Abstract

Small oxoacids of sulfur (SOS) are elusive molecules like sulfenic acid, HSOH, and sulfinic acid, HS(O)OH, generated during the oxidation of hydrogen sulfide, H2S, in aqueous solution. Unlike their alkyl homologs, there is a little data on their generation and speciation during H2S oxidation. These SOS may exhibit both nucleophilic and electrophilic reactivity, which we attribute to interconversion between S(II) and S(IV) tautomers. We find that SOS may be trapped in situ by derivatization with nucleophilic and electrophilic trapping agents and then characterized by high resolution LC MS. In this report, we compare SOS formation from H2S oxidation by a variety of biologically relevant oxidants. These SOS appear relatively long lived in aqueous solution, and thus may be involved in the observed physiological effects of H2S.

Keywords: Hydrogen sulfide, Sulfenic acid, Sulfinic acid, Dimedone, And bromobimane

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Small oxoacids of sulfur (SOS) are generated in the biomimetic oxidations of H2S.

-

•

SOS were trapped and characterized using LC-HRMS.

-

•

Unique sulfenyl and sulfinyl tautomers for each SOS were identified.

-

•

Heme globins and cobalamin react with H2S to generate SOS.

-

•

SOS should be considered in the observed biological action of H2S.

1. Introduction

The chemical biology of hydrogen sulfide, H2S, has gained much attention with the recent discovery of its endogenous generation [1], [2], as well as its implication in a variety of physiological functions such as vasodilation [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] and inflammation [8], [9], [10]. However, its mechanism of action is still not well understood, and there are reports that implicate H2S biological functions may in part due to the H2S derived oxidized products [11], [12]. For example, SO2 has been shown to have protective effects in cardio vascular models akin to H2S and NO [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23].

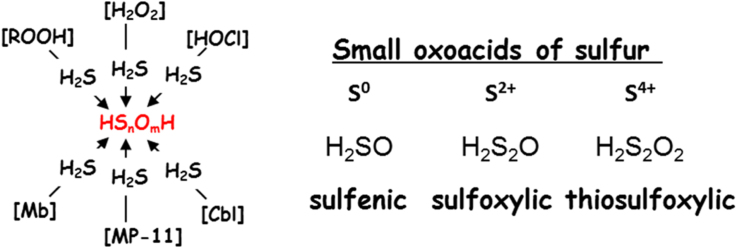

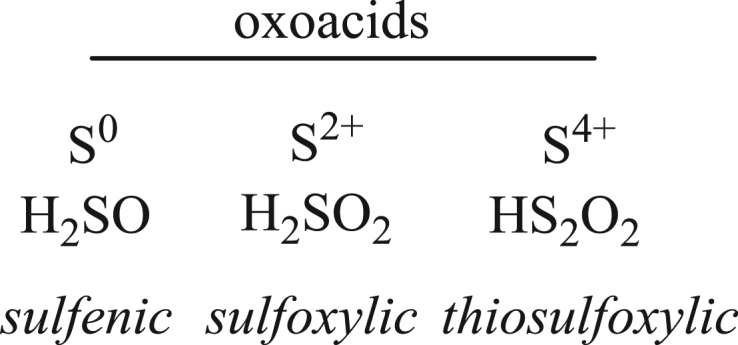

Scheme 1 shows several low valent species formed during oxidation of H2S in water, which we denote as SOS, small oxoacids of sulfur species. These include sulfenic (HSOH) [24], [25], sulfoxylic (H2SO2) [26], and thiosulfoxylic acids (H2S2O2) [27], all of which have tautomeric forms. The sulfoxylic acids may dehydrate to sulfur monoxide (SO) [28]. These SOS are highly reactive and notoriously difficult to characterize in biologically relevant conditions, and unlike their alkyl homologs, there is a little data on SOS generation and speciation during H2S oxidation [29], [30], [31], [32]. We recently reported trapping of both sulfenyl and sulfinyl tautomers of oxidized glutathione derivatives using a combination of selective nucleophilic and electrophilic trapping reagents and characterization by high resolution LC MS [33]. We hypothesize that the physiological effect of H2S may derive from SOS, and thus we investigated their formation in biologically relevant conditions using similar methods, in situ derivatization with nucleophilic sulfenyl trapping reagent dimedone [34], [35] and electrophilic reagents iodoacetamide, as well as mono- and di-bromobimane [36]. We will show that the oxidation of H2S by biologically relevant oxidants using these reagents produces unique products that logically derive from sulfenyl and sulfinyl tautomeric of the SOS.

Scheme 1.

Small oxoacids of sulfur (SOS) species.

The generated SOS were derivatized by reaction with nucleophilic traps such as dimedone (DH) and 1-trimethylsiloxycyclohexene [33], as well as electrophilic traps such as iodoacetamide (IA), and mono- or di-bromobimane (BrB and Br2B). In a standard experiment, 1 mM Na2S dissolved in pH 7 iP buffer was reacted with 1.2 mM of maleic peroxide, a soft oxidant formed in situ by mixing H2O2 with maleic anhydride; five minutes after reaction initiation, a 5 fold excess of trapping reagents are added [37]. After 1 h, the reaction mixture was injected into an Orbitrap LC HRMS, typically analyzed in the positive ion mode using the gradient elution method with 0.1% formic acid-acetonitrile eluent. Reaction products were identified as [M+H+] singly charged ion peaks, with expected isotope patterns for [34] S and [13] C abundances. Single Ion Chromatograms (SICs) are shown to confirm that the observed species are present in the reaction mixture and separated on the LC column prior to ionization. Further experimental details are given in Supplemental Materials (S1)

