Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the risk factors of hypertension in middle-aged people within the Tujia-Nationality settlement in China. Demographics questionnaires and fitness tests were performed to identify the risk factors of hypertension in middle-aged people in the years 2005, 2010 and 2014 in the area of southwest Hubei of China. Of the 2428 participants, 568 were classified as hypertensive, giving an overall occurrence of hypertension at 23.4%, and the prevalence of hypertension was the highest in the year 2014 (34.9%). Furthermore, Tujia minority had a significantly higher risk for having hypertension (odds ratio=1.055 with 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.039–1.072; P=0.001) than Han people. Individuals with the lowest level of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) had a 2.483-fold risk for hypertension (95% CI, 1.530–4.031; P=0.001). Obesity and overweight individuals increased the risk by 3.470-fold and 2.124-fold, respectively, for having hypertension compared to normal weight people. Finally, white-collar workers had a 58.1 and 31.8% higher risk for hypertension than blue-collar workers in rural and urban areas, respectively. These results demonstrated that the prevalence of hypertension was higher between 2011 and 2014 in the area. The main risk factors for developing hypertension were found to be sex (as woman), Tujia minority, white-collar workers, overweight-obese, those with a middle school education, and those with the lowest CRF.

Introduction

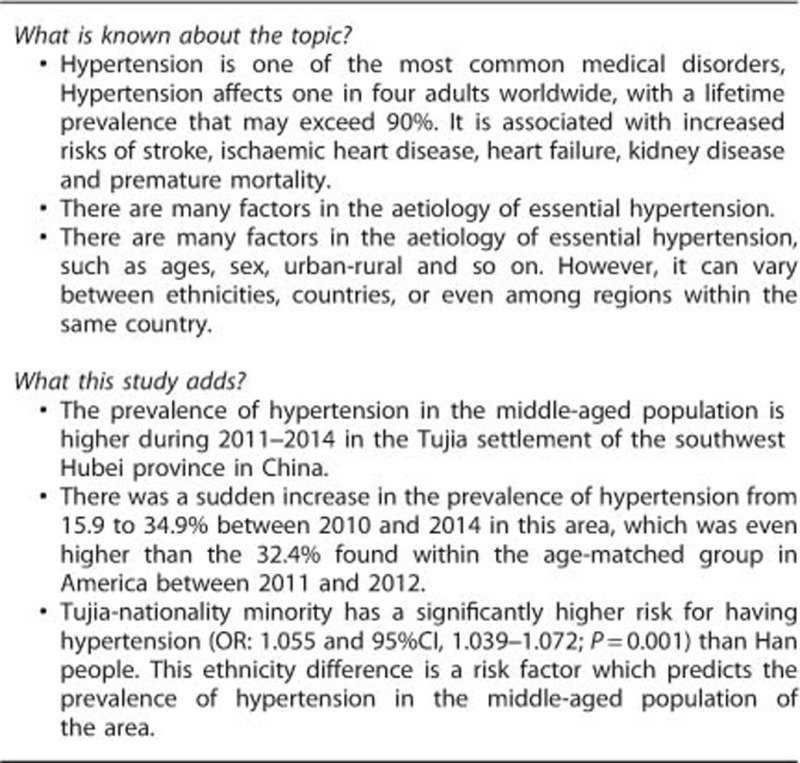

Hypertension is one of the most common medical disorders, affecting one in four adults worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence that may exceed 90%.1 Hypertension is associated with increased risks of stroke, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, kidney disease and premature mortality.2 There are many factors in the aetiology of essential hypertension, but it can vary between ethnicities,3 countries4 or even among regions within the same country.5

