously described in CCSK (Figure 1E, 2E)5. As suggested by the morphology, the BCOR immunoreactive cells were less frequent and focally absent in the bland, hypocellular cyst walls of the primary cystic renal neoplasm in case 2, but comprised the majority of the cells in the solid, high grade spindle cell recurrence of that lesion (Figure 2H). Both neoplasms also demonstrated diffuse immunoreactivity for Bcl2, CD56, SATB2, cyclin D1, and TLE1 (Figure 1H, 2F). Desmin, S100 protein, cytokeratin AE1/3, and CD34 were negative in both cases. PAX8 was negative in both the primary and recurrent tumor in case 2 (native renal tubules in the primary were PAX8 positive, providing a positive internal control). In case 1, there was focal weak nuclear staining of the more epithelioid “cord cells”, but this was less intense than that of the entrapped native renal tubules that provided an internal control (Figure 1G).

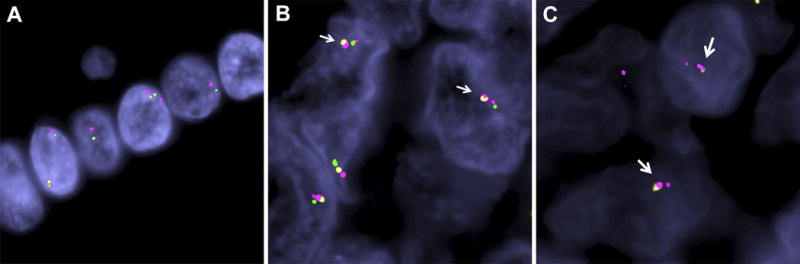

FISH demonstrated an inversion-fusion pattern between BCOR and CCNB3 in both cases, including both the bland cystic primary renal neoplasm in case 2 and its high grade abdominal recurrence (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Demonstration of BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion by FISH. A. Normal cells analyzed with FISH probes. The green-orange probes represent BCOR and the red flanking probe represents CCNB3. Note the normal, small gap between the two genes, which corresponds to 9MB. B. Case 1. The two neoplastic cells illustrated show a BCOR-CCNB3 fusion/inversion. The CCNB3 (red) shows a split signal into a larger fragment (centromeric CCNB3) and a smaller signal (telomeric CCNB3); while the BCOR shows a break of the green (telomeric) and orange (centromeric) signals. The end-result is a fusion between the centromeric BCOR signal (orange) to the centromeric CCNB3 (larger red) (arrows), along with fusion of telomeric BCOR signal (green) to telomeric CCNB3 signal (smaller red). C. Case 2. The two neoplastic cells illustrated show CCNB3 inversion reflected by the red probe split into two signals (larger, centromeric and smaller, telomeric) and a BCOR unbalanced break, with deletion of telomeric end (no green signal). The resulting fusion is composed of centromeric 5′BCOR (orange) to centromeric 3′CCNB3 (larger red) (red-yellow signals fused together, arrows).

Review of the control group of BCOR-related soft tissue sarcomas

The control group of 23 URCS/PMMTI soft tissue cases with either BCOR ITD or YWHAE fusions occurred in patients ranging from ages 2 weeks to 14 months. As previously described, these neoplasms overlap significantly with CCSK, in that they featured bland round, epithelioid to spindled “cord cells” with open chromatin and prominent “septal cells”14. There was strong nuclear labeling for BCOR in 21 of the 22 cases in which immunohistochemistry (IHC) was available. Importantly, the BCOR IHC highlighted the “cord cells” but not the “septal cells”, similar to the pattern noted in renal CCSK as previously noted5. Also of note, 1 case was predominantly composed of a high grade spindle cell component more typical of the BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas, while focal areas of spindling were noted in one third of cases14.

