Abstract

Leptin increases glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in red-type skeletal muscle. However, the mechanism remains unknown. We have investigated the role of β2-adrenergic receptor (AR), the major β-AR isoform in skeletal muscle, and AMPK in leptin-induced muscle glucose uptake of mice. Leptin injection into the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) increased 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) uptake in red-type skeletal muscle in wild-type (WT) mice accompanied with increased phosphorylation of the insulin receptor (IR) and Akt as well as of norepinephrine (NE) turnover in the muscle. Leptin-induced 2DG uptake was not observed in β-AR-deficient (β-less) mice despite that AMPK phosphorylation was increased in the muscle. Forced expression of β2-AR in the unilateral hind limb of β-less mice restored leptin-induced glucose uptake and enhancement of insulin signalling in red-type skeletal muscle. Leptin increased 2DG uptake and enhanced insulin signalling in red-type skeletal muscle of mice expressing a dominant negative form of AMPK (DN-AMPK) in skeletal muscle. Thus, leptin increases glucose uptake and enhances insulin signalling in red-type skeletal muscle via activation of sympathetic nerves and β2-AR in muscle and in a manner independent of muscle AMPK.

Introduction

Leptin inhibits food intake and increases energy expenditure in animals1,2. It also increases glucose utilization and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in certain peripheral tissues including skeletal muscle, without affecting plasma glucose and insulin levels, in rodents3–8. In addition, leptin markedly ameliorates metabolic abnormalities associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans and animals with lipodystrophy by increasing insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues9,10, and it alleviates streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes in rodents11. The mechanism by which leptin increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues has remained incompletely understood, however.

Skeletal muscle is a key tissue in whole-body energy metabolism and is responsible for insulin resistance associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes12. Glucose and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle are regulated by insulin, but also by the central nervous system. We and other thus previously showed that peripheral injection of leptin or leptin injection into the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) of rodents increases glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity in red-type skeletal muscle such as the soleus as well as in heart muscle and BAT (brown adipose tissue), but not in white adipose tissue (WAT), without change in plasma glucose and insulin level3–5,7. These effects of peripheral leptin were abolished by injection of an inhibitor of extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) signalling into the VMH8. Specific ablation of the leptin receptor in steroidogenic factor 1 (SF1)-positive cells in the VMH induced obesity and increased susceptibility to a high-fat diet in mice13. Recent study also showed that SF1 expression in the VMH is required for beneficial metabolic effects of exercise14. Furthermore, we recently showed that activation of SF1 neurons in the VMH by DREADD (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drug) technology increases insulin sensitivity in red-type of skeletal muscle, heart and BAT, but not WAT15.

To examine the effect of leptin injection and activation of SF1 neurons by DREADD on insulin sensitivity in the peripheral tissues, we performed hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp8,15. In basal period, activation of SF1 neurons by DREADD as well as peripheral or VMH injection of leptin increased Rd (glucose disappearance rate) and glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscles, heart and BAT. This effect was accompanied by an increase in Ra (glucose appearance rate) and activation of hepatic phosphorylase a activity, thereby maintaining blood glucose level. In hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp period, leptin strongly increased Rd and glucose uptake in the same tissues, and Ra was suppressed by inhibiting phosphorylase a activity and mRNA expression of PEPCK and G6Pase. Thus, our results suggested that VMH leptin increases whole-body glucose turnover during basal period and insulin sensitivity in some peripheral tissues including red-type skeletal muscle.

Activation of sympathetic nerves and β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs) is required for leptin-induced glucose uptake in peripheral tissues5. The β-AR antagonist propranolol and guanethidine, a blocker of sympathetic nerve activity, were thus each shown to attenuate this effect of leptin5. Activation of sympathetic nerves and β2-AR are also necessary for the exercise-induced increase in peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor–γ coactivator–1α (PGC-1α) mRNA abundance in skeletal muscle16. However, whether leptin-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle also requires muscle β2-ARs has remained unknown. Previous studies revealed that β-AR agonist increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle17,18, but others showed that catecholamines inhibits or has no effect on glucose uptake in skeletal muscle19,20.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) functions as a cellular “fuel gauge” and its activation stimulates glucose uptake and FAO in skeletal muscle21. We previously showed that injection of leptin into the medial hypothalamus including the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH) and VMH increased FAO in red-type skeletal muscle via activation of AMPK as well as of sympathetic nerves and α-ARs in the muscle tissue6. AMPK activation is sufficient to mimic exercise- or muscle contraction–induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle22–25.

We have now examined the roles of β2-AR, the major β-AR isoform in skeletal muscle26,27, and of AMPK in leptin-induced glucose uptake and enhancement of insulin signalling in skeletal muscle. The central effects of leptin were evaluated in β-AR–deficient (β-less) mice28 and in mice expressing a dominant negative form of AMPK (DN-AMPK) specifically in skeletal muscle29. The β2-AR was forcibly expressed in red-type skeletal muscle in the right hind limb of β-less mice. Our results suggest that leptin injection into the VMH increases glucose uptake and enhances insulin signalling in red-type skeletal muscle via β2-AR, but not via AMPK. Thus, our findings provide an important insight into regulation of glucose metabolism by the central nervous system and its potential for therapeutic manipulation.

