Abstract

Recent work suggests that older adults may be less susceptible to the next-day effects of alcohol relative to younger adults. The effects of alcohol in younger adults may be mediated by sleep duration but, due to age differences in the contexts of alcohol use, this mediation process may not generalize to older adults. The present study examined age group (younger versus older adults) differences in how alcohol use influenced next-day tiredness during daily life. Reports of alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness obtained on ~101 days from 91 younger adults (age 20–31 years) and 75 older adults (age 65–80 years) were modeled using a multilevel, moderated mediation framework. Findings indicate that (1) Greater than usual alcohol use was associated with greater than usual tiredness in younger adults only; (2) greater than usual alcohol use was associated with shorter than usual sleep duration in younger adults only; and (3) shorter than usual sleep duration was associated with greater tiredness in both younger and older adults. For the prototypical younger adult, a significant portion (43%) of the association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness could be explained assuming mediation through sleep duration, while there was no evidence of mediation for the prototypical older adult. Findings of age differences in the mediation process underlying associations among alcohol use, sleep, and tiredness provide insight into the mechanisms driving recent observations of reduced next-day effects of alcohol in older relative to younger adults.

Keywords: sleep, alcohol, age differences, tiredness, within-person mediation

The experience of next-day tiredness is one of the most commonly reported residual symptoms of alcohol use (Penning et al., 2012). Alcohol administration leads to next-day tiredness in controlled, laboratory settings (Chait & Perry, 1994; Howland et al., 2008; Rohsenow et al., 2007), with the association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness also recently being observed during day-to-day life using an intensive repeated measures design (Patrick et al., 2016). While the next-day effects of alcohol are thought to be magnified in older adults due to age-related changes in how the body metabolizes alcohol (Blow, 1998; Meier & Seitz, 2008; Vestal et al., 1977), few studies have investigated these age differences. Emerging evidence indicates that the next-day effects of alcohol may instead be reduced in older adults relative to younger adults (Tolstrup et al., 2014). The present study examined age group differences, younger adults (age 20 to 31 years) versus older adults (age 65 to 80), in the within-person association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness and whether these differences may be explained by differences in sleep.

Next-Day Tiredness: The Role of Sleep Across Age

Generally, sleep serves a restorative function (Zisapel, 2007). However, when sleep patterns are disrupted, the restorative function of sleep is undermined. In particular, experience of tiredness or fatigue is more likely after reduced levels of Stage 3 deep sleep (Thomas et al., 2006), after fragmented sleep (Moore et al., 2001), and when individuals self-report poorer sleep quality (Kaynak et al., 2006) or lower than usual sleep duration (Kamdar et al., 2004; Patrick et al., 2016). Sleep duration and quality have been observed to decrease with age (Floyd et al., 2007; Lemola & Richter, 2013). Older adults exhibit more awakenings and reduced amounts of slow wave sleep relative to younger adults (Conte et al., 2014; Van Cauter et al., 2000). Health status is an important factor underlying changes in sleep observed across age (Bliwise, 1993; Luca et al., 2015) but normative, biological changes also play a role. In particular, findings that sleep duration decreases and nighttime awakenings tend to increase with age suggest that older adults have lower sleep needs (e.g., Dijk et al., 2010). The homeostatic pressure to sleep is regulated by increases in extracellular levels of the neuromodulator adenosine which, during waking hours, are thought to facilitate the transition from wake to sleep by inhibiting activity in the cholinergic basal forebrain (Thakkar, Winston, & McCarley, 2003; Basheer, Strecker, Thakkar, & McCarley, 2004). There is a loss of adenosine A1 receptors with age (Cheng et al., 2000; Ekonomou et al., 2000), implying that older adults have reduced sensitivity to increasing adenosine concentrations and, thus, experience lower sleep pressure (Mander et al., 2017), which manifests as shorter sleep durations, even when older adults are provided with long periods of sleep opportunity (Klerman & Dijk, 2008).

Despite some evidence for lower sleep pressure in older relative to younger adults, both sleep duration and quality remain important predictors of daytime fatigue as people age (Alapin et al., 2000; Goldman et al., 2008). Sleep duration is still related to next-day cognitive and affective functioning in older adults (Gamaldo et al., 2010; McCrae et al., 2008). This has led some researchers to suggest that, rather than reflecting lower sleep need in older adults, shorter sleep duration and continued vulnerability for sleep-deprivation associated next-day impairments in cognitive functioning may reflect an impaired ability to register or generate unmet sleep needs (Mander et al., 2017). In sum, even in the context of age-related changes in typical levels of sleep duration and quality, within-person variability in sleep remains important for next-day functioning in older adults.

Age Differences in the Association Between Alcohol and Next-Day Tiredness

Alcohol use is thought to lead to tiredness due, at least partially, to its detrimental effects on sleep (Rohsenow et al., 2006). While alcohol shortens sleep-onset latency (Williams et al., 1983), alcohol is also associated with poorer quality sleep (Rohsenow et al., 2010). Laboratory studies find that sleep is shallower and more fragmented in the second half of the night after consuming alcohol than after consuming placebo (Feige et al., 2006; Landolt et al., 1996). Similarly, in-situ studies of individuals’ day-to-day life also find that individuals have decreased sleep quality and/or sleep duration after alcohol use (Galambos et al., 2009; Lydon et al., 2016; Patrick et al., 2016).

Age-related changes in physical composition and functioning – including decreases in lean body mass and body water volume (Vestal et al., 1977) and decreased metabolism of alcohol (Meier & Seitz, 2008) – influence how older adults respond to alcohol (see Blow, 1998). In the hour following oral administration of alcohol, older adults have higher blood alcohol concentrations than younger adults (Gartner et al., 1996). In animal models, older relative to younger animals have higher ethanol levels in the brain and blood in the hours following alcohol administration (Wiberg et al., 1970) and show increased residual symptoms of alcohol (Brasser & Spear, 2002).

Despite these laboratory-based findings, remarkably little research has examined potential age differences in the severity of effects of alcohol on next-day functioning in humans. One of the few studies examining age differences in the next-day effects of alcohol use, a cross-sectional survey of men and women aged 18 to 84 years, observed that hangover symptoms following binge drinking were more common in younger age groups than in older age groups (Tolstrup et al., 2014), with those age differences not explained by differences in individuals’ usual amount of alcohol consumption or frequency of binge drinking. The finding that older adults have fewer hangover symptoms than younger adults does not align with the laboratory or animal research. This discrepancy may be due to a variety of real-world compensatory processes unavailable in the tightly controlled laboratory setting, including the use of strategies to avoid hangovers, greater experience with and biological tolerance for alcohol, and natural selection processes that reduce the population of older drinkers to those who experience the least severe residual effects of alcohol.