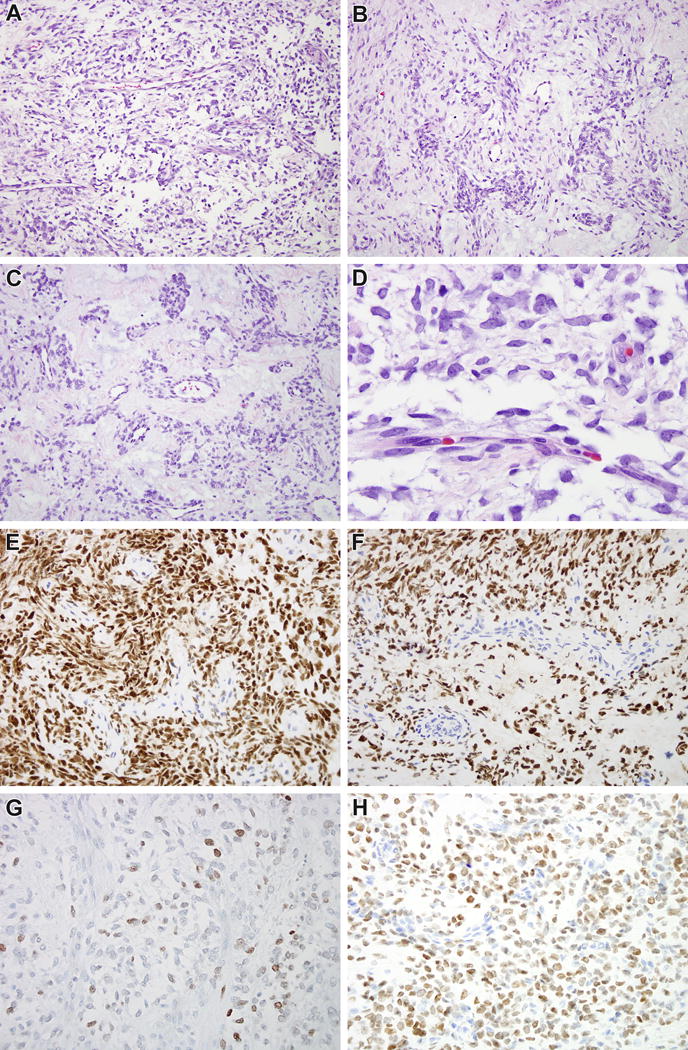

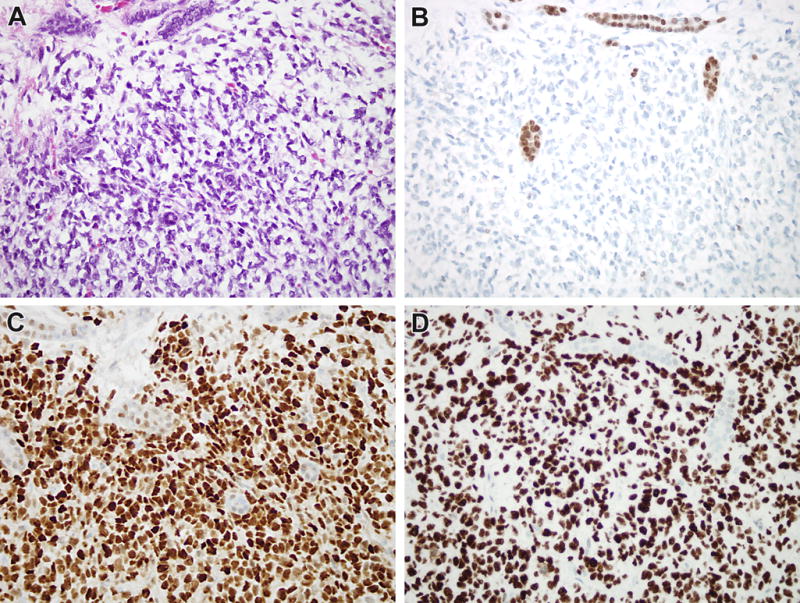

The 24 BCOR-CCNB3 bone and soft tissue sarcomas occurred in patients ranging in age from 2 years to 24 years. On review, all demonstrated undifferentiated round to spindle cell features that resembled the cellular spindle pattern of CCSK1, in which the “cord cells” acquire a more spindled appearance that resembles monophasic spindle cell synovial sarcoma1. BCOR immunohistochemistry highlighted the prominent labeling of “cord cells” and absence of labeling in the prominent “septal cell” component, as previously demonstrated in CCSK5, in all 12 cases in which it was performed (Figure 4). Also of note, a subset of bone/soft tissue cases with the BCOR-CCNB3 fusion demonstrated focally low grade myxoid areas which overlapped with URCS/PMMTI and the myxoid, hypocellular pattern of CCSK.

Figure 4.

BCOR-CCNB3 soft tissue sarcoma from comparison group. BCOR-CCNB3 soft tissue sarcomas demonstrated morphologic features that overlap with CCSK, including a branching capillary vasculature pattern separating epithelioid to spindled cord cells that are set in a myxoid stroma (A). The cord cells appear to have clear cell cytoplasm, but in fact this represents