Abstract

Background

Probiotics are the most frequently prescribed treatment for children hospitalized with diarrhea in Vietnam. We were in uncertain of the benefits of probiotics for the treatment of acute watery diarrhea in Vietnamese children.

Methods

We conducted a double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of children hospitalized with acute watery diarrhea in Vietnam. Children meeting the inclusion criteria (acute watery diarrhea) were randomized to receive either two daily oral doses of 2×108 CFUs of a local probiotic containing Lactobacillus acidophilus or placebo for 5 days as an adjunct to standard-of-care. The primary endpoint was time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24-hour period without diarrhea. Secondary outcomes included the total duration of diarrhea and hospitalization, daily stool frequency, treatment failure, daily fecal concentrations of rotavirus and norovirus, and Lactobacillus colonization.

Results

150 children were randomized into each study group. The median time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24-hour diarrhea free period was 43 hours (inter-quartile range (IQR) 15-66 hours) in the placebo group and 35 hours (IQR 20-68 hours) in the probiotic group (acceleration factor 1.09 (95% confidence interval 1.78-1.51); p=1.62). There was also no evidence that probiotic treatment was efficacious in any of the pre-defined subgroups nor significantly associated with any secondary endpoint.

Conclusions

This was a large double blind, placebo-controlled trial in which the probiotic underwent longitudinal quality control. We found that under these conditions that Lactobacillus acidophilus was not beneficial in treating children with acute watery diarrhea.

Keywords: Randomized controlled trial, probiotic, lactobacillus, diarrhea, Vietnam, Rotavirus, Norovirus

Introduction

Diarrheal diseases are a major global health issue, with the vast majority of the disease burden arising in young children residing in low-middle income countries (LMIC) (1). It was estimated that >7 million children under the age of five years old died in 2010; 15% of these deaths were attributable to diarrhea (2,3). Typically, episodes of diarrhea are self-limiting, and patients often recover without ever obtaining a diagnosis identifying the etiologic agent. In those who are diagnosed, rotavirus is the most frequently identified pathogen in young children, followed by an array of other viral, parasitic and bacterial agents (4). Vietnam is a rapidly developing LMIC in Southeast Asia, with an estimated mortality rate of 23/1,000 in children aged less than five years (3). The total number of deaths in this age bracket in Vietnam in 2010 was 34,940, 11% of which were associated with diarrhea (3). Oral rehydration solution (ORS), zinc, probiotics (in a multitude of formulations), and antimicrobials are the most commonly used treatments for children hospitalized with acute diarrhea in Vietnam, largely following WHO guidelines (with the exception of probiotics) (5). The use of probiotics in Vietnam is common in both hospitals and the community (6), and we have previously estimated that >70% of 1,500 children hospitalized with diarrhea in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) were prescribed a probiotic (7).

In a Cochrane review of the effect of probiotics for the treatment of acute watery diarrhea, Allen et al. combined data from 8,014 participants that were enrolled in 63 studies (8). The authors noted extensive heterogeneity in study design, definitions, infecting agents, probiotic organisms, and dosages. Notwithstanding these caveats, a combined meta-analysis found probiotics to be effective in reducing the duration of diarrhea by a mean of 24.8 hours (95% confidence interval (95%CI), 15.9-33.6 hours), reduced the frequency of stools on the second day of treatment by a mean of 1.8 stools (95%CI, 1.45-1.14), and lowered the risk of developing persistent diarrhea by 59% (95%CI for risk, 1.32-1.53). The authors advocated larger, more robust trial designs specifically focusing on pathogen identification and the incorporation of standard definitions and endpoints to accurately inform clinical guidelines. There is currently no international regulatory agreement for the manufacture or clinical use of probiotics (9,10), and additional scientific evidence is required to substantiate any potential health benefits of probiotics (11).

We were uncertain as to the benefits of probiotics for the treatment of children with acute watery diarrhea in Vietnam. Therefore, we sought to address many of the limitations raised in the Cochrane review by conducting a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Specifically, we aimed to test the hypothesis that five days of two oral daily doses of 2×108 CFUs of Lactobacillus acidophilus (L. acidophilus), a regime used in diarrheal therapy in hospitals in Vietnam, would be superior to placebo in reducing the time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24-hour period without diarrhea (12).

Materials and Methods

Study population and setting

We conducted a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, recruiting participants with acute watery diarrhea at Children’s Hospital 2 in HCMC, Vietnam. This 1,400-bed hospital serves the local community and acts as tertiary referral center for children with severe infectious diseases and none-communicable diseases in southern Vietnam. A full description of the methods has been published in the study protocol previously (12). Briefly, children (aged between 9 and 60 months of age) hospitalized with acute watery diarrhea were screened for entry into the trial by study staff that had been appropriately trained in the trial procedures and had received GCP certification. Acute watery diarrhea was defined as the passage of loose or watery stools (taking the shape of the container) at least three times in a 24-hour period that did not contain blood or mucus with a history of less than three days. These inclusion criteria are comparable to those defined in the Cochran review (8), “infants and children with 3 watery stools/day without visible blood or mucus (duration not stated)”. The reason for targeting these patients was to, 1) avoid children which may progress to more severe disease manifestations, 2) avoid recruiting children that would receive empirical standard-of-care antimicrobial on admission to hospital, 3) probiotics are standard-of-care in for this presentation in this location, and 4) to quantify viral loads in those infected with either norovirus and rotavirus, of which acute watery diarrhea is the most common presentation of these infections. Patients were excluded if, 1) they had at least one episode of diarrhea in the month prior to admission, 2) they were known to have short bowel syndrome or chronic (inflammatory) gastrointestinal disease, 3) they were immunocompromised or immunosuppressed, 4) they were on prolonged steroid therapy, 5) or were diagnosed as being severely dehydrated, to avoid recruiting those with a more severe manifestation of diarrhea.

A medical monitor oversaw the safety of the trial. Written informed consent to participate in the study was required from a parent or an adult guardian of all patients. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Children’s Hospital 2 and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (OxTREC) of the United Kingdom. The trial was registered at Clinical Trial.gov, number SRCTN88101063.