The Tujia-Nationality settlement in the southwest Hubei province in China is the most poverty stricken area in the Hubei province; however, utilization of the highway and railway systems during the past 5 years has rapidly improved the economy of the area. Middle-aged people encounter intense pressure regarding any changes in the economy, which is a main factor of many chronic diseases.6 However, to our knowledge, few studies focus on the changes of chronic diseases in this area, particularly hypertension. This study examined arterial blood pressure and cardiopulmonary fitness of the middle-aged people in the years 2005, 2010 and 2014 to identify the prevalence of hypertension and its distribution, as well as the risk factors within the Tujia-Nationality settlement area.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study consisted of three cross-sectional surveys in the years 2005, 2010 and 2014, which was initiated and sponsored by the All-China Sports Federation and the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China, and supported and approved by the local government and the University for Nationalities in Enshi, Hubei province. This study was designed to investigate the risk factors of hypertension in the southwest Hubei province of China. A total of 2428 middle-aged 45–59 years old men and women (n=633 in 2005, n=844 in 2010 and n=951 in 2014) who voluntarily provided the informed consent participated in this study. All participants were recruited from the same Tujia settlement area in Hubei province of China.

Methods

The tests were comprised of two parts: a demographics questionnaire and a fitness test. Questionnaires inquired about age, nationality, gender, urban versus rural location, employment classification and highest level of completed education. Fitness testing included measurements for blood pressure, height, weight, vital lung capacity, sidestep test, standing vertical jump, sit-and-reach, grip strength, single leg stance test, reaction time, push-ups (men) and sit-ups (women).

The subjects performed all the tests in a gymnasium between July and August in the years 2005, 2010 and 2014. The study subjects first completed a questionnaire. Then following a 20-min rest, trained physicians measured their blood pressure using a mercury sphygmomanometer. The measurements were made in triplicate within 10-min interval with the subjects in the seated position. Arterial hypertension was determined or diagnosed by the blood pressure measured, that, systolic blood pressure ⩾140 mmHg and/or diastolic ⩾90 mmHg, or current treatment with antihypertensive drugs.

The cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) was tested using the sidestep test (TDK-2 intelligent apparatus, Ningbo Jingbei Tiandikuan Electronic Product Manufacturer). Man subjects used a 40 cm-high footstep and woman subjects used a 35 cm-high footstep to perform the up-and-down movement. Every subject performed up-and-down movements for about 3 min (90 repetitions) in rhythm to music. After the subject sat down, a finger clip was placed on the subject’s middle finger from which pulse rate was displayed on the screen and recorded. Pulse rate readings were taken three separate times after the completion of the sidestep exercise: between 1 min to 1 min 30 s; 2 min to 2 min 30 s; and 3 min 30 s. The sidestep test index was calculated from the duration of up-and-down movements (in seconds) multiplied by 100 divided by the sum of three pulse rate readings. Table 1 shows the classification criteria of the index as CRF according to the Citizen Physical Health Standard established by Ministry of Education of China and the General Administration of Sport of China.7

Table 1. Classification criteria of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF).

| Age (Year) |

Lowest |

Low |

High |

Highest |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| 45–49 | ⩽45.6 | ⩽46.3 | >45.6, ⩽61.5 | >46.3, ⩽60.3 | >61.5, ⩽71.3 | >60.4, ⩽70.2 | >71.3 | >70.2 |

| 50–54 | ⩽43.8 | ⩽45.8 | >43.8, ⩽61.5 | >45.8, ⩽59.9 | >61.5, ⩽71.3 | >59.9, ⩽69.7 | >71.3 | >69.7 |

| 55–59 | ⩽39.8 | ⩽44.7 | >39.8, ⩽60.3 | >44.7, ⩽59.9 | >60.3, ⩽70.2 | >59.9, ⩽69.7 | >70.2 | >69.7 |

Next, we measured the subjects’ height, weight, vital lung capacity, standing vertical jump, sit-and-reach, grip strength, single leg stance test, reaction time, push-ups (for men) and sit-ups (for women). All of the testing apparatuses were made by the Shenzheng Hengkang Jiaye Limited Company, China. When the subjects were ready, the testers pressed the button to initiate the beginning of the test.