Age Differences in the Association Between Alcohol and Sleep Duration

One difference between laboratory and real world alcohol use that may drive age-related differences in the residual effects of alcohol use is age-related differences in the association between alcohol use and sleep duration. In the laboratory, alcohol impacts sleep quality, but not sleep duration (MacLean & Cairns, 1982; Yules et al., 1966). In the laboratory studies, however, there were few constraints on sleep duration and participants were able to get a full night of sleep. Outside of the laboratory, in contrast, alcohol use and sleep deprivation are often experienced together with work, family, and other demands potentially constraining the possibility for longer sleep duration after alcohol use (Verster, 2008). And, these demands likely differ systematically with age. Generally, daily demands tend to decrease with older age as family and work duties decrease (e.g., after retirement). Younger adults report more frequent work, interpersonal, and home stressors relative to older adults (Charles et al., 2010; Neupert et al., 2007). These age-related differences in daily life contexts, together with changes in priorities and motivations, have implications for leisure time and may lead to greater regularities in the daily routines of older adults relative to younger adults (Brose et al., 2013; Carstensen et al., 1999; Lieberman & Wurtman, 1989).

There is increasing evidence that the greater regularity in daily routines observed in older relative to younger adults extends to sleep behaviors. In daily diary studies that track sleep behavior over multiple days, older adults have more consistent sleep routines than younger adults, with less day-to-day variability in total sleep time (Dillon et al., 2015; Shoji et al., 2015), bed in-time, and bed out-time (Kramer et al., 1999). The increased regularity in sleep schedules among older adults may have implications for sleep duration following alcohol use. Older adults tend to use alcohol at meal times or as an activity to bring the day to a close, to drink at home, and to drink alone (Burruss et al., 2015; Sacco et al., 2015). In contrast, the alcohol use of younger adults occurs more frequently in public rather than private places (Gronkjaer et al., 2010; Wells et al., 2005). These age differences in the context of alcohol use (e.g., alcohol use at bars and discos vs. drinking at home) alongside the more general tendency for older relative to younger adults to maintain consistent routines may render younger adults more susceptible to reductions in sleep duration when they use alcohol and, in turn, more susceptible to the experience of next-day tiredness. In sum, age differences in the association between alcohol use and tiredness, whereby older adults experience less marked effects of alcohol use on tiredness, may result from age differences in the association between alcohol and sleep duration.

Within-Person Theory, Study Design, and Analysis

Notably, this hypothesis is about between-person (i.e., age group) differences in within-person associations (e.g., on days when sleep duration is shorter than usual, tiredness will be greater than usual). This focus on within-person processes necessitates the use of intensive longitudinal designs that facilitate capture of day-to-day fluctuations in the behaviors of interest (Molenaar, 2004; Ram & Gerstorf, 2009). In particular, experience sampling methods, whereby individuals regularly report about their daily lives for substantial periods of time (e.g., 100 days) provide opportunity to both articulate and test how specific within-person processes unfold outside the laboratory (e.g., Bolger et al., 2003; Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1983; Shiffman et al., 2008). Once collected, such data can be examined using analytic frameworks that appropriately disambiguate within- and between-person effects (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). Particularly useful are multilevel modeling frameworks that account for the nesting of repeated measures within persons and allow for examination of between-person differences in within-person associations (Snijders & Bosker, 2012). Extensions of these models allow for examination of within-person mediation (Bauer et al., 2006) and between-person differences in within-person variability (Hedeker et al, 2012; Hoffman, 2007). Applied to intensive longitudinal data collected from both younger and older adults, these models provide for elegant testing of age differences in within-person processes.

The Present Study: Age Differences in How Sleep Duration Mediates the Association Between Alcohol and Next-Day Tiredness

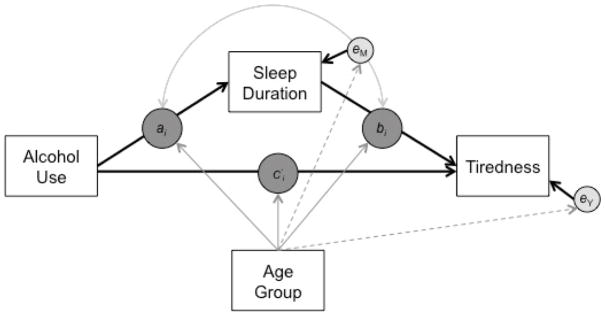

Using intensive longitudinal data, we examined age group differences in within-person associations among alcohol use, sleep duration, and tiredness. A schematic of the inquiry is shown in Figure 1. Following from findings of greater tiredness after alcohol use (Patrick et al., 2016), we hypothesized that on days when individuals used more alcohol than usual, they would experience greater than usual next-day tiredness (c′ > 0). Following from findings of shorter sleep duration following alcohol use (Kamdar et al., 2004), we hypothesized that this association would be mediated by sleep duration. That is, we hypothesized that the association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness would be accounted for by a path where greater than usual alcohol use would lead to shorter than usual sleep duration (ai) and, in turn, to next-day tiredness (bi). Importantly, the effects of alcohol use on both tiredness and sleep duration were hypothesized for younger but not older adults (Dillon et al., 2015; Gronkjaer et al., 2010; Tolstrup et al., 2014), but, given the continued relevance of sleep duration in tiredness at older ages (Alapin et al., 2000), it was hypothesized that both younger and older adults would experience increases in tiredness following nights of shorter than usual sleep duration (bi). Finally, following the proposition that there is greater inconsistency in routines among younger adults, we expected that older adults would exhibit less variability in sleep and tiredness relative to younger adults. Specifically, fluctuations in sleep duration and next-day tiredness (i.e., in eM, eY) were allowed to differ across age groups. In sum, the present study leveraged intensive repeated measures data and multilevel mediation models to provide further insight into the recent finding that the next-day effects of alcohol were decreased in older relative to younger adults (Tolstrup et al., 2014) by examining age group differences in the path between alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness.

Figure 1.

A simplified schematic of the multilevel, moderated mediation (1-1-1) model with heterogeneous variance. Alcohol use, sleep duration, and tiredness are person-centered day-level repeated measures variables. Age group is person-level variable. The solid arrows from age group to ai, bi, and c′i indicate that the within-person associations among alcohol use, sleep duration, and tiredness may be moderated by age group, and the dashed arrows from age group to the residuals of sleep duration and next-day tiredness indicate that the variance of these residuals may also differ between age groups.

Method

The present study made use of data from the COGITO study, an intensive longitudinal study designed for the study of day-to-day intraindividual variability across a range of domains, including cognition, stress, affect, and health (Brose et al., 2011; Wolff et al., 2012). Detailed information on the larger study is available in Schmiedek, Lövdén, and Lindenberger (2010). The ethical review board of the Max Plank Institute for Human Development approved the study.