extracellular matrix separating the cells (B). Stromal hyalinization mimics the sclerosing pattern of CCSK (C). The chromatin is fine and evenly dispersed similar to that of CCSK (D). Immunohistochemistry for BCOR highlights the neoplastic cord cells, with absence of labeling in the septal cells (E, F), similar to that seen in CCSK. The cord cells demonstrate weak staining for PAX8 (G) and strong staining for SATB2 (H).

Of note, in one case PAX8 immunohistochemistry had been performed in a primary soft tissue BCOR-CCNB3 sarcoma, and demonstrated weak labeling in cord cells similar to that seen in renal BCOR-CCNB3 case 1 (Figure 4G).

Six of seven BCOR-CCNB3 bone/soft tissue sarcomas and all four URCS/PMMTI tested were immunoreactive for cyclin D1. Seven of nine BCOR-ITD URCS/PMMTI and five of nine soft tissue BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas were immunoreactive for CD99, though typically in a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern rather than a strong membranous distribution. Both BCOR-CCNB3–positive bone/soft tissue sarcomas tested demonstrated immunoreactivity for TLE1.

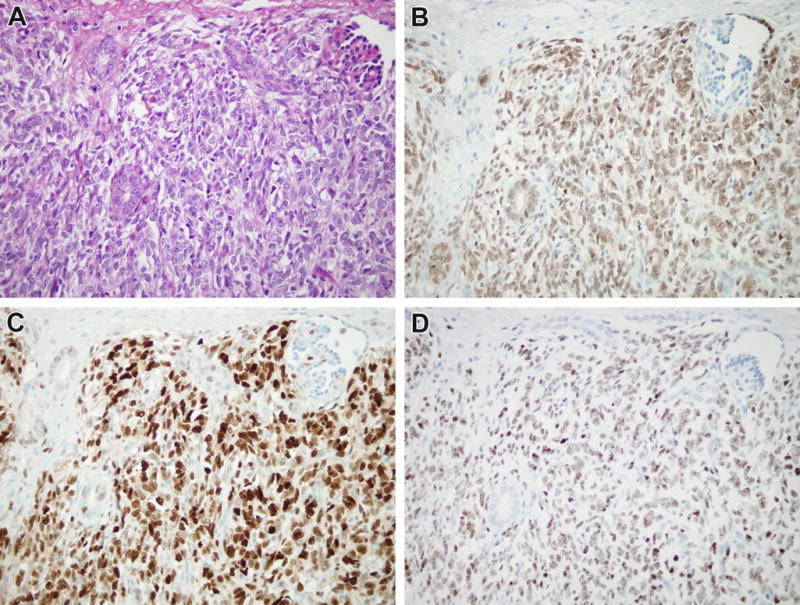

Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK) (control group)

