Abstract

The evidence linking aging and cancer is overwhelming. Findings emerging from the field of regenerative medicine reinforce the notion that aging and cancer are profoundly interrelated in their pathogenetic pathways. We discuss evidence to indicate that age-associated alterations in the tissue microenvironment contribute to the emergence of a neoplastic-prone tissue landscape, which is able to support the selective growth of preneoplastic cell populations. Interestingly, tissue contexts that are able to select for the growth of preneoplastic cells, including the aged liver microenvironment, are also supportive for the clonal expansion of normal, homotypic, transplanted cells. This suggests that the growth of normal and preneoplastic cells is possibly driven by similar mechanisms, implying that strategies based on principles of regenerative medicine might be applicable to modulate neoplastic disease.

Keywords: aging, cancer, regenerative medicine, hepatocyte transplantation, tissue fitness

Introduction

The evidence linking aging and cancer is overwhelming to the point that the question pertaining to the possible basis of such a strong relationship is unescapable for researchers involved in both fields. However, finding answers to this question has proven particularly difficult, largely due to the biological intricacies of both the aging and the neoplastic processes. In this context, it is of paramount importance to consider whether aging and cancer represent 2 chronologically parallel, but biologically unrelated processes, or whether they result from shared etiologies and/or pathogenetic mechanisms. If in fact the latter is true, a better understanding of basic alterations associated with aging may help elucidate major biological driving forces leading to the emergence of the neoplastic phenotype; most importantly, strategies aimed at delaying the aging process may also have a beneficial impact on the morbidity and/or mortality from neoplastic disease.

Aging and Tissue Function

A precise definition of aging remains elusive: It is commonly described as a progressive accumulation of cell and tissue damage, leading to decreased functional proficiency and increased susceptibility to disease.1 At the cellular level, alterations in all macromolecular components have been reported. The yellow-brown granular pigment lipofuscin was one of the first to be described: It consists of aggregates of oxidized lipids covalently linked to proteins and contributes to the typical “brown atrophy” of tissues found in aged individuals.2 In fact, spontaneous nonenzymatic biological side reactions, including glycation, have been proposed to represent a main mechanism of aging in higher animals, as part of the more general free radical theory of aging.3,4

In more recent years, a decline in the efficiency of proteostasis, that is, the integrated systems that oversee cellular, tissue, and organismal protein quality control, has gained center stage as a candidate driver of biological aging.5 Intracellular proteostasis is normally ensured by the activity of chaperones and 2 complimentary proteolytic pathways: the ubiquitin proteasome and the autophagy systems. Changes in each step of these pathways have been reported with age. Chaperones are essential for initial protein folding and transferring proteins across cellular organelles,6 a process requiring ATP whose availability may be limited in old age.7 Furthermore, repair of damaged proteins may be compromised in aging, due to decreased activity of dedicated enzymes.8 Similarly, both proteasomal function and autophagy decline with age,9 increasing the risk for the piling up of aggregates both inside and outside the cell.5,9

Aging is also associated with epigenetic changes, such as altered DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications, which lead to the progressive and profound alteration of transcriptional profiles of coding and noncoding RNA.10,11 Experimental evidence suggests that such large-scale alterations are linked to the inflammatory status and are in response to environmental stimuli and/or nutrient availability.12 The decline of the proliferative capacity in aging cells is tightly associated with a general loss of histones and with an imbalance between activating and repressive histone modifications.13,14 In addition, DNA methylation patterns are modified with age, and the methylation status of some specific regions (termed clock CpGs) can accurately predict age.15,16 A recent study reported that, in senescent cells, >30% of chromatin is dramatically reorganized, including the formation of large-scale domains of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 over lamina-associated domains as well as large losses of H3K27me3 outside these domains,10 which is linked to the transcriptional downregulation of lamin B1 in senescence.10,17,18 In general, age is associated with global DNA hypomethylation and local hypermethylation in some specific regions.12 This, together with histone modification changes associated with inflammation aging and oxidative stress, can affect the activation or the repression of specific transcriptional programs, including those involved in the expression of cytokines, oncogenes, and tumor suppressor genes, thus predisposing the tissue to chronic inflammatory diseases associated with age and cancer.11,19

