Abstract

Background

Smoking prevalence is doubled among people with mental health problems and reaches 80% in inpatient, substance misuse and prison settings, widening inequalities in morbidity and mortality. As more institutions become smoke-free but most smokers relapse immediately post-discharge, we aimed to review interventions to maintain abstinence post-discharge.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Web of Science were searched from inception to May 2016 and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies conducted with adult smokers in prison, inpatient mental health or substance use treatment included. Risk of bias (study quality) was rated using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Tool. Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were coded from published papers and manuals using a published taxonomy. Mantel-Haenszel random effects meta-analyses of RCTs used biochemically verified point-prevalence smoking abstinence at a) longest and b) six-month follow-up.

Results

Five RCTs (n=416 intervention, n=415 control) and five cohort studies (n=471) included. Regarding study quality, four RCTs were rated strong, one moderate; one cohort study was rated strong, one moderate, three weak. Most common BCTs were pharmacotherapy (n=8 nicotine replacement therapy, n=1 clonidine), problem solving, social support, and elicitation of pros and cons (each n=6); papers reported fewer techniques than manuals. Meta-analyses found effects in favour of intervention [a) RR=2.06, 95% CI: 1.30-3.27; b) RR=1.86, 95% CI: 1.04-3.31].

Conclusion

Medication and/or behavioural support can help maintain smoking abstinence beyond discharge from smoke-free institutions with high mental health comorbidity. However, the small evidence base tested few different interventions and reporting of behavioural interventions is often imprecise.

Introduction

Smoking prevalence among people with mental health problems is about twice as high as in the population as a whole and increases with severity of illness, in some instances reaching up to 80% (McManus S, 2016, Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2013). Smoking prevalence in those with mental health problems has not seen the same decline as in the general population (Cook et al., 2014, Szatkowski and McNeill, 2015). Smoking is the main contributor to a gap in life expectancy of 8 to 22 years between those with and without mental health problems (Brown et al., 2010, Chang et al., 2011, Lawrence et al., 2013, Tam et al., 2016, Wahlbeck et al., 2011). This affects a large number of people as it has been estimated that one third of smokers have a mental health problem (Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2013). Prevalence of smoking and mental health problems is also higher among other disadvantaged groups, such as offenders and people with drug and alcohol dependence (Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2013) in prisons and substance use treatment settings, smoking prevalence in excess of 80% has been observed in some countries (Hickman et al., 2015). Evidence suggests that cessation benefits not just physical, but also mental health (Taylor et al., 2014).

Recently, some efforts to address this inequality have been made, including the introduction of comprehensive smoke-free policies in secondary care settings and prisons (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013, Working Group for Improving the Physical Health of People with SMI, 2016), ideally involving both smoke-free policies in buildings and grounds and integrated treatment for temporary abstinence and quitting (Kleber et al., 2007, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013, Working Group for Improving the Physical Health of People with SMI, 2016). Staying in a smoke-free facility can provide a possibly rare period of abstinence from smoking and provides an opportunity to initiate long-term change to reduce morbidity and mortality. However, the risk of relapse after leaving is extremely high (Clarke et al., 2013, Prochaska et al., 2006) and there appears to be little routine support to maintain abstinence and little evidence on interventions that may reduce the risk of reverting to smoking. An existing review of interventions to maintain abstinence in hospitalised patients (Rigotti et al., 2012) specifically excluded patients from facilities that predominantly treat psychiatric conditions or substance abuse, meaning there is a particular lack of information on the extant evidence in these disadvantaged populations. One previous review summarised the impact of smoke-free psychiatric hospitalization on patients’ smoking (Stockings et al., 2014a). Institutions with incomplete smoke-free policies that were not necessarily providing any behavioural or pharmacological support to achieve abstinence were included in the review and the authors concluded that adherence to the smoke-free policy and receipt of treatment are likely to be important factors for patients’ smoking.

We aimed to systematically review randomised controlled trials and cohort studies to identify pharmacological or behavioural interventions provided during the stay or post-discharge to maintain abstinence in smokers after a period of enforced abstinence in smoke-free facilities for mental health, substance misuse treatment centres or prisons. A secondary aim was to identify intervention components to guide development of future interventions.

Methods

The review is registered as PROSPERO 2016:CRD42016041840.

Inclusion criteria

The review included randomised controlled trials (including feasibility and pilot trials) and observational cohort studies with participants who were adult smokers (18 or older), abstinent because of a stay in a smoke-free prison, mental health or substance use treatment centre and followed up post-discharge. Institutions with partial smoke-free policies were included if participants had no access to smoking areas. In addition to a smoke-free setting, at least minimal support had to be offered. This could include any type of behavioural or pharmacological intervention aimed at maintaining abstinence from smoking following discharge, delivered during the stay and/or post-discharge. No limits were applied to control conditions where applicable.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome:

Biochemically verified continuous smoking abstinence at longest follow-up (West et al., 2005).

Secondary outcomes:

Biochemically verified continuous smoking abstinence at six months

Biochemically verified point-prevalence (seven-day) smoking abstinence at longest follow-up

Biochemically verified point-prevalence smoking abstinence at six months

Self-reported continuous abstinence at longest follow-up

Self-reported continuous smoking abstinence at six months.

Self-reported point-prevalence abstinence at longest follow-up

Self-reported point prevalence smoking abstinence at six months

Other changes in smoking behaviour: a. Time to first cigarette post-discharge; b. Change in cigarette consumption at follow-up compared with the period prior to the enforced abstinence.

Search strategy and selection of studies

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science were searched up to 25 May 2016. The search strategy included search terms relating to the population (smokers, mental health or substance use inpatients or prisoners), intervention (smoking cessation), outcome (relapse, maintenance) and study types (cohort studies, clinical trials). Searches were limited to studies in English and adults. A full search strategy is in the online supplement (A1). Endnote X7 was used to record publications at all stages of the selection process. One reviewer (ES) screened all titles and abstracts of studies. Full text screening was undertaken by three authors; two reviewers (ES and LB) independently screened all papers and disagreements were settled by a third reviewer (AMcN); Kappa was calculated as a measure of agreement.

Data extraction

Using a pre-defined table, relevant data were extracted from all included studies by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias (study quality) was assessed independently by two reviewers using the Effective Public Health Practice Project tool (EPHPP). The tool has been designed to assess different study designs including randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. It consists of six sections: a) selection bias, b) study design, c) confounders, d) blinding, e) data collection method, f) withdrawals and dropouts; each section is rated as strong, moderate or weak. A study is rated as overall of strong quality if no section has been rated weak, moderate if one section is rated weak, and weak if two or more sections have been rated weak (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012). Differences in assessment were discussed to arrive at an agreed assessment.

Data synthesis

For trials, two pre-specified Mantel-Haenszel random effects meta-analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.3 (Higgins and Green, 2011). The strongest available outcomes were used. For both analyses, those lost to follow-up were treated as non-abstinent with the exception of nine deceased participants (West et al., 2005). Subgroup analyses by setting (prison, substance abuse, mental health) were planned. Observational studies were summarised in a narrative synthesis. Intervention components were coded using the Behaviour Change Technique (BCT) taxonomy (Michie et al., 2015) which defines 93 behaviour change techniques organised into 16 clusters Authors of eight studies were contacted for treatment manuals or treatment protocols as evidence indicates that descriptions in published papers are less comprehensive (Lorencatto et al., 2013); authors for the remaining two studies could not be contacted (Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Joseph, 1993). A manual used in one trial (Clarke et al., 2013), a manual used in two trials (Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014) and detailed descriptions for another trial (Stockings et al., 2014b) and two cohort studies (Strong et al., 2012, Stuyt, 2015) were provided; interventions in the other four studies were coded based on descriptions in the published papers. It was explored whether any link between behaviour change techniques used and outcomes of interventions could be hypothesised.