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 101 younger (51.5% women, age: 20–31 years) and 103 older (49.5% women, age: 65–80 years) adults recruited through newspaper advertisements, word-of-mouth recommendations, and fliers circulated in Berlin, Germany (see Schmiedek et al., 2010). After being recruited into the study and going through a 10-day run-in and pretesting period, participants began a micro-longitudinal module wherein they were asked to report to the laboratory three or more times per week at times of their choosing (between 8:00am and 8:30pm Monday through Saturday) to complete a short battery of questionnaires and cognitive tests (about 1 hour). As part of the daily assessment, participants provided information about their current and prior day’s activities, feeling states, and behaviors (e.g., sleep).

With interest in the within-person associations among daily alcohol use, sleep duration, and tiredness, the analysis sample was limited to those participants who reported using alcohol on at least one day throughout the 100-days phase. Specifically, we set aside data from the n = 10 younger, and n = 28 older adults with zero alcohol use (abstainers). The group of younger adult abstainers did not differ from their drinking peers on average sleep duration (t99 = 0.53, p=.60), tiredness (t99 = −0.54, p=.59), or number of days in the study (t99 = 0.47, p=.64). Similarly, the group of older adult abstainers did not differ from their drinking peers on average sleep duration (t101 = −1.25, p=.22) or number of days in the study (t101 = −1.01 p=.32). However, the older abstainers did have significantly higher average levels of tiredness (M = 2.77, SD = 1.12) than their drinking peers (M = 2.19, SD = 0.93; t101 = 2.66, p=.02). After removing the abstainers, complete data was available for 16598 (99.3%) of 16725 possible days, nested within nyoung = 91 younger persons (Mean years of education = 12.44, SD=1.35) and nold = 75 older persons (Mean years of education = 10.95, SD=1.75) that each provided, on average, 100.79 days of data (SD = 2.62, range = 87 to 109) and 101.13 days of data (SD = 2.50, range = 90 to 106), respectively. Notably, a similar pattern of findings was obtained when these abstainers were included in the analysis.

Measures

The present study made use of younger and older adults’ reports of alcohol use, sleep duration, and tiredness obtained in the ~100-session micro-longitudinal battery.

Alcohol Use

Individuals’ alcohol use was measured at each session as the total amount (in liters) of alcohol consumed within the previous 24 hours. Using a graphical user interface, participants completed an alcohol consumption grid. Pictures of alcoholic drinks (including beer, wine, liquor and their associated alcohol content) were placed around the outside of a grid. Participants were instructed to drag pictures of all the drinks they had consumed within the last 24 hours and drop them into the grid. Each of the drink icons could be dropped into the grid as many times as necessary as a counter (visible to participants) kept track of the total alcohol that had been added to the grid. Alcohol use was computed in liters from this grid for each participant for each day and converted to number of standard drinks (14 grams or milliliters of alcohol = 1 drink). On average, younger adults consumed 0.64 drinks per day (SD = 1.48, Range = 0 to 16.91) and older adults consumed 0.61 drinks per day (SD = 0.95, Range = 0 to 11.27). On average, the proportion of days that younger adults consumed alcohol was 0.26 (SD = .18) and was 0.39 (SD = .32) for older adults.

Sleep Duration

Previous night’s sleep duration was measured at the beginning of each session (after the assessment of alcohol use and before the cognitive tasks) as response to the item, “How many hours did you sleep last night?”, with an open response format where the participants could enter hours and minutes. On average, younger adults slept for 7.20 hours (SD = 1.48, Range = 0 to 14) and older adults slept for 7.06 hours (SD= 1.11, Range = 0 to 13).

Next-Day Tiredness

At each session, individuals’ level of tiredness was measured (before the cognitive tasks) as the response to the item: “How tired/fresh do you feel right now?”, with responses provided on a 0 (very tired) to 7 (very fresh) scale. The item was reverse scored (7 – y) so that higher scores indicated greater tiredness. On average, across all days, average level of tiredness was Myoung = 3.29 (SD = 1.39, Range = 0 to 7) for the younger adults and Mold = 2.19 (SD = 1.17, Range = 0 to 7) for the older adults. To emphasize the differences in the temporal frames of the tiredness and alcohol use assessments, we refer to the tiredness variable as next-day tiredness.

Age Group

Age group was coded as a binary variable, younger adult (20 to 31 years) = 0 and older adult (65 to 80 years) = 1.

Data Analysis: Moderated Multilevel (1-1-1) Mediation Model with Heterogeneous Variance

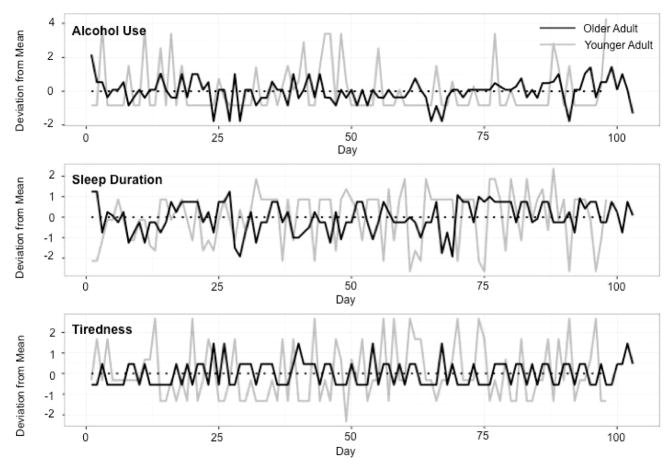

Our main interest was to examine age differences in how sleep duration may mediate the within-person association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness. Taking advantage of and accommodating the nested nature of the micro-longitudinal data (16,598 days nested within 166 persons), hypotheses were examined within a multilevel modeling framework (Snijders & Bosker, 2012) using a moderated within-person (1-1-1) mediation model (Bauer et al., 2006). To focus the analysis on within-person associations, all three variables of interest were conceived as having time-invariant and time-varying components and split accordingly (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). For example, the repeated measures of next-day tiredness were split into a person-level, time-invariant variable that was calculated as the within-person mean across the repeated measures, and a day-specific, time-varying variable that was calculated for each day as the deviation in next-day tiredness from the person-specific mean. Figure 2 illustrates the time-varying alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness variables of a prototypical younger adult (gray continuous line) and a prototypical older adult (black continuous line). Days on which the continuous lines are above the dotted line at zero are days of more than usual levels of alcohol use, sleep duration, or next-day tiredness for that individual. Days on which the continuous lines are below the dotted line at zero are days of less than usual levels of alcohol use, sleep duration, or next-day tiredness. Immediately apparent in the figure are differences in overall variability between these persons (a point we shall return to later). After splitting, the three time-invariant components (stable between-person differences) were set aside and the three time-varying components (day-to-day within-person changes) were examined using a multilevel mediation model of the form shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

An illustration of the trivariate, intensive-repeated data for a younger adult (gray continuous line) and an older adult (black continuous line). The continuous lines indicate changes in alcohol use (top panel), sleep duration (middle panel), and next-day tiredness (bottom panel) across days along the x-axis, relative to each participant’s person-specific, time-invariant means that are indicated by the dotted lines at zero along the y-axis.