On the other hand, the hypothesis that aging might be sustained by chronic and progressive damage accrued on the molecular repository of the genetic information, that is, DNA, has historically received special attention.20–23 Both endogenous and exogenous sources of DNA damage can contribute to genotoxicity, including the recently reported uptake of circulating nucleic acids, which can act as mobile genetic elements, possibly fueling mutagenesis and promoting cellular aging.24 Although most spontaneous or induced DNA alterations are short lived, a small fraction, including double-strand breaks and interstrand cross-links, is more difficult to repair and may persist25,26 leading to changes in chromatin structure and deregulated transcription.23,27

Irrespective of the specific altered targets, be they membrane lipids, proteins, or DNA, the underlying implication is that the gradual increase in macromolecular derangement translates into a decreased fitness at the cellular and tissue levels, which is the main hallmark of aging.28–30 As an example, regenerative capacity in vertebrates, which is an integrated complex functional response, declines with age in several organs31 including liver.32 Based on these premises, any hypothesis postulating a pathogenetic link between aging and cancer should consider whether and how a decreased cell/tissue fitness, such as found in old age, could favor the emergence of a neoplastic phenotype.

Aging versus Neoplastic Disease

As mentioned above, 2 opposing paradigms have been proposed to account for the association between aging and cancer. A widely entertained view is that aging and cancer represent parallel but unrelated biological processes. This possibility is in fact implied in a mainstream paradigm, which proposes to explain the increased risk of neoplastic disease associated with age as a direct consequence of DNA damage occurring in rare cells.33,34 According to this interpretation, the main target and rate-limiting step in the origin of age-associated neoplasia is the time-dependent appearance of rare cells harboring critical genetic (oncogenic) alterations. In this view, emphasis is placed on chronological aging (more time is available for mutagenesis in rare cells), while little or no relevance is attributed to widespread molecular changes, including genetic and epigenetic changes, occurring in the bulk of the aging tissue, which underlies functional decline (biological aging).

On the other hand, it is now widely recognized that the pathogenesis of neoplastic disease is heavily dependent on cues emanating from the tissue and/or systemic environment where the process occurs.35,36 Within this conceptual framework, the role of age-related changes in the origin of cancer has often been referred to the progressive waning of effector mechanisms of immune surveillance,37 which are thought to be relevant for the clearance of putative preneoplastic cells.38,39 However, the question regarding the precise role of immune surveillance in controlling the growth of cancerous and/or precancerous lesions is still open, given the known ability of cancer to induce tolerance.40,41 An alternative, albeit not mutually exclusive, hypothesis builds on the assumption that a landscape of decreased tissue fitness may provide the opportunity for the selection of mutant cells with oncogenic potential, increasing the risk of cancer through a process of “adaptive oncogenesis”.42,43

The Tumor-Promoting Effect of a Chemically Induced Low-Fitness Tissue Environment

Taking advantage of an experimental model developed in our laboratories, several years ago we investigated the role of a severely growth-constrained tissue environment on the expansion of preneoplastic and neoplastic cell populations. Experiments were conducted in rats treated with pyrrolizine alkaloids (PAs), a class of naturally occurring compounds that are known for their ability to impose a long-lasting block in the cell cycle of hepatocytes.44 Initial studies indicated that a brief exposure to retrorsine (RS), a commercially available PA, given in 2 doses, was able to suppress the capacity of the liver to restore liver mass after 2/3 partial hepatectomy, and the effect persisted for at least several months.45 Such an experimental setting was then used as a model system to test the growth behavior of transplanted preneoplastic hepatocytes. The latter were isolated from chemically induced liver nodules and injected, via portal vein, into the liver of rats pretreated with RS as described above. The fate of donor-derived cells in the recipient liver was monitored over time using the dipeptidyl peptidase type IV-deficient (DPPIV−) syngenic rat system for hepatocyte transplantation, in which donor animals express the DPPIV enzyme (DPPIV+), while host rats are DPPIV−. Results were clear-cut: Nodular hepatocytes grew very rapidly, giving rise to large liver nodules and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) within 4 to 6 mo upon transplantation in animals treated with RS.46 By contrast, the same cells were unable to expand to any extent when transferred into the liver of normal young hosts not exposed to RS.46 Thus, the growth-compromised tissue environment induced by the alkaloid was able to sustain the expansion of preneoplastic hepatocytes; moreover, and very importantly, the liver microenvironment of healthy, untreated young recipients was not permissive for the growth of the same preneoplastic cell population.