Results

Description of studies

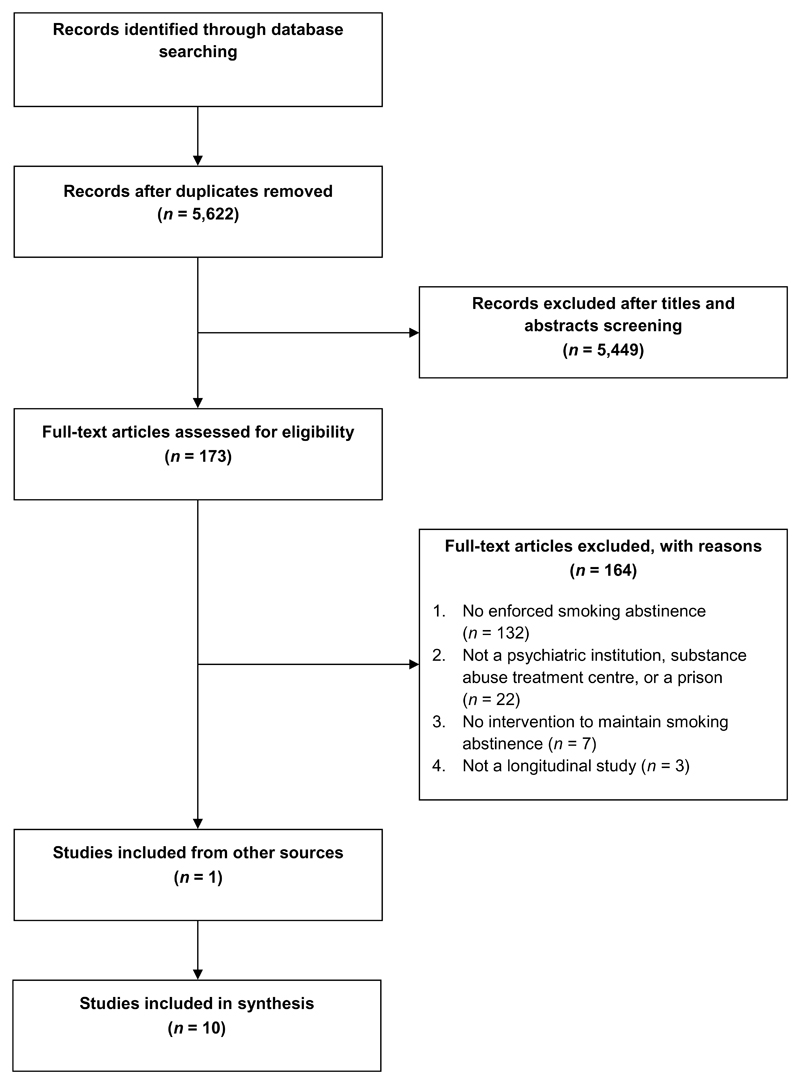

The search identified 8,417 records; ten studies with a total N=1302 were included in the review (Figure 1). Eight studies had been selected by both initial reviewers; kappa was 0.71.

Figure 1.

Study selection

Five studies (Clarke et al., 2013, Gariti et al., 2002, Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014, Stockings et al., 2014b) were trials (intervention n=416, control n=415), five (Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Joseph, 1993, Prochaska et al., 2006, Strong et al., 2012, Stuyt, 2015) were observational cohort studies (n=471). One study was conducted in Australia (Stockings et al., 2014b), all others in the US. One trial was conducted in a prison (Clarke et al., 2013), one trial and one cohort study in substance use treatment settings (Gariti et al., 2002, Joseph, 1993), two trials and three cohort studies in mental health treatment settings (Hickman et al., 2015, Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Prochaska et al., 2006, Prochaska et al., 2014, Strong et al., 2012) and one trial and one cohort study in mixed substance use and mental health settings (Stockings et al., 2014b, Stuyt, 2015).

All institutions were described as having complete smoke-free policies and the average length of stay in the smoke-free environment differed considerably; it was 1.5 years in the prison setting (Clarke et al., 2013), while all other studies measured the stay in days and the next longest was 90 days (Stuyt, 2015). Follow-up periods ranged from 3 months (Clarke et al., 2013) to 18 months (Prochaska et al., 2014) (Table 1). All randomised trials (Clarke et al., 2013, Gariti et al., 2002, Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014, Stockings et al., 2014b) and two of the observational cohort studies (Prochaska et al., 2006, Strong et al., 2012) used biochemically verified measures of seven-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence; the other three used self-reported abstinence (Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Joseph, 1993, Stuyt, 2015); only one trial reported continuous as well as point-prevalence abstinence ( et al., 2014b).

Table 1.

Study description

| Authors, publication details | Setting, country, n | Length of stay, intervention format, provider, mode | Inpatient intervention behaviour change techniques b, c (Michie et al., 2015) | Post-discharge behaviour change techniques c | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised controlled trials | |||||

| Clarke et al., JAMA Intern Med., 2013a (study protocol (Clarke et al., 2011)) | Prison, US, n=247 |

Length of stay: Measured as time since last cigarette smoked, M (SD) = 1.5 (3.4) years Inpatient: 6 sessions, sessions 1 and 6 based on Motivational Interviewing, sessions 2 to 5 based on CBT, delivered by Research Assistants, one-to-one. Post-discharge: Telephone calls 24 hours and 7 days post-discharge |

1.1 Goal setting (behaviour) 1.2 Problem solving 1.4 Action planning 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 3.3 Social support (emotional) 4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behaviour 4.2 Information about antecedents 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.4 Monitoring of emotional consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 7.4 Remove access to the reward 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal 8.2 Behaviour substitution 8.3 Habit formation 8.4 Habit reversal 9.2 Pros and cons 9.3 Comparative imagining of future outcomes 11.2 Reduce negative emotions 11.3 Conserving mental resources 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment 12.2 Restructuring the social environment 12.3 Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour 12.6 Body changes 13.2 Framing/reframing 13.4 Valued self-identity 13.5 Identity associated with changed behaviour 15.2 Mental rehearsal of successful performance 15.3 Focus on past success 15.4 Self-talk 16.2 Imaginary reward |

1.5 Review behaviour goal(s) 1.7 Review outcome goal(s) 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 10.4 Social reward |

Inpatient: Videos on health-related topics but not about smoking cessation. Post-discharge: Telephone calls 24 hours and 7 days post-discharge. |

| Gariti et al., Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 2002 | Veterans Affairs Medical Center’s detoxification unit for alcohol and other non-nicotine drugs, US, n=62 |