2. Sulfenic acid, HSOH

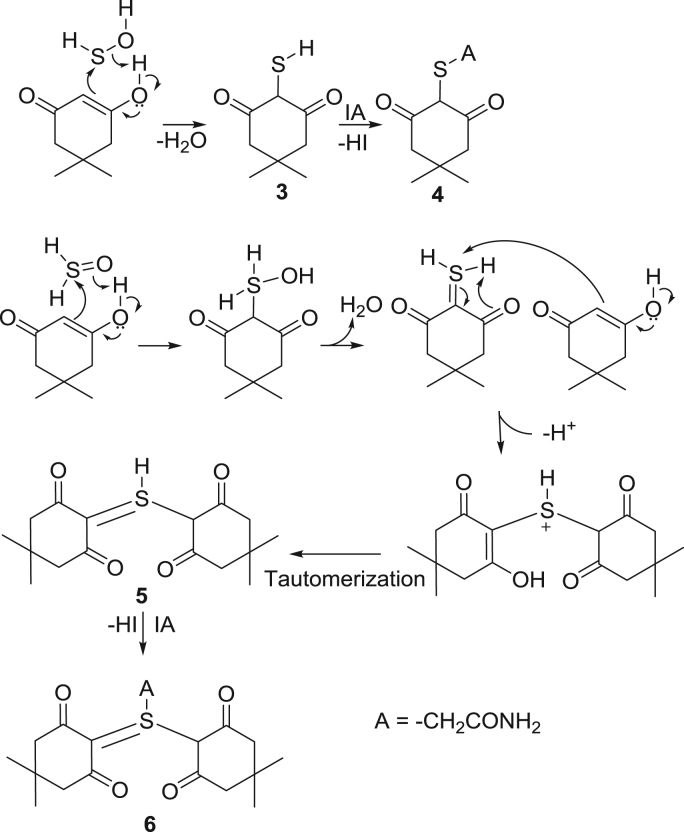

The initial oxoacid produced by H2S oxidation is sulfenic acid, HSOH. It may exist in two tautomeric forms [38], [39], [40], sulfenyl and sulfinyl, 1 and 2, Scheme 2, which should generate different derivatized products, as were observed in glutathione peroxidations [33 ]. Upon reaction of H2S with peroxymaleic acid, the sulfenyl tautomer is trapped by sequential reaction with dimedone and iodoacetamide yielding the thioether derivative, 4 in Scheme 3 and Fig. 1; an analogous thioether adduct is observed using bromobimane and iodoacetamide traps (S2). In the same reaction mixtures, the sulfinyl tautomer is trapped by consecutive Knoevenagel and Michael additions with dimedone, yielding tetravalent S species, ylide 6 [41], [42]. The SICs of these species, along with [M+H+] LCMS spectra are shown in Fig. 1. The electrophilic and nucleophilic characteristics of HSOH is also evident in its reaction with 1-trimethylsiloxycyclohexene (S4), which yields unique products analogous to those seen in glutathione peroxidations [33].

Scheme 2.

Tautomeric forms of sulfenic acid.

Scheme 3.

Sequential reaction mechanism of trapping of sulfenic acid tautomers.

Fig. 1.

Selective ion chromatogram and mass spectra of products 3, 4, 6 and 8, obtained in oxidation of H2S (1 mM) with maleic peroxide (1.2 mM) in pH 7 iP buffer, trapped with a bolus of (5 mM) dimedone and iodoacetamide after 5 mins.

The lifetime of HSOH under these experimental conditions was assessed by allowing the reaction mixtures to set for various times before addition of trapping reagents. Using quantification of species 4 gives an approximate half-life for HSOH of 40 mins (S3), much longer than expected for such a reactive species in presence of reactive thiols. By comparison, most kinetic studies of S-based radicals suggest sub-second lifetimes, especially in polar solvent such as water [43].

A second ylide 8 is also observed, which we propose derives from dehydration of the intermediate Knovenegal product 7, Scheme 4 [44]. It may possible that this species may be a cyclic sulfurane product 10 derived from 9, the enol tautomer of 7. Further evidence for ylide 8 was obtained in the trapping reactions with BrB, iodoacetamide and dimedone (S5). An analogous ylide is seen in peroxidations of glutathione (S5). These three general derivatization reactions will be used throughout this report to differentiate between sulfenyl and sulfinyl functionalities in the trapped SOS described.

Scheme 4.

Reaction mechanism of sulfinyl trapping.

The presence of both tautomers 1 and 2 is affirmed by derivatization with BrB, Scheme 5. The SIC of mass 240.0641 shows two broad peaks, Fig. 2, that we ascribe to tautomeric forms of BSOH, 11, and BS(O)H, 12. The ratio of two, as determined by peak areas, is 100:29 with the sulfenyl tautomer likely the thermodynamically preferred. The presence of the sulfinyl tautomer is clearly shown in production of the bis(bimane) sulfoxide 13. Similarly if the bisbromobimane, Br2B, 14, is used, a novel bimane sulfoxide 15 is observed. While interconversion between tautomers 11 and 12 is possible, it must be relatively slow as products from both tautomers are observed. A reviewer suggested that S-alkylation of divalent sulfenyl tautomer such as 11 may also generate the sulfinyl 13 after deprotonation and thus provide alternative pathways to species seen.

Scheme 5.

Derivatized products of 1 and 2.

Fig. 2.

Selective ion chromatograms and mass spectra of products 11, 12, 13 and 15, obtained in oxidation of H2S (1 mM) with maleic peroxide (1.2 mM) in presence of mono- and dibromobimane (5 mM) in pH 7 IP buffer.

