Abstract

Background

All major Hispanic/Latino groups in the United States have a high prevalence of obesity, which is often severe. Little is known about cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors among those at very high levels of body mass index (BMI).

Methods and Results

Among US Hispanic men (N=6547) and women (N=9797), we described gradients across the range of BMI and age in CVD risk factors including hypertension, serum lipids, diabetes, and C‐reactive protein. Sex differences in CVD risk factor prevalences were determined at each level of BMI, after adjustment for age and other demographic and socioeconomic variables. Among those with class II or III obesity (BMI ≥35 kg/m2, 18% women and 12% men), prevalences of hypertension, diabetes, low high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level, and high C‐reactive protein level approached or exceeded 40% during the fourth decade of life. While women had a higher prevalence of class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) than did men (7% and 4%, respectively), within this highest BMI category there was a >50% greater relative prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in men versus women, while sex differences in prevalence of these CVD risk factors were ≈20% or less at other BMI levels.

Conclusions

Elevated BMI is common in Hispanic/Latino adults and is associated with a considerable excess of CVD risk factors. At the highest BMI levels, CVD risk factors often emerge in the earliest decades of adulthood and they affect men more often than women.

Keywords: BMI, CVD risk factor, Hispanic/Latino, sex

Subject Categories: ,

Introduction

Obesity has risen in prevalence in the United States over time and has become increasingly severe, particularly in Hispanics/Latinos, who make up a large share of the US population.1, 2, 3 All of the largest Hispanic/Latino groups in the United States, including those of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban background, have a high prevalence of obesity.1, 2, 3, 4 Risks of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and mortality increase progressively at levels of body mass index (BMI) far beyond the commonly used clinical thresholds used to define overweight and obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively).5 There may be sex differences in the relationship between BMI and risk of CVD, which would have clinical implications for the use of BMI cut points to define the level of CVD risk. For instance, among 221 934 persons in the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke associated with BMI was significantly larger in men (HR per 1 SD higher BMI=1.33) than in women (HR per 1 SD higher BMI=1.20, P for interaction by sex=0.030), whereas the association between BMI and incident coronary heart disease events did not differ by sex (P for interaction=0.643).6

To date, obesity‐related risk factors for CVD have not been well studied in Hispanic/Latino adults, who, as a group, have not only a high prevalence of obesity but also a predisposition to obesity‐related disorders such as diabetes and low high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C). We used the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) cohort of >16 000 persons 18 to 74 years old to make comparisons between men and women in the prevalence of high BMI and in the BMI‐specific prevalence of CVD risk factors. Unusual features of the study include a diverse population‐based sample of Hispanic/Latino individuals, inclusion of persons across a wide spectrum of age, and large sample size with nearly 1000 individuals who met World Health Organization criteria for severe obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2, also known as class III obesity).

Methods

Participants

HCHS/SOL is a study of 16 415 men and women recruited during 2008–2011 in Bronx, NY, Chicago, IL, Miami, FL, and San Diego, CA.7, 8 Within recruitment areas delineated in each community, participants were identified and recruited by sampling census block groups, households, and household residents using a stratified multistage area probability sampling approach. Eligible persons were community‐dwelling adults who were 18 to 74 years old at the time of screening, who self‐identified as Hispanic or Latino, who were not pregnant or on active military duty, and who did not plan to move from the study area in the near future. Sampling methods were designed to yield a study‐wide cohort of ≈6000 participants aged 18 to 44 years and ≈10 000 participants aged 45 to 74 years. Of screened individuals who were eligible, 41.7% were enrolled. This study was approved by field center institutional review boards, and subjects gave informed consent.

Data Collection

Study examinations included clinical measurements, questionnaires, and venous blood specimens collected at fasting and again after a 75‐g glucose load. Measurements of lipids, glucose, C‐reactive protein (CRP), and hemoglobin A1c had laboratory coefficients of variation between 0.8% and 4.7%.

Variable Definition

Self‐report was used to define smoking, alcohol use, place of birth and family national background, medical history, and socioeconomic status by using standardized instruments. Total physical activity at work, travel, and leisure was measured using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) developed by the World Health Organization. GPAQ scores for exercise intensity and type was created following the World Health Organization guidelines (http://www.who.int/chp/steps/en/). Medication use was ascertained by conducting an inventory of all currently used medications. BMI was calculated as measured weight in kilograms (Tanita Body Composition Analyzer, TBF 300A) divided by the square of measured height in meters (SECA 222; Perspective Enterprises, Inc). BMI categories were underweight, <18.5 kg/m2; normal‐weight, ≥18.5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2; overweight, ≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2; class I obesity, ≥30 kg/m2 and <35 kg/m2; class II obesity, ≥35 kg/m2 and <40 kg/m2; and class III obesity, ≥40 kg/m2. Blood pressures were defined as the average of the second and third of 3 repeat seated measurements obtained after a 5‐minute rest (Omron HEM‐907 XL). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose of ≥126 mg/dL, 2‐hour postload glucose levels of ≥200 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c level of ≥6.5%, or use of antidiabetic medication. High low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) was defined as (calculated) LDL‐C of ≥160 mg/dL or statin use. We used cut points of <40 mg/dL to define low HDL‐C and ≥200 mg/dL to define hypertriglyceridemia. Additional analyses were conducted with a cut point of 50 mg/dL used to define low HDL‐C level in women. High CRP level was defined as 3 to 10 mg/L, with levels >10 mg/L excluded from analyses.9

