Key Points

The antiapoptotic protein BCL2 is a promising potential target in the treatment of CTCL.

Combination inhibition of BCL2 and HDACs leads to efficient killing of CTCL cells due to the synergistic activation of apoptosis.

Abstract

The presence and degree of peripheral blood involvement in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) portend a worse clinical outcome. Available systemic therapies for CTCL may variably decrease tumor burden and improve quality of life, but offer limited effects on survival; thus, novel approaches to the treatment of advanced stages of this non-Hodgkin lymphoma are clearly warranted. Mutational analyses of CTCL patient peripheral blood malignant cell samples suggested the antiapoptotic mediator B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) as a potential therapeutic target. To test this, we developed a screening assay for evaluating the sensitivity of CTCL cells to targeted molecular agents, and compared a novel BCL2 inhibitor, venetoclax, alone and in combination with a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, vorinostat or romidepsin. Peripheral blood CTCL malignant cells were isolated from 25 patients and exposed ex vivo to the 3 drugs alone and in combination, and comparisons were made to 4 CTCL cell lines (Hut78, Sez4, HH, MyLa). The majority of CTCL patient samples were sensitive to venetoclax, and BCL2 expression levels were negatively correlated (r = −0.52; P = .018) to 50% inhibitory concentration values. Furthermore, this anti-BCL2 effect was markedly potentiated by concurrent HDAC inhibition with 93% of samples treated with venetoclax and vorinostat and 73% of samples treated with venetoclax and romidepsin showing synergistic effects. These data strongly suggest that concurrent BCL2 and HDAC inhibition may offer synergy in the treatment of patients with advanced CTCL. By using combination therapies and correlating response to gene expression in this way, we hope to achieve more effective and personalized treatments for CTCL.

Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with a variety of clinical manifestations ranging from mycosis fungoides (MF; characterized by localized skin patches, plaques, and tumors) to leukemic CTCL, where malignant T cells may predominate the peripheral lymphocyte compartment.1 In advanced stages, CTCL is a fatal disease2 that is incurable with conventional therapies, with blood involvement portending poorer survival outcomes.3 With rare exceptions in cases of hematopoietic cell transplantation,4 the overall response rates for novel agents including retinoids, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, and pralatrexate range from 30% to 50% and are generally not durable.5 There remains an unmet medical need for new and more effective treatments.

Recent studies6-10 have made significant strides in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of CTCL, most notably via exome sequencing and expression analysis. These analyses have shown a predominance of gene copy-number alterations (GCNAs) over single-nucleotide variant (SNV) mutations. The categories of genetic alterations include changes in the behavior of the malignant T-cell population and their imprint on the immune system, and suggest clustering under 3 major pathways: constitutive T-cell activation, resistance to apoptosis/cell-cycle dysregulation, and DNA structural/gene expression dysregulation. With this wellspring of new information, recently discovered and repurposed agents targeting pathways or specific gene mutations may be screened as a patient-specific treatment algorithm is developed.

With 30% of drugs in clinical trials failing due to lack of efficacy,11 a focus on expanding indications of new molecular therapies allows us to leverage established safety profiles to fasttrack new treatment options for patients. One such opportunity for the repurposing of existing therapies involves the dysregulation of B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2)-driven apoptotic pathways in CTCL. Four common gene alterations identified in CTCL are STAT3 amplifications, STAT5B amplifications, P53 deletions, and CTLA4 deletions, the frequency of which was previously validated by our group in the development of a new diagnostic tool, an 11-gene fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) panel.12 Each of these mutations has been linked to the inhibition of apoptosis through the upregulation of BCL2 transcription, in turn leading to increased BCL2 activity and dependence.13-20

Venetoclax (ABT-199) is a BCL2 homology 3 (BH3)-mimetic, BCL2-selective inhibitor without additional cross-reactivity with BCL-XL, BCL-W, or myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL1).21 BCL2 family proteins are regulators of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, in which cell death is caused by the permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane, release of cytochrome c, and the activation of caspases.22 These proteins additionally regulate autophagy via the binding of Bclin-1.23 BCL2 itself is an antiapoptotic protein that promotes cell survival by sequestering proapoptotic factors. Venetoclax was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2016 and received accelerated approval for the treatment of relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with 17p deletion and is the only BCL2 inhibitor that has received approval by the US Food and Drug Administration for clinical use.24 Venetoclax is also currently undergoing trials for follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and NHL (excluding CTCL).

The potential for BCL2 inhibition in the treatment of CTCL may extend beyond its use as a monotherapy. Combined inhibition of BCL2 members and HDACs has shown synergistic effects in CTCL25 and other malignancies, including mantle cell lymphoma26 and glioblastoma.27 Romidepsin and vorinostat are HDAC inhibitors28 that have widespread effects including modulation of gene expression, induction of cellular differentiation, and modulation of apoptosis effector genes.29 One mechanism of action of apoptosis is via alterations in the expression of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, namely the BCL2 family genes,30-33 including upregulation of proapoptotic factors such as BH3 interacting-domain death agonist (BID) and Bcl-2-like protein 11 (BIM), and downregulation of the antiapoptotic factors such as BCL-XL and MCL1.34-36

Through in vitro testing of CTCL patient-derived blood samples, we demonstrate the potential of BCL2 inhibition by venetoclax as a novel treatment of CTCL. Furthermore, we reveal that this effect is synergistically potentiated via HDAC inhibition afforded by romidepsin or vorinostat. These results suggest that BCL2 inhibition, alone or in combination with HDAC inhibition, represents a viable novel strategy in the treatment of advanced CTCL with blood involvement.

Methods

Cell lines

MyLa 2059,37 Sez4,38 HH,39 and Hut7840 are well established CTCL cell lines. MyLa 2059 and HH were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. Sez4 was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL), as well as interleukin 2 (IL2) (20 ng/mL; R&D Systems) at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. Hut78 was cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) medium supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated FBS, glutamine (2 mM), penicillin 100 U/mL, and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. All media and supplements were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Patient samples

Blood samples were obtained from CTCL patients at the Yale Cancer Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the Yale Human Investigational Review Board. Peripheral blood samples from consenting patients and healthy donors were collected in lithium heparin tubes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated from whole blood by Ficoll density gradient. CD4+ T cells were selected with the MACS CD4+ negative selection kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), per the manufacturer’s protocol, and supplemented with antibodies to select for CD26− and/or CD7− cells, depending on the known aberrant phenotype of the patient. Aliquots of unfractionated PBMCs and purified samples were obtained to assess purity and verify expression of phenotypic markers. Following isolation, cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL), as well as IL2 (10 ng/mL), IL7 (5 ng/mL), IL15 (10 ng/mL), and IL13 (10 ng/mL; all cytokines from R&D Systems) at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity.

