Abstract

Objectives: The McMaster Optimal Aging Portal (the Portal) aims to increase access to evidence-based health information. We would now like to understand who uses the Portal, why, and for what, and elicit feedback and suggestions for future initiatives. Methods: An online survey of users collected data on demographics, eHealth literacy, Internet use, information-seeking behavior, site acceptability and perceived impact on health behaviors, participant satisfaction, and suggestions for improvements using mixed methods. Results: Participants (n = 163, age 69.8 ± 8.6 years) were predominantly female (76%), married (67%), retired (80%), and well-educated with very good/excellent health (55%). The Portal was easy to use (83%) and relevant (80%), with 68% intending to, and 48% having changed behavior after using the Portal. A number of suggestions for improvement were obtained. Discussion: A better understanding of users’ characteristics, needs, and preferences will allow us to improve content, target groups who are not engaging with the Portal, and plan future directions.

Keywords: aging, knowledge translation, public health, online health information

Background

Many people use a variety of online resources as trusted sources of information on health and wellness (Fox & Duggan, 2012; Richardson, Hamadani, & Gotay, 2013; Statistics Canada, 2013a, 2013b; Tennant et al., 2015). Increasingly, older adults are among this group of online health information seekers. According to recent data from Statistics Canada, 70% of Canadian adults use the Internet daily (Statistics Canada, 2013a), and 62% of those who have used the Internet in the past 12 months have used it to search for health or medical information (Statistics Canada, 2013b). While online health information websites have several potential advantages, including the removal of geographic boundaries and the provision of anonymity, much of the online health information available is not based on scientific evidence and therefore unlikely to produce intended health benefits (Moorhead et al., 2013; Pandey, Hasan, Dubey, & Sarangi, 2013). In many cases, individuals may be acting on recommendations that have the potential for negative side effects (Redeker, Wardle, Wilder, Hiom, & Miles, 2009; van Veen, Beijer, Adriaans, Vogel-Boezeman, & Kampman, 2015).

In recent years, several online health information portals have been reported in the literature, most commonly for specific patient populations. A recent systematic review identified published literature on 35 online web portals that had undergone some form of scientific evaluation (Coughlin et al., 2017). These sites varied from portals connected to electronic medical records, those for specific diseases or patient groups, and those targeting prevention or general health promotion. Although the findings of effectiveness across studies were inconsistent, several studies showed a positive impact of patient portals on various aspects of chronic disease management (Coughlin et al., 2017).

The McMaster Optimal Aging Portal (the Portal) was launched in English in 2014 and in French in 2017, as a knowledge translation (KT) initiative to increase public access to trustworthy health information (“McMaster Optimal Aging Portal”). The Portal is unique among health information websites with its rigorous quality appraisal of evidence and its specific target of older adults and caregivers. The overarching aim of the Portal is to serve as a source of evidence-based information that can be used by aging adults and caregivers to achieve “optimal aging” (to stay healthy, active, and engaged as they grow older). This may be accomplished by increasing knowledge about factors related to healthy aging, assisting users with preparing for, or following up from, a discussion with a health care provider, and disproving myths or incorrect information.

A full description of the Portal and its development, along with website features, have been published previously (Barbara, Dobbins, Haynes, Iorio, Lavis, & Levinson, 2016; Barbara, Dobbins, Haynes, Iorio, Lavis, Raina, & Levinson, 2016; Barbara et al., 2017). Briefly, the Portal contains content that is relevant to both the general public and health professionals from three best-in-class resources (MacPLUS™, Health Evidence™, and Health Systems Evidence). General public content falls within four categories: Evidence Summaries, Web Resource Ratings, Blog Posts, and Twitter messages. A usability evaluation was conducted in 2015 with 37 older adults over 33 usability sessions and 21 interviews (Barbara, Dobbins, Haynes, Iorio, Lavis, Raina, & Levinson, 2016), followed by a qualitative study with 22 older adults and informal caregivers to gain a greater understanding of the user experience (Barbara, Dobbins, Haynes, Iorio, Lavis, & Levinson, 2016). Information from these studies, along with ongoing feedback from a Citizen’s Advisory Council and Expert Advisory Council, helps to ensure the Portal remains relevant for the target population.