Statistical Analyses

To obtain accurate population estimates of the prevalences of BMI and CVD risk factors, we calculated non–response‐adjusted, trimmed, and calibrated sampling weights. The sampling weights were calibrated to local age, sex, and Hispanic/Latino background distributions in the 2010 US Census and were normalized to the overall study cohort. Individuals with missing BMI values (n=71) were excluded. We examined the prevalence of BMI categories by age group and sex, as well as the distribution of CVD risk factors across sex‐specific BMI categories. The Cochran–Armitage test was used to test for trend in cross‐tabulations between BMI category and age group. The age‐adjusted distribution of CVD risk factors by BMI categories was estimated using survey logistic regression with predicted marginals, adjusting each BMI level to the age distribution of the target population of Hispanics/Latinos in the 4 HCHS/SOL communities. After assigning to each individual within a given BMI category the median within‐category BMI value, we tested for linear trend in prevalence of risk factors across BMI categories using survey logistic regression procedures in SUDAAN. We used additional models using squared terms to test for nonlinear associations between BMI category and risk factor prevalence. In further analyses, we plotted smoothed curves displaying the age‐specific prevalence of CVD risk factors within the normal‐weight, overweight, class I obese, and class II or III (combined) obese groups by using local polynomials estimation using the svysmooth procedure with a bandwidth of 20 in the R statistical program. At each level of BMI, we estimated the prevalence ratio (PR) for major CVD risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, unfavorable lipid levels, and high CRP level) comparing men versus women, again using survey logistic regression with predicted marginals. These analyses were adjusted for age, education, health insurance status, field center, national background (Mexican, Cuban, etc.), nativity, smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity. In sensitivity analyses, we found that differences in CVD risk factor prevalence between men and women within the highest BMI category (≥40 kg/m2) were similar when we excluded individuals with BMI >45 kg/m2. Results were also similar when we adjusted for residual differences within BMI category in distribution of BMI levels between men and women. We tested for evidence of effect modification by major national background group for the sex differences described in Table 3. This was done through inclusion of sex×background interaction terms, and the test for the interaction terms was conducted at a 0.05 significance level. All statistical analyses took into account the survey design and survey weights. Analyses used SUDAAN version 11 (RTI International), SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute), and R version 2.14.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Table 3.

Adjusted Sex Prevalence Ratio (Men Versus Reference Group of Women) for Presence of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors, Within Categories of Body Mass Index, Among Participants in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL)

| BMI Class | Hypertension | Diabetes | High LDL‐C Level | Low HDL‐C Levela | Low HDL‐C Levelb | High Triglyceride Level | High C‐Reactive Protein Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| Normal weight | 1.17 | 0.96 to 1.43 | 1.28 | 0.90 to 1.80 | 0.92 | 0.72 to 1.18 | 2.51 | 1.94 to 3.26 | 0.61 | 0.51 to 0.72 | 1.82 | 1.18 to 2.80 | 0.66 | 0.48 to 0.92 |

| Overweight | 1.21 | 1.07 to 1.36 | 1.23 | 1.03 to 1.48 | 1.10 | 0.97 to 1.25 | 2.72 | 2.29 to 3.23 | 0.74 | 0.67 to 0.82 | 2.03 | 1.69 to 2.44 | 0.53 | 0.46 to 0.60 |

| Obese I | 1.18 | 1.04 to 1.34 | 0.92 | 0.78 to 1.07 | 1.19 | 1.00 to 1.43 | 2.17 | 1.83 to 2.58 | 0.86 | 0.77 to 0.95 | 2.14 | 1.79 to 2.57 | 0.64 | 0.56 to 0.73 |

| Obese II | 1.30 | 1.09 to 1.55 | 1.23 | 1.00 to 1.52 | 1.18 | 0.92 to 1.51 | 2.31 | 1.84 to 2.89 | 0.79 | 0.68 to 0.91 | 1.75 | 1.26 to 2.42 | 0.68 | 0.58 to 0.79 |

| Obese III | 1.58 | 1.30 to 1.92 | 1.50 | 1.16 to 1.94 | 1.82 | 1.29 to 2.56 | 2.05 | 1.58 to 2.66 | 0.72 | 0.60 to 0.86 | 2.15 | 1.41 to 3.27 | 0.85 | 0.73 to 0.99 |

Body mass index categories were normal weight, ≥18.5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2; overweight, ≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2; class I obesity, ≥30 kg/m2 and <35 kg/m2; class II obesity, ≥35 kg/m2 and <40 kg/m2; and class III obesity, ≥40 kg/m2. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure was greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose of 126 mg/dL or higher, 2‐hour cholesterol level was defined as 160 mg/dL or higher, or statin use. Low high‐density lipoprotein level was defined a >40 mg/dL in both men and women, or alternatively as <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women (sex‐specific threshold). Hypertriglyceridemia was defined as ≥200 mg/dL. High C‐reactive protein level was defined as 3 to 10 mg/dL, with exclusion of individuals with C‐reactive protein levels above 10 mg/L. Prevalence ratio was adjusted for age, level of education, current health insurance status, field center, national background, nativity, smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity. Women represent the reference group for PR estimates. BMI indicates body mass index; HDL‐C, High‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; PR, prevalence ratio.