Study treatments and quality control

All patients received the standard of care according to the National Guidelines for the management of infectious diarrheal diseases in children, which included oral rehydration solution and zinc, but typically not antimicrobials for acute watery diarrhea. However, participants were not excluded when prescribed antimicrobials and all therapies were recorded in a standardized CRF. Participants received either two sachets of 1x108 CFUs of L. acidophilus twice daily (i.e. 4x108/day) or two sachets of identical tasting placebo (maltodextrin excipient only) dissolved in 10ml of water. The study medications were purchased from, and manufactured by, Imexpharm pharmaceutical company (Cao Lanh, Vietnam) according to GMP-WHO regulations; the appearance of the probiotic and placebo sachets and their contents were indistinguishable. The treatment regimens were identical in both groups: doses every 12 hours for five days. An additional dose was given (up to two extra doses in four hours) to participants that vomited within 30 minutes of taking the study medication.

For quality control purposes we performed bacterial culture (for enumeration and identification) on a random selection of sachets (n=5) containing placebo and probiotic before the study initiation and at three monthly intervals (five occasions in total). At all time points the probiotic sachets contained >1x108 CFUs of L. acidophilus only (the specified contents of the sachet); all placebo sachets were sterile. To determine the identity of the L. acidophilus in the sachets, we performed whole genome sequencing (WGS) on the contents of the sachets. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), and 2μg of genomic DNA was subjected to WGS on an Illumina MiSeq 2500platform, following the manufacturer’s recommendations to generate 300 bp paired-end reads, as previously described (13). A de novo assembly was created using SPAdes v·3.7.1 using the ‘careful’ option to optimize error correction; the genome sequence was submitted to Genbank under the accession number SRR4240524. An Additional twelve complete L. acidophilus genome sequences were retrieved from public database, and were aligned together with the aforementioned assembly using Mauve. Locally collinear blocks were trimmed and concatenated, and invariant sites and gaps were removed to produce a 1,292 bp single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) alignment. A maximum likelihood phylogeny was inferred from this alignment using PhyML with 100 bootstrap replicates under the GTR substitution model. By phylogenetic analysis the strain was confirmed to be L. acidophilus La-14 and closely related to a previously sequenced strain (Supplemental Digital Content 1) (14). Reads were also mapped to the reference sequence of L. acidophilus La-14 (accession number NC_021181) using SMALT (version 0.7.4). Candidate SNPs were called against the reference sequence using SAMtools, and low quality SNPs were filtered based on these criteria: consensus quality <50, mapping quality <30, ratio of SNPs to reads at a position <75%, read depth <4, strand bias <0.001, mapping bias <0.001 or tail bias < 0.001. As a result, four consensus SNPs and one intergenic deletion (2 bp) were identified in the L. acidophilus strain used in this study compared to the reference, indicating low genetic divergence between the two.

Randomization, concealment of allocation and blinding

Patients were randomly assigned to receive oral L. acidophilus (probiotic) or placebo (1:1) according to a computer-generated randomization list using block randomization with variable blocks of length four and six. A study pharmacist prepared visually matched sachets in identical, sequentially numbered treatment packs according to the randomization list for dispensation in sequential order as participants were recruited. All participants, enrolling physicians, and investigators were blinded to the treatment allocations. Attending physicians were responsible for enrolling the participants and ensuring that the study medications were given from the appropriate treatment pack. Daily monitoring of all enrolled inpatients by one of the investigators ensured the uniform management and accurate recording of clinical data in individual study notes.

Investigations and follow up

Routine hematology and biochemistry tests were performed on admission to evaluate the severity of dehydration and disease. Multiplex real-time PCR were performed on all fecal samples collected on admission to detect Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter coli, and Campylobacter jejuni (15). Additionally, quantitative real-time PCR was performed on the daily and follow up fecal samples to diagnose norovirus and rotavirus and to calculate their viral loads (16). Furthermore, fecal samples taken on admission, on discharge or the last day of follow up (one or two days after finishing the treatment course), and at outpatient follow-up visits (seven days or eight days after finishing the treatment course for those children whose parent/guardians agreed to return) were subjected to metagenomic DNA extraction and PCR amplified to quantify the concentration of L. acidophilus (target copies/ml of feces) (17,18).

Clinical outcomes

Patients were assessed twice daily until discharge for clinical progress, diarrhea, vomiting, study medication compliance, adverse events and study staff collected daily fecal samples. On discharge and at follow-up, assessments were performed and fecal samples were collected.

The primary outcome was the time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24 hour period without diarrhea as assessed by the treating physician or the participant’s parent/guardian. Secondary endpoints included the total duration of diarrhea, the total duration of hospitalization, stool frequency in the first three days after enrolment, treatment failure (defined as no resolution of diarrhea during the five day treatment course, severe symptoms for which treatment was stopped, the requirement for additional anti-diarrheal treatments), the daily rotavirus and norovirus viral loads in patients with a PCR amplification positive fecal samples, and all adverse events. Additional exploratory endpoints were the recurrence of diarrhea (defined as a new diarrhea episode since the initial episode as assessed at the day 14(+3) follow-up visit), and the vomiting frequency in the first three days after enrolment.

Statistical analysis and sample size calculation

Data from Children’s Hospital 2 identified a median (interquartile range) duration of hospitalization of 5 (3–6) days (mean and SD of log10-duration of 0.61 and 0.27) in our target population (7), and an approximate normal distribution of the log-transformed data. As we had limited pre-existing data on overall length of diarrheal illness (pre-hospitalized and hospitalized) and as children are usually discharged at the time of resolution of diarrhea, we used variability of the length of hospitalization as the basis of the sample size calculation. The trial was designed with the hypothesis that L. acidophilus was superior to placebo for acute watery diarrhea and was powered to detect a relative 20% decrease in the duration of diarrhea (measured in hours), of 4 x 10≥8 CFUs of probiotics compared to placebo; corresponding to an absolute effect size of approximately 24 hours (8). For 80% power at the two-sided 5% significance level, a total of 123 participants per arm were required. To account for potential inadequacies in assumptions and some loss to follow-up, the sample size was increased by 22%. Thus, a total sample size of 300 participants, 150 in each arm, was recruited.

All statistical analyses were pre-defined in a detailed statistical analysis plan, which was finalized before the trial was unblinded (Supplemental Digital Content 5). All randomized participants were included in the main analysis population following the intention-to-treat principle. The primary outcome, the time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24-hour diarrhea free period, was compared between the study groups based on a lognormal accelerated failure time regression model. Children withdrawn or lost to follow-up before cessation of diarrhea were treated as right-censored at the time of withdrawal or loss to follow-up. Homogeneity of the treatment effect was assessed in pre-defined subgroups.