Length of stay: M = 7.4 days. Inpatient: One manual-based individual session delivered by Addiction Therapist, one-to-one. Participants encouraged to attend daily film series, Motivational enhancement (MET) post-film discussion in group. Post-discharge: Optional smoking cessation program delivered face-to-face by study co-investigator or nurse practitioner |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 6.1 Demonstration of the behaviour 9.2 Pros and cons 11.1 Pharmacological support (nicotine patch |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 11.1 Pharmacological support (nicotine patch) |

Inpatient and post-discharge: 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 11.1 Pharmacological support (nicotine patch) Optional smoking cessation program delivered face-to-face by study co-investigator or nurse practitioner |

| Hickman et al., Nicotine Tob Res, 2015a | Three psychiatric units (one non-acute and two acute units) in public acute care hospital, US, n=100 (3 deaths during follow-up) |

Length of stay: 47% stayed 2-7 days, 30% 8-13 days, 23% 2 weeks or longer Inpatient: Transtheoretical model-tailored computer-delivered intervention, self-help information, 15–30 minute on-unit individual motivational enhancement cessation counselling, delivered by study staff Post-discharge: Computer intervention repeated at 3 and 6 months, optional NRT for up to 10 weeks |

1.1 Goal setting (behaviour) 1.2 Problem solving 1.4 Action planning 1.9 Commitment 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 3.3 Social support (emotional) 4.2 Information about antecedents 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 6.2 Social comparison 6.3 Information about others’ approval 7.1 Prompts/cues 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal 8.2 Behaviour substitution 8.7 Graded tasks 9.2 Pros and cons 9.3 Comparative imagining of future outcomes 10.3 Non-specific reward 10.4 Social reward 10.9 Self-reward 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) 11.2 Reduce negative emotions 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment 12.2 Restructuring the social environment 12.3 Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour 12.4 Distraction 12.5 Adding objects to the environment 12.6 Body changes 13.2 Framing/reframing 13.5 Identity associated with changed behaviour 15.2 Mental rehearsal of successful performance 15.3 Focus on past success 15.4 Self-talk 16.2 Imaginary reward |

11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) |

Inpatient: 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) Delivered by study staff Post-discharge: Referrals (without NRT) |

| Prochaska et al., Am J Public Health, 2014a | Locked inpatient psychiatry unit at the Psychiatric Institute, US, n=224 (4 deaths during follow-up) |

Length of stay: M (SD) = 7.4 (5.7) days, median = 6.0, mode = 5 Inpatient: Transtheoretical model-tailored computer-delivered intervention, 15–30 minute on-unit individual motivational enhancement cessation counselling, delivered by study staff Post-discharge: Computer intervention repeated at 3 and 6 months, optional NRT for up to 10 weeks |

1.1 Goal setting (behaviour) 1.2 Problem solving 1.4 Action planning 1.9 Commitment 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 3.3 Social support (emotional) 4.2 Information about antecedents 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 6.2 Social comparison 6.3 Information about others’ approval 7.1 Prompts/cues 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal 8.2 Behaviour substitution 8.7 Graded tasks 9.2 Pros and cons 9.3 Comparative imagining of future outcomes 10.3 Non-specific reward 10.4 Social reward 10.9 Self-reward 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) 11.2 Reduce negative emotions 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment 12.2 Restructuring the social environment 12.3 Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour 12.4 Distraction 12.5 Adding objects to the environment 12.6 Body changes 13.2 Framing/reframing 13.5 Identity associated with changed behaviour 15.2 Mental rehearsal of successful performance 15.3 Focus on past success 15.4 Self-talk 16.2 Imaginary reward |

11.1 Pharmacological support (nicotine patches) |

Inpatient: 11.1 Pharmacological support (nicotine patches) Post-discharge: No intervention |

| Stockings et al., 2014a (study protocol Stockings et al., 2011) | One comorbid acute mental health and substance use unit and two acute mental health units in public hospital, Australia, n=205 |

Length of stay: M (SD) = 22.6 (78.0) days Inpatient: Self-help smoking cessation literature, 10-15 minutes face-to-face motivational interview, delivered by study staff Post-discharge: 4 months of fortnightly telephone smoking cessation support with a designated counsellor, optional 12-week NRT (choice of patches, gums, lozenges, and inhalers), optional referrals to Quitline or smoking cessation groups |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 9.2 Pros and cons 9.3 Comparative imagining of future outcomes 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) |

1.2 Problem solving 2.1 Monitoring of behaviour without feedback 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behaviour 4.3 Re-attribution 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.4 Monitoring of emotional consequences 7.1 Prompts/cues 8.2 Behaviour substitution 10.4 Social reward 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) 12.2 Restructuring the social environment 12.3 Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour 12.4 Distraction 12.5 Adding objects to the environment |

Inpatient: 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) Delivered by clinic staff Post-discharge: 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT, for three days upon discharge) Post-discharge smoking care plan and optional referral to Quitline |

| Cohort studies | |||||

| Jonas & Eagle, 1991 | Short-term psychiatric unit of a general hospital, US, n=39 |

Length of stay: M (SD) = 14.1 (7.0) days Inpatient: Nicotine gum and education in its use, self-help materials about smoking cessation, delivered by nursing staff Post-discharge: None |

11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT, gum) | ||

| Joseph, 1993 | 21-day residential drug dependency treatment program, US, n=163 |

Length of stay: Not reported; 21-day inpatient program Inpatient: Written agreement to adhere to new smoke-free policy, arranged by clinic staff Post-discharge: None |

1.1 Goal setting (behaviour) 1.8 Behavioural contract 11.1 Pharmacological support (clonidine) |

n/a | n/a |

| Prochaska et al., 2006 | University-based adult inpatient psychiatry unit, US, n=100 |

Length of stay: M (SD) = 6.4 (5.5) days, range = 1-37. Inpatient: Clinic staff provided treatment as usual Post-discharge: Occasionally NRT as part of treatment as usual |

11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT patch and/or gum) | 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) | n/a |

| Strong et al., 2012a | Two inpatient units in a psychiatric hospital, US, n=15 |

Length of stay: M (SD): 7.2 (2.6) days Inpatient: One face-to-face 45 minute Motivational Interviewing session, delivered by study staff, information on quitlines and treatment Post-discharge: Phone call 2 weeks post-discharge |

1.4 Action planning 2.1 Monitoring of behaviour without feedback 2.2 Feedback on behaviour 8.2 Behaviour substitution 9.2 Pros and cons 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) 13.3 Incompatible beliefs 13.4 Valued self-identity |

1.2 Problem solving 1.4 Action planning 1.5 Review behaviour goal(s) 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 10.3 Non-specific reward |

Inpatient: 11.1 Pharmacological support (NRT) Post-discharge: No intervention |

| Stuyt, 2015a | 90-day inpatient treatment program for co-occurring substance abuse and mental health problems, US, n=154 (4 deaths during follow-up) |

Length of stay: Not reported; 90-day inpatient program. Inpatient: Tobacco topic is fully integrated into the program, delivered by centre staff, one-to-one and groups Post-discharge: None described |

1.2 Problem solving 2.5 Monitoring outcome(s) of behaviour by others without feedback 2.6 Biofeedback 4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behaviour 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 11.1 Pharmacological support (Nicotine patch) |

n/a | n/a |

Abbreviations: n = Number of participants, NRT = Nicotine Replacement Therapy; US = United States

Study author(s) provided additional information about study interventions in the form of intervention manuals or similar documents.