Uniform threshold in men and women.

Sex‐specific threshold.

Results

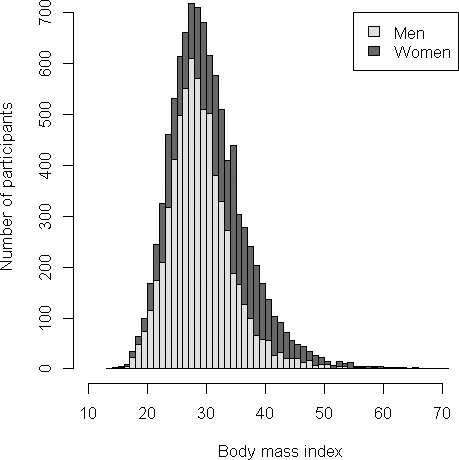

BMI measures were available from 6547 Hispanic/Latino men (mean age 40.2 years, SD 14.8 years) and 9797 Hispanic/Latino women (mean age 41.8 years, SD 15.1 years) (Figure 1). The largest group was of Mexican background (37%), followed by persons of Cuban (20%), Puerto Rican (16%), Dominican (10%), and Central or South American, other, or multiple backgrounds (combined prevalence 17%). Approximately one‐third (34%) had less than a high school education, 39% reported at least some college education, 46% reported an annual household income of ≤$20 000, and 20% reported income >$40 000.

Figure 1.

Distribution of body mass index among men and women among participants in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Light gray bars represent N=6547 men. Dark gray bars represent N=9797 women. Among men, N (%) with normal weight N=1326 (22%), overweight N=2739 (41%), class I obesity N=1667 (25%), class II obesity N=516 (8%), and class III obesity N=248 (4%). Among women, N (%) with normal weight N=1865 (22%), overweight N=3377 (34%), class I obesity N=2552 (24%), class II obesity N=1192 (11%), and class III obesity N=732 (7%). Minimum and maximum body mass index values were 14.9 and 62.2 among women and 13.8 and 70.3 among men.

Prevalence and Correlates of Elevated BMI

Figure 1 shows the distribution of BMI levels. Among both men and women, 22% had BMI in the normal range of 18.5 to 25 kg/m2. The proportion in the overweight range (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2) was 41% among men and 34% among women. Men were less likely than women to have BMI in the obesity range (BMI ≥30 kg/m2, 37% among men and 42% among women). Men were also less likely to meet criteria for class II obesity (BMI ≥35 kg/m2 and <40 kg/m2, 8% among men and 11% among women) and class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2, 4% among men and 7% among women).

The distribution of subjects across BMI categories within age groups differed between men and women (Table 1). Among both men and women, the 18‐ to 24‐year‐old age group had the highest prevalence of normal weight. Among men, the 35‐ to 44‐year‐old age group had the lowest prevalence of normal weight (12%), while among women the prevalence of normal weight decreased progressively across all age groups, reaching the lowest prevalence among the oldest group of 65‐ to 74‐year‐old women (12% normal weight). The highest BMI category, class III obesity, was more common among men aged between 18 and 54 years with 4% to 5% prevalence, compared with 2% among men aged ≥55 years. Among women, the 25‐ to 34‐year‐old age group had the highest prevalence of BMI in the class III obesity range (9%). Average levels of all CVD risk factors tended to worsen with higher level of BMI (Table 2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Body Mass Index Categories Within Age Group Among Participants in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL)

| Age Group, y, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 24 | 25 to 34 | 35 to 44 | 45 to 54 | 55 to 64 | ≥65 | P trend | |

| Men (n=6547) | |||||||

| Underweight | 25 (3) | 1 (0) | 6 (1) | 5 (0) | 13 (1) | 1 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Normal weight | 314 (39) | 223 (24) | 150 (12) | 299 (17) | 242 (18) | 98 (20) | <0.0001 |

| Overweight | 218 (28) | 377 (41) | 501 (43) | 838 (46) | 576 (44) | 229 (46) | <0.0001 |

| Obese class I | 140 (20) | 221 (22) | 337 (30) | 490 (26) | 352 (29) | 127 (25) | <0.0001 |

| Obese class II | 54 (6) | 79 (8) | 118 (10) | 149 (7) | 87 (6) | 29 (7) | 0.9846 |

| Obese class III | 34 (4) | 39 (5) | 51 (4) | 85 (4) | 27 (2) | 12 (2) | 0.0046 |

| Women (n=9797) | |||||||

| Underweight | 37 (5) | 12 (1) | 8 (0) | 10 (0) | 7 (1) | 5 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Normal weight | 362 (43) | 280 (26) | 350 (19) | 469 (16) | 305 (14) | 99 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Overweight | 218 (25) | 374 (33) | 631 (37) | 1075 (35) | 758 (37) | 321 (40) | <0.0001 |

| Obese class I | 146 (15) | 246 (21) | 435 (25) | 840 (28) | 627 (27) | 258 (31) | <0.0001 |

| Obese class II | 64 (7) | 109 (10) | 196 (11) | 434 (14) | 287 (14) | 102 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Obese class III | 49 (5) | 108 (9) | 158 (8) | 218 (7) | 158 (8) | 41 (6) | 0.4778 |

P trend calculated using Cochran–Armitage test. Body mass index categories were underweight, <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight, ≥18.5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2; overweight, ≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2; class I obesity, ≥30 kg/m2 and <35 kg/m2; class II obesity, ≥35 kg/m2 and <40 kg/m2; and class III obesity, ≥40 kg/m2.