Results

Leptin increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues of WT but not β-less mice

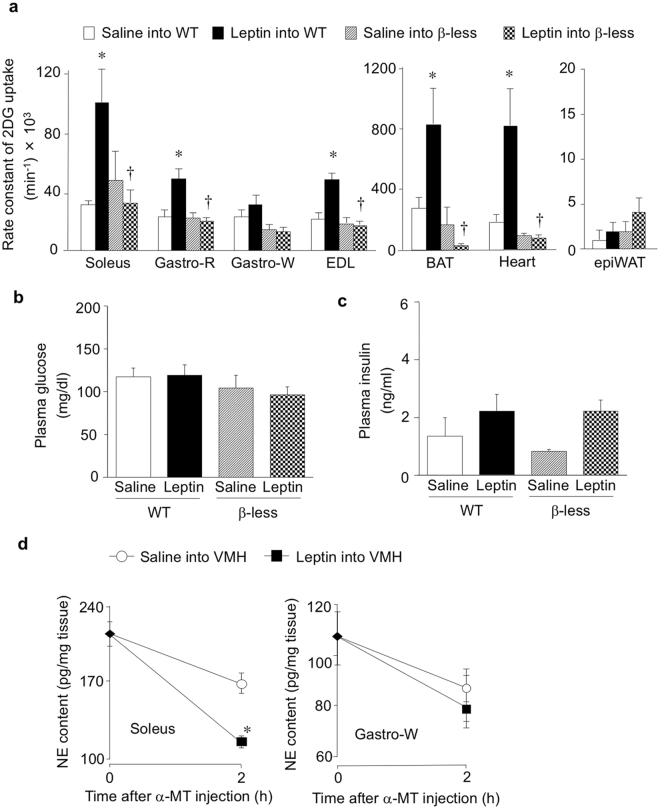

We examined the effects of leptin injection into the VMH on glucose uptake in peripheral tissues of β-less and WT mice. Consistent with previous observations4,5,7,30, the rate constant of 2DG uptake, a marker of glucose uptake activity, was significantly increased in red-type [soleus and Gastro-R (red portion of gastrocnemius)] and mixed-type (EDL, extensor digitorum longus) skeletal muscle, but not in Gastro-W (white portion of gastrocnemius) or epiWAT (epididymal white adipose tissue) of WT mice at 6 h after leptin injection (Fig. 1a). Leptin also increased the rate constant of 2DG uptake in heart muscle and BAT but not in epididymal WAT of WT mice. In contrast, leptin did not increase 2DG uptake in any of these peripheral tissues of β-less mice (Fig. 1a). Consistent with the previous reports3,4,7,8,31,32, plasma glucose and insulin concentrations were not affected by leptin injection into the VMH of WT or β-less mice (Fig. 1b,c). Injection of leptin into the VMH significantly increased NE turnover in soleus muscle but not in Gastro-W of WT mice (Fig. 1d). Norepinephrine (NE) turnover was measured on the basis of the decline in tissue NE content after the inhibition of catecholamine biosynthesis with α-methyl-p-tyrosine (α-MT) to evaluate sympathetic nerve activity of individual tissue in the same animals33. The results suggest that leptin increases the activity of sympathetic nerves innervating red-type but not white-type skeletal muscle. Thus leptin injection into the VMH increases glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle preferentially through activation of sympathetic nerves and β-AR in the tissue.

Figure 1.

Leptin injection into the VMH increases 2DG uptake in certain peripheral tissues of WT mice but not in those of β-less mice. (a) Rate constant of 2DG uptake in peripheral tissues of WT and β-less mice measured 6 h after injection of saline or leptin into the VMH (n = 6). Gastro-R: red portion of gastrocnemius, Gastro-W: white portion of gastrocnemius, EDL: extensor digitorum longus, BAT: brown adipose tissue, epiWAT: epididymal white adipose tissue. (b,c) Plasma glucose (b) and insulin (c) concentrations in WT and β-less mice at 6 h after injection of leptin into the VMH (n = 6). (d) NE turnover in soleus and Gastro-W muscles of WT mice measured 6 h after saline or leptin injection into the VMH (n = 6 or 7) (unpaired Student’s t test). α-MT: α-methyl-p-tyrosine. All data are means ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for saline injection into WT mice; † P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for leptin injection into WT mice (one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple-range test).

Effects of leptin on insulin signalling and AMPK activity in soleus of WT and β-less mice