In brief, the within-person (1-1-1) mediation models is conceived as two Level 1 regression equations: one where the mediator variable, Mit = sleepdurationit, is regressed on the causal variable, Xit = Alcoholit,

| (1) |

and one where the outcome variable, Yit = Tirednessit, is regressed on the mediator variable, Mit, and the causal variable, Xit,

| (2) |

where ai, bi, and c′i are person-specific regression coefficients that indicate the unique within-person associations, and the zero is included to make explicit that between-person differences in baseline levels were set aside. The person-specific coefficients are modeled at Level 2 as a function of between-person differences in age. Specifically,

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where γa0, γb0, and γc′0 indicate the prototypical within-person associations among the three variables for a younger adult; γa1, γb1, and γc′1 indicate age group differences in the prototypical within-person associations, and uai, ubi, and uc′i are residual unexplained between-person differences in the extent of within-person associations that are assumed normally distributed with zero means and a full covariance structure, ~N(0, ΣG).

Importantly, the within-person residuals, eMit and eYit, are also assumed to be normally distributed with zero means and person-specific variances, σ2eMi and σ2eYi, that may also differ across age group. Formally, the model accommodated heterogeneous variances such that

| (6) |

| (7) |

where α0M and α0Y indicate the prototypical residual within-person variance for the mediator and outcome variables for the young group, and α1M and α1Y indicate the difference in those variances between age groups.

In practice, Equations 1 through 7 are combined and estimated simultaneously in a single multilevel model with heterogeneous variances using data that are restructured so that the two outcome variables (mediator Mit = sleepdurationit, and outcome Yit = tirednessit) are collected into a single repeated measures variable, Zit, along with dummy indicators, Smi and Syi, that indicate whether the specific observation of Zit belongs to the mediator or outcome variable and that serve to “turn-on” and “turn-off” specific parameters for each row in the data (see Bauer et al., 2006; Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013; McCallum et al., 1997). Using this set-up, all models were estimated using SAS 9.3 PROC MIXED (Littel et al., 1997).

Model parameters were then used to test for age group differences in extent of within-person mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2002). Specifically, (following Bauer et al., 2006) the conditional expected value of the indirect and direct effects were calculated as

| (8) |

| (9) |

respectively, where w is age group and the γs and σuai,ubi are estimates from the model above. Evidence for moderated mediation is provided by a joint test of the significance of γa1 and γb1 (implemented using the IndTest macro, http://www.quantpsy.org/medn.htm), and extent of mediation is derived as the percentage of the total effect attributable to the indirect effects in each age group. Finally, the robustness of the results was examined by including effects of day of the week (weekdays coded 0, Saturday coded 1) and within-person centered versions of sleep quality and time of assessment on next-day tiredness and sleep quality and day of the week on sleep duration, including interactions with age group to test for potential moderation. The pattern of results for the associations among alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness across age groups was unchanged. As such, the more parsimonious models are reported here.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness variables by age group are presented in Table 1. In line with previous research demonstrating less variance in older relative to younger adults in sleep-related variables (Dillon et al., 2015; Wolff et al., 2012), older adults relative to younger adults had lower intraindividual standard deviations for both sleep duration (average iSDOlder = 0.68, iSDYounger = 1.27; t164 =11.32, p <.001) and next day tiredness (average iSDOlder = 0.68, iSDYounger = 1.10; t164 =9.35, p <.001). These differences thus suggested use of the multilevel model with heterogeneous variances described above.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Daily Alcohol Use, Sleep Duration, and Next-day Tiredness Variables for Younger and Older Age Groups

| Intraindividual Means and Standard Deviations | Intraindividual Correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| iMean (SD) | iSD (SD) | Alcohol | Sleep | |

| Younger Adults (n = 91) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Alcohol (drinks) | 0.64 (0.52) | 1.19 (0.72) | -- | |

| Sleep (hours) | 7.20 (0.68) | 1.27 (0.38) | −0.11 [−0.53, 0.23] | -- |

| Tiredness (0 to 7) | 3.29 (0.81) | 1.10 (0.30) | 0.07 [−0.20, 0.46] | −0.36 [−0.81, 0.01] |

|

| ||||

| Older Adults (n = 75) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Alcohol | 0.61 (0.63) | 0.61 (0.36) | -- | |

| Sleep | 7.06 (0.84) | 0.68 (0.27) | −0.03 [−0.33, 0.35] | -- |

| Tiredness | 2.19 (0.93) | 0.68 (0.28) | −0.01 [−0.26, 0.29] | −0.30 [−0.77, 0.09] |

Notes: iMean = intraindividual mean; iSD = intraindividual standard deviation; SD = sample-level standard deviation. Alcohol use is reported in number of drinks (1 drink = 14 grams alcohol). Correlation matrices for each age group contain the average intraindividual correlation, and the range of those correlations in brackets [min, max].

Associations Between Alcohol, Sleep Duration, and Tiredness Across Age Groups

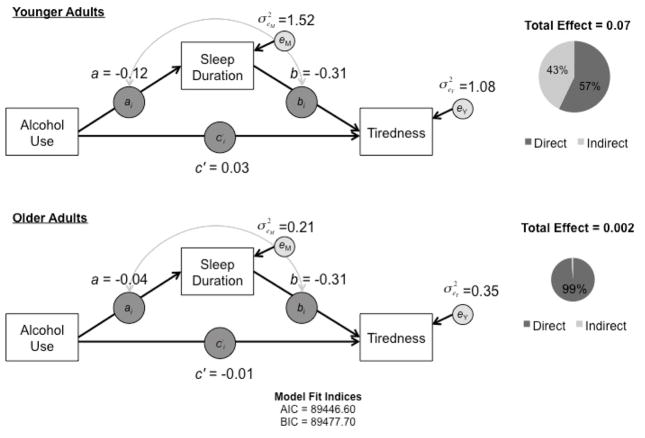

Results from the moderated mediation model examining age group differences in the within-person associations among alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness are presented in Table 2 and Figure 3. For the younger adults, there were significant associations between alcohol use and sleep duration (γ10 = −0.12, p<.0001), sleep duration and next-day tiredness (γ20 = −0.31, p<.0001), and alcohol use and next-day tiredness (γ30 = 0.03, p=.004). The associations were in the expected directions, with greater than usual alcohol use associated with shorter than usual sleep duration, shorter than usual sleep duration associated with more than usual next-day tiredness, and greater than usual alcohol use associated with greater than usual next-day tiredness.