Table 2.

Age‐Adjusted Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors by Body Mass Index Category, Among Men and Women in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL)

| BMI class | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Weight, n=1326 (22%) | Overweight, n=2739 (41%) | Class I Obese, n=1667 (25%) | Class II Obese, n=516 (8%) | Class III Obese, n=248 (4%) | |

| Meana (95% CI) | |||||

| Men | |||||

| Age, yb | 36 (35 to 37) | 42 (41 to 43) | 42 (41 to 43) | 40 (39 to 42) | 37 (35 to 39) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 121 (120 to 122) | 123 (123 to 124) | 125 (124 to 126) | 127 (126 to 129) | 127 (125 to 130) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 69 (69 to 70) | 73 (72 to 73) | 76 (75 to 77) | 78 (77 to 80) | 82 (79 to 84) |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 114 (111 to 117) | 124 (122 to 125) | 125 (122 to 128) | 121 (118 to 125) | 116 (111 to 121) |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 50 (49 to 51) | 45 (44 to 46) | 42 (41 to 42) | 40 (39 to 42) | 40 (39 to 42) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 186 (183 to 189) | 197 (195 to 199) | 200 (197 to 203) | 193 (189 to 197) | 188 (182 to 194) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 115 (108 to 122) | 146 (140 to 151) | 177 (165 to 189) | 162 (152 to 172) | 160 (149 to 172) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 101 (99 to 102) | 103 (102 to 105) | 106 (104 to 108) | 110 (106 to 114) | 122 (114 to 131) |

| 2‐hour glucose, mg/dL | 104 (101 to 106) | 111 (109 to 113) | 120 (118 to 122) | 128 (123 to 133) | 128 (120 to 135) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.6 (5.6 to 5.7) | 5.7 (5.6 to 5.8) | 5.8 (5.7 to 5.9) | 6.1 (5.9 to 6.2) | 6.5 (6.3 to 6.7) |

| C‐reactive protein, g/L | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | 2.6 (2.5 to 2.8) | 3.5 (3.3 to 3.8) | 4.4 (4.0 to 4.9) |

| No. (%) | |||||

| Nativity | |||||

| Within 50 states | 296 (23) | 393 (22) | 294 (26) | 143 (33) | 110 (48) |

| Outside of 50 states | 1025 (77) | 2340 (78) | 1366 (74) | 372 (67) | 137 (52) |

| Less than high school education | 482 (33) | 1053 (32) | 614 (31) | 177 (33) | 68 (25) |

| Income | |||||

| ≤$40 000 | 930 (43) | 2024 (41) | 1224 (39) | 362 (40) | 167 (37) |

| $40 001 to $75 000 | 180 (50) | 419 (50) | 248 (53) | 89 (52) | 48 (56) |

| >$75 000 | 70 (7) | 141 (8) | 99 (8) | 35 (8) | 18 (7) |

|

Normal Weight, n=1865 (22%) |

Overweight, n=3377 (34%) |

Class I Obese, n=2552 (24%) |

Class II Obese, n=1192 (11%) |

Class III Obese, n=732 (7%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meana (95% CI) | |||||

| Women | |||||

| Age, yb | 36 (35 to 37) | 43 (43 to 44) | 45 (44 to 46) | 44 (43 to 46) | 42 (39 to 44) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 114 (113 to 115) | 117 (116 to 118) | 118 (117 to 119) | 119 (118 to 121) | 118 (116 to 119) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 67 (66 to 67) | 70 (70 to 71) | 73 (72 to 73) | 76 (75 to 77) | 76 (75 to 77) |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 114 (112 to 116) | 121 (119 to 123) | 120 (118 to 122) | 117 (114 to 119) | 119 (115 to 123) |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 58 (57 to 59) | 52 (51 to 53) | 49 (49 to 50) | 48 (47 to 49) | 46 (46 to 47) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 191 (189 to 194) | 197 (195 to 199) | 196 (193 to 198) | 192 (189 to 195) | 191 (186 to 195) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 97 (94 to 100) | 121 (118 to 125) | 131 (126 to 135) | 138 (130 to 145) | 125 (119 to 131) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 95 (94 to 97) | 97 (96 to 99) | 103 (101 to 105) | 105 (101 to 108) | 109 (105 to 113) |

| 2‐hour glucose, mg/dL | 112 (110 to 113) | 119 (117 to 121) | 128 (125 to 131) | 133 (130 to 137) | 133 (128 to 138) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.5 (5.5 to 5.6) | 5.6 (5.6 to 5.7) | 5.9 (5.8 to 5.9) | 5.9 (5.8 to 6.0) | 6.1 (6.0 to 6.3) |

| C‐reactive protein, g/L | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7) | 2.6 (2.4 to 2.7) | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.7) | 4.5 (4.3 to 4.8) | 5.1 (4.8 to 5.4) |

| No. (%) | |||||

| Nativity | |||||

| Within 50 states | 358 (19) | 424 (18) | 370 (20) | 217 (25) | 199 (36) |

| Outside of 50 states | 1500 (81) | 2943 (82) | 2173 (80) | 970 (75) | 529 (64) |

| Less than high school education | 564 (27) | 1269 (33) | 1077 (37) | 478 (36) | 283 (36) |

| Income | |||||

| ≤$40 000 | 1355 (46) | 2605 (52) | 1949 (53) | 920 (55) | 583 (53) |

| $40 001 to $75 000 | 221 (48) | 328 (44) | 269 (43) | 132 (43) | 65 (44) |

| >$75 000 | 71 (6) | 91 (4) | 69 (3) | 27 (2) | 22 (3) |

Body mass index categories were normal weight, ≥18.5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2; overweight, ≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2; class I obesity, ≥30 kg/m2 and <35 kg/m2; class II obesity, ≥35 kg/m2 and <40 kg/m2; and class III obesity, ≥40 kg/m2. BP indicates blood pressure; HDL‐C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol. Values presented in table are unweighted counts of participants. Other figures are weighted to reflect the sampling design.