Although we see through website and email analytics that users are engaged with the Portal website and its weekly email subscription list (“Email alerts”), there is a need to understand more about who is using the Portal, for what purpose, and whether or not it is meeting users’ needs. This information would allow us to continue to develop the most appropriate evidence-based content about healthy aging for the public and could be used to improve Portal content moving forward, as well as identifying target groups of participants who are not currently engaging with the Portal.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to (a) describe the characteristics of current users of the Portal, (b) gain a deeper understanding of what purpose users have for visiting the Portal, and (c) gather feedback on strengths and weaknesses, and potential effects the Portal may have on users’ health and well-being.

Method

Participant recruitment took place over 6 weeks from November to December 2016. During this time, study information was included in weekly email alerts for Portal subscribers, in a link on the Portal homepage, and distributed through both the Portal and partner’s social media (Twitter and Facebook). Eligible participants included anyone who had used the Portal previously, and who could read and respond in English.

Interested participants were directed to a link for the study-specific webpage where they were given more information about the purpose of the study, provided informed consent, and completed the survey. The survey was administered using LimeSurvey (LimeSurvey GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). This study received ethical approval from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

Survey questions were classified within four general categories, and data were collected using a mix of previously developed questionnaires or checklists, and open-ended questions. Demographic data, including eHealth literacy (using the eHealth Literacy Scale [Norman & Skinner, 2006]), were collected to describe the characteristics of the people who use the Portal. To understand what motivates people to use the Portal, questionnaires about general Internet use and health information seeking behavior (Bright, Hambly, & Tamakloe, 2016) were completed alongside open-ended questions to identify how participants found out about, and why they were interested in the Portal. The Information Assessment Method for all (IAM4all; Pluye et al., 2014) and a questionnaire for website acceptability (Fennell et al., 2016) were completed alongside open-ended questions to capture satisfaction with the Portal and suggestions for improvement. Finally, participants’ perceptions of the Portal’s influence on intentions and behaviors (Cugelman, Thelwall, & Dawes, 2009) were assessed to understand the potential impact the Portal may have on health or health behaviors.

Quantitative data analysis was completed using R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria). Demographic data and eHealth literacy were summarized using descriptive statistics to describe the study sample. Quantitative user feedback from the IAM4all, website acceptability, and perceived impact on intentions and behaviors were summarized using descriptive statistics (measures of central tendency and variation), and interpreted alongside qualitative data.

Qualitative data from open-ended questions were entered into NVivo 11 software (QSR International, Burlington, MA) for data storage, indexing, searching, and coding. Two members (S.N.S. and R.F.) of the study team met to develop a coding scheme based on the open-ended questions and preliminary data analysis. Once the coding scheme was developed, one team member coded all data, and coding was reviewed by a second team member to check for accuracy and consistency. All codes were mapped and grouped into themes based on an iterative review by two members of the study team.

Results

Over 6 weeks of participant recruitment, 349 individuals responded to our survey invitation. Of these, 189 provided informed consent and completed the survey. Twenty-six participants reported not having used the Portal before and were removed from this analysis for a total of 163 complete and eligible survey responses.

Participant demographics are displayed in Table 1. The majority of participants were women, married, well-educated, and of high socioeconomic status. More than 80% were retired. Self-rated health (measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale) was generally high, despite 59% of participants indicating they had at least one chronic health condition. Almost all participants had regular access to a health care provider. eHealth literacy was high (mean 29.7 out of a possible 40), with higher reported scores for the domain of using eHealth than understanding eHealth (Richtering et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Included Survey Respondents (n = 163).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 69.8 (8.6) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 124 (76.1) |

| Male | 37 (22.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (1.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or common law | 109 (66.9) |

| Separated or divorced | 25 (15.3) |

| Widowed | 17 (10.4) |

| Single | 9 (5.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (1.8) |

| Education | |

| Up to high school graduation | 15 (9.2) |

| Community college or bachelor’s degree | 85 (52.1) |

| Postgraduate or professional degree (MSc, PhD, MD, etc.) | 61 (37.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (1.2) |