Flow cytometry analysis

Unfractionated PBMCs and isolated malignant T-cell populations were analyzed using flow cytometry. All samples were matched with an isotype control. The following monoclonal antibodies were included: CD3 from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); CD4, CD7, and CD26 from eBioscience (San Diego, CA); and TCR-Vβ from Beckman Coulter (Brea, CA). Cells were blocked with human TruStain FcX from BioLegend (San Diego, CA) for 10 minutes then incubated with selected antibodies for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then washed 3 times and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Flow cytometry was conducted on the Stratedigm-13 from Stratedigm Inc (San Jose, CA). All flow cytometric data were analyzed using FlowJo software (v10; FlowJo, LLC).

Cell viability assay

Following isolation of the desired cell population, cells were incubated at a density of 100 cells per microliter in 100 μL of media, for a total of 105 cells per well, in a black optical 96-well plate. Cells were incubated for 72 hours with venetoclax (3 nM to 100 µM), romidepsin (0.1-10 nM), and/or vorinostat (0.1-10 µM). The CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, WI) was used to measure the number of viable cells in culture based on quantitation of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) present. Plates were read using the Perkin Elmer Victor Light Luminescence Counter (Waltham, MA). Drug concentrations were applied in approximate half-log10 increments to patient samples, and in twofold increments for cell lines. Cell luminescence was normalized to a vehicle control containing 0.2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and corrected for media.

Caspase-3/7 assay

Patient samples were incubated for 24 hours as described in “Cell viability assay.” Following incubation, the Promega Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay (Madison, WI) was used to quantitate caspase activity, as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Plates were read using a PerkinElmer Victor X Light Luminescence Counter.

Reagents

Stocks of 50 nM venetoclax, 20 mM vorinostat, and 20 nM romidepsin from ApexBio (Houston, TX) were prepared in DMSO and stored at −20°C. Camptothecin (10 μM) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) was used as a positive control for both the viability assay and the Caspase-3/7 assay.

Statistical analysis

For the cell viability assay and Caspase-3/7 assays, each drug concentration was performed in quadruplicate, and the mean values were plotted with their respective standard deviation. The mean inhibitor concentration was determined using GraphPad Prism (version 7.01). Patient samples were grouped using hierarchical clustering with the Ward method41 in R (version 3.0.1). Combination index (CI) values and standard errors were calculated using the Chou-Talalay method42 in Microsoft Excel.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR

RNA was extracted using the All-Prep DNA/RNA Micro kit for patient samples, or with the All-Prep DNA/RNA Mini kit for cell lines from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s specifications. RNA was quantified using the BioTek Epoch spectrophotometer. RNA (2 μg) was converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using the High Capacity Reverse Transcription kit from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Patient cDNA samples were then preamplified using the Applied Biosystems TaqMan Pre-Amplification Master Mix as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was quantified using the TaqMan primers and Gene Expression Master Mix and the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) System. Samples were characterized in duplicates. Obtained cycle threshold (Ct) values were normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1) expression and expression differences relative to healthy controls were calculated using relative quantification, RQ = 2−ΔΔCt.

Results

CTCL patient population and peripheral blood analysis

To begin to assess the potential of the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax in the treatment of CTCL with blood involvement (B1 or B2), peripheral blood samples were obtained from 25 patients diagnosed with CTCL who have a malignant cell population measured by flow cytometry. Patients were classified by their initial diagnosis as erythrodermic/Sézary syndrome (13 of 25), MF (10 of 25), or folliculotropic MF (2 of 25) (Table 1). Patient treatment statuses ranged from extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) with or without adjunct therapies (18 of 25), to multimodal therapies (6 of 25), to cytoreductive therapy (1 of 25). Each patient sampled underwent clinical flow cytometry, from which blood parameters were calculated (Table 2). Patients were additionally tested for clonality by either PCR-based T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement studies or the presence of a clonal Vβ antigen detectable by flow cytometry, with 25 of 25 patient samples positive for clonality based on 1 or both tests. Eight patients were classified as B1, and the remainder were classified as B2 based on the 2007 International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) classification43 and the 2016 Gibson et al criteria.44

Table 1.

Summary of CTCL patients’ peripheral blood flow cytometric parameters

| Pt ID | Sorted abnormal cell population | TCR-Vβ+ | Vβ gene identified | PCR+ | CD4:CD8 ratio | CD4+CD7−, % | CD4+CD26−, % | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 20 | Yes | 8.37 | 19.7 | 14.1 | B1 |

| 2 | CD3+CD4+CD26− | Yes | 2 | Yes | 179.0 | 8.6 | 80.2 | B2 |

| 3 | CD3+CD4+CD26− | Yes | 12 | Yes | 2.12 | 8.9 | 34.3 | B2 |

| 4 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | Indirect | No | 8.11 | 14.3 | 38.5 | B2 |

| 5 | CD3+CD4+CD26− | Yes | 16 | Yes | 15.6 | 10 | 71.5 | B2 |

| 6 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 1 | Yes | 28.69 | 86.2 | 84.5 | B2 |

| 7 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 13.6 | None | 56.81 | 83.9 | 58.7 | B2 |

| 8 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 12 | Yes | 24.78 | 54.9 | 71.4 | B2 |

| 9 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | N/A | N/A | Yes | 10.22 | 38.9 | 36.5 | B2 |

| 10 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 13.1 | Yes | 7.06 | 44.3 | 25.5 | B2 |

| 11 | CD3+CD4+CD26− | Yes | 13.6 | Yes | 9.66 | 11.4 | 46 | B2 |

| 12 | CD3+CD4+CD26− | Yes | Indirect | Yes | 5.18 | 1.9 | 48.5 | B2 |

| 13 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 21.3 | Yes | 59.63 | 89.8 | 88.7 | B2 |