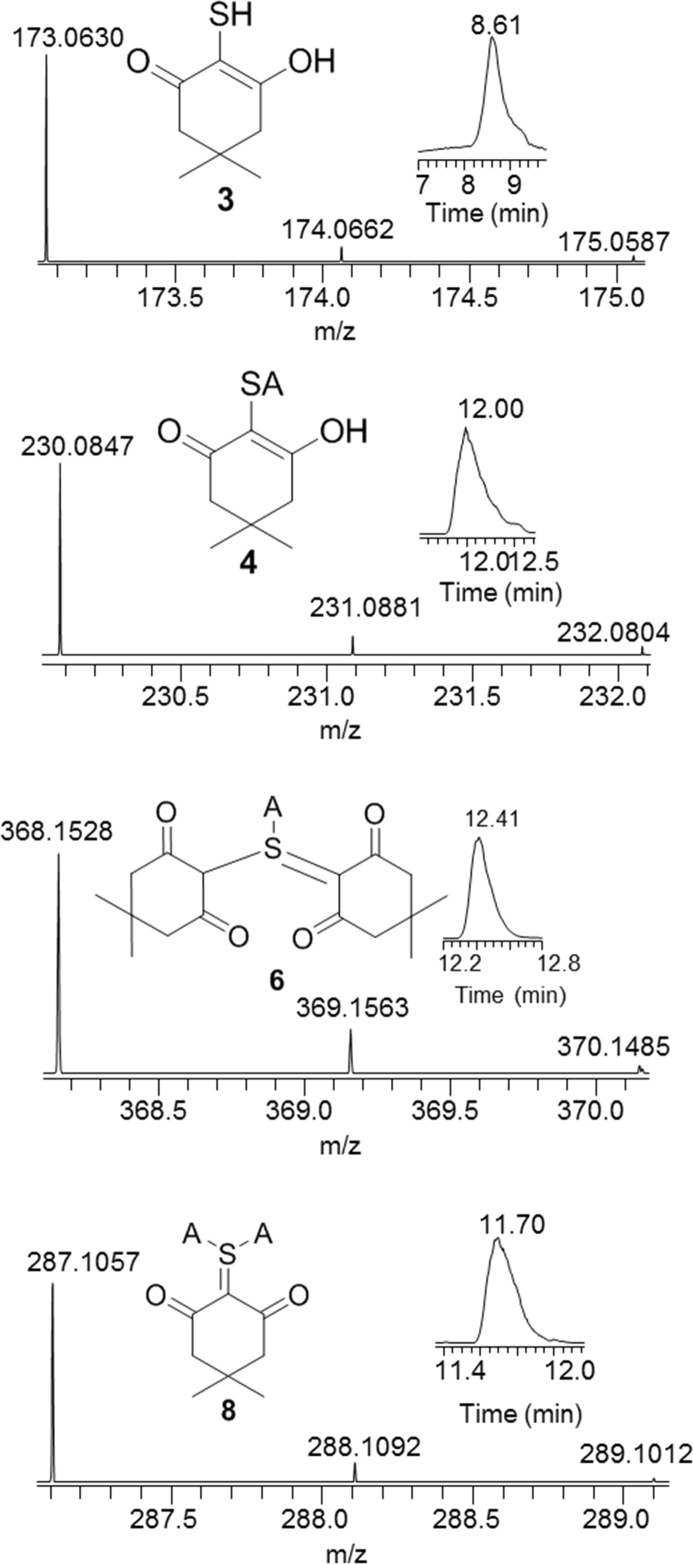

3. Sulfoxylic acid, H2SO2

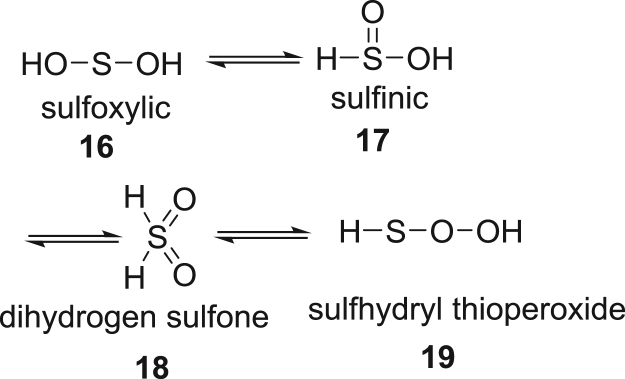

The dioxygenation product of H2S, H2SO2, may exist as sulfoxylic, 16, sulfinic, 17 dihydrogen sulfone, 18 or the sulfhydryl peroxide, 19, tautomer shown in Scheme 6 [45]. Theoretical calculations suggest that alcohol 16 is the most stable, and peroxide 19 is the least stable tautomer. Using the trapping methodology described, only tautomers 16 and 17 are observed, which suggests these dominate speciation in aqueous solution.

Scheme 6.

Sketch of tautomeric forms sulfoxylic acid, H2SO2.

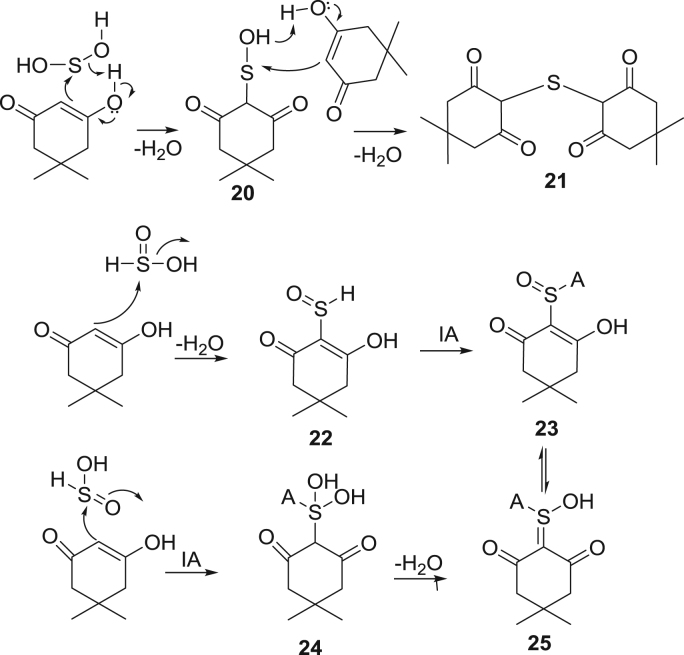

The sulfoxylic tautomer 16 is trapped by sequential addition of dimedone, generating thioether 21, Scheme 7 and Fig. 3. The dimedone reacts with sulfinic tautomer 17 attacking SO moiety with elimination of hydroxyl to yield 22 or by Knovenegal type addition yielding 24. Intramolecular dehydration of 24 gives 25 which might exist in equilibrium with 23, but the dehydration is likely kinetically slow. Theory predicts sulfoxylic tautomer to be the lowest energy tautomer in the gas phase [45], but the ratio of sulfoxylic and sulfinic acid under our reaction conditions, as by trapped species 21 vs 23/25, is 7:100. Thus the S(IV) oxidation state predominates, perhaps aqueous solvation favors the more acidic sulfinic form.