The secondary and exploratory outcomes were compared between the treatment groups based on logistic regression for binary data (treatment failure and recurrence of diarrhea), quasi-Poisson regression for count data (stool frequency and vomiting frequency), and the lognormal accelerated failure time model for time-to-event data (total duration of diarrhea and duration of hospitalization) with treatment as the only covariate. Viral load measurements were summarized by the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of log10-transformed viral load measurements between enrolment (day 1) and day 7 and compared using linear regression models with adjustment for the respective baseline log10-viral load. Log10-transformed L. acidophilus bacteria load changes between enrolment and days 7 and 14, respectively, were compared in the same way. All analyses were performed using the statistical software R version 3.1.1 (19).

Role of funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Baseline characteristics and patient recruitment

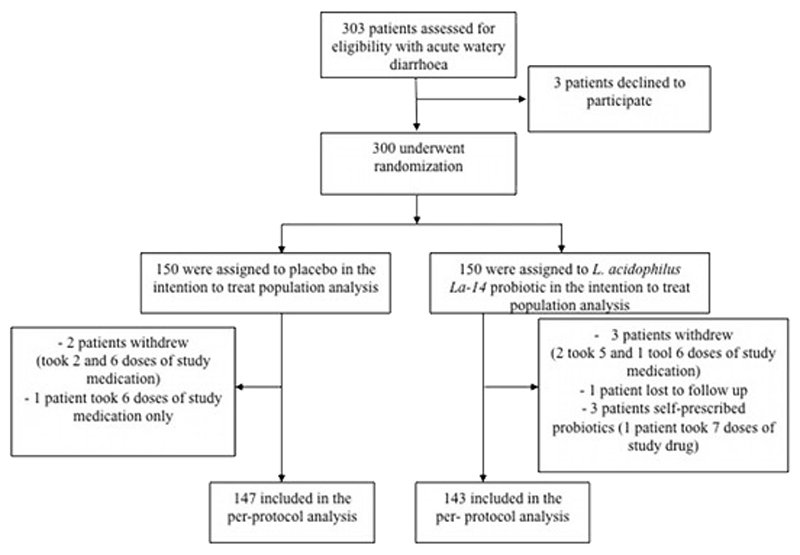

Between October 2014 and September 2015, 303 patients with acute watery diarrhea were screened for enrolment into this trial (Figure 1). Three hundred of these patients (150 in each study arm) met the inclusion criteria and were randomly assigned to receive a best selling Vietnamese brand of probiotic consisting of L. acidophilus only or placebo. Over 14 days of study follow-up, two patients in the placebo arm and three patients in the probiotic arm withdrew from the study after receiving a maximum of six doses of study drug. One additional subject in the placebo arm received only six doses of study drug and one patient in the probiotic group was lost to follow-up. The parents/guardians of three children randomized to the probiotic group gave alternative probiotics in addition to the study treatment, leaving 290 (147 in the placebo arm and 143 in the probiotic arm) in the per-protocol population. In total, five subjects in each arm received less than the scheduled 10 doses of study treatment.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram for trial screening and randomization

The demographic and baseline characteristics of patients were balanced between the two treatment groups in the ITT population (Table 1). The median age of the children was 16 months and approximately one third were female. The inclusion criteria made it more likely we would enroll those with a viral infection than a bacterial infection, and this was the case as 56/150 (37%) and 64/150 (43%) of the fecal samples were PCR amplification positive for rotavirus and 38/150 (25%) and 30/150 (20%) of the fecal samples were PCR amplification positive for norovirus in the placebo arm and probiotic arm, respectively. The proportion of bacterial infections (for the pathogens screened by PCR amplification: Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Shigella) was also comparable between the two groups. Lastly, hematology or biochemical parameters were similar in both groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by treatment group in the intention to treat population

| Characteristic | Placebo (N=150) | Probiotic (N=150) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics, history and clinical examination | ||

| Age [months] – median (IQR) | 15.5 (12.5,21.5) | 15.6 (11.8,21.3) |

| Sex (female) | 49/150 (33%) | 52/150 (35%) |

| Weight [kg] – median (IQR) | 11.1 (9.0,12.0) | 11.2 (9.0,12.0) |

| Temperature [°C] – median (IQR) | 37.8 (37.1,38.3) | 37.8 (37.2,38.5) |

| Pulse [beats/min] – median (IQR) | 121.0 (121.0,128.0) | 124.0 (121.0,128.0) |

| Duration of diarrhea prior to enrolment [hours] – median (IQR) | 33 (20,53) | 36 (24,51) |

| Prior treatment with antibiotics in the previous month | ||

| - Yes | 47/150 (31%) | 38/150 (25%) |

| - No | 90/150 (60%) | 100/150 (67%) |

| - Unknown | 13/150 (9%) | 12/150 (8%) |

| Prior treatment with probiotic in the previous week | ||

| - Yes | 75/150 (50%) | 82/150 (55%) |

| - No | 59/150 (39%) | 52/150 (35%) |

| - Unknown | 16/150 (11%) | 16/150 (11%) |

| Microbiology | ||

| Rotavirus * | 56/150 (37%) | 64/150 (43%) |

| Norovirus** | 38/150 (25%) | 30/150 (20%) |

| Campylobacter | 18/150 (12%) | 11/150 (7%) |

| - C. Coli | 3/18 (17%) | 0/11 (0%) |

| - C. jejuni | 15/18 (83%) | 11/11 (100%) |

| Shigella | 20/150 (13%) | 17/150 (11%) |

| Salmonella | 21/150 (14%) | 14/150 (9%) |

| Hematology and biochemistry | ||

| Hematocrit [%]– median (IQR) | 38.8 (36.5,41.6) | 38.5 (36.4,41.2) |

| White blood cell [K/uL] – median (IQR) | 11.1 (8.0,12.8) | 11.3 (8.0,12.2) |

| Neutrophils [%] – median (IQR) | 53.6 (41.2,67.7) | 51.8 (34.7,68.4) |

| Lymphocytes [%] – median (IQR) | 34.1 (22.5,46.9) | 37.0 (23.3,53.5) |

| Eosinophils [%] – median (IQR) | 1.2 (1.0,1.7) | 1.3 (1.0,1.9) |

| Platelet [K/uL] – median (IQR) | 317.9 (255.4,386.3) | 322.0 (273.6,389.8) |

| Sodium (Na+) [meq/l] – median (IQR) | 133.0 (131.0,136.0) | 134.0 (131.0,135.0) |