Adjusted for age.

Not adjusted for age.

Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Across the Spectrum of BMI

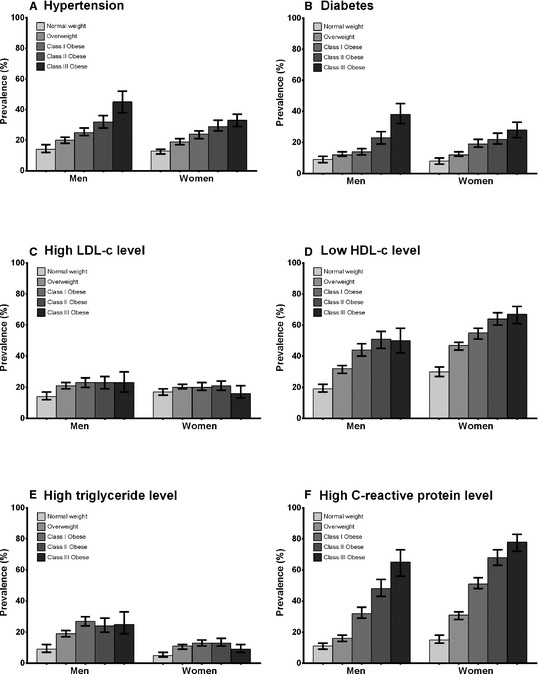

Hypertension

The prevalence of hypertension increased consistently across categories of BMI (Figure 2). After adjustment for age, education, health insurance status, field center, national background, nativity, smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity, the prevalence of hypertension was significantly higher among men than women (Table 3). Among those with class III obesity, men had a 58% higher adjusted prevalence of hypertension compared with women (adjusted PR, men versus women=1.58, 95% CI=1.30 to 1.92), while the differences between men and women in hypertension prevalence were relatively modest within other BMI groups (range of adjusted PRs, men versus women=1.17 to 1.30). The sex difference in hypertension prevalence within the class III obesity group was similar across national background groups (P for interaction=0.73).

Figure 2.

Age‐adjusted prevalence by sex and body mass index category of cardiovascular disease risk factors: hypertension (A), diabetes (B), high low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) level (C), low high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) level (D), hypertriglyceridemia (E), and high C‐reactive protein (CRP) level (F). Sex‐specific age‐adjusted prevalence of each CVD risk factor within groups defined by normal weight, BMI ≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2; overweight, BMI ≥25 and <30 kg/m2; class I obesity, BMI ≥30 and <35 kg/m2; and class II to III obesity, BMI ≥35 kg/m2. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose of ≥126 mg/dL, 2‐hour postload glucose levels of ≥200 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c level of ≥6.5%, or use of antidiabetic medication. High LDL‐C level was defined as (calculated) LDL‐C of ≥160 mg/dL or statin use. Low HDL‐C level was defined as <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women. Hypertriglyceridemia was defined as ≥200 mg/dL. High CRP was defined as 3 mg/L to 10 mg/L (individuals with CRP levels >10 mg/L were excluded from analyses). Test for linear trend across BMI categories was P<0.001 for all analyses except for LDL‐C in women, which suggested neither linear (P=0.381) nor quadratic (P=0.644) trends across BMI category. BMI indicates body mass index.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus rose in prevalence with increasing BMI category in both men and women (Figure 2).Among persons in the class III obese group, men were significantly more likely to have diabetes mellitus than women (adjusted PR=1.50, 95% CI=1.16 to 1.94) (Table 3). The sex difference in diabetes mellitus prevalence within the class III obesity group was similar across national background groups (P for interaction=0.60). Within the other BMI categories, adjusted prevalence of diabetes was not significantly different between men and women.

Unfavorable serum lipid levels

Among men, high LDL‐C level was less prevalent in the normal‐weight group as compared with the groups with elevated BMI. However, the prevalence of high LDL‐C level among men did not increase across overweight and obese groups (Figure 2). Among women, high LDL‐C levels had a less apparent association with BMI with neither a linear or quadratic statistically significant trend across categories. We observed no significant difference by sex in the adjusted prevalence of high LDL‐C levels, except in the group with class III obesity, among whom high LDL‐C levels was of 82% greater prevalence in men than in women (Table 3). The prevalence ratios of high LDL‐C by sex were similar across national background groups (P=0.76 for interaction by national background).

Compared with the normal‐weight group, those with progressively higher BMI tended to have greater prevalence of low HDL‐C levels (Figure 2). Women were significantly more likely than men to have low HDL‐C levels when sex‐specific cut points were used to define low HDL‐C level in women (Table 3). When the same cut point of <40 mg/dL was used in both men and women, men were significantly more likely than women to have low HDL‐C levels at all levels of BMI.