Scheme 7.

Sequential reaction mechanism of trapping of sulfoxylic tautomers.

Fig. 3.

Selective ion chromatogram and mass spectra of products 21 and 23, and 25 obtained in oxidation of H2S (1 mM) with maleic peroxide (1.2 mM) in buffer, pH 7, trapped by a bolus of dimedone and acetamide (5 mM) after 5 min.

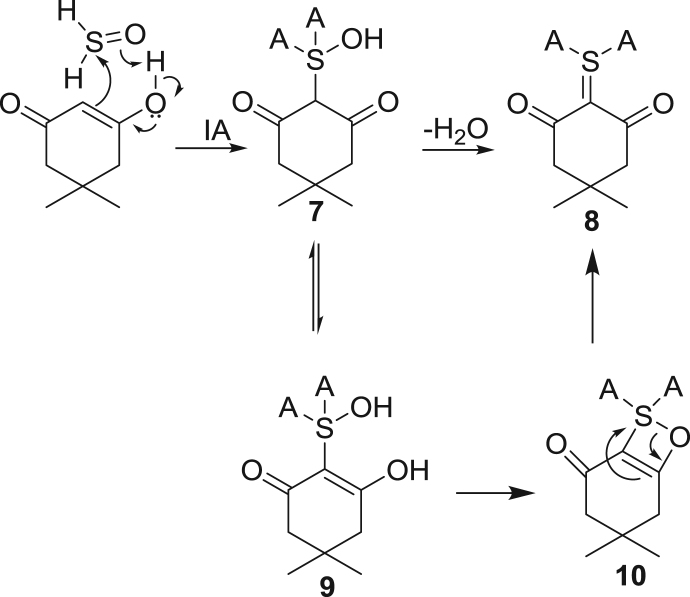

4. SOS generation from biological oxidants

Utilizing the standard reaction conditions and trapping methods described above, the relative efficiency of SOS generation by a variety of biological oxidants was compared in aerobic, aqueous conditions. The common oxidants hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [46], hypochloric acid (HOCl) [47], [48]; and maleic peroxide [37], are expected to directly form the SOS by O-atom transfer, Eq. (1). Metalloprotein oxidants such as metmyoglobin (Mb), and microperoxidase (MP-11), hydroxycobalamin (Cbl) are expected to initially oxidize H2S by outersphere mechanism, effecting a 1 e- oxidation per metal ion Eq. (2), but these may also participate in catalytic reduction of O2 under the experimental conditions.

| H2O2+H2S→H2SO+H2O | (1) |

| 2 M++H2S+H2O→H2SO+2 M | (2) |

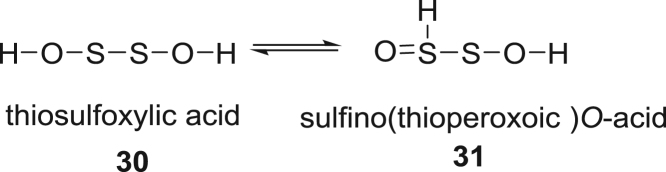

Fig. 4 shows the yield of SOS observed in oxidations of H2S by various biologically relevant oxidants, as determined by the summation of SIC peak areas of the derivatized products generated under analogous reaction conditions (peak areas given in Table S6). For example, oxidation of H2S by equivalent stoichiometries of H2O2 and MP-11 formed approximately equivalent amounts of HSOH, by relative amounts yields of derivatized species 4 observed.

Fig. 4.

Relative efficiency of HSOH and HOSOH generation in reactions of H2S with various oxidants, based on the SIC peak areas for trapped species 4 and 21. All reactions done in the ratio of 1 mM H2S, 1.2 mM oxidant in iP buffer pH 7, trapped by addition of 5 mM bolus of iodoacetamide and dimedone after 5 mins. The peak heights and error bars derive from an average of three experiments.

As seen in Fig. 4, HOCl was the most selective peroxide at generating HSOH, with H2O2 generating 3:2 mixtures of HSOH and HOSOH. As previously mentioned, the milder oxidant maleic peroxide gave lower levels of the primary SOS, but generates best yields of less stable tautomers, perhaps due to a slower rate of reaction. All of the metalloprotein oxidants generated measurable SOS, with MP-11 the more selective for formation of HSOH over HOSOH. Among these metalloproteins, MP-11 has an exposed heme cofactor which perhaps facilitating direct interaction with H2S.

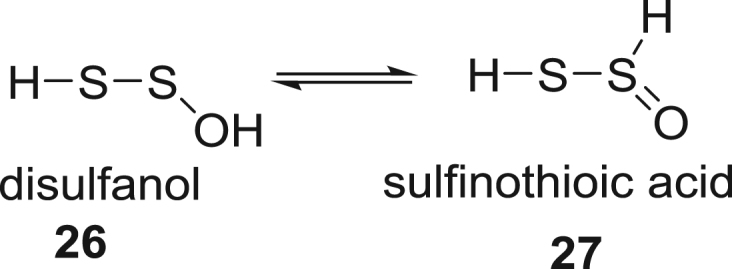

5. Polysulfide oxoacids

Several polysulfide SOS (H2SnOm) are also observed in these reaction mixtures, especially in reactions of H2S with the harder oxidants such as peroxide and hypochlorite, Fig. 5. The simples polysulfide oxide, H2S2O, has nine possible tautomers [49], [50], but only products of the disulfanol, 26 and sulfinothioic acid, 27 are observed under our conditions, Scheme 8. Trapping of 26 with dimedone followed by addition of iodoacetamide yielded disulfide 28 and the product 29 from the Knovenegal intermediate. The ratio of tautomers 26:27 was calculated to be 100:12, in line with theoretical calculations of stability [49]. Additional evidence for 26 and 27 comes from the trapping of this species by 1-trimethylsiloxycyclohexene, monobimane and dibimane (Supplemental S7).