| 14 | CD3+CD4+CD26− | No | None | Yes | 4.45 | 16.2 | 4.8 | B1 |

| 15 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | Indirect | Yes | 6.95 | 63.9 | 62.6 | B2 |

| 16 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | Indirect | Yes | 20.02 | 87.2 | 76.3 | B2 |

| 17 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 7.2 | Yes | 4.7 | 30.4 | 33.8 | B2 |

| 18 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Yes | 7.2 | Yes | 3.74 | 27.4 | 26.0 | B1 |

| 19 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | No | None | No | 1.21 | 20.6 | 22.5 | B1 |

| 20 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Suspicion | Indirect | Yes | 1.63 | 22.5 | 24.5 | B1 |

| 21 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Suspicion | 5.3 | None | 4.75 | 69.6 | 71.8 | B2 |

| 22 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Suspicion | 17 | Yes | 1.75 | 19.9 | 18.5 | B1 |

| 23 | CD3+CD4+CD26− | Yes | 2 | Yes | 27.91 | 51.1 | 89.5 | B2 |

| 24 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | Suspicion | Indirect | Yes | 1.3 | 23.7 | 23.8 | B1 |

| 25 | CD3+CD4+CD7−CD26− | No | None | Yes | 8.87 | 24.9 | 19.1 | B1 |

Abnormal cell phenotype identified by flow cytometry as phenotypically atypical: TCR-Vβ+ if >50% of the population of atypical cells express a single Vβ, or by indirect evidence, if there is <20% expression of the entire 27 Vβ antibody panel.44 PCR+ if ≥1 of 3 PCRs identifies a clone. B stage based on ISCL classification43 and the 2016 criteria proposed by Gibson et al.44 Patients staged as B2 have elevated absolute CD3+ or CD3+CD4+ cell counts, with the upper limits of normal defined as >2245 cells per microliter and >1612 cells per microliter, respectively. CD4+CD7− and CD4+CD26− percent specifications are defined as percentage of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (lymphocytes and monocytes).

N/A, not assessed; Pt ID, patient identifier.

Table 2.

Summary of patient characteristics

| Pt ID | Sex | Age, y | CTCL subtype | Current therapy | Previous therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 73 | FMF | ECP | None |

| 2 | M | 84 | SS | Brentuximab, vorinostat | PUVA, ECP, vorinostat, MTX, bexarotene, IFNα-2b, romidepsin, gemcitabine/doxorubicin, alemtuzumab |

| 3 | M | 66 | SS | ECP | NB-UVB, topical steroids |

| 4 | M | 85 | SS | ECP | Topical steroids |

| 5 | F | 71 | SS | Gemcitabine | ECP, bexarotene, topical steroids, IFNα-2b, vorinostat, romidepsin, belinostat |

| 6 | M | 73 | SS | Pralatrexate | Romidepsin, ECP, bexarotene, topical steroids |

| 7 | F | 61 | SS | ECP, bexarotene | Topical steroids, phototherapy |

| 8 | M | 77 | SS | Romidepsin, vorinostat | ECP, NB-UVB |

| 9 | M | 70 | SS | Pralatrexate | Romidepsin, vorinostat, mechlorethamine, ECP |

| 10 | M | 71 | MF | ECP, bexarotene | NB-UVB, topical steroids |

| 11 | F | 79 | SS | ECP, bexarotene, vorinostat, INFα-2b | Topical steroids |

| 12 | F | 64 | SS | ECP, bexarotene | Topical steroids |

| 13 | F | 76 | SS | ECP | None |

| 14 | M | 61 | MF | ECP, NB-UVB | None |

| 15 | M | 67 | SS | ECP, bexarotene | None |

| 16 | F | 40 | FMF | ECP, bexarotene | NB-UVB, TSEBT |

| 17 | M | 66 | SS | ECP, bexarotene, NB-UVB, topical steroids | None |

| 18 | F | 64 | MF | ECP, bexarotene, IFNα-2b, IFNγ-1b | None |

| 19 | M | 87 | MF | ECP | MTX, bexarotene, topical steroids |

| 20 | M | 85 | MF | ECP, bexarotene, NB-UVB | Topical steroids |

| 21 | M | 70 | MF (V) | EPOCH | None |

| 22 | M | 77 | MF | ECP, bexarotene | NB-UVB, topical steroids |

| 23 | M | 52 | MF | Gemcitabine | NB-UVB, bexarotene, vorinostat, ECP, IFNα-2b, romidepsin, |

| 24 | F | 62 | MF | ECP, bexarotene, NB-UVB, mechlorethamine | Topical steroids |

| 25 | M | 62 | MF | ECP, bexarotene | Topical steroids |

ECP, extracorporeal photopheresis; EPOCH, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin; F, female; FMF, folliculotropic MF; IFN, interferon; M, male; MF, mycosis fungoides; MTX, methotrexate; NB-UVB, narrow band UV-B; PUVA, psoralen UV light A; SS, Sézary syndrome; TSEBT, total body electron beam therapy; V, visceral involvement.

CTCL patient samples show highly variable sensitivity to venetoclax in vitro

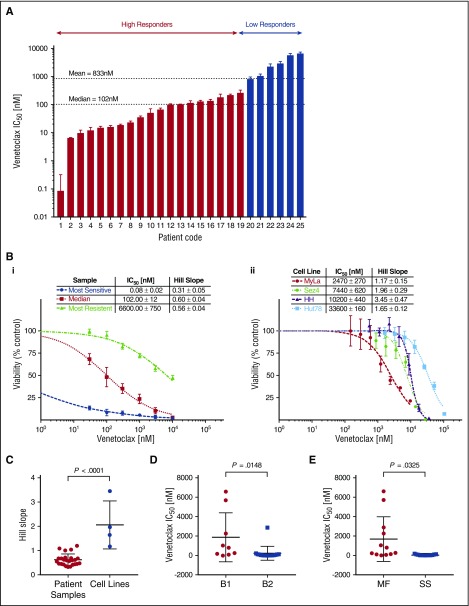

We observed the cytotoxic/cytostatic effects of venetoclax in all 25 patient samples after 72 hours of incubation as measured by the change in cell viability via media ATP quantitation. Patient samples demonstrated a wide range of sensitivities to venetoclax, with mean 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) ranging from picomolar (85 pM) to micromolar (6.6 µM) levels. The observed heterogeneity in sensitivity to venetoclax is not dissimilar to the variation observed in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL)45 or CLL.21 The most sensitive samples compare favorably to preclinical studies in B-cell lymphomas, the results of which have since been validated via clinical trial.24 To better study the significance and origins of the observed variation, we used hierarchical clustering based on their responsiveness to venetoclax to divide the tested samples into 2 groups, low and high responders. The majority of tested samples (20 of 25) were defined as high responders with a group mean IC50 of 79.0 nM compared with the low responders (5 of 25) with a group mean IC50 of 3.2 µM. Shown in Figure 1Bi are dose-response curves for 3 representative samples: the most sensitive, the median, and the most resistant sample.