Among men and women, the prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia was lower among normal‐weight persons than among those with BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (Figure 2). However, the prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia did not have increasing frequency across overweight and obese groups. The adjusted prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia was ≈2‐fold higher among men than women at any given level of BMI (Table 3).

High CRP levels

The prevalence of high CRP level increased markedly with each progressively higher BMI category (Figure 2). At a given level of BMI, prevalence of high CRP level was significantly higher among women than among men (Table 3).

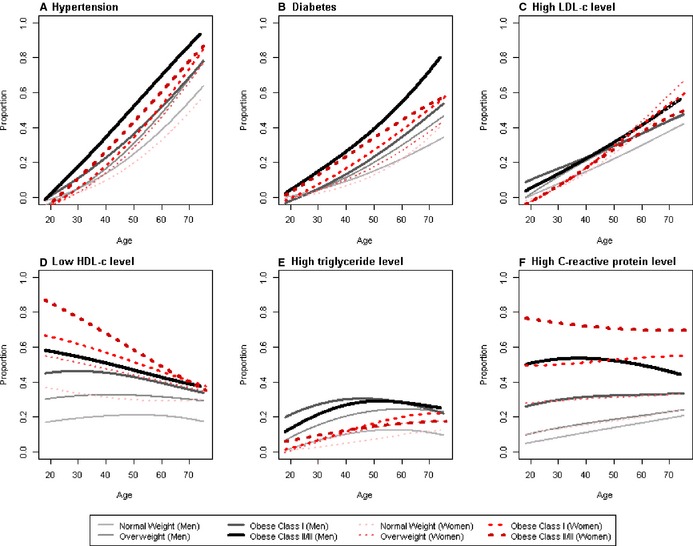

Age‐Specific Association Between Elevated BMI and Prevalent CVD Risk Factors

Analyses relating BMI with CVD risk factors at different ages (Figure 3) recapitulated the overall (age‐adjusted) associations between BMI and cardiovascular risk factors that appear in Figure 2. The increase in prevalences of hypertension and diabetes at higher levels of BMI was relatively consistent across the observed age range of 18 to 74 years. For other risk factors including low HDL‐C level and high CRP level, the differences in prevalence comparing overweight or obese individuals versus normal‐weight individuals were larger among younger age groups than among older age groups. Among those with class II or class III obesity, by the fourth decade of life, individual CVD risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, low HDL‐C level, and high CRP level were present among ≥40% of individuals.

Figure 3.

Prevalence by age and body mass index category of cardiovascular disease risk factors: hypertension (upper left); diabetes (upper middle); high low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) level (upper right); low high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) level (lower left); hypertriglyceridemia (lower middle); high C‐reactive protein (CRP) level (lower right). Smoothed curves display the age‐ and sex‐specific prevalence of each CVD risk factor within groups defined by normal weight, BMI ≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2; overweight, BMI ≥25 and <30 kg/m2; class I obesity, BMI ≥30 and <35 kg/m2; and class II to III obesity, BMI ≥35 kg/m2. Black curves represent males and red curves represent females. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose of ≥126 mg/dL, 2‐hour postload glucose levels of ≥200 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c level of ≥6.5%, or use of antidiabetic medication. High LDL‐C level was defined as (calculated) LDL‐C of ≥160 mg/dL or statin use. Low HDL‐C level was defined as <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women. Hypertriglyceridemia was defined as ≥200 mg/dL. High CRP was defined as 3 to 10 mg/L (individuals with CRP levels >10 mg/L were excluded from analyses). Smoothed curves were drawn by using local polynomials estimation using the svysmooth procedure with a bandwidth of 20 in the R statistical program. BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Discussion

BMI is an easily obtained measure to estimate adiposity that is widely used for identifying individuals at increased risk of adiposity‐related health outcomes and for setting body weight targets for patients attempting to lose weight.10, 11 In a study of >16 000 Hispanic/Latino adults aged 18 to 74 years old, our analyses characterizing the joint prevalences of high BMI levels and CVD risk factors suggest several conclusions. First, obesity was not only prevalent but also tended to be severe as defined by BMI level, particularly among young Latino adults. Second, women were more likely than men to have class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2). Yet, at these very high levels of BMI, relative to women, men were disproportionately affected by unfavorable metabolic CVD risk factors. Third, high BMI had a more pronounced association with prevalence of CVD risk factors among individuals at younger ages. For several CVD risk factors, including low HDL‐C level and high CRP level, we observed an especially steep gradient in these risk factors across the spectrum of BMI among younger as opposed to older adults. Moreover, among individuals with class II or class III obesity (BMI ≥35 kg/m2), prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, low HDL‐C levels, and high CRP levels approached or exceeded 40% in the fourth decade of life.