| Potassium (K+) [meq/l] – median (IQR) | 3.8 (3.5,4.1) | 3.8 (3.5,4.1) |

| Urea [g/l] – median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.2,1.4) | 1.3 (1.2,1.4) |

| Creatinine [mg/l] – median (IQR) | 4.4 (4.0,5.1) | 4.6 (4.2,5.0) |

Placebo arm included 41 rotavirus mono-infections, 2 rotavirus & norovirus co-infections, 12 rotavirus & bacterial co-infections, and 1 rotavirus & norovirus & bacterial co-infections. Probiotic arm included 52 rotavirus mono-infections, 1 rotavirus & norovirus co-infection, 10 rotavirus & bacterial co-infections, and 1 rotavirus & norovirus & bacterial co-infection.

Placebo arm included 25 norovirus mono-infections, 2 rotavirus & norovirus co-infections, 10 norovirus & bacterial co-infections, and 1 rotavirus & norovirus & bacterial co-infection. Probiotic arm included 22 norovirus mono-infections, 1 rotavirus & norovirus co-infection, 6 norovirus & bacterial co-infections, and 1 rotavirus & norovirus & bacterial co-infection.

Primary outcome and sub-group analyses

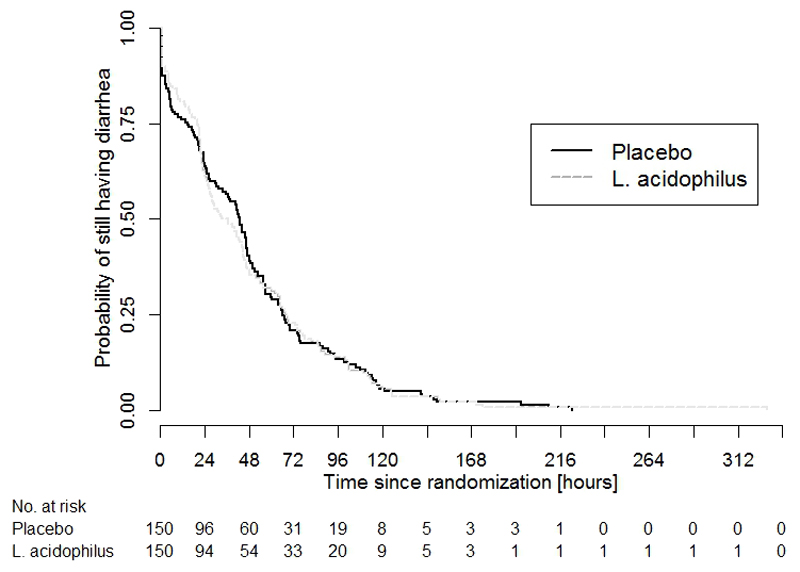

In the ITT population, the median time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24-hour diarrhea free period was 43 hours (IQR 15-66 hours) and 35 hours (IQR 20-68 hours) in the placebo and the probiotic group, respectively. Despite an eight-hour difference between the median times to cessation of diarrhea, the overall distribution of the primary endpoint was similar in both groups and a statistical comparison did not reach significance (p=1.62) (Table 2 and Figure 2). There was also no evidence for probiotic efficacy in the per-protocol population or in any of the pre-defined subgroups according to age, prior treatment, or pathogen (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the primary outcome in all patients and in pre-defined subgroups

| Subgroup | Placebo (N=150) | Probiotic (N=150) | Comparison: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (IQR) [hours] | N | Median (IQR) [hours] | Acceleration Factor (95%CI); p-value | Test for effect heterogeneity (p-value) | |

| All patients (intention-to-treat) | 150 | 43 (15,66) | 150 | 35 (20,68) | 1.09 (1.78,1.51); p=1.62 | |

| Per-Protocol population | 147 | 43 (15,66) | 143 | 33 (20,68) | 1.09 (1.79,1.52); p=1.60 | |

| Age | 1.2 | |||||

| - 0-12 [months] | 32 | 56 (27,91) | 40 | 43 (18,85) | 1.76 (1.40,1.46); p=1.41 | |

| - 13-24 [months] | 85 | 43 (6,70) | 77 | 34 (21,68) | 1.18 (1.75,1.87); p=1.47 | |

| - 25-36 [months] | 22 | 42 (22,56) | 21 | 28 (14,53) | 1.75 (1.33,1.73); p=1.50 | |

| - 37-60 [months] | 11 | 21 (1,30) | 12 | 22 (21,62) | 2.94 (1.96,8.95); p=1.058 | |

| Prior treatment with antibiotics in the past month | 1.42 | |||||

| - Yes | 47 | 48 (23,95) | 38 | 45 (22,66) | 1.34 (1.78,2.29); p=1.29 | |

| - No | 90 | 42 (15,61) | 100 | 28 (14,68) | 1.96 (1.63,1.45); p=1.83 | |

| - Unknown | 13 | 22 (3,41) | 12 | 49 (12,70) | 1.95 (1.47,8.07); p=1.36 | |

| Prior treatment with probiotics in the past week | 1.47 | |||||

| - Yes | 75 | 45 (19,70) | 82 | 28 (17,62) | 1.90 (1.59,1.37); p=1.63 | |

| - No | 59 | 47 (12,68) | 52 | 45 (22,78) | 1.29 (1.73,2.29); p=1.39 | |

| - Unknown | 16 | 24 (6,42) | 16 | 54 (4,125) | 1.56 (1.50,4.90); p=1.44 | |

| Pathogen | 1.17 | |||||

| - Rotavirus | 56 | 48 (18,66) | 64 | 45 (21,76) | 1.07 (1.62,1.85); p=1.81 | |

| - Norovirus | 35 | 24 (5,64) | 28 | 42 (26,76) | 2.1 (1.01,4.37); p=1.047 | |

| - Infected by other bacteria | 24 | 45 (23,64) | 18 | 24 (20,64) | 1.74 (1.34,1.61); p=1.44 | |

| - Unknown | 35 | 46 (19,86) | 40 | 27 (17,45) | 1.78(1.42,1.46); p=1.43 | |

N refers to the number of subjects in each subgroup. Median and inter-quartile range (IQR) of the primary outcome were calculated for each randomized treatment group separately using Kaplan-Meier estimation. Comparisons between groups were based on a parametric lognormal accelerated failure time regression models with treatment as the only covariate. The acceleration factor refers to the estimated relative difference between the duration in the two arms. Values <1 refer to a faster estimated diarrhea clearance in the probiotics arm. Heterogeneity was tested with a likelihood ratio test for an interaction between treatment and each sub-grouping variable. CI: confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of the primary outcome by treatment group