| Personal income, after tax | |

| Less than CAN$20,000 | 9 (5.5) |

| Between CAN$20,000 and CAN$39,999 | 30 (18.4) |

| Between CAN$40,000 and CAN$59,999 | 27 (16.6) |

| Between CAN$60,000 and CAN$79,999 | 24 (14.7) |

| Greater than CAN$80,000 | 31 (19.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 42 (25.8) |

| Employment status | |

| Retired | 131 (80.4) |

| Working full-time (>30 hr per week) | 14 (8.6) |

| Working part-time (<30 hr per week) | 10 (6.1) |

| Self-employed | 7 (4.3) |

| Long-term disability | 1 (0.6) |

| Language spoken at home | |

| English | 157 (98.7) |

| French | 1 (0.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.6) |

| Self-rated health | |

| Excellent/very good | 90 (55.2) |

| Good | 57 (35.0) |

| Fair/poor | 15 (9.2) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.6) |

| Chronic health conditions | |

| Yes | 96 (58.9) |

| No | 62 (38.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 (3.1) |

| Providing unpaid care for an older adult | |

| Yes | 28 (17.2) |

| No | 134 (82.2) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.6) |

| Regular access to a health care provider | 158 (96.9) |

| eHealth literacy, M (SD) | 29.65 (4.73) |

| Find the Internet useful/very useful in helping to make decisions about health | 140 (85.9) |

| It is important/very important to be able to access health resources on the Internet | 151 (92.6) |

| Reported agree/strongly agree with the following: | |

| I know what health resources are available on the Internet | 113 (69.3) |

| I know where to find helpful health resources on the Internet | 124 (76.1) |

| I know how to find helpful health resources on the Internet | 129 (79.1) |

| I know how to use the Internet to answer my questions about health | 129 (79.1) |

| I know how to use the health information I find on the Internet to help me | 116 (71.2) |

| I have the skills I need to evaluate the health resources I find on the Internet | 96 (58.9) |

| I can tell high quality health resources from low quality health resources on the Internet | 102 (65.6) |

| I feel confident in using information from the Internet to make health decisions | 83 (50.9) |

Almost all (95%) participants were daily Internet users, and 59% reported using the Internet to look for health information at least daily or weekly (Table 2). Participants most commonly sought information for themselves (96%) or a partner or spouse (51%). Facebook was the most common social media platform used (65% at least monthly use). YouTube was not commonly used (42% reporting seldom or never use), and few participants used Twitter or LinkedIn (84%, 82%, seldom or never).

Table 2.

Self-Reported Patterns of Internet Use (n = 163).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| In general, how often do you use the Internet? | |

| Seldom or never | 1 (0.6) |

| Monthly/weekly | 7 (4.3) |

| Daily | 155 (95.1) |

| How often do you use the Internet to look for advice on information about health or healthy aging? | |

| Seldom or never | 12 (7.4) |

| Monthly | 55 (33.7) |

| Weekly | 74 (45.4) |

| Daily | 22 (13.5) |

| Do you search for online information about healthy aging for yourself or someone else? (Check all that apply) | |