Figure 1.

Cell line and patient samples demonstrate variable sensitivity to venetoclax. Isolated malignant cells from patient samples and 4 human-derived CTCL cell lines were incubated with a range of concentrations of venetoclax for 72 hours from which IC50s and Hill slopes were calculated. The median and mean IC50 for patient samples were 102 nM and 833 nM, respectively. (A) Patient samples in order of IC50. Patients were grouped into high responders and low responders using hierarchical cluster analysis. (B) Representative dose-response curves for patient samples (i) and CTCL cell lines (ii). (C) Comparison of Hill slopes between patient samples and cell lines. The difference between them would suggest distinct methods of actions. (D) Patient samples are most likely to be sensitive to venetoclax in more advanced disease. Stage based on ISCL classification.43 (E) Patient samples classified as Sézary syndrome (SS) are more likely than mycosis fungoides (MF) patients to be sensitive to venetoclax.

Four CTCL cell lines, MyLa 2059, Sez4, HH, and Hut78, were analyzed for sensitivity to venetoclax (Figure 1Bii). All 4 cell lines demonstrated relatively low sensitivity to venetoclax with IC50s of 2.47 µM, 7.4 µM 10.2 µM, and 33.6 µM, respectively. In addition to the differences in IC50, cells lines and patients were observed to have different patterns in their dose-response curves. Cell lines demonstrated a significantly higher Hill slope relative to patient samples (P < .0001), suggesting distinct mechanisms of action between cell lines and patients (Figure 1C). Among patient samples, there was a statistical trend noted between response status and Hill slope (P = .07; data not shown). Hypothesizing an association between tumor burden and increased sensitivity to induction of apoptosis via inhibition of BCL2, we compared the mean inhibitory concentration of venetoclax between patients classified as B1 vs B2 (ISCL classification),43 as well as between patients classified as MF (nonerythrodermic) vs Sézary syndrome (erythrodermic), and found a higher sensitivity in patients with more advanced disease, and in patients with Sézary syndrome (Figure 1D-E).

Baseline BCL2 mRNA expression predicts in vitro sensitivity to venetoclax

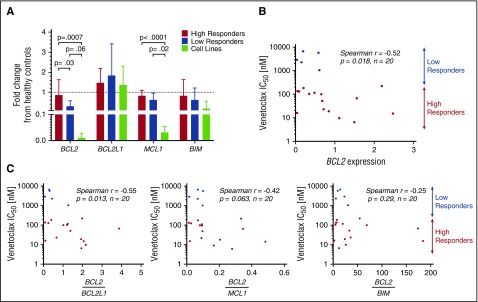

To study the differences in response to venetoclax among both primary patient samples and cell lines, the baseline genetic expression of 4 BCL2 family members was measured using quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) and expressed relative to the mean expression of the healthy controls (Figure 2A). Significant differences were noted in BCL2 expression between high and low responders as well as high responders and cell lines, whereas none were observed between low responders and cell lines. Patient samples expressed lower amounts of BCL2 than healthy controls (on average 29% less), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .19). Also notable was the similar expression of BCL2L1 (the gene encoding BCL-XL) among patient samples and cell lines, with both sets demonstrating no difference relative to the healthy controls. Significant differences were noted in the expression of BCL2L11 (the gene encoding BIM) among cell lines, with high expression noted in Hut78, and low or undetectable expression of BCL2L11 messenger RNA (mRNA) in the MyLa, Sez4, and HH lines (supplemental Figure 2A, available on the Blood Web site).

Figure 2.

Baseline gene expression of BCL2 family members and correlation to IC50. BCL2, BCL2L1, MCL1, and BCL2L11 were measured in 20 patient samples, 4 cell lines, and 3 healthy controls. Results are expressed as a fraction of the mean of the healthy controls. (A) Baseline expression of BCL2 was found to differ significantly between high responders and low responders. No difference was found between low responders and cell lines. BCL2L1 was expressed similarly among all 4 groups. Decreased MCL1 expression was noted in cell lines compared with patient samples. (B) BCL2 mRNA expression may predict response to venetoclax in vitro, with higher expression correlating to increased sensitivity. (C) Increased ratios of expression of BCL2 to BCL2L1 predicts higher sensitivity to venetoclax.

For the 20 patient samples examined, IC50 values were plotted as a function of relative expression of BCL2 member mRNA. Although a negative correlation was found between baseline expression of BCL2 and IC50 (Spearman r = −0.52; P = .018) (Figure 2B), mRNA expression of other BCL2 family members (BCL2L1, MCL1, BCL2L11, BAX) did not correlate with the IC50 values (supplemental Figure 2B). Furthermore, we examined ratios of expression of BCL2 to the other tested BCL2 family members and found that higher ratios of BCL2 to BCL2L1 correlate with greater sensitivity to venetoclax in vitro, whereas ratios of BCL2 to MCL1 and BCL2 to BCL2L11 do not (Figure 2C). These results point to the importance of both BCL2 and BCL2L1 expression, and indeed relative expression of one another, to the survival of malignant T cells. Additionally, the limited correlations of both BCL2 and the BCL2-to-BCL2L1 ratio to sensitivity suggest that a more complex relationship between BCL2 expression and inhibition of apoptosis may exist.