Curves showing the probability of still having diarrhea, i.e. the probability of not yet having reached the onset of the first 24-hour diarrhea-free period (y-axis), against the time since randomization (x-axis) by treatment arm in the intention-to-treat population. L. acidophilus (broken line) and placebo (solid line).

Secondary outcomes and adverse events

Analyses of the secondary endpoints are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in the secondary outcomes or exploratory outcomes between the probiotic group and the placebo group. Specifically, the median total duration of diarrhea was identical at 76 hours (Supplemental Digital Content 2) and the median duration of the hospitalization was 78 hours (IQR 53-104 hours) and 79 hours (IQR 54-104 hours) in the placebo and the probiotic group, respectively (Table 3). Treatment failure occurred in only 11 individuals in the placebo group and 10 in the probiotic group. There was no difference in the number of episodes of diarrhea or vomiting between treatment arms and recurrence of diarrhea occurred in 12% of subjects in each group.

Table 3.

Summary of secondary and exploratory outcomes

| Outcome | Placebo (N=150) | Probiotic (N=150) | Comparison Estimate (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Total duration of diarrhea | AF of time to diarrhea clearance | ||

| - Median (IQR) [hours] | 76 (54,109) | 76 (54,111) | 1.02 (1.89,1.17); p=1.75 |

| Treatment failure£ | OR of treatment failure | ||

| - Frequency [%] | 11/150 (7%) | 10/150 (7%) | 1.90 (1.36,2.21); p=1.82 |

| Total stool frequency in the first three days | Relative difference in stool frequency | ||

| - Median (IQR) [count] | 7 (3,15) | 8 (3,15) | 1.05 (1.83,1.32); p=1.68 |

| Rotavirus viral load AUC | (N=42)$ | (N=52)$ | |

| - Median (IQR) [log10c/ml] | 63.99 (57.98,68.87) | 63.76 (58.59,67.37) | Adjusted absolute mean difference |

| - Mean [log10c/ml] | 63.25 | 63.16 | -1.27 (-3.68,3.14); p=1.87 |

| Norovirus viral load AUC | (N=25)$ | (N=22)$ | |

| - Median (IQR) [log10c/ml] | 43.29 (39.02,49.82) | 44.70 (41.31,51.03) | Adjusted absolute mean difference |

| - Mean [log10c/ml] | 43.66 | 45.98 | 2.63 (-1.58,6.85); p=1.21 |

| Duration of hospitalization | AF of duration of hospitalization | ||

| - Median (IQR) [hours] | 78 (53,104) | 79 (54,104) | 1.97 (1.85,1.11); p=1.66 |

| L. acidophilus bacteria load change after 7 days [log10c/ml] | (N=37)$$ | (N=51) $$ | |

| - Median (IQR) [log10c/ml] | -1.17 (-1.63,1.15) | 1.06 (-1.43,1.28) | Adjusted absolute mean difference |

| - Mean [log10c/ml] | -1.18 | 1.39 | 1.4(-1.23,1.04); p=1.21 |

| L. acidophilus bacteria load change after 14 days [log10c/ml] | (N=34) $$ | (N=34) $$ | |

| - Median (IQR) [log10c/ml] | -1.12(-1.46,1.30) | -1.13(-1.03,1.09) | Adjusted absolute mean difference |

| - Mean [log10c/ml] | -1.12 | -1.36 | 1.095(-1.48,1.67); p=1.75 |

| Exploratory outcomes | |||

| Recurrence of diarrhea | OR of recurrence of diarrhea | ||

| - Frequency [%] | 18/150 (12.00%) | 18/150 (12.00%) | 1.00 (1.50,2.02); p=1.00 |

| Total vomiting frequency in the first three days | Relative difference in vomiting frequency | ||

| - Median (IQR) [count] | 1 (0,5) | 1 (0,5) | 1.21 (1.80,1.82); p=1.37 |

Comparisons were based on lognormal accelerated failure time models [total duration of diarrhea, duration of hospitalization], logistic regression [treatment failure, recurrence of diarrhea], quasi-Poisson regression [stool and vomiting frequency], and linear regression with adjustment for baseline log10-viral load or log10-bacterial load [norovirus and rotavirus AUC, L. acidophilus bacteria load change after 7 days and 14 days]. Median (IQR) of total duration of diarrhea and duration of hospitalization were computed based on Kaplan-Meier estimation.

Treatment failure events were no resolution of diarrhea after 5 days of treatment (7 patients on placebo, 5 on probiotics), requirement for additional anti-diarrheal treatment (3 on placebo, 2 on probiotics), or both of these reasons (1 on placebo, 3 on probiotics).

Longitudinal viral load measurements were only performed patients without bacterial co-infection (Placebo: 40 rotavirus, 23 norovirus, 2 rotavirus & norovirus; Probiotic: 51 rotavirus, 21 norovirus, 1 rotavirus & norovirus). AUCs could not be computed for 1 patient with rotavirus infection, 1 patient with rotavirus and 3 patients with norovirus withdrew at day 1.

Longitudinal L. acidophilus bacteria load measurements were only available for patients who agreed to follow-up after discharge (Placebo: 37 after 7 days, 34 after 14 days; Probiotic: 51 after 7 days, 34 after 14 days).

Abbreviations: AUC= area under the curve of log10-transformed viral load from day 1 to 7; IQR= inter-quartile range; AF= acceleration factor; OR=odds ratio; CI= confidence interval.