All physical fitness measurements and scoring criteria were classified according to the Citizen Physical Health Standard established by Ministry of Education of China and the General Administration of Sport of China.7 Each category we measured had an acceptable value range; if the total of these results fell within this range they were labelled as ‘pass,’ while those that did not were labelled as ‘fail’.7

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight (in kilograms)/height2 (in meter). The BMI was classified into four levels: 18.5 as underweight, 18.5-24.9 as normal weight, 25.0-29.9 as overweight and ⩾30.0 as obese.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SPSS for Windows software package (version 18; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were obtained first; categorical variables were presented as the number of people (%). Collinearity diagnostics were performed prior to further statistical analysis. A binary unconditional logistic regression model was used to analyse the independent effects of each variable. Potential risk factors included testing time, ages, nationality, gender, urban versus rural location, employment classification, education level, BMI, CRF and physical test scores. The dependent factor was ‘Whether the subject is hypertensive’. Retained methods used a forward step-by-step approach. All variables significant at P<0.05 were reserved in the final model.

Results

Prevalence and distribution of hypertension

Of the 2428 participants, 568 were classified as hypertensive, giving an overall prevalence of hypertension was 23.4%. The prevalence was lower in 2005 and 2010 at 15.9% and 16.1%, respectively, before doubling to 34.9% by 2014. The prevalence was higher among women (25.9%) than men (20.8%). The prevalence of hypertension was lower in rural residents (17.1%), compared to urban residents (26.7%), see Table 2. In regards to occupation, the prevalence of hypertension was highest among white-collar workers at 30.8%, and lowest among blue-collar workers in rural areas at 17.0% (Table 2). By the level of education completed, the prevalence was highest among participants with a middle school education at 28.4%, followed by those with university or higher education at 26.7%, high school at 21.5% and primary school at 19.3% (Table 2). Hypertension prevalence was associated with BMI. By CRF levels, the prevalence was lowest among participants who had a highest fitness (20.2%), followed by low fitness (22.2%) and high fitness (25.0%); the prevalence was highest among participants with a lowest fitness at 30.4%. The prevalence was higher among people who failed the physical test (28.8%) compared to the ones who passed the test (21.5%).

Table 2. Distribution of hypertension by population characteristics (un-adjusted).

| Variable/Category | Normotension (%) | Hypertension (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test time (year) | |||

| 2005 | 531 (83.9) | 102 (16.1) | 633 |

| 2010 | 710 (84.1) | 134 (15.9) | 844 |

| 2014 | 619 (65.1) | 332 (34.9) | 951 |

| Ages (years) | |||

| 45-49 | 643 (76.0) | 203 (24.0) | 846 |

| 50-54 | 627 (76.9) | 188 (23.1) | 815 |

| 55-59 | 590 (76.9) | 177 (23.1) | 767 |

| Nationality | |||

| Han | 1277 (80.3) | 313 (19.7) | 1590 |

| Tujia | 582 (69.5) | 255 (30.5) | 837 |

| Sex | |||

| Males | 949 (79.2) | 249 (20.8) | 1198 |

| Females | 911 (74.1) | 319 (25.9) | 1230 |

| Urban-rural | |||

| Rural | 689 (82.9) | 142 (17.1) | 831 |

| Urban | 1171 (73.3) | 426 (26.7) | 1597 |

| Employment classification | |||

| Blue-collar workers in rural | 689 (83.0) | 141 (17.0) | 830 |

| Blue-collar workers in urban | 615 (77.4) | 180 (22.6) | 795 |

| White-collar workers | 556 (69.2) | 247 (30.8) | 803 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 570 (80.7) | 136 (19.3) | 706 |

| Middle school | 464 (71.6) | 184 (28.4) | 648 |

| High school | 582 (78.5) | 159 (21.5) | 741 |

| College | 244 (73.3) | 89 (26.7) | 333 |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight | 68 (91.9) | 6 (8.1) | 74 |

| Normal weight | 1287 (82.2) | 278 (17.8) | 1565 |

| Overweight | 461 (65.3) | 245 (34.7) | 706 |

| Obesity | 44 (53.0) | 39 (47.0) | 83 |

| CRF | |||

| Highest | 237 (79.8) | 60 (20.2) | 279 |

| High | 417 (75.0) | 139 (25.0) | 556 |

| Low | 1063 (77.8) | 303 (22.2) | 1366 |

| Lowest | 110 (69.6) | 48 (30.4) | 158 |

| Physical test | |||

| Pass | 1408 (78.5) | 385 (21.5) | 1793 |

| Fail | 452 (71.2) | 183 (28.8) | 635 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness.