In addition to the Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) described in the interventions, a smoke-free environment in itself delivers a number of BCTs for smoking cessation. These include restructuring the physical environment (BCT 12.1), restructuring the social environment (12.2), avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour (12.3) and removing access to the reward (7.4). (Michie et al., 2015)

Number indicates position in clusters; cluster labels are: 1: ‘Goals and planning’, 2 ‘Feedback and monitoring’, 3 ‘Social support’, 4 ‘Shaping knowledge’, 5 ‘Natural consequences’, 6 ‘Comparison of behaviour’, 7 ‘Associations’, 8 ‘Repetition and substitution’, 8 ‘Comparison of outcomes’, 10 ‘Reward and threat’, 11 ‘Regulation’, 12 ‘Antecedents’, 13 ‘Identity’, 14 ‘Scheduled consequences’, 15 ‘Self-belief’, 16 ‘Covert learning’.

Italics: Behaviour change techniques used in intervention but not in control.

Reporting of effects of smoking cessation treatment or continued abstinence from smoking on mental health or substance use varied considerably across studies (Table 2). One trial found rehospitalisation to be less common in the intervention group (Prochaska et al., 2014) and one cohort study found non-smokers to be less likely to relapse to other substances (Stuyt, 2015).

Table 2.

Outcomes of included studies; N = 10.

| Study | Key smoking outcome measures, follow-ups, findings | Variables associated with smoking outcomes | Mental health and other substance use outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised controlled trials | |||

| Clarke et al., 2013 |

Measures Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence verified by urine cotinine level <200 ng/mL; Nicotine dependence (FTND); Time to first cigarette after release Follow-up 3 weeks and 3 months for those abstinent at 3 weeks Findings Abstinence: - 3-weeks: AOR = 6.6, 95% CI: 2.5-17.0 for intervention - 3-months: AOR = 5.3, 95% CI: 1.4-23.8 for intervention Time to first cigarette (3 week follow-up): Treatment main effect: β(SE) = 0.56 (0.16), hazard ratio = 1.75 (p=.001) |

Associated with abstinence at 3-week follow-up Not smoked for >6 months (baseline): AOR=4.6, 95% CI: 1.7-12.4; Hispanic: AOR=3.2, 95% CI: 1.1-8.7; Planned not to smoke after release (baseline): AOR=1.6, 95% CI: 1.2-2.3 |

At 3-week follow-up: Perceived stress (PSS)M (SD) 21.5 (6.1) non-smoker vs 21.9 (6.3) smoker (non-significant); Depression (CES-D) M (SD) : 12.3 (4.9) non-smoker vs 12.8 (5.5) smoker (non-significant) |

| Gariti et al, 2002 |

Measures Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence verified by CO reading ≤ 9 parts per million and urine cotinine level <50 ng/mL; Time to relapse after discharge; Cigarettes per day Follow up 6 months Findings Abstinence: 6% of intervention vs 0% of control (χ2 (1) = 0.002, p = .97); Time to first cigarette: 76% reported smoking the same day they were discharged, 92.7% smoked within a month of discharge, no differences between groups in the mean number of days before relapse, t(52)=0.65, p=.52; Cigarettes per day: Reduced for both groups F(1) = 21.1, p<.001; no differences between groups |

None reported | Almost 47% of participants were abstinent for their primary drug of abuse at the follow up; No differences between groups |

| Hickman et al., 2015 |

Measures Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence verified by CO reading ≤ 10 parts per million or a confirmation of participant’s past 7 days non-smoking status obtained from friends, family, or case managers if a participant was unable to attend in person Follow-up 3, 6, and 12 months Findings Abstinence: - 3 months: 12.5% intervention vs 7.3% control - 6 months: 17.5% intervention vs 8.5% control - 12 months: 26.2% intervention vs 16.7% control Abstinence modelled over 12-month period: AOR = 1.76, 95% CI: 0.69-4.48 for intervention |

Associated with abstinence over 12-month study period Quitting over time: AOR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.04-1.29; Higher social status in United States (baseline): AOR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.04-1.50; Stronger desire to quit (baseline): AOR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.06-1.55; Higher expectation of success with quitting (baseline: AOR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.06-1.50 |

Over the 12 months of follow-up, 55% of control and 57% of intervention group participants were rehospitalised or seen by psychiatric emergency care |

| Prochaska et al., 2014 |

Measures Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence verified by CO reading ≤ 10 parts per million or confirmation of participant’s past 7 days non-smoking status obtained from significant others if the participant was unable to attend in person Follow-up: 3, 6, 12, and 18 months Findings Abstinence: - 3 months: 13.9% intervention vs 3.2% control - 6 months: 14.4% intervention vs 6.5% control - 12 months: 19.4% intervention vs 10.9% control - 18 months: 20.0% intervention vs 7.7% control Abstinence modelled over 18-month period: AOR = 3.85, 95% CI: 1.39-11.11 for intervention (reverse of AOR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.09-0.72 reported by authors) |

Associated with abstinence over 18-month study period Higher expectation of success with quitting (baseline): AOR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.06-1.31; Higher perceived difficulty with staying quit (baseline): AOR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.76-0.97; Time to first cigarette < 30 min (baseline): AOR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.26-0.96 |

Over an 18-month study period, 56% of control and 44% of intervention group participants were rehospitalised, t(223)=2.1, p=.036; this was predicted by: Usual care condition: AOR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.06-3.49; Psychotic symptoms (BASIS-24): AOR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.09-1.89; Unstable housing: AOR = 2.09, 95% CI: 1.12-3.92; ≥8 previous psychiatric hospitalisations vs none: AOR = 3.21, 95% CI: 1.37-7.54 |

| Stockings et al., 2014 |

Measures Self-reported continuous smoking abstinence verified by CO reading < 10 parts per million; Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence verified by CO reading < 10 parts per million; ≥50% reduction in cigarettes per day; Quit attempts after hospitalisation; Nicotine dependence (FTND) Follow-up 1 week and 2, 4, and 6 months Findings Continuous abstinence: - 1-week: 5.8% intervention vs 1% control (p=.06) - 2 months: 2.9% intervention vs 0% control (p=.13) - 4 months: 1.9% intervention vs 0% control (p=.26) - 6 months: 1.9% intervention vs 0% control (p=.26) Point prevalence abstinence (intervention vs control): - 1 week: OR=1.37, 95% CI: 0.45-4.98 - 2 months: OR=2.27, 95% CI: 0.81-7.52 - 4 months: OR=6.46, 95% CI: 1.50-32.77 - 6 months: OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 0.47-4.36 Quit attempts at 6-month follow-up: OR = 2.89, 95% CI: 1.43-5.98 for intervention ≥50% reduction in cigarettes per day at 6-month follow-up: OR = 5.90, 95% CI: 2.89-15.25 for intervention FTND over 6-month period: - Condition-by-time interaction: F(3,406)=8.5, p<.0001 - Main effect of condition: F(1,215)=9.8, p=.002 - Main effect of time: F(3,406)=10.9, p<.0001 |