Our findings are yet another indicator of the vast morbidity, health care needs, and costs to society that are attributed not only to the presence but also the severity of obesity in the United States.12, 13, 14 One in 5 women and 1 in 10 men had BMI of ≥35 kg/m2, which defines class II or III obesity. The most severe form of obesity, class III, disproportionately affected younger Hispanic/Latino adults. This was especially the case among women, who had peak prevalence of BMI ≥40 kg/m2 in the 25‐ to 34‐year‐old age group (9% prevalence). Individuals with high BMI had a high prevalence both of traditional CVD risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, high LDL‐C level, and low HDL‐C level), as well as emerging risk factors such as hypertriglyceridemia and high CRP level, which may confer additional risk of CVD in the extremely obese beyond that captured by standard clinical disease risk scores.15

It has previously been shown that the magnitude of the association between elevated BMI and coronary heart disease mortality is nearly identical in men and in women. Relative risks of stroke associated with high BMI, however, are larger in men than in women.6 Data from population samples have not characterized in detail the sex‐specific CVD risk profiles of individuals at the highest levels of BMI. Our data raise questions about whether traditional BMI cut points to define classes of obesity stratify total CVD risks equally well in men and women, particularly at the extreme upper ranges. Diabetes mellitus and high LDL‐C level had comparable prevalence in men and women at BMI levels <40 kg/m2, but in the most severely obese group (class III obesity) men had 50% greater prevalence of diabetes and 75% greater prevalence of hypercholesterolemia than did women. Gender differences in blood pressure also became more dramatic with severe obesity, with men having 60% greater hypertension prevalence than women among the class III obesity group compared with <20% higher prevalence in the other BMI categories. Thus, we hypothesize that when patients reach the upper range of BMI, sex differences emerge that pose an especially important relative hazard of CVD, and therefore a greater need for intervention, among men than among women.

This large contemporary study examined CVD risk factors in >16 000 Latino adults, including 980 who met criteria for class III obesity. Few population‐based samples of any race or ethnic description have had sufficient numbers of individuals in the upper range of BMI to shed light on population CVD risk associated with class III obesity.5 While we did not address race/ethnicity comparisons directly in our study, prior data suggest that Hispanics and other minority groups may have increased cardiometabolic risk both because of, and independent of, their increased risk of suffering from obesity. In the San Antonio Heart Study, Mexican American individuals had higher prevalence of diabetes than non‐Hispanic whites at all levels of skinfold thickness.16 The San Antonio Heart Study data among US Hispanics mirror other findings suggesting increased obesity‐independent risk of diabetes among populations that have immigrated from low‐ and middle‐income countries to Western societies. For instance, in Ontario, Canada, black and Asian adults, most of whom were immigrants, had increased diabetes risk compared with whites at all levels across the BMI spectrum.17 Analyses of our HCHS/SOL Hispanic cohort reveal an overall diabetes prevalence of 16.9%, which is intermediate between contemporaneous published prevalences of 10.2% among non‐Hispanic whites and 18.7% among non‐Hispanic blacks in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.18 On the other hand, the SAHS found similar or lower prevalence of hypertension in Mexican Americans compared with non‐Hispanic whites.19 This is also consistent with comparisons among specific racial/ethnic groups within the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and our own HCHS/SOL population.20, 21

Limitations of our study included a lack of data on incident CVD events, leading us to rely instead on risk factors that predict future CVD risk. However, traditional CVD risk factors such as those studied here appear largely to explain the excess obesity‐related mortality and coronary heart disease risks.5 Our observational, cross‐sectional study data do not address what might be the benefits of weight reduction in the obese population.22 Comparisons of CVD risk factors across BMI categories were potentially confounded by unmeasured factors or differences in response rates by BMI. However, patterns of variation in risk factor prevalences by BMI, age, and sex were generally as expected, and a variety of confounding variables were considered. The present study was limited to a population‐based sample of Hispanics and Latinos recruited from 4 urban centers with an imperfect response rate. However, our observed BMI distribution was similar to that among Hispanic/Latino adults in the contemporaneous 2009–2010 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Moreover, the centers represented in HCHS/SOL reflect the majority of the US Hispanic/Latino population, which is largely concentrated within a small number of urban centers in the United States.23

Conclusions

We provide some of the first large‐scale data on BMI and CVD risk factors in the Hispanic/Latino adult population, among whom the obesity epidemic is markedly severe, especially in the youngest generations.24 While it is recognized that CVD risk factor profiles in general worsen with higher BMI, our data suggest that severe obesity may be associated with a considerable excess in CVD risk mediated by known CVD risk factors. Class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) was more common among women than among men in the Hispanic population sampled for the HCHS/SOL cohort. At the same time, we find that the tendency for men to have more unfavorable CVD risk factor status as compared with women is most pronounced at very high levels of BMI. Finally, individuals with severe obesity have a very high prevalence of known CVD risk factors even in the earliest decades of adulthood, auguring an extremely high lifetime risk of morbidity and mortality.

Sources of Funding

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01‐HC65233), University of Miami (N01‐HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01‐HC65235), Northwestern University (N01‐HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01‐HC65237). The following institutes/offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL baseline examination through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Office of Dietary Supplements.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The Helen Riaboff Whiteley Center at University of Washington Friday Harbor Laboratories is gratefully acknowledged for facilitating the completion of this work.