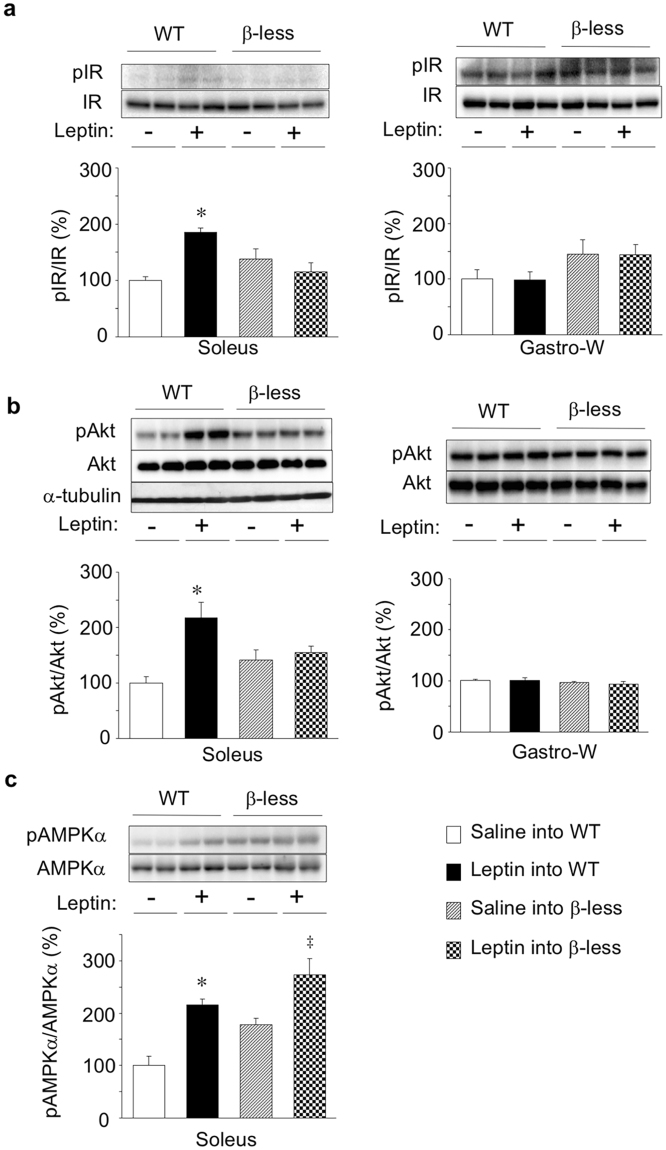

To elucidate the mechanism by which leptin increases glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle, we examined the effect of leptin injection into the VMH on insulin signalling in skeletal muscle. Injection of leptin into the VMH increased the amounts of phosphorylated forms of IR and Akt in soleus muscle but not in Gastro-W of WT mice (Fig. 2a,b). In contrast, leptin did not increase the abundance of phosphorylated IR or Akt in soleus or Gastro-W of β-less mice (Fig. 2a,b). The extents of Akt as well as α-tubulin were not different among groups (Fig. 2b). Leptin thus enhanced insulin signalling in red-type skeletal muscle in a β-AR-dependent manner, similar to its effect on glucose uptake in such muscle.

Figure 2.

Effects of leptin on insulin signalling and AMPK activity in soleus muscle of WT and β-less mice. Representative immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated (p) and total forms of IR (a), Akt (b), and the α subunit of AMPK (c) in soleus or Gastro-W at 6 h after injection of saline (−) or leptin (+) into the VMH of WT or β-less mice is shown together with quantitation of the corresponding pIR/IR, pAkt/Akt, and pAMPKα/AMPKα ratios. Representative data were shown in duplicate. Representative immunoblots for α-tubulin were also shown in. (b) Quantitative data are expressed as a percentage of the corresponding value for injection of saline into WT mice and are means ± S.E.M. (n = 4). *P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for saline injection into WT mice; ‡ P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for saline injection into β-less mice (one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple-range test).

AMPK is activated by phosphorylation at Thr172 of its α subunit by AMPK kinases such as LKB1 and Ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK)34,35. Leptin induces AMPK phosphorylation in red-type skeletal muscle including soleus5. We found that injection of leptin into the VMH increased the extent of AMPKα phosphorylation but not AMPKα in soleus muscle of both WT and β-less mice (Fig. 2c), suggesting that AMPK activation in red-type skeletal muscle is not sufficient for leptin-induced glucose uptake or enhancement of insulin signalling in this tissue as well as that leptin activates AMPK in skeletal muscle through a β-AR–independent mechanism.