Conceptually related results were reported by Marusyk et al. in mouse hematopoietic tissue, where it was shown that exposure to irradiation leads to a decline in fitness of hematopoietic stem cells and promotes selection of precursors harboring advantageous oncogenic mutations, thereby contributing to leukemogenesis.47

Similar to radiation, PAs, including RS, are genotoxic compounds.48 Moreover, exposure to RS generates persistent DNA adducts in vivo,49 a possible contributing factor to the long-lasting block on cell cycle exerted by this alkaloid.45 In line with such interpretation, subsequent studies indicated that the phenotype induced by RS on rat hepatocytes in vivo is consistent with the chronic activation of a DNA damage response.50 It also displays several markers of cell senescence including the senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal), the phosphorylated form H2A histone family, member X, p53 binding protein 1, and the ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) gene product, among others.50

Cell senescence implies a stable cell cycle arrest and has long been regarded as a fail-safe mechanism to limit the risk of neoplastic transformation following genotoxic insult.51 However, it is now evident from several studies that the presence of senescent cells in tissues can also fuel carcinogenesis, possibly via components of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which includes cytokines, growth factors and matrix-remodeling enzymes,52 and/or through release of extracellular vesicles or cytoplasmic bridging, which have also been reported to occur in cell senescence 53–55

Thus, cell senescence and the concomitant SASP stand as possible mediators for the growth stimulation of transplanted nodular hepatocytes in RS-exposed liver tissue.49

The Tumor-Promoting Effect of the Aged Tissue Environment

The finding of cell senescence in a chemically induced tissue environment that is supportive for the growth of preneoplastic cell populations raises an important question: Are aged organs, which typically harbor senescent cells, also characterized by the emergence of a neoplastic-prone tissue landscape, that is, conducive to selection of altered/preneoplastic cells? Studies reported by McCullough et al. over 20 y ago suggested such possibility.56 Neoplastically transformed epithelial cell lines, generated in vitro and transferred into the liver of syngeneic recipients of different age, expressed their full tumorigenic potential only in aged hosts, while their growth was suppressed upon injection into young animals.56 These results were highly intriguing. However, their interpretation in the context of the present discussion is rather difficult, given that cells were already neoplastic at the time of transplantation, and their responsiveness to any tissue environmental cues might therefore be different compared to preneoplastic counterparts. Furthermore, they were of in vitro origin, adding uncertainty to their potential relevance to the process as it occurs in vivo. Nevertheless, this type of evidence laid the grounds for a direct testing of the hypothesis that advancing age might be associated with alterations in the tissue environment, which are conducive to the selective growth of putative preneoplastic cells.

Taking advantage of the experimental setting described in the preceding paragraphs, we have recently explored this possibility. Cells isolated from preneoplastic nodules were infused into the livers of rats of different ages, and their fate was followed over time using the histochemical marker DPPIV.46 Results were unequivocal: The very limited growth of transplanted primary nodular hepatocytes was seen in the liver of young (3- to 5-mo-old) hosts over a period of 8 mo, as reported in previous studies.46 On the other hand, the same preneoplastic cells formed visible nodules in the majority of recipients (17/18) following infusion into the livers of aged (18- to 20-mo-old) syngeneic rats.57 It should be mentioned that in both groups, cells were injected through the portal circulation and they were therefore seeded in the liver parenchyma mainly as single hepatocytes, with ample possibility to interact with the host tissue environment.

As expected, aged liver showed increased expression of SA-β-gal. However, other markers that are often associated with cell senescence were not found to be elevated in old recipients. Thus, whether senescent cells and/or their SASP components are involved in the promoting effect exerted by the aged liver microenvironment on transplanted preneoplastic hepatocytes remains an important question to be investigated in future studies.

Once again, some analogies with the above findings are present in studies on mouse leukemogenesis carried out in DeGregori’s research laboratories.58 It was reported that the reduced fitness of B lymphopoiesis associated with aging selects for the emergence of cells with favorable oncogenic mutations, increasing the risk of leukemia in the old animal. Thus, while the decline in the fitness of B lymphopoiesis in aged mice coincided with altered receptor-associated kinase signaling, the fusion protein Bcr-Abl provided a much greater competitive advantage to old B-lymphoid progenitors compared with young progenitors, restoring kinase signaling pathways. Such enhanced competitive advantage translated into increased promotion of Bcr-Abl-driven leukemias Furthermore, a chronic inflammatory milieu in the aged bone marrow appears to be involved in the genesis of the reduced fitness phenotype of B cell progenitors.59