| Self | 157 (96.3) |

| Partner, spouse | 83 (50.9) |

| Friend | 27 (16.6) |

| Parent | 22 (13.5) |

| Another relative | 22 (13.5) |

| Child | 19 (11.7) |

| Patient | 2 (1.2) |

| What types of social media do you use? | |

| Seldom or never | 137 (84.0) |

| Monthly/weekly | 12 (7.4) |

| Daily | 10 (6.1) |

| Seldom or never | 58 (35.6) |

| Monthly/weekly | 23 (14.1) |

| Daily | 80 (49.1) |

| Seldom or never | 133 (81.6) |

| Monthly/weekly | 25 (15.3) |

| Daily | 2 (1.2) |

| YouTube | |

| Seldom or never | 68 (41.7) |

| Monthly/Weekly | 78 (47.9) |

| Daily | 15 (9.2) |

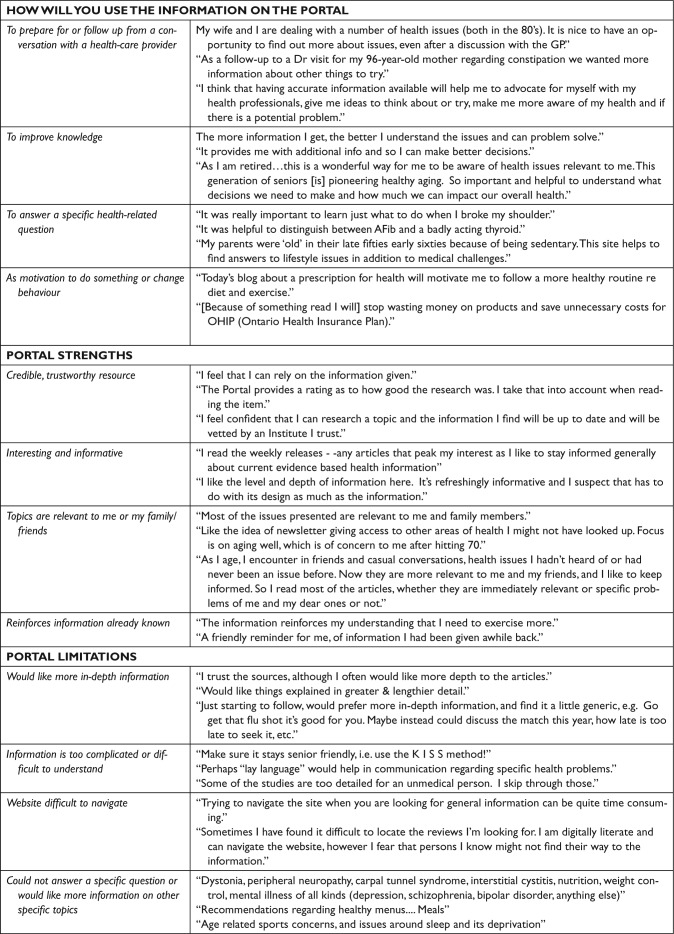

Almost half of respondents (47%) self-reported being regular Portal users (Table 3). According to the closed-ended questionnaires, the most common reasons for visiting the Portal were to satisfy curiosity (77%), or to answer a question about one’s health (53%). This was echoed in the qualitative open-ended responses, in which dominant themes emerged around gathering general information about health, or looking for information about specific health-related questions. Over two thirds reported finding the information they were looking for. Of these, 66% reported learning something new, 55% were reminded of something they already knew, and 53% were motivated to learn more. Over 87% of respondents reported that they would use the information they learned for themselves or for someone else, and almost all of those (97%) expected to benefit from the information. The most commonly reported expected benefits were being better able to handle a health problem (88%), being better able to communicate with a health professional (85%) and being able to make more informed decisions about ones’ health (84%). These findings were again confirmed using open-ended questions when main themes emerged around preparing for or following-up from a visit with a health care provider, improving general knowledge, and answering a specific health condition question. An additional finding from the open-ended questionnaire was a reported benefit of the Portal as a motivation to change behavior (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Responses to Closed-Ended Questionnaire to Obtain Feedback About the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal (n = 163).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Have you used the Portal before today? | |

| Yes, once or twice | 32 (19.6) |

| Yes, a few times | 55 (33.7) |

| Yes, I am a regular user | 76 (46.6) |

| Why did you visit the Portal? (Check all that apply) | |

| To satisfy my curiosity about a health matter | 125 (76.7) |

| To answer questions about my health | 86 (52.8) |

| To follow up on information given by a health professional | 70 (42.9) |

| To answer a question about the health of someone else | 62 (38.0) |

| To prepare myself before talking to a health professional | 53 (32.5) |

| To find choices different from those given by a health professional | 41 (25.2) |

| To help me decide if I should see a health professional | 37 (22.7) |

| Did you find the information you were looking for? | |

| Yes | 110 (67.5) |

| Yes, but I did not understand it | 6 (3.7) |

| No, but I found something else | 17 (10.4) |

| No, I did not find it | 12 (7.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 18 (11.0) |