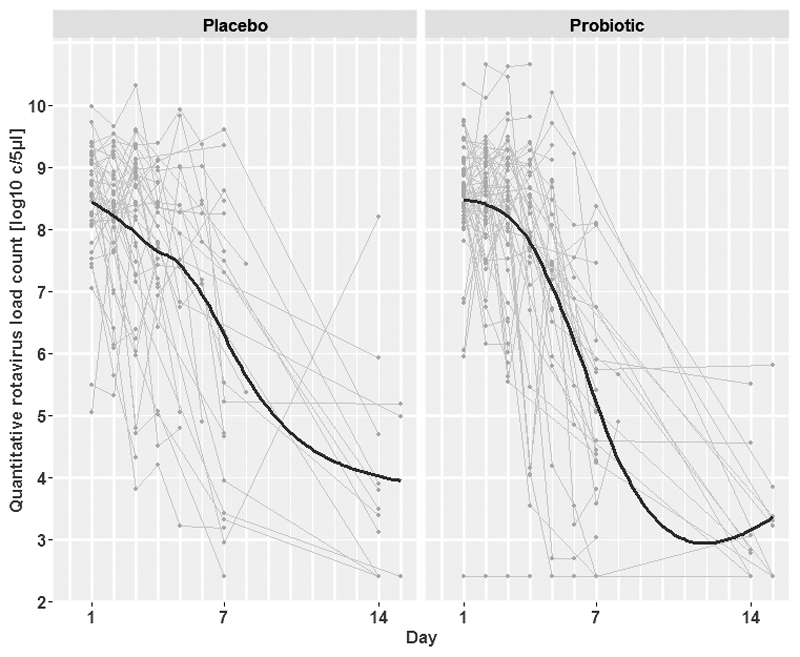

To assess if there was any potential effect of L. acidophilus on those with a viral infection we performed quantitative real-time PCR on longitudinal fecal samples from those infected with rotavirus and norovirus (Figure 3 and Supplemental Digital Content 3). There was a substantial reduction in the number of target copies of rotavirus and norovirus over the 14-day follow up period; the AUC of the viral loads were calculated to assess these dynamics between the two study arms. We found that the median AUC of rotavirus load (log10copies/ml x days) was 63.25 and 63.16 in the placebo and the probiotic group, respectively. The medians AUC of norovirus loads (log10copies/ml x days) were 43.66 and 45.98 in the corresponding groups (Table 3). Lastly, we measured the dynamics of L. acidophilus colonization over the course of the study follow up. L. acidophilus colonization was not distinct between the two groups, log10-transformed L. acidophilus load change in target copies after 7 days and 14 days in both arms were -1.17 and -1.12 (log10 copies/ml) and 1.06 and -1.13 (log10 copies/ml) in the placebo and the probiotic group, respectively (Supplemental Digital Content 4). No adverse events were reported in either of the study groups.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal viral load measurements of rotavirus by treatment group

Plots show rotavirus viral load measurements by quantitative PCR in log10 target copies per ml of feces (y-axis) against time since randomization (x-axis) in the two groups. Grey lines refer to individual patient profiles, solid black lines to LOESS scatterplot smoothers. Longitudinal viral load measurements were collected in patients with confirmed rotavirus infection without bacterial co-infection only.

Discussion

The use of probiotics for treating acute diarrhea is contentious with various studies showing both positive and non-positive effects. However, as highlighted in a Cochrane review, the study designs, selected probiotics, and the target populations in the scientific literature are inconstant, thus leading to extensive variability in the combined data (8). We aimed to address many limitations of poor study design in this trial. First, the study was double blinded and placebo controlled using a locally sourced probiotic, a brand that is commonly used in hospitals in Vietnam to treat diarrhea. Second, we assessed the quality of the probiotic by regular quantitative counts and via genome sequencing to identify the strain composing the probiotic. Third, we measured opposite endpoints on a robust sample size in an appropriate population. Lastly, we aimed to stratify outcomes by etiologic agent and performed quantitative PCR for norovirus, rotavirus, and L. acidophilus in the longitudinally collect fecal specimens. Therefore, we suggest this study provides strong evidence for a lack of efficacy of L. acidophilus in treating children with acute watery diarrhea in Asia.

The use of probiotics in Vietnam is common and they are considered to be safe and cheap; one sachet of the probiotic used in this study cost approximately 1,500 Vietnam Dong (<0.10 USD) and they are frequently prescribed in hospitals and in the community for diarrhea. Here, the duration of acute diarrhea (time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24-hour period without diarrhea or total duration of diarrhea) was not statistically different between children who received L. acidophilus or placebo and there was no evidence that this probiotic provided benefit in the overall population or in any of the pre-defined subgroups. Furthermore, we observed no difference in norovirus or rotavirus viral loads between the two groups. The same observation was true for colonization with L. acidophilus, suggesting that oral L. acidophilus may even not efficiently colonize the gastrointestinal tract during acute diarrhea.

L. acidophilus La-14 is a common probiotic that has been used in various studies previously (20,21), and has been show to boost IgG responses during oral cholera immunization (21). Furthermore, this strain has been found to intrinsically resistant to an array of antimicrobials and to produce a bacteriocin with antimicrobial activity against Listeria moncytogenes (22). There are no previous studies specifically assessing the potential use of L. acidophilus La-14 as a treatment for acute diarrhea and strain selection may be pivotal. There is some scientific evidence that L. acidophilus may have an inhibitory effect on gastrointestinal pathogens, a recent laboratory study conducted in Korea assessed the antiviral activity of probiotics (including L. acidophilus) for rotavirus in vero cells (23). This study found that L. acidophilus had the second highest inhibitory effect after Bifidobacterium longum and significantly shortened the duration of diarrhea in a limited number of patients (23). Further, data generated using L. acidophilus (strain NCFM) showed that strains selection was important in stimulating rotavirus-specific antibody and B-cell responses in gnotobiotic pigs vaccinated with rotavirus vaccine. Our data suggests that further, more physiologic, investigations need to be performed to assess there is a potential mechanism for a clinical impact on diarrhea with L. acidophilus.