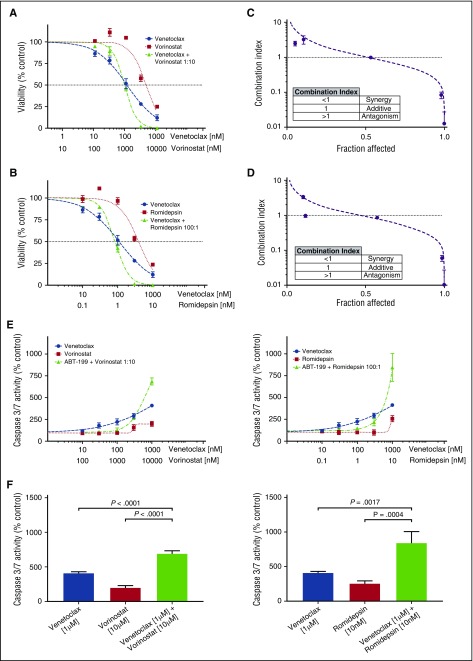

Combination inhibition of BCL2 and HDAC results in synergistic killing of CTCL cells from patient samples

Fifteen of the CTCL patient samples were tested for synergy between venetoclax and 2 HDAC inhibitors, vorinostat and romidepsin. Each of the 3 drugs was tested individually and in combination, and IC50 values and Hill slopes were calculated. From these dose-response curves, the CI was calculated using the Chou-Talalay method in Microsoft Excel, with a CI <1 indicating a synergistic interaction.46 For combinations of venetoclax with either HDAC inhibitor, synergy was observed at the higher dose range (Figure 3A-B). Ninety-three percent of tested samples demonstrated synergy of response with combinations of venetoclax and vorinostat at 10% viability (0.9 fraction affected), whereas 73% demonstrated synergy of response between venetoclax and romidepsin (Figure 3C-D; supplemental Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1). No correlation was found between either expression of BCL2 or sensitivity to venetoclax and the degree of synergy (data not shown). Additionally, no differences were found between MF patients or Sézary syndrome patients and degree of synergy, for combinations of venetoclax with either HDAC inhibitor (supplemental Figure 1Bi-ii).

Figure 3.

Combinations of venetoclax with either romidepsin or vorinostat demonstrate synergy in patient-derived cultures. (A) Viability curves for venetoclax, vorinostat, and their combination for patient 11. After 72 hours of incubation, the viability curves and the CI were calculated using the Chou-Talalay median-effect equation. Means of the quadruplicates are shown with standard deviations. (B) Viability curves for venetoclax, romidepsin, and their combination for patient 11. (C) CI and fitted curves for the combination of venetoclax and vorinostat for patient 11. (D) CI and fitted curves for the combination of venetoclax and romidepsin for patient 11. (E) Caspase-3/7 activation after 24 hours of incubation of the cell culture derived from patient 11 with venetoclax, vorinostat, romidepsin, and their combinations. All concentrations were studied in quadruplicate and plotted are the means with their respective standard deviations. (F) A significant increase in activation of caspase is seen in higher concentration combinations. Effects are similar for combinations of venetoclax with either vorinostat and romidepsin.

To investigate the mechanism of action, the induction of apoptosis at 24 hours was measured by caspase 3/7 activation. Dose-response curves were again produced for venetoclax, vorinostat, and romidepsin individually and in combination. The effect of combination therapy upon caspase 3/7 activity displayed a dose-dependent action (Figure 3E). Our measurements of caspase activation support the observations made with the cell-viability assay regarding the form of interaction between venetoclax and the HDAC inhibitors, in which there are disparate effects at low and high drug concentrations. At low doses of venetoclax and either HDAC inhibitor, antagonism was observed. In contrast, we observed a significant increase in caspase 3/7 activity with combination therapy compared with either drug alone at high doses (Figure 3F).

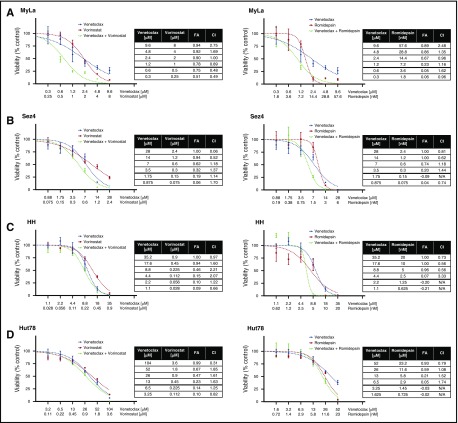

Synergy studies were similarly performed on the cell lines (Figure 4A-B). The only cell line to display significant synergy was MyLa 2059 when venetoclax was combined with vorinostat. In both the HH and Hut78 cells, venetoclax and vorinostat had antagonistic responses. In combinations of venetoclax and romidepsin, only the HH cell line demonstrated synergistic sensitivity. Unlike the response of patient cells, which are well modeled by the Hill and median-effect equations, the cell lines display significant deviations from the expected responses, especially at high doses. This may be attributed to the heterogeneity of the cell lines, which are not necessarily clonal, or to the highly cytotoxic effects of drugs such as romidepsin at higher doses.5,47 Thus, our ability to detect synergy at these dose ranges is limited.

Figure 4.

Searching for synergy in CTCL cell lines. (A-D) Four CTCL cell lines were tested for synergy between venetoclax and vorinostat, and between venetoclax and romidepsin. Cell lines were first incubated with incremental increase of each of the 3 drugs individually to calculate IC50 values. Next, cell lines were incubated with combinations of each drug in an approximate 1:1 ratio of the calculated IC50 values. Synergy was noted between venetoclax and vorinostat in the MyLa cell line and between venetoclax and with high doses of romidepsin in the HH cell line.