A decline in the ability of the aged liver to recover its mass following tissue loss has been reported by several studies.33,60 Replicative capacity is an important functional attribute of the differentiated hepatocyte, given the potential exposure of the liver to dietary-born toxins or metabolic insults.61 It is noteworthy that hepatocytes isolated from old donors were found to express a cell autonomous decrease in proliferative potential upon transplantation under strong selective conditions in vivo.62 It is therefore reasonable to propose that an aged tissue landscape, endowed with reduced cell replicative capacity, might facilitate the selective expansion of a more competitive cell population, such as the preneoplastic hepatocytes. This hypothetical scenario would be in line with the interpretation suggested for mouse leukemogenesis.58

The Aged Liver Microenvironment Supports the Growth of Normal Transplanted Hepatocytes

The evidence discussed thus far suggests the existence of a pathogenetic link between a low-fitness/aged tissue landscape and the selective growth of preneoplastic cell populations. The microenvironment of an aged/growth-constrained liver appears to be able to generate stimuli that are conducive to the emergence of altered cells, increasing the risk of neoplastic disease. A crucial question at this point is whether these stimulatory signals bear any specificity toward altered/preneoplastic hepatocytes or, alternatively, if they can also sustain the growth of normal cell counterparts. Answering this question is important on 2 grounds. (i) It may shed light on the nature of phenotypic differences between normal and preneoplastic hepatocytes and/or (ii) it may help defining biological and molecular mechanisms mediating the stimulatory effect of the aged microenvironment on the growth of preneoplastic cells. For example, if cell senescence and/or SASP have a major role in this phenomenon, one would expect to observe some specificity of the effect toward preneoplastic cells. In fact, several reports associate the secretory activity of senescent cells to promotion of carcinogenesis.63,64 However, no studies thus far have linked SASP components and/or other phenotypic features of senescent cells to normal tissue proliferation and/or regeneration.

Given such premises, the fate of normal hepatocytes transplanted in the liver of either young or old recipients becomes a significant issue. Results obtained by our research group provided the first evidence that the microenvironment of the aged rat liver is indeed able to foster the clonal expansion of transplanted normal hepatocytes, while the same cells displayed very limited growth upon infusion into the liver of young hosts.65 Analogous findings were reported later by Menthena et al.66 They transplanted cells isolated from fetal rat liver in syngeneic recipients of different age and observed at 4- to 5-fold increase in the size of donor-derived cell clusters in older hosts.

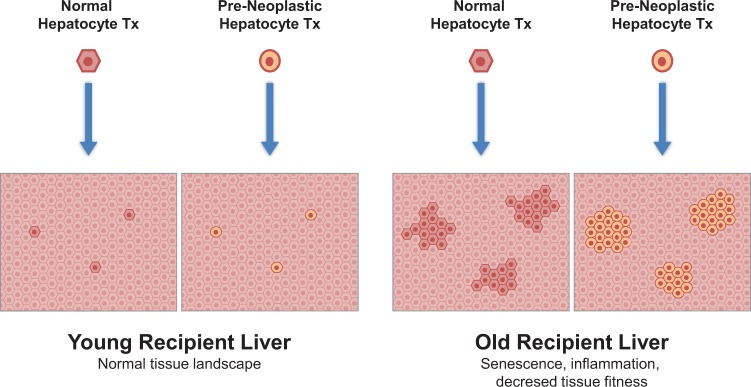

From the foregoing, it is justified to conclude that the same tissue environment of the aged liver, which is able to promote the growth of preneoplastic hepatocytes, exerts a seemingly comparable effect on bona fide normal hepatocytes (Fig. 1). Importantly, no signs of neoplastic transformation were seen with the latter cell type after over 2 y of observation.65,66

Fig. 1.

Neither normal nor primary preneoplastic hepatocytes grow to any significant extent upon transplantation into the liver of young syngeneic hosts. However, selective expansion of both cell types is seen in the liver of aged recipients.47,56

The above conclusion is further supported by the striking results obtained when normal hepatocytes are transplanted into the growth-constrained/low-fitness microenvironment induced in the liver following exposure to RS. As mentioned in the preceding discussion, such treatment imposes a long-lasting block on hepatocyte cell cycle and generates a powerful driving force for the rapid expansion of transplanted preneoplastic hepatocytes, leading to their progression to cancer. When normal hepatocytes are infused in RS-treated liver, they also proliferate extensively, setting out a most remarkable process, which culminates in the massive repopulation of the host liver by the donor-derived cell progeny.67 Furthermore, the repopulated liver shows a normal histology and performs normal functions for the entire lifespan of the recipient animal.68