There is an urgent need for new therapies for diarrhea, extensive antimicrobial resistance in many Gram-negative enteric pathogens means that we are becoming short of alternative options (24). Probiotics offer an attractive solution, and may have an effect if a functional formulation can be identified and studies are suitably powered. Pooled data from four small RCTs from France, Ecuador, Peru, and Thailand found a reduction in mean duration of diarrhea of caused by predominantly unknown pathogens in children treated with heat–killed L. acidophilus LB (25). Whilst, similar to our data, a group in India found no difference in the duration of diarrhea, stool frequency, and the duration of hospitalization with tyndalized L. acidophilus (undefined strain) in acute diarrhea study in young children (26). Overall, published meta-analyses suggest that diarrheal episodes are shortened by approximately 24 hours with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), L. acidophilus, L. bulgaricus, and L. reuteri (27,28). These findings have led to various guidelines regarding the rational clinical use of probiotics in pediatric acute diarrhea diseases (29,30). Our data question the conclusion of these findings and suggest that L. acidophilus may not beneficial for treating acute diarrhea in children in a low-middle income country.

Our study has limitations, which need to be considered in the context of the presented data. First, the time to cessation of symptoms was assessed by a caregiver or a patient/guardian and may vary according to those recording these data. Second, we were unable to accurately assess the type and duration of antimicrobial given to children prior to inclusion in this study, which may impact on duration and type of symptoms. Notwithstanding these limitations we performed an adequately powered, double blind, study under operational conditions with a common available and routinely used probiotic.

In conclusion, we found that L. acidophilus did not reduce the time from the first dose of study medication to the start of the first 24- hour period without diarrhea in comparison to placebo. Further, there was no difference between intervention and placebo in the total duration of diarrhea, the total duration of hospitalization, stool frequency during the first three days of treatment, treatment failure, or daily rotavirus and norovirus fecal loads. Our data add additional evidence regarding the role of probiotics in treating diarrheal disease and suggest that L. acidophilus may not have a measurable effect in this setting.

Supplementary Material

The phylogenetic structure of Lactobacillus acidophilus

Mid-point rooted maximum likelihood phylogeny of 13 L. acidophilus strains, including strain used in this study (highlighted in red) and 12 complete whole genome sequences retrieved from the public database. Numbers above branches indicate bootstrap support values, and horizontal scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Kaplan-Meier curve of the total duration of diarrhea by treatment group

Kaplan-Meir curve showing the probability of still having diarrhea, i.e. the probability of not yet having reached the onset of the first 24-hour diarrhea-free period (y-axis), against the time since the onset of diarrhea (x-axis) in the intention-to-treat population by intervention. L. acidophilus (broken line) and placebo (solid line).

Longitudinal viral load measurements of norovirus by treatment group

Plot show norovirus viral loads by quantitative PCR in log10 target copies per ml of feces (y-axis) against time since randomization (x-axis) in the two groups. Grey lines refer to individual patient profiles, solid black lines to LOESS scatterplot smoothers. Longitudinal viral load measurements were collected in patients with confirmed norovirus infection without bacterial co-infection only.

Longitudinal load measurements of L. acidophilus by treatment group

Plots showing L. acidophilus load by quantitative PCR in log10 target copies per ml of feces (y-axis) against time since randomization (x-axis) in the placebo and the probiotic arms. Grey lines refer to individual patient profiles; solid black lines refer to lines through the means on day 1, 7(+1) and 14 (or later).

Consort checklist

Statistical analysis plan

Acknowledgements

The Oxford-Vietnam probiotics study group are: Named authors and James I Campbell, Laura Merson, Corinne N Thompson, and Ha Thanh Tuyen from The Wellcome Trust Major Overseas Programme, Vo Thi Van, Nguyen Hong Van Khanh, Nguyen Thi Hong Loan, Nguyen Thi Thu Thu, Vo Hoang Khoa, Nguyen Cam Tu, Nguyen Thi Thanh Tam from Children’s Hospital, and Ha Vinh from Phạm Ngọc Thạch Medical University. We are indebted to the patients and their relatives for their participation in the trial. We wish to acknowledge the doctors and nurses of Children’s Hospital 2 who cared for the children enrolled in this study, specifically: Nguyen Thi Phuong Dung, Nguyen Van Vinh Chau, Nguyen Thi Ho Diep, Pham Thi Ngoc Tuyet, Ho Lu Viet, Hoang Minh Tu Van, Lu Lan Vi, Do Thi Phuong Trang, Lam Boi Hy, Nguyen Thi Kim Ngan, Ms Pham Thi Mai Anh, Tran Thi Tuyet Minh, Tran Thi Minh Phuong, Tran Thi Tuyet Nga, and Vu Thi Thuy.

Funding: This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust and the OAK Foundation. SB is funded by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society(100087/Z/12/Z). The funders had no role in interpretation or publication of the data.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to declare