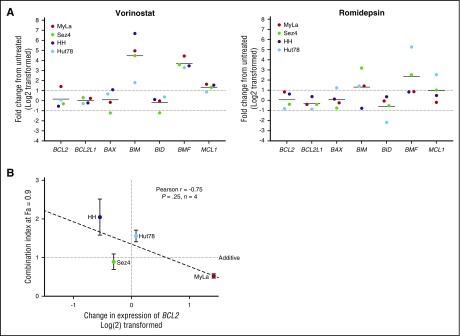

BCL2 family member expression changes in response to HDAC inhibition

To provide insight into the mechanism of action of synergy and antagonism between venetoclax and the HDAC inhibitors romidepsin and vorinostat, we incubated the 4 CTCL cell lines for 24 hours with 5 μM vorinostat or 5 nM of romidepsin before isolation of RNA and measured the relative expression of 7 BCL2 family members compared with a DMSO vehicle control via quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Figure 5A). Following exposure to vorinostat, there was a 40-fold increase in BCL2L11 expression and a 12-fold increase in BMF expression. The dramatic increase in BCL2L11 mRNA is critical to the function of BCL2, which acts to inhibit apoptosis via direct binding to BIM. This shift in balance toward proapoptotic factors is not only 1 of the methods of action of vorinostat, but sheds light on interactions between venetoclax and HDAC inhibition. Furthermore, we were able to detect a statistically significant trend between the change in expression of BCL2 in response to vorinostat and the calculated CI at a fraction affected of 0.9 (Figure 5B). MyLa, the only cell line in which BCL2 expression was increased, was the only cell line to demonstrate significant synergy. Romidepsin caused a 13-fold increase in BMF and fourfold increase in BCL2L11 expression. No significant changes in expression of BCL2 were noted following exposure to romidepsin in any of the 3 cell lines.

Figure 5.

Changes in genetic expression of BCL2 family members following incubation with vorinostat or romidepsin. (A) Significant changes include the increased expression of BCL2L11, BMF, and MCL1. Notable is the 2.7-fold increase in BCL2 expression in the MyLa cell line with vorinostat. (B) The amount of calculated synergy, represented by the CI at 0.9 fraction affected (10% viability), was correlated to change in expression of venetoclax after 24 hours of incubation with 5 µM vorinostat, a strong correlation was noted, but only limited conclusions can be drawn, due to the small sample size.

Discussion

Guided by recent studies6,7,48-51 that suggest that increased resistance to apoptosis in CTCL is at least partly due to gene alterations that may increase the transcription of BCL2, and encouraged by the success of venetoclax in the treatment of CLL,52 we sought in this study to explore the potential of venetoclax for the treatment of CTCL. We identified a group of patients, the high responders, with exquisite sensitivity to venetoclax at a mean IC50 of 79.0 nM. This range is comparable to the range of sensitivities, <300 nM previously observed in BCL2-dependent immature CD4−CD8− T-ALL subtypes. Three clinical trials53-55 investigating the treatment of CLL and NHL found the maximum plasma concentrations for 400 mg, 800 mg, and 1200 mg to be 2.2 µM, 3.5 µM, and 4.0 µM. These values far exceeded the in vitro mean inhibitory concentrations observed in our study. We are further encouraged as the maximum tolerated dose of venetoclax has not yet been well established, necessitating dose escalation beyond 1200 mg.56,57 Indeed, the most significant adverse events in the trials for CLL were deaths due to tumor lysis syndrome.58

Having established the response of primary patient samples to venetoclax in vitro, we next searched for a biological assay that would predict sensitivity and distinguish high responders from low responders. BCL2 protein and mRNA expression have been found to have an inverse relationship with sensitivity to venetoclax in vitro CLL,59 NHL,21 and T-ALL.45 Our data indicate that a similar relationship exists in CTCL, additionally supported by the significant difference in expression of BCL2 among high and low responders. Other work has shown that expression of BCL2L1 and MCL1 contributes to resistance to venetoclax,24,34,36,60 but our work suggests that higher expression of either at baseline does not correlate with sensitivity in the patient samples tested.

Previous work45,61,62 with T-ALL has identified a wide variation in response to venetoclax among cell lines and primary patient samples, wherein T-ALL cells displaying the immature phenotypes CD4−CD8−, such as LOUCY cell line, exhibit BCL2 dependence, and correspondingly submicromolar sensitivity in vitro to venetoclax. In contrast, cell lines with mature phenotypes demonstrate dependency for survival on the protein BCL-XL, and decreased sensitivity to venetoclax with >1 μM IC50 values. CTCL itself has been characterized by TCR sequencing63 as a disease derivative of mature memory T cells, from which one would predict dependency on BCL-XL. Direct measurements of mitochondrial membrane depolarization64,65 have highlighted the stark differences in responses to BH3 mimetics between BCL2 and BCL-XL survival-dependent cells. A recent study66 looked at the BH3 profiles of T-cell lymphoma cell lines, including 2 examined in our study, MyLa and Hut78. The 2 cell lines were identified as BCL-XL dependent, which was confirmed in our study, as we measured similar expression of BCL2L1 in all 3 cells as well as significantly decreased expression of BCL2 and MCL1, relative to normal controls. These findings, along with our observation of poor sensitivity of the 3 cell lines to the BCL2-selective inhibitor venetoclax, suggest that some CTCL cases are BCL-XL dependent. This interplay of BCL2 and BCL-XL was additionally significant in primary patient samples where the majority of samples had higher expression of BCL2 than BCL2L1, and a larger ratio predicted of sensitivity to venetoclax.

Synergy has been described between BCL2 inhibitors with a number of different therapies and in numerous malignancies.26,27,45,61,67-70 Here, we show evidence of synergy between venetoclax and 2 HDAC inhibitors, vorinostat and romidepsin. Synergy was consistently observed at the higher dose ranges of either HDAC inhibitor indicating a dose-dependent mechanism. Not only did we detect antagonism at low doses, but there was some evidence of direct inhibition of caspase 3/7 activity with administration of either HDAC inhibitor alone. This is consistent with reports on both romidepsin30 and vorinostat,71 which showed the effects of either drug differ dramatically at low and high dose, including 1 study where romidepsin was found to inhibit the production of reactive oxygen species at low doses.32

The lack of synergy observed in the CTCL cell lines suggests, perhaps unsurprisingly, that expression of and dependence on BCL2 is required for synergistic interactions with other therapies. Although in the cell lines the observed synergy can be linked directly to changes in BCL2 expression, the preferential effect observed with vorinostat and venetoclax is likely due to the greater degree of change in the expression of BCL2L11. Dissociation of BCL2-BIM complexes has been implicated as the primary mechanism of induction of apoptosis by venetoclax and other BCL2 inhibitors.21,46,68 The low baseline expression of BCL2L11 in the HH and MyLa cell lines further supports the proposed theory that change in expression of BCL2L11 is critical to apoptosis by romidepsin, whereas baseline expression is nonessential to therapeutic effects.72,73