| What did you think about this information? (Check all that apply) | |

| Now I know something new | 84 (66.1) |

| I am reminded of something I already know | 70 (55.1) |

| Now I want to learn more about this health matter | 67 (52.8) |

| This information says I did or I am doing the right thing | 60 (47.2) |

| Now I am reassured | 59 (46.5) |

| I am not satisfied with this information | 4 (3.1) |

| I think there is a problem with this information | 3 (2.4) |

| I think that this information could be harmful | 3 (2.4) |

| Will you use this information for yourself? | |

| Yes | 101 (79.5) |

| Not for myself, but I will use this information for someone else | 10 (7.9) |

| Do you expect to benefit from this information? | |

| Yes | 108 (97.3) |

| If yes, how do you expect to benefit? (Check all that apply) | |

| This information will help me to better handle a problem with my health | 88 (88.0) |

| This information will allow me to better communicate with a health professional | 85 (85.0) |

| Because of this information, I will be more involved in decisions about my health | 84 (84.0) |

| This information will help me to prevent a health problem or the worsening of a health problem | 82 (82.0) |

| This information will help to improve my health | 82 (82.0) |

| This information makes me more satisfied with the health care I receive | 71 (71.0) |

| This information helps me feel less worried about a health problem | 68 (68.0) |

| Did something negative come out of using this information? | |

| No | 110 (99.1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.9) |

| Portal feedback (agree/strongly agree) | |

| The Portal is helpful | 146 (89.6) |

| The Portal is easy to use | 136 (83.4) |

| The Portal is relevant to my needs | 120 (79.8) |

| The Portal provides necessary information | 127 (77.9) |

| Future use (Check all that apply) | |

| I will return to the Portal | 156 (95.7) |

| I will recommend the Portal to someone else | 133 (81.6) |

| Knowledge, intentions, and behaviors (Check all that apply) | |

| Because of the Portal, I feel more knowledgeable about topics related to my health | 130 (79.8) |

| Because of the Portal, I plan on engaging in behaviors that will improve my health | 111 (68.1) |

| Because of the Portal, I have made a change in my actions or behaviors | 78 (47.9) |

Figure 1.

Summary of qualitative responses to open-ended survey questions.

The majority of participants reported that the Portal was easy to use and helpful, and over 95% reported that they would return to the website in the future. With respect to the potential benefits to participants’ knowledge, intentions, and behaviors, 80% reported that they feel more knowledgeable because of the Portal, 68% reported they intended to engage in a health behavior change because of the information accessed via the Portal, and 48% reported that they had already changed a health behavior. In response to open-ended questions about the strengths of the Portal, major themes reported were the benefits of the Portal as a credible and trustworthy resource; being interesting and informative; being relevant to oneself, friends, or family; and reinforcing information.

When asked for limitations of the Portal, two opposing themes emerged from open-ended responses. Some participants voiced a desire for more detailed or in-depth information about a topic, while others reported that the information was too complicated or difficult to understand and that they would prefer more simple information. Other themes emerged around website navigation and usability, such as information being difficult to find on the site, or requests for items that already exist on the Portal, such as a search function or list of topics. There was also a desire for more information about specific topics of interest, which ranged widely from specific diseases to treatment choices or lifestyle behaviors, like specific exercises or meal plans.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to better understand the characteristics of users of the Portal and their experiences with the Portal, how and why they used the Portal, its perceived strengths and weaknesses, and its perceived effects on their knowledge, health, and well-being. This knowledge will not only help to inform the future work of the Portal, but will be useful to others who maintain health information or patient portals or websites, whether for healthy aging or other specific populations.

In general, our user population was found to be quite homogeneous, and comprised of primarily well-educated, married, female retirees with good to excellent self-rated health. This is consistent with other published literature, which has found that racial and ethnic minorities, younger individuals, and those with lower levels of education or health literacy were less likely to use online health portals (Coughlin et al., 2017).