Fig. 5.

Selective ion chromatogram and mass spectra of products 28 and 29, obtained in oxidation of H2S (1 mM) with hydrogen peroxide-maleic anhydride mixture (1.2 mM) in pH 7 buffer, trapped by a bolus of dimedone and acetamide (5 mM) after 5 min.

Scheme 8.

Sketch of tautomeric forms of H2S2O.

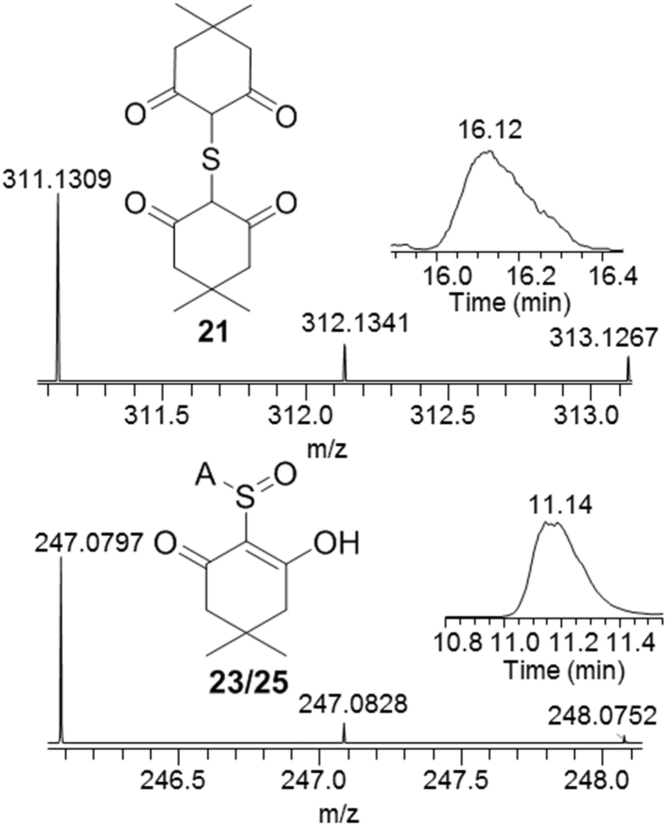

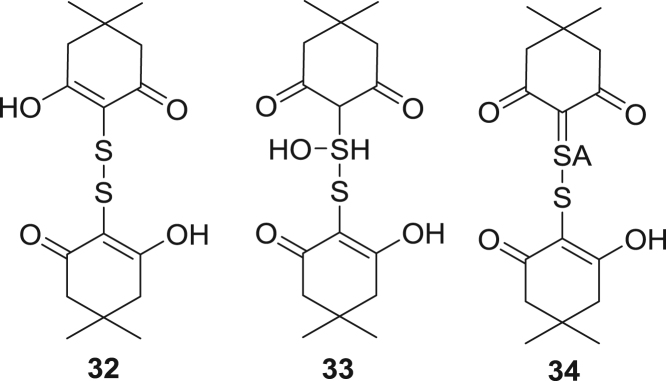

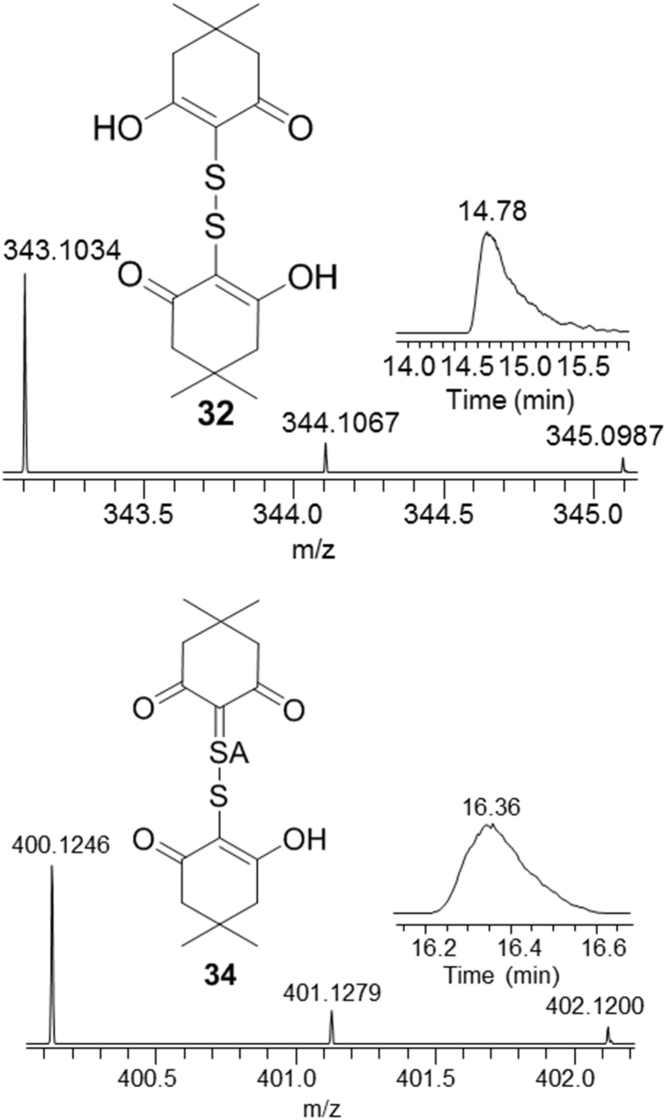

Similarly, dioxydisulfides of the formula H2S2O2, have been reported to be generated in reactions of H2S with SO2 in the Wackenroder process [51], [52]. Of the seven possible tautomers, only derivatives of two terminal oxides are observed in H2S oxidations by derivatization, Scheme 9, the diol 30 and mixed tautomer 31 which contains both sulfenyl and sulfinyl functionalities. Nucleophilic trapping of 30 with dimedone yields the disulfide 32, Scheme 10 and Fig. 6. Analogous addition of 31 with dimedone, would give intermediate product 33, which undergoes further elimination to yield 34. The observed ratio of products 32 to 34 is 100:11. Additional evidence for 30 comes from trapping of it with 1-trimethylsiloxycyclohexene (S8).