Leptin increases muscle glucose uptake via β2-AR in muscle

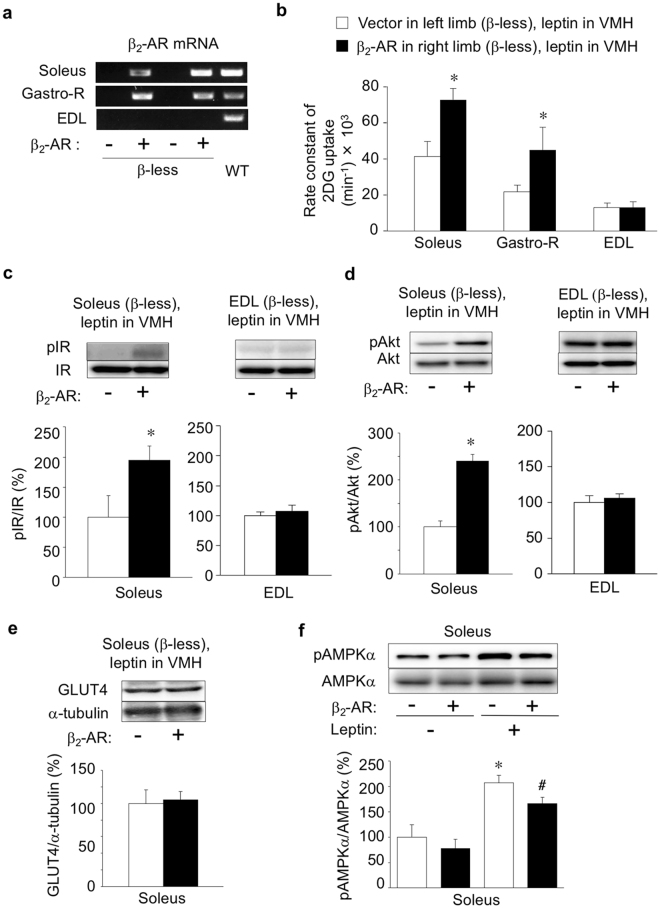

The β2-AR is the major β-AR isoform in skeletal muscle of rodents and humans26,27. To examine the role of β2-AR in the leptin-induced increase in glucose uptake and enhancement of insulin signalling in red-type skeletal muscle, we restored expression of β2-AR in soleus and Gastro-R muscles in the right hind limb of β-less mice by in vivo electroporation with an expression construct controlled by the CAG promoter. The abundance of β2-AR mRNA in the right soleus and Gastro-R muscles of β-less mice at 8 days after electroporation was similar to that in the corresponding muscles of WT mice (Fig. 3a). The amount of β2-AR mRNA was not similarly increased in EDL muscle of the right hind limb in the electroporated mice. Injection of leptin into the VMH increased the rate constant of 2DG uptake in the right soleus and Gastro-R, but not in the right EDL, of the electroporated β-less mice, compared with that apparent for the contralateral muscles not expressing β2-AR (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, central leptin injection increased the amounts of phosphorylated IR and Akt in the β2-AR–expressing right soleus but not in the β2-AR–deficient right EDL muscle (Fig. 3c,d). The amount of GLUT4 protein did not change in the β2-AR–expressing soleus muscle compared with that in β2-AR–deficient muscle (Fig. 3e). In contrast, leptin increased the level of AMPK phosphorylation in both the β2-AR–expressing right soleus and the β2-AR–deficient left soleus of β-less mice (Fig. 3f). These results thus suggested that leptin-induced glucose uptake and enhancement of insulin signalling in red-type skeletal muscle are mediated by muscle β2-AR, whereas leptin-induced AMPK activation is not.

Figure 3.

Forced expression of β2-AR in red-type skeletal muscle of β-less mice restores leptin-induced glucose uptake. (a) RT-PCR analysis of β2-AR mRNA in soleus, Gastro-R, and EDL muscles of β-less mice at 8 days after in vivo electroporation with an expression vector for β2-AR in the soleus and Gastro-R of the right hind limb (+) as well as with the corresponding empty vector in the same muscles of the left hind limb (−). Representative data for two manipulated β-less mice and one intact WT mouse are shown. (b) Rate constant of 2DG uptake in soleus, Gastro-R, and EDL muscles of the left (−) and right (+) hind limbs of β-less mice (n = 5) measured at 8 days after in vivo electroporation as in (a) and at 6 h after leptin injection into the VMH. (c,d) Representative immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated (p) and total forms of IR (c) and Akt (d) in soleus and EDL muscles of the (−) and (+) hind limbs of β-less mice treated as in (b) is shown together with quantitation of the corresponding pIR/IR and pAkt/Akt ratios (n = 4). (e) Representative immunoblot analysis and quantitation (n = 4) of GLUT4 and α-tubulin in soleus muscle of the (−) and (+) hind limbs of β-less mice treated as in (b). *P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for the β2-AR(−) muscle in the left hind limb (paired Student’s t test). (f) Representative immunoblot analysis and quantitation (n = 4) of phosphorylated (pAMPKα) and total (AMPKα1 and AMPKα2) forms of the α1 and α2 subunits of AMPK in soleus muscle of the (−) and (+) hind limbs of β-less mice measured at 8 days after in vivo electroporation as in (a) and at 6 h after leptin (+) or saline (−) injection into the VMH. *P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for the β2-AR(−) muscle after saline injection; # P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for the β2-AR(+) muscle after saline injection. All quantitative data are means ± S.E.M.

Leptin increases glucose uptake and enhances insulin signalling in skeletal muscle in an AMPK-independent manner