Taken together, these findings strongly indicate that both the age-associated and the RS-induced low-fitness liver microenvironments, which represent neoplastic-prone tissue landscapes, are also supportive for the growth of phenotypically normal cells. In light of such evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that similar mechanisms are likely to be involved in the selective expansion of both normal and preneoplastic hepatocytes under the experimental conditions referred to above.67 If cell senescence and/or SASP components do play a role in this context,50 this would imply that they are also able to exert an effect on normal cell and tissue regeneration, adding a possible new facet to the biological significance of cell senescence.

On the other hand, the emergence of either normal or preneoplastic hepatocytes in a background of decreased tissue fitness suggests that mechanisms of cell competition could be at play. This was in fact suggested by Menthena et al. to explain the selective expansion of fetal hepatic cells in the livers of aged recipients.65 Cell competition is now recognized as a pervasive biological mechanism allowing for clearance of cells that, although viable, are less fit than their neighbors.69 As such, it is thought to be involved in several pathophysiological processes.70 Interestingly, it has been reported that in epithelial tissues, normal cells sense and actively eliminate the neighboring transformed cells via cytoskeletal proteins by a process that has been referred to as epithelial defense against cancer, which is interpreted as a form of cell competition.71 However, in a tissue landscape with widespread decreased fitness in “normal” cells, rare “mutants” with favorable alterations may take the lead and set in motion a process that could result in “adaptive oncogenesis”.42,43 Within this conceptual framework, it is noteworthy that normal cells, endowed with normal fitness, can also act as efficient competitors when tissue function is compromised, as documented in the preceding discussion.

Normal Cell Transplantation Delays Carcinogenesis

As an important corollary to the above interpretation, it is possible to predict that normal cells could in fact be exploited in a cell competition strategy to counteract the emergence of altered/preneoplastic cells, under conditions of overall decreased tissue fitness, most notably with reference to proliferative capacity. Stated otherwise, regenerative medicine could come to the rescue by abolishing or limiting the competitive advantage of altered cells in a growth-compromised tissue landscape.

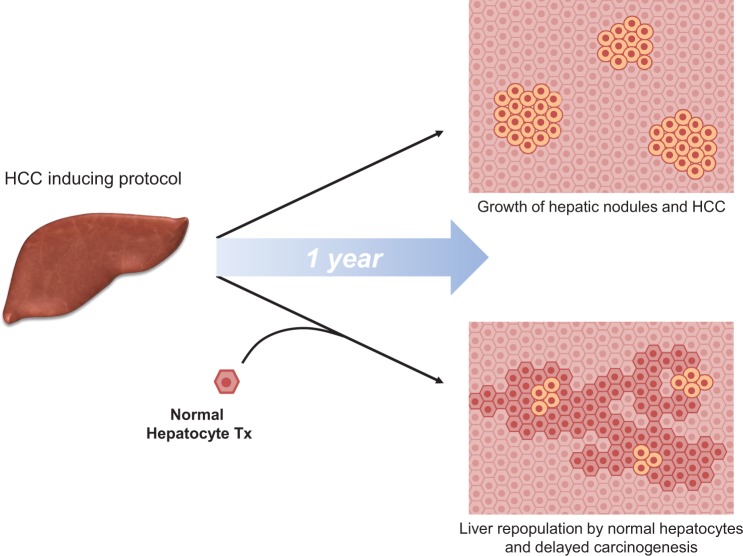

Recent findings suggest such a possibility.72 Animals were initially exposed to a protocol for the induction of HCC followed by transplantation of normal hepatocytes. The latter resulted in extensive repopulation of the host liver and a prominent decrease in the incidence of both preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions compared to the control group not receiving transplantation (Fig. 2).72 Further studies revealed that extensive hepatocyte senescence was induced by the carcinogenic protocol in the host liver; however, senescent cells were largely cleared and replaced following infusion of normal hepatocytes, and this was associated with a decrease in the levels of the inflammatory cytokine (and main SASP component) interleukin 6.72

Fig. 2.

Normal hepatocyte transplantation delays chemically induced liver carcinogenesis.62

Clearly, the above results cannot be taken to suggest that regenerative medicine, by means of normal cell transplantation, is a realistic option to be applied in the context of neoplastic disease, either in experimental models or, more to the point, in the clinical setting. However, they serve to reinforce the notion that strategies aimed at normalizing a neoplastic-prone tissue landscape, including age-associated tissue microenvironments, can modulate the evolution of neoplastic disease.