Overall feedback on the Portal was positive from both quantitative questionnaires and open-ended survey questions. What particularly emerged through both data collection methods was the importance of the trustworthiness of the resource, being affiliated with a university, based on scientific evidence, and quality appraised. This theme emerged in response to questions about both the users’ reason for visiting the Portal and strengths of the Portal. This in turn likely leads to the reports of greater perceived benefits of using the website, and appreciation of the knowledge acquired. These are encouraging findings, as the original overarching purpose of the Portal is to serve as a high-quality, evidence-based KT platform that aging adults, their caregivers, clinicians, public health professionals, and policy makers can trust to be a source of accurate information about healthy aging.

Research studies are often nuanced, with limitations and caveats, and it may not always be possible to provide a simple actionable message that will meet the needs of users with diverse experiences and background knowledge. This is an ongoing challenge for those who work to disseminate scientific research to the general public. It is difficult to strike an appropriate balance between providing straightforward and clear messaging to the nonscientific community while also providing sufficient detail to retain the accuracy of the actual research findings. An interesting finding from this survey was the apparent split between users who desired more in-depth and detailed information, finding the current presentation of information too simplistic, with those who reported that the information presented was complicated and difficult to understand, and suggested simplification of the messaging. This finding highlights the variation across users’ needs and expectations for health information, and suggests that perhaps different communication strategies within the same site may be useful for meeting these differing needs. Within the Portal, two of the content categories specifically aim to translate research findings into lay language: (a) Blog Posts that summarize the current body of research evidence on a particular topic and (b) plain-language Evidence Summaries of high-quality systematic reviews, providing details of the study methodology, populations, interventions, limitations, and findings. While usage data indicate that Blog Posts are the most popular amongst users, findings from this survey suggest that these two types of content should continue to be used to meet differing needs among our user group.

In the development phase of the Portal, our team conducted multiple rounds of user and usability testing to ensure the design and functionality of the website was acceptable to the target audience (Barbara, Dobbins, Haynes, Iorio, Lavis, & Levinson, 2016; Barbara, Dobbins, Haynes, Iorio, Lavis, Raina, & Levinson, 2016). Despite this, some users still reported challenges in navigating the site and offered suggestions for added features that would help with functionality. In many instances, users requested functions (such as a search feature, or list of topic options) that already exist on the site. This represents another difficulty for those who are developing and maintaining websites for older adults, some of whom may have less experience navigating these types of information portals. This highlights the need for ongoing engagement with consumers to learn what is not being understood on established sites even after the development phase is complete.

Limitations

With thousands of unique users who visit the Portal on a monthly basis, these 163 survey respondents represent a very small proportion of overall users. Due to our recruitment through other Portal partners, we are unable to determine how many people were invited to participate, and thus what our overall response rate was for this survey. It is likely that these respondents may represent our most engaged users, and perhaps those with the most positive views of the Portal. However, the purpose of this survey was to understand the characteristics and experiences of those who use the Portal, and we believe that although the views are not likely representative of all of those who visit the site, they may be a good representation of our most active users. Future work could explore how to engage and satisfy other groups who may be less involved with the Portal or who may have a greater potential to benefit, such as those of lower socioeconomic status, those with lower self-rated health, or those without regular access to a primary health care provider.

An ongoing challenge in assessing the impact and usefulness of a site such as the Portal is to determine the best way to evaluate these tools in terms of individual- and population-level impact. Monitoring website and email analytics allows us to quantify the number of individuals who use the site, and which types of content and topics are most popular, but we recognize that clicking a link may be far removed from having a positive impact on knowledge, behaviors, and ultimately health. Although there are limitations in this self-reported data, we can be encouraged that respondents to this survey reported feeling more informed, more confident, and to have greater knowledge because of using the Portal. Participants also reported an intention to change health behaviors or having already made a change in a health behavior because of using the Portal. These findings should be confirmed in future randomized controlled trials, of which two are currently underway using the Portal (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02947230 and NCT03186703).

With the growing availability of information through various online sources, there is a need for a trustworthy resource of high-quality health information that the general public, caregivers, and health professionals can turn to. Based on the responses to this survey, the Portal appears to be filling this need among current users. Future research should continue to explore user characteristics, needs and preferences, and the most effective ways to provide online, evidence-based information to a general audience.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Suzanne Labarge via the Labarge Optimal Aging Initiative. This study was made possible by funding through the Labarge Opportunities Fund. Sarah E. Neil-Sztramko is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Anthony J. Levinson is supported through the John R. Evans Chair in Health Sciences Educational Research and Instructional Development.