Use of NRT associated with point prevalence abstinence at 4 months (χ2(3) = 6.8, p=.009), no other significant associations | Psychological distress (K10) over 6-month period: - Condition-by-time interaction: F(3,621)=1.48, p=.22 - Main effect of condition: F(1,621)=.04, p=.85 - Main effect of time: F(3,621)=63.2, p<.0001 |

| Cohort studies | |||

| Jonas & Eagle, 1991 |

Measures Self-reported smoking abstinence; Cigarettes per day; Time to relapse after discharge Follow-up Varying from 6 to 18 months after discharge Findings Abstinence: 4/39 (10.3%) were non-smokers; Relapse: 28/35 (80%) relapsed immediately after discharge, 3/35 (8.6%) within one week, 2/35 (5.7%) one to four weeks, and 2/35 (5.7%) relapsed one month post-discharge |

Associated with abstinence at follow-up M (SD) cigarettes per day (baseline): 6.8 (5) non-smokers vs 23.4 (13.5) smokers, t(34) = 2.4, p<.02 |

None reported |

| Joseph, 1993 |

Measures Self-reported smoking behaviour Follow-up On average 10.7 months post-discharge Findings Abstinence: 13/163 (8%) non-smokers after introduction of smoke-free policy vs 5/156 (3%) (p<.05) before smoke-free policy |

None reported | Use of other substances at follow up: 145/163 (89% with smoke-free policy) vs 151/156 (97% pre-smoke-free policy) reported improvement in chemical dependency (p=.15) |

| Prochaska et al., 2006 |

Measures Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence verified by CO reading ≤ 10 parts per million; Nicotine dependence (FTND); Time to relapse post-discharge; Initiation of quit attempt post-relapse Follow-up 1 week and 1 and 3 months post-discharge Findings Abstinence at 3 months: 4/100 (4%) were non-smokers, although had been relapsed after discharge Relapse: Ranged from seconds to 36 days, 76% reported smoking the same day they were discharged, with a median time to first cigarette of 5 minutes Quit attempts: 48% reported a 24-hour quit attempt after relapsing post-discharge |

Associated with abstinence at 3-month follow up: Less perceived difficulty with staying quit (baseline): F(1,97) = 4.16, p=.044 Associated with relapse on the day of discharge vs later Heavier smoker (baseline): r=.18, p=.047; Higher FTND score: r=.19, p=.043; Stronger craving and urges to smoke during hospitalisation: r=.23, p=.014; Fewer lifetime quit attempts: r=-.19, p=.034; Fewer past year quit attempts: r=-.26, p=.008; Less desire for abstinence: r=-.29, p=.002; Lower expectation of success: r=-.32, p=.001; Pre-contemplation or contemplation vs preparation stage: χ2(2) = 20.12, p<.001; Non-abstinence related goals: OR=.26, p=.016; Depressive disorder: OR=3.3, p=.030 Associated with quit attempt initiation following relapse post-discharge Lower FTND score: r=-.22, p=.019; More past year quit attempts: r=.24, p=.018; Greater desire for abstinence: r=.26, p=.005; Greater expectation of success: r=.21, p=.025; Less perceived difficulty with staying quit (baseline): r=-.24, p=.013; Preparation stage: OR=5.7, p=.002; Goal of complete abstinence: OR=5.4, p=.003; NRT use post-discharge: OR=6.9, p<.001 Not smoking on the day of discharge: OR=6.7, p=.001 |

During the 3-month follow-up period, 81% of participants had a mental health contact, 1/3 of them were rehospitalised. Rehospitalisation was not related to quit attempts. |

| Strong et al., 2012 |

Measures Self-reported 7-day smoking abstinence verified by CO reading < 8 parts per million; Quit attempt made and length of attempt; Cigarettes per day Follow-up 6 months post-discharge Findings Abstinence: No one abstinent Quit attempt: 6/15 (40%) reported attempt with median length of 62 days, range: 2 to 110 days. Cigarettes per day: Average reduction of 7.16, t(10)=-2.4, p<.04 |

None reported |

Depressive symptoms over 6-month period No significant change in PHQ-9 scores over time, β(SE) = 0.08 (0.09), p=.33, |

| Stuyt, 2015 |

Measures Self-reported tobacco abstinence in the past month verified by tissue testing results obtained from probation officers Follow-up Monthly for 12 months, only 12 months reported Findings Abstinence: 18/120 (15% of smokers at admission) were non-smokers |

None reported |

Relapse to alcohol or drugs 70/102 (69%) of smokers post-discharge vs 5/18 (28%) of non-smokers post-discharge, χ2 = 10.9, p=.001 |

FTND: Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence; PSS: Perceived stress scale; CES-D: Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; PHQ-9: nine item depression screen from Patient Health Questionnaire.

Intervention characteristics

Interventions used a number of theoretical approaches, and varied in intensity, content and mode of delivery (Table 1). In all but one trial (Gariti et al., 2002), inpatient interventions were delivered by researchers, not clinic staff, whereas cohort studies generally reported on interventions delivered by clinic staff (with the exception of Strong et al., 2012)

Post-discharge interventions were included in the five trials (Clarke et al., 2013, Gariti et al., 2002, Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014, Stockings et al., 2014b) and in one observational cohort study (Strong et al., 2012). Telephone calls were used in three studies (Clarke et al., 2013, Stockings et al., 2014b, Strong et al., 2012), ranging from one to eight calls between one day and four months post-discharge; two studies used a computer-generated intervention three and six months post-discharge (Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014) and two provided an optional face-to-face appointment (Gariti et al., 2002, Stockings et al., 2014b) (one (Stockings et al., 2014b) in addition to telephone support).

The trials used different control interventions that included treatment as usual (Gariti et al., 2002, Prochaska et al., 2014, Stockings et al., 2014b), enhanced treatment as usual (Hickman et al., 2015) and a health-related intervention matched for frequency and duration but not addressing smoking cessation (Clarke et al., 2013).

Risk of bias

Four of the trials achieved a global rating of strong (Clarke et al., 2011, Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014, Stockings et al., 2014b); one was rated moderate due to a risk of selection bias (Gariti et al., 2002). One observational cohort study was rated strong (Prochaska et al., 2006) the others were moderate or weak (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of bias (study quality) assessment (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012)

| Selection bias | Design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection | Withdrawals and drop-outs | Global rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised controlled trials | |||||||

| Clarke et al, 2013 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Strong |

| Gariti et al, 2002 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Moderate |

| Hickman et al, 2015 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Strong |

| Prochaska et al, 2014 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Strong |

| Stockings et al, 2014 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Strong |

| Cohort studies | |||||||

| Jonas & Eagle, 1991 | 3 | 2 | n/a | 2 | 3 | 3 | Weak |

| Joseph, 1993 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | n/a | Weak |

| Prochaska et al, 2006 | 2 | 2 | n/a | 2 | 1 | 1 | Strong |

| Strong et al, 2012 | 3 | 3 | n/a | 2 | 1 | n/a | Weak |

| Stuyt, 2015 | 1 | 2 | n/a | 2 | 3 | 1 | Moderate |

Abbreviation: n/a: Assessment item not applicable for a particular study design

Note: 1=strong, 2=moderate, 3=weak

Effects of interventions

Biochemically verified smoking abstinence

Continuous abstinence was reported in only one study (Stockings et al., 2014b) at six months, two participants (1.9%) in the intervention group remained abstinent compared with none in the control group. Due to this lack of data, the primary outcome was not assessed in a meta-analysis.