Scheme 9.

Sketch of tautomeric forms of H2S2O2.

Scheme 10.

Derivatized products of 30 and 31.

Fig. 6.

Selective ion chromatogram and mass spectra of products 31 and 33, obtained in oxidation of H2S (1 mM) with hydrogen peroxide-maleic anhydride mixture (1.2 mM) in pH 7 buffer, trapped by a bolus of dimedone and iodoacetamide (5 mM) after 5 min.

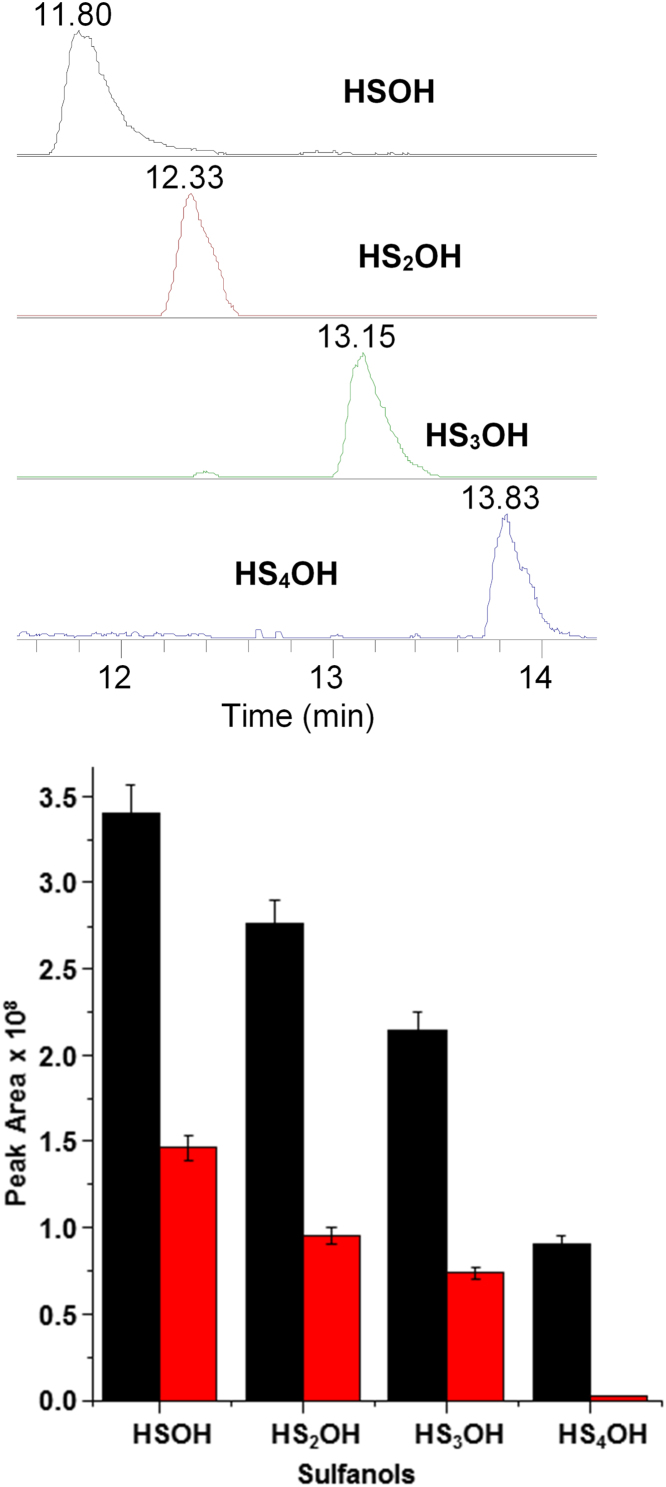

In all reactions, larger polysulfanes mono- and di-oxides HSxOH and HSxO2H are also trapped, as demonstrated by the SICs of polysulfide oxides observed in reactions with H2O2 and MP-11, Fig. 7 and S9. As previously mentioned, the harder oxidants generate the more persulfanes; for example, the ranking of observed efficiency of HS3OH formation is peroxide > hypochlorite> MP > MP-11 > Mb > Cbl. A recent theoretical study found a relatively low energy reaction pathway reaction of H2S with sulfur oxides [53], and suggested that the S-S catenation is catalyzed by hydrogen bonding interactions in water. Thus these polysulfanes oxides may arise from initially formed SOS reacting with H2S, Eqs. (3), (4).

| HSOH+H2S→HSSH+H2O | (3) |

| HOSOH+H2S→HSSOH+H2O | (4) |

Fig. 7.

Selective ion chromatographs (top) and relative peak areas of those SICs (bottom) of HSnOH generation in reactions of H2S with H2O2 (black) and MP-11 (red). The reactions done in the ratio of 1 mM H2S and 1.2 mM oxidant in iP buffer pH 7, trapped by a bolus of iodoacetamide and dimedone (5 mM) after 5 mins. The peak heights and error bars derive from an average of three experiments. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

6. Biological implications

These experiments suggest that SOS are formed readily in aqueous oxidations of H2S, and are relatively long lived. Like reactive oxygen species, SOS are produced in an evolving flux, i.e., HSOH generation begets HSO2H, and other species described here. Our results show that SOS may generated from H2S by endogenous biological oxidants, and thus represent a new class of small reactive molecules which should be considered in the chemical biology of H2S [54]. For example, many metalloproteins are reduced by H2S, e.g. metcobalamin is reduced by aerobic reaction with H2S [55]. Several recent studies report that oxidation of H2S by ferric heme proteins metmyoglobin and catalase generate polysulfides [56], [57], [58]; we suggest that these products may derive from initial SOS generation. Likewise, persulfide coordinated [2Fe-2S] has been detected during the mechanism of iron-sulfur cluster formation in fumarate and nitrate reduction (FNR), which was explained by cluster sulfur oxidation of unknown sulfur oxygen species [59].