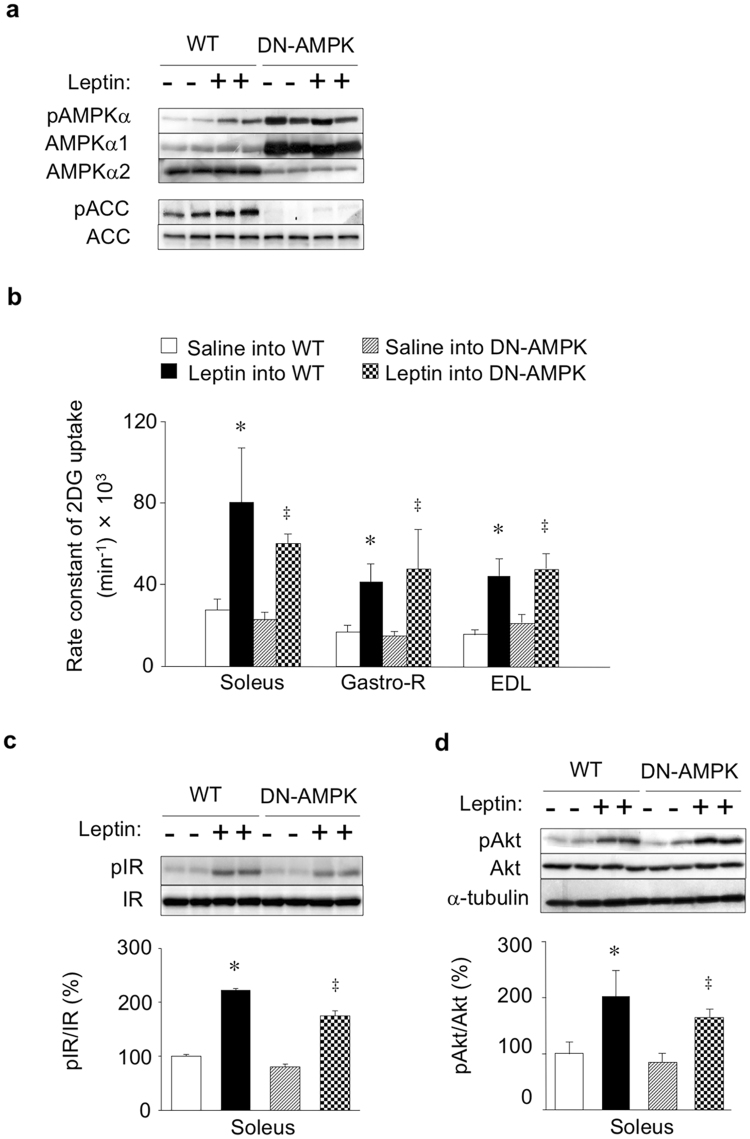

Finally, we examined the effect of suppression of AMPK activity in skeletal muscle on leptin-induced glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle with the use of DN-AMPK transgenic mice, which express a dominant negative form of the α1 subunit of AMPK in skeletal muscle29. Consistent with previous observations29, the soleus muscle of DN-AMPK mice manifested marked increases in both the amount of the α1 subunit of AMPK and the level of α subunit phosphorylation (at Thr172) as well as a decrease in the abundance of the α2 subunit (Fig. 4a), with the latter effect thought to be the result of degradation of the α2 subunit excluded from the heterotrimeric complex of AMPK29. Leptin injection into the VMH increased the level of Ser79-phosphorylation of the AMPK substrate ACC in soleus muscle of WT mice but not in that of DN-AMPK mice (Fig. 4a). Expression of DN-AMPK in skeletal muscle was previously shown to suppress signalling downstream of AMPK29,36. Nevertheless, leptin injection into the VMH increased the rate constant of 2DG uptake in soleus, Gastro-R, and EDL muscles of DN-AMPK mice to an extent similar to that apparent in WT mice (Fig. 4b). The leptin-induced increases in the extents of IR and Akt phosphorylation as well as total Akt protein in soleus muscle were also similar in DN-AMPK and WT mice (Fig. 4c,d). These results thus suggested that activation of AMPK in skeletal muscle is not necessary for leptin-induced glucose uptake and enhancement of insulin signalling in this tissue.

Figure 4.

Leptin increases glucose uptake and enhances insulin signalling in skeletal muscle of DN-AMPK mice. (a) Representative immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated (pAMPKα) and total (AMPKα1 and AMPKα2) forms of the α1 and α2 subunits of AMPK as well as of phosphorylated and total ACC in soleus muscle of WT and DN-AMPK mice at 6 h after injection of saline (−) or leptin (+) into the VMH. (b) Rate constant of 2DG uptake in soleus, Gastro-R, and EDL muscles at 6 h after injection of saline or leptin into the VMH of WT or DN-AMPK mice (n = 5). (c, d) Representative immunoblot analysis and quantitation (n = 4) of pIR/IR (c) and pAkt/Akt (d) in soleus muscle of WT or DN-AMPK mice at 6 h after injection of saline (−) or leptin (+) into the VMH. Representative immunoblots for α-tubulin were also shown in. (d) All quantitative data are means ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for saline injection in WT mice. ‡ P < 0.05 versus corresponding value for saline injection in DN-AMPK mice (one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple-range test).

Discussion

We have here shown that leptin injection into the VMH increases glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle through activation of sympathetic nerves and β2-AR in the muscle tissue. This effect of leptin was thus not apparent in β-less mice, whereas forced expression of β2-AR in red-type skeletal muscle of these mice restored both the leptin-induced increase in glucose uptake and enhancement of insulin signalling. We also found that leptin activates sympathetic nerves innervating red-type but not white-type skeletal muscle. These results suggest that leptin-induced glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle is mediated by the activation of sympathetic nerves and β2-AR in the muscle tissue.

We previously showed that injection of orexin into the VMH of mice activates VMH neurons and promotes insulin-induced glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle including soleus and Gastro-R via activation of sympathetic nerves and β2-AR in muscle tissue30. This effect of orexin was thus not apparent in β-less mice, whereas forced expression of β2-AR under the control of the CAG promoter in both red-type myocytes and nonmyocytes including blood vessel cells in these mice restored the effect. Activation of β2-AR in blood vessels stimulates vascular relaxation37 and thereby increases insulin delivery to myocytes38, which plays a key role in muscle glucose disposal39. In the present study, forced expression of β2-AR in red-type skeletal muscle of β-less mice restored phosphorylation of IR and Akt in the muscle tissue in response to leptin administration into the VMH. Thus such leptin injection may stimulate glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle via enhancement of insulin signalling in a manner dependent on β2-AR–induced vasodilation in the muscle vasculature and a consequent increase in insulin delivery to myocytes. Indeed, we previously showed that leptin-induced muscle glucose uptake is blunted by the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME [N:(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester]40. It is also possible, however, that humoral factors might contribute to the action of leptin through cooperative activation of insulin or other signalling pathways in skeletal muscle.

Leptin may partly increase glucose uptake in skeletal muscle by β2-AR expressed in myocytes and through an insulin-independent mechanism. We previously showed that forced expression of β2-AR under the control of the myocyte-specific promoter HSA (human α-skeletal actin) partly rescued the orexin-induced glucose uptake in soleus and Gastro-R muscles in β-less mice in an insulin-independent manner30. HSA promoter expressed β2-AR in the red-type muscles, similar to the level in muscle expressed β2-AR by CAG promoter. Orexin injection into the VMH increased glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscles without change in phosphorylation of IR. However, the orexin-induced glucose uptake in muscles expressed β2-AR in myocytes was significantly smaller than that in muscles expressed β2-AR by CAG promoter30. Furthermore, the leptin-induced muscle glucose uptake was abolished by L-NAME40. Thus, although β2-AR in myocytes might be involved in the leptin-induced glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle, β2-AR in nonmyocytes, including blood vessels, plays an important role in the leptin-induced activation of insulin signalling including IR-Akt and glucose uptake in red-type of skeletal muscle in vivo. Further investigation is necessary to clarify the role of β2-AR in myocytes and blood vessels in leptin-induced glucose uptake in the muscle tissue.