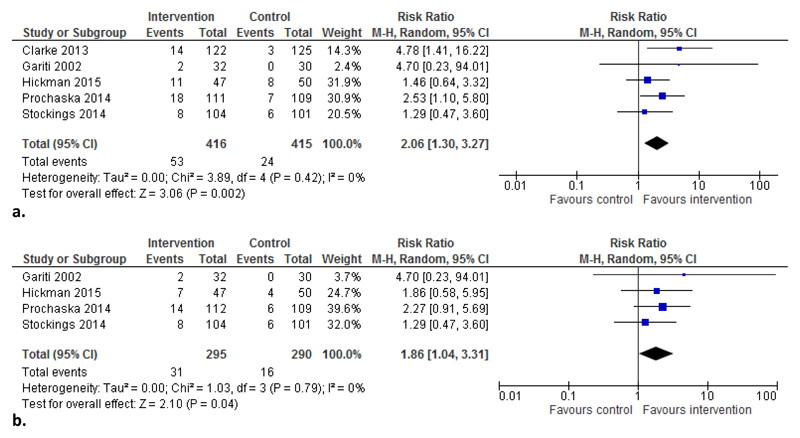

The meta-analysis of seven-day point-prevalence abstinence at longest follow-up (3 to 18 months) included all five trials and found an overall effect in favour of intervention (RR=2.06, 95% CI: 1.30 to 3.27, Figure 2a). Overall, 12.7% of participants in the intervention groups achieved abstinence compared with 5.8% in the control groups.

Figure 2.

a. Comparison of biochemically verified point-prevalence abstinence at longest follow-up in randomised trials. Note: Length of follow-up: Clarke 3 months, Gariti 6 months, Hickman 12 months, Prochaska 18 months, Stockings 6 months.

b. Comparison of biochemically verified point-prevalence abstinence at 6 month follow-up in randomised trials.

Abbreviations: M-H=Mantel-Haenszel

The meta-analysis of seven-day point-prevalence abstinence at six months follow-up excluded the single trial conducted in a prison setting (longest follow-up was 3 months). The meta-analysis also found an effect in favour of intervention (RR=1.86, 95% CI: 1.04 to 3.31, Figure 2b); 10.5% and 5.5% respectively achieved abstinence. No heterogeneity was indicated for either meta-analysis. No further subgroup analysis by setting was conducted because only one trial was set exclusively in substance use (Gariti et al., 2002) and one trial was set in both mental health and substance use settings (Stockings et al., 2014b).

Two observational cohort studies (Prochaska et al., 2006, Strong et al., 2012) aimed to use biochemically verified 7-day point prevalence abstinence. However, in one all patients reported smoking at the 3-month follow-up (Prochaska et al., 2006), the other was a pilot study for intervention development and did not report results on verified abstinence (Strong et al., 2012).

Self-reported smoking abstinence

Four cohort studies reported self-reported abstinence without biochemical verification (Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Joseph, 1993, Strong et al., 2012, Stuyt, 2015). In one, four out of 39 psychiatric patients (10.3%) reported abstinence at 8 weeks post-discharge (Jonas and Eagle, 1991). In another study, 8.0% of patients admitted after the introduction of the smoke-free policy reported having quit smoking compared with 3.2% of patients admitted before introduction of the policy; however, length of follow-up differed, mean follow-up was 16 months for pre-policy and 11 months for post-policy patients (Joseph, 1993). In a pilot with 15 participants, six participants reported a quit attempt with a median number of 62 abstinent days (range 2 to 110 days) (Strong et al., 2012). A year after completing a 90-day substance misuse programme, an increase from 14% to 27% non-smokers among 140 patients was reported (Stuyt, 2015).

Other smoking outcomes – time to first cigarette

Time to first cigarette post-discharge was assessed in two trials and two cohort studies (Clarke et al., 2013, Gariti et al., 2002, Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Prochaska et al., 2006). One trial and one cohort study reported that 76% of participants returned to smoking on the day of discharge (Gariti et al., 2002, Prochaska et al., 2006) and in another cohort study 72% of participants resumed smoking “immediately after discharge”(Jonas and Eagle, 1991). In the trial, 93% returned to smoking within a month with no group differences in the mean number of non-smoking days after discharge (Gariti et al., 2002). In one cohort study, median time to first cigarette was 5 minutes and all participants returned to smoking within 36 days (Prochaska et al., 2006), and in another, all participants who resumed smoking did so within eight weeks post-discharge (Jonas and Eagle, 1991). The other trial displayed information graphically indicating that over 70% in the control group and about 50% in the intervention group returned to smoking within one day; this study reported an effect of treatment in a survival model of days to first smoking lapse (hazard ratio=1.75, p=0.001) (Clarke et al., 2013).

Other smoking outcomes – change in cigarette consumption

Change in cigarette consumption post-discharge compared with the period prior to the stay in a smoke-free environment was assessed in two trials and three cohort studies (Gariti et al., 2002, Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Joseph, 1993, Stockings et al., 2014b, Strong et al., 2012). One trial found a significant reduction for both groups for the six months following hospitalization (24.6 reduced to 10.1 cigarettes per day for the intervention group and 23.8 to 9.4 cigarettes per day for the control group, F(1)=21.07, p<0.001), with no group differences; self-reported reduction was supported by biochemical test results (Gariti et al., 2002). The other trial found a significant effect of the intervention for 50% reduction in cigarettes per day, with 36.5% of intervention participants having reduced their cigarette consumption by six months versus 8.9% in the control group (p<0.0001) (Stockings et al., 2014b). One cohort study reported a self-reported average decrease of seven cigarettes per day (95% CI: -13.80 to 0.51) with a group mean of 13 cigarettes at six-month follow-up (SD=8.35, IQR: 8.2 to 16.1) (Strong et al., 2012). Another cohort study did not find any difference between self-reported number of cigarettes smoked per day at admission and six to 18 months post-discharge (21.6 (SD=13.6) vs 21.3 (SD=15.4) (Jonas and Eagle, 1991)). The third cohort study stated that around 20% of patients reported smoking less (without quantification) and no difference between patients treated before and after the introduction of a smoke-free policy (Joseph, 1993).

Behaviour change techniques

The number of BCTs that could be coded varied considerably between studies and was higher when manuals were available. It ranged from a single technique in published reports of two cohort studies (Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Prochaska et al., 2006) to 34 BCTs (Clarke et al., 2013) and 36 BCTs (Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014) in trial manuals (Table 1).

All studies delivered at least one BCT from the ‘Regulation’ cluster. This cluster includes pharmacological support, reducing negative emotions, conserving mental resources and paradoxical instructions (the latter was not delivered in any study). No study included BCTs coded to be part of the ‘Scheduled consequences’ cluster, which includes ten BCTs focused on specific reward or punishment schedules (other incentives or rewards are included in a different cluster). Two trials covered all remaining 15 clusters (Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014); the trial (Clarke et al., 2013) with the next highest number of BCTs covered 14 clusters, additionally omitting ‘Comparison of behaviour’.

The most commonly used technique was pharmacological support (n=9). Pharmacological support in the form of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) was used in four of the five trials (Gariti et al., 2002, Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014, Stockings et al., 2014b), mostly in the form of patches, and this was available both during and after the stay in the smoke-free institution. In four of the five observational cohort studies (Jonas and Eagle, 1991, Prochaska et al., 2006, Strong et al., 2012, Stuyt, 2015), NRT was available only during inpatient treatment. One study mentioned availability of clonidine patches as part of treatment as usual (Joseph, 1993). The next most commonly used BCTs (all n=6, Table 2) were problem solving (‘Goals and planning’ cluster), unspecified social support (‘Social support’ cluster) and pros and cons (‘Comparison of outcomes’ cluster).