Of course, alternative pathways are possible for H2S oxidation besides SOS generation, i.e., radical coupling that form S‒S bonds directly, or the precipitation of elemental sulfur, S0. But we believe the oxoacids form a unique and long-lived class of biomolecules that may have distinctive activities.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from the National Science Foundation (CHE-1057942 and CHE-1428729) and from Baylor University Mass Spectroscopy Facility.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.redox.2017.10.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Szabó C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol. Rev. 2012;92:791–896. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosoki R., Matsuki N., Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;237:527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teague B., Asiedu S., Moore P.K. The smooth muscle relaxant effect of hydrogen sulphide in vitro: evidence for a physiological role to control intestinal contractility. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:139–145. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao W., Zhang J., Lu Y., Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mani S., Li H., Untereiner A., Wu L., Yang G., Austin R.C., Dickhout J.G., Lhoták Š., Meng Q.H., Wang R. Decreased endogenous production of hydrogen sulfide accelerates atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2013;127:2523–2534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bir S.C., Kevil C.G. Sulfane sustains vascular health: insights into cystathionine γ-lyase function. Circulation. 2013;127:2472–2474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Distrutti E., Sediari L., Mencarelli A., Renga B., Orlandi S., Antonelli E., Roviezzo F., Morelli A., Cirino G., Wallace J.L., Fiorucci S. Evidence that hydrogen sulfide exerts antinociceptive effects in the gastrointestinal tract by activating KATP channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;316:325–335. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L., Bhatia M., Zhu Y.Z., Zhu Y.C., Ramnath R.D., Wang Z.J., Anuar F.B.M., Whiteman M., Salto-Tellez M., Moore P.K. Hydrogen sulfide is a novel mediator of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in the mouse. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2005;19:1196–1198. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3583fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hegde A., Bhatia M. Hydrogen sulfide in inflammation: friend or foe? Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:118–122. doi: 10.2174/187152811794776268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono K., Akaike T., Sawa T., Kumagai Y., Wink D.A., Tantillo D.J., Hobbs A.J., Nagy P., Xian M., Lin J., Fukuto J.M. The redox chemistry and chemical biology of H2S, hydropersulfides and derived species: implications to their possible biological activity and utility. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;0:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ida T., Sawa T., Ihara H., Tsuchiya Y., Watanabe Y., Kumagai Y., Suematsu M., Motohashi H., Fujii S., Matsunaga T., Yamamoto M., Ono K., Devarie-Baez N.O., Xian M., Fukuto J.M., Akaike T. Reactive cysteine persulfides and S-polythiolation regulate oxidative stress and redox signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321232111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X.-B., Du J.-B., Cui H. Sulfur dioxide, a double-faced molecule in mammals. Life Sci. 2014;98:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart J.L. Role of sulfur-containing gaseous substances in the cardiovascular system. Front. Biosci. Elite Ed. 2011;3:736–749. doi: 10.2741/e282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y., Tang C., Du J., Jin H. Endogenous sulfur dioxide: a new member of gasotransmitter family in the cardiovascular system. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016;2016:8961951. doi: 10.1155/2016/8961951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nie A., Meng Z. Study of the interaction of sulfur dioxide derivative with cardiac sodium channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2005;1718:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nie A., Meng Z. Sulfur dioxide derivative modulation of potassium channels in rat ventricular myocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;442:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nie A., Meng Z. Sulfur dioxide derivatives modulate Na/Ca exchange currents and cytosolic [Ca2+]i in rat myocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;358:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J., Li R., Meng Z. Sulfur dioxide upregulates the aortic nitric oxide pathway in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;645:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X.-B., Jin H.-F., Tang C.-S., Du J.-B. The biological effect of endogenous sulfur dioxide in the cardiovascular system. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;670:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Q., Meng Z. The negative inotropic effects of gaseous sulfur dioxide and its derivatives in the isolated perfused rat heart. Environ. Toxicol. 2012;27:175–184. doi: 10.1002/tox.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q., Meng Z. The vasodilator mechanism of sulfur dioxide on isolated aortic rings of rats: involvement of the K+ and Ca2+ channels. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009;602:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng Z., Li Y., Li J. Vasodilatation of sulfur dioxide derivatives and signal transduction. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;467:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iraqi M., Schwarz H. Experimental evidence for the gas phase existence of HSOH (hydrogen thioperoxide) and SOH2 (thiooxonium ylide) Chem. Phys. Lett. 1994;221:359–362. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winnewisser G., Lewen F., Thorwirth S., Behnke M., Hahn J., Gauss J., Herbst E. Gas-phase detection of HSOH: synthesis by flash vacuum pyrolysis of Di-tert-butyl sulfoxide and rotational-torsional spectrum. Chem. Eur. J. 2003;9:5501–5510. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.S.V. Makarov, A.S. Makarova, R. Silaghi-Dumitrescu, Sulfoxylic and thiosulfurous acids and their dialkoxy derivatives, in: PATAI’S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. (2009).