References

- Barbara A. M., Dobbins M., Haynes R. B., Iorio A., Lavis J. N., Levinson A. J. (2016). User experiences of the McMaster Optimal Aging Portal’s evidence summaries and blog posts: Usability study. JMIR Human Factors, 3(2), e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara A. M., Dobbins M., Haynes R. B., Iorio A., Lavis J. N., Raina P., Levinson A. (2016). The McMaster Optimal Aging Portal: Usability evaluation of a unique evidence-based health information website. JMIR Human Factors, 3(1), e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara A. M., Dobbins M., Haynes R. B., Iorio A., Lavis J. N., Raina P., Levinson A. J. (2017). McMaster Optimal Aging Portal: An evidence-based database for geriatrics-focused health professionals. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), Article 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright P., Hambly K., Tamakloe S. (2016). What is the profile of individuals joining the KNEEguru Online Health Community? A cross-sectional mixed-methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(4), e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin S. S., Prochaska J. J., Williams L. B., Besenyi G. M., Heboyan V., Goggans D. S., . . . De Leo G. (2017). Patient web portals, disease management, and primary prevention. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 10, 33-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cugelman B., Thelwall M., Dawes P. (2009). The dimensions of web site credibility and their relation to active trust and behavioural impact. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 24(26), 455-472. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell K. M., Turnbull D. A., Bidargaddi N., McWha J. L., Davies M., Olver I. (2016). The consumer-driven development and acceptability testing of a website designed to connect rural cancer patients and their families, carers and health professionals with appropriate information and psychosocial support. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26, e12533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S., Duggan M. (2012). Mobile health 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre’s Internet & American Life Project. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster Optimal Aging Portal. Available from http://www.mcmasteroptimalaging.org

- Moorhead S. A., Hazlett D. E., Harrison L., Carroll J. K., Irwin A., Hoving C. (2013). A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(4), e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman C. D., Skinner H. A. (2006). eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8(4), e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A., Hasan S., Dubey D., Sarangi S. (2013). Smartphone apps as a source of cancer information: Changing trends in health information-seeking behavior. Journal of Cancer Education, 28, 138-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluye P., Granikov V., Bartlett G., Grad R. M., Tang D. L., Johnson-Lafleur J., . . . Doray G. (2014). Development and content validation of the information assessment method for patients and consumers. JMIR Research Protocols, 3(1), e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redeker C., Wardle J., Wilder D., Hiom S., Miles A. (2009). The launch of cancer research UK’s “reduce the risk” campaign: Baseline measurements of public awareness of cancer risk factors in 2004. European Journal of Cancer, 45, 827-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C. G., Hamadani L. G., Gotay C. (2013). Quantifying Canadians’ use of the Internet as a source of information on behavioural risk factor modifications related to cancer prevention. Chronic Diseases and Injuries in Canada, 33(3), 123-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtering S. S., Morris R., Soh S. E., Barker A., Bampi F., Neubeck L., . . . Redfern J. (2017). Examination of an eHealth Literacy Scale and a Health Literacy Scale in a population with moderate to high cardiovascular risk: Rasch analyses. PLoS One, 12(4), e0175372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2013. a). Canadian Internet use survey, Internet use, by age group, frequency of use and sex (CANSIM Table 358-0155). Ottawa, Ontario: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2013. b). Canadian Internet use survey, Internet use, by age group, Internet activity, sex, level of education and household income (CANSIM Table 358-0153). Ottawa, Ontario: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant B., Stellefson M., Dodd V., Chaney B., Chaney D., Paige S., Alber J. (2015). eHealth literacy and Web 2.0 health information seeking behaviors among baby boomers and older adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(3), e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veen M. R., Beijer S., Adriaans A. M., Vogel-Boezeman J., Kampman E. (2015). Development of a website providing evidence-based information about nutrition and cancer: Fighting fiction and supporting facts online. JMIR Research Protocols, 4(3), e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]