Contributors

CT, GT, HV, JC, LM, MK, MW JFF and SB designed and conceived the study. CN, CT, KN, KV, LN, NN, SB, NT, TH, TN, TN, TN and VV ran the study and contributed data. MW, NL performed the analysis. CN, HC, JC and TN performed the experiments contributing to this study. CT, CN, NL and SB wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Wu Y, Sow SO, Sur D, Breiman RF, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Campbell H, Cibulskis R, Li M, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379:2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, Idele P, Hogan D, Mathers C, Gerland P, New JR, Alkema L, United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet. 2015;386:2275–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duong VT, Phat VV, Tuyen HT, Dung TTN, Trung PD, Van Minh P, Tu LTP, Campbell JI, Le Phuc H, Ha TTT, et al. Evaluation of Luminex xTAG Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel Assay for Detection of Multiple Diarrheal Pathogens in Fecal Samples in Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1094–100. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03321-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The World Health Organization. THE TREATMENT OF DIARRHOEA: A manual for physicians and other senior health work. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pham DM, Byrkit M, Van Pham H, Pham T, Nguyen CT. Improving pharmacy staff knowledge and practice on childhood diarrhea management in Vietnam: are educational interventions effective? PLoS One. 2013;8:e74882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson CN, Phan MVT, Hoang NVM, Van Minh P, Vinh NT, Thuy CT, Nga TTT, Rabaa MA, Duy PT, Dung TTN, et al. A prospective multi-center observational study of children hospitalized with diarrhea in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:1045–52. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, Dans LF. Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003048.pub3. CD003048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rijkers GT, de Vos WM, Brummer R-J, Morelli L, Corthier G, Marteau P. Health benefits and health claims of probiotics: bridging science and marketing. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:1291–6. doi: 10.1017/S000711451100287X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders ME, Heimbach JT, Pot B, Tancredi DJ, Lenoir-Wijnkoop I, Lähteenmäki-Uutela A, Gueimonde M, Bañares S. Health claims substantiation for probiotic and prebiotic products. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:127–33. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.3.16174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagpal R, Kumar A, Kumar M, Behare PV, Jain S, Yadav H. Probiotics, their health benefits and applications for developing healthier foods: a review. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;334:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolader M-E, Vinh H, Ngoc Tuyet PT, Thompson C, Wolbers M, Merson L, Campbell JI, Ngoc Dung TT, Manh Tuan H, Van Vinh Chau N, et al. An oral preparation of Lactobacillus acidophilus for the treatment of uncomplicated acute watery diarrhoea in Vietnamese children: study protocol for a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:27. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pham Thanh D, Karkey A, Dongol S, Ho Thi N, Thompson CN, Rabaa MA, Arjyal A, Holt KE, Wong V, Tran Vu Thieu N, et al. A novel ciprofloxacin-resistant subclade of H58 Salmonella Typhi is associated with fluoroquinolone treatment failure. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stahl B, Barrangou R. Complete Genome Sequence of Probiotic Strain Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14. Genome Announc. 2013;1 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00376-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anders KL, Thompson CN, Van Thuy NT, Nguyet NM, Tu LTP, Dung TTN, Phat VV, Van NTH, Hieu NT, Tham NTH, et al. The epidemiology and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infancy in southern Vietnam: a birth cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;35:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dung TTN, Phat VV, Nga TVT, My PVT, Duy PT, Campbell JI, Thuy CT, Hoang NVM, Van Minh P, Le Phuc H, et al. The validation and utility of a quantitative one-step multiplex RT real-time PCR targeting rotavirus A and norovirus. J Virol Methods. 2013;187:138–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Browne HP, Forster SC, Anonye BO, Kumar N, Neville BA, Stares MD, Goulding D, Lawley TD. Culturing of ‘unculturable’ human microbiota reveals novel taxa and extensive sporulation. Nature. 2016;533:543–6. doi: 10.1038/nature17645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haarman M, Knol J. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of fecal Lactobacillus species in infants receiving a prebiotic infant formula. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2359–65. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2359-2365.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Team R. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Open access available http//cran.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Alberti D, Russo R, Terruzzi F, Nobile V, Ouwehand AC. Lactobacilli vaginal colonisation after oral consumption of Respecta(®) complex: a randomised controlled pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:861–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paineau D, Carcano D, Leyer G, Darquy S, Alyanakian M-A, Simoneau G, Bergmann J-F, Brassart D, Bornet F, Ouwehand AC. Effects of seven potential probiotic strains on specific immune responses in healthy adults: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;53:107–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Todorov SD, Furtado DN, Saad SMI, Gombossy de Melo Franco BD. Bacteriocin production and resistance to drugs are advantageous features for Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14, a potential probiotic strain. New Microbiol. 2011;34:357–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DK, Park JE, Kim MJ, Seo JG, Lee JH, Ha NJ. Probiotic bacteria, B. longum and L. acidophilus inhibit infection by rotavirus in vitro and decrease the duration of diarrhea in pediatric patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung The H, Rabaa MA, Pham Thanh D, De Lappe N, Cormican M, Valcanis M, Howden BP, Wangchuk S, Bodhidatta L, Mason CJ, et al. South Asia as a Reservoir for the Global Spread of Ciprofloxacin-Resistant Shigella sonnei: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szajewska H, Ruszczyński M, Kolaček S. Meta-analysis shows limited evidence for using Lactobacillus acidophilus LB to treat acute gastroenteritis in children. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103:249–55. doi: 10.1111/apa.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna V, Alam S, Malik A, Malik A. Efficacy of tyndalized Lactobacillus acidophilus in acute diarrhea. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:935–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02731667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szajewska H, Setty M, Mrukowicz J, Guandalini S. Probiotics in gastrointestinal diseases in children: hard and not-so-hard evidence of efficacy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:454–75. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000221913.88511.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szajewska H, Kotowska M, Mrukowicz JZ, Armańska M, Mikołajczyk W. Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in prevention of nosocomial diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr. 2001;138:361–5. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szajewska H, Guarino A, Hojsak I, Indrio F, Kolacek S, Shamir R, Vandenplas Y, Weizman Z, European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Use of probiotics for management of acute gastroenteritis: a position paper by the ESPGHAN Working Group for Probiotics and Prebiotics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:531–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruchet S, Furnes R, Maruy A, Hebel E, Palacios J, Medina F, Ramirez N, Orsi M, Rondon L, Sdepanian V, et al. The use of probiotics in pediatric gastroenterology: a review of the literature and recommendations by Latin-American experts. Paediatr Drugs. 2015;17:199–216. doi: 10.1007/s40272-015-0124-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The phylogenetic structure of Lactobacillus acidophilus

Mid-point rooted maximum likelihood phylogeny of 13 L. acidophilus strains, including strain used in this study (highlighted in red) and 12 complete whole genome sequences retrieved from the public database. Numbers above branches indicate bootstrap support values, and horizontal scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Kaplan-Meier curve of the total duration of diarrhea by treatment group

Kaplan-Meir curve showing the probability of still having diarrhea, i.e. the probability of not yet having reached the onset of the first 24-hour diarrhea-free period (y-axis), against the time since the onset of diarrhea (x-axis) in the intention-to-treat population by intervention. L. acidophilus (broken line) and placebo (solid line).

Longitudinal viral load measurements of norovirus by treatment group

Plot show norovirus viral loads by quantitative PCR in log10 target copies per ml of feces (y-axis) against time since randomization (x-axis) in the two groups. Grey lines refer to individual patient profiles, solid black lines to LOESS scatterplot smoothers. Longitudinal viral load measurements were collected in patients with confirmed norovirus infection without bacterial co-infection only.

Longitudinal load measurements of L. acidophilus by treatment group

Plots showing L. acidophilus load by quantitative PCR in log10 target copies per ml of feces (y-axis) against time since randomization (x-axis) in the placebo and the probiotic arms. Grey lines refer to individual patient profiles; solid black lines refer to lines through the means on day 1, 7(+1) and 14 (or later).

Consort checklist

Statistical analysis plan