All 9 CCSK cases demonstrated typical morphologic features, specifically cord cells with fine chromatin and indistinct cytoplasm set in a myxoid stroma and separated by a regular branching capillary vasculature lined by septal cells. All nine cases demonstrated strong diffuse nuclear labeling for BCOR in the cord cells. As expected from prior literature, three of seven cases studied (42%) demonstrated diffuse nuclear labeling for SATB2, and all five tested showed diffuse nuclear labeling for cyclin D1. Four of 5 tested cases demonstrated strong diffuse nuclear labeling for TLE1, as marker not previously studied in CCSK (Figure 5). One of 5 tested CCSK demonstrated strong, diffuse labeling for PAX8 (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Immunoprofile of CCSK. A. This CCSK from the control group demonstrates myxoid extracellular material separating cord cells, and branching capillary vasculature. Note the entrapped renal tubules at the upper and middle portions of the image. B. Like most cases, this CCSK was negative for PAX8. Note the entrapped native renal tubules serving as an internal control. C. The CCSK shows strong diffuse nuclear labeling for cyclin D1, while there is minimal weak labeling of the entrapped renal tubules. D. The neoplasm demonstrates strong diffuse nuclear labeling for TLE1.

Figure 6.

Immunoprofile of CCSK. A. This typical CCSK from the control group demonstrates bland epithelioid cord cells separated by a branching capillary vasculature. Note the entrapped glomerulus at the upper right, and the entrapped native renal tubules to the left and center of the field. B. In this case, the neoplastic cord cells and native renal tubules show strong nuclear labeling for PAX8. C. The neoplastic cord cells demonstrate strong, diffuse nuclear labeling for cyclin D1, while there is minimal labeling of entrapped nephrons. D. The neoplasm demonstrates diffuse nuclear labeling for TLE1.

Primary renal synovial sarcoma (control group)

The seven genetically confirmed primary renal synovial sarcomas were composed of cellular non-pleomorphic spindle cells associated with dilated native renal tubules in four cases, typical of monophasic spindle cell synovial sarcoma arising in the kidney19. Of these seven cases, four demonstrated nuclear immunoreactivity for BCOR (58%). As expected, four of five cases tested demonstrated strong diffuse nuclear labeling for TLE1, while three of five cases tested were positive for cyclin D1. Two of five cases tested demonstrated focal weak/equivocal staining for SATB2; the other three were completely negative.

Discussion

We report two primary renal sarcomas demonstrating BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion. In the absence of molecular findings, these cases were originally considered to be unclassified sarcomas with a differential diagnosis including CCSK and primary renal synovial sarcoma. As neoplasms with BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion, similar to sarcomas with BCOR-ITD, are associated with a BCOR-driven transcriptional profile, we interrogated the possible relationship of these neoplasms to CCSK. These cases were somewhat unusual for CCSK, in that they affected slightly older children (ages 11 and 12) compared to the mean CCSK age of 3, demonstrated predominant spindle morphology, and were associated with extensive dilation of native renal tubules resulting in extensive cystic change. In one case, the combination of hypocellular neoplastic cells within the septa and extensive cystic change created a mimic of a benign mixed epithelial stromal tumor or cystic nephroma. However, while somewhat unusual, the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas are certainly compatible with CCSK. The patient ages of the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas are well within the spectrum of CCSK, which in the largest study in the literature (351 cases) occurred in an age range of 2 months to 14 years1. Predominant spindle cell morphology and extensive cystic change mimicking cystic nephroma, as classically seen in renal synovial sarcoma, have also previously been described and illustrated in CCSK1. We found that the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas expressed TLE1, a sensitive marker of synovial sarcoma22,23 which had not previously been studied in CCSK: however, we found that TLE1 was also positive in the typical CCSK in our control group. Both BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas labeled for BCOR, cyclin D1 and SATB2 which are recognized markers of CCSK. Overall, taking together the common morphologic features of these neoplasms including the biphasic BCOR-immunopositive cord cells and BCOR-immunonegative septal cells, along with the immunoreactivity for cyclin D1, TLE1 and SATB2 in the cord cells in the absence of labeling for CD99, desmin, cytokeratin, S100 and CD34, the pathologic features fall within the broad spectrum of CCSK.