In summary, this study supports the clinical implementation of venetoclax as a novel therapy for leukemic CTCL, and further demonstrates a synergistic effect when venetoclax is combined with the HDAC inhibitors romidepsin and vorinostat. The potential for an effective combination oral therapy with venetoclax and vorinostat is also intriguing. Further clinical trials are planned to explore this potential synergy in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Drs Martin & Dorothy Spatz Charitable Foundation (M.G.); the Yale Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Skin Cancer (National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute 1P50CA121974) (M.G.); the Leon Rosenberg, MD Medical Student Research Fund in Genetics (B.M.C.); and the Taylor Opportunity Student Research Fellowship (B.M.C.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: B.M.C., J.G.W., J.M.L., and M.G. designed experiments; B.M.C. and M.G. analyzed the data, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript; B.M.C., J.G.W., and F.N.M. performed experiments; M.G., F.M.F., and K.R.C. provided patient samples; B.M.C., J.M.L., and M.G. participated in discussions of the data; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael Girardi, Yale University School of Medicine, PO Box 208059, 333 Cedar St, New Haven, CT 06520-8059; e-mail: michael.girardi@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Girardi M, Heald PW, Wilson LD. The pathogenesis of mycosis fungoides. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1978-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arulogun SO, Prince HM, Ng J, et al. . Long-term outcomes of patients with advanced-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and large cell transformation. Blood. 2008;112(8):3082-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. . Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4730-4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lechowicz MJ, Lazarus HM, Carreras J, et al. . Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(11):1360-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rozati S, Cheng PF, Widmer DS, Fujii K, Levesque MP, Dummer R. Romidepsin and azacitidine synergize in their epigenetic modulatory effects to induce apoptosis in CTCL. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(8):2020-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi J, Goh G, Walradt T, et al. . Genomic landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):1011-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ungewickell A, Bhaduri A, Rios E, et al. . Genomic analysis of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome identifies recurrent alterations in TNFR2. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):1056-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGirt LY, Jia P, Baerenwald DA, et al. . Whole-genome sequencing reveals oncogenic mutations in mycosis fungoides. Blood. 2015;126(4):508-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Silva Almeida AC, Abate F, Khiabanian H, et al. . The mutational landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma and Sézary syndrome. Nat Genet. 2015;47(12):1465-1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litvinov IV, Netchiporouk E, Cordeiro B, et al. . The use of transcriptional profiling to improve personalized diagnosis and management of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(12):2820-2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kola I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(8):711-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weed J, Gibson J, Lewis J, et al. . FISH panel for leukemic CTCL. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(3):751-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharya S, Ray RM, Johnson LR. STAT3-mediated transcription of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and c-IAP2 prevents apoptosis in polyamine-depleted cells. Biochem J. 2005;392(Pt 2):335-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekulic A, Liang WS, Tembe W, et al. . Personalized treatment of Sézary syndrome by targeting a novel CTLA4:CD28 fusion. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2015;3(2):130-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung JT, Kim DH, Kwak EK, et al. . Clinical role of Bcl-2, Bax, or p53 overexpression in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Ann Hematol. 2006;85(9):575-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22(23):3099-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen M, Kaestel CG, Eriksen KW, et al. . Inhibition of constitutively activated Stat3 correlates with altered Bcl-2/Bax expression and induction of apoptosis in mycosis fungoides tumor cells. Leukemia. 1999;13(5):735-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindahl LM, Fredholm S, Joseph C, et al. . STAT5 induces miR-21 expression in cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(29):45730-45744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin JZ, Zhang CL, Kamarashev J, Dummer R, Burg G, Döbbeling U. Interleukin-7 and interleukin-15 regulate the expression of the bcl-2 and c-myb genes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells. Blood. 2001;98(9):2778-2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong J, Zhao Y-P, Zhou L, Zhang T-P, Chen G. Bcl-2 upregulation induced by miR-21 via a direct interaction is associated with apoptosis and chemoresistance in MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells. Arch Med Res. 2011;42(1):8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, et al. . ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med. 2013;19(2):202-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant D, Kluck RM Bcl-2 family-regulated apoptosis in health and disease. Cell Health Cytoskeleton. 2010;2(1):9-22.