Generally, studies delivered fewer BCTs post-discharge than during the stay, with the exception of one trial (Stockings et al., 2014b), which delivered a more comprehensive intervention after patients had left the hospital.

In addition to the BCTs described in the interventions, a smoke-free environment in itself delivers a number of BCTs for smoking cessation such as restructuring the physical environment (BCT 12.1), restructuring the social environment (12.2), avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour (12.3) and removing access to the reward (7.4) (Michie et al., 2015).

Due to the small number of studies, variable study designs and inconsistent outcome measures, associations between specific behaviour change techniques and outcomes could not be assessed statistically. The two trials reporting an overall positive effect (Clarke et al., 2013, Prochaska et al., 2014) differed in setting, length of stay, mode and intensity of intervention and length of follow-up, but both used over 30 behaviour change techniques during the stay. Interestingly, one did not include pharmacotherapy (Clarke et al., 2013), while the second did during the stay and post-discharge (Prochaska et al., 2014). However, another trial using the same techniques as Prochaska et al., 2014 in a smaller sample from a similar population detected no effect (Hickman et al., 2015).

Discussion

A systematic search found only ten small studies researching maintenance of abstinence from smoking after a period of enforced abstinence in populations with high mental health comorbidity. Outside of trial intervention groups, no or minimal support for maintaining abstinence was delivered. Relapse to smoking occurred very quickly following discharge, and the four studies that reported it found that at least 70% of participants relapsed to smoking on the day of discharge. There was some evidence that providing behavioural or pharmacological interventions was effective for improving abstinence.

Evidence on how best to maintain or increase abstinence in this setting remains limited with few trials or high-quality observational studies. The trials mostly had a low risk of bias while the cohort studies by design were more likely to be affected by bias. In terms of outcome measures, although most used biochemical validation, few attempted to measure continuous abstinence, the strongest outcome (West et al., 2005). However, in this population and setting, a floor effect for continuous abstinence at follow-up would be likely. A single study evaluated an intervention in a prison setting. There was little variety in location; all but one study had been conducted in the US. The interventions under study varied, but many evidence-based interventions have not been evaluated. For example, there is good evidence that contingency management is effective for increasing abstinence from smoking, although there is limited evidence in smokers with mental health problems (Cahill et al., 2015, Hunt et al., 2013). Pharmacotherapies were also limited and no study tested varenicline (Cahill et al., 2016) cytisine (Cahill et al., 2016) or bupropion (Hughes et al., 2014, Tsoi et al., 2013, van der Meer et al., 2013) which have all shown effectiveness.

Limitations of the review include that policies such as smoke-free institutions may be implemented without an evaluation of the effects in the peer-reviewed literature. However, we searched Web of Science, one source of grey literature. Another limitation is due to the complexity and reliability of coding BCTs (Abraham et al., 2015), more experienced coders may have coded some aspects differently. However, the included analysis of BCTs for the first time provides evidence on components assessed in studies to date.

In contrast to the one previous review of the impact of smoke-free psychiatric hospitalisation on smoking (Stockings et al., 2014a), the present review includes only longitudinal studies and includes non-psychiatric institutions with high prevalence of mental health problems. Additionally, in our review, smokers were exposed to complete smoke-free policies and received some intervention to support abstinence. The previous review findings suggested these are crucial for a stay in a smoke-free institution to have an effect on smoking (Stockings et al., 2014a).

As in previous reports (Lorencatto et al., 2013), we found some large differences between descriptions of behavioural interventions in some published reports and manuals. Most strikingly, coding from the manual instead of the publication increased the number of BCTs from four (Hickman et al., 2015, Prochaska et al., 2014) to over 30 each in two cases. Due to the small number of studies and their variable study designs and outcome measures, it remains difficult to draw any clear conclusions about associations between specific techniques and effects of the intervention.

The present evidence suggests that a larger number of BCTs from a wide range of clusters is more likely to result in an effective intervention. It is worth noting that even where the same BCTs are included, delivery will differ (Lorencatto et al., 2016, Lorencatto et al., 2014, Tate et al., 2016), e.g. in frequency, quality and fidelity which can impact effects, akin to medication effectiveness depending on the amount and duration of, and adherence to, treatment.

The present review focused on mental health; it is likely that interventions in other setting such as general hospitals would be transferrable to some extent. However, an existing Cochrane review covered these institutions (Rigotti et al., 2012) while excluding institutions that primarily treat mental health problems or substance abuse. That review found evidence that interventions of the highest intensity, consisting of counselling that began in the hospital and continued for more than one month post-discharge, increased smoking cessation post-discharge; no benefit could be detected from the large number of studies with less intense interventions. The review also found that addition of NRT conferred a benefit while there was not enough evidence for clear conclusions on varenicline or bupropion when added to counselling (Rigotti et al., 2012). For the present review, not enough studies were available to distinguish the impact of interventions delivered during the stay and post-discharge.

Reviews evaluating the evidence for preventing relapse for smokers in the general population who have successfully quit for a short time found some evidence for the use of NRT, bupropion or varenicline (Agboola et al., 2010) but insufficient evidence to recommend the use of any specific behavioural intervention (Agboola et al., 2010, Hajek et al., 2013), indicating the general scarcity of evidence on maintaining abstinence in any population of smokers.

Future research should evaluate interventions in more diverse countries, policy settings and institutions that enforce abstinence as e.g. evidence for prisons is particularly lacking. Research on the effectiveness of interventions such as contingency management and pharmacotherapies other than NRT would be beneficial. Improved reporting is recommended; more comprehensive descriptions of interventions, potentially using frameworks such as the behaviour change technique taxonomy (Michie et al., 2015) would facilitate replication of studies and analysis of effectiveness of different intervention components. In addition, it would be beneficial to report clearly and comprehensively any effects of cessation treatment or cessation on mental health and substance use.

Conclusion

In populations with high rates of smoking and mental health comorbidity there is rapid and almost complete relapse to smoking after a period of enforced abstinence. Institutions implementing smoke-free policies need to also implement interventions to support sustained abstinence to help reduce inequalities in morbidity and mortality due to smoking. Interventions consisting of nicotine replacement and/or behavioural support can increase abstinence beyond discharge. However, the existing evidence base is small, tested only a narrow range of interventions and is limited by imprecise reporting of behavioural interventions. Pharmacological interventions other than NRT and additional behavioural interventions should be assessed and reported.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Clarke, Dr Hickman, Dr Stockings, Dr Strong and Dr Stuyt who shared additional information about their studies and the interventions with us.

LB and AMcN are members of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration Public Health Research: Centre of Excellence. Funding from the Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration is gratefully acknowledged (MR/K023195/1).