Risk factors associated with hypertension in binary logistic regression analysis

Table 3 shows the risk factors for hypertension, which were initially analysed with time stratification. Since the risk factors that predicted the hypertensive prevalence were similar in the logistic regression models, the major predictors were merged together in the discussion for simplicity reason. CRF was inversely related to hypertension. Compared the high level of CRF, people with the lowest level of CRF had a 2.483-fold risk for hypertension (95% CI, 1.530–4.031; P=0.001), and people with low level of CRF had a 1.493-fold risk for hypertension (95% CI, 1.069–2.087; P=0.019), but the highest level of CRF group had no significant difference with the high level of CRF (95% CI, 0.799–1.655; P=0.453); the prevalence of hypertension was the highest in the year 2014 and they were 67.0 and 67.9% more likely for having hypertension than the same age people in 2005 and 2010. Tujia-Nationality people had an increased risk for having hypertension with OR: 1.055, 95% CI, 1.039–1.072 (P=0.001), compared to Han people; middle-age women had a 30.2% higher risk for hypertension (95% CI, 1.054–1. 607; P=0.014) than their man counterparts. By level of education attained, groups with no higher than a middle school education had a 53.5% higher risk for hypertension (95% CI, 1.074–2.194; P=0.019) than the ones who attained college education. White-collar workers had a 58.1% and 31.8% higher risk for hypertension than blue-collar workers in rural and urban areas, respectively. Compared with the normal weight group (BMI between 18.5–25.0 kg m−2), obese group (BMI ⩾30.0 kg m−2) and overweight group (BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 kg m−2) had 3.470-fold and 2.124-fold risk for hypertension, respectively.

Table 3. Risk factors associated with hypertension in binary logistic regression analysis.

| Risk factors | B | s.e. | P-value | OR |

95% CI for OR |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Test time | ||||||

| 2014 | ||||||

| 2005 | −1.107 | 0.139 | 0.001 | 0.330 | 0.252 | 0.434 |

| 2010 | −1.136 | 0.128 | 0.001 | 0.321 | 0.250 | 0.412 |

| Nationality | 0.054 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 1.055 | 1.039 | 1.072 |

| Sex | 0.264 | 0.107 | 0.014 | 1.302 | 1.054 | 1.607 |

| Education | ||||||

| College | ||||||

| Primary school | 0.108 | 0.194 | 0.577 | 1.114 | 0.762 | 1.628 |

| Middle school | 0.428 | 0.182 | 0.019 | 1.535 | 1.074 | 2.194 |

| High school | −0.121 | 0.171 | 0.480 | 0.886 | .634 | 1.239 |

| Employment classification | ||||||

| White-collar workers | ||||||

| Blue-collar workers in rural | −0.870 | 0.148 | 0.001 | 0.419 | 0.314 | 0.559 |

| Blue-collar workers in urban | −0.382 | 0.131 | 0.004 | 0.682 | 0.528 | 0.882 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | ||||||

| Normal weight | ||||||

| Underweight | −0.782 | 0.482 | 0.105 | 0.457 | 0.178 | 1.177 |

| Overweight | 0.753 | 0.111 | 0.001 | 2.124 | 1.710 | 2.639 |

| Obesity | 1.244 | 0.251 | 0.001 | 3.470 | 2.123 | 5.673 |

| CRF | ||||||

| High | ||||||

| Highest | 0.140 | 0.186 | 0.453 | 1.150 | 0.799 | 1.655 |

| Low | 0.401 | 0.171 | 0.019 | 1.493 | 1.069 | 2.087 |

| Lowest | 0.910 | 0.247 | 0.001 | 2.483 | 1.530 | 4.031 |

| Constant | −1.675 | 0.274 | 0.001 | 0.187 | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness.