- 23.Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, et al. . Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122(6):927-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cang S, Iragavarapu C, Savooji J, Song Y, Liu D. ABT-199 (venetoclax) and BCL-2 inhibitors in clinical development. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Fiskus W, Eaton K, et al. . Cotreatment with BCL-2 antagonist sensitizes cutaneous T-cell lymphoma to lethal action of HDAC7-Nur77-based mechanism. Blood. 2009;113(17):4038-4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xargay-Torrent S, López-Guerra M, Saborit-Villarroya I, et al. . Vorinostat-induced apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma is mediated by acetylation of proapoptotic BH3-only gene promoters. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(12):3956-3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berghauser Pont LME, Spoor JKH, Venkatesan S, et al. . The Bcl-2 inhibitor obatoclax overcomes resistance to histone deacetylase inhibitors SAHA and LBH589 as radiosensitizers in patient-derived glioblastoma stem-like cells. Genes Cancer. 2014;5(11-12):445-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prince HM, Dickinson M. Romidepsin for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(13):3509-3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piekarz RL, Robey RW, Zhan Z, et al. . T-cell lymphoma as a model for the use of histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy: impact of depsipeptide on molecular markers, therapeutic targets, and mechanisms of resistance. Blood. 2004;103(12):4636-4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newbold A, Lindemann RK, Cluse LA, Whitecross KF, Dear AE, Johnstone RW. Characterisation of the novel apoptotic and therapeutic activities of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(5):1066-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duvic M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33(4):757-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valdez BC, Brammer JE, Li Y, et al. . Romidepsin targets multiple survival signaling pathways in malignant T cells. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(10):e357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bates SE, Eisch R, Ling A, et al. . Romidepsin in peripheral and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: mechanistic implications from clinical and correlative data. Br J Haematol. 2015;170(1):96-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhary GS, Al-Harbi S, Mazumder S, et al. . MCL-1 and BCL-xL-dependent resistance to the BCL-2 inhibitor ABT-199 can be overcome by preventing PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation in lymphoid malignancies. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(1):e1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips DC, Xiao Y, Lam LT, et al. . Loss in MCL-1 function sensitizes non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cell lines to the BCL-2-selective inhibitor venetoclax (ABT-199). Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(11):e368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bodo J, Zhao X, Smith MR, Hsi ED. Activity of ABT-199 and acquired resistance in follicular lymphoma cells [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21). Abstract 3635. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaltoft K, Bisballe S, Dyrberg T, Boel E, Rasmussen PB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Establishment of two continuous T-cell strains from a single plaque of a patient with mycosis fungoides. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1992;28A(3 Pt 1):161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrams JT, Lessin S, Ghosh SK, et al. . A clonal CD4-positive T-cell line established from the blood of a patient with Sézary syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96(1):31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Starkebaum G, Loughran TP Jr, Waters CA, Ruscetti FW. Establishment of an IL-2 independent, human T-cell line possessing only the p70 IL-2 receptor. Int J Cancer. 1991;49(2):246-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gazdar AF, Carney DN, Bunn PA, et al. . Mitogen requirements for the in vitro propagation of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Blood. 1980;55(3):409-417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ward JH. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc. 1963;58(301):236-244. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chou T-C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(3):621-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, et al. ; ISCL/EORTC. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110(6):1713-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson JF, Huang J, Liu KJ, et al. . Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL): current practices in blood assessment and the utility of T-cell receptor (TCR)-Vβ chain restriction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):870-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peirs S, Matthijssens F, Goossens S, et al. . ABT-199 mediated inhibition of BCL-2 as a novel therapeutic strategy in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124(25):3738-3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chou T-C. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):440-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Itoh Y, Suzuki T, Miyata N. Small-molecular modulators of cancer-associated epigenetic mechanisms. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9(5):873-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee CS, Ungewickell A, Bhaduri A, et al. . Transcriptome sequencing in Sezary syndrome identifies Sezary cell and mycosis fungoides-associated lncRNAs and novel transcripts. Blood. 2012;120(16):3288-3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kari L, Loboda A, Nebozhyn M, et al. . Classification and prediction of survival in patients with the leukemic phase of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2003;197(11):1477-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Doorn R, Dijkman R, Vermeer MH, et al. . Aberrant expression of the tyrosine kinase receptor EphA4 and the transcription factor twist in Sézary syndrome identified by gene expression analysis. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5578-5586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pomerantz RG, Mirvish ED, Erdos G, Falo LD Jr, Geskin LJ. Novel approach to gene expression profiling in Sézary syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(5):1090-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts AW, Seymour JF, Brown JR, et al. . Substantial susceptibility of chronic lymphocytic leukemia to BCL2 inhibition: results of a phase I study of navitoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory disease. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):488-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salem AH, Agarwal SK, Dunbar M, Enschede SL, Humerickhouse RA, Wong SL. Pharmacokinetics of venetoclax, a novel BCL-2 inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(4):484-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. . Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):311-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seymour JF, Ma S, Brander DM, et al. Venetoclax plus rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(2):230-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Davids MS, Roberts AW, Anderson MA, et al. . The BCL-2-specific BH3-mimetic ABT-199 (GDC-0199) is active and well-tolerated in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma: interim results of a phase I study [abstract]. Blood. 2015;120(21). Abstract 304. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davids MS, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, et al. . Phase I first-in-human study of venetoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):826-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davids MS, Pagel JM, Kahl BS, et al. . Bcl-2 inhibitor ABT-199 (GDC-0199) monotherapy shows anti-tumor activity including complete remissions in high-risk relapsed/refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) [abstract]. Blood. 2013;122(21). Abstract 872. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Itchaki G, Brown JR. The potential of venetoclax (ABT-199) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016;7(5):270-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khaw SL, Mérino D, Anderson MA, et al. . Both leukaemic and normal peripheral B lymphoid cells are highly sensitive to the selective pharmacological inhibition of prosurvival Bcl-2 with ABT-199. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1207-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson NM, Harrold I, Mansour MR, et al. . BCL2-specific inhibitor ABT-199 synergizes strongly with cytarabine against the early immature LOUCY cell line but not more-differentiated T-ALL cell lines. Leukemia. 2014;28(5):1145-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chonghaile TN, Roderick JE, Glenfield C, et al. . Maturation stage of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia determines BCL-2 versus BCL-XL dependence and sensitivity to ABT-199. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(9):1074-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kirsch IR, Watanabe R, O’Malley JT, et al. . TCR sequencing facilitates diagnosis and identifies mature T cells as the cell of origin in CTCL. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(308):308ra158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Del Gaizo Moore V, Letai A. BH3 profiling--measuring integrated function of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway to predict cell fate decisions. Cancer Lett. 2013;332(2):202-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hogdal L, Chyla B, McKeegan E, et al. . BH3 profiling predicts clinical response in a phase II clinical trial of ABT-199 (GDC-0199) in acute myeloid leukemia [abstract]. Cancer Res. 2015;75(suppl 15). Abstract 2834. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koch R, Brem E, Clark R, et al. . A functional characterization of BCL2-family members identifies BH3 mimetics as potential therapeutics in T-cell lymphomas [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128(22). Abstract 292. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abed MN, Abdullah MI, Richardson A. Antagonism of Bcl-XL is necessary for synergy between carboplatin and BH3 mimetics in ovarian cancer cells. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mason KD, Khaw SL, Rayeroux KC, et al. . The BH3 mimetic compound, ABT-737, synergizes with a range of cytotoxic chemotherapy agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(11):2034-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ellis L, Pan Y, Smyth GK, et al. . Histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat induces clinical responses with associated alterations in gene expression profiles in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(14):4500-4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao J, Niu X, Li X, et al. . Inhibition of CHK1 enhances cell death induced by the Bcl-2-selective inhibitor ABT-199 in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(23):34785-34799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petruccelli LA, Dupéré-Richer D, Pettersson F, Retrouvey H, Skoulikas S, Miller WH Jr. Vorinostat induces reactive oxygen species and DNA damage in acute myeloid leukemia cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang Y, Zhao Y, Liao W, et al. . Acetylation of FoxO1 activates Bim expression to induce apoptosis in response to histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide treatment. Neoplasia. 2009;11(4):313-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chakraborty AR, Robey RW, Luchenko VL, et al. . MAPK pathway activation leads to Bim loss and histone deacetylase inhibitor resistance: rationale to combine romidepsin with an MEK inhibitor. Blood. 2013;121(20):4115-4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]