Table 2.

Results of the Moderated Mediation (1-1-1) Model Examining the Associations Among Alcohol Use, Sleep Duration, and Next-Day Tiredness in Older and Younger Adults

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | SE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlcoholUse → SleepDuration (γ10 ) | −0.12* | 0.02 | <.0001 | |

| SleepDuration → NextDayTiredness (γ20 ) | −0.31* | 0.02 | <.0001 | |

| AlcoholUse → NextDayTiredness (γ30 ) | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.004 | |

| AgeGroup x AlcoholUse → SleepDuration (γ11 ) | 0.08* | 0.03 | 0.002 | |

| AgeGroup x SleepDuration → NextDayTiredness (γ21 ) | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.96 | |

| AgeGroup x AlcoholUse → NextDayTiredness (γ31 ) | −0.04* | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

|

| ||||

| Random Effects | Estimate | SE | p-value | |

|

| ||||

| Random Slope Variance | ||||

|

|

0.01* | 0.003 | <.0001 | |

|

|

0.03* | 0.003 | <.0001 | |

|

|

0.004* | 0.001 | 0.004 | |

|

|

−0.003 | 0.003 | 0.32 | |

|

|

0.001 | 0.002 | 0.57 | |

|

|

−0.004* | 0.002 | 0.03 | |

| Residual Variance | ||||

| NextDayTiredness (α0Y ) | 1.08* | 0.02 | <.0001 | |

| AgeGroup x NextDayTiredness(α1Y ) | −0.87* | 0.02 | <.0001 | |

| SleepDuration (α0M ) | 0.44* | 0.02 | <.0001 | |

| AgeGroup x SleepDuration (α1M ) | −0.30* | 0.03 | <.0001 | |

|

| ||||

| Fit Indices | ||||

|

| ||||

| AIC | 89446.60 | |||

| BIC | 89477.70 | |||

Note: Nobservations = 16598 days nested within 166 persons; AIC = Akaike information criteria; BIC = Bayesian information criteria; SE = standard error.

p < .05.

Figure 3.

Results of the moderated within-person mediation model by age group. Age group differences emerged in the alcohol use to sleep duration and alcohol use to tiredness associations, with stronger within-person associations observed in younger relative to older adults. Pie charts depict age group differences in the total effect of alcohol use on next-day tiredness (size of circle) and the portion of this effect accounted for by sleep duration (proportion of gray).

In line with the hypothesized moderated mediation pattern, the within-person associations between alcohol use and sleep duration, and between alcohol use and next-day tiredness, were moderated by age group, γ11 = 0.08 (p =.002) and γ31 = −0.04 (p =.04), respectively. As seen in Figure 3, associations between alcohol use and sleep duration, as well as alcohol use and next-day tiredness, were stronger among younger adults than among older adults. As expected, there was no evidence of age group differences in the within-person association between sleep duration and next-day tiredness (γ21 = 0.001, p =.96). As well, residual variances of both next-day tiredness and sleep duration were significantly smaller among older adults than among younger adults (α1 =−0.87, p<.0001; α3 =−0.30, p<.0001).

Age Group Differences in Mediation by Sleep Duration

Of particular interest were age group differences in the role of sleep duration as a mediator. Indeed, the indirect effect between alcohol use and next-day tiredness (aibi ) was moderated by age group, χ2 (2) = 9.48, p = .009. For younger adults, the estimated average indirect effect was 0.03 (SE = 0.01, p <.0001) and the estimated average total effect of alcohol use on next-day tiredness was 0.07 (SE = 0.01, p < .0001). Thus, about 43% of the association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness was mediated through sleep duration in younger adults. For older adults, the estimated average indirect effect was 0.01 (SE = 0.01, p = .30), while the estimated average total effect of alcohol use on next-day tiredness was 0.002 (SE = 0.02, p = .89). As such, the age differences emerge in part because there was no significant association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness to be mediated in older adults. Age group differences in the size of the average total effect of alcohol use on next-day tiredness are represented by the relative sizes of the pie charts in Figure 3, with the proportion of gray indicating the extent of mediation by sleep duration.

Discussion

The present study tested age group differences in the effects linking alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness in day-to-day life. As hypothesized, we observed age group differences in the association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness. In younger adults, greater than usual alcohol use was associated with shorter than usual sleep duration which, in turn, was associated with greater than usual next-day tiredness. In older adults, shorter than usual sleep duration was also related to greater next-day tiredness, but alcohol use was not associated with sleep duration. Thus, there appears to be a potentially causal link from alcohol use to sleep duration to next-day tiredness for younger adults but not for older adults, even after accommodating differences in variability in sleep duration and tiredness.

Age Differences in The Associations Among Alcohol use, Sleep Duration, and Tiredness

Older adults are perceived to be at particular risk for detrimental alcohol-related outcomes (Novier et al., 2015). This perception of older adults’ increased vulnerability to effects of alcohol stems largely from laboratory-based findings that indicate higher blood-alcohol concentrations in the hour following alcohol administration (Gartner et al., 1996). However, one of the few studies to examine age differences in the next-day effects of alcohol use – employing a cross-sectional, survey design – observed reduced next-day effects of alcohol in older relative to younger adults (Tolstrup et al., 2014), a finding that does not align with laboratory research. This discrepancy between findings from laboratory and survey studies motivated the present examination of age differences in the association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness – outside of the tightly controlled laboratory setting where restrictions on behavior may preclude participants’ engagement in real-world, compensatory processes that counteract the effects of alcohol.

We found that greater than usual alcohol use was associated with greater than usual next-day tiredness in younger but not older adults. Thus, the present study aligns with the survey findings and conflicts with the laboratory findings. By design, this intensive longitudinal study, wherein each participant provided 3+ months of reports about their daily experiences, complements both the survey and laboratory studies by providing insight into what happens during daily life. That is, this study examined alcohol use in the context of many potential compensatory processes that may counteract alcohol’s next-day effects rather than what can happen in strictly controlled laboratory conditions (Mook, 1983) or what individuals report happened. Alcohol use, sleep duration, and tiredness were collected proximal to their occurrence using a measurement approach designed to minimize retrospective biases often associated with questionnaires that ask participants to recall and aggregate information about longer time periods (e.g., previous 30 days; Schwarz, 2007). Coupling the intensive longitudinal data with an analytic framework that appropriately disambiguated within- and between-person effects (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013), we were able to examine age group differences in the within-person associations of interest. While previous work highlighted that older adults report fewer hangover symptoms than younger adults (Tolstrup et al., 2014), the present study provided more direct evidence that within-person variations in alcohol use are yoked to changes in next-day tiredness among younger adults, but are not yoked among older adults.