- 27.Schmidt H., Steudel R., Suelzle D., Schwarz H. Sulfur compounds. 148. Generation and characterization of dihydroxy disulfide, HOSSOH: the chainlike isomer of thiosulfurous acid. Inorg. Chem. 1992;31:941–944. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klaus T., Saleck A.H., Belov S.P., Winnewisser G., Hirahara Y., Hayashi M., Kagi E., Kawaguchi K. Pure rotational spectra of SO: rare isotopomers in the 80-GHz to 1.1-THz region. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1996;180:197–206. doi: 10.1006/jmsp.1996.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuevasanta E., Möller M.N., Alvarez B. Biological chemistry of hydrogen sulfide and persulfides. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017;617:9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Besnainou S., Whitten J.L. Intermediate molecular species in the oxidation of hydrogen sulfide. An ab initio configuration interaction study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:7444–7448. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smardzewski R.R., Lin M.C. Matrix reactions of oxygen atoms with H2S molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1977;66:3197–3204. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Packer J.E. Radiolysis of aqueous solutions of hydrogen sulphide and an interpretation of radiolytic thiol oxidation. Nature. 1962;194:81–82. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar M.R., Farmer P.J. Trapping reactions of the sulfenyl and sulfinyl tautomers of sulfenic acids. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:474–478. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furdui C.M., Poole L.B. Chemical approaches to detect and analyze protein sulfenic acids. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2014;33:126–146. doi: 10.1002/mas.21384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta V., Carroll K.S. Sulfenic acid chemistry, detection and cellular lifetime. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:847–875. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wintner E.A., Deckwerth T.L., Langston W., Bengtsson A., Leviten D., Hill P., Insko M.A., Dumpit R., VandenEkart E., Toombs C.F., Szabo C. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pietikäinen P. Asymmetric Mn(III)-salen catalyzed epoxidation of unfunctionalized alkenes with in situ generated peroxycarboxylic acids. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 2001;165:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denis P.A. Theoretical characterization of the HSOH, H2SO and H2OS isomers. Mol. Phys. 2008;106:2557–2567. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baum O., Esser S., Gierse N., Brünken S., Lewen F., Hahn J., Gauss J., Schlemmer S., Giesen T.F. Gas-phase detection of HSOD and empirical equilibrium structure of oxadisulfane. J. Mol. Struct. 2006;795:256–262. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freeman F. Mechanisms of reactions of sulfur hydride hydroxide: tautomerism, condensations, and C-sulfenylation and O-sulfenylation of 2,4-pentanedione. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2015;119:3500–3517. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b00779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozlov N.G., Kadutskii A.P. A novel three-component reaction of anilines, formaldehyde and dimedone: simple synthesis of spirosubstituted piperidines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:4560–4562. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li M., Chen C., He F., Gu Y. Multicomponent reactions of 1,3-cyclohexanediones and formaldehyde in glycerol: stabilization of paraformaldehyde in glycerol resulted from using dimedone as substrate. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asmus K.-D. Stabilization of oxidized sulfur centers in organic sulfides. radical cations and odd-electron sulfur-sulfur bonds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979;12:436–442. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones, G., 2004. The Knoevenagel condensation, in: Organic Reactions, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- 45.Crabtree K.N., Martinez O., Barreau L., Thorwirth S., McCarthy M.C. Microwave detection of sulfoxylic acid (HOSOH) J. Phys. Chem. A. 2013;117:3608–3613. doi: 10.1021/jp400742q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabai G., Orban M., Epstein I.R. Systematic design of chemical oscillators. 77. A model for the pH-regulated oscillatory reaction between hydrogen peroxide and sulfide ion. J. Phys. Chem. 1992;96:5414–5419. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azizi M., Biard P.-F., Couvert A., Ben Amor M. Competitive kinetics study of sulfide oxidation by chlorine using sulfite as reference compound. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015;94:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagy P., Winterbourn C.C. Rapid reaction of hydrogen sulfide with the neutrophil oxidant hypochlorous acid to generate polysulfides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;23:1541–1543. doi: 10.1021/tx100266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steudel R., Drozdova Y., Hertwig R.H., Koch W. Structures, energies, and vibrational spectra of several isomeric forms of H2S2O and Me2S2O: an ab initio study. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:5319–5324. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman F., Bui A., Dinh L., Hehre W.J. Dehydrative cyclocondensation mechanisms of hydrogen thioperoxide and of alkanesulfenic acids. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2012;116:8031–8039. doi: 10.1021/jp3024827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schenk P.W., Kretschmer W. The intermediate product of the Wackenroder reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1962;1:550–551. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miaskiewicz K., Steudel R. Sulphur compounds. Part 140. Structures and relative stabilities of seven isomeric forms of H2S2O2. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1991:2395–2399. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar M., Francisco J.S. Elemental sulfur aerosol-forming mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:864–869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620870114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fukuto J.M., Carrington S.J., Tantillo D.J., Harrison J.G., Ignarro L.J., Freeman B.A., Chen A., Wink D.A. Small molecule signaling agents: the integrated chemistry and biochemistry of nitrogen oxides, oxides of carbon, dioxygen, hydrogen sulfide, and their derived species. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012;25:769–793. doi: 10.1021/tx2005234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salnikov D.S., Kucherenko P.N., Dereven’kov I.A., Makarov S.V., van Eldik R. Kinetics and mechanism of the reaction of hydrogen sulfide with cobalamin in aqueous solution. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014;2014:852–862. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201402082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bostelaar T., Vitvitsky V., Kumutima J., Lewis B.E., Yadav P.K., Brunold T.C., Filipovic M., Lehnert N., Stemmler T.L., Banerjee R. Hydrogen sulfide oxidation by myoglobin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8476–8488. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kevil C.G. Catalase as a regulator of reactive sulfur metabolism; a new interpretation beyond hydrogen peroxide. Redox Biol. 2017;12:528–529. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olson K.R., Gao Y., DeLeon E.R., Arif M., Arif F., Arora N., Straub K.D. Catalase as a sulfide-sulfur oxido-reductase: an ancient (and modern?) regulator of reactive sulfur species (RSS) Redox Biol. 2017;12:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crack J.C., Thomson A.J., Brun N.E.L. Mass spectrometric identification of intermediates in the O2-driven [4Fe-4S] to [2Fe-2S] cluster conversion in FNR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:E3215–E3223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620987114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material