It is possible that the β1-AR in red-type skeletal muscles might also regulate the leptin-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle of WT mice, despite its low expression red-type skeletal muscle tissue30 compared to β1-AR expression in heart muscle and BAT and β2-AR in skeletal muscle. Further investigation to examine the effect of β1-AR on glucose uptake in the muscle would be needed. Nevertheless, the present results showed that expression of β2-AR sufficiently rescues the leptin-induced glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle in β-less mice without expression of β1 and β3-AR in the skeletal muscle tissue.

Previous reports showed that AMPK activation is sufficient but not required for exercise- or muscle contraction–induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle17,18. Consistent with the studies, AMPK was unlikely to be a primary mediator of leptin-induced glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle. However, β2-AR may regulate phosphorylation of AMPK in soleus muscle. pAMPK/AMPK ratio in soleus muscle of β-less mice tended to increase in the absence and presence of leptin injection into the VMH, compared with that in WT mice. Forced expression of β2-AR tended to decrease the leptin-induced phosphorylation of AMPK in the tissue. β2-AR thus appears to inhibit AMPK activity in soleus muscle. It is possible that change in AMPK activity in β-less mice modulates insulin signalling and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle in the mice. Further investigation is necessary to elucidate the role of AMPK in insulin signalling and glucose uptake in peripheral tissues in β-less mice.

Collectively, our results suggest that leptin requires sympathetic nerve activation and β2-AR stimulation in muscle tissue to increase glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle. In contrast, AMPK activation is not required for this effect of leptin. Leptin is effective for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in humans and animals with lipodystrophy9,10, and it ameliorates streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes in rodents11. Our findings provide a fuller understanding of the mechanism by which leptin stimulates glucose uptake in peripheral tissues and therefore offer new insight into regulation of glucose metabolism by the central nervous system and its potential for therapeutic manipulation.

Materials and Methods

Animals and surgery

Male β-less mice28 and skeletal muscle–specific DN-AMPK transgenic mice29, as well as their wild-type (WT) counterparts, were studied at 12 to 18 weeks of age. The DN-AMPK transgenic mice express a dominant negative form of rat AMPK α1 subunit with an Asp157-to-Ala mutation) in skeletal muscle under the control of the skeletal muscle–specific promoter of the human skeletal actin gene. All animals were housed individually in plastic cages at 24° ± 1 °C with lights on from 0600 to 1800 hours and with free access to a laboratory diet (MF; Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan) and water. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (Okazaki, Japan), and they were performed according to institutional guidelines concerning the care and handling of experimental animals.

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) for unilateral implantation of a chronic stainless steel cannula (Unique Medical, Osaka, Japan) into the VMH according to the stereotaxic coordinates AP 1.5 (1.5 mm anterior to the bregma), L 0.3 (0.3 mm lateral to the bregma), and H 5.8 (5.8 mm below the bregma) for the cannula tip. Leptin (50 pmol) (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) dissolved in 0.2 μl of physiological saline or saline alone as a control was injected via the cannula into the VMH of conscious, unrestrained mice with the use of a Hamilton microsyringe. A silicone catheter was implanted into the right atrium through the external jugular vein as described previously30. Animals were handled repeatedly during the recovery period (~2 weeks) after cannula implantation to habituate them to the injection and blood sampling procedures. All animal experiments were performed 6 h after saline or leptin injection into the VMH during the light period. Food, but not water, was removed immediately after injection of leptin or saline into the VMH.

Measurement of glucose uptake

For measurement of glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, a mixture of 6.25 μCi of 2-deoxy-D-[3H]glucose (2DG) (10 Ci/mmol) and 1.25 μCi of [14C]sucrose (10 Ci/mmol) (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 50 μl of saline was injected through the jugular vein catheter 6 h after microinjection of leptin or saline into the VMH. Blood was collected for isolation of plasma immediately before the injection of leptin as well as 0, 10, 15, and 20 min after injection of the radioactive tracers. Immediately after collection of the final blood sample, an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) was injected through the jugular vein catheter and the animal was rapidly decapitated. The soleus, red portion of the gastrocnemius (Gastro-R), white portion of the gastrocnemius (Gastro-W), and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle as well as epididymal WAT, heart muscle, and interscapular BAT were rapidly dissected and weighed. The tissue samples were homogenized at 4 °C, the homogenates were centrifuged at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants as well as plasma samples were assayed for radioactivity. The rate constant (Ki) of 2DG uptake in peripheral tissues was calculated using the following equation (1), as described previously41–43.

| 1 |

where Ci is the intracellular concentration of 2- [3H]DG [disintegrations per min (dpm) per mg tissue (µl)] at death, Kp is the rate constant of plasma disappearance of 2-[3H]DG, CpO is the extrapolated plasma 2- [3H]DG concentration at time 0 (dpm per μl), and t is the duration of the test, i.e., 20 min. Kp is the slope at time 0 provided by a linear regression analysis. C was calculated from the radioactivities of 3H and 14C in the plasma and tissues as reported previously42,43.