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Investigators

Program Office: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD: Larissa Avilés‐Santa, Paul Sorlie, Lorraine Silsbee. Field Centers: Bronx Field Center, Albert Einstein School of Medicine, Bronx, NY: Robert Kaplan, Sylvia Wassertheil‐Smoller. Chicago Field Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and University of Illinois at Chicago: Martha L. Daviglus, Aida L. Giachello, Kiang Liu. Miami Field Center, University of Miami, Miami, FL: Neil Schneiderman, David Lee, Leopoldo Raij. San Diego Field Center, San Diego State University and University of California, San Diego: Greg Talavera, John Elder, Matthew Allison, Michael Criqui. Coordinating Center: University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill: Jianwen Cai, Gerardo Heiss, Lisa LaVange, Marston Youngblood. Central Laboratory: University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Bharat Thyagarajan, John H. Eckfeldt. Central Reading Centers: Audiometry Center: University of Wisconsin: Karen J. Cruickshanks. ECG Reading Center: Wake Forest University: Elsayed Soliman. Neurocognitive Reading Center: University of Mississippi Medical Center: Hector Gonzales, Thomas Mosley. Nutrition Reading Center. University of Minnesota: John H. Himes. Pulmonary Reading Center: Columbia University: R. Graham Barr, Paul Enright. Sleep Center: Case Western Reserve University: Susan Redline.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000923 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000923)25008353

References

- 1. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among us adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okosun IS, Boltri JM, Eriksen MP, Hepburn VA. Trends in abdominal obesity in young people: United States 1988–2002. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:338–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sturm R. Increases in clinically severe obesity in the United States, 1986–2000. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2146–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Aviles‐Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Gellman M, Giachello AL, Gouskova N, Kaplan RC, LaVange L, Penedo F, Perreira K, Pirzada A, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil‐Smoller S, Sorlie PD, Stamler J. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among hispanic/latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308:1775–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McTigue K, Larson JC, Valoski A, Burke G, Kotchen J, Lewis CE, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Kuller L. Mortality and cardiac and vascular outcomes in extremely obese women. JAMA. 2006;296:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emerging Risk Factors C , Wormser D, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Wood AM, Pennells L, Thompson A, Sarwar N, Kizer JR, Lawlor DA, Nordestgaard BG, Ridker P, Salomaa V, Stevens J, Woodward M, Sattar N, Collins R, Thompson SG, Whitlock G, Danesh J. Separate and combined associations of body‐mass index and abdominal adiposity with cardiovascular disease: collaborative analysis of 58 prospective studies. Lancet. 2011;377:1085–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, Aviles‐Santa LM, Kaplan RC, Barnhart J, Liu K, Giachello A, Lee DJ, Ryan J, Criqui MH, Elder JP. Sample design and cohort selection in the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sorlie PD, Aviles‐Santa LM, Wassertheil‐Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, Schneiderman N, Raij L, Talavera G, Allison M, Lavange L, Chambless LE, Heiss G. Design and implementation of the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:629–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Myers GL, Rifai N, Tracy RP, Roberts WL, Alexander RW, Biasucci LM, Catravas JD, Cole TG, Cooper GR, Khan BV, Kimberly MM, Stein EA, Taubert KA, Warnick GR, Waymack PP; CDC, AHA . CDC/AHA workshop on markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: report from the laboratory science discussion group. Circulation. 2004;110:e545–e549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of all‐cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2482–2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Czernichow S, Kengne AP, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Batty GD. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist‐hip ratio: which is the better discriminator of cardiovascular disease mortality risk?: evidence from an individual‐participant meta‐analysis of 82 864 participants from nine cohort studies. Obes Rev. 2011;12:680–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hayman LL. The cardiovascular impact of the pediatric obesity epidemic: is the worst yet to come? J Pediatr. 2011;158:695–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crowley DI, Khoury PR, Urbina EM, Ippisch HM, Kimball TR. Cardiovascular impact of the pediatric obesity epidemic: higher left ventricular mass is related to higher body mass index. J Pediatr. 2011;158:e701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the us obesity epidemic. Obesity. 2008;16:2323–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stern MP, Gaskill SP, Hazuda HP, Gardner LI, Haffner SM. Does obesity explain excess prevalence of diabetes among mexican americans? Results of the san antonio heart study. Diabetologia. 1983;24:272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiu M, Austin PC, Manuel DG, Shah BR, Tu JV. Deriving ethnic‐specific bmi cutoff points for assessing diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1741–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schneiderman N, Llabre M, Cowie CC, Barnhart J, Carnethon M, Gallo LC, Giachello AL, Heiss G, Kaplan RC, LaVange LM, Teng Y, Villa‐Caballero L, Avilés‐Santa L. Prevalence of diabetes among hispanics/latinos from diverse backgrounds: the hispanic community health study/study of latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care, June, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haffner SM, Mitchell BD, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, Patterson JK. Decreased prevalence of hypertension in mexican‐americans. Hypertension. 1990;16:225–232. Discussion 233–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sorlie PD, Allison MA, Avilés‐Santa ML, Cai J, Daviglus ML, Howard AG, Kaplan R, LaVange LM, Raij L, Schneiderman N. Prevalence of hypertension, awareness, treatment, and control in the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:793–800. hpu003v001‐hpu003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu S, Heymsfield SB, Toyoshima H, Wang Z, Pietrobelli A, Heshka S. Race‐ethnicity‐specific waist circumference cutoffs for identifying cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodpaster BH, Delany JP, Otto AD, Kuller L, Vockley J, South‐Paul JE, Thomas SB, Brown J, McTigue K, Hames KC, Lang W, Jakicic JM. Effects of diet and physical activity interventions on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in severely obese adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1795–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brown A, Lopez M. Mapping the latino population, by state, county and city. Pew Res Center Rep. 2013. Available at http://pewrsr.ch/17mq1h4. Accessed June 24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]