Discussion

This study indicated that the prevalence of hypertension suddenly increased from 2011 to 2014 in the Tujia settlement in Hubei province of China. For these middle-aged people, the main risk factors for developing hypertension were found to be sex (as woman), Tujia-nationality minority, white-collar workers, the overweight/obese, those with a middle school education and those with the lowest CRF.

We found the prevalence of hypertension suddenly increased from 15.9 to 34.9% between 2010 and 2014 in this area, which was even higher than the 32.4% found within the age-matched group in America between 2011 and 2012.8 It was a special time for this area in 2010–2014, because the highway and railway had their first routes in 2009 and 2010, leading to rapid development of the local economy. However, healthy lifestyles and health education did not progress at the same pace, which led to the chronic disease increase.9

The prevalence of hypertension in middle-aged women was higher, which seemed to be related to a menopause.10 An Italian study11 showed a higher frequency in postmenopausal women (64.1%) as compared with perimenopausal and premenopausal women, independent of age and BMI. Judith et al.12 found the relationship between hypertension in menopausal versus non-menopausal women (70.3% versus 29.0%). In the present study, we found that women had a 30.2% higher risk for hypertension (95% CI, 1.054–1.607; P=0.014) than men, which indicated menopausal women had a higher prevalence of hypertension than men as they entered in the middle age. These findings suggest that sex hormones have a prominent role in preventing hypertension13 for women.

Since the 1980s, work-related stressors have become recognized as important risk factors for having cardiovascular disease and hypertension.14 Workers with lower socioeconomic status (variously defined by education, income or occupation) have been found to have higher age-adjusted mean systolic blood pressure (by 2–3 mmHg) or prevalence of hypertension than employees in higher socioeconomic status groups.15 Other studies found somewhat different results. Landsbergis et al.14 found workers in blue-collar and sales/office jobs had 2–4 mmHg higher systolic blood pressure than workers in management and professional jobs. Our data were consistent with the study of Landsberqis et al.,14 which suggested that white-collar workers had a 58.1% and 31.8% higher risk for hypertension than blue-collar workers in rural and urban areas, respectively. These data indicate a greater work-related stress in white-collar workers.16

Associations between educational status and the development of hypertension have been examined in several studies published over the past decade. The US National Bureau of Economic Research stated that each additional 4 years of education lowered all-cause mortality by almost 1.8% and reduced the risk of heart disease by 2.2%.17 The present study found that the relationship between education and hypertension was a Bell-shaped pattern (Table 3), showing people who attained a middle school education had a 53.5% higher risk for having hypertension (95% CI, 1.074–2.194; P=0.019) than those who attained college education. People who did not surpass primary school generally took part in more physically active jobs, which might cause them to have a lower incidence of coronary heart disease than among those whose jobs required little or no physical activity. On the other hand, the residents who received higher-level educational status such as college and graduate school tended to have more opportunity to access health knowledge and health care, which could lead to low incidences of hypertension.

The worldwide pandemic of overweight and obesity is associated with increased prevalence of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. It has been shown that adipose tissue can elevate circulating aldosterone.18, 19 Over activation of the sympathetic nervous system is a common feature of obesity, which is widely recognized as a major contributor to the development of hypertension.20 Our study confirmed the previous studies1, 21, 22 and indicated that obesity and overweight people had elevated the risk by 3.470-fold and 2.124-fold, respectively, for having hypertension compared to the individuals with normal weight in the area.