Despite their common transcriptional profile driven by a consistent upregulation of BCOR mRNA expression, some differences exist between soft tissue undifferentiated round cell sarcoma (URCS)/primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy (PMMTI), which harbors BCOR internal tandem duplication (ITD), and BCOR-CCNB3 bone and soft tissue sarcomas. First, CCNB3 overexpression both at the mRNA5,14 and protein15 levels is seen only in BCOR-CCNB3 bone/soft tissue sarcomas and not in URCS/PMMTI with BCOR ITD. Second, the age at presentation is different; URCS/PMMTI almost overwhelmingly occur in infants, while BCOR-CCNB3 soft tissue sarcomas typically affect teenagers and young adults. Third, most URCS/PMMTI have a heterogeneous appearance with alternating compact round cellular areas with hypocellular myxoid components, whereas BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas are uniformly highly cellular, rounded and often spindled neoplasms which overlap with Ewing sarcoma and synovial sarcoma. Despite these differences, our review of a large series of URCS/PMMTI and BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas of bone and soft tissue found significant areas of overlap. Specifically, PMMTI-like areas can be seen at the edge of BCOR-CCNB3 undifferentiated sarcomas of bone and soft tissue, and URCS/PMMTI often have higher grade areas that overlap with BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas. Previous studies from our group have highlighted morphologic similarities between the URCS/PMMTI harboring BCOR ITD and CCSK5. In this study, we note the similarity of BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas of bone/soft tissue and kidney with CCSK. This is highlighted by presence of cellular septa within the BCOR-CCNB3 soft tissue sarcomas which are very similar to those seen within CCSK. In both instances, the cellular septa do not label for BCOR, suggesting that these cellular septa represent a florid pericyte-rich reactive proliferations associated with these BCOR-CCNB3 driven neoplasms. Hence, just as in soft tissue where the BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas overlap with the URCS/PMMTI with BCOR ITD, the primary renal sarcomas with the BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion overlap with CCSK showing BCOR ITD (Table 1). We feel that minor differences between CCSK and the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas are less significant than their unifying features. However, greater experience with the clinicopathologic features and response to therapy of the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas are needed to further establish this link. We note that a single neoplasm with the BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion was recently reported in abstract form within a series reported as CCSK24. We propose that CCSK, URCS/PMMTI, and BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas of kidney and bone/soft tissue can be thought of as a “BCOR-alteration family” of renal and extra-renal neoplasms with a common genetic signature and overlapping (but not identical) clinicopathologic features (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of BCOR-related Neoplasms and Renal Synovial Sarcoma

| Typical CCSK | BCOR-CCNB3 Renal Sarcomas | URCS/PMMTI | BCOR-CCNB3 Bone/Soft Tissue Sarcoma | Renal Synovial Sarcoma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Age | 3 years (mean) | 11.5 years (mean) | <1 year | Teens | 43 years (median) |

| Morphology | Round/spindle cells separated by branching capillary vasculature in myxoid stroma; numerous variant patterns | Variably cellular spindle cell sarcoma associated with entrapped dilated renal tubules | Round to spindled primitive cells in myxoid background with | Cellular round/spindle cell sarcoma | Cellular spindle/round cell sarcoma often associated with entrapped dilated renal tubules |

| Genetics | BCOR ITD (90%); YWHAE-NUTM2B/E fusion (<10%) | BCOR-CCNB3 fusion | BCOR ITD | BCOR-CCNB3 fusion | SS18-SSX fusion |

| PAX8 | 20% positive | 50% focal positive | NA | 50% positive***** | Usually negative**** |

| BCOR | Positive** | Positive | Positive | Positive | 50% positive |

| Cyclin D1 | Positive*** | Positive | Positive | Positive | 60% positive (weak) |

| SATB2 | 42% positive** | Positive | 75% positive** | 100% positive** | Minimal/negative |

| TLE1 | 80% positive | Positive | NA | Positive* | Positive |

Table 2.