Concluding Remarks

We have discussed evidence to indicate that age-associated alterations in the tissue microenvironment contribute to the emergence of a neoplastic-prone tissue landscape, which is able to promote the selective growth of preneoplastic cell populations. Possible mechanisms responsible for this effect are the accumulation of senescent cells and/or their release of secretory products, including pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors. Alternately, or in combination, an age-associated progressive decrease in tissue fitness, notably proliferative fitness, may favor the emergence of more competitive cell variants, which might harbor proneoplastic genetic/epigenetic alterations. This process can be interpreted as “adaptive oncogenesis.”

Interestingly, tissue contexts that are able to select for the growth of preneoplastic cells, including the aged liver microenvironment, are also supportive for the clonal expansion of normal, homotypic, transplanted cells. This suggests that the growth of normal and preneoplastic cells is probably driven by similar mechanisms, implying that strategies based on principles of regenerative medicine might be applicable to modulate neoplastic disease.

As it has been aptly remarked, if aging is the strongest risk factor for cancer, the immediate implication is that the best protection against cancer is to be young.73 Most importantly, the finding that aging and cancer are not just coincidentally associated but are profoundly interrelated in their pathogenetic pathways leads to the suggestion that the most effective strategy to prevent cancer is by promoting healthy chronological aging and delaying biological aging.74

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Part of the work referred to in this review was supported by AIRC (Italian Association for Cancer Research, Grant No. IG 10604) and by Sardinian Regional Government (RAS).