CRF provides protective influence against cardiovascular diseases and significantly attenuates the rise in blood pressure over the life span. Thus, the examination of serial changes in CRF as it relates to incidental hypertension is of considerable interest.23 Aerobic exercises may prevent increases in blood pressure through beneficial alterations in insulin sensitivity and autonomic nervous system function.24 Several previous studies have reported the associations between changes in CRF over time and the risk of developing future hypertension.20, 23, 25 Lee et al.25 found that men with lower estimated CRF between initial and follow-up examinations had a higher risk of developing hypertension than men who maintained or improved CRF during the 6-year interim between assessments. Jae et al.23 found the prevalence of hypertension in lower CRF people was 4.33-folder than the highest CRF people. Recently, Xu et al.20 reported that 1-year aerobic exercise training significantly increased peak oxygen uptake and decreased both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in a group of elderly adults. Our results were consistent with these previous studies and further found there was no difference on the risk of hypertension between high levels of CRF. The hypertension prevalence was higher among people who failed the physical test at 28.8% than among the ones who passed the test at 21.5%. However, it was not included as the risk factor in the logistic model, suggesting that the cardiorespiratory function or aerobic capacity was a more important predictor than the physical fitness in preventing hypertension.

Many studies found the prevalence of hypertension was dissimilar among countries and ethnicities.26, 27 In the present study, all of the subjects with different nationalities lived in the same location for many years, though this area is the settlement of Tujia people. Our data suggested that Tujia minority had an increased risk for having hypertension with OR: 1.055 (95% CI, 1.039–1.072, P=0.001) compared to Han people. Future study is needed to determine whether the predisposition to developing hypertension in Tujia minority is influenced by genetic and/or epigenetic factors.28

In the present study, we were unable to find a correlation between hypertension and some other factors that have often been associated with hypertension, such as an urban-rural setting29 and age.30 This indicates that there might be other risk factors for developing hypertension existed in this area.

The main limitation of the present study was that we randomly selected the volunteer subjects who responded to the advertisement, which could not avoid the self-selection bias.

Conclusion

The prevalence of hypertension in the middle-aged individuals was higher during 2011–2014 in the Tujia settlement of the southwest Hubei province in China. The main risk factors for developing hypertension included sex (as women), Tujia-nationality minority, white-collar workers, the overweight/obese, those with a middle school education, and those with the lowest CRF.

Acknowledgments

We thank our volunteer subjects for their cheerful cooperation during the study. Funding for XL was provided by nature science funding from Hubei Provincial Department of Education (Q20131906), China.

Footnotes

The authors declare conflict of interest.

References

- Xu X, Byles J, Shi Z, Mcelduff P, Hall J. Dietary pattern transitions, and the associations with BMI, waist circumference, weight and hypertension in a 7-year follow-up among the older Chinese population: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YX, Dong J, Liu YQ, Yang XH, Li M, Shia G et al. Association of suboptimal health status and cardiovascular risk factors in urban Chinese workers. J Urban Health 2012; 89(2): 329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez F, Hicks LS, Lopez L. Association of acculturation and country of origin with self-reported hypertension and diabetes in a heterogeneous Hispanic population. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guwatudde D, Nankya-Mutyoba J, Kalyesubula R, Laurence C, Adebamowo C, Ajayi I et al. The burden of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: a four-country cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumara WA, Perera T, Dissanayake M, Ranasinghe P, Constantine GR. Prevalence and risk factors for resistant hypertension among hypertensive patients from a developing country. BMC Res Notes 2013; 6: 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang XY, Nie SF, Qu KY, Peng XX, Wei S, Zhu GB et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life among hypertensive patients in a rural area, PR China. J Hum Hypertens 2006; 20(3): 227–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adults physical health standard. Ministry of Education of China and General Administration of Sport of China. Beijing 2008.