Financial support

This work was supported by a Cancer Research UK (CRUK)/ BUPA Foundation Cancer Prevention Fellowship (C52999/ A19748).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None

References

- Abraham C, Wood CE, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Richardson M, Michie S. Reliability of Identification of Behavior Change Techniques in Intervention Descriptions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;49:885–900. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9727-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agboola S, McNeill A, Coleman T, Leonardi Bee J. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Smoking Relapse Prevention Interventions for Abstinent Smokers. Addiction. 2010;105:1362–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of Study Quality for Systematic Reviews: A Comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological Research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2012;18:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-Five Year Mortality of a Community Cohort with Schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196:116–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill K, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R. Incentives for Smoking Cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;5:CD004307. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004307.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill K, Lindson-Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine Receptor Partial Agonists for Smoking Cessation. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016;5:CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, Broadbent MT, Fernandes AC, Lee WE, Hotopf M, Stewart R. Life Expectancy at Birth for People with Serious Mental Illness and Other Major Disorders from a Secondary Mental Health Care Case Register in London. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JG, Martin RA, Stein L, Lopes CE, Mello J, Friedmann P, Bock B. Working inside for Smoking Elimination (Project W.I.S.E.) Study Design and Rationale to Prevent Return to Smoking after Release from a Smoke Free Prison. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:767. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JG, Stein LA, Martin RA, Martin SA, Parker D, Lopes CE, McGovern AR, Simon R, Roberts M, Friedman P, Bock B. Forced Smoking Abstinence: Not Enough for Smoking Cessation. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173:789–94. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in Smoking among Adults with Mental Illness and Association between Mental Health Treatment and Smoking Cessation. JAMA. 2014;311:172–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariti P, Alterman A, Mulvaney F, Mechanic K, Dhopesh V, Yu E, Chychula N, Sacks D. Nicotine Intervention During Detoxification and Treatment for Other Substance Use. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:671–679. doi: 10.1081/ada-120015875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Stead LF, West R, Jarvis M, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Relapse Prevention Interventions for Smoking Cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;5:CD003999. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003999.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman NJ, 3rd, Delucchi KL, Prochaska JJ. Treating Tobacco Dependence at the Intersection of Diversity, Poverty, and Mental Illness: A Randomized Feasibility and Replication Trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17:1012–21. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011 5.1.0. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for Smoking Cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;1:CD000031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GE, Siegfried N, Morley K, Sitharthan T, Cleary M. Psychosocial Interventions for People with Both Severe Mental Illness and Substance Misuse. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews s. 2013:CD001088. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001088.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas JM, Eagle J. Smoking Patterns among Patients Discharged from a Smoke-Free Inpatient Unit. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1991;42:636–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.42.6.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM. Nicotine Treatment at the Drug Dependency Program of the Minneapolis VA Medical Center: A Researcher's Perspective. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber HD, Weiss RD, Anton RF, Jr, George TP, Greenfield SF, Kosten TR, O'Brien CP, Rounsaville BJ, Strain EC, Ziedonis DM, Hennessy G, et al. Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders, Second Edition. American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:5–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Hancock KJ, Kisely S. The Gap in Life Expectancy from Preventable Physical Illness in Psychiatric Patients in Western Australia: Retrospective Analysis of Population Based Registers. BMJ. 2013;346:f2539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorencatto F, West R, Bruguera C, Brose LS, Michie S. Assessing the Quality of Goal Setting in Behavioural Support for Smoking Cessation and Its Association with Outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;50:310–8. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9755-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorencatto F, West R, Bruguera C, Michie S. A Method for Assessing Fidelity of Delivery of Telephone Behavioral Support for Smoking Cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:482–91. doi: 10.1037/a0035149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorencatto F, West R, Stavri Z, Michie S. How Well Is Intervention Content Described in Published Reports of Smoking Cessation Interventions? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15:1273–82. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus SBP, Jenkins R, Brugha T, editors. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. NHS Digital; Leeds: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Wood CE, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis JJ, Hardeman W. Behaviour Change Techniques: The Development and Evaluation of a Taxonomic Method for Reporting and Describing Behaviour Change Interventions (a Suite of Five Studies Involving Consensus Methods, Randomised Controlled Trials and Analysis of Qualitative Data) Health Technology Assessment. 2015;19:1–188. doi: 10.3310/hta19990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Smoking Cessation in Secondary Care: Acute, Maternity and Mental Health Services. NICE; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Fletcher L, Hall SE, Hall SM. Return to Smoking Following a Smoke-Free Psychiatric Hospitalization. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:15–22. doi: 10.1080/10550490500419011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Delucchi K, Hall SM. Efficacy of Initiating Tobacco Dependence Treatment in Inpatient Psychiatry: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1557–1565. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Clair C, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Interventions for Smoking Cessation in Hospitalised Patients. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;5:CD001837. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians & Royal College of Psychiatrists. Smoking and Mental Health. RCP; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stockings EA, Bowman JA, Wiggers J, Baker AL, Terry M, Clancy R, Wye PM, Knight J, Moore LH. A Randomised Controlled Trial Linking Mental Health Inpatients to Community Smoking Cessation Supports: A Study Protocol. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:570. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockings EA, Bowman JA, Prochaska JJ, Baker AL, Clancy R, Knight J, Wye PM, Terry M, Wiggers H. The Impact of a Smoke-Free Psychiatric Hospitalization on Patient Smoking Outcomes: A Systematic Review. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2014a;48:617–33. doi: 10.1177/0004867414533835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockings EAL, Bowman JA, Baker AL, Terry M, Clancy R, Wye PM, Knight J, Moore LH, Adams MF, Colyvas K, Wiggers JH. Impact of a Postdischarge Smoking Cessation Intervention for Smokers Admitted to an Inpatient Psychiatric Facility: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014b;16:1417–1428. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Uebelacker L, Schonbrun YC, Durst A, Saritelli J, Fokas K, Abrantes A, Brown RA, Miller I, Apodaca TR. Development of a Brief Motivational Intervention to Facilitate Engagement of Smoking Cessation Treatment among Inpatient Depressed Smokers. Journal of Smoking Cessation. 2012;7:4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stuyt EB. Enforced Abstinence from Tobacco During in-Patient Dual-Diagnosis Treatment Improves Substance Abuse Treatment Outcomes in Smokers. The American Journal on Addictions. 2015;24:252–257. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatkowski L, McNeill A. Diverging Trends in Smoking Behaviors According to Mental Health Status. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17:356–60. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J, Warner KE, Meza R. Smoking and the Reduced Life Expectancy of Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;51:958–966. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate DF, Lytle LA, Sherwood NE, Haire-Joshu D, Matheson D, Moore SM, Loria CM, Pratt C, Ward DS, Belle SH, Michie S. Deconstructing Interventions: Approaches to Studying Behavior Change Techniques across Obesity Interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2016;6:236–43. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0369-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in Mental Health after Smoking Cessation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for Smoking Cessation and Reduction in Individuals with Schizophrenia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;2:CD007253. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007253.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer RM, Willemsen MC, Smit F, Cuijpers P. Smoking Cessation Interventions for Smokers with Current or Past Depression. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;8:CD006102. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006102.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlbeck K, Westman J, Nordentoft M, Gissler M, Laursen TM. Outcomes of Nordic Mental Health Systems: Life Expectancy of Patients with Mental Disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;199:453–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome Criteria in Smoking Cessation Trials: Proposal for a Common Standard. Addiction. 2005;100:299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Working Group for Improving the Physical Health of People with SMI. Improving the Physical Health of Adults with Severe Mental Illness: Essential Actions. Royal College of Psychiatrists; London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.