BCOR-Alteration Family of Neoplasms

| Clear Cell Sarcoma of Kidney (CCSK) |

| BCOR-CCNB3 Sarcomas of Kidney and Bone/Soft Tissue |

| Undifferentiated Round Cell Sarcoma/Primitive Myxoid Mesenchymal Tumor of Infancy (URCS/PMMTI) |

The focal PAX8 labeling of BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcoma case 1 might be considered unusual for CCSK, which has previously been considered negative for PAX8 though PAX2 labeling has been reported25. However, we found that PAX8 is positive in a minority of CCSK, and can be focally expressed in soft tissue BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas. Furthermore, a recent study found that PAX8 is expressed in over 50% of BCOR-CCNB3 soft tissue sarcomas26, and PAX8 immunoreactivity also been described in primitive round cell sarcomas such as alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma and rhabdoid tumor25. Hence, in the setting of primitive round/spindle cell neoplasms, PAX8 is not specific for renal parenchymal versus mesenchymal origin.

The predominantly spindle appearance of the BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas created significant overlap with synovial sarcoma, which was the main differential diagnosis for these cases. Morphologic and immunohistochemical overlap of BCOR-CCNB3 soft tissue sarcomas with synovial sarcoma has been reported27, as has overlap between CCSK and renal synovial sarcoma28. Along these lines, BCOR overexpression has been demonstrated in approximately half (49%) of soft tissue synovial sarcomas5, though BCOR expression had not been addressed in primary renal synovial sarcomas until now. In this study, we document that primary renal synovial sarcomas similarly overexpress BCOR in approximately half (60%) of cases. Primary renal synovial sarcomas also express cyclin D1, a sensitive marker of CCSK, and TLE1, a sensitive marker of soft tissue synovial sarcoma, furthering the potential overlap with BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcoma. As suspected based on previously reported expression profiling and immunohistochemical analysis of soft tissue synovial sarcoma5, SATB2 is less frequently expressed in renal synovial sarcoma than in typical CCSK or the renal BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas, providing one useful discriminatory immunohistochemical marker. While analysis of BCOR gene status and the SS18-SSX gene fusions typically resolve the differential diagnosis of CCSK and renal synovial sarcoma, there may also be significant overlap at the genetic level. Along these lines, a case of a poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma with a variant SS18L1-SSX1 gene fusion and complex rearrangements affecting the Xp11.22-4 region including disruption of BCOR and upregulation of BCOR protein has been reported20.

Our finding of overlap between BCOR-CCNB3 fusion-positive sarcomas of the kidney and soft tissue with CCSK has potential therapeutic implications. BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas of bone and soft tissues were initially recognized as a subset of EWS-non-rearranged “Ewing sarcomas”, and have historically been treated with Ewing sarcoma chemotherapy regimens, though some evidence exists that their behavior may be more indolent17. As such, BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas are typically treated as Ewing sarcomas at most centers today. Given the overlapping morphology of BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas which CCSK and their overlapping transcriptional profile, and given that patients with CCSK have been shown to benefit from specific doxorubicin-based chemotherapy1, 29, it seems logical to consider treating the BCOR-CCNB3 soft tissue sarcomas with CCSK-based therapy regimens (which emphasize Doxorubicin and do not include Ifosfamide) rather than Ewing sarcoma-based regimens (which include both Doxorubicin and Ifosfamide). The former chemotherapy regimen is overall less toxic, and at least in CCSK has demonstrated significant clinical benefit.