References

- 1. Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span—from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328(5976):321–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin GM. Cellular aging—postreplicative cells. A review (Part II). Am J Pathol. 1977;89(2):513–530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yin D, Chen K. The essential mechanisms of aging: Irreparable damage accumulation of biochemical side-reactions. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40(6):455–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soskić V, Groebe K, Schrattenholz A. Nonenzymatic posttranslational protein modifications in ageing. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43(4):247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Proteostasis and aging. Nat Med. 2015;21(12):1406–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feldman DE, Frydman J. Protein folding in vivo: the importance of molecular chaperones. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10(1):26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma Y, Li J. Metabolic shifts during aging and pathology. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(2):667–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vanhooren V, Navarrete Santos A, Voutetakis K, Petropoulos I, Libert C, Simm A, Gonos ES, Friguet B. Protein modification and maintenance systems as biomarkers of ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2015;151:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hipp MS, Park SH, Hartl FU. Proteostasis impairment in protein-misfolding and aggregation diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(9):506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shah PP, Donahue G, Otte GL, Capell BC, Nelson DM, Cao K, Aggarwala V, Cruickshanks HA, Rai TS, McBryan T, et al. Lamin B1 depletion in senescent cells triggers large-scale changes in gene expression and the chromatin landscape. Genes Dev. 2013;27(16):1787–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fougère B, Boulanger E, Nourhashémi F, Guyonnet S, Cesari M. Chronic inflammation: accelerator of biological aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 Dec 21. pii: glw240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sen P, Shah PP, Nativio R, Berger SL. Epigenetic mechanisms of longevity and aging. Cell. 2016;166(4):822–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dang W, Steffen KK, Perry R, Dorsey JA, Johnson FB, Shilatifard A, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy BK, Berger SL. Histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation regulates cellular lifespan. Nature. 2009;459(7248):802–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Sullivan RJ, Kubicek S, Schreiber SL, Karlseder J. Reduced histone biosynthesis and chromatin changes arising from a damage signal at telomeres. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(10):1218–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10): R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horvath S. Erratum to: DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2015;16:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freund A, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Campisi J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(11):2066–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shimi T, Butin-Israeli V, Adam SA, Hamanaka RB, Goldman AE, Lucas CA, Shumaker DK, Kosak ST, Chandel NS, Goldman RD. The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev. 2011;25(24):2579–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Monti D, Ostan R, Borelli V, Castellani G, Franceschi C. Inflammaging and omics in human longevity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2016. December 27 pii: S0047-6374(16)30261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gensler HL, Bernstein H. DNA damage as the primary cause of aging. Q Rev Biol. 1981;56(3):279–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holmes GE, Bernstein C, Bernstein H. Oxidative and other DNA damages as the basis of aging: a review. Mutat Res. 1992;275(3-6):305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. White RR, Vijg J. Do DNA double-strand breaks drive aging? Mol Cell. 2016;63(5):729–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lenart P, Krejci L. Reprint of “DNA, the central molecule of aging”. Mutat Res. 2016;788:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gravina S, Sedivy JM, Vijg J. The dark side of circulating nucleic acids. Aging Cell. 2016;15(3):398–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vijg J. Aging genomes: a necessary evil in the logic of life. Bioessays. 2014;36(3):282–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sedelnikova OA, Horikawa I, Zimonjic DB, Popescu NC, Bonner WM, Barrett JC. Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(2):168–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maisnier-Patin S, Roth JR, Fredriksson A, Nyström T, Berg OG, Andersson DI. Genomic buffering mitigates the effects of deleterious mutations in bacteria. Nat Genet. 2005;37(12):1376–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. López-Otín C, Galluzzi L, Freije JM, Madeo F, Kroemer G. Metabolic control of longevity. Cell. 2016;166(4):802–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gladyshev VN. Aging: progressive decline in fitness due to the rising deleteriome adjusted by genetic, environmental, and stochastic processes. Aging Cell. 2016;15(4):594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang R, Chen HZ, Liu DP. The four layers of aging. Cell Syst. 2015;1(3):180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sousounis K, Baddour JA, Tsonis PA. Aging and regeneration in vertebrates. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2014;108:217–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Timchenko NA. Aging and liver regeneration. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(4):171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Madia F, Wei M, Yuan V, Hu J, Gattazzo C, Pham P, Goodman MF, Longo VD. Oncogene homologue Sch9 promotes age-dependent mutations by a superoxide and Rev1/Polzeta-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2009;186(4):509–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martincorena I, Campbell PJ. Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells. Science. 2015;349(6255):1483–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hernandez-Gea V, Toffanin S, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Role of the microenvironment in the pathogenesis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(3):512–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Galun E. Liver inflammation and cancer: the role of tissue microenvironment in generating the tumor-promoting niche (TPN) in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fulop T, Le Page A, Fortin C, Witkowski JM, Dupuis G, Larbi A. Cellular signaling in the aging immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;29:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445(7128):656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kang TW, Yevsa T, Woller N, Hoenicke L, Wuestefeld T, Dauch D, Hohmeyer A, Gereke M, Rudalska R, Potapova A, et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature. 