Immunoblot analysis

Tissue was homogenized at 4 °C in a lysis buffer containing 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and was then subjected to immunoblot analysis as described previously30. For analysis of the Tyr1146-phosphorylated form of the β subunit of IR, the homogenates were centrifuged at 4 °C and the resulting supernatants (300 µg protein) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to IR (Cell Signalling Technology, Danvers, MA) and protein G–Sepharose (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The immunoprecipitates were isolated by centrifugation, washed with 0.1% Nonidet P-40 in phosphate-buffered saline, and half amounts of the immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for immunoblot analysis. Separated proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, which was then exposed to 5% dried skim milk in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) before incubation for 16 h at 4 °C in TBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin and primary antibodies (1 μg/ml). For other immunoblots, tissue lysates (20 µg protein) were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Primary antibodies included those to the Tyr1146-phosphorylated β subunit of IR, to Ser473-phosphorylated Akt, to the Thr172-phosphorylated form of the α subunit of AMPK, to Ser79-phosphorylated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and to total forms of these various proteins and α-tubulin (Cell Signalling Technology). Immune complexes were detected with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham). The amounts of phosphorylated forms of the examined proteins were determined by densitometric scanning of immunoblots and were normalized by the corresponding amount of total protein as described previously30. All immunoblots for quantification are shown in Supplementary Information.

Norepinephrine turnover

Norepinephrine (NE) turnover was measured on the basis of the decline in tissue NE content after the inhibition of catecholamine biosynthesis with α-MT as described previously33. α-MT (200 mg/kg) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was injected intraperitoneally at 6 h after leptin or saline injection into the VMH. At 0 or 2 h after α-MT injection, mice were decapitated and muscle tissue was rapidly removed and weighed. The tissue samples were then homogenized in 0.2 M perchloric acid containing 0.1 mM EDTA, and the homogenates were centrifuged at 4 °C. The NE content of the resulting supernatants was assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography (EP-300 system; Eicom, Kyoto, Japan) with a reversed-phase column (CA-5ODS, Eicom) and electrochemical detector (ECD-300, Eicom). Data are expressed as picograms of NE per milligram of tissue weight.

Forced expression of β2-AR in skeletal muscle of β-less mice

The β2-AR was forcibly expressed in soleus and Gastro-R muscles of the right hind limb of β-less mice as described previously30. The mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), and an ~1-cm incision was made in the skin around the lateral region of the gastrocnemius. The right soleus and gastrocnemius were exposed, and 20 μg of a pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) vector encoding mouse β2-AR under the control of the CAG promoter44 (provided by M. Morimatsu, Iwate University, Japan) were applied around the surface of the soleus and Gastro-R with the use of a microsyringe. Electric pulses were then administered six times at 70 V (loading period of 50 ms per pulse) from outside of the gastrocnemius with the use of an electroporator (CUY12; NEPA Gene, Ichikawa, Japan) and a pincette-type electrode (CUY650P, NEPA Gene). The left soleus and gastrocnemius muscles were subjected to the same electroporation procedure with the corresponding empty vector. The EDL of both hind limbs remained intact. The hind limb muscles were continuously cooled with ice during electroporation. Analysis of β2-AR expression in soleus, Gastro-R, and EDL muscles was performed 8 days after electroporation.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from muscle samples with the use of Isogen (Nippon Gene, Wako, Japan). Portions of the RNA were subjected to reverse transcription (RT) with an oligo(dT) primer and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Takara, Otsu, Japan), and the resulting cDNA was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis with LA Taq (Takara) and primers (forward, 5′-CGAGTGGTCATCCTGATG-3′; reverse, 5′-GCAGAACTTGGAGGACC-3′) specific for β2-AR (Sigma Genosys, Ishikari, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. and were evaluated by the unpaired or paired Student’s t test or by analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple-range test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank B.B. Lowell and E.S. Bachman for providing β-less mice, M. Morimatsu for providing the CAG promoter, N. Kawai and M. Hayashi for laboratory management, and the Centre for Radioisotope Facilities at the National Institute for Basic Biology for technical support. This work was supported by a grant from Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJPR13MG to T.S.); by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (19790653 to T.S.), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (16390062, 19390059, 21390067, and 24390058 to Y.M.), Grants-in-Aid for Exploratory Research (17659069 and 15K15352 to Y.M.), and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (22126005 to Y.M.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; and by the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology Program (CREST-AMED) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (to Y.M.).