In summary, we report two primary renal sarcomas with the BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion. We demonstrate that while some features are unusual for CCSK, these neoplasms do overlap with CCSK at the morphologic, immunohistochemical, and genetic level. BCOR-CCNB3 renal sarcomas may account for a subset of cases currently classified as CCSK but which lack BCOR-ITD or YWHAE-NUTM2B/E gene fusions. Our findings support the concept of a BCOR-alteration family of renal and extrarenal neoplasms having a highly related genetic profile and similar (though not identical) clinicopathologic features, including CCSK, BCOR-CCNB3 sarcomas, and undifferentiated round cell sarcoma/primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy (URCS/PMMTI).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Norman Barker MA, MS, RBP for expert photographic assistance.

7-5-17

Disclosures: Supported in part by: P50 CA 140146-01 (CRA), P30-CA008748 (CRA), Cycle for Survival (CRA), Kristin Ann Carr Foundation (CRA), Dahan Translocation Carcinoma Fund (PA), Joey’s Wings (PA)

References

- 1.Argani P, Perlman EJ, Breslow NE, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: a review of 351 cases from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group Pathology Center. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:4–18. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gooskens SL, Furtwangler R, Vujanic GM, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2219–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirkovic J, Calicchio M, Fletcher CD, Perez-Atayde AR. Diffuse and strong cyclin D1 immunoreactivity in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Histopathology. 2015;67:306–12. doi: 10.1111/his.12641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jet Aw S, Hong Kuick C, Hwee Yong M, et al. Novel Karyotypes and Cyclin D1 Immunoreactivity in Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2015;18:297–304. doi: 10.2350/14-12-1581-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Jungbluth AA, Huang SC, Argani P, Agaram NP, Zin A, Alaggio R, Antonescu CR. BCOR Overexpression Is a Highly Sensitive Marker in Round Cell Sarcomas With BCOR Genetic Abnormalities. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1670–1678. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueno-Yokohata H, Okita H, Nakasato K, et al. Consistent in-frame internal tandem duplications of BCOR characterize clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Nat Genet. 2015;47:861–863. doi: 10.1038/ng.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astolfi A, Melchionda F, Perotti D, et al. Whole transcriptome sequencing identifies BCOR internal tandem duplication as a common feature of clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Oncotarget. 2015;6:40934–40939. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy A, Kumar V, Zorman B, et al. Recurrent internal tandem duplications of BCOR in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8891. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Meara E, Stack D, Lee CH, et al. Characterization of the chromosomal translocation t(10;17)(q22;p13) in clear cell sarcoma of kidney. J Pathol. 2012;227:72–80. doi: 10.1002/path.3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CH, Ou WB, Mariño-Enriquez A, et al. 14-3-3 fusion oncogenes in high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:929–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115528109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenny C, Bausenwein S, Lazaro A, et al. Mutually exclusive BCOR internal tandem duplications and YWHAE-NUTM2 fusions in clear cell sarcoma of kidney: not the full story. J Pathol. 2016;238:617–20. doi: 10.1002/path.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlsson J, Valind A, Gisselsson D. BCOR internal tandem duplication and YWHAE-NUTM2B/E fusion are mutually exclusive events in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55:120–3. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alaggio R, Ninfo V, Rosolen A, Coffin CM. Primitive myxoid mesenchymal tumor of infancy: a clinicopathologic report of 6 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:388–94. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000190784.18198.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Huang SC, Argani P, Chung CT, et al. Recurrent BCOR Internal Tandem Duplication and YWHAE-NUTM2B Fusions in Soft Tissue Undifferentiated Round Cell Sarcoma of Infancy: Overlapping Genetic Features With Clear Cell Sarcoma of Kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1009–20. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierron G, Tirode F, Lucchesi C, et al. A new subtype of bone sarcoma defined by BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion. Nat Genet. 2012;4(44):461–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen-Gogo S, Cellier C, Coindre JM, et al. Ewing-like sarcomas with BCOR-CCNB3 fusion transcript: a clinical, radiological and pathological retrospective study from the Société Française des Cancers de L’Enfant. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:2191–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puls F, Niblett A, Marland G, Gaston CL, Douis H, Mangham DC, Sumathi VP, Kindblom LG. BCOR-CCNB3 (Ewing-like) sarcoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 10 cases, in comparison with conventional Ewing sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1307–18. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters TL, Kumar V, Polikepahad S, et al. BCOR-CCNB3 fusions are frequent in undifferentiated sarcomas of male children. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:575–86. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argani P, Faria PA, Epstein JI, Reuter VE, Perlman EJ, Beckwith JB, Ladanyi M. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: Molecular and morphologic delineation of an entity previously included among embryonal sarcomas of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1087–1096. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200008000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Kenan S, Singer S, Tap WD, Swanson D, Dickson BC, Antonescu CR. BCOR upregulation in a poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma with SS18L1-SSX1 fusion-A pathologic and molecular pitfall. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2017;56:296–302. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argani P, Ladanyi M. Recent advances in pediatric renal neoplasia. Adv Anat Pathol. 2003;10:243–60. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foo WC, Cruise MW, Wick MR, Hornick JL. Immunohistochemical staining for TLE1 distinguishes synovial sarcoma from histologic mimics. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:839–44. doi: 10.1309/AJCP45SSNAOPXYXU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosemehmetoglu K, Vrana JA, Folpe AL. TLE1 expression is not specific for synovial sarcoma: a whole section study of 163 soft tissue and bone neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:872–8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang K, Wong MK, Aw SJ, Ng C, Rajasegaran V, Lian D, Kuick CH, Sudhanshi J, Loh E, Loh A, Yin M, Goytain A, Ng T, Teh BT. Clear Cell Sarcoma of Kidney Is Characterized by BCOR Gene Abnormalities Including Exon 16 Internal Tandem Duplications and BCOR-CCNB3 Gene Fusion. Modern Pathology. 2017;30(S2):465A. doi: 10.1111/his.13366. abstract 1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan R. PAX immunoreactivity in poorly differentiated small round cell tumors of childhood. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2014;33:244–52. doi: 10.3109/15513815.2014.920441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludwig K, Alaggio R, Zin A, Peron M, Guzzardo V, Benini S, Righi A, Gambarotti M. BCOR-CCNB3 Undifferentiated Sarcoma-Does Immunohistochemistry Help in the Identification? Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2017 Jan 1; doi: 10.1177/1093526617698263. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li WS, Liao IC, Wen MC, Lan HH, Yu SC, Huang HY. BCOR-CCNB3-positive soft tissue sarcoma with round-cell and spindle-cell histology: a series of four cases highlighting the pitfall of mimicking poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma. Histopathology. 2016;69:792–801. doi: 10.1111/his.13001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirose M, Mizuno K, Kamisawa H, Nishio H, Moritoki Y, Kohri K, Hayashi Y. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney distinguished from synovial sarcoma using genetic analysis: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(8):129. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1100-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furtwangler R, Gooskens SL, van Tinteren H, et al. Clear cell sarcomas of the kidney registered on International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) 93-01 and SIOP 2001 protocols: a report of the SIOP Renal Tumour Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3497–3506. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada Y, Kuda M, Kohashi K, et al. Histological and immunohistochemical characteristics of undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas associated with CIC-DUX4 and BCOR-CCNB3 fusion genes. Virchows Arch. 2017;470:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karafin M, Parwani AV, Netto GJ, Illei PB, Epstein JI, Ladanyi M, Argani P. Diffuse expression of PAX2 and PAX8 in the cystic epithelium of mixed epithelial stromal tumor, angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts, and primary renal synovial sarcoma: evidence supporting renal tubular differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1264–73. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822539a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.