2011;479(7374):547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lizée G, Radvanyi LG, Overwijk WW, Hwu P. Improving antitumor immune responses by circumventing immunoregulatory cells and mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(16):4794–4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pasero C, Gravis G, Guerin M, Granjeaud S, Thomassin-Piana J, Rocchi P, Paciencia-Gros M, Poizat F, Bentobji M, Azario-Cheillan F, et al. Inherent and tumor-driven immune tolerance in the prostate microenvironment impairs natural killer cell antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2016;76(8):2153–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Farber E, Rubin H. Cellular adaptation in the origin and development of cancer. Cancer Res. 1991;51(11):2751–2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fleenor CJ, Higa K, Weil MM, DeGregori J. Evolved cellular mechanisms to respond to genotoxic insults: implications for radiation-induced hematologic malignancies. Radiat Res. 2015;184(4):341–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mattocks AR. Toxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Nature. 1968;217(5130):723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Laconi S, Curreli F, Diana S, Pasciu D, De Filippo G, Sarma DS, Pani P, Laconi E. Liver regeneration in response to partial hepatectomy in rats treated with retrorsine: a kinetic study. J Hepatol. 1999;31(6):1069–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Laconi S, Pani P, Pillai S, Pasciu D, Sarma DS, Laconi E. A growth-constrained environment drives tumor progression in vivo . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(14):7806–7811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marusyk A, Casás-Selves M, Henry CJ, Zaberezhnyy V, Klawitter J, Christians U, DeGregori J. Irradiation alters selection for oncogenic mutations in hematopoietic progenitors. Cancer Res. 2009;69(18):7262–7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang YP, Fu PP, Chou MW. Metabolic activation of the tumorigenic pyrrolizidine alkaloid, retrorsine, leading to DNA adduct formation in vivo. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2005;2(1):74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhu L, Xue J, Xia Q, Fu PP, Lin G. The long persistence of pyrrolizidine alkaloid-derived DNA adducts in vivo: kinetic study following single and multiple exposures in male ICR mice. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91(2):949–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Serra MP, Marongiu F, Sini M, Laconi E. Hepatocyte senescence in vivo following preconditioning for liver repopulation. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):760–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Braig M, Schmitt CA. Oncogene-induced senescence: putting the brakes on tumor development. Cancer Res. 2006;66(6):2881–2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):2853–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Effenberger T, von der Heyde J, Bartsch K, Garbers C, Schulze-Osthoff K, Chalaris A, Murphy G, Rose-John S, Rabe B. Senescence-associated release of transmembrane proteins involves proteolytic processing by ADAM17 and microvesicle shedding. FASEB J. 2014;28(11):4847–4856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lehmann BD, Paine MS, Brooks AM, McCubrey JA, Renegar RH, Wang R, Terrian DM. Senescence-associated exosome release from human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(19):7864–7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Biran A, Perelmutter M, Gal H, Burton DG, Ovadya Y, Vadai E, Geiger T, Krizhanovsky V. Senescent cells communicate via intercellular protein transfer. Genes Dev. 2015;29(8):791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McCullough KD, Coleman WB, Smith GJ, Grisham JW. Age-dependent regulation of the tumorigenic potential of neoplastically transformed rat liver epithelial cells by the liver microenvironment. Cancer Res. 1994;54(14):3668–3671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Marongiu F, Serra MP, Doratiotto S, Sini M, Fanti M, Cadoni E, Serra M, Laconi E. Aging promotes neoplastic disease through effects on the tissue microenvironment. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(12):3390–3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Henry CJ, Marusyk A, Zaberezhnyy V, Adane B, DeGregori J. Declining lymphoid progenitor fitness promotes aging-associated leukemogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(50):21713–21718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Henry CJ, Casás-Selves M, Kim J, Zaberezhnyy V, Aghili L, Daniel AE, Jimenez L, Azam T, McNamee EN, Clambey ET, et al. Aging-associated inflammation promotes selection for adaptive oncogenic events in B cell progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(12):4666–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bucher NLR, Swaffield MN, DiTroia JF. The influence of age upon the incorporation of thymidine-2-C14 into the DNA of regenerating rat liver. Cancer Res. 1964;24(3):509–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huang J, Rudnick DA. Elucidating the metabolic regulation of liver regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2014;184(2):309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Serra MP, Marongiu F, Marongiu M, Contini A, Laconi E. Cell-autonomous decrease in proliferative competitiveness of the aged hepatocyte. J Hepatol. 2015;62(6):1341–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pérez-Mancera PA, Young AR, Narita M. Inside and out: the activities of senescence in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(8):547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Loaiza N, Demaria M. Cellular senescence and tumor promotion: Is aging the key? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1865(2):155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pasciu D, Montisci S, Greco M, Doratiotto S, Pitzalis S, Pani P, Laconi S, Laconi E. Aging is associated with increased clonogenic potential in rat liver in vivo. Aging Cell. 2006;5(5):373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Menthena A, Koehler CI, Sandhu JS, Yovchev MI, Hurston E, Shafritz DA, Oertel M. Activin A, p15INK4b signaling, and cell competition promote stem/progenitor cell repopulation of livers in aging rats. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):1009–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Marongiu F, Doratiotto S, Montisci S, Pani P, Laconi E. Liver repopulation and carcinogenesis: two sides of the same coin? Am J Pathol. 2008;172(4):857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Laconi S, Montisci S, Doratiotto S, Greco M, Pasciu D, Pillai S, Pani P, Laconi E. Liver repopulation by transplanted hepatocytes and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation. 2006;82(10):1319–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Di Gregorio A, Bowling S, Rodriguez TA. Cell competition and its role in the regulation of cell fitness from development to cancer. Dev Cell. 2016;38(6):621–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Merino MM, Levayer R, Moreno E. Survival of the fittest: essential roles of cell competition in development, aging, and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(10):776–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kajita M, Fujita Y. EDAC: epithelial defence against cancer-cell competition between normal and transformed epithelial cells in mammals. J Biochem. 2015;158(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Marongiu F, Serra MP, Sini M, Angius F, Laconi E. Clearance of senescent hepatocytes in a neoplastic-prone microenvironment delays the emergence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 2014;6(1):26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Serrano M. Unraveling the links between cancer and aging. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37(2):107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kaeberlein M, Rabinovitch PS, Martin GM. Healthy aging: the ultimate preventative medicine. Science. 2015;350(6265):1191–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]