A Role for Sleep Duration

The present study considered the role sleep duration might play as a mediator of the association between alcohol use and next-day tiredness and the age group differences therein. Sleep has long been known to serve a restorative function, with shorter sleep duration associated with greater next-day tiredness (Moore et al., 2001; Patrick et al., 2016; Zisapel, 2007). We observed no age differences in the association between sleep duration and next-day tiredness, suggesting that the restorative power of sleep pervades at both younger and older ages. In contrast, the association between alcohol use and sleep duration was observed in younger adults but not in older adults. Alcohol use does not generally affect total sleep duration in laboratory studies (MacLean & Cairns, 1982; Yules et al., 1996). However, few constraints are placed on sleep duration following alcohol use in laboratory paradigms. Generally, the laboratory study designs allow participants to get a full night of sleep. In daily life, however, alcohol use and sleep deprivation are often experienced together due to work, family, and other demands (Patrick et al., 2016; Verster, 2008).

The age group differences in the association between alcohol use and sleep duration reported here are novel and may reflect age differences in maintaining sleep-related routines in the context of alcohol use. Developmental theories highlight age-related differences in daily demands (Charles et al., 2010), priorities, and motivations (Carstensen et al., 1999) that have implications for younger and older individuals’ ability to maintain routines – including sleep-related routines (Brose et al., 2013). Specific to sleep-related routines in the context of alcohol use, younger adults’ alcohol use occurs more frequently in public rather than private places (Gronkjaer et al., 2010; Wells et al., 2005), thus rendering it more difficult for them to get to bed. On the other end of the night, younger adults may have more morning duties and constraints, whereas older adults may have greater opportunity to sleep in. This interpretation aligns with the age group differences in residual variances and with previous research highlighting that older adults have more consistent sleep routines than younger adults (Dillon et al., 2015; Kramer et al., 1999; Shoji et al., 2015). In sum, alcohol use does not interfere with older adults’ sleep duration. This allows older adults to circumvent the path from alcohol use to next-day tiredness via reduced sleep duration observed in younger adults.

Limitations and Outlook

It is important to consider the findings in light of the study’s strengths and limitations. First, collection of data over many days (> 100) from many participants (> 150) provided for robust examination of between-person differences in within-person processes. However, the cadence of data collection (3+ times per week) precludes examination of some processes. Supplemental data on the timing of alcohol ingestion throughout the day will provide for more detailed examination of the specific processes through which alcohol influences sleep (Leffingwell et al., 2014). Relatedly, a proposed mechanism for age differences in the association between alcohol use and sleep duration are age differences in the context of alcohol use (public versus private) and age differences in the tendency to maintain routines. Data were not available to test this hypothesis and, while it is in line with previous research (Burruss et al., 2015; Kramer et al., 1999; Wells et al., 2005), future work will be required to test this possibility.

Collection of polysomnography and actigraphy data alongside self-reported sleep measures will allow greater insight into how age-related changes in specific components of the sleep architecture contribute to differences in how alcohol influences sleep across the life span (Krystal & Edinger, 2008) and will provide more accurate estimates of sleep duration (Lauderdale et al., 2008). This will be important to overcome potential reporting biases that may have been introduced through the use of self-reported sleep duration that varied across time of day, followed alcohol use, and was reported concurrently with tiredness. However, the relatively short period (i.e., hours) between assessment and the events of interest (i.e., sleep duration and alcohol use) compared to studies using more distal retrospective reports likely minimized recall bias (Schwarz, 2007). Reporting biases are also relevant for the alcohol use measure, with some evidence available that younger adults underestimate the amount consumed relative to older adults (Stockwell et al., 2014).

Second, the non-mandatory nature of the study and daily assessments suggests consideration of selection effects. For example, the rates of alcohol use in the present study are lower than those reported in studies that drew random samples of German adults (e.g., Haenle et al., 2006). Given that alcohol use is generally higher on weekends (Kushnir & Cunningham, 2014; Sieri et al., 2002), lack of information on alcohol use on Saturdays in the present study may contribute to under-assessment. Selection processes may have also functioned during the study. For example, participants might have chosen not to come to the laboratory on days on which they were suffering hangovers. If such self-selection tendencies existed and differed across age groups, the age-comparative results may be biased.

Third, while tiredness is one of the most commonly reported residual effects of alcohol use (Penning et al., 2012), alcohol may also directly or indirectly influence a variety of other symptoms or functions (e.g., loss of appetite, dizziness, stomach ache, cognitive speed). Future studies should further consider how the within-person mediation approaches facilitated by intensive longitudinal designs may provide additional insight into the mechanisms and behaviors affected by alcohol use. Relatedly, while sleep is theorized to mediate the effects of alcohol on a number of next-day effects (e.g., tiredness, concentration problems, reduced appetite), its role as a mediator for other effects is likely more minimal (e.g., thirst, anxiety, coordination problems; see Verster, 2008 for discussion). As such, when considering further next-day effects of alcohol beyond tiredness, considering mediators beyond sleep duration may be more appropriate.

Fourth, any causal interpretation of the effects that combine to the investigated mediation model is based on strong assumptions. For example, the statistical model assumes that all common cause variables influencing both sleep duration and tiredness have been modeled and/or accounted for. Specifically, estimation requires assumption that the within-person variations in alcohol use are unrelated to the residuals of sleep duration and tiredness and that these residuals are not correlated with each other. Presence of unmeasured causes beyond alcohol use (e.g., daily health) may bias results. While these considerations should lead to caution regarding a strict causal interpretation of the mediation model, the suggested mediating role of sleep duration seems to provide a reasonable explanation for the observed pattern of significant age differences in the bivariate associations of the three variables under study.

Finally, given the intensive nature of the study, with the study aimed at participants interested in practicing cognitive tasks for 4–6 days a week for a period of 6 months, generalization to other samples must be done cautiously. Individuals who participate in such studies are special persons who are willing to engage with substantial burden. Adoption of strategies to recruit and retain representative samples (see Mody et al., 2008 for strategies specific to older adults), and use of passive data collection approaches (e.g., sensors integrated into watches, phones, bracelets, and other clothing; (Nusser et al., 2006) will increase potential for study of representative samples.

Synopsis.

In summary, the current study extends previous examinations of age differences in the next-day effects of alcohol (Tolstrup et al., 2014) by demonstrating age group differences in the chain linking alcohol use, sleep duration, and next-day tiredness during daily life. Younger adults experienced greater than usual tiredness after greater than usual alcohol use, an effect that was partially explained by reductions in sleep duration. In contrast, while older adults experienced greater than usual tiredness after less sleep, neither tiredness nor sleep was associated with alcohol use. As such, the path from alcohol to tiredness via sleep duration was not present in the older adult group. Viewed next to laboratory studies of the effects of alcohol (Brasser & Spear, 2002; Meier & Seitz, 2008), the results highlight the importance of considering how age group differences in daily life routines may contribute to differences in how alcohol use affects daily life.