Author Contributions

T.S. performed animal experiments as well as immunoblot, RT-PCR, and statistical analyses. C.T., S.O., and E.A.C. contributed to design of the study. K.S. participated in blood collection from and maintenance of mice. S.M. and O.E. established DN-AMPK mice. Y.M. and T.S. designed the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15548-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Myers MG, Cowley MA, Münzberg H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:537–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton GJ, Schwartz MW. Leptin and the central nervous system control of glucose metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:389–411. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamohara S, Burcelin R, Halaas JL, Friedman JM, Charron MJ. Acute stimulation of glucose metabolism in mice by leptin treatment. Nature. 1997;389:374–377. doi: 10.1038/38717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minokoshi Y, Haque MS, Shimazu T. Microinjection of leptin into the ventromedial hypothalamus increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues in rats. Diabetes. 1999;48:287–291. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haque MS, et al. Role of the sympathetic nervous system and insulin in enhancing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues after intrahypothalamic injection of leptin in rats. Diabetes. 1999;48:1706–1712. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minokoshi Y, et al. Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2002;415:339–343. doi: 10.1038/415339a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toda C, et al. Distinct effects of leptin and a melanocortin receptor agonist injected into medial hypothalamic nuclei on glucose uptake in peripheral tissues. Diabetes. 2009;58:2757–2765. doi: 10.2337/db09-0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toda C, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the ventromedial hypothalamus mediates leptin-induced glucose uptake in red-type skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2013;62:2295–2307. doi: 10.2337/db12-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Ikemoto S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in mice with congenital lipodystrophy. Nature. 1999;401:73–76. doi: 10.1038/43448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebihara K, Masuzaki H, Nakao K. Long-term leptin-replacement therapy for lipoatrophic diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:615–616. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408053510623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujikawa T, Chuang JC, Sakata I, Ramadori G, Coppari R. Leptin therapy improves insulin-deficient type 1 diabetes by CNS-dependent mechanisms in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17391–17396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008025107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn BB, Flier JS. Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2010;106:473–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhillon H, et al. Leptin directly activates SF1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;49:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujikawa T, et al. SF-1 expression in the hypothalamus is required for beneficial metabolic effects of exercise. Elife. 2016;5:e18206. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coutinho EA, et al. Activation of SF1 neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus by DREADD technology increases insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. Diabetes. 2017;66:2372–2386. doi: 10.2337/db16-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miura S, Kai Y, Kamei Y, Ezaki O. Isoform-specific increases in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) mRNA in response to beta2-adrenergic receptor activation and exercise. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4527–4533. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nevzorova J, Evans BA, Bengtsson T, Summers RJ. Multiple signalling pathways involved in b2-adrenoceptor-mediated glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:446–454. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato M, et al. Improving type 2 diabetes through a distinct adrenergic signaling pathway involving mTORC2 that mediates glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2014;63:4115–4129. doi: 10.2337/db13-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee AD, et al. Effects of epinephrine on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and GLUT-4 phosphorylation in muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1082–C1087. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.3.C1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt DG, Ding Z, Ivy JL. Propranolol prevents epinephrine from limiting insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake during contraction. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:697–704. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00017.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long YC, Zierath JR. Influence of AMP-activated protein kinase and calcineurin on metabolic networks in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrin Metab. 2008;295:E545–E552. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90259.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mu J, et al. A role for AMP-activated protein kinase in contraction- and hypoxia-regulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fryer LG, et al. Characterization of the role of the AMP-activated protein kinase in the stimulation of glucose transport in skeletal muscle cells. Biochem J. 2002;363:167–174. doi: 10.1042/bj3630167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakoda H, et al. Activation of AMPK is essential for AICAR-induced glucose uptake by skeletal muscle but not adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrin Metab. 2002;282:E1239–E1244. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00455.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viollet B, et al. The AMP-activated protein kinase α2 catalytic subunit controls whole-body insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:91–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI16567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagström-Toft E, Enoksson S, Moberg E, Bolinder J, Arner P. β-Adrenergic regulation of lipolysis and blood flow in human skeletal muscle in vivo. Am J Physiology. 1998;275:E909–E916. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.6.E909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts SJ, Papaioannou M, Evans BA, Summers RJ. Characterization of β-adrenoceptor mediated smooth muscle relaxation and the detection of mRNA for β1-, β2- and β3-adrenoceptors in rat ileum. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:949–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bachman ES, et al. βAR signalling required for diet-induced thermogenesis and obesity resistance. Science. 2002;297:843–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1073160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miura S, et al. α2-AMPK activity is not essential for an increase in fatty acid oxidation during low-intensity exercise. Am J Physiol-Endocrin Metab. 2009;296:E47–E55. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90690.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiuchi T, et al. Hypothalamic orexin stimulates feeding-associated glucose utilization in skeletal muscle via sympathetic nervous system. Cell Metab. 2009;10:466–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunbar JC, Yuange Hu,Y, Huiqing Lu,H. Intracerebroventricular leptin increases lumbar and renal sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in normal rats. Diabetes. 1997;46:2040–2043. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.12.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muzumdar R, et al. Physiologic effect of leptin on insulin secretion is mediated mainly through central mechanisms. FASEB J. 2003;17:1130–1132. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0991fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saito M, Minokoshi Y, Shimazu T. Accelerated norepinephrine turnover in peripheral tissues after ventromedial hypothalamic stimulation in rats. Brain Res. 1989;481:298–303. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90806-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardie DG, Hawley SA, Scott JW. AMP-activated protein kinase—development of the energy sensor concept. J Physiol. 2006;574:7–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tadaishi M, et al. Effect of exercise intensity and AICAR on isoform-specific expressions of murine skeletal muscle PGC-1α mRNA: a role of β2-adrenergic receptor activation. Am J Physiol – Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E341–E349. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00400.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guimarães S, Moura D. Vascular adrenoceptors: an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:319–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu JD, et al. Direct administration of insulin into skeletal muscle reveals that the transport of insulin across the capillary endothelium limits the time course of insulin to activate glucose disposal. Diabetes. 2008;57:828–835. doi: 10.2337/db07-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asensio C, Jimenez M, Kühne F, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Muzzin P. The lack of β-adrenoceptors results in enhanced insulin sensitivity in mice exhibiting increased adiposity and glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 2005;54:3490–3495. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiuchi T, et al. Involvement of bradykinin and nitric oxide in leptin-mediated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Endocrinology. 2001;142:608–612. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.2.7964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sokoloff L, et al. The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem. 1977;28:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hom FG, Goodner CJ, Berrie MAA. [3H]2-deoxyglucose method for comparing rates of glucose metabolism and insulin responses among rat tissues in vivo. Validation of the model and the absence of an insulin effect on brain. Diabetes. 1984;33:141–152. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudo M, Minokoshi Y, Shimazu T. Ventromedial hypothalamic stimulation enhances peripheral glucose uptake in anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:E298–E303. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.3.E298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.