- QuickStats: age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension treatment among adults aged ⩾18 years with hypertension, by sex and race/ethnicity—national health and nutrition examination survey, United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65(21): 553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Zhou T, Luo Y, Xie C, Huo D, Tao L et al. Risk factors for cerebrovascular disease mortality among the elderly in Beijing: a competing risk analysis. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(2): e87884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Klaric L, Yu X, Thaqi K, Dong J, Novokmet M et al. The association between glycosylation of immunoglobulin G and hypertension: a multiple ethnic cross-sectional study. Medicine 2016; 95(17): e3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanchetti A, Facchetti R, Cesana GC, Modena MG, Pirrelli A, Sega R. Menopause-related blood pressure increase and its relationship to age and body mass index: the SIMONA epidemiological study. J Hypertens 2005; 23(12): 2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman JM, Cerezo GH, Del Sueldo M, Fernandez-Perez C, Martell-Claros N, Vicario A. Association between hypertension, menopause, and cognition in women. J Clin Hypertens 2015; 17(12): 970–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagle R, Acevedo M, Valdes G. Hypertension in women. Rev Med Chil 2013; 141(2): 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsbergis PA, Diez-Roux AV, Fujishiro K, Baron S, Kaufman JD, Meyer JD et al. Job strain, occupational category, systolic blood pressure, and hypertension prevalence: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Occup Environ Med 2015; 57(11): 1178–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan NL, Rosendorf KA. Prevalence of hypertension and controlled hypertension—United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Suppl 2011; 60(1): 94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guwatudde D, Mutungi G, Wesonga R, Kajjura R, Kasule H, Muwonge J et al. The epidemiology of hypertension in Uganda: findings from the National Non-Communicable Diseases Risk Factor Survey. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(9): e0138991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notara V, Panagiotakos DB, Kogias Y, Stravopodis P, Antonoulas A, Zombolos S et al. The impact of educational status on 10-year (2004-2014) cardiovascular disease prognosis and all-cause mortality among acute coronary syndrome patients in the Greek Acute Coronary Syndrome (GREECS) Longitudinal Study. J Prev Med Public Health 2016; 49(4): 220–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert E, Sari CI, Dawood T, Nguyen J, Mcgrane M, Eikelis N et al. Sympathetic nervous system activity is associated with obesity-induced subclinical organ damage in young adults. Hypertension 2010; 56(3): 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Kishi T, Ito K, Sunagawa K. Potential clinical application of recently discovered brain mechanisms involved in hypertension. Hypertension 2013; 62(6): 995–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Wang H, Chen S, Ross S, Liu H, Olivencia-Yurvati A et al. Aerobic exercise training improves orthostatic tolerance in aging humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017; 49(4): 728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump C, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Interactive effects of physical fitness and body mass index on the risk of hypertension. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(2): 210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarska A, Lipowicz A. BMI, hypertension and low bone mineral density in adult men and women. Homo 2012; 63(4): 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jae SY, Kurl S, Franklin BA, Laukkanen JA. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness predict incident hypertension: a population-based long-term study. Am J Hum Biol. 2017; 29: e22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes-Silva IC, Mostarda C, Moreira ED, Silva KA, Dos Santos F, De Angelis K et al. Preventive role of exercise training in autonomic, hemodynamic, and metabolic parameters in rats under high risk of metabolic syndrome development. J Appl Physiol 2013; 114(6): 786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Sui X, Church TS, Lavie CJ, Jackson AS, Blair SN. Changes in fitness and fatness on the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59(7): 665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley-Lewis R, Powe C, Ankers E, Wenger J, Ecker J, Thadhani R. Effect of race/ethnicity on hypertension risk subsequent to gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113(8): 1364–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull S, Dreyer G, Badrick E, Chesser A, Yaqoob MM. The relationship of ethnicity to the prevalence and management of hypertension and associated chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 2011; 12: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Watanabe Y, Yamanishi K, Yamashita A, Yamamoto H, Okuzaki D et al. Analysis of genes causing hypertension and stroke in spontaneously hypertensive rats: gene expression profiles in the brain. Int J Mol Med 2014; 33(4): 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Shi L, Li S, Xu L, Qin W, Wang H. Urban-rural disparities in hypertension prevalence, detection, and medication use among Chinese Adults from 1993 to 2011. Int J Equity Health 2017; 16(1): 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini M, Yousefifard M, Baikpour M, Rafei A, Fayaz M, Heshmat R et al. Twenty-year dynamics of hypertension in Iranian adults: age, period, and cohort analysis. J Am Soc Hypertens 2015; 9(12): 925–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]