Acknowledgments

David M. Lydon-Staley, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, The Pennsylvania State University; Nilam Ram, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, The Pennsylvania State University, and German Institute for Economic Research, Berlin, Germany; Annette Brose, German Institute for Economic Research, Berlin, Germany, Max Plank Institute for Human Development, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Berlin, Germany, Humboldt University Berlin, Berlin, Germany, and The Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium; Florian Schmiedek, German Institute for Economic Research, Berlin, Germany, Max Plank Institute for Human Development, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Berlin, Germany, and German Institute for International Education Research, Frankfurt/Main, Germany. This study was supported by the Max Planck Society, including a grant from Max Planck Society’s innovation fund (M.FE.A.BILD0005); the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Sofja Kovalevskaja Award (to Martin Lövdén) donated by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF); the German Research Foundation (DFG; KFG 163); and the BMBF (CAI). David Martin Lydon-Staley was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA T32 DA017629) and an ISSBD-JJF Mentored Fellowship for Early Career Scholars, Nilam Ram by the National Institute on Health (R01 HD076994, R24 HD041025, and UL TR000127) and the Penn State Social Science Research Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- Alapin I, Fichten CS, Libman E, Creti L, Bailes S, Wright J. How is good and poor sleep in older adults and college students related to daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and ability to concentrate? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000;49:381–390. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basheer R, Strecker RE, Thakkar MM, McCarley RW. Adenosine and sleep–wake regulation. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;73:379–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:142–163. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow F. Substance Abuse Among Older Adults. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series No. 26. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau J-P. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brasser SM, Spear NE. Physiological and behavioral effects of acute ethanol hangover in juvenile, adolescent, and adult rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:305–320. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose A, Scheibe S, Schmiedek F. Life contexts make a difference: Emotional stability in younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28(1):148–159. doi: 10.1037/a0030047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose A, Schmiedek F, Lövdén M, Lindenberger U. Normal aging dampens the link between intrusive thoughts and negative affect in reaction to daily stressors. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(2):488–502. doi: 10.1037/a0022287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burruss K, Sacco P, Smith CA. Understanding older adults’ attitudes and beliefs about drinking: perspectives of residents in congregate living. Ageing and Society. 2015;35:1889–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54(3):165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chait LD, Perry JL. Acute and residual effects of alcohol and marijuana, alone and in combination, on mood and performance. Psychopharmacology. 1994;115:340–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02245075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Luong G, Almeida DM, Ryff C, Sturm M, Love G. Fewer ups and downs: daily stressors mediate age differences in negative affect. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65(3):279–286. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JT, Liu IM, Juang SW, Jou SB. Decrease of adenosine A-1 receptor gene expression in cerebral cortex of aged rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;283:227–229. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte F, Arzilli C, Errico BM, Giganti F, Iovino D, Ficca G. Sleep measures expressing ‘functional uncertainty’ in elderlies’ sleep. Gerontology. 2014;60:448–57. doi: 10.1159/000358083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk DJ, Groeger JA, Stanley N, Deacon S. Age-related reduction in daytime sleep propensity and nocturnal slow wave sleep. Sleep. 2010;33:211–223. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon HR, Lichstein KL, Dautovich ND, Taylor DJ, Riedel BW, Bush AJ. Variability in self-reported normal sleep across the adult age span. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences. 2015;70:46–56. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekonomou A, Pagonopoulou O, Angelatou F. Age-dependent changes in adenosine A1 receptor and uptake site binding in the mouse brain: An autoradiographic study. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2000;60:257–265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000415)60:2<257::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feige B, Gann H, Brueck R, Hornyak M, Litsch S, Hohagen F, Riemann D. Effects of alcohol on polysomnographically recorded sleep in healthy subjects. Alcoholism Clinical & Experimental Research. 2006;30:1527–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd JA, Janisse JJ, Jenuwine ES, Ager JW. Changes in REM-sleep percentage over the adult lifespan. Sleep. 2007;30:829–836. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Dalton AL, Maggs JL. Losing sleep over it: daily variation in sleep quantity and quality in Canadian students’ first semester of university. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:741–761. [Google Scholar]

- Gamaldo AA, Allaire JC, Whitfield KE. Exploring the within-person coupling of sleep and cognition in older African Americans. Psychology & Aging. 2010;25:851–7. doi: 10.1037/a0021378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner U, Schmier M, Bogusz M, Seitz HK. Blood alcohol concentrations after oral alcohol administration--effect of age and sex. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 1996;34:675–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman SE, Ancoli-Israel S, Boudreau R, Cauley JA, Hall M, Stone KL, … Newman AB. Sleep problems and associated daytime fatigue in community-dwelling older individuals. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2008;63:1069–1075. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grønkjær M, Vinther-Larsen M, Curtis T, Grønbæk M, Nørgaard M. Alcohol use in Denmark: A descriptive study on drinking contexts. Addiction Research & Theory. 2010;18:359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Demirtas H. Modeling between-subject and within-subject variances in ecological momentary assessment data using mixed-effects location scale models. Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31:3328–3336. doi: 10.1002/sim.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenle MM, Brockman SO, Kron M, Bertling U, Mason RA, … Kratzer W. Overweight, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol consumption in a cross-sectional random sample of German adults. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L. Multilevel models for examining individual differences in within-person variation and covariation over time. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:609–629. [Google Scholar]

- Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Allensworth-Davies D, Almeida A, Minsky SJ, Arnedt JT, Hermos J. The incidence and severity of hangover the morning after moderate alcohol intoxication. Addiction. 2008;103:758–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamdar BB, Kaplan KA, Kezirian EJ, Dement WC. The impact of extended sleep on daytime alertness, vigilance, and mood. Sleep medicine. 2004;5:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaynak H, Altintaş A, Kaynak D, Uyanik Ö, Saip S, Ağaoğlu J, … Siva A. Fatigue and sleep disturbance in multiple sclerosis. European Journal of Neurology. 2006;13:1333–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman EB, Dijk DJ. Age-related reduction in the maximal capacity for sleep – implications for insomnia. Current Biology. 2008;18:1118–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer CJ, Kerkhof GA, Hofman WF. Age differences in sleep-wake behavior under natural conditions. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27:853–860. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(99)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir V, Cunningham JA. Event-specific drinking in the general population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:968–972. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal AD, Edinger JD. Measuring sleep quality. Sleep Medicine. 2008;9:S10–S17. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolt HP, Roth C, Dijk DJ, Borbely AA. Late-afternoon ethanol intake affects nocturnal sleep and the sleep EEG in middle-aged men. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;16:428–36. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199612000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M. The experience sampling method. In: Reis HT, editor. New Directions for Methodology of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Vol. 15. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1983. pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Sleep duration: How well do self-reports reflect objective measures? The CARDIA sleep study. Epidemiology. 2008;19:838–845. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318187a7b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffingwell TR, Cooney NJ, Murphy JG, Luczak S, Rosen G, Dougherty DM, Barnett NP. Continuous objective monitoring of alcohol use: 21st century measurement using transdermal sensors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;37:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman HR, Wurtman JJ. Circadian rhythms of activity in healthy young and elderly humans. Neurobiology of Aging. 1989;10:259–265. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(89)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS system for mixed models. 2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon DM, Ram N, Conroy DE, Pincus AL, Geier CF, Maggs JL. The within-person association between alcohol use and sleep duration and quality in situ: an experience sampling study. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;61:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luca G, Haba RJ, Andries D, Tobback N, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, … Tafti M. Age and gender variations of sleep in subjects without sleep disorders. Annals of Medicine. 2015;47:482–91. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1074271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Kim C, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Study multivariate change using multilevel models and latent curve models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1997;32:215–253. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3203_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean AW, Cairns J. Dose-response effects of ethanol on the sleep of young men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1982;43:434–444. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mander BA, Winer JR, Walker MP. Sleep and human aging. Neuron. 2017;94:19–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae CS, McNamara JP, Rowe MA, Dzierzewski JM, Dirk J, Marsiske M, Craggs JG. Sleep and affect in older adults: Using multilevel modeling to examine daily associations. Journal of Sleep Research. 2008;17:42–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier P, Seitz HK. Age, alcohol metabolism and liver disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2008;11:21–26. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f30564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM, Freeman M, Marcantonio ER, Magaziner J, Studenski S. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:2340–2348. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar PCM. A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement. 2004;2:201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mook DG. In defense of external validity. American Psychologist. 1983;38:379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Moore P, Bardwell WA, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE. Association between polysomnographic sleep measures and health-related quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Sleep Research. 2001;10:303–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62(4):P216–P225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novier A, Diaz-Granados JL, Matthews DB. Alcohol use across the lifespan: An analysis of adolescent and aged rodents and humans. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2015;133:65–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser SM, Intille SS, Maitra R. Emerging technologies and next-generation intensive longitudinal data collection. In: Walls TA, Schafer JL, editors. Models for Intensive Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 254–277. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Griffin J, Huntley ED, Maggs JL. Energy Drinks and Binge Drinking Predict College Students’ Sleep Quantity, Quality, and Tiredness. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2016.1173554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning R, McKinney A, Verster JC. Alcohol hangover symptoms and their contribution to the overall hangover severity. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47:248–252. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Gerstorf D. Time structured and net intraindividual variability: Tools for examining the development of dynamic characteristics and processes. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:778–791. doi: 10.1037/a0017915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyner A, Horne JA. Gender- and age-related differences in sleep determined by home-recorded sleep logs and actimetry from 400 adults. Sleep. 1995;18:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Howland J, Arnedt JT, Almeida AB, Minsky S, Kempler CS, Sales S. Intoxication With Bourbon Versus Vodka: Effects on Hangover, Sleep, and Next-Day Neurocognitive Performance in Young Adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Howland J, Minsky SJ, Almeida A, Roehrs TA. The acute hangover scale: A new measure of immediate hangover symptoms. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1314–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Howland J, Minsky SJ, Arnedt JT. Effects of heavy drinking by maritime academy cadets on hangover, perceived sleep, and next-day ship power plant operation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:406–415. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P, Burruss K, Smith CA, Kuerbis A, Harrington D, Moore AA, Resnick B. Drinking behavior among older adults at a continuing care retirement community: affective and motivational influences. Aging & Mental Health. 2015;19:279–289. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.933307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 13.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedek F, Lövdén M, Lindenberger U. Hundred days of cognitive training enhance broad cognitive abilities in adulthood: findings from the COGITO study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2010;2 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Retrospective and concurrent self-reports: The rationale real-time data capture. In: Stone A, Shiffman S, Atienza A, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone A, Hufford M. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji KD, Tighe CA, Dautovich ND, McCrae CS. Beyond mean values: Quantifying intraindividual variability in pre-sleep arousal and sleep in younger and older community-dwelling adults. Sleep Science. 2015;8:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieri S, Agudo A, Kesse E, Klipstein-Grobusch K, San-Jose B, … Slimani N. Patterns of alcohol consumption in 10 European countries participating in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) project. Public Health Nutrition. 2002;5:1287–96. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. 2. London, UK: Sage Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Zhao J, Macdonald S. Who under-reports their alcohol consumption in telephone surveys and by how much? An application of the ‘yesterday method’ in a national Canadian substance use survey. Addiction. 2014;109:1657–1666. doi: 10.1111/add.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar MM, Winston S, McCarley RW. A1 receptor and adenosinergic homeostatic regulation of sleep-wakefulness: effects of antisense to the A1 receptor in the cholinergic basal forebrain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(10):4278–4287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04278.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KS, Bardwell WA, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE. The toll of ethnic discrimination on sleep architecture and fatigue. Health Psychology. 2006;25:635–642. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolstrup JS, Stephens R, Grønbaek M. Does the severity of hangovers decline with age? Survey of the incidence of hangover in different age groups. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:466–470. doi: 10.1111/acer.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cauter E, Leproult R, Plat L. Age-related changes in slow wave sleep and REM sleep and relationship with growth hormone and cortisol levels in healthy men. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:861–868. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verster JC. The alcohol hangover–a puzzling phenomenon. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2008;43:124–126. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestal RE, McGuire EA, Tobin JD, Andres R, Norris AH, Mezey E. Aging and ethanol metabolism. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1977;21:343–354. doi: 10.1002/cpt1977213343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Graham K, Speechley M, Koval JJ. Drinking patterns, drinking contexts and alcohol-related aggression among late adolescent and young adult drinkers. Addiction. 2005;100:933–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.001121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg GS, Trenholm HL, Coldwell BB. Increased ethanol toxicity in old rats: changes in LD50, in vivo and in vitro metabolism, and liver alcohol dehydrogenase activity. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1970;16:718–727. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(70)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willams DL, MacLean AW, Cairns J. Dose-response effects of ethanol on the sleep of young women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1983;44:515–523. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1983.44.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JK, Brose A, Lövdén M, Tesch-Römer C, Lindenberger U, Schmiedek F. Health is health is health? Age differences in intraindividual variability and in within-person versus between-person factor structures of self-reported health complaints. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:881. doi: 10.1037/a0029125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yules RB, Freedman DX, Chandler KA. The effect of ethyl alcohol on man’s electroencephalographic sleep cycle. Electroencephalograpy & Clinical Neurophysiology. 1966;20:109–111. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(66)90153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisapel N. Sleep and sleep disturbances: biological basis and clinical implications. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2007;64:1